11ZAQGM

11ZAQGM

11ZAQGM

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Empowered lives.<br />

Resilient nations.<br />

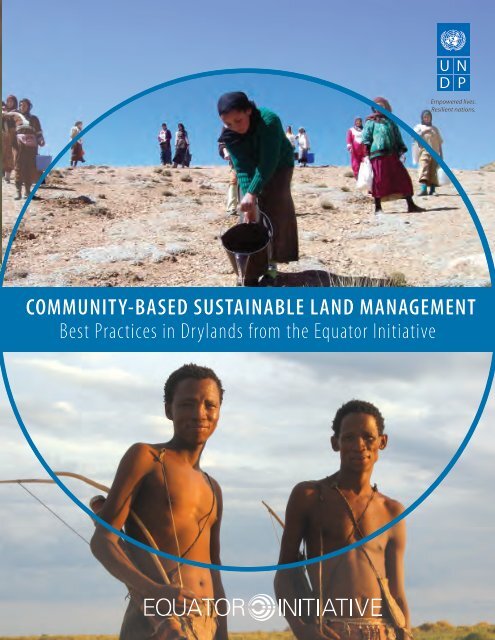

COMMUNITY-BASED SUSTAINABLE LAND MANAGEMENT<br />

Best Practices in Drylands from the Equator Initiative

Empowered lives.<br />

Resilient nations.<br />

COMMUNITY-BASED SUSTAINABLE LAND MANAGEMENT<br />

Best Practices in Drylands from the Equator Initiative

Editors<br />

Joseph Corcoran<br />

Greg Mock<br />

Contributing Writers to Equator Initiative Case Study Series<br />

Edayatu Abieodun Lamptey, Erin Atwell, Jonathan Clay, Joseph Corcoran, Sean Cox, Larissa Currado, David<br />

Godfrey, Sarah Gordon, Oliver Hughes, Wen-Juan Jiang, Sonal Kanabar, Dearbhla Keegan, Matthew Konsa,<br />

Rachael Lader, Erin Lewis, Jona Liebl, Mengning Ma, Mary McGraw, Brandon Payne, Juliana Quaresma, Peter<br />

Schecter, Martin Sommerschuh, Whitney Wilding<br />

Equator Initiative<br />

Environment and Energy Group<br />

Bureau for Development Policy<br />

United Nations Development Programme<br />

304 East 45th St. New York, NY 10017<br />

www.equatorinitiative.org<br />

Cite as:<br />

United Nations Development Programme. 2013. Community-Based Sustainable Land Management:<br />

Best Practices in Drylands from the Equator Initiative. New York, NY: UNDP.<br />

Cover photos:<br />

Top: Top: Land restoration in the High Atlas Mountains, Morocco. Photo: Association Amsing.<br />

Bottom: !Kung San game guards on patrol in Namibia: N≠a Jaqna Conservancy.<br />

Back page: Pack of Simien foxes at sunset, Ethiopia. Photo: Guassa-Menz Community Conservation Area.<br />

Published by:<br />

United Nations Development Programme, 304 East 45th Street New York, NY 10017<br />

September 2013<br />

© 2013 United Nations Development Programme<br />

All rights reserved<br />

Printed in the United States<br />

The Equator Initiative gratefully acknowledges the leadership of Eileen de Ravin, as well as the generous support<br />

of its partners.<br />

Empowered lives.<br />

Resilient nations.<br />

ii<br />

Community-Based Sustainable Land Management: Best Practices in Drylands from the Equator Initiative

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

Introduction....................................................................................................................................................................................................1<br />

Case Studies................................................................................................................................................................................................. 11<br />

Abrha Weatsbha Community, Ethiopia........................................................................................................................................ 11<br />

Association Amsing, Morocco......................................................................................................................................................... 21<br />

Chibememe Earth Healing Association, Zimbabwe................................................................................................................ 33<br />

Community Markets for Conservation, Zambia....................................................................................................................... 41<br />

Guassa-Menz Community Conservation Area, Ethiopia........................................................................................................ 53<br />

Il Ngwesi Group Ranch, Kenya........................................................................................................................................................ 61<br />

Itoh Community Graziers Common Initiative Group, Cameroon....................................................................................... 71<br />

Maasai Wilderness Conservation Trust, Kenya........................................................................................................................... 77<br />

Makuleke Ecotourism Project – Pafuri Camp, South Africa................................................................................................... 87<br />

N≠a Jaqna Conservancy, Namibia................................................................................................................................................. 95<br />

Pastoralist Integrated Support Programme, Kenya...............................................................................................................105<br />

Shinyanga Soil Conservation Programme (HASHI), Tanzania...........................................................................................115<br />

Shompole Community Trust, Kenya............................................................................................................................................127<br />

St. Catherine Medicinal Plants Association, Egypt.................................................................................................................135<br />

Suledo Forest Community, Tanzania..........................................................................................................................................145<br />

Swazi Indigenous Products, Swaziland......................................................................................................................................153<br />

Torra Conservancy, Namibia..........................................................................................................................................................163<br />

Ujamaa Community Resource Team, Tanzania.......................................................................................................................173<br />

Village Development Committee of Ando Kpomey, Togo..................................................................................................181<br />

Zenab for Women in Development, Sudan..............................................................................................................................189<br />

Community-Based Sustainable Land Management: Best Practices in Drylands from the Equator Initiative<br />

iii

Introduction<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

Community-based action, initiated and carried out by local organizations, has an impressive record of<br />

successfully delivering development at the local level. Local actors are the chief stewards of the world’s<br />

ecosystems – including drylands – and they make the vast majority of daily environmental management<br />

decisions with their land use and investment choices. Over generations, they have used their traditional ecological<br />

knowledge to manage natural resources, conserve and maintain ecosystems, and adapt to environmental changes.<br />

Local civil society groups – employing community-based approaches – deliver a wide range of development benefits<br />

when empowered to manage their ecosystems and natural resources. These benefits extend well beyond poverty<br />

reduction and livelihood gains and encompass the social, economic, and environmental dividends that underpin<br />

sustainable development.<br />

Since 2002, the Equator Initiative partnership has been working to recognize and advance local and indigenous<br />

efforts that reduce poverty through the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity. One of the primary ways<br />

this is accomplished is through the Equator Prize, awarded every two years to leading examples of local sustainable<br />

development solutions for people, nature and resilient communities. To date, the prestigious international<br />

prize has been awarded to 152 local and indigenous communities, many of which are active in sustainable land<br />

management in drylands ecosystems.<br />

This case study compendium brings together detailed case studies on twenty Equator Prize winners that<br />

have demonstrated outstanding achievement and success in sustainable land management. Each is from the<br />

African continent and each tells the story of community leadership in addressing those social, environmental<br />

and economic issues that are specific to drylands ecosystems. The intention of the compendium is to present<br />

and promote these community projects as best practices in sustainable land management, and to offer them as<br />

instructive examples of the environment and development dividends that are possible from empowering local<br />

and indigenous community management of dryland ecosystems and resources. The case material, lessons and<br />

guidance put forward in this compendium are offered as an input to the Eleventh Conference of the Parties to the<br />

UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD).<br />

1 Community-Based Sustainable Land Management: Best Practices in Drylands from the Equator Initiative

Introduction<br />

THE EQUATOR INITIATIVE: A PARTNERSHIP FOR RESILIENT COMMUNITIES<br />

The Equator Initiative brings together the United Nations, governments, civil society groups, businesses, and<br />

grassroots organizations to recognize and advance local sustainable development solutions for people, nature<br />

and resilient communities. The partnership arose from recognition that the greatest concentrations of both<br />

biodiversity and acute poverty coincide in equator belt countries, and the high potential for win-win outcomes<br />

where biological wealth could be effectively managed to create sustainable livelihoods for the world’s most<br />

vulnerable and economically marginalized populations. The high dependence of the rural poor on nature for their<br />

livelihoods means that biodiversity loss often exacerbates local poverty. But by the same token, action to sustain<br />

ecosystems and maintain or restore biodiversity can help stabilize and expand local resource-based economies<br />

and relieve poverty.<br />

The Equator Initiative aims to recognize the success of local and indigenous initiatives, create opportunities and<br />

platforms for the sharing of knowledge and good practice, inform policy to foster an enabling environment for<br />

local and indigenous community action, and develop the capacity of local and indigenous communities to scaleup<br />

their impact. The center of Equator Initiative programming is the Equator Prize, awarded biennially to recognize<br />

and advance local sustainable development solutions. As local and indigenous groups across the world chart a<br />

path towards sustainable development, the Equator Prize shines a spotlight on their efforts by honoring them on<br />

an international stage. The Equator Prize is unique for awarding group or community achievement, rather than<br />

that of individuals. Selection criteria include the following:<br />

• Impact: Initiatives that have improved community wellbeing and local livelihoods through sustainable natural<br />

resource management and/or environmental conservation of land based and/or marine resources.<br />

• Sustainability: Initiatives that can demonstrate enduring institutional, operational and financial sustainability<br />

over time.<br />

• Innovation and Transferability: Initiatives demonstrating new approaches that overcome prevailing constraints<br />

and offer knowledge, experience and lessons of potential relevance to other communities.<br />

• Leadership and Community Empowerment: Initiatives demonstrating leadership that has inspired action and<br />

change consistent with the vision of the Equator Initiative, including policy and/or institutional change, the<br />

empowerment of local people, and the community management of protected areas.<br />

• Empowerment of Women and Social Inclusion: Initiatives that promote the equality and empowerment of<br />

women and/or marginalized groups.<br />

• Resilience, Adaptability and Self-Sufficiency: Initiatives demonstrating adaptability to environmental,<br />

social and economic change, resilience in the face of external pressures, and improved capacity for local<br />

self-sufficiency.<br />

Community-Based Sustainable Land Management: Best Practices in Drylands from the Equator Initiative<br />

2

Introduction<br />

UNDP AND LOCAL CAPACITY<br />

Over the past two decades, UNDP has engaged with thousands of communities worldwide to support local<br />

development in a variety of ways, from development of pro-poor infrastructure, to expanding local government<br />

capacity, to helping communities prepare for and recover from natural disasters. A substantial portion of UNDP’s<br />

local work has involved supporting rural communities in their efforts to sustainably manage local ecosystems in<br />

a way that increases local incomes, empowers local residents, and maintains and enhances the environmental<br />

services these ecosystems render.<br />

Through this work, UNDP has accumulated a significant body of experience in local approaches to sustainable<br />

development. This emphasis on community-based action is seen as an essential counterpoint and complement to<br />

UNDP’s work at the national and international levels to mainstream environment, energy, and poverty concerns<br />

into national planning and development processes. The UNDP-implemented GEF-Small Grants Programme (SGP),<br />

the Equator Initiative, the Energy Access Programme, and the Community Water Initiative have together facilitated<br />

thousands of local interventions and provided working examples of how to effectively localize the MDGs.<br />

UNDP work at the local level is guided by four Strategic Priorities: promote rights, access, and finance mechanisms;<br />

enhance environmental management and finance capacity; facilitate learning and knowledge-sharing, and<br />

strengthen community voices in policy processes. These are all strongly correlated and interdependent, where<br />

positive outcomes in one area result in positive outcomes in the others.<br />

UNDP AND SUSTAINABLE LAND MANAGEMENT<br />

UNDP is also committed to addressing sustainable development challenges in drylands ecosystems. Many people<br />

living in drylands depend directly upon a highly variable natural resource base for their livelihoods, and about half of all<br />

dryland inhabitants - one billion people - are poor and marginalized. This accounts for close to half of the world’s poor.<br />

The Drylands Development Centre (DDC) is a thematic centre of UNDP dedicated to fighting poverty and achieving<br />

sustainable development in the drier regions of the world. UNDP-DDC works through an Integrated Drylands<br />

Development Programme to achieve three interlinked goals:<br />

1. Mainstream drylands issues, including climate change adaptation and mitigation, into national policies,<br />

planning and development frameworks, and contribute to the effective implementation of the United Nations<br />

Convention to Combat Desertification.<br />

2. Reduce the vulnerability of drylands communities to environmental, economic and socio-cultural challenges<br />

such as climate risks, drought, land degradation, poor markets, and migration, and build their capacity to<br />

adapt to climate change.<br />

3. Help drylands communities to improve local governance, management and utilization of natural resources.<br />

To achieve these goals, the centre concentrates its work on several priority topics. These include making rural<br />

markets in drylands work for the poor, managing drought risks, increasing land tenure security, and promoting the<br />

decentralized governance of natural resources.<br />

3 Community-Based Sustainable Land Management: Best Practices in Drylands from the Equator Initiative

Introduction<br />

IDENTIFYING BEST PRACTICE IN COMMUNITY-BASED SUSTAINABLE LAND<br />

MANAGEMENT IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA<br />

Land degradation is a serious problem in Sub-Saharan Africa, where up to two-thirds of the productive land area<br />

may be affected. Over 3% of agricultural gross domestic product (GDP) is lost annually as a direct result of soil and<br />

nutrient loss from poor land management practices, with associated economic costs estimated at US$9 billion per<br />

year. Communities suffer acutely from the resulting food and energy insecurity and foregone investments in social<br />

services and infrastructure.<br />

The drivers of unsustainable land management practices are complex, and practical policy responses require the<br />

active engagement of local communities and civil society organizations. Unfortunately, previous interventions to<br />

halt land degradation have tended to suffer from top-down planning processes, where land users are not actively<br />

involved in identifying problems and finding solutions. Many interventions have been sector-based, such as<br />

high-input approaches to increase agricultural production. These have met with limited success in addressing<br />

what is a multi-dimensional problem, and have typically minimized community participation.<br />

However, in recent years, the essential role of local and indigenous communities in sustainable land management has come<br />

to greater prominence. For example, the UN Convention to Combat Desertification explicitly recognizes the important<br />

role of community participation in sustainable land management and the fight against desertification. There is consensus<br />

now that local civil society groups and community-based organizations can provide a vehicle for local level experiences<br />

to contribute to an improved understanding of sustainable land management and to inform land management policies.<br />

What is required now is an effort to: i) identify and raise the profile of leading community-based sustainable land<br />

management solutions in Sub-Saharan Africa, ii) fill local capacity gaps, and iii) strengthen the voices of local and<br />

indigenous communities in a way that ensures that local civil society organizations contribute to the development<br />

of pro-poor, sustainable land management policies.<br />

In furtherance of this, the Equator Initiative partnership will lead a process to identify examples of local ingenuity,<br />

innovation and leadership in sustainable land management in Sub-Saharan Africa. Building on the experience of<br />

the Equator Prize, and working through its network of global partners, the Equator Initiative will recognize and<br />

raise the profile of community efforts to reduce poverty through sustainable land management. Themes of the<br />

prize are likely to include:<br />

• the integrated management of international river, lake and hydrogeological basins;<br />

• agroforestry and soil conservation;<br />

• rangelands use and fodder crops;<br />

• ecological monitoring, natural resource mapping, remote sensing, and early warning systems;<br />

• new and renewable energy sources and technologies;<br />

• sustainable agricultural farming systems.<br />

The process of selecting winners will be used to collect information to better understand how the interaction between<br />

policies, political processes and poverty reduction influences innovation and successful initiatives at the local level.<br />

Community-Based Sustainable Land Management: Best Practices in Drylands from the Equator Initiative<br />

4

Introduction<br />

OBSERVATIONS FROM EQUATOR PRIZE DRYLANDS CASES<br />

The case studies that follow—drawn from the pool of 152 Equator Prize winners since 2002—are offered as examples of<br />

the kind of ingenuity and grassroots leadership that can transform rural development in dryland environments. Each case<br />

study is an example of community-based leadership in sustainable land management, each is from the African continent,<br />

and each tells the story of community innovation in addressing those social, environmental, and economic issues that are<br />

specific to dryland ecosystems. Readers may find it useful to consider the following observations and conclusions drawn<br />

from a review of this case material.<br />

1. Community-based approaches can be highly effective. Community-based approaches to drylands management<br />

are often at the cutting edge of efforts to promote adaptation to climate change, mitigate the risks of prolonged<br />

drought and destructive floods, address persistent land degradation trends, manage fresh water, and create viable<br />

economies in drylands communities.<br />

Community-based approaches are an organic expression of the power of decentralized natural resource governance. They<br />

have much to offer as a model for drylands management that can be sustained in the face of climate change and other<br />

environmental challenges. Because they grow out of community demand and rely on community investments of time<br />

and effort, they are often low-cost interventions that are well integrated into community social structures, and therefore<br />

can be sustained over time.<br />

For example, since it began its integrated program of sustainable land management in 2004, the village of Abrha Weatsbha<br />

in northern Ethiopia has moved from a community facing imminent resettlement due to soil degradation and lack of<br />

water access to a leading example of drylands restoration and climate change adaptation. Through a comprehensive<br />

program of tree-planting, terracing, construction of check dams, wells and water catchment ponds, and the extension<br />

of irrigation systems, village residents have recharged local aquifers, checked soil loss, and greatly increased water access<br />

and agricultural incomes. Villagers drive the design and implementation of all land management projects, including the<br />

enforcement of by-laws governing the fair distribution of potable water within the recovering watershed.<br />

It is worth noting that the social benefits of community-based approaches to drylands management figure prominently<br />

in their success, making these local initiatives much more than just an environmental remedy; indeed, they are a model<br />

for delivering the complete package of Millennium Development Goals and catalyzing sustainable development in rural<br />

dryland communities.<br />

The Maasai Wilderness Conservation Trust in Kenya’s Chyuli Hills region, for example, uses revenue from a successful<br />

ecotourism lodge to fund an array of conservation, education and healthcare programs that serve the Maasai of the Kuku<br />

Group Ranch. In addition to supporting a conservation department employing more than 100 local Maasai in various<br />

wildlife management programs, the Trust also supports 20 primary schools and a secondary school serving 7,000 students,<br />

as well as a system of local health dispensaries serving around 8,000 people.<br />

Community-based initiatives are also often best positioned to arbitrate and navigate the kinds of conflicts that emerge<br />

in dryland ecosystems, whether because of resource scarcity or the different needs and land management practices of<br />

pastoralist and farming communities. Indeed, many drylands ecosystems are plagued by resource conflicts between<br />

adjacent communities or tribal groups or among different resource users within a single community. Communal resource<br />

management initiatives offer a productive forum for grappling with and defusing or resolving such conflicts.<br />

For example, on the arid rangelands of the Marsabit area of northern Kenya, a number of different ethnic groups practice<br />

mobile pastoralism, sometimes vying for access to critical water sources. Pastoralist Integrated Support Programme<br />

(PISP), a local NGO, works to increase the number of water points that can provide safe and reliable water for livestock<br />

and people. Additional work to improve grazing management and to diversify the income stream of pastoralists has also<br />

helped to reduce pressure on natural resources and thereby lessen tensions between resource user groups. PISP’s success<br />

5 Community-Based Sustainable Land Management: Best Practices in Drylands from the Equator Initiative

Introduction<br />

in encouraging conflict resolution has opened up previously disputed areas for grazing, thus increasing the available<br />

resource base and further reducing social friction.<br />

2. Drylands problems often require collective action. Addressing large-scale problems like land degradation<br />

and water scarcity requires action at a watershed and landscape level. Such an ecosystem-level approach, in<br />

turn, requires collective action—the cooperation of many individual stakeholders to achieve a common goal.<br />

Community-led approaches are particularly suited to engendering collective action, and therefore facilitating ecosystembased<br />

interventions. The ability to pursue a common goal with a clear view of the costs and benefits, and the determination<br />

to take the action required, is one of the distinguishing characteristics of Equator Prize-winning communities.<br />

For example, facing degradation of their communal grazing area as well as conflicts between pastoralists and<br />

farmers within the community, residents of the village of Itoh in Cameroon’s Bamenda Highlands came together to<br />

adopt a new approach to grazing in the community. Community members established a “living fence” around the<br />

communal grazing area to restrict livestock movement, improved the diet of livestock by planting high-nutrition<br />

grasses, instituted a rotational grazing system to allow pasture recovery, installed a permanent water source<br />

for livestock, and planted 30,000 trees in and around the grazing area to increase vegetative cover in the water<br />

catchment area. The collective endeavor resulted in greater access to livestock forage and much reduced incursions<br />

of livestock on community agricultural lands, and therefore reduced resource conflicts within the community.<br />

3. Local institutions are key agents in community-based solutions. Local organizations—groups whose<br />

activities are directed and carried out by members who live in the affected community—are key to inspiring<br />

effective collective action, and therefore central to community-led efforts to manage drylands sustainably.<br />

Supporting the success of these local efforts requires recognizing the legitimacy of community organizations,<br />

understanding their lead role in community-based initiatives, and supporting their growth and maturation.<br />

Local groups such as farmer cooperatives, resource user groups, self-help groups, local NGOs, or other CBOs, are<br />

well-positioned to appreciate both the causes and consequences of environmental degradation and to understand<br />

local threats such as the poaching of land, timber, or wildlife resources, or unsustainable agricultural practices.<br />

Because they reflect community knowledge, values, and perspectives, these groups can interpret community<br />

demand for change and channel it into effective local action. They are in a position to enable and encourage<br />

participatory processes that fit the culture and communication style of the community. And they can often exact<br />

compliance with rules adopted by the community to regulate ecosystem use and restore ecosystem health.<br />

Community-Based Sustainable Land Management: Best Practices in Drylands from the Equator Initiative<br />

6

Introduction<br />

The community forest surrounding the village of Ando Kpomey in southwestern Togo, for example, was originally<br />

planted in 1973 as a buffer against bush fires, a proposal put forward by village elders. Since then, the community<br />

has established a forest management committee whose members are elected from the community and charged with<br />

regulating all forest uses and enforcing forest rules. More recently, the committee, which has grown into a respected<br />

local institution, has expanded its activities to include promotion of alternative livelihoods activities that aim to raise<br />

local incomes and reduce pressure on the forest.<br />

Local groups often draw heavily from traditional institutions, but may reflect the purposes, values, political<br />

organization, and governance of more modern social assemblages as well. This can give them both local legitimacy<br />

and the currency to meet modern threats.<br />

In Sudan’s Gedaref State, the NGO Zenab for Women in Devel opment, for example, has targeted women farmers—a<br />

previously neglected group—with agricultural extension services, seeds, farm equipment, and training to make their<br />

farming practices more sustainable in the arid environment, and to increase and diversify their income streams. The<br />

NGO also catalyzed the creation of a women’s farmers union to empower and organize women in agriculture.<br />

4. Community-based initiatives can be commercially successful. Community-based initiatives can be effective<br />

drivers of the local economy, bringing jobs and other economic benefits to impoverished dryland communities with<br />

few economic options. As such, they can become primary agents in the creation of an inclusive local green economy.<br />

Equator Prize winners have shown that it is possible to put together viable commercial models for sustainable<br />

ecosystem-based enterprises through a combination of innovation, local knowledge, and good partnerships.<br />

As one example, using a program of farm training and economic incentives, Comaco (Community Markets for Conservation)<br />

has brought organic farming techniques to some 40,000 farming households in Zambia’s Luangwa Valley, and connected<br />

them to a distribution network for the organic products they raise. Comaco purchases farm commodities raised to its<br />

organic standards, processes them, and markets them in urban supermarkets, guaranteeing its farmer members a good<br />

return on their efforts. As another example, Swazi Indigenous Products is a member-owned company in Lubombo,<br />

Swaziland that pays its members to produce seed oils which are then used as ingredients in skin care products. The Swazi<br />

Secrets line of skin care products is now marketed in 31 countries across five continents.<br />

These initiatives also frequently contribute community infrastructure such as improvements to water systems and<br />

sanitation, schools, and health clinics—all public goods that support local economic and social development.<br />

5. Large-scale extractive industries and land grabs threaten community-based initiatives. Resource<br />

management decisions such as the granting of timber or mining concessions, or even the creation of parks or<br />

forest reserves by central authorities, often work at cross purposes to the interests of community initiatives for<br />

better drylands management.<br />

The threat of losing control over local ecosystem resources can create considerable economic and environmental<br />

stresses in nearby communities and undermine the incentive to manage these resources sustainably. Security<br />

of land and resource tenure, then, is an essential dimension of investing in community-based leadership and<br />

innovation. The certainty that comes from tenure security is the basis of good governance of local resources.<br />

For example, when the government unilaterally designated the Soledo Forest in northern Tanzania as a Central<br />

Government Forest Reserve in 1993 without local consultation, it disenfranchised more than 50,000 forestdependent<br />

peoples in the 9 villages adjacent to the forest, and provoked an organized and effective resistance<br />

to the new arrangement. In response, a process of gradual devolution of forest management authority to local<br />

7 Community-Based Sustainable Land Management: Best Practices in Drylands from the Equator Initiative

Introduction<br />

communities began, ultimately resulting in the redesignation of Soledo as a Village Land Forest Reserve in 2007,<br />

with the responsibility for designing and enforcing sustainable forest management plans in the hands of local<br />

Village Environment Committees.<br />

6. Local initiatives are scalable and influential. Many community-based initiatives have achieved significant<br />

scale, becoming models with relevance well beyond the villages where they originated. One of the most organic<br />

and effective methods of scaling is peer-to-peer demonstration, where community groups themselves act as<br />

mentors and learning resources for other communities facing a similar array of drylands management concerns.<br />

When properly empowered and enabled, local initiatives can lead to the kind of scaling that creates landscapelevel<br />

change and transforms economies. Many community-based initiatives successfully scale-up to become the<br />

predominant governing bodies for entire ecosystems, wildlife corridors, and agricultural landscapes. This scaling<br />

phenomenon refutes the common but mistaken view that local solutions invariably remain small in scope and<br />

impact. They are often the foundation on which national progress towards development goals is built. When<br />

scaled effectively, landscape-level changes become possible, and improvements in watershed conditions and<br />

ecosystem productivity can be pursued at larger scales, with increasing benefit.<br />

Torra and N≠a Jaqna Conservancies, for example, are two of Namibia’s 50 community conservancies—communal<br />

lands where wildlife management authority has been devolved to local communities—now in existence in the<br />

nation’s arid northern and eastern regions. The number of community conservancies scaled up rapidly from 4 in<br />

1998 to 50 today as word spread of the economic and social benefits associated with conservancy status. Due<br />

to this rapid growth, conservancies now cover some 14% of Namibia’s land area, allowing wildlife populations<br />

to rebound over large areas, helping to preserve or restore large-scale migration patterns, and creating new<br />

economic opportunities through ecotourism to supplement meager incomes from dryland agriculture.<br />

As another example, from 1986 to 2004, the Shinyanga Soil Conservation Programme helped restore degraded<br />

woodlands in the Shinyanga region of northern Tanzania, in part by reviving an indigenous land management<br />

practice in which forest vegetation was preserved by communities in enclosures called “ngitili” for use as livestock<br />

fodder during the dry season. While only 600 ha of documented ngitili remained at the Programme’s inception,<br />

some 350,000 ha had been restored or created in over 800 villages by the Programme’s end in 2004, turning scrub<br />

wastelands into recovering woodlands.<br />

Community-Based Sustainable Land Management: Best Practices in Drylands from the Equator Initiative<br />

8

Introduction<br />

Many successful local initiatives have also achieved significant influence at the policymaking level, helping to drive<br />

adoption of enabling policies that allow communities to become more active agents in rural development.<br />

Successful collective management of community grasslands in the Guassa area of Menz in Ethiopia’s central<br />

highlands, for example, led the government to designate the area as a Community Conserved Area in 2008—a<br />

category of protection previously unavailable to Ethiopian communities, but now legally recognized due to the<br />

Guassa experience.<br />

7. Partnerships are essential. While community groups must drive local action, they cannot act alone. Effective<br />

partnerships are essential to build local capacities, supply appropriate technologies and practices, help<br />

connect local supply-chains to national and international markets, and to help communities tap the funding<br />

and support they need to pursue their initiatives.<br />

A variety of partners with different capabilities are often needed, and Equator Prize-winning communities in<br />

drylands typically work with a range of institutions including NGOs, private companies, universities and research<br />

institutes, and government agencies. Successful partners respect the lead role and autonomy of local groups,<br />

while providing unique inputs, services, contacts, learning experiences, and grants tailored to the needs of the<br />

local group.<br />

The Shompole Community Trust, for example, which operates successful ecotourism lodges in southern Kenya<br />

to generate funds for conservation, health, and educational services, has a complement of seven partners. For<br />

example, the African Conservation Centre has helped to monitor wildlife numbers and train Trust employees in field<br />

research techniques, while the Kenya Wildlife Service has trained community game scouts. Meanwhile, two private<br />

sector partners manage the marketing and operation of the Trust’s ecotourism ventures. Grants from the European<br />

Union Community Trust Fund helped finance construction and progressive improvement of the Trust’s ecotourism<br />

infrastructure. These on-going partnerships have helped make the Trust’s ecotourism operations a profit center able<br />

to fund the Trust’s work.<br />

Governments are essential partners too, although the relationship between local groups and government requires<br />

careful tending if the focus of decision-making is to remain with the community. Many Equator Prize-winning<br />

communities have forged productive partnerships with governments by demonstrating their competency as land<br />

stewards and their ability to achieve local development goals.<br />

For example, the St. Catherine Medical Plants Association in the southern Sinai of Egypt was conceived and<br />

nurtured by Egypt’s Environmental Affairs Agency as a way to support local livelihoods, particularly among the<br />

area’s Bedouin women. Government personnel have been instrumental in helping the community to establish<br />

protocols for medicinal plant collection and to establish markets for both medicinal plants and alternative products<br />

such as honey and handicrafts. The governor of South Sinai also provides a building to house the association and<br />

its activities. In spite of this close and continuing relationship with government, all components of the initiative<br />

are owned by the community, and community members govern the association and its activities through its Board<br />

of Directors. The autonomy of the association is further enhanced by the fact that it relies on its own incomegenerating<br />

activities to fund its work.<br />

9 Community-Based Sustainable Land Management: Best Practices in Drylands from the Equator Initiative

CASE STUDIES<br />

Community-Based Sustainable Land Management: Best Practices in Drylands from the Equator Initiative<br />

10

ABRHA WEATSBHA<br />

COMMUNITY<br />

Ethiopia<br />

PROJECT SUMMARY<br />

English l Amharic l Tigrinya<br />

Once on the brink of resettlement due to desertification, soil degradation and lack<br />

of water, the Abrha Weatsbha community in northern Ethiopia has reclaimed its land<br />

through the reforestation and sustainable management of over 224,000 hectares of<br />

forest. Tree planting activities have resulted in improved soil quality, higher crop yields,<br />

increased biomass production and groundwater functioning, and flood prevention. The<br />

organization has constructed small dams, created water catchment ponds, and built<br />

trenches and bunds to restore groundwater functioning. More than 180 wells have<br />

been built to provide access to potable water.<br />

Environmental recovery and rejuvenation have led to improvements in local livelihoods<br />

through crop irrigation, fruit tree propagation and expansion into supplementary<br />

activities like apiculture. Local incomes have increased and food security and nutrition<br />

have improved through the integration of high-value fruit trees into farms.

Background and Context<br />

The Tigray region of Ethiopia is located in the northernmost territory of<br />

the country and borders Eritrea in the north, Sudan in the west, Afar in<br />

the east and Amhara in the southwest. The region is characterized by<br />

drylands and is highly vulnerable to recurrent drought. In the region,<br />

as well as across the country, land degradation is one of the most<br />

serious challenges confronting the rural population; it is exacerbated<br />

by climate change, and brings with it cross-cutting socioeconomic<br />

and environmental issues. In rural areas, where local economies and<br />

livelihoods depend on soil productivity for agriculture – teff, sorghum,<br />

wheat and maize, but also include sesame, horse bean, lentil, cotton<br />

and various spices – the implications for food security are particularly<br />

severe.<br />

magnified the vulnerability of the resident communities to climate<br />

impacts. In large sections, land had become barren, with bare rock<br />

predominating on the slopes surrounding the village. The impacts<br />

on local livelihoods and food security were devastating. By the early<br />

2000s, conditions had become so dire that the community faced<br />

resettlement.<br />

Micro-catchment ecosystem management<br />

Meanwhile, in 1996, the Ministry of Agroculture and Rural Development<br />

in Ethiopia undertook a process of decentralization, working more closely<br />

Drought, deforestation and land degradation<br />

The topography of Tigray makes it acutely vulnerable to the negative<br />

impacts of climate change and climate variability. Increasingly in<br />

recent years, northern Ethiopia has experienced serious droughts<br />

and inconsistent rainfall patterns, including rain coming much later<br />

in the season and insufficient rainfall during what has historically<br />

been the wet season. This variability, and the impacts it has had on<br />

landscape level agricultural production and local livelihoods, has<br />

been further exacerbated by deforestation. The northern regions<br />

of Ethiopia are among the most deforested in the country. Without<br />

the protection of the forest and vegetation cover, hillside soils<br />

become easily degraded. Additional drivers of land degradation<br />

have included unsustainable agricultural practices like free-range<br />

grazing, which prevents the growth of natural vegetation and allows<br />

the exposed layer of productive topsoil to be washed away during<br />

heavy rains.<br />

The village of Abrha Weatsbha, located in Tigray, is situated in a<br />

sandstone area that was particularly vulnerable to soil erosion<br />

and desertification. Land degradation had severely impacted the<br />

productivity of the village and surrounding agricultural lands.<br />

Poor, short-sighted land and water management approaches<br />

12

with community-based and grassroots initiatives to implement locally<br />

managed solutions to land, natural resource and water issues. Among<br />

the approaches promoted was a community-based ‘micro-catchment<br />

ecosystem management’ model. The strategy aimed to empower local<br />

communities to reach consensus on actions needed to stop free-range<br />

livestock grazing and mapping the options open to them, including:<br />

cutting and carrying grass to feed livestock, terracing hillsides to<br />

prevent erosion, damming gullies, and ensuring that any transgressors<br />

of established community by-laws were penalized. The approach has<br />

had its fair share of success: soil and water conservation activities have<br />

been carried out on more than 956,000 hectares of land throughout the<br />

country; vegetation enclosure management is being implemented on<br />

more than 1.2 million hectares of land; and there are more than 224,000<br />

hectares of land under sustainable forest management. The microcatchment<br />

ecosystem management model has resulted in the planting<br />

of over 40 million tree seedlings (with a 56 per cent survival rate) and the<br />

building of 180 wells that provide needed access to potable water.<br />

Though Abrha Weatsbha was not one of the four communities selected<br />

for the piloting of the ‘micro-catchment ecosystem management’<br />

model, Abrha Weatsbha Natural Resource Management Initiative was<br />

founded in this context and based its approach on lessons learned<br />

from the successes and obstacles faced in carrying out this strategy.<br />

One important transplant from the ‘micro-catchment ecosystem<br />

management’ model was enlisting the guidance and support of the<br />

Ministry of Agriculture’s extension system – one of the largest and most<br />

robust of its kind in the world, with development agents working in<br />

farmer training centres across all regions of the country. Most of these<br />

extension agents focus on knowledge management and technical<br />

capacity building for smallholder farmers and pastoralists with a view<br />

to improving the overall sustainability and productivity of small farms.<br />

Community-based adaptation to climate change<br />

In 2004, the Abrha Weatsbha Natural Resource Management<br />

Initiative was formed to address the challenges of food insecurity,<br />

land degradation, and access to fresh water. It has since emerged<br />

as a leading example of community-based adaptation to climate<br />

change. The initiative began with a community assessment of<br />

existing constraints to local health and wellbeing, with special<br />

consideration for challenges arising due to climate change and<br />

environmental decline. Despite the presence of a local aquifer, one<br />

of the top priorities identified was fresh water access.<br />

Through this grassroots enterprise, the community has initiated a<br />

range of actions to address land degradation and lack of water access,<br />

both of which have plagued local residents and threatened local<br />

livelihoods and wellbeing. Some of the most effective interventions<br />

have included a comprehensive tree-planting campaign; the<br />

construction of dams, wells and water catchments ponds, which<br />

allow the community to exercise more control and secure greater<br />

certainty over the availability of fresh water; and the establishment<br />

of temporary closed areas on communal land, where grazing is<br />

prohibited to allow for the natural regeneration of indigenous<br />

vegetation.<br />

Landscape level change<br />

The result has been nothing short of landscape level change; that<br />

is, the wholesale transformation of lands surrounding the village<br />

and rejuvenation of the catchment area. Vegetation cover has<br />

quickly returned, soil erosion has been greatly reduced, rain water<br />

infiltration into the subsoil has increased (which, by extension,<br />

improved agricultural productivity), and springs and streams have<br />

been fortified. The community is using hand-dug, shallow water<br />

wells to start small-scale irrigation schemes. Livestock management<br />

and domestic animal production has improved, with animal dung<br />

used for compost and improving soil fertility. With environmental<br />

recovery and the rejuvenation of local ecosystems has come<br />

improved livelihoods, diversified incomes and strengthened food<br />

security. To date, more than 1,000 farmers have been engaged in<br />

these new agronomic practices and diversified income generation<br />

activities, with thousands more benefiting from ecosystem<br />

restoration and improvements to local infrastructure.<br />

The village has become widely known for its pioneering work on<br />

‘community-based participatory planning’, which prioritizes the<br />

active involvement of the local population in each step of project<br />

design, development and implementation. Responsiveness to<br />

local needs, and the ability to draw from local resources, are stated<br />

strengths of the Abrha Weatsbha Natural Resource Management<br />

Initiative and key factors underpinning its success to date. A<br />

community-based management system ensures the buy-in of<br />

the local community, while specific mechanisms have also been<br />

put in place to ensure the inclusion of women in all aspects of<br />

community planning, project implementation and monitoring. Bylaws<br />

governing the fair distribution of potable water are enforced<br />

by a village committee, which also serves as a dispute resolution<br />

mechanism and actively monitors water use.<br />

13

Key Activities and Innovations<br />

The community of Abrha Weatsbha carries out a number of<br />

overlapping and complementary activities in the areas of communitybased<br />

adaptation, food security, eco-agriculture, sustainable forest<br />

management, sustainable land management, and water resource<br />

management.<br />

Improved water management<br />

Northern Ethiopia typically experiences unreliable rainfall. These<br />

patterns have only intensified with climate change, resulting in<br />

prolonged droughts, late rains, shorter rainy seasons, and extended<br />

dry spells during the growing season. This poses acute challenges<br />

for a population that is dependent on agriculture for subsistence,<br />

food security and livelihoods. Abrha Weatsbha has responded with<br />

interventions to improve the water-holding capacity of the soil by<br />

recharging groundwater and digging shallow wells to provide for<br />

supplementary irrigation.<br />

Changing local agricultural practices<br />

Abrha Weatsbha Natural Resource Management Initiative also<br />

engages local farmers to improve environmental sustainability, crop<br />

yields and agricultural productivity. This has been an exercise in<br />

behaviour change, as some traditional agricultural practices – many<br />

in use due to the need for quick, low-cost returns – have produced<br />

negative impacts on the local environment. The group promotes<br />

Improvements to the integrity and content of soil have led to<br />

subsequent improvements in water-holding capacity. Tree planting,<br />

ecosystem restoration activities, and the use of manure for compost<br />

and organic fertilizers have not only improved the integrity of the soil<br />

and land, but improved water security by facilitating groundwater<br />

recharge, or what community members refer to as “the water bank in<br />

the soil”. This reserve of water has increased community resilience to<br />

droughts. Improvements in soil quality have translated to increased<br />

absorption of water into the soil, which has also reduced incidence<br />

of flooding.<br />

The community also constructs small dams, creates water catchment<br />

ponds, and builds trenches and bunds to restore groundwater<br />

functioning. This has resulted in greater flexibility with irrigation,<br />

making year-round agricultural production possible and allowing<br />

local farmers to grow fruits and vegetables that were previously<br />

untenable during the dry season.<br />

14

the selection of crop and livestock varieties that are well matched to<br />

the carrying capacity of the land. Grazing restrictions have also been<br />

enforced to allow for the regeneration of indigenous vegetation.<br />

Additionally, the group works with private land owners to encourage<br />

agroforestry practices, which provide the community with wood<br />

and non-timber forest products and also fill important environment<br />

functions like climate control and nitrogen fixing, nutrient cycling, soil<br />

enrichment, and water percolation. At the same time, shallow wells<br />

have been dug to allow for both standard and drip irrigation, which<br />

make it possible to grow fruit and vegetables during the dry season.<br />

Tree planting and agroforestry<br />

The Abrha Weatsbha community is working to reverse the legacy of<br />

deforestation in the region. Tree-planting efforts on communal lands<br />

have been undertaken with the long-term goal of re-establishing<br />

standing forests and improving soil quality and integrity. On a<br />

shorter term basis, the community has focused on temporary<br />

closures of communal areas where the land needs time to recover<br />

and rehabilitate, soil and water conservation interventions, and<br />

community woodlots. The communal lands are dominated primarily<br />

by pioneer indigenous species, which have low production function,<br />

but high environmental rehabilitation and stabilization functions.<br />

Thus, the group has also promoted the use of farm fields and<br />

backyards for agroforestry and the planting of fruit-bearing trees,<br />

which have positive environmental and economic benefits for<br />

participating farmers.<br />

Education, local problem-solving and innovation<br />

In addition to its land restoration and conservation activities, Abrha<br />

Weatsbha has dedicated energy and resources to community<br />

education and training for the local population. The local authority<br />

in the village works to promote a multi-dimensional extension<br />

programme that is responsive to the production needs of residents<br />

in particular regions, and has made significant strides in reaching<br />

populations of economically marginalized women to offer support<br />

and skills-training in livestock production, forestry, soil conservation,<br />

agriculture and horticulture.<br />

This commitment to education and training has had positive<br />

spillover effects for the community by providing a sense of shared<br />

determination, collective problem-solving and local self-reliance.<br />

As a result, a local culture and ethos of innovation has blossomed.<br />

By encouraging learning by doing, building trust between local<br />

authorities and farmers, facilitating calculated risk-taking, and<br />

investing in interventions that respond to locally identified needs,<br />

Abrha Weatsbha Natural Resource Management Initiative has built a<br />

foundation of social capital that can be drawn from in tackling other<br />

challenges to the village and equitably managing complex social<br />

issues such as land allocation, resource sharing in grazing lands and<br />

protected forests, expansion of irrigation channels to remote subdistricts,<br />

and dealing with internal conflicts and benefit-sharing.<br />

15

Impacts<br />

BIODIVERSITY IMPACTS<br />

Abrha Weatsbha’s Natural Resource Management Initiative has had a<br />

number of positive biodiversity impacts in the land surrounding the<br />

village and in the region more broadly. Environmental rehabilitation<br />

efforts – the construction of dams, trenches and bunds, and chains of<br />

ponds for “water banking” – have had the desired effect of recharging<br />

the ground water and improving the integrity and composition of the<br />

soil, two challenges which had long been plaguing the community<br />

and crippling the health of local ecosystems.<br />

Recharging groundwater<br />

Rehabilitation efforts, along with a wide-ranging tree planting<br />

campaign, have resulted in more than 50 per cent of rainwater being<br />

trapped to recharge groundwater stores. Wells have been dug for<br />

irrigation of high-value crops, which are now able to be harvested<br />

two to three times per year, irrespective of rainfall patterns. The<br />

creation of enclosure areas and water conservation measures have<br />

resulted in water tables rising from nine meters depth to between<br />

two and four meters, making the digging of wells a reasonably lowlabour<br />

and low-cost proposition. Natural springs that had dried<br />

up have started to flow again, streams now flow longer distances,<br />

and pastured lowlands remain green throughout the year. The<br />

environmental benefits of soil conservation, water infiltration<br />

and groundwater recharge have translated to socioeconomic<br />

benefits that include higher crop yields, improvements in biomass<br />

production, and reduced incidence of flooding.<br />

example, where farmers used to purposefully remove Faidherbia<br />

albida trees – a thorny species of tree with deep-penetrating tap<br />

roots that make it highly resistant to drought – it has become<br />

common practice to sow their seeds and germinate them in their<br />

fields. Another example of positive behavior change among local<br />

farmers has been the voluntary introduction of seasonal land<br />

closures, where human and livestock incursions are restricted to<br />

allow land in certain areas to recover.<br />

A sustainable land management approach<br />

One of the main areas of focus for the initiative has been tree planting,<br />

efforts which have targeted hillside areas and degraded lands in and<br />

around the village. These investments in tree planting have paid<br />

large environment dividends. Reforestation has translated to the<br />

conservation of topsoil, greater cycling of organic material to the<br />

soil, watershed protection and reduced erosion of hillsides, which<br />

A “quiet revolution”<br />

Abrha Weatsbha Natural Resource Management Initiative has<br />

successfully ushered in a local paradigm shift – what the group<br />

has dubbed a “quiet revolution” – in how local farmers understand,<br />

appreciate and manage the environment. One aspect of this<br />

appreciation has been around indigenous species of plants. For<br />

16

was leaving large tracks of potentially productive land barren. Tree<br />

root systems have served to strengthen soil integrity and cohesion,<br />

reducing the erosion of slopes.<br />

The sustainable land management approach promoted by the<br />

group has served as a mechanism for doing away with local<br />

agricultural practices that were either not sustainable over the long<br />

term or, worse, were eroding the integrity of local ecosystems and<br />

damaging the environment. A focus on the interconnectedness of<br />

groundwater recharge, soil quality, and tree cover has provided a<br />

lens and rallying point through which the community has been able<br />

to address environmental challenges at the systemic level. The end<br />

result has been greater environmental sustainability and improved<br />

land productivity.<br />

SOCIOECONOMIC IMPACTS<br />

The initiative has had a profound impact on the livelihoods of Abrha<br />

Weatsbha community members, improving food security to such<br />

an extent that an area once plagued by low crop yields and food<br />

shortages in the dry season now produces a food surplus. Similar<br />

improvements have come about in the availability of potable water,<br />

once a serious concern which threatened local health and wellbeing<br />

as well as the irrigation options for off-season agriculture. The<br />

availability of water has combined with improvements in soil quality<br />

to boost agricultural outputs and the diversity of crops that can be<br />

grown throughout the year. Farmers have also been supported to<br />

better select and maintain livestock in their respective landscapes,<br />

which has not only improved the productivity of livestock, but<br />

reduced overgrazing and resulting land degradation.<br />

Access to water, irrigation and food security<br />

By focusing on recharging the groundwater and local aquifer,<br />

Abrha Weatsbha Natural Resource Management Initiative has made<br />

possible the use of shallow wells. Prior to the group’s interventions,<br />

the water table was too low for communities to access it. Now, with a<br />

minimal amount of technological input, the village has been able to<br />

dig more than 180 wells using treadle pumps to access potable water.<br />

Treadle pumps are now also used by the local population to access<br />

water from ponds, springs and the nearby river, all strengthening<br />

local water security.<br />

Access to water has made irrigation during the dry season and<br />

supplementary irrigation during the rainy season possible, creating<br />

reliable year-round agricultural production. In the dryland region<br />

of northern Ethiopia, where rain-fed crop production is possible<br />

only once a year, this newfound ability to produce crops, fruits and<br />

vegetables year-round has fundamentally changed the area and the<br />

lives of the local population. For the average shallow wells user, food<br />

self-sufficiency is now possible for over nine months of the year,<br />

while for 27 per cent of users food self-sufficiency is possible yearround.<br />

The new possibilities which have opened up through water<br />

17

security and irrigation have also had implications for local health<br />

and nutrition. A total of 39 per cent of shallow well users are now<br />

consuming a wider variety of vegetables at least once a week.<br />

Agricultural outputs, diversified crops and local income<br />

Between 2004 and 2007, the amount of irrigated land under<br />

cultivation for vegetable production increased from 32 to 68<br />

hectares. This has had predictably positive effects on local incomes.<br />

Between 2007 and 2010, when land under irrigation expanded<br />

further, incomes from the sale of vegetables and spices nearly<br />

tripled from USD 32,500 to USD 93,750. Farmers have also been<br />

supported to grow high-value fruit trees for apple, avocado, citron,<br />

mango, and coffee, several of which were not part of the agricultural<br />

landscape prior to when the initiative began. Cultivation of fruit<br />

trees has enhanced both incomes and nutrition. The group has also<br />

promoted apiculture as an income diversification strategy for local<br />

farmers. Training in modern beehive management and the use of<br />

apiculture equipment led to a local increase in honey production<br />

between 2007 and 2010 from 13 to 31 tons, as well as an increase in<br />

hive productivity from 10 to 35 kilograms.<br />

Incomes have also increased from the sale of surplus produce.<br />

Notably, the group has coordinated the pooling of funds to link<br />

the community into an electricity grid which is 15 kilometres away.<br />

Access to energy has been a persistent problem for the village, but<br />

now more than 60 per cent of households have access to this grid.<br />

This “common fund” approach has also been used to construct,<br />

equip and light a community centre, which has become an engine<br />

of local collective action and information exchange.<br />

Resilience<br />

One of the most significant impacts of the project has been<br />

improvements in the overall resilience of the community to withstand<br />

environmental and economic shocks and, importantly, to adapt to<br />

climate change in a region known for extreme climate variability. The<br />

sustainable land management approach employed by the initiative<br />

has improved soil quality and integrity, which has in turn reduced<br />

the susceptibility of the community to floods and further land<br />

degradation. Efforts to improve food security and diversify the base<br />

of agricultural products have created less dependence on a single or<br />

small number of crops, thereby strengthening income certainty for<br />

local farmers who regularly confront extended droughts.<br />

Empowerment of women<br />

The development of potable water sources within the village, and<br />

the establishment of enclosed woodlots in the village vicinity, have<br />

had important implications for women and girls. Where previously<br />

women would have travelled great distances to collect water, fodder<br />

and firewood, they now are able to access these basic needs in a<br />

much shorter amount of time. This has had the effect of freeing up<br />

time for women and girls to engage in other productive activities,<br />

including school and education. Women have also been given<br />

an active role in the governance of the initiative, taking a lead on<br />

decision-making and implementation of the programme.<br />

POLICY IMPACTS<br />

The organization has had an important role in shaping regional<br />

policy development and has garnered the attention of regional<br />

and national policymakers. Lessons learned from the initiative have<br />

been channelled into a regional steering committee established<br />

by the Tigray regional government, the Bureau of Water Resources<br />

Development, and the Relief Society of Tigray. Based on an<br />

innovation that came out of the Abrha Weatsbha Natural Resource<br />

Management Initiative, the committee decided to adopt the use of<br />

ponds as irrigation sources, and to make the technical and resource<br />

investments needed to implement the approach across the region.<br />

This became the first step in a process that saw many local farmers in<br />

the region adopting shallow wells and other locally adapted waterharvesting<br />

strategies.<br />

Data collected from the extension office in Abrha Weatsbha<br />

indicated that shallow wells have been the technology most widely<br />

used by farmers, accounting for 57.5 per cent of the total land under<br />

irrigation. According to the respondents of a survey taken at the<br />

regional level, the success of this approach in Abrha Weatsbha has<br />

also positively influenced regional strategies for household-level<br />

irrigation. While the main strategy promotes ponds, different waterharvesting<br />

alternatives from Abrha Weatsbha such as shallow wells,<br />

underground tanks and pump irrigation have been accepted as<br />

important components of the regional strategy.<br />

Abrha Weatsbha Natural Resource Management Initiative also<br />

serves as a training centre for farmers across the region and a<br />

model for community-based natural resource management where<br />

local practitioners can experience their techniques first-hand.<br />

Researchers from national universities and institutes often visit the<br />

group to study their sustainable land management approach and<br />

better understand what has made their initiative a success.<br />

18

Sustainability and Replication<br />

SUSTAINABILITY<br />

Although the Abrha Weatsbha Natural Resource Management<br />

Initiative has received support from the government, its ongoing<br />

work has largely been the by-product of community energy,<br />

resources and labour. As such, while the organization is not reliant on<br />

outside inputs to continue operating, its sustainability model is tied<br />

closely to its ability to foster community ownership and investment.<br />

The initiative has become deeply embedded into local life, culture<br />

and identity. All interventions have been implemented using locally<br />

available resources. The group is governed by a locally-elected<br />

administrative body and all produce is targeted to local markets.<br />

Self-sustainability and self-reliance are defining characteristics of<br />

the organization, as well as important aspects of local identity. The<br />

combination of both short and long-term benefits provides ongoing<br />

incentives to the local people, who can see visible results for the<br />

efforts they invest.<br />

REPLICATION<br />

Through a partnership with nearby Mekelle University, the recently<br />

established Abrha Weatsbha Knowledge Management Centre<br />

has been set up to facilitate the sharing of lessons learned both<br />

within the village and between Abrha Weatsbha and other villages,<br />

allowing the successes achieved in Abrha Weatsbha to be shared<br />

with and replicated by other communities in the region that face<br />

similar challenges from climate variability and land degradation. The<br />

knowledge management centre serves as a powerful instrument for<br />

facilitating the replication of Abrha Weatsbha’s successes throughout<br />

the region and beyond. There is also a demonstration site in the<br />

village for testing new methods of natural resource management.<br />

Several senior regional and federal government officials, including<br />

the Ethiopian Prime Minister, have visited Abrha Weatsbha and<br />

expressed their appreciation for the development activities taking<br />

place there. The government’s recognition of the village as a model<br />

for community adaptation and development has influenced many<br />

others to visit and participate in knowledge-sharing with the<br />

community.<br />

PARTNERS<br />

The initiative has benefitted from a diverse array of partnerships,<br />

including with Mekelle University, various government offices<br />

in the village (specifically the food security programme), credit<br />

institutions, and cooperatives. Mekelle University partnered with the<br />

initiative to establish the Abrha Weatsbha Knowledge Management<br />

Centre, which also provides skills-training and workshops on<br />

communications technology. Additionally, the Tigray Bureau of<br />

Agriculture and the Relief Society of Tigray provided technical and<br />

resource inputs to the initiative, while the Ministry of Agriculture’s<br />

extension system has provided ongoing guidance and support.<br />

19

AMSING ASSOCIATION<br />

Morocco<br />

PROJECT SUMMARY<br />

English l Arabic<br />

Amsing Association was eatsbalished by the villagers of Elmoudaa – an Amazirght<br />

(Berber) community located in the High Atlas Mountains – to address economic<br />

isolation, a lack of social services, and harsh climatic conditions. The association has<br />

successfullyreintroduced a traditional land management practice called ‘azzayn’ which<br />

bans herders from grazing their livestock on protected lands. The reintroduction of<br />

this regulatory system has allowed native grasses and shrubs to thrive, reduced soil<br />

erosion, and helped prevent flooding.<br />

The association has also led a number of infrastructure projects to promote communitybased<br />

adaptation to climate change. A ‘water chateau’ stores fresh water for use in<br />

times of drought or when floods wash away irrigation ditches, while a water tower<br />

provides local residents with access to clean drinking water. In addition to upgrading<br />

the community irrigation system, the association has expanded greenhouse farming to<br />

explore new crops and improve food security.

Background and Context<br />

Douar Elmoudaa is a traditional Amazirght (Berber) village and<br />

community, located on the southern slopes of the High Atlas<br />

Mountains in Toubkal National Park, Morocco. One of 45 douars, or<br />

villages, of the Rural Commune of Toubkal, Elmoudaa is located in<br />

the Tifnout valley, roughly 20 km south-east of Mount Toubkal, the<br />

highest mountain in North Africa. The village is located in one of the<br />

most remote areas of Morocco, within the province of Taroudant, in<br />

the Souss-Massa-Drâa region. At an altitude of 2,000 m and accessed<br />

via 30 km of unpaved road, the village is extremely isolated.<br />

Elmoudaa is the home of a Berber community, indigenous to the<br />

region, and the village’s history can be traced back over 2,000 years.<br />

The community currently consists of 350 people distributed in 28<br />

households. Adult men and women make up 35 per cent of the<br />

population (15 and 20 per cent respectively) with children younger<br />

than 13 years of age comprising the majority of the remainder.<br />

The community members traditionally rely on natural resources<br />

for their livelihoods, with forestry, cattle-breeding and small-scale<br />

or subsistence farming dominating. Wheat, barley, corn, potatoes,<br />

onions, and seasonal fruit are grown and are either consumed<br />

directly or sold for income.<br />

Men are primarily responsible for physical labor including plowing<br />

and sowing fields, irrigation, and transporting and processing crops.<br />

Many men also earn income through construction and occasional<br />

work in larger cities. Women and children are responsible for the<br />

majority of field work, including harvesting, maintenance and<br />

caring for livestock. They are also the primary caretakers of natural<br />

resources, since tasks like fetching water and collecting wood<br />

typically fall to them.<br />

Impacts of a changing climate<br />

The baseline climate of Elmoudaa is very specific to the Toubkal<br />

region, with a combination of Mediterranean and steppe climates.<br />

There are wide seasonal fluctuations in the weather, with the local<br />

climate historically characterized by a hot, dry summer lasting<br />

from April until October, and an extremely cold, humid winter<br />

lasting from November until March. However, in the recent past,<br />

the community has observed changes in weather patterns, with<br />

higher temperatures, less snowfall during winter months, and more<br />

unpredictable and violent storms. Extended drought periods are<br />

considered cyclical by most locals, coming at five-year intervals and<br />

lasting for two years. The general assumption is that two years of<br />

drought will be followed by three years of moderate precipitation.<br />

There has, however, been a noticeable disruption to this cycle, with<br />

drought periods extending beyond their two year averages while<br />

producing less rain and more heat than expected. Extreme weather<br />

events are increasingly unpredictable and more intense, and their<br />

impacts are only exacerbated by damage from intense drought<br />

years.<br />

Reduced precipitation in winter has contributed to a decrease in<br />

local water resources (snow historically provided water reserves<br />

for the spring), while storms and sudden melting of snow (due to<br />

increased temperature variability) has led to sudden, devastating<br />

water flows and flooding.<br />

Flooding is the most immediate and visible impact of this climate<br />

variability, resulting in erosion and damage to local infrastructure<br />

and agriculture. Traditionally, seasonal and consistent rains provided<br />

sufficient vegetation and soil compaction to support baselines<br />

structures such as irrigation, access roads and fields. Lengthening<br />

periods of drought followed by short yet violent storms reduce the<br />