LB2882MaternalNutriti+ - Mead Johnson Nutrition

LB2882MaternalNutriti+ - Mead Johnson Nutrition

LB2882MaternalNutriti+ - Mead Johnson Nutrition

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

MATERNAL NUTRITION<br />

bY<br />

Elizabeth M. Ward, M.S., R.D.<br />

EDITED bY<br />

Anna Maria Siega-Riz, Ph.D., R.D.<br />

WITH<br />

Julia Boettcher, M.Ed., R.D.<br />

Elisha London, R.D.<br />

Brittney Drone, B.S.

IFC

TAbLE OF CONTENTS<br />

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3<br />

INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5<br />

NUTRITION BEFORE PREGNANCY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6<br />

Pre-pregnancy Body Weight and Pregnancy Outcome . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6<br />

Preconception Diabetes and Pregnancy Outcome. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6<br />

Preconception Care. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7<br />

NUTRITION DURING PREGNANCY AND LACTATION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7<br />

Pregnancy Weight Gain Guidelines . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7<br />

Nutrient Needs during Pregnancy and Lactation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9<br />

Energy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9<br />

Carbohydrate . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10<br />

Protein . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10<br />

Fat . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11<br />

Vitamins . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13<br />

Folate and Folic Acid . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15<br />

Vitamin B12 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15<br />

Choline . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15<br />

Vitamin A . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16<br />

Vitamin D . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17<br />

Minerals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17<br />

Iron . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19<br />

Calcium . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20<br />

Zinc . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20<br />

Iodine . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21<br />

Multivitamin Use during Pregnancy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21<br />

DESIGNING HEALTHY LIFESTYLE PLANS FOR WOMEN IN THE CHILDBEARING YEARS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22<br />

Guides to Healthy Eating . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22<br />

Guidelines for Physical Activity during Pregnancy and Lactation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23<br />

ALCOHOL, CAFFEINE, AND OTHER FOOD SAFETY ISSUES IN WOMEN OF CHILDBEARING AGE . . . . . . . . . . 24<br />

Alcohol . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24<br />

Caffeine . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24<br />

FOOD SAFETY ISSUES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25<br />

Fish and Seafood . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25<br />

Foodborne Pathogens . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25<br />

PREGNANCY-ASSOCIATED CONDITIONS AND POSSIBLE DIET AND LIFESTYLE INTERVENTIONS . . . . . . . . . 26<br />

Nausea, Vomiting, and Hyperemesis Gravidarum . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26<br />

Hypertensive Disease . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26<br />

Gestational Diabetes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27<br />

Preterm Birth . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28<br />

1

CONCLUSION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28<br />

REFERENCES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30<br />

LIST OF FIGURES<br />

Figure 1. Differences in Vitamin Intake Recommendations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14<br />

Figure 2. Differences in Mineral Intake Recommendations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18<br />

LIST OF TAbLES<br />

Table 1. Criteria for Classifi cations of Pre-pregnancy Weight Status BMI (kg/m 2 ). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8<br />

Table 2. Recommended Weight Gain for Pregnant Women . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8<br />

Table 3. Recommended Weekly Rate of Weight Gain for Singleton Pregnancies, 2nd and 3rd Trimesters . . . . . . . 8<br />

Table 4. Recommendations for Additional Daily Calorie Intake during Pregnancy and Lactation . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10<br />

Table 5. Protein Recommendations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11<br />

Table 6. Recommended Intakes for LCPUFA during Pregnancy and Lactation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12<br />

Table 7. Selected Food Sources of DHA . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13<br />

Table 8. Recommended Vitamin Intakes for Women during Pregnancy and Lactation, Ages 19 to 50 years . . . . 14<br />

Table 9. Recommended Mineral Intakes for Women during Pregnancy and Lactation, Ages 19 to 50 years . . . . 18<br />

Table 10. WHO Recommended Nutrient Intakes for Zinc during Pregnancy and Lactation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21<br />

Table 11. Selected Sources of Caffeine . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24<br />

Table 12. Selected Foodborne Pathogens and Risks to Maternal and Fetal Health . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26<br />

MATERNAL NUTRITION 2

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY<br />

A mother’s nutritional status, diet and lifestyle influence pregnancy and lactation outcomes and can have lasting<br />

effects on her offspring’s health. This monograph reviews current nutrition and nutrition-related recommendations for<br />

women during pregnancy and lactation. The goal in highlighting these recommendations is to increase familiarity with<br />

nutrients and nutrition-related issues that can have an important impact during pregnancy, lactation, and beyond.<br />

Experts around the world increasingly emphasize the importance of providing preconception health services that<br />

include screening for health risks that could affect the outcome of a future pregnancy. 1,2 Women should be counseled<br />

regarding the benefits of achieving a healthy weight prior to pregnancy, regular physical activity, consuming a<br />

balanced diet with adequate folic acid, and controlling preexisting medical conditions, such as diabetes, along with<br />

other factors that influence pregnancy outcome. 2<br />

To help optimize conception and pregnancy outcomes, women should strive to enter pregnancy with a Body Mass<br />

Index (BMI) within the normal range (18.5 to 24.9 kg/m 2 ). 3 Weight-gain and weight-monitoring recommendations<br />

during pregnancy vary around the world 4 and women should follow recommendations endorsed by experts in their<br />

countries. In 2009, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) in the United States updated its pregnancy weight gain guidelines<br />

as a result of rising obesity rates, the large proportion of women with high gestational weight gain, and the strength<br />

of the evidence linking gestational weight gain to certain adverse outcomes. 3 The recommended weight gain ranges<br />

vary significantly according to a woman’s pre-pregnancy BMI. Women within the normal BMI range should gain<br />

between 25 and 35 pounds. Overweight and obese women are encouraged to gain less (15 to 25 pounds for<br />

overweight women; 11 to 20 pounds for obese women). 3<br />

Recommended intakes for energy and the macronutrients, carbohydrate and protein, increase during pregnancy<br />

and are easily achieved by most women who are eating a balanced diet. 5-7 Recommended intake for total fat, as a<br />

percentage of energy, does not increase during pregnancy and lactation. 5,8 However, the importance of consuming<br />

long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFA), particularly docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), during pregnancy and<br />

lactation has received increased emphasis in recent years. Exact requirements for DHA during pregnancy and<br />

lactation have not been determined but in 2010 three groups published recommendations on DHA intakes. The<br />

minimum amount of DHA recommended during pregnancy and lactation by these groups is 200 mg per day. 8-10<br />

Recommended intakes of several vitamins and minerals also increase during pregnancy and lactation and many of<br />

these recommendations can be met with a balanced diet. While appropriate intake of all vitamins and minerals is<br />

important, some deserve particular attention with pregnancy. For example, adequate folic acid intake prior to and<br />

during the first few weeks of pregnancy is associated with a reduced risk of neural tube defects (NTDs) 11,12 and<br />

observational studies suggest that adequate choline intake during early pregnancy may positively influence neural<br />

tube closure, independent of folate. 13,14 Emerging evidence indicates that vitamin D may play an important role<br />

in immunity and neurocognitive development in addition to its roles in calcium homeostasis and bone health. 15,16<br />

Inadequate intakes of vitamin A, iron and iodine are associated with night-blindness, anemia, and brain damage,<br />

respectively. 17-19 While adequate intakes of vitamins and minerals during pregnancy are essential, excessive intakes of<br />

some can have negative consequences and should be avoided. For example, excessive intake of preformed vitamin<br />

A (retinoids) during pregnancy increases the risk of birth defects. 20,21<br />

Food guides can be used by women and their health care providers to design balanced eating plans before<br />

pregnancy for achieving desirable weight, and to support a healthy pregnancy and lactation. Some countries around<br />

the world have adopted food guides based on those developed in the US while others have developed their own<br />

specific guides that are based on the country’s food supply, food consumption patterns, nutrition issues and nutrition<br />

standards. 22 Women should use food guides that are adopted by the countries in which they live.<br />

3

Research indicates that the risk of an adverse pregnancy outcome associated with moderate-intensity physical<br />

activity, such as brisk walking, is very low for healthy pregnant women. 23 Physical activity can be benefi cial in<br />

controlling blood glucose levels and promoting weight gain within target ranges. Women with uncomplicated<br />

pregnancies should participate in at least 150 minutes (2 hours, 30 minutes) of moderate-intensity aerobic activity a<br />

week which may be divided up into fi ve, 30-minute walks per week or into bouts of 10-minutes of physical activity<br />

at a time. 3,23-25 Most women with uncomplicated pregnancies and deliveries can begin exercising a few weeks<br />

after delivery; others will need to wait longer. A gradual return to a pre-pregnancy level of physical activity is most<br />

prudent, 26 especially for women who have cesarean deliveries and those on bed rest during pregnancy. Gradual<br />

weight loss resulting from exercise and calorie restriction does not appear to compromise lactation performance. 27,28<br />

Women should be counseled to avoid all alcohol during pregnancy since there is no known safe intake. 29,30 Research<br />

studies linking caffeine intake to pregnancy complications are confl icting but it is prudent to limit intake of caffeine to<br />

200 mg/day during pregnancy. 31-34 Methyl mercury, found in high levels in certain species of fi sh, is neurotoxic 35 and<br />

women of childbearing age should avoid fi sh with high concentrations of methyl mercury. 36,37 Levels of neurotoxic<br />

contaminants in fi sh vary widely among regions of the world. Therefore, it is important to check with national and<br />

regional authorities for information on the levels of contaminants found in fi sh consumed in that region and for<br />

recommendations on fi sh consumption. 35<br />

Pregnant women are also more susceptible to foodborne illnesses and their effects. 38 Women in the childbearing<br />

years should be educated about how best to handle and prepare food, and about which foods are particularly<br />

risky due to possible contamination with micro-organisms including Taxoplasma gondii, Listeria monocytogenes,<br />

Escherichia coli and salmonella.<br />

Some conditions and complications associated with pregnancy, such as nausea and vomiting, and hypertensive<br />

disease, may potentially benefi t from diet and lifestyle interventions. 3,39 In addition, women with gestational diabetes<br />

will benefi t from glycemic control and should be counseled about a balanced diet that fosters normal blood glucose<br />

and meets pregnancy nutrient needs. 40<br />

There is no doubt about the strong connection between maternal health habits and fetal and infant well-being. Eating<br />

a balanced diet, ensuring adequate micronutrient intakes, getting regular physical activity, and avoiding noxious<br />

substances are increasingly regarded as strategies for achieving good pregnancy and lactation outcomes.<br />

MATERNAL NUTRITION 4

INTRODUCTION<br />

A mother’s nutritional status, diet and lifestyle influence pregnancy and lactation outcomes and can have lasting<br />

effects on her offspring’s health. For example, inadequate intakes of certain micronutrients during pregnancy,<br />

such as folic acid and iodine, can contribute to birth defects and/or the inability of the child to develop to his or<br />

her full cognitive potential. In addition, maternal overweight and obesity are increasing globally and present major<br />

challenges for health care providers and their clients since overweight and obesity are associated with several<br />

adverse pregnancy outcomes including birth defects, gestational diabetes, pre-eclampsia and cesarean section. 41,42<br />

Undernutrition and overconsumption during fetal life may also influence the infant’s cognition and future risk of<br />

coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes, stroke, obesity, and hypertension. 3,43-45 A mother’s consumption of potentially<br />

harmful substances, such as alcohol, during pregnancy can also have irreversible negative consequences.<br />

With the growing body of evidence indicating that a woman’s nutritional status and health-related behaviors both<br />

prior to and during pregnancy influence pregnancy outcomes and the child’s future health, experts are placing more<br />

emphasis on preconception and inter-pregnancy care. This includes screening for health risks that could affect the<br />

outcome of a future pregnancy. Many of those risks, such as poorly-controlled diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and<br />

a poor quality diet, are amenable to positive lifestyle changes. Women are encouraged to achieve and remain at a<br />

healthy body weight prior to pregnancy. 3 They should also be counseled regarding the benefits of physical activity,<br />

avoiding food faddism, consuming adequate folic acid and maintaining good control of medical conditions. 2 After<br />

conception has occurred, a balanced diet that supports appropriate maternal weight gain and meets maternal and<br />

fetal micronutrient needs contributes to creating a favorable intrauterine environment to support optimal pregnancy<br />

outcomes. 5 Good nutrition continues to be important after birth since a diet with insufficient levels of critical nutrients<br />

during lactation can deplete maternal stores and may lower nutrient levels in breast milk. Furthermore, breastfeeding<br />

beyond 6 months, regular physical activity and a balanced diet with an appropriate amount of energy help hasten the<br />

return to pre-pregnancy weight. 27<br />

Many countries around the world have issued diet and nutrient intake recommendations for their populations,<br />

including pregnant and lactating women, which are based on the countries’ food supply, food consumption patterns,<br />

and specific nutrition-related issues. 22 Other countries have adopted recommendations (Dietary Reference Intakes<br />

[DRI]) issued by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) of the National Academies in the United States or The World Health<br />

Organization (WHO). This monograph reviews current nutrition recommendations for women during pregnancy and<br />

lactation primarily from the renowned IOM and WHO. The goal in highlighting these nutrition recommendations is to<br />

increase familiarity with nutrients and nutrition-related issues that can have an important impact during pregnancy,<br />

lactation, and beyond.<br />

5

NUTRITION bEFORE PREGNANCY<br />

Pre-pregnancy body Weight and Pregnancy Outcome<br />

A mother’s nutritional status prior to pregnancy can affect reproduction and pregnancy outcomes, and pre-pregnancy<br />

weight is a common indicator of a woman’s nutritional status. 46 Body Mass Index (BMI) describes body weight in<br />

relation to height and is commonly used in nutrition assessments. It is defi ned as an individual’s body weight (mass)<br />

divided by the square of his or her height (kg/m 2 ). A BMI of less than 18.5 is defi ned as underweight while a BMI ≥ 25<br />

indicates overweight. Obesity is defi ned as a BMI ≥ 30. 3<br />

A low pre-pregnancy BMI may indicate chronic nutritional insuffi ciency 47 and women with a low BMI may have<br />

delayed conception. 48 Women with a low pre-pregnancy BMI are also at increased risk for having an infant with low<br />

birth-weight, or an infant that is small for gestational age or born preterm. 47 Increasingly, however, women around<br />

the world are entering pregnancy overweight or obese. For example, in 2006 it was reported that of women 20<br />

years of age or older in the United States, about 62% had a BMI ≥ 25 and approximately 33% of those women were<br />

considered obese (BMI ≥ 30). 49 Consequently, health experts are placing increased emphasis on the relationship<br />

between overweight and obesity and the potential for sub-optimal reproductive and pregnancy outcomes.<br />

Excess adiposity can hinder a woman’s ability to have regular menstruation and subsequently lead to diffi culty in<br />

conceiving. 48,50 In addition, obesity at the time of conception is associated with many pregnancy complications<br />

including gestational diabetes, hypertension, pre-eclampsia, cesarean delivery, macrosomia, and perintatal<br />

mortality. 3,46 Infants born to obese women also have a higher incidence of congenital defects 4 and greater fat mass<br />

and subsequent overweight in childhood. 3,51 Pre-pregnancy weight status may have implications for infant feeding,<br />

too. Research indicates that women who begin pregnancy obese are also less likely to initiate breastfeeding 52,53 and<br />

to continue full breastfeeding at one month and three months when compared with normal-weight counterparts. 52<br />

They are also more likely to have shorter duration of any breastfeeding. 53<br />

While BMI is a useful, easy screening tool for predicting excess body fat, it does have limitations. For example, very<br />

muscular, fi t women may be considered overweight by BMI standards, even though they are healthy and free of<br />

chronic conditions; other women with body weights within the healthy weight range may have undesirable lipid and/<br />

or blood glucose profi les or poor nutritional reserves, including low iron reserves, which could affect the outcome of a<br />

future pregnancy. A very low BMI, however, is a reliable indicator of low levels of fat and lean tissue due to inadequate<br />

intake. 47<br />

Preconception Diabetes and Pregnancy Outcome<br />

The incidence of diabetes mellitus around the world is on the rise. For example, an estimated 12.6 million (10.8%)<br />

women in the US age 20 and older have diabetes, but many are unaware of their condition. Most cases of diabetes<br />

in adults are type 2 diabetes which is related to obesity. 54<br />

Women with poorly controlled type 1 or type 2 diabetes or those with pre-gestational diabetes are more likely to<br />

deliver an infant with a birth defect than women without diabetes or those who enter pregnancy with normal glucose<br />

levels. 55 Results from the seven-year Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes study demonstrated a<br />

positive relationship between elevated maternal blood glucose levels between weeks 24 and 32 of gestation and<br />

birth-weight above the 90th percentile for gestational age, primary cesarean delivery, neonatal hypoglycemia, and<br />

cord-blood serum C-peptide level above the 90th percentile. Five secondary outcomes – premature delivery, shoulder<br />

dystocia or birth injury, intensive neonatal care, hyperbilirubinemia, and pre-eclampsia – also showed continuous<br />

positive linear associations with blood glucose levels. These data illustrate that the higher the maternal blood glucose<br />

concentrations, the greater the likelihood of these pregnancy complications. 56<br />

MATERNAL NUTRITION 6

Preconception Care<br />

In 2005, the WHO’s World Report 2005: Make Every Mother and Child Count detailed the importance of<br />

preconception care and indicated that reproductive health is an essential element of the continuum of maternal and<br />

child health. It called for reform of programs and interventions at the country and international level. 1 Since 2005, a<br />

number of programs and guidelines have been revised or developed but they vary in scope and content due to a<br />

number of factors including the type of health care system, level of economic support, political, cultural, and religious<br />

beliefs of the locale. Despite the differences in the programs and guidelines, the concept of preconception care<br />

remains a critical component of maternal and child health promotion globally. 57<br />

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has issued recommendations on preconception care for<br />

women. 2,58 The recommendations include screening for health risks that could affect the outcome of a future<br />

pregnancy. Many of those risks, such as obesity, poorly-controlled diabetes, and inadequate diet are amenable to<br />

positive lifestyle changes. Women should be counseled regarding the benefits of physical activity, achieving a healthy<br />

weight prior to pregnancy, avoiding food faddism, consuming adequate folic acid, and controlling preexisting medical<br />

conditions, such as diabetes, along with other factors that influence pregnancy outcome. 2 Pregnancy preparedness<br />

is wise even when a woman does not plan to conceive since many pregnancies are unintended. For example, in the<br />

United States, an estimated 50% of pregnancies are unintended or mistimed. 59 During the first seven to eight weeks<br />

of pregnancy, when women may not realize they are pregnant, a developing fetus is highly susceptible to congenital<br />

anomalies and other adverse outcomes as a result of exposure to alcohol, tobacco and other drugs, workplace<br />

hazards, and inadequate intake of essential nutrients, such as folic acid. 60<br />

NUTRITION DURING PREGNANCY AND LACTATION<br />

Pregnancy Weight Gain Guidelines<br />

Starting pregnancy with a healthy weight and gaining appropriately during pregnancy typically translates into a lower<br />

risk of complications for mother and child. 3 However, women who are attempting to lose weight prior to conception<br />

should stop once pregnancy has occurred.<br />

Weight-gain and weight-monitoring recommendations during pregnancy vary around the world. 4 Many countries<br />

in Europe, for example, do not weigh pregnant women after their first antenatal visit, 4 while others have developed<br />

population-specific pregnancy weight-gain curves based on research of weight gain and pregnancy outcomes in their<br />

countries. 61,62 In 2004, the Report of a Joint FAO/WHO/UNU Expert Consultation on human energy requirements 6<br />

stated,<br />

“This consultation endorsed the WHO recommendation that healthy, well-nourished women should gain 10 to<br />

14 kg [22 to 30.8 pounds] during pregnancy, with an average of 12 kg [26.4 pounds], in order to increase the<br />

probability of delivering full-term infants with an average birth weight of 3.3 kg, and to reduce the risk of foetal<br />

and maternal complications.”<br />

According to the Expert Consultation, underweight women (with a BMI 25 may benefit with weight gains near the lower end of the range. 6<br />

In 2009, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) in the United States updated its guidelines for weight gain during pregnancy<br />

as a result of rising obesity rates in women, the large proportion of women with high gestational weight gain, and the<br />

strength of the evidence linking gestational weight gain to certain adverse outcomes. 3 The 2009 recommendations<br />

are an attempt to balance the risks and benefits associated with gestational weight gain for both the mother and<br />

child. The IOM stated that while the guidelines are intended for use in the United States, “They may be applicable to<br />

7

women in other developed countries.” 3 For example, Canada has adopted the IOM guidelines. 63 The IOM guidelines,<br />

however, are “not intended for use in areas of the world where women are substantially shorter or thinner than<br />

American women or where adequate obstetric services are unavailable.” 3 The IOM guidelines are reviewed here.<br />

The 2009 IOM recommendations adopted the World Health Organization (WHO) BMI categories to classify women’s<br />

weight. The WHO categories make the 2009 weight gain recommendations for pregnancy congruent with those of<br />

the non-pregnancy state (Table 1) and set an upper limit of weight gain for obese women (Table 2). The weight gain<br />

range for obese women in the IOM’s latest recommendations was primarily based on data for women with BMIs in<br />

the range of 30 to 34.9 kg/m. 2 Thus, women with higher BMIs are encouraged to gain at the lower end of the range. 3<br />

TAbLE 1. CRITERIA FOR CLASSIFICATIONS OF PRE-PREGNANCY WEIGHT STATUS bMI (kG/M 2 ) 3<br />

bMI<br />

Underweight

Nutrient Needs during Pregnancy and Lactation<br />

A balanced diet that supports appropriate maternal weight gain and meets maternal and fetal nutrient needs<br />

contributes to creating a favorable intrauterine environment. 5 However, for a variety of reasons, pregnant and<br />

lactating women often do not consume the recommended amounts of essential nutrients. Inadequate micronutrient<br />

intake during pregnancy and lactation has been attributed to factors such as increased nutritional needs, maternal<br />

age, geography, and socioeconomic status. 21,65<br />

In the following sections, recommended intakes for energy, macro- and micronutrients during pregnancy and<br />

lactation are summarized.<br />

Energy<br />

The energy cost of pregnancy (measured in calories or kilojoules) includes energy needed for accretion of maternal,<br />

fetal and placental tissues, increases in the mother’s basal metabolism, and the mother’s physical activity level.<br />

Table 4 summarizes recommendations for additional daily calorie intakes during pregnancy and lactation. The FAO/<br />

WHO/UNU Expert Consultation on human energy requirements recommended an additional intake of 85, 285 and<br />

475 kcal/d during the first, second and third trimesters of pregnancy, respectively. 6 The IOM Dietary Reference<br />

Intakes do not recommend an increase in daily calorie intake during the first trimester of singleton pregnancies. 5<br />

Women are advised to increase their daily calorie intakes during pregnancy according to their pre-pregnancy body<br />

weight, physical activity level, and weeks gestation. The suggested calorie increase for women who conceive at a<br />

body weight in the normal range is 340 calories a day in the second trimester and 450 calories a day in the third<br />

trimester. 5 It has been suggested that in the US, women pregnant with multiple fetuses need about 500 calories a<br />

day beyond what is required for a singleton pregnancy starting in the first trimester. 66<br />

The amount of milk that a woman produces and secretes as well as the milk’s energy content influence the energy<br />

cost of lactation. 67 The FAO/WHO/UNU Expert Consultation on human energy requirements recommended<br />

that well-nourished lactating women consume an additional 505 kcal/d during the first 6 months of lactation.<br />

Undernourished women should consume more: an additional 675 kcal/d. The expert consultation did not make<br />

recommendations for the second 6 months of lactation since milk production is more highly variable during this<br />

time. 67 The IOM daily calorie intake recommendations for lactating women are based on pre-pregnancy calorie<br />

requirements for weight maintenance for women within the normal weight range. The IOM recommends that women<br />

in the normal weight range consume 330 additional calories per day for the first six months after delivery and 400<br />

additional calories each day for months six through 12 of their infant’s life. 5 Overweight and obese women and<br />

women who gained too much weight during pregnancy may not need to consume additional energy. Research<br />

indicates that once lactation is established, breastfeeding women with a post-pregnancy BMI >25 may restrict their<br />

intake by 500 kilocalories per day and exercise to promote weight loss without affecting infant growth. 27,68<br />

9

TAbLE 4. RECOMMENDATIONS FOR ADDITIONAL DAILY CALORIE INTAkE DURING PREGNANCY AND<br />

LACTATION 5,6,67<br />

Pregnancy IOM FAO/WHO/UNU<br />

1 st Trimester 0 85<br />

2 nd Trimester 340 285<br />

3 rd Trimester 450 475<br />

Lactation<br />

1 st 6 Months 330 505 a<br />

2 nd 6 Months 400 Varies depending on milk output<br />

a For women with adequate gestational weight gain. The recommendations for undernourished women and those with insuffi cient gestational<br />

weight gain is 675 kcal/d.<br />

Carbohydrate<br />

The primary role of dietary carbohydrate is to provide energy to cells. Sugars and starches supply energy in the<br />

form of glucose, which is the only energy source for red blood cells and is the preferred energy source for the brain,<br />

central nervous system, and fetus. 5 The U.S. Dietary Reference Intake (DRI) for carbohydrate for a pregnant woman<br />

19 to 50 years of age is a minimum of 175 grams of carbohydrate daily to provide adequate glucose for her body<br />

and for a single fetus. 5 This represents a daily increase of 45 grams above the non-pregnancy state and is easily<br />

achieved by most pregnant women who are eating a balanced diet. The DRI for lactation is higher (210 grams daily)<br />

to compensate for the carbohydrate secreted in breast milk. 5<br />

Fiber is non-digestible carbohydrate and lignin found in plant foods. 5 Benefi ts of dietary fi bers include feelings of<br />

fullness and improved laxation, which could help reduce the chances for hemorrhoids during pregnancy. Some<br />

types of dietary fi ber are also associated with lower postprandial blood glucose levels and reduced blood cholesterol<br />

concentrations. The Adequate Intake (AI) for fi ber during pregnancy and lactation is 14 grams per 1,000 calories. 5<br />

Thus, a pregnant woman with an estimated energy requirement of 2,400 calories should consume about 34 grams of<br />

fi ber daily. Most women do not consume enough fi ber and require counseling about including high-fi ber foods in their<br />

diet, such as dried beans and peas, vegetables, fruits, nuts, and whole grains, to meet the suggested intake.<br />

Protein<br />

Protein is a constituent of all cells and a component of enzymes, membranes, transport carriers, and many<br />

hormones. The amino acids from dietary proteins are utilized by the body for endogenous synthesis of structural<br />

proteins as well as enzymes, numerous hormones, immune factors and a plethora of other vital mediators of<br />

physiological function. 5 Pregnancy signifi cantly increases protein needs due to the increase in hormone production<br />

and plasma volume expansion, along with increased tissue formation for the placenta, fetus and breasts. During<br />

lactation, additional protein intake compensates for protein and non-protein nitrogen output in breast milk. 5<br />

The U.S. Dietary Reference Intakes recommended 0.8 g/kg/day of dietary protein for non-pregnant women. Starting<br />

in the second trimester, the recommended protein intake for pregnancy is 1.1 g/kg/day or about 25 g of additional<br />

protein per day. An additional 50 grams a day of protein is suggested for twin pregnancies beginning in the second<br />

trimester. 5 The WHO recommends that pregnant women consume 1, 9 and 31 g of additional protein daily during the<br />

fi rst, second and third trimesters, respectively. 7<br />

MATERNAL NUTRITION 10

During lactation, the U.S. Dietary Reference Intakes recommend that women consume 1.3 g/kg/d or about 25 g of<br />

additional protein daily. 5 The WHO recommends 19 and 12.5 g of additional protein daily for lactating women during<br />

the first and second 6 months, respectively (Table 5). 7<br />

With the exception of soy and quinoa, animal foods, such as meat, poultry, seafood, eggs, and dairy, are the only<br />

choices that provide all of the indispensable amino acids in a single food. Vegetarian diets that feature a mixture of a<br />

variety of plant foods in adequate amounts are capable of satisfying indispensable amino acid needs, too. Generally<br />

speaking, it is possible for vegetarian women to meet the recommended protein intake during pregnancy and<br />

lactation by eating a balanced diet.<br />

Table 5. Protein Recommendations 5,7<br />

Additional Daily Protein<br />

(g/day)<br />

IOM<br />

WHO<br />

Pregnancy<br />

1st Trimester 0 1<br />

2nd Trimester 25 9<br />

3rd Trimester 25 31<br />

Lactation<br />

1st 6 months 25 19<br />

2nd 6 months 25 12.5<br />

Fat<br />

Dietary fat provides energy (calories) and the essential fatty acids (EFA), linoleic acid and alpha-linolenic acid. Linoleic<br />

acid (LA; 18:2n-6; an 18-carbon, 2-double bond fatty acid) is the parent fatty acid of the n-6 (or omega-6) family of<br />

fats, including the long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid (LCPUFA) arachidonic acid (ARA; 20:4n-6). Alpha-linolenic<br />

acid (ALA; 18:3n-3; an 18-carbon, 3-double bond fatty acid) is the precursor of the n-3 (or omega-3) family of fatty<br />

acids including LCPUFAs eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA; 20:5n-3) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA; 22:6n-3). Dietary<br />

fat is also necessary for the absorption of the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K and participates in the transport of<br />

these and other fat-soluble compounds to cells and tissues.<br />

Daily total fat intake recommendations are related to energy requirements; fat should supply 20% to 35%<br />

of a woman’s total energy needs during pregnancy and lactation. 5,8 There are no dietary requirements for<br />

monounsaturated fatty acids, saturated fatty acids, or trans fatty acids. 5 The recommended daily limit for saturated<br />

fatty acids does not change during pregnancy and lactation and is less than 10% of total energy needs. 8,37 Trans fatty<br />

acid intakes, primarily from partially hydrogenated vegetable oils, should be as low as possible. 8,37<br />

LCPUFA intakes during pregnancy and lactation have received increased attention in recent years. The LCPUFA<br />

DHA is the predominant n-3 fatty acid in brain cells and comprises as much as 65% of the total fatty acids in certain<br />

phospholipids of the retina. 69 The metabolic demand for DHA increases during pregnancy. The mother requires more<br />

DHA to support expanded red blood cell mass and the placenta. In addition, the fetal brain and nervous system rapidly<br />

accumulate DHA during the last trimester of pregnancy. 70 The increased metabolic need for DHA is met by synthesis<br />

from the precursor ALA, maternal stores, and maternal DHA intake. 70 Intake of DHA by pregnant women in industrialized<br />

11

countries varies considerably (mean 70 to 200 mg/day) and the median intake (30-50 mg/day) 70 is lower than the<br />

estimated amount that the fetus accrues daily during the last trimester (~75mg/day of n-3 LCPUFA, mostly DHA). 71<br />

DHA supplementation during pregnancy has been linked to benefi cial outcomes, including slightly longer gestation<br />

(within the normal range of gestation) and slightly higher infant birth-weight. 70,72 There is some evidence to suggest<br />

that maternal DHA supplementation during pregnancy improves infants’ visual acuity, cognitive development, and<br />

immune outcomes. 72,73 Emerging evidence suggests that maternal DHA supplementation may affect infant body<br />

composition later in life by lowering adiposity. 70<br />

After delivery, DHA continues to rapidly accumulate in the infant brain during the fi rst 18 to 24 months of life. 74 Human<br />

milk contains DHA but the amount varies with maternal intake. 72 Brenna and colleagues 75 reported the worldwide<br />

average level of DHA in mature human milk as 0.32 ± 22% (% fatty acids ± SD) with a wide range of 0.06% to 1.4%.<br />

Coastal or island populations with high intakes of marine foods had the highest breast milk DHA levels while inland<br />

populations and developed countries had the lowest. Supplementing DHA intake of lactating women increases breast<br />

milk DHA content but supplementation with the DHA precursor, ALA, does not. 72<br />

Observational studies and intervention trials of breastfed infants indicate that DHA levels in human milk infl uence<br />

infant outcomes. 72 In observational studies, higher DHA levels in human milk and/or infant blood have been<br />

associated with better infant visual acuity when compared with lower levels. 76 In addition, several intervention trials<br />

have found that maternal DHA or DHA+EPA supplementation positively affects neural development of breastfed<br />

infants. 76,77<br />

Exact requirements for DHA during pregnancy and lactation have not been determined but in 2010 three groups<br />

published recommendations on DHA intakes. The Joint FAO/WHO Expert Consultation on Fats and Fatty Acids in<br />

Human <strong>Nutrition</strong> recommended that pregnant and lactating women consume at least 200 mg DHA per day (Table<br />

6). 8 In addition, the French Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health & Safety (ANSES) 9 considered<br />

DHA to be an essential fatty acid in their update of the French population reference intakes (Apports nutritionnels<br />

conseillés or ANCs); they established ANCs for DHA of 250 mg DHA per day for pregnant and lactating women. 9<br />

Also in 2010, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), in their Scientifi c Opinion on Dietary Reference Values<br />

for Fats and Fatty Acids, established an adequate intake (AI) of 250 mg of EPA + DHA per day for adults. EFSA<br />

recommended that 100 to 200 mg of preformed DHA be added to this daily intake during pregnancy and lactation. 10<br />

Previously (2007), a Consensus Statement from the Perinatal Lipid Intake Working Group (on behalf of the European<br />

Commission Perinatal Lipid Metabolism [PeriLip] and Early <strong>Nutrition</strong> Programming [EARNEST] research projects,<br />

jointly with representatives of seven other international nutrition or medical organizations) recommended that pregnant<br />

and lactating women consume at least 200 mg DHA per day. 78<br />

Experts have concluded that there is no evidence indicating that intake of dietary n-6 fatty acids, including ARA,<br />

should be increased during pregnancy and lactation. 72 In addition, no recommendation for EPA intake alone during<br />

pregnancy and lactation has been made since EPA has only been studied with DHA as a component of fi sh or a fi sh<br />

oil preparation 72 (Table 6).<br />

TAbLE 6. RECOMMENDED INTAkES FOR LCPUFA DURING PREGNANCY AND LACTATION 8<br />

Recommended Intake Upper Intake Limit<br />

DHA 200 mg/day 1.0 g/day<br />

DHA + EPA 300 mg/day 2.7 g/day<br />

ARA No recommendation 800 mg/day<br />

MATERNAL NUTRITION 12

The United States has not established recommended intakes for DHA. The US Dietary Guidelines for Americans<br />

2010, however, recognized the importance of DHA during pregnancy and lactation. 37 The Guidelines state,<br />

“Moderate evidence indicates that intake of omega-3 fatty acids, in particular DHA, from at least 8 ounces<br />

of seafood per week for women who are pregnant or breastfeeding is associated with improved infant health<br />

outcomes, such as visual and cognitive development. Therefore, it is recommended that women who are<br />

pregnant or breastfeeding consume at least 8 and up to 12 ounces of a variety of seafood per week, from<br />

choices that are lower in methyl mercury.”<br />

Cold water, ocean-faring fatty fish, such as salmon and tuna, are among the richest natural sources of DHA. DHA is<br />

present naturally in lesser amounts in organ meats, poultry and eggs and is found in DHA-fortified foods (Table 7).<br />

The presence of methyl mercury and other neurotoxic chemicals in fish and shellfish is a potential concern for women<br />

in their childbearing years. 36 The US Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2010 state that women who are pregnant or<br />

breastfeeding should not eat tilefish, shark, swordfish and king mackerel because they are high in mercury. 37 Fortified<br />

foods and dietary supplements containing DHA, either derived from single-cell organisms or fish oil that have been<br />

processed to remove potential contaminants, are also sources of preformed DHA for pregnant and lactating women<br />

who do not eat enough DHA-rich foods.<br />

Table 7. Selected Food Sources of DHA<br />

Food<br />

DHA (mg)<br />

Salmon, coho, farmed, 3 oz, cooked 706<br />

Tuna, light, canned, drained, 3 oz 190<br />

Catfish, 3 oz, cooked 116<br />

Blue crab, 3 oz, cooked 57<br />

Fortified eggs, 1 large 57<br />

Chicken, roasted, dark meat, 3 oz 45<br />

Eggs, 1 large 29<br />

Sources: www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/foodcomp/search/. Accessed 09/12<br />

Fortified Eggs: www.egglandsbest.com. Accessed 09/12<br />

Vitamins<br />

Recommended intakes of several vitamins increase during pregnancy and lactation. Figure 1 compares<br />

recommended intakes of select vitamins for non-pregnant women (19 to 30 years old) with those of pregnant or<br />

lactating women of the same age.<br />

13

FIGURE 1. DIFFERENCES IN VITAMIN INTAkE RECOMMENDATIONS<br />

200%<br />

180%<br />

160%<br />

140%<br />

120%<br />

100%<br />

80%<br />

60%<br />

40%<br />

20%<br />

0%<br />

Vitamin C<br />

Vitamin D<br />

Vitamin E<br />

Vitamin K<br />

Thiamin<br />

Riboflavin<br />

Vitamin A<br />

Niacin<br />

Vitamin B6<br />

Pantothenic Acid<br />

Pregnancy, 19-30 years<br />

Lactation, 19-30 years<br />

Biotin<br />

Choline<br />

Folate<br />

Vitamin B12<br />

100% represents the DRI for non-pregnant and<br />

non-lactating women ages 19-30 years. The<br />

bar graphs illustrate the percentage of the nonpregnant/non-lactating<br />

DRI recommended for<br />

pregnant and lactating women.<br />

Specifi c recommendations for pregnancy and<br />

lactation are provided in Table 8. It is important<br />

for pregnant women to consume adequate<br />

amounts of all essential vitamins. Some vitamins<br />

that deserve special attention during pregnancy<br />

and/or lactation are highlighted.<br />

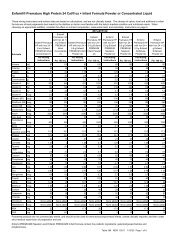

TAbLE 8. RECOMMENDED VITAMIN INTAkES FOR WOMEN DURING PREGNANCY AND LACTATION,<br />

AGES 19 TO 50 YEARS 21,79,80<br />

Nutrient<br />

Vitamin A ac , µg RAE<br />

Vitamin C ac , mg<br />

Pregnancy<br />

Lactation<br />

IOM WHO/FAO IOM WHO/FAO<br />

770<br />

(2541 IU)<br />

85<br />

800<br />

1300<br />

(4290 IU)<br />

850<br />

55 120 70<br />

250%<br />

200%<br />

150%<br />

100%<br />

50%<br />

0%<br />

Vitamin D ac , µg<br />

15<br />

(600 IU)<br />

MATERNAL NUTRITION 14<br />

5<br />

(200 IU)<br />

15<br />

(600 IU)<br />

5<br />

(200 IU)<br />

Vitamin E a , mg 15 - 19 -<br />

Vitamin K bc , ug 90 55 90 55<br />

Vitamin B1 ac (thiamin), mg 1.4 1.4 1.4 1.5<br />

Vitamin B2 ac (riboflavin), mg 1.4 1.4 1.6 1.6<br />

Vitamin B3 ac (niacin), mg 18 18 17 17<br />

Vitamin B6 ac , mg Pregnancy, 1.9 19-30 years 1.9 2.0 2.0<br />

Pantothenic Acid bc , mg Lactation, 6 19-30 years 6 7 7<br />

Biotin bc , µg 30 30 35 35<br />

Choline b , mg 450 - 550 -<br />

Folate ac , µg 600 600 500 500<br />

Vitamin B12 ac , µg 2.6 2.6 2.8 2.8<br />

a Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA)<br />

b Adequate Intake (AI)<br />

c Recommended Nutrient Intake (RNI)<br />

Intakes are per day, unless otherwise noted.<br />

Calcium<br />

Chromium<br />

Copper<br />

Fluoride<br />

Iodine<br />

Iron<br />

Magnesium<br />

Manganese<br />

Molybdenum<br />

Phosphorus<br />

Selenium<br />

Zinc<br />

Potassium<br />

Sodium<br />

Chloride

Folate and Folic Acid<br />

Folate is a generic term for a B-complex vitamin. Folate is found naturally in plant foods while folic acid is its synthetic<br />

counterpart that is added to enriched grains and dietary supplements. 81 Folate is central in the production of cells,<br />

particularly red blood cells, for nucleic acid synthesis, cell division, and for normal serum homocysteine levels. 81,82<br />

Adequate folic acid intake prior to conception and during the first 28 to 30 days of pregnancy is associated with<br />

a reduced risk of neural tube defects (NTDs). 11,12 Women with pre-gestational diabetes and obese women are at<br />

increased risk of having a pregnancy affected by a NTD and they may benefit from higher intakes of folic acid, though<br />

the exact mechanism as to why this occurs and the actual amount needed are uncertain. 83<br />

Due to the importance of folate in fetal development, various approaches have been implemented around the world<br />

in an attempt to increase the folate status for women of childbearing age. These approaches include voluntary or<br />

mandatory fortification of foods and/or recommendations for folic acid supplementation for women of childbearing<br />

age with associated public health campaigns. 84 Mandatory food fortification programs are in place in many countries 85<br />

and reports have demonstrated a decrease in the prevalence of neural tube defects associated with folic acid<br />

fortification in the US, Canada, Chile, South Africa, Costa Rica, Argentina, and Brazil. 85 The U.S. Preventive Services<br />

Task Force recommends that women of childbearing age with no history of a NTD-affected pregnancy consume 400<br />

to 800 µg of folic acid daily from foods and/or vitamin supplements before and during early pregnancy, while women<br />

with a history of a NTD-affected pregnancy should consult with their physician about taking 4 mg of folic acid daily to<br />

prevent a recurrence. 11 Similar recommendations are in place in various countries around the world. 86<br />

The health benefits of folic acid intake during pregnancy may go beyond those associated with preventing structural<br />

birth defects. 87,88 Periconceptionally, and throughout pregnancy, low dietary folate intake and low circulating blood<br />

folate concentrations have been associated with higher risks of preterm delivery, low birth weight, and fetal growth<br />

restriction. 82,89,90<br />

The IOM recommends 600 µg of dietary folate equivalents (DFE) daily for pregnant women of all ages, and during<br />

lactation, 500 µg/day DFE is recommended. 81 The WHO adopted the IOM’s recommendations for pregnant and<br />

lactating women. 21 Multiparous pregnancies may require more folate but there is no established DRI for women<br />

carrying more than one fetus. 81<br />

Vitamin B12<br />

Vitamin B12 is necessary for healthy nerve and red blood cells and for the production of nucleic acids. 81 Vitamin B12 is<br />

found naturally only in animal foods. Vegans and others who consume few or no animal foods and insufficient vitamin<br />

B12 fortified foods may be at risk of vitamin B12 deficiency. 81 The IOM established recommended intakes for vitamin<br />

B12 during pregnancy at 2.6 µg and 2.8 µg during lactation. 81 The WHO adopted the IOM’s recommendations for<br />

pregnant and lactating women. 21<br />

Maternal vitamin B12 deficiency can result in deficiency in the nursing infant within months after birth. Infantile vitamin<br />

B12 deficiency may cause lasting neurodisability. 91 Women at risk for vitamin B12 deficiency should include fortified<br />

foods such as breakfast cereals, soy and other plant-based beverages, nutrition bars, meat substitutes, and fortified<br />

brewer’s yeast in their eating plan, as well a vitamin B12 supplement to achieve the suggested amounts.<br />

Choline<br />

Choline is an organic compound that is usually grouped within the vitamin B complex. Choline is found in cell<br />

membrane lipids; in sphingomyelin, a component of the myelin sheath surrounding nerve fibers; and as part of the<br />

neurotransmitter acetylcholine, necessary for muscle control, memory, and other functions. Choline is also present in<br />

high concentrations in the liver. 81,92<br />

Adequate choline intake during early pregnancy is important as availability of dietary choline during early pregnancy<br />

may influence neural tube closure, independent of folate. 13,14,93 Experimental animals supplemented with choline (in<br />

15

utero or during the second week of life) experienced lifelong memory enhancement, which appeared to be a result of<br />

the development of the hippocampus (memory center) in the brain. 13<br />

The IOM’s recommendation for choline intake for ages is 19 to 50 is 425 mg/day; during pregnancy, the suggested<br />

intake is 450 mg/day; and during lactation, it is 550 mg/day. 81 The WHO does not establish recommended intakes<br />

for choline. Most women consume inadequate dietary choline. 94 Over-the-counter multivitamins and mineral<br />

supplements and prenatal prescription supplements typically lack adequate choline for women at all stages of life.<br />

Maternal choline requirements should be satisfi ed with choline-rich foods as part of balanced diet. Egg yolks, liver,<br />

meat, poultry, and seafood are particularly rich in choline. Choline is also found in lesser amounts in foods such as<br />

broccoli, peanuts and peanut butter, and milk. 95<br />

Vitamin A<br />

Vitamin A designates a group of compounds essential to growth, cellular differentiation and proliferation, vision,<br />

reproduction, and immunity. 20 Preformed vitamin A (retinoids) is found largely in animal foods, such as liver and<br />

fortifi ed milk, and in dietary supplements. The carotenoids (beta-carotene, alpha-carotene, and beta-cryptoxanthin)<br />

can be converted to vitamin A by the body and are found in vegetables, fruits and oils. 20<br />

Adequate maternal vitamin A status is essential to fetal growth and development since vitamin A status in the fetus<br />

and neonate is dependent upon maternal status. Vitamin A is important for cell division, organ and skeletal growth<br />

and maturation, immune system maintenance, and visual development of the fetus. 17<br />

Maternal vitamin A defi ciency appears to be associated with decreased birth weight, preterm birth and low neonatal<br />

liver stores. 65 Worldwide, vitamin A defi ciency remains a concern among women. It is reported to affect an estimated<br />

19 million pregnant women with the highest prevalence of defi ciency occurring in Africa and Southeast Asia. Night<br />

blindness as a consequence of vitamin A defi ciency is reported to affect 9.8 million pregnant women worldwide. 17<br />

Maternal vitamin A defi ciency most commonly occurs in the third trimester due to the increase in blood volume<br />

and accelerated fetal development. In vitamin A defi cient areas, it may be diffi cult for pregnant women to meet<br />

the recommended intakes of vitamin A through diet alone. The WHO convened an expert group to establish<br />

guidelines on vitamin A supplementation during pregnancy. In areas where the prevalence of night blindness is 5%<br />

or higher in pregnant women and/or children 24-59 months of age, the WHO expert group recommends vitamin A<br />

supplementation during pregnancy for the prevention of night blindness. 17 If supplementation is recommended, betacarotene<br />

is not known to cause birth defects. 17<br />

Conversely, in areas where vitamin A defi ciency is not a public health problem, maternal vitamin A supplementation<br />

as retinoids may lead to toxicity. The WHO Expert Group advises that maternal vitamin A intakes of 10,000 IU daily<br />

or 25,000 IU weekly may lead to vitamin A toxicity for the mother and fetus. Symptoms of vitamin A toxicity include<br />

dizziness, nausea, vomiting, headaches, blurred vision, vertigo, skin exfoliation, reduced muscle coordination, weight<br />

loss and fatigue. 17 Excessive intake of preformed vitamin A during early pregnancy, a time when a woman may not<br />

realize that she has conceived, increases the risk of fetal malformations. 20,21 Maternal vitamin A supplementation<br />

is not recommended by the WHO for prevention of maternal morbidity and mortality unless vitamin A defi ciency<br />

presents a severe public health problem. 17 Dietary intake of vitamin A in the US appears to be adequate in women of<br />

childbearing age, 96 and there is no evidence of the need for routine supplementation which may prove harmful.<br />

The IOM’s recommendation for daily vitamin A intake for pregnant women ages 19 to 50 is 770 µg Retinol Activity<br />

Equivalents (RAE) or 2564 IU. 20 The Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) for vitamin A established by the IOM is 3,000<br />

µg RAE (10,000 IU) a day for 19 to 50 year-olds. 20 The WHO established levels of safe intake for vitamin A. The level<br />

of safe intake during pregnancy is 800 µg RAE a day while the level of safe intake during lactation is 850 µg RAE a<br />

day. 21 The WHO does not establish a tolerable upper intake level, however, it does refer to the WHO Expert Group<br />

recommendations as stated above. 21<br />

MATERNAL NUTRITION 16

Vitamin D<br />

Vitamin D’s principal role in the human body is to maintain serum calcium and phosphorus concentrations within the<br />

range that supports cellular processes, proper neuromuscular function, and bone ossification. 97 Vitamin D enhances<br />

calcium absorption in the gut and mobilizes calcium and phosphorus stores from bone to maintain a healthy blood<br />

calcium level. 97 Emerging evidence indicates that vitamin D has important roles in immunity and neurocognitive<br />

development in addition to its roles in calcium homeostasis and bone health. 15,16 Research conducted with female<br />

experimental animals suggests vitamin D plays a role in fertility. 98<br />

Vitamin D is formed in response to strong ultraviolet light (UV) from the sun that initiates the production of vitamin D<br />

in skin. Dietary and endogenously synthesized vitamin D are activated to 1,25-Dihydroxy-Vitamin D (1,25-OH-D) via<br />

two sequential hydroxylation reactions, first by the liver, and second by the kidneys. 97 Healthy humans with sufficient<br />

sunlight exposure can make the vitamin D they need to meet short-term needs, and store vitamin D in fat tissue for<br />

future use. Serum 25 Hydroxyvitamin D (25-OH-D) is an indicator of vitamin D status but optimal levels of 25-OH-D<br />

have not been established. 80<br />

Vitamin D insufficiency and deficiency in women of childbearing age is common throughout the world and is<br />

influenced by the woman’s lifestyle, degree of skin pigmentation, location, time of year, and sun exposure. 15 NHANES<br />

data from 2001-2006 indicated that 26% and 12% of women 19-30 years in the US were at risk for vitamin D<br />

inadequacy or deficiency, respectfully. When considering women who were pregnant or lactating, the risk for<br />

inadequacy was 21%, while the risk for deficiency was 7%. 99 Living at latitudes above 40° N or below 40° S, where<br />

there is relatively weak sunshine for about half a year, is a risk factor for vitamin D deficiency. The use of sunscreen<br />

with a sun protection factor of 8 and above significantly reduces cutaneous production of previtamin D3. 97 Women of<br />

color who live in northern climates may also be at particular risk for low vitamin D levels, because darker skin contains<br />

more melanin which blocks vitamin D production. 100 Overweight women, in particular, run a greater risk of midpregnancy<br />

vitamin D deficiency. 101<br />

Maternal vitamin D insufficiency or deficiency during pregnancy has been linked to adverse pregnancy outcomes<br />

including intrauterine growth restriction, pre-eclampsia, pre-term birth, and gestational diabetes, as well as recurrent<br />

wheeze, reduced bone mineral accrual, and increased rate of language impairment in infants. 16,65,102,103 In addition,<br />

maternal vitamin D deficiency during pregnancy has been associated with several disorders of calcium metabolism<br />

in the mother and infant (neonatal hypocalcemia and tetany, infant hypoplasia of tooth enamel, and maternal<br />

osteomalacia). Since vitamin D deficiency or insufficiency is thought to be common among pregnant women, a<br />

recent meta-analysis evaluated vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy. 104 The results show that vitamin D<br />

supplementation during pregnancy improves maternal vitamin D levels at term. Quality data on the clinical significance<br />

of this finding is too limited to draw conclusions. However, data suggest that pregnant women who consume vitamin<br />

D in supplement form are at lower risk for giving birth to babies who weigh below 2500 grams. 104<br />

The DRI for vitamin D before, during, and after pregnancy, including during lactation, is 600 IU/day for women ages<br />

19-50. 80 The WHO established a RNI for vitamin D at 5 mg/day (200 IU) during pregnancy and lactation. 21 According<br />

to The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, “When vitamin D deficiency is identified during<br />

pregnancy, most experts agree that 1,000 to 2,000 international units per day of vitamin D is safe.” 105 The Tolerable<br />

Upper Intake Level (UL) for vitamin D established by the IOM is 4,000 IU per day. 80<br />

Minerals<br />

Similar to vitamins, recommended intakes of several minerals increase during pregnancy and lactation. Figure 2<br />

compares recommended intakes of select minerals for non-pregnant women (19 to 30 years old) with those of<br />

pregnant or lactating women of the same age.<br />

17

FIGURE 2. DIFFERENCES IN MINERAL INTAkE RECOMMENDATIONS<br />

250%<br />

200%<br />

150%<br />

100%<br />

Calcium<br />

Chromium<br />

Copper<br />

Fluoride<br />

Iodine<br />

Iron<br />

Magnesium<br />

Manganese<br />

Molybdenum<br />

Phosphorus<br />

Selenium<br />

Zinc<br />

50%<br />

0%<br />

Pregnancy, 19-30 years<br />

Lactation, 19-30 years<br />

Potassium<br />

Sodium<br />

Chloride<br />

100% represents the DRI for nonpregnant<br />

and non-lactating women ages<br />

19-30 years. The bar graphs illustrate<br />

the percentage of the non-pregnant/nonlactating<br />

DRI recommended for pregnant<br />

and lactating women.<br />

Specifi c recommendations for pregnancy<br />

and lactation are provided in Table 9. It is<br />

important for pregnant women to consume<br />

adequate amounts of all essential minerals.<br />

Some minerals that deserve special<br />

attention during pregnancy and/or lactation<br />

are highlighted below.<br />

TAbLE 9. RECOMMENDED MINERAL INTAkES FOR WOMEN DURING PREGNANCY AND LACTATION,<br />

AGES 19 TO 50 YEARS 21,79,80<br />

Pregnancy<br />

Lactation<br />

Nutrient<br />

IOM WHO/FAO IOM WHO/FAO<br />

1200<br />

Calcium ac , mg 1000<br />

1000 1000<br />

3rd Trimester<br />

Chromium b , µg 30 - 45 -<br />

Copper a , µg 1000 - 1300 -<br />

Flouride b , mg 3 - 3 -<br />

Iodine ac , µg 220 200 290 200<br />

Iron ac , mg 27 Not specified 9 10-30<br />

Magnesium ac , mg 350-360 220 310-320 270<br />

Manganese b , mg 2 - 2.6 -<br />

Molybdenum a , µg 50 - 50 -<br />

Phosphorus a , mg 700 - 700 -<br />

Selenium a , µg 60 - 70 -<br />

Zinc a , mg 11 4.2-20 12 4.3-17.5<br />

Potassium b , g 4.7 - 5.1 -<br />

Sodium b , g 1.5 - 1.5 -<br />

Chloride b , g 2.3 - 2.3 -<br />

a Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA)<br />

b Adequate Intake (AI)<br />

c Recommended Nutrient Intake (RNI)<br />

Intakes are per day, unless otherwise noted.<br />

MATERNAL NUTRITION 18

Iron<br />

Iron is vital to the production of hemoglobin, (which is necessary for oxygen transport), and energy production,<br />

fetal immunity, and development of the central nervous system. 106 Iron deficiency affects more than 2 billion people<br />

globally, making it the most common nutrient deficiency in the world. Iron deficiency is more common in developing<br />

countries but continues to be a significant problem in developed countries despite near elimination of other forms<br />

of malnutrition. 107 An estimated eight million women of childbearing age in the US have iron-deficiency anemia, 2 and<br />

it is reasonable to expect that a large number of women are also iron-deficient. Low-income, less than 12 years of<br />

education and increased parity are all associated with a greater risk of iron deficiency and iron-deficiency anemia. 42,108<br />

The global prevalence of iron-deficiency anemia is estimated to be 47.4% in pregnant women. 18<br />

The recommended iron intakes established by the IOM increase from 18 mg/day to 27 mg/day during pregnancy<br />

for women ages 19 to 50 years 20 while the WHO has established different recommended intakes based on the<br />

bioavailability of dietary iron consumed. In developing countries, it is reasonable to use iron bioavailability levels of 5%<br />

and 10% translating into recommended nutrient intakes for lactating women of 30 and 15 mg/day respectively. In<br />

developed countries consuming a more Western diet, it is more appropriate to use bioavailability levels of 12% and<br />

15%, translating into recommended nutrient intakes for lactating women of 12.5 and 10 mg/day of iron, respectively.<br />

The WHO establishes no recommended nutrient intakes for iron in pregnant women because the iron balance in the<br />

diet depends on amounts of stored iron in addition to the bioavailability of dietary iron. 21<br />

Iron stores at the time of conception are a strong indicator of risk for iron-deficiency anemia later in pregnancy. 42<br />

Serum ferritin levels are a measure of stored iron in the body and can be used with a hematocrit to confirm irondeficiency<br />

anemia when there is no evidence of inflammation 108 before and during pregnancy. Iron-deficiency anemia<br />

during pregnancy has been associated with an increased risk for preterm birth, low birth weight, and perinatal<br />

mortality. 109-111 However, results of recent studies on the effects of maternal iron status and supplementation during<br />

pregnancy on fetal growth have been inconsistent. In a recent review on iron supplementation and pregnancy<br />

outcome, studies starting supplementation in mid- or late pregnancy found an increase in maternal iron markers,<br />

but no effect on fetal growth with the exception of one study where high-dose supplementation showed a<br />

positive association with birth length (not with birth weight) in a low-income setting. However, in studies starting<br />

supplementation in early pregnancy, maternal iron status did not improve, but there was a beneficial effect on fetal<br />

growth. 112<br />

Iron absorption during pregnancy is determined by several factors including the amount and bioavailability of<br />

dietary iron as well as the changes in iron absorption that occur during pregnancy. Although there is an increase in<br />

iron absorption, it is difficult for the mother to consume enough dietary iron to meet her iron requirements during<br />

pregnancy. 21 The typical American diet provides inadequate iron to meet the recommendations for the pregnancy<br />

state. 113 In addition, the endogenous iron stores of women may be insufficient to provide for the increased iron<br />

demands of pregnancy. 65<br />

In the US, the CDC recommends that all pregnant women take 30 mg of supplemental elemental iron every day<br />

to prevent anemia 2 and 60 to 120 mg of elemental iron daily to treat anemia once it is diagnosed. 2,113 In the UK,<br />

prophylactic iron supplementation is not recommended for pregnant women. However, pregnant women are<br />

monitored throughout pregnancy for iron-deficiency anemia and recommendations for supplementation based on iron<br />

status tests are established. 107 There is some concern that such prophylactic iron supplementation in women without<br />

anemia or iron-deficiency anemia may increase the risk of pregnancy complications. 42 However, iron supplementation<br />

during pregnancy has merit, as a large proportion of women have difficulty maintaining iron stores during pregnancy<br />

and are at risk for anemia. 113 The WHO recommends that pregnant women be supplemented with 60 mg iron in<br />

conjunction with 400 µg of folic acid daily. 18<br />

19

Calcium<br />

Calcium has structural and metabolic functions. The skeleton and teeth serve as reservoirs for about 99% of the<br />

body’s calcium; the remainder is found in blood, extracellular fl uid, muscle, and other tissues, where it plays a role in<br />

vascular contraction and vasodilation, muscle contraction, and nerve transmission. 97<br />

The recommended intake established by the IOM for calcium in pregnant and lactating women ages 19 to 50 is<br />

1,000 mg/day, 80 which does not represent an increase from the non-pregnant state. The recommended intake for<br />

calcium established by WHO for pregnant and lactating women is also 1000 mg/day, but increases to1200 mg/day<br />

during the last trimester of pregnancy. 21<br />

During pregnancy, adaptive maternal responses to fetal calcium needs include an enhanced effi ciency in absorption.<br />

Many women in their childbearing years do not consume adequate calcium. Multivitamins, including prescription<br />

and over-the-counter prenatal supplements, typically lack enough calcium to meet a woman’s daily needs. Women<br />

who cannot satisfy their calcium needs through food should take separate supplements. The UL for calcium<br />

established by the IOM is 2,500 mg/day. 80 The WHO establishes an upper limit on calcium intake of 3,000 mg/day. 21<br />

The WHO studied the effects of calcium supplementation on pre-eclampsia in pregnant women with low calcium<br />

intake. Calcium supplementation did not prevent preeclampsia, however it did reduce the severity, maternal<br />

morbidity, and neonatal mortality. 114 In 2011, the WHO published 23 recommendations for the prevention and<br />

treatment of pre-eclampsia. 39 The WHO guidelines recommend calcium supplementation (1.5 to 2.0 g elemental<br />

calcium per day) for pregnant women residing in areas where dietary calcium intake is low to help prevent preeclampsia.<br />

Zinc<br />

Zinc performs many functions and is a part of every cell in the body. Zinc is essential for growth and development,<br />

as well as reproduction and immunity. 20 The primary function of zinc is to promote cell reproduction and tissue<br />

growth and repair. It serves as a part of more than 70 enzymes including alcohol dehydrogenase, alkaline<br />

phosphatase, and ribonucleic acid (RNA) polymerases. Zinc also provides a structural function for copper-zinc<br />

superoxide dismutase. 115<br />

Because zinc plays a critical role in embryogenesis and fetal growth, as well as being secreted in breast milk, the<br />

body’s need for zinc is greater during pregnancy and lactation. 116 The recommended intakes for zinc established by<br />

the IOM for women ages 19 to 50 during pregnancy and lactation are 11 and 12 mg/day respectively. 20<br />

The WHO considered the bioavailability of zinc in food sources consumed when establishing recommendations. 21<br />

The bioavailability of zinc varies widely depending on a number of factors. Some zinc is more bioavailable from<br />

foods for absorption. Substances that can decrease zinc bioavailability include iron, calcium, phosphorus, amount<br />

and type of protein, phytates and fi ber. 117<br />

In addition to bioavailability, the WHO considers the variable needs during each trimester of pregnancy and stage of<br />

lactation by establishing different recommended zinc intakes for each. The recommended nutrient intakes for zinc<br />

during pregnancy and lactation can be found in Table 10.<br />

MATERNAL NUTRITION 20

Table 10. WHO Recommended Nutrient Intakes for Zinc during Pregnancy<br />

and Lactation 21<br />

Group<br />

High bioavailability<br />

(mg/day)<br />

Moderate<br />

bioavailability<br />

(mg/day)<br />

Low bioavailability<br />

(mg/day)<br />

Pregnancy<br />

First trimester 3.4 5.5 11<br />

Second trimester 4.2 7 14<br />

Third trimester 6 10 20<br />

Lactation<br />

0 to 3 months 5.8 9.5 19<br />

3 to 6 months 5.3 8.8 17.5<br />

6 to 12 months 4.3 7.2 14.4<br />

Iodine<br />

Iodine, a mineral often added to table salt, is a critical component of thyroid hormones. Thyroid hormones regulate<br />

many key metabolic processes and are particularly important for myelination of the central nervous system during<br />

fetal and early prenatal development. 20 Iodine deficiency from the fetal stage to about 3 months after birth leads to<br />

irreversible alterations in brain function. 19 The World Health Organization stated, “iodine deficiency is the greatest<br />

cause of preventable brain damage in childhood…” 19 Iodine deficiency in mothers also increases the risk of infant<br />

mortality, miscarriage and stillbirth. 118<br />

Iodine intakes vary around the world and within countries. Iodine content of foods is affected by iodine content of soil.<br />

Snow, heavy rainfall, and water can leach iodine from the soil lowering iodine content of crops grown in that soil. 19<br />

Many countries add iodine to table salt as an inexpensive yet effective way to increase iodine intakes. 19 According<br />

to the IOM, “Most foods provide 3 to 75 mg iodine per serving.” 20 Processed foods may contain significant amounts<br />

of iodine if iodized salt or other ingredients containing iodide are added (i.e. calcium iodate, potassium iodate,<br />

potassium iodide, cuprous iodide). 20 Food manufacturers, however, may use salt without added iodide, so it is<br />

important to read ingredient labels.<br />

The recommended intakes established by the IOM for iodine by pregnant and lactating women ages 19 to 50 are<br />