Lesson 10:Saving the Mexican Wolves

Lesson 10:Saving the Mexican Wolves

Lesson 10:Saving the Mexican Wolves

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

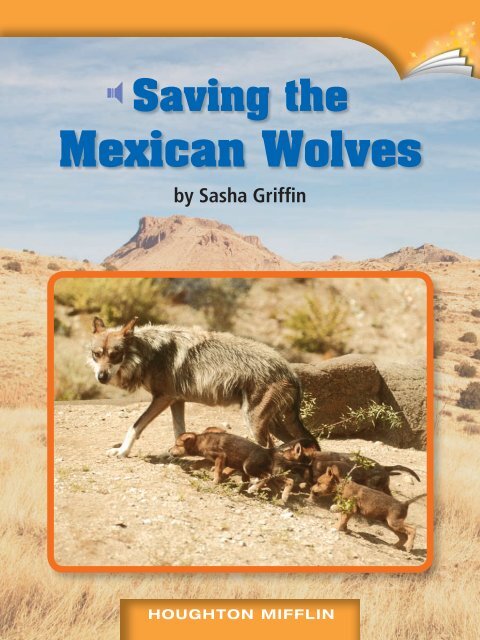

<strong>Saving</strong> <strong>the</strong><strong>Mexican</strong> <strong>Wolves</strong>by Sasha GriffinPHOTOGRAPHY CREDITS: Cover © Robert Winslow/Animals Animals. (bkgd) © Robert Shantz/Alamy. Title Page© Robert Winslow/Animals Animals. 2-18 (bkgd) © Robert Shantz/Alamy. 2 © Robert Winslow/Animals Animals.4 © Thomas & Pat Leeson/Photo Researchers, Inc. 8 MPI/Hulton Archive/Getty Images. 15 © Lawrence Migdale/PIX.17 © Robert Winslow/Animals Animals.Copyright © by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing CompanyAll rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic ormechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without <strong>the</strong> priorwritten permission of <strong>the</strong> copyright owner unless such copying is expressly permitted by federal copyright law. Requestsfor permission to make copies of any part of <strong>the</strong> work should be addressed to Houghton Mifflin Harcourt School Publishers,Attn: Permissions, 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, Florida 32887-6777.Printed in ChinaISBN-13: 978-0-547-01656-6ISBN-<strong>10</strong>: 0-547-01656-51 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 0940 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11If you have received <strong>the</strong>se materials as examination copies free of charge, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt School Publishersretains title to <strong>the</strong> materials and <strong>the</strong>y may not be resold. Resale of examination copies is strictly prohibited.Possession of this publication in print format does not entitle users to convert this publication, or any portion of it, intoelectronic format.

IntroductionFor hundreds of years, <strong>the</strong> howls of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mexican</strong> gray wolfpierced <strong>the</strong> starry nights of <strong>the</strong> American Southwest. Packs of<strong>the</strong>se wolves roamed <strong>the</strong> high woodlands of what is now Arizona,New Mexico, Texas, and Mexico. Members of a pack huntedtoge<strong>the</strong>r, raised <strong>the</strong>ir young, and helped to maintain <strong>the</strong> delicatebalance of nature. Just 150 years after Europeans settled <strong>the</strong>Southwest, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mexican</strong> wolf was on <strong>the</strong> brink of extinction. Bythat time, it had disappeared entirely from <strong>the</strong> United States.Thanks to <strong>the</strong> efforts of conservationists, today severalpacks of wolves roam a small section of <strong>the</strong>ir former habitat onceagain. But now <strong>the</strong>y must share this space with people. Themodern world has brought highways, homes, ranches, andlivestock such as sheep and cattle to this once-wild region.Living near humans is not easy for wolves.The <strong>Mexican</strong> wolf’s story is a complicated one. It is a storyin which <strong>the</strong> needs of wolves and <strong>the</strong> needs of people are sometimespitted against each o<strong>the</strong>r. It’s a storythat makes people wonder whe<strong>the</strong>rit is even possible for wolvesand humans to coexist.To understand thisstory, we must firstunderstand <strong>the</strong> rare<strong>Mexican</strong> wolf.2

Did you know? <strong>Wolves</strong> can run upto 35 miles per hour in short burstswhen <strong>the</strong>y are chasing <strong>the</strong>ir prey.The <strong>Mexican</strong> Gray WolfThe <strong>Mexican</strong> gray wolf (Canis lupus baileyi) is a mammalin <strong>the</strong> vertebrate group. These wolves are sometimes calledlobos. (Lobo is <strong>the</strong> Spanish word for “wolf.”) The <strong>Mexican</strong> wolf isa subspecies of <strong>the</strong> gray wolf. It is <strong>the</strong> most endangered of allgray wolves in North America.Like all wolves, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mexican</strong> wolf is related to both dogs andcoyotes. A mature lobo is approximately <strong>the</strong> size of a Germanshepherd. It measures four to five feet long and weighs 60 to 80pounds. The <strong>Mexican</strong> wolf is <strong>the</strong> smallest kind of gray wolf,although it is still larger than a coyote. The fur of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mexican</strong>wolf—a mixture of tan, gray, rust, and black—resembles that of acoyote.<strong>Wolves</strong> have very keen senses of hearing, smell, and vision.These characteristics help wolves locate and hunt <strong>the</strong>ir prey,even at night. Because wolves are carnivores, <strong>the</strong>ir teeth areadapted to <strong>the</strong> job of catching, killing, and eating prey. <strong>Mexican</strong>wolves can eat up to 20 pounds of meat at one time, so <strong>the</strong>yonly need to eat a couple of times a week. This helps <strong>the</strong>msurvive when prey is scarce. <strong>Mexican</strong> wolves’ natural prey islarge, hoofed mammals, such as deer and elk. Lobos will also eatwild pigs called javelina and o<strong>the</strong>r small mammals, such as rabbits.3

<strong>Mexican</strong> wolves live in family groups called packs. A packconsists of an adult pair (which usually mates for life), <strong>the</strong>irpups, and sometimes <strong>the</strong> pair’s older offspring. Each packhas its own territory, which can range from <strong>10</strong>0 to more than500 square miles. <strong>Wolves</strong> mark <strong>the</strong> boundaries of <strong>the</strong>ir territorywith scent to keep o<strong>the</strong>r wolf packs away.The members of a wolf pack communicate with each o<strong>the</strong>rby barking, growling, and whimpering, as well as with bodypostures and movements. Dogs use many of <strong>the</strong> same behaviorswhen <strong>the</strong>y try to communicate with people. The howling ofwolves is an eerie, mysterious sound. <strong>Wolves</strong> howl to locate oneano<strong>the</strong>r or as a means of ga<strong>the</strong>ring toge<strong>the</strong>r. Howling is oftenheard before a hunt. During a hunt, <strong>the</strong> pack works toge<strong>the</strong>r tolocate, chase down, and kill <strong>the</strong>ir prey.Like dogs, wolves express <strong>the</strong>mselves througha variety of body postures.4

<strong>Mexican</strong> wolves once roamed throughout parts of <strong>the</strong>southwestern United States and Mexico. Their habitat consistedof mountain woodlands and forests, as well as grasslands andshrublands. Though <strong>Mexican</strong> wolves are carnivores, plant life isimportant for <strong>the</strong>ir survival. That’s because plants provide foodfor deer and elk, <strong>the</strong> wolves’ primary prey. If <strong>the</strong> plant populationcannot support herds of deer and elk, <strong>the</strong> wolves may nothave enough to eat.The <strong>Mexican</strong> wolf is an example of an apex predator. Anapex predator has no natural enemies. It is at <strong>the</strong> top of <strong>the</strong> foodchain. Despite its position as top predator, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mexican</strong> wolf isaffected by <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r plants and animals in its ecosystem becauseeverything in an ecosystem is connected. In <strong>the</strong> case of <strong>the</strong><strong>Mexican</strong> wolf, survival depends upon a sufficient quantity ofdeer, elk, and o<strong>the</strong>r mammals on which <strong>the</strong>y can feed. Theseherbivores live off <strong>the</strong> available supply of edible plants. If adrought causes <strong>the</strong> plants to die, <strong>the</strong> population of herbivoreswill decrease. This affects <strong>the</strong> wolves.This wolf’sposture says,“I’m going toattack now!”5

Deer<strong>Mexican</strong>WolfElkPlantsSunA food chain shows how energy moves from <strong>the</strong> sun to plants and<strong>the</strong>n to animals in an ecosystem. This diagram shows <strong>the</strong> food chainin <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mexican</strong> wolves’ ecosystem.As predators, wolves help keep o<strong>the</strong>r animal populationsunder control. Without wolves, <strong>the</strong> deer and elk populationswould grow too large. They would devour <strong>the</strong> plants in <strong>the</strong>irhabitat faster than <strong>the</strong> plants can grow. O<strong>the</strong>r herbivores, suchas rabbits and mice, would suffer as a result. Every part of anecosystem—water, sunlight, vegetation, herbivores, and carnivores—worktoge<strong>the</strong>r to keep it in balance.Some people believe that wolves can completely kill off all<strong>the</strong> deer or elk in <strong>the</strong>ir habitat, but that is not <strong>the</strong> case. <strong>Wolves</strong>keep <strong>the</strong> population of deer and elk under control withouteliminating <strong>the</strong>m. And because wolf packs tend to select weak,unhealthy animals to hunt, <strong>the</strong>y help <strong>the</strong> herbivore populationremain strong and healthy. This varies from <strong>the</strong> way o<strong>the</strong>rpredators such as bears or cougars hunt. These animals ambushboth healthy and unhealthy animals.6

The Clash of <strong>Wolves</strong> and PeopleThe <strong>Mexican</strong> wolf was an important member of its ecosystemfor hundreds of years. What happened to push wolves to<strong>the</strong> edge of extinction? Part of <strong>the</strong> answer to this question liesin people’s relationship with wolves in general.For centuries people have feared and hated wolves. Folktalesand fables often portray wolves as ferocious and cunning killers.Many of <strong>the</strong>se stories are misleading. For example, in “Little RedRiding Hood,” a wolf eats an old woman and hatches an evil planto gobble up a little girl. In truth, wolves do not eat people. Likemost wild animals, wolves try to avoid contact with humans. Yetsuch stories added to people’s fear of wolves.Common Sayings About <strong>Wolves</strong>Many common sayings also contributeto <strong>the</strong> wolf’s bad reputation.“To throw someone to <strong>the</strong> wolves” means toabandon someone to a terrible fate.“To keep <strong>the</strong> wolf from <strong>the</strong> door” meansto avoid hunger or poverty.“A wolf in sheep’s clothing” is someone whopretends to be a friend, but is really an enemy.7

New settlers in <strong>the</strong> wolves’ territory began trapping and killing<strong>the</strong> animals.In <strong>the</strong> late 1800s, <strong>the</strong> railroads connecting <strong>the</strong> easternUnited States to <strong>the</strong> West were completed. This made it easierfor settlers to move to <strong>the</strong> Southwest. The settlers found plentyof deer and elk in <strong>the</strong>ir new home. They hunted <strong>the</strong>se animalsfor food and sold <strong>the</strong> meat and hides, as well. For <strong>the</strong> first time,<strong>the</strong> lobos had to compete with large numbers of humans for <strong>the</strong>irfood. It became harder and harder for wolves to find enoughdeer and elk because so many were killed by people.At around this time, <strong>the</strong> first cattle ranches were establishedin <strong>the</strong> area. <strong>Wolves</strong> occasionally ate <strong>the</strong> settlers’ livestock when<strong>the</strong>y couldn’t find <strong>the</strong>ir natural prey. This upset <strong>the</strong> ranchers,who began trapping, shooting, and poisoning <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mexican</strong> wolvesout of existence. People’s historical fear of wolves may also havecontributed to <strong>the</strong> large-scale killing off of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mexican</strong> wolf.8

The government officially supported various programs toexterminate all gray wolves in <strong>the</strong> United States. It offeredbounties, or rewards, to people who killed wolves. Although<strong>the</strong> <strong>Mexican</strong> wolf was once common in <strong>the</strong> Southwest, by <strong>the</strong>1950s just a handful of wolves were left in <strong>the</strong> wild. In 1970,<strong>the</strong> last wild lobo was killed in <strong>the</strong> United States.Not everyone was pleased with <strong>the</strong> wolves’ disappearance.In 1944, environmentalist Aldo Leopold wrote a famous essaytitled “Thinking Like a Mountain.” He had recently gone outhunting with several o<strong>the</strong>rs and had taken part in <strong>the</strong> killing ofa mo<strong>the</strong>r <strong>Mexican</strong> wolf with cubs. In his essay, Leopoldexplained that before <strong>the</strong> hunt, he thought that “fewer wolvesmeant more deer, that no wolves would mean hunter’s paradise.”However, his experience with <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mexican</strong> wolf family causedhim to have a change of heart. Leopold said that he and <strong>the</strong>o<strong>the</strong>r hunters reached <strong>the</strong> mo<strong>the</strong>r wolf just in time to watch“<strong>the</strong> fierce green fire dying in her eyes.” In that moment,Leopold said he realized that wolves are as important to <strong>the</strong>wilderness as <strong>the</strong> wilderness is to <strong>the</strong> wolves.9

The Endangered Species ActThe Endangered Species Act was signedin 1973. This law protects plants and animalsthat are in danger of becoming extinct. It alsoprotects <strong>the</strong> habitats in which <strong>the</strong>se specieslive. More than 1,800 plants and animals arelisted as endangered.A small group of dedicated people decided to try to bring<strong>the</strong> <strong>Mexican</strong> wolf back to its original habitat. Fortunately, asmall group of wild wolves was still living in a remote region ofMexico. After <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mexican</strong> wolf was listed as an endangeredspecies in 1976, five of those wolves were trapped and broughtto <strong>the</strong> United States. The wolves, along with some o<strong>the</strong>rs thathad already been captured, were bred in captivity. Now scientistsbelieve that without this breeding program, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mexican</strong>wolf would probably have become extinct.The captive breeding program was only <strong>the</strong> first step. TheEndangered Species Act also calls for <strong>the</strong> recovery of endangeredspecies. This means that not only must <strong>the</strong> population besaved from extinction—it also must be returned to its naturalhabitat. But after people had nearly wiped out <strong>the</strong>se animals,would <strong>the</strong>y be willing to see <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mexican</strong> wolf reintroduced?How could wolves and humans possibly exist toge<strong>the</strong>r?<strong>10</strong>

The <strong>Wolves</strong> Make a ComebackOne of <strong>the</strong> purposes of <strong>the</strong> captive breeding program was toproduce a group of <strong>Mexican</strong> wolves that could be reintroducedinto <strong>the</strong> wild. But reintroducing a predator is very complicated.Many questions must be considered. How will <strong>the</strong> lobos affect<strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r plants and animals in <strong>the</strong> ecosystem? How will <strong>the</strong>yaffect <strong>the</strong> people and livestock that now live in <strong>the</strong> region? Canwolves raised in captivity survive and breed in <strong>the</strong> wild?The people who led <strong>the</strong> wolf recovery program were convincedof one thing. Captive-bred <strong>Mexican</strong> wolves could notjust be turned loose in <strong>the</strong> Southwest. There needed to be anoverall plan.The <strong>Mexican</strong> Wolf Recovery Plan was approved by <strong>the</strong> U.S.and Mexico in 1982. The plan’s main goal was to reestablish atleast <strong>10</strong>0 <strong>Mexican</strong> wolves within part of <strong>the</strong>ir original range.Ano<strong>the</strong>r goal was to make sure that <strong>the</strong> wolves did not createproblems for people and livestock.Did you know? Some dogs andwolf-dog crossbreeds are moredangerous to people than wild wolves.11

Proposed Wolf Recovery Areas in <strong>the</strong> SouthwestArizonaBlue RangeAreaAlbuquerquePhoenixTucsonWhite SandsMissile RangeNewMexicoLubbockTexasDallasBig BendNational ParkMEXICOHistoric Range of<strong>the</strong> <strong>Mexican</strong> WolfProposedReintroduction SiteProposed as AdditionalReintroduction Site by Defenders of WildlifeMany of <strong>the</strong> region’s residents were worried about <strong>the</strong>return of <strong>the</strong> wolves. Some people were concerned that <strong>the</strong>wolves would be dangerous to <strong>the</strong>m and <strong>the</strong>ir pets. Rancherswere afraid that wild wolves would kill <strong>the</strong>ir cattle and sheep.Yet many o<strong>the</strong>rs supported <strong>the</strong> wolf recovery plan.A number of government agencies joined toge<strong>the</strong>r tooversee <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mexican</strong> Wolf Recovery Project. Officials listenedto <strong>the</strong> many opinions about reintroducing <strong>the</strong> lobos. The groupcreated rules that would hopefully protect people, livestock, and<strong>the</strong> wolves.12

The group also had to find just <strong>the</strong> right place to release<strong>the</strong> wolves. This particular place would need to be large enoughfor <strong>the</strong> wolves to roam, yet not too near people and livestock.Finally it was decided that <strong>the</strong> wolves would be released onnational forest land in Arizona and New Mexico. This regionwas named <strong>the</strong> Blue Range Wolf Recovery Area.In 1998, 22 years after <strong>the</strong> wild wolves were brought to <strong>the</strong>United States from Mexico, officials decided it was time torelease some wolves back into <strong>the</strong> wild. Eleven captive <strong>Mexican</strong>wolves were brought to <strong>the</strong> Blue Range Wolf Recovery Area.The wolves were not turned loose immediately. They were keptin large pens for several weeks. This helped <strong>the</strong>m get used to<strong>the</strong>ir new environment. Wildlife workers watched over <strong>the</strong>wolves during this period.The workers planned to keep track of <strong>the</strong> wolves after <strong>the</strong>irrelease, as well. A team of scientists, conservationists, and o<strong>the</strong>rswould use a variety of methods to detect <strong>the</strong> wolves’ movementswhile remaining unobserved <strong>the</strong>mselves. <strong>Wolves</strong> are naturallycontent to keep away from people, and it was important that<strong>the</strong>y stay that way.In March of 1998, <strong>the</strong> first eleven wolves were released.Unfortunately, five of <strong>the</strong> wolves were shot within <strong>the</strong> year.Residents and ranchers still felt that <strong>the</strong>y and <strong>the</strong>ir animalswere in danger.13

More captive-bred wolves were released. The wolves beganhaving pups in <strong>the</strong> wild. Yet <strong>the</strong>y continued to run into problems.The biggest threat to wolves continued to be people.Some <strong>Mexican</strong> wolves wandered onto highways and were hit bycars. O<strong>the</strong>rs were shot. At least one was killed by a mountainlion. Some of <strong>the</strong>m wandered out of <strong>the</strong> Blue Range WolfRecovery Area and had to be recaptured.Conservation groups and o<strong>the</strong>rs continued working tokeep <strong>the</strong> reintroduced lobos safe. They began paying ranchersfor cattle or sheep that were killed by wolves. And since wolveswill sometimes eat animals that are already dead, ranchers wereencouraged to remove livestock carcasses so that wolveswouldn’t be attracted to <strong>the</strong>m.Sometimes wolves were shot because people mistook <strong>the</strong>mfor coyotes. Coyotes are common in <strong>the</strong> Southwest, and <strong>the</strong>y doharm livestock. That’s why educating <strong>the</strong> public is an importantpart of <strong>the</strong> reintroduction effort. People need to learn <strong>the</strong>differences between coyotes and <strong>Mexican</strong> wolves. Educationcan also help people understand wolves’ place in <strong>the</strong> ecosystem.Because wolves are an apex predator, <strong>the</strong>y can actually keepcoyotes away from an area. Knowing this may persuade peopleto protect <strong>the</strong> wolves.14

The White Mountain Apache—Friends of <strong>the</strong> WolfOne group that has played an important role in <strong>the</strong> lobos’recovery is <strong>the</strong> White Mountain Apache tribe in Arizona. Theirreservation is next to <strong>the</strong> national forest where <strong>the</strong> wolves werefirst released. Before <strong>the</strong> settlers came, wolves and <strong>the</strong> Apachecoexisted. Many traditional Apache stories and songs tell of <strong>the</strong>importance of animals such as <strong>the</strong> wolf.When <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mexican</strong> wolf was first reintroduced, <strong>the</strong> WhiteMountain Apache tribal council had to make some decisions.What should happen to reintroduced wolves that wandered onto<strong>the</strong> reservation? Should <strong>the</strong> wolves be removed? Or, should <strong>the</strong>ybe allowed to form packs on tribal land?Like o<strong>the</strong>r ranchers, Apache ranchers were concerned that<strong>the</strong> wolves would kill <strong>the</strong>ir cattle. Apache hunting guides worriedthat <strong>the</strong>ir clients would have to compete with <strong>the</strong> wolvesfor deer and elk. Yet along with <strong>the</strong> needs of its people, <strong>the</strong> tribeconsidered <strong>the</strong> needs of <strong>the</strong> wolves.The WhiteMountain Apachetribe now lives on<strong>the</strong> Fort ApacheReservation insou<strong>the</strong>asternArizona.15

The tribal council signed an agreement to let reintroduced<strong>Mexican</strong> wolves roam on reservation land. This agreement hashelped <strong>the</strong> recovery effort in important ways. It allowed <strong>the</strong>wolves’ habitat to expand as <strong>the</strong>ir population grew. <strong>Wolves</strong> thatwere born in <strong>the</strong> wild have formed new packs that live onreservation land. The tribe also allowed a captive-bred pair ofwolves to be released on reservation land. Now this pair’s wildbornpups are grown and have pups of <strong>the</strong>ir own.A tribal wolf biologist monitors <strong>the</strong> wolves using radiocollars and o<strong>the</strong>r means. She also works with ranchers andguides to try to prevent wolf attacks on livestock. She talks toschoolchildren about <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mexican</strong> wolf’s return.The White Mountain Apache tribe has joined with <strong>the</strong>o<strong>the</strong>r agencies to oversee <strong>the</strong> lobo’s recovery. Both conservationgroups and <strong>the</strong> government have praised <strong>the</strong> tribe for <strong>the</strong>ir rolein reintroducing <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mexican</strong> wolf. Many see <strong>the</strong> WhiteMountain Apache as a role model for helping to reintroduceendangered species back into <strong>the</strong> wild.16

A mo<strong>the</strong>r wolf protects her cubs andteaches <strong>the</strong>m appropriate behavior.The story of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mexican</strong> wolf is not a fairy tale pittinggood against evil. It is a complicated story of conflicting needs.It is made even more complicated by people’s misunderstandingof wolves. The controversy continues even today. Ranchers,residents, and conservationists still don’t agree on what shouldbecome of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mexican</strong> wolf. Yet as <strong>the</strong> White Mountain Apachehave shown, solutions can be found that meet <strong>the</strong> needs of bothpeople and wolves.Continued public education can help prevent <strong>the</strong> deaths ofmore wolves. It can show people that wolves have an importantplace in <strong>the</strong> ecosystem. It is not too late for <strong>the</strong> story of <strong>the</strong><strong>Mexican</strong> wolf to have a happy ending.17

<strong>Mexican</strong> <strong>Wolves</strong> and People1870s1890s1950sSettlers establish ranches in Arizona and New Mexico.Government begins offering bounties to kill wolves.Only a handful of <strong>Mexican</strong> wolves are left in <strong>the</strong> wild.1970 The last confirmed <strong>Mexican</strong> wolf in <strong>the</strong> U.S. is killed.1973 The Endangered Species Act is signed.1976 The <strong>Mexican</strong> wolf is listed as an endangered species.1977– The last wild <strong>Mexican</strong> wolves are caught in Mexico1980 and put in a captive breeding program.1982 The <strong>Mexican</strong> Wolf Recovery Plan is approved.1998 The first eleven <strong>Mexican</strong> wolves are released into <strong>the</strong>wild; five of <strong>the</strong>m are shot.2002 The White Mountain Apache tribe agrees to allowwolves on reservation lands.2003 The first pack of wolves is released onto <strong>the</strong>reservation of <strong>the</strong> White Mountain Apache tribe.2006 An estimated 59 <strong>Mexican</strong> wolves live within <strong>the</strong> BlueRange Wolf Recovery Area.18

RespondingTARGET SKILL Main Ideas and Details Whatare <strong>the</strong> main ideas in <strong>Saving</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mexican</strong> <strong>Wolves</strong>?What details support <strong>the</strong> main ideas? Copy andcomplete <strong>the</strong> web below.Supporting Detail:?Supporting Detail:?Main Idea:?Supporting Detail:?Supporting Detail:<strong>Wolves</strong> are apexpredators.Write About ItText to World Do you think efforts to restore <strong>the</strong><strong>Mexican</strong> wolf population in <strong>the</strong> wild should continue?Why or why not? Write several paragraphs in whichyou state your opinion and give reasons to supportyour ideas.19

TARGET VOCABULARYavailablecontentmentdetectingferociouskeenmatureparticularresembleunobservedvaryEXPAND YOUR VOCABULARYapexcaptivitycarcassescoexistexterminateposturesTARGET SKILL Main Ideas and Details Identify atopic’s important ideas and supporting details.TARGET STRATEGY Monitor/Clarify As you read,notice what isn’t making sense. Find ways to figure out<strong>the</strong> parts that are confusing.GENRE Informational Text gives facts and examplesabout a topic.20

Level: VDRA: 50Genre:Informational TextStrategy:Monitor/ClarifySkill:Main Ideas and DetailsWord Count: 3,0045.2.<strong>10</strong>HOUGHTON MIFFLINOnline Leveled BooksISBN-13:978-0-547-01656-6ISBN-<strong>10</strong>:0-547-01656-5<strong>10</strong>31493