A Process Model of Organizational Change in Cultural Context (OC3 ...

A Process Model of Organizational Change in Cultural Context (OC3 ...

A Process Model of Organizational Change in Cultural Context (OC3 ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

A <strong>Process</strong> <strong>Model</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Organizational</strong> <strong>Change</strong> <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>Cultural</strong> <strong>Context</strong> (OC 3 <strong>Model</strong>)<br />

The Impact <strong>of</strong> <strong>Organizational</strong> Culture on Lead<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Change</strong><br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> Leadership &<br />

<strong>Organizational</strong> Studies<br />

Volume 16 Number 1<br />

August 2009 19-37<br />

© 2009 Baker College<br />

10.1177/1548051809334197<br />

http://jlos.sagepub.com<br />

hosted at<br />

http://onl<strong>in</strong>e.sagepub.com<br />

Gail F. Latta<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Nebraska–L<strong>in</strong>coln<br />

<strong>Change</strong> resides at the heart <strong>of</strong> leadership. <strong>Organizational</strong> culture is one <strong>of</strong> many situational variables that have<br />

emerged as pivotal <strong>in</strong> determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the success <strong>of</strong> leaders’ efforts to implement change <strong>in</strong>itiatives. This article <strong>in</strong>troduces<br />

a process model <strong>of</strong> organizational change <strong>in</strong> cultural context (OC 3 <strong>Model</strong>) derived from ethnographic analysis.<br />

The model del<strong>in</strong>eates the differential impact <strong>of</strong> organizational culture at every stage <strong>of</strong> change implementation. Eight<br />

stages <strong>of</strong> cultural <strong>in</strong>fluence are identified and illustrated. Research propositions are stated to encourage ref<strong>in</strong>ement <strong>of</strong><br />

the model. Theoretical and practical implications for leadership are explored; applications for resolv<strong>in</strong>g organizational<br />

immunity to change are discussed.<br />

Keywords: organizational culture; organizational change; leadership theory; sensemak<strong>in</strong>g; process model;<br />

ethnography;<br />

Purpose and Research Questions<br />

The primary objective <strong>of</strong> this study was to model<br />

the <strong>in</strong>teraction between organizational culture and<br />

change, del<strong>in</strong>eat<strong>in</strong>g the ways <strong>in</strong> which a leader’s<br />

knowledge <strong>of</strong> organizational culture affects the process<br />

<strong>of</strong> implement<strong>in</strong>g change, and identify<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

stages <strong>of</strong> the change process at which the <strong>in</strong>teraction<br />

between organizational culture and change implementation<br />

holds functional significance. Many exist<strong>in</strong>g<br />

models <strong>of</strong> organizational change acknowledge the<br />

<strong>in</strong>fluence <strong>of</strong> tacit dimensions <strong>of</strong> organizational life at<br />

one or more stages <strong>of</strong> the change process (Bate, Khan,<br />

& Pye, 2000; Burke, 2008; Demers, 2007; Wilk<strong>in</strong>s &<br />

Dyer, 1988). These models reflect differ<strong>in</strong>g levels <strong>of</strong><br />

granularity with respect to the process <strong>of</strong> effect<strong>in</strong>g<br />

organizational change, and each recognizes dist<strong>in</strong>ctive<br />

stages <strong>of</strong> change implementation (By, 2005). The<br />

<strong>Model</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Organizational</strong> <strong>Change</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Cultural</strong> <strong>Context</strong><br />

(OC 3 <strong>Model</strong>) <strong>in</strong>troduced <strong>in</strong> this article was developed<br />

to reflect critical stages <strong>in</strong> the process <strong>of</strong> change<br />

implementation where organizational culture exerts<br />

differential <strong>in</strong>fluence.<br />

The OC 3 <strong>Model</strong> was derived from an ethnographic<br />

study undertaken to <strong>in</strong>vestigate how organizational<br />

culture shapes the development and mediates the<br />

implementation and impact <strong>of</strong> change <strong>in</strong>itiatives<br />

<strong>in</strong>troduced by newly appo<strong>in</strong>ted leaders recruited from<br />

outside large, complex organizations. Research questions<br />

focused on (a) how knowledge <strong>of</strong> organizational<br />

culture is acquired by newly appo<strong>in</strong>ted leaders,<br />

(b) how cultural knowledge affects the process <strong>of</strong><br />

change implementation, and (c) how tacit elements <strong>of</strong><br />

organizational culture <strong>in</strong>fluence efforts to effect<br />

change. This article presents theoretical propositions<br />

<strong>of</strong> the OC 3 <strong>Model</strong>, position<strong>in</strong>g it with<strong>in</strong> the context <strong>of</strong><br />

exist<strong>in</strong>g conceptual and process models <strong>of</strong> organizational<br />

change and establish<strong>in</strong>g an agenda for future<br />

research. Implications for leadership and organizational<br />

studies are explored.<br />

<strong>Model</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>Organizational</strong> <strong>Change</strong><br />

Leadership scholars have studied organizational<br />

change from both conceptual and process perspectives.<br />

Conceptual approaches focus on the antecedents and<br />

consequences <strong>of</strong> change (the “what”); process views<br />

address roles and strategies required for implementation<br />

(the “how”) (Burke, 2008, p. 154, emphasis <strong>in</strong> orig<strong>in</strong>al).<br />

Conceptual <strong>Model</strong>s<br />

Conceptual models <strong>of</strong> change concentrate on the<br />

content and magnitude <strong>of</strong> strategic <strong>in</strong>itiatives, with<br />

19

20 Journal <strong>of</strong> Leadership & <strong>Organizational</strong> Studies<br />

particular emphasis on the cognitive mechanisms<br />

implicated <strong>in</strong> effect<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>tended outcomes.<br />

Golembiewski, Bill<strong>in</strong>gsley, and Yeager (1976) conceptualized<br />

three levels <strong>of</strong> change—alpha, beta and<br />

gamma—based on the degree to which <strong>in</strong>dividuals<br />

are required to modify their underly<strong>in</strong>g cognitive<br />

mechanisms for assess<strong>in</strong>g the behavioral outcomes <strong>of</strong><br />

change <strong>in</strong>itiatives. Other conceptual models <strong>of</strong> change<br />

emphasize the mental constructs that mediate sensemak<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong> organizations. These content theories <strong>of</strong><br />

change <strong>in</strong>voke the notion <strong>of</strong> schemata (Bartunek &<br />

Moch, 1987) or theories-<strong>in</strong>-use (Argyris, 1976) as<br />

mental constructs function<strong>in</strong>g to focus attention,<br />

<strong>in</strong>terpret experience, and assign mean<strong>in</strong>g to events. In<br />

the context <strong>of</strong> organizational culture, these conceptual<br />

models <strong>of</strong> change draw attention to the importance <strong>of</strong><br />

consider<strong>in</strong>g the extent to which a change agenda<br />

requires new strategies <strong>of</strong> sensemak<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Bartunek and Moch’s (1987) first, second, and<br />

third orders <strong>of</strong> change require <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g levels <strong>of</strong><br />

exam<strong>in</strong>ation with respect to tacit assumptions <strong>of</strong><br />

mean<strong>in</strong>g and decision mak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> organizational sett<strong>in</strong>gs.<br />

The ability to surface and hold as object the<br />

underly<strong>in</strong>g assumptions embedded <strong>in</strong> organizational<br />

culture is particularly important <strong>in</strong> third-order change,<br />

which requires the dynamic consideration <strong>of</strong> alternative<br />

systems <strong>of</strong> mean<strong>in</strong>g, not just the substitution <strong>of</strong> a<br />

new perspective for an old one, as is sufficient for<br />

second-order change. Content models <strong>of</strong> change draw<br />

attention to the need for leaders to take <strong>in</strong>to consideration<br />

the mental demands <strong>of</strong> affect<strong>in</strong>g shifts <strong>in</strong> shared<br />

sensemak<strong>in</strong>g embedded <strong>in</strong> organizational culture<br />

when chart<strong>in</strong>g a course for change because the ability<br />

to conceive and consider alternative perspectives is<br />

understood only at high levels <strong>of</strong> psychosocial development<br />

(Kegan, 1994).<br />

<strong>Process</strong> <strong>Model</strong>s<br />

<strong>Process</strong> models <strong>of</strong> change designate the sequence<br />

<strong>of</strong> events necessary to effect organizational change,<br />

focus<strong>in</strong>g more on the essential steps <strong>of</strong> implementation<br />

than on the conceptual tasks required. All process<br />

models bear homage to Lew<strong>in</strong>’s (1947) classic threestage<br />

model <strong>of</strong> change, denot<strong>in</strong>g the essential progression<br />

through phases <strong>of</strong> unfreeze, change, and<br />

refreeze. Subsequent process models outl<strong>in</strong>e sequences<br />

<strong>of</strong> events that elaborate to vary<strong>in</strong>g degrees upon these<br />

essential underly<strong>in</strong>g stages <strong>of</strong> change (Bate et al.,<br />

2000; By, 2005; Kotter, 1996; Luecke, 2003; M<strong>in</strong>tzberg<br />

& Westley, 1992; Reardon, Reardon, & Rowe, 1998).<br />

In his recent reprisal, Burke (2008) emphasized the<br />

role <strong>of</strong> leadership at each stage, add<strong>in</strong>g a prelaunch<br />

phase focused on prepar<strong>in</strong>g an organization for the<br />

disruptive effects <strong>of</strong> change.<br />

<strong>Process</strong> models <strong>of</strong> change have been categorized<br />

with respect to the underly<strong>in</strong>g philosophical perspectives<br />

and def<strong>in</strong>itions they embody, major underly<strong>in</strong>g<br />

assumptions, and types <strong>of</strong> sensemak<strong>in</strong>g that characterize<br />

each approach (de Caluwé; & Vermaak, 2003;<br />

Kezar, 2001; Van de Ven & Poole, 1995). Although<br />

the number <strong>of</strong> categories and labels <strong>in</strong> each classification<br />

scheme varies, five dist<strong>in</strong>ct process models have<br />

been dist<strong>in</strong>guished: evolutionary (<strong>in</strong>evitable), teleological<br />

(planned), life cycle (maturational), political<br />

(strategic), and social cognitive (conceptual).<br />

<strong>Organizational</strong> culture is afforded differ<strong>in</strong>g roles and<br />

functional significance <strong>in</strong> each <strong>of</strong> these process models<br />

<strong>of</strong> change. Kezar (2001) reserved a sixth category<br />

<strong>of</strong> cultural change for process models specifically<br />

aimed at alter<strong>in</strong>g organizational culture. <strong>Process</strong> models<br />

<strong>of</strong> cultural change are now recognized by organizational<br />

theorists despite the fact that “the concept <strong>of</strong><br />

culture was orig<strong>in</strong>ally developed to expla<strong>in</strong> permanence,<br />

not change” (Demers, 2007, p. 80).<br />

<strong>Organizational</strong> Culture <strong>in</strong> <strong>Model</strong>s <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Organizational</strong> <strong>Change</strong><br />

<strong>Organizational</strong> culture has consistently emerged as<br />

a pivotal variable <strong>in</strong> determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the success <strong>of</strong> efforts<br />

to implement <strong>in</strong>stitutional change (Bate et al., 2000;<br />

Curry, 1992; Hercleuous, 2001; Wilk<strong>in</strong>s & Dyer,<br />

1988). Both conceptual and process models <strong>of</strong> organizational<br />

change have been modified to reflect the role<br />

<strong>of</strong> cultural dynamics <strong>in</strong> moderat<strong>in</strong>g leaders’ efforts to<br />

<strong>in</strong>fluence the attitudes, norms, and behavior <strong>of</strong> followers<br />

<strong>in</strong> organizational sett<strong>in</strong>gs. The ways <strong>in</strong> which<br />

organizational culture has been <strong>in</strong>tegrated <strong>in</strong>to these<br />

models <strong>of</strong> change provides a context for understand<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the research questions addressed <strong>in</strong> this study.<br />

<strong>Organizational</strong> Culture <strong>in</strong><br />

Conceptual <strong>Model</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>Change</strong><br />

Conceptually, Gagliardi’s (1986) fan model <strong>of</strong> cultural<br />

change accounts for the differential effects <strong>of</strong><br />

apparent, <strong>in</strong>cremental, and revolutionary change on<br />

exist<strong>in</strong>g cultural tenets <strong>in</strong> organizations. <strong>Change</strong> <strong>in</strong>itiatives<br />

approached from each <strong>of</strong> these strategic perspectives<br />

serve respectively to re<strong>in</strong>force, extend, or<br />

essentially underm<strong>in</strong>e exist<strong>in</strong>g basic assumptions and<br />

values implicated by the change <strong>in</strong>itiatives. <strong>Cultural</strong>

Latta / <strong>Model</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Organizational</strong> <strong>Change</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Cultural</strong> <strong>Context</strong> (OC 3 <strong>Model</strong>) 21<br />

tenets lie at the heart <strong>of</strong> the strategies and modes <strong>of</strong><br />

implementation adopted for <strong>in</strong>troduc<strong>in</strong>g planned<br />

change, and they determ<strong>in</strong>e whether leaders can<br />

expect cultural assimilation, resistance, or modification<br />

as a result <strong>of</strong> their <strong>in</strong>fluence. Gagliardi’s (1986)<br />

model draws attention to the importance <strong>of</strong> leaders’<br />

consider<strong>in</strong>g the deeper cultural implications <strong>of</strong> the<br />

strategies they adopt for <strong>in</strong>troduc<strong>in</strong>g change <strong>in</strong>itiatives<br />

<strong>in</strong>to organizational sett<strong>in</strong>gs.<br />

Hatch’s (2006) cultural dynamics model provides<br />

another conceptual framework for consider<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

cognitive impact <strong>of</strong> organizational culture on change<br />

implementation. <strong>Change</strong> is conceived with<strong>in</strong> the cultural<br />

dynamics model as an ongo<strong>in</strong>g cycle <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>terpretation<br />

by which <strong>in</strong>dividuals cont<strong>in</strong>ually re<strong>in</strong>terpret<br />

events that enter the stream <strong>of</strong> cultural mean<strong>in</strong>g from<br />

all levels with<strong>in</strong> the organization: Four <strong>in</strong>terpretive<br />

acts mediate the <strong>in</strong>teractions among cultural elements,<br />

translat<strong>in</strong>g artifacts <strong>in</strong>to symbols, symbols <strong>in</strong>to basic<br />

assumptions, and basic assumptions <strong>in</strong>to values that<br />

are <strong>in</strong> turn realized as artifacts. The <strong>in</strong>terpretive acts<br />

that l<strong>in</strong>k these elements <strong>of</strong> culture are symbolization,<br />

implementation, manifestation, and realization,<br />

respectively (Hatch, 2000). Although the cultural<br />

dynamics model does not outl<strong>in</strong>e a sequential process<br />

<strong>of</strong> change implementation, it does <strong>of</strong>fer an explanation<br />

for many <strong>of</strong> the underly<strong>in</strong>g cognitive transformations<br />

at work with<strong>in</strong> the sensemak<strong>in</strong>g mechanisms<br />

implicated by efforts to implement organizational<br />

change.<br />

<strong>Organizational</strong> Culture <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>Process</strong> <strong>Model</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>Change</strong><br />

With respect to process models <strong>of</strong> change, organizational<br />

culture has been <strong>in</strong>corporated by theorists<br />

who recognize the importance <strong>of</strong> account<strong>in</strong>g for tacit<br />

dimensions <strong>of</strong> sensemak<strong>in</strong>g as moderat<strong>in</strong>g the impact<br />

<strong>of</strong> planned change. These models vary with respect to<br />

whether culture is identified as the target <strong>of</strong> the<br />

change <strong>in</strong>itiative or merely serves as a context for<br />

affect<strong>in</strong>g other strategic objectives.<br />

The Burke-Litw<strong>in</strong> model illustrates an approach<br />

adopted by many process theorists for <strong>in</strong>corporat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

organizational culture <strong>in</strong>to models <strong>of</strong> organizational<br />

change (Burke, 2008). <strong>Cultural</strong> factors function <strong>in</strong><br />

this model as one <strong>of</strong> four dimensions <strong>in</strong>fluenc<strong>in</strong>g<br />

leadership, with systemic l<strong>in</strong>ks to organizational performance,<br />

mission and strategy, and the external environment.<br />

With<strong>in</strong> this framework four phases are<br />

def<strong>in</strong>ed: prelaunch, launch, postlaunch, and susta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

the change. These phases encompass activities<br />

relat<strong>in</strong>g to leader self-exam<strong>in</strong>ation, establish<strong>in</strong>g and<br />

communicat<strong>in</strong>g need, clarify<strong>in</strong>g vision, deal<strong>in</strong>g with<br />

resistance, ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g consistency and persistence,<br />

deal<strong>in</strong>g with unanticipated consequences, susta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

momentum, and choos<strong>in</strong>g successors. <strong>Organizational</strong><br />

culture is conceptualized <strong>in</strong> this and other process<br />

models <strong>of</strong> change as one <strong>of</strong> many systemic factors<br />

affect<strong>in</strong>g the context <strong>in</strong> which change is <strong>in</strong>troduced.<br />

The preced<strong>in</strong>g review <strong>of</strong> content and process models<br />

<strong>of</strong> organizational change leaves open the question <strong>of</strong><br />

whether cultural dynamics <strong>in</strong>fluence the process <strong>of</strong><br />

effect<strong>in</strong>g organizational change <strong>in</strong> a uniform manner or<br />

have a differential impact at each stage <strong>of</strong> implementation.<br />

This study was conducted to address this empirical<br />

question. Results suggest that organizational culture<br />

<strong>in</strong>fluences the process <strong>of</strong> effect<strong>in</strong>g change differently at<br />

each stage <strong>of</strong> implementation. The OC 3 <strong>Model</strong> was<br />

developed to aid leaders, human resource pr<strong>of</strong>essionals,<br />

and other change agents <strong>in</strong> anticipat<strong>in</strong>g and<br />

account<strong>in</strong>g for the impact <strong>of</strong> organizational culture at<br />

every stage the change implementation process.<br />

Method<br />

The target <strong>in</strong>stitution <strong>in</strong> this qualitative study <strong>of</strong><br />

organizational change was a public research university<br />

ranked among the top 25 members <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Association <strong>of</strong> American Universities. Ethnographic<br />

data were collected over a 4-month residency dur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

which the researcher was granted unrestricted access<br />

to organizational leaders, adm<strong>in</strong>istrators, faculty, and<br />

students. Observations, <strong>in</strong>terviews, and reflexive<br />

hypothesis test<strong>in</strong>g served as the primary means <strong>of</strong><br />

data collection (Fetterman, 1998). One hundred <strong>in</strong>terviews<br />

were conducted with 86 <strong>in</strong>dividuals at all levels<br />

<strong>in</strong> the university, represent<strong>in</strong>g current and previous<br />

adm<strong>in</strong>istrators, academic middle managers, and faculty<br />

at every rank. Interviewees were systematically<br />

recruited from four upper adm<strong>in</strong>istrative units, six<br />

colleges, and 15 academic departments, represent<strong>in</strong>g<br />

a cross section <strong>of</strong> discipl<strong>in</strong>ary perspectives. Some<br />

<strong>in</strong>terviewees served as key <strong>in</strong>formants, provid<strong>in</strong>g<br />

opportunities for repeated <strong>in</strong>teraction throughout the<br />

4-month period. The overall response rate for <strong>in</strong>terview<br />

requests was 93%; one <strong>in</strong>terviewee decl<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

permission to be audiotaped.<br />

Interviews consisted <strong>of</strong> open-ended questions<br />

designed to elucidate <strong>in</strong>terviewees’ recollection and<br />

perspectives on critical <strong>in</strong>cidents <strong>in</strong>fluenc<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

implementation <strong>of</strong> change, dimensions <strong>of</strong> organizational<br />

culture, personal reflections, and emotional

22 Journal <strong>of</strong> Leadership & <strong>Organizational</strong> Studies<br />

reactions to campus events both historical and ongo<strong>in</strong>g<br />

as well as subjective assessments <strong>of</strong> the progress <strong>of</strong><br />

change implementation. Because the focus <strong>of</strong> analysis<br />

was on the implementation <strong>of</strong> change, one <strong>of</strong> the key<br />

<strong>in</strong>formants was the university provost, who had been<br />

recruited 5 years prior to the study to implement a strategic<br />

plan. The provost, together with the university<br />

president, functioned as the primary agents <strong>of</strong> change<br />

<strong>in</strong> this academic community. Periodic meet<strong>in</strong>gs permitted<br />

ongo<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>quiry regard<strong>in</strong>g the provost’s perspectives,<br />

thought processes, decision mak<strong>in</strong>g, actions, and<br />

reactions to campus events dur<strong>in</strong>g my residency.<br />

Strategic question<strong>in</strong>g permitted exploration <strong>of</strong> factors<br />

contribut<strong>in</strong>g to behavior and decision mak<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the extent to which cultural knowledge <strong>in</strong>fluenced<br />

processes <strong>of</strong> sensemak<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Trust was established with <strong>in</strong>terviewees and key<br />

<strong>in</strong>formants by pledg<strong>in</strong>g both personal and <strong>in</strong>stitutional<br />

confidentiality and by ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g researcher<br />

<strong>in</strong>dependence throughout the 4-month residency. Bias<br />

was m<strong>in</strong>imized by engag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> autonomous participation<br />

and observations <strong>of</strong> campus cultural dynamics,<br />

obta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g triangulated perspectives, protect<strong>in</strong>g data<br />

<strong>in</strong>tegrity, and conduct<strong>in</strong>g implicit hypothesis test<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

The tim<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>terviews, occurr<strong>in</strong>g toward the end<br />

<strong>of</strong> the 5-year implementation process, further m<strong>in</strong>imized<br />

the potential for researcher <strong>in</strong>fluence on the<br />

target <strong>in</strong>stitution, study participants, or the outcomes<br />

<strong>of</strong> change process.<br />

Analysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>Organizational</strong> Culture<br />

Approaches to <strong>Cultural</strong> Analysis<br />

Two approaches to cultural analysis have traditionally<br />

been embraced by scholars <strong>of</strong> organizational<br />

culture and change (Demers, 2007). The functionalist<br />

approach focuses on the role <strong>of</strong> cultural norms <strong>in</strong><br />

regulat<strong>in</strong>g behavior and susta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g organizational survival.<br />

From a functionalist perspective, “the emergence<br />

and existence <strong>of</strong> organizational culture is<br />

expla<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> the functions it performs to<br />

<strong>in</strong>ternal <strong>in</strong>tegration and external adaptation, rather<br />

than <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> its mean<strong>in</strong>g to the members <strong>of</strong> the<br />

organization” (Schultz, 1995, p. 23). A symbolic<br />

approach emphasizes the ways <strong>in</strong> which shared systems<br />

<strong>of</strong> mean<strong>in</strong>g are employed by members <strong>of</strong> an<br />

organization to <strong>in</strong>terpret events, make sense <strong>of</strong> reality,<br />

assign mean<strong>in</strong>g to experience, and create common<br />

understand<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> situations (Alvesson, 2002).<br />

A symbolic approach to cultural analysis was<br />

employed <strong>in</strong> this study because the primary objective<br />

was to illum<strong>in</strong>ate ways <strong>in</strong> which culturally embedded<br />

processes <strong>of</strong> sensemak<strong>in</strong>g moderated the implementation<br />

<strong>of</strong> organizational change. Understand<strong>in</strong>g organizational<br />

responses to change requires elicit<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

underly<strong>in</strong>g rules by which <strong>in</strong>dividuals use tacit knowledge<br />

<strong>in</strong> mak<strong>in</strong>g sense <strong>of</strong> events by impos<strong>in</strong>g mean<strong>in</strong>g<br />

on shared experiences. As a negotiated reality, culture<br />

provides a worthy metaphor for understand<strong>in</strong>g change<br />

(Alvesson, 2002). The symbolic approach reflects<br />

greater attention to the implicit processes <strong>of</strong> mean<strong>in</strong>g<br />

mak<strong>in</strong>g that shape decision mak<strong>in</strong>g and the underly<strong>in</strong>g<br />

processes <strong>of</strong> sensemak<strong>in</strong>g that moderate the<br />

behavior <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividuals <strong>in</strong> organizational sett<strong>in</strong>gs. A<br />

functionalist approach to document<strong>in</strong>g cultural artifacts<br />

and behavioral norms would not have elucidated<br />

the ways <strong>in</strong> which members <strong>of</strong> the organization draw<br />

on underly<strong>in</strong>g values and basic assumptions <strong>in</strong> ascrib<strong>in</strong>g<br />

mean<strong>in</strong>g to events related to the change agenda<br />

(Schultz, 1995).<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>il<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Organizational</strong> Culture<br />

The first procedural product <strong>of</strong> analysis <strong>in</strong> this<br />

study was a comprehensive ethnographic pr<strong>of</strong>ile <strong>of</strong><br />

the target <strong>in</strong>stitution’s systems <strong>of</strong> cultural mean<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Data analysis was <strong>in</strong>formed by Mart<strong>in</strong>’s (2002) multiple<br />

perspectives model <strong>of</strong> cultural analysis, which<br />

advocates simultaneous consideration <strong>of</strong> evidence for<br />

cultural <strong>in</strong>tegration, differentiation, and fragmentation<br />

with<strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>stitution. The <strong>in</strong>tegrationist perspective<br />

promotes construction <strong>of</strong> an overarch<strong>in</strong>g pr<strong>of</strong>ile<br />

<strong>of</strong> the organization’s dom<strong>in</strong>ant cultural tenets, and the<br />

differentiation perspective leads to <strong>in</strong>dividual subpr<strong>of</strong>iles<br />

<strong>of</strong> organizational units. The fragmentation perspective<br />

focuses on endur<strong>in</strong>g sources <strong>of</strong> ambiguity<br />

embedded <strong>in</strong> the culture <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>stitution.<br />

As employed <strong>in</strong> this study, the multiple perspectives<br />

analysis resulted <strong>in</strong> both a pr<strong>of</strong>ile <strong>of</strong> the dom<strong>in</strong>ant<br />

organizational culture and a comparative analysis,<br />

across organizational units, <strong>of</strong> the degree to which<br />

each subculture reflects dom<strong>in</strong>ant cultural tenets <strong>of</strong><br />

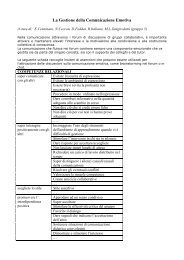

the organization (Figure 1).<br />

Document<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Organizational</strong> <strong>Change</strong><br />

The second procedural product <strong>of</strong> this study was<br />

the creation <strong>of</strong> a taxonomy <strong>of</strong> change strategies<br />

adopted at the target <strong>in</strong>stitution (Figure 1). Although<br />

the <strong>in</strong>itial focus <strong>of</strong> analysis was on planned change,<br />

the project expanded to encompass all types <strong>of</strong> change<br />

implemented at the target <strong>in</strong>stitution dur<strong>in</strong>g the period<br />

<strong>of</strong> study. This methodological shift resulted <strong>in</strong> a more<br />

comprehensive treatment <strong>of</strong> the impact <strong>of</strong> cultural

Latta / <strong>Model</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Organizational</strong> <strong>Change</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Cultural</strong> <strong>Context</strong> (OC 3 <strong>Model</strong>) 23<br />

Figure 1<br />

Interrelations Between Dom<strong>in</strong>ant <strong>Cultural</strong> Pr<strong>of</strong>ile and Taxonomy<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Change</strong> Initiatives at Target Institution<br />

Bi-directional Interaction: <strong>Organizational</strong> Culture and <strong>Change</strong><br />

Taxonomy <strong>of</strong> <strong>Change</strong> Initiatives<br />

Dom<strong>in</strong>ant <strong>Cultural</strong> Pr<strong>of</strong>ile<br />

Pervasive Paternalism<br />

• Employee Longevity<br />

• Dom<strong>in</strong>ance <strong>of</strong> Bus<strong>in</strong>ess Officers<br />

• Respect Adm<strong>in</strong>istrative Hierarchy<br />

• Advisory Role <strong>of</strong> Faculty Senate<br />

Culture <strong>of</strong> Prestige<br />

• Aversion to Public Debate<br />

• Sense <strong>of</strong> Industry<br />

• Institutional Loyalty<br />

• Intolerance <strong>of</strong> Non-conformity<br />

Applied Scholarship Identity<br />

• Balance Teach<strong>in</strong>g & Research<br />

• Dom<strong>in</strong>ance <strong>of</strong> Applied Discipl<strong>in</strong>es<br />

Decentralization <strong>of</strong> power<br />

• Unit-level Self-determ<strong>in</strong>ism<br />

• Respect College Subcultures<br />

• Differential Power among Colleges<br />

1. Determ<strong>in</strong>es Read<strong>in</strong>ess<br />

2. Shapes Vision<br />

3. Informs Initiatives<br />

4. Strategies Reflect<br />

5. Embodies Impact<br />

6.Mediates Implementation<br />

7.Moderates Outcomes<br />

8. Collateral Effects<br />

Reform Applied Scholarship Mission<br />

• Revitalize Eng<strong>in</strong>eer<strong>in</strong>g<br />

• Comb<strong>in</strong>e Outreach & Research<br />

Interdiscipl<strong>in</strong>ary Scholarship<br />

• Interdiscipl<strong>in</strong>ary Centers<br />

• Criteria for New Faculty<br />

Discovery Infrastructure<br />

• Build Applied Research Campus<br />

• Reform Office <strong>of</strong> Research<br />

Curriculum Reform<br />

• Interdiscipl<strong>in</strong>ary Curriculum<br />

• University-wide Honors Program<br />

Elevation <strong>of</strong> Teach<strong>in</strong>g<br />

• Hire 300 New Faculty<br />

• Relocate Teach<strong>in</strong>g Support Center<br />

Empower Deans<br />

• Budget Decentralization<br />

Fund<strong>in</strong>g Strategy<br />

• $1000 New Student Fee<br />

• Centralize Alumni Fund Rais<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Diversity<br />

• Emersion Workshops<br />

• Advisory Committee<br />

dynamics on all types <strong>of</strong> change. Analysis revealed<br />

change <strong>in</strong>itiatives conform<strong>in</strong>g to all six types <strong>of</strong> process<br />

models identified by Kezar (2001). Together<br />

with the differentiated cultural pr<strong>of</strong>ile, the taxonomy<br />

<strong>of</strong> change <strong>in</strong>itiatives provided a context for model<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the <strong>in</strong>teraction <strong>of</strong> cultural knowledge and organizational<br />

change, as presented <strong>in</strong> the rema<strong>in</strong>der <strong>of</strong> this<br />

article. Latta (2006) provided a comprehensive ethnographic<br />

presentation <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>terim products <strong>of</strong> analysis<br />

perta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g to cultural analysis and the taxonomy <strong>of</strong><br />

change <strong>in</strong>itiatives at the target <strong>in</strong>stitution.<br />

Develop<strong>in</strong>g a <strong>Model</strong><br />

For purpose <strong>of</strong> model<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>teraction between<br />

organizational culture and change, a generic process<br />

model <strong>of</strong> organizational change was employed, del<strong>in</strong>eat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

seven sequential stages: (a) assess<strong>in</strong>g read<strong>in</strong>ess for<br />

change, (b) creat<strong>in</strong>g a vision for change, (c) specify<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong>tervention <strong>in</strong>itiatives, (d) develop<strong>in</strong>g implementation<br />

strategies, (e) effect<strong>in</strong>g change, (f)<strong>in</strong>stitutionaliz<strong>in</strong>g<br />

change, and (g) assess<strong>in</strong>g the impact <strong>of</strong> change. The OC 3<br />

<strong>Model</strong> specifies both the mediat<strong>in</strong>g and moderat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong>fluence <strong>of</strong> organizational culture at each stage <strong>of</strong><br />

this generic change process. The basic elements <strong>of</strong> the<br />

OC 3 <strong>Model</strong> are presented graphically <strong>in</strong> Figure 2. The<br />

model functions as an overlay, <strong>in</strong>form<strong>in</strong>g exist<strong>in</strong>g<br />

process models <strong>of</strong> organizational change (de Caluwé;<br />

& Vermaak, 2003; Kezar, 2001; Van de Ven & Poole,<br />

1995), del<strong>in</strong>eat<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>terplay between organizational<br />

culture and the specific change <strong>in</strong>itiatives targeted<br />

by a leadership agenda.<br />

The dynamics <strong>of</strong> the OC 3 <strong>Model</strong> specify the bidirectional<br />

<strong>in</strong>fluence <strong>of</strong> culture on planned organizational<br />

change and the ways <strong>in</strong> which planned change<br />

<strong>in</strong>itiatives both alter and re<strong>in</strong>force <strong>in</strong>stitutional culture<br />

(see Figure 1). The multiple <strong>in</strong>teractions between<br />

<strong>in</strong>stitutional culture and the dynamic processes <strong>of</strong><br />

effect<strong>in</strong>g organizational change are detailed <strong>in</strong> the<br />

model at each stage <strong>of</strong> plann<strong>in</strong>g and implementation.<br />

The rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g sections <strong>of</strong> this article describe the<br />

components <strong>of</strong> the OC 3 <strong>Model</strong>, del<strong>in</strong>eat<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>teraction<br />

<strong>of</strong> organizational culture and change at each<br />

stage and illustrat<strong>in</strong>g the utility <strong>of</strong> cultural knowledge<br />

for <strong>in</strong>form<strong>in</strong>g the process <strong>of</strong> implement<strong>in</strong>g organizational<br />

change. Theoretical propositions are stated to

24 Journal <strong>of</strong> Leadership & <strong>Organizational</strong> Studies<br />

Figure 2<br />

<strong>Model</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Organizational</strong> <strong>Change</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Cultural</strong> <strong>Context</strong> (OC 3 <strong>Model</strong>)<br />

encourage future verification and ref<strong>in</strong>ement <strong>of</strong> the<br />

OC 3 <strong>Model</strong>. Implications for leadership are explored.<br />

OC 3 <strong>Model</strong><br />

<strong>Organizational</strong> culture, the central phenomenon <strong>in</strong><br />

this qualitative study, is situated at the core <strong>of</strong> the OC 3<br />

<strong>Model</strong>. This position<strong>in</strong>g reflects recognition <strong>of</strong> organizational<br />

culture as an embedded phenomenon that<br />

both exerts <strong>in</strong>fluence on and is <strong>in</strong>fluenced by other<br />

<strong>in</strong>stitutional processes. It further illustrates that the<br />

OC 3 <strong>Model</strong> is grounded <strong>in</strong> a systemic view <strong>of</strong> organizational<br />

change embody<strong>in</strong>g feedback loops l<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g<br />

cultural dynamics with the change process (Katz &<br />

Kahn, 1978). Eight stages <strong>of</strong> cultural <strong>in</strong>fluence are<br />

identified: cultural analysis <strong>of</strong> read<strong>in</strong>ess, shap<strong>in</strong>g<br />

vision, <strong>in</strong>form<strong>in</strong>g change <strong>in</strong>itiatives, reflect<strong>in</strong>g culture<br />

<strong>in</strong> implementation strategies, embody<strong>in</strong>g cultural<br />

<strong>in</strong>tent, cultural mediation <strong>of</strong> implementation, moderat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

outcomes <strong>of</strong> change, and document<strong>in</strong>g collateral<br />

effects (see Figure 2). The OC 3 <strong>Model</strong> del<strong>in</strong>eates the<br />

<strong>in</strong>fluence <strong>of</strong> organizational culture and a leader’s cultural<br />

knowledge at each <strong>of</strong> these stages. The follow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

discussion states the theoretical assumptions underly<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the model and clarifies the nature and direction <strong>of</strong><br />

cultural <strong>in</strong>fluence at each stage <strong>of</strong> organizational<br />

change identified.<br />

Theoretical Assumptions<br />

The OC 3 <strong>Model</strong> embodies two theoretical assumptions<br />

regard<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>teraction <strong>of</strong> organizational culture<br />

and change.<br />

Theoretical Assumption 1: Different dimensions <strong>of</strong><br />

organizational culture <strong>in</strong>fluence change implementation<br />

at each stage <strong>of</strong> the process.<br />

This fundamental assumption reflects the multifaceted,<br />

pluralistic nature <strong>of</strong> organizational culture and<br />

takes <strong>in</strong>to account the manifestation <strong>of</strong> cultural ambiguity<br />

(Mart<strong>in</strong>, 2002). From a leadership perspective,<br />

it follows that develop<strong>in</strong>g a vision for change that<br />

brilliantly leverages dom<strong>in</strong>ant cultural values is <strong>in</strong>sufficient.<br />

Effective leaders must consider additional<br />

aspects <strong>of</strong> culture that explicitly or implicitly <strong>in</strong>fluence<br />

change throughout the process <strong>of</strong> implementation.

Latta / <strong>Model</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Organizational</strong> <strong>Change</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Cultural</strong> <strong>Context</strong> (OC 3 <strong>Model</strong>) 25<br />

The second theoretical assumption underly<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

OC 3 <strong>Model</strong> concerns a leader’s awareness <strong>of</strong> organizational<br />

culture.<br />

Theoretical Assumption 2: A leader’s degree <strong>of</strong> cultural<br />

awareness will determ<strong>in</strong>e his or her effectiveness <strong>in</strong><br />

facilitat<strong>in</strong>g organizational change.<br />

The OC 3 <strong>Model</strong> assumes that dur<strong>in</strong>g each stage <strong>of</strong><br />

change implementation <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g leaders’ awareness<br />

<strong>of</strong> cultural dynamics will enhance the effectiveness <strong>of</strong><br />

the change process. In the absence <strong>of</strong> an explicit cultural<br />

analysis, leaders are dependent on their tacit<br />

knowledge <strong>of</strong> organizational culture to guide decisions<br />

about align<strong>in</strong>g change <strong>in</strong>itiatives with culturally<br />

embedded processes <strong>of</strong> sensemak<strong>in</strong>g (Janson &<br />

McQueen, 2007). Leaders who lack awareness <strong>of</strong><br />

cultural dynamics <strong>in</strong> their organizations are more<br />

likely to encounter difficulties implement<strong>in</strong>g change<br />

(Hercleuous, 2001; Wilk<strong>in</strong>s & Dyer, 1988). The OC 3<br />

<strong>Model</strong> provides a framework for view<strong>in</strong>g change<br />

through the lens <strong>of</strong> culturally embedded processes <strong>of</strong><br />

sensemak<strong>in</strong>g and provides a mechanism through<br />

which leaders’ decisions about orchestrat<strong>in</strong>g change<br />

can accommodate the nuances <strong>of</strong> organizational culture<br />

at every stage <strong>of</strong> the change process.<br />

Stage 1: <strong>Cultural</strong> Analysis—Read<strong>in</strong>ess for<br />

<strong>Change</strong> Is <strong>Cultural</strong>ly Embedded<br />

Establish<strong>in</strong>g read<strong>in</strong>ess for change is recognized as<br />

an essential first step <strong>in</strong> many process models <strong>of</strong> organizational<br />

change (Bernerth, 2004; Kotter, 1996;<br />

Wal<strong>in</strong>ga, 2008). Constru<strong>in</strong>g cultural analysis as an <strong>in</strong>tegral<br />

component <strong>of</strong> assess<strong>in</strong>g read<strong>in</strong>ess for change re<strong>in</strong>forces<br />

theoretical work by Wilk<strong>in</strong>s and Dyer (1988),<br />

who posited two dimensions <strong>of</strong> culture as predispos<strong>in</strong>g<br />

an organization toward change: the fluidity <strong>of</strong> its current<br />

cultural frames and the commitment <strong>of</strong> its members<br />

to exist<strong>in</strong>g cultural tenets. Creat<strong>in</strong>g read<strong>in</strong>ess for<br />

change where it does not already exist <strong>in</strong>volves show<strong>in</strong>g<br />

discrepancies between what is and what should be<br />

(Wilk<strong>in</strong>s & Dyer, 1988). This task can be made more<br />

difficult if the envisioned change is <strong>in</strong>consistent with<br />

<strong>in</strong>stitutional culture (Kotter & Heskett, 1992). On the<br />

other hand, read<strong>in</strong>ess for change can be enhanced if<br />

discrepancies are found between the <strong>in</strong>stitution’s current<br />

status and its ideal cultural commitments (Harrison<br />

& Stokes, 1992). <strong>Cultural</strong> analysis is, thus, <strong>in</strong>tegral to<br />

assess<strong>in</strong>g read<strong>in</strong>ess for change.<br />

Proposition 1: Includ<strong>in</strong>g cultural analysis <strong>in</strong> assess<strong>in</strong>g<br />

read<strong>in</strong>ess for change facilitates an understand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong><br />

the dimensions <strong>of</strong> organizational culture that are<br />

likely to create resistance or be conducive to the<br />

<strong>in</strong>troduction <strong>of</strong> change.<br />

A high degree <strong>of</strong> read<strong>in</strong>ess for change was documented<br />

at the target <strong>in</strong>stitution prior to the creation <strong>of</strong><br />

a change agenda. Ethnographic analysis revealed the<br />

extent to which this read<strong>in</strong>ess for change was culturally<br />

embedded. A pervasive culture <strong>of</strong> prestige characterized<br />

the <strong>in</strong>stitution, fuel<strong>in</strong>g an <strong>in</strong>tense <strong>in</strong>stitutional<br />

loyalty and sense <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>dustry, an aversion to public<br />

debate <strong>of</strong> issues, and an <strong>in</strong>tolerance <strong>of</strong> nonconformity.<br />

Be<strong>in</strong>g highly motivated to protect <strong>in</strong>stitutional image,<br />

members <strong>of</strong> the organization were collectively focused<br />

on the university’s decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> national rank<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong><br />

the years prior to develop<strong>in</strong>g the strategic plan.<br />

Interpretation <strong>of</strong> the mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> this slippage had<br />

cultural significance for organization members<br />

because <strong>of</strong> the academic community’s commitment to<br />

an image <strong>of</strong> prestige. This created a sense <strong>of</strong> urgency<br />

to rega<strong>in</strong> lost national status. At the same time, the<br />

<strong>in</strong>stitution’s pervasive paternalism fueled a dependency<br />

that was threatened by the perceived falter<strong>in</strong>g<br />

status <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>stitution. The heightened respect for<br />

adm<strong>in</strong>istrative hierarchy and authority that susta<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

this paternalism created a propensity to defer to the<br />

directives <strong>of</strong> a strong, externally recruited leader who<br />

would “tell us how to get better.”<br />

Because <strong>of</strong> its unique cultural heritage, this <strong>in</strong>stitution<br />

was ripe for the <strong>in</strong>fluence <strong>of</strong> a charismatic,<br />

authoritarian leader, which it found <strong>in</strong> its new president.<br />

The coconstructed nature <strong>of</strong> organizational culture<br />

and the <strong>in</strong>stitution’s read<strong>in</strong>ess for change is<br />

underscored by the fact that this new president, who<br />

achieved award-w<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g success foster<strong>in</strong>g change at<br />

the target <strong>in</strong>stitution, had failed to achieve similar<br />

strategic goals at his former <strong>in</strong>stitution. His leadership<br />

had been poorly received <strong>in</strong> a more traditional academic<br />

<strong>in</strong>stitution where shared governance was cherished<br />

over paternalism and where national rank<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

had not triggered the same culturally embedded sense<br />

<strong>of</strong> urgency for change. The OC 3 <strong>Model</strong> captures this<br />

notion that the culture <strong>of</strong> an organization both determ<strong>in</strong>es<br />

its read<strong>in</strong>ess for change and prescribes the<br />

types <strong>of</strong> leadership likely to be effective <strong>in</strong> orchestrat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong>stitutional reform.<br />

Stage 2: Shapes Vision—Knowledge <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Organizational</strong> Culture Helps Shape the<br />

Vision for <strong>Change</strong><br />

The OC 3 <strong>Model</strong> <strong>in</strong>corporates the accepted view<br />

that knowledge <strong>of</strong> organizational culture, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g

26 Journal <strong>of</strong> Leadership & <strong>Organizational</strong> Studies<br />

awareness <strong>of</strong> subcultural variations with<strong>in</strong> an organization,<br />

plays an <strong>in</strong>tegral role <strong>in</strong> shap<strong>in</strong>g an effective<br />

vision for change (Bate et al., 2000; Sashk<strong>in</strong>, 1988).<br />

This is consistent with research suggest<strong>in</strong>g that acceptance<br />

<strong>of</strong> a change <strong>in</strong>itiative is related to its congruence<br />

with exist<strong>in</strong>g organizational identity and practice<br />

(Brooks & Bate, 1994; Wilk<strong>in</strong>s & Dyer, 1988).<br />

<strong>Organizational</strong> identity theory re<strong>in</strong>forces this idea by<br />

specify<strong>in</strong>g the behavioral, social, and environmental<br />

feedback mechanisms that underlie these processes<br />

(Whetten & Godfrey, 1998). Fram<strong>in</strong>g a vision for<br />

change that catalyzes cultural elements <strong>of</strong> the organization<br />

creates a powerful means <strong>of</strong> galvaniz<strong>in</strong>g support<br />

among followers by tapp<strong>in</strong>g these identity processes.<br />

<strong>Change</strong> theorists who focus on reform<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>stitutional<br />

culture, rather than f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g ways to l<strong>in</strong>k a vision<br />

for change to exist<strong>in</strong>g cultural commitments, construe<br />

cultural reform as a prerequisite for effect<strong>in</strong>g strategic<br />

change (Bate et al., 2000; Gayle, Tewarie & White,<br />

2000). Others assert that cultural reform occurs only as<br />

a result <strong>of</strong> behavioral change <strong>in</strong> organizations<br />

(Hercleuous, 2001). The OC 3 <strong>Model</strong> proposes a third<br />

perspective, conceiv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> organizational culture as an<br />

essential context for <strong>in</strong>form<strong>in</strong>g leaders’ decisions<br />

throughout the change process, whether or not cultural<br />

reform is required as an outcome. The OC 3 <strong>Model</strong> can<br />

be applied equally to circumstances <strong>in</strong> which cultural<br />

reform is and is not required and whether such change<br />

occurs before or after behavioral change has been<br />

effected. Because change is rarely unidimensional, the<br />

OC 3 <strong>Model</strong> suggests three propositions with respect to<br />

how cultural knowledge shapes vision.<br />

Proposition 2a: Focus<strong>in</strong>g on aspects <strong>of</strong> change consistent<br />

with exist<strong>in</strong>g culture dur<strong>in</strong>g vision<strong>in</strong>g permits<br />

leaders to engender support for broad ideological<br />

goals that may nevertheless necessitate modify<strong>in</strong>g<br />

other aspects <strong>of</strong> culture dur<strong>in</strong>g implementation.<br />

Proposition 2b (with corollary): Leverag<strong>in</strong>g cultural<br />

artifacts effectively dur<strong>in</strong>g vision<strong>in</strong>g enables leaders<br />

to foster commitment to a common ideal even before<br />

the specific nature <strong>of</strong> the changes required to achieve<br />

that vision have been articulated. Misread<strong>in</strong>g or misappropriat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

cultural symbols dur<strong>in</strong>g vision<strong>in</strong>g fosters<br />

resistance to a change agenda from the outset.<br />

Proposition 2c: Attention to subcultural variations among<br />

organizational units is <strong>in</strong>tegral to secur<strong>in</strong>g broad support<br />

for a vision that may differentially advantage<br />

certa<strong>in</strong> programmatic aspects <strong>of</strong> the organization.<br />

The vision crafted by leaders at the target <strong>in</strong>stitution<br />

<strong>in</strong> this study masterfully leveraged the power <strong>of</strong> cultural<br />

artifacts and <strong>in</strong>stitutional symbols. The university’s<br />

orig<strong>in</strong>al mascot was pulled out <strong>of</strong> mothballs and<br />

accorded new prom<strong>in</strong>ence and mean<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>in</strong> service to<br />

the reform agenda. Rituals venerat<strong>in</strong>g this mascot<br />

were enacted, <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g students and the general public.<br />

The mascot garnered attention, galvanized <strong>in</strong>terest,<br />

and generated public support for the change<br />

agenda envisioned <strong>in</strong> the strategic plan both with<strong>in</strong><br />

and outside the <strong>in</strong>stitution even before specific <strong>in</strong>itiatives<br />

for enact<strong>in</strong>g the plan had been conceived. The<br />

cultural significance <strong>of</strong> this was underscored when a<br />

midlevel adm<strong>in</strong>istrator testified regard<strong>in</strong>g the power<br />

<strong>of</strong> the re<strong>in</strong>stated mascot: “We know eng<strong>in</strong>es, we study<br />

eng<strong>in</strong>es, we understand eng<strong>in</strong>es. So us<strong>in</strong>g an eng<strong>in</strong>e<br />

to symbolize our aspirations to become the economic<br />

eng<strong>in</strong>e <strong>of</strong> the state makes sense to us!”<br />

Strategic leadership was required <strong>in</strong> resurrect<strong>in</strong>g<br />

this cultural symbol. The mascot had been replaced<br />

several decades previous by a rogue icon derived<br />

from a public event unrelated to the <strong>in</strong>stitution’s academic<br />

mission. The restoration effort was nearly<br />

thwarted, however, when a huge bronze statue <strong>of</strong> this<br />

rogue icon was donated to the university just as the<br />

new strategic plan was be<strong>in</strong>g launched. Although not<br />

rejected by the <strong>in</strong>stitution, the statue was placed strategically<br />

<strong>in</strong> a location away from the academic core<br />

where it was largely obscured by surround<strong>in</strong>g build<strong>in</strong>gs.<br />

Do<strong>in</strong>g so enabled leaders to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> focus on<br />

resurrect<strong>in</strong>g the orig<strong>in</strong>al mascot, which more effectively<br />

tapped the power <strong>of</strong> culturally embedded values<br />

to re<strong>in</strong>force goals embodied <strong>in</strong> the strategic plan<br />

related to restor<strong>in</strong>g the prom<strong>in</strong>ence <strong>of</strong> the eng<strong>in</strong>eer<strong>in</strong>g<br />

discipl<strong>in</strong>es as that university’s unique embodiment <strong>of</strong><br />

its applied scholarship mission.<br />

Subcultural differentiation. The subcultural landscape<br />

<strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>stitution was misread, or at least <strong>in</strong>sufficiently<br />

accommodated, by the new president early<br />

<strong>in</strong> the vision<strong>in</strong>g process. Initially, aspirational goals<br />

were framed solely <strong>in</strong> terms its applied scholarship<br />

mission. Whereas this commitment to applied scholarship<br />

reflected a core <strong>in</strong>stitutional value, it ignored<br />

the strength <strong>of</strong> discipl<strong>in</strong>ary subcultures rooted <strong>in</strong> the<br />

sciences and the humanities. Faculty <strong>in</strong> those discipl<strong>in</strong>es<br />

acknowledged the dom<strong>in</strong>ant culture but also<br />

asserted the value <strong>of</strong> their own contributions to the<br />

<strong>in</strong>stitutional mission. When they expressed dismay at<br />

be<strong>in</strong>g excluded from the vision for excellence, the<br />

strategic plan was amended to reflect aspirations <strong>of</strong><br />

preem<strong>in</strong>ence <strong>in</strong> applied sciences and excellence <strong>in</strong> all<br />

other academic discipl<strong>in</strong>es. This adjustment was sufficient<br />

to unite members across subcultural units <strong>in</strong><br />

support <strong>of</strong> the strategic plan.

Latta / <strong>Model</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Organizational</strong> <strong>Change</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Cultural</strong> <strong>Context</strong> (OC 3 <strong>Model</strong>) 27<br />

Stage 3: Informs Initiatives—<strong>Cultural</strong><br />

Knowledge Informs Development <strong>of</strong> Specific<br />

<strong>Change</strong> Initiatives<br />

Dur<strong>in</strong>g the plann<strong>in</strong>g stages, <strong>in</strong>stitutional culture<br />

determ<strong>in</strong>es many elements <strong>of</strong> read<strong>in</strong>ess for change <strong>in</strong> an<br />

organization and shapes leaders’ vision <strong>of</strong> a preferred<br />

future. A vision does not constitute a bluepr<strong>in</strong>t for<br />

change, however, until it has been translated <strong>in</strong>to specific<br />

change <strong>in</strong>itiatives. Understand<strong>in</strong>g organizational<br />

culture enables leaders to leverage exist<strong>in</strong>g values and<br />

behavioral norms <strong>in</strong> design<strong>in</strong>g change <strong>in</strong>terventions.<br />

Dimensions <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitutional culture <strong>in</strong>consistent with the<br />

vision may be targeted for modification.<br />

Proposition 3a: Consideration <strong>of</strong> cultural dynamics promotes<br />

development <strong>of</strong> strategic <strong>in</strong>itiatives more<br />

likely to be successful <strong>in</strong> accomplish<strong>in</strong>g the goals <strong>of</strong><br />

a change agenda.<br />

Proposition 3b: Attention to culturally embedded systems<br />

<strong>of</strong> mean<strong>in</strong>g ensure that planned change <strong>in</strong>terventions<br />

are consistent with values and behavioral<br />

norms leaders determ<strong>in</strong>e should be preserved.<br />

Proposition 3c: Discrepancies between an organization’s<br />

vision and its exist<strong>in</strong>g values and behavioral norms<br />

po<strong>in</strong>t to areas ripe for effect<strong>in</strong>g cultural change.<br />

Planned change <strong>in</strong>itiatives developed with consideration<br />

<strong>of</strong> exist<strong>in</strong>g elements <strong>of</strong> organizational culture<br />

can target aspects <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitutional performance that are<br />

consistent with its overall heritage and identity, mak<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the change <strong>in</strong>itiatives themselves a expression <strong>of</strong><br />

exist<strong>in</strong>g strengths rather than a demonstration <strong>of</strong> areas<br />

<strong>of</strong> weakness (Bate et al., 2000).<br />

Translat<strong>in</strong>g a vision for change <strong>in</strong>to specific <strong>in</strong>terventions<br />

is the task <strong>of</strong> change agents <strong>in</strong> an organization<br />

(Burke, 2008; Kotter, 1996). At the target <strong>in</strong>stitution,<br />

the provost was responsible for craft<strong>in</strong>g specific change<br />

<strong>in</strong>itiatives to enact the strategic plan. Analysis <strong>of</strong> the<br />

taxonomy <strong>of</strong> change <strong>in</strong>itiatives revealed how discrete<br />

elements <strong>of</strong> organizational culture became reflected <strong>in</strong><br />

the <strong>in</strong>terventions that emerged from the plann<strong>in</strong>g process.<br />

For each <strong>in</strong>itiative, it was possible to trace the<br />

currents <strong>of</strong> cultural mean<strong>in</strong>g that shaped the change<br />

agenda. These cultural elements were not necessarily<br />

the same aspects <strong>of</strong> culture leveraged <strong>in</strong> creat<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

sense <strong>of</strong> read<strong>in</strong>ess or vision for change.<br />

Testimony from the provost and others provided<br />

clues regard<strong>in</strong>g how cultural knowledge may have<br />

<strong>in</strong>fluenced the development <strong>of</strong> these change <strong>in</strong>itiatives,<br />

but because <strong>of</strong> the largely tacit way <strong>in</strong> which<br />

cultural sensemak<strong>in</strong>g occurs, it was evident that cultural<br />

norms <strong>of</strong>ten <strong>in</strong>fluenced decision mak<strong>in</strong>g without<br />

conscious consideration or at least <strong>in</strong> ways that were<br />

not readily articulated by the provost and other <strong>in</strong>stitutional<br />

leaders. Thus, whereas ethnographic analysis<br />

made it possible to trace the effects <strong>of</strong> organizational<br />

culture on the development <strong>of</strong> specific change <strong>in</strong>itiatives<br />

at the target <strong>in</strong>stitution, at best it can be said that<br />

these strategies were <strong>in</strong>fluenced by organizational<br />

culture, not that explicit consideration <strong>of</strong> cultural<br />

dynamics always factored <strong>in</strong>to their formulation. The<br />

OC 3 <strong>Model</strong> predicts that more explicit consideration<br />

<strong>of</strong> cultural dynamics by leaders dur<strong>in</strong>g plann<strong>in</strong>g<br />

would promote the development <strong>of</strong> change <strong>in</strong>itiatives<br />

with greater potential to affect outcomes consistent<br />

with stated <strong>in</strong>stitutional goals.<br />

Stage 4: Strategies Reflect <strong>Cultural</strong><br />

Knowledge—Effective Implementation<br />

Strategies Reflect Differential Aspects <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Organizational</strong> Culture<br />

Once the objectives <strong>of</strong> a planned change <strong>in</strong>itiative<br />

have been identified, <strong>in</strong>stitutional leaders must determ<strong>in</strong>e<br />

the most effective ways to implement desired<br />

changes. <strong>Cultural</strong> factors reflected <strong>in</strong> these implementation<br />

strategies may differ from those aspects <strong>of</strong><br />

organizational culture that provided impetus for the<br />

<strong>in</strong>itiatives. The OC 3 <strong>Model</strong> calls on leaders and<br />

change agents to recognize that because culture is<br />

multidimensional other factors will come <strong>in</strong>to play <strong>in</strong><br />

implement<strong>in</strong>g an <strong>in</strong>itiative than just those dimensions<br />

identified as the target <strong>of</strong> change. This dist<strong>in</strong>ction is<br />

significant because it illustrates that implementation<br />

strategies are not dictated by change <strong>in</strong>itiatives and<br />

can be designed to both re<strong>in</strong>force and counter aspects<br />

<strong>of</strong> culture necessary to ensur<strong>in</strong>g a desired outcome.<br />

Whether the goal <strong>of</strong> the change <strong>in</strong>itiative is to alter a<br />

fundamental aspect <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitutional culture or to effect<br />

a change that is essentially consistent with the culture<br />

<strong>of</strong> the organization, cultural knowledge can be a valuable<br />

tool for leaders <strong>in</strong> craft<strong>in</strong>g strategies and tactics<br />

for implement<strong>in</strong>g change.<br />

Proposition 4a: Effective implementation strategies<br />

take <strong>in</strong>to account different (or additional) aspects <strong>of</strong><br />

organizational culture than were considered <strong>in</strong> formulat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the change <strong>in</strong>itiative.<br />

Proposition 4b: Consideration <strong>of</strong> cultural norms can<br />

determ<strong>in</strong>e the success <strong>of</strong> change implementation<br />

<strong>in</strong>dependent <strong>of</strong> whether the change <strong>in</strong>itiative itself is<br />

consistent with <strong>in</strong>stitutional culture.<br />

Proposition 4c: Success <strong>of</strong> a change <strong>in</strong>itiative is determ<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

by the cultural implications <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>itiative<br />

itself and its implementation strategy.

28 Journal <strong>of</strong> Leadership & <strong>Organizational</strong> Studies<br />

The importance <strong>of</strong> consider<strong>in</strong>g differential aspects<br />

<strong>of</strong> organizational culture <strong>in</strong> craft<strong>in</strong>g change <strong>in</strong>itiatives<br />

and implementation strategies is illustrated by an<br />

effort to create a university-wide honors program.<br />

This <strong>in</strong>itiative reflected the espoused <strong>in</strong>stitutional<br />

value <strong>of</strong> balanc<strong>in</strong>g teach<strong>in</strong>g and research, but the<br />

implementation strategy <strong>in</strong>sufficiently took <strong>in</strong>to<br />

account the culture <strong>of</strong> unit-level determ<strong>in</strong>ism that<br />

governs curricular decisions at this university.<br />

Consequently, the first attempt to implement the <strong>in</strong>itiative<br />

was rejected by vote <strong>of</strong> the campus govern<strong>in</strong>g<br />

body because its implementation strategy called for<br />

central control <strong>of</strong> admissions to the program. After the<br />

implementation strategy was revised, the <strong>in</strong>itiative<br />

was approved. This example illustrates how the success<br />

<strong>of</strong> a change <strong>in</strong>itiative is jo<strong>in</strong>tly determ<strong>in</strong>ed by the<br />

cultural implications <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>itiative with the strategies<br />

employed to affect implementation. The OC 3<br />

<strong>Model</strong> draws attention to the importance <strong>of</strong> change<br />

agents’ consider<strong>in</strong>g both dur<strong>in</strong>g plann<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Stage 5: Embodies Intent—<strong>Change</strong> Initiatives<br />

and Their Implementation Strategies<br />

Embody Intent to Modify or Re<strong>in</strong>force<br />

<strong>Organizational</strong> Culture<br />

In some cases, this <strong>in</strong>tent may be made explicit, as<br />

when leaders target specific values or rituals for<br />

modification or elim<strong>in</strong>ation. New rituals may be<br />

<strong>in</strong>troduced or old symbols put <strong>in</strong>to hibernation. The<br />

OC 3 <strong>Model</strong> calls on leaders to identify those aspects<br />

<strong>of</strong> organizational culture targeted for modification as<br />

well as those dimensions <strong>in</strong>tended to be preserved or<br />

strengthened. Consistent with Gagliardi’s (1986) conceptual<br />

model, this process approach forestalls the<br />

perception that change requires an all-out overhaul <strong>of</strong><br />

cherished values and familiar ways <strong>of</strong> operat<strong>in</strong>g while<br />

acknowledg<strong>in</strong>g those aspects <strong>of</strong> organizational behavior<br />

that will be expected to undergo transformation.<br />

Proposition 5a: <strong>Change</strong> <strong>in</strong>itiatives and their implementation<br />

strategies embody explicit or implicit <strong>in</strong>tent to<br />

<strong>in</strong>fluence organizational culture.<br />

Proposition 5b: <strong>Change</strong> <strong>in</strong>itiatives may be designed to<br />

either modify or re<strong>in</strong>force exist<strong>in</strong>g cultural tenets.<br />

Proposition 5c: The cultural <strong>in</strong>tent embodied <strong>in</strong> a<br />

change <strong>in</strong>itiative or implementation strategy must be<br />

considered with<strong>in</strong> the larger cultural fabric <strong>in</strong> which<br />

the targeted cultural tenets operate.<br />

At the target <strong>in</strong>stitution, the overall <strong>in</strong>tent <strong>of</strong> the strategic<br />

plan was not to fundamentally alter organizational<br />

culture. Nevertheless, some change <strong>in</strong>itiatives were<br />

implemented <strong>in</strong> a way that, if successful, would<br />

modify elements <strong>of</strong> exist<strong>in</strong>g culture, whereas other<br />

<strong>in</strong>centives served to re<strong>in</strong>force established norms. An<br />

<strong>in</strong>itiative to <strong>in</strong>troduce diversity workshops illustrates<br />

how the dynamics <strong>of</strong> the OC 3 <strong>Model</strong> <strong>in</strong>forms these<br />

leadership efforts. The <strong>in</strong>itiative represented an<br />

explicit endeavor to change the cultural <strong>in</strong>tolerance <strong>of</strong><br />

nonconformity; however, alter<strong>in</strong>g this cultural tenet<br />

did not constitute an attempt to abolish the culture <strong>of</strong><br />

prestige that was susta<strong>in</strong>ed by conformity at the <strong>in</strong>stitution.<br />

In fact, other change <strong>in</strong>itiatives served to re<strong>in</strong>force<br />

the culture <strong>of</strong> prestige at the same time that<br />

specific actions were <strong>in</strong>troduced to create a more welcom<strong>in</strong>g<br />

environment for diversity. Leaders were<br />

sometimes caught <strong>of</strong>f guard by events that brought<br />

these two <strong>in</strong>itiatives <strong>in</strong>to conflict, such as when students<br />

staged a protest at a board meet<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Student protests were a rare occurrence at the target<br />

<strong>in</strong>stitution and had historically been squelched by<br />

adm<strong>in</strong>istration; the <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> these <strong>in</strong>cidents was a<br />

natural reflection <strong>of</strong> a grow<strong>in</strong>g tolerance for nonconformity.<br />

Yet adm<strong>in</strong>istrators’ <strong>in</strong>itial reaction reflected<br />

their cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g aversion to public debate, which was<br />

viewed as a threat to the culture <strong>of</strong> prestige. Initially,<br />

the protest<strong>in</strong>g students were removed and barred from<br />

attend<strong>in</strong>g the public meet<strong>in</strong>g, later be<strong>in</strong>g admitted<br />

after they agreed to not speak or otherwise disrupt<br />

proceed<strong>in</strong>gs. The <strong>in</strong>tentional <strong>in</strong>troduction <strong>of</strong> attitudes<br />

support<strong>in</strong>g greater tolerance <strong>of</strong> nonconformity had<br />

prompted a collateral impetus for more pubic debate,<br />

creat<strong>in</strong>g an un<strong>in</strong>tended threat to the culture <strong>of</strong> prestige<br />

that leaders sought to preserve. In addition to illustrat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

how culturally relevant <strong>in</strong>tent is embedded <strong>in</strong><br />

change <strong>in</strong>itiatives, this example demonstrates that the<br />

fabric <strong>of</strong> culture is a delicate weave, easily unraveled<br />

<strong>in</strong> the context <strong>of</strong> effect<strong>in</strong>g change.<br />

Stage 6: <strong>Cultural</strong> Mediation—Tacit<br />

Elements <strong>of</strong> Culture Mediate the<br />

Implementation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Change</strong><br />

Regardless <strong>of</strong> the strategies and tactics employed<br />

to implement particular change <strong>in</strong>itiatives, the impact<br />

<strong>of</strong> these efforts will be mediated by elements <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitutional<br />

culture not taken <strong>in</strong>to consideration dur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

plann<strong>in</strong>g. In some <strong>in</strong>stances, cultural dynamics may<br />

serve to facilitate the assimilation <strong>of</strong> change; <strong>in</strong> others,<br />

they may foster resistance or result <strong>in</strong> un<strong>in</strong>tended<br />

outcomes. Tacit elements <strong>of</strong> organizational culture are<br />

<strong>in</strong>stitutional dynamics not explicitly taken <strong>in</strong>to account<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g plann<strong>in</strong>g that emerge unexpectedly as significant

Latta / <strong>Model</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Organizational</strong> <strong>Change</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Cultural</strong> <strong>Context</strong> (OC 3 <strong>Model</strong>) 29<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g the process <strong>of</strong> implement<strong>in</strong>g change. These<br />

tacit cultural dynamics mediate the implementation<br />

process. The immediate effect <strong>of</strong> this mediation is<br />

facilitation or resistance to the change effort.<br />

Like the <strong>in</strong>tent embodied <strong>in</strong> change <strong>in</strong>itiatives, the<br />

cultural mediation <strong>of</strong> change implementation has<br />