Untitled - Issues of Image Magazine - George Eastman House

Untitled - Issues of Image Magazine - George Eastman House

Untitled - Issues of Image Magazine - George Eastman House

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Image</strong> Vol. 19, No. 2 June, 1976<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> Photography and Motion Pictures <strong>of</strong> the International Museum <strong>of</strong> Photography at <strong>George</strong> <strong>Eastman</strong> <strong>House</strong><br />

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

Anton Bruehl 1<br />

Stieglitz, 291, and Paul Strand's Early Photography 10<br />

Rediscovering Gertrude Kasebier 20<br />

Review 32<br />

IMAGE STAFF<br />

Robert J. Doherty, Director<br />

<strong>George</strong> C. Pratt, Director <strong>of</strong> Publications<br />

W. Paul Rayner, Guest Editor<br />

Contributing Editors:<br />

James Card, Director, Department <strong>of</strong> Film<br />

Andrew Eskind, Assistant to the Director <strong>of</strong> the Museum<br />

Robert A. Sobieszek, Associate Curator, 19th Century Photography<br />

Philip L. Condax, Assistant Curator, Equipment Archive<br />

William Jenkins, Assistant Curator, 20th Century Photography<br />

Marshall Deutelbaum, Curatorial Assistant, Department <strong>of</strong> Film<br />

Ann McCabe, Registrar<br />

Walter Clark, Consultant on Conservation<br />

Rudolf Kingslake, Consultant on Lenses and Shutters<br />

Eaton S. Lothrop, Jr., Consultant on Cameras<br />

Martin L. Scott, Consultant on Technology<br />

Martha Jenks, Director <strong>of</strong> Archives<br />

Joe Deal, Exhibitions<br />

Corporate Members<br />

Berkey Marketing Companies, Inc.<br />

Braun <strong>of</strong> North America, Inc.<br />

<strong>Eastman</strong> Kodak Company<br />

Flanigans Furniture<br />

Gannett Newspapers<br />

Hollinger Corporation<br />

Polaroid Corporation<br />

Spectrum Office Products<br />

Spiratone, Inc.<br />

3M Company<br />

<strong>Image</strong> is published four times a year for the International Museum <strong>of</strong> Photography Associate Members and libraries by<br />

International Museum <strong>of</strong> Photography at <strong>George</strong> <strong>Eastman</strong> <strong>House</strong> Inc., 900 East Avenue, Rochester, New York 14607<br />

Single copies are available at $2.25 each. Subscriptions are available to libraries at $10.00 per year (4 issues). For oversea!<br />

libraries add $1.00.<br />

Copyright 1976 by International Museum <strong>of</strong> Photography at <strong>George</strong> <strong>Eastman</strong> <strong>House</strong> Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A.<br />

BOARD OF TRUSTEES<br />

Chairman, Vincent S. Jones<br />

First Vice Chairman, Wesley T. Hanson<br />

Second Vice Chairman, Alexander D. Hargrave<br />

Treasurer, Robert Sherman<br />

Secretary, Mrs. Arthur L. Stern III<br />

Robert Doherty<br />

Walter A. Fallon<br />

Sherman Farnham<br />

Frank M. Hutchins<br />

Mrs. Daniel G. Kennedy<br />

William E. Lee<br />

David L. Strout<br />

W. Allen Wallis<br />

Frederic S. Welsh<br />

Andrew D. Wolfe<br />

About the Contributors<br />

Joe Deal is on the staff <strong>of</strong> IMP/GEH. William<br />

Innes Homer is Chairman <strong>of</strong> the Art History Department<br />

at the University <strong>of</strong> Delaware. Barbara<br />

L. Michaels teaches History <strong>of</strong> Photography at<br />

New York University. She has also been Assistant<br />

Curator <strong>of</strong> the Atget Collection at The<br />

Museum <strong>of</strong> Modern Art, New York.<br />

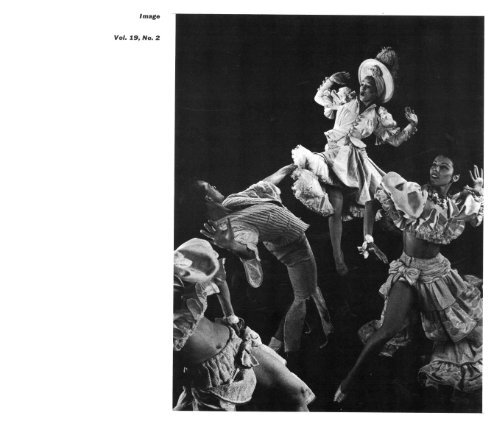

Front Cover: Anton Bruehl. <strong>Untitled</strong> and undated. From a<br />

dye transfer print. Back Cover: Bruehl. Charles Laughton,<br />

1933.<br />

Unless otherwise attributed, photographs are from the<br />

IMP/GEH Collections. Negative numbers refer to the<br />

IMP/GEH Print Service files.

Anton<br />

Joe Deal<br />

Bruehl<br />

During the height <strong>of</strong> his career, which extended<br />

from the late '20s through the '30s, Anton Bruehl<br />

enjoyed a reputation among other photographers<br />

and the public which few photographers<br />

have been able to achieve. His photographs appeared<br />

regularly in the pages <strong>of</strong> Vogue, Vanity<br />

Fair and numerous other publications. His efforts<br />

to raise the standards <strong>of</strong> photography in<br />

advertising earned him two Harvard Awards<br />

and eight Gold Medals from the Art Director's<br />

Club.<br />

In 1929 his photographs were included in the<br />

"Film und Foto" exhibition in Stuttgart; again<br />

almost a decade later they appeared in the History<br />

<strong>of</strong> Photography exhibition at the Museum<br />

<strong>of</strong> Modern Art and "Trois Siecles d'Art aux<br />

Etats-Unis" in Paris where he was one <strong>of</strong> fortytwo<br />

photographers selected by Beaumont Newhall<br />

to represent almost 100 years <strong>of</strong> American<br />

photography. Articles were written about Bruehl;<br />

his name was frequently cited in discussions <strong>of</strong><br />

modern photography as one <strong>of</strong> America's leaders,<br />

comparing his work in America to that <strong>of</strong><br />

Rodschenko in Russia and Hoyningen-Huene in<br />

Paris. 1 His photographs are exemplary <strong>of</strong> an internationally<br />

spirited phase in the history <strong>of</strong><br />

photography which has since been largely ignored.<br />

Anton Bruehl was born in Australia in 1900 to<br />

German parents. In Australia he studied engineering<br />

and later came to America where he<br />

worked in New York for Western Electric Company.<br />

In 1924 after visiting an exhibition <strong>of</strong><br />

photographs by students <strong>of</strong> the Clarence White<br />

School he gave up his career in engineering to<br />

study photography with White. After only six<br />

months <strong>of</strong> private lessons with White, during<br />

which time he also worked in the portrait studio<br />

<strong>of</strong> Jessie Tarbox Beals, Bruehl was asked to<br />

help teach at the White School. 2 The warm relationship<br />

which developed between Bruehl and<br />

Clarence White ended in the summer <strong>of</strong> 1925<br />

when, on a trip to Mexico with some <strong>of</strong> his students,<br />

White died <strong>of</strong> a heart attack.<br />

Bruehl ran the summer school that year, and<br />

in 1926 entered the pr<strong>of</strong>ession <strong>of</strong> advertising<br />

photography. He maintained his membership in<br />

the Pictorial Photographers <strong>of</strong> America, an organization<br />

made up mostly <strong>of</strong> former students<br />

<strong>of</strong> the White School, and eventually became a<br />

member <strong>of</strong> its executive committee and jury for<br />

the annual exhibitions held at the New York Art<br />

Center. By 1929, along with photographers such<br />

as Paul Outerbridge and Ralph Steiner, Bruehl<br />

contributed to the transformation <strong>of</strong> the content<br />

and appearance <strong>of</strong> the annual exhibitions to the<br />

extent that Frank Crowninshield, editor <strong>of</strong> Vanity<br />

Fair, was moved to comment in the foreword to<br />

the 1929 Annual <strong>of</strong> the Pictorial Photographers<br />

<strong>of</strong> America: 3<br />

And the inevitable result <strong>of</strong> this encroachment<br />

<strong>of</strong> modernism has been that<br />

the old-time quality <strong>of</strong> "sentimentality" is<br />

very much on the decline in our photographic<br />

art. The once popular "storytelling"<br />

pictures, the tender landscapes<br />

with sheep, the bowls <strong>of</strong> flowers, the portraits<br />

<strong>of</strong> little children, have had to make<br />

way for prints in which a new and almost<br />

disordered spirit is evident. The gospel <strong>of</strong><br />

mass and the age <strong>of</strong> machinery have certainly<br />

been making converts among the<br />

American photographers.<br />

If, as is generally agreed, the twentieth century<br />

was accepted late by the Pictorialists who<br />

held closely to pre-war sentiments, it is seldom<br />

acknowledged that Clarence White and the Pictorialist<br />

movement provided a new generation<br />

with the leaders <strong>of</strong> a widespread phenomenon<br />

in American photography commonly referred to<br />

as "Modern photography." Anton Bruehl's background<br />

in engineering and love <strong>of</strong> machine<br />

forms in combination with his training under<br />

Clarence White resulted in still life photographs<br />

which give the satisfaction <strong>of</strong> well-resolved formal<br />

problems and portraits choreographed with<br />

the rhythm and movement characteristic <strong>of</strong> the<br />

age.<br />

During the '30s Bruehl's studio expanded,<br />

eventually becoming one <strong>of</strong> the most successful<br />

in New York. In 1933 he made a trip to Mexico<br />

where he shot a series <strong>of</strong> photographs similar<br />

in many ways to Paul Strand's Mexican photographs<br />

made the same year but not published<br />

until 1940 as The Mexican Portfolio. Bruehl's<br />

1

Mexican photographs had in the meantime<br />

been exhibited at the Delphic Galleries in 1933<br />

and published the same year in a book, Mexico,<br />

which was given an award as the best example<br />

<strong>of</strong> book illustration by the American Institute <strong>of</strong><br />

Graphic Arts for the years 1931-33. Jose Clemente<br />

Orozco, the Mexican painter, wrote about<br />

Bruehl's Mexico:<br />

The first word that comes to mind on<br />

seeing these photographs is magnificent.<br />

Anything that may be expected from the art<br />

<strong>of</strong> painting is there; perfection <strong>of</strong> craftsmanship—perfection<br />

<strong>of</strong> plastic organization.<br />

And this is certainly Mexico as revealed<br />

by great photography. The strong<br />

2<br />

and unique individuality <strong>of</strong> a people —<br />

mysterious mixture <strong>of</strong> the most simple and<br />

primitive with the highest refinement and<br />

unaffected, natural good taste.<br />

How many painters have tried to reproduce<br />

those faces, those scenes, those<br />

rhythmic movements. All in vain. The subject<br />

is so powerful and complete in itself<br />

that it would take an effort as powerful<br />

merely to reproduce it. Mr. Bruehl's work<br />

is more than reproduction. 4<br />

Paul Strand's photographs for The Mexican<br />

Portfolio developed into a greater body <strong>of</strong> work<br />

extending the possibilities <strong>of</strong> photography in<br />

portraying people <strong>of</strong> various nations or regions<br />

<strong>of</strong> the world. But Bruehl never returned to this<br />

use <strong>of</strong> photography for which he had demonstrated<br />

his talents so well in Mexico; the book<br />

remains however a strong, and elegant demonstration<br />

<strong>of</strong> the possibilities <strong>of</strong> this genre.<br />

Shortly before the publication <strong>of</strong> his Mexican<br />

photographs, Anton Bruehl began experimenting<br />

with color photography, at a time when<br />

many other photographers and photo-technicians<br />

were searching for a practical and effective<br />

method <strong>of</strong> producing color photographs for<br />

the printed page. In 1932 Fernand Bourges, a<br />

color technician working for Conde Nast Engravers,<br />

developed a process for creating a<br />

color transparency made <strong>of</strong> thin acetate sheets<br />

coated with light-sensitive emulsions which<br />

were dyed and sandwiched together with glass.<br />

Conde Nast Engravers used these extremely<br />

fine color transparencies as guides and, with<br />

hand work, made the printing plates in a painstaking<br />

process which resulted in some <strong>of</strong> the<br />

finest color reproductions ever made.<br />

Anton Bruehl was invited to become the chief<br />

color photographer for Conde Nast Publications<br />

working with Bourges under an agreement that<br />

all would collaborate in the production <strong>of</strong> any<br />

color photographs for advertisers which any <strong>of</strong><br />

the three (photographer, technician, or engravers)<br />

contracted for. The team <strong>of</strong> Bruehl-<br />

Bourges together with Conde Nast Engravers<br />

produced color photographs for the printed<br />

page which had, as an ad in Vogue claimed,<br />

"the compelling beauty <strong>of</strong> a painting and the<br />

fidelity <strong>of</strong> a blueprint" without much serious<br />

competition until the advent <strong>of</strong> Kodachrome in<br />

1935. Among the best <strong>of</strong> Bruehl's color work<br />

for Vogue and Vanity Fair are the photographs<br />

with rich shadow areas surrounding taut, vibrant<br />

arrangements <strong>of</strong> singers and dancers<br />

from New York night clubs and stage productions,<br />

such as the one reproduced in black and<br />

white on the cover.<br />

At their best, Bruehl's photographs are deliberate,<br />

non-anecdotal and carefully composed<br />

graphic representations, whether earlier semiabstract<br />

portraits and product photographs or<br />

later color portraits and human still-lifes. The<br />

constant flow through his studio <strong>of</strong> star personalities<br />

and products <strong>of</strong> the depressed but<br />

forward-looking economy may have occasionally<br />

resulted, as Bruehl feels, in somewhat less<br />

than enduring photographs. However, it unquestionably<br />

produced a revealing and evocative<br />

portrait <strong>of</strong> the popular aspirations <strong>of</strong> a culture,<br />

enabling Dr. M. F. Agha, art director for Vogue,<br />

to state in 1935, that, photography is "a perfect<br />

means <strong>of</strong> graphic expression for an artist who<br />

lives in the days <strong>of</strong> skyscrapers, engineers,<br />

saxophones and tap dancing. . . ." 5<br />

Notes<br />

1 Dr. M. F. Agha, "A Word on European Photography,"<br />

Pictorial Photography in America, vol. 5. (New York:<br />

Pictorial Photographers <strong>of</strong> America at the New York Art<br />

Center, 1929), n.p.<br />

2 From an unpublished interview with Anton Bruehl, July<br />

9, 10, 1975.<br />

3 Frank Crowninshield, "Foreword," Pictorial Photography<br />

in America, vol. 5 (New York: Pictorial Photographers <strong>of</strong><br />

America at the New York Art Center, 1929), n.p.<br />

4 Jose Clemente Orozco, from promotional material for:<br />

Anton Bruehl, Mexico, (New York: Delphic Studios, 1933).<br />

5 Dr. M. F. Agha, in preface to: T. J. Maloney, ed., U.S.<br />

Camera 1935, (New York: Morrow & Co., 1935), p. 4.<br />

Selected Bibliography<br />

Bruehl, Anton. Mexico. New York: Delphic Studios, 1933.<br />

. Tropic Patterns. Hollywood, Florida: Dukane<br />

Press, 1970.<br />

Bruehl, Anton, and Bourges, Fernand. Color Sells. New<br />

York: Conde Nast Publications, 1935.<br />

Bruehl, Anton and Lowell, Thomas. Magic Dials. New<br />

York: Lee Furman, 1939.<br />

Sipley, Louis Walton. "Color Grows During the Depression."<br />

A Half Century <strong>of</strong> Color. New York: MacMillan &<br />

Co., 1951.<br />

Bruehl, Anton. "Dietrich by Bruehl." Cinema Arts, September<br />

1937, pp. 51-57.<br />

. "I Don't Like the Photographic Press." Popular<br />

Photography, January 1938, p. 15.<br />

Kelly, Etna M. "Anton Bruehl, Master <strong>of</strong> Color." Photography,<br />

November 1936, p. 6.<br />

Maloney, Thomas J. "Photography Comes <strong>of</strong> Age."<br />

Review <strong>of</strong> Reviews and World's Work, June 1933, pp.<br />

19-23.<br />

"The Brothers Bruehl." U.S. Camera, March-April 1939,<br />

pp. 34-35.

Stieglitz, 291, and Paul Strand's Early Photography<br />

William Innes Homer<br />

Editor's<br />

Note<br />

The following two articles, "Stieglitz, 291, and<br />

Paul Strand's Early Photography" by William<br />

Innes Homer and "Rediscovering Gertrude<br />

Kasebier" by Barbara L. Michaels, are the first in<br />

a series <strong>of</strong> papers to be published in <strong>Image</strong>,<br />

drawn from a symposium titled, "The Art History<br />

<strong>of</strong> Photography: Recent Investigations,"<br />

sponsored by the International Museum <strong>of</strong> Photography<br />

at the <strong>George</strong> <strong>Eastman</strong> <strong>House</strong>, on February<br />

20 and 21, 1975.<br />

The participants <strong>of</strong> the symposium and their<br />

topics were as follows:<br />

Peter C. Bunnell (Princeton University)<br />

"The Early European Photographs <strong>of</strong> Alfred<br />

Stieglitz"<br />

William Innes Homer (University <strong>of</strong><br />

Delaware)<br />

"Stieglitz's Credo <strong>of</strong> Modernism: Its Manifestation<br />

in Paul Strand's Early Photographs"<br />

Eugenia Parry Janis (Wellesley College)<br />

"The Man on the Tower <strong>of</strong> Notre Dame:<br />

New Light on Henri LeSecq"<br />

Estelle Jussim (Simmons College)<br />

"The Syntax <strong>of</strong> Reality: Photography's<br />

Transformation <strong>of</strong> Nineteenth Century<br />

Wood-Engraving into an Art <strong>of</strong> Illusion"<br />

Ulrich Keller (University <strong>of</strong> Louisville)<br />

"Photographs in Context"<br />

Barbara L. Michaels (The Museum <strong>of</strong><br />

Modern Art, N.Y.)<br />

"Rediscovering Gertrude Kasebier"<br />

Anita Ventura Mozley (Stanford University)<br />

"Thomas Annan <strong>of</strong> Glasgow (1829-1887)"<br />

A number <strong>of</strong> the remaining papers will be<br />

published in forthcoming issues later this year.<br />

10<br />

In 1915, Paul Strand suddenly and unexpectedly<br />

appeared on the photographic scene in New<br />

York with a group <strong>of</strong> startlingly abstract images,<br />

in particular "Abstraction, Bowls" (1914-15)<br />

and "Abstraction, Porch Shadows" (1914-15) 1<br />

Prior to this moment, it is questionable whether<br />

there was any photographer in America or<br />

Europe who had gone this far in applying the<br />

lessons <strong>of</strong> abstract painting to photography.<br />

Later, Strand explained that, in executing<br />

these pictures, he "wanted to find out what this<br />

abstract idea was all about and to discover the<br />

principles behind it." He also said: "I did those<br />

photographs as part <strong>of</strong> that inquiry, the inquiry<br />

<strong>of</strong> a person into the meaning <strong>of</strong> this new development<br />

in painting. I did not have any idea<br />

<strong>of</strong> imitating painting or competing with it but<br />

was trying to find out what its value might be to<br />

someone who wanted to photograph the real<br />

world." 2<br />

Strand brought his experimental photographs<br />

to show Alfred Stieglitz in 1915. They so impressed<br />

Stieglitz that he <strong>of</strong>fered to publish them<br />

in his magazine Camera Work and to give<br />

Strand a one-man show at his gallery at 291<br />

Fifth Avenue. Having thus won Stieglitz's approval,<br />

Strand was immediately welcomed as a<br />

co-worker at 291. As the proprietor told him:<br />

"This is your place, too; come whenever you<br />

want, meet with the other people." Although<br />

Strand became a member <strong>of</strong> the inner circle<br />

<strong>of</strong> 291 late in the lifespan <strong>of</strong> that institution, he<br />

drew a great deal from the embers <strong>of</strong> creative<br />

vigor that continued to glow there from 1915<br />

to 1917. In the final years <strong>of</strong> 291, Stieglitz had<br />

become so discouraged by the lack <strong>of</strong> artistic<br />

vision among photographers that he had almost<br />

given up hope for any progress in the medium.<br />

When Strand appeared on the scene, seeming<br />

to understand what 291 really meant, Stieglitz's<br />

photographic interests blossomed once again.<br />

Strand promised a photographic renaissance;<br />

but like all rebirths in the arts, the pattern <strong>of</strong><br />

the past was not repeated exactly. He represented<br />

a modernized version <strong>of</strong> what the older<br />

Photo-Secession photographers once grouped<br />

around Stieglitz, like Clarence White and Gertrude<br />

Kasebier, had achieved. Strand was a<br />

master <strong>of</strong> his craft, and he applied principles<br />

<strong>of</strong> pictorial composition from the fine arts to<br />

his photographic images. But his visual sources<br />

were far more up-to-date, far more advanced for<br />

his time than the earlier Photo-Secessionists'<br />

artistic sources had been in theirs.<br />

This marriage <strong>of</strong> art and photography, in<br />

modern terms, is exactly what Stieglitz had<br />

been seeking since the early days <strong>of</strong> the Photo-<br />

Secession. At the beginning <strong>of</strong> that enterprise,<br />

he had favored Steichen as the person who best<br />

combined the aesthetics <strong>of</strong> art and photography,<br />

but Stieglitz had always harbored doubts<br />

about the fuzziness and romanticism <strong>of</strong> Steich

en's imagery. Strand, however, did not have<br />

these shortcomings. From 1915 on, Strand<br />

made precise, sharp-focus images, compatible<br />

with the "straight" approach that Stieglitz had<br />

advocated at that time. He also understood, it<br />

seems to me, much better than Steichen the<br />

lessons <strong>of</strong> European Cubism and abstraction.<br />

Learning much from the exhibitions <strong>of</strong> avantgarde<br />

art at 291 and the Armory Show in 1913,<br />

Strand, it could be argued, became the first<br />

photographer in history whose style was heavily<br />

influenced by modernist painting and sculpture.<br />

Paul Strand was born in New York City in<br />

1890, the only child <strong>of</strong> Jacob and Matilda<br />

Stransky (the family changed the name to<br />

Strand shortly before his birth). Strand grew up<br />

in the city, attending public schools until 1904,<br />

when he entered the Ethical Culture High<br />

School. It was there that he took a class in<br />

drawing, but, he recalled, he had "very little<br />

interest and little talent for it." More important<br />

for his artistic development was a class in art<br />

appreciation conducted by Charles H. Caffin,<br />

one <strong>of</strong> the most sensitive and advanced critics<br />

writing in America at that time. Caffin not only<br />

praised the abstractness <strong>of</strong> Whistler's paintings<br />

and Japanese art, he was also a perceptive<br />

critic <strong>of</strong> photography and in 1901 published<br />

Photography as a Fine Art, a pioneering book<br />

on pictorial photography. We do not know what<br />

exactly Strand derived from Caffin's course, but<br />

he remembers being impressed by the critic's<br />

wide knowledge, and it may be that Caffin's<br />

sympathy for abstraction influenced Strand's<br />

subsequent interest in that pictorial mode.<br />

Lewis Hine, another <strong>of</strong> the teachers at, the<br />

Ethical Culture School, introduced Strand to<br />

the discipline <strong>of</strong> photography. Later renowned<br />

for his moving documentary photographs <strong>of</strong><br />

immigrants, laborers, and slum dwellers, such<br />

as "Aged Negro Head, No. 1," Hine was an<br />

instructor in biology and served as a semi<strong>of</strong>ficial<br />

photographer for the school. In 1901,<br />

he had obtained permission to start a class<br />

called "nature study and photography," and it<br />

was there that Strand learned to take photographs<br />

and to develop and print them. Hine's<br />

greatest contribution, Strand recalled, was to<br />

take the class to Stieglitz's Photo-Secession<br />

Gallery at 291. There the students saw some<br />

<strong>of</strong> the finest available examples <strong>of</strong> pictorial<br />

photography, works by the English photographers<br />

Hill and Adamson, Julia Margaret Cameron,<br />

and Craig Annan; the Austrians Henneberg,<br />

Watzek, and Kuehn; the French photographers<br />

Demachy and Puyo; and the Americans<br />

Steichen, Coburn, Kasebier, White, Eugene,<br />

and, <strong>of</strong> course, Stieglitz.<br />

Greatly stimulated by his visits to 291, Strand<br />

soon decided he would become a photographer.<br />

His father approved <strong>of</strong> his choice <strong>of</strong> a career,<br />

although, unlike Stieglitz's father, he could not<br />

<strong>of</strong>fer his son financial support while he learned<br />

his craft. Upon graduation from high school in<br />

1909, Strand had to go to work as a clerk and<br />

salesman in his father's importing business, and<br />

he pursued photography in his free time on the<br />

weekends. During this period, he systematically<br />

studied techniques and materials, consciously<br />

building a solid foundation for his future work<br />

in photography.<br />

In 1911, after his father sold his business,<br />

Strand took his savings and went to Europe for<br />

the summer. He saw no examples <strong>of</strong> modern<br />

art there that might have influenced his abstract<br />

photographs; the work he admired in the<br />

museums was that <strong>of</strong> the Pre-Raphaelites and<br />

the Barbizon School, which he now considers<br />

"very poor painting." After his return from<br />

Europe, Strand set himself up as a commercial<br />

photographer, specializing in portraits and<br />

views <strong>of</strong> colleges and fraternity houses. Nevertheless,<br />

while he was doing commercial work,<br />

he was also practicing photography as an art.<br />

following the currently-fashionable fuzzy, s<strong>of</strong>tfocus<br />

styles <strong>of</strong> the Photo-Secession, reminiscent<br />

<strong>of</strong> Clarence White. 3<br />

Strand continued to visit 291 from time to<br />

time, studying the exhibitions there and bringing<br />

his work to Stieglitz for criticism. The proprietor<br />

was genuinely interested in the photographs<br />

he showed him, and his comments, the<br />

younger man recalled, were enormously helpful,<br />

for Stieglitz "would look very attentively and<br />

kindly tell me where they succeeded and where<br />

they failed." Stieglitz <strong>of</strong>fered general as well as<br />

specific advice, persuading Strand to abandon<br />

s<strong>of</strong>t-focus effects:<br />

This lens, as you're using it, makes<br />

everything look as though it is made <strong>of</strong><br />

the same stuff: grass looks like water,<br />

water looks as if it has the same quality<br />

13

as the bark <strong>of</strong> the tree. You've lost all the<br />

elements that distinguish one form <strong>of</strong> nature—whether<br />

stone or whatever it may<br />

be — from another. This is a very questionable<br />

advantage; in fact, you have<br />

achieved a kind <strong>of</strong> simplification that looks<br />

good for the moment but is full <strong>of</strong> things<br />

which will be detrimental to the final expression<br />

<strong>of</strong> whatever you are trying to do.<br />

Strand admitted that this "made a great deal<br />

<strong>of</strong> sense, and the problem could be easily<br />

solved by stopping the lens down." Clarence<br />

White and Gertrude Kasebier also <strong>of</strong>fered suggestions,<br />

but Strand said that Stieglitz gave<br />

him "the best criticism I ever had from anybody<br />

because it was the kind <strong>of</strong> criticism that<br />

you could say, 'yes, that's so,' and you could<br />

do something about it."<br />

In addition to the photography he saw, Strand<br />

found himself "tremendously interested" in<br />

Cezanne's watercolors, and he was drawn, as<br />

well, to the works <strong>of</strong> Matisse and Picasso, all<br />

exhibited at 291 before the Armory Show,<br />

which, in turn, he felt was a "tremendous<br />

event." At the Armory Show, he was particularly<br />

interested in Cezanne (he saw his<br />

oils there for the first time), Picasso and<br />

Brancusi. After that historic show, Strand continued<br />

to visit 291, and he was undoubtedly<br />

stimulated by the Picasso-Braque show and the<br />

Brancusi exhibition, both <strong>of</strong> 1914. 4<br />

Although Strand had practiced the art <strong>of</strong><br />

photography with some success before 1915,<br />

he was suddenly recognized as a major new<br />

talent in that year. The advice he had received<br />

from Stieglitz and his colleagues and the insights<br />

concerning modern art he had gained<br />

from his visits to 291 and the Armory Show<br />

enabled him to produce a remarkable group <strong>of</strong><br />

abstract photographs that were unparalleled at<br />

that time. Strand made his first experiments in<br />

this direction at Twin Lakes, Connecticut, during<br />

the summer <strong>of</strong> 1914 or 1915 (the latter<br />

date is more probable). It was here that he<br />

produced two <strong>of</strong> his most important images,<br />

"Abstraction, Bowls" and "Abstraction, Porch<br />

Shadows." 5 In the former work, Strand carefully<br />

arranged four kitchen bowls at different<br />

angles and recorded their interlocking abstract<br />

shapes, totally ignoring their utilitarian function.<br />

15

By thoughtfully planning his camera angle and<br />

cutting <strong>of</strong>f just the right amount <strong>of</strong> each bowl<br />

in framing the picture, Strand created a photograph<br />

that was organized according to rigorous<br />

principles <strong>of</strong> abstract design. The nearest prototypes<br />

in advanced French painting — his acknowledged<br />

source — are found in Picasso's<br />

and Braque's early Cubist still lifes <strong>of</strong> 1908-09,<br />

although the closest example, compositionally,<br />

is not a still life but a landscape, Braque's<br />

"<strong>House</strong>s at L'Estaque" (1908) (Herman and<br />

Marguerite Rupf Foundation, Bern). Strand,<br />

however, said he was not interested in literally<br />

imitating modernist painting. Instead, his concern<br />

was to bring the constructive methods <strong>of</strong><br />

Cubism to the task <strong>of</strong> creating a photographic<br />

image that was true to the optical properties <strong>of</strong><br />

the medium. About his efforts at this time,<br />

Strand said:<br />

I think I understood the underlying principles<br />

behind Picasso and the others in<br />

their organization <strong>of</strong> the picture space, <strong>of</strong><br />

the unity <strong>of</strong> what that organization contained,<br />

and the problem <strong>of</strong> making a twodimensional<br />

area have a three-dimensional<br />

character, so that the viewer's eye remained<br />

in that space and went into the<br />

picture and didn't go <strong>of</strong>f to the side. Everything<br />

in the picture related to everything<br />

else.<br />

A similar application <strong>of</strong> modernistic aesthetics<br />

to photography may be found in Strand's<br />

powerful "Abstraction, Porch Shadows." To<br />

create the desired arrangement, he tilted a<br />

porch table on its side so that its curved edge<br />

created a forceful contrast to the parallel diagonals<br />

<strong>of</strong> the railing's shadow. Once again he<br />

tried to obliterate his subject's useful function,<br />

fragmenting the elements and placing heavy<br />

emphasis on their formal, abstract relationships.<br />

He skillfully accentuated the formal message <strong>of</strong><br />

the photograph by tilting the finished image<br />

ninety degrees from the angle at which it was<br />

taken, thus carrying the viewer still another<br />

step away from the world <strong>of</strong> physical reality.<br />

The abstractness <strong>of</strong> this photograph places it<br />

among the most advanced American pictures <strong>of</strong><br />

its time, irrespective <strong>of</strong> medium. Only Arthur<br />

Dove and Marsden Hartley, among American<br />

artists, had previously produced paintings that<br />

reveal this degree <strong>of</strong> abstraction; Strand surely<br />

16

would have known their works through his visits<br />

to 291. At present, Strand pr<strong>of</strong>esses great admiration<br />

for Hartley, and he admits that when<br />

he executed "Abstraction, Porch Shadows," he<br />

was visually close to the painter in using bold,<br />

simple geometric shapes and patterns such as<br />

those found in "Abstract Forms" (1914-15). In<br />

the work <strong>of</strong> both artists, these abstract elements<br />

are treated largely in two-dimensional<br />

terms, arranged with little concern for pictorial<br />

depth. Both Hartley and Strand were exceptional<br />

American artists, for they practiced an<br />

advanced style for their time, the language <strong>of</strong><br />

both men echoing the synthetic Cubism <strong>of</strong> Picasso<br />

and Braque in 1912-13.<br />

Strand's early essays in abstraction helped<br />

him study the relationships between inanimate<br />

objects that he could manipulate and control.<br />

Having done this successfully in "Abstraction,<br />

Bowls" and "Abstraction, Porch Shadows," he<br />

was ready to apply the lessons he had learned<br />

to the world <strong>of</strong> human activity and to abandon<br />

formal experimentation for its own sake, never<br />

again returning to abstraction in its pure form.<br />

His new approach is found in "Wall Street"<br />

(1915), a street scene in which a group <strong>of</strong> pedestrians,<br />

casting long shadows, pass before<br />

the Morgan Building, whose imposing mass<br />

dwarfs them. Strand said that, at this time, he<br />

had become "interested in using photography<br />

to see if he could capture the physical movement<br />

<strong>of</strong> the city and, at the same time, using<br />

the movement <strong>of</strong> people and automobiles or<br />

whatever it might be, in an abstract way, always<br />

retaining the abstract principle. . . ." His<br />

innate gift <strong>of</strong> selectivity brought him success in<br />

this venture, for the pattern <strong>of</strong> the figures in<br />

movement in "Wall Street" could not have been<br />

more effective if Strand had arranged them<br />

himself.<br />

More obviously related to the aesthetics <strong>of</strong><br />

Cubism is Strand's celebrated "The White<br />

Fence." In this photograph, taken at Port Kent,<br />

New York, during the summer <strong>of</strong> 1916, he<br />

claimed he was applying the lessons he had<br />

learned in his 1914-15 abstractions to a subject<br />

taken from the real world, a subject which he<br />

had not manipulated. Strand remarked that the<br />

shapes <strong>of</strong> the fence, rather than the background,<br />

fascinated him, for each broken picket<br />

was different from every other one. Visualizing<br />

the subject in a Cubist manner, he treated the<br />

fence as a flat, geometric element close to, and<br />

paralleling, the picture plane. By this means he<br />

placed a strict limit on spatial recession. The<br />

simple, planar sides <strong>of</strong> the buildings behind the<br />

fence similarly prohibit any pronounced flow<br />

into pictorial depth because they, too, are<br />

nearly parallel to the picture plane, serving as a<br />

screen to close <strong>of</strong>f the space. The photograph<br />

succeeds as an abstract design because Strand<br />

reduced the subject to a few clearly defined<br />

geometric elements and balanced them against<br />

each other with consummate skill. In doing so,<br />

his aesthetic was not far from that <strong>of</strong> the Cubist<br />

painters, although he was certainly particularizing<br />

it through an American experience.<br />

Even more obviously Cubist in derivation is<br />

Strand's "From the Viaduct" (1916). The photographer<br />

admitted that he was affected by<br />

Cubist painting when he consciously stressed<br />

the rectangular composition. This influence is<br />

also visible in his Cubist fragmentation <strong>of</strong> lettering,<br />

which is found so <strong>of</strong>ten in Picasso's and<br />

Braque's works in 1913. Any diagonals that<br />

might suggest space are eliminated, and the<br />

whole is thus meant to read as a grid <strong>of</strong> horizontals<br />

and verticals crisscrossing the surface<br />

<strong>of</strong> the picture. This is one <strong>of</strong> the most abstract<br />

<strong>of</strong> Strand's images based on the real world.<br />

Thus far, we have been discussing photographs<br />

that show Strand's primary concern with<br />

two-dimensional pattern and abstract form. In<br />

1916, he turned quite emphatically to the real<br />

world, selecting anonymous street people as his<br />

subjects. Strand said his formal experiments<br />

culminated in these photographs, images that<br />

include his "Blind Woman" (1916) and "Portrait"<br />

(1916). To record these common people<br />

going about their daily activities, Strand devised<br />

a false lens for his Ensign reflex camera 6<br />

pointing ninety degrees away from the real lens,<br />

so that he could focus on his subjects without<br />

making them camera-shy. Unlike Baron de<br />

Meyer's contemporary photographs <strong>of</strong> picturesque<br />

gypsies and peasants, posed in the<br />

studio, Strand's were executed in the streets.<br />

Strand has said "I wanted to solve the problem<br />

<strong>of</strong> photographing these people within an<br />

environment in which they lived."<br />

He recalled having some thoughts on social<br />

17

eform when he was photographing these people<br />

<strong>of</strong> the streets, but he was not using his<br />

camera in the manner <strong>of</strong> Jacob Riis to expose<br />

the mistreatment <strong>of</strong> the working classes. He<br />

confessed: "I photographed these people because<br />

I felt that they were all people who<br />

life had battered into some sort <strong>of</strong> extraordinary<br />

interest and, in a way, nobility." The subject <strong>of</strong><br />

"Blind Woman", his masterpiece <strong>of</strong> this group<br />

<strong>of</strong> portraits, appealed to him simply because<br />

she had "an absolutely unforgettable and noble<br />

face." In his statements about his city portraits,<br />

Strand sounds very much like one <strong>of</strong> the New<br />

York Realist painters — perhaps Robert Henri<br />

or John Sloan, <strong>of</strong> the "Ashcan School" or "The<br />

Eight." This group <strong>of</strong> artists, like Strand, portrayed<br />

the daily activity <strong>of</strong> common people, not<br />

to point out social injustices, but because their<br />

lives reflected the human drama in its most<br />

natural and telling form, for example, Sloan's<br />

painting "Three A.M." (1909). In this connection,<br />

Stieglitz's representation <strong>of</strong> the lower<br />

classes in "The Steerage" (1907) could also be<br />

seen as a source <strong>of</strong> inspiration for Strand's<br />

individual portraits, and we should accept the<br />

possibility that this realistic image influenced<br />

the young photographer.<br />

Stieglitz's discovery <strong>of</strong> Strand's fresh talent<br />

seems to have rejuvenated the older man and<br />

helped to restore some <strong>of</strong> the original vitality<br />

<strong>of</strong> 291. Stieglitz, as we have seen, saw in Strand<br />

the fulfillment <strong>of</strong> his highest hopes for artistic<br />

photography, and during the last few years <strong>of</strong><br />

291 he devoted himself to the celebration <strong>of</strong><br />

Strand's genius. He wrote <strong>of</strong> Strand in Camera<br />

Work:<br />

His work is rooted in the best traditions<br />

<strong>of</strong> photography. His vision is potential. His<br />

work is pure. It is direct. It does not rely<br />

upon tricks <strong>of</strong> process. In whatever he<br />

does there is applied intelligence. In the<br />

history <strong>of</strong> photography there are but few<br />

photographers who, from the point <strong>of</strong> view<br />

<strong>of</strong> expression, have really done work <strong>of</strong><br />

any importance. And by importance we<br />

mean work that has some relatively lasting<br />

quality, that element which gives all art its<br />

real significance. 7<br />

The one-man show Stieglitz had promised<br />

Strand took place between March 13 and April<br />

3, 1916, and the last two issues <strong>of</strong> Camera<br />

Work were devoted mainly to reproductions <strong>of</strong><br />

Strand's recent photographs. Just as Steichen's<br />

photographs and ideas permeated the early volumes<br />

<strong>of</strong> Camera Work, Strand's dominated the<br />

last two issues <strong>of</strong> that periodical. Stieglitz had<br />

thus come full circle. It is fitting that Stieglitz's<br />

most important years <strong>of</strong> patronage came to an<br />

end with the recognition <strong>of</strong> an artist working in<br />

the medium which was his own first love —<br />

photography.<br />

Notes<br />

1 This article is based in large part on the section on<br />

Paul Strand in my forthcoming book on the artists <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Stieglitz circle, Stieglitz and the American Avant-Garde,<br />

to be published in 1977 by New York Graphic Society,<br />

Boston.<br />

2 All direct quotations or paraphrases from Strand's<br />

statements were based on interviews with Strand conducted<br />

in 1971, 1974, and 1975. I am indebted to the<br />

photographer for generously making himself available<br />

for interviews when he was in poor health. I am also<br />

grateful to him for reading and correcting an earlier<br />

version <strong>of</strong> this paper. Although Francis Bruguiere (1880-<br />

1945) stated that he did abstract photographs as early as<br />

1912, there are no works <strong>of</strong> that date to support his<br />

claim. It is likely that his memory was faulty on this<br />

point.<br />

3 When I first talked with Strand, he could find no examples<br />

<strong>of</strong> his work from the period before 1914-15. However,<br />

in May, 1975, as I was preparing this paper for<br />

publication, he and Mrs. Strand found a large cache <strong>of</strong><br />

his early 3Vi" x .4 1 A" glass positives in a storage warehouse<br />

in New York. The Strands generously allowed me<br />

to study these works, which reveal the photographer's<br />

pre-1915 evolution and which also include other previously<br />

unpublished examples <strong>of</strong> his abstract photography,<br />

1914-17.<br />

4 The dates <strong>of</strong> these 291 shows are as follows: Cezanne,<br />

1911 (watercolors); Matisse, 1908 (drawings, lithographs,<br />

watercolors, and etchings), 1910 (drawings and reproductions<br />

<strong>of</strong> paintings), 1912 (sculpture and drawings); Picasso,<br />

1911 (drawings and watercolors); Picasso and<br />

Braque, 1914 (drawings and paintings); Brancusi, 1914<br />

(sculpture).<br />

5 The photographs by Strand discussed in this article are<br />

well known to students <strong>of</strong> modern American photography<br />

because they were beautifully and faithfully reproduced,<br />

by photogravure, in the last two issues <strong>of</strong> Camera Work.<br />

However, the Camera Work photogravures are somewhat<br />

smaller than the platinum prints from which they were<br />

made. For example, the original images <strong>of</strong> "Abstraction,<br />

Bowls," and "Blind Woman," both in the Metropolitan<br />

Museum <strong>of</strong> Art, measure 13V4" x 9 3 A&" and 13 3 /a" x 10V2"<br />

respectively. The steps in Strand's printing process,<br />

which the photographer described to me, are worth reviewing.<br />

The photographs discussed here were taken on<br />

3'/4" x 4 1 /4" glass negatives, from which he made glass<br />

positives <strong>of</strong> the same size. He then put these into an<br />

enlarger and projected them onto a larger negative,<br />

which, when developed and printed, would yield contact<br />

prints <strong>of</strong> the size <strong>of</strong> those in the Metropolitan Museum,<br />

cited above.<br />

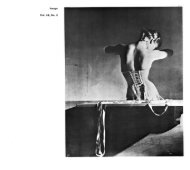

6 Strand no longer owns the original English Ensign reflex<br />

camera which he used for his early photographs.<br />

Much later he purchased one like it for sentimental reasons.<br />

The camera reproduced here is from the collection<br />

<strong>of</strong> Tom and Elinor Burnside, Pawlet, Vermont. I am grateful<br />

to them for supplying the photograph.<br />

7 Camera Work, XLVII1, October 1916, pp. 11-12.<br />

19

Rediscovering Gertrude Kasebier<br />

20

As art historians we are spoiled, if not sated,<br />

by abundant catalogues, bibliographies and indexes.<br />

A serious art historical investigation can<br />

begin with days <strong>of</strong> card thumbing and "Art-<br />

Indexing." But there is no such surfeit <strong>of</strong> photographic<br />

references.<br />

To reconstruct Gertrude Kasebier's career, it<br />

was necessary to supplement meager bibliographies<br />

by speculative searching through magazines<br />

in which she had surely published, and<br />

through those in which she might have been<br />

discussed. This intensive hunt for uncatalogued<br />

material revealed that between 1900 and 1910<br />

Mrs. Kasebier's photographs were frequently<br />

and widely published; her name and photographs<br />

were familiar to thousands <strong>of</strong> readers <strong>of</strong><br />

such popular magazines as The World's Work,<br />

McClure's, Everybody's <strong>Magazine</strong> and The<br />

Ladies Home Journal.<br />

Among her illustrations are many portraits<br />

which help us understand why, in 1898, Alfred<br />

Stieglitz proclaimed Mrs. Kasebier "beyond<br />

dispute, the leading portrait photographer in<br />

the country," and why Charles H. Caffin and<br />

Frances Benjamin Johnston gave high praise to<br />

her commercial portraits. 1 Numerous portraits<br />

<strong>of</strong> men show us that Mrs. Kasebier was not<br />

principally a photographer <strong>of</strong> women and children,<br />

although her pictures <strong>of</strong> women and children<br />

are best known now. The most famous <strong>of</strong><br />

these — "Blessed Art Thou Among Women,"<br />

"The Manger," and "Miss N." — were all published<br />

in the first issue <strong>of</strong> Camera Work, which<br />

Stieglitz devoted to Mrs. Kasebier. 2<br />

Kasebier's pictures <strong>of</strong> serene motherhood invite<br />

comparison with those <strong>of</strong> Mary Cassatt,<br />

but I have found no connection between the<br />

women. Many artists <strong>of</strong> this period depicted maternal<br />

scenes; Kasebier and Cassatt are simply<br />

two artists best known for mother-child pictures.<br />

Unlike the wealthy expatriate spinster who devoted<br />

her entire life to art, Mrs. Kasebier began<br />

her career in the middle <strong>of</strong> her life; her Photo-<br />

Secession colleagues (as well as her grandchildren)<br />

called her "Granny."<br />

Mrs. Kasebier grew up in the midwest and<br />

Colorado, came East after her father's death,<br />

and married an unimaginative German immigrant<br />

businessman. She raised three children<br />

on a farm in New Jersey, then moved the family<br />

to Brooklyn near the newly opened Pratt<br />

Institute, where she enrolled in 1889 to study<br />

portrait painting. Photography was not taught<br />

at Pratt in the early years; in fact, the faculty<br />

dissuaded her from it. 3<br />

On a trip to Europe in 1893, her interest in<br />

photography revived and grew until she quit<br />

painting in favor <strong>of</strong> photography. She returned<br />

to Brooklyn and asked a neighborhood photographer,<br />

Samuel H. Lifshey, to teach her how to<br />

run a portrait studio. Lifshey at first resisted this<br />

unconventional apprentice, but her characteristic<br />

persistence and charm won him over. 4<br />

In the late 1890s, despite her husband's protests<br />

that others might think he could not support<br />

her, she set up her own portrait studio on<br />

Fifth Avenue. 5 She rose to international fame<br />

both as a commercial portraitist and as a member<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Photo-Secession.<br />

It is as a founding member <strong>of</strong> the Photo-Secession<br />

that she is best known today. A study<br />

<strong>of</strong> Mrs. Kasebier's work, showing her aims in<br />

portraiture and suggesting how her portraits<br />

influenced other photographers helps to balance<br />

this lopsided view.<br />

Mrs. Kasebier set two goals for portraits:<br />

1. to show personality: "to make likenesses<br />

that are biographies, to bring out in each<br />

photograph the essential personality . . ." 6<br />

2. to compose pictures clearly and simply:<br />

"One <strong>of</strong> the most difficult things to learn<br />

in painting is what to leave out. How to<br />

keep things simple enough. The same applies<br />

to photography. The value <strong>of</strong> composition<br />

cannot be overestimated: upon it depends<br />

the harmony and the sentiment." 7<br />

Mrs. Kasebier's scorn for overstuffed studio<br />

portraiture is evident in her description <strong>of</strong> a<br />

portrait by W. J. Root <strong>of</strong> Chicago which had<br />

been reproduced in Photo Mosaics, an annual<br />

<strong>of</strong> 1898:<br />

We have here a painted, scenic background,<br />

a palm, a gilt chair, and something<br />

which looks like a leopard-skin,<br />

though why it is introduced I cannot imagine,<br />

as summer seems to be indicated;<br />

perhaps it is to cover the legs <strong>of</strong> the chair,<br />

perhaps it is used because "fur takes<br />

well." I presume if an elephant had been<br />

handy the "artist" would have tried to work<br />

it in. Something should always be left to<br />

the imagination. We do not always see<br />

people under a search light. There is also<br />

a girl in the picture. She cuts the space in<br />

two. There is no center <strong>of</strong> interest; the eye<br />

wanders about from one thing to another,<br />

the fur rug seeming to be most important<br />

because it is out <strong>of</strong> place and superfluous.<br />

8<br />

I like to think <strong>of</strong> the "Portrait <strong>of</strong> Miss N." as<br />

Mrs. Kasebier's rejoinder to the Root portrait.<br />

"Miss N." was Evelyn Nesbit, well-known as a<br />

model and showgirl before Mrs. Kasebier made<br />

this portrait for Miss Nesbit's protector and<br />

lover, the architect Stanford White. Among the<br />

many drawings and photographs I've seen <strong>of</strong><br />

Miss Nesbit (including Rudolph Eickemeyer's<br />

photographs <strong>of</strong> her), I know <strong>of</strong> none which so<br />

fully suggests the ripe, youthful, seductive<br />

beauty which enchanted Stanford White and<br />

which later caused Harry Thaw — Miss Nesbit's<br />

rich but crazed husband — to murder White in<br />

a fit <strong>of</strong> retrospective jealousy. 9 21

Both portraits begin with a young brunette in<br />

a white decollete gown. But "Miss N." tempers<br />

the excesses <strong>of</strong> Root's portrait: there is no<br />

scenic background; there are no distractions;<br />

there are only the dark curves <strong>of</strong> the s<strong>of</strong>a behind<br />

Miss Nesbit, and these draw our eyes back<br />

to Miss Nesbit's dark curly hair and to her face.<br />

There is no mistaking that she is the center <strong>of</strong><br />

interest in this picture.<br />

Several creative years lay between Mrs. Kasebier's<br />

statement <strong>of</strong> what not to do in portraiture<br />

and her portrait <strong>of</strong> Miss. N. In her earliest efforts<br />

to simplify portraiture, Mrs. Kasebier had<br />

transferred her knowledge <strong>of</strong> painting to photography.<br />

Most <strong>of</strong> her portraits <strong>of</strong> the 1890s<br />

have the deep tones <strong>of</strong> Renaissance painting.<br />

Her young models wear clothes and expressions<br />

suggestive <strong>of</strong> paintings from earlier centuries:<br />

there are fur collars, square necklines,<br />

dreamy poses. 10 In "Flora" (c. 1900) the pr<strong>of</strong>ile<br />

view <strong>of</strong>fers little opportunity to show emotion<br />

or personality; the picture is vaguely reminiscent,<br />

however, <strong>of</strong> Renaissance portraits.<br />

The beauty <strong>of</strong> the original platinum print depends<br />

upon the glow <strong>of</strong> light on the hair and<br />

the sheen <strong>of</strong> the velvet gown. In a printed reproduction,<br />

much <strong>of</strong> the original print's luminous<br />

texture and tone are lost.<br />

In 1900, Mrs. Kasebier began photographing<br />

well-known men for The World's Work, a new<br />

serious illustrated monthly, broadly concerned<br />

with art, social problems, history and contemporary<br />

life. The portraits Mrs. Kasebier made<br />

for The World's Work and those she later made<br />

for the art magazine, The Craftsman, deserve<br />

study because they comprise datable groups <strong>of</strong><br />

portraits in which we can find changes in her<br />

style. Most <strong>of</strong> Mrs. Kasebier's portraits before<br />

1900 were neck or bust length, but her portraits<br />

for The World's Work are all three-quarter<br />

length, doubtless because she wanted to show<br />

personality through stance and gesture, as well<br />

as through facial expression.<br />

However, her earliest portrait for The World's<br />

Work, Mark Twain (December 1900) still alludes<br />

to painting. Twain stands against a dark<br />

ground; the face and hands get greatest emphasis.<br />

Only the slight turn <strong>of</strong> Twain's head<br />

and the projection <strong>of</strong> his hand and pipe indicate<br />

depth; the background is murky, undefined.<br />

Within this simple format, Twain holds<br />

our attention as though he were in a spotlight,<br />

about to spin one <strong>of</strong> his fantastic tales.<br />

In her perceptive study <strong>of</strong> Jacob A. Riis, the<br />

muckraker-photographer (The World's Work,<br />

March 1901), Mrs. Kasebier depicts a tense<br />

man too busy to sit down, too preoccupied to<br />

have had his suit pressed. Although his portrait,<br />

like Twain's, is centered, we feel none <strong>of</strong><br />

Twain's ease. Tension has been heightened by<br />

compression <strong>of</strong> space, space defined only by<br />

the angle <strong>of</strong> Riis' stance and by his shadow, so<br />

that he seems squeezed between backdrop and<br />

picture plane. In this taut portrait, Mrs. Kasebier<br />

achieved an early success in portrayal through<br />

pose, composition and gesture. 11<br />

Mrs. Kasebier soon arrived at a recognizable<br />

portrait style which is distinguishable by asymmetrical<br />

placement <strong>of</strong> a seated figure and by<br />

graded areas <strong>of</strong> tone. Her geometric, orientalized<br />

monogram — an abstracted GK and umlaut—<br />

is <strong>of</strong>ten a prominent hallmark.<br />

In The World's Work, the Kasebier photographs<br />

separate themselves from "mug shots"<br />

by other photographers. Mrs. Kasebier introduces<br />

each subject as though we had been<br />

granted a private interview in his <strong>of</strong>fice. The<br />

portrait <strong>of</strong> Booker T. Washington (The World's<br />

Work, January 1901) shows the pose in which<br />

she typically placed her subject: seated to one<br />

side with an arm (or back) parallel to the vertical<br />

edge <strong>of</strong> the picture, forearm parallel to the<br />

bottom edge, so that the figure fills a lower<br />

corner <strong>of</strong> the plate. She retains a neutral background<br />

(usually dark, as here; sometimes middletoned).<br />

The figure seems to come forward<br />

from the undefined back plane. Our understanding<br />

<strong>of</strong> space comes from the angle <strong>of</strong> the figure<br />

in his chair.<br />

This pose becomes almost a formula in Kasebier's<br />

portraits <strong>of</strong> this period. 12 Having resolved<br />

the problem <strong>of</strong> placing the figure within the<br />

frame, she could devote greater perception to<br />

23

her subject, always emphasizing the character<br />

<strong>of</strong> face and hands. In her portrait <strong>of</strong> Booker T.<br />

Washington, Kasebier has caught the sober expression<br />

and powerful hands <strong>of</strong> the man who<br />

recalled in his autobiography, Up From Slavery,<br />

"There was no period <strong>of</strong> my life that was devoted<br />

to play."<br />

In other photographers' portraits reproduced<br />

in The World's Work we are <strong>of</strong>ten struck by<br />

harsh contrasts <strong>of</strong> lights and darks, but in<br />

Kasebier's portraits graded tones model figures<br />

and lend variety and interest. Mrs. Kasebier no<br />

longer relies on definition <strong>of</strong> texture as she<br />

did in the early portrait <strong>of</strong> "Flora". She seems<br />

to have learned that such subtlety would be<br />

lost in reproduction.<br />

Mrs. Kasebier used the seated format frequently,<br />

but not exclusively. In her portrait <strong>of</strong><br />

New York Governor Benjamin B. Odell (The<br />

World's Work, July 1901), frontal pose and<br />

direct gaze made a formal, dignified portrait.<br />

Strong vertical lines — the side <strong>of</strong> his chair,<br />

the front edge <strong>of</strong> his jacket, part <strong>of</strong> his left arm<br />

and the outline <strong>of</strong> the painting behind him —<br />

repeat his pose, reminding us that the governor<br />

is, indeed, an upstanding public <strong>of</strong>ficial.<br />

The pictures analyzed show the deliberate<br />

composition we would expect from a trained<br />

painter, and they demonstrate Mrs. Kasebier's<br />

principle that "the value <strong>of</strong> composition cannot<br />

be overestimated." These portraits also illustrate<br />

her statement that:<br />

If you look at one object the surrounding<br />

ones are mere impressions. You know what<br />

stopping down does. Only as much detail<br />

should be permitted as is necessary to<br />

support the composition. 13<br />

But Mrs. Kasebier wished to make "likenesses<br />

that are biographies"; therefore she<br />

kept backgrounds in focus when they added<br />

meaning to her subject. She experimented in<br />

environmental portraiture, in using a person's<br />

surroundings or activity to enhance our understanding<br />

<strong>of</strong> him. She shows Physics Pr<strong>of</strong>essor<br />

Michael I. Pupin (The World's Work, March<br />

1901) in a Columbia University classroom, his<br />

backdrop a blackboard full <strong>of</strong> equations — a<br />

typical situation, a former Pupin student recalled.<br />

14<br />

By 1905, Kasebier photographs were widely<br />

known through publication, not only in The<br />

World's Work, but in Everybody's <strong>Magazine</strong>,<br />

McClure's <strong>Magazine</strong> and popular photographic<br />

magazines such as Photo-Era and The Photographic<br />

Times, as well as through Stieglitz's<br />

efforts in Camera Notes, Camera Work and<br />

through his Photo-Secession exhibitions.<br />

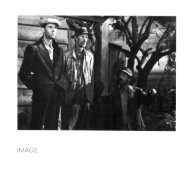

The photographs she made in 1906-1907 <strong>of</strong><br />

the "Ashcan" painters — properly called "The<br />

Eight" — were published in The Craftsman in<br />

1908. 15 These portraits show how Mrs. Kasebier<br />

matured as a portraitist by using more<br />

varied poses and more complex compositions<br />

than in her earlier work. Although I do not<br />

know the precise order in which she made<br />

them, I have organized them to indicate increasing<br />

complexity and sophistication in Mrs.<br />

Kasebier's vision.<br />

William Glackens was surely one <strong>of</strong> Kasebier's<br />

least relaxed subjects. With gloves and<br />

walking stick, he appears ready to bolt. Glackens<br />

was, in fact, not happy about the pictures.<br />

He wrote to his wife:<br />

The Craftsman has come out with all <strong>of</strong> us<br />

a la Kasebier [sic]. They evidently got<br />

pro<strong>of</strong>s from her. They are awfully silly 16<br />

Such negative reactions to Kasebier's portraits<br />

were uncommon in her time, but this comment<br />

is noteworthy even more because Glackens<br />

was one <strong>of</strong> several contemporaries who remarked<br />

on Kasebier's identifiable style. "A la<br />

Kasebier" [sic] does not define her work —<br />

but notice that Glackens sits in that typical<br />

Kasebier pose, asymmetrically placed on one<br />

side <strong>of</strong> the picture, his shoulders slightly<br />

angled away. Kasebier has made a decorative<br />

motif <strong>of</strong> Glackens' upright walking stick; it is<br />

one <strong>of</strong> several vertical lines which echo Glackens'<br />

stiff-backed position.<br />

In both the Glackens portrait and that <strong>of</strong><br />

Arthur B. Davies, there is a departure: a divided<br />

background suggests space behind the<br />

subjects. For Davies, as for earlier portraits,<br />

Kasebier poses the figure in pr<strong>of</strong>ile, the back<br />

parallel to the picture edge, face turned toward<br />

us. Probably as a result <strong>of</strong> this sitting,<br />

25

Davies and Mrs. Kasebier became well acquainted,<br />

and she purchased some <strong>of</strong> his<br />

paintings. Davies, the painter <strong>of</strong> idyllic landscapes,<br />

was one <strong>of</strong> the chief organizers <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Armory Show in 1913. Knowing <strong>of</strong> the friendship<br />

and artistic admiration between Mrs.<br />

Kasebier and Auguste Rodin, Davies borrowed<br />

seven Rodin drawings from her, to exhibit at<br />

the Armory Show. 17<br />

In Ernest Lawson's portrait the space is shallow,<br />

but defined by the angled chair whose<br />

post marks the front plane and whose rails<br />

diagonally recede in space. The background<br />

here, in focus, is a leafy patterned fabric. Lawson's<br />

relaxed pose suggests a momentary position<br />

and expression.<br />

Even more complex is the portrait <strong>of</strong> John<br />

Sloan. He sits sideways on a chair set at an<br />

angle, with its back toward us. Space is far<br />

deeper than in any <strong>of</strong> the early pictures. Sloan<br />

sits in the middle ground; the foreground is<br />

defined by a small table on which his hat and<br />

some photographs rest. Mrs. Kasebier would<br />

surely have removed that hat had she not felt<br />

it added interest to the picture. Note the division<br />

<strong>of</strong> background into three stripes: the<br />

medium-tone patterned drape behind him recedes<br />

to a light wall, then to a dark area. This<br />

picture is broken into many shapes and tonal<br />

areas, whereas the earliest pictures (Mark<br />

Twain, Jacob Riis) could be read as just a few<br />

areas <strong>of</strong> pattern and tone.<br />

Although Sloan, who sometimes photographed<br />

his own paintings, did not think much<br />

<strong>of</strong> s<strong>of</strong>t focus photography (he called it "art<br />

'phuzzygraphy' "), 18 he liked Mrs. Kasebier's<br />

work. In his diaries he described her as "a<br />

very pleasant, middle aged lady, who is doing<br />

some fine things in photography. An Indian<br />

head she showed me was fine. Henri's pro<strong>of</strong>s<br />

are very good, best photographs <strong>of</strong> him yet. . . .<br />

She knows her pr<strong>of</strong>ession, sure gets you at<br />

your ease." 19<br />

In her photograph <strong>of</strong> Everett Shinn, Mrs.<br />

Kasebier has come full circle to tackle and<br />

redefine the problem posed in Root's photograph:<br />

to photograph a full-length figure in a<br />

furnished studio. But her studio has not the<br />

pretentious trappings she condemned in the<br />

Photo-Mosaics portrait; it is bare except for<br />

objects <strong>of</strong> her own taste and making. There is<br />

the striped Indian rug, which defines the space<br />

Shinn stands in, and her own portrait <strong>of</strong> Rodin,<br />

20 whose pose repeats Shinn's stance.<br />

Shinn seems unposed; he takes a casual<br />

momentary position one might assume for a<br />

snapshot. Kasebier seems here to have abandoned<br />

the assumption, traditional in painting,<br />

that a portrait ought to be a formal eternal<br />

symbol <strong>of</strong> its subject; Shinn is shown as he<br />

stood at a photographic "point in time." We<br />

sense he will shift weight soon again, and<br />

take another drag on his cigarette.<br />

Mrs. Kasebier had begun by rebelling<br />

against the status quo, by simplifying portraiture<br />

radically. Then she learned to make<br />

portraits that were more and more complex,<br />

that showed deep space, but were always carefully<br />

composed <strong>of</strong> interesting shapes and <strong>of</strong><br />

light and dark areas. Her earliest portraits took<br />

their cue from painting, her later ones, especially<br />

<strong>of</strong> Lawson, Sloan and Shinn, seem<br />

conceived in the ground glass.<br />

I believe Mrs. Kasebier deliberately used a<br />

different mode for magazine reproduction than<br />

for exhibition. She carefully chose and clearly<br />

printed portraits for publication. She seldom<br />

used manipulated negatives or handworked<br />

gum prints for published portraits.<br />

Three portraits she made <strong>of</strong> Robert Henri<br />

show how she selected photographs for their<br />

appropriate use. In the portrait reproduced by<br />

The Craftsman, we sense the presence <strong>of</strong> the<br />

dynamic organizer and spiritual leader <strong>of</strong> "The<br />

Eight," the author <strong>of</strong> The Art Spirit who for<br />

many years was the leading painting teacher in<br />

the United States. This portrait is forceful,<br />

despite printing blemishes (such as the black<br />

spot on his hand) because it depends not on<br />

tonal or textural subtleties, but on Henri's direct<br />

gaze and a variety <strong>of</strong> shapes such as the<br />

outline <strong>of</strong> his body, the splayed fingers <strong>of</strong> his<br />

right hand, his umbrella, his hat.<br />

Mrs. Kasebier must have liked the platinum<br />

portrait or she would not have signed it. But it<br />

is not as graphic as the one reproduced in The<br />

Craftsman; it lacks a sense <strong>of</strong> presence, <strong>of</strong><br />

confrontation. The background detracts from<br />

the subject; the hat and right hand are not<br />

part <strong>of</strong> a unified pattern. As far as I now know,<br />

it was not published nor exhibited.<br />

The gum print <strong>of</strong> Henri which Mrs. Kasebier<br />

28

chose to exhibit in her retrospective at the<br />

Brooklyn Institute <strong>of</strong> Arts and Sciences in<br />

1929, 21 suggests the thoughtful artistic side <strong>of</strong><br />

Henri's personality. His gaze is averted; head<br />

and relaxed long-fingered hands are emphasized<br />

as if to symbolize thought and dextrous<br />

creativity. The outline <strong>of</strong> brushstrokes is perhaps,<br />

in part, a tribute to Henri's own painting.<br />

The attraction <strong>of</strong> this print depends largely on<br />

the rich blacks (doubtless achieved with multiple<br />

printing) and the palpable texture <strong>of</strong> the<br />

paper, qualities which may be appreciated in<br />

exhibition but are lost in reproduction.<br />

Mrs. Kasebier's three portraits <strong>of</strong> Henri do<br />

not imply sequence; they suggest instead an<br />

understanding that each portrait might show a<br />

different aspect <strong>of</strong> his personality. But, so far<br />

as I know, these variants were not exhibited<br />

together. Implicit in Kasebier's work, however,<br />

is the concept <strong>of</strong> multiple portraiture. Years<br />

later, Stieglitz in his Georgia O'Keeffe portraits,<br />

articulated the idea, full grown.<br />

It was <strong>of</strong>ten said in Kasebier's time that she<br />

set the example for commercial photographers<br />

to discard their props and backdrops. We now<br />

know that the channels through which her<br />

work became pervasive were the widely circulated<br />

popular magazines as well as photographic<br />

journals. It is easy to understand that<br />

through mass circulation, she created a new<br />

portrait fashion.<br />

Mrs. Kasebier's effect on her Photo-Secession<br />

colleagues is more subtle, and harder to<br />

define. Even before 1900, Kasebier provided an<br />

example to the Stieglitz group <strong>of</strong> new approaches<br />

to portraiture. By 1900, she had<br />

shown that portraiture could unite commerce<br />

and art. 22 This example would have been<br />

meaningful to Edward Steichen, whose friendship<br />

with Mrs. Kasebier in Paris, 1901, impelled<br />

him to write "She has been goodness<br />

itself to me and pumped much new energy and<br />

enthusiasm into me." 23 Mrs. Kasebier would<br />

have been a model to Steichen that art, photography,<br />

and a means <strong>of</strong> making a livelihood<br />

could be compatible in commercial portrait<br />

photography.<br />

Alvin Langdon Coburn worked with Kasebier<br />

for about a year around 1902-1903; 24 he surely<br />

knew her portrait methods. (Kasebier's portraits<br />

<strong>of</strong> Coburn, apparently made during these<br />

years, are in the collections at IMP/GEH and<br />

at The Museum <strong>of</strong> Modern Art.) Coburn's approach<br />

to portraiture, as he tells <strong>of</strong> it in his<br />

autobiography, recalls Kasebier's:<br />

A photographic portrait needs more collaboration<br />

between sitter and artist than a<br />

painted portrait. A painter can get acquainted<br />

with his subject in the course <strong>of</strong><br />

several sittings, but usually the photographer<br />

does not have this advantage. You<br />

can get to know an artist or an author to<br />

a certain extent from his pictures or books<br />

before meeting him in the flesh, and I always<br />

tried to acquire as much <strong>of</strong> this<br />

previous information as possible before<br />

venturing in quest <strong>of</strong> great men, in order<br />

to gain an idea <strong>of</strong> the mind and character<br />

<strong>of</strong> the person I was to portray. 25<br />

30

Coburn's statement was made late in his life,<br />

and we cannot surely say his ideas were derived<br />

solely from Mrs. Kasebier. Yet she must<br />