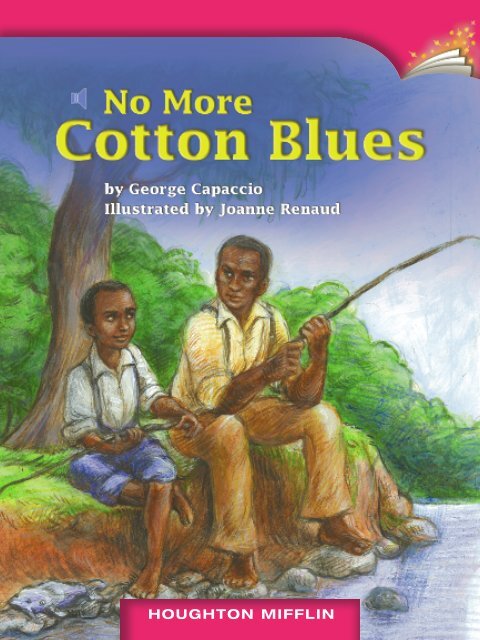

Lesson 23:No More Cotton Blues

Lesson 23:No More Cotton Blues

Lesson 23:No More Cotton Blues

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN

y George Capaccio<br />

Illustrated by Joanne Renaud<br />

Copyright © by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company<br />

All rights reserved. <strong>No</strong> part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or<br />

mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior<br />

written permission of the copyright owner unless such copying is expressly permitted by federal copyright law. Requests<br />

for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be addressed to Houghton Mifflin Harcourt School Publishers,<br />

Attn: Permissions, 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, Florida 32887-6777.<br />

Printed in China<br />

ISBN-13: 978-0-547-02198-0<br />

ISBN-10: 0-547-02198-4<br />

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 0940 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11<br />

If you have received these materials as examination copies free of charge, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt School Publishers<br />

retains title to the materials and they may not be resold. Resale of examination copies is strictly prohibited.<br />

Possession of this publication in print format does not entitle users to convert this publication, or any portion of it, into<br />

electronic format.

Looking Back<br />

I remember the day the war ended. My platoon had set<br />

up camp outside a small French village. We’d been hitting the<br />

Germans with everything we had. Then like that it was over.<br />

The German High Command had surrendered to the Allies.<br />

I knew I’d be going home with just a piece of shrapnel in<br />

my hand instead of all shot up like a lot of guys in my outfit.<br />

<strong>No</strong>w that’s a day I won’t ever forget — May 7, 1945.<br />

I’ve lived long enough to have plenty of memorable experiences.<br />

Some I’d just as soon forget — like back in the days<br />

of the panic crash. That’s what black folks called the Great<br />

Depression. Times were hard for everybody, but especially<br />

for blacks. In 1935, when I was only twelve, my family was<br />

sharecropping on a big cotton plantation right here in Georgia.<br />

Our farm was miles away from Atlanta, and my horizons were<br />

limited to how much cotton I could pick in the course of a day.<br />

I never dreamed my life would turn out the way it has.<br />

We lived in a run-down, two-room shack sitting on open<br />

farmland. The only plumbing we had was an outhouse and a<br />

wash basin. There was no electricity and no heating except for a<br />

wood-burning stove.<br />

My sister Ardell and I were in the fields from sunup to<br />

sundown every day of the harvest. My father had about twenty<br />

acres of good farmland. Of course, none of the land was his. It all<br />

belonged to Oliver Hopkins and his wife Charlene. They owned<br />

one of the biggest plantations in all of Jefferson County.<br />

2

There were twenty families sharecropping on the Hopkins’<br />

plantation, and all of them were black. In return for working the<br />

land, each family got a share of the money earned from selling<br />

the cotton crop minus their debt to the owner.<br />

In early spring, the plantation manager would start giving<br />

each family a monthly furnish of about fifteen dollars to cover<br />

expenses until the crop was in. About all it paid for was beans,<br />

bread, and some fatty cuts of meat. The furnish usually ran out<br />

before the end of the month. Then we’d have to shop on credit<br />

at the plantation store. One year we were so poor my mother<br />

had to make all our clothes out of old cotton sacks that she dyed<br />

with hickory bark.<br />

The cotton came up in October or <strong>No</strong>vember, depending<br />

on the weather. Once those white bolls started popping, our<br />

schooling was over until the last boll was picked and the whole<br />

crop was in. Whenever there was work to be done in the fields,<br />

the school would be closed.<br />

Standing My Ground<br />

I remember one day in the autumn of 1935. My mother<br />

and father were picking in the next field over. Ardell and I had<br />

already filled a couple of sacks apiece with cotton. Ardell’s<br />

back was hurting from dragging around a seventy-five-pound<br />

bag of cotton. She was strong, but the sun was fiercely hot.<br />

Right after Ardell stopped to rest, the plantation manager<br />

showed up. Boone was what all the croppers called him. We<br />

never did know his last name.<br />

4

I can still see him riding toward us on his horse. With<br />

black folks, Boone had a way of twisting himself into something<br />

mean and venomous like a viper that’s been stepped on.<br />

“Ardell!” he shouted scornfully. “Get back to work!” My sister<br />

just looked at him as she wiped the sweat from her forehead.<br />

“I’ve got to rest for a moment,” she said.<br />

Boone got off his horse and walked toward her with an<br />

angry look on his face. I could see my sister was about to faint<br />

from the heat and the hard work, and I knew Boone wouldn’t<br />

think twice about calling her a lazy good-for-nothing. So I<br />

threw off the sack of cotton I had slung over my shoulder and<br />

got between Boone and Ardell. “Leave her alone,” I implored.<br />

But Boone wouldn’t back down. He just went on berating her.<br />

He even threatened to punch me if I didn’t shut up.<br />

My father must have heard us because he came running<br />

through the rows of cotton bushes. “Hold on, Boone!”<br />

he yelled. “There’s no need to lose your temper.” Boone shot<br />

him a look dripping with contempt. I held my ground while<br />

Ardell pleaded with me to pick up my sack and go back to<br />

work. I could tell from the gleam in his eyes that Boone hoped<br />

I would give him a reason to strike. But I just stood my ground.<br />

Suddenly, my father was by my side. He grabbed Boone’s<br />

arm. The two men glared intently at each other. <strong>No</strong>t a word<br />

passed between them as they struggled to see which one would<br />

be the first to break. My father’s grip, tight as the clamp of a<br />

snapping turtle, stopped the circulation in Boone’s arm.<br />

5

When he couldn’t stand the pain any longer, Boone relented.<br />

The awful tension between them subsided.<br />

“Turner,” he said to my father as he got back on his horse,<br />

“you just bought a one-way ticket to ruin for your whole goodfor-nothing<br />

family. Mark my words.” Then Boone rode off.<br />

My father didn’t speak to me for the rest of the day. I knew<br />

when he got silent like that a storm was brewing up inside<br />

him. My sister and I tried to stay out of his way. But that night<br />

during supper, the rains came down heavy, and the lightning<br />

struck. “How many times have I warned you against confronting<br />

the manager,” he shouted. “<strong>No</strong>w you’ve started something<br />

that is sure to end badly. Boone won’t forget that a black boy<br />

stood up to him.”<br />

My mother served up the rest of the sweet potatoes and<br />

boiled greens. “Leave the boy alone,” she said. “He did what any<br />

decent person would do seeing his sister in trouble. Besides, you<br />

didn’t have to grab Boone’s arm. You only made matters worse.”<br />

“Aaron better learn to control himself,” my father shot<br />

back. “He’s too headstrong, Ruby, just like you.” An exasperated<br />

look took over my father’s face. “Ruby, I’m tired of the way<br />

you’re always telling Aaron how poor black folks shouldn’t have<br />

to live this way. The truth is there’s no other way but this one.”<br />

A match flared in the dim light of our cabin. My grandfather<br />

lit the lantern and set it down beside the stove. “Stop bickering,<br />

both of you,” he said in a quiet, but firm voice to my parents.<br />

“Times are hard, but they’ve been worse, a whole lot worse.”<br />

6

Ardell and I glanced at each other. We knew what was<br />

coming — more of Grandpa’s stories about slavery times. His<br />

own mother had been sold like a piece of merchandise. The<br />

way Boone treated the sharecroppers made me wonder if the<br />

times had really changed all that much.<br />

I shared a bed with my older brother Kermit. Kermit<br />

didn’t pick cotton. He got himself a job cooking for a white<br />

family in town. But he always came home in the evening.<br />

That night I couldn’t fall asleep. There was a full moon,<br />

I remember, and the sound of a train going by. I wondered<br />

where it was bound and what sort of life I could find anywhere<br />

else but here in Jefferson County.<br />

7

A Change In the Air<br />

The next morning I heard something so strident it<br />

sounded like a squall of wild cats. I looked out the window and<br />

saw a tractor chugging down the road, belching soot from a<br />

skinny smoke stack. And there was Boone occupying the driver’s<br />

seat. “Get a move on!” he yelled. “All you croppers got some<br />

serious picking to do if you want to get the crop in on time.”<br />

Then he gunned the engine and started driving toward our<br />

place.<br />

“This here tractor can do the work of 100 hands. Take it<br />

from me, your days are numbered,” Boone called out to every<br />

sharecropper within hearing distance.<br />

I had seen pictures of tractors before. But seeing one up<br />

close made me realize that our life as sharecroppers was about<br />

to change in ways I couldn’t even begin to imagine. Like he did<br />

every morning, my father walked over to my side of the bed and<br />

gently put his hand on my shoulder. “Time to go, son,” he said.<br />

That day was hotter than the day before. Boone was back<br />

on his horse riding from field to field, trying to get the workers<br />

to pick faster. Everybody knew how he had bad-mouthed<br />

Ardell, and some of us decided to get even. We started picking<br />

the cotton bolls lower on the stem, thorns and all. It took us less<br />

time to fill our sacks, and when we weighed in, the sacks were<br />

heavier than usual. Ardell and I finished picking by four o’clock.<br />

Boone did the weighing. He looked warily at us, but he never<br />

figured out that he’d been tricked.<br />

8

My brother Kermit had asked me to come over to the<br />

Johnson place where he was working. He said they needed<br />

someone to do some outside jobs and would pay in cash. The<br />

town was only a few miles away. It had everything a small town<br />

is supposed to have, including a swimming pool, which was<br />

right next to the high school. On warm days the school principal<br />

made sure no black folks ever got in to use the pool when it<br />

wasn’t their time to use it.<br />

The principal was good at his job. By the time I got to<br />

town, he had already caught a boy about my age trying to jump<br />

over the chain link fence around the pool.<br />

9

I could hear the principal lecturing him for ignoring the<br />

rules and telling him in no uncertain terms that coloreds could<br />

only use the pool during off-hours. I felt a fire burning inside<br />

me. I wanted to run across the street and tell the principal to<br />

leave the boy alone. But I was afraid of what would happen to<br />

me if I did. So I kept quiet and went on my way.<br />

The Letter<br />

My brother was really happy to see me. He was wearing<br />

a clean white jacket and looking just like a proper cook. While<br />

he finished making dinner for the Johnsons, I raked up a huge<br />

pile of leaves, straightened out their tool shed, and hosed down<br />

the family car, a shiny black Ford. Then Kermit and I sat on the<br />

back porch and ate. Mrs. Johnson gave us leftovers. I liked her,<br />

but I didn’t like not being allowed to eat in the kitchen.<br />

The cicadas were singing their hearts out. Georgia twilight<br />

made everything look better than it really was, but it also<br />

seemed to promise a change in the air. I took out a piece of<br />

paper from my back pocket and unfolded it. Kermit came down<br />

the steps and sat beside me. “What’s that” he asked.<br />

“A letter from Uncle Eugene,” I said. “It came yesterday.”<br />

Uncle Eugene was my mother’s brother. He grew up on a farm<br />

just like me. But when he was only sixteen he slipped off one<br />

night aboard a freight train. He was determined to make something<br />

of himself.<br />

He ended up in Atlanta and tried his hand at all sorts of<br />

businesses. Eventually, Uncle Eugene opened up his own movie<br />

10

house on Sweet Auburn Avenue. He called it “The Palace,” and<br />

it was a great success.<br />

Kermit couldn’t read very well, so I read the letter out<br />

loud. What I most remember about that letter was the part<br />

where Uncle Eugene said he’d be coming down for a visit in<br />

Thanksgiving. I always loved seeing him. He had a way of<br />

making us all believe the Promised Land was just around the<br />

next bend.<br />

The next day was Sunday, the only day we had off during<br />

the harvest. Our plantation had a church for all the sharecroppers.<br />

We put on our best clothes and went to the morning<br />

service. My sister sang in the choir. I got to turn the pages of the<br />

music book for the piano player. Sometimes he even let me play.<br />

I guess he thought I had the potential to be a piano player, too.<br />

The ladies wore their finest hats and fanned themselves to<br />

keep away the heat. I remember the preacher, a tall, dignified<br />

man with short white hair and a thin mustache. I can still hear<br />

his voice and the way his words flowed over us. He urged us to<br />

have patience. Better times were coming, he kept repeating.<br />

I had trouble believing him. I knew there was something<br />

wrong with the way things were, and I didn’t think sitting<br />

around, waiting for a change to come was the answer. But I was<br />

still too young then to know what had to be done.<br />

After church, my father took me fishing. We went to his<br />

favorite spot — a pond near an old Catalpa tree. We turned<br />

over some of the leaves and found a few green and black caterpillars.<br />

My father called them tree worms.<br />

11

We baited our hooks with them, then threw our lines into<br />

the water and waited. With luck, we’d bring home a mess of<br />

catfish for Sunday dinner. My father caught the first one, and<br />

that put him in a good mood.<br />

“I know your mother’s been talking to you about moving.”<br />

I nodded. He went on. “I’ve thought about it, but I don’t think<br />

it’s the right thing. This is our home. Our family’s been occupying<br />

this land for over 100 years. <strong>Cotton</strong> is in our blood. That’s<br />

the truth, and nothing will ever change that.”<br />

“What about Uncle Eugene” I said, only daring to challenge<br />

him because he seemed in such a good mood. “He left the<br />

fields and made a life for himself in the city. Maybe we could do<br />

the same. I heard on the radio that President Roosevelt wants<br />

to help poor folks. He could find you a job, and we wouldn’t<br />

have to pick cotton any more.”<br />

My father stuck another worm on his hook. “<strong>Cotton</strong>, corn,<br />

tobacco — they’re all dropping in price. But that won’t last<br />

forever. The government will set things right, you’ll see, and<br />

when prices shoot back up, sharecroppers like me will come out<br />

ahead. I figure the best thing we can do is stay put and not be<br />

running off with our tails between our legs.” My father plunked<br />

his line in the water and sat back against the Catalpa tree.<br />

I knew there was nothing more I could say to change his mind.<br />

We got our cotton in by the end of the following week.<br />

It was a good harvest, and my father was more hopeful than I’d<br />

seen him in a long time. He was sure this year’s settle would net<br />

him a pile of money.<br />

13

He even figured out how many more acres he could cultivate<br />

next year with the money he made this year. But my<br />

mother wasn’t so optimistic. She was afraid once their account<br />

was settled they’d fall even further behind.<br />

The settle wouldn’t happen until a week or so before<br />

Christmas. That’s when Boone would add up the money he got<br />

from the sale of our cotton and then deduct expenses.<br />

Thanksgiving<br />

Getting ready for Thanksgiving and a visit from Uncle<br />

Eugene took our minds off work. My mother planned on serving<br />

sweet potato pie, black-eyed peas, cornbread, and chicken.<br />

When the big day finally arrived, Uncle Eugene announced<br />

his arrival by blowing the horn on his car. I ran outside and<br />

saw him driving up in a shiny red Buick with chrome bumpers.<br />

He parked the car and stepped out with those long legs of his.<br />

“Aaron, Ardell, come here and give your Uncle Eugene a big<br />

hug,” he said with a grin.<br />

During dinner, my father didn’t talk too much. He<br />

frowned a lot and looked disapproving, like maybe he thought<br />

Uncle Eugene was turning our heads in the wrong direction.<br />

Uncle Eugene spent the whole meal telling us about the movie<br />

business and the famous entertainers who sometimes performed<br />

at The Palace. Movie houses in those days didn’t just show<br />

movies. They were also places where performers could do their<br />

acts. My uncle’s stories started me thinking about the kind of<br />

life I wanted to have someday.<br />

14

After dinner, we piled into Uncle Eugene’s Buick and drove<br />

to town. He took us to Schenley’s Drugstore for ice cream with<br />

all the toppings. We sat at a table near the back, right below a<br />

faded sign. My mother read it out loud. “Colored Section,” she<br />

said with a streak of anger in her voice. White customers sitting<br />

at the counter kept staring at us like we were doing something<br />

wrong.<br />

“Things any different in Atlanta” my mother asked.<br />

“Or does Jim Crow live there, too”<br />

“He’s there, Ruby,” my uncle said. “Old Jim’s got white folks<br />

thinking the sun rises and sets just for them, and black folks<br />

ought to keep to themselves if they want to stay out of trouble.”<br />

15

“But all along Atlanta’s Sweet Auburn Avenue, we got our<br />

own businesses. That’s where I got my start. Any time you want<br />

to make a change, Sister, you let me know and I’ll help set you<br />

up. That’s a promise you can take to the bank.”<br />

My father stood up and put on his hat. “We don’t need<br />

your promises, Eugene,” he said. “And we surely don’t need<br />

your high-sounding talk about things being better in Atlanta.<br />

I got a wife and three kids to raise, and working the land is what<br />

I know best.”<br />

The Settle<br />

Uncle Eugene left for Atlanta the next day. A few weeks<br />

later my father got called to the plantation office. It was time<br />

for the settle. Boone was alone in the office when my father<br />

and I walked in. He met us with a thick accounting book in his<br />

hands. He showed us the numbers he’d written in neat columns,<br />

and then said, “It looks like we’re even again this year, Thomas.<br />

I’ll see you in the spring.”<br />

My father looked dazed, like he’d been struck with a brick.<br />

He didn’t say anything to Boone. He just grabbed the sleeve of<br />

my coat and pulled me outside. Snow was falling. We walked<br />

home in dead silence. “How’d we do this year, Thomas” my<br />

mother asked quietly when she saw him.<br />

But he didn’t answer her. He just sat down at the table<br />

and put his head in his hands. I’d never seen my father<br />

cry before.<br />

16

The next morning, my father and mother were sitting at<br />

the table, talking in hushed voices. They went quiet when we<br />

sat down for breakfast. Then my father got up and left, without<br />

saying a word to any of us.<br />

When spring came, my father fixed up a broken down old<br />

Ford another family had left behind. With nothing but a few<br />

dollars in our pockets, a box of crackers, and the promise of a<br />

better life, we left our cabin and headed for Atlanta.<br />

17

Life in Georgia<br />

My uncle helped us as best he could. He got my father and<br />

my brother jobs in construction through one of those government<br />

programs. Back in those days, when the Depression was<br />

bearing down on everybody, black or white, President Roosevelt<br />

started something called the New Deal. He believed the best<br />

way to get the economy going was for the government to lend a<br />

hand. So he started programs that put people to work building<br />

all kinds of things, like libraries, roads, parks, and schools.<br />

Uncle Eugene put me to work as an usher in his movie<br />

house. When I wasn’t showing people to their seats, I ducked<br />

down to the basement and tinkered away on an old piano.<br />

Once it made silent movies come to life. But those days were<br />

long gone.<br />

By the time the war started, I was making a little money<br />

playing piano in small clubs along Sweet Auburn. But I hurt<br />

my hand during the war, so after I got out of the Army, I had<br />

to do something else. I started writing music, book, and movie<br />

reviews for a local paper and columns about life in Georgia<br />

after the war. Twenty years later, I’m one of the editors. I’ve got<br />

a nice home and my own family now. For the son of a sharecropper,<br />

I guess you could say I did all right.<br />

18

Responding<br />

TARGET SKILL Cause and Effect In this<br />

story, you read about a family of sharecroppers<br />

in the 1930s. Copy the chart below. Write down<br />

the effects working on the plantation had on<br />

Aaron and his family.<br />

Cause<br />

Working as<br />

sharecroppers<br />

Effects<br />

School closed when<br />

cotton needed to<br />

be picked.<br />

<br />

Write About It<br />

Text to Self Write a paragraph describing the<br />

effects of sharecropping on Aaron’s family.<br />

Remember to include main ideas from the story.<br />

19

TARGET VOCABULARY<br />

confronting<br />

contempt<br />

exasperated<br />

implored<br />

intently<br />

occupying<br />

scornfully<br />

strident<br />

subsided<br />

warily<br />

EXPAND YOUR VOCABULARY<br />

berating<br />

furnish<br />

plantation<br />

settle<br />

sharecropping<br />

TARGET SKILL Cause and Effect Tell how events<br />

are related and how one event causes another.<br />

Write About It<br />

TARGET STRATEGY Analyze/Evaluate Think<br />

carefully about the text and form an opinion about it.<br />

In a famous quotation, Aung San Suu Kyi said,<br />

GENRE “Please Historical use your Fiction freedom is a to story promote whose ours.” characters<br />

and What events freedoms are set in do a you real value period most of history. Why Write<br />

a letter to the editor of a Burmese newspaper<br />

explaining the freedoms you have and why they<br />

are important to you.<br />

20

Level: X<br />

DRA: 60<br />

Genre:<br />

Historical Fiction<br />

Strategy:<br />

Analyze/Evaluate<br />

Skill:<br />

Cause and Effect<br />

Word Count: 3,561<br />

6.5.<strong>23</strong><br />

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN<br />

Online Leveled Books<br />

1032089