Preventing Suicide - SPINZ

Preventing Suicide - SPINZ

Preventing Suicide - SPINZ

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

S u i c i d e P r e v e n t i o n I n f o r m a t i o n N e w Z e a l a n d<br />

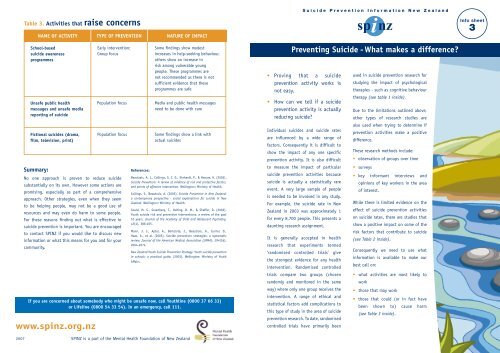

Table 3. Activities that raise concerns<br />

NAME OF ACTIVITY TYPE OF PREVENTION NATURE OF IMPACT<br />

Info sheet<br />

3<br />

School-based<br />

suicide awareness<br />

programmes<br />

Unsafe public health<br />

messages and unsafe media<br />

reporting of suicide<br />

Fictional suicides (drama,<br />

film, television, print)<br />

Summary:<br />

No one approach is proven to reduce suicide<br />

substantially on its own. However some actions are<br />

promising, especially as part of a comprehensive<br />

approach. Other strategies, even when they seem<br />

to be helping people, may not be a good use of<br />

resources and may even do harm to some people.<br />

For these reasons finding out what is effective in<br />

suicide prevention is important. You are encouraged<br />

to contact <strong>SPINZ</strong> if you would like to discuss new<br />

information or what this means for you and for your<br />

community.<br />

Early intervention;<br />

Group focus<br />

Population focus<br />

Population focus<br />

References:<br />

Beautrais, A. L., Collings, S. C. D., Ehrhardt, P., & Henare, K. (2005).<br />

<strong>Suicide</strong> Prevention: A review of evidence of risk and protective factors,<br />

and points of effective intervention. Wellington: Ministry of Health.<br />

Collings, S., Beautrais, A. (2005). <strong>Suicide</strong> Prevention in New Zealand:<br />

a contemporary perspective - social explanations for suicide in New<br />

Zealand. Wellington: Ministry of Health.<br />

Gould, M. S., Greenberg, T., Velting, D. M., & Shaffer, D. (2003).<br />

Youth suicide risk and preventive interventions: a review of the past<br />

10 years. Journal of the Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry,<br />

42(4), 386-405.<br />

Mann, J. J., Apter, A., Bertolote, J., Beautrais, A., Currier, D.,<br />

Haas, A., et al. (2005). <strong>Suicide</strong> prevention strategies: a systematic<br />

review. Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), 294(16),<br />

2064-2074.<br />

New Zealand Youth <strong>Suicide</strong> Prevention Strategy: Youth suicide prevention<br />

in schools: a practical guide. (2003). Wellington: Ministry of Youth<br />

Affairs.<br />

Some findings show modest<br />

increases in help-seeking behaviour,<br />

others show an increase in<br />

risk among vulnerable young<br />

people. These programmes are<br />

not recommended as there is not<br />

sufficient evidence that these<br />

programmes are safe<br />

Media and public health messages<br />

need to be done with care<br />

Some findings show a link with<br />

actual suicides<br />

If you are concerned about somebody who might be unsafe now, call Youthline (0800 37 66 33)<br />

or Lifeline (0800 54 33 54). In an emergency, call 111.<br />

www.spinz.org.nz<br />

<strong>Preventing</strong> <strong>Suicide</strong> - What makes a difference?<br />

• Proving that a suicide<br />

prevention activity works is<br />

not easy.<br />

• How can we tell if a suicide<br />

prevention activity is actually<br />

reducing suicide?<br />

Individual suicides and suicide rates<br />

are influenced by a wide range of<br />

factors. Consequently it is difficult to<br />

show the impact of any one specific<br />

prevention activity. It is also difficult<br />

to measure the impact of particular<br />

suicide prevention activities because<br />

suicide is actually a statistically rare<br />

event. A very large sample of people<br />

is needed to be involved in any study.<br />

For example, the suicide rate in New<br />

Zealand in 2003 was approximately 1<br />

for every 8,700 people. This presents a<br />

daunting research assignment.<br />

It is generally accepted in health<br />

research that experiments termed<br />

‘randomised controlled trials’ give<br />

the strongest evidence for any health<br />

intervention. Randomised controlled<br />

trials compare two groups (chosen<br />

randomly and monitored in the same<br />

way) where only one group receives the<br />

intervention. A range of ethical and<br />

statistical factors add complications to<br />

this type of study in the area of suicide<br />

prevention research. To date, randomised<br />

controlled trials have primarily been<br />

used in suicide prevention research for<br />

studying the impact of psychological<br />

therapies - such as cognitive behaviour<br />

therapy (see table 1 inside).<br />

Due to the limitations outlined above,<br />

other types of research studies are<br />

also used when trying to determine if<br />

prevention activities make a positive<br />

difference.<br />

These research methods include:<br />

• observation of groups over time<br />

• surveys<br />

• key informant interviews and<br />

opinions of key workers in the area<br />

of interest.<br />

While there is limited evidence on the<br />

effect of suicide prevention activities<br />

on suicide rates, there are studies that<br />

show a positive impact on some of the<br />

risk factors that contribute to suicide<br />

(see Table 2 inside).<br />

Consequently we need to use what<br />

information is available to make our<br />

best call on:<br />

• what activities are most likely to<br />

work<br />

• those that may work<br />

• those that could (or in fact have<br />

been shown to) cause harm<br />

(see Table 3 inside).<br />

2007 <strong>SPINZ</strong> is a part of the Mental Health Foundation of New Zealand

A programme is most likely to be safe and make a positive difference if it is aligned with research evidence<br />

that shows this type of activity is effective. This is an important consideration with suicide prevention<br />

because of the potential to do harm.<br />

<strong>SPINZ</strong> has used the evidence from recent extensive reviews of the research literature to compile a summary<br />

of what the international evidence shows us as at January 2006.<br />

Note on Tables: Activities / interventions generally fit along a continuum from promoting<br />

wellbeing and healthy development to early identification through to clinical services.<br />

Activities / interventions are aimed at individuals, groups, or whole populations.<br />

Table 2. Activities which have some evidence of effectiveness<br />

Population Focus<br />

NAME OF ACTIVITY TYPE OF PREVENTION NATURE OF IMPACT<br />

Media education and guidelines Reducing risk Can limit suicide contagion (e.g. copycat<br />

suicides)<br />

Public awareness of depression/mental<br />

health literacy (e.g. destigmatisation of<br />

mental illness, depression recognition<br />

programmes)<br />

Promoting wellbeing<br />

May increase help-seeking<br />

Improving the control of alcohol Reducing risk May reduce problem alcohol use which is<br />

a risk factor for suicide<br />

Whanau, hapu, iwi, taitamariki<br />

development<br />

Promoting wellbeing<br />

Recognises international best practice<br />

and also subscribes to unique Maori<br />

values, processes and social institutions<br />

Telephone hotlines and crisis centres Early identification Some impact on risk factors<br />

Table 1. Activities with good evidence of effectiveness<br />

NAME OF ACTIVITY<br />

Psychological therapies<br />

(e.g. Cognitive Behavioural<br />

Therapy, Problem Solving<br />

Therapy, Dialectic Behavioural<br />

Therapy, Interpersonal<br />

Psychotherapy)<br />

Restriction of access to<br />

means (e.g. control of<br />

guns and toxic substances,<br />

removing hanging points<br />

in prisons or mental health<br />

inpatient units)<br />

TYPE OF PREVENTION<br />

Clinical services;<br />

Individual focus<br />

Reducing risk;<br />

Population focus<br />

NATURE OF IMPACT<br />

Reduction in depression and<br />

some reductions in suicidal<br />

behaviour among specific<br />

high risk groups<br />

Reduction in suicide<br />

attempts using that means<br />

and sometimes reduction in<br />

total suicides<br />

Group Focus<br />

Internet/computer based tools Promoting wellbeing May improve help-seeking skills<br />

Interventions which strengthen families<br />

and individuals (e.g. decreasing family<br />

violence, child abuse, improving opportunities,<br />

improving problem solving & social skills,<br />

building resiliency or protective factors)<br />

Skills training (e.g. improving individuals or<br />

groups problem solving and coping skills)<br />

Targeted programmes (e.g. programmes<br />

that target substance abuse, depressive<br />

symptoms, anxiety & conduct disorders)<br />

Befriending, mentoring or volunteer<br />

support programmes<br />

Screening programmes - screening young<br />

people or groups who are at increased risk<br />

(such as those in social welfare care) for<br />

depression or suicide risk<br />

Reducing risk;<br />

Promoting wellbeing<br />

Promoting wellbeing<br />

Early identification;<br />

Reducing risk<br />

Early intervention<br />

Early identification<br />

This may limit risk factors or the impact<br />

of risk factors<br />

Some reduction in risk factors<br />

Often some improvement regarding<br />

targeted risk factor<br />

Where the programmes are well run there<br />

can be some impact on risk factors<br />

Can identify high-risk individuals. Needs<br />

to be a quality screening programme,<br />

with follow up for those who need it<br />

Postvention (support after a suicide) Reducing risk May decrease depressive symptoms<br />

amongst bereaved family. Addresses<br />

potential risks within affected people<br />

Education of doctors and<br />

other health professionals<br />

in recognition and treatment<br />

of depression<br />

Gatekeeper training (e.g.<br />

training of caregivers,<br />

military or prison personnel,<br />

school staff, pastors or others<br />

in recognising warning signs,<br />

getting assessment and<br />

treatment)<br />

Early identification<br />

Early identification<br />

Increases recognition and<br />

treatment of depression with<br />

some reductions in suicide<br />

Where gatekeepers are able<br />

to identify risk and facilitate<br />

access to treatment this<br />

can be effective and is a<br />

promising strategy to reduce<br />

suicide<br />

Individual Focus<br />

Co-ordinated follow up programmes<br />

Programmes which focus on pro-active,<br />

regular, co-ordinated follow-up of people<br />

who are at increased risk, e.g. managed care,<br />

collaborative case management or wrap around<br />

programmes for those with depression, those<br />

whom have attempted suicide, or who have<br />

recently been discharged from psychiatric care<br />

Primary health care and mental health<br />

care - programmes that make it easier for<br />

people to access or use primary health care<br />

or mental health care; provide training for<br />

staff and implement systems for recognising<br />

and treating depression and other mental<br />

health problems and assessing & managing<br />

suicide risk<br />

Clinical<br />

Clinical<br />

Can monitor and address current suicidal<br />

risk & promote wellbeing; likely to be an<br />

important strategy in reducing suicides<br />

Increase opportunity for early detection<br />

and management of suicide risk factors;<br />

likely to be an important strategy in<br />

reducing suicide<br />

Psychopharmacological interventions<br />

(e.g. medications for depression and other<br />

specific mental illnesses)<br />

Clinical<br />

Effective in treating the specific<br />

disorders, this may be an important<br />

strategy for reducing suicide