Developing valid, reliable and fair exams.pdf - Pearson VUE

Developing valid, reliable and fair exams.pdf - Pearson VUE

Developing valid, reliable and fair exams.pdf - Pearson VUE

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Developing</strong> <strong>valid</strong>,<br />

<strong>reliable</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>fair</strong> <strong>exams</strong><br />

3<br />

01010100101010101001011<br />

11001010010101000101010<br />

10011100101001101001000<br />

10100100100100010100010<br />

10001010101010101011010<br />

10101011001010101010101<br />

00110010101001001000101<br />

01010101011010011000101<br />

Some high-stakes examinations are created to distinguish<br />

c<strong>and</strong>idates who demonstrate the required knowledge,<br />

skills <strong>and</strong> abilities from c<strong>and</strong>idates who do not. Other<br />

examinations place test-takers along a continuum so<br />

that <strong>valid</strong> comparisons can be made. Regardless of<br />

whether the goal of the examination is to make a pass/<br />

fail decision or to provide a ranking of test-takers, the<br />

examination must be <strong>valid</strong>, <strong>reliable</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>fair</strong> (1) .<br />

Validity, reliability <strong>and</strong> <strong>fair</strong>ness<br />

Validity<br />

The St<strong>and</strong>ards for Educational <strong>and</strong> Psychological Testing (SEPT)<br />

(1) describe <strong>valid</strong>ity as “the most fundamental consideration in<br />

developing <strong>and</strong> evaluating tests”. Simply put, <strong>valid</strong>ity is concerned<br />

with answering the following two questions:<br />

1. Does the test measure what it is intended to measure<br />

2. Are the interpretations drawn from the test scores appropriate<br />

<strong>and</strong> justifiable<br />

Evaluating the processes used to develop test items can provide<br />

evidence for <strong>valid</strong>ity, as can an analysis of the relationships among<br />

test items <strong>and</strong> whether these relationships support the intended<br />

test construct. The <strong>valid</strong>ity of a test can also be assessed by<br />

comparing the test scores to other relevant external variables. For<br />

example, test scores from a university admissions test could be<br />

compared to measures of performance at the university to obtain<br />

<strong>valid</strong>ity-related information.<br />

Reliability<br />

Reliability refers to the consistency of the measure <strong>and</strong> the degree<br />

to which a test is free of r<strong>and</strong>om error. The usefulness of testing<br />

presupposes that there is at least some stability in the test-taker’s<br />

knowledge level (1). However, some degree of test score variance<br />

is inevitable. Test-takers’ performance can be affected by many<br />

factors, such as anxiety or how they are feeling on the day of the<br />

test. While these factors are outside of their control, test sponsors<br />

<strong>and</strong> providers have a duty to st<strong>and</strong>ardize the factors contributing to<br />

irrelevant test score variance that are within their control, such as<br />

the testing environment <strong>and</strong> the test itself.<br />

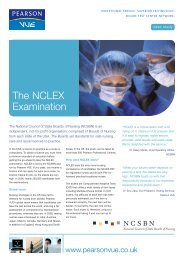

Anything about the test or testing conditions that causes a testtaker<br />

to respond based on something other than knowledge of<br />

the correct response is an error. There are two types of error<br />

which must be understood. Systematic error reflects differences<br />

amongst test-takers that are irrelevant to the purposes of testing.<br />

For example, quantitative reasoning items that require high levels<br />

of verbal ability to answer would introduce a systematic source<br />

of variance into the test scores (verbal ability) that is irrelevant to<br />

the goal of testing (assessment of quantitative reasoning). R<strong>and</strong>om<br />

error is caused by temporary, chance influences on the test result,<br />

such as a test-taker misreading an item or a grading error on an<br />

essay item. The relationship between score variance, <strong>valid</strong>ity <strong>and</strong><br />

reliability is illustrated in the following diagram.<br />

Real Differences<br />

Among Individuals<br />

Validity<br />

Systematic Error<br />

Total test score variance<br />

Reliability<br />

R<strong>and</strong>om Error

<strong>Developing</strong> <strong>valid</strong>, <strong>reliable</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>fair</strong> <strong>exams</strong><br />

Fairness<br />

As the (SEPT) (1) point out, “the term <strong>fair</strong>ness is used in many<br />

different ways <strong>and</strong> has no single technical meaning.” The St<strong>and</strong>ards<br />

outline four ways in which the term can be used in relation to<br />

testing: A) the absence of bias, B) <strong>fair</strong> treatment with regard to<br />

test procedures, test scoring, <strong>and</strong> the use of scores, C) equality of<br />

outcomes in testing so that test-takers of equivalent ability should<br />

have equivalent test results regardless of group membership (for<br />

example, race or ethnicity), <strong>and</strong> D) equitable opportunities to learn<br />

the material covered by the test.<br />

The incorporation of item bias <strong>and</strong> sensitivity reviews during<br />

the item development process can be supplemented by the use<br />

of statistical measures to identify items which have a different<br />

probability of a correct response for different test-taker subgroups.<br />

A psychometric analysis of differential item functioning (DIF)<br />

identifies items that perform differently across subgroups of testtakers<br />

(e.g. gender, ethnicity, sociodemographic status, age) while<br />

controlling for the ability of the test-takers. That is, the probability<br />

of a correct response differs dependent on group membership<br />

even for test-takers with the same ability. Items flagged for DIF<br />

are subject to greater content scrutiny to investigate potential bias<br />

<strong>and</strong> justify their continued inclusion in the item bank. It should be<br />

stressed that differential item functioning does not automatically<br />

equate to bias – there may be legitimate reasons as to why an item<br />

performs differently for different subgroups.<br />

St<strong>and</strong>ard setting, test assembly <strong>and</strong> equating are important to<br />

establishing <strong>fair</strong>ness in test procedures <strong>and</strong> test scoring. These<br />

concepts are discussed in the subsequent sections.<br />

St<strong>and</strong>ard setting<br />

For examinations that require a pass/fail decision, a passing<br />

st<strong>and</strong>ard must be established. There are three general methods for<br />

setting a pass mark:<br />

1. Holistic – An arbitrary fixed percentage pass mark (for example,<br />

60%)<br />

2. Norm-referenced – A fixed pass rate (for example, the top 60%<br />

of test-takers)<br />

3. Criterion-referenced – Setting the pass mark at an absolute<br />

st<strong>and</strong>ard that denotes the required level of competence<br />

A holistic pass mark is the least appropriate. Unless there is a<br />

rationale for using a norm-referenced st<strong>and</strong>ard (for example, a<br />

limited number of placements available for a training program),<br />

criterion-referenced st<strong>and</strong>ards are preferred. For high-stakes<br />

examinations, such as licensure or certification tests, criterionreferenced<br />

st<strong>and</strong>ard setting is widely recognized as the method of<br />

choice. <strong>Pearson</strong> <strong>VUE</strong> psychometricians employ criterion-referenced<br />

st<strong>and</strong>ard-setting procedures that have been developed based upon<br />

universally-accepted psychometric practices.<br />

Test assembly<br />

<strong>Pearson</strong> <strong>VUE</strong> has extensive experience with test assembly for<br />

computer-based examinations. Our content developers <strong>and</strong><br />

psychometricians work with clients to choose an appropriate<br />

test administration model, including fixed-form, linear-on-the-fly<br />

(LOFT) or adaptive test design. In the fixed-form design, a specified<br />

number of content- <strong>and</strong> statistically-equivalent exam versions<br />

(forms) are assembled. In a LOFT test design, items are r<strong>and</strong>omly<br />

selected from the item pool for examination inclusion to fulfil a<br />

prescribed series of content <strong>and</strong> statistical rules. In adaptive testing,<br />

items are selected to test an individual test-taker based upon an<br />

underst<strong>and</strong>ing of the test-taker’s ability level as identified through<br />

Glossary of Terms<br />

Classical test theory (CTT)<br />

An exam development <strong>and</strong> evaluation<br />

framework derived from the premise that<br />

any test score can be expressed as the sum<br />

of two independent components – 1) the<br />

test-taker’s true st<strong>and</strong>ing on the construct<br />

of interest, <strong>and</strong> 2) r<strong>and</strong>om error. Test<br />

items are characterized in terms of the<br />

proportion of a specified population able<br />

to correctly answer the item (item difficulty<br />

or p value)<br />

<strong>and</strong> the point-biserial correlation between<br />

item score <strong>and</strong> test score (item-test<br />

correlation). Test-takers are scored using<br />

some function of the number of items<br />

answered correctly.<br />

Computerized adaptive testing (CAT)<br />

A computer-based test in which successive<br />

items are selected from a pool of items<br />

based on the test-taker’s performance on<br />

previous items. Based in<br />

item response theory (IRT), this type of<br />

testing is intended to select items that are<br />

of appropriate difficulty for the test-taker.<br />

Good performance by the test-taker<br />

leads to more difficult questions; poor<br />

performance leads to easier questions.<br />

Adaptive tests can be fixed or variable in<br />

length.

his or her responses to previous questions. Thus, the examination<br />

“adapts” to an individual test-taker’s ability level <strong>and</strong> more precisely<br />

measures that test-taker’s proficiency. Considerations for optimal<br />

test design include the size <strong>and</strong> quality of the item bank, the<br />

number of test-takers <strong>and</strong> the frequency of test administration.<br />

Equating <strong>and</strong> scaling<br />

Through the procedure known as equating, passing st<strong>and</strong>ard values<br />

are adjusted so that an equivalent level of proficiency is required<br />

to pass different versions of the examination. The goal of this<br />

process is to make sure that each test-taker receives a statistically<br />

equivalent examination: one that is neither statistically easier nor<br />

harder than that received by any other test-taker.<br />

A method typically utilized by <strong>Pearson</strong> <strong>VUE</strong> employs IRT to<br />

calibrate items from two or more test forms to the same scale.<br />

IRT uses statistical models to quantitatively link all item parameters<br />

to a common benchmark scale. <strong>Pearson</strong> <strong>VUE</strong> then develops an<br />

IRT-calibrated item bank. When items are linked to a common<br />

scale, test forms can be created <strong>and</strong> passing st<strong>and</strong>ards set such that<br />

slight differences in test difficulty across forms are accounted for.<br />

Test forms are drawn from the calibrated item bank <strong>and</strong> no item<br />

appears on a test before it has been trialled <strong>and</strong> equated to the<br />

benchmark scale. If a fixed-form test design is used, a fixed number<br />

of equated forms are prepared <strong>and</strong> are available for administration.<br />

A test form is r<strong>and</strong>omly selected for each test-taker. If a LOFT test<br />

design is used, the test form is assembled as the test-taker begins<br />

the computer-based test.<br />

Test functionality<br />

In addition to making decisions on the psychometric properties of<br />

the tests, test sponsors delivering tests in a CBT environment also<br />

need to consider which computerized features are appropriate<br />

for the desired measurement. The variety of functionality allowed<br />

through CBT means that technical test specifications are necessary<br />

as a complement to the test plan or test blueprint (the outline of<br />

the content requirements). Technical specifications may include the<br />

following details on items <strong>and</strong> their display in a CBT environment:<br />

• Navigation between test items<br />

• Guidelines on the inclusion of graphical images (for example,<br />

size <strong>and</strong> format)<br />

• Ancillary information to display with the test items (such as<br />

exhibits, instructions, calculators) <strong>and</strong> the format in which<br />

these will be displayed<br />

• Whether or not test-takers are allowed to go back to<br />

previous screens of the test or previous items<br />

When implementing CBT as a testing method, care should be<br />

exercised to ensure that its functionality enhances, <strong>and</strong> does not<br />

interfere, with the assessment of test-takers’ ability related to the<br />

testing purpose (2) .<br />

By working with <strong>Pearson</strong> <strong>VUE</strong> <strong>and</strong> through careful development of<br />

tests according to psychometric best practices <strong>and</strong> the considerate<br />

use of CBT functionality, test sponsors can create examinations<br />

that are <strong>valid</strong>, <strong>reliable</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>fair</strong>.<br />

References<br />

1: American Educational Research Association, American Psychological<br />

Association, & National Council on Measurement in Education. (1999).<br />

St<strong>and</strong>ards for educational <strong>and</strong> psychological testing. Washington, DC:American<br />

Educational Research Association.<br />

2: International Test Commission (2005). International Guidelines on Computer-<br />

Based <strong>and</strong> Internet Delivered Testing. http://www.intestcom.org/Downloads/<br />

ITC%20Guidelines%20on%20Computer%20-20version%202005%20approved.<br />

<strong>pdf</strong> (Retrieved 8 January 2012).<br />

de Klerk, G. Classical test theory (CTT). In M. Born, C.D. Foxcroft & R.<br />

Butter (Eds.), Online Readings in Testing <strong>and</strong> Assessment, International Test<br />

Commission, http://www.intestcom.org/Publications/ORTA.php (Retrieved 5<br />

December 2011).<br />

Construct irrelevant variance<br />

“The degree to which the test scores are<br />

affected by processes that are extraneous<br />

to its intended construct” (AERA, APA,<br />

NCME, 1999, p. 10)<br />

Construct underrepresentation<br />

“The degree to which a test fails to capture<br />

important aspects of the construct”<br />

(AERA, APA, NCME, 1999, p. 10)<br />

Equating<br />

The process of statistically adjusting the<br />

scoring of alternate forms of a test so that<br />

they use the same scoring scale.<br />

Item response theory (IRT)<br />

A statistical model for analyzing test-takers’<br />

performance on a set of test questions<br />

(items). Its basic assumption is that the<br />

probability that a test-taker will answer a<br />

test question correctly<br />

depends on one characteristic of the<br />

test-taker (called “ability”) <strong>and</strong> on one to<br />

three characteristics of the test question.<br />

The three characteristics of the test<br />

question are indicated by numbers called<br />

“parameters.”

<strong>Pearson</strong> <strong>VUE</strong> Sales Offices<br />

Americas<br />

Global Headquarters<br />

Minneapolis, MN<br />

+01 800 837 8969<br />

pvamericassales@pearson.com<br />

www.pearsonvue.com<br />

Philadelphia, PA<br />

+01 610 617 9300<br />

pvamericassales@pearson.com<br />

www.pearsonvue.com<br />

Chicago, IL<br />

+01 800 837 8969<br />

pvamericassales@pearson.com<br />

www.pearsonvue.com<br />

Asia Pacific<br />

Delhi, India<br />

+91 120 4001600<br />

pvindiasales@pearson.com<br />

www.pearsonvue.com<br />

Beijing, China<br />

+86 10 6849 2066<br />

pvchinasales@pearson.com<br />

www.pearsonvue.com.cn<br />

Tokyo, Japan<br />

+81 3 5214 0888<br />

pvjsales@pearson.com<br />

www.pearsonvue.com/japan<br />

Europe, Middle East & Africa<br />

Manchester, United Kingdom<br />

+44 0 161 855 7000<br />

vuemarketing@pearson.com<br />

www.pearsonvue.co.uk<br />

London, United Kingdom<br />

+44 0 161 855 7000<br />

vuemarketing@pearson.com<br />

www.pearsonvue.co.uk<br />

Dubai, United Arab Emirates<br />

+971 44 535300<br />

vuemarketing@pearson.com<br />

www.pearsonvue.ae<br />

Committed to developing<br />

<strong>valid</strong>, <strong>reliable</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>fair</strong> <strong>exams</strong><br />

To learn more, visit www.pearsonvue.com<br />

PV/3 Test Dev/US/9-12<br />

Copyright © 2012 <strong>Pearson</strong> Education, Inc. or its affiliate(s). All rights reserved. 800 837 8969