church review

church review

church review

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

the KInG JaMes VersIon has left a<br />

lastInG bIblICal and lIterary leGaCy<br />

Patrick Comerford<br />

Throughout the Church, parishes,<br />

dioceses, bookshops, schools, colleges and<br />

other organisations are marking the<br />

400th anniversary of the publication of<br />

the King James Version of the Bible in<br />

1611 with public readings, scholarly<br />

conferences, historical exhibitions, new<br />

books, commemorative services and a<br />

BBC television series.<br />

This was not the first translation of the Bible<br />

into English, nor has it remained the world’s<br />

best-selling or most familiar Bible. Yet, it has<br />

deeply influenced the way we speak and has left<br />

a lasting literary legacy.<br />

The literary development and maturing of<br />

the English language by the beginning of the<br />

17th century, the discovery of new Biblical<br />

manuscripts and Biblical Hebrew and Greek,<br />

and the combined effect of the Renaissance, the<br />

Reformation and the development of printing,<br />

all at a time when Britain was entering a period<br />

of political and social stability and coherence,<br />

brought into being a well-loved version of the<br />

Bible that remains an enduring standard in<br />

many ways to this day. Although several<br />

revisions were made to update and correct<br />

errors in its translation and its printing, it was<br />

deliberately memorable in its prose and poetry.<br />

But how did we get this version of the Bible?<br />

And what is its lasting and enduring legacy?<br />

earlier translations<br />

In the early part of the reign of Henry VIII,<br />

William Tyndale began translating the Bible into<br />

English, using the work of Erasmus as his<br />

foundation. In 1525-1526, he published his New<br />

Testament and began work on the Old<br />

Testament, completing the first five books of<br />

the Bible the following year. Most of his work<br />

was completed abroad, but the authorities<br />

caught up to Tyndale in 1536 and he was<br />

burned at the stake. His dying words were:<br />

“Lord, open the King of England’s eyes.”<br />

The English Reformation saw the<br />

introduction of the English language for <strong>church</strong><br />

services and the Bible was soon introduced in<br />

a number of English language translations, each<br />

building on its predecessor as well as other<br />

works of translation.<br />

The Coverdale Bible, translated by Myles<br />

Coverdale, a Cambridge monk, in 1535, drew<br />

on Luther’s German translation, the Latin Bible<br />

and Tyndale’s work. The Matthew Bible,<br />

published by John Rogers using the pseudonym<br />

Thomas Matthew, followed in 1537. The Great<br />

Bible, printed in Paris in 1539, under the<br />

patronage of Thomas Cranmer, was essentially a<br />

revision of the Matthew Bible, and was revised<br />

again and again in the following years.<br />

By the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, more<br />

English translations had followed, including the<br />

Geneva Bible in 1557 and 1560. It was a<br />

scholarly work, using original texts, smaller<br />

fonts and the familiar verse format of today’s<br />

Bibles, with particular words highlighted to<br />

indicate they had been added to emphasise the<br />

original. Although this version exhibited many<br />

strong biases, It quickly gained popularity,<br />

despite its many strong biases, and was<br />

popularly known as the “Breeches’ Bible” for its<br />

description of the naked Adam and Eve making<br />

themselves breeches (Genesis 3: 7).<br />

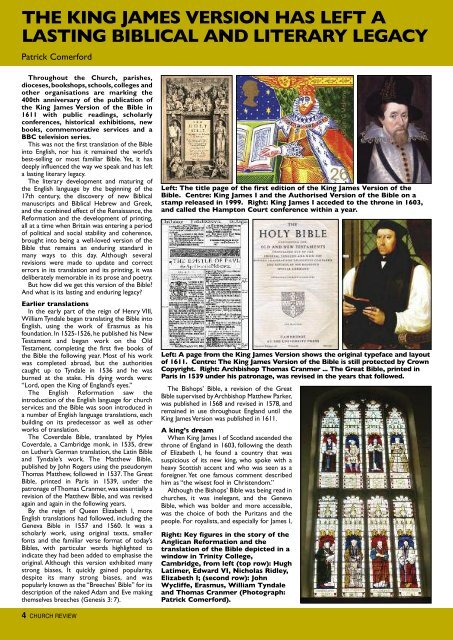

left: the title page of the first edition of the King James Version of the<br />

bible. Centre: King James I and the authorised Version of the bible on a<br />

stamp released in 1999. right: King James I acceded to the throne in 1603,<br />

and called the hampton Court conference within a year.<br />

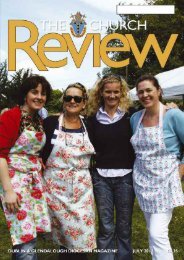

left: a page from the King James Version shows the original typeface and layout<br />

of 1611. Centre: the King James Version of the bible is still protected by Crown<br />

Copyright. right: archbishop thomas Cranmer ... the Great bible, printed in<br />

Paris in 1539 under his patronage, was revised in the years that followed.<br />

The Bishops’ Bible, a revision of the Great<br />

Bible supervised by Archbishop Matthew Parker,<br />

was published in 1568 and revised in 1578, and<br />

remained in use throughout England until the<br />

King James Version was published in 1611.<br />

a king’s dream<br />

When King James I of Scotland ascended the<br />

throne of England in 1603, following the death<br />

of Elizabeth I, he found a country that was<br />

suspicious of its new king, who spoke with a<br />

heavy Scottish accent and who was seen as a<br />

foreigner. Yet one famous comment described<br />

him as “the wisest fool in Christendom.”<br />

Although the Bishops’ Bible was being read in<br />

<strong>church</strong>es, it was inelegant, and the Geneva<br />

Bible, which was bolder and more accessible,<br />

was the choice of both the Puritans and the<br />

people. For royalists, and especially for James I,<br />

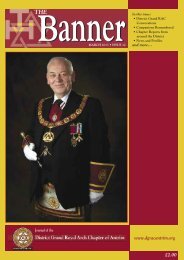

right: Key figures in the story of the<br />

anglican reformation and the<br />

translation of the bible depicted in a<br />

window in trinity College,<br />

Cambridge, from left (top row): hugh<br />

latimer, edward VI, nicholas ridley,<br />

elizabeth I; (second row): John<br />

Wycliffe, erasmus, William tyndale<br />

and thomas Cranmer (Photograph:<br />

Patrick Comerford).<br />

4 ChurCh <strong>review</strong>