Program Notes for Virginia Symphony Orchestra Classics #8 - 24-26 ...

Program Notes for Virginia Symphony Orchestra Classics #8 - 24-26 ...

Program Notes for Virginia Symphony Orchestra Classics #8 - 24-26 ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

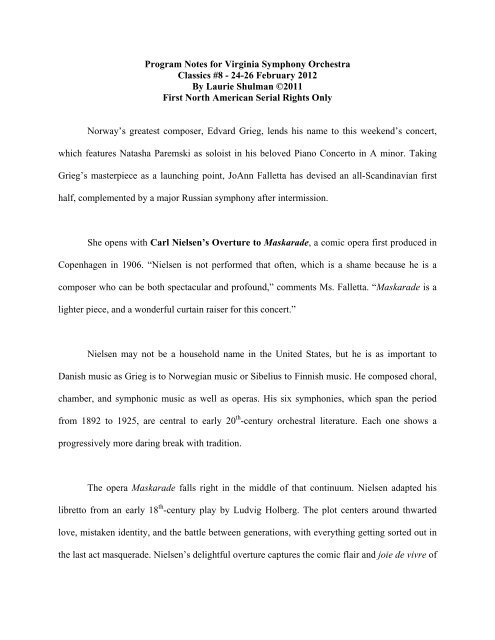

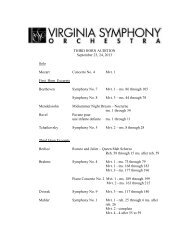

<strong>Program</strong> <strong>Notes</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Virginia</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

<strong>Classics</strong> <strong>#8</strong> - <strong>24</strong>-<strong>26</strong> February 2012<br />

By Laurie Shulman ©2011<br />

First North American Serial Rights Only<br />

Norway’s greatest composer, Edvard Grieg, lends his name to this weekend’s concert,<br />

which features Natasha Paremski as soloist in his beloved Piano Concerto in A minor. Taking<br />

Grieg’s masterpiece as a launching point, JoAnn Falletta has devised an all-Scandinavian first<br />

half, complemented by a major Russian symphony after intermission.<br />

She opens with Carl Nielsen’s Overture to Maskarade, a comic opera first produced in<br />

Copenhagen in 1906. “Nielsen is not per<strong>for</strong>med that often, which is a shame because he is a<br />

composer who can be both spectacular and profound,” comments Ms. Falletta. “Maskarade is a<br />

lighter piece, and a wonderful curtain raiser <strong>for</strong> this concert.”<br />

Nielsen may not be a household name in the United States, but he is as important to<br />

Danish music as Grieg is to Norwegian music or Sibelius to Finnish music. He composed choral,<br />

chamber, and symphonic music as well as operas. His six symphonies, which span the period<br />

from 1892 to 1925, are central to early 20 th -century orchestral literature. Each one shows a<br />

progressively more daring break with tradition.<br />

The opera Maskarade falls right in the middle of that continuum. Nielsen adapted his<br />

libretto from an early 18 th -century play by Ludvig Holberg. The plot centers around thwarted<br />

love, mistaken identity, and the battle between generations, with everything getting sorted out in<br />

the last act masquerade. Nielsen’s delightful overture captures the comic flair and joie de vivre of

the hero Henrik, who is a clever precursor to Beaumarchais’s Figaro.<br />

Few works in the classical repertoire boast the perennial popularity of Edvard Grieg’s<br />

Piano Concerto in A minor, Op.16. “This is the quintessential Scandinavian piano concerto, an<br />

absolute masterpiece,” declares Ms. Falletta. “Grieg’s music is beautifully crafted, with all the<br />

brilliance you want from a virtuoso piano concerto, yet it is still all about the music. Every<br />

pianist plays it differently: some lingering on every phrase, others pushing <strong>for</strong>ward. Music this<br />

rich in content allows <strong>for</strong> a wide variety of interpretations.”<br />

Grieg was born in Norway; however, like most 19 th -century Scandinavian composers, he<br />

pursued his <strong>for</strong>mal musical education in Germany, modeling his early works on those of<br />

Mendelssohn and Schumann. Later, he worked with Niels Gade in Denmark, and the premiere of<br />

his concerto in 1869 took place in Copenhagen. It was a pivotal work. After this concerto, he<br />

realized that his Norwegian heritage must be a central component of his music. A hint of that<br />

realization found its way into the finale. Grieg revised the concerto several times, continuing to<br />

tinker with the orchestration until 1907, the year of his death. He must have realized how<br />

important this work would be to his legacy. Few of his compositions with orchestra appears with<br />

any regularity in the concert hall.<br />

For Grieg was a miniaturist, ill at ease writing in large <strong>for</strong>ms. Generally speaking, his<br />

most successful compositions, such as the incidental music to Peer Gynt, consist of short dances<br />

and other concise movements. That is not the case in this splendid concerto, which has dramatic<br />

sweep and structural integrity along with a profusion of memorable melodies. Grieg’s muse was

definitely singing sweetly to him when he composed this work. From the piano’s dramatic<br />

opening salvo, through the delicate Chopinesque tracery of the slow movement, to the vitality of<br />

the finale, this concerto enchants and entertains. Grieg’s splendid coda to the last movement was<br />

influential on generations of composers from Tchaikovsky to Rachmaninoff.<br />

While his Piano Concerto falls squarely into the Austro-German romantic tradition, Grieg<br />

planted a strong personal imprint on its music, particularly in his Norwegian-tinged finale.<br />

Following intermission, Ms. Falletta and the VSO take on what is arguably Sergei<br />

Prokofiev’s greatest symphony: the <strong>Symphony</strong> No.5 in B-flat, Op.100. “Prokofiev could be<br />

dark, sardonic, and sarcastic in his music,” says Ms. Falletta. “All those qualities are present in<br />

this symphony, along with energy, humor, and a little bitterness. It’s a major challenge <strong>for</strong> the<br />

orchestra. For me, this symphony is about the power of life <strong>for</strong>ce, what is best in the human<br />

spirit. I feel its progression as a victory over adversity.”<br />

Prokofiev left Russia after Bolshevik Revolution and lived abroad <strong>for</strong> many years, first in<br />

the United States, then in Paris. He missed his homeland, however, and elected to return to the<br />

Soviet Union in the 1930s in spite of Stalin’s repressive regime.<br />

Like Shostakovich’s Leningrad <strong>Symphony</strong>, the Prokofiev Fifth was composed during the<br />

Second World War. Whereas the Shostakovich work is a salute to the suffering people of<br />

besieged Leningrad, however, Prokofiev’s symphony dates from a period of increasing<br />

optimism. The Allies had invaded Normandy and Soviet <strong>for</strong>ces were about to initiative powerful<br />

offensives against the Nazis from the eastern front. While not without its moments of conflict,

the Fifth <strong>Symphony</strong> is, as Ms. Falletta points out, an essentially affirming work. Certainly it<br />

reflects Prokofiev at the height of his career: healthy, productive, and writing splendidly. Its<br />

première in Moscow in January 1945 was the high point of his career in the USSR.<br />

Extended notes by Laurie Shulman about each of the compositions on this concert are available<br />

on the <strong>Virginia</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> web site, www.virginiasymphony.org.<br />

Overture to Maskarade<br />

Carl Nielsen<br />

Born 9 June, 1865 in Nørre-Lyndelse, Denmark<br />

Died 3 October, 1931 in Copenhagen, Denmark<br />

Denmark’s most celebrated musical figure, Carl Nielsen, only composed two operas, Saul<br />

and David (1898-1901) and Maskarade (1904-6). Outside Denmark, they are rarely per<strong>for</strong>med,<br />

but both operas have been recorded several times, and the sprightly overture to Maskarade is<br />

Nielsen’s most popular orchestral work apart from his six symphonies.<br />

He based the opera on an 18 th -century comedy by Ludwig Holberg (1684-1754), a<br />

Norwegian philosopher, playwright and historian known as the "Molière of the North." (He is the<br />

same author who inspired Edvard Grieg’s Holberg Suite.) The overture shares the lighthearted<br />

atmosphere of Nielsen’s comic opera, and the tunefulness of his many songs, which remain<br />

popular in Denmark. We may think of this lively curtain raiser as a Danish analogue to

Bernstein’s beloved Candide overture: barely five minutes of champagne-popping high spirits.<br />

Maskarade is a fun-loving sendup of 18 th -century convention.<br />

Nielsen scored the overture <strong>for</strong> three flutes (third doubling piccolo), two oboes, two<br />

clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, cymbals, bass<br />

drum, and strings.<br />

Piano Concerto in A minor, Op.16<br />

Edvard Grieg<br />

Born 15 June, 1843 in Bergen, Norway<br />

Died 4 September, 1907 in Bergen<br />

The route to Norwegian nationalism<br />

Norway’s celebrated musical son, Edvard Grieg, was sent to the German city of Leipzig<br />

when he was 15 to study at the Leipzig Conservatory. One of his piano teachers there was the<br />

great virtuoso Ignaz Moscheles. Though Grieg was not happy in Leipzig, he became immersed<br />

in the very lively musical culture that mid-ninteenth-century Germany offered. Be<strong>for</strong>e settling<br />

permanently in Norway, he also spent time in Copenhagen, where Niels Gade was the most<br />

influential composer. Beginning in the 1860s, however, Grieg began to take a strong interest in<br />

the folk music of his homeland. Thence<strong>for</strong>th his music took on an increasingly Norwegian slant.<br />

Today, Grieg is regarded as the most important composer that Norway has produced, and the<br />

father of Norwegian nationalist music.

In spite of his celebrity in his homeland, Grieg's international reputation rests primarily<br />

on the Piano Concerto, Op.16. As its opus number indicates, it is a relatively early work,<br />

completed when the composer was only 25; he lived into his 60s. The concerto is important <strong>for</strong><br />

a number of reasons. It was the largest orchestral work that Grieg composed, and the last piece<br />

that he wrote in the Austro-Germanic tradition be<strong>for</strong>e he discovered the wealth of Norwegian<br />

folk music that was to so strongly influence the balance of his career. As such the concerto is<br />

certainly a significant landmark.<br />

Even if that were not the case, however, the A minor Piano Concerto would be a marvel.<br />

Along with the Schumann Piano Concerto in the same key, with which it is frequently compared,<br />

Grieg's masterpiece holds court as the quintessential romantic concerto. His biographer John<br />

Horton calls it:<br />

. . . the most satisfying and successful of Grieg's attempts at composing in the<br />

larger traditional <strong>for</strong>ms, and the one that is generally agreed to be the most<br />

complete musical embodiment of Norwegian national Romanticism.<br />

Like Schumann's concerto (which Grieg acknowledged he had studied carefully be<strong>for</strong>e<br />

embarking on his own), Grieg's opens with a dramatic flourish <strong>for</strong> the soloist. He also follows<br />

Schumann's lead by dispensing with the double exposition familiar in the Mozart concertos.<br />

Thence<strong>for</strong>th, the two works differ. Where Schumann's first movement is monothematic, Grieg's<br />

has several distinct and contrasting theme groups, including a completely new melody that oboes<br />

and bassoons introduce in the coda. The pianist's cadenza dazzles with romantic/heroic<br />

passagework.<br />

From Schumann to Chopin

The second and third movements diverge more substantially from the Schumannesque<br />

model. Grieg's Adagio settles the dust kicked up by the blood and thunder of the first movement.<br />

Muted strings introduce the lush key of D-flat major, joined first by bassoon, then upper winds,<br />

be<strong>for</strong>e the soloist enters. D-flat is a distinctly Chopinesque key. Grieg's piano writing in the<br />

opening pages is umistakably imprinted with the delicate filigree of his Polish/French<br />

predecessor; so too are his harmonic travels on this extraordinary and passionate journey.<br />

Norwegian folk dance makes an appearance<br />

The finale gives us the most prophetic glimpse of Grieg's Norwegian voice, with which<br />

he was to speak so eloquently during the next decades. Characterized by strong rhythmic profile<br />

and a fiery, even pagan spirit, this movement is a halling, a Norwegian folk dance that Grieg<br />

used in other works (including his Lyric Pieces <strong>for</strong> piano, Op.47). A switch to a relaxed and<br />

lyrical section takes romantic liberties. Indeed, the tempo changes have a great deal to do with<br />

the dramatic tension that makes the finale so effective.<br />

He dedicated the concerto to Edmund Neupert, who played the Copenhagen premiere in<br />

autumn 1869. A pianist himself, Grieg undoubtedly sought opportunities <strong>for</strong> display. His ef<strong>for</strong>ts<br />

paid off handsomely, <strong>for</strong> the concerto was an immediate success and did much to establish<br />

Grieg's international reputation. Yet, never fully satisfied, he continued to revise its orchestration<br />

until the end of his life, refining the brass and woodwind parts. Most orchestras play the 1906-07<br />

version, his final revision.<br />

The score calls <strong>for</strong> woodwinds in pairs, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones,

timpani, solo piano and strings.<br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> No. 5 in B-flat, Op.100<br />

Sergei Prokofiev<br />

Born 23 April, 1891 in Sontzovka, Ukraine, Russia<br />

Died 5 March, 1953 in Moscow<br />

Happy you conducting American premiere my Fifth <strong>Symphony</strong>. Work very close to my<br />

heart. Sending sincere friendly greetings you and all members your magnificent orchestra.<br />

–Telegram, Prokofiev to Serge Koussevitzky, 6 November 1945<br />

‘Work very close to my heart.’ So consumed was Prokofiev by this symphony that he put<br />

off the celebrated film director Sergei Eisenstein, because he was so immersed in composing.<br />

“Now I’m busy with work on my Fifth <strong>Symphony</strong>, and my composition is flowing along in such<br />

a way that I can’t interrupt and switch over to [Eisenstein’s film] Ivan the Terrible. I’m sure<br />

you’ll understand me,” he wrote apologetically to Eisenstein on 31 July 1944. Prokofiev<br />

promised to devote himself to the film score the next month, when he would return to Moscow<br />

from his summer home, Ivanovo. By then, he had completed the symphony.<br />

Just a few months later, Prokofiev was on the podium when the Fifth <strong>Symphony</strong> was first<br />

per<strong>for</strong>med in Moscow on 13 January 1945. It proved to be his swan song as a conductor.<br />

Within four months, Europe and America were celebrating V-E day. Victory in the

Pacific Theatre followed in August. Barely three months after the end of World War II, during a<br />

Soviet radio broadcast of an all-Prokofiev program on 4 November, 1945. Prokofiev said:<br />

I wrote my Fifth <strong>Symphony</strong> in the summer of 1944 and I consider my work on<br />

this symphony very significant both because of the musical material put into it<br />

and because I returned to the symphonic <strong>for</strong>m after a 16-year interval. The Fifth<br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> completes, as it were, a long period of my works. I conceived it as a<br />

symphony of the greatness of the human spirit.<br />

Along with the Classical <strong>Symphony</strong> and Peter and the Wolf, the Fifth <strong>Symphony</strong> has proved one<br />

of Prokofiev's most popular and enduring works. It is his only mature symphony to have caught<br />

the popular imagination.<br />

Prokofiev is perhaps best known <strong>for</strong> the ballet scores (Romeo and Juliet, Cinderella).<br />

Pianists admire his magnificent contribution to the solo keyboard literature. But he was an<br />

experienced orchestral composer, producing seven symphonies that span virtually his entire<br />

creative life: the earliest, the Classical <strong>Symphony</strong>, Op.25 (1916-17) was preceded by two<br />

juvenile symphonies and a number of other orchestral compositions. Nos. 2, 3, and 4 all date<br />

from the mid- to late 1920s. Then ensued the 16-year hiatus mentioned in the radio quotation<br />

above.<br />

Soviet music and Prokofiev’s patriotism<br />

His final three symphonies are all considered Soviet works because they were written

after he had returned permanently to his homeland. During the Stalin years, Soviet music was<br />

under varying degrees of state supervision. For some composers, governmental restrictions<br />

proved stifling; others flourished artistically while suffering politically. Prokofiev's late works,<br />

those from 1946 to 1953, were uneven – but the quality of his music during the war years was<br />

superb.<br />

Despite the economic and circumstantial hardships of wartime, Prokofiev was especially<br />

productive from 1939 to 1945. He was at the peak of his composing powers, and he was still in<br />

good health. The Stalinist purges peaked in the late 1940s; the worst of that chilling period still<br />

lay in the future. Among the major works he completed during the war were the opera War and<br />

Peace, the ballet Cinderella, a string quartet, two piano sonatas, the flute sonata, five film scores<br />

and the Fifth <strong>Symphony</strong>. The latter represents the most epic side of his musical personality. It is<br />

the first overtly patriotic work not associated with theatre, film, voice, or some other<br />

programmatic medium. In the Fifth <strong>Symphony</strong>, Prokofiev's admiration <strong>for</strong> the Russian people<br />

speaks <strong>for</strong> itself through music alone.<br />

Influences: predecessors and contemporaries<br />

At 45 minutes, the Fifth is the largest scale of Prokofiev's seven symphonies. In it, the<br />

late romantic tradition of Borodin (rather than Tchaikovsky), and to some extent Bruckner,<br />

merges with that of his Soviet contemporary Shostakovich, whose influence is particularly<br />

audible in the emotional third movement. It is a highly melodic work, with a broad emotional<br />

spectrum that ranges from exuberant gamesmanship to heartfelt agony.

Despite the palpable "Russian-ness" of the music, Prokofiev eschews folk themes. He<br />

favors slower tempi, contributing to an aura of veiled tragedy that suffuses the symphony. The<br />

exceptions are the jaunty second movement scherzo, with its grotesque and fantastic elements,<br />

and the characteristic finale that begs to be choreographed. His bitter wit is most evident in these<br />

two movements, but the enduring message of this work is to be found in the intense drama of the<br />

first and third movements. He considered the Fifth <strong>Symphony</strong> his finest composition.<br />

The score calls <strong>for</strong> 2 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons,<br />

contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, timpani, bass drum, military<br />

drum, cymbals, harp, piano and strings.