Program Notes for Virginia Symphony Orchestra Classics #11 - - 13 ...

Program Notes for Virginia Symphony Orchestra Classics #11 - - 13 ...

Program Notes for Virginia Symphony Orchestra Classics #11 - - 13 ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

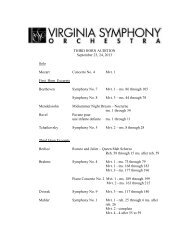

<strong>Program</strong> <strong>Notes</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Virginia</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

<strong>Classics</strong> <strong>#11</strong> - - <strong>13</strong>-15 April 2012<br />

By Laurie Shulman ©2011<br />

First North American Serial Rights Only<br />

“Water is life in Southeast <strong>Virginia</strong>,” declares JoAnn Falletta. “Our community is bound<br />

to the water. We see it everywhere; we walk by it, we drive around it and over it. Music about<br />

water seems completely appropriate to our programming.”<br />

In keeping with that view, she has chosen to open these season finale concerts with a<br />

piece of water music: Les Chants de la Mer [The Songs of the Sea] by Philippe Gaubert. A<br />

younger contemporary of Debussy and Ravel, Gaubert is best known <strong>for</strong> his flute works, but<br />

these three symphonic tableaux are a wonderful example of his orchestral writing. “The music is<br />

ravishing, beautiful,” confirms Ms. Falletta. “When I’ve conducted this piece be<strong>for</strong>e, the reaction<br />

has always been: ‘I loved that!’ Gaubert’s music has a little of Debussy in it; it’s certainly<br />

atmospheric, with beautiful tone painting.”<br />

Ms. Falletta points out that Gaubert composed Les Chants de la Mer in the 1920s, a time<br />

when poetry and music were tied closely together in France. His score includes three quotations<br />

from poetry about the sea, two by the French symbolist poet Paul Fort, and the third by Gaubert<br />

himself.<br />

“I think it’s wonderful that he wrote one of the poems accompanying the score,” says Ms.<br />

Falletta. “His involvement in the imagery gives us a more personal experience with his music.”<br />

Each of Gaubert’s three movements presents a different perspective of the sea. First, he

explores its variety of colors as the surface reflects sun and the shifting clouds above. Then he<br />

moves to a cliff overlooking the water. Unspecified persons – children a pair of lovers, perhaps<br />

– are dancing an imaginary round dance, scampering about amid the music of the cool breeze<br />

and the scent of sea air. They drink in the sight of the ocean as they trample May wildflowers<br />

underfoot, oblivious to everything but the exhilaration of the moment. Finally, Gaubert<br />

‘composes’ the sea at dusk, as a fiery sunset slips over the horizon, hinting at the mystery of the<br />

ocean at night.<br />

The centerpiece of our program is “Tchaikovsky’s Hidden Jewel,” the rarely heard piano<br />

concerto that follows intermission. In fact there is more than one such gem on the program. Igor<br />

Stravinsky is our link between France and Russia – and the bridge to Tchaikovsky. He based his<br />

1928 ballet, Le baiser de la fée [The Fairy’s Kiss] on themes from little known works by<br />

Tchaikovsky, songs and piano pieces that Tchaikovsky had never orchestrated. Stravinsky reinterpreted<br />

these miniatures in his own unique musical language. This neoclassic masterpiece is<br />

an homage to one of Stravinsky’s most revered predecessors -- and to a beloved author. The<br />

ballet scenario derives from a tale by Denmark’s Hans Christian Andersen. We hear the<br />

Divertimento from The Fairy’s Kiss, essentially a four-movement suite of highlights from the<br />

complete ballet.<br />

“This Divertimento is one of my ‘pet’ pieces,” says Ms. Falletta. “Stravinsky was paying<br />

tribute to Tchaikovsky, but also poking fun at him in a very loving way. He is very sly, the way<br />

he adapts all the standard Tchaikovsky ballet techniques, twisting them around so that they<br />

sound almost slapstick. When he finished the score, he claimed that he didn’t know where

Tchaikovsky ended and Stravinsky started. The Fairy’s Kiss must have been great fun <strong>for</strong> him.”<br />

Following intermission, pianist William Wolfram joins the orchestra <strong>for</strong> Tchaikovsky’s<br />

Piano Concerto No.2 in G major, Op.44. This work has been all but eclipsed by the immensely<br />

popular First Piano Concerto, which makes these per<strong>for</strong>mances all the more special.<br />

Tchaikovsky's contemporaries regarded him as the most westernized of Russian<br />

composers, and indeed, like Glinka be<strong>for</strong>e him, he was well traveled and widely conversant with<br />

contemporary music in Europe. He composed this spectacularly difficult concerto at a crucial<br />

time in his turbulent life, yet the music is not so overtly emotional as other works written about<br />

the same time. It does have plenty of drama and technical fireworks, however, particularly in the<br />

showy first movement.<br />

All three movements are musical treasure chests, the hidden jewels of our concert title,<br />

but the slow movement is especially wonderful. It features prominent roles <strong>for</strong> Concertmaster<br />

Vahn Armstrong and Principal Cellist Michael Daniels as well as Mr. Wolfram, which makes it<br />

almost a triple concerto. The orchestra, rather than the piano, presents the principal thematic<br />

material. Tchaikovsky’s emphasis on three soloists gives the Andante non troppo psychological<br />

weight. “It’s like a big piano trio in the midst of the slow movement: extended chamber music,”<br />

says Ms. Falletta. “That’s the heart of the concerto <strong>for</strong> me.”

Les Chants de la Mer: Trois tableaux symphoniques [Songs of the Sea: Three Symphonic<br />

Tableaux]<br />

Philippe Gaubert<br />

Born 5 July 1879 in Cahors, Lot, France<br />

Died 8 July 1941 in Paris<br />

Approximate duration 17 minutes<br />

The flutist, conductor, and composer Philippe Gaubert was the most distinguished<br />

protégé of the great virtuoso Paul Taffanel, widely regarded as the father of modern French flute<br />

playing. (Taffanel and Gaubert collaborated on a flute method published in 1923 that is still in<br />

use.) Like his teacher, Gaubert eventually became conductor at the Paris Opéra. He composed<br />

works <strong>for</strong> stage and orchestra as well as songs and chamber music.<br />

Along with many of his French contemporaries, Gaubert was overshadowed by the<br />

towering figures who dominated French music in the early decades of the 20 th century: Claude<br />

Debussy (1862-1918) and Maurice Ravel (1875-1937). Both their influences are perceptible in<br />

Les Chants de la Mer, first per<strong>for</strong>med in 1929. The obvious ‘cousin’ to these three symphonic<br />

tableaux is Debussy’s La Mer (1905), whose subtitle was “three symphonic sketches.”<br />

Gaubert’s is no copycat work, however, and there are abundant examples of ‘water music’ in the<br />

orchestral literature prior to Debussy and after Gaubert. The sea has inspired evocative<br />

symphonic canvasses from many other composers, notably Felix Mendelssohn (Hebrides<br />

Overture), Richard Wagner (The Flying Dutchman), Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (Scheherazade),<br />

Arnold Bax (Tintagel), Ralph Vaughan Williams (A Sea <strong>Symphony</strong>), and Benjamin Britten (Four<br />

Sea Pictures from Peter Grimes).<br />

Gaubert’s approach is unusual because his score includes three poetic epigraphs that lend<br />

their titles to the movements. The first two are from Les Ballades de la Mer [Sea Ballads] by<br />

Paul Fort (1872-1960), a poet and dramatic director who was important in French symbolist<br />

theatre at the turn of the 20 th century. His prose ballades have the structure and rhythm of poetry.<br />

Gaubert was drawn to Fort’s work. For the third movement, Gaubert appended his own poem,<br />

similar in style to Fort’s writing.<br />

Gaubert favors triple meter throughout Les Chants de la mer, subtly evoking the rock and<br />

swell of the waves. The music is unmistakably French, with strong overtones of impressionism.<br />

Gaubert changes keys frequently in modulations reminiscent of Fauré. His extensive use of<br />

whole tone scales, however, is closer to the style of Debussy and Ravel. He uses the orchestra<br />

beautifully, with cameo solos sprinkled generously throughout: cello in the first movement, the<br />

first stand violins in the second, and a series of solos <strong>for</strong> tumpet, horn, violin, and flute in the<br />

finale. Harp and percussion add color and sparkle to Gaubert’s superb orchestation.

Chants et parfums, mer colorée [Songs and perfumes, the multi-colored sea] celebrates<br />

the joy of being alive and the author’s passion <strong>for</strong> the sensuous experience of light and wind<br />

upon the sea. His pace is leisurely, just as the majestic surface of the ocean will not be rushed.<br />

The music unfolds with hypnotic power.<br />

La ronde sur la falaise [The round dance on the cliff] is a scherzo. Lighthearted and<br />

playful, Gaubert’s dancers scamper about, exulting in their view of the sea from the high<br />

promontory. The <strong>for</strong>m is ternary, with a central trio section switching to 2/4 meter. It is the only<br />

instance of duple meter in the score.<br />

Bold horn calls open Là-bas, très loin, sur la mer [Over there, very far away, on the sea].<br />

Gaubert paints a picture of sunset on the western horizon over the infinite expanse of the ocean.<br />

A dusky mixture of red and blue heralds the mystery of the night, enveloping all. He passes a<br />

single theme among four soloists, at once unifying the music and exploring the endless variety<br />

of the sea.<br />

The score calls <strong>for</strong> 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2<br />

bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, cymbals, bass drum,<br />

triangle, Basque tambourine, harp, and strings.<br />

THE POEMS IN GAUBERT’S SCORE<br />

Philippe Gaubert’s score to Les Chants de la Mer includes a page with the following excerpts<br />

from poems by Paul Fort and Gaubert.<br />

Chants et parfums, mer colorée<br />

Douceur d’aimer! Douceur de vivre! Chants et parfums, mer colorée des plus touchantes<br />

harmonies de l’air, nuée et nue mirées, mer chantante, mer parfumée, langueur marine, que je<br />

vous aime!<br />

La mer est verte, la mer est grise, elle est d’azure, elle est d’argent, et de dentelles que l’air<br />

brouille en mélangeant leurs ton changeants . . . Mon Dieu que j’aime la lumière! . . . J’ai tout<br />

le prisme dans les yeux, le sable d’or sous mes cils bleus, entre mes cils palpite et chante la mer<br />

aux voiles frémissantes, la mer charmante . . . Douceur d’aimer! Douceur de vivre! Chants et<br />

parfums, mer colorée!<br />

– Paul Fort, Les Ballades de la Mer<br />

Sweetness of loving! Sweetness of living! Melodies and perfumes, sea colored by the most<br />

affecting harmonies of the air, thick clouds and skies in sight, singing sea, perfumed sea, marine<br />

languidness, how I love you!<br />

The sea is green, the sea is grey, it is azure, it is silver, and of lacework that the breeze whips up<br />

while jumbling together their changing shades . . . My God how I love the light! I have the<br />

complete prism in my eyes, the golden sand under my blue eyelashes, between my lashes the sea

eats and sings to rustling sails, bewitching sea. . . . Sweetness of loving! Sweetness of living!<br />

Melodies and perfumes, colored sea.<br />

La ronde sur la falaise (scherzo)<br />

Nous foulerons sur la falaise, à la falaise, à la musique du vent frais, les roses fleurettes de Mai<br />

jusqu’à nous en trouver bien aise.<br />

Dansons la ronde sur la falaise!<br />

The round dance on the cliff<br />

– Paul Fort, Les Ballades de la Mer<br />

We will trample on the cliff, to the cliff, to the music of the cool air, trampling on the little May<br />

flowers until we find com<strong>for</strong>t. Let us dance the round dance on the cliff!<br />

Là-bas, très loin, sur la mer<br />

Au soir . . . . soleil rouge . . . le crépuscule est lourd au matelot qui peine, tristes les yeux<br />

nostalgiques. . . la mer se mélange aux tons bleus du crépuscule. . . tristesse environnante des<br />

choses . . . Le souvenir du pays monte en bouffées vers le matelot redressé qui tend, joyeux, en<br />

un élan d’espoir, les bras, là-bas ver le foyer . . . mais la route est longue et la tristesse le<br />

reprend. A l’horizon le soleil saigne, agonisant. . . La mer s’étend infinie . . . . la nuit<br />

mystérieuses descend, enveloppe tout.<br />

– Philippe Gaubert<br />

In the evening . . . crimson sun. . . dusk weighs heavily on the struggling sailor, sad are [his]<br />

nostalgic eyes . . . the sea loses itself in the blue hues of the dusk . . . encompassing sadness of<br />

things . . The memory of the land rises in puffs, toward the upright sailor who, joyous, holds his<br />

arms out, in a surge of hope, toward home over there . . . but the ship’s path is long and sadness<br />

retakes him. On the horizon, the sun bleeds, agonizing . . . the sea extends infinitely . . . the<br />

mysterious night falls, enveloping all.

-7-

Divertimento from The Fairy's Kiss<br />

Igor Stravinsky<br />

Born 17 June, 1882 in Oranienbaum, Russia<br />

Died 6 April, 1971 in New York City<br />

Approximate duration 22 minutes<br />

A half century of ballets<br />

For all the astonishing diversity of his genius, Stravinsky's most lasting contribution is in<br />

the realm of ballet. Yet, in the popular imagination, his substantial reputation continues to rest<br />

primarily on three early masterpieces: L'oiseau de feu (The Firebird, 1910), Pétrouchka (1911),<br />

and Le sacre du printemps (The Rite of Spring, 19<strong>13</strong>). Stravinsky lived more than half a century<br />

after the last of that stunning trio of ballets, continuing to compose until the mid-1960s. Many of<br />

his subsequent scores were also written <strong>for</strong> the ballet stage, and have remained in the repertoire<br />

with double lives as both dance and concert scores.<br />

Stravinsky’s salute to the past<br />

Two of these, Pulcinella (1920) and Le baiser de la fée (The Fairy's Kiss, 1928) hold a<br />

special place in Stravinsky's oeuvre because they are based in large part upon the works of<br />

earlier composers. Clearly a musician of Stravinsky's ingenuity and originality had no need to<br />

rely on others <strong>for</strong> his musical material, and indeed in both cases he was paying tribute to one of<br />

his predecessors. The story behind The Fairy's Kiss is particularly engaging.<br />

-8-

Late in 1927, Stravinsky was approached by the dancer Ida Rubinstein, who was starting<br />

a new ballet company. For its inauguration, she wished to commission a new work inspired by<br />

Tchaikovsky's music. Stravinsky was a great admirer of Tchaikovsky, and was strongly drawn<br />

to the project because of the timing: 1928 was the 35th anniversary of Tchaikovsky's death.<br />

Ironically, Stravinsky's mentor and colleague Serge Diaghilev was greatly offended that<br />

Stravinsky accepted a commission from someone else. What he perceived as an insult stung<br />

deeper because Ida Rubinstein was a <strong>for</strong>mer dancer with Diaghilev's incomparable troupe, the<br />

Ballets russes. (In fact, of Stravinsky's stage works, only three -- L'histoire du soldat (1918),<br />

Apollon musagète (1928) and The Fairy's Kiss -- came to fruition independent of Diaghilev.)<br />

Nevertheless, the project went <strong>for</strong>ward.<br />

Stravinsky's musical approach was to take<br />

fragments of melodies, or entire themes, from Tchaikovsky's music, endowing it with freshness<br />

through piquant orchestration and the addition of some original material. He selected all the<br />

excerpts from Tchaikovsky's lesser-known piano works, much of it frankly salon music:<br />

Humoresques, Nocturnes, Valses russes, Scherzos, an Evening Reverie, an Album Leaf, and<br />

several songs, among others. None of his choices was orchestral. Stravinsky knew this music<br />

well, since childhood, and Tchaikovsky was his favorite Russian composer. (In Expositions and<br />

Developments, one of his collaborative books with Robert Craft, the composer detailed his<br />

borrowings and adaptations.)<br />

Chamber sonorities from the ballet’s pit orchestra<br />

The challenge he faced was to sustain the dramatic interest of a long ballet with the<br />

-9-

vehicle of the lighter raw material of salon miniatures. He kept the texture light, despite tripling<br />

the woodwinds in the orchestration, by using smaller groups of instruments in combinations<br />

rather than drawing upon the massive sound of full orchestra. Consequently, the entire score has<br />

a more chamber-like feel to it. Also, the borrowings are carefully intermingled with Stravinsky's<br />

own original writing. His acerbic style cuts through any danger of sentimentality in his treatment<br />

of Tchaikovsky's music; the innate theatricality and simple appeal of the tale delivers the rest.<br />

In the composer’s words: adapting a beloved fairy tale<br />

In his 1936 autobiography, Chroniques de ma vie, Stravinsky discusses Hans Christian<br />

Andersen's tale, "The Ice Maiden", and its trans<strong>for</strong>mation into a ballet.<br />

I chose ["The Ice Maiden"] as my theme, and worked out the story on the<br />

following lines. A fairy imprints her magic kiss on a child at birth and parts it<br />

from its mother. Twenty years later, when the youth has attained the very zenith<br />

of his good <strong>for</strong>tune, she repeats the fatal kiss and carries him off to live in<br />

supreme happiness with her <strong>for</strong>ever afterward.<br />

As my object was to<br />

commemorate the work of Tchaikovsky, this subject seemed to me to be<br />

particularly appropriate as an allegory, the muse having similarly branded<br />

Tchaikovsky with her fatal kiss, and the magic imprint has made itself felt in all<br />

the musical creations of this great artist.<br />

The music is divided into five principal sections. Two lullabies frame the ballet: in the<br />

first, "Lullaby in the Storm," the child is separated from its mother. The closing section is its<br />

-10-

eprise, retitled and reworked as "Lullaby of the Land Beyond Time and Place," with a peculiarly<br />

tranquil aura of wide open, heavenly space. In between, Stravinsky provides musical interest by<br />

contrast: notably a boisterous village fête, in which the music vividly illustrates country peasant<br />

dancing. In snatches here, we can sense the echo of certain Russian operas, and also perhaps the<br />

spirit of Petrushka.<br />

Stravinsky's score calls <strong>for</strong> two flutes, piccolo, two oboes, English horn, three clarinets<br />

(third doubling bass clarinet), two bassoons, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba,<br />

timpani, bass drum, harp, and string quintet.<br />

Piano Concerto No. 2 in G major, Op.44<br />

Pyotr Ilich Tchaikovsky<br />

Born 7 May, 1840 in Votkinsk, Viatka District, Russia<br />

Died 6 November, 1893 in St. Petersburg, Russia<br />

Approximate duration 37 minutes<br />

How Many Concertos<br />

Tchaikovsky's Piano Concerto No.2 Is there a misprint He<br />

just wrote one, right Wrong. Tchaikovsky actually composed<br />

three piano concerti. The popularity of the First has virtually<br />

eclipsed the other two.<br />

Tchaikovsky wrote his First Concerto in 1875 <strong>for</strong> the pianist<br />

Nikolai Rubinstein, but withdrew his dedication when Rubinstein<br />

criticized the piece. Only after the German pianist Hans von<br />

Bülow enjoyed great success with the First Concerto did<br />

Rubinstein amend his opinion. He became a great champion of the<br />

B-flat minor work.<br />

Mollified, Tchaikovsky wished to compose another concerto<br />

<strong>for</strong> his friend. The years since the earlier concerto had been<br />

tumultuous in his personal life, but rewarding professionally.<br />

When he began sketching the Second Concerto in 1879, he had no<br />

outstanding commissions, no pressing deadlines. He simply felt<br />

the need to compose. His letters indicate boredom and a desire<br />

to stay busy. Perhaps that accounts <strong>for</strong> the Second Concerto's<br />

enormous length.<br />

Cutting and Pasting<br />

-11-

Tchaikovsky reported to his patroness, Mme. von Meck, that<br />

Nikolai Rubinstein thought the piano part overly episodic, and<br />

that it didn't stand out from the orchestra enough.<br />

Un<strong>for</strong>tunately Rubinstein died be<strong>for</strong>e the intended première.<br />

Tchaikovsky's student Sergei Ivanovich Taneyev learned the piece,<br />

and Anton Rubinstein (Nikolai's brother) conducted the Moscow<br />

premiere in May 1882. The verdict was "too long." Some six<br />

years later, Tchaikovsky excised lengthy passages from the first<br />

two movements. In subsequent per<strong>for</strong>mances, the conductor<br />

Alexander Ziloti made other extensive cuts; that version was<br />

published four years after Tchaikovsky's death. Mr. Markovich<br />

plays the original, full-length version.<br />

Advances in Tchaikovsky’s Piano Writing<br />

There are striking differences between the First and Second<br />

Concertos. Where the first has an overabundance of melodies, the<br />

second has few big themes. It is more music of gesture and<br />

motive. Yet if the characteristic heart-on-the-sleeve tune is<br />

not in evidence, Tchaikovsky's control of the orchestra and<br />

skillful handling of symphonic material reflect an impressive<br />

advance over the First Concerto. Further, the Second Concerto<br />

shows more signs than the First of having been written<br />

specifically <strong>for</strong> keyboard. The opening movement in particular is<br />

a virtuoso showcase. Listeners who enjoy the theatre of a<br />

vigorous, physical per<strong>for</strong>mance as much as the music itself will<br />

be on the edge of their seats. This is interactive concertowriting,<br />

whereby the soloist's sheer muscular ef<strong>for</strong>t seems to<br />

drain us.<br />

Chamber Music Interpolated into a Concerto<br />

The slow movement is unusual in that the orchestra presents<br />

all the themes, rather than the soloist. Also, it features<br />

obbligato parts <strong>for</strong> the concertmaster and principal cellist. The<br />

solo strings endow the movement with the operatic weight it needs<br />

<strong>for</strong> emotional integrity and focus. The result is quite<br />

transporting, as lyrical and intimate as anything Tchaikovsky<br />

wrote.<br />

Tchaikovsky's finale is as compressed as the first movement<br />

is expansive. The structure combines sonata and rondo.<br />

Spiritually, this Allegro con fuoco is related to the Cossack<br />

dance that concludes the First Concerto. Here, however, all the<br />

melodies are original. It is all over rather quickly. In<br />

comparison to the leisurely expanse of the first two movements,<br />

it thus runs the risk of appearing disproportionately brief.<br />

Nevertheless this finale has punch, bravura, and undeniable<br />

sparkle.<br />

-12-

Tchaikovsky scored the Second Concerto <strong>for</strong> woodwinds in<br />

pairs, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, solo piano and strings.<br />

-<strong>13</strong>-