Scale Development of Meaning-Focused Coping

Scale Development of Meaning-Focused Coping

Scale Development of Meaning-Focused Coping

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

This article was downloaded by: [Peking University], [Yiqun Gan]<br />

On: 22 December 2012, At: 20:16<br />

Publisher: Routledge<br />

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered<br />

<strong>of</strong>fice: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> Loss and Trauma:<br />

International Perspectives on Stress &<br />

<strong>Coping</strong><br />

Publication details, including instructions for authors and<br />

subscription information:<br />

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/upil20<br />

<strong>Scale</strong> <strong>Development</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Meaning</strong>-<strong>Focused</strong><br />

<strong>Coping</strong><br />

Yiqun Gan a , Mingzhu Guo a & Jing Tong a<br />

a Department <strong>of</strong> Psychology, Peking University, Beijing, China<br />

Accepted author version posted online: 02 Apr 2012.<br />

To cite this article: Yiqun Gan , Mingzhu Guo & Jing Tong (2013): <strong>Scale</strong> <strong>Development</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Meaning</strong>-<br />

<strong>Focused</strong> <strong>Coping</strong>, Journal <strong>of</strong> Loss and Trauma: International Perspectives on Stress & <strong>Coping</strong>, 18:1,<br />

10-26<br />

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2012.678780<br />

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE<br />

Full terms and conditions <strong>of</strong> use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions<br />

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any<br />

substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,<br />

systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.<br />

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation<br />

that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy <strong>of</strong> any<br />

instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary<br />

sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings,<br />

demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or<br />

indirectly in connection with or arising out <strong>of</strong> the use <strong>of</strong> this material.

Journal <strong>of</strong> Loss and Trauma, 18:10–26, 2013<br />

Copyright # Taylor & Francis Group, LLC<br />

ISSN: 1532-5024 print=1532-5032 online<br />

DOI: 10.1080/15325024.2012.678780<br />

<strong>Scale</strong> <strong>Development</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Meaning</strong>-<strong>Focused</strong><br />

<strong>Coping</strong><br />

YIQUN GAN, MINGZHU GUO, and JING TONG<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Psychology, Peking University, Beijing, China<br />

Downloaded by [Peking University], [Yiqun Gan] at 20:16 22 December 2012<br />

The objectives <strong>of</strong> the current study were to develop an inventory<br />

that measures meaning-focused coping and to explore its reliability<br />

and validity. In total, 668 middle school students who had experienced<br />

significant negative events were recruited. The <strong>Meaning</strong>-<br />

<strong>Focused</strong> <strong>Coping</strong> Questionnaire included 26 items within eight<br />

dimensions: Changes in Situational Beliefs, Changes in Global<br />

Beliefs, Changes in Goals, <strong>Meaning</strong> Making, Long-Term Prevention<br />

Strategies, Rational Use <strong>of</strong> Resources, Acceptance, and Heuristic<br />

Thinking. Confirmatory factor analysis showed that the questionnaire<br />

had good construct validity. The results based on item<br />

response theory indicated that all <strong>of</strong> the item discrimination values<br />

were greater than 0.5.<br />

KEYWORDS classical test theory, item response theory, meaningfocused<br />

coping, meaning-making, validity<br />

<strong>Meaning</strong>-focused coping (MFC) has been proposed as an important type <strong>of</strong><br />

coping that is distinct from problem-focused coping and emotion-focused<br />

coping (Park & Folkman, 1997). <strong>Meaning</strong>-focused coping does not attempt<br />

to change a problematic situation, and it does not directly decrease pressure<br />

that is caused by negative emotions or distress. Instead, it aims to change the<br />

ways in which an individual evaluates a situation and to better reconcile beliefs,<br />

goals, and stressful situations (Pearlin, 1991). Many studies have demonstrated<br />

that meaning-focused coping and adaptation are related (Holahan, Moos,<br />

Holahan, & Brennan, 1995), especially when an uncontrollable stressor, such<br />

Received 3 February 2012; accepted 16 March 2012.<br />

Preparation <strong>of</strong> this article was supported by the Natural Science Foundation <strong>of</strong> China<br />

(Project Number 31070913). This research was also partly sponsored by the Jet Li One<br />

Foundation Project.<br />

Address correspondence to Yiqun Gan, Department <strong>of</strong> Psychology, Peking University,<br />

Beijing 100871, China. E-mail: ygan@pku.edu.cn<br />

10

<strong>Meaning</strong>-<strong>Focused</strong> <strong>Coping</strong> 11<br />

Downloaded by [Peking University], [Yiqun Gan] at 20:16 22 December 2012<br />

as illness or loss, is involved (Moskowitz, Folkman, Collette, & Yittingh<strong>of</strong>f,<br />

1996).<br />

In the coping process <strong>of</strong> meaning evaluation, the individual evaluates the<br />

positive meaning <strong>of</strong> an event or events. The person must answer questions,<br />

such as ‘‘Why did this happen?’’ (e.g., Dollinger, 1986), ‘‘Why did this happen<br />

to me?’’ (e.g., Frazier & Schauben, 1994), and ‘‘What part(s) <strong>of</strong> my life changed<br />

after the incident?’’ (e.g., Collins, Taylor, & Skokan, 1990). Park and Folkman<br />

(1997) noted that meaning-focused coping may yield positive consequences<br />

by strengthening social resources and enhancing personal resources.<br />

Folkman (2009) noted the need to develop a questionnaire about<br />

meaning-focused coping. She commented that meaning-focused coping is<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten measured at a very early stage and that a variety <strong>of</strong> coping-related tools<br />

must be developed, especially tools that facilitate stress-related growth and<br />

benefit-seeking. In addition, most studies that have assessed meaning-focused<br />

coping have been limited in scope. For example, some studies have examined<br />

meaning-focused coping using certain dimensions <strong>of</strong> the COPE scale that was<br />

developed by Carver (1997), whereas others have assessed only emotional<br />

processes (the processes by which an individual understands his or her<br />

feelings) and failed to include cognitive processes (e.g., Stanton, Dan<strong>of</strong>f-Burg,<br />

& Huggins, 2002). Moreover, some studies use very simple questions, such as<br />

‘‘How <strong>of</strong>ten have you found yourself searching to make sense <strong>of</strong> your illness?’’<br />

or ‘‘Why me?’’ (e.g., Roberts, Lepore, & Helgeson, 2006).<br />

Therefore, it is important to develop a new measure that can effectively<br />

and systematically reflect the processes that are involved in meaning-focused<br />

coping strategies. The aim <strong>of</strong> the current study was to develop a meaningfocused<br />

coping questionnaire for this purpose.<br />

CHANGES IN GLOBAL BELIEFS AND SITUATIONAL BELIEFS<br />

One highlight <strong>of</strong> the existing research about MFC is the meaning-making<br />

model proposed by Park and colleagues (Park & Folkman, 1997). According<br />

to this model, a person who suffers a significant loss tends to perceive a discrepancy<br />

between situational meaning (the appraised meaning <strong>of</strong> the event)<br />

and global meaning (the set <strong>of</strong> beliefs that the individual usually holds) that<br />

induces psychological distress. This discrepancy leads an individual to<br />

engage in meaning-making processes in which he or she changes either<br />

situational or global meanings (or both) that are related to a stressful event<br />

to reduce the existing discrepancy and psychological distress.<br />

However, the meaning-making model does not differentiate between<br />

changes to global meaning and situational meaning, although making<br />

changes to one type <strong>of</strong> meaning or the other may yield different adaptation<br />

outcomes. If people who suffer a loss change their sense <strong>of</strong> global meaning<br />

by concluding that the world is less fair, benevolent, and controllable than

12 Y. Gan et al.<br />

they previously imagined, will they become better adjusted because doing so<br />

minimizes the discrepancy between their worldview and the situation in<br />

question? This idea is contrary to the results <strong>of</strong> previous studies (e.g., Xie,<br />

Liu, & Gan, 2011) and even to what we know based on common sense.<br />

Xie et al. (2011) found that 5 months after the Sichuan earthquake, earthquake<br />

survivors believed more strongly in the justice <strong>of</strong> the world than did<br />

university students who had not experienced the earthquake. This belief in<br />

the justice <strong>of</strong> the world helped the earthquake survivors reduce their levels<br />

<strong>of</strong> uncertainty, anxiety, and depression.<br />

Downloaded by [Peking University], [Yiqun Gan] at 20:16 22 December 2012<br />

THE ROLE OF MODERN TEST THEORY IN DEVELOPING<br />

QUESTIONNAIRES<br />

Classical test theory (CTT) is mainly associated with the true score model.<br />

Although CTT is a common method <strong>of</strong> preparing psychological tests, it has<br />

three shortcomings: (a) Because item analysis in CTT was conducted based<br />

on project statistics, test results are seriously impacted by the random differences<br />

between samples; (b) CTT cannot predict the probability <strong>of</strong> a correct<br />

participant response within a new project; and (c) CTT assumes that the standard<br />

error <strong>of</strong> measurement is equal for all participants, which is impossible.<br />

Modern test theory was developed to address these three issues.<br />

Item response theory (IRT) is comprised <strong>of</strong> a set <strong>of</strong> systems and<br />

mathematical models for test scoring, item analysis, and reliability analysis<br />

(Thissen & Steinberg, 2009). By defining the parameters <strong>of</strong> the functional<br />

relationships between explicit responses and potential characteristic variables,<br />

IRT estimates both tested abilities and item parameters using parameter<br />

estimation. Thus, IRT is a more intuitive and precise method than a<br />

CTT-based assessment in assessing the properties <strong>of</strong> each project and the<br />

abilities <strong>of</strong> each participant.<br />

In developing psychological tests, one should <strong>of</strong>ten combine classical<br />

and modern test theories. Item response theory can test and analyze item<br />

information, discrimination, and project characteristics using traditional<br />

exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis. In the past, some<br />

researchers (e.g., Andrew & Petrides, 2010) have successfully applied IRT<br />

approaches to the development <strong>of</strong> psychological questionnaires.<br />

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES OF THE PRESENT STUDY<br />

Since Park and Folkman (1997) proposed the construct <strong>of</strong> meaning-focused<br />

coping, other researchers (e.g., Schwarzer & Knoll, 2003) have provided evidence<br />

indicating that method <strong>of</strong> coping does indeed occur. However, this<br />

topic has not received widespread attention, and the number <strong>of</strong> related studies<br />

has been relatively small. One reason for this lack <strong>of</strong> research may be

<strong>Meaning</strong>-<strong>Focused</strong> <strong>Coping</strong> 13<br />

Downloaded by [Peking University], [Yiqun Gan] at 20:16 22 December 2012<br />

that there is no reliable measure <strong>of</strong> meaning-focused coping (Folkman,<br />

2009). Therefore, the objective <strong>of</strong> this research was to develop a reliable<br />

questionnaire that reflects the meaning-making process, as proposed by Park<br />

and Folkman (1997), and that is capable <strong>of</strong> differentiating between an individual’s<br />

efforts to change his or her global beliefs and the individual’s efforts<br />

to adjust his or her situational beliefs.<br />

In the present study, we focused on students who had experienced an<br />

earthquake in 2008. Our survey was conducted 2 years after the 2008 Sichuan<br />

earthquake. By that time, the daily lives <strong>of</strong> the survivors would have essentially<br />

returned to normal, and thus their coping mechanisms were expected<br />

to exhibit long-term adaptation. They were asked to answer questions about<br />

the changes that occurred in their lives due to the earthquake. Although the<br />

initial restoration <strong>of</strong> the affected area has been completed, the impact <strong>of</strong> the<br />

earthquake will last for a much longer period. Therefore, it is both necessary<br />

and meaningful to study meaning-focused coping 2 years after the occurrence<br />

<strong>of</strong> an earthquake.<br />

We discuss meaning-focused coping in this uncontrollable, irreversible,<br />

and traumatic situation and address the question <strong>of</strong> whether meaningfocused<br />

coping plays a protective role in the long-term mental health <strong>of</strong><br />

the affected individuals. Toward this end, we tested two hypotheses. First,<br />

we aimed to use CTT and IRT methods to develop a questionnaire about<br />

meaning-focused coping, and thus the resulting instrument should have<br />

adequate psychometric properties. Second, changes in situational meaning<br />

will be better predictors <strong>of</strong> psychological adjustment than changes in global<br />

meaning.<br />

Participants and Procedures<br />

SAMPLE 1<br />

METHODS<br />

We first conducted structured interviews with adolescents who had experienced<br />

traumatic events. Purposeful sampling, which has been considered<br />

an appropriate sampling approach in qualitative research (Marshall, 1996),<br />

was used to select the interviewees. Two selection criteria were used: the<br />

time that had elapsed since the traumatic incident and the impact and controllability<br />

<strong>of</strong> the traumatic event. To differentiate between situational and<br />

global meaning, only participants who had suffered trauma within 1 year<br />

<strong>of</strong> our survey were selected. The respondents were instructed to rate the<br />

impact and controllability <strong>of</strong> the event on 7-point scales. On the impact scale,<br />

1 indicates a ‘‘very small’’ impact and 7 indicates a ‘‘very large’’ impact; on the<br />

controllability scale, 1 indicates a ‘‘completely controllable’’ event, whereas a<br />

rating <strong>of</strong> 7 indicates a ‘‘completely uncontrollable’’ event. We screened the

14 Y. Gan et al.<br />

Downloaded by [Peking University], [Yiqun Gan] at 20:16 22 December 2012<br />

respondents to identify those who met our criteria, having reported both<br />

impact and controllability values that were greater than 4. The recruitment<br />

process was ended after the maximum amount <strong>of</strong> possible information had<br />

been obtained from the interviews. The final sample that was selected for<br />

further interviews was comprised <strong>of</strong> 15 middle school or university students,<br />

each <strong>of</strong> whom had experienced a critical illness, a natural disaster, or the loss<br />

<strong>of</strong> a family member. Four <strong>of</strong> these students were male, and 11 were female.<br />

Two graduate students who had majored in clinical psychology conducted<br />

the interviews. The interviewees were assured that their responses would<br />

be kept confidential and would only be used for the purpose <strong>of</strong> this study. All<br />

15 respondents agreed that their responses could be recorded and provided<br />

written informed consent.<br />

The interview outline included 11 topics that addressed the five major<br />

areas <strong>of</strong> meaning-focused coping proposed by Folkman (2007), as follows.<br />

First, meaning-focused coping may involve readjusting the perceived priority<br />

<strong>of</strong> events and developing a proactive attitude toward life in which loss is<br />

accepted. For example, a mother who must give up her job to take care <strong>of</strong><br />

her sick child may newly assign family a higher priority level than she does<br />

her career. Second, meaning-focused coping may involve goal adjustment.<br />

Individuals may abandon the pursuit <strong>of</strong> unattainable goals and instead focus<br />

their efforts solely on pursuing attainable goals. Third, meaning-focused<br />

coping may also involve seeking benefits from the events encountered and<br />

viewing them from a more positive perspective. A person who exhibits<br />

meaning-focused coping might experience personal growth that will make<br />

him or her more lenient, patient, and wise. A fourth potential method <strong>of</strong><br />

meaning-focused coping is the use <strong>of</strong> benefit reminders. These cues lead<br />

individuals to remind themselves about the benefits <strong>of</strong> a traumatic event,<br />

as mentioned above. Finally, meaning-focused coping can involve assigning<br />

meanings to daily events and being appreciative <strong>of</strong> and grateful for usual and<br />

trivial things. An example <strong>of</strong> a question that was asked during the interviews<br />

was ‘‘Recall the way in which you handled the incident at the time that it<br />

occurred. Did you try to think <strong>of</strong> any positive aspects <strong>of</strong> it?’’ Each interview<br />

lasted approximately 40 minutes.<br />

The original transcripts from each case were coded by two researchers.<br />

The coding rubric organized the transcribed content into seven categories:<br />

(a) changes in situational meaning (in which the interviewees reappraised<br />

the meaning <strong>of</strong> the traumatic events), (b) rumination (repeated thinking<br />

about why an event occurred or why it happened to a particular person),<br />

(c) changes in global meaning (in which the usually held beliefs <strong>of</strong> an individual<br />

are shaken), (d) acceptance (i.e., the individual accepts the trauma in<br />

its entirety), (e) perspective and vision (i.e., the individual seeks a new perspective<br />

on his or her daily life), (f) diverting attention away from the event,<br />

and (g) the rational use <strong>of</strong> resources (which involves learning to use available<br />

resources more reasonably).

<strong>Meaning</strong>-<strong>Focused</strong> <strong>Coping</strong> 15<br />

Downloaded by [Peking University], [Yiqun Gan] at 20:16 22 December 2012<br />

Folkman (2007) proposed five categories <strong>of</strong> meaning-focused coping<br />

based on clinical observations. These five categories include general rather<br />

than specific strategies (e.g., venting is a specific coping strategy). The interview<br />

questions that were used in the current study were outlined according<br />

to the five categories <strong>of</strong> meaning-focused coping that had been described by<br />

Folkman (2007) and yielded measurements for 60 specific coping behaviors<br />

within the seven aforementioned dimensions. These seven dimensions can<br />

be regarded as parts <strong>of</strong> the process <strong>of</strong> meaning-making derived from the<br />

qualitative data.<br />

Investigator triangulation was used to maximize the reliability and validity<br />

<strong>of</strong> the qualitative study (Golafshani, 2003). Two master’s students in<br />

applied psychology (who both worked independently <strong>of</strong> the researchers<br />

conducting the current study) were invited to collaborate in developing ideas<br />

for and explanations <strong>of</strong> the coding and categorization <strong>of</strong> the interview data.<br />

All <strong>of</strong> the investigators discussed their individual findings, and the group<br />

reached a conclusion.<br />

From the coded responses, we developed a 60-item initial questionnaire<br />

that assessed the seven dimensions described here.<br />

SAMPLE 2<br />

Next, we sent 700 questionnaires to a middle school in Guangdong Province.<br />

In total, 675 were returned; <strong>of</strong> those, 660 were valid, yielding an effective<br />

response rate <strong>of</strong> 94.29%. Fifteen participants were excluded because more<br />

than one-third <strong>of</strong> the data from each <strong>of</strong> their questionnaires was missing.<br />

The same screening criteria that were used to screen the Sample 1 participants<br />

were applied to this group; the participants were required to select<br />

both controllability and impact ratings <strong>of</strong> at least 4 on a 7-point scale for<br />

the event to be included in the later analysis. In total, 314 survey respondents<br />

met our inclusion criteria; in the past two years, each included respondent<br />

had experienced at least one significant negative life event and considered<br />

this event to be both influential and uncontrollable. The data for these<br />

individuals were retained for further analysis.<br />

Of the 314 participants, 94 were men, 217 were women, and 3 did not<br />

report their gender. In addition, 174 <strong>of</strong> the participants were in year 1 <strong>of</strong> middle<br />

school, 126 were in year 2, and 14 did not indicate their grade in school.<br />

The participants ranged from 15 to 27 years in age, and the mean age <strong>of</strong> the<br />

sample was 17.62 years (SD ¼ 1.46). Respondents who completed all <strong>of</strong> the<br />

questionnaires were compensated with a small gift.<br />

SAMPLE 3<br />

Next, 400 questionnaires were sent to middle schools in Mianyang City,<br />

China. Mianyang was among the most strongly affected areas in the 2008

16 Y. Gan et al.<br />

Downloaded by [Peking University], [Yiqun Gan] at 20:16 22 December 2012<br />

Sichuan earthquake. Some <strong>of</strong> the school buildings collapsed, and the school<br />

resources in the area were seriously damaged. Some students in this area had<br />

family members and classmates who died or were seriously injured during<br />

the earthquake.<br />

In total, 371 <strong>of</strong> the 400 questionnaires were returned, and 339 <strong>of</strong> these<br />

were valid; thus, the effective response rate was 84.8%. Of the valid respondents,<br />

173 were boys, 160 were girls, and 6 did not report their gender; 163<br />

students were in year 1, 175 were in year 2, and 1 did not report a grade. The<br />

ages <strong>of</strong> the participants ranged from 14 to 19 years, and the mean age <strong>of</strong> the<br />

group was 16.52 years (SD ¼ 0.80).<br />

All <strong>of</strong> the participants signed informed consent forms. These forms<br />

informed the participants that responding to the questionnaires might induce<br />

uncomfortable feelings by asking them to recall traumatic events. The participants<br />

were also informed that they should feel free to stop answering the<br />

questions at any time and that their responses would be destroyed.<br />

Measures<br />

COPE<br />

We used the ‘‘acceptance’’ and ‘‘positive reframing’’ dimensions <strong>of</strong> the<br />

28-item Brief COPE that was developed by Carver (1997). The scale contains<br />

14 dimensions, and each dimension includes two items. The endpoints <strong>of</strong> the<br />

scales in this assessment are 1 (‘‘I do not usually do this’’) and 4 (‘‘I usually do<br />

this’’) and are used to represent the extent to which a respondent employs<br />

various coping strategies when faced with stressful events.<br />

SELF-RATING DEPRESSION SCALE<br />

The English version <strong>of</strong> the Self-Rating Depression <strong>Scale</strong> (SDS) was originally<br />

developed by Zung, Durham, Richards, Gables, and Short (1965). The<br />

Chinese version has been revised and has exhibited sound reliability and validity<br />

(Zhang, 1993). The SDS is a 20-item, self-administered questionnaire<br />

that measures depressive symptomatology. The scale endpoints in this questionnaire<br />

are 1 (never or rarely) and 4 (most <strong>of</strong> the time). High scores indicate<br />

high levels <strong>of</strong> depression. The Cronbach alpha for this measure as obtained<br />

in the current study was .83.<br />

POSITIVE AND NEGATIVE AFFECT SCHEDULE (PANAS)<br />

PANAS is an adjective scale that was developed by Watson, Clark, and<br />

Tellegen (1988). PANAS contains 20 items that measure both positive (e.g.,<br />

interested) and negative (e.g., guilt) emotional states. The endpoints <strong>of</strong> this<br />

scale are 1 (none or a little) and 5 (very much). The Cronbach alpha for

<strong>Meaning</strong>-<strong>Focused</strong> <strong>Coping</strong> 17<br />

the Chinese version in the current study was .83 for positive affect and .86 for<br />

negative affect.<br />

INDEX OF WELL-BEING AND INDEX OF GENERAL AFFECT<br />

Downloaded by [Peking University], [Yiqun Gan] at 20:16 22 December 2012<br />

This scale was developed by Campbell, Converse, and Rodgers (1976) and<br />

contains two parts: The index <strong>of</strong> general affect includes eight items and has<br />

a weight <strong>of</strong> 1, and the index <strong>of</strong> life satisfaction includes one item and has a<br />

weight <strong>of</strong> 1.1. This scale is widely used in empirical research. The Cronbach<br />

alpha for the Chinese version <strong>of</strong> this scale, as obtained in the current study,<br />

was .89.<br />

RESULTS<br />

Exploratory Factor Analysis and Item Analyses<br />

Because our primary aim was to develop a scale, we retained only those<br />

items that best represented meaning-focused coping, creating our measure<br />

for this construct in the most parsimonious way possible. Thus, we conducted<br />

a preliminary principal component analysis with oblique rotation using<br />

the data that we had obtained from Sample 2. The pattern <strong>of</strong> factor loadings<br />

showed that 17 items had values that were smaller than 0.3. Sixteen other<br />

items had double loadings on two or more factors. These 33 items were<br />

eliminated, yielding a set <strong>of</strong> 27 items that met our criteria for item retention.<br />

These items were then subjected to principal axis factoring to assess the factor<br />

structure <strong>of</strong> the meaning-focused coping model (see Table 1).<br />

An eight-factor solution emerged. As shown in Table 2, the eigenvalues<br />

for this solution ranged from 1.69 to 2.64, and the model explained 64.35% <strong>of</strong><br />

the total variance. The eight factors were as follows: Changes in Situational<br />

Beliefs, Changes in Global Beliefs, Changes in Goals, Rumination, Long-Term<br />

Prevention Strategies, Rational Use <strong>of</strong> Resources, Acceptance, and Heuristic<br />

Thinking (see Table 1 for details regarding the factors). The scores for these<br />

factors can also be summed to obtain a total MFC score.<br />

Confirmatory Factor Analysis<br />

Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted with the data from Sample 3 to<br />

test the hypothesis that the eight dimensions mentioned above are dimensions<br />

<strong>of</strong> meaning-focused coping. Several recommended measures <strong>of</strong> overall<br />

goodness <strong>of</strong> fit were used, including the comparative fit index (CFI),<br />

non-normed fit index (NNFI), root mean square error <strong>of</strong> approximation<br />

(RMSEA), and v 2 =df (Hu & Bentler, 1999) measures. For the CFI and the<br />

NNFI, values <strong>of</strong> at least 0.90 are desired; these values are presumed to indicate<br />

that the model fits the data acceptably well. The corresponding cut<strong>of</strong>f

18 Y. Gan et al.<br />

TABLE 1 Factor Loadings <strong>of</strong> <strong>Meaning</strong>-<strong>Focused</strong> <strong>Coping</strong> Questionnaire (MFCQ).<br />

Factor Item Loading<br />

Downloaded by [Peking University], [Yiqun Gan] at 20:16 22 December 2012<br />

Factor 1: Changes<br />

in Situational<br />

Beliefs<br />

Factor 2: <strong>Meaning</strong><br />

Making<br />

Factor 3: Changes<br />

in Global Beliefs<br />

Factor 4:<br />

Long-Term<br />

Prevention<br />

Strategies<br />

Factor 5: Rational<br />

Use <strong>of</strong><br />

Resources<br />

Factor 6:<br />

Acceptance<br />

Factor 7: Heuristic<br />

Thinking<br />

Factor 8: Changes<br />

in Goals<br />

31. I tried to consider the event from a broader standpoint. 0.83<br />

32. I looked at the issue from a broader point <strong>of</strong> view. 0.81<br />

30. When I handled other problems that arose after this 0.73<br />

event, I could reflect on the matter from more<br />

perspectives.<br />

48. I forced myself to do something constructive. 0.51<br />

10. I considered why the traumatic event happened at that 0.88<br />

moment.<br />

11. I considered why a traumatic event happened to me. 0.79<br />

9. I considered the reasons that a traumatic event happens. 0.75<br />

13. I wondered whether there is some special meaning in 0.61<br />

the occurrence <strong>of</strong> this event.<br />

5. I sought help from my faith and beliefs. 0.85<br />

4. I believed in my faith and beliefs. 0.74<br />

6. I tried to seek consolation from both my faith and beliefs. 0.74<br />

3. I tried to seek consolation from my beliefs. 0.69<br />

17. I adjusted my view on this matter continuously over 0.75<br />

time.<br />

19. Some time after the occurrence <strong>of</strong> the event, I<br />

0.75<br />

reconsidered my coping style.<br />

18. I believed, due to the enrichment <strong>of</strong> my experience, I 0.72<br />

could handle a traumatic event better.<br />

57. I accepted love and understanding from others. 0.76<br />

55. I gained strength from the help <strong>of</strong> others. 0.74<br />

56. I tried to seize opportunities that could get me out <strong>of</strong> the 0.72<br />

bad situation.<br />

24. I have accepted the fact that something had happened 0.83<br />

and that it could not be changed.<br />

27. I learned to accept the event, and it has become a part 0.81<br />

<strong>of</strong> my life.<br />

26. I have accepted the fact that things have happened. 0.62<br />

43. I changed some <strong>of</strong> my views. 0.68<br />

34. I sought the opinions <strong>of</strong> others on this matter. 0.68<br />

35. The words <strong>of</strong> my classmates or others gave me the 0.66<br />

inspiration for a new idea.<br />

2. I readjusted my goal(s) in life. 0.76<br />

8. I sought a new outlook on life and reassessed my values. 0.67<br />

1. During the course <strong>of</strong> events, I tried to establish new 0.60<br />

values.<br />

value for RMSEA is approximately 0.06. For the v 2 =df ratio, values that are<br />

less than 3 indicate adequate model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The various<br />

goodness <strong>of</strong> fit values for the questionnaire in this study were as follows:<br />

v 2 =df ¼ 2.05, RMSEA ¼ 0.06, CFI ¼ 0.94, and NNFI ¼ 0.93.<br />

Item Response Analysis<br />

Test difficulty and differentiation were examined in the total sample <strong>of</strong><br />

653 participants (Sample 2 and Sample 3) using item response theory. The

<strong>Meaning</strong>-<strong>Focused</strong> <strong>Coping</strong> 19<br />

TABLE 2 Eigenvalue and Percentage <strong>of</strong> Variance Explained by MFC Factors.<br />

Rotated percentage <strong>of</strong> variance explained<br />

Factor<br />

Eigenvalue<br />

Percentage <strong>of</strong><br />

variance explained<br />

Cumulative percentage<br />

<strong>of</strong> variance explained<br />

Downloaded by [Peking University], [Yiqun Gan] at 20:16 22 December 2012<br />

1 2.64 9.79 9.79<br />

2 2.65 9.79 19.59<br />

3 2.60 9.64 29.23<br />

4 2.08 7.70 36.93<br />

5 1.97 7.31 44.24<br />

6 1.97 7.29 51.53<br />

7 1.77 6.56 58.10<br />

8 1.69 6.26 64.35<br />

expectation-maximization algorithm method was used when data were missing.<br />

M-plus 5.0 s<strong>of</strong>tware was used to estimate and evaluate the model. The<br />

model parameters were then converted to item response parameters. Finally,<br />

S language (R s<strong>of</strong>tware) was used to render the item characteristic curves and<br />

the information function curves.<br />

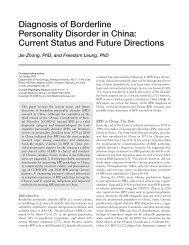

As shown in Table 3, the degrees <strong>of</strong> differentiation <strong>of</strong> the various items<br />

ranged from 0.584 to 1.918 with the exception <strong>of</strong> that <strong>of</strong> item 43, which was<br />

0.439. In total, the degrees <strong>of</strong> differentiation <strong>of</strong> 96% <strong>of</strong> the items examined<br />

were larger than 0.5, which was reasonably consistent with the requirements.<br />

In addition, project locations b1 tob4 were beyond the standard range ( 4,<br />

4) for all <strong>of</strong> the items. Two specific examples are items 11 and 27. The item<br />

information functions for these two items can be observed in the two topmost<br />

right panels <strong>of</strong> Figure 1, which implies that these project locations have<br />

TABLE 3 MFCQ Item Response Analysis.<br />

Item a b1 b2 b3 b4 Item a b1 b2 b3 b4<br />

30 1.12 2.71 1.40 0.35 1.02 55 1.00 2.78 1.16 0.17 1.51<br />

31 1.92 1.73 0.79 0.07 0.98 56 0.76 3.22 1.62 0.16 1.39<br />

32 1.46 2.19 1.02 0.06 1.20 57 0.75 3.62 1.83 0.56 1.14<br />

48 0.56 3.50 1.74 0.13 2.04 24 0.66 2.29 0.74 0.26 1.49<br />

9 1.10 1.92 0.89 0.09 1.11 26 1.64 1.94 1.01 0.19 0.65<br />

10 1.91 1.23 0.34 0.27 1.09 27 0.68 2.92 1.30 0.07 1.72<br />

11 1.11 1.79 0.64 0.13 1.33 34 0.71 2.28 0.94 0.28 2.16<br />

13 0.58 2.88 1.29 0.26 2.06 35 1.40 2.13 0.89 0.19 1.62<br />

3 0.87 1.78 0.56 0.45 2.09 43 0.44 4.66 1.29 0.90 3.53<br />

4 1.04 1.81 0.78 0.12 0.95 1 0.98 2.35 0.19 0.82 2.14<br />

5 1.98 1.26 0.32 0.36 1.40 2 0.93 1.51 0.26 1.20 2.26<br />

6 1.15 1.63 0.43 0.42 1.72 8 0.64 2.67 0.32 0.80 2.35<br />

17 1.03 2.01 0.97 0.13 1.19<br />

18 1.08 2.55 1.65 0.73 0.46<br />

19 0.93 2.43 1.35 0.24 1.06

20 Y. Gan et al.<br />

Downloaded by [Peking University], [Yiqun Gan] at 20:16 22 December 2012<br />

FIGURE 1 Test information for each dimension and the whole test.<br />

approximately equal numbers <strong>of</strong> positive and negative values. This result, in<br />

turn, means that these items are suitable for the average participant; they are<br />

not skewed toward participants with high or low capabilities. However, b1<strong>of</strong><br />

item 43 was 4.657I; that is, it is beyond the standard range ( 4, 4). The item<br />

information function for this item can be observed in the bottom right panel<br />

<strong>of</strong> Figure 1. This was an extreme value, and thus we removed this item from<br />

the scale.<br />

Figure 1 shows each dimension and the test information function for the<br />

distribution. As can be observed from the figure, dimensions 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, and<br />

8 and the test in its entirety follow a normal distribution; none <strong>of</strong> these<br />

dimensions were skewed toward either the high-trait-level test <strong>of</strong> the distribution<br />

or toward low-trait-level participants. However, dimension 1 appears<br />

to follow a bimodal distribution, and dimension 3 appears to be abnormally<br />

distributed. In addition, the test information function value was moderate<br />

at 15.

TABLE 4 Convergent Validity <strong>of</strong> the MFCQ.<br />

<strong>Meaning</strong>-<strong>Focused</strong> <strong>Coping</strong> 21<br />

Factor<br />

1<br />

Factor<br />

2<br />

Factor<br />

3<br />

Factor<br />

4<br />

Factor<br />

5<br />

Factor<br />

6<br />

Factor<br />

7<br />

Factor<br />

8<br />

Total<br />

score<br />

Acceptance 0.20 0.06 0.03 0.20 0.24 0.53 0.12 0.09 0.28 <br />

Positive 0.35 0.20 0.27 0.23 0.29 0.19 0.19 0.19 0.39 <br />

reframing<br />

Criterion item a 0.43 0.27 0.27 0.26 0.28 0.06 0.37 0.24 0.45 <br />

Note. The meaning-focused coping scored was the total score for acceptance and positive reframing.<br />

Subjects came from earthquake-stricken areas (N ¼ 339).<br />

a ‘‘To what extent do you attempt to create or find meaning from the significant loss?’’<br />

p < .01.<br />

Downloaded by [Peking University], [Yiqun Gan] at 20:16 22 December 2012<br />

Convergent and Discriminant Validity<br />

Following Affleck, the Acceptance and Positive Reframing dimensions from<br />

the Brief COPE scales were used as criteria for establishing concurrent validity<br />

(Affleck, Tennen, Croog, & Levine, 1987). The results showed that most<br />

dimensions were significantly correlated with both Acceptance and Positive<br />

Reframing and that most dimensions were also significantly correlated with<br />

the item ‘‘To what extent did you attempt to create or find meaning from your<br />

loss?’’ (data shown in Table 4). In addition, changes in situational meaning<br />

were found to be more significantly related to positive psychological<br />

outcomes than were changes in global meaning.<br />

The overall scale reliability was 0.859, and the subscale reliability levels<br />

were 0.801, 0.789, 0.804, 0.707, 0.627, 0.664, 0.603, and 0.616 for factors 1 to<br />

8, respectively.<br />

Criterion Validity <strong>of</strong> the MFCQ<br />

The participants were divided into two groups, a high-stress-exposure group<br />

(n ¼ 91) and a low-stress-exposure group (n ¼ 245), based on the number <strong>of</strong><br />

casualties among their family and friends and the severity <strong>of</strong> the damage to<br />

TABLE 5 Means, Standard Deviations, and Pearson Correlations for Study Variables<br />

(N ¼ 339).<br />

Variable M SD 1 2 3 4 5 6<br />

1. <strong>Meaning</strong>-focused coping 57.09 13.50 1.00<br />

2. Posttraumatic growth 13.95 3.81 .51 1.00<br />

3. Well-being 5.98 2.34 .33 .40 1.00<br />

4. Positive affect 32.86 6.40 .47 .53 .54 1.00<br />

5. Negative affect 22.95 6.11 .02 .09 .38 .21 1.00<br />

6. Depression 54.47 5.22 .31 .27 .09 .34 .20 1.00<br />

p < .05; p < .01.

22 Y. Gan et al.<br />

their homes and belongings. An independent t test indicated that the mean<br />

MFCQ score in the high-stress-exposure group (M ¼ 59.55, SD ¼ 13.59) was<br />

higher than that <strong>of</strong> the low-stress-exposure group (M ¼ 56.09, SD ¼ 13.43),<br />

t(334) ¼ 2.09, p < .05.<br />

The means, standard deviations, and Pearson correlation coefficients for<br />

the meaning-focused coping scores, posttraumatic growth scores, well-being<br />

scores, depression subscale scores, and positive and negative affect scores<br />

are shown in Table 5. The meaning-focused coping scores were positively<br />

related to the posttraumatic growth, well-being, and positive affect scores,<br />

whereas they were negatively related to the depression scores.<br />

Downloaded by [Peking University], [Yiqun Gan] at 20:16 22 December 2012<br />

DISCUSSION<br />

A 26-item instrument was developed, and it was verified that the MFCQ<br />

exhibited adequate psychometric properties, as evidenced by the results<br />

across the two samples that were included in the present study. The underlying<br />

eight dimensions <strong>of</strong> the MFCQ were identified in Sample 2 and validated<br />

based on the acceptable fit statistics derived using Sample 3. The<br />

traumatic events that were experienced by the participants in Sample 2 were<br />

unique to each individual, whereas all <strong>of</strong> the participants in Sample 3 had<br />

experienced the same earthquake. This difference between the types <strong>of</strong> participants<br />

in the different samples allowed us to cross-validate the reliability <strong>of</strong><br />

the questionnaire.<br />

Although the eight dimensions <strong>of</strong> our MFCQ can be summed to derive a<br />

total MFCQ score, the correlation results suggested that each dimension had<br />

a different function. For example, factor analyses generated factors that<br />

included ‘‘changes in situational meaning’’ and ‘‘changes in global meaning,’’<br />

as we expected. Moreover, changes in situational meaning were found to be<br />

better predictors <strong>of</strong> psychological adjustment than were changes in global<br />

meaning, which is also consistent with our initial hypothesis. This result<br />

has important implications for clinical practice. Intervention programs should<br />

facilitate changes in situational meanings to encourage better personal<br />

adjustment.<br />

The correlations among the MFCQ dimensions were low in magnitude,<br />

as expected. The eight dimensions <strong>of</strong> the MFCQ were essentially the same as<br />

the seven dimensions that we expected would be included prior to composing<br />

the questionnaire. In addition to the predicted seven dimensions, values<br />

and outlook on life emerged as an eighth dimension.<br />

The differences among the MFCQ scores in the high-stress-exposure<br />

group further strengthen the validity <strong>of</strong> the criteria used and indicate the<br />

sensitivity <strong>of</strong> the new instrument. The more stress an individual has to<br />

face, the more effort she or he will invest in developing and employing

<strong>Meaning</strong>-<strong>Focused</strong> <strong>Coping</strong> 23<br />

Downloaded by [Peking University], [Yiqun Gan] at 20:16 22 December 2012<br />

meaning-focused coping strategies. This result also validated a previous<br />

suggestion that the positive function <strong>of</strong> MFC only manifests after traumatic<br />

and uncontrollable events (Moskowitz et al., 1996).<br />

This study used IRT to evaluate the project features, information functions,<br />

and item difficulty and discrimination. On one level, the IRT analysis<br />

confirmed the results <strong>of</strong> the CTT-based analysis; however, it also revealed<br />

some limitations <strong>of</strong> our questionnaire.<br />

The participants in all three <strong>of</strong> the samples were adolescents who were<br />

between 14 and 20 years old. Based on the definition <strong>of</strong> MFC, it is clear that<br />

two processes were involved in their coping strategies: the process <strong>of</strong> changing<br />

the global meaning associated with the world and that <strong>of</strong> changing the<br />

situational meaning associated with a specific set <strong>of</strong> events. These two processes<br />

can be referred to as assimilation and adaptation. According to Piaget<br />

(1972), in completing their cognitive development and developing their<br />

logical thinking skills, adolescents enter a formal operational period that is<br />

critical to assimilation and adaptation. The adolescent earthquake survivors<br />

were in the midst <strong>of</strong> their cognitive development and resource accumulation<br />

processes. Given the focus on cognitive adaptation in this study and that<br />

meaning-focused coping skills (e.g., positive reappraisal and acceptance <strong>of</strong><br />

responsibility) develop in tandem with the cognitive development <strong>of</strong> adolescents,<br />

these skills should be more salient and differentiated as individuals<br />

grow older (Folkman, Lazarus, Pimley, & Novacek, 1987). However, this supposition<br />

also implies that our findings could to some extent be generalized to<br />

older, more experienced, and more mature populations. Thus, developing an<br />

MFC questionnaire for adolescents who are facing traumatic events has<br />

significant research and clinical implications.<br />

Previous research has shown that MFC is a long-term process, which<br />

makes it different from other types <strong>of</strong> coping. First, as Folkman (2007) noted,<br />

we need to understand the coping process <strong>of</strong> reevaluating stress, especially<br />

ins<strong>of</strong>ar as it results in the assignment <strong>of</strong> positive value to a situation. Second,<br />

we need to understand how MFC functions in different stages <strong>of</strong> the coping<br />

process. Third, the questionnaire should reflect the need to assess the effects<br />

<strong>of</strong> clinical interventions. We developed this questionnaire with these aims in<br />

mind.<br />

IRT has contributed significantly to the development <strong>of</strong> our questionnaire.<br />

First, we found that the degree <strong>of</strong> differentiation <strong>of</strong> all <strong>of</strong> the included<br />

items was large; in addition, except in the case <strong>of</strong> item 43, the project location<br />

b1 tob4 values for each item were beyond the standard range. Second, the<br />

test information function value was only a low-to-moderate 15. According to<br />

Qi, Dai, and Ding (2009), the test standard deviation should be less than or<br />

equal to 0.20. The test standard deviation is exactly equal to the inverse<br />

square <strong>of</strong> the test information function (SE(h) ¼ [I (h)] 1=2 ), which indicates<br />

that the value <strong>of</strong> the test information function should be at least 25. However,<br />

the relatively small number <strong>of</strong> test items in the present study made the

24 Y. Gan et al.<br />

Downloaded by [Peking University], [Yiqun Gan] at 20:16 22 December 2012<br />

requirements for each information item quite demanding. The information<br />

function value for each item was required to be at least 0.96, which is a difficult<br />

value to attain. Therefore, in follow-up studies, we should increase the<br />

number <strong>of</strong> items to improve the quality <strong>of</strong> this questionnaire.<br />

Finally, most <strong>of</strong> the subscale values and test information functions across<br />

the distribution did not appear to be skewed toward either the high-capacity<br />

test subjects or the low-ability participants, which indicates that the test is<br />

suitable for the general population. Compared with classical test theory,<br />

IRT better helps us to understand whether a project exhibits the appropriate<br />

psychometric properties and is suitable to the capability requirements <strong>of</strong> the<br />

participants.<br />

The present study is a preliminary attempt to develop an instrument for<br />

measuring meaning-focused coping skills and distinguishing between the<br />

different adjustment outcomes that result from changes in situational beliefs<br />

and changes in global beliefs. In composing the questionnaire, we combined<br />

the methodologies <strong>of</strong> classical test theory with those <strong>of</strong> modern test theory.<br />

This is a unique factor that contributes to the value <strong>of</strong> the present work.<br />

Further research that examines the way in which meaning-focused coping<br />

mechanisms protected the mental health <strong>of</strong> individuals who experienced<br />

trauma over a long-term adaptation period could also provide evidence <strong>of</strong><br />

the validity <strong>of</strong> the MFCQ.<br />

The present study has several limitations that should be noted. First,<br />

because all <strong>of</strong> the included variables were assessed using self-reported data,<br />

common method variance may explain some <strong>of</strong> the observed relationships<br />

between the meaning-focused coping and other constructs, making our findings<br />

misleading. Following the recommendations <strong>of</strong> Podsak<strong>of</strong>f, MacKenzie,<br />

Lee, and Podsak<strong>of</strong>f (2003) regarding the control and assessment <strong>of</strong> common<br />

method variance, we used different scale endpoints and formats for the<br />

predictor and criterion measures to address this issue. In Study 2, Harman<br />

one-factor tests were also conducted as a statistical remedy. The results<br />

showed that the first factor in our factor analysis only accounted for<br />

15.61% <strong>of</strong> the total variance, which suggests that common method variance<br />

was not a significant problem in our study.<br />

Second, we used a cross-sectional design to test convergent validity, as<br />

is appropriate in psychometric studies. However, it would be useful to<br />

include external criteria in the longitudinal data in future studies to<br />

examine whether the MFCS could predict the degree to which an individual<br />

will be able to adjust after a traumatic event or prevent the reoccurrence<br />

<strong>of</strong> such events. Future research that uses a longitudinal design should<br />

also further examine the three major coping styles and their mechanisms<br />

during long-term adaptation and during different stages. The effects <strong>of</strong><br />

these coping styles on positive and negative mental health outcomes,<br />

along with the effects <strong>of</strong> different types <strong>of</strong> stressors, should be further<br />

examined.

<strong>Meaning</strong>-<strong>Focused</strong> <strong>Coping</strong> 25<br />

REFERENCES<br />

Downloaded by [Peking University], [Yiqun Gan] at 20:16 22 December 2012<br />

Affleck, G., Tennen, H., Croog, S., & Levine, S. (1987). Causal attribution, perceived<br />

benefits, and morbidity following a heart attack: An 8-year study. Journal <strong>of</strong><br />

Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55, 29–35.<br />

Andrew, C., & Petrides, K. V. (2010). A psychometric analysis <strong>of</strong> the Trait Emotional<br />

Intelligence Questionnaire-Short Form (TEIQue-SF) using item response theory.<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> Personality Assessment, 92, 449–457.<br />

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., & Rodgers, W. L. (1976). The quality <strong>of</strong> American life:<br />

Perceptions, evaluations, and satisfactions. New York: Russell Sage.<br />

Carver, C. S. (1997). You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long:<br />

Consider the Brief COPE. International Journal <strong>of</strong> Behavioral Medicine, 4, 100.<br />

Collins, R. L., Taylor, S. E., & Skokan, L. A. (1990). A better world or a shattered<br />

vision? Changes in life perspectives following victimization. Social Cognition,<br />

8, 263–285.<br />

Dollinger, S. J. (1986). The need for meaning following disaster: Attributions and<br />

emotional upset. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 12, 300–310.<br />

Evers, A., Kraaimaat, F., van Lankveld, W., Jongen, P., Jacobs, J., & Bijlsma, J. (2001).<br />

Beyond unfavorable thinking: The Illness Cognition Questionnaire for chronic<br />

diseases. Journal <strong>of</strong> Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69, 1026–1036.<br />

Folkman, S. (2007). Positive affect and meaning-focused coping during significant<br />

psychological stress. In M. Hewstone, H. Schut, J. de Wit, K. van den Bos, &<br />

M. Stroebe (Eds.), The scope <strong>of</strong> social psychology: Theory and application<br />

(pp. 193–208). New York, NY: Psychology Press.<br />

Folkman, S. (2009). Questions, answers, issues, and next steps in stress and coping<br />

research. European Psychologist, 14, 72–77.<br />

Folkman, S., Lazarus, R. S., Pimley, S., & Novacek, J. (1987). Age differences in stress<br />

and coping processes. Psychology and Aging, 2, 171–184.<br />

Frazier, P. A., & Schauben, L. J. (1994). Causal attributions and recovery from rape<br />

and other stressful life events. Journal <strong>of</strong> Social and Clinical Psychology, 13,<br />

1–14.<br />

Golafshani, N. (2003). Understanding reliability and credibility in qualitative<br />

research. Qualitative Report, 8, 597–607.<br />

Holahan, C. J., Moos, R. H., Holahan, C. K., & Brennan, P. L. (1995). Social support,<br />

coping, and depressive symptoms in a late-middle-aged sample <strong>of</strong> patients<br />

reporting cardiac illness. Health Psychology, 14, 152–163.<br />

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cut<strong>of</strong>f criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure<br />

analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation<br />

Modeling, 6, 1–55.<br />

Marshall, M. N. (1996). Sampling for qualitative research. Family Practice, 3,<br />

522–525.<br />

Moskowitz, J. T., Folkman, S., Collette, L., & Vittingh<strong>of</strong>f, E. (1996). <strong>Coping</strong> and mood<br />

during AIDS-related caregiving and bereavement. Annals <strong>of</strong> Behavioral<br />

Medicine, 18, 49–57.<br />

Park, C. L., & Folkman, S. (1997). <strong>Meaning</strong> in the context <strong>of</strong> stress and coping.<br />

General Review <strong>of</strong> Psychology, 1, 115–144.

26 Y. Gan et al.<br />

Downloaded by [Peking University], [Yiqun Gan] at 20:16 22 December 2012<br />

Pearlin, L. I. (1991). The study <strong>of</strong> coping: An overview <strong>of</strong> problems and directions. In<br />

J. Eckenrode (Ed.), The social context <strong>of</strong> coping (pp. 261–276). New York, NY:<br />

Plenum.<br />

Piaget, J. (1972). Intellectual evolution from adolescence to adulthood. Human<br />

<strong>Development</strong>, 15, 1–12.<br />

Podsak<strong>of</strong>f, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsak<strong>of</strong>f, N. P. (2003). Common<br />

method biases in behavioral research: A critical review <strong>of</strong> the literature and<br />

recommended remedies. Journal <strong>of</strong> Applied Psychology, 88, 879–903.<br />

Qi, S., Dai, H., & Ding, S. (2009). Handbook <strong>of</strong> modern principles <strong>of</strong> educational and<br />

psychological measurement. Beijing, China: High Education Press.<br />

Roberts, K. J., Lepore, S. J., & Helgeson, V. S. (2006). Social-cognitive correlates <strong>of</strong><br />

adjustment to prostate cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 15, 183–192.<br />

Schwarzer, R., & Knoll, N. (2003). Positive coping: Mastering demands and searching<br />

for meaning. In S. J. Lopez, & C. R. Snyder (Eds.), Positive psychological assessment:<br />

A handbook <strong>of</strong> models and measures (pp. 393–409). Washington, DC:<br />

American Psychological Association.<br />

Stanton, A., Dan<strong>of</strong>f-Burg, S., & Huggins, M. (2002). The first year after breast cancer<br />

diagnosis: Hope and coping strategies as predictors <strong>of</strong> adjustment. Psycho-<br />

Oncology, 11, 93–102.<br />

Thissen, D., & Steinberg, L. (2009). Item response theory. In R. Millsap, & A.<br />

Maydeu-Olivares (Eds.), The Sage handbook <strong>of</strong> quantitative methods in<br />

psychology (pp. 148–177). London, England: Sage.<br />

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). <strong>Development</strong> and validation <strong>of</strong> brief<br />

measures <strong>of</strong> positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal <strong>of</strong><br />

Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063–1070.<br />

Xie, X., Liu, H., & Gan, Y. (2011). Belief in a just world when encountering the 5=12<br />

Wenchuan earthquake. Environment and Behavior, 43, 566–586.<br />

Zhang, B., Wang, X., & Sun, H. (2001). A study on the prevalence <strong>of</strong> neurosis and its<br />

cause over 20 years after the violent earthquake in Tangshan. Nervous Disease<br />

and Mental Health, 1, 6–10.<br />

Zhang, M. Y. (1993). Ranking scales for mental health. New York, NY: Human<br />

Science Press.<br />

Zung, W. W. K., Durham, N. C, Richards, C. B., Gables, C, & Short, M. J. (1965). A<br />

self-rating depression scale. Archives <strong>of</strong> General Psychiatry, 12, 63–70.<br />

Yiqun Gan is a pr<strong>of</strong>essor at the Department <strong>of</strong> Psychology, Peking University, China.<br />

She received her PhD from the Chinese University <strong>of</strong> Hong Kong in 1998. She has published<br />

over 60 research papers, 16 in internationally refereed journals (indexed by SSCI)<br />

as the first or corresponding author. Her research areas focus on coping, mental health,<br />

and job burnout.<br />

Mingzhu Guo is a master’s student in the Department <strong>of</strong> Psychology, Peking<br />

University.<br />

Jing Tong is a master’s student in the Department <strong>of</strong> Psychology, Peking University.