Young v. Saanich Police Department, 2003 BCSC 926 (CanLII).

Young v. Saanich Police Department, 2003 BCSC 926 (CanLII).

Young v. Saanich Police Department, 2003 BCSC 926 (CanLII).

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

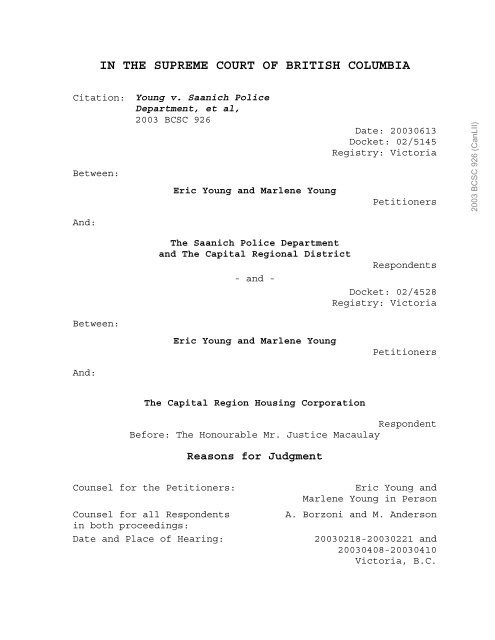

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF BRITISH COLUMBIA<br />

Citation: <strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong><br />

<strong>Department</strong>, et al,<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong><br />

Between:<br />

And:<br />

Eric <strong>Young</strong> and Marlene <strong>Young</strong><br />

Date: <strong>2003</strong>0613<br />

Docket: 02/5145<br />

Registry: Victoria<br />

Petitioners<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

The <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong><br />

and The Capital Regional District<br />

- and -<br />

Respondents<br />

Docket: 02/4528<br />

Registry: Victoria<br />

Between:<br />

And:<br />

Eric <strong>Young</strong> and Marlene <strong>Young</strong><br />

Petitioners<br />

The Capital Region Housing Corporation<br />

Respondent<br />

Before: The Honourable Mr. Justice Macaulay<br />

Reasons for Judgment<br />

Counsel for the Petitioners:<br />

Counsel for all Respondents<br />

in both proceedings:<br />

Date and Place of Hearing:<br />

Eric <strong>Young</strong> and<br />

Marlene <strong>Young</strong> in Person<br />

A. Borzoni and M. Anderson<br />

<strong>2003</strong>0218-<strong>2003</strong>0221 and<br />

<strong>2003</strong>0408-<strong>2003</strong>0410<br />

Victoria, B.C.

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 2<br />

Introduction<br />

[1] Mr. <strong>Young</strong> suffers from multiple sclerosis. Mr. and<br />

Mrs. <strong>Young</strong> are legally exempted from the application of<br />

certain provisions of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act,<br />

S.C. 1996, c. 19 (the "CDSA") to permit them to grow marihuana<br />

so that Mr. <strong>Young</strong> may use it for the treatment of his medical<br />

condition. The <strong>Young</strong>s have brought two separate petitions<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

before this court. They brought their first petition against<br />

the <strong>Saanich</strong> police (the "SPD") and the Capital Regional<br />

District (the "CRD") seeking constitutional remedies for<br />

alleged Charter breaches interfering with their right to grow<br />

and use marihuana ("Action 02/5145"). The petitioners contend<br />

that the breaches culminated in an improper attempt by their<br />

landlord to evict them from their rental unit in a social<br />

housing project solely because they grew, and Mr. <strong>Young</strong> used,<br />

marihuana.<br />

[2] The landlord is the Capital Region Housing Corporation<br />

(the "CRHC"), rather than the CRD, although the two entities<br />

are connected. The CRHC is a private company incorporated by<br />

the CRD as part of the latter's mandate to provide partially<br />

subsidized housing in the Capital Region. In August 2002, an<br />

arbitrator held that the landlord had established sufficient<br />

cause to terminate the tenancy because the smells associated

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 3<br />

with the cultivation and use of marihuana were unreasonably<br />

disturbing and interfering with the lawful rights of other<br />

tenants contrary to the Residential Tenancy Act, R.S.B.C.<br />

1996, c. 406 (the "RTA").<br />

[3] The landlord’s subsequent application to the Residential<br />

Tenancy Branch for an order of possession was adjourned<br />

pending the outcome of the second proceeding before me. If<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

Mr. and Mrs. <strong>Young</strong> are unsuccessful in both Supreme Court<br />

proceedings, they will be required to move out of their home.<br />

[4] In October 2002, Mr. and Mrs. <strong>Young</strong> filed the second<br />

petition pursuant to the Judicial Review Procedure Act (the<br />

"JRPA") to challenge the arbitrator's findings under the RTA<br />

("Action 02/4528"). That proceeding is brought against the<br />

CRHC only. Although the petitioners raise a number of<br />

specific administrative law issues in that proceeding, I am<br />

not persuaded that there is any merit to those complaints.<br />

Instead, in my view, the only viable means of attack on the<br />

eviction would require a positive finding on the Charter<br />

claims raised in Action 02/5145. Such a finding might remove<br />

the necessary underpinnings for the exercise of statutory<br />

jurisdiction by the arbitrator, at the behest of the CRHC,<br />

provided that the landlord is itself a state actor subject to<br />

Charter scrutiny.

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 4<br />

Summary of Findings<br />

[5] Both petitions were heard at the same time. Because the<br />

issues arise, for the most part, out of common facts and are<br />

connected as described immediately above, I am issuing my<br />

reasons jointly. I have concluded that the petitioners have<br />

failed to make out any of the Charter breaches as alleged in<br />

Action 02/5145. This conclusion is also significant for<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

Action 02/4528. Even if the CRHC is a state actor engaged in<br />

state conduct, the Charter issues raised against it would be<br />

identical to those raised against the CRD. Absent Mr. and<br />

Mrs. <strong>Young</strong> establishing some other basis for judicial review<br />

of the arbitrator’s decision under the RTA, and I find none,<br />

the second proceeding must also be dismissed. Accordingly,<br />

both proceedings are dismissed.<br />

[6] For convenience, my reasons are organized under the<br />

following headings and paragraph references:<br />

HEADINGS<br />

PARAGRAPH NUMBERS<br />

Introduction paras. 1-4<br />

Summary of Findings paras. 5-6<br />

Medical Exemptions paras. 7-12<br />

The Housing Complex paras. 13-14<br />

Marihuana Use in the Building para. 15

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 5<br />

Difficulties with the Neighbours paras. 16-25<br />

The Signs paras. 26-27<br />

The Complaints paras. 28-33<br />

The Inspection paras. 34-37<br />

The Notice of Eviction paras. 38-39<br />

The Hearing Before<br />

Arbitrator Gilbert<br />

paras. 40-41<br />

The Review Application paras. 42-45<br />

The Human Rights Complaint paras. 46-53<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

The <strong>Police</strong> paras. 54-58<br />

The Petitioners' Complaints<br />

about the <strong>Police</strong><br />

paras. 59-63<br />

Charter Issues paras. 64-73<br />

CRHC as a Government Actor paras. 74-77<br />

The Assumptions para. 78<br />

Section 15: Issues paras. 79-81<br />

The "Zero-Tolerance" Policy paras. 82-96<br />

Absence of a Policy paras. 97-99<br />

Section 8: Issues paras. 100-101<br />

SPD paras. 102-106<br />

CHRC paras. 107-111<br />

Section 7: Issues paras. 112-115<br />

CHRC paras. 116-117<br />

Liberty para. 118<br />

Security of the Person paras. 119-125

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 6<br />

Principles of Fundamental Justice paras. 126-131<br />

Issues on Judicial Review paras. 132-135<br />

Standards of Review paras. 136-139<br />

Reasonable Apprehension of Bias paras. 140-143<br />

The Adjournment Applications paras. 144-150<br />

Wrongful Denial of Attendance<br />

at the Hearing by a Member<br />

of the Public<br />

para. 151<br />

The Refusal to Exclude Ms. Jaarsma para. 152<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

The Alleged Refusal to Visit the<br />

Complex to Determine Whether the<br />

Smell of Marihuana was Present<br />

Review of the Arbitrator's<br />

Findings of Fact<br />

Residential Tenancy Act and<br />

Residential Tenancy Office<br />

Arbitration Rules of Procedure<br />

paras. 153-157<br />

paras. 158-162<br />

APPENDIX A<br />

Medical Exemptions<br />

[7] In February 1996, Mr. <strong>Young</strong> was diagnosed with multiple<br />

sclerosis. Mr. <strong>Young</strong> has since found marihuana to be an<br />

effective medication for alleviating the symptoms of his<br />

condition. Many of the medications otherwise available to Mr.<br />

<strong>Young</strong> have serious health-related side effects that he wishes<br />

to avoid.<br />

[8] In June 1999, Mr. <strong>Young</strong> obtained a medical prescription<br />

for marihuana for the treatment of his condition. He

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 7<br />

subsequently applied to the Minister of Health for an<br />

exemption permitting him lawful access to marihuana for<br />

medicinal purposes.<br />

[9] On March 10, 2000, Health Canada advised Mr. <strong>Young</strong> by<br />

letter that his application had been favourably reviewed.<br />

Pursuant to s. 56 of the CDSA, the Minister of Health granted<br />

Mr. <strong>Young</strong> an exemption from the application of various<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

provisions of the CDSA. Mr. <strong>Young</strong> was thereby permitted to<br />

lawfully possess and produce marihuana subject to certain<br />

restrictions, including conditions that the marihuana be used<br />

solely for personal use in the treatment of his medical<br />

condition and that he not allow any other person to use his<br />

supply of marihuana.<br />

[10] The letter stated that the exemption would expire on<br />

September 11, 2000, subject to renewal. The letter also<br />

contained the following paragraph:<br />

Further to your consent (see form attached), your<br />

name, date of birth and details of this exemption<br />

will be provided to police agencies in order to<br />

limit the risk that you may be inadvertently<br />

arrested or charged by the police. You should also<br />

carry this exemption with you whenever you are in<br />

physical possession of the controlled substance, to<br />

show that you have received an exemption from the<br />

Minister of Health.

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 8<br />

Mr. <strong>Young</strong> has never provided his consent to the Minister<br />

regarding the release of the above-mentioned information to<br />

police agencies.<br />

[11] Mr. <strong>Young</strong>’s exemption was renewed from time to time<br />

pursuant to s. 56 and remained in effect at all material<br />

times. Specifically, the exemption was renewed on the<br />

following dates: September 1, 2000; March 5, 2001;<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

December 12, 2001; March 12, 2002; September 5, 2002 and<br />

October 4, 2002.<br />

[12] On December 12, 2001, the Minister of Health granted a<br />

similar exemption to Mrs. <strong>Young</strong>, permitting her to possess and<br />

produce marihuana for the sole purpose of assisting Mr. <strong>Young</strong><br />

with the treatment of his medical condition. Mrs. <strong>Young</strong>’s<br />

exemption has also been renewed from time to time and has been<br />

in effect at all material times.<br />

The Housing Complex<br />

[13] The petitioners reside in a complex known as Beechwood<br />

Park. The CRHC owns and manages the complex, which consists<br />

of townhouses and a three story apartment building. Some, but<br />

not all, of the units are subsidized.

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 9<br />

[14] The petitioners moved into a two-bedroom first floor<br />

suite in the apartment building at the beginning of September<br />

2001. They pay market rent.<br />

Marihuana Use in the Building<br />

[15] Mr. <strong>Young</strong> has smoked marihuana in his suite or on his<br />

patio on a regular basis since the commencement of the<br />

tenancy. He deposed that he smokes the equivalent of 1/4 of a<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

tobacco cigarette every two to three hours or 1 1/2 tobacco<br />

cigarettes per day. He further deposed that he and his wife<br />

take steps to minimize the marihuana smoke in their suite by<br />

opening windows and using fans and an air purifier. He also<br />

maintains that the building is designed with pressurized<br />

hallways that create an airflow from the hallway into the<br />

suites for the purpose of minimizing smoke in the hallway in<br />

the event of a fire.<br />

Difficulties with the Neighbours<br />

[16] The petitioners' difficulties with their fellow tenants<br />

began on October 7, 2001, with the receipt of an anonymous<br />

letter in their mailbox. The handwritten letter read as<br />

follows:

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 10<br />

To our Neighbours,<br />

We are concerned about the strong odour that is<br />

flowing into the hallway & other suites on the first<br />

floor. This is a family building with children<br />

living here with asthma & allergies. Please be<br />

aware of this by being more discreet & courteous to<br />

the children & parents that share this home, & our<br />

guests that visit.<br />

Some quick resolutions to this are smoking in<br />

your yard, opening the patio door and windows, and<br />

by placing a towel under your front door when<br />

smoking.<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

Thank you!<br />

[17] On October 9, 2001, Mr. <strong>Young</strong> responded by posting the<br />

following handwritten message by the mailboxes:<br />

To the Hateful person who left the unsigned nasty<br />

note in our mailbox.<br />

Quick Resolution: open your window & stick a towel<br />

under your door everytime (sic) you smell anything.<br />

Thanks!<br />

from 106<br />

Isn’t there enough hate in the world?? Stop<br />

Promoting Hate!! [emphasis original]<br />

That same day, Mr. <strong>Young</strong> contacted the CRHC to discuss the<br />

anonymous letter and to advise the corporation of his<br />

medicinal use of marihuana. To that point, the CRHC had not<br />

received any complaints regarding Mr. <strong>Young</strong>'s marihuana use.<br />

[18] On October 18, 2001, a meeting took place between the<br />

petitioners and two representatives of the CRHC, Ms. Joy and

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 11<br />

Ms. Webster. Mr. <strong>Young</strong> produced his exemption letter from<br />

Health Canada. They discussed the possibility of sealing the<br />

petitioners' door as well as the doors of other tenants.<br />

[19] The following day, the Beechwood Park caretaker,<br />

Mr. Weeks, attended at the petitioners' apartment to install<br />

weather stripping around their door. The petitioners sent the<br />

caretaker away, telling him that they would not permit him to<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

install the weather stripping around their door until he first<br />

installed it around the door of the tenant who had been<br />

complaining about the odour. The caretaker did subsequently<br />

install either a door sweep or weather stripping on the door<br />

of one tenant, Ms. Belson.<br />

[20] Following the visit of the caretaker, the petitioners<br />

sent a letter to Ms. Joy of the CRHC, asking her to take<br />

action with regard to the "disturbing behaviour of [their]<br />

neighbours." Mr. <strong>Young</strong> also posted a note on the outside of<br />

the door to his suite advising fellow tenants of his medical<br />

condition and his exemption from Health Canada.<br />

[21] On October 20, 2001, an anonymous typed letter was placed<br />

under the doors of the Beechwood Park suites, with the<br />

exception of the petitioners' suite. The letter referred to<br />

the "disgusting odor of marijuana that permeates through the<br />

first floor and in most cases into our suites themselves."

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 12<br />

The author identified himself as a concerned father and urged<br />

the other tenants to contact the CRHC to express their<br />

concerns over the marihuana smell.<br />

[22] On October 22, 2001, the petitioners wrote another letter<br />

to Ms. Joy of the CRHC. In the letter, they explained the<br />

steps that they were taking to minimize marihuana smoke in the<br />

building and complained about the CRHC's failure to take<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

action. The petitioners stated that they would not permit<br />

their door to be weather stripped, as they felt that this<br />

would decrease the ventilation in their suite. They concluded<br />

their letter by demanding, amongst other things, that the CRHC<br />

educate all residents of the complex on the medicinal use of<br />

marihuana, increase the security of their suite, compensate<br />

them for the cost of their air purification system and stop<br />

visits from the caretaker without a fixed appointment.<br />

[23] That evening, the petitioners received another anonymous<br />

handwritten note in their mailbox. It complained that the<br />

odour of marihuana emanating from the petitioners' suite was<br />

constant and intolerable. The author asked that Mr. <strong>Young</strong><br />

either smoke on his patio or find an alternate medication.<br />

[24] The petitioners responded by sending a further letter to<br />

Ms. Joy of the CRHC on October 23, 2001, asking her to take<br />

action to stop the complaints which, in the petitioners'

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 13<br />

words, were "causing [them] extreme upset in [their] lives and<br />

destroying the peace and quiet enjoyment of [their]<br />

apartment."<br />

[25] Further conversations took place between Mr. <strong>Young</strong> and<br />

Ms. Joy in the days that followed. On October 26, 2001,<br />

Mr. <strong>Young</strong> retained counsel who sent a letter to the CRHC,<br />

reiterating the petitioners' concerns.<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

The Signs<br />

[26] One point of contention between the petitioners and the<br />

CRHC concerned signs that the <strong>Young</strong>s were displaying in their<br />

suite. The first sign, which the petitioners posted in their<br />

window, depicted a marihuana leaf and contained the words,<br />

"Liberate Medicinal Marijuana." The <strong>Young</strong>s removed this sign<br />

some time in November after being advised by the CRHC that the<br />

posting of signs on windows was contrary to the terms of their<br />

tenancy agreement.<br />

[27] In early January, the petitioners erected a second sign<br />

on an easel in their living room. The sign contained the<br />

words "Marijuana is Medicine", written in lights, and was<br />

visible through the petitioners' window. When the petitioners<br />

did not comply with a written request to remove this sign, the<br />

CRHC served them with an eviction notice. The CRHC later

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 14<br />

withdrew the notice after the <strong>Young</strong>s agreed to take down the<br />

sign.<br />

The Complaints<br />

[28] Beginning on October 19, 2001, and throughout the months<br />

that followed, the CRHC received numerous complaints from<br />

other tenants of Beechwood Park. The complaining tenants<br />

included Mr. Goorevitch, Ms. Belson, Ms. Mercy, Ms. Lort,<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

Ms. Rimek, Ms. Pretty, Mr. and Mrs. Segato and Ms. Beith. The<br />

complaints related to the odour of marihuana, the impact on<br />

the tenants' health and on their visitors, the signs in the<br />

petitioners' apartment, allegations that the petitioners had<br />

given the tenants' names to news media who were requesting<br />

interviews, and behaviour by the petitioners perceived by the<br />

other tenants as harassment.<br />

[29] The CRHC also received numerous requests from Beechwood<br />

Park residents that they be transferred out of the apartment<br />

building. The first of these requests came from Ms. Rimek in<br />

October 2001. On December 24, 2001, Mr. Goorevitch gave the<br />

CRHC notice that he would be terminating his tenancy at<br />

Beechwood Park effective January 31, 2002, because his ex-wife<br />

would not permit their son to spend the night at his apartment<br />

due to the smell of marihuana.

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 15<br />

[30] Ms. Belson contacted the CRHC on January 7, 2002, and<br />

requested an immediate transfer out of the apartment building.<br />

She advised the CRHC that she no longer felt comfortable at<br />

Beechwood Park, that she was feeling harassed by the<br />

petitioners and that she did not want her six year old<br />

daughter exposed to marihuana. She was also concerned about<br />

the message that the petitioners' marihuana signs were sending<br />

to children in the area.<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

[31] On January 8, 2002, Ms. Lort requested a transfer out of<br />

Beechwood Park. She advised the CRHC that she no longer felt<br />

comfortable in the building and was afraid to go out onto her<br />

deck. She later reported that two young men had attended at<br />

her door hoping to purchase marihuana, as they had seen the<br />

petitioners' sign.<br />

[32] On February 25, 2002, Ms. Pretty advised the CRHC that<br />

she wished to be transferred to a different suite in the<br />

apartment so as to be further away from the odour of marihuana<br />

emanating from the petitioners' suite.<br />

[33] Meanwhile, the petitioners continued to make complaints<br />

of their own regarding what they perceived as harassment from<br />

their neighbours and the police, as well as the lack of<br />

assistance from the CRHC. The evidence before me contains a<br />

continuous stream of correspondence from the petitioners or

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 16<br />

their counsel to the CRHC, the police and various politicians<br />

and governmental bodies from October 2001 to November 2002.<br />

The Inspection<br />

[34] On January 24, 2002, Mr. Weeks attended at the<br />

petitioners' residence to perform an annual inspection of<br />

their suite. The petitioners requested that Mr. Weeks not<br />

inspect their bedrooms, the area in their suite in which they<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

grow their marihuana. Mr. Weeks complied with this request.<br />

[35] On February 28, 2002, Ms. Jaarsma of the CRHC wrote to<br />

the petitioners and advised them that the Corporation<br />

continued to receive complaints from other tenants about the<br />

strong odour of marihuana emanating from their suite.<br />

Ms. Jaarsma also expressed concerns that the petitioners'<br />

marihuana cultivation might be exposing the building to excess<br />

moisture and other damage. The letter stated as follows:<br />

... We request that you provide us with information<br />

showing what measures you have previously<br />

implemented and will implement now to minimize the<br />

impact of growing marijuana in your suite. We are<br />

particularly concerned about the noxious smell and<br />

excess moisture.<br />

Finally, I understand that you refused to permit<br />

David Weeks [to] inspect all of your premises during<br />

the Corporation’s annual inspection. This letter<br />

will serve as formal notice that you are required to<br />

allow representatives of the Housing Corporation<br />

[to] inspect the area where you grow your marijuana.

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 17<br />

We have scheduled this inspection for Tuesday,<br />

March 12, 2002 at 10:00 a.m.<br />

[36] On March 8, 2002, the petitioners sent a letter to the<br />

CRHC, stating that they had no obligation to provide the<br />

information demanded in the letter of February 28, 2002. That<br />

day, Steve Kopnyitzky, a property inspector for the CRHC,<br />

posted on the petitioners' door a "notice of entry" to gain<br />

access to the uninspected portions of their suite on March 12,<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

2002, at 10:00 a.m. When Ms. Joy and Mr. Kopnyitzky attended<br />

on that date, the petitioners refused them entry to their<br />

suite.<br />

[37] The CRHC then applied to the Residential Tenancy Branch<br />

for a hearing to obtain an order granting the CRHC access to<br />

the petitioners' suite for the purpose of completing the<br />

annual inspection. A hearing was held on May 16, 2002, before<br />

Arbitrator Knott, who found in favour of the CRHC on May 25,<br />

2002. Arbitrator Knott accepted the CRHC’s contention that<br />

completion of the annual inspection had nothing to do with the<br />

marihuana issue. The arbitrator held that entry for the<br />

purpose of conducting an annual inspection was for a<br />

"reasonable purpose", as permitted in the RTA. The<br />

petitioners have since sought judicial review of that decision

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 18<br />

in the Supreme Court of British Columbia. That matter has not<br />

yet been set down for hearing.<br />

The Notice of Eviction<br />

[38] On April 18, 2002, Ms. Jaarsma sent a final warning<br />

letter to the petitioners, alleging that the odour of<br />

marihuana emanating from their suite amounted to a breach of<br />

Article 13 of their tenancy agreement in that it disturbed,<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

harassed or annoyed other tenants. Ms. Jaarsma requested that<br />

the petitioners take immediate action to remedy this breach or<br />

face eviction.<br />

[39] On July 10, 2002, Ms. Joy delivered a Notice to Terminate<br />

Tenancy (the "Notice") to the petitioners. The reasons given<br />

for the termination read as follows:<br />

The tenants have failed to rectify a breach of<br />

Article #13 (Conduct) of the Tenancy Agreement after<br />

having received written notice to do so. Final<br />

warning letter was given on April 18, 2002. ...<br />

The conduct of the tenants is such that the<br />

enjoyment of other occupants in the residential<br />

property is unreasonably disturbed. ...<br />

Other residents and their guests continue to have<br />

their enjoyment disturbed due to the noxious smell<br />

of marijuana coming from Mr. and Mrs. <strong>Young</strong>'s suite<br />

into the common hallway, and the suites and patio<br />

areas of the other residents. Tenants are<br />

complaining of the overwhelming odor and their<br />

concerns regarding health issues, impact on<br />

children, impact on visitors to the building, child

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 19<br />

custody issues, quality of life, security issues,<br />

etc.<br />

The landlord has concerns regarding the possible<br />

impact on the building due to marijuana cultivation<br />

in Mr. and Mrs. <strong>Young</strong>'s suite. Mr. and Mrs. <strong>Young</strong><br />

have refused to implement a remedy or advise how<br />

they intend to minimize the impact of growing<br />

marihuana in their suite.<br />

The Landlord has suffered damages due to another<br />

tenant vacating the premises due to these concerns.<br />

Two other tenants have transferred to locations<br />

operated by the Landlord in order to escape from the<br />

concerns listed above. The landlord has two other<br />

tenants currently waiting for transfers.<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

On July 16, 2002, the petitioners filed an application for<br />

arbitration under the RTA requesting an order setting aside<br />

the Notice.<br />

The Hearing Before Arbitrator Gilbert<br />

[40] The hearing before Arbitrator Gilbert took place on<br />

July 31, 2002, August 15, 2002 and August 26, 2002. Mr. and<br />

Mrs. <strong>Young</strong> were present on July 31, 2002 only. Their counsel,<br />

Mr. Duhaime, was present throughout. Appearing for the CRHC<br />

were Ms. Joy, Ms. Jaarsma and counsel for the CRHC,<br />

Mr. Borzoni. During the course of the hearing, Arbitrator<br />

Gilbert admitted evidence in the form of sworn viva voce<br />

testimony, affidavits and unsworn letters.<br />

[41] Arbitrator Gilbert issued written reasons on August 29,<br />

2002, in which he dismissed the petitioners' application to

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 20<br />

set aside the Notice. I reproduce the more significant<br />

portions of the arbitrator’s findings of fact and analysis:<br />

From October 19, 2001 to July 22, 2002, the landlord<br />

received approximately 38 oral or written complaints<br />

from other occupants complaining about the odour of<br />

marihuana in their suites or in the hallway and<br />

about the alleged adverse effects of the marihuana<br />

on their health or in their lives generally.<br />

... Almost all of the witnesses who testified<br />

referred to the fact that they knew the tenant or<br />

the tenants were smoking marihuana in their suite<br />

and that the odour in the hallway or the stairwell<br />

or in their own suites resulted from that smoking of<br />

marihuana. Some witnesses testified that the tenant<br />

husband smoked marihuana either on his patio or at<br />

his patio.<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

The tenants argue that as the hallway is<br />

pressurized, it is impossible to smell the marihuana<br />

from the tenants' suite. I disagree. It is common<br />

knowledge in almost every apartment building odours<br />

often escape from the suites into the hallway.<br />

Cooking odours are good [sic] example. Cigarette<br />

smoke is another example. I am satisfied that the<br />

witnesses including the landlord who visited the<br />

premises on several occasions, smelled marihuana<br />

smoke.<br />

Regarding the witnesses for the tenants who did not<br />

smell marihuana in the halls, I do not accept their<br />

evidence. In particular, I do not accept the<br />

evidence of persons who visited the building on one<br />

or two occasions as evidence regarding the presence<br />

of a smell.<br />

... In summary, there is no evidence that anyone<br />

suffered medical effects from the smell of<br />

marihuana. On the other hand, I accept the evidence<br />

of those persons who complain that the adverse<br />

effects of marihuana makes them feel ill or gives<br />

them headaches. I also accept the evidence of those<br />

persons who talk about how the smell of marihuana<br />

slows or frustrates their recovery from another more<br />

serious ailment. ... I accept the fact that many of

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 21<br />

these complaints are based on the perception of the<br />

person smelling the marihuana and not necessarily a<br />

medical diagnosis. However, in my view, the<br />

feelings and sensibilities of the other occupants<br />

are important factors to consider as those feelings<br />

and sensibilities may be central to their enjoyment<br />

of their home.<br />

... Several of the complaining occupants have<br />

requested transfers from this building because of<br />

the smell of marihuana. One of the witnesses has<br />

moved and has bought a townhouse. He says he moved<br />

because he is a non-custodial parent and when his<br />

child came to visit him at the residential property,<br />

the child was exposed to the smell of marihuana. He<br />

was concerned that if the custodial parent found out<br />

that marihuana was being consumed in the residential<br />

property, his access to his child might be denied.<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

The landlord testified that the landlord lost one<br />

month's rent when the occupant who bought a<br />

townhouse left and the landlord was unable to rent<br />

his suite for one month.<br />

The landlord alleges that the tenants have<br />

unreasonably disturbed other occupants contrary to<br />

section 36(1) of the Residential Tenancy Act. ...<br />

The real question is whether the smell of marihuana<br />

somehow entered the suites of the complaining<br />

occupants as they have testified because it is that<br />

type of disturbance that would almost certainly<br />

cross the line and be properly described as an<br />

unreasonable disturbance.<br />

... Did the tenants disturb other tenants?<br />

The answer is yes. Other occupants complained about<br />

being disturbed and about feeling they had lost<br />

enjoyment of their home. They complained about an<br />

odour that made them feel ill or gave them<br />

headaches. Other tenants were adamant that they had<br />

to move. One did move. In my view, the tenants did<br />

disturb other occupants. ... It is inconceivable<br />

that the tenant's right, indeed his need to smoke<br />

marihuana in order to treat his disease, could be<br />

used to defeat the rights of other occupants to<br />

peaceful enjoyment of their homes. As the tenants<br />

disturbed other occupants, they breached article 13

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 22<br />

of the Tenancy Agreement and section 36(1)(h) of the<br />

Residential Tenancy Act. ...<br />

... I believe these witnesses when they say that<br />

they smelled marihuana in their hallway and in their<br />

suites. Based on the evidence of landlord [sic], I<br />

am satisfied ... that the tenants have unreasonably<br />

disturbed other occupants contrary to section<br />

36(1)(a) of the Act.<br />

... I am satisfied that the lawful right or interest<br />

of the landlord and other occupants have been<br />

seriously impaired by an act or omission of the<br />

tenants contrary to section 36(1)(f) of the<br />

Residential Tenancy Act.<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

CONCLUSION<br />

The landlord has established sufficient cause for<br />

ending this tenancy in accordance with sections<br />

36(1)(a)(f) and (h) of the Residential Tenancy Act.<br />

For all of these reasons, the tenants' application<br />

to have the landlord's Notice set aside is<br />

dismissed.<br />

The Review Application<br />

[42] On September 3, 2002, the petitioners filed an<br />

application for review of Arbitrator Gilbert's decision,<br />

pursuant to s. 59(4) of the RTA.<br />

[43] The review application was heard by Arbitrator Katz on<br />

the basis of written submissions from counsel for the<br />

petitioners. The petitioners raised the following two grounds<br />

for review, as described by Arbitrator Katz:<br />

1. That the Tenants were unable to attend the<br />

hearing due to circumstances that could not be

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 23<br />

anticipated and that were beyond his or her<br />

control; and<br />

2. That the Tenants' [sic] have new and relevant<br />

evidence which was not available at the time of<br />

the original hearing in that they could have<br />

given evidence personally if they had been<br />

present at the hearing. [emphasis original]<br />

[44] In written reasons dated October 4, 2002, Arbitrator Katz<br />

determined that the issue of the petitioners' absence during<br />

the hearing had been fully considered by Arbitrator Gilbert<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

and that she had no basis for disturbing his findings in that<br />

regard. Arbitrator Katz concluded that the review was an<br />

attempt to re-argue the same matters raised at the hearing<br />

before Arbitrator Gilbert and that the petitioners had<br />

provided no basis upon which to set aside the decision.<br />

Accordingly, she confirmed the decision to dismiss the<br />

petitioners' application.<br />

[45] On October 7, 2002, counsel for the petitioners filed the<br />

petition currently before me, seeking judicial review of<br />

Arbitrator Gilbert' decision. The petition was later amended<br />

to seek a review of Arbitrator Katz's decision as well.<br />

The Human Rights Complaint<br />

[46] On November 5, 2001, Mr. <strong>Young</strong> filed a discrimination<br />

complaint with the British Columbia Human Rights Commission.

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 24<br />

As the materials relating to this complaint were placed before<br />

Arbitrator Gilbert, I will describe their content here.<br />

[47] The Human Rights complaint alleged that Mr. <strong>Young</strong> had<br />

been subjected to harassment by other residents of Beechwood<br />

Park and that the CRHC "is or should be aware of this<br />

harassment and has fostered or encouraged or not taken any<br />

reasonable measure(s) to prevent this harassment and thereby<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

discriminating [sic] against [Mr. <strong>Young</strong>] as prohibited at<br />

section 8(1) of the Code." The complaint further alleged that<br />

the CRHC discriminated against Mr. <strong>Young</strong> by attempting to seal<br />

only his door, thereby reducing the flow of fresh air through<br />

his residence.<br />

[48] Mr. <strong>Young</strong>'s complaint initially named only the CRHC as<br />

respondent, but was later amended to add as respondents three<br />

fellow tenants, namely, Mr. Goorevitch, Ms. Lort and<br />

Ms. Belson.<br />

[49] On January 23, 2002, Human Rights Officer Betty Down<br />

forwarded her completed Investigation Report to Mary Duffy,<br />

Delegate for the Commissioner of Investigation and Mediation.<br />

Ms. Down reviewed the evidence from Mr. <strong>Young</strong>, including his<br />

complaints that other tenants had directed their children to<br />

run through the hallways with the intention of disturbing the<br />

petitioners, had disturbed their Christmas door decoration,

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 25<br />

had stared at the petitioners and had engaged in conversation<br />

about the petitioners in the apartment hallway. Mr. <strong>Young</strong> had<br />

also complained that a male guest of Ms. Belson's had blown<br />

cigarette smoke into their suite from the hallway through the<br />

space between the door and the frame.<br />

[50] Ms. Down also reviewed the evidence from the CRHC<br />

representatives, Ms. Jaarsma and Ms. Joy, and the evidence<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

from Mr. Goorevitch and Ms. Lort, who generally denied the<br />

petitioners' allegations. Ms. Belson declined to participate<br />

in the investigation.<br />

[51] Ms. Down concluded her report as follows:<br />

70. Based on the evidence as a whole, I recommend<br />

that this complaint be dismissed based on the<br />

analysis above and for the following reasons:<br />

71. The CRHC responded to the Complainant's<br />

complaints about the anonymous letters, and the<br />

letters have stopped being written. The CRHC<br />

also responded to his complaints about tenants<br />

harassing him.<br />

72. It appears the installation of the door sweep<br />

was a reasonable attempt to resolve the problem<br />

of marijuana smoke entering the hallway. The<br />

objective was not to stop the Complainant from<br />

smoking marijuana but to prohibit the smell<br />

from entering the hallway. As the<br />

Complainant's unit is the source of marijuana<br />

smoke, it was reasonable to install the door<br />

sweep on his unit. Although the Complainant<br />

states that this compromises the quality of air<br />

in his unit, the CRHC states that the hallway<br />

is not a source of fresh air.

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 26<br />

Recommendation:<br />

73. It is recommended the complaint be dismissed<br />

under section 27(1)(c) which reads:<br />

27(1) The commissioner of investigation and<br />

mediation may, at any time after a complaint is<br />

filed, dismiss all or part of the complaint if<br />

that commissioner determines that any of the<br />

following apply:<br />

(c) there is no reasonable basis to<br />

justify referring the complaint or<br />

that part of the complaint to the<br />

tribunal for a hearing.<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

[52] Upon receiving a copy of Ms. Down's report, the<br />

petitioners filed further submissions to the Commission. On<br />

May 6, 2002, however, Alan Borden, the delegate of the<br />

Commissioner, advised all parties that he was in agreement<br />

with Ms. Down's analysis and recommendation and that he was<br />

dismissing the complaint.<br />

[53] Counsel for the petitioners wrote to the Commission on<br />

May 24, 2002, requesting a reconsideration of Mr. Borden’s<br />

decision on the basis that Mr. Borden failed to hold a hearing<br />

and to give reasons for dismissing the petitioners'<br />

submissions. On June 13, 2002, David Hosking, another<br />

delegate of the Commissioner, wrote to counsel for the<br />

petitioners, denying the request for reconsideration. He<br />

observed that Mr. Borden had adopted the analysis of Ms. Down<br />

and was entitled to do so. He further stated that, since the

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 27<br />

petitioners' submissions to the Commission raised no<br />

significant new issues, there was no need for Mr. Borden to<br />

provide a detailed response to those submissions.<br />

The <strong>Police</strong><br />

[54] The petitioners' interaction with the <strong>Saanich</strong> police<br />

began on February 19, 2002. On that day, Mr. <strong>Young</strong> phoned<br />

Health Canada regarding the imminent expiry of his medical<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

marihuana exemption. An employee from Health Canada contacted<br />

the SPD later that day to report that Mr. <strong>Young</strong> had threatened<br />

to bomb their offices.<br />

[55] Constable Muth responded to the complaint by attending at<br />

the petitioners' residence. Mr. <strong>Young</strong> denied making any<br />

threat to the Health Canada employee. Constable Muth asked<br />

Mr. <strong>Young</strong> for the expiry date on his medical marihuana<br />

exemption. Mr. <strong>Young</strong> refused to provide this information on<br />

the ground that it was private medical information.<br />

[56] On May 3, 2002, the petitioners delivered a written<br />

complaint to the SPD concerning the behaviour of their<br />

neighbour, Ms. Lort. The substance of the complaint was that<br />

Ms. Lort was continually staring at the petitioners and had<br />

taken a picture of them on one occasion.

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 28<br />

[57] On May 31, 2002, Mr. <strong>Young</strong> phoned 9-1-1 to report that a<br />

tenant had entered his patio. Constables Richmond and Luhowy<br />

attended. Upon learning of Mr. <strong>Young</strong>'s medical marihuana<br />

exemption, Constable Richmond asked to see the exemption<br />

documents. Mr. <strong>Young</strong> initially refused, telling the officers<br />

that they could contact Health Canada if they wished to<br />

confirm his exemption. Mr. <strong>Young</strong> did, ultimately, produce the<br />

first page of his exemption but refused to produce the<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

remainder of the document containing the conditions of the<br />

exemption. Both constables deposed that, when asked to<br />

produce the remainder of the exemption document, Mr. and<br />

Mrs. <strong>Young</strong> became very agitated and yelled at the officers to<br />

leave the suite, which they did. The petitioners maintain<br />

that they asked the officers to leave because the officers<br />

were becoming confrontational.<br />

[58] On July 12, 2002, the SPD received a complaint from a<br />

Beechwood Park tenant regarding the smell of marihuana smoke.<br />

Constables Dyck and Taylor attended at approximately<br />

10:00 p.m. and spoke with the petitioners. Mr. <strong>Young</strong><br />

maintained that he and his wife had returned home only minutes<br />

before the police arrived and could not have been responsible<br />

for any marihuana smell. Mr. <strong>Young</strong> produced the first page of<br />

his medical marihuana exemption and the officers did not

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 29<br />

investigate further. In his affidavit, Constable Dyck deposed<br />

that both Mr. and Mrs. <strong>Young</strong> were hostile during their<br />

conversation and that he had to ask Mrs. <strong>Young</strong> to stop yelling<br />

at him so that he could read the exemption document.<br />

The Petitioners' Complaints about the <strong>Police</strong><br />

[59] As a result of these police visits, the petitioners sent<br />

three separate letters to the SPD articulating complaints<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

against the police department, the attending officers, their<br />

neighbours, the CRHC, the Human Rights Commission, the<br />

Residential Tenancy Branch and Health Canada.<br />

[60] On July 16, 2002, Sergeant Green of the SPD replied by<br />

letter to the petitioners' correspondence. He assured the<br />

petitioners that the police had no hidden agenda and were not<br />

conspiring to have the petitioners evicted. He suggested that<br />

a mediation take place between the police, the CRHC, the<br />

petitioners and their neighbours in order to resolve the<br />

difficulties at Beechwood Park. Constable Green indicated<br />

that as long as his department continued to receive complaints<br />

of marihuana use in the building, they would be forced to<br />

respond. The petitioners did not reply to the mediation<br />

proposal.

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 30<br />

[61] Rather, on July 25, 2002, Mr. <strong>Young</strong> lodged formal<br />

complaints with the SPD regarding the conduct of the police on<br />

February 19, 2002 and May 31, 2002. These complaints were<br />

summarily dismissed.<br />

[62] I do not propose to relate all of the evidence concerning<br />

the petitioners' subsequent interactions with the SPD. It<br />

will suffice to say that Mr. and Mrs. <strong>Young</strong> have sent numerous<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

letters to the <strong>Department</strong> seeking the disclosure and<br />

"correction" of information in police records and laying<br />

complaints against their neighbours and the <strong>Department</strong> itself.<br />

The petitioners are dissatisfied with the response they have<br />

received from the police.<br />

[63] The petitioners also made numerous requests under the<br />

Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act, R.S.B.C.<br />

1996 c. 165, regarding records held by the SPD, the CRHC and<br />

the City of <strong>Saanich</strong>. The petitioners also take issue with the<br />

alleged sharing of their private information between the<br />

police, the CRHC and neighbouring tenants.<br />

Charter Issues<br />

[64] In Action 02/5145, Mr. and Mrs. <strong>Young</strong> allege breaches of<br />

their rights under sections 7, 8 and 15 of the Charter. They<br />

contend that they are "victims of terrible systemic

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 31<br />

discrimination at the hands of bullies, the CRD and the SPD."<br />

This, they say, is because they represent a new vulnerable<br />

group, namely individuals who require the use of marihuana for<br />

health reasons. According to the petitioners, the respondents<br />

stereotyped them as illegal users of marihuana and set about<br />

to fabricate a case for eviction based on the alleged, but in<br />

fact non-existent, presence of smoke in the complex said to<br />

adversely affect neighbours. While the petitioners avoid<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

using the word "conspiracy", the arguments they present, if<br />

accepted, amount to nothing less. In my view, the petitioners<br />

have taken a string of relatively benign unconnected events<br />

and forced them into a conspiracy theory.<br />

[65] There are formidable obstacles along the paths the<br />

petitioners have chosen to follow in presenting their case.<br />

Some arise out of misconceptions as to the availability of<br />

Charter protection when the impugned conduct is by someone<br />

other than a state actor. Others arise out of either the lack<br />

of a proper evidentiary basis for the particular arguments<br />

raised or, as the matter was argued on affidavit evidence,<br />

material conflicts in the evidence.<br />

[66] The following are examples of the obstacles to which I<br />

refer. The petitioners claim Charter relief arising, in part,<br />

out of the conduct of individual neighbours, who are clearly

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 32<br />

not government actors. I am simply not persuaded on the<br />

evidence before me that any of these individuals acted in<br />

concert with any of the respondents to discriminate against<br />

the petitioners. Nor do I accept that the police had any<br />

interest whatsoever in the eviction of the petitioners. Other<br />

necessary factual underpinnings for the conspiracy argument,<br />

including the alleged improper sharing of information between<br />

the police and the CRHC, were not established in evidence.<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

[67] One of the significant procedural obstacles is that the<br />

CRHC is not a party to the first proceeding, even though the<br />

complaints are inextricably linked with the decision by the<br />

CRHC, as the landlord, to seek eviction and the steps taken to<br />

achieve that end. Even if the CRHC was a party, I am not<br />

persuaded that it was a government actor for purposes of the<br />

Charter.<br />

[68] Another obstacle is created by the petitioners' failure<br />

to comply with s. 8 of the Constitutional Question Act,<br />

R.S.B.C. 1996, c. 68, which requires that notice be given to<br />

the Attorney General of Canada and the Attorney General of<br />

British Columbia of a hearing at which constitutional remedies<br />

are sought as they are here.<br />

[69] I observe that the petitioners do not contend that the<br />

relevant provisions of the RTA fail to comply with Charter

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 33<br />

requirements. I find no evidence that the CRHC acted pursuant<br />

to any policy with a view to discriminating against the<br />

petitioners for using marihuana. Instead, I am satisfied on<br />

the evidence that the landlord attempted to take reasonable<br />

steps to accommodate the petitioners, but the petitioners<br />

refused to cooperate. The CRHC was entitled to rely on the<br />

statute and did so in seeking to evict.<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

[70] In the course of proceedings under the RTA, Mr. and<br />

Mrs. <strong>Young</strong> contended, as they did before me, that there was no<br />

possible smell in the apartment complex associated with<br />

Mr. <strong>Young</strong>'s use of marihuana. Thus, the petitioners continue<br />

to rely on the lack of smell as a starting point for many of<br />

their arguments, yet the arbitrator clearly found otherwise<br />

based on the evidence before him. That finding formed the<br />

basis for refusing to set aside the Notice and was never<br />

overcome on the evidence before me.<br />

[71] Because the petitioners are self-represented, I<br />

considered inviting an application to amend: either to add<br />

the CRHC as a party or to allege that it was acting throughout<br />

on behalf of the CRD, which is indisputably a government<br />

actor. I then further considered referring any necessary<br />

factual issues to the trial list to avoid the problems

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 34<br />

associated with determining some aspects of the facts from<br />

conflicting affidavits.<br />

[72] I decided not to take these steps as I am persuaded that<br />

the petitioners' claims cannot possibly succeed. Even<br />

assuming that the CRHC was to be added as a party and that it<br />

was a government actor, taking the most favourable view<br />

possible of the evidence from the petitioners' perspective,<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

the Charter challenges are still doomed to fail.<br />

[73] Before proceeding further, I wish to briefly address why<br />

it is necessary to assume that the CRHC is a government actor.<br />

On the evidence before me, I would conclude otherwise.<br />

CRHC as a Government Actor<br />

[74] The CRD and the CRHC are separate entities. The CRD<br />

concedes that it is a government actor in that it is a branch<br />

of government with legislated responsibilities. The CRHC, on<br />

the other hand, is a private company that is not owned,<br />

operated or controlled by the CRD.<br />

[75] The sole purpose of the CRHC is to provide housing. It<br />

manages a portfolio of over 1,200 units. Pursuant to a<br />

Special Resolution passed in 1994, it cannot carry on any<br />

other business. A majority of the Board of Directors are also<br />

sitting Directors of the CRD, but the CRD has no involvement

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 35<br />

in the day-to-day running of the business of the corporation<br />

and had no involvement in any of the decisions or steps taken<br />

respecting the petitioners.<br />

[76] Section 32 of the Charter limits its application to the<br />

legislative, executive and administrative branches of<br />

government. The Charter does not apply to litigation between<br />

private parties. See R.W.D.S.U. v. Dolphin Delivery Ltd.,<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

[1986] 2 S.C.R. 573. In McKinney v. University of Guelph,<br />

[1990] 3 S.C.R. 229 at 261-62, La Forest J., referring to<br />

s. 32, stated:<br />

These words give a strong message that the<br />

Charter is confined to government action. This<br />

Court has repeatedly drawn attention to the fact<br />

that the Charter is essentially an instrument for<br />

checking the powers of government over the<br />

individual. ...<br />

The exclusion of private activity from the<br />

Charter was not a result of happenstance. It was a<br />

deliberate choice which must be respected. ...<br />

The CRHC, unlike the CRD, is not part of the legislative,<br />

executive or administrative branch of government.<br />

[77] According to McKinney, even if the CRHC were a<br />

governmental body, it would also have to be engaged in that<br />

capacity in respect of the conduct sought to be subjected to<br />

Charter scrutiny. There is no evidence before me to suggest<br />

that any action taken in respect of the petitioners was either

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 36<br />

an action of government or on behalf of government. All the<br />

decisions and steps taken by the CRHC were as a private<br />

landlord pursuant to the tenancy agreement and the RTA. I do<br />

not accept that the CRHC was a government actor.<br />

The Assumptions<br />

[78] I return now to explain my decision not to refer these<br />

matters to the trial list. I intend to address only those<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

issues put forward by the petitioners that were of potential<br />

significance. As I have earlier indicated, I am persuaded<br />

that the petitioners' Charter challenges cannot succeed,<br />

regardless of whether I accept their view of the evidence.<br />

Thus, my analysis of the issues raised will be based, in each<br />

case, on a number of assumptions favourable to the<br />

petitioners. Those assumptions are as follows:<br />

• Mr. <strong>Young</strong>’s disability leaves him with no choice but<br />

to smoke marihuana and to smoke it in his residence.<br />

• The CRHC is a government actor.<br />

• In evicting Mr. <strong>Young</strong>, the CRHC was acting in<br />

furtherance of a policy to evict persons whose<br />

marihuana smoking disturbed other tenants.

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 37<br />

The one key assumption that I cannot make in the petitioners'<br />

favour is that the neighbours' complaints of marihuana smell<br />

were unfounded. The arbitrator came to the opposite<br />

conclusion based on the evidence before him, as he was<br />

entitled to do. For reasons that I will set out later under<br />

the heading Review of the Arbitrator's Findings of Fact, it is<br />

not open to me to come to a different conclusion on this<br />

point.<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

Section 15<br />

15.(1) Every individual is equal before and under<br />

the law and has the right to the equal<br />

protection and equal benefit of the law<br />

without discrimination and, in particular,<br />

without discrimination based on race,<br />

national or ethnic origin, colour,<br />

religion, sex, age or mental or physical<br />

disability.<br />

Issues<br />

[79] The petitioners contend that they were flagrantly<br />

harassed by intolerant neighbours and that the CRD and the<br />

police failed to provide necessary assistance. According to<br />

the petitioners, these failures stemmed from discriminatory<br />

beliefs about the medical use of marihuana. In essence, the<br />

petitioners argue that the CRD has a duty to accommodate<br />

Mr. <strong>Young</strong>'s disability by controlling the behaviour of other<br />

tenants and not seeking to evict the petitioners.

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 38<br />

[80] Similarly, the petitioners complain that the police<br />

failed to adequately investigate and initiate prosecutions as<br />

was necessary to prevent harassment by intolerant neighbours.<br />

According to the petitioners, the police refused to fulfil<br />

their duty because of discriminatory beliefs about the medical<br />

use of marihuana. The petitioners completely failed to offer<br />

any evidentiary foundation capable of supporting the<br />

allegations against the police and it is unnecessary for me to<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

analyze them.<br />

[81] Ignoring the reference to the CRD and based instead on<br />

the assumptions set out earlier, I find no possible breach of<br />

s. 15 arising out of any discriminatory practice.<br />

The "Zero-Tolerance" Policy<br />

[82] If the CRHC had evicted Mr. <strong>Young</strong> pursuant to a policy to<br />

evict sufferers of multiple sclerosis, this would constitute<br />

direct discrimination on the basis of the enumerated ground of<br />

physical disability. A section 15 Charter violation would be<br />

established.<br />

[83] The CRHC did not evict Mr. <strong>Young</strong> because he suffers from<br />

multiple sclerosis. As such, direct discrimination cannot be<br />

made out on these facts. I must also consider, however, the

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 39<br />

possibility of adverse effect discrimination. As Iacobucci J.<br />

said in Symes v. Canada, [1993] 4 S.C.R. 695 at 755:<br />

... it is clear that a law may be discriminatory<br />

even if it is not directly or expressly<br />

discriminatory. In other words, adverse effects<br />

discrimination is comprehended by s. 15(1) ...<br />

Likewise, in Andrews v. Law Society of British Columbia,<br />

[1989] 1 S.C.R. 143, McIntyre J. stated at p. 164, "identical<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

treatment may frequently produce serious inequality."<br />

McIntyre J. went on to say at p. 165, "a law expressed to bind<br />

all should not because of irrelevant personal differences have<br />

a more burdensome or less beneficial impact on one than<br />

another."<br />

[84] In Eldridge v. British Columbia (Attorney General),<br />

[1997] 3 S.C.R. 624, La Forest J. said at para. 64:<br />

Adverse effects discrimination is especially<br />

relevant in the case of disability. The government<br />

will rarely single out disabled persons for<br />

discriminatory treatment. More common are laws of<br />

general application that have a disparate impact on<br />

the disabled. ...<br />

[85] Thus, the mere fact that the CRHC applied the same rules,<br />

or more accurately, sought the application of the same<br />

provincial legislation to Mr. <strong>Young</strong>, as it would have to any<br />

other tenant who smoked marihuana in the building, does not

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 40<br />

resolve the issue. I must consider whether the policy had a<br />

more burdensome effect on Mr. <strong>Young</strong> because of his disability.<br />

[86] In Ontario (Human Rights Commission) v. Simpsons-Sears<br />

Ltd. (1985), 23 D.L.R. (4th) 321 at 332 (S.C.C.), McIntyre J.<br />

provided the following explanation of adverse effect<br />

discrimination in the context of employment policies:<br />

A distinction must be made between what I would<br />

describe as direct discrimination and the concept<br />

already referred to as adverse effect discrimination<br />

in connection with employment. Direct<br />

discrimination occurs in this connection where an<br />

employer adopts a practice or rule which on its face<br />

discriminates on a prohibited ground. For example,<br />

"No Catholics or no women or no blacks employed<br />

here." There is, of course, no disagreement in the<br />

case at bar that direct discrimination of that<br />

nature would contravene the Act. On the other hand,<br />

there is no concept of adverse effect<br />

discrimination. It arises where an employer for<br />

genuine business reasons adopts a rule or standard<br />

which is on its face neutral, and which will apply<br />

equally to all employees, but which has a<br />

discriminatory effect upon a prohibited ground on<br />

one employee or group of employees in that it<br />

imposes, because of some special characteristic of<br />

the employee or group, obligations, penalties, or<br />

restrictive conditions not imposed on other members<br />

of the work force. ...<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

It could be said that the CRHC has, for legitimate business<br />

reasons, adopted a policy that has had a disproportionate<br />

adverse effect on Mr. <strong>Young</strong>. The policy could be framed in<br />

various ways, but, in its essence, it dictates that tenants

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 41<br />

whose marihuana smoking disturbs other tenants will be<br />

evicted.<br />

[87] Arguably, such a policy or conduct amounts to adverse<br />

effect discrimination. Though the rule, "No marihuana smoke"<br />

applies to all tenants equally, the effect of the rule is to<br />

impose a greater penalty or restrictive condition on Mr. <strong>Young</strong><br />

because of his need to smoke marihuana, a characteristic<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

incidental to his disability. Mr. <strong>Young</strong> is, so the argument<br />

goes, by reason of this rule, effectively denied access to<br />

certain social housing.<br />

[88] I accept that such a finding (made possible only by the<br />

assumptions adopted at the outset) would establish the type of<br />

discrimination contemplated by s. 15, as defined by<br />

Iacobucci J. in Law v. Canada (Minister of Employment and<br />

Immigration), [1999] 1 S.C.R. 497 at para. 88. The policy<br />

fails to take into account Mr. <strong>Young</strong>’s already disadvantaged<br />

position as a disabled person, resulting in substantively<br />

differential treatment between him and others on the basis of<br />

his need to smoke marihuana. The differential treatment is<br />

based on a characteristic incidental to his physical<br />

disability, which is an enumerated ground. Lastly, the<br />

differential treatment imposes a burden or withholds a benefit<br />

from Mr. <strong>Young</strong> in a manner that has the effect of perpetuating

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 42<br />

or promoting the view that he is less capable or worthy of<br />

recognition or value as a human being or as a member of<br />

Canadian society, equally deserving of concern, respect, and<br />

consideration.<br />

[89] The s. 15 prohibition on adverse effect discrimination is<br />

not, however, absolute. The Supreme Court of Canada has held<br />

that a law that is prima facie discriminatory may nonetheless<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

be justifiable under s. 1. In Eldridge, the court confirmed<br />

that the test for justifying adverse effect discrimination<br />

under s. 1 is that set out in R. v. Oakes, [1986] 1 S.C.R.<br />

103. In Egan v. Canada, [1995] 2 S.C.R. 513, Iacobucci J.<br />

summarized that test as follows at para. 182:<br />

... First, the objective of the legislation must be<br />

pressing and substantial.<br />

Second, the means chosen to attain this legislative<br />

end must be reasonable and demonstrably justifiable<br />

in a free and democratic society. In order to<br />

satisfy the second requirement, three criteria must<br />

be satisfied: (1) the rights violation must be<br />

rationally connected to the aim of the legislation;<br />

(2) the impugned provision must minimally impair the<br />

Charter guarantee; and (3) there must be a<br />

proportionality between the effect of the measure<br />

and its objective so that the attainment of the<br />

legislative goal is not outweighed by the<br />

abridgement of the right. In all s. 1 cases the<br />

burden of proof is with the government to show on a<br />

balance of probabilities that the violation is<br />

justifiable.

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 43<br />

It seems to me that the CRHC has easily established that the<br />

objective of their policy, to ensure that all tenants can<br />

peacefully enjoy their residences, is pressing and<br />

substantial. It is also apparent that a policy of prohibiting<br />

offensive odours is rationally connected to that objective.<br />

[90] On the issues of minimal impairment and proportionality,<br />

unique considerations come into play in the context of adverse<br />

<strong>2003</strong> <strong>BCSC</strong> <strong>926</strong> (<strong>CanLII</strong>)<br />

effect discrimination. At para. 79 of Eldridge, La Forest J.<br />

explained as follows:<br />

It is also a cornerstone of human rights<br />

jurisprudence, of course, that the duty to take<br />

positive action to ensure that members of<br />

disadvantaged groups benefit equally from services<br />

offered to the general public is subject to the<br />

principle of reasonable accommodation. The<br />

obligation to make reasonable accommodation for<br />

those adversely affected by a facially neutral<br />

policy or rule extends only to the point of "undue<br />

hardship"; see Simpsons-Sears, supra, and Central<br />

Alberta Dairy Pool, supra. In my view, in s. 15(1)<br />

cases this principle is best addressed as a<br />

component of the s. 1 analysis. Reasonable<br />

accommodation, in this context, is generally<br />

equivalent to the concept of "reasonable limits".<br />

It should not be employed to restrict the ambit of<br />

s. 15(1).<br />

[91] Similar tests were suggested in Ayangma v. Prince Edward<br />

Island, [2001] P.E.I.J. No. 105 (S.C. A.D.), leave to appeal<br />

refused [2001] S.C.C.A. No. 653, where McQuaid J.A. wrote as<br />

follows regarding the decision in Ontario v. Simpsons-Sears:

<strong>Young</strong> v. <strong>Saanich</strong> <strong>Police</strong> <strong>Department</strong>, et al Page 44<br />

Adverse effect discrimination will be limited<br />

to a smaller group as it was in the above case which<br />

involved the termination of an employee who was<br />

unavailable for work on Friday evenings and Saturday<br />

because of her religion. While the right to<br />

practice her religion was not absolute, the court<br />