Community Junior Sport Coaching final report - 2009

Community Junior Sport Coaching final report - 2009

Community Junior Sport Coaching final report - 2009

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Community</strong> <strong>Junior</strong> <strong>Sport</strong> <strong>Coaching</strong><br />

Final Report<br />

November <strong>2009</strong><br />

Authored By:<br />

Donna O’Connor PhD and Wayne Cotton PhD<br />

The University of Sydney<br />

<strong>Junior</strong> <strong>Community</strong> <strong>Coaching</strong> Report December <strong>2009</strong><br />

1

Table of Contents<br />

Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................ 2<br />

List of Figures ...................................................................................................................................... 4<br />

List of Tables ....................................................................................................................................... 5<br />

Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................. 6<br />

Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................. 7<br />

Chapter 1 ............................................................................................................................................... 14<br />

Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 14<br />

Aim and Objectives of the Research ............................................................................................. 14<br />

Methodologies .............................................................................................................................. 14<br />

Report Outline............................................................................................................................... 15<br />

Chapter 2 ............................................................................................................................................... 16<br />

Literature Review .............................................................................................................................. 16<br />

<strong>Junior</strong> <strong>Sport</strong> Coaches and <strong>Junior</strong> <strong>Sport</strong> ......................................................................................... 16<br />

Developmental Model of <strong>Sport</strong> Participation ............................................................................... 16<br />

Players in Action ............................................................................................................................ 18<br />

The benefit of <strong>Junior</strong> <strong>Sport</strong> Participation ...................................................................................... 18<br />

Coaches in Action .......................................................................................................................... 19<br />

Coach enjoyment and retention ................................................................................................... 21<br />

Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 21<br />

Chapter 3 ............................................................................................................................................... 22<br />

Methodology Underlying the Research ............................................................................................ 22<br />

Ethical Considerations ................................................................................................................... 22<br />

Participant Recruitment ................................................................................................................ 22<br />

Instruments ................................................................................................................................... 22<br />

Overview of Data Collection Techniques ...................................................................................... 26<br />

Method of Analysis ....................................................................................................................... 26<br />

Ensuring Validity and Reliability .................................................................................................... 27<br />

Issues Faced During Data Collection ............................................................................................. 28<br />

Conclusion ..................................................................................................................................... 28<br />

Chapter 4 ............................................................................................................................................... 29<br />

Results and Discussion ...................................................................................................................... 29<br />

Participant Profile ......................................................................................................................... 29<br />

<strong>Junior</strong> <strong>Community</strong> <strong>Coaching</strong> Report December <strong>2009</strong> 2

Players in Action ............................................................................................................................ 32<br />

Players’ Reflections on the Training Session ................................................................................. 36<br />

Coaches’ in Action ......................................................................................................................... 37<br />

Coaches’ Reflections on the Training Sessions ............................................................................. 49<br />

Comparisons Between Coaches .................................................................................................... 59<br />

Chapter 5 ............................................................................................................................................... 64<br />

Conclusions and Recommendations ................................................................................................. 64<br />

Objectives of the research as guided by the Project Steering Committee ................................... 64<br />

Commendations ............................................................................................................................ 66<br />

Additional Findings with Recommendations ................................................................................ 66<br />

Checklist for effective junior training sessions ............................................................................. 70<br />

Further research ........................................................................................................................... 72<br />

References ........................................................................................................................................ 73<br />

Appendix 1 ........................................................................................................................................ 78<br />

Modified Athlete Enjoyment Scale ............................................................................................... 78<br />

Appendix 2 ........................................................................................................................................ 80<br />

Semi Structured Interview ............................................................................................................ 80<br />

Appendix 3 ........................................................................................................................................ 82<br />

Coach Rating Scale ........................................................................................................................ 82<br />

Appendix 4 ........................................................................................................................................ 84<br />

Specific Rugby League Information ............................................................................................... 84<br />

Appendix 5 ........................................................................................................................................ 91<br />

Specific Rugby Union Information ................................................................................................ 91<br />

<strong>Junior</strong> <strong>Community</strong> <strong>Coaching</strong> Report December <strong>2009</strong> 3

List of Figures<br />

Figure 2-1 The Allocation of Interpersonal and <strong>Sport</strong> Specific Knowledge ........................................ 17<br />

Figure 4-1 A breakdown of the number of years the coaches in the study have been coaching for .. 31<br />

Figure 4-2 Coaches behaviour during the training session measured by systematic observation....... 37<br />

Figure 4-3 Percentage of coach’s behaviours during their training sessions ....................................... 39<br />

Figure 4-4 How the coaches rated their training session immediately afterwards .............................. 49<br />

Figure 4-5 The percentage of coaches who thought they achieved their goals they set for their<br />

training session ................................................................................................................... 51<br />

Figure 4-6 A comparison between coaches perceptions of the level of physical activity and the<br />

recorded level of physical activity....................................................................................... 53<br />

Figure 4-7 A comparison between coaches perceptions of how they allocated time during training<br />

sessions and the actual observations ................................................................................. 54<br />

<strong>Junior</strong> <strong>Community</strong> <strong>Coaching</strong> Report December <strong>2009</strong> 4

List of Tables<br />

Table 2-1 Suggested percentage of time and number of sports during the three stages of the<br />

DMSP .................................................................................................................................. 17<br />

Table 2-2 Percentage of a Practice Session that coach’s spend ‘instructing’ players ......................... 19<br />

Table 2-3 Percentage of Practice session spent in management ....................................................... 20<br />

Table 3-1 A description of the behaviours used in the Video Observation .......................................... 25<br />

Table 3-2 Procedures to Ensure Validity in the Project ........................................................................ 27<br />

Table 4-1 Descriptive statistics about the participants......................................................................... 30<br />

Table 4-2 Self <strong>report</strong>ed reasons why coaches started coaching .......................................................... 31<br />

Table 4-3 The duration and frequency of the coaching sessions ......................................................... 32<br />

Table 4-4 Levels of physical activity of the training sessions measured using SOFIT ........................... 33<br />

Table 4-5 Percentage of time players spent on specific skills ............................................................... 34<br />

Table 4-6 Context of the training sessions measured by SOFIT ............................................................ 35<br />

Table 4-7 Results from the Modified Athlete Enjoyment Scale ............................................................ 36<br />

Table 4-8 A detailed breakdown of the coach’s behaviours during their training sessions ................. 38<br />

Table 4-9 Percentage distribution of variables included in the rating scale of the coaching event ..... 47<br />

Table 4-10 What the coached liked and disliked about the coaching session ..................................... 50<br />

Table 4-11 Personal reflective suggestions on how the coaches thought they could have improved<br />

their training session ........................................................................................................... 51<br />

Table 4-12 What coaches <strong>report</strong>ed they do in training sessions to ensure their players have fun ..... 55<br />

Table 4-13 What the coaches enjoy most about coaching ................................................................... 56<br />

Table 4-14 What the coaches enjoy least about coaching ................................................................... 57<br />

Table 4-15 The main issues facing coaching today as <strong>report</strong>ed by coaches ......................................... 58<br />

Table 4-16 A comparison between the level of coaches qualifications and aspects of the training<br />

session ................................................................................................................................. 60<br />

Table 4-17 A comparison between highly experienced coaches and novice coaches ......................... 61<br />

Table 4-18 A comparison between the contexts of training session as determined by the coaches’<br />

planned activity in the session ............................................................................................ 63<br />

<strong>Junior</strong> <strong>Community</strong> <strong>Coaching</strong> Report December <strong>2009</strong> 5

Acknowledgements<br />

The research team wishes to thank the many coaches and players who volunteered to participate in<br />

this study. We would also like to acknowledge the contribution of the Project Steering Committee:<br />

Michael Asensio (NSW Rugby League)<br />

Cathy Gorman-Brown (<strong>Sport</strong> and Recreation, NSW Communities)<br />

Lara Hayes (Australian <strong>Sport</strong>s Commission)<br />

Natalie Menzies (Australian <strong>Sport</strong>s Commission)<br />

Martin Meredith (NSW Rugby League)<br />

Sally O’Hanlon (Australian Rugby Union)<br />

John Searl (Australian Rugby Union)<br />

Kerry Turner (<strong>Sport</strong> and Recreation, NSW Communities)<br />

Simon Woinarski (<strong>Sport</strong> and Recreation, NSW Communities, chair)<br />

<strong>Junior</strong> <strong>Community</strong> <strong>Coaching</strong> Report December <strong>2009</strong> 6

Executive Summary<br />

<strong>Community</strong> junior coaches play a critical role in providing opportunities for players to develop motor<br />

skills, physical health and psychosocial skills. Currently there is very little empirical evidence on what<br />

happens during junior rugby league and rugby union training sessions. To investigate this and to<br />

start identifying what makes up an effective training session it is necessary to explore not only what<br />

players and coaches are currently doing during training sessions, but also the players and coaches<br />

self reflections about the training sessions.<br />

The study involved 444 participants in total, 37 coaches and 407 under ten players from both rugby<br />

union (17) and rugby league (21) teams around the greater Sydney area. Seventy training sessions<br />

were observed with data collected and analysed using: A Modified SOFIT Testing Instrument; A<br />

Modified Short Form - Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale (S-PACES); <strong>Junior</strong> <strong>Coaching</strong> Observation<br />

Instrument; A Modified Rating scale for coaching sessions; and Pre and Post Training Session Coach<br />

Interviews.<br />

Main findings -<br />

<br />

Qualifications and Experience: All participating coaches except two had a relevant coaching<br />

qualification. The average number of years the coaches have been coaching is 5.59 years.<br />

Training frequency and duration: The average length of the training sessions observed was 55<br />

minutes. Rugby league trains twice per week averaging 104 minutes of training time per week<br />

and rugby union trains once per week averaging 60 minutes of training per week<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Moderate-Vigorous Physical Activity (MVPA) levels: During an average under 10’s RL or RU<br />

training session the players are in MVPA 82% of the time (45 mins) which equals 75% of the<br />

minimum daily recommended amount of exercise. However increasing the amount of time<br />

players spend jogging and reducing walking time could be a realistic goal if increased levels of<br />

physical activity are seen as a priority.<br />

Components of training session: Skill development accounts for 44% or 24.2 minutes of training<br />

sessions. Passing and catching is the most prevalent skill that players practice during training<br />

sessions, with 12% or 6.6 minutes of every training session allocated to passing and catching<br />

drills. An interesting finding from this data is that less than 1% of any coaching session is<br />

dedicated to kicking skills and drills. Playing games make up on average 20% of a training<br />

session. For players during the sampling years (6-12 yrs) it is recommended that over the<br />

complete season the players participate in 80% deliberate play or games and 20% deliberate<br />

practice. Fitness activities accounted for 9% of the training session.<br />

Player enjoyment: The majority of players were very enthusiastic about their sport. The two<br />

aspects of training that they enjoyed the most were playing with friends and playing games.<br />

They enjoyed the training sessions as well as competition and did not want to miss out on<br />

participating. It was pleasing that players believed they were improving and also ‘knew what<br />

they were meant to do’. The coaches have done a great job in ensuring players have fun with the<br />

main strategies being: variety in the session; incorporate skills into games and finishing training<br />

with a game.<br />

Instruction: Instruction consists of pre-instruction, technical explanation, concurrent instruction,<br />

corrective or specific feedback, questioning, positive modelling and negative modelling. The<br />

proportion of time that junior coaches spend instructing their players is 48% or 26.4 minutes.<br />

<strong>Junior</strong> <strong>Community</strong> <strong>Coaching</strong> Report December <strong>2009</strong> 7

Pre-instruction and concurrent instruction each accounted for 14.3% of the training session and<br />

were ranked equal second as the most dominant individual behaviours displayed by junior<br />

coaches. The lengthy duration of instructions suggest that coaches have difficulty giving clear<br />

and concise messages and have a tendency to ‘over-coach’ by continually ‘telling’ and<br />

‘correcting’ their players during training sessions.<br />

o On average there were four occasions during a training session where the coach relates<br />

a practice situation to the game context (technical explanation).<br />

o Only 3-4 questions on average are asked during the training session. This may suggest<br />

that the junior coaches tend not to take a ‘gamesense’ approach incorporating the<br />

appropriate use of questioning for player learning.<br />

o On average only four demonstrations are performed in each session with most being<br />

how to perform the task correctly (positive modelling). It is suggested that junior players<br />

may benefit from observing more frequent demonstrations at training.<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Feedback: Corrective/specific feedback was the most dominant type of feedback displayed by<br />

coaches and accounted for 10.2% of the training session. <strong>Junior</strong> coaches gave feedback 44 times<br />

during an average training session – with an equal number being classified as corrective/specific<br />

or positive feedback (18.5). There was also twice as much positive feedback as negative (2.2: 1).<br />

Interestingly the target of the positive feedback tended to be the group or team (57%) rather<br />

than individual players (11%) while negative feedback, although low, was evenly distributed<br />

between groups and individuals (35%).<br />

Observation was the most dominant single coaching behaviour exhibited by junior coaches and<br />

accounted for 16.8% of training sessions and occurred on an average of 28 separate occasions<br />

during training. These observational periods allow coaches the opportunity to monitor player<br />

performance and contemplate appropriate modifications or interventions.<br />

Management and Organisation: The proportion of time that junior coaches spent organising (or<br />

managing) their players are 13% or 7.1 minutes. This is similar to the time high school coaches<br />

are <strong>report</strong>ed to spent on management but less than that <strong>report</strong>ed at the college and<br />

professional level (< 6.5%). Reducing this time will create further opportunities for players to be<br />

engaged in play or practice activities<br />

Humour (ranked 16 th ) and hustle (ranked 9 th ) were coaching strategies used infrequently by<br />

coaches. On average the coaches would hustle or encourage their players on eight occasions or<br />

3.5% of the training session. This was significantly lower than rates <strong>report</strong>ed in the literature.<br />

<strong>Coaching</strong> style: 61% of junior coaches display an authoritarian leadership style with 59% coaches<br />

displaying a ‘player-centred’ approach compared to 22% that were classified as using a ‘coachcentred’<br />

approach to coaching.<br />

<strong>Coaching</strong> arrangements: the junior coaches preferred the players to participate in various<br />

activities as a whole group (84%) with little pair work or individual practice. On those occasions<br />

when the coaches divided the players into small groups they preferred to have the players<br />

complete the same task. The reliance on ‘whole group’ activities reduces the opportunities<br />

players have to complete specific skills and make decisions.<br />

Interaction with Players: The results indicate that the junior coaches have a healthy interaction<br />

with their players. The majority of coaches are receptive to player suggestions (62%), are<br />

encouraging (89%) and display consistent behaviour (90%).<br />

<strong>Junior</strong> <strong>Community</strong> <strong>Coaching</strong> Report December <strong>2009</strong> 8

Player participation: <strong>Junior</strong> RL and RU coaches could improve their planning and<br />

implementation of their coaching session. This conclusion is based on the following:<br />

55% of the training sessions were rated as performing at an ‘effective’ level of intensity<br />

In 70% of training sessions players were ‘ engaged’ in tasks<br />

56% of training sessions scheduled ‘a lot’ of practice time<br />

64% of training sessions were observed where players were sufficiently attentive<br />

Rating the training session: 48% of the coaches thought that their training session was good and<br />

only 9% thought that it was bad. Further investigation of this revealed that the coaches liked it<br />

when the players tried hard and worked well in the session and when the players listened. In<br />

contrast to this the coaches <strong>report</strong>ed that they disliked it when the players did not turn up to<br />

training or when the players were not concentrating. The main suggestions that coaches put<br />

forward on how the training session could be improved relates to greater player attendance at<br />

training and improved management skills to reduce discipline issues. 68.5% of the coaches<br />

thought that they did meet their stated goals. An interesting aspect of reasons why goals were<br />

or weren’t achieved is the ‘coach centred’ focus of what the coach did in relation to his planning<br />

rather than reasons related to players level of enjoyment, learning or performance.<br />

Coach Perceptions: It appears the coaches grossly over estimate the amount of time that their<br />

players are very active and grossly under estimate the amount of time that their players are<br />

moderately active. This trend is repeated when they reflect on components of the training<br />

session – over-estimating how much time they spend on management, fitness and skill activities<br />

and under-estimating how much instruction they give to players.<br />

Fun: the main strategies coaches employed to ensure that players had fun was incorporating a<br />

variety of different activities (21%) and playing games (38%).<br />

Enjoyment and dissatisfaction: most coaches identified aspects directly involving children as the<br />

most enjoyable part of coaching with 57% indicating “watching kids have fun or improve”. This<br />

was followed by ‘athlete-coach relationships or interactions’ and “teaching”. When asked what<br />

they enjoyed least the broad category of ‘parents’ accounted for over 50% of coach responses.<br />

This included abusive parents, parents emphasis on winning, criticism from parents, and parents<br />

who think their kids are better than what they are. When asked to identify the main issues that<br />

face junior coaches parents were the number one issue followed by an ‘emphasis on winning”<br />

and “discipline issues/trying to manage players”. It seems there is a high level of stress and<br />

pressure which must surely challenge the coach’s motive to continue.<br />

Coach accreditation appeared to have very little influence on the type of training session<br />

conducted in terms of what players did or what behaviours were predominantly displayed by<br />

coaches. However, there were two significant differences. Firstly, coaches with lower<br />

qualifications conduct training sessions that are significantly longer than highly qualified<br />

coaches. This difference equates to 54.5 minute sessions conducted by highly qualified coaches<br />

compared to 62.7 minute sessions conducted by coaches with introductory level qualifications.<br />

Secondly, highly qualified coaches gave more technical explanations.<br />

<strong>Coaching</strong> Experience appears to be more of a discriminator. Results indicate that several<br />

significant differences occur in training sessions conducted by experienced coaches when<br />

compared to those conducted by novice coaches:<br />

experienced coaches spend significantly more time questioning their players.<br />

experienced coaches spend significantly more time in technical explanation.<br />

<strong>Junior</strong> <strong>Community</strong> <strong>Coaching</strong> Report December <strong>2009</strong> 9

experienced coaches were observed showing significantly more enthusiasm than novice<br />

coaches<br />

In training sessions conducted by novice coaches, players have significantly higher levels of<br />

MVPA<br />

However on all other aspects of coaching there was no significant difference between<br />

experienced (> 5yrs) and inexperienced (< 2 yrs) coaches.<br />

Additional Findings with Recommendations<br />

Even when coaches are doing things well, there is always room for improvement. This section will<br />

highlight areas that are causing major concern with coaches and players as well as offering possible<br />

solutions.<br />

1. Management and organisational skills: Coaches are generally well educated on the basics of<br />

creating a good training session. They are not well equipped to execute and manage a session<br />

with a group of very active and chatty players who are there to have fun.<br />

Recommendation to State <strong>Sport</strong>ing Organisation<br />

<br />

<br />

A review of coach education courses is needed to include not only the skills based content,<br />

but content that will give coaches confidence and strategies to cope with discipline issues,<br />

management issues and enhance their ability to give clear concise instructions to players.<br />

Develop workshops specifically for junior coaches that address relevant management and<br />

discipline issues and communication skills that can be conducted in local communities.<br />

Recommendation to the clubs<br />

Encourage all coaches to attend workshops<br />

2. Coach – Parent relationship: Parental input during training sessions and particularly at games<br />

can be detrimental to the well being of the team and the coach. Coaches are not well trained in<br />

how to influence the attitude of parents or to reduce conflict from the side line. This results in<br />

coaches feeling more pressure and less enjoyment.<br />

Recommendation to State <strong>Sport</strong>ing Organisation<br />

Greater support needs to be provided to junior coaches regarding parenting issues. Possible<br />

strategies include:<br />

Create an education package for parents that the individual clubs can use each season to<br />

reduce inappropriate parent behaviour. Issues to be addressed in the package could include:<br />

unreasonable expectations; objectives of junior sport; how parents can support their child<br />

and the coach. This package may include video, handouts, question/answer session. We<br />

recommend a more thorough investigation into this issue to create the most appropriate<br />

education package for parents.<br />

<br />

Develop a parent behaviour self assessment tool<br />

<strong>Junior</strong> <strong>Community</strong> <strong>Coaching</strong> Report December <strong>2009</strong> 10

Provide junior coaches with coping mechanisms for dealing with abuse and criticism. This<br />

module/workshop can be added to the coach education program for new coaches.<br />

Experienced coaches also need to have access to this information.<br />

Emphasise to coaches that effective communication skills will assist in developing positive<br />

relationships with other parents. For example, listening to parents; showing empathy;<br />

communicating clear goals and messages to parents<br />

Offer conflict resolution sessions<br />

Recommendations for clubs<br />

Embrace the new parent education package and introduce it to parents as quickly as<br />

possible.<br />

In the meantime, during the registration process, parents should be reminded of the clubs<br />

overall aims for the season. This will cover the importance of equal participation, enjoyment<br />

for all, respect and learning. A reminder that winning is not the goal, doing your best is, and<br />

other similar ideologies are important to communicate strongly and frequently.<br />

3. Communication and ‘instruction’. In general, communication skills are not a strong point for<br />

junior coaches. In particular there is:<br />

A lack of clear & concise instructions<br />

The role of ‘cues’ doesn’t seem to be used effectively (concurrent instruction)<br />

A belief that coaches need to be continually talking and ‘instructing’ players – ‘observation’<br />

of players is an effective and necessary coaching strategy<br />

Over-coaching<br />

Minimal use of questioning<br />

Minimal evidence that coaches cater for the different learning styles of their players<br />

A need to increase corrective and positive feedback<br />

Recommendation to State <strong>Sport</strong>ing Organisation<br />

<br />

<br />

Communication skills are critical to success. It cannot be assumed that all junior coaches are<br />

naturally good communicators. This is a skill that must be learned. A communication<br />

module must be included in any coach education course. Information on effective<br />

communication and instruction strategies should be supported by various practical<br />

activities and video examples relevant to the junior coach.<br />

Develop a variety of assessment tools that are easy to administer that could be used in the<br />

junior coach setting. An example would be a checklist of variables related to instruction that<br />

a parent or other coach could complete while observing a training session. This would<br />

provide instant and specific feedback to the coach. This could supplement the coach’s own<br />

self-evaluation.<br />

4. Coaches have no baseline for comparison on how effective they are as a coach or how they can<br />

improve. <strong>Junior</strong> coaches have difficulty accurately estimating what happens during a training<br />

session. They tend to over-estimate how active players are and under-estimate how much they<br />

‘talk’ or instruct.<br />

<strong>Junior</strong> <strong>Community</strong> <strong>Coaching</strong> Report December <strong>2009</strong> 11

Recommendation to State <strong>Sport</strong>ing Organisation<br />

<br />

Create formal and informal mentoring activities – provide opportunities for coaches to<br />

observe other junior training sessions; consider establishing a pool of mentors and<br />

developing a system that provides access to e-mentors.<br />

Develop guidelines on how to develop and implement ‘coaching communities’. Provide<br />

support (1-2hr workshop) on facilitation role. Meetings could be scheduled on the Saturday<br />

before competition starts, once during the season (a non-playing Saturday) and the <strong>final</strong><br />

Saturday. Saturdays that are cancelled due to wet weather may also be used. These<br />

meetings provide coaches with an opportunity to support each other and work through<br />

common issues. Examples may include:<br />

o Planning and conducting training sessions that everyone then tries with their own team<br />

(agree on goals, content etc)<br />

o Working on one problem at a time e.g. player concentration levels<br />

Develop guidelines to assist junior coaches in assessing their own performance and<br />

developing effective self reflective skills.<br />

Suggest an evaluation system for coaches. This may include the identification of 2 things<br />

under the following 3 headings –<br />

o What I need to start doing<br />

o What I need to stop doing<br />

o What I need to keep doing<br />

These can be determined by the coach themselves or in consultation with mentor, other<br />

coaches or ‘assistant’ parents<br />

5. Training Session. Prior planning and continual learning will assist coaches in providing players<br />

with greater opportunities for deliberate ‘play’ (games) and practice.<br />

Recommendation to State <strong>Sport</strong>ing Organisation<br />

Provide an online resource available to assist coaches with planning and selection of<br />

activities for training sessions. This would expand on what is available at the rugby’s online<br />

coaching centre. Relevant and specific games, activities and drills would be included in<br />

written and video form. An example in another sport is available at<br />

www.globalfootballsystems.com This online resource could be available free for all<br />

registered coaches (accessed through a login) or for a small fee paid by each club and<br />

available to all their coaches.<br />

Consider adopting a ‘long term athlete development’ or ‘development model of sports<br />

participation’ framework. This would encourage a greater emphasis on ‘games’ play for 9-12<br />

year olds.<br />

Encouragement of small group activities to increase player involvement and decision-making<br />

opportunities. This would supplement whole group activities. The minimal use of small<br />

group work at training may be a reflection on the over-emphasis on team ‘runs’ where<br />

<strong>Junior</strong> <strong>Community</strong> <strong>Coaching</strong> Report December <strong>2009</strong> 12

coaches believe they must run as a team for lengthy periods. Examples to be included in<br />

coach education courses and the e-resources.<br />

Reinforce the importance of a ‘cool down’. As well as being ‘good’ practice in terms of<br />

recovery it is an ideal time where coaches can summarise the main points learnt during the<br />

training session.<br />

6. Coach frustration with low numbers at training. Coaches lack the adaptability to change<br />

training plans quickly to meet new situations. Coaches appear to lack confidence and skills in<br />

running small group activities.<br />

Recommendation to State <strong>Sport</strong>ing Organisation<br />

<strong>Junior</strong> coaches need to be given suggestions for events such as reduced player numbers at<br />

training so contingency plans can be formulated. This information can be discussed and<br />

demonstrated at coaching courses and made available on the junior coaching website.<br />

7. Support. The coaches feel they have a lack of support and often feel isolated<br />

Recommendation to State <strong>Sport</strong>ing Organisation<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Provide a blog where junior coaches could communicate and share ideas and experiences<br />

Provide access to an e-mentor: junior coaches are able to ask questions and receive advice<br />

on specific junior coaching issues<br />

Demonstrate to coaches how they can include other parents by setting roles and<br />

boundaries. An example would be having parents as ‘assistants’ to supervise small group<br />

activities. If parents have a role and can contribute at training they are more likely to be<br />

positive and supportive.<br />

8. Coach Education. A review of the effectiveness of current coach education courses. This will<br />

involve interviewing graduates from the previous two years to determine the relevance and<br />

applicability of knowledge gained from the courses.<br />

Recommendation<br />

Consideration should be given to both the delivery and content of coach education.<br />

Suggestions include -<br />

Player centred (rather than coach centred)<br />

Problem-based learning – emphasis on ‘How’ as well as ‘what’<br />

Communication skills<br />

Management and organisational skills<br />

<strong>Junior</strong> <strong>Community</strong> <strong>Coaching</strong> Report December <strong>2009</strong> 13

Chapter 1<br />

Introduction<br />

Traditionally sports in Australia have developed coach accreditation and education programs to<br />

improve the quality of junior sports coaching. However ABS statistics suggests that a significant<br />

number of junior coaches do not attend or complete accreditation courses. Also the assessment of<br />

the competency of coaches who complete an accreditation course does not provide information<br />

about what actually happens at training once those coaches go into the field.<br />

By developing a greater understanding of what is happening during typical junior coaching sessions it<br />

will be possible to identify any strengths and possible deficiencies of the coaching experience. Once<br />

data relating to any strengths and deficiencies has been thoroughly analysed it may be possible to<br />

develop systems that will improve the quality of junior coaching in the community setting resulting<br />

in coaches having an even greater impact on young athletes' development and enjoyment of sport<br />

(Hedstrom & Gould, 2004).<br />

Aim and Objectives of the Research<br />

The aim of the research was to conduct an investigation to develop a deeper understanding of the<br />

makeup of junior Rugby League and Rugby Union coaching sessions. Specifically the research<br />

revolved around the following objectives:<br />

1. Determine the proportion of time junior coaches spend organising their players<br />

2. Determine the proportion of time junior coaches spend instructing their players<br />

3. Determine how active players are during a coaching session<br />

4. Determine how often players get to practise performing the skills of the game<br />

5. Determine if coaches have an accurate understanding of how active their players are during a<br />

coaching session<br />

6. Determine how different levels of coach accreditation and the experience of the coaches<br />

impacts on player activity levels, instruction time and group management time.<br />

In order to fully investigate the objectives of the study, an approach was needed that would not only<br />

enable the researchers and key stakeholders to fully understand the coaching environment and its<br />

effect on players, but also one that would give valid and reliability results. One such approach is<br />

systematic observation, and it is this approach that forms the basis of the methods used in the<br />

study.<br />

Methodologies<br />

Using methods of convenient sampling (Gall et al, 1996) the study involved 444 participants in total,<br />

37 coaches and 407 under ten players from both rugby union and rugby league teams around the<br />

greater Sydney area. Systematic observation of these coaches and their respective teams was<br />

undertaken twice during the <strong>2009</strong> season.<br />

Two research assistants visited each training session with one assistant systematically observing the<br />

session using the System for Observing Fitness Instruction Time (SOFIT) (McKenzie, Sallis and Nader,<br />

1991). The other research assistant videotaped the session to enable the training session to be<br />

<strong>Junior</strong> <strong>Community</strong> <strong>Coaching</strong> Report December <strong>2009</strong> 14

viewed and coded at a later date using an observational instrument adapted from the Coach<br />

Behavioural Assessment System (Smith, Smoll and Hunt, 1977) combined with the Arizona State<br />

University observation instrument (Lacy and Darst, 1984). Data was also collected at these sessions<br />

via pre and post session coach interviews and using an adapted Player Enjoyment Scale (Motl, et al.,<br />

2001). Following the session the two research assistants also completed the Rating Scale for<br />

<strong>Coaching</strong> Sessions (Liukkonen, Laakso & Telama, 1996).<br />

Report Outline<br />

The research activities and findings of the study are presented in the subsequent chapters. In<br />

Chapter 2 a synthesis of the literature reviewed is provided to form a theoretical and practical basis<br />

for the study.<br />

In Chapter 3 an overview of the research methodology, is presented, followed by the specific<br />

procedures used in this study.<br />

Chapter 4 presents the analysis of data relating to the aims and objectives of the research. It begins<br />

with a descriptive overview of the participants in the study i.e., the coaches and players. It then<br />

presents the findings in relation to the following five areas:<br />

• Players’ in Action<br />

• Players’ Reflections on the Training Session<br />

• Coaches’ in Action<br />

• Coaches’ Reflections on the Training Sessions<br />

• Comparisons between the Data<br />

Chapter 5 summarises the research, discusses the major outcomes of the study and presents issues<br />

and recommendations for the state sporting organisations and clubs. Guidelines for effective<br />

training sessions are also outlined.<br />

<strong>Junior</strong> <strong>Community</strong> <strong>Coaching</strong> Report December <strong>2009</strong> 15

Chapter 2<br />

Literature Review<br />

This chapter presents a synthesis of the literature that was reviewed to form the theoretical and<br />

practical foundation for this study. The review is divided into three main focus areas. The first area<br />

looks at junior sport generally; the second area examines research related to players and the section<br />

critiques relevant literature related to coaches.<br />

<strong>Junior</strong> <strong>Sport</strong> Coaches and <strong>Junior</strong> <strong>Sport</strong><br />

<strong>Coaching</strong> is potentially a very gratifying pursuit as a result of working with aspiring athletes, the<br />

challenge of constructing an effective program, the fulfilment derived from teaching sport skills, and<br />

the opportunity to facilitate athletes' psychosocial development (Raedeke, 2004). In particular, the<br />

junior sport coach can have a significant impact on young athletes' development and enjoyment of<br />

sport (Hedstrom & Gould, 2004). Furthermore, the contemporary epidemic of inactivity and obesity<br />

in Australian children means there is potential for youth sports and their coaches to have a<br />

significant impact in this area in the future (Hedstrom & Gould, 2004). Paradoxically, little<br />

educational, social, financial, and psychological support exists for the development and retention of<br />

community junior sport coaches given their importance to the overall development of young<br />

athletes. Considering the importance of the coach in determining the quality and success of an<br />

athlete's sport experience, the existence of information that specifically relates to ‘best practice’,<br />

and the development and retention of community junior coaches is surprisingly negligible.<br />

Research indicates that coaches can influence whether the junior player has a positive or negative<br />

sports experience (Gilbert, Gilbert and Trudel, 2001; Hedstrom and Gould, 2004). Smith, Smoll and<br />

colleagues (Smith, Smoll and Curtis, 1979; Smith et al., 1993; Smith and Smoll, 2002) have been the<br />

leading researchers in investigating how coaching behaviours influence an athletes’ satisfaction.<br />

Their research suggests that players with a trained coach display increased motivation, self esteem,<br />

and satisfaction with their coach, teammates and the season. Coaches must also be aware that<br />

children (8-12 years) perceive their competence in relation to peer comparison so feedback must be<br />

task oriented rather than performance focused (Horn and Harris, 2002).<br />

Developmental Model of <strong>Sport</strong> Participation<br />

The Under 10’s age group investigated in this study is part of the ‘sampling years’ (6-12 years) within<br />

the Developmental Model of <strong>Sport</strong> Participation (Cote, Baker and Abernethy, 2003) where an<br />

emphasis on diversity of sport and a focus on deliberate play activities is important in developing<br />

player perceptions of competence which contribute to continued participation (Kirk, 2005). Table 2-<br />

1 outlines the three stages that players progress towards elite performance. Deliberate play<br />

activities are aimed at maximizing player fun and enjoyment and are intrinsically motivated.<br />

Deliberate play provides opportunities for players to experiment and be creative “without being told<br />

the right way to execute a skill” (Cote and Fraser-Thomas, 2008, p20). It has been suggested that an<br />

over-emphasis on deliberate practice during the sampling years can lead to sport drop out, burn-out,<br />

injuries and decreased enjoyment (p. 21).<br />

<strong>Junior</strong> <strong>Community</strong> <strong>Coaching</strong> Report December <strong>2009</strong> 16

Table 2-1 Suggested percentage of time and number of sports during the three stages of the DMSP.<br />

Stage Deliberate Play /<br />

other sport activities<br />

(% involvement)<br />

Sampling<br />

(age 6-12 years)<br />

Specialising<br />

(age 13 – 15 years)<br />

Investment<br />

(age 16 – 22 years)<br />

Deliberate Practice<br />

(% involvement)<br />

No. of other sports<br />

80 20 3 – 4<br />

50 50 2 – 3<br />

20 80 1 - 2<br />

Lyle (2002) suggests that ‘participation coaching’ is sports leadership and teaching, with the purpose<br />

of providing initial experiences in sport for athletes. Competition and performance elements are not<br />

emphasised during the sampling years. Rather the focus is on fundamental movement skills and<br />

trialling different ways to execute skills that can be transferred across different sports. <strong>Junior</strong><br />

coaches need to avoid ‘over coaching’ 6-12 year old players.<br />

Cote (2008) suggests that junior participation coaching should focus on the 4 ‘C’s’: Competence,<br />

Confidence, Connection and Character. Specifically he recommends that junior coaches -<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Adopt an inclusive focus as opposed to an exclusive selection policy based on performance.<br />

Organize a mastery-oriented motivational climate.<br />

Set up safe opportunities for athletes to have fun and engage playfully in low-organization<br />

games.<br />

Teach and assess the development of fundamental movements by focusing on the child first.<br />

Promote social aspect of sport and sampling.<br />

Cote (2008) divided the coaches required knowledge into two domains -<br />

<strong>Sport</strong> specific knowledge: include technical, tactical, mental, pedagogical, training, nutrition, etc.<br />

Interpersonal knowledge: individual and group interactions with children, adolescents, and<br />

adults (i.e. coach-athletes, coach-parents, coach-assistants relationships, etc.).<br />

The reliance on these two knowledge domains varies throughout the stages of the DMSP (Fig 2-1)<br />

120<br />

100<br />

80<br />

60<br />

40<br />

interpersonal knowledge<br />

sport knowledge<br />

20<br />

0<br />

sampling specialising investment<br />

Figure 2-1 The Allocation of Interpersonal and <strong>Sport</strong> Specific Knowledge<br />

<strong>Junior</strong> <strong>Community</strong> <strong>Coaching</strong> Report December <strong>2009</strong> 17

Players in Action<br />

Currently in Australia and in similar western societies, the levels of physical activity of adolescents<br />

are declining at faster rates than ever before (Booth et al., 2006). In order to combat this decline the<br />

Australian government through the Active Kids are Healthy Kids campaign (Department of Health<br />

and Ageing, 2004) has decided to focus on improving the physical activity levels of adolescences. The<br />

recommendations in the campaign are intended to make public the minimum level of physical<br />

activity required for good health in children. These recommendations were based upon the best<br />

available evidence and are also in line with international best practice. The campaign states that<br />

Australian children should get a minimum of 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity<br />

(MVPA) a day, with MVPA being defined as a brisk walk and above (Department of Health and<br />

Ageing, 2004). The importance and opportunity that the junior sport environment plays in meeting<br />

these national guidelines is an area that has not been fully explored and an area that the current<br />

literature that this study can fill.<br />

Another area of concern identified in Booth et al.’s NSW Schools Physical Activity and Nutrition<br />

Survey (2006) is the low ability level of adolescents to perform and master the fundamental<br />

movement skills (FMS) which underlie all sports (e.g., passing running, kicking, dodging etc). This<br />

finding not only has implications for schools in NSW but also other areas where these skills are<br />

regularly performed i.e., the junior coaching environment where the FMS are regularly taught and<br />

practiced.<br />

Research also indicates that the time taken for adolescents to master a single fundamental<br />

movement skill ranges from 280 minutes to 600 minutes (NSW Department of Education and<br />

Training, 2000). The role the junior sport environment can potentially play in developing these FMS<br />

is significant, especially considering the frequency and duration of junior training sessions<br />

throughout a year. Research on this however is limited.<br />

The benefit of <strong>Junior</strong> <strong>Sport</strong> Participation<br />

<strong>Junior</strong> coaches play a critical role in providing opportunities for players to develop motor skills,<br />

physical health and psychosocial skills such as self concept, cooperation, responsibility, self-control<br />

and empathy (Fraser-Thomas and Cote, 2006; Malina and Cumming, 2003; Seefeldt, Ewing and Walk,<br />

1992; Weiss and Stuntz, 2004). Evidence suggests youth sport participation provides an ideal<br />

environment for developing life skills (Gould, Collins, Lauer and Cheung, 2008) and fostering<br />

cognitive development (Pool and Miller, 2006). Similarly it has been suggested that coaches who use<br />

appropriate reinforcement and praise; encourage players after mistakes; and use effective<br />

instructions are most likely to enhance player psychological development. Participation in junior<br />

sport can also contribute to normal growth and development and enhance aerobic fitness, strength<br />

and skill development (Fraser- Thomas et al., 2005).<br />

Unfortunately there is also the negative aspects of junior sport participation particularly when a ‘win<br />

at all costs’ mentality is prevalent. This can lead to unhealthy levels of aggression and stress and<br />

contribute to player burnout and withdrawal. If players encounter competition or advanced skill<br />

work too soon they will experience increased anxiety and decreased self esteem.<br />

<strong>Junior</strong> <strong>Community</strong> <strong>Coaching</strong> Report December <strong>2009</strong> 18

It has been <strong>report</strong>ed that US youth players are more likely to drop out of sport if their coaches are<br />

autocratic, less encouraging and place a heavy emphasis on winning (Salminen and Liukkonen,<br />

1996). In Australia the main reasons for dropping out of sport are: no time for other interests, the<br />

sport isn’t fun anymore, conflict with the coach, the coach played favourites or was a poor teacher<br />

(ABS, 2008).<br />

Coaches in Action<br />

There is a dearth of empirical based research evidence in support of coaching practice. Although<br />

there is an extensive knowledge base regarding physical education teachers there is a paucity of<br />

literature concerning coaching effectiveness and the training of junior coaches. Successful coaches<br />

are not only knowledgeable in the techniques or skills of their sport; they also know how to teach<br />

those skills to athletes. Crucial to enhancing performance is how the coach facilitates learning in the<br />

athlete. Systematic observation instruments have been used in previous research to identify the<br />

behaviours that coaches demonstrate in their coaching practice. “Systematic observation allows a<br />

trained person following stated guidelines and procedures to observe, record, and analyse<br />

interactions with the assurance that others viewing the same sequence of events would agree with<br />

his (or her) recorded data” (Darst, Mancini and Zakrajsek, 1983, p.6).<br />

1. Instructions<br />

Case study research on coaches at various levels confirms that the behaviours of effective coaches<br />

consist of a high percentage of instructional strategies – questioning, feedback, explanations,<br />

demonstrations and analysis (Cushion and Jones, 2001; Lacy and Darst, 1985; Millard, 1996). The<br />

Table below indicates that coaches spend 19 – 58% of a training session ‘instructing’ their players.<br />

Table 2-2 Percentage of a Practice Session that coach’s spend ‘instructing’ players<br />

Level of sport sport % training spent on<br />

‘instruction’<br />

Reference<br />

College Basketball 62.7 Tharpe & Gallimore<br />

(1976)<br />

Professional Soccer 59.8 Potrac et al (2007)<br />

Youth Soccer 58.2 Cushion & Jones (2001)<br />

Elite Soccer 50.3 Vangucci et al (1997)<br />

Youth Various 43.3 Liukkonen et al (1996)<br />

Youth Football 43.3 Seagrave & Ciancio<br />

(1990)<br />

High School Volleyball 23 Stewart & Bengier (2001)<br />

College Volleyball 19.6% Lacy & Martin (1994)<br />

However Fisher, Mancini, Hirsch, Proulx & Straurowsky (1982) <strong>report</strong>ed that coaches from less<br />

satisfied teams gave 70% more information to their athletes than did coaches in the more satisfied<br />

environments. This strongly suggests that effective coaching is linked more to the quality (how and<br />

<strong>Junior</strong> <strong>Community</strong> <strong>Coaching</strong> Report December <strong>2009</strong> 19

when) rather than to the sheer quantity of instruction provided to athletes. In all probability<br />

coaching expertise is not a function of increasing or decreasing certain behaviours. Rather it is<br />

having the ability to make the correct decisions within the constraints of the training environment.<br />

Consequently coaching can be classified as a cognitive skill that can be taught.<br />

Liukkonen, Laakso & Telama (1996) assessed the coaching behaviours of 128 youth sport coaches in<br />

Finland. Using systematic observation and a rating scale for coaching sessions they found that twothirds<br />

of the session comprised of instructions, modelling and assisting performance, and<br />

observation. Interestingly there was little feedback given (positive or negative), activities were<br />

mainly to the whole group with instructions given in an authoritarian manner, and little interaction<br />

among players.<br />

Previous studies have indicated that questioning and demonstrations are often infrequently used by<br />

coaches (Bloom, Crumpton and Anderson, 1999; Claxton, 1988; Mesquita, Sobrinho, Rasado, Pereira<br />

and Milisted, (2008); Potrac et al., 2007). However both strategies have been recommended as<br />

teaching approaches that will assist athlete learning.<br />

In his review of 56 studies that used systematic observation of coaching behaviours, Kahan (1999)<br />

found that coaches engage in a cycle of spontaneous and reactive behaviour that can be described<br />

as “initial instruction which may include demonstration by the coach, silent observation of player<br />

performance, concurrent or terminal-feedback possibly coupled with hustle - or encouragement<br />

statements, further observation of player performance, and repletion of the cycle until the task is<br />

changed” (p. 41). The majority of these studies used either the Arizona State University Observation<br />

Instrument or the <strong>Coaching</strong> Behaviour Assessment Scheme to code coaching behaviours, with each<br />

coach being observed for an average of 5.5 hours (2-4 training sessions).<br />

2. Management<br />

Another major behaviour category assessed during systematic observation studies has been<br />

management. Table 2-3 summarises the amount of time coaches spend managing or organising<br />

players during practice sessions.<br />

Table 2-3 Percentage of Practice session spent in management<br />

Level of sport sport % training spent on<br />

‘management’<br />

Reference<br />

High School Basketball 15.3 Lacy & Goldston (1994)<br />

High School Volleyball 14.8 Stewart & Bengier (2001)<br />

High School Baseball 14.6 Rupert & Buchner (1989)<br />

Professional Soccer 6.2 Potrac et al (2007)<br />

College Volleyball 6.4 Lacy & Martin (1994)<br />

Elite Soccer 5.2 Vangucci et al (1997)<br />

<strong>Junior</strong> <strong>Community</strong> <strong>Coaching</strong> Report December <strong>2009</strong> 20

Coach enjoyment and retention<br />

Despite the important role of coaches in youth sport, participation rates have been decreasing<br />

throughout the world (Coleman, 2002; Yamaguchi & Takahashi, 2000). It is therefore important to<br />

understand the motivations which underpin coaches' involvement in a given sport in order to ensure<br />

that sporting organisations can attract and ensure the success of volunteers within their given roles<br />

(Coleman, 2002).<br />

This research will also attempt to find out what coaches derive enjoyment from and what causes<br />

dissatisfaction so organisations are able to assist with the development and retention of these<br />

coaches. It has previously been <strong>report</strong>ed that coach motivations were derived from personal<br />

characteristics and experiences within the sport, interest in working with young people, and wanting<br />

to remain involved in sport in some capacity (Sage, 1989; Schinke et al., 1995; Salmela, 1995).<br />

Similarly, Walsh (2004) noted that participation in sport as an athlete and desire to maintain<br />

involvement in the sport were the primary reasons for beginning coaching in Australia. Additionally,<br />

family involvement in the sport; wanting to offer something back to the sport and an academic<br />

background relating to sport had a strong influence on a coach’s decision to begin coaching (Walsh,<br />

2004). Reasons that contribute to coaches deciding to continue to be a volunteer coach include:<br />

helping others to improve (39%), enjoyment (29%), making a contribution to sport (19%) and<br />

achievement/success (8%).<br />

Current evidence highlights the immense pressure to sustain coach involvement in youth sport<br />

programs over an extended period of time. When you consider the work, family and coaching<br />

commitments that must be balanced, it is perhaps possible that the youth sport coach may<br />

experience burnout from the following stressors: increased work demands, excessive workloads,<br />

conflicting roles, high expectations, and striving to satisfy everyone's needs.<br />

Summary<br />

In summary, there is very little empirical evidence on what constitutes an effective junior sport<br />

training session. Systematic observation instruments are a valid and reliable way to assess coaching<br />

behaviours. The first step in developing guidelines for effective youth coaching is identifying what<br />

coaches currently do. However to gain a greater understanding of player skill development it has<br />

been suggested that player activity (on-task behaviour, skill attempts etc) as well as coach behaviour<br />

be observed and analysed (Lacy and Martin, 1994). As the majority of studies designed to examine<br />

coaching behaviour and player outcomes have involved male coaches and male athletes from the US<br />

and UK, caution must be taken in generalizing those results to Australian junior coaches.<br />

<strong>Junior</strong> <strong>Community</strong> <strong>Coaching</strong> Report December <strong>2009</strong> 21

Chapter 3<br />

Methodology Underlying the Research<br />

This chapter details the research methodology utilised to investigate the aims and objectives of the<br />

study. The chapter begins with a literature review of the research methodology and instruments<br />

used in the study, along with justification for their choice. The chapter concludes with a discussion of<br />

the ethical considerations and a summary of the methods used to ensure the reliability and validity<br />

of the research.<br />

Ethical Considerations<br />

This study was conducted using the ethical guidelines implemented by the University of Sydney. It<br />

was important for the research to follow these strict ethical guidelines in order to protect the rights<br />

of participants, and ensure that the research was conducted in a fair and equitable manner.<br />

Approval was granted from the University of Sydney’s Human Research Ethics Committee. All of the<br />

participants in this study were informed of the nature and extent of the research prior to its<br />

commencement and signed consent forms. As this research involved video-taping the training<br />

session consent from the coach and all players’ parents/guardians needed to be attained for that<br />

team to be included in the study.<br />

Participant Recruitment<br />

Participants were recruited from the Sydney metropolitan area through the NSW Rugby League and<br />

Australian Rugby Union Associations. All teams competing in the <strong>2009</strong> RL and RU Under 10s age<br />

division were invited to participate in the study.<br />

Instruments<br />

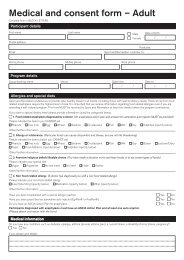

The project incorporated the use of five instruments. An overview of these instruments can be seen<br />

below<br />

1. System for Observing Fitness Instruction Time (SOFIT)<br />

The System for Observing Fitness Instruction Time (SOFIT) is a previously validated momentary time<br />

sampling and an interval recording system (McKenzie, Sallis, & Nader, 1991) that uses a three-phase<br />

decision system to examine how active athletes are, how coaches spend their time during training<br />

sessions and in the case of this study what skills were performed during the training session.<br />

Phase 1 of the process involves making a judgment on the activity level of the athletes. This is made<br />

by observing preselected players (one at a time) and determining their level of physical activity<br />

periodically (every 20 seconds) throughout the training session. Phase 2 of the decision sequence<br />

involves coding the context of the training session being observed. At the end of each observation<br />

interval (20 seconds), a decision is made whether training time is being allocated to management,<br />

imparting knowledge, fitness, skills practice, or playing games. The <strong>final</strong> modified phase, Phase 3,<br />

involves coding what specific rugby skills the players performed during the session.<br />

SOFIT (McKenzie, Sallis, & Nader, 1991) is widely used, and its activity codes have been validated for<br />

use with adolescents (Rowe, Van der Mars, Schuldheisz, & Fox, 2004) through heart rate monitoring.<br />

<strong>Junior</strong> <strong>Community</strong> <strong>Coaching</strong> Report December <strong>2009</strong> 22

2. Activity Enjoyment Scale (S-PACES)<br />

The Short Form - Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale (S-PACES) includes 9 items which athletes rate<br />

themselves on a five-point Likert scale (See Appendix 1). The scale measures the amount of<br />

enjoyment the athletes perceive themselves to have experienced during an exercise activity. Motl,<br />

et al. (2001) found PACES to be a reliable measure of physical activity enjoyment and concluded that<br />

the scale had both factorial and construct validity. The scale was considerably adapted for rugby<br />

situations by using rugby terminology.<br />

The instrument was administered directly after each observed training session by trained research<br />

assistants.<br />

3. Pre and Post Session Semi Structure Interviews<br />

In order to consolidate the information gained from observing the coaches and to provide<br />

corroboration of the data from other sources, interviews were conducted before and after every<br />

training session.<br />

Patton (2002) described the usefulness of interviewing by stating that.<br />

“We interview people to find out from them those things we cannot directly observe. The<br />

issue is not whether observational data is more desirable, valid or meaningful than self<strong>report</strong><br />

data. The fact of the matter is that we cannot observe everything. We cannot<br />

observe feelings thoughts and intentions. We cannot observe behaviours that took place<br />

at some previous point in time. We cannot observe situations that preclude the presence<br />

of an observer. We cannot observe how people have organised the world and the<br />

meanings they attach to what goes on in the world. We have to ask people questions<br />

about those things” (p. 278).<br />

The interviews in this project followed a semi-structured guide (see Appendix 2), and were aimed at<br />

exploring issues related to the aims and objectives of the research. As suggested by Minichiello,<br />

Aroni, Timewell, & Alexander (1995) the structure of the interview also allows enough flexibility for<br />

participants (i.e. coaches) to express a range of individual perceptions regarding their experiences.<br />

Specifically the interview guide raised issues pertaining to:<br />

• The coach’s experience and qualifications in coaching rugby<br />

• What the coaches planned to do during the session (asked prior to the session)<br />

• How successful the coach thought their training sessions were and why<br />

• The coaches thoughts on coaching in general<br />

At the beginning of the interview the coaches were asked if they had any objections to having the<br />

interview recorded. They were advised that their comments would be recorded anonymously, and<br />

they would not be identified individually. All of the coaches agreed to the recording process, thus all<br />

interviews were recorded ensuring an accurate record was obtained.<br />

4. Coach Rating Scale<br />

A modified version of the Rating Scale for coaching sessions (Liukkonen, Laakso & Telama, 1996) was<br />

completed at the conclusion of the training session by trained research assistants (see Appendix 3).<br />

The rating scale for coaches includes aspects such as teaching arrangements, communication skills,<br />

working methods, interaction between coach and athlete, and engagement in tasks. For example,<br />

<strong>Junior</strong> <strong>Community</strong> <strong>Coaching</strong> Report December <strong>2009</strong> 23

organizational skills are rated on a 5 point scale from poor (1) to good (5); persistence of behaviour<br />

is rated from inconsistent (1) to consistent (5).<br />

5. Systematic Video Observation<br />

The researchers developed the <strong>Junior</strong> <strong>Coaching</strong> Observation instrument by combining categories<br />

from the Coach Behavioural Assessment System (Brewer and Jones, 2002) and the Arizona State<br />

University Observation Instrument (Lacy and Darst, 1984). The combination of these two valid and<br />

reliable observational instruments resulted in data being collected on 17 behavioural categories:<br />

instruction – pre-instruction, concurrent, technical; demonstration – positive modelling, negative<br />

modelling; feedback – corrective/specific, general, positive, negative; questioning; hustle<br />

(encouragement); management/organisation; observation; humour; time off task. Table 3-1 outlines<br />

the definition for each behavioural category.<br />

The validity of systematic observation instruments are well documented in the literature. As the<br />

<strong>Junior</strong> <strong>Coaching</strong> Observation instrument was adapted from two previously validated instruments the<br />

content validity was confirmed by a group of twelve experienced coaches enrolled in a Masters<br />

degree. Reliability was ensured by conducting training sessions with the ‘coders’ prior to any formal<br />

coding of the data. Reliability was also improved from previous studies as the training sessions were<br />

video recorded rather than coded in ‘real’ time. This allowed the research assistant to observe,<br />

pause and review (in slow motion if required) behaviours prior to coding. The inter and intra<br />

reliability coefficient was measured using a Spearmen correlation calculation and returned values of<br />

0.895 and 0.864 respectively, indicating that the <strong>Junior</strong> <strong>Coaching</strong> Observation instrument is a reliable<br />

tool.<br />

<strong>Junior</strong> <strong>Community</strong> <strong>Coaching</strong> Report December <strong>2009</strong> 24

Table 3-1 A description of the behaviours used in the Video Observation<br />

Behaviour<br />

Pre-Instruction<br />

Concurrent instruction<br />

Technical Explanation<br />

Questioning<br />

Positive modelling<br />

Negative modelling<br />

Positive feedback<br />

Negative feedback<br />

General feedback<br />

Corrective feedback or specific<br />

feedback<br />

Hustle<br />

Scold<br />

Humour<br />

Management/organisation<br />

Observation<br />

Not on task / conferring with<br />

others<br />

Uncodable<br />

Definition<br />

Initial information given to player(s) preceding the desired action<br />

to be executed. It explains how to execute the skill, play, task or<br />

drill that it precedes<br />

Cues or reminders given during the execution of the skill or play.<br />

The coach rationalises through explanation of how the practices<br />

that are being undertaken would relate to the game situation<br />

either from a technical (technique) or strategically (tactical)<br />

basis: “From this situation in a game you would …”<br />

Any question to player(s) concerning strategies, techniques,<br />

assignments, etc. associated with the sport<br />

A demonstration of correct performance of a skill or playing<br />

technique<br />

A demonstration of incorrect performance of a skill or playing<br />

technique<br />

positive feedback (verbal or non-verbal) in the form of<br />

demonstrations of satisfaction or pleasure, at a skill or practice<br />

attempt: “Good”, pat on back, smile<br />

Verbal or nonverbal feedback demonstrating displeasure at the<br />

players’ skill or practice attempt of the drill, skill or play: “That’s<br />

awful”<br />

Nonspecific feedback (verbal or non-verbal)<br />

Information, re-explanation or feedback regarding the actual<br />

performance of the drill, skill or play which informs the player of<br />

how the performance should be altered in order to improve:<br />

“Get lower” OR<br />

feedback of a specific nature given to the player(s) following the<br />

execution of a specific skill or task: “The timing of that pop pass<br />

was excellent”<br />

Verbal statements intended to intensify the efforts of the<br />

player(s)<br />

Verbal or non-verbal behaviours of displeasure<br />

Verbal statements related to organizational details of practice<br />

sessions not referring to strategies or fundamentals of the sport<br />

Periods of diagnostic observation when the coach is not talking<br />

and is observing the players and analysing their execution of the<br />

skill or activity or observing the way in which a team is executing<br />

strategies in open play situations<br />

Any behaviour that cannot be seen or heard or does not fit into<br />

the above categories<br />

Adapted from the Arizona State University Observation Instrument (Lacy & Darst, 1984, pp. 59-66) and the Rugby Union<br />

Coaches Observation Instrument (Brewer & Jones, 2002, pp. 148-150)<br />

<strong>Junior</strong> <strong>Community</strong> <strong>Coaching</strong> Report December <strong>2009</strong> 25