Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

DOWNBEAT JEFF “TAIN” WATTS/LEWIS NASH/MATT WILSON // LES PAUL // FREDDY COLE // JOHN PATITUCCI<br />

NOVEMBER 2009<br />

DownBeat.com<br />

$4.99<br />

11<br />

0 09281 01493 5<br />

NOVEMBER 2009 U.K. £3.50

November 2009<br />

VOLUME 76 – NUMBER 11<br />

President<br />

Publisher<br />

Editor<br />

Associate Editor<br />

Art Director<br />

Production Associate<br />

Bookkeeper<br />

Circulation Manager<br />

Kevin Maher<br />

Frank Alkyer<br />

Ed Enright<br />

Aaron Cohen<br />

Ara Tirado<br />

Andy Williams<br />

Margaret Stevens<br />

Kelly Grosser<br />

ADVERTISING SALES<br />

Record Companies & Schools<br />

Jennifer Ruban-Gentile<br />

630-941-2030<br />

jenr@downbeat.com<br />

Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools<br />

Ritche Deraney<br />

201-445-6260<br />

ritched@downbeat.com<br />

Classified Advertising Sales<br />

Sue Mahal<br />

630-941-2030<br />

suem@downbeat.com<br />

OFFICES<br />

102 N. Haven Road<br />

Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970<br />

630-941-2030<br />

Fax: 630-941-3210<br />

www.downbeat.com<br />

editor@downbeat.com<br />

CUSTOMER SERVICE<br />

877-904-5299<br />

service@downbeat.com<br />

CONTRIBUTORS<br />

Senior Contributors:<br />

Michael Bourne, John McDonough, Howard Mandel<br />

Austin: Michael Point; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago:<br />

John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer,<br />

Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana:<br />

Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk<br />

Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis:<br />

Robin James; Nashville: Robert Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring,<br />

David Kunian; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler,<br />

Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie,<br />

Ken Micallef, Jennifer Odell, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom<br />

Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, Michael Weintrob, Kevin Whitehead; North<br />

Carolina: Robin Tolleson; Philadelphia: David Adler, Shaun Brady, Eric Fine;<br />

San Francisco: Mars Breslow, Forrest Bryant, Clayton Call, Yoshi Kato;<br />

Seattle: Paul de Barros; Tampa Bay: Philip Booth; Washington, D.C.: Willard<br />

Jenkins, John Murph, Bill Shoemaker, Michael Wilderman; Belgium: Jos<br />

Knaepen; Canada: Greg Buium, James Hale, Diane Moon; Denmark: Jan<br />

Persson; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Detlev Schilke, Hyou Vielz;<br />

Great Britain: Brian Priestley; Israel: Barry Davis; Japan: Kiyoshi Koyama;<br />

Netherlands: Jaap Lüdeke; Portugal: Antonio Rubio; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu;<br />

Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert.<br />

Jack Maher, President 1970-2003<br />

John Maher, President 1950-1969<br />

SUBSCRIPTION INFORMATION: Send orders and address changes to: DOWNBEAT, P.O. Box 11688,<br />

St. Paul, MN 55111–0688. Inquiries: U.S.A. and Canada (877) 904-5299; Foreign (630) 941-2030.<br />

CHANGE OF ADDRESS: Please allow six weeks for your change to become effective. When<br />

notifying us of your new address, include current DOWNBEAT label showing old address.<br />

DOWNBEAT (ISSN 0012-5768) Volume 76, Number 11 is published monthly by Maher Publications,<br />

102 N. Haven, Elmhurst, IL 60126-3379. Copyright 2009 Maher Publications. All rights reserved.<br />

Trademark registered U.S. Patent Office. Great Britain registered trademark No. 719.407. Periodicals<br />

postage paid at Elmhurst, IL and at additional mailing offices. Subscription rates: $34.95 for one<br />

year, $59.95 for two years. Foreign subscriptions rates: $56.95 for one year, $103.95 for two years.<br />

Publisher assumes no responsibility for return of unsolicited manuscripts, photos, or artwork.<br />

Nothing may be reprinted in whole or in part without written permission from publisher. Microfilm<br />

of all issues of DOWNBEAT are available from University Microfilm, 300 N. Zeeb Rd., Ann Arbor,<br />

MI 48106. MAHER PUBLICATIONS: DOWNBEAT magazine, MUSIC INC. magazine, UpBeat Daily.<br />

POSTMASTER: Send change of address to: DownBeat, P.O. Box 11688, St. Paul, MN 55111–0688.<br />

CABLE ADDRESS: DownBeat (on sale October 20, 2009) Magazine Publishers Association<br />

Á

DB Inside<br />

Departments<br />

8 First Take<br />

10 Chords & Discords<br />

13 The Beat<br />

16 Vinyl Freak<br />

20 Caught<br />

22 Players<br />

E.J. Strickland<br />

Aram Shelton<br />

Sunny Jain<br />

Pedro Giraudo<br />

53 Reviews<br />

76 Transcription<br />

78 Jazz On Campus<br />

82 Blindfold Test<br />

Bill Stewart<br />

CLAY WALKER<br />

Freddy Cole<br />

DOWNBEAT U DRUM SCHOOL<br />

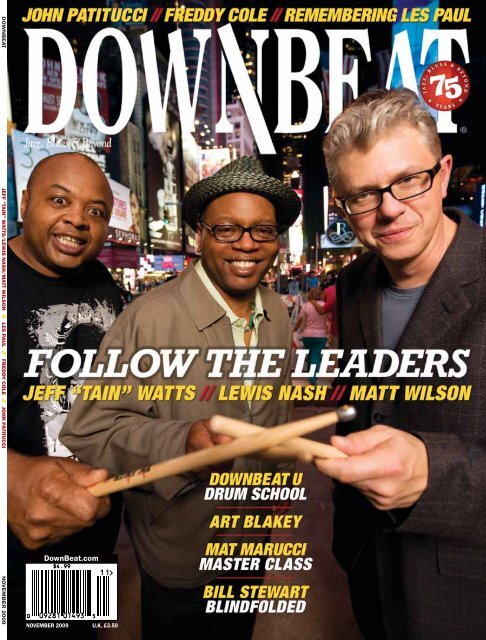

26 Jeff “Tain” Watts/Lewis Nash/Matt Wilson<br />

Follow The Leaders // By Ken Micallef<br />

The history of jazz drummers as leaders is illustrious if not particularly longlived.<br />

Often relegated to “drummer only” or “non-musician” status by ignorant<br />

fellow musicians, jazz drummers have conquered the odds to create music easily<br />

on par with that of any instrumentalist. This summer, DownBeat invited three<br />

of today’s premier drummer/leader practitioners to discuss their art, their drumming<br />

and their place in the lineage of the legends who preceded them.<br />

32 Art Blakey<br />

Classic Interview:<br />

Bu’s Delights and Laments<br />

By John Litweiler // March 25, 1976<br />

34 Toolshed<br />

44<br />

38 Master Class<br />

by Mat Marucci<br />

Features<br />

40 Les Paul<br />

In Praise of a Master<br />

By Frank-John Hadley<br />

44 Freddy Cole<br />

Plays Your Song<br />

By Ted Panken<br />

48 John Patitucci<br />

At the Crossroads of Melody, Rhythm and Harmony<br />

By Dan Ouellette<br />

64 Grant Geissman 65 Edward Simon Trio<br />

68 Steve Lehman 61 Fred Hersch<br />

6 DOWNBEAT November 2009<br />

Cover photography by Jimmy Katz

First Take<br />

By Ed Enright<br />

Jeff “Tain” Watts, Lewis Nash and Matt Wilson: an atmosphere of camaraderie<br />

JIMMY KATZ<br />

Drummers With Vision<br />

My friend Gilbert was a drummer with a vision: to lead his very own big<br />

band, his way. He invited me to join his group at its onset, during the summer<br />

of 1981. I accepted, mostly because of my fondness for him, and partly<br />

out of my enthusiasm for playing saxophone. I was only 14 at the time,<br />

but that decision has had a profound effect on me and the course my life<br />

has taken ever since.<br />

Gilbert rushed the beat like nobody’s business—partly out of youthful<br />

inexperience, but mostly out of genuine enthusiasm. And he didn’t exactly<br />

have what you’d call straightahead jazz chops. But that didn’t matter to us.<br />

He held it together. He held us together. He led a great band and he treated<br />

and paid everybody fairly. Gil made it fun. And he always sprung for<br />

beer—even though we were all well underage, even when we broke his<br />

rules and fought among ourselves and made the music feel like work.<br />

It was because of Gilbert that cats wanted to play, and stay, in the<br />

Outcasts.<br />

Gilbert was an orchestrator on a grand scale. No arranger or composer<br />

of music—he couldn’t even sing—he was a true leader who brought<br />

together friends from each side of the tracks for more than just gigs, but<br />

also matches of four-square, Euchre and football, not to mention rebelling<br />

against authority and subverting established social norms. There was a<br />

good reason why he named us the Outcasts. He loved our quirks and<br />

encouraged all of us to wear our individuality proudly.<br />

The Outcasts were, and still are, Gilbert’s band. He died young in<br />

1994, but the band lives on, just as he would have wanted it. His powerful<br />

presence, a source of true inspiration, continues to be felt, even in his<br />

absence.<br />

Reading over Ken Micallef’s cover story for this issue (see page 26) on<br />

drummers Jeff “Tain” Watts, Lewis Nash and Matt Wilson, I’m reminded<br />

of Gilbert and his way with an ensemble—not just because he was such a<br />

fine drummer-bandleader, but because of the atmosphere of camaraderie<br />

he created around him, because of his sheer magnetism. Not long into the<br />

article, I started to get a sense of just how fun it must be to hang out with<br />

these three ambitious guys, all of whom have their own visions and lead<br />

their own bands while managing to keep their egos in check.<br />

Drummers. Too frequently they get a bad rap they don’t deserve. But<br />

let’s face it, we need them, and we like being around them. And, in the<br />

case of my friend Gilbert, and departed legendary bandleaders such as Art<br />

Blakey and Mel Lewis, we sometimes miss them, too.<br />

DB<br />

8 DOWNBEAT November 2009

Chords & Discords<br />

time to choose new members for the Hall of<br />

Fame I hope someone remembers Red<br />

Norvo, a great musician who made enormous<br />

contributions to jazz yet somehow<br />

seems to be undervalued and overlooked.<br />

Ross Firestone<br />

randgfirestone@nyc.rr.com<br />

Philadelphia Gratitude<br />

Thank you for the great article about the<br />

Philadelphia Jazz Fair (“The Beat,” October). I<br />

can’t say enough good things about the job<br />

that Eric Fine did in researching and writing<br />

the piece. It’s great to see Jymie Merritt and<br />

Trudy Pitts receive some national recognition<br />

at this time in their careers. I first subscribed<br />

to DownBeat in 1967 as a sophomore in high<br />

school. It’s still my favorite, and the definitive<br />

magazine of record in jazz.<br />

Don Glanden<br />

Division Head, Graduate Jazz Studies<br />

The University of the Arts<br />

Philadelphia<br />

Anderson’s Decade Count<br />

It was great to see the article on Fred<br />

Anderson (September). However, the writer<br />

makes a common error in his lead for the<br />

story. Anderson didn’t enter his eighth decade<br />

on his last birthday; he began the last year of<br />

his eighth decade.<br />

The first decade of his (or anyone’s) life<br />

ended when he completed his 10th year; or<br />

when he turned 11. So, following that count,<br />

next spring, Fred Anderson will begin his<br />

ninth decade on the planet. Here’s to wishing<br />

that Fred Anderson has many more years,<br />

many more decades, as an active musician<br />

and presenter.<br />

Herb Levy<br />

herb.levy@sbcglobal.net<br />

A Teddy Wilson Treasure<br />

I love the marvelous interview Tom Scanlan<br />

did with Teddy Wilson back in 1959 and<br />

hope you continue extracting such precious<br />

treasures from the DownBeat archives<br />

(September). By the way, when it becomes<br />

Recognizing Pettiford<br />

It has been long overdue for the music industry<br />

to openly acknowledge the unequaled<br />

genius of Oscar Pettiford and his legacy as<br />

one of the masters of American classical<br />

music: jazz. Thank you, DownBeat, for<br />

addressing this miscue by finally inducting<br />

him into the DownBeat Hall of Fame (“Critics<br />

Poll,” August). Those in the mainstream<br />

music industry who profit from the achievements<br />

of talented artists have historically<br />

ostracized Pettiford from his rightful rank<br />

among the jazz masters, primarily because he<br />

refused to compromise the integrity of his<br />

music for capital gain.<br />

Jacqueline Pettiford<br />

Chicago<br />

Cohn’s Off Night<br />

With reference to Edwin Bowers of the Al<br />

Cohn Jazz Society (“Chords,” September):<br />

Cohn may well be deserving of inclusion in<br />

the Hall of Fame. But from my viewpoint, he<br />

has never come to my full attention except for<br />

the one time I saw him in Perth, Australia, in<br />

1986. He must have had an off night because<br />

the music was unremarkable, he moaned and<br />

groaned and cut the gig short when his instrument<br />

started to fall apart (decompose).<br />

On another matter, it was good to see a<br />

Mike Nock recording covered in “Woodshed”<br />

(September). Mike spent several<br />

years in the United States playing with the<br />

likes of Dave Liebman and is now the Grand<br />

Master of Australian jazz piano. In whatever<br />

format he plays, he is always interesting and<br />

entertaining.<br />

Keith Penhallow<br />

Canberra, Australia<br />

Correction<br />

The Student Music Guide (October) printed<br />

an incorrect amount for undergraduate tuition<br />

at New York University. The correct amount<br />

for music students is $38,765 per year, which<br />

includes nonrefundable registration and services<br />

fees.<br />

Saxophone professor Michael Cox should<br />

have been listed as a faculty member of<br />

Captial University in Columbus, Ohio, in the<br />

Student Music Guide.<br />

DownBeat regrets the errors.<br />

Have a chord or discord E-mail us at editor@downbeat.com.

INSIDE THE BEAT<br />

14 Riffs<br />

16 Vinyl Freak<br />

20 Caught<br />

22 Players<br />

Cuban Bridge<br />

As U.S.–Cuban<br />

relations thaw,<br />

musicians discuss<br />

what American<br />

visitors could<br />

experience on<br />

the island<br />

It has been several years since most Americans<br />

could legally visit Cuba. Now, with Cuban-<br />

Americans free to visit their birthplace, speculation<br />

is rife that President Barack Obama will<br />

soon remove the Treasury Department restrictions<br />

that block American travel to the island.<br />

While it’s too early to determine what barriers<br />

could be lifted, the two countries are making<br />

tentative steps. This September, the U.S. State<br />

Department granted performance visas to Cuban<br />

singer Pablo Milanés and composer Zenaida<br />

Romeu—the first such visas granted for Cuban<br />

musicians since 2003.<br />

Of course, some music has always flowed<br />

across borders, with Cuban musicians such as<br />

saxophonist Paquito D’Rivera, pianist Gonzalo<br />

Rubalcaba and drummer Dafnis Prieto establishing<br />

themselves in the United States, and others<br />

like Jane Bunnett and Ry Cooder importing various<br />

elements of Cuban music to North America.<br />

But what musical riches await discovery by<br />

American tourists<br />

“Some might think the music is like it was 50<br />

years ago,” said Prieto, whose work as a drummer<br />

and composer has transcended traditional<br />

clavé rhythms. “Since that time, it has grown in<br />

many different ways, and there are local styles<br />

and variations wherever you go.”<br />

“Travelers are in for some surprises,” said<br />

Bunnett, the Toronto-based reed player who has<br />

been exploring Cuban music as a tourist and<br />

improviser for almost 30 years. “Every region<br />

has some musicians who are legends in their<br />

own town. It’s a situation akin to the early<br />

1960s, when researchers and journalists started<br />

discovering blues musicians in the rural South.”<br />

One thing that is significantly different from<br />

the era when part-time players like Mississippi<br />

Fred McDowell and Skip James re-surfaced is<br />

Hilario Durán<br />

the fact that most of the musicians who remain<br />

in Cuba are highly educated and experienced in<br />

performing for a variety of audiences.<br />

“People might think the music scene is not as<br />

sophisticated as it is,” said Roberto Occhipinti, a<br />

Canadian bassist who has produced recordings<br />

by Cuban ex-pats like Prieto and pianist Hilario<br />

Durán. “There’s a real strong sense of self<br />

among the musicians. Overall, there’s a depth to<br />

the place that you don’t see in many countries.<br />

Everyone sings and everyone dances.”<br />

“Cuba is a country where music is always<br />

there, no matter what happens,” said Durán.<br />

Not only is it deeply ingrained in the everyday<br />

cultural life of many Cubans, since the<br />

Communist revolution that brought Fidel Castro<br />

to power, music has been seen as one of the few<br />

ways to ease the harsh realities of life on the<br />

island. For budding musicians, joining a salsa<br />

band can be a ticket out, if only for a carefully<br />

monitored tour or a tourist-resort gig.<br />

These days, said Occhipinti, many of the<br />

country’s jazz musicians are as plugged-in to<br />

current trends as their contemporaries outside<br />

Cuba. “Today, the young jazz players in Cuba<br />

have access to a lot more information; some of<br />

them can connect to things through the<br />

Internet, they can hear anything that’s going<br />

on. They play like they’re at the university<br />

level in their teens, and they don’t have any<br />

distractions. There’s nothing to get between<br />

them and their music.”<br />

Drummer Francisco Mela recently returned<br />

to his native country after an absence of 10<br />

years. “I was really impressed with what I<br />

heard,” he said, “particularly among the drummers.<br />

I heard a lot of powerful players who<br />

have great control of dynamics and strong conceptual<br />

ideas. The music is really starting to<br />

swing more.”<br />

For music tourists new to Cuba, Durán has<br />

some recommendations for those wanting to<br />

hear the best of what Havana has to offer.<br />

“In the Vedado area, La Zorra y el Cuervo,<br />

Café Cantante and the Jazz Café all offer good<br />

music, and you can meet the musicians, as<br />

well,” Durán said. “In Miramar, on the west<br />

side of Havana, you can go to Casa de la<br />

Musica. In the heart of the city, you can find a<br />

very famous place called Callejon de Hamel,<br />

where every Saturday they dance and sing rumbas<br />

all afternoon.”<br />

Bunnett adds two more recommendations,<br />

UNIAC—the Cuban Union of Writers and<br />

BILL KING<br />

November 2009 DOWNBEAT 13

Riffs<br />

DL MEDIA<br />

Pérez Signed: Danilo Pérez stopped by<br />

the Mack Avenue Records booth along<br />

with saxophonist Tia Fuller at the Detroit<br />

Jazz Festival over Labor Day Weekend to<br />

officially announce his joining the label.<br />

His debut Mack Avenue disc is slated for<br />

2010. Details: mackavenuerecords.com<br />

Williams Celebration: New York’s Jazz<br />

at Lincoln Center will honor Mary Lou<br />

Williams’ centennial during the coming<br />

months. Events include a Jazz For<br />

Young People Concert devoted to her<br />

music on Nov. 7, Geri Allen and Geoff<br />

Keezer joining the center’s orchestra on<br />

Nov. 13 and 14 and Williams’ manager,<br />

Father Peter O’Brien, lecturing about her<br />

life in January. Details: jalc.org<br />

Artists—which features folkloric music, and<br />

Club Tropicale, located in a former beer factory.<br />

The saxophonist and her husband, trumpeter<br />

Larry Cramer, have also travelled extensively<br />

outside Havana since 2000. Among her favorite<br />

places are the Teatro Tomas Terry in<br />

Cienfuegos, a spectacular Italianate structure<br />

built by architect Lino Sanchez Marmol in 1889,<br />

and Casa de la Trova in Santiago de Cuba,<br />

which features bolero-son on the back patio and<br />

professional dancers upstairs.<br />

Santiago’s range of traditional musical styles<br />

leads Occhipinti to draw an American parallel:<br />

“People who visit Cuba for the music have to go<br />

to Havana; that’s like New York City for musicians.<br />

Santiago is like New Orleans in the sense<br />

that it’s where a lot of the music originated. It’s a<br />

completely different vibe than anywhere else.”<br />

Like New Orleans, Santiago reflects a significant<br />

French influence, dating back to an invasion<br />

in 1553, and more recently to the wave of<br />

Haitian refugees that followed the slave revolt of<br />

1791. Another important center of Haitian influence<br />

is the central city of Camagüey, home to a<br />

10-piece a cappella choir called Grupo Vocal<br />

Desandann that Bunnett has featured on two<br />

recordings. Their close harmony and floating<br />

rhythms are substantially different than music<br />

usually associated with Cuba.<br />

Bunnett’s 2006 recording Radio Guantanamo<br />

reflected yet another strand of the country’s<br />

music little heard outside of the island.<br />

“Changüi is the funkiest music I’ve heard<br />

there,” she said. “It’s highly syncopated and<br />

interactive, and the bongos improvise, unlike the<br />

congas in most Cuban music.”<br />

“Anyone who thinks they know Cuban<br />

music, based on what they’ve heard over the<br />

past 20 years, is wrong,” said Occhipinti.<br />

“People don’t realize things like the huge<br />

Jamaican influence that exists in central Cuba,<br />

for example, or the fact that the Buena Vista<br />

Social Club only represents a style that’s prevalent<br />

in Santiago de Cuba.”<br />

Mela believes that American tourists are in<br />

for a great time when they are finally allowed to<br />

come to Cuba. “Everybody’s going to take them<br />

to the best places, and it’s going to be scary.<br />

There are a lot of hungry musicians waiting to<br />

show what they’ve got.”<br />

Among the hungry and talented, Durán<br />

points to pianists Rolando Luna and Harold<br />

Lopez-Nusa, guitarist Jorge Luis Chicoy and<br />

drummer Oliver Valdes.<br />

When the borders open, foreign audiences<br />

will also be delighted to discover musicians<br />

like Giraldo Piloto, a muscular, exuberant<br />

drummer in his mid-40s who is reminiscent of<br />

Billy Cobham in his Mahavishnu Orchestra<br />

years, and, Miguel Maranda, a Jaco Pastoriusinfluenced<br />

bassist who simultaneously plays<br />

percussion.<br />

“Cuba is such a deeply cultural place,” said<br />

Prieto, “that people are going to be able to see<br />

musical distinctions wherever they go.”<br />

—James Hale<br />

Brubeck Honored: Dave Brubeck will<br />

become a Kennedy Center Honoree at<br />

a ceremony on Dec. 6. The gala at the<br />

New York cultural institution will be<br />

broadcast on CBS on Dec. 29.<br />

Details: kennedy-center.org<br />

Lofty Sounds: New York radio station<br />

WNYC and National Public Radio affiliates<br />

will begin airing tapes that were<br />

made in photographer and jazz fan W.<br />

Eugene Smith’s loft during the ’50s and<br />

’60s. Premiering on Nov. 16, these tapes<br />

include rehearsals and unguarded<br />

moments featuring Thelonious Monk,<br />

Zoot Sims and Jim Hall. Details: wnyc.org<br />

Sinatra Vino: Frank Sinatra’s estate<br />

has released a limited-production Napa<br />

Valley cabernet sauvignon called “Come<br />

Fly With Me.” Details: sinatra.com<br />

RIP, Connor: Singer Chris Connor died<br />

of cancer in Toms River, N.J., on Aug.<br />

29. She was 81. Known for her cool,<br />

low-vibrato style, Connor sang with the<br />

Stan Kenton band, before going solo<br />

and recording such hits as “All About<br />

Ronnie” and “Trust In Me.”<br />

DB<br />

Saxophonist<br />

Nathanson Turns<br />

On Poetic Muse<br />

Best known for his work with The Jazz<br />

Passengers, saxophonist Roy Nathanson<br />

has emerged with a book of poems,<br />

Subway Moon (Buddy’s Knife Editions).<br />

It coincides with an album of the same<br />

name (yellowbird records) with his band<br />

Sotto Voce.<br />

“I would alternate from watching people<br />

to somehow letting my mind take its<br />

own ride,” Nathanson said. “I started writing and<br />

reading tons of poetry on the subway traveling<br />

from Brooklyn to my teaching job in Manhattan,<br />

and found that this was the only place I could<br />

write. It was a whole other format of improvisation<br />

for exploring emotional and philosophical<br />

territory—a different way to dance through the<br />

edges of my history other than playing my horn.<br />

“Eventually, I had this manuscript,” he continued.<br />

“Then, some time in 2006 or ’07, I got a<br />

grant from Chamber Music America to write a<br />

full length ‘song cycle’ around these poems for<br />

The Jazz Passengers. Werner Aldinger of<br />

enja/yellowbird Records in Munich wanted to<br />

put out the CD and said he knew Renate Da Rin,<br />

Roy Nathanson<br />

who had a new small press in Koln that had just<br />

published writing by Henry Grimes and William<br />

Parker. The company had this great name,<br />

Buddy’s Knife Editions—for Buddy Bolden—<br />

and the plan was to put them both out together.”<br />

During the course of his career, Nathanson<br />

said he “sort of organically drifted into writing<br />

poetry. When I joined The Lounge Lizards I’d<br />

been living for years in the East Village and<br />

was as much a part of the ‘downtown’ theater<br />

world as the jazz world—and they were totally<br />

different. The Passengers was a way of melding<br />

these worlds, and the surreal songs/sketches<br />

I wrote or appropriated acted as an engine to<br />

achieve that end.”<br />

—John Ephland<br />

JANE MEYERS<br />

14 DOWNBEAT November 2009

DOWNBEAT ARCHIVES<br />

Freedom, Honesty<br />

Defined Rashied Ali<br />

Rashied Ali, who helped expand the drummer’s<br />

role through his polyrhythmic work with John<br />

Coltrane and many others since the mid–’60s,<br />

died of a heart attack in New York on Aug. 12.<br />

He was 76.<br />

“His technique poured from all kinds of<br />

places,” said bassist Henry Grimes. “Most of the<br />

time, it was unbelievable.”<br />

While Ali remains best known for stretching<br />

far beyond standard jazz swing time on such<br />

albums as Coltrane’s Meditations (where he<br />

played alongside Elvin Jones) and Interstellar<br />

Space (a sax-drums duo), his early years were<br />

more straightforward. Born Robert Patterson, he<br />

grew up in Philadelphia, studied under Philly<br />

Joe Jones, played r&b with singers like Big<br />

Maybelle and served in an army band during the<br />

Korean War.<br />

In the early ’60s, Ali moved to New York<br />

and became engrossed in the burgeoning freejazz<br />

scene, performing with Albert Ayler,<br />

Archie Shepp and Pharoah Sanders before joining<br />

Coltrane in 1965.<br />

After Coltrane’s death two years later, Ali<br />

spent time in Europe, but returned to New York<br />

in the early ’70s and started the performance<br />

space Ali’s Alley in 1973, which remained open<br />

for six years. He also formed Survival Records,<br />

which continues to release his material.<br />

By the early ’90s, Ali began re-examining his<br />

work with Coltrane and Ayler through the group<br />

Prima Materia.<br />

“The way Rashied would play the drum set<br />

came out of the jazz tradition,” said Prima<br />

Materia saxophonist Allan Chase. “It had a<br />

swing, but when he was playing free, there were<br />

multiple things going on. It was like looking<br />

through a kaleidoscope—broken up, but everything<br />

had its integrity.”<br />

That integrity included his bandleading,<br />

according to Chase.<br />

“He was very funny, mentoring, energetic,<br />

not at all shrouded in mystery,” Chase said.<br />

“Rashied looked us in the eye and could be complimentary,<br />

critical. You could tell he was telling<br />

the truth.”<br />

—Aaron Cohen<br />

November 2009 DOWNBEAT 15

By John Corbett<br />

United Front<br />

Path With A Heart<br />

(RPM RECORDS, 1980)<br />

MICHAEL JACKSON<br />

United Front is usually cited as<br />

one of the founding ensembles<br />

of the new Asian-American jazz<br />

movement in the 1980s. The<br />

San Francisco quartet is best<br />

known for its work with drummer<br />

Anthony Brown, who<br />

joined in 1981, but they had<br />

already made this great record<br />

by then with Carl Hoffman in<br />

the percussion role. The rest of<br />

the band was as it remained,<br />

with bassist Mark Izu, saxophonist<br />

Lewis Jordan and<br />

trumpeter George Sams. I was<br />

a freshman in college, working<br />

the graveyard shift at WBRU in<br />

Providence, R.I., when my jazz<br />

buddies there hipped me to this<br />

wonderful, now woefully scarce item. It<br />

was in heavy rotation from midnight to 3<br />

a.m. for a few seasons.<br />

Twenty-eight years since I first heard it,<br />

Path With A Heart endures the test of<br />

time. Its working model is certainly the Art<br />

Ensemble of Chicago, replete with intrusions<br />

of “little instruments” played by the<br />

ensemble members. Hoffman’s “Feel<br />

Free” starts with ratchet noises, arco<br />

bass, bicycle horns and sparse altissimo<br />

horn squeaks and multiphonic honks,<br />

before Izu kicks into the buoyant groove<br />

underpinning the sweet and sour tune to<br />

his delightful “Don’t Lose Your Soul,”<br />

which includes an awkward time shift<br />

much like those on some AEC’s classics.<br />

The more swing-based pieces have that<br />

tasty off/on-ness that I associate with<br />

Roscoe Mitchell and gang, as well as Fred<br />

Hopkins (whose playing Izu often recalls).<br />

No idea where he went, but Hoffman<br />

sounds perfectly at home here, breaking<br />

up a groove or bolstering it. Though they<br />

don’t have household name recognition,<br />

Sams and Jordan are worthy figures, conversant<br />

in the Ornette Coleman-derived<br />

post-bop vocabulary, deep in the thick of<br />

the milieu of “new architecture” that the<br />

Midwest’s AACM and Black Artists Group<br />

had so copiously spread around the globe<br />

starting in the late ’60s. Sams’ “March In<br />

Ostinato” starts the B-side with a very<br />

Anthony Braxton-ish composition, the<br />

hyper-extended theme bounding off<br />

Hoffman’s press rolls.<br />

These fellows had their own thing, too,<br />

bringing in pan-Asian instruments and<br />

ideas. With its sheng and nobbed gongs,<br />

“Forgotten Spirits” has a gagaku element,<br />

which was certainly unusual at the time,<br />

anticipating the full-on Asian-American<br />

jazz developments from Jon Jang, Glenn<br />

Horiuchi and Fred Ho, signaled by the first<br />

Asian-American Jazz Festival in San<br />

Francisco, which was held in 1981. RPM<br />

was an artist-run label organized by<br />

United Front; pianist Jang’s LPs Jang<br />

(which featured the quartet) and Are You<br />

Chinese Or Charlie Chan (which featured<br />

members of the group), as well as the<br />

foursome’s Ohm: Unit Of Resistance, were<br />

released on RPM in the years following<br />

Path With A Heart, which was the label’s<br />

debut. RPM was defunct by the end of the<br />

’80s and much of their activity shifted to<br />

Asian Improv Records. United Front also<br />

recorded for the German SAJ label, a sister<br />

to Free Music Productions. This release<br />

remains incredibly rare, so much so that a<br />

Google search barely yields anything. If<br />

that’s the measure of things that are truly<br />

obscure nowadays, this album doesn’t<br />

deserve to be so hidden from view. DB<br />

E-mail the Vinyl Freak: vinylfreak@downbeat.com<br />

More than 60 years separate the first jazz recording in 1917 and the introduction of the CD in the early ’80s.<br />

In this column, DB’s Vinyl Freak unearths some of the musical gems made during this time that have yet to be reissued on CD.<br />

16 DOWNBEAT November 2009

COURTESY OF BBC AMERICA<br />

Julian Barratt as<br />

Howard Moon<br />

British Comedian Brings Jazz<br />

Background to Hit TV Series<br />

The premise of the popular British comedy series, “The Mighty Boosh,”<br />

may be familiar: Earnest amateur jazz keyboardist Howard Moon (Julian<br />

Barratt) tries to make his glam rocker friend Vince Noir (Noel Fielding)<br />

interested in more serious music. But the adventures that spin out from<br />

these conversations become anything but standard. They can involve<br />

demonic grandmothers inviting Armageddon. Usually, Moon and Noir’s<br />

rescue depends on a drug-addicted shaman and a talking gorilla.<br />

No matter how fantastical these journeys become, they retain one sense<br />

of grounded realism, which stems from Barratt’s actual past as a jazz guitar<br />

prodigy. He and Fielding base their musical differences in “The Mighty<br />

Boosh” on their own clashes (both co-write the show).<br />

“When Noel and I met, he never knew anyone who was into jazz—he<br />

lived in a different sort of world than mine,” Barratt said. “So he was<br />

always taking the mickey out of me for liking it, and we found that amusing,<br />

so we ramped up that dynamic.”<br />

Barratt’s musical world formed as he grew up in Leeds, and his parents<br />

took him to see John Scofield, Herbie Hancock and Weather Report when<br />

they performed in England. Around that time, he became a serious young<br />

musician and attended the late British jazz trumpeter Ian Carr’s summer<br />

programs. Still, even after touring with such bands as the jazz-funk fusion<br />

Groove Solution, Barratt gave up music for comedy while attending the<br />

University of Reading.<br />

When Barratt and Fielding teamed up in the ’90s, their stage show<br />

turned into a radio program and then “The Mighty Boosh” debuted on<br />

BBC television in 2004. This year, the Adult Swim cable network picked<br />

it up in the United States and the series’ three volumes are now available<br />

on DVD in the U.S. (through BBC America).<br />

Jazz musicians—real and fictional—are name-checked throughout the<br />

series, and improvisation runs throughout Barratt and Fielding’s comic<br />

style. Barratt adds that when he composes the songs for each episode, narratives<br />

require him to draw from a wide musical background.<br />

“If Noel comes up with a character, and it’s a transsexual merman who<br />

preys on sailors, the music would be a strange Rick James fusion,” Barratt<br />

said. “It’s funny to juxtapose sea creatures and funk.”<br />

In the future, Barratt would like to delve deeper into jazz’s comic tradition,<br />

mentioning Slim Gaillard as an example. A few prominent American<br />

jazz musicians are already fans of “The Mighty Boosh,” including<br />

Scofield, who got turned on to the program from his daughter.<br />

“I thought the episodes were hilarious,” Scofield said. “There were so<br />

many references to jazz in their dialogues, and I knew right away that<br />

someone there was a real jazz aficionado with a wry sense of humor.”<br />

Scofield and Barratt have since become friendly, which the one-time<br />

jazz student sounds like he can hardly believe.<br />

“All these people who are my heroes from a previous life,” Barratt<br />

said, “I’m getting to hear from them in this world.” —Aaron Cohen

Caught<br />

Umbria Streamlines,<br />

Still Takes Risks<br />

George Lewis<br />

Craftsmanship and proportion infuse the culture of Perugia, home of the<br />

Umbria Summer Jazz Festival, which ran July 10–19 this year. Festival<br />

president Carlo Pagnotti rose to the challenge of operating under a tighter<br />

budget than in previous years while maintaining the festival’s high standard<br />

of refinement.<br />

Pagnotti used only one theater for indoor events. But he left intact the<br />

customary mix of first-rate blues, r&b, New Orleans and world music acts<br />

who perform day-long, free outdoor concerts, among them singer-songwriter-guitarist<br />

K.J. Denhert and her top-shelf New York band as well as<br />

the intense soul singer Vaneese Thomas. Vocalist Allan Harris and his<br />

trio, performing Nat Cole repertoire, also played outdoors. Indeed, Cole<br />

was a festival trope—George Benson, on tour with an orchestra-supported<br />

Cole extravaganza, replicated the master’s every inflection and tonal<br />

nuance. Cole’s brother Freddy transformed the Hotel Brufani into an<br />

Italian version of Bradley’s for his 10-night run, which was this year’s<br />

only extended residency (multiple extended residences had been a trademark<br />

of past festivals).<br />

Other main stage bookings included adult pop and mainstream jazz.<br />

James Taylor brought a great band, including Steve Gadd and Larry<br />

Goldings. Burt Bacharach presented a so-cheesy-it-was-hip self-retrospective.<br />

On the jazz side, Chick Corea and Stefano Bollani performed a spontaneously<br />

improvised duet on the standard repertoire. Alto saxophonist<br />

Francesco Cafiso augmented Jazz at Lincoln Center’s swinging, pan-stylistic<br />

set; the Sicilian wunderkind saxophonist wailed on Sherman Irby’s<br />

surging arrangement of Lou Donaldson’s “Blues Walk.” With his own<br />

quartet, Cafiso projected a lyric voice informed by Charlie Parker, Lee<br />

Konitz and Phil Woods alongside such ’70s radicals as Anthony Braxton<br />

and Julius Hemphill.<br />

Also representing Italy, pianist Enrico Pieranunzi played original compositions<br />

with his quintet, and drummer Roberto Gatto rearranged ’70s<br />

British prog rock for octet. Alto and soprano saxophonist Rosario Giuliani<br />

and pianist Dado Moroni blew soulfully in Joe Locke’s chamber trio.<br />

Trumpet veteran Enrico Rava helmed a post-boomer quintet with trombonist<br />

Gianluca Petrella.<br />

Among the other main acts, Dave Douglas presented Brass Ecstasy, a<br />

Lester Bowie homage comprising well-wrought originals that extracted<br />

maximum tonal color from French horn player Vincent Chancey, trombonist<br />

Luis Bonilla and tubist Marcus Rojas, propelled by inventive<br />

rhythms and textures from Nasheet Waits, channeling an inner Max<br />

Roach. Road-weary John Scofield kicked out the jams with his Piety<br />

Street quartet. Richard Galliano presented nuevo tango and beyond with<br />

United Nations quartet.<br />

A pair of experimental projects took a certain courage to book, especially<br />

considering Italy’s troubled economy. A three-day, six-concert presentation<br />

by Chicago’s cohesive 21-piece AACM Great Black Music<br />

Ensemble under the putative leadership of George Lewis featured compositions<br />

by AACM second- and third-wavers Lewis, Nicole Mitchell,<br />

Douglas Ewart, Mwata Bowden and Ernest Dawkins, and by fourthwavers<br />

Tomeka Reid and Renee Baker. A choir of four perpetually intune<br />

voices-as-instruments, Reid and Baker’s cello and violin, Lewis’<br />

electronics, two basses and a trapset-and-percussion combination seamlessly<br />

integrated with a five-saxophone, three-trumpet, two-trombone big<br />

band and exploited the unit’s singular instrumentation. The bacchanalian<br />

end-of-festival event packed Piazza 4 Novembre, as a throng of revelers<br />

grooved to Puerto Rican master conguero Giovanni Hidalgo and Cuban<br />

master trapsetter Horacio “El Negro” Hernandez alongside a large ensemble<br />

of young Kenyan hand drummers and dancers. —Ted Panken<br />

GIANCARLO BELFIORE–UMBRIA JAZZ<br />

Copenhagen Jazz Festival Revisits History While Embracing Youth<br />

The Copenhagen Jazz Festival is a varied<br />

Chick Corea<br />

extravaganza that leans away from the summer<br />

festival blockbusters and makes sure to<br />

demonstrate diversity. That was particularly<br />

the case this year for its 31st edition, which<br />

ran July 3–12.<br />

The city’s must-visit list includes the Jazz<br />

Cup, home of an impressive music store, jazz<br />

club and also headquarters of the Danish<br />

magazine Jazz Special. On a Saturday afternoon<br />

during the festival, one could catch the<br />

nimble and thoughtful pianist Peter<br />

Rosenthal’s trio and then venture over to the<br />

dreamily lavish Frederiksburg Garden, where<br />

We Three—saxophonist David Liebman,<br />

bassist Steve Swallow and drummer Adam<br />

Nussbaum—dished up lyricism and feistier energies in a garden party-like<br />

setting as a peacock strolled the grounds.<br />

Fascinating and cool young Danish singer Maria Laurette Friis presented<br />

her distinctive indie-pop in the hip, renovated old fishing vessel MS<br />

Stubnitz—retooled as a floating cultural center with an experimental<br />

KRISTOFFER POULSEN<br />

music bent. But Friis’ greater artistic coup<br />

was a tribute to Billie Holiday’s final<br />

album, Lady In Satin. Via Friis, Lady<br />

Day’s innate melancholic sublimity was<br />

given a surprisingly bewitching fresh<br />

twist—something akin to an indie<br />

shoegazer approach.<br />

A different flavor of introspective<br />

Scandinavian musical demeanor marks<br />

the special touch of seasoned Danish<br />

trumpeter Jens Winther, who played outdoors<br />

by a lake in Ørstedsparken—one of<br />

several tranquil parks dotting this uncommonly<br />

beautiful and green city.<br />

Among official festival headliners,<br />

Chick Corea showed up for a solo concert<br />

early in the festival’s schedule, and a Nina Simone tribute included Dianne<br />

Reeves and Angelique Kidjo. In the delightfully bizarre context of the<br />

famed, kitsch-flecked Tivoli Gardens, Yusef Lateef’s Universal Quartet<br />

combined regular ally Adam Rudolph on percussion alongside Danish<br />

percussionist Kreston Osgood and dazzling trumpeter Kasper Tranberg.<br />

20 DOWNBEAT November 2009

Towards festival’s end, Dee Dee Bridgewater performed her easier-does-it<br />

charts with the fine Tivoli Big Band and Orchestra, outdoors in the<br />

Gardens, disseminating musical goodness into many corners of the<br />

sprawling compound.<br />

But the most culturally and indigenously significant concert this year, if<br />

not the greatest musical success, involved a certain historic Danish-<br />

American connection. Danish trumpeter Palle Mikkelborg, who wrote the<br />

moody and memorable work AURA for Miles Davis 25 years ago<br />

(released as a two-disc album by Columbia in 1989), was commissioned<br />

to revisit the extended composition with a fresh conceptual attitude. The<br />

result, realized by a large and multi-limbed ensemble, was a strangely<br />

uneven but ultimately intriguing suite. Many of the meeker passages were<br />

laid out in the first half, including a goofy disco take on “What’s New,”<br />

which brought to mind Herb Alpert more than late-era Davis. But the writing<br />

got tougher, more complex and more evocative as the program progressed<br />

and the sundry facets of the chamber ensemble-meets-big band<br />

group were put to good use.<br />

In that more muscular and enigmatic finale, we could, in fact, easily<br />

imagine Davis’ sonic voice doing its artistic bidding. —Josef Woodard<br />

Saxophonist Allen Slyly<br />

Stretches Out at Vanguard<br />

J.D. Allen<br />

J.D. Allen sings on his tenor<br />

saxophone. No hijinks, mind<br />

games, bravado—just song,<br />

lyrically intact and rhythmically<br />

invigorating. In a nutshell,<br />

that’s what Allen triumphantly<br />

showcased on Aug. 12, the<br />

second night of his weeklong<br />

debut at New York’s Village<br />

Vanguard with simpatico band<br />

mates Gregg August on bass<br />

and Rudy Royston on drums.<br />

In an alluring 70-minute set,<br />

Allen fluidly weaved through<br />

14 tunes—all short, but pleasing<br />

takes devoid of lengthy<br />

wandering. This was in keeping<br />

with his most recent trio<br />

CD, Shine!, where the numbers<br />

range from two minutes to just longer than five.<br />

On the gleefully lopsided swing “Id,” introduced with a sly bow of<br />

respect to Sigmund Freud, Allen bellowed with a fresh, danceable sensibility.<br />

Throughout the set, he rarely overblew, even on the cooking “East<br />

Boogie,” where he extended his solo, and on the upbeat “Titus” where he<br />

sped through a torrent of tenor notes. Allen also avoided getting caught up<br />

in a whirlwind of improvisation that would’ve lost bearing to the song.<br />

Cases in point: the lyrical meditation “Se’Lah” and the reflective, hushed<br />

cover of the standard “Stardust,” which was a showstopper in its quiet<br />

beauty.<br />

When Allen slipped out of the spotlight, he crouched in the shadows at<br />

the back of the stage near the velvet curtains and comped for August’s<br />

closely imagined solos. Royston was spotlighted on “Conjuration Of<br />

Angels” (composed by Butch Morris) where his spanked and rolling<br />

rhythms drove the proceedings.<br />

Mainstream jazz sometimes cloaks itself with esotericism, but Allen<br />

steered clear of that at the Vanguard. He chose an organic path where he<br />

became engaged, had his say—stretching economically and to the point—<br />

then slid out. It wasn’t that he didn’t have much to express; it’s more that<br />

Allen spread his expression across the set in a multitude of songs versus an<br />

immature—or insecure—saxist blowing his wad on boring multiple-chorus<br />

exhibitionism.<br />

—Dan Ouellette<br />

JOHN ROGERS/WGBO<br />

November 2009 DOWNBEAT 21

Players<br />

JACK VARTOOGIAN/FRONTROWPHOTOS<br />

E.J. Strickland ; Search and Explore Mission<br />

“When I first got to New York, I was very aggressive on the instrument,”<br />

said E.J. Strickland of his drumset approach when he entered the fray in<br />

New York City a decade ago.<br />

Now 30, Strickland, whose career over that duration splits evenly<br />

between traditional and more exploratory approaches to jazz, would learn<br />

lasting lessons on “how to support more and not be overbearing” from his<br />

various colleagues and employers. These include his identical twin,<br />

Marcus Strickland, as well as Russell Malone, Ravi Coltrane, Cassandra<br />

Wilson, the various members of the New Jazz Composers Octet and, more<br />

recently, the Night of the Cookers Sextet with Billy Harper and Charles<br />

Tolliver.<br />

“Russell was the first leader who told me I was overplaying, not really<br />

listening for what I could do for his group,” Strickland said. “He said,<br />

‘You don’t want to be too hip, because two hips make an ass.’ That stuck<br />

with me. The instrument itself is not designed to be understated. I needed<br />

to find a way to do what the drummers I respect did—to transcend the<br />

instrument, be able to play fast figures and complex rhythms with a lot of<br />

energy, but at a volume that’s balanced with the group. Finding that balance<br />

on the kit is hard to do.”<br />

Strickland demonstrates these investigations on his debut release, In<br />

This Day (StrickMusic). He propels his tenor saxophonist brother, alto<br />

saxophonist Jaleel Shaw, pianist Luis Perdomo, bassist Hans Glawischnig<br />

and conguero Pedro Martinez through a suite of melodic originals that<br />

blend highbrow jazz harmony with rhythms that morph in and out of<br />

swing and straight-eighth feels along with more overtly African and Afro-<br />

Caribbean sources. The horns sing in continual dialogue with the leader,<br />

who focuses less on bringing his technical legerdemain to the forefront<br />

than on deploying it to enhance the ensemble sound.<br />

“I didn’t have a clear idea how I wanted my group to sound,”<br />

Strickland said. “I was always writing, and could see that there was something<br />

developing with my own compositional voice. But I wasn’t sure<br />

what instruments I wanted to use. Some of my songs are very syncopated,<br />

so I wanted that percussive feeling in the horn parts. I grew up with<br />

Marcus, watched his rhythmic sensibility grow and develop, and that led<br />

me to want two mutually sensitive horn players who bounce off of each<br />

other rhythmically.”<br />

Educated in the rudiments by his father—a classical percussionist and<br />

proficient r&b and funk drummer—Strickland developed his ears during<br />

adolescence and teen years through countless hours playing duets with his<br />

brother. “It helped me focus on listening, to surrender to the ideas you’re<br />

hearing back towards you, as opposed to trying to force ideas to come<br />

out,” he said.<br />

While attending the New School in New York, Strickland—by then<br />

under the deep influence of Elvin Jones, Roy Haynes and Jeff Watts—<br />

studied with an all-star cohort of teachers, among them Joe Chambers (“he<br />

wanted me to respect the origins of certain rhythms”), Ralph Peterson (“he<br />

helped me develop my power and technique”), Carl Allen (“he focused on<br />

developing a beautiful sound on the kit”), Jimmy Cobb (“tips on the ride<br />

cymbal”) and Lewis Nash (“we worked on brush technique, timekeeping,<br />

soloing ideas”).<br />

“I grabbed different things from everybody,” Strickland said. “It was a<br />

perfect place to open me up. Everyone around me was into so many different<br />

things, and I got into those things by hanging around them and<br />

going to shows they were into.”<br />

This year, Strickland further displayed the increasing clarity of his<br />

drum conception on Ravi Coltrane’s open-ended quartet session, Blending<br />

Times (Savoy), and on his brother’s concurrent releases, Of Song (Criss<br />

Cross) and Idiosyncracies (StrickMusic).<br />

“Both groups have allowed me to be myself,” Strickland said. “Ravi<br />

gave me a lot of freedom, but he also pushed me to think out of the box, to<br />

use different feels, to search for something different.<br />

“Our open-mindedness is due to the pioneers—John Coltrane and<br />

Miles Davis were two of them—who had the courage to explore areas that<br />

others said they couldn’t,” he continued. “They opened up everything for<br />

us—we weren’t afraid to journey further into other genres, feels and<br />

rhythms. It was a natural progression. People broke cracks in the ceiling,<br />

and now the ceiling is broken. Almost everything that’s coming out today<br />

is a fusion of stuff, and some of the other genres are starting to incorporate<br />

more jazz into their thing. We think we’re respecting the tradition by continuing<br />

to search and explore.”<br />

—Ted Panken<br />

22 DOWNBEAT November 2009

Caption<br />

MARK SHELDON<br />

Aram Shelton ;<br />

Bay Area’s Chicago Ambassador<br />

Four years after reedist Aram Shelton left Chicago to resettle in<br />

Oakland, he remains inextricably linked to the Midwest. Along with<br />

studying electronic music at Mills College and working in Bay Area<br />

bands, he shuttles between the two cities because of what he calls “frustration<br />

with not having a band that can play all the time.”<br />

“The thing about playing with good musicians is that they’re always<br />

in demand,” Shelton said. “It’s hard to say, ‘Hey, can you do just this<br />

one band’ It’s not going to happen.”<br />

This year, his Singlespeed Music label has released two albums<br />

recorded with cohorts from both scenes, one by his free bop Ton Trio<br />

called The Way, and another all-improvised session, Last Distractions.<br />

Shelton also still works with Arrive, Jason Adasiewicz’s Rolldown and<br />

the Fast Citizens, all of them based in Chicago.<br />

“I get a lot out of playing with the musicians here, and for all of us to<br />

succeed, we need to keep these bands together and growing,” he said.<br />

“I’m also glad that the folks here allow me to come back and merge<br />

back into the scene so easily.”<br />

The Palm City, Fla., native moved to Chicago after earning his saxophone<br />

degree at the University of Florida in Gainesville in 1999. He<br />

formed the trio Dragons 1976 with drummer Tim Daisy and bassist<br />

Jason Ajemian, but as the combo started attracting attention for its first<br />

album his associates became increasingly busy with other commitments.<br />

Despite Shelton’s own steady playing opportunities in Chicago, better<br />

weather and other opportunities beckoned in California.<br />

“I wanted to explore the electronic side of what I was doing, and<br />

Mills was good because I was able to keep working on what I’d been<br />

doing, but also to get a degree for it and to learn more.”<br />

Shelton learned about recording, but he also immersed himself in<br />

Max/MSP sound processing. “I focused my work on electroacoustic<br />

pieces that are centered around extending the sounds of acoustic instruments<br />

via computer-based electronics and a technique I have named<br />

Phrase Modification, where phrases played on acoustic instruments are<br />

recorded and played back, but rearranged to create new instances.<br />

“An advantage I find in the Bay Area is that I can play more gigs<br />

with the same group,” he continued, “which allows the music to develop<br />

more, a side effect of the smaller scene.” Shelton’s just formed a new<br />

trio with drummer Weasel Walter and bassist Devin Hoff, while Fast<br />

Citizens recently released Two Cities (Delmark). Although Shelton’s<br />

work with electronics doesn’t figure into the ebullient music of Fast<br />

Citizens, it does reflect a commitment to eschewing endless strings of<br />

solos sandwiched by theme statements.<br />

Despite ongoing work with Chicagoans, Shelton seems content in<br />

Oakland. He mentioned that on the first Dragons 1976 European tour<br />

people would always ask about Chicago. “I was living on Oakland and<br />

Ajemian was living in New York,” he said. “It reinforced the idea that I<br />

didn’t need to be in one place.”<br />

—Peter Margasak<br />

November 2009 DOWNBEAT 23

Players<br />

Sunny Jain ;<br />

Personal Ragas<br />

In leading the band Red Baraat, drummer<br />

Sunny Jain finds himself standing<br />

in front of a half-dozen horn players<br />

and two percussionists. Rather than<br />

playing a trap set, he strikes the barrelshaped<br />

drum strapped across his<br />

chest. The two-headed bhangra dhol<br />

originated from India; it serves as the<br />

focal point of an ensemble Jain likens<br />

to a New Orleans brass band steeped<br />

in South Asian music.<br />

Red Baraat and the more conventionally<br />

configured Sunny Jain<br />

Collective place the drummer in the<br />

burgeoning vanguard of Indian-<br />

American jazz musicians. Though<br />

the groups differ stylistically, their<br />

respective missions remain the same:<br />

to create a hybrid not only reflecting<br />

Jain’s music background, but also his<br />

heritage.<br />

Jain’s parents emigrated around<br />

1970 from North India. Jain, who<br />

grew up in Rochester, N.Y., earned<br />

music degrees from Rutgers University<br />

and New York University. While<br />

Jain holds the bop tradition in high<br />

regard, he has no desire to revisit the era. He looks beyond Indian music,<br />

as well.<br />

“To just play jazz music straight-up like Philly Joe Jones was great for<br />

an educational purpose,” Jain said in his Brooklyn, N.Y., home. “But it<br />

wasn’t me. To play like Zakir Hussain on the drum set isn’t like me,<br />

either: I’m not a tabla player, I didn’t grow up in India and I didn’t grow<br />

SEBNEM TASCI<br />

Pedro Giraudo ; Shuffle Resistant<br />

Bassist and composer Pedro Giraudo fears that with the arrival of the iPod and the<br />

dreaded ringtone, people are becoming less tolerant of extended works, especially<br />

those with specific song sequencing.<br />

“The iPod was a great invention, but on the other hand, everything becomes<br />

background music,” said Giraudo, the leader of a 16-piece jazz orchestra that<br />

performs regularly at New York’s Jazz Gallery. “Recorded music was an<br />

amazing invention, but sometimes it takes away the experience of listening and<br />

focusing. I don’t know how many people actually sit down, listen and enjoy a<br />

CD nowadays.”<br />

While Giraudo is conscientious of making some concessions for his audience<br />

regarding some of its waning attention span, he is by no means giving in to technology’s<br />

whim. His new disc, El Viaje (PGM Music), affords an opulent listening<br />

experience of modern, orchestral jazz, brimming with passionate improvisations,<br />

deliberate contrapuntal melodies and plush harmonies. Indeed, some of the compositions<br />

would be considered long: The title track approaches the 20-minutes<br />

mark. Giraudo insists that El Viaje proceeds in such a purposeful manner that it<br />

would discourage iPod shuffling.<br />

“I put so much effort in deciding the song sequence. I’m quite sure that Duke<br />

Ellington really sat down and thought about things like this,” he said.<br />

Like Ellington, Giraudo, who refers to his 16-piece ensemble as a chamber jazz<br />

orchestra rather than a big band, writes melodies with specific musicians in mind.<br />

“Chamber ensemble usually refers to music that has one person per instrument,”<br />

Giraudo said. “So I think about each person in the ensemble playing. I’m<br />

ERIN O’BRIEN<br />

24 DOWNBEAT November 2009

up playing Hindustani classical music.<br />

“But what is me,” he continued, “is a confluence of these backgrounds<br />

and traditions kind of flowing together. And it’s not strictly Indian music<br />

and jazz. It’s Brit pop like New Order and the Cure. It’s Radiohead, it’s<br />

Smashing Pumpkins.”<br />

At a summer gig in a bar in Queens, Jain performed with pianist Steve<br />

Blanco, whose repertoire spans pop songs from the 1970s and 1980s. The<br />

trio’s reading of Pink Floyd’s “Us And Them” veered from trance-like to<br />

volatile. The Police’s “Synchronicity” included sharp tempo shifts and the<br />

song’s simple structure lent itself to the group’s penchant for free playing.<br />

“We can’t deny that groove we grew up with—the straight eighth-note<br />

feel—whether it’s rock or funk,” Jain said between sets. “You still need to<br />

know that vocabulary those bop masters laid out. But to play period music<br />

is to not be myself at this moment in time.”<br />

Jain recorded Red Baraat last fall, and will release an album early next<br />

year. The Sunny Jain Collective has issued several albums, and Jain has<br />

begun recording The Taboo Project, which will feature a cycle of six<br />

songs commissioned by Chamber Music America. Jain premiered the<br />

music in December 2007 at Joe’s Pub in Manhattan. Jain adapted the<br />

work of contemporary poets writing in Hindi, Urdu and English. The<br />

poets include Ali Husain Mir and Ifti Naseem, who tackle religious strife,<br />

domestic violence and homosexuality.<br />

“These are issues that are not comfortably and openly discussed or<br />

dealt with in South Asia. At the same time these are universal issues,”<br />

Jain said.<br />

In addition to original music, Jain wants to translate India’s music traditions<br />

to the confines of a jazz group. This songbook encompasses not<br />

just the ragas (melody) and tals (rhythm) common in Hindustani and<br />

Carnatic music, but also the music of Bollywood, religious songs and<br />

bhangra, a folkloric music in the Punjab region of both India and Pakistan.<br />

Jain compares this crosspollination to the manner in which jazz musicians<br />

adapt music from Broadway and Tin Pan Alley.<br />

“But at the end of the day, it’s not meant to be overt,” he said. “If I<br />

wanted to do that, I would hire a tabla player, I would hire a sitar player and<br />

I would say, ‘Hey, this is Indian jazz.’ There’s a few of us doing this here in<br />

New York, and we all have our own approach of expressing our cultural<br />

identity as Indian-Americans. This is my approach.” —Eric Fine<br />

lucky to have the same musicians for a very long time. Some of the guys<br />

have been in the band since 2000. We’ve developed a language within<br />

the band.”<br />

Hailing from Cordoba, Argentina, and born to a symphonic orchestraconducting<br />

father, it comes as no surprise that European classical music<br />

and tango also inform Giraudo’s musical language.<br />

“I’m not sure if you’ll call my music avant-garde, but in terms of the<br />

tango tradition, my music falls into the very modern tango,” Giraudo said.<br />

“There are some tango elements in my music, but they are very subtle. I<br />

think the most Argentinean element is the sense of nostalgia.”<br />

Giraudo trained early on classical violin and piano. As a teenager he<br />

strapped on the electric bass, initially playing rock and pop, which eventually<br />

led him to jazz. “Since I was in South America, most people’s concept<br />

of jazz is more jazz-fusion, so I was familiar with Chick Corea’s Elektric<br />

Band and Mike Stern.”<br />

When he arrived in the United States, Giraudo first wanted to study<br />

with Stern’s bassist Jeff Andrews. Eventually through contact with other<br />

students at the Manhattan School of Music, Giraudo got more exposure to<br />

jazz’s rich tradition. “I was pretty clueless at first,” Giraudo recalls. “For<br />

instance, I’d never heard of the name ‘Monk.’ I knew some things, but at<br />

first I thought Duke Ellington was Dizzy Gillespie.”<br />

El Viaje’s concept is also partially about his journey to becoming a<br />

new father as well as growing as a composer.<br />

“I definitely hear my voice clearer on this CD,” Giraudo said. “And my<br />

tendency is to write longer and longer pieces.”<br />

—John Murph<br />

November 2009 DOWNBEAT 25

DRUM<br />

JEFF “TAIN” WATTS<br />

LEWIS NASH<br />

MATT WILSON<br />

FOLLOW<br />

THE<br />

LEADERS<br />

By Ken Micallef // Photos by Jimmy Katz<br />

The history of jazz drummers as leaders is illustrious if not<br />

particularly long-lived. Often relegated to “drummer<br />

only” or “non-musician” status by ignorant fellow musicians,<br />

jazz drummers have conquered the odds to create music<br />

easily on par with that of any instrumentalist. Such<br />

drummer/leaders as Max Roach, Elvin Jones, Art Blakey, Chick<br />

Webb, Gene Krupa, Buddy Rich, Kenny Clarke and Mel Lewis<br />

forged the paths that today’s stylistically well-versed, multiinstrumental,<br />

compositionally adept drummers follow to<br />

advance their own art.<br />

Surrounded by the vintage drum sets of such legends as<br />

Rich, Krupa, Jones, Sonny Greer and Louis Bellson (and many<br />

more) found at Steve Maxwell Vintage and Custom Drums in<br />

New York, three of today’s premier drummer/leader practitioners<br />

sat down this summer to discuss their art, their drumming<br />

and their place in the lineage of the great drummer/leaders who<br />

preceded them.<br />

“Someone has to act, someone has to write and someone has<br />

to direct,” Lewis Nash says. “We’re stepping behind the camera.”<br />

Matt Wilson and Jeff “Tain” Watts share his attitude. All<br />

have released albums as leaders, worked with a diverse cadre of<br />

musicians and toured and developed numerous recent projects.<br />

Nash is perhaps the most recorded jazz drummer of his generation,<br />

with sides as far ranging as Tommy Flanagan, Joe<br />

Lovano, Willie Nelson, Kenny Burrell, Betty Carter and Oscar<br />

Peterson. Most recently, Nash co-led The Blue Note Seven, and<br />

he is an ongoing musical director at Lincoln Center. His solo<br />

albums include Rhythm Is My Business and Stompin’ At The<br />

Savoy. His fourth CD as a leader includes his current quintet and<br />

is set for an early 2010 release; he can also be found on upcoming<br />

CDs from the Dizzy Gillespie Alumni All-Star Big Band<br />

and Dee Dee Bridgewater.<br />

Wilson’s latest quartet album, That’s Gonna Leave A Mark<br />

(his eighth as a leader), follows work as a leader with Arts and<br />

Crafts, Carl Sandburg Project, Futurists, Trio M and sideman<br />

work with Joe Lovano, Charlie Haden’s Liberation Music<br />

Orchestra, Marty Ehrlich/Ray Anderson Quartet, Elvis Costello,<br />

Jane Ira Bloom, Lee Konitz and Myra Melford.<br />

Watts, after long stints with the brothers Marsalis (he departed<br />

Branford’s group in mid-2009), recorded his first solo effort<br />

with 1991’s Megawatts, followed 10 years later by such well<br />

received albums as Citizen Tain, Bar Talk and, most recently,<br />

Watts, which documents his signature compositions and his<br />

November 2009 DOWNBEAT 27

mad sense of humor. Watts also appears on<br />

upcoming releases from Odean Pope (Odean’s<br />

List), John Beasley (Positootly), a live CD with<br />

Pat Martino and one from David Kikoski<br />

(Mostly Standards).<br />

Lists, credits and factoids say little about the<br />

raw talent, wisdom and skill each of these men<br />

brings to bear on the jazz world at large. Their<br />

grasp of history is sure, their views on bandleading<br />

challenging, and their camaraderie and joy in<br />

discussing their craft obvious. Most definitely,<br />

it’s time to give the drummer some.<br />

From left: Wilson, Watts and Nash play vintage kits that once belonged to jazz legends Joe Morello, Elvin Jones<br />

and Kenny Clarke, respectively, in the museum section of Steve Maxwell Vintage and Custom Drums.<br />

DownBeat: Why did each of you pursue<br />

becoming a leader and not remain a sideman<br />

only<br />

Lewis Nash: For me, it was seeing and talking<br />

to people like Max Roach, Elvin Jones, Art<br />

Blakey, even Billy Higgins—who, though he<br />

didn’t compose, led with what he was doing.<br />

Those people have influenced all of us to have a<br />

certain stature at the drums and be able to dictate<br />

certain things from the drums. All of us have<br />

ideas, things we jot down and file away, and<br />

because we’ve played with so many different<br />

people as sidemen, we get a lot of ideas from all<br />

these different directions.<br />

Matt Wilson: That’s why it makes for interesting<br />

bandleading, because we play with so many<br />

people. And the big picture presentation can be<br />

different because we are thinking about so many<br />

elements in the music, including groove.<br />

Jeff “Tain” Watts: I came up with these different<br />

groups mostly playing original music. I<br />

didn’t have a very long apprenticeship with<br />

older musicians to do a lot of interpretation with<br />

standard repertoire; I just started to accumulate a<br />

lot of original music. I started doing gigs and<br />

Branford signed me to Sony. Then I always<br />

found myself at a balance between being somebody<br />

in the band playing and trying to have a<br />

musical presentation. There are people who<br />

come out to see you play, so I have to remind<br />

myself to take a drum solo. You’ll look up in the<br />

middle of the gig and people will be looking at<br />

you for some drum excitement! [laughs]<br />

DB: What significant events contributed to your<br />

growth as leaders<br />

Nash: After a while there are certain things you<br />

want to express, and you’re not able to express<br />

them in any other situation, so you’ve got to create<br />

a situation. Sometimes I would be the leader<br />

in a situation where I wasn’t playing my<br />

arrangements or musical repertoire. Maybe I<br />

was the musical director, and since you have a<br />

leader’s mindset you know how to pull the elements<br />

together and make the performance come<br />

off. When leading, you’re thinking of a lot of<br />

different things ...<br />

Watts: ... the program ...<br />

Nash: ... pacing of the set ...<br />

Watts: ... things that don’t have anything to do<br />

with music!<br />

Nash: Sometimes you have to pull the band<br />

back with the drums: “OK, let’s go a different<br />

place!”<br />

DB: Does all of that somehow make you a better<br />

drummer<br />

Nash: Maybe all of that makes you a better<br />

overall musician moreso than making you a better<br />

drummer.<br />

Wilson: You think about some classic big band<br />

drummers—maybe it was a different vibe,<br />

maybe their presentation was more about that.<br />

Maybe someone like Louie Bellson or Chick<br />

Webb, they still really cared about the music.<br />

DB: What else contributes to your evolution as a<br />

leader<br />

Watts: You’re in all these situations playing for<br />

different bandleaders who are making decisions<br />

about repertoire and about presentation. You get<br />

all these little lessons: How to make sure that<br />

everyone is on the bus at the same time. Get a<br />

room list so you can call the bass player if he<br />

oversleeps. And it’s all in there whether you are<br />

actually going to be a bandleader part time or<br />

full time. I just began accumulating music, and I<br />

got a deal, and part of that is trying to sell the<br />

record that you made. I’m into documenting<br />

compositions and putting together a set of music<br />

and looking at the people and trying to shape a<br />

set to make them feel a certain way.<br />

DB: How do you gauge an audience like that<br />

Watts: Sometimes I just look at the types of<br />

people or age groups. If I’m playing my music,<br />

I’ll choose a piece that might strike a familiar<br />

chord with an older crowd, for instance. There’s<br />

a traditional jazz crowd that you can play a whole<br />

set of jazz to, but unless there’s something that’s<br />

right down the middle or a blues or something<br />

really swinging, they won’t be fulfilled.<br />

DB: So, Jeff, you wouldn’t bring out Zappaesque<br />

material like “The Devil’s Ring Tone: The<br />

Movie” from Watts for a roomful of geezers<br />

Nash: I like the way you put that. [laughs]<br />

“Hmmm, we have a bunch of geezers out there<br />

tonight!”<br />

Watts: There’s a lot of old hippies out there,<br />

too, some deadheads. You have to feel them out.<br />

I try to get the different food groups together in<br />

the first few tunes, maybe something exciting,<br />

something swinging, something with a groove<br />

and go from there.<br />

Wilson: I don’t change my sets, really. I just<br />

feel that if it is presented well, and you balance it<br />

out, if it’s honest it works. Dewey Redman<br />

would play all kinds of music in one night, and I<br />

want to do the same thing. You can play free,<br />

play a standard, play a Gershwin or an Ornette<br />

Coleman tune, you can mix it up.<br />

Nash: You don’t play down to an audience. But<br />

if you’re on a jazz cruise, for example, they<br />

don’t want to hear something adventurous, they<br />

are not the typical jazz fan who likes creative<br />

improvised music. The jazz party scene comes<br />

from a New Orleans style, and if you’re the least<br />

bit adventurous even playing bebop that audience<br />

might get a little annoyed. So in that<br />

instance it’s advisable to take into account who<br />

is in the audience.<br />

Wilson: You can play accessible music, but if<br />

it’s not personal to the audience, they’ll feel<br />

neglected. Then you are alienating them. It all<br />

depends on how you embrace those folks and<br />

feel that energy.<br />

DB: Lewis, how do you lead or control the band<br />

from the drum chair, as you mentioned<br />

Nash: You can’t really control music. You’re<br />

directing the band. You might initiate, and what<br />

happens after that is a group thing. You might<br />

want to nudge it one way.<br />

Wilson: Dewey used to say, “People sound<br />

their best playing with me.” If you can allow<br />

somebody to go some place and you’re not<br />

controlling it, that’s great. As a leader, if I try to<br />

put someone in an environment, I don’t have to<br />

say anything to them. They know how to play<br />

their instrument. You trust them. Dewey<br />