interviewing skills for undergraduate psychology students

interviewing skills for undergraduate psychology students

interviewing skills for undergraduate psychology students

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

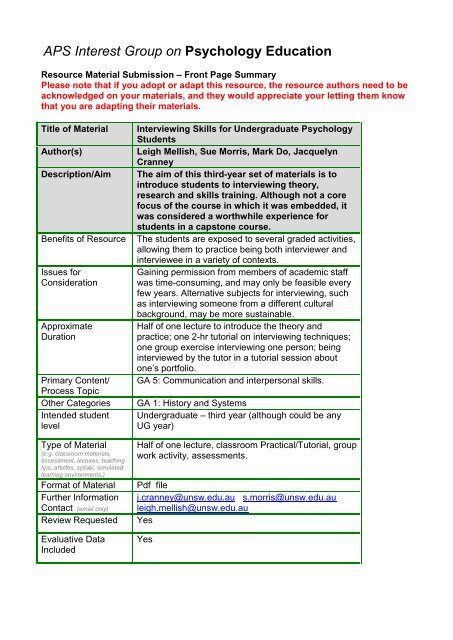

APS Interest Group on Psychology Education<br />

Resource Material Submission – Front Page Summary<br />

Please note that if you adopt or adapt this resource, the resource authors need to be<br />

acknowledged on your materials, and they would appreciate your letting them know<br />

that you are adapting their materials.<br />

Title of Material<br />

Author(s)<br />

Description/Aim<br />

Benefits of Resource<br />

Issues <strong>for</strong><br />

Consideration<br />

Approximate<br />

Duration<br />

Primary Content/<br />

Process Topic<br />

Other Categories<br />

Intended student<br />

level<br />

Type of Material<br />

(e.g. classroom materials,<br />

assessment, lectures, teaching<br />

tips, articles, syllabi, simulated<br />

learning environments.)<br />

Format of Material<br />

Further In<strong>for</strong>mation<br />

Contact (email only)<br />

Review Requested<br />

Evaluative Data<br />

Included<br />

Interviewing Skills <strong>for</strong> Undergraduate Psychology<br />

Students<br />

Leigh Mellish, Sue Morris, Mark Do, Jacquelyn<br />

Cranney<br />

The aim of this third-year set of materials is to<br />

introduce <strong>students</strong> to <strong>interviewing</strong> theory,<br />

research and <strong>skills</strong> training. Although not a core<br />

focus of the course in which it was embedded, it<br />

was considered a worthwhile experience <strong>for</strong><br />

<strong>students</strong> in a capstone course.<br />

The <strong>students</strong> are exposed to several graded activities,<br />

allowing them to practice being both interviewer and<br />

interviewee in a variety of contexts.<br />

Gaining permission from members of academic staff<br />

was time-consuming, and may only be feasible every<br />

few years. Alternative subjects <strong>for</strong> <strong>interviewing</strong>, such<br />

as <strong>interviewing</strong> someone from a different cultural<br />

background, may be more sustainable.<br />

Half of one lecture to introduce the theory and<br />

practice; one 2-hr tutorial on <strong>interviewing</strong> techniques;<br />

one group exercise <strong>interviewing</strong> one person; being<br />

interviewed by the tutor in a tutorial session about<br />

one’s portfolio.<br />

GA 5: Communication and interpersonal <strong>skills</strong>.<br />

GA 1: History and Systems<br />

Undergraduate – third year (although could be any<br />

UG year)<br />

Half of one lecture, classroom Practical/Tutorial, group<br />

work activity, assessments.<br />

Pdf file<br />

j.cranney@unsw.edu.au s.morris@unsw.edu.au<br />

leigh.mellish@unsw.edu.au<br />

Yes<br />

Yes

Interviewing Skills <strong>for</strong> Undergraduate Psychology Students<br />

Leigh Mellish, Sue Morris, Mark Do and Jacquelyn Cranney<br />

University of NSW, 2012<br />

Aim<br />

The aim of this component of the third-year capstone course (in which it was embedded) was to introduce<br />

<strong>students</strong> to <strong>interviewing</strong> <strong>skills</strong>, and to provide them with scaffolded tasks requiring the use of these <strong>skills</strong>.<br />

Description<br />

Students were given half of a lecture on <strong>interviewing</strong> <strong>skills</strong>. This was followed by a 2-hour tutorial/practical<br />

focussed entirely on <strong>interviewing</strong> <strong>skills</strong>, in which every student had an opportunity to either interview or be<br />

interviewed by another student. The tutorial also contained activities pertaining to Effective Questioning and<br />

Active Listening. The <strong>students</strong> particularly enjoyed this tutorial, especially where the interviewees were<br />

asked to behave in a way that was particularly challenging <strong>for</strong> the interviewer.<br />

Following the tutorial, <strong>students</strong> were asked to complete an assessment which required them to interview an<br />

assigned academic staff member in the School of Psychology. In small groups, <strong>students</strong> were asked to design<br />

a series of interview questions to enable them to obtain the content required to construct a mock Wikipedia<br />

page on the academic staff member. The content of that group exercise was related to history and systems<br />

in <strong>psychology</strong>, but the focus of the interview could be quite different, <strong>for</strong> example, <strong>interviewing</strong> a migrant<br />

about aspects of their (cross-) cultural experience. Finally, each student was briefly interviewed by their<br />

tutor in the final tutorial session on their portfolio, in a manner that bore some similarities to a job<br />

interview.<br />

Scholarship/Evaluation of Student Learning/Continuous Improvement:<br />

Student feedback indicated that the <strong>students</strong> saw the value of the different components involved in the<br />

interview tasks (ratings on a 5 point scale where 1=strongly disagree and 5=strongly agree). At the end of the<br />

tutorial, <strong>students</strong> gave the following ratings:<br />

N=97<br />

Question<br />

Mean (SD)<br />

1) I found the lecture content effective 3.67 (0.97)<br />

2) I found the lecture style effective 3.08 (1.17)<br />

3) I found the tutorial content effective 4.20 (0.77)<br />

4) I found the tutorial activities effective 4.40 (0.84)<br />

During the final course/unit evaluation, <strong>students</strong> gave the following ratings:<br />

My <strong>interviewing</strong> <strong>skills</strong> improved considerably in this course. 3.47 (1.00)<br />

The practical on <strong>interviewing</strong> was worthwhile/valuable 3.77 (1.11)<br />

Student comments during final course evaluation, relevant to this material:<br />

I would have to say the best thing was the practicals we received on <strong>interviewing</strong> tips<br />

The <strong>interviewing</strong> tutorial in Week 4 allowed us to see the positives and negatives of different interview styles.<br />

It also teaches us to become proactive listeners, a feature that employers look at closely.<br />

The most engaging activity was the Contemporary Figures assessment, which solidified communication and<br />

<strong>interviewing</strong> <strong>skills</strong> through practical experience. Interviewing [staff member’s name] proved very rewarding<br />

as both an exercise <strong>for</strong> skill development and genuine education about the daily life of a research<br />

psychologist.<br />

Notes regarding continuous improvement<br />

It is likely that in future iterations of this component of the course we would need to have an exercise that<br />

does not involve <strong>interviewing</strong> academic staff members, as it is not sustainable from one year to the next.<br />

Postgraduate research <strong>students</strong> may be an alternative. Otherwise, a somewhat different focus of<br />

<strong>interviewing</strong> (e.g., <strong>interviewing</strong> someone from a different culture) could be employed. Overall, it would have<br />

been desirable to have <strong>interviewing</strong> <strong>skills</strong> embedded in a broader course on the psychological science of<br />

communication and interpersonal <strong>skills</strong>.

Interviewing Lectures

INTERVIEWING SKILLS<br />

FOR UNDERGRADUATE<br />

PSYCHOLOGY STUDENTS<br />

Interviewing Skills<br />

For Undergraduate<br />

Psychology<br />

Students<br />

Leigh Mellish, Sue Morris, Mark Do &<br />

Jacquelyn Cranney<br />

The School of Psychology, UNSW<br />

“The beginning of interview wisdom is to<br />

appreciate the big difference between what you<br />

want to know and how you should ask (1)”<br />

Support <strong>for</strong> the development of this document has been provided by an<br />

Australian Learning and Teaching Council* (now Office <strong>for</strong> Learning and<br />

Teaching) National Teaching Fellowship (2010-2012) to Jacquelyn<br />

Cranney. Please contact the School of Psychology, UNSW <strong>for</strong> further<br />

in<strong>for</strong>mation.<br />

*ALTC and OLT are initiatives of the Australian Government. The views expressed in this<br />

report do not necessarily reflect the views of the Australian Government. You may not use<br />

this work <strong>for</strong> commercial purposes.

Outcomes of the Interviewing Lecture and Tutorial in this course (PSYC3011, Psychology,<br />

UNSW)<br />

After the completion of this <strong>interviewing</strong> component, <strong>students</strong> will:<br />

1. Be able to articulate the key <strong>skills</strong> required <strong>for</strong> a range of interview types.<br />

2. Be more confident in their ability to apply these key <strong>skills</strong> to a variety of<br />

<strong>interviewing</strong> contexts.<br />

3. Be more aware of areas that they need to further develop when communicating in<br />

everyday situations.<br />

Format of the interview<br />

Planning the interview:<br />

Planning <strong>for</strong> an interview is an important process to understand what approach to take, and to<br />

develop appropriate questions to obtain the desired in<strong>for</strong>mation. Planning can also increase<br />

awareness of potential pitfalls (e.g., playing devil’s advocate with the questions), and areas where<br />

one may need to show more sensitivity (e.g., controversial topics, minority groups). It is also critical<br />

to ensure that appropriate time is allocated to various topics. Most interviews have some degree of<br />

planning involved as can be seen in job interviews, in which questions are targeted to assess role<br />

relevant <strong>skills</strong>.<br />

The first decision in the planning process is the structure of an interview. There are 3 main types of<br />

structure:<br />

1) A fully-structured interview - all questions are delivered to each respondent consistently,<br />

regardless of their responses.<br />

2) A semi-structured interview - there are some set questions that are delivered to all<br />

respondents. However, other questions vary depending on earlier responses.<br />

3) An un-structured interview - an exploratory interview with few or no set questions.<br />

Clearly more planning is needed in structured interviews than unstructured interviews, which enable<br />

more consistency, <strong>for</strong> example when one needs to compare job candidates. It has been found that<br />

structured interviews are more valid <strong>for</strong> hiring employees (McDaniel et al., 1994).<br />

A simple structure is where each question is independent, just like a questionnaire (e.g., Q1R1,<br />

Q2R2, Q3R3). More complex structures come about when there are responses to one question,<br />

which should be followed up on (i.e., probing to get a better understanding of the response: Q1 “How<br />

do you feel?”, R1 “Sad”, Q2 “Why do you feel sad”). Even more complexity can occur when there<br />

are multiple factors mentioned in a response (e.g., R2 “Because my husband is a jerk, and my kids<br />

hate me, and my cat died!”). The interviewer has the complex task of trying to work through multiple<br />

issues, which can result in bias if they assume that one issue is more important (or easier to talk<br />

about, or piques their own curiosity), and fails to discuss the other issues. The interviewer may also<br />

simply <strong>for</strong>get as the conversation continues to return to discuss the other factors.<br />

Interview structure checklist<br />

A more complex interview structure requires additional cognitive demands to ensure that the<br />

interview is on track. Consider these questions in understanding your control of the interview:<br />

‣ Are you on track? Do you know which way the sequence of questions and responses is leading?

‣ Has the respondent accidentally or intentionally led you into a topic which you did not intend?<br />

‣ If so, how can you get back on track?<br />

‣ Have you taken account of each aspect of a complex response or only followed up on one aspect<br />

and neglected others?<br />

‣ Is there consistency between different components of the response? Is there anything confusing<br />

that you need to clarify?<br />

An interview can have various structures and substructures. It is important to be aware of the<br />

objective of the interview, to ensure that you choose the structure that will maximise the in<strong>for</strong>mation<br />

that you can obtain within the allocated time frame.<br />

Understanding Objectives and Formulating Relevant Questions<br />

1. Clarifying the<br />

objectives of<br />

the interview<br />

2. Specifying the<br />

in<strong>for</strong>mation<br />

needed to<br />

achieve those<br />

objectives<br />

3. Formulating<br />

concrete<br />

questions<br />

designed to<br />

obtain the<br />

in<strong>for</strong>mation<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

What is it you want to know?<br />

What is the in<strong>for</strong>mation being used <strong>for</strong>?<br />

What direction do you want to take?<br />

Will different answers affect the direction that the interview<br />

takes?<br />

Why do you want to know this?<br />

o Is it important, or are you just curious?<br />

Are you speaking the same language?<br />

Have you defined the terms? Is there an established term?<br />

Clarify &/or define it<br />

o You should not make assumptions e.g., partner may be<br />

same- or opposite- sex<br />

Formulating the questions should serve as a guide to stay on<br />

track<br />

If you decide to probe a response, think about where it will take<br />

you, and whether you will need to return to where you<br />

digressed.<br />

Are you using open-ended or closed questions?<br />

Open ended are useful <strong>for</strong> gathering in<strong>for</strong>mation, closed<br />

questions <strong>for</strong> clarifying in<strong>for</strong>mation.<br />

Interview stages<br />

Once the planning has occurred, the actual interview can be considered to occur in 3 stages:<br />

1) The opening phase<br />

2) The main body<br />

3) The closing phase<br />

Each phase serves a different purpose, and emphasises different <strong>skills</strong>. For example, building<br />

rapport is most essential in the opening phase, whereas active listening is most crucial <strong>for</strong> the<br />

main body of the interview.

Opening the<br />

interview:<br />

The main body<br />

of the interview<br />

The closing<br />

phase of an<br />

interview<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Introduce yourself<br />

Establish your credentials (role, employer, affiliation)<br />

Introduce the methods to be used to record the in<strong>for</strong>mation<br />

In<strong>for</strong>m how long the interview will take (don’t under-estimate)<br />

Start with easy questions, and/or small talk to build rapport, and<br />

then transition into more stressful /difficult questions<br />

Develop the main themes and explore the responses<br />

Move from general in<strong>for</strong>mation to more specific in<strong>for</strong>mation<br />

(using open questions as well as closed questions)<br />

Begin with the least threatening content to establish rapport and<br />

trust be<strong>for</strong>e exploring sensitive or confronting topics.<br />

A long interview can be tiring (emotionally and cognitively). It can<br />

be important to ensure that it doesn’t end too abruptly gradual<br />

winding down is the best.<br />

It may be useful to recap the key themes or ideas that you have<br />

gleaned, to ensure that you have captured the essence of what has<br />

been said.<br />

If part of a series, a link will need to be established between this<br />

interview and the next.<br />

If appropriate, ask if they have any questions <strong>for</strong> you. Be selective<br />

in your disclosure.<br />

Thank the individual <strong>for</strong> their interest and ef<strong>for</strong>t.<br />

Questions<br />

You will probably use a range of question types during the interview. Be aware that the questions<br />

you select will greatly influence the direction of the interview. You may need to ask a question in<br />

more than one way in order to elicit the in<strong>for</strong>mation you are after.<br />

Open<br />

ended<br />

Useful when the interview is exploratory, or when the emphasis is on<br />

discovering the respondent’s perspective on events.<br />

questions Can motivate by allowing free association, giving recognition, allowing<br />

the interviewer to be a sympathetic listener, and avoiding more specific<br />

questions that might alert the respondent to ego-threatening in<strong>for</strong>mation.<br />

Disadvantage is that they are liable to a larger proportion of irrelevant<br />

in<strong>for</strong>mation than narrower questions, and some detail may be missing.<br />

Useful in understanding the chronological order of events, and assessing<br />

the vocabulary of the respondent.<br />

Closed<br />

ended<br />

Closed questions are more readily used when the objectives of the<br />

interview are known.<br />

questions They may also be useful <strong>for</strong> more reluctant respondents (whether <strong>for</strong><br />

reasons of motivation or language), or <strong>for</strong> those giving in<strong>for</strong>mation not<br />

particularly important to them.<br />

Closed questions are usually preceded by open questions which provide a<br />

sense of the context in which the questions are being asked.<br />

Recommendation:<br />

Broad, open-ended when you begin your dialogue. These are the least suggestive<br />

(leading)

Move from open to more specific (close-ended) when necessary<br />

A combination of both is required to get the bigger picture as well as clarification of<br />

important details<br />

In addition to Open and Closed questions, there are other question types with different<br />

purposes:<br />

Probing Questions:<br />

A probing question is a question that follows up on the answers to previous questions. These can be<br />

used to:<br />

Clarify or search <strong>for</strong> reasons behind previous answers<br />

Search <strong>for</strong> inconsistencies<br />

Help the respondent deal with a topic that has been difficult to speak about<br />

Revisit responses from earlier in the interview<br />

Clarifying/<br />

elaborating<br />

Expanding/<br />

Encouraging<br />

Checking<br />

consistency<br />

Revising<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

“Can you tell me more about…?”<br />

“Could you explain a little more about…?”<br />

“Can you give me an example?”<br />

“Then what happened next?”<br />

“Uh huh’ mm ‘I see’ ‘go on’ ‘please continue’<br />

“You said …but now you have told me…How do you explain that?<br />

Can you tell me more?”<br />

“Let’s go back to what you told me be<strong>for</strong>e about… In the light of<br />

what you told me later, can you now tell me more about…?”<br />

Motivating questions<br />

There are a few factors that influence a respondent’s motivation to respond. Threatening the<br />

respondent’s ego will decrease their motivation, whilst making them feel better about themselves or<br />

recognising the importance of their response will increase their motivation. It is there<strong>for</strong>e important<br />

to choose words that do not prejudice or do not imply anything unintended.<br />

Minimising<br />

ego threat<br />

Maximising<br />

recognition<br />

Using neutral words can reduce threat<br />

Contextual prefacing can reduce threat – by indicating you are aware<br />

of the issue<br />

o “We are trying to understand the way in which an individual ends<br />

up in a certain course at university. A student may find themselves<br />

in a course that was not their first choice, because of things like<br />

grades, influence of family and friends, or financial considerations.<br />

So let me start by asking….How did you end up studying law?”<br />

One way to motivate a response is to demonstrate you recognise the<br />

respondent’s view as unique. e.g., “There are many studies looking at how<br />

university <strong>students</strong> end up in a particular course. However, these studies<br />

do not adequately ask the student their perspective. As a first year<br />

student, who has just been through the process, I’m sure you can give an<br />

accurate analysis, and I would there<strong>for</strong>e like to hear your view”

Biased Questions<br />

Biased questions are questions that when asked will be likely to elicit a skewed answer. These<br />

questions should be avoided as they can affect the whole structure of the interview, as a biased<br />

question may lead to biased and/or hostile responses. It is the interviewer’s responsibility to avoid<br />

bias. An example of a biased question is the following (it is also a leading question):<br />

“You don’t…, do you?”<br />

“You don’t support gay marriage…., do you?”<br />

“You know smoking causes cancer, don’t you?”<br />

These questions suggest there is a ‘correct’ response, which most people would endorse.<br />

Loaded Questions<br />

A question is loaded when it is phrased in such a way that it evokes a different response from what<br />

was intended from the question.<br />

Emotional loading “What is your opinion on the tax mess?” vs.<br />

“what is your opinion on the tax issue”<br />

Attaching a famous “What do you think of Julia Gillard’s carbon tax?” vs.<br />

person’s name “What do you think of carbon tax?”<br />

Providing only one<br />

side or direction can<br />

“Do you think it is a good idea <strong>for</strong> your wife to do night<br />

study?”<br />

lead to loading “Do you think it is a good or bad idea <strong>for</strong> your wife to do<br />

night study?”<br />

Suggesting one<br />

among many<br />

possible specific<br />

answers<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

“How do you feel about your wife doing night study?”<br />

“Did you come to UNSW because of X?”<br />

“What features of UNSW attracted you be<strong>for</strong>e you came<br />

here?”<br />

Hidden argument “Do you feel that it is right <strong>for</strong> you to work over the<br />

university break to pay back your parents <strong>for</strong> all they have<br />

assisted you with?” – suppresses doubts, fears, worries<br />

“How do you feel about working over the summer break?” –<br />

tries to draw out worries, fears, doubts, etc<br />

Communication Styles<br />

In the case of an interview, which often is between strangers, there can be a mismatch between the<br />

communication style of the interviewer and the respondent. The communication style needs to be<br />

considered so that clear understanding occurs between both parties. The interviewer often needs to<br />

adjust the complexity of their language, their vocabulary, and their use of jargon, to build rapport and<br />

trust.<br />

Language Complexity<br />

If you are <strong>interviewing</strong> a layperson, it is better to use a simple level of language, and avoid technical<br />

jargon and confusion (e.g., ‘Commanding officer’, instead of CO). Conversely, in a specialised<br />

population, it is better to use their terminology to gain rapport and show understanding (mirroring).

Vocabulary<br />

Consideration of vocabulary is also important <strong>for</strong> building rapport and obtaining the desired<br />

in<strong>for</strong>mation. The vocabulary should be chosen to maximise the respondent’s likelihood of engaging.<br />

In some cases, the interviewer might adopt the language of an “insider”, but in other contexts, the<br />

interviewer might choose to retain the persona of an “outsider”<br />

Insider - A prostitute may feel more com<strong>for</strong>table discussing topic of “the spread of STIs” with an<br />

insider. There<strong>for</strong>e, adopt insider language - ‘working girls’ rather than ‘prostitute’.<br />

Outsider – A doctor-patient relationship. Using technical language then explaining what it means<br />

more simply, may shows credibility. Don’t use technical language to look smart.<br />

Avoid or be cautious using:<br />

Idioms, similes, metaphors, jokes, euphemisms, colloquialisms (cultural sensitivity)<br />

NEVER assume a shared understanding of a term – clarify to ensure your meanings are aligned.<br />

Building Rapport<br />

Rapport is a term used to describe, the relationship of two or more people who feel similar and/or<br />

relate well to each other. Rapport is important because it creates trust, which leads to a more open<br />

and honest discussion.<br />

Methods of building rapport<br />

Commonality The technique of deliberately finding something in common with a<br />

person or a customer in order to build a sense of camaraderie and<br />

trust. This is done through shared interests, dislikes, and situations<br />

(i.e., small talk).<br />

Emotional<br />

Mirroring<br />

Posture<br />

mirroring<br />

Tone and<br />

Tempo<br />

Mirroring<br />

Nonjudgemental<br />

attitude<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Empathizing with someone's emotional state by being on 'their side'.<br />

It involves listening <strong>for</strong> key words, and then using similar valence<br />

words to show you understand what they have said.<br />

Both too little and too much emotional expression by the interviewer<br />

results in less disclosure by the respondent<br />

Matching the tone of a person's body language through mirroring the<br />

general message of their posture and energy. (do NOT use direct<br />

imitation, as this can appear as mockery)<br />

Matching the tone, tempo, inflection, and volume of a person's voice.<br />

The respondent will not open up if they feel as they are being judged<br />

Inviting<br />

behaviour<br />

<br />

If anxious, make them feel invited by inviting gestures/body<br />

language. If they are intrusive into your personal space, you can use<br />

more control e.g., “why don’t you sit over there? That way we can talk<br />

more com<strong>for</strong>tably?”

Non-Verbal Cues<br />

Be aware of an individual’s non-verbal cues to detect their mood at the beginning. Things to look out<br />

<strong>for</strong> include:<br />

Territorial – avoid shaking hands, seat by the door, invading your space<br />

Behavioural – eye contact, fiddling with pencils, relaxed<br />

Emotional (expressive) – posture, gestures, facial expression, eye contact, tone of voice<br />

Maximising Empathy<br />

Empathy can be shown by verbal and non-verbal communication. One popular approach is to use a<br />

contextual statement to show you understand e.g., “I know some of the questions I ask may be<br />

difficult <strong>for</strong> you to answer in detail…Just take your time”. However, be careful saying that you<br />

‘understand’ the respondent’s predicament, as it could lead to a negative reaction, as can be seen by<br />

this dialogue between an oncology patient (CP) and a researcher (R).<br />

CP: “…I constantly feel awful from the chemotherapy”<br />

R: “I understand”<br />

CP: “Have you ever had chemotherapy?”<br />

R: “No”<br />

CP: “Then you don’t understand!”<br />

Active Listening<br />

Active listening is a communication technique that requires the listener to understand, interpret, and<br />

evaluate what they hear. When interacting, people often are not listening attentively. They may be<br />

distracted, thinking about other things, or thinking about what they are going to say next. Active<br />

listening is a structured way of listening and responding to others, focusing attention on the speaker.<br />

Suspending one's own frame of reference, suspending judgment and avoiding other internal mental<br />

activities are important to fully attend to the speaker.<br />

Levels of listening<br />

Level 1. Non-listening<br />

Level 2. Passive listening<br />

(conversational)<br />

Level 3. Active listening<br />

“It looks like I’m listening, I’m not really… I’m<br />

somewhere else in my mind.”<br />

I can hear what you’re saying, but I’m not engaging with<br />

what you are saying. I am waiting to say my bit.”<br />

“I’m fully engaged in what you are saying (verbally and<br />

non-verbally), and am attempting to see things from<br />

your point of view.”<br />

Think about situations in which you listen in each of these ways.

Reflecting, Paraphrasing, Clarifying, Summarising<br />

Reflecting<br />

Paraphrasing<br />

Summarising<br />

A verbal response to the respondent’s emotion<br />

Respondent: “So many things are going on right now: another hectic<br />

semester has started, my dog’s sick, and my mum’s ill too. I find myself<br />

running around trying to take care of everything. I’m not sure I can take it<br />

anymore.”<br />

Interviewer: “You’re feeling pretty overwhelmed by all the things that are<br />

going on right now.”<br />

Helps respondents:<br />

Feel understood<br />

Express more feelings<br />

Manage feelings<br />

Discriminate among various feelings<br />

To paraphrase, the interviewer chooses the most important details of<br />

what the client has just said and reflects them back to the client in the<br />

interviewer’s own words. Paraphrases can be just a few words or one or<br />

two brief sentences.<br />

Helps respondents:<br />

To convey that you are understanding him/her<br />

Help the respondent by simplifying, focusing and crystallizing what<br />

they said<br />

May encourage the client to elaborate<br />

Provide a check on the accuracy of your perceptions<br />

Summaries are brief statements of longer excerpts from the interview. In<br />

summarising, the interviewer attends to verbal and non-verbal comments<br />

from the client over a period of time, and then pulls together key parts of<br />

the extended communication, restating them <strong>for</strong> the client as accurately as<br />

possible.<br />

A collection of two or more paraphrases or reflections that condenses the<br />

client’s messages or the session<br />

To tie together multiple elements of client messages<br />

To identify a common theme or pattern<br />

To interrupt excessive rambling<br />

To start a session<br />

To end a session<br />

To pace a session<br />

To review progress<br />

To serve as a transition when changing topics<br />

Factors that affect active listening<br />

<br />

<br />

Focus is not on client (distracted, lose attention, interrupt, shift attention to oneself)<br />

Emotional responses (criticise the client, share personal opinion)<br />

o One needs to be non-judgemental and minimise personal biases. It is good to think about<br />

one’s prejudices, and be mentally prepared <strong>for</strong> an interview.

Active listening checklist<br />

‣ Use inviting body language<br />

‣ Do not appear distracted/detached during the consultation<br />

‣ Don’t be rushed, give respondent time and space to talk, allow silence<br />

‣ Encourage clarification<br />

‣ Summarise, paraphrase, reflect<br />

‣ Express understanding non-verbally (nodding, smiling, sympathising eye contact)<br />

‣ Acknowledge emotions of respondent<br />

NB Admitting when you don’t understand i.e., “I don’t understand” shows you are listening<br />

References<br />

Gordon, R. L. (1992). Basic <strong>interviewing</strong> <strong>skills</strong>. USA: F. E. Peacock Publishers Inc.<br />

Keats, D. M. (2000). Interviewing: A practical guide <strong>for</strong> <strong>students</strong> and professionals. Sydney: UNSW Press.<br />

McDaniel, M. A., Whetzel, D. L., Schmidt, F. L., & Maurer, S. D. (1994). The validity of<br />

employment Interviews: A comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology,<br />

79, 599-616.<br />

Stewart, C. J., & Cash, W. B. (1974). Interviewing: Principles and practices. Dubuque, Iowa: WCB<br />

Publishers.<br />

Yeo, A. (1993). Counselling: A problem solving approach. Singapore: Armour Publishing.<br />

Footnotes<br />

1. Gordon, R. L. (1992). Basic <strong>interviewing</strong> <strong>skills</strong>. USA: F. E. Peacock Publishers Inc. Quote page 9.

Interviewing Tutorial Slides

Interviewing Tutorial Scenarios<br />

Interview <strong>for</strong> Vacation Research Scholarship in School of Psychology<br />

• Interviewer: You will be conducting an interview to determine the suitability of a candidate (a thirdyear<br />

student) <strong>for</strong> a Vacation Research Scholarship in the School of Psychology. You should determine<br />

what evidence your candidate has <strong>for</strong> their experience and ability in relevant areas, such as<br />

Research, and their ability to work both independently and as a member of a team.<br />

• Interviewee 1: You have applied <strong>for</strong> a Vacation Research Scholarship in the School of Psychology.<br />

You will need to provide evidence of your experience and ability in relevant areas, such as Research,<br />

and your ability to work both independently and as a member of a team.<br />

• Interviewee 2: You have applied <strong>for</strong> a Vacation Research Scholarship in the School of Psychology.<br />

You will need to provide evidence of your experience and ability in relevant areas, such as Research,<br />

and your ability to work both independently and as a member of a team. However, given you are not<br />

confident that you are the best candidate <strong>for</strong> this position, you will try to take the interviewer off<br />

track to talk about things more of interest to yourself.<br />

University interview to determine suitability of student going on exchange<br />

• Interviewer: You will be conducting an interview to determine the suitability of a candidate (a thirdyear<br />

student) to go on an overseas exchange <strong>for</strong> a semester, to a country they have never visited.<br />

You should determine whether the candidate is suitable <strong>for</strong> the challenges of living away from<br />

home, and in a <strong>for</strong>eign country, by establishing what experiences they have had that will assist them<br />

in this. You will also need to determine whether they are a sufficiently strong student to cope with<br />

missing certain courses in their degree.<br />

• Interviewee 1: You have applied to go on an overseas exchange <strong>for</strong> a semester, to a country you<br />

have never visited. You should provide evidence of your suitability <strong>for</strong> the challenges of living away<br />

from home, and in a <strong>for</strong>eign country, by establishing what experiences you have had that will assist<br />

you in this. You will also need to prove that you are a sufficiently strong student to cope with missing<br />

certain courses in your degree.<br />

• Interviewee 2: You have applied to go on an overseas exchange <strong>for</strong> a semester, to a country you<br />

have never visited. You should provide evidence of your suitability <strong>for</strong> the challenges of living away<br />

from home, and in a <strong>for</strong>eign country, by establishing what experiences you have had that will assist<br />

you in this. You will also need to prove that you are a sufficiently strong student to cope with missing<br />

certain courses in your degree. However, given you are not confident that you are the best applicant<br />

<strong>for</strong> exchange, you will try to take the interviewer off track to talk about things which will make you<br />

look good.<br />

Career counselling – student concerned about which career direction to pursue<br />

• Interviewer: You will be conducting an interview to assist a third-year student to decide what career<br />

path to take. You should determine what career is most suitable, by establishing their strengths,<br />

their interests, their goals, and their experiences.<br />

• Interviewee 1: You will be interviewed to assist you to decide what career path to take. You will<br />

need to provide in<strong>for</strong>mation to the interviewer about your strengths, your interests, your goals, and<br />

your experiences.<br />

• Interviewee 2: You will be interviewed to assist you to decide what career path to take. You will<br />

need to provide in<strong>for</strong>mation to the interviewer about your strengths, your interests, your goals, and<br />

your experiences. You are only here because your parents have <strong>for</strong>ced you to attend, and would<br />

prefer to distract the interviewer to discuss things of interest to you, rather than answer their<br />

questions.

Job interview <strong>for</strong> Student Crisis Line Phone counselling team leader<br />

• Interviewer: You will be conducting an interview to determine the suitability of a candidate (a thirdyear<br />

student) <strong>for</strong> a Student Crisis Line Phone Counselling Team Leader. You should determine what<br />

evidence your candidate has <strong>for</strong> their experience and ability in relevant areas, such as Crisis<br />

Counselling, and their ability to work both collaboratively and as a leader of a team.<br />

• Interviewee 1: You have applied <strong>for</strong> the position of a Student Crisis Line Phone Counselling Team<br />

Leader. You will need to provide evidence of your experience and ability in relevant areas, such as<br />

Crisis Counselling, and your ability to work both collaboratively and as a leader of a team.<br />

• Interviewee 2: You have applied <strong>for</strong> the position of a Student Crisis Line Phone Counselling Team<br />

Leader. You will need to provide evidence of your experience and ability in relevant areas, such as<br />

Crisis Counselling, and your ability to work both collaboratively and as a leader of a team. However,<br />

you have only applied <strong>for</strong> this job to keep a friend company, so would prefer to distract the<br />

interviewer to discuss things of interest to you, rather than answer their questions.<br />

Research interview with a university student to determine what factors drive how they study <strong>for</strong> exams (<strong>for</strong><br />

a research project).<br />

• Interviewer: You will be conducting a research interview to determine what study strategies are<br />

used most by third-year <strong>students</strong>. You should determine what strategies the participant has<br />

employed during his/her university career, and how effective they have been in different contexts.<br />

• Interviewee 1: You will be interviewed to determine what study strategies you use. You will need to<br />

provide in<strong>for</strong>mation about the strategies you have employed during your university career, and how<br />

effective they have been in different contexts.<br />

• Interviewee 2: You will be interviewed to determine what study strategies you use. You will need to<br />

provide in<strong>for</strong>mation about the strategies you have employed during your university career, and how<br />

effective they have been in different contexts. However, you have not been a particularly effective<br />

student, so would prefer to distract the interviewer to discuss things of interest to you, rather than<br />

answer their questions.<br />

Clinical intake interview <strong>for</strong> quit gambling program<br />

• Interviewer: You will be conducting an interview to determine the suitability of a client (a third-year<br />

student) <strong>for</strong> a Quit Gambling program. You should determine the nature of the client’s gambling<br />

problem, including type of gambling, severity, frequency, triggers etc.<br />

• Interviewee 1: You have applied <strong>for</strong> a Quit Gambling program. You need to provide sufficient detail<br />

about the nature of your gambling problem, including type of gambling, severity, frequency, triggers<br />

etc.<br />

• Interviewee 2: You have applied <strong>for</strong> a Quit Gambling program. You need to provide sufficient detail<br />

about the nature of your gambling problem, including type of gambling, severity, frequency, triggers<br />

etc. You are not sure whether you really want to commit to this program, so would prefer to distract<br />

the interviewer to discuss things of interest to you, rather than answer their questions.

PSYC3011 2012<br />

Group Exercise 1: Contemporary Figures in Psychology<br />

Instructions: Please submit to your tutor in Week 6 tutorials. Ensure tutorial time, group name, and all group<br />

members’ full names and student numbers are included on your written response.<br />

Background: Four fundamental components of this course are Collaborative Learning, Communication Skills, Critical<br />

Thinking, and Research Methods. The first group work exercise requires you to work as a group to develop a Wikipedia<br />

entry <strong>for</strong> one academic in the School of Psychology at UNSW – your Contemporary Figure in Psychology. You will be<br />

required to interview your Contemporary Figure in Psychology (some time AFTER your Week 4 tutorial) to understand<br />

how they ended up in the area of research in which they are renowned, and the historical figures whose approaches<br />

have been most influential in your target’s research.<br />

The key criteria <strong>for</strong> success on this task include the ability to extract in<strong>for</strong>mation from both primary and secondary<br />

sources; to determine which in<strong>for</strong>mation is most relevant; to communicate that in<strong>for</strong>mation in an articulate and logical<br />

manner in both written and oral <strong>for</strong>ms; and to work collaboratively. You will find useful in<strong>for</strong>mation on working as a<br />

group on Blackboard.<br />

Tasks: You will need to address each of the following questions. Each group should submit one written response (500-<br />

1000 words), <strong>for</strong>matted as a Wikipedia entry, which will be posted on the Blackboard Wikipedia Discussion <strong>for</strong>um; AND<br />

do one brief (5 minute) tutorial presentation. Both of these components should represent the group consensus, and all<br />

group members will receive the same mark <strong>for</strong> this assignment.<br />

Your response should address the following:<br />

1) Identify your Contemporary Figure in Psychology (assigned in class), and arrange to interview them (preferably<br />

in person, however email or phone interviews may be necessary in some cases). Through <strong>interviewing</strong> this<br />

person, you should provide a brief biography including:<br />

a. Education – where, relevant teachers, philosophical approach of the School of Psychology/University<br />

attended<br />

b. Early research history – supervisors, collaborators<br />

c. Current research areas – give an example of a study that they are currently undertaking<br />

2) Identify the (historical) theoretical and empirical origins of the work of your Contemporary Figure in<br />

Psychology:<br />

a. To which renowned (historical) figure(s) can their current approach be traced back – you should<br />

provide a BRIEF overview of this person(s).<br />

b. Who are any relevant intermediaries in this pathway.<br />

c. Who are other researchers/scholars who your Figure consider to be important influences on their<br />

career/research path.<br />

Your goal is to determine how their career-related life experiences have shaped their ideas, and to try to develop a<br />

type of “family tree” of research in the relevant area.<br />

You will be asked to submit these components in 2 separate <strong>for</strong>ms, in Week 6:<br />

1) A WRITTEN response, in the <strong>for</strong>m of a Wikipedia entry. Please see the “Welcome to Wikipedia” guide on<br />

Blackboard <strong>for</strong> guidelines on how to write this. Please note that you WILL NOT be expected to actually post it<br />

on Wikipedia, we would just like you to use a contemporary <strong>for</strong>mat to communicate your ideas. You WILL be<br />

asked to email it to xxx by the time of your tutorial in Week 6. (3<br />

marks)<br />

2) An ORAL presentation in Week 6 tutorials. This should take no more than 5 minutes. One or more group<br />

members should participate in the presentation of your Contemporary Figure in Psychology to the class, in an<br />

engaging and relevant way. You may use PowerPoint slides or other materials in your talk. Groups who simply<br />

read out their Wikipedia entry will be receive minimal marks, as this component is intended to provide an<br />

alternative means of communicating your Figure’s story.<br />

(5 marks)<br />

Note: Plagiarism is a serious offence. Please ensure that this is entirely your own group’s work. See Course Handout<br />

page 10, see also Wikipedia’s Five pillars (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Five_pillars).

PSYC3011 2012<br />

Group Exercise 1: Contemporary Figures in Psychology<br />

Written Wikipedia Tutor Assessment<br />

Tutor’s Name:<br />

Team Name & Members:<br />

Tutorial Time:<br />

A score of 0 indicates that the written work did not meet criteria at all<br />

Half marks indicate that the written work just met the criteria<br />

A perfect score indicates that the written work fully met the criteria.<br />

Content/Process: criteria<br />

1. CFP’s Current Context<br />

Education<br />

Early research history<br />

Current research areas<br />

2. CFP’s Historical Origins:<br />

To which renowned (historical) figure(s) can their<br />

current approach be traced back<br />

Relevant intermediaries<br />

Other important influences<br />

3. Clarity:<br />

How well written & well organised was it?<br />

Overall, how in<strong>for</strong>mative was it?<br />

Comments and rating<br />

/1<br />

/1<br />

/1<br />

What was done well? SUBTOTAL: /3<br />

Suggestions <strong>for</strong> Improvement:<br />

Other Comments:

Tutor’s Name:<br />

Team Name & Members:<br />

PSYC3011 2012<br />

Group Exercise 1: Contemporary Figures in Psychology<br />

Oral Presentation Tutor Assessment (Adapted from UNSW Learning Centre <strong>for</strong>m)<br />

Tutorial Time:<br />

A score of 0 indicates that the presenters did not meet criteria at all<br />

Half marks indicate that the presenter just met the criteria<br />

A perfect score indicates that the presenter fully met the criteria.<br />

Content/Process: criteria<br />

Comments and rating<br />

1. CFP’s Current Context<br />

Education<br />

Early research history<br />

Current research areas<br />

/1<br />

(does NOT have to cover all points)<br />

2. CFP’s Historical Origins:<br />

To which renowned (historical) figure(s) can their<br />

current approach be traced back<br />

Relevant intermediaries<br />

Other important influences<br />

(does NOT have to cover all, but need to convey sense<br />

of how CFP got where they are historically research<br />

speaking) /1<br />

4. Per<strong>for</strong>mance<br />

Made appropriate eye contact.<br />

Awareness of body language.<br />

Presentation audible; presenter clearly seen by<br />

everyone. Pauses and silences used effectively.<br />

/1<br />

Verbally fluent.<br />

5. Materials<br />

Material clearly organised, appropriate.<br />

Audiovisual aids/handouts used where appropriate.<br />

Presentation interesting.<br />

Clear evidence of adequate preparation.<br />

Keeps within time constraints.<br />

/1<br />

How coordinated were the presenters?<br />

6. OVERALL,<br />

How effective was this presentation?<br />

Did it differ appropriately from the written<br />

submission? /1<br />

What did they do well? SUBTOTAL: /5<br />

Suggestions <strong>for</strong> Improvement:<br />

Other Comments:<br />

TOTAL: /8