A history of Italian tiles - Infotile

A history of Italian tiles - Infotile

A history of Italian tiles - Infotile

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

figure B<br />

artistic were, in part, such that as<br />

the population fell demand for labour<br />

stabilised and inflation became<br />

minimal, which led to increased wages<br />

and a broader based social prosperity.<br />

Naturally, art historians have sought a<br />

link between this devastating event<br />

and ensuing artistic developments.<br />

Two theories that have emerged in<br />

the last few decades deserve some<br />

attention. The first presents the theory<br />

that the plague and the social chaos<br />

that followed resulted in a rejection <strong>of</strong><br />

the avant-garde naturalism <strong>of</strong> Giotto<br />

and his disciples in the early 14th<br />

century and a return to an earlier, more<br />

traditional form, exhibiting spiritual,<br />

iconic images. However, another<br />

historian has argued that the increase<br />

in conventional pictorial styles could be<br />

explained by the expanding market for<br />

devotional artwork sought by emerging<br />

social groups who had hitherto been<br />

unable to afford them or disinclined to<br />

want them. Consequently workshop<br />

production became more organised<br />

and sophisticated, but as prices fell<br />

so too did the quality. Only during the<br />

early part <strong>of</strong> the quarttrocento did a<br />

smaller or more discriminating group <strong>of</strong><br />

patrons express a taste for expensive<br />

and innovative works <strong>of</strong> art.<br />

Perhaps the most definitive portrait we<br />

have <strong>of</strong> a member <strong>of</strong> this emergent<br />

social group is provided by the letters<br />

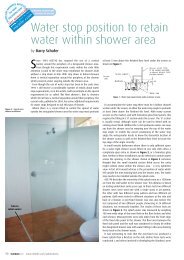

figure C<br />

figure C. Hexagonal maiolica floor<br />

tile, circa 1465, from the<br />

duomo at capua. it shows<br />

a craftsman at work.<br />

<strong>of</strong> the wealthy 14th century merchant<br />

Francesco Datini, published in The<br />

Merchant <strong>of</strong> Prato by Iris Origo. In<br />

1358 Datini, who had planned his<br />

house for many years, bought land in<br />

Prato, but progress was very slow. It<br />

was 1388 before the upstairs loggia<br />

was nearing completion. By summer<br />

the inner walls were plastered and the<br />

brick floors were being laid.<br />

An inventory drawn up in 1407<br />

described it as “a large and handsome<br />

house... with a court and loggia and a<br />

cellar, all painted and fine,” and set its<br />

value at 1,000 florims. All Francesco’s<br />

downstairs rooms had vaulted ceilings<br />

- some <strong>of</strong> them painted - and “brick<br />

floors, carefully polished and waxed.”<br />

In this period the division between<br />

what we class the fine arts and the<br />

decorative arts did not exist. If anything<br />

the latter took precedence over the<br />

former and to draw a firm distinction<br />

between artists and artisans, or<br />

between high art and craft, will miss<br />

the true nature <strong>of</strong> both. For example,<br />

we now know that Sandro Botticelli’s<br />

painting <strong>of</strong> the ‘Primavera’ was once<br />

part <strong>of</strong> a freestanding or day-bed.<br />

At about this point Bodkin returns<br />

to the issue <strong>of</strong> a reaction to Giotto’s<br />

naturalism which he had noticed well<br />

before it was developed into a theory.<br />

He points out that in Naples and<br />

the north, where Giotto also worked,<br />

there was no discernable shift. Indeed<br />

his admiration for Giotto seems only<br />

slightly less than Vasari’s, whom he<br />

quotes here. “In my opinion painters<br />

owe to Giotto... exactly the same debt<br />

they owe to nature, which constantly<br />

serves them as a model and whose<br />

finest and most beautiful aspects<br />

they are always striving to imitate and<br />

reproduce.”<br />

Giotto (1266/7-1337) was apprenticed<br />

to Cimabue (1240-1302) and together<br />

they paved the way for the painters <strong>of</strong><br />

the Rinascimento. As Vasari puts it, “In<br />

this work [the fresco for the hospital<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Porcellana] Cimabue broke<br />

decisively with the dead tradition <strong>of</strong><br />

the Greeks, for whereas their paintings<br />

and mosaics were covered with heavy<br />

lines and contours, his draperies,<br />

vestments and other accessories were<br />

somewhat s<strong>of</strong>ter and more realistic<br />

and flowing.”<br />

In transactions with the artists who<br />

painted his house, we see Datini to<br />

be impatient and exacting and miserly<br />

when it came to pay. Almost all the<br />

orders for pictures from his branch<br />

<strong>of</strong>fice in Avignon specify the precise<br />

measurement required; the price <strong>of</strong> a<br />

picture largely depending on its actual<br />

size, and on the quality <strong>of</strong> the colours<br />

used.<br />

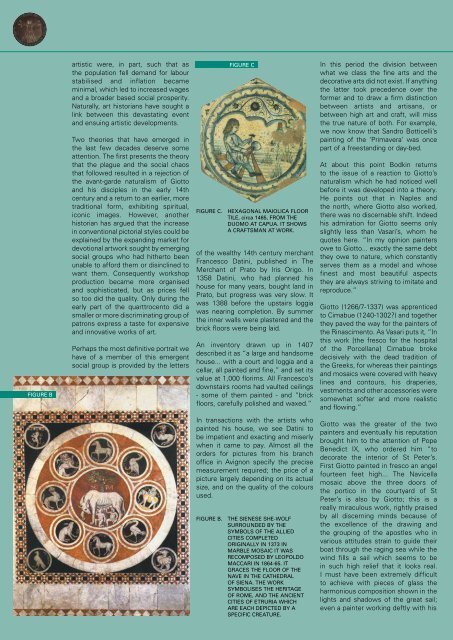

Figure B. the sienese she-wolf<br />

surrounded by the<br />

symbols <strong>of</strong> the allied<br />

cities completed<br />

originally in 1373 in<br />

marble mosaic it was<br />

recomposed by leopoldo<br />

maccari in 1864-65. it<br />

graces the floor <strong>of</strong> the<br />

nave in the cathedral<br />

<strong>of</strong> siena. the work<br />

symbolises the heritage<br />

<strong>of</strong> rome, and the ancient<br />

cities <strong>of</strong> etruria which<br />

are each depicted by a<br />

specific creature.<br />

Giotto was the greater <strong>of</strong> the two<br />

painters and eventually his reputation<br />

brought him to the attention <strong>of</strong> Pope<br />

Benedict IX, who ordered him “to<br />

decorate the interior <strong>of</strong> St Peter’s.<br />

First Giotto painted in fresco an angel<br />

fourteen feet high... The Navicella<br />

mosaic above the three doors <strong>of</strong><br />

the portico in the courtyard <strong>of</strong> St<br />

Peter’s is also by Giotto; this is a<br />

really miraculous work, rightly praised<br />

by all discerning minds because <strong>of</strong><br />

the excellence <strong>of</strong> the drawing and<br />

the grouping <strong>of</strong> the apostles who in<br />

various attitudes strain to guide their<br />

boat through the raging sea while the<br />

wind fills a sail which seems to be<br />

in such high relief that it looks real.<br />

I must have been extremely difficult<br />

to achieve with pieces <strong>of</strong> glass the<br />

harmonious composition shown in the<br />

lights and shadows <strong>of</strong> the great sail;<br />

even a painter working deftly with his