MOVIETONE NEW8 . - Parallax View Annex

MOVIETONE NEW8 . - Parallax View Annex

MOVIETONE NEW8 . - Parallax View Annex

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

~-~-~--~----------------------<br />

<strong>MOVIETONE</strong> <strong>NEW8</strong> .<br />

~ ~ ~<br />

~~~~~~~~======~===~75c . ~<br />

~( ='SS=UE=NU=MB=ER=48======S=EATT=L=E P=RIC~E SIOO_ELSEWHERE)<br />

B PIX, FILM. NOIR, ETC.<br />

HOWARD D ULM.ER D M.INNELLI<br />

_____(.~=_------.... aB_~~-=E!\-=-=-rr.::...=.LE=----=r-=-=IL=-=-M _~=-=O=-=C=-.:::.I=...:::ET.-::::...-Y ) )

I ' "r' \<br />

sj<br />

MOVIt~TONt: NEW6<br />

No. 48: February 29, 1976<br />

EDITOR<br />

Richard T. Jameson<br />

BUSINESS MANAGER<br />

Kathleen Murphy<br />

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS<br />

Robert C. Cumbow, R C Dale,<br />

Ken Eisler, Rick Hermann,<br />

Peter Hogue, Kathleen Murphy,<br />

Jon Purdy, David Willingham<br />

PRODUCTION ASSISTANTS<br />

Ken Eisler, Judy Hennes,<br />

Judy Rieben<br />

ASSEMBLY and MAILING<br />

Carol D. Boyd<br />

Entire contents © copyright by<br />

The Seattle Film Society<br />

5236 18th Avenue N.E.<br />

Seattle, Washington 98105<br />

(Telephone [206] 329-3119).<br />

All rights revert to authors<br />

upon publication.<br />

See inside back cover for<br />

information concerning<br />

subscriptions, contributions,<br />

advertiSing, etc.<br />

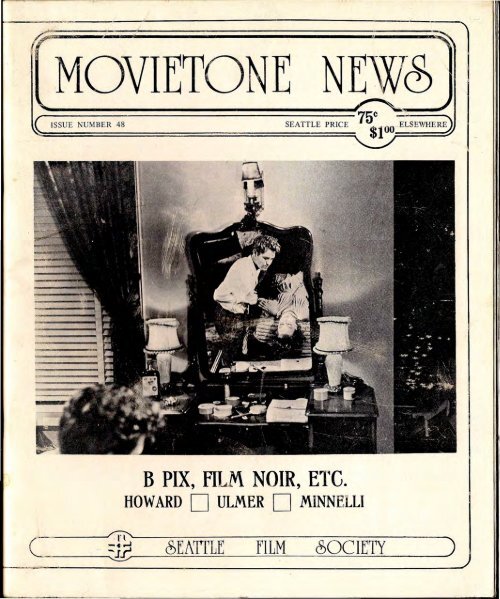

COVER: "The ultimate B movie"-<br />

Edgar G. Ulmer's "Detour"<br />

(photo Museum of Modern Art<br />

Film Stills Archive)<br />

c o N T E N T<br />

Back Door to Personal Expression<br />

The blessings of B-dom. William K. Howard's<br />

Back Door to Heaven, appreciated<br />

By James Damico<br />

Tracking Shot<br />

D.O.A. and the Notion of Noir<br />

Journey to the end of night<br />

By Richard Dorfman<br />

Closing Down the Open Road:<br />

Detour<br />

Life am ong the process screens, savored<br />

By David Coursen<br />

Letters<br />

In Black & White<br />

s 03<br />

o 10<br />

o 11<br />

o 16<br />

o 19<br />

o 20<br />

"B" Movies and Kings of the Bs, reviewed<br />

~ By Peter Hogue<br />

\The Birth of the Talkies, reviewed<br />

\ By Claudia Gorbman<br />

Touch of Evil: 0 23<br />

Removing the Evidence<br />

Unretoucbing an important article<br />

You Only Live Once 0 24<br />

"The American Dream" for UW LecCon<br />

A Piece of The Cobweb 0 27<br />

A note on suggestive mise-en-scene<br />

By Dana Benelli<br />

Quickies 0 30<br />

Barr)' Lyndon (2), The Magic Flute, Hearts of the World,<br />

One Flew over the Cuckoo's Nest, Between Friends,<br />

The Man Who Would Be King; Take It like a Man, Madam<br />

SEATTLE FILM SOCIETY BOARD OF DIRECTORS, 1975-76<br />

R C Dale, Diane Dambacher, Ron Green, Judy Hennes (Secretary),<br />

Rick Hermann (PreSident), Richard T. Jameson (Program Director),<br />

Doug King (Vice President) , Lindsay Michimoto (Treasurer), Ray Pierre,<br />

Veleda Tritremmel Pierre, Jon Purdy, Kitty Reeves, Margo Reich, Mike Richard, Curt Stucki<br />

ALTERNATES: Martha Dambacher, Sharon Green, Mike Sharp

[I]@\'!l@[J' [ID@0®[J'@ ~[J'@~@ITilfr@~ 000 ofr~ ®[J'0®000®~\1<br />

®®0iJ0 ~~ffi~ffi \Y]ffi[f@o®oo ~<br />

~OO~lJ~ ~&~@~@<br />

lliDLl®~~® ~ ® ~ ~ [illlJ®~U®~~o®®®·<br />

[ill ® mv® 00 ~ ill 00 rnJ@ ~<br />

rnrnw @[p~rn~rnw § lYoorn rnill~rn~rnw<br />

[K'i]®[J'lilfr[li)®oo ~O®oo® ®®®®rno~®ooorno@oofr [IDoo<br />

woo@@ ~®[fOOffi[f<br />

rn ~DOiJOD @~~[][][f~®OOll ~ru[f®[ID W<br />

rn~®@~@~ fA\Oll~ofr®[J'OOllrno\1®fro [K'i]1il[J'[k)9~\1<br />

~~~@ ~®fr[li) (fJ\'!l@o ~o<br />

@~@ ® ~ o®® = ®~[fi}ffi[l'® ®~L®®<br />

®®[l'ffi ~®[][] ~[fi}®ffilffi ~~®c~ ~ ~ ® ~®[l' ~[][][l'~[fi}ffi[l' Offil~®[l'[ffi®~O®ffil~ 0 0 0<br />

lY 00 rn @ rnilllYlY ~ rn I<br />

~~~~ @®©~rnlYW<br />

®~ ~G)[l'fr ®0 ofr~ ®®oofroooOllooo®<br />

®®ITO\l~®O®oo fr®=~®[J'@ 1!JfJ@ ~®OO<br />

ofr~=[J'Oll~@ fr[li)@ 1!JfJ®[J'~~\1<br />

~~®oo~ fr® OITO\l~[J'O~®ITilOO®Oll0®[J'<br />

~V~ [ID®OIJIT~<br />

®il lYffiOO~®OOO® OiJO®~OOffi@@~<br />

'I ,I

DOKTOR MABUSE DER SPIELER<br />

(Dr. Mabuse the Gambler)<br />

I - Der grosse Spieler<br />

II -Inferno<br />

Germany, 1922<br />

Directed by Fritz Lang<br />

Scenario:<br />

Lang and Thea von Harbou;<br />

based on a character created by Norbert Jacques<br />

Cinematography: Carl Hoffmann<br />

Art direction: Otto Hunte, Stahl-Urach<br />

Ullstein-Uco Film-Decla-Bioscop-Ufa<br />

Cast<br />

Dr. Mabuse Rudolf Klein-Rogge<br />

Yon Wenck Bernhard Goetzke<br />

Countess Told Gertrude Welcker<br />

Count Told , Alfred Abel<br />

~~a~r?~~~.~~~..::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::.~~~s~;ref~r~i~~~~<br />

Edgar Hull Paul Richter<br />

Chauffeur Hans Adalbert von Schlettow<br />

Pesch .•............................................................................................................ Georg John<br />

Fine Grete Berger<br />

Karstein Julius Falkenstein<br />

Told's servant Karl Platen<br />

and<br />

Lydia Potechina, Anita Berber, Paul Biensfeldt, Karl Huszar,<br />

Edgar Pauly, Lil Dagover, Julius Hermann, Adele Sandroch, Max Adalbert,<br />

Hans J. Junkermann, Auguste Prasch-Grevenberg, Julie Brandt, Gustave Botz,<br />

Alfred Klein, Erich Pabst, Hans Sternberg, Olf Storm,<br />

Erich Welter, Heinrich Gotho, Wily Schmidt-Gentner<br />

Dr. Mabuse made his bow, via this two-part film, early in Fritz Lang's career, but he was<br />

to reappear often, whether in his own name or that of some other criminal mastermind<br />

(Adolf Hitler, for example, during the war years) or, indeed, as the abstract but<br />

absolutely felt presence of Fate. The Seattle Film Society picked up on the good<br />

doctor's adventures in mid-career when we presented the 1932 Das Testament des<br />

Doktor Mabuse-in September 1974.lt really doesn't matter. The malignant, indomitable,<br />

almost supernatural spirit of Mabuse is timeless, as Lang's four-decades-long cinematic<br />

obsession with him gloriously testifies. We look forward to this long-delayed full-length<br />

showcasing of Mabuse's arrival (the film has been shown previously only in a mutilated<br />

single-feature compression, "The Fatal Passions, directed by Fritz Lange"). And by no<br />

means coincidentally-in regard to the present issue of <strong>MOVIETONE</strong> NEWS-Lang and<br />

Mabuse can share billing as the fathers of film noir.<br />

Piano accompaniment by Russell Warner

William K. Howard as a prosecuting attorney in his independent film Back Door to Heaven.<br />

BACI( DOOR<br />

TO PERSONAL EXPRESSION<br />

~~~~~~~~~~~3<br />

By James Damico<br />

I<br />

,<br />

I

BACK DOOR TO HEAVEN (1940)<br />

Direction: William K. Howard. Screenplay: John Bright and Robert Tasker, after a story by Howard.<br />

Cinematography: Hal Mohr. Art direction: Gordon Wiles. Editing: Jack Murray. Production: Howard;<br />

associate: Johnnie Walker. Odessco Productions; release by Paramount. (81 minutes)<br />

The players: Wallace Ford, Aline MacMahon, Jimmy Lydon, Stuart Erwin, Patricia Ellis, Van Heflin,<br />

Georgette Harvey, William Harrigan, and (unbilled) William K. Howard.<br />

B films are not so much maligned as misunderstood.<br />

The designation, often loosely applied to any film<br />

employing unknown or fading actors which is obviously<br />

inartistic and inept, properly denotes not an<br />

aesthetic classification but an economic one. Moreover,<br />

with some few exceptions, its use should be<br />

confined to those 19 30s-5Os American films whose<br />

budgets were rigidly held to a predetermined low<br />

level (varying with the producing organization and<br />

the changing economy) and which were intended<br />

primarily for pre-sold markets (to serve as conveniences<br />

for theatre owners and generally leased to<br />

them by fixed-fee rather than percentage-of-the-gross<br />

arrangement).<br />

Perhaps most neglected and misjudged about B<br />

films is their variousness, for it is somehow difficult<br />

to accept the idea that such an unassuming classification<br />

can encompass as many examples of genres and<br />

gradations of artistic quality as larger budget categories.<br />

What this view overlooks, however, is that<br />

while the limitations of the B film may have sapped<br />

or totally failed to engage the creative energies of<br />

some filmmakers, others found that not having stars<br />

and lavish budgets resulted in,. among other<br />

effects, the salutary "benign neglect" of studio<br />

superiors. Since markets were assured and fee arrangements<br />

only allowed for a limited profit, studio<br />

executives were inclined-as long as budgets were not<br />

exceeded-to pay little attention to the making of<br />

these films. This, for certain creators, provided just<br />

the leeway and impetus needed to permit a personal<br />

expression not always possible in bigger films which<br />

carried the weight of star reputations and financial<br />

success or ruin riding on the outcome of each day's<br />

shooting, and which therefore almost demanded<br />

continual studio supervision and interference. Consequently,<br />

and perhaps surprisingly, it is often easier<br />

to find a truly personal statement among B films than<br />

among their more expensive counterparts.<br />

A good and completely neglected example of this<br />

phenomenon is William K. Howard's Back Door to<br />

Heaven (1939). Though one of the rarer independent<br />

Bs and with a budget somewhat higher than the<br />

average, it is nonetheless a particularly informative<br />

illustration of how the B film could, with care and<br />

attention, serve as a supple and ready vehicle of<br />

self-expression.<br />

4<br />

Howard had a curious career. Today, when he is<br />

remembered at all, he is thought of as one of a long<br />

line of slick, commercial Hollywood directors. In the<br />

late Twenties and into the Thirties, however, he was<br />

considered a stylistic realist, a bright American<br />

artistic hope, a Very Big Man on the Hollywood<br />

Campus, and worthy of being mentioned in the same<br />

breath as such contemporary notables as Stroheim,<br />

Sternberg and Vidor. Indeed, while respectfully noting<br />

his $3500-a-week salary, a fan magazine (Motion<br />

Picture Classics of July 1928) called him an "idol,"<br />

"more discussed than Von Stroheim." On the<br />

strength of his most critically-acclaimed work, White<br />

Gold (1927), judged by some to be one of the<br />

highpoints of the late American silent cinema, he was<br />

rated a challenger to "the Germans"-rare praise at<br />

the time.<br />

Although he failed to live up to such inflated<br />

appraisals, he made in addition to White Gold a<br />

number of very provocative films, including Transatlantic<br />

and Surrender (both 1931), The Trial of<br />

Vivienne Ware (1932), Mary Burns-Fugitive (1935),<br />

and, from Preston Sturges' script, the muchremarked-upon<br />

The Power and the Glory (1933),<br />

often regarded as a prototype for Citizen Kane. In<br />

1937, still a top director, with a big-budget Paramount<br />

comedy just behind him, ThePrincess Comes<br />

Across, Howard went to England to direct a comparatively<br />

lavish costumer, Fire over England. Staying on;<br />

he became involved in a pair of low-budgeters. Upon<br />

his return to the U.S. his career took a sudden,<br />

unexpected, and permanent nosedive. Possibly he was<br />

the object of a studio boycott resulting from his own<br />

halting of production on Princess until Paramount<br />

withdrew the supervisor Howard had ordered off the<br />

set for undue interference (in what was the first<br />

invocation of a newly-gained power under Screen<br />

Directors' Guild policies). But what may have been an<br />

equal part of the problem was Howard's determination<br />

to do as his next project the very uncommercial<br />

Back Door to Heaven.<br />

The original story, which the director had written<br />

himself during his stay in England, was an intensely<br />

personal one. Set in Howard's hometown of St.<br />

Mary's, Ohio, it had been inspired by the lives of his<br />

schoolmates, one of whom had grown up to become a<br />

member of the Dillinger gang. Having killed a sheriff

and been sentenced to die, the friend was gunned<br />

down trying to escape from the death house. Howard<br />

had obviously brooded over these events and their<br />

setting for years. An interview in The Film Spectator<br />

of November 8, 1930, recounts: "A visit to his home<br />

town several years ago gave him pictures of age and<br />

decrepitude he hasn't been able to .shake out of his<br />

mind to this day." He was, however, unable to<br />

interest a major studio in his. story. It was only<br />

through the efforts of his friend and former film star,<br />

Johnnie Walker (whom he had directed in earlier<br />

days), that backing by a new independent company,<br />

Odessco Productions, and distribution by Paramount<br />

(contingent upon seeing the final print) was secured,<br />

and the film was made as Howard had envisioned<br />

it-in perhaps the only way such a highly subjective<br />

and commercially risky work could be-as a relatively<br />

low-budget B.<br />

At the time of its release, Back Door gained some<br />

unusual notice-before it sank into obscurity-by<br />

virtue of being the second feature shot at the<br />

once-more reactivated Paramount Astoria (Long<br />

Island) studios, rechristened for the occasion the<br />

Eastern Services Studios. This was good enough to<br />

garner the film reviews in Time and Newsweek it<br />

might otherwise have not received. But the blessing<br />

was double-edged, for Time (May 1, 1939) criticized<br />

the work as "an awkward attempt to crash the back<br />

door of the cinema industry" and characteristically<br />

referred to the dubbing of the director by his friends<br />

as "Noel Howard" for his multifaceted efforts in<br />

directing, writing the original story, producing and<br />

acting (in a small part as a prosecuting attorney), as<br />

"no compliment to England's Noel Coward."<br />

Apparently Howard's omnipresence was also part<br />

of what infuriated Frank S. Nugent, who in The New<br />

York Times of April 20, 1939, railed at Back Door as<br />

"emaciated," "a lulu," "banal, outrageous and maladroit,"<br />

"this nosegay" and "the most arrant poppycock,"<br />

before making one of two specific charges<br />

against it: "Mr. Howard has let his cameras freeze, has<br />

reduced his narrative to a series of static dialogue<br />

frames and has mistaken incoherence for impressionism."<br />

Putting aside the prickly question of how a film<br />

can be simultaneously banal and outrageous-and<br />

though it's not difficult to find fault with Back<br />

Door-the film can't fairly be dismissed as incoherent.<br />

It tends in fact to be overdetermined, reflecting its<br />

maker's insistence on his grim view of life. And it was<br />

probably to this vision that Nugent in reality objected,<br />

and not to the director's handling of it. Such a<br />

conclusion is supported by his second specific charge,<br />

that the film was "predicated on the conception of<br />

the law as an instrument of persecution and governed<br />

by an almost sophomoric fatalism." But this reading<br />

too is not borne out by the work, which holds the<br />

law and its agents no more guilry than any institution<br />

or person for the inevitable extinguishment of human<br />

aspirations. Morever, there is no bitterness in this<br />

view, merely acceptance of the unavoidable pain of<br />

existence. And while this is assuredly fatalistic, it is<br />

not notably of the sophomoric stripe, whose characteristic<br />

is to accuse everything and everyone for life's<br />

miseries.<br />

Yet even this cranky and hyperbolic criticism<br />

attests to the quality of the film that is most apparent<br />

and arresting: its personal stamp. If anyone is to<br />

blame for Back Door, Nugent suggests, it is Howard<br />

and the peculiarities of his life-view. True enough; but<br />

though his conception may, for whatever reasons, be<br />

misinterpreted or rejected, its distinctiveness is<br />

undeniable.<br />

It was a distinctiveness recognized and more<br />

sympathetically responded to by other observers.<br />

Though having reservations about the "sometimes<br />

implausible script," Newsweek (April 24, 1939)<br />

praised Back Door as "an unusual and interesting<br />

film, staged with grim and eloquent sincerity." And<br />

Philip T. Hartung of Commonweal found its fatalism<br />

particularly moving:<br />

This film, made on a small budget for serious<br />

minded adults, reaches a new high point in<br />

hopelessness and helplessness. Unfortunately<br />

too many loose ends keep you asking why and<br />

how. But it has the kind of an unadorned<br />

realistic story that in real life frequently does<br />

make you ask why and how.. .. This is all<br />

pretty somber, but with production, direction<br />

and original story by William K. Howard, it has<br />

unity, startling quietness and many fine touches.<br />

(May 5,1939)<br />

The unity is of course the result of the cohesiveness<br />

and consistency of the filmmaker's viewpoint-a<br />

quality not always easy to find in the more elaborate<br />

films of the time. What is even<br />

more pertinent, however, is that the specifics of<br />

Howard's outlook could never have formed part of<br />

bigger budget films simply because they comprise a<br />

concept of life that is undramatically, unpretentiously<br />

and irremediably pessimistic. No studio would have<br />

chanced a large sum of money on such uncommercial<br />

material, no stars would have risked their images on<br />

such un theatrically downbeat parts, and very probably<br />

no large section of the general moviegoing<br />

audience, weaned on far less unremitting fare, would<br />

5

have sat still for it. Only in the relative obscurity and<br />

security of the B world could such a vision have<br />

found cinematic expression.<br />

A summary of the plot, excerpted from Newsweek's<br />

review, gives some indication of the film's<br />

nature:<br />

Frankie Rogers, born on the wrong side of<br />

[a small town's) railroad tracks ... and his<br />

classmates prepare for graduation day under the<br />

gentle direction of their beloved teacher, Miss<br />

Williams. In order to contribute his share to the<br />

graduation exercises, Frankie breaks into a<br />

hardware shop and steals a harmonica [and<br />

$8.70). And instead of high school, Frankie<br />

goes to a reformatory.<br />

Characterized by Wallace Ford with subtle<br />

intensity, the adult Frankie is first seen in a<br />

state penitentiary. With his release he determines<br />

to go straight, but the cards ... are<br />

stacked against him. [The rest depicts) Frankie's<br />

subsequent frustration-his innocent involvement<br />

in a holdup and murder, his break<br />

from a prison death house to return to [his<br />

hometown) and his class reunion for a last<br />

glimpse of his schoolmates before inevitable<br />

capture and death ....<br />

At 35 years' remove, it is possibly difficult to<br />

differentiate this narrative from dozens of other<br />

ostensibly similar ones that served as the basis for<br />

contemporary major and minor films. Yet, though<br />

they may not be readily apparent from a bare<br />

summary, the distinctions are real and significant.<br />

Countless films of the time utilized the plot device<br />

of the underprivileged kid started on a life of crime<br />

through no fault of his own. But it is Howard's sober<br />

view that gives Frankie-beyond his poor home<br />

environment, which is more than counterbalanced by<br />

a totally supportive one at school-little excuse for<br />

the theft of the harmonica and none at all for the<br />

additional theft at the same time of cash from the<br />

store's register. It is not, as it might have been in the<br />

Warners' "social protest" (read gangster) films of the<br />

period, his drunken father or a truly no-good friend<br />

whoreally steals the money, for which act the child is<br />

then blamed, causing his unjust imprisonment and his<br />

first step onto the treadmill of crime. Whatever has<br />

made Frankie what he is, he is guilty. As he says with<br />

unaffected and unpleading simplicity, "I took it."<br />

Nor does Howard allow Jimmy Lydon (who gives<br />

a remarkable performance as Frankie the boy) any of<br />

the stock emotional appeals that very often suffused<br />

the playing of children in similar films. As he does<br />

with all the actors, the director keeps Lydon under a<br />

restraint that is dignified, persuasive and occasionally<br />

eloquent. This is the "quietness" that Hartung found<br />

so "startling," and it is an approach that logically<br />

generates far more empathy for the child (and other<br />

characters) than the more usual Hollywood attitude<br />

toward such figures, which seems to have them<br />

alternately begging for or demanding sympathy.<br />

Another and allied feature of Howard's outlook<br />

apparent in the film's performances is its total lack of<br />

rancor. The truculence and resentment that inevitably<br />

accompany the stealing and the reformatory and<br />

prison stays of many similar characters played in their<br />

adult form, for example, by James Cagney have no<br />

part in Frankie's makeup. The boy is depicted from<br />

the outset as having a sad but mature understanding<br />

of the hardness of life, and his turn to crime and its<br />

subsequent punishment he sees simply as one more<br />

manifestation of the rigor of existence. Though the<br />

film is thoroughly sentimental, it does not calculatingly<br />

employ sentimentality as a device to win easy<br />

audience acceptance. Its creator is so convinced of<br />

the rightness of his sentimental/pessimistic life-view<br />

that he feels no need to make any special pleadings in<br />

its behalf or to trick or persuade his audience of its<br />

truth; it suffices for him simply to show it. This is a<br />

requisite of personal artistic expression much less<br />

likely to find its way through the labyrinth of the<br />

egotistical and commercial demands of big-budget<br />

films.<br />

Relatedly, Howard seems at various points in the<br />

film to evoke traditional cinematic conventions for<br />

the purpose of pointing up their falsities and rejecting<br />

them. Released from prison, Frankie takes two<br />

ex-con buddies back to his hometown, where he visits<br />

the only successful member of his grade-school class,<br />

the president of the local bank. Taking Frankie on a<br />

tour, the president ostentatiously and unwittingly<br />

discloses to him the secrets of the bank's safe and its<br />

radio-beam burglar alarm. Pointedly, Frankie asks<br />

him if the bank is insured, to which the president<br />

proudly responds that it is. Having no plot point<br />

whatever, the scene is clearly intended to raise the<br />

expectation-familiar from other films-of a bank<br />

stickup by the three ex-cons and the usual dramatic<br />

device by which a character like Frankie gets back at<br />

the town that sent him to jail. And when he steps<br />

outside, precisely on cue his buddies suggest that the<br />

bank would be an easy mark. Frankie, however,<br />

instantly quashes the idea. But the irony of his reason<br />

for abstaining-"This is my hometown"-is revealed<br />

by his response to a passing pedestrian's request for<br />

directions to the Chamber of Commerce: "I don't<br />

know. I'm a stranger here."<br />

Irony is a consistent feature of Back Door but it is<br />

never sardonic or-again to dispute Nugent-never

photos this page: Museum of Modern Art Film Stills Archive.<br />

easy. A sequence detailing the<br />

teacher's opening of gifts from her<br />

now-grown pupils, all of whom she<br />

believes are "successful", counterposes<br />

her description of their young<br />

talents with shots of their present<br />

real-life situations: the class speechmaker<br />

is shown as a struggling lawyer<br />

unable to pay his rent, the would-be<br />

violinist as a soda jerk, the budding<br />

artist as earning drinks by painting<br />

pinups over a bar, and the aspiring<br />

singer idly warbling the film's theme<br />

lament, "I Need a Friend," alone<br />

with only a pianist in a rundown<br />

cafe. Another song, "Hometown,"<br />

catalogues the joys of smalltown<br />

living and impels Frankie to return to<br />

his birthplace; but it is sung in a city<br />

style in a city dive by one of Frankie's<br />

ex-con buddies, who is a city boy<br />

with the most obvious of urban faces<br />

and manners. The touch here, however,<br />

as it is throughout the film, is<br />

distinctively gentle and low-key.<br />

This sure restraint and control<br />

culminates and achieves a homely<br />

eloquence in a scene in which<br />

Frankie returns to his boyhood<br />

home. It is undoubtedly one of the<br />

places where Nugent felt Howard let<br />

his camera "freeze" (though four or<br />

five setups are utilized) and reduced<br />

his narrative "to a series of static<br />

dialogue frames." This type of setpiece,<br />

however, had always been the<br />

basic structural unit of Howard's<br />

visual style. Though his range of<br />

features includes all manner of<br />

camera and editing stylistics (The<br />

Trial of Vivienne Ware, for example,<br />

is a delightful cornucopia of every<br />

possible visual and editing device to<br />

invoke speed-an orchestration of<br />

swish pans, flash cuts, tilts and constantly<br />

varying angles), and though<br />

he was a confessed admirer of Murnau<br />

and could move his camera with<br />

skill and alacrity (especially, as<br />

William K. Everson has pointed out<br />

to me, when he had a cinematographer<br />

such as James Wong Howe<br />

who favored a mobile camera), he<br />

seemed to reserve for his important<br />

7

narrative or most deeply-felt scenes carefully composed<br />

and relatively lengthy shots with nearly imperceptible<br />

camera movement, actor stability, and<br />

minimal interposed cuts. Even more essential to<br />

Howard's style was his penchant for chiaroscuro. The<br />

sharpest black-white contrasts seem to have represented<br />

for him the indissolubility of joy and darkness in<br />

life, and their continual juxtaposition in shot after<br />

shot of film after film testifies to the director's<br />

philosophical duality (although it is clearly darkness<br />

which predominates in his compositions).<br />

All these : features are notably part of the<br />

aforementioned scene of Back Door in which Frankie<br />

returns to his childhood home to question the black<br />

family living there about his mother. And it is<br />

precisely in its so-called "static" quality, of which<br />

Nugent complained, that Howard's attitude and<br />

approach are distilled to their essence; for it is this<br />

quality which supports and at the same time reveals<br />

and becomes part of the filmmaker's concept of the<br />

somber, crushing, but inevitable and somehow dignifying<br />

burden of existence. -<br />

The characters-Frankie, Mrs. Hambleton and her<br />

two children-are set in position at the start of the<br />

scene and scarcely gesture during its several minutes'<br />

length. In an unstressed allusion to his own childhood'<br />

in the house, Frankie is placed next to the seated and<br />

Inexpressive boy of the family, at whom he occasionally<br />

glances while listening respectfully and attentively,<br />

but with a kind of intense distraction, to the<br />

mother as she talks about the fate of his parents. He<br />

finally addresses the boy directly to ask if the child is<br />

going to be a railroad porter like the relative whom<br />

the mother has held up as a success in life. The<br />

passive boy returns Frankie's neutral look and murmurs<br />

a noncommittal "Maybe," fusing as he does<br />

into a composite figure with the man across the years'<br />

difference in their ages, forming because of his color<br />

nearly the photographic negative of the boy Frankie<br />

visible in and indivisible from the man. It is a rich and<br />

reverberatory understatement of the kind that in-<br />

forms the entire scene. When Mrs. Hambleton reports<br />

i to Frankie that they took his mother "away to<br />

Toleda. Is that the place where they carry crazy<br />

people?" Ford as Frankie replies, "Yeah, that's the<br />

place," in the same simple, straightforwardly accepting<br />

manner that characterizes Lydon's performance<br />

-and the entire cast's, for that matter-without<br />

resorting to a blink, a gulp or even a tremor of the<br />

lower lip. And when the chance to display a theatrical<br />

bitterness presents itself with the black woman's<br />

attempt to comfort him that his father "died with the<br />

most loveliest .smile.on his face," his response-v'Was<br />

he plastered?"-is still muted and given with almost a<br />

flush of embarr.assment at being unable to contain,<br />

not his bitterness, but his anguish. Sentimental, to be<br />

sure, but sincere, authentic and without guile, subterfuge<br />

or appeal for effect.<br />

This distinctive' vision extends to the technical<br />

aspects of the film and also provides another instance<br />

of the widely, and sometimes wildly, varying nature<br />

of B films so often overlooked. Though there are<br />

literally hundreds of Bs that appear to have been<br />

made by Brownies with Brownies in front of High<br />

School Drama Society settings, there are many, like<br />

Back Door, that reflect the most precise attention to<br />

aesthetic and technical matters. The finished film<br />

clearly displays Howard's (and Hal Mohr's) careful<br />

compositions and lighting setups; the director's (and<br />

the art director's) stress on the importance of<br />

appropriate and veracious, though not necessarily<br />

expensive, sets; and the most detailed consideration<br />

in casting, exemplified by the exact physical pairing<br />

of child with adult actors-not just Lydon with Ford,<br />

but also with the look-alike youngsters who are<br />

matched to the unusual appearances of Patricia Ellis<br />

and Van Heflin. It is a categoric demonstration of the<br />

range of possibilities and the freedom of choice<br />

inherent in the B system.<br />

Freedom is perhaps the most difficult concept for<br />

the general consciousness to reconcile with the<br />

B film, for the misapprehension of the classification<br />

has centered on two of its comparatively few restrictions:<br />

the lack of star actors and the limited budget.<br />

There were others, of course, and serious ones-the<br />

small salaries, for example, most often meant besides<br />

poor acting, even poorer direction and scripts. But<br />

what should be realized is that this process of<br />

minimization did not operate unfailingly, and that<br />

when a filmmaker of even a limited talent and vision<br />

apprehended and responded to the possibilities of the<br />

category, it provided to some extent a less encumbered<br />

outlet for his expression than 'the nominally<br />

grander categories of film.•<br />

James Damico is a play- and TV-writer who resides in<br />

New York City. He has previously published film<br />

criticism in The Journal of Popular Film.

The Seattle Film Society is proud to present<br />

A TRIBUTE TO<br />

JEAN RENOIR<br />

featuring 5 of his least-seen films:<br />

7:30 p.m. Thursday, March 11 - 2 French films<br />

MADAME BOVARY<br />

1934 - 1st Northwest showing<br />

ELENA ET LES HOMMES<br />

1956 - in color, with Ingrid Bergman<br />

7:30 & 9:30 Friday, March 12 - the legendary film of Indian life<br />

THE RIVER<br />

By special arrangement with producer Kenneth McEldowney,<br />

we are showing a rare 35mm Technicolor print<br />

7:30 Saturday, March 13 - 2 American Renoirs<br />

SWAMPWATER<br />

1941 - Walter Brennan<br />

THE SOUTHERNER<br />

1945 - Zachary Scott & Betty Field<br />

All shows in 130 Kane Hall, University of Washington<br />

Admission Thurs. & Sat.: SFS $1.00, UW student $1.50, others $2.00<br />

Admission for THE RIVER: SFS $1.50, UW student $2.00, others $2.50<br />

Phone 329-3119 for more information.

TRACKING SHOT<br />

The nominations for the 1975 Academy of Motion Picture<br />

Arts and Sciences Awards have been announced, and the<br />

contenders in the leading categories are:<br />

Best Picture: Barry Lyndon, Dog Day A fternoon, Jaws,<br />

Nashville, One Flew 0 ver the Cuckoo's Nest.<br />

Best Director: Robert Altman, Nashville; Federico Fellini,<br />

Amarcord; Milos Forman, One Flew over the Cuckoo's Nest;<br />

Stanley Kubrick, Barry Lyndon; Sidney Lumet, Dog Day<br />

Afternoon.<br />

Best Actor: Walter Matthau, The Sunshine Boys; Jack<br />

Nicholson, One Flew over the Cuckoo's Nest; AI Pacino, Dog<br />

Day Afternoon; Maximilian Schell, Man in a Glass Booth;<br />

James Whitmore, Give 'Em Hell, Harry.<br />

Best Actress: Isabelle Adjani, The Story of Adele H.;<br />

Ann-Margret, Tommy; Louise Fletcher, One Flew over the<br />

Cuckoo's Nest; Glenda Jackson, Hedda; Carol Kane, Hester<br />

Street.<br />

Best Supporting Actor: George Burns, The Sunshine Boys;<br />

Brad Dourif, One Flew over the Cuckoo's Nest; Burgess<br />

Meredith, Day of the Locust; Chris Sarandon, Dog Day<br />

Afternoon; Jack Warden, Shampoo.<br />

Best Supporting Actress: Ronee Blakley, Nash ville; Lee<br />

Grant, 'Shampoo; Sylvia Miles, Farewell My Lovely; Lily<br />

Tomlin, Nashville; Brenda Vaccaro, Jacqueline Susann 's Once<br />

Is Not Enough.<br />

Best Screenplay-Original: Ted Allan, Lies My Father Told<br />

Me; Federico Fellini and B. Zapponi,' Amarcord; Claude<br />

Lelouch and Pierre Uytterhoeven, And Now My Love; Frank<br />

Pierson, Dog Day Afternoon; Robert Towne and Warren<br />

Beatty, Shampoo.<br />

Best Screenplay-Adaptation: Lawrence Hauben and Bo<br />

Goldman, One Flew over the Cuckoo's Nest; John Huston<br />

and Gladys Hill, The Man Who Would Be King; Stanley<br />

Kubrick, Barry Lyndon; Dino Risi and Ruggero Maccari, The<br />

Scent of a Woman; Neil Simon, The Sunshine Boys.<br />

Cinematography: John Alcott, Barry Lyndon; Haskell Wexler<br />

and Bill Butler, One Flew over the Cuckoo's Nest; Conrad<br />

Hall, Day of the Locust; James Wong Howe, Funny Lady;<br />

Robert Surtees, The Hindenburg.<br />

Cuckoo's Nest leads the pack with nine nominations; Barry<br />

Lyndon has seven, Dog Day Afternoon six; The Man Who<br />

Would Be King and Shampoo each received four.<br />

The Awards themselves will be announced March 29.<br />

* * * * *<br />

Costarred with John Wayne in that new Don Siegel film, The<br />

Shootlst , is Lauren Bacall. Others in the cast include Ron<br />

Howard and "guest stars" James Stewart, Richard Boone,<br />

John Carradine, Yaphet Kotto, Harry Morgan and Sheree<br />

North.<br />

John Frankenheimer is now filming Black Sunday for<br />

producer Robert Evans. Ernest Lehman and Kenneth Ross<br />

have written the screenplay and the stars are Robert Shaw,<br />

Marthe Keller, Bruce Dern and Fritz Weaver.<br />

Can Mel Brooks shut up long enough for a Silent Movie?<br />

That's the title of his current project, to star himself plus<br />

Marty Feldman, Sid Caesar, Bernadette Peters and Dom<br />

DeLuise.<br />

Latest entry in the Sherlock Holmes sweepstakes is<br />

Sherlock Holmes in New York, now shooting at 20th<br />

Century- Fox under the supervision of John Cutts. Roger<br />

Moore stars, Patrick Macnee is Watson, and Moriarty is<br />

played by John (shades of Noah Cross!) Huston. Boris Sagal<br />

is directing the film (on leftover Hello, Dolly! sets), which is<br />

to prem iere on American TV and play theatrically in Europe.<br />

Oh yes, Irene Adler's part of the mix, in the form of<br />

Charlotte Rampling.<br />

Skipping is the new title of that Jack Lemmon - John<br />

Korty project The Phoenician and the Gypsy. Genevieve<br />

Bujold costars.<br />

A completer cast listing for the new English-language<br />

Claude Chabrol, The Twist: Bruce Dern, Ann-Margret, Sydne<br />

Rome (star of Roman Polanski's still-mostly-unseen What?),<br />

Stephane Audran, Maria Schell, Charles Aznavour, Tomas<br />

Milian, Gert Frobe, Jean-Pierre Cassel, Curt Jurgens.<br />

Paddy Chavefskv , having copped an Oscar for The<br />

Hospital, has written Network. Sidney Lumet is directing<br />

Faye Dunaway, William Holden, Peter Finch, Robert Duvall,<br />

and Darryl Hickman therein.<br />

Meanwhile, Irwin Allen, ever in an apocalyptic mood, is<br />

following The Poseidon Adventure and .The Towering Inferno<br />

with The Day the World Ended. Next act?<br />

Clint Eastwood has displaced/replaced Philip Kaufman as<br />

director of The Outlaw-Josey Wales ... starring Eastwood,<br />

natch. .<br />

Add Ray Milland and Dana Andrews to the folks already<br />

announced for The Last Tycoon.<br />

Milos Forman will direct the film version of Hair. One<br />

flew back to the cuckoo's nest?<br />

Elliott Gould is set to make his screen directorial debut<br />

with a film of Bernard Malamud's novel A New Life. Gould<br />

also stars.<br />

Look for two John Sturges films in the more or less near<br />

future-one new, one new-old. Sturges is preparing to direct<br />

Donald Sutherland and Michael Caine in The Eagle Has<br />

Landed. In the meantime, Chino, a film he made in Europe<br />

with Charles Bronson several years ago, is due in the States.<br />

Peter Fonda, Blythe Danner, Arthu r H ill and a<br />

re-transistorized Yul Brynner are in Futureworld.<br />

Aram Avakian, whose directorial career has been spotty<br />

but "interesting," reverts to his former task of film editor for<br />

The Next Man.<br />

The cast of a new World War II spectacular, A Bridge Too<br />

Far-in alphabetical order, of course: Dirk Bogarde, James<br />

Caan, Michael Caine, Sean Connery, Elliott Gould, Gene<br />

Hackman, Anthony Hopkins, Hardy Kruger, Laurence<br />

Olivier, Ryan O'Neal, Robert Redford, Maximilian Schell.<br />

(Don't let anyone tell you there are no more good roles for<br />

women.) Richard Attenborough directs, from a screenplay by<br />

William Goldman.<br />

Dirk Bogarde is also in Providence, a new English-language<br />

film by Alain Resnais. His costars: Ellen Burstyn, John<br />

Gielgud, David Warner.<br />

Two mucho macho directors are working on feature films<br />

in Germany now: Robert Aldrich, on Silo III, starring Burt<br />

Lancaster, Richard Widmark, Paul Winfield, Melvyn Douglas,<br />

Joseph Cotten, and Charles Durning; Sam Pe ckinpah, on<br />

Steiner, a James Coburn picture .•

1).C).ll.<br />

liNI) rl'lll~ NCtrl'ICtNCtl?NCtill<br />

BY IlI.~II1'lll) J).)lll~Ml'N

'I'IIE SEA'I"I'I.•I~I~II..M Sf)f~llrl'Y I)III~SI~N'I'S<br />

1~1~1' 'l'lJIIIN f.<br />

,J()SI~I)II II. I.•I~"TIS'<br />

)IY N1\)II~IS .IIJI .•11\ IIC)SS<br />

&<br />

1~1)(.llll f•• IJI.•)II~II'S<br />

I)I~'1'C)IJ II<br />

(U'l'HI~IJI..'I'IM1"I'I~II Mf)lTIIU")<br />

&<br />

1)1111 .•l{lllll .•S()N'S<br />

f)f) Ill'TI~11S'1'lll~I~'I'<br />

II I).)1. Sll'I'lJIII)l\ Y, Mllll(~11 2ft<br />

BLOEDEl.•AIJnl'l'f)RIIJM, S'I'. MAliK'S, 122f) I 0'1'11I~.<br />

SFS S1.00 - O'I'HERS 52.00<br />

PHONE 3%9-3119 FOR ADDITIONAL INFO.

cannot be distinguished from them. In -fact, one's<br />

sympathies are almost reversed as Bigelow becomes<br />

the bully, hounding people who only wish to be left<br />

alone. *<br />

The noir world is a state of nature. The police, the<br />

physical embodiment of the law, to whom Bigelow is<br />

telling the story in retrospect, are useless. It is<br />

Bigelow who discovers the crime, solves it and metes<br />

out justice. If, in the romantic view, the noir crusader<br />

is a knight-errant, he is also a fascist with no more<br />

respect for the law than those he opposes. Mike<br />

Hammer's success in Kiss Me Deadly is due largely to<br />

the fact that he plays the villains' game better than<br />

they do.<br />

The seemingly diverse strands of D. O.A. cohere in<br />

the person of its hero. It is Bigelow who brings<br />

together the connection between Majak and Halliday,<br />

how Halliday conned his partner Phillips into buying<br />

the stolen iridium so that it would be "clean" when it<br />

was resold. It is in Bigelow's mind, literally, that the<br />

whole story exists, for no one else knows it. Others<br />

can see part, but even those who have created the<br />

dilemma cannot see his part, while after they have<br />

played theirs he can see not only the inspiration at<br />

the beginning and the machinations in the middle,<br />

but also the end he will write.<br />

When Phillips takes the blame for stealing the<br />

iridium, Bigelow is the only one who can clear him<br />

because he has a record of the bill of sale, which he<br />

notarized, that will show whom Phillips bought it<br />

from. This is the reason Bigelow is poisoned. Halliday<br />

realizes Bigelow can prove to be his undoing and<br />

poisons him even though Bigelow cannot even recall<br />

the transaction. The implied irony is that if they had<br />

not killed him he would never have become involved<br />

and the crime would have gone undetected. As it is,<br />

Bigelow becomes-as the New York Times put it<br />

when the picture opened-"caught up in a web of<br />

circumstance that marks him for death."<br />

Once, Bigelow regrets his decision to hunt his<br />

murderers. There is a strange scene after Majak's<br />

hoods capture Bigelow in his hotel room. The phone<br />

rings. It is Pamela calling from the office. She is<br />

worried because he has not talked to her recently. In<br />

. fact, he has not told her of his imminent demise and<br />

has been very short with her in their previous<br />

conversations. While the two hoods flank him-one<br />

(Neville Brand) holding a gun to his head, the other<br />

the receiver to his ear-he talks to her, softly, as if the<br />

others weren't present. This would almost seem to be<br />

* D.O.A. does not predate the current yield of vigilante films<br />

so much as form part of the tradition, which reaches back to<br />

the frontier where a man was his own law.<br />

the case, for director Rudolph Mat~ holds the shot<br />

and the men remain in the same positions, completely<br />

stationary, as if they were statuary or had found<br />

themselves in front of the camera when they<br />

shouldn't be. After a while one forgets them and<br />

concentrates instead on Bigelow. What comes across<br />

is a scene of intimacy between lovers rather than one<br />

of danger. And the intimacy is genuine, for Bigelow<br />

tells her he loves and misses her, talking without<br />

interruption longer than would seem safe from the<br />

criminals' point of view, risking discovery as a<br />

consequence. That the shot of the three of them, held<br />

in medium closeup, is played for longer than it can be<br />

sustained does not detract from the film's strength<br />

but rather is part of it, contributing to the sense of<br />

general dislocation.<br />

Pamela Britton is protected from this seaminess by<br />

virtue of being a woman. As such, she is not only<br />

dependent on Bigelow but subordinate to him.<br />

Bigelow originally leaves her so that he can be alone<br />

and decide if he wants to marry her, if this is really it.<br />

She, of course, is sure. If the two of them marry she<br />

knows it will be something "wonderful." Here<br />

marriage is an ideal to aspire to, a creative union that<br />

serves as a substitute to any real artistic inclinations<br />

in the middle class. But Bigelow is not sure that it's<br />

right, and tells her that he's seen what can happen<br />

when two people begin to hate each other. It's always<br />

the woman who gets hurt worse, he assures her.<br />

The form of his meditation on matrimony is a last<br />

fling. He goes to San Francisco, where he knows no<br />

one, and eventually arrives at a bar, The Fisherman,<br />

where life is uninhibited-as opposed to the restricted<br />

existence he has been leading. Bigelow is in the<br />

process of picking up some woman' when he .is<br />

poisoned by a mysterious stranger who switches<br />

drinks on him. He is, in effect, punished for both his<br />

disloyalty to Pamela Britton and his interest in casual<br />

sex as opposed to marriage. t In fact the music from<br />

the bar is played again over the soundtrack when<br />

Bigelow corners Halliday and guns him down, to<br />

remind the audience of the true source of Bigelow's<br />

affliction. *<br />

Women in film noir are never seen to be active<br />

without the aid of a man. Often they are not active at<br />

all, like Britton. This is not to say that she is of no<br />

help to Bigelow in her own right; in fact, she is the<br />

t It is the opposite of the principle in Hitchcock's films<br />

where the woman is punished for her boldness and must go<br />

through some ordeal in order to be purified (viz. 'Tippi'<br />

Hedren in The Birds and Mamie, and Ingrid Bergman in<br />

Notorious .)<br />

* For this observation I am indebted to Gail Petersen.

one who finds the record of the bill of sale. It is just<br />

that she is tied to the switchboard at his office while<br />

he is playing the hero. When women are active in film<br />

noir, it is often in the role of temptress, hard and<br />

scheming, like Barbara Stanwyck in Double Indemnity,<br />

or a gun moll 0 n the perip hery of intrigue,<br />

exuding sexual availability like Maria Rakubian<br />

(Laurette Luez) here-which makes her "bad".<br />

Maria's foreignness is emblematic of her bad qualities,<br />

for it excludes her from the middle class, which is<br />

solely white in these films, and in which the greatest<br />

disgrace that can come to a woman is to be "fallen".<br />

The middle class is the repository of good in<br />

America and the bulwark against the grasping world<br />

which organized crime represents. It is caught at the<br />

crossroads between the puritanical values it espouses<br />

and the realities operative in the world it seeks to<br />

deny, a world in which everything is allowed because<br />

it is only in that way that anything can be gained.<br />

The middle-class man provides through his work and<br />

protects his family from any invasion from the<br />

outside. Yet at the same time he must be able to act<br />

in that world at times, if he has not actually pulled<br />

himself up from it in order to provide that<br />

protection. Film noir is the first to suggest that this<br />

defense is beginning to crumble.<br />

Bigelow finally tracks Halliday down as his killer.<br />

He returns to the empty building where Halliday has<br />

his office-a building whose vastness suggests the<br />

isolation and meanness of men-and stalks Halliday as<br />

he attempts to make good his escape. Running down<br />

the stairs, Halliday spies Bigelow and fires first, but<br />

Bigelow, at the top of the stairs, has the advantage in<br />

position (and righteousness, sure to improve his aim)<br />

and guns him down, emptying his revolver.<br />

The film ends in the police office where Bigelow,<br />

recounting his story, finishes just in time to drop<br />

dead in front of the calm eyes of his audience, the<br />

police. It is as if he had no life outside this adventure,<br />

living only to see it through. For his heroics have<br />

provided him with just that sense of adventure that<br />

was missing in his normal life. The film itself provides<br />

this vicariously for its audience. If Bigelow has seen it<br />

through to the end, he still cannot comprehend how<br />

he got involved in the beginning. It is an existential<br />

mystery, the imperious hand of an arbitrary order<br />

pressing down on him. "All I did was notarize a bill<br />

of sale," he says.II<br />

Richard Dorfman writes about film from Somewhere<br />

in New Jersey. His review of The Nickel Ride was<br />

printed in Bright Lights.<br />

C~I .•C)SINC. I)C)lfN rl'lll~ C)I)I~N BC)111)<br />

I» I~'1'nIJIt<br />

IIY Dil VID (~OIJRSEN<br />

DETOUR (1946)<br />

Direction: Edgar G. Ulmer. Story and screenplay: Martin Goldsmith. Cinematography: Benjamin Kline.<br />

Producers Releasing Corporation (PRC). (69 minutes)<br />

The players: Tom Neal, Ann Savage, Claudia Drake, Edmund MacDonald, Tim Ryan, Esther Howard.<br />

Detour is a masterpiece of wry perversity, a film<br />

virtually constructed on irony and paradox: an<br />

incredibly claustrophobic film about hitchhiking on<br />

the "open road"; the bleakest of films noirs, with the<br />

bulk of the action taking place during the day and<br />

away from the city. But perhaps the supreme ironies<br />

relate to the film itself. Despite acting that ranges<br />

16<br />

from incompetent to bizarre, a story line bordering on<br />

the absurd-alternately trashy and fanciful-and a<br />

minimum of sets or characters, Detour somehow<br />

speaks directly and compellingly to the dark side of<br />

several pervasive American myths, forcefully expresses<br />

a coherent vision of the way the world<br />

operates.

. I<br />

I<br />

But if Detour can reward the receptive filmgoer, it<br />

does, by its very nature, demand a little more than<br />

the ordinary film. After all, there is no denying that a<br />

film shot in a very short time (rumored to have been<br />

four days, more likely five or six), on a budget of-it<br />

almost seems-something in the neighborhood of 45<br />

cents, may lack some of the slickness and polish we<br />

ordinarily expect. But if we focus on what the film<br />

offers rather than what it lacks, we can begin to<br />

appreciate what is, on reflection, an extraordinary<br />

piece of filmmaking .<br />

. To understand Detour's wry perversity ,it may be<br />

necessary to know something of the man who made<br />

it, Edgar G. Ulmer: an extraordinarily gifted German<br />

who began his career working with people like Lang<br />

and Murnau, and himself made films in Hollywood<br />

for over 30 years. Yet the biggest "star" he ever<br />

directed was Zachary Scott and his longest shooting<br />

schedule was 12 days, with most of his films made<br />

even more quickly. He deliberately refused to work<br />

for any major studio, preferring the complete creative<br />

freedom and low budgets of Poverty Row. The<br />

"freedom" he found there enabled him to direct<br />

Yiddish-language pictures, a Ukrainian musical, a<br />

Harlem movie, and a prison film called Women in<br />

Chains. Ulmer may have been able to make such films<br />

exactly as he wanted, but with such dubious projects,<br />

with budgets so small many scenes were done in one<br />

take, his freedom often must have seemed as illusory<br />

as that of Detour's hitchhiker.<br />

On the surface, the film is fairly simple: a man<br />

hitchhiking across the country, inadvertently involved<br />

in an accidental death, becomes involved also in a<br />

murder. Initially, his traveling suggests the exercise of<br />

free will, but as the road begins to seem endless this<br />

freedom is revealed as complete entrapment. The<br />

reversal extends even to the ways we perceive the<br />

visual imagery. As he sets out, full of faith and<br />

optimism, riding down the highway in an open<br />

convertible seems like an expansive, liberating experience.<br />

But when later he, as driver of the car, picks<br />

up a hitchhiker himself, all the space "out there"<br />

beyond the car ceases to matter as his circumstances<br />

constrict his existence to the narrow dimensions of<br />

the car's interior. The sequence in question has a<br />

heightened effect precisely because that expansive,<br />

open world is so prominent visually, its physical<br />

proximity so evident yet so increasingly irrelevant to<br />

his existence as the alternatives it offers are increasingly<br />

closed to him. •<br />

This notion of contrast, often extended beyond all<br />

rationality, is central to Ulmer's method. Grim,<br />

sordid, bizarre events take place in the most banal<br />

surroundings, and, because of those events, the<br />

18<br />

meaning of the surroundings themselves is somehow<br />

altered, our responses to them changed. The first<br />

death in the film is an accident so farfetched it seems<br />

surreal, but the second death-a grisly murder by<br />

longdistance telephone-seems to exist beyond all<br />

laws of plausibility. But it is the very implausibility of<br />

the action, juxtaposed with the ordinariness of the<br />

milieu-a nightclub, an apartment, a used car lot, and,<br />

of course,. the road-that gives the film much of its<br />

force. Ulmer is actually taking several American<br />

fantasies ("going west", looking to Hollywood for<br />

success and happiness, finding freedom and happiness<br />

on the open road-cf. Capra's It Happened One<br />

Night) and performing unnatural acts on them, with<br />

devastating effects. If, for example, we think of the<br />

hitchhiker in terms of an Horatio Alger character, we<br />

see that he meets with just the opposite of an<br />

unbroken string of good luck and success; each<br />

ridiculous plot twist narrows his alternatives, increases<br />

his victimization, further emphasizes his lack<br />

of free will. In fact, the closest thing to a moment of<br />

freedom in the movie (though the character doesn't<br />

perceive it as such) comes in the extraordinary'<br />

sequence in which, working in the nightclub he<br />

professes to despise, he plays a brilliant, disjointed<br />

piano improvisation, shown largely through closeups<br />

of his crazily moving fingers.<br />

At the heart of the film, then, is its belief in the<br />

existence of fate: irrational, relentless, malevolent.<br />

Fate seems almost a palpable thing, shaping the<br />

action with a malicious perversity beyond reason,<br />

beyond resistance. But Detour is so perverse it upsets<br />

even our sense of inevitability. From the introduction<br />

we know that the film's flashbacks will gradually<br />

reveal the chain of circumstances that have brought<br />

the character to his present state of desperation. But<br />

we are not really prepared for anything more, for a<br />

final injustice presented in a casual longshot so<br />

indifferent it's practically a throwaway. In retrospect,<br />

this shot perfectly extends the. logic of the main body<br />

of the film by denying that final myth of mobility<br />

and freedom, of the doomed outcast bound to<br />

wander forever.<br />

When we discuss the conditions of Ulmer's career,<br />

the necessity for choosing between "selling out" to a<br />

major studio or working on Poverty Row, we can<br />

easily see how he might have felt a personal affinity<br />

for a project like Detour. It is no accident that the<br />

hitchhiker's intended destination should be Hollywood<br />

where he will find success and happiness.<br />

(There is even one shot in which two characters are<br />

framed in a window that looks for all the world<br />

exactly like a movie screen.) After a decade of Jive<br />

Junctions and Women in Chains, of limited options

and illusory freedom, of entrapment within the<br />

economic imperatives of Hollywood, Ulmer was exceedingly<br />

well-equipped to handle Detour's desperate<br />

fatalism. The film's grim acceptance of a malignant<br />

fate, its deliberate mockery of some of the more<br />

facile American myths, its singular admixture of the<br />

banal and the bizarre surely reflect the director's<br />

belief in the existence of the illusion of free choice,<br />

not the substance of free will. It is hardly surprising<br />

LETTERS<br />

The list of films I managed to see in 1975 was severely<br />

lacking due to my place of residence at that time. Now, once<br />

again, I'm one of Seattle's avid bargain-matinee attenders and<br />

popcorn freaks.<br />

Meanwhile, here's my list of ten best (purely subjective, as<br />

usual): A Brief Vacation, One Flew 0 ver the Cuckoo's Nest,<br />

The Passenger,Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore, A Woman<br />

under the Influence, Man in a Glass Booth, The Mother and<br />

the Whore, Hearts and Minds, Antonia, Nashville.<br />

An older, very likeable film I saw for the first time in '75,<br />

and definitely worth mentioning, is Thieveslike Us.<br />

•<br />

Ann Baxter<br />

Here is a list of my ten favorites among the movies I first saw<br />

in 1975. As you'll notice, I don't count so good, though I can<br />

list things in proper alphabetical order:<br />

The Civil War (John Ford segment of How the West Was<br />

Won, 1962), Detour (Edgar G. Ulmer, 1946), Forty Guns<br />

(Sam Fuller, 1957), Four Sons (Ford, 1928), French Cancan<br />

(Jean Renoir, 1954), Gun Crazy (Joseph H. Lewis, 1949),<br />

Make Way for Tomorrow (Leo McCarey, 1937), Nashville,<br />

Out of the Past (Jacques Tourneur, 1947), The Passenger,<br />

Raw Deal (Anthony Mann, 1948), The Shanghai Gesture<br />

(Josef von Sternberg, 1941), The Tarnished Angels (Douglas<br />

Sirk,1958).<br />

On the negative side, all recent films paled beside the<br />

terribleness of The Terror of Tiny Town, a 1933 musical<br />

western with an all-midget cast. It sounded so funny in the<br />

catalogue (HA unique western adventure that is definitely<br />

'campy' H) I couldn't resist. From now on I'll stick to<br />

Bedtime for Bonzo and Here Come the Nelsons.<br />

David Coursen<br />

•<br />

Eugene,Oregon<br />

Seattle premieres, 1975: The Four Musketeers (Lester), The<br />

Godfather, Part Two (Coppola) [Seattle 1974 =Ed.}, Autobiography<br />

of a Princess (James Ivory), Farewell My Lovely<br />

(Dick Richards), Young Frankenstein (Mel Brooks), Jaws<br />

(Spielberg), Night Moves (Penn).<br />

Personal premieres, 1975: Dodsworth (William Wyler,<br />

1936), Curse of the Cat People (Gunther Fritsch and Robert<br />

that he made of this project perhaps the finest of his<br />

ten-day wonders, a forceful and compelling articulation<br />

of a distinctive world-view. a<br />

David Coursen has been involved in film programming<br />

and film education in the Eugene, Oregon area. His<br />

article on John Ford's Judge Priest and The Sun<br />

Shines Bright appeared in <strong>MOVIETONE</strong> NEWS 42.<br />

Wise, 1944), The Little Foxes (Wyler, 1941), Kiss Me Deadly<br />

(Robert Aldrich, 1955), Secret Agent (Alfred Hitchcock,<br />

1936), Underworld U.S.A. (Sam Fuller, 1961), Unfaithfully<br />

Yours (Preston Sturges, 1948), Wuthering Heights (Wyler,<br />

1939).<br />

Grace A. Cumbow<br />

Olympia<br />

.'<br />

Worst: A Boy and His Dog<br />

Best: Les Violons du bal<br />

Most Overrated: Nashville<br />

Hello. •<br />

Here' are ten that I liked from 1975: Nashville, Le<br />

Petit-Th6tJtre de Jean Renoir, The Man Who Would Be King,<br />

The Wind and the Lion, A Brief Vacation, French<br />

Connection II, Rancho Deluxe, Arabian Nightst<br />

Is for Faket (Welles), Smile.<br />

(Pasof inil , F<br />

In addition, I came upon severalspecial older films for the<br />

first time, including: Moulin Rouge (John Huston), The<br />

Killers (Don Siegel), 'The Leopard (Visconti), Love in the<br />

Afternoon (Billy Wilder), Meet John Doe (Capra).<br />

I appreciate the opportunity to submit this list. It gives me<br />

another chance to recall some very special images.<br />

•<br />

I missedsome, but those I saw:<br />

Tom Huckin<br />

Sincerely,<br />

Michael P. McKinnon<br />

Tacoma<br />

Nashville, The Man Who Would Be King, A Brief Vacation,<br />

Hustle, A Woman under the Influence, Le Petit-ThI!fJtre de<br />

Jean Renoir, Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore, The Wind<br />

and the Lion.<br />

Seen fo he first time in '75-outstanding: Klute (Alan<br />

Pakula, 1971), Day for Night (Truffaut, 1973), The Last<br />

Tango in Paris (Bertolucci, 1974), Tiger Shark (Hawks,<br />

1932), Scarface (Hawks,1932).<br />

Veleda T. Pierre<br />

19<br />

"I<br />

J

IN BLACK & WHITE<br />

"8" MOVIES. By Don Miller. Curtis Books. 350<br />

pages. $1.50.<br />

KINGS OF THE Bs. Edited by Todd McCarthy and<br />

Charles Flynn. Dutton. 561 pages. $6.95.<br />

"If some bright new critic should awaken the world to the<br />

merits of Joseph Lewis in the near future," Andrew Sarris<br />

once wrote, "we will have to scramble back to his 1940<br />

record: Two-Fisted Rangers, Blazing Six-Shooters, Texas<br />

Stagecoach, The Man from Tumbleweeds, Boys of the City,<br />

Return of Wild Bill, and That Gang of Mine. Admittedly, in<br />

this directions lies madness."<br />

Sarris was referring to Lewis' days as a director of<br />

B movies on Hollywood's "Poverty Row," and, as he later<br />

noted, Lewis has been "discovered," and so those seemingly<br />

forgotten B movies from 1940 are marked by auteurists and<br />

cultists for future research. And perhaps it is a form of<br />

madness that auteurists or anyone else should want to<br />

seriously examine the low-budget films turned out as<br />

program fillers on Hollywood's production lines. For there is<br />

little indication so far that this aspect of Hollywood's history<br />

deserves fuller appreciation, and the films themselves have<br />

been mostly unavailable since the last great splurge of<br />

B movies on television.<br />

But the Poverty Row films of Lewis, Edgar G. Ulmer,<br />

Robert Siodmak, Andre DeToth, Anthony Mann and others<br />

loom as tantalizing examples of talent and inspiration<br />

triumphing over limited means. These directors gained<br />

recognition of one sort or another and went on from the Bs<br />

to bigger budgets and better things. But has their later success<br />

given their B movies a visibility not granted so far to worthy<br />

B directors who never graduated to heftier budgets? At<br />

present, we have little way of knowing. Felix Feist, for<br />

example, is a director about whom next to nothing has been<br />

written, but my own chance encounter with The Devil<br />

Thumbs a Ride (RKO, 1947) had sufficient appeal to make<br />

him a subject for further research of my own. Similarly,<br />

Black Angel (Universal, 1946) and a Sherlock Holmes entry<br />

like The Scarlet Claw are enough to indicate that Roy<br />

William Neill is a director worthy of attention.<br />

Beyond questions of auteurist scholarship, however, there<br />

are the peculiar aesthetics of the B movie. Inevitably, part of<br />

the appeal of a "good" B has to do with its having given us<br />

"something" where obvious low-budget conditions led us to<br />

expect little or nothing. In this perspective, criticism can<br />

become dependent on a deliberate scaling-down of values and<br />

expectations (which, as it happens, is pretty much the<br />

approach taken by Don Miller in "B" Movies). But the<br />

unadorned professionalism and the necessary or inevitable<br />

lack of pretension in the B movie can make for a direct,<br />

simple, hard-edged kind of film art. The conventional plots<br />

give filmmakers and performers a space to fill with whatever<br />

vitality and ingenuity they can muster. The result is<br />

20<br />

sometimes a relatively unpremeditated modern folk art, in<br />

which movies are less images of reality than small, bright,<br />

intense additions to it. Or so I tell myself from time to time.<br />

(The B movie is also a fertile ground for the surrealists'<br />

deliberate, imaginative misreadings-but that's another story.)<br />

Don Miller doesn't mess with this sort of thing, but he<br />

does provide information about a great many B movies from<br />

the Thirties and Forties. His book and his Focus on Film<br />

piece (No.5, Winter 1970), together, might have been to the<br />

Bs what Andrew Sarris' The American Cinema is to the<br />

"mainstream" of Hollywood filmmaking. They are not,<br />

simply because Miller's critical standards are so modest, but<br />

the book gives us an interesting (if spottily written) survey of<br />

B moviemaking between 1933 and 1945, and the article<br />

provides a useful list of over 100 worthy B films from a<br />

lengthier period, 1935-1959. Since the book was commissioned<br />

as an expansion of the Focus on Film article, it is<br />

doubly disappointing that the latter's unique aspects were<br />

not incorporated into the longer work. But Miller does call<br />

attention to dozens of interesting-sounding films, and both<br />

his appreciation of professional skills and his "inside information"<br />

on remakes, pseudonyms, box-office opportunism, etc.,<br />

throw some useful light on a relatively unexplored area of<br />

American moviemaking. And after all, it just may be that<br />

Miller's B critic plainness is the only antidote to the madness<br />

contemplated by Sarris.<br />

* * *<br />

I didn't come across Kings of the Bs until most of the above<br />

had been written, but I am happy to report that it serves as a<br />

varied and appealing companion to Miller's work, and often a<br />

more sophisticated and daring one to boot. The book is an<br />

anthology, and it is as concerned with genuine B movies as<br />

with what co-editor Charles Flynn calls "schlock/kitsch/<br />

hack" movies. There are interviews, director pieces, and film<br />

analyses; considerable space is given to producers; the<br />

subjects include Roger Corman, Russ Meyer, Samuel Z.<br />

Arkoff, William Castle, Albert Zugsmith and (somewhat<br />

incongruously) Nicholas Ray's They Live by Night and<br />

Edmund Goulding's Nightmare Alley. There's an abundance.<br />

of fine selections: the editors' informative study of B movie<br />

economics; Myron Meisel's thoughtful piece on Joseph H.'<br />

Lewis; Richard Thompson's highly personal analysis of<br />

Thunder Road; Peter Bogdanovich's interview with Edgar G.<br />

Ulmer; Richard Straehling's survey of "teen films" (from<br />

Rolling Stone); Douglas Gomery's discussion of They Live by<br />

Night (B or no B); a new piece by Andrew Sarris and two old<br />

ones by Manny Farber; and co-editor Todd McCarthy's<br />

filmographies for 325 directors (where else can you find<br />

listings of The Films of Joseph Kane, William Witney, Christy<br />

Cabanne , Lew Landers, Harry Horner, Frank Tuttle, Reginald<br />

LeBorg, Eddie Cline, Lloyd Bacon, Richard Thorpe, William<br />

Beaudine, and Felix Feist, and Roy William Neil!, etc., etc.").

Such ingredients make it a very worthwhile book-and yet<br />

the real Kings of the Bs still remains unwritten.<br />

Any book about B movies will almost inevitably have a<br />

cultist aura about it. But whereas Don Miller's lack of<br />

pretentiousness is especially appealing in that light, the<br />

Flynn-McCarthy anthology pushes the cultist element into<br />

less comfortable territory. Flynn rightly insists that B movies<br />

must be reckoned with as part of our evolving sense of<br />

American film history. But the "schlock/kitsch/hack"<br />

syndrome which hovers over much of Kings of the Bs is<br />

essentially negative: there is an implicit feeling that the Bs are<br />

of interest precisely because they are negations of "serious"<br />

or "prestige" films. But if the Bs are to assume their rightful<br />

place in "film history," then a more positive sense of B movie<br />

chemistry and aesthetics must be developed. What I'd like to<br />

see is not only more "honest criticism," but also an account<br />

of the qualities which make B movies a uniquely attractive<br />

branch of American movies. Such an account might deal with<br />

the appeal of the Bs' directness and simplicity, with their<br />

blend of artifice and raw artifact, with the aesthetics of<br />

blatancy and omission, with the psychology of the lurid, the<br />

petty and the naive. This, too, sounds like madness, but<br />

Kings of the Bs provides several sane leads on the issues<br />

-especially in Thompson's meditation on Thunder Road and -<br />

in Sarris' insights on "Beatitudes of B Pictures": " ... a<br />

disproportionate number 'of fondly remembered B pictures<br />

rail into the general category of the film noir. Somehow even<br />

mediocrity can become majestic when it is coupled with<br />

death, which is to say that if only good movies can teach us<br />

how to live, then even bad movies can teach us how to die."<br />

Peter Hogue<br />

THE BIRTH OF THE TALKIES: From Edison to<br />

[olson. By Harry M. Geduld. Indiana University Press.<br />

337 pages. $12.50.<br />

Most film enthuusiasts have at some point memorized<br />

certain Essential Dates in Film History. 1895: the Lurniere<br />

brothers turned a cafe basement into the world's first<br />

moviehouse and projected the first films for the public with<br />

their cinematograph machine. 1927: Al Jolson starred in The<br />

Jazz Singer (directed by someone or other), the first sound<br />

feature. 1927 sticks in the mind like 1215: the Magna Carta,<br />

of course, but what was the Magna Carta, and where did it<br />

come from? If we know anything about the actual events<br />

that prepared the movies' momentous transition from silence<br />

to sound, it's because we've watched a handful of films from<br />

1927-1928, if we're lucky, and have read a few accounts<br />

based primarily on memory and hearsay. Now Harry<br />

Geduld's book presents a comprehensive history of the<br />

coming of synchronized sound to films. He does not get to<br />

The Jazz Singer until well after the book's halfway point, but<br />

rather addresses first the problem of sorting through the<br />

talkies' murky prehistory.<br />

Geduld begins back in 1877 with Edison's invention of the<br />

phonograph: "Thereafter, from the 1890s to the 1920s, the<br />

history of attempts to link the phonograph and film is<br />

checkered with failures, half-failures, and abortive successes."<br />

Edison's talking machine immediately suggested to some<br />

witnesses the possibility of realistically reproducing life and<br />

movement by having the phonograph operate in conjunction<br />

with a device that could show moving pictures. In a letter to<br />

Nature in 1878, one Wordsworth Donisthorpe of Liverpool<br />

even conceived of a sound feature film in color-a<br />

not-so-faraway vision of the "complete" capture and<br />

reproduction of reality that the cinema promised. Edison also<br />

continued to -work separately on moving pictures, and<br />

-though Geduld (and Gordon Hendricks before him) raises<br />

serious doubt as to whether Edison should be given<br />

credit-his Kinetoscope peep-show was on the market by<br />

1894. He and his assistant W.K.L. Dickson attempted to<br />

achieve a synchronous link between Kinetoscope and<br />

phonograph, but gave up in that same year.<br />

There followed many attempts by other experimenters,<br />

including the British William. Friese-Greene, and Alexander<br />

Black (whose "picture-plays" conceived in 1894 consisted of<br />