TRAINING AND INFORMATION CAMPAIGN ON THE ... - Fokus

TRAINING AND INFORMATION CAMPAIGN ON THE ... - Fokus

TRAINING AND INFORMATION CAMPAIGN ON THE ... - Fokus

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Gambia Committee on Traditional Practices Affecting<br />

the Health of Women and Children (GAMCOTRAP)<br />

with support from FOKUS/NKTF<br />

External review of:<br />

<strong>TRAINING</strong> <strong>AND</strong> <strong>INFORMATI<strong>ON</strong></strong> <strong>CAMPAIGN</strong><br />

<strong>ON</strong> <strong>THE</strong> ERADICATI<strong>ON</strong> OF FGM,<br />

The Gambia<br />

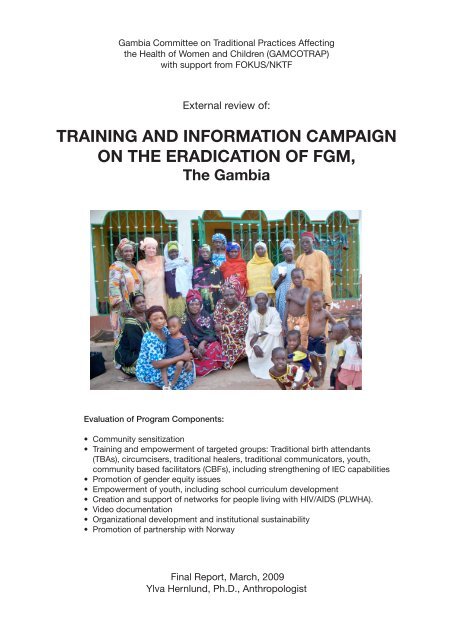

After the group meeting in Mannekunda, Basse (Amie and Ylva on the left, alkalo on far right). The elder <br />

man in white in the front row told me: “This may be a women’s affair, but it affects us men, as well. One <br />

of my wives took our daughter back to her mother’s house to be circumcised. The girl died. We didn’t <br />

use to know the bad effects.” <br />

Evaluation of Program Components:<br />

• Community sensitization<br />

Former circumciser (next to Ylva) was given seed money to start a soap business; she says people have <br />

• stopped even trying to bring girls to her to cut. <br />

Training and empowerment of targeted groups: Traditional birth attendants<br />

(TBAs), circumcisers, traditional healers, traditional communicators, youth,<br />

community based facilitators (CBFs), including strengthening of IEC capabilities<br />

• Promotion of gender equity issues<br />

• Empowerment of youth, including school curriculum development<br />

• Creation and support of networks for people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA).<br />

• Video documentation<br />

• Organizational development and institutional sustainability<br />

• Promotion of partnership with Norway<br />

<br />

Final Report, March, 2009<br />

Ylva Hernlund, Ph.D., Anthropologist

Table of Contents<br />

Executive Summary................................................................................................................................ 5<br />

Results........................................................................................................................................................5<br />

Conclusion and Recommendations..................................................................................................................6<br />

Background of Evaluation/Methodology.............................................................................................. 7<br />

Background to the project...................................................................................................................... 8<br />

Country Background.............................................................................................................................. 9<br />

Terminology........................................................................................................................................... 9<br />

The Practice of FGM in The Gambia................................................................................................... 9<br />

Prevalence............................................................................................................................................... 9<br />

Types........................................................................................................................................................11<br />

Background to Global anti-FGM Campaigns...................................................................................... 11<br />

Gambian anti-FGM Campaigns.......................................................................................................... 13<br />

Actors.......................................................................................................................................................13<br />

Strategies and Challenges............................................................................................................................13<br />

GAMCOTRAP.................................................................................................................................... 14<br />

Organization.............................................................................................................................................14<br />

Mission Statement......................................................................................................................................15<br />

Aims...................................................................................................................................................... 15<br />

Objectives..................................................................................................................................................15<br />

Approaches and Methods............................................................................................................................15<br />

Best Practices........................................................................................................................................ 17<br />

Results................................................................................................................................................... 19<br />

Discussion of objectives reached as proposed...................................................................................... 21<br />

General Observations..................................................................................................................................21<br />

Objectives Met as Proposed.........................................................................................................................22<br />

Unanticipated Outcomes.............................................................................................................................23<br />

Challenges and Adaptations........................................................................................................................23<br />

Monitoring and Reporting...........................................................................................................................24<br />

Cost Effectiveness.......................................................................................................................................24<br />

Partnership with Norway............................................................................................................................24<br />

Conclusions and Recommendations.................................................................................................... 25<br />

Sources Cited........................................................................................................................................ 26<br />

Appendix 1: Terms of Reference......................................................................................................... 27<br />

Appendix 2: Sources of Information Gathered in The Gambia......................................................... 31<br />

Appendix 3: Networks in which GAMCOTRAP participates............................................................. 51<br />

Appendix 4: Activities completed from Under the FOKUS funded Project from 2006 to 2008........ 52<br />

Appendix 5: Cluster Diagram.............................................................................................................. 53<br />

Appendix 6: Contributions from other donors..................................................................................... 54

Acronymes<br />

AEO<br />

AIDS<br />

CBF<br />

CBO<br />

CPA<br />

CRR<br />

FGM/C<br />

FLE<br />

FOKUS<br />

GAMCOTRAP<br />

GAMYAG<br />

HIV<br />

HTP<br />

IAC<br />

IEC<br />

IGA<br />

NGO<br />

NKTF<br />

PLWHA<br />

RH<br />

SHR<br />

SRH<br />

STI<br />

TBA<br />

TP<br />

UNCRC<br />

URR<br />

VAW<br />

VDC<br />

WR<br />

Alternative Employment Opportunity<br />

Aquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome<br />

Community Based Facilitators<br />

Community Based Organization<br />

Child Protection Alliance<br />

Central River Region<br />

Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting<br />

Family Life Education<br />

Forum for Kvinner og Utviklingsspørsmål (Forum for Women and Development)<br />

Gambia Committee on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women<br />

and Children<br />

GAMCOTRAP Youth Advocacy Group<br />

Human Immunodeficiency Virus<br />

Harmful Traditional Practice<br />

Inter Africa Committee<br />

Information, Education, Communication<br />

Income Generating Activities<br />

Non Governmental Organization<br />

Norsk Kvinnelig Teologforening (Norway Women’s Theological Association)<br />

People Living with HIV and AIDS<br />

Reproductive Health<br />

Sexual and Human Rights<br />

Sexual and Reproductive Health<br />

Sexually Transmitted Infection<br />

Tradititional Birth Attendant<br />

Traditional Practice<br />

United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child<br />

Upper River Region<br />

Violence against Women<br />

Village Development Committee<br />

Western Region

Executive Summary<br />

In The Gambia, a majority of women struggle with poverty, lack of education, and constraints on<br />

their decision-making power regarding their own reproductive and sexual health. The Gambian chapter<br />

of the Inter Africa Committee (IAC), the non-governmental organization (NGO) Gambia Committee<br />

on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children (GAMCOTRAP), has for over<br />

two decades been engaged in a campaign of education, sensitization, and activism aimed at eliminating<br />

harmful traditional practices, focusing in particular on abolishing Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) and<br />

early marriage, as well as promoting education and empowerment for women and girls.<br />

The main purpose of this external evaluation was to focus on the implementation and outcome of<br />

the three-year project “Training and Information Campaign on FGM,” funded by NKTF/FOKUS,<br />

Norway. This summative end-of-project evaluation seeks to provide information on the extent to which<br />

project objectives were achieved, on challenges, lessons learned from the experiences, use of resources,<br />

and organizational capacity and needs. Lessons learned about best practices are to be shared for others<br />

to replicate and, while it has been made explicit that no further funding is available from NKTF/<br />

FOKUS for the continuation of these project activities, it is hoped that the findings of the evaluation<br />

will form a basis for securing additional support for GAMCOTRAP’s ongoing efforts.<br />

The evaluation was participatory and designed in close collaboration with the funders and beneficiaries,<br />

and included document review, group meetings with beneficiaries from all the target groups in each<br />

of the project regions, as well as in-depth interviews with GAMCOTRAP staff, beneficiaries, board<br />

members, and partners.<br />

Results<br />

According to GAMCOTRAP’s reports, the information project was carried out in each of<br />

the proposed regions a total of 117 communities. The project directly reached an estimated 2,193<br />

beneficiaries. GAMCOTRAP estimates that an additional 10,965 indirect beneficiaries were reached<br />

(using a multiplier effect of 5; see Appendix 2).<br />

Representatives were trained from all the proposed target groups, which in the proposal were identified<br />

as (primary beneficiaries): women and girls, and (secondary beneficiaries): women group leaders, village<br />

heads, district chiefs, religious scholars, traditionalists, circumcisers, TBAs, traditional healers, and<br />

people living with HIV/AIDS.<br />

The broader aim of GAMCOTRAP is to sensitize communities with the ultimate goal being a<br />

reduction in FGM prevalence and increased empowerment of women and girls, while the specific focus<br />

of this project was to: train traditional birth attendants, circumcisers, and traditional healers in order<br />

to upgrade their skills and awareness regarding the harmful effects of FGM; establish networks of<br />

people living with HIV/AIDS; partner with traditional communicators and train youth drama groups;<br />

intensify Family Life Education and HIV counseling; enlist the support of traditional decision-makers;<br />

and enhance the IEC capacity of community health-providers and traditional healers.<br />

While all stakeholders realize that it is near impossible – especially in the short term – to apply<br />

objective metrics to assess actual reductions in prevalence rates of harmful traditional practices, this<br />

5

evaluation found that all the secondary sub-goals of the proposal appear to have been achieved to<br />

various degrees (at times exceeding them) and included: nine training workshops held, three videos<br />

produced, 15 drama groups trained, 16 schools reached for Family Life Education, 9 networks created<br />

for PLWHA, a Dropping of the Knives ceremony held with 18 participating former circumcisers and<br />

their communities, with an additional 60 circumcisers having declared their commitment to participate<br />

in the second such ceremony.<br />

One of the major strengths of GAMCOTRAP is its sustained efforts over time and the consistency of<br />

its approach and message. While methodology has been adapted over time (as well as from community<br />

to community, depending on need), the basic mandate has remained the same, and no effort is made<br />

to conceal the true agenda of the organization. While in the past GAMCOTRAP has often been the<br />

target of criticism, insults, and even threats, it appears that over time a major shift has taken place<br />

in public awareness and attitudes, and that the overall impression of the organization is positive.<br />

Although methodological trends in anti-FGM interventions come and go, the patient consistency of<br />

GAMCOTRAP’s approach appears to be paying off, as many beneficiaries explained that “change takes<br />

time,” but that they are now ready to consider GAMCOTRAP’s message.<br />

Conclusion and Recommendations<br />

It appears that at this time GAMCOTRAP stands at an important crossroads. After many years<br />

of sustained effort often involving extreme challenges, a shift appears to have taken place, as many<br />

Gambians are now ready to receive and consider GAMCOTRAP’s consistent message. This three-year<br />

project is seen by GAMCOTRAP staff as having been particularly crucial in effecting change, and there<br />

is a great sense of urgency in building on the current momentum.<br />

Major activities of the project have been consistent with proposed objectives, and all sub-goals have<br />

been achieved to various degrees, while important progress appears to have been made towards reaching<br />

the broader goal of gender empowerment and the abandonment of harmful traditional practices.<br />

GAMCOTRAP staff point to the need to expand geographically to areas of the country that remain<br />

unreached by campaigns and call for improved communication between various NGOs working on the<br />

issue of FGM in order to prevent overlapping in the same regions while ignoring others.<br />

Beneficiaries of the project agree with GAMCOTRAP staff that it is important to continue to focus<br />

on outreach and capacity building, while pursuing the continued commitment of traditional circumcisers<br />

to drop their knives. Community members unanimously stressed the need for consistent follow-up in the<br />

form of additional workshops, improved support for CBF’s, and expanded AEOs for former circumcisers<br />

(this was not originally proposed as part of the FOKUS funding). There is a perceived need to expand<br />

efforts with youth groups and to continue working on revising FLE curricula, as well as to strengthen<br />

and expand work with networks of PLWHA. In addition, it is crucial to continue the outreach efforts<br />

of improving IEC capacity of traditional health practitioners and to expand the important dialogue<br />

currently underway between Gambian emigrants (particularly in Spain and Norway) and their home<br />

communities.<br />

This evaluation recommends that GAMCOTRAP continue its community outreach while striving<br />

to strengthen its administrative capacity, particularly in the area of reporting, auditing, and effective<br />

communication with donors. This evaluation strongly urges for more sustained support from funders,<br />

while calling for improved dialogue between GAMCOTRAP and their supporters, as well as continued<br />

efforts to improve communication among Gambian organizations working on similar issues.<br />

6

Background of Evaluation/Methodology<br />

FOKUS/NKTF contacted Ylva Hernlund in 2008 to conduct an external, summative evaluation<br />

of GAMCOTRAP’s three-year project on education against FGM. The evaluator had previously<br />

encountered the organization during her year-long dissertation research in 1997-98. Its staff welcomed<br />

her with open arms in 1996, continuing to include her in their activities throughout the research, allowing<br />

access to a diverse range of research angles: archives in the GAMCOTRAP office library; individual<br />

interviews with staff and board members focusing on their personal histories of arriving at an anti-FGM<br />

position; observation of staff meetings (including budget discussions and planning sessions); preparations<br />

for workshops and campaign events; symposia and press conferences; and youth outreach activities.<br />

GAMCOTRAP staff invited her to travel with them on “trek” to rural areas, at one point even asking<br />

her to assist in leading small group projects by students carrying out Rapid Rural Assessment exercises.<br />

Through these travels she not only got to see firsthand how educational workshops are conducted, but<br />

also enjoyed the informal camaraderie of a group of women always enthusiastic about debating issues<br />

and reminiscing about their rich histories as gender activists.<br />

This report, although primarily based on a field visit in December 2008 and a dissemination exercise in<br />

February 2009, therefore also draws on this previous experience observing the work of GAMCOTRAP,<br />

and reflects comparisons drawn between the climate for such interventions in 1997-1998 versus today.<br />

In discussions with Amie Bojang-Sissoho and Dr. Isatou Touray, the reflection emerged that this time<br />

period in the late 90s, in retrospect, may have marked the most difficult moment of such campaigns; and<br />

this evaluation reflects the observation that a great deal of change has taken place over the last decade<br />

regarding public attitudes to and responses to GAMCOTRAP’s work.<br />

Data were gathered in The Gambia in December 2008 through interviews with GAMCOTRAP staff,<br />

volunteers, and Board members; archival research of reports and campaign materials including videos;<br />

interviews and group meetings with beneficiaries from all the targeted groups in a number of communities<br />

(26 total) in each of the regions included in the project; interviews with representatives from other NGOs<br />

involved in anti-FGM work as well as GAMCOTRAP partner organizations (the evaluator used an<br />

independent translator). In addition an electronic survey was conducted with five stakeholders in Norway.<br />

As the field visit was very brief, it was not possible for the evaluator to directly confirm the numbers<br />

of communities and beneficiaries reached; and this draft report additionally uses information from the<br />

nine project reports which were submitted to FOKUS/NKTF throughout the duration of the project,<br />

as well as a Data on Activities-file submitted by GAMCOTRAP staff to the evaluator at the conclusion<br />

of the data gathering.<br />

In February, 2009, a three-day workshop was held in The Gambia, attended by GAMCOTRAP<br />

staff, the evaluator, and Mette Bråthen Njie and Hanne Slåtten from NKTF (unfortunately the FOKUS<br />

representative was at the last minute unable to attend, due to illness). This meeting involved further<br />

document review, discussions about the experience of the partnership between Norway and The<br />

Gambia, an assessment of administrative and reporting procedures, and a thorough team-review of the<br />

first draft of this report, during which all stakeholders were given an opportunity to add comments and<br />

information and suggest further revisions to be included in the final report.<br />

In addition, a partner meeting was held on February 25 at the TANGO office in Kombo (see<br />

Appendix 2 for a list of attendees). Although the written draft report was not distributed, its major<br />

7

findings were discussed, along with presentations by NKTF, GAMCOTRAP staff, and the President<br />

of the Board; and there was a screening of one of GAMCOTRAP’s videos. The remainder of the day<br />

was spent on a group discussion during which beneficiaries spoke about their experiences with the TV<br />

project, and the NKTF representatives were able to ask follow-up questions (the evaluator was also able<br />

to interview TANGO’s Director, who had not been available during the December visit).<br />

Note: While the production of this report has been a truly collaborative effort, the evaluator naturally takes responsibility<br />

for any errors or shortcomings.<br />

Background to the project<br />

The Feminist Action Group from the 1980s pioneered work on information campaigns regarding<br />

FGM in hospitals, churches, and civil society in Norway. Anne Berit Stensaker (1930 - 2003), who was a<br />

priest and member of the Norwegian Female Theologian Committee, Norsk Kvinnelig Teologforening<br />

(NKTF), was engaged in work against female genital mutilation (FGM) from 1980. This commitment led<br />

to a lot of information about both the work and the team, but this information was never systematized.<br />

In 2004, some members of NKTF were involved in archiving this material. This work led to a contact<br />

with Mette Bråthen Njie, who had received a scholarship to work on the theme of FGM. She is a trained<br />

nurse with close relations to The Gambia, and had visited and brought back information about some<br />

of GAMCOTRAP’s work and methods. After meeting with Mary Small at GAMCOTRAP, she was<br />

impressed by the way they worked, but saw the lack of resources. NKTF also learned more through<br />

meeting with Torild Skard, feminist and former UNICEF Regional Director for West Africa (1994-<br />

1998), who knew of GAMCOTRAP’s work.<br />

After further visits to The Gambia, NKTF in 2005 decided to apply for funding from a project<br />

supported by the TV Action Campaign (through Norwegian TV) on ”Violence against Women,”<br />

where one of the sub-topics was FGM (along with Women in Conflicts, Trafficking, and Violence in<br />

Close Relationships). The TV project was that year dedicated to FOKUS (Forum for Women and<br />

Development), where one NKTF member had previously worked.<br />

Also in 2005, Dr. Isatou Touray was invited by FOKUS through NKTF, coordinated by Mildrid<br />

Mikkelsen, to attend a TV-Campaign meeting in Norway. FOKUS previously knew about her work<br />

through the Inter Africa Committee (IAC) and other NGOs. This visit made it possible for GAMCOTRAP<br />

to present its work to the donor community in Norway with the hope of gaining support for its work<br />

to eliminate FGM in The Gambia. It also created an opportunity for GAMCOTRAP to meet with its<br />

partner organization, NKTF, to get to know each other and discuss the proposal to end FGM, which was<br />

submitted to FOKUS. The Norwegian team consists of five women: Tone Marie Falch, Hanne Slåtten,<br />

Yvonne Anderson, Caroline Revling Erichsen, and Mette Bråthen Njie. During the visit, Isatou Touray<br />

presented the proposal to the team of women and it was discussed intensively and agreed upon.<br />

Dr. Touray was made to understand from this visit and the meetings held between FOKUS/NKTF<br />

and GAMCOTRAP that FOKUS gives support to countries by pairing local Norwegian organizations<br />

with other existing NGOs abroad. The partnership was mutual and accepted by both NKTF and<br />

GAMCOTRAP because their vision, mission, and objective resonate with each other. Having agreed to<br />

work together, GAMCOTRAP’s proposal was accepted and NKTF was made responsible for facilitating<br />

the project with support from FOKUS (FOKUS has no direct co-operation with GAMCOTRAP,<br />

8

ut supports the project co-operation that takes place through FOKUS between its member organizations<br />

and their local partner organizations). To that effect, a project agreement was made between NKTF and<br />

GAMCOTRAP with FOKUS funding to ensure the realization of the project, which operated from<br />

2006 – 2008.<br />

Country Background<br />

The Gambia is one of the poorest countries in the world, dependent from the moment of its<br />

independence to rely on foreign assistance for its survival. The population growth rate (1990-2006)<br />

is estimated at 3.4% per year, infant mortality rate (under 1) at 84 per 100,000 live births, maternal<br />

mortality 730; life expectancy at birth 59 years (UNICEF 2009). The overall literacy for women is<br />

26.9%, 55% for males (Government of The Gambia 1993; more recent UNICEF study does not provide<br />

these numbers). School enrollment is (2000-2006) 79% for males and 84% for females at the primary<br />

level, with 51% males and 42% females at the secondary level (UNICEF 2009). Agriculture provides<br />

60% of productive employment (Government of The Gambia 1993; more recent UNICEF study does<br />

not provide these numbers). There is also a limited impact of tourism, fisheries, “re-export” trade, light<br />

industries, and products from livestock. Continual economic decline has hit women especially hard.<br />

Many Gambians, especially young and middle-aged men, see the only way “out” as a literal escape to<br />

labor markets in the Global North, thus creating a massive movement out of the country with femaleheaded<br />

households left behind.<br />

Terminology<br />

While other terminology is used in other contexts (such as “female circumcision,” “female genital<br />

cutting,” FGC, or FGM/C), the preferred terminology of GAMCOTRAP is Female Genital Mutilation<br />

(FGM), which will be used throughout this report.<br />

The Practice of FGM in The Gambia<br />

Prevalence<br />

All existing studies agree that female genital mutilation is practiced by a substantial majority of<br />

Gambians. Earlier local studies report that 79% (Singateh 1985) to 83% 1 of all Gambian women have<br />

undergone some form of genital mutilation, while others use the Hosken report’s estimate of 60%<br />

(Touray 1993). A Gambian government study (Daffeh et al. 1999) puts the prevalence rate at 80%<br />

overall. More recently, the MICS (Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey) study for UNICEF, “Monitoring<br />

1. Estimated by a 1991 KAP (Knowledge-Attitude-Practice) study, carried out by the Monitoring and Evaluation Unit of<br />

the Women’s Bureau as part of the “Safe Motherhood” component of a Women in Development Project Report.<br />

9

the Situation of Women and Children” estimates that of all women aged 15-49, 78% have undergone<br />

FGM, while 64% of mothers in the same age-group have at least one daughter who has undergone the<br />

practice (UNICEF 2009), seemingly indicating a reduction in prevalence.<br />

These numbers, however, hide the complexity of who in The Gambia is actually practicing FGM and<br />

why. Daffeh et al. caution that previous literature on FGM in The Gambia has displayed “a gap between<br />

theory and practice, with regard to ethnicity” (Daffeh 1999). Daffeh et al. go on to assert that in the Gambian<br />

case, the “ethnic classifications with regard to FGM are much more complex than was hitherto apparent”<br />

(ibid). They are referring to general statements, such as “Wollofs don’t practice female circumcision,”<br />

which various Gambians commonly repeat without qualification. When Wollof girls do undergo FGM, it<br />

has usually been explained as due entirely to pressure from individuals of other ethnic backgrounds that<br />

causes co-wives or schoolmates to “join” their peers in circumcision. It appears, however, that the rate of<br />

circumcision for girls who identify as Wolof (but could have multi-ethnic heritage) is actually quite high.<br />

The Daffeh report presents more nuanced data on ethnicity, focusing on the variation in circumcision<br />

according to ethnic sub-group and ancestral geographic origin. Thus, they argue, for certain sub-groups of<br />

Wollofs FGM is as strong a tradition as it is for Mandinkas and Serahules, among whom the practice is said<br />

to be virtually universal. A total of 96% of Jolas circumcise females, again with variation across sub-goups<br />

(ibid). The authors of the 1999 report conclude that the only ethnic groups in The Gambia that do not at<br />

all practice FGM are the Creoles, the Lebanese, and the Manjagos (ibid).<br />

Although these numbers do throw light on a previously poorly understood area, ethnic and even<br />

sub-ethnic labels are not entirely reliable as indicators of whether a girl will undergo FGM or not. It is<br />

important to note that marriage across ethnic lines is very common and relatively unproblematic in The<br />

Gambia, and that it is typical to encounter Gambians whose relatives come from two or more ethnic<br />

groups. The age at which girls are circumcised is also somewhat tied to ethnicity, although not in any<br />

simple way. Serahule communities generally practice FGM in the first week of the girl’s life, coinciding<br />

with her naming ceremony. In other ethnic communities, the age of circumcision may vary widely.<br />

When initiations take place in a communal context, a group of girls may include infants, young children,<br />

and even teenagers, depending on how long the ritual cycle is until another big celebration rolls around.<br />

In general, however, there is clearly a trend in The Gambia, as elsewhere in Africa, to “circumcise” girls<br />

at a younger and younger age.<br />

Additionally, geographic location impacts prevalence rates. Project reports from The Gambia typically<br />

refer to urban versus rural areas, but it can be a bit difficult to define the two (according to the 2009<br />

UNICEF study, 72% of urban women have undergone FGM, 83% of rural). The Gambia has no true<br />

cities – the capital of Banjul is a sleepy town of a mere 50,000 or so. Most population growth is taking<br />

place in the nearby peri-urban areas of Bakau and Serrekunda – sprawling, densely populated towns<br />

predominantly populated by rural migrants. The 1993 Gambian census bases its definition of “urban”<br />

on: commercial and institutional importance, majority of population engaged in non-agricultural work, a<br />

population of 5,000 or more, high population density, and the presence of some infrastructure. In terms<br />

of FGM, however, prevalence rates in The Gambia do not correspond to facile assumptions of rural<br />

“traditionalism” and urban “progressiveness.” As evidenced in GAMCOTRAP’s reports on its campaign<br />

activities, community abandonment of harmful traditional practices can often be found clustered in very<br />

remote rural areas otherwise considered “traditional,” while the practice remains entrenched in “urban”<br />

centers such as Bakau and Brikama. Additionally, there is – despite the very small size of the country – a<br />

great deal of regional variation in the reach of anti-FGM interventions. Despite past attempts to coordinate<br />

the efforts of various NGOs involved in anti-FGM education and activism, in reality certain regions (such<br />

as the Basse area in URR) have been targeted by sensitization efforts of several different groups, while<br />

other areas (in particular on the North Bank) remain essentially unreached.<br />

10

Types<br />

WHO classifies FGM into the following types:<br />

I. Clitoridectomy (removal of part or all of the clitoris)<br />

II. Excision (removal of the clitoris and all or part of the labia majora)<br />

III. Infibulation (removal of and suturing together of the external genitalia)<br />

IV. Unclassified.<br />

For The Gambia, reports on the most common procedure vary (more recent WHO and UNICEF<br />

studies do not report types for The Gambia). According to one study, a majority of women (44.3%) had<br />

undergone Type II, with 21.4 Type I (Singateh 1985). Another one estimates 56% as having undergone<br />

Type I, 19% Type II (Daffeh et al. 1999). Both studies agree that 6-7% of Gambian women have<br />

undergone “sealing” (notoro), a non-suturing form of infibulation which falls under Type IV, but is unique<br />

to The Gambia (recent research with circumcisers by GAMCOTRAP suggests that this rate may be<br />

higher, but these data have not yet been analyzed). This practice is thought to be particularly prevalent in<br />

areas of the eastern part of the country, as was indeed evidenced by the frequency with which discussions<br />

about the health effects of sealing came up in the evaluation field visits to the Upper River Region.<br />

Background to Global anti-FGM Campaigns<br />

Identifying the most effective and appropriate methods for eliminating FGM is among the most<br />

contested issues surrounding the practice. Early colonial interventions alternately employed strategies<br />

based on the alleged adverse health effects of the practice and discourses framing the practice as<br />

uncivilized, barbaric, and unacceptable in the eyes of Christianity. Such campaigns have reappeared<br />

several times throughout the last century, each time with a slightly different focus. In the 1970s and 80s<br />

the practice was identified as “genital mutilation” and became targeted for “eradication” as a public<br />

health problem (see Hosken 1978). Some, particularly in the West, approached the practice as a human<br />

rights violation, often using extreme rhetoric which has caused a bitterness to still linger over the debates<br />

surrounding the practice and its elimination. Although often offended by the sensationalist manner in<br />

which the issue was discussed by outsiders, many African women have over time invited assistance from<br />

Western donors, and current efforts are largely supported by outside funding being channeled through<br />

indigenous women’s organizations.<br />

A series of conferences and international meetings have been held to address strategies for eliminating<br />

FGM, starting with the 1979 Khartoum seminar on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women<br />

and Children. After an initial reluctance to address the issue, the World Health Organization organized<br />

a meeting at which representatives from a number of African countries began identifying strategies for<br />

eliminating the practice. In the late 1980s, WHO issued an elaborate plan for action, and other major<br />

agencies have since joined the global campaign with their own platforms.<br />

There are several, not mutually exclusive, ways in which to approach anti-FGM campaigns: as a<br />

human rights’ violation, as an infringement of the rights of the child, the right to sexual and bodily<br />

integrity, and/or as to the right to health. Many of those who organize against genital mutilation do so<br />

based on a broader concern for the human rights of women and children, while others also express a<br />

11

concern for women’s sexuality. A number of scholars and activists, however, have concluded that the<br />

most “sensitive” and least controversial angle from which to argue for the elimination of the practice is<br />

that of the right to health and bodily integrity.<br />

A number of African nations have passed legislation against FGM, although enforcement mechanisms<br />

vary. Many feel, however, that outright legislation against the practice, especially during the early stages<br />

of abandonment, is highly problematic as it pits community members against each other, penalizing<br />

individuals acting in good faith within their cultural framework, and potentially driving the practice<br />

underground and reducing the likelihood that those who need medical attention will receive it.<br />

The “development and modernization” approach suggests that overall improvements in socioeconomic<br />

status and education, especially for women, will have far-reaching social effects, including a reduced<br />

demand for FGM. The empirical data do not consistently support this conclusion, however, and many<br />

argue that changing social conditions will not automatically change strongly held beliefs and values<br />

regarding female “circumcision,” but that targeted intervention issues on the harmful effects of the<br />

practice are needed as well.<br />

The “convention theory” of abandonment argues that practices such as FGM are conventions locked<br />

in place by interdependent expectations in the marriage market and that once in place such conventions<br />

become deeply entrenched, since those who fail to comply also risk failing to reproduce (Mackie 2000).<br />

Therefore, education about adverse consequences does not suffice, but must be accompanied by a<br />

collective convention shift. This approach, which has been carried out in practice by the Senegalese<br />

NGO Tostan, uses basic education leading to public declarations in which communities who historically<br />

intermarry join in denouncing FGM.<br />

It is common for activists to argue that one of the reasons that FGM is so “entrenched” is that it<br />

constitutes an important source of income for those performing the procedure. Consequently, some<br />

eradication efforts have focused in part on schemes to compensate circumcisers for lost income. Critics<br />

(see Mackie 2000) argue that this is a misguided functionalism: although circumcisers immediately do<br />

cause circumcision of girls, they do not cause parents to want circumcision for their daughters and<br />

thus do not directly cause the continuation of the practice. Others point out that circumcisers may<br />

receive compensation for not practicing while continuing to do so in secrecy. However, in contexts in<br />

which circumcisers are prestigious community leaders, their genuine conversion is crucial and it may<br />

be an important strategy to provide at least symbolic, and perhaps limited material, support to those<br />

circumcisers who have already had a change of heart, thus motivating them to stick to their decision,<br />

which is distinct from “bribing” people to stop.<br />

Some groups and communities have experimented with alternative, non-circumcising rituals, for<br />

example in Kenya and The Gambia. The success of such an approach has not been documented,<br />

however, and there are reports from Kenya that girls who have undergone “ritual without cutting” have<br />

later been coerced into actual genital cutting.<br />

While these approaches have been discussed separately, in reality most campaigns combine a variety<br />

of strategies into an integrated approach.<br />

12

Gambian anti-FGM Campaigns<br />

Actors<br />

The Gambian campaign can be traced back to the early 1980’s when a small group of women,<br />

most of who are to this day involved in work against FGM, began an organized effort to abolish genital<br />

cutting. It started through the Women’s Bureau, which represented The Gambia at a general meeting<br />

in Dakar of the Inter Africa Committee (IAC) in February of 1984. Due to the perceived need to<br />

address FGM separately from the broader goals of the Women’s Bureau, the Gambia Committee of the<br />

IAC was then created and, in 1992, its name was changed to GAMCOTRAP (Gambia Committee on<br />

Traditional Practices Affecting Women and Children).<br />

In the early 1990’s the splinter group BAFROW (Foundation for Research on Women’s Health,<br />

Development and the Environment) was established, and GAMCOTRAP moved to its present location.<br />

By the late 1990s a newer group, APGWA (Association for Promoting Girls’ and Women’s Advancement<br />

in The Gambia), focused on alternative non-cutting ritual. In later years, a number of other organizations<br />

have in various ways been involved in anti-FGM work.<br />

Strategies and Challenges<br />

Those involved in efforts to abolish FGM have through the findings of several research studies<br />

been able to design more appropriate strategies. It has been found, for example, that in the Gambian<br />

context there is a great need to address the widespread but unfounded belief that female “circumcision”<br />

is a religious injunction in Islam. In her 1993 report, Isatou Touray argues that the practice can<br />

only be approached as a health issue after or simultaneously with approaching it from a sociocultural<br />

and religious angle. The vast majority of Gambians are Muslims (90%+) and FGM is often seen as<br />

somehow associated with Islamic identity. Activists stress, however, that the Qu’ran does not require<br />

female “circumcision,” that not all Islamic groups practice FGM, and that many non-Islamic ones<br />

do. In contexts in which Islam is to various degrees invoked as associated with the continuance of the<br />

practice it is often the focus of intense local theological debates, and a great deal of effort by scholars<br />

and activists has concentrated on demonstrating the lack of scriptural support for enforcing FGM,<br />

as is particularly evident in GAMCOTRAP’s close collaborations over time with religious leaders.<br />

In addition, this debate has benefitted from the recent Rabat Declaration (2007), in which Islamic<br />

scholars from many nations openly opposed FGM. The evaluation confirmed that many Gambians<br />

bring up the issue of religion and have come to see the practice of FGM as separate from religious<br />

requirements.<br />

Currently a number of African countries, including neighboring Senegal, have passed laws against<br />

FGM, while The Gambia has not done so. Interviewees pointed to the difficulties that ensued when<br />

the law was passed in Senegal and there was an increase in demand for cross-border circumcision<br />

in The Gambia – a situation that is still encountered by some circumcisers in URR who live close to<br />

the Casamance border. Although far from all respondents expressed support for national anti-FGM<br />

legislation as a strategy at the present time, GAMCOTRAP has through the duration of the FOKUS<br />

project identified increasing calls from communities for such legislation, which the organization now<br />

supports.<br />

13

In the absence of anti-FGM legislation, up to the present, attempts have been made to bring charges<br />

under existing assault laws when girls have been circumcised against their wishes and those of their<br />

families, so far unsuccessfully. GAMCOTRAP submitted a draft of areas for inclusion in law reform on<br />

women’s rights, including FGM, in 2008, after a request by the Law Reform Commission, and became<br />

involved as advocates in the Awa Nget case (Asemota, 2002a, 2002b) with the help of funds raised<br />

through the Urgent Action Fund through Equality Now’s Africa Region.<br />

Anti-FGM work has at times been considered highly controversial in The Gambia. In 1997, the thennewly<br />

elected Gambian government issued a decree which banned the broadcasting on state radio and<br />

TV (the only TV station in the country was controlled by the government) of any programs “which either<br />

seemingly oppose female genital mutilation or tend to portray medical hazards about the practice.” This<br />

information came to the public in 1997 when Dr. Isatou Touray was conducting a gender class for media<br />

practitioners and issues of traditional practices were discussed in order to create awareness amongst<br />

media practitioners.<br />

It was during this class that a media directive dated 17 th May 1997 banning any form of advocacy<br />

against female genital mutilation on national radio or television was accessed. GAMCOTRAP responded<br />

to the directive by making a clarion call to the President of the Republic in an open letter dated 27 th<br />

May 1997. After massive protests – from in particular GAMCOTRAP, aided by an international letterwriting<br />

campaign organized by New York-based Equality Now – the decree was lifted, although with so<br />

little publicity that many people are still unclear on what is and is not legal to broadcast.<br />

Vice President Isatou Njie-Saidy, herself a women’s rights activist who has previously been involved in<br />

the campaign against FGM, was later quoted as stating that the government’s policy will be to “discourage<br />

such harmful practices,” and that NGOs will not be prevented from working against the practice (Forward<br />

with The Gambia newsletter July 7, 1997). Head of State President Colonel (Retired) Yaya Jammeh, in his<br />

annual address marking the 1994 July 22 military take-over, clarified the government’s position as being<br />

opposed to FGM, but stressed that any campaign must be conducted in a culturally sensitive manner.<br />

Yet, later he issued a statement that activists “cannot be guaranteed that after delivering their speeches,<br />

they will return to their homes” (Observer newspaper, January 25, 1999).<br />

GAMCOTRAP<br />

Organization<br />

GAMCOTRAP was established in 1984 as the Gambian chapter of the Inter Africa Committee.<br />

It is an NGO, with non-profit status, registered with the NGO Affairs Agency and The Association<br />

for Non-Governmental Organizations (TANGO), an umbrella organization that registers, monitors,<br />

and supports Gambian NGOs . GAMCOTRAP has a General Assembly, Board of Directors, and<br />

Executive Committee. The General Assembly is the supreme organ of GAMCOTRAP and is composed<br />

of the representatives of communities and all other affiliates. The elected Board of Directors includes<br />

a President, Vice President, and Treasurer, as well as other individuals with varied expertise relevant<br />

to GAMCOTRAP’s work. Like all NGOs registered by TANGO, GAMCOTRAP has a Constitution,<br />

Action Plan, and Guiding Principles, and has been registered under the Company Act as a Charity with<br />

the Attorney General’s Chambers.<br />

14

GAMCOTRAP collaborates with the Women’s Bureau, which advises the government on all policy<br />

matters affecting Gambian women. In addition, GAMCOTRAP participates in an ongoing manner in<br />

a number of networks on the international, national, and grassroots level (see Appendix 3).<br />

Mission Statement<br />

“GAMCOTRAP’s mission is to create awareness about traditional practices in The Gambia. We aim<br />

for the preservation of beneficial practices (such as breastfeeding) as well as the elimination of harmful<br />

traditional practices.<br />

GAMCOTRAP is committed to the promotion and protection of women and girl children’s political,<br />

social, educational, and sexual and reproductive health rights.<br />

We support any national and international declarations protecting these rights, in particular the<br />

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, The Convention on the<br />

Rights of the Child, and the Protocol of the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights and on the<br />

Rights of Women.”<br />

Aims<br />

“To create and raise the consciousness of men and women about traditional practices that negatively<br />

affect the health of children and women, whilst encouraging positive practices. In addition, we aim to<br />

protect the rights of children and women by involving them to participate in decision-making processes.”<br />

Objectives<br />

1. To carry out research into traditional practices that affect the sexual and reproductive health<br />

of women and girl children in The Gambia.<br />

2. To identify and promote traditional practices that improve the status of girl-children and women.<br />

3. To create awareness of the effects of harmful traditional practices on the health of girlchildren<br />

and women, in particular FGM, nutritional taboos, child/early marriage, and wife<br />

inheritance.<br />

4. To promote and encourage the education of girls at all levels.<br />

5. To sensitize and lobby decision- and policy-makers about sociocultural practices that are<br />

harmful to the health of girl-children and women.<br />

6. To promote and protect the human rights of girl-children and women.<br />

7. To create awareness of international and national instruments that address discrimination<br />

and violence against girl-children and women.<br />

8. To influence policies in promoting and protecting women’s and children’s rights.<br />

9. To highlight a rights-based approach to activities.<br />

10. To solicit funds locally and externally for the purpose of carrying out the above objectives.<br />

Approaches and Methods<br />

GAMCOTRAP believes that the elimination of harmful traditional practices has to be approached<br />

through research, training, and advocacy. It employs a multi-pronged approach that seeks to match the<br />

15

appropriate strategy to specific community characteristics, with its work consisting primarily of carrying<br />

out educational and “sensitization” campaigns, as well as lobbying. Its staff members visit schools<br />

(including organizing essay and poster competitions), hold press conferences and symposia, produce<br />

videos, and organize workshop for health workers, traditional healers, TBAs, circumcisers, and youth.<br />

GAMCOTRAP has remained adamantly opposed to alternative rituals, and subscribes to a philosophy<br />

of ultimate total abandonment of FGM, “zero tolerance” and advocates for the passing of national anti-<br />

FGM legislation. Recently the organization has intensified its efforts to build dialogue with emigrant<br />

Gambians in the diaspora, spreading awareness of the legal consequences of sending foreign-born girls<br />

“home” for “holiday circumcisions.”<br />

GAMCOTRAP sees the main factors influencing the practice of FGM in The Gambia as being:<br />

1. Sociocultural.<br />

2. Religious<br />

3. Other factors (including ignorance/poverty of practitioners).<br />

Its methods, therefore, are grounded in varied approaches, including: awareness-raising, grassrootssensitization<br />

regarding HTPs, collaboration with respected religious leaders able to address scriptural<br />

issues, community education about the harmful effects of FGM, and support for circumcisers committed<br />

to ending the practice.<br />

Training workshops are organized by first dividing participants by village, then into groups (such<br />

as young or old women or men, TBAs, circumcisers, traditional healers), then having all participants<br />

come together into a “plenary” discussion. This way, “everyone has to face everyone.” This is especially<br />

important when men and women each claim that it is the other group that requires that FGM be<br />

practiced. Participants are asked to first list the traditional practices they are aware of in their community<br />

and later to rank them as “positive,” “negative” or under “lack of consensus.”<br />

An important component of awareness-raising is the use of visual aids, including anatomical<br />

models and a slide show that presents adverse health effects of genital cutting, but GAMCOTRAP<br />

hopes to develop its own materials based on Gambian cases). While some activists from other groups<br />

expressed disagreement with the method of “shocking” trainees with graphic images of health effects,<br />

GAMCOTRAP staff sees this “awakening” as central to the process of attitude change (and point out<br />

that the goal is not to “shock,” although this is sometimes the effect). The evaluation, as well, found that<br />

most beneficiaries, when asked what had most affected their attitudes to FGM, responded that they<br />

had become aware of the adverse health consequences. When probed to explain more about what<br />

specifically affected their change in attitudes, a majority of beneficiaries interviewed mentioned the<br />

visual aids and pointed out that “health is the most important thing for human beings.” They stressed<br />

that “seeing is believing” and that although many of them had previously been told that FGM is harmful,<br />

they did not believe this to be true until they saw the photos of actual women and girls suffering adverse<br />

consequences (such as retention of urine and/or menstrual blood, and severe keloid scarring). This led<br />

to realizations that the beneficiary herself and/or someone close to her had also suffered these health<br />

effects, while perhaps having attributed them to other causes.<br />

GAMCOTRAP activists argue that there is little resistance to showing these visual materials to groups,<br />

including those of mixed age and gender, although they always preface such viewings with a warning<br />

and make it clear that anyone is free to leave (which religious elders occasionally do), and the images are<br />

only presented at the end of the training session when group discussion and general sensitization have<br />

already been concluded. The evaluator was struck by the nearly universal mention by respondents that<br />

16

it was the images that had made them see the truth in the anti-FGM message. In addition, videos are<br />

shown during the training workshops to reinforce the message on the harmful effects of FGM, as well as<br />

the spread awareness of HIV/AIDS.<br />

GAMCOTRAP tailors its educational approach to the target group and each community’s discussions<br />

take on their own character according to local needs and concerns. When a major tumbling block during a<br />

community discussion appears to be religion, clarification is provided by a resource person. In workshops<br />

with traditional healers, information on HIV transmission is disseminated as these practitioners are<br />

often the first point of contact and need training in how to recognize signs and encourage patients to<br />

seek testing. Traditional birth attendants ask for kits and more training and are encouraged to use ICE<br />

on FGM after the birth of any girl. In the Wuli workshop there was a discussion on the definition of<br />

“early” marriage and what sharia has to say about a girl’s preferred age at marriage.<br />

In several communities, women expressed their fear to seek family planning for fear of being accused<br />

of infidelity, while men said they approved of married women spacing births but would not agree to<br />

contraceptives being made available to unmarried young women. In Foni, there was an expressed<br />

concern with domestic violence, which women stated is often justified by religion, which was refuted by<br />

a religious scholar, who argued that men and women need to be partners in marriage.<br />

Youth were engaged in discussions on reproductive health, and health threats such as poverty, drugs,<br />

alcohol, and early pregnancy. Brochures were handed out, as were condoms, and they were encouraged<br />

to, anonymously put their questions about sex in a box, the “Secret Clinic,” to be answered in front<br />

of the group. Youth asked for drama groups, video, and sometimes made statements such as that they<br />

will burn the jujuyo (traditional circumcision hut), conduct Peace Marches, and report the names of<br />

any circumcisers still practicing (GAMCOTRAP clarified that they will only sensitize, not bring legal<br />

action).<br />

One particularly crucial target group consists of the ngangsingbas, traditional circumcisers. As opposed<br />

to elsewhere in Africa, FGM is never performed by male practitioners or by female health professionals.<br />

GAMCOTRAP has taken particular care to reach these women, who retain their important role in<br />

society after abandoning the practice. Eighteen former circumcisers participated in the Dropping the<br />

Knife celebration of May, 2007 (see Results), and GAMCOTRAP states that currently more than sixty<br />

others are committed to abandoning the practice and participate in the next Dropping of the Knife.<br />

Best Practices<br />

GAMCOTRAP’s self-assessment identifies its major strength as lying in its staff of committed<br />

activists. Dr. Touray and Ms. Bojang-Sissoho are both circumcised Mandinka women with a deep<br />

understanding of both the cultural and religious context and Gambian political realities. While acutely<br />

attuned to the need to follow local etiquette, they are resilient and courageous, and consistently display<br />

remarkable flexibility and insight (as well as compassion and humor) when dealing with often rapidly<br />

changing circumstances in the field. They are extremely well-versed in not only international human<br />

rights protocols but also Islamic theology, and can engage in culturally and religiously sensitive dialogue<br />

with a wide range of individuals and groups, always ”taking the pulse” of which approach is most<br />

appropriate with a particular person or community. This ability is something that can not be learned<br />

through formal training, but can only be found in a true ”insider.” Additionally, they are both extremely<br />

17

effective public speakers with fluency in several local languages. The TV-project has been especilly<br />

instrumental in freeing up Dr. Touray to work full-time on coordinating the project.<br />

GAMCOTRAP does not employ an approach of stressing charismatic personalities. Although both<br />

Amie and Isatou are indeed well known and respected in the communities in which they work (and their<br />

names at times show up in praise-songs) they stress that ”GAMCOTRAP is not Amie or Isatou.” The<br />

groundwork that they have done over so many years could be continued by other dedicated activists,<br />

and there is evidence of training of junior staff and volunteers and the transfer of competency, as was<br />

particularly demonstrated by the active participation in the dissemination exercise of Musa Jallow and<br />

Omar Dibbah. This philosophy was also evident during the field visit (as was also the case during the<br />

evaluator’s travels with the group in 1997-98) – GAMCOTRAP staff behave in an extremely humble<br />

way when ”on trek.” They use very modest accomodations, eat simple food, and work long hours without<br />

ever complaining about discomfort or fatigue. GAMCOTRAP staff meet community members on their<br />

own terms, joining them in their work and domestic responsibilities. They are acutely aware of farming<br />

cycles and women’s domestic labor burdens and make a genuine and concerted effort to empathize with<br />

the realities of the people they are trying to reach. GAMCOTRAP also has a firm policy of not handing<br />

out cash to praise-singers, kanyelengs, and others. Instead, they budget for a collective contribution to be<br />

given at the end of the visit to a designated group of women.<br />

GAMCOTRAP are veterans in the field of anti-FGM activism and are anchored in long-term<br />

relationships with the communities they serve, and their approach is characterized by frankness and<br />

transparency. While remaining attuned to the need to show respect (especially for elders, dignitaries, and<br />

individuals with particular prestige) the activists never conceal their agenda nor make excuses for their<br />

convictions. Because there has been no attempt throughout the sustained campaign to veil the message<br />

or hide it within other agendas, GAMCOTRAP appears to have ultimately gained the respect of the<br />

populations they have worked so long to sensitize.<br />

While never straying from the agenda that was set out at the inception of the Gambian IAC chapter,<br />

it is evident that GAMCOTRAP staff display flexibility and adaptability in tailoring their message to<br />

specific community realities and are open to making adjustements in campaign approaches over time.<br />

Thus, there has in some communities been a greater emphasis than in others on refuting the allegation<br />

that FGM is a religious injunction and breaking the taboo of men as sole custodians of religion; and<br />

GAMCOTRAP shows great skill in utilizing collaborations with religious scholars. They also display a<br />

great deal of insight into geographic and ethnic variations in the practice of FGM; and presentations<br />

are angled to best resonate with community realities. During the field visit, this was particularly evident<br />

in the advice offered regarding reproductive health care surrounding consummation of marriage in<br />

communities practicing ”sealing,” (an important component of the strengthening of IEC capacity of<br />

the traditional healers who are usually the first to treat these cases), as well as in discussions about Spain’s<br />

anti-FGM law in villages that have seen many of its young people emigrate there.<br />

When asked what changes have emerged in their campaign strategies over time, they pointed to<br />

the increasing use over the last few years of traditional communicators and drawing on the cultural<br />

centrality of dance, song, and music. Also, in the past, there was more of a strategy of training a few<br />

representatives from each of many communities, while they have now realized that this places too much<br />

of a burden on a few people to return to their communities and try to recount all that they learned<br />

in training and alone attempt to effect collective change (this was also expressed in some of the field<br />

interviews as extremely challenging by attendees who pleaded for the support of workshops to be held<br />

in their communities). Now they focus instead on mass meetings and collective change through targeting<br />

a ”cluster” of villages centered around a major community (see Appendix 5 for adiagram) aimed at<br />

18

consensus building and values clarification, with the ultimate goal being participation of additional<br />

communities in the next Dropping of the Knives ceremony.<br />

Outside observers noted that GAMCOTRAP activists have ”toned down” their rhetoric over time.<br />

They felt that earlier presentations were often overly emotional and passionate and, while they could<br />

sympathize with this (given the activists’ own personal experiences with the practice), they welcomed<br />

a”cooler” and less emotional manner of delivery. In general, when chatting with ”regular” Gambians,<br />

the evaluator found that the impression of GAMCOTRAP was very positive (”those people are really<br />

working hard to help people”), which differs from often-heard comments in the late 1990s that ”these<br />

people don’t know what they are talking about.<br />

In addition, GAMCOTRAP staff seems particularly savvy when intuiting prevailing trends and<br />

adapting their ongoing message. This was made explicit in their use, at the right moment, of the<br />

visual illustrations of adverse health effects. They have also picked up on the current dialogue between<br />

Gambians at home and those who have emigrated to European countries that have passed strict anti-FGM<br />

legislation that includes clauses on extraterritoriality which makes it a crime to have a girl circumcised<br />

abroad. During the field visit, Amie Bojang consistently discussed (often in a casual manner before<br />

formal meetings commenced) the legal and social consequences were a local circumciser to agree to<br />

circumcise a European-born Gambian girl sent back to her ”home” villlage for holidays (especially those<br />

from Spain, where Isatou and Amie visisted the Gambian community in November 2008, altough this<br />

trip was not funded by the TV Project). As one circumciser in URR responded: ”We tell them we would<br />

have to be insane to take that risk.” It is likely that such a dialogue will be furthered with Gambians in<br />

Norway, where Dr. Touray conducted a workshop in December 2008.<br />

Results<br />

According to GAMCOTRAP’s reporting, the information project was carried out in each of the five<br />

proposed regions (training was held in The Central River Region, Upper River Region, and Western<br />

Region, with networking and organizational headquarters in Kanifing Municipal Area and Banjul Area),<br />

reaching a total of 117 communities. 2 The project directly reached an estimated 2,193 beneficiaries.<br />

GAMCOTRAP estimates that an additional 10,965 indirect beneficiaries were reached (using a multiplier<br />

effect of 5; see Appendix 2).<br />

Representatives were trained from all the proposed target groups, which in the proposal were identified<br />

as (primary beneficiaries): women and girls, and (secondary beneficiaries): women group leaders, village<br />

heads, district chiefs, religious scholars, traditionalists, circumcisers, TBAs, traditional healers, and<br />

people living with HIV/AIDS.<br />

The broader aim of GAMCOTRAP is to sensitize communities with the ultimate goal being a<br />

reduction in FGM prevalence and increased empowerment of women and girls, while the specific focus<br />

of this project was to: train traditional birth attendants, circumcisers, and traditional healers in order<br />

2. What are now called Regions used to be called Divisions. Thus, there was a change from: Lower River Division, Upper<br />

River Division, Central River Division, North Bank Division, Western Division, and Kombo/St.Mary Division and Banjul,<br />

to: Lower River Region, Upper River Region, Central River Region, North Bank Region, Western Region, Kanifing<br />

Municipal Area Council, and Banjul Area Council.<br />

19

to upgrade their skills and awareness regarding the harmful effects of FGM; establish networks of<br />

people living with HIV/AIDS; partner with traditional communicators and train youth drama groups;<br />

intensify Family Life Education and HIV counseling; enlist the support of traditional decision-makers;<br />

and enhance the IEC capacity of community health-providers and traditional healers.<br />

While all stakeholders must realize that it is near impossible – especially in the short term – to apply<br />

objective metrics to assess actual reductions in prevalence rates of harmful traditional practices, this<br />

evaluation found that nearly all the secondary sub-goals of the proposal appear to have been achieved to<br />

various degrees, in some cases exceeding them (for a break-down of proposed versus reached objectives,<br />

see section below. See also Appendix 4):<br />

Training sessions were held in the following communities (data from reports):<br />

• (Report, April 2006) Training Workshop for TBAs, Traditional Healers, and Herbalists on<br />

Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights, in Bansang (250 participants).<br />

• (Report, June 2006) Training Workshop for TBAs, Circumcisers, Traditional Healers (attended by<br />

Norway team), inSuduwol, with participation from 12 cluster villages (113 participants).<br />

• (Report, December 2006) Training Workshop for TBAs, Circumcisers, Parents. Sutukoba, in<br />

Wuli (100 participants).<br />

• (Report, May 2007) Training Workshop for Decisionmakers, in Sangajor, Foni, including 4<br />

villages (162 participants).<br />

• (Report, May 2007) Training Workshop for Youth (ages 16-25), in Basse (99 participants).<br />

• (Report, July 2007) Training Workshop for Senior Secondary School students from CRR, LRR,<br />

NBR, (total reached through peer educators: 841).<br />

• (Report, May 2008), Training Workshop for Traditional Communicators, Women of<br />

Reproductive Age, Circumcisers, Women’s Leaders, and TBAs, in Tambasangsang, URR,<br />

including 13 cluster villages (115 participants).<br />

• (Report 8, May 2008), Training Workshop for Traditional Decision-makers, Imams, in Kulari/<br />

Garawol, URR, including 3 communities (328 participants).<br />

• (Report 9, June 2008) Workshop for Traditional Communicators, in Bantanto CRR, including 6<br />

villages (107 participants).<br />

Network was established of nine groups of PLWHA.<br />

15 youth drama groups were trained.<br />

16 schools were reached for Family Life Education including training on FGM and HIV/<br />

AIDS.<br />

3 videos were produced:<br />

Dropping the Knives Initiative 2006 (3 minutes)<br />

Rhythms against Harmful Traditional Practices 2008 (34 minutes)<br />

Winning the Campaign against FGM 2008 (9 minutes)<br />

Dropping of the Knives celebration by 18 Circumcisers and their Communities planned<br />

and implemented on May 5, 2007, at Independence Stadium, Bakau.<br />

As a result of advocacy and training activities, 18 circumcisers and their communities were motivated<br />

to publicly declare what they have learned about FGM and that they have decided to stop the practice.<br />

These women still maintain their position as leaders in their communities and are a point of reference<br />

on women’s issues. This landmark celebration, in which seven districts took part, was the first of its kind<br />

in The Gambia and has served as an opening for other communities to follow suit.<br />

20

Knives and other instruments were dropped and circumcisers, carrying signs saying “I have stopped<br />

FGM,” recited an oath: “We the circumcisers of The Gambia, representing the cluster villages we cover<br />

have solemnly declared to the world and in particular The Gambia that we have stopped the practice<br />

of FGM in our various communities. Over the years we have received information on women’s health<br />

and have acquired knowledge about the effects of FGM on sexual and reproductive rights and the rights<br />

of the child. Having been empowered with the right information, we hereby publicly declare that we<br />

shall never involve ourselves in the practice of FGM. We take leadership responsibility in protecting and<br />

promoting the best interest of the girl child.”<br />

Each one presented with a Certificate of Honor. Alkalos were also given certificates for their support,<br />

and all clusters for their participation. Cultural performances were presented from several ethnic groups<br />

and remarks were made by: Dr. Isatou Touray, Mrs. Amé Atsu David, from Save the Children, Dr. Nestor<br />

Shivute, Resident representative to The Gambia of the WHO, and Dr. Tamsir Mbowe, Secretary of<br />

State for Health and Social Welfare.<br />

An additional 60 circumcisers have declared their intention to participate in the next<br />

Dropping of the Knives ceremony.<br />

Discussion of objectives reached as proposed<br />

General Observations<br />

A major strength of GAMCOTRAP is its sustained efforts over time and the consistency of its approach<br />

and message. While methodology has been adapted over time (as well as from community to community,<br />

depending on need), the basic mandate has remained the same, and no effort is made to conceal the true<br />

agenda of the organization. While in the past GAMCOTRAP has often been the target of criticism,<br />

insults, and even threats, it appears that over time a major shift has taken place in public awareness and<br />

attitudes, and that overall impressions of the organization are positive. Although methodological trends<br />

in anti-FGM interventions come and go, the patient consistency of GAMCOTRAP’s approach appears<br />

to be paying off, as many beneficiaries explained that “change takes time,” but that they are now ready<br />

to consider GAMCOTRAP’s message.<br />

In general, the evaluator sees the the field visit as having provided ample evidence that the targeted<br />

groups have been reached in the communities visited (and it is important to note that GAMCOTRAP<br />

did not restrict these visits, but offered the evaluator the opportunity to choose any community for a<br />

visit). Observations showed very open community discussions, even in groups including mixed age,<br />

gender, and class. One male elder in URR said: ”This may be a women’s issue, but it affects us men as<br />

well. I had one daughter who died after circumcision.”<br />

There was a sense that change was embraced without looking back, and that no blame was cast<br />

on actions past. As one woman in Basse said: ”What is past is past. Now it is the future.” Circumcisers<br />

remain respected members of their communities and continue to advice women (and many of them<br />

still practice as TBAs). People who used to engage in domestic violence are not castigated, although it is<br />

made clear that such behavior is no longer accepted. In one URR village, a man confessed that he used<br />

to beat his wife because he had simply never questioned it. After the training, he said, he realized that<br />

21

he could instead sit down and discuss with her. ”It is like I have a new wife now,” he said; and when we<br />

drove away from the village, he was standing at the side of the road, his arm around his wife, smiling.<br />

When asked about enforcement, responses varied. In one community in URR, respondents said that ”If<br />

people insist on practicing [FGM] we cannot stop them, but it seems that they aren’t.” In other communities<br />

(in URR and CRR), the councils of elders insisted that ”we are policing around” and that no one in the<br />

community could get away with either FGM , domestic violence, or giving their underage daughter away in<br />

forced marriage. Clearly, the concrete reductions in such practices remain to be seen, but the evaluator still<br />

perceives the sentiments expressed during the field visit as radically different from what was said ten years ago.<br />

A number of circumcisers professed that they were relieved to no longer have to practice FGM. One<br />

circumciser’s assistant in Wuli exclaimed: ”This is one burden I no longer have to carry!” Many mentioned<br />

that they were ready to participate in a Dropping of the Knife ceremony, and there was some indication that<br />

if this does not come to pass they may not start practicing again but will feel that they have been marginalized<br />