post-splenectomy vaccine prophylaxis - SurgicalCriticalCare.net

post-splenectomy vaccine prophylaxis - SurgicalCriticalCare.net

post-splenectomy vaccine prophylaxis - SurgicalCriticalCare.net

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

DISCLAIMER: These guidelines were prepared by the Department of Surgical Education, Orlando Regional Medical Center. They<br />

are intended to serve as a general statement regarding appropriate patient care practices based upon the available medical<br />

literature and clinical expertise at the time of development. They should not be considered to be accepted protocol or policy, nor are<br />

intended to replace clinical judgment or dictate care of individual patients.<br />

POST-SPLENECTOMY VACCINE PROPHYLAXIS<br />

SUMMARY<br />

The splenectomized patient should be vaccinated to decrease the risk of overwhelming <strong>post</strong><strong>splenectomy</strong><br />

sepsis (OPSS) due to organisms such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae type B,<br />

and Neisseria meningitidis. Patients should be educated prior to discharge on the risk of OPSS and their<br />

immunocompromised state. An understanding of the need for prompt medical attention should be<br />

instilled in such patients to reduce the morbidity and mortality of <strong>post</strong><strong>splenectomy</strong> infection.<br />

RECOMMENDATIONS<br />

• Level 1<br />

‣ None<br />

• Level 2<br />

‣ Non-elective <strong>splenectomy</strong> patients should be vaccinated on or after <strong>post</strong>operative day 14.<br />

‣ Asplenic patients should be revaccinated at the appropriate time interval for each <strong>vaccine</strong>.<br />

• Level 3<br />

‣ Elective <strong>splenectomy</strong> patients should be vaccinated at least 14 days prior to the operation.<br />

‣ Asplenic or immunocompromised patients (with an intact, but nonfunctional spleen) should be<br />

vaccinated as soon as the diagnosis is made.<br />

‣ Pediatric vaccination should be performed according to the recommended pediatric dosage<br />

and <strong>vaccine</strong> types with special consideration made for children less than 2 years of age.<br />

‣ When adult vaccination is indicated, the following vaccinations should be administered:<br />

o Streptococcus pneumoniae<br />

• Polyvalent pneumococcal <strong>vaccine</strong> (Pneumovax 23)<br />

o Haemophilus influenzae type B<br />

• Haemophilus influenzae b <strong>vaccine</strong> (HibTITER)<br />

o Neisseria meningitidis<br />

• Age 16-55: Meningococcal (groups A, C, Y, W-135) polysaccharide diphtheria toxoid<br />

conjugate <strong>vaccine</strong> (Menactra)<br />

• Age >55: Meningococcal polysaccharide <strong>vaccine</strong> (Menomune-A/C/Y/W-135)<br />

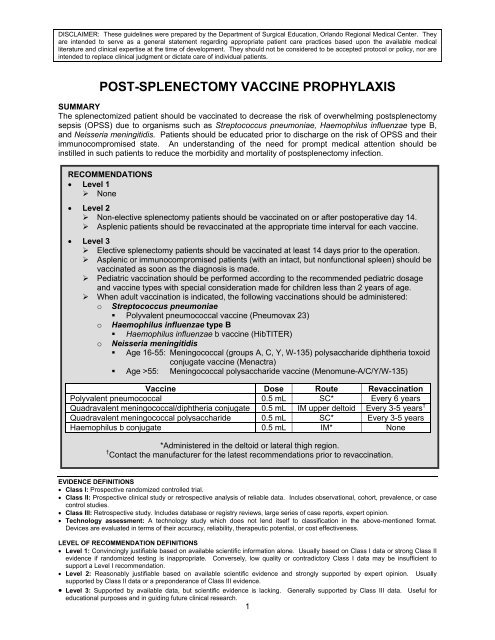

Vaccine Dose Route Revaccination<br />

Polyvalent pneumococcal 0.5 mL SC* Every 6 years<br />

Quadravalent meningococcal/diphtheria conjugate 0.5 mL IM upper deltoid Every 3-5 years †<br />

Quadravalent meningococcal polysaccharide 0.5 mL SC* Every 3-5 years<br />

Haemophilus b conjugate 0.5 mL IM* None<br />

*Administered in the deltoid or lateral thigh region.<br />

† Contact the manufacturer for the latest recommendations prior to revaccination.<br />

EVIDENCE DEFINITIONS<br />

• Class I: Prospective randomized controlled trial.<br />

• Class II: Prospective clinical study or retrospective analysis of reliable data. Includes observational, cohort, prevalence, or case<br />

control studies.<br />

• Class III: Retrospective study. Includes database or registry reviews, large series of case reports, expert opinion.<br />

• Technology assessment: A technology study which does not lend itself to classification in the above-mentioned format.<br />

Devices are evaluated in terms of their accuracy, reliability, therapeutic potential, or cost effectiveness.<br />

LEVEL OF RECOMMENDATION DEFINITIONS<br />

• Level 1: Convincingly justifiable based on available scientific information alone. Usually based on Class I data or strong Class II<br />

evidence if randomized testing is inappropriate. Conversely, low quality or contradictory Class I data may be insufficient to<br />

support a Level I recommendation.<br />

• Level 2: Reasonably justifiable based on available scientific evidence and strongly supported by expert opinion. Usually<br />

supported by Class II data or a preponderance of Class III evidence.<br />

• Level 3: Supported by available data, but scientific evidence is lacking. Generally supported by Class III data. Useful for<br />

educational purposes and in guiding future clinical research.<br />

1

INTRODUCTION<br />

Blunt abdominal trauma commonly injures the spleen resulting in either irreparable parenchymal<br />

disruption (necessitating removal of the injured organ) or devascularization of varying degrees. Nonoperative<br />

management may avoid <strong>splenectomy</strong>, but can also result in functional asplenia if the<br />

devascularization is extensive or therapeutic embolization of a portion or all of the spleen is required.<br />

Elective <strong>splenectomy</strong> may be indicated for specific primary disease of the spleen. Loss of functional<br />

splenic tissue places such individuals at high risk for infection by encapsulated organisms such as<br />

Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae type b, and Neisseria meningitidis. Although the<br />

risk of fulminant septicemia or meningitis as a result of infection by such organisms appears to be less in<br />

the adult population (by virtue of prior exposure to these bacteria), overwhelming <strong>post</strong><strong>splenectomy</strong> sepsis<br />

(OPSS) remains a significant concern in the asplenic patient (1).<br />

The incidence of OPSS is estimated to occur in 0.05% to 2% of splenectomized patients (2). It may<br />

develop immediately or as late as 65 years <strong>post</strong><strong>splenectomy</strong> (2-4). Mortality is significant and reported to<br />

be as high as 50% (4,5). OPSS incidence reduction is dependent upon (2,5-7):<br />

1) Prophylactic education of the patient and physician as to its risk and prevention<br />

2) Rapid recognition of the asplenic individual when infection is suspected<br />

Reduced <strong>post</strong>-<strong>splenectomy</strong> levels of opsonins, splenic tuftsin, and immunoglobulin (IgM) (which promote<br />

phagocytosis of particulate matter and bacteria), hamper the body’s ability to clear encapsulated<br />

organisms (4,6,7). Vaccination, to impart immunity against such infections, is commonly performed<br />

despite the absence of Class I or Class II data to support its efficacy. As 50 to 90% of OPSS infections<br />

are secondary to Streptococcus pneumoniae infection, the polyvalent pneumococcal <strong>vaccine</strong> has been<br />

the most commonly administered <strong>post</strong><strong>splenectomy</strong> <strong>vaccine</strong>. In recent years, the meningococcal and<br />

Haemophilus influenzae type b <strong>vaccine</strong>s have also been advocated (2-17).<br />

Timing of <strong>vaccine</strong> administration following <strong>splenectomy</strong> has been the topic of a longstanding debate. Two<br />

major concerns include the patients’ immunogenicity in the perioperative period and the impaired immune<br />

function of the critically ill (2,13,16,17). The patient’s present state of health should be considered prior to<br />

the administration of <strong>post</strong><strong>splenectomy</strong> <strong>vaccine</strong>s. In patients with moderate to severe acute illness,<br />

vaccination should be delayed until the illness has resolved. This minimizes adverse effects of the<br />

<strong>vaccine</strong> which could be more severe in the presence of illness or could confuse the patient’s clinical<br />

picture (such as a <strong>post</strong>-<strong>vaccine</strong> fever) (16).<br />

All of the <strong>vaccine</strong>s cause adverse reactions which are generally self-limiting and resolve 24-72 hours after<br />

<strong>vaccine</strong> administration. The polyvalent pneumococcal <strong>vaccine</strong> causes a transient and self-limited fever<br />

(in 5% of vaccinated patients), as well as pain and redness at the site for 1-2 days. A hypersensitivity<br />

reaction can occur at the injection site of the Haemophilus influenzae type b <strong>vaccine</strong> along with<br />

occasional fever, aches, and malaise. Both meningococcal <strong>vaccine</strong>s can cause headaches, fatigue,<br />

malaise and injection site reactions.<br />

There are two meningococcal <strong>vaccine</strong>s currently on the market: the meningococcal polysaccharide<br />

<strong>vaccine</strong> (Menomune A/C/Y/W-135) and the meningococcal (groups A, C, Y, W-135) polysaccharide<br />

diphtheria toxoid conjugate (Menactra). Both products provide the same level of immunity against<br />

Neisseria meningitidis. Differences between the two products are as follows (29-32):<br />

1) Menactra is for intramuscular injection only, Menomune is administered subcutaneously.<br />

2) Menactra is a conjugated <strong>vaccine</strong> (adding the diphtheria toxoid).<br />

3) Menomune requires revaccination every 3-5 years. Long-term data with Menactra is not yet<br />

available. The manufacturer, Sanofi Pasteur, has data demonstrating adequate levels for up to 3-<br />

5 years (similar to Menomune). Due to on-going duration studies, it is recommended by the<br />

manufacturer that healthcare providers contact Sanofi-Pasteur prior to revaccination in order to<br />

obtain the most current information.<br />

4) Menactra is approved only for use in adolescents and adults between the ages of 11 and 55 (14-<br />

16,25-27) Menactra has applied for a license for use in children ages 2-10 years of age. There is<br />

currently no data on adults > 55 years of age.<br />

2 Approved 1/7/03<br />

Revised 10/17/06

LITERATURE REVIEW<br />

Two Class I studies have demonstrated that the polyvalent pneumococcal <strong>vaccine</strong> results in the highest<br />

antibody titers, for the most common serotypes, when administered 14 days <strong>post</strong><strong>splenectomy</strong> (16,17).<br />

These prospective, randomized trials evaluated the efficacy of the <strong>vaccine</strong> when administered at 1, 7, 14,<br />

and 28 days <strong>post</strong><strong>splenectomy</strong>. As these trials were designed to demonstrate the immunogenicity of the<br />

<strong>vaccine</strong>s and not the prevention of OPSS, they can only be used to advocate timing of vaccination.<br />

In 2004, Landgren et.al. published a prospective study on antibody response to repeated vaccination.<br />

This study included 28 (out of 311) <strong>post</strong>-trauma splenectomized patients. Their results showed that time<br />

between <strong>splenectomy</strong> and first pneumococcal <strong>vaccine</strong> was not associated with pre-vaccination, peak or<br />

follow-up antibody levels. 25 of the 28 trauma patients received their 1 st <strong>vaccine</strong> <strong>post</strong>-<strong>splenectomy</strong>. A<br />

major limitation of this study is that the time from <strong>splenectomy</strong> to first <strong>vaccine</strong> was only documented in<br />

24% of the cases, yet they claimed that timing had no effect (18). Similarly, Grimfors et.al. conducted a<br />

longitudinal study of 173 patients (33 trauma) for three years. Pneumococcal antibody responses<br />

declined to pre-treatment values at three years in all groups. They also found no correlation between the<br />

interval from <strong>splenectomy</strong> to vaccination and response to vaccination. The data to support this<br />

conclusion was not published (19).<br />

Schreiber et.al., published a study in rats in 1998 looking at timing of vaccination and subsequent ability<br />

to survive pneumococcal challenge. There was no difference in ability to survive a pneumococcal<br />

challenge between rats vaccinated on <strong>post</strong>-operative day 1, 7, or 42 (20). In another study, Werner et.al.<br />

looked at the effect of perioperative hypovolemic shock and response to vaccination and found no<br />

difference if splenectomized rats were vaccinated on <strong>post</strong>-operative day 1, 7, or 28. Both of these studies<br />

raise the question of whether delaying vaccination for 14 days as suggested in the Shatz et.al. studies is<br />

necessary (21). Further human studies are needed to address the timing of <strong>post</strong>-<strong>splenectomy</strong> <strong>vaccine</strong>s.<br />

Class II data supports the vaccination of asplenic patients based on studies of the spleen’s role in<br />

immune function and its ability to provide defense against encapsulated organisms (5). Current Center for<br />

Disease Control (CDC) recommendations for <strong>post</strong>-<strong>splenectomy</strong> vaccinations include the polyvalent<br />

pneumococcal (Pneumovax 23), the meningococcal (groups A, C, Y, W-135) polysaccharide diphtheria<br />

toxoid conjugate (Menactra, for patients ages 11-55) or the meningococcal polysaccharide (Menomune<br />

A/C/Y/W-135, ages 55), and the Haemophilus influenzae type b <strong>vaccine</strong>s (Hib TITER) (12-14,25-<br />

28). All three of these <strong>vaccine</strong>s may be administered simultaneously (15).<br />

Revaccination needs have been established by Class II studies of immune antibody levels and efficacy<br />

after initial vaccination (3). Patients receiving the pneumococcal <strong>vaccine</strong> should be revaccinated 5 years<br />

later (28). Patients who receive the meningococcal polysaccharide <strong>vaccine</strong> (Menomune A/C/Y/W-135)<br />

should be revaccinated every 3-5 years (12-14, 26, 27). Patients who receive the meningococcal (groups<br />

A, C, Y, W-135) polysaccharide diphtheria toxoid conjugate <strong>vaccine</strong> (Menactra) probably should be<br />

revaccinated every 3-5 years. However, long-term studies are currently on-going and the manufacturer,<br />

Sanofi-Pasteur, suggests contacting them (1-570-839-7187) for the latest recommendations prior to<br />

revaccination. The Haemophilus influenzae type b <strong>vaccine</strong> does not require revaccination (12-14).<br />

There is no Class I data identifying the appropriate timing for pre-<strong>splenectomy</strong> Haemophilus,<br />

Pneumococcal or Meningococcal vaccination for patients with nonfunctional or diseased spleens.<br />

Vaccination two weeks prior to surgery is commonly practiced, but this is supported only by Class III data<br />

(16, 17). Pre-<strong>splenectomy</strong> vaccination has been demonstrated to induce antibody formation in both<br />

adults and children (18). The types of antibody produced and time to antibody formation (generally 1 to 4<br />

weeks) does vary from patient to patient. (18-20). The antibody titer required to prevent either<br />

pneumococcal carriage or disease is unknown and has been extrapolated from data obtained from the<br />

literature on Haemophilus influenzae titers (21). In the elective <strong>splenectomy</strong> patient, therefore,<br />

vaccination as soon as splenic disease is diagnosed appears prudent to allow time for antibody<br />

production (13). The CDC has outlined recommendations for both initial vaccination in the pediatric<br />

population as well as booster (revaccination) requirements in patients with an anatomically present, but<br />

non-functional spleen (23).<br />

3 Approved 1/7/03<br />

Revised 10/17/06

The CDC recommends that asplenic travelers contact an international health clinic or the CDC<br />

(www.cdc.gov) to obtain information on disease risks within the intended country of travel. Asplenic<br />

travelers should be advised of the increased risk for Meningococcal meningitis and recommendation of<br />

the A and C <strong>vaccine</strong> for all asplenic individuals traveling to sub-Saharan Africa, India, and Nepal.<br />

REFERENCES<br />

1. King H, Schumacher HB. Splenic studies: I. Susceptibility to infection after <strong>splenectomy</strong> in infancy.<br />

Ann Surg 1952; 136(2):239-242.<br />

2. Shatz DV. Vaccination practices among North American trauma surgeons in <strong>splenectomy</strong> for trauma.<br />

J Trauma 2002; 53:950-956.<br />

3. Rutherford EJ, Livengood J, Higginbotham M, et.al. Efficacy and safety of pneumococcal<br />

revaccination after <strong>splenectomy</strong> for trauma. J Trauma 1995; 39:448-452.<br />

4. Dickerman JD. Traumatic asplenia in adults. Arch Surg 1981; 116:361-363.<br />

5. Davidson RN, Wall RA. Prevention and management of infections in patients without a spleen. Clin<br />

Microbial Infect 2001; 7:657-60.<br />

6. Waghorn DJ. Overwhelming infection in asplenic patients: current best practice preventative<br />

measures are not be followed. J Clin Pathology 2001; 54:214-218.<br />

7. Brigden ML, Pattulo AL. Prevention and management of overwhelming <strong>post</strong><strong>splenectomy</strong> infection –<br />

an update. Crit Care Med 1999; 27:836-42.<br />

8. Spickett GP, Bulliore J, Wallis J, et.al. Northern region asplenia register – analysis of first two years. J<br />

Clin Pathology 1999; 52:424-429.<br />

9. Williams DN, Bhavjot K. Post<strong>splenectomy</strong> care strategies to decrease the risk of infection. Postgrad<br />

Med 1996: 100: 195-8,201,205.<br />

10. Sumaraju V, Smith LG, Smith SM. Infectious complications in asplenic hosts. Infect Dis Clin N<br />

America 2001; 15:551-65.<br />

11. Styrt B. Infections associated with asplenia: risks, mechanisms, and prevention. Am J Med 1990;<br />

88:33N-42N.<br />

12. Prevention and control of meningococcal disease: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on<br />

Immunization Practices (AICP). MMWR 2000; 49(RR-07):1-3.<br />

13. Prevention and management of infections in patients without a spleen. Clin Micro and Infect 2001;<br />

12:657-680.<br />

14. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (AICP): Use of <strong>vaccine</strong>s<br />

and immune globulins in persons with altered immunocompetence. MMWR 1993; 42(RR-04):1-18.<br />

15. General recommendations on immunization: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on<br />

Immunization Practices (ACIP) and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP). MMWR<br />

2002; 51(RR-2):1-36.<br />

16. Shatz DV, Romero-Steiner S, Elie CM, et.al. Antibody responses in <strong>post</strong><strong>splenectomy</strong> trauma patients<br />

receiving the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide <strong>vaccine</strong> at 14 versus 28 days <strong>post</strong>operatively. J<br />

Trauma 2002; 53:1037-1042.<br />

17. Shatz DV, Schinsky MF, Pais LB, et.al. Antibody responses in <strong>post</strong><strong>splenectomy</strong> trauma patients<br />

receiving the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide <strong>vaccine</strong> at 1 versus 7 versus 14 days after<br />

<strong>splenectomy</strong>. J Trauma 1998; 44(6):760-766.<br />

18. Landgren O, Bjoerkholm M, Konradsen HB, et.al. A prospective study on antibody response to<br />

repeated vaccinations with pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide in splenectomized individuals with<br />

special reference to Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Intern Med 2004;255:644-673.<br />

19. Grimfors G, Soederqvist M, Holm G, et.al. A longitudinal study of class and subclass antibody<br />

response to pneumococcal vaccination in splenectomized individuals with special reference to<br />

Hodgkin’s disease. Eur J Haematol 1990;45:101-108.<br />

20. Schreiber MA, Pusateri AE, Veit BC, et.al. Timing of vaccination does not affect antibody response or<br />

survival after pneumococcal challenge in splenectomized rats. J Trauma 1998;45(4):692-697.<br />

21. Werner AM, Katner HP, Vogel R, et.al. Delayed vaccination dos not improve antibody responses in<br />

splenectomized rats experiencing hypovolemic shock. Am Surg 2001;67(9):834-838.<br />

22. Klinge J, Hammersen G, Scharf J, et.al. Overwhelming <strong>post</strong><strong>splenectomy</strong> infection with <strong>vaccine</strong>-type<br />

Streptococcus pneumoniae in a 12-year-old girl despite vaccination and antibiotic <strong>prophylaxis</strong>.<br />

Infection 1997; 25:368-371.<br />

4 Approved 1/7/03<br />

Revised 10/17/06

23. Wong WY, Overturf GD, Powars DR. Infection caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae in children with<br />

sickle cell disease: epidemiology, immunologic mechanisms, <strong>prophylaxis</strong>, and vaccination. Clin Infect<br />

Dis 192; 14:1124-1136.<br />

24. Siber GR, Gorham C, Martin P, et.al. Antibody response to pretreatment immunization and <strong>post</strong>treatment<br />

boosting with bacterial polysaccharide <strong>vaccine</strong>s in paitents with Hodgkin’s disease. Ann<br />

Intern Med 1986; 104:467-475.<br />

25. Hosea SW, Burch CG, Brown EJ, et.al. Impaired immune response of splenectomized patients to<br />

polyvalent pneumococcal <strong>vaccine</strong>. Lancet 1981; 1:804-807.<br />

26. Cimaz R, Mensi C, D’Angelo E, et.al. Safety and immunogenicity of a conjugate <strong>vaccine</strong> against<br />

Haemophilus influenzae type b in splenectomized and nonsplenectomized patients with Cooley<br />

anemia. J Infect Dis 2001; 183:1819-1821.<br />

27. Jockovich M, Menednhall NP, Sombeck MD, et.al. Long-term complications of laparotomy in<br />

Hodgkin’s disease. Ann Surg 1994; 219:615-621.<br />

28. CDC: Preventing pneumococcal disease among infants and young children. MMWR 2000; 49:1-38.<br />

29. Meningococcal (groups A, C, Y, and W-135) polysaccharide diphtheria toxoid conjugate <strong>vaccine</strong>:<br />

Menactra ® . Package Insert. Sanofi Pasteur. 2005 Dec: 1-10. www.menactra.com [Accessed 08-28-<br />

2006].<br />

30. Meningococcal polysaccharide <strong>vaccine</strong>. Drug Shortage Bulletin. ASHP. 2006 May 22. www.ashp.org<br />

[Accessed 08-28-2006].<br />

31. Meningococcal conjugate <strong>vaccine</strong> (MCV-4): AICP Recommendation. National Infection Prevention.<br />

CDC 2006. www.cdc.gov/nip/<strong>vaccine</strong>/mening/mcv4/mcv4_aicp.htm [Accessed 08-28-2006].<br />

32. Revisions to the general recommendations on immunizations. CDC 2006 Sept. www.cdc.gov<br />

[Accessed 08-28-2006]. PowerPoint presentation.<br />

5 Approved 1/7/03<br />

Revised 10/17/06

POSTSPLENECTOMY PATIENT INFORMATION SHEET<br />

Name:<br />

Splenectomy (splee-nek-tuh-mee) is the name of the operation that was done to remove your spleen.<br />

The spleen is a fist-sized organ located in the upper left side of your abdomen (belly). The spleen helps<br />

you fight infections, get rid of old or damaged red blood cells, and store blood for your body. Because of<br />

either disease or damage to your spleen, it had be removed. You can live without a spleen, but you may<br />

be at a higher risk for certain types of blood infection. To help you fight these infections in the future, you<br />

have been given the following immunizations (shots):<br />

□ Pneumococcal <strong>vaccine</strong>, polyvalent (Pneumovax 23)<br />

**Revaccinate every 6 years**<br />

□ Age > 55: Meningococcal polysaccharide <strong>vaccine</strong><br />

(Menomune A/C/Y/W-135) **Revaccinate every 3-5 years**<br />

□ Age 16-55: Meningococcal polysaccharide/diphtheria toxoid conjugate <strong>vaccine</strong><br />

(Menactra A/C/Y/W-135) **May need revaccination every 3-5 years**<br />

□ Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate <strong>vaccine</strong><br />

**No revaccination needed**<br />

Date:<br />

Date:<br />

Date:<br />

Date:<br />

It is important that you go and see a doctor IMMEDIATELY if you have any of the following symptoms:<br />

• Fever<br />

• Chills<br />

• Abdominal pain<br />

• Skin rash, swelling, redness, or infection<br />

• Diarrhea<br />

• Achy or weak feeling<br />

• Cough<br />

• Vomiting<br />

These are signs that you may have an infection. Without your spleen, a small or minor infection my<br />

become very serious and your doctor needs to examine you and possibly start antibiotics to help your<br />

body fight the infection. Always check with your doctor before any dental or invasive procedures, as you<br />

may need to take antibiotics before the procedure.<br />

The effect of the <strong>vaccine</strong>s in preventing infection varies from patient to patient and depends on the<br />

strength of your immune system when the <strong>vaccine</strong>s were given. You will need to be re-immunized (have<br />

the shots again) approximately every 5 years for the rest of your life. You should make sure that your<br />

doctor has a copy of this information sheet so that they can help remind you when it is time to be reimmunized.<br />

If you or your doctor have any questions about the above information, you should contact your<br />

surgeon:<br />

Surgeon’s Name:<br />

Surgeon’s Phone Number:<br />

6 Approved 1/7/03<br />

Revised 10/17/06