STATE OF WOMEN IN CITIES 2012-2013 - UN-Habitat

STATE OF WOMEN IN CITIES 2012-2013 - UN-Habitat

STATE OF WOMEN IN CITIES 2012-2013 - UN-Habitat

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>STATE</strong> <strong>OF</strong> <strong>WOMEN</strong> <strong>IN</strong> <strong>CITIES</strong> <strong>2012</strong>-<strong>2013</strong><br />

‘advanced’ or ‘very advanced’, especially in Johannesburg (54<br />

per cent) and Kingston (49 per cent), but with 21 per cent<br />

stating there was ‘no equity’ in Rio de Janeiro.<br />

The root causes of differential access to secure tenure are<br />

complex. One factor is uneven discrimination against women<br />

in inheritance, ranging from situations, as in Swaziland, where<br />

women have no right to inherit property, to those in which they<br />

are only legally entitled to lesser shares than men. In addition,<br />

in some cases, women’s statutory rights are compromised by<br />

lack of knowledge, plural legal systems, and socio-cultural<br />

emphasis on the prerogatives of males and their blood relations<br />

over land and property. 9 It is also worth noting that even if<br />

there appears to be equality in property rights in principle, this<br />

is far less likely in practice.<br />

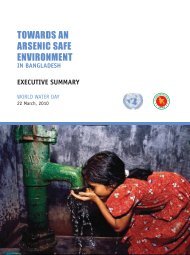

Woman and child resisting eviction from an inner-city slum in Buenos Aires, Argentina.<br />

© <strong>UN</strong>-<strong>Habitat</strong>/Pepe Mateos<br />

Male bias in inheritance and property acts therefore as major<br />

obstacle to gender equality and empowerment. Male ownership<br />

effectively equates with male control over women and there is<br />

widespread discrimination against women is nearly all aspects of<br />

housing. 10 Given male rights, women commonly face eviction<br />

and/or homelessness in the event of divorce or desertion.<br />

The same applies to widows who may be subject to ‘property<br />

grabbing’ by their in-laws, as has been noted in India in the<br />

context of women whose spouses have died of HIV/AIDS, a<br />

phenomenon also widely observed in sub-Saharan Africa. 11<br />

Negative outcomes of these processes are especially important<br />

where women are poor. The only alternatives for widows facing<br />

destitution through dispossession may be to subject themselves<br />

to various demeaning or self-sacrificial strategies to retain rights<br />

to property, such as committing to post-conjugal celibacy,<br />

or entering into forced unions with their spouses’ brothers<br />

(Levirate marriage). 12 Moreover, women may be disenfranchised<br />

as daughters, regardless of the efforts they have made to support<br />

parentsand/or brothers economically. In some cases, as noted<br />

for India, mothers may favour the inheritance of sons over<br />

daughters given the expectation that the former will provide for<br />

them in their old age. 13 Even where both spouses are alive, and<br />

women may be legal owners of land or property, their rights<br />

over sale, transfer, or daily use may be flouted. 14<br />

Although women’s long-term prospects of securing property<br />

are better in urban areas than in the countryside, partly because<br />

of greater social and economic opportunities and partly because<br />

more land and property is acquired through the market rather<br />

than inheritance, women still face widespread discrimination in<br />

cities. For example, one-third of owner-occupiers were female<br />

in a <strong>UN</strong> Gender and <strong>Habitat</strong> survey in 16 low-income urban<br />

communities in Ghana, Senegal, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia,<br />

Sri Lanka, Colombia and Costa Rica. 15<br />

Rare exceptions include South Africa, where thanks to the<br />

Department of Housing’s prioritisation of equal or preferred<br />

access to female household heads under the government subsidy<br />

programme, such units are no less likely than other households<br />

to own their home or to live in formal shelter. 16 However,<br />

the <strong>UN</strong>-<strong>Habitat</strong> survey has also shown that although men<br />

and women in Johannesburg are theoretically both eligible for<br />

housing and land subsidy support, these services are invariably<br />

registered in the names of men. 17<br />

Gender discrimination also obstructs women’s access to<br />

rental shelter, which has been more neglected policy-wise with<br />

fewer provisions to protect women as a result. 18 In Tanzania,<br />

for example, in cases where couples in rental accommodation<br />

divorce, men are more likely to stay behind. In turn, limited<br />

access by single women is compounded in some cases by<br />

stigma against HIV/AIDS. 19 Women renters may also be<br />

discriminated against in relation to sexuality, either because of<br />

issues of propriety of single women without male ‘guardians’<br />

as in southern India, 20 or in terms of lesbian women finding it<br />

difficult to rent as in Quito, Ecuador. 21<br />

Common explanations for gender disparities in accessing<br />

shelter as a whole include women’s limited access to stable<br />

employment and earnings, finance and credit. Even where<br />

women may be able to access housing, the prospect of property<br />

taxes may discourage them from claiming title. 22 Additional<br />

factors dissuading women from pursuing title in their own<br />

right, or even opting for joint spousal registration, include<br />

deeply entrenched patterns of patriarchy which require<br />

women to defer to men’s wishes in respect of ownership and<br />

management of household assets. 23 The injustice of these<br />

gender disparities is further underscored by the fact that women<br />

28