STATE OF WOMEN IN CITIES 2012-2013 - UN-Habitat

STATE OF WOMEN IN CITIES 2012-2013 - UN-Habitat

STATE OF WOMEN IN CITIES 2012-2013 - UN-Habitat

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>STATE</strong> <strong>OF</strong> <strong>WOMEN</strong> <strong>IN</strong> <strong>CITIES</strong> <strong>2012</strong>-<strong>2013</strong><br />

communicable illness such as tuberculosis. The prevalence of<br />

malnutrition in India and Bangladesh is more than double in<br />

slums than in non-slum areas, at 54 per cent versus 21 per cent,<br />

and 51.4 per cent versus 24 per cent respectively (<strong>UN</strong>-<strong>Habitat</strong>,<br />

2010d:1). In the Democratic Republic of Congo, too, 41 per<br />

cent of children are malnourished in slums compared with 16<br />

per cent of their non-slum counterparts.<br />

Furthermore, slum dwellers also suffer a disproportionate<br />

vulnerability to health conditions linked with inadequate<br />

healthcare and diet, such as anaemia. 32 There is also evidence<br />

that behaviourally-related health issues such as smoking are<br />

more prevalent in slums. For example, in Bangladesh smoking<br />

cigarettes and ‘bidis’ (hand-rolled cigarettes which have<br />

higher concentrations of tar and nicotine) is more widespread<br />

in slums. This has ‘devastating effects’ for people living in<br />

poverty in terms of diverting income from food expenditure<br />

and exacerbating the risks of respiratory disease commonly<br />

associated with overcrowded and poorly-ventilated dwellings. 33<br />

Unfavourable health conditions in slums have led to the<br />

notion of an ‘urban penalty’ in health. 34 This suggests that even<br />

if conditions tend to be better than in rural areas, the ‘urban<br />

advantage’ in respect of lower mortality rates and nutritional<br />

status for children in particular disappears once wealth,<br />

education and other socio-economic indicators are controlled<br />

for. 35<br />

For women in slums, the urban penalty is arguably greater<br />

than for men as the risks to physical and mental well-being<br />

are sharpened by a range of ‘stressors’ attached to their inputs<br />

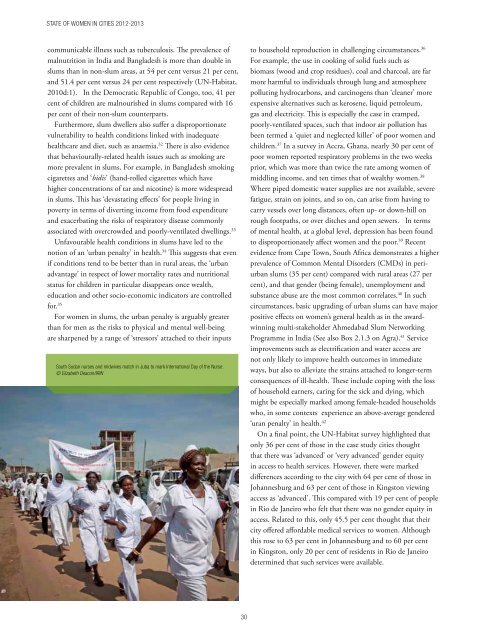

South Sudan nurses and midwives match in Juba to mark International Day of the Nurse.<br />

© Elizabeth Deacon/IR<strong>IN</strong><br />

to household reproduction in challenging circumstances. 36<br />

For example, the use in cooking of solid fuels such as<br />

biomass (wood and crop residues), coal and charcoal, are far<br />

more harmful to individuals through lung and atmosphere<br />

polluting hydrocarbons, and carcinogens than ‘cleaner’ more<br />

expensive alternatives such as kerosene, liquid petroleum,<br />

gas and electricity. This is especially the case in cramped,<br />

poorly-ventilated spaces, such that indoor air pollution has<br />

been termed a ‘quiet and neglected killer’ of poor women and<br />

children. 37 In a survey in Accra, Ghana, nearly 30 per cent of<br />

poor women reported respiratory problems in the two weeks<br />

prior, which was more than twice the rate among women of<br />

middling income, and ten times that of wealthy women. 38<br />

Where piped domestic water supplies are not available, severe<br />

fatigue, strain on joints, and so on, can arise from having to<br />

carry vessels over long distances, often up- or down-hill on<br />

rough footpaths, or over ditches and open sewers. In terms<br />

of mental health, at a global level, depression has been found<br />

to disproportionately affect women and the poor. 39 Recent<br />

evidence from Cape Town, South Africa demonstrates a higher<br />

prevalence of Common Mental Disorders (CMDs) in periurban<br />

slums (35 per cent) compared with rural areas (27 per<br />

cent), and that gender (being female), unemployment and<br />

substance abuse are the most common correlates. 40 In such<br />

circumstances, basic upgrading of urban slums can have major<br />

positive effects on women’s general health as in the awardwinning<br />

multi-stakeholder Ahmedabad Slum Networking<br />

Programme in India (See also Box 2.1.3 on Agra). 41 Service<br />

improvements such as electrification and water access are<br />

not only likely to improve health outcomes in immediate<br />

ways, but also to alleviate the strains attached to longer-term<br />

consequences of ill-health. These include coping with the loss<br />

of household earners, caring for the sick and dying, which<br />

might be especially marked among female-headed households<br />

who, in some contexts experience an above-average gendered<br />

‘uran penalty’ in health. 42<br />

On a final point, the <strong>UN</strong>-<strong>Habitat</strong> survey highlighted that<br />

only 36 per cent of those in the case study cities thought<br />

that there was ‘advanced’ or ‘very advanced’ gender equity<br />

in access to health services. However, there were marked<br />

differences according to the city with 64 per cent of those in<br />

Johannesburg and 63 per cent of those in Kingston viewing<br />

access as ‘advanced’. This compared with 19 per cent of people<br />

in Rio de Janeiro who felt that there was no gender equity in<br />

access. Related to this, only 45.5 per cent thought that their<br />

city offered affordable medical services to women. Although<br />

this rose to 63 per cent in Johannesburg and to 60 per cent<br />

in Kingston, only 20 per cent of residents in Rio de Janeiro<br />

determined that such services were available.<br />

30