Comprehensive care of the patient with haemophilia and inhibitors ...

Comprehensive care of the patient with haemophilia and inhibitors ...

Comprehensive care of the patient with haemophilia and inhibitors ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Haemophilia (2013), 19, 2–10<br />

DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2012.02922.x<br />

REVIEW ARTICLE<br />

<strong>Comprehensive</strong> <strong>care</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>patient</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>haemophilia</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>inhibitors</strong> undergoing surgery: practical aspects<br />

R. KULKARNI<br />

Division <strong>of</strong> Pediatric <strong>and</strong> Adolescent Hematology/Oncology, Department <strong>of</strong> Pediatrics <strong>and</strong> Human Development, Michigan<br />

State University College <strong>of</strong> Human Medicine, East Lansing, MI, USA<br />

Summary. Congenital <strong>haemophilia</strong> is a rare <strong>and</strong><br />

complex condition for which dedicated specialized<br />

<strong>and</strong> comprehensive <strong>care</strong> has produced measurable<br />

improvements in clinical outcomes <strong>and</strong> advances in<br />

<strong>patient</strong> management. Among <strong>the</strong>se advances is <strong>the</strong><br />

ability to safely perform surgery in <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong><br />

inhibitor antibodies to factors VIII <strong>and</strong> IX, in whom<br />

all but <strong>the</strong> most necessary <strong>of</strong> surgeries were once<br />

avoided due to <strong>the</strong> risk for uncontrollable bleeding<br />

due to ineffectiveness <strong>of</strong> replacement <strong>the</strong>rapy.<br />

Never<strong>the</strong>less, surgery continues to pose a major<br />

challenge in this relatively rare group <strong>of</strong> <strong>patient</strong>s<br />

because <strong>of</strong> significantly higher costs than in <strong>patient</strong>s<br />

<strong>with</strong>out <strong>inhibitors</strong>, as well as a high risk for bleeding<br />

<strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r complications. Because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> concentration<br />

<strong>of</strong> expertise <strong>and</strong> experience, it is recommended<br />

that any surgery in <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>haemophilia</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong> be planned in conjunction <strong>with</strong> a<br />

<strong>haemophilia</strong> treatment centre (HTC) <strong>and</strong> performed in<br />

a hospital that incorporates a HTC. Coordinated,<br />

st<strong>and</strong>ard pre-, intra- <strong>and</strong> postoperative assessments<br />

<strong>and</strong> planning are intended to optimize surgical<br />

outcome <strong>and</strong> utilization <strong>of</strong> resources, including costly<br />

factor concentrates <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r haemostatic agents,<br />

while minimizing <strong>the</strong> risk for bleeding <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

adverse consequences both during <strong>and</strong> after surgery.<br />

This article will review <strong>the</strong> special considerations<br />

for <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong> as <strong>the</strong>y prepare for <strong>and</strong><br />

move through surgery <strong>and</strong> recovery, <strong>with</strong> an emphasis<br />

on <strong>the</strong> roles <strong>and</strong> responsibilities <strong>of</strong> individual members<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> multidisciplinary team in facilitating this<br />

process.<br />

Keywords: activated prothrombin complex concentrate,<br />

comprehensive health <strong>care</strong>, <strong>haemophilia</strong>, <strong>inhibitors</strong>,<br />

recombinant activated FVII, surgery<br />

Introduction<br />

Congenital <strong>haemophilia</strong>, a rare <strong>and</strong> complex condition,<br />

requires a lifetime <strong>of</strong> specialized <strong>care</strong>. A network<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>haemophilia</strong> treatment centres (HTCs) has been<br />

established in many developed countries to provide<br />

dedicated comprehensive, multidisciplinary <strong>care</strong> in a<br />

single setting [1]. In <strong>the</strong> United States, <strong>the</strong> provision <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>haemophilia</strong> <strong>care</strong> by <strong>the</strong>se centres has led to an array<br />

<strong>of</strong> documented improved outcomes, including substantial<br />

reductions in hospital visits, health <strong>care</strong> costs,<br />

work <strong>and</strong> school absenteeism <strong>and</strong> even mortality [2,3].<br />

Even in developing countries <strong>with</strong> limited haemostatic<br />

Correspondence: Roshni Kulkarni, MD, Department <strong>of</strong> Pediatrics<br />

<strong>and</strong> Human Development, Michigan State University Center<br />

for Bleeding <strong>and</strong> Clotting Disorders, Michigan State University,<br />

788 Service Road, B216 Clinical Center ‘B’ Wing, East Lansing,<br />

MI 48824, USA.<br />

Tel.: +517 355 5039; fax: +517 355 8312;<br />

e-mail: roshni.kulkarni@hc.msu.edu<br />

Accepted after revision 5 July 2012<br />

treatment options, <strong>the</strong> establishment <strong>of</strong> local expertise<br />

via such initiatives as ‘twinning’ programmes has<br />

resulted in improvements in <strong>patient</strong> <strong>care</strong> [1].<br />

Approximately 20–30% <strong>and</strong> 1–6% <strong>of</strong> <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong><br />

severe <strong>haemophilia</strong> A <strong>and</strong> B, respectively [4], develop<br />

inhibitory antibodies that render replacement <strong>the</strong>rapy<br />

ineffective, potentially leading to life-threatening bleeding<br />

events. Inhibitors are <strong>the</strong> most serious <strong>and</strong> costly<br />

complication <strong>of</strong> <strong>haemophilia</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>y particularly<br />

pose a challenge when surgical intervention is necessary.<br />

In <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> low-titre <strong>inhibitors</strong> (

SURGERY IN PATIENTS WITH HAEMOPHILIA AND INHIBITORS 3<br />

in this population, to <strong>the</strong> detriment <strong>of</strong> affected <strong>patient</strong>s<br />

[7,8]. Given <strong>the</strong> availability <strong>of</strong> effective bypassing<br />

agents, coupled <strong>with</strong> <strong>the</strong> increasing experience <strong>of</strong> HTCs<br />

in managing <strong>the</strong> surgical needs <strong>of</strong> <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> CHwI,<br />

even complex surgery is now feasible in this population<br />

[6,9–12]. However, <strong>the</strong> risk for uncontrollable bleeding<br />

remains a serious threat. Because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> specialized<br />

expertise required to ensure proper perioperative haemostasis,<br />

monitoring, <strong>and</strong> <strong>care</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong><br />

undergoing surgery, <strong>the</strong>se procedures should<br />

ideally be performed in hospitals affiliated <strong>with</strong> HTCs,<br />

where <strong>the</strong>re is a concentration <strong>of</strong> expert multidisciplinary<br />

resources [13].<br />

The objective <strong>of</strong> this article is to summarize key<br />

practical aspects <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> comprehensive <strong>care</strong> approach<br />

to surgery in CHwI, including important considerations<br />

before, during <strong>and</strong> after surgery.<br />

Methods<br />

A search <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> PubMed database-indexed literature<br />

was undertaken, using a combination <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> keywords<br />

‘hemophilia,’ ‘inhibitor’ <strong>and</strong> ‘surgery,’ to identify<br />

English-language articles describing general considerations<br />

for <strong>and</strong> anecdotal experience <strong>with</strong> surgery in<br />

<strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong> published between January<br />

1990 <strong>and</strong> July 2012. Original articles, review articles<br />

<strong>and</strong> case reports <strong>and</strong> series were consulted for general<br />

principles <strong>and</strong> recommendations for perioperative<br />

assessment <strong>and</strong> management <strong>of</strong> <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong>.<br />

Predominately larger case series consisting <strong>of</strong><br />

more than 10 cases <strong>and</strong> consensus protocols were referenced<br />

for perioperative haemostatic strategies; <strong>care</strong><br />

was made to avoid inclusion <strong>of</strong> case series <strong>with</strong> potentially<br />

overlapping data. Smaller case series <strong>and</strong> case<br />

reports were primarily reviewed to identify any considerations<br />

for specific surgery types or novel approaches<br />

to surgery in CHwI overall. Supplemental literature<br />

searches were conducted around specific aspects <strong>of</strong> surgery<br />

(e.g. anaes<strong>the</strong>tic management, physio<strong>the</strong>rapy) as<br />

needed. Information from <strong>the</strong> literature was complemented<br />

by <strong>the</strong> author’s clinical experience in this area.<br />

Practical aspects <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> surgical comprehensive<br />

<strong>care</strong> approach<br />

The comprehensive <strong>care</strong> approach ideally incorporates<br />

a number <strong>of</strong> specific pre-, intra-, <strong>and</strong> postoperative<br />

objectives for all <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> CHwI undergoing surgery,<br />

regardless <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> procedure to be performed<br />

(Table 1). There may also be specific perioperative<br />

considerations for individual surgical procedures<br />

(Table 2). The primary goal <strong>of</strong> this coordinated,<br />

multidisciplinary approach is to optimize operative<br />

results <strong>and</strong> recovery, while limiting adverse outcomes.<br />

The most common types <strong>of</strong> surgeries that have been<br />

performed in <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> CHwI include central<br />

venous access device (CVAD) placement/removal <strong>and</strong><br />

orthopaedic <strong>and</strong> dental procedures, although many<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r procedures have also been reported in this<br />

<strong>patient</strong> population [5,11].<br />

General preoperative assessments <strong>and</strong><br />

considerations<br />

Approximately 2–3 weeks prior to elective surgery, a<br />

member (or members) <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> st<strong>and</strong>ard multidisciplinary<br />

core HTC team – consisting <strong>of</strong> a haematologist,<br />

nurse coordinator, social worker <strong>and</strong> physical <strong>the</strong>rapist<br />

– will typically conduct an evaluation <strong>of</strong> whe<strong>the</strong>r<br />

or not <strong>the</strong> <strong>patient</strong> is an appropriate surgical c<strong>and</strong>idate,<br />

based on a thorough familiarity <strong>with</strong> <strong>the</strong> nature <strong>and</strong><br />

progression <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> condition for which surgery is<br />

advocated, <strong>and</strong> will prepare <strong>the</strong> <strong>patient</strong> for surgery,<br />

including arranging any necessary preoperative assessments<br />

<strong>and</strong> referrals. Specifically, <strong>the</strong> haematologist<br />

provides a written detailed treatment plan including<br />

duration <strong>and</strong> dosage <strong>of</strong> haemostatic <strong>the</strong>rapies, <strong>the</strong><br />

HTC nurse communicates <strong>with</strong> <strong>the</strong> operating room<br />

<strong>and</strong> hospital nurses to ensure that <strong>the</strong> plan is carried<br />

out appropriately, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> physical <strong>the</strong>rapist estimates<br />

when to initiate <strong>and</strong> how long to continue physical<br />

<strong>the</strong>rapy in cases <strong>of</strong> orthopaedic surgery. Prior to surgery,<br />

several aspects <strong>of</strong> surgical readiness should be<br />

explored, including <strong>the</strong> <strong>patient</strong>’s history <strong>of</strong> adherence<br />

to prior treatment recommendations, <strong>patient</strong> expectations<br />

regarding surgical outcome <strong>and</strong> recovery <strong>and</strong><br />

certain psychosocial elements, including current<br />

<strong>patient</strong> support systems. In cases in which <strong>the</strong>y have<br />

not been previously assessed, <strong>the</strong>se factors may be<br />

addressed during a formal preoperative visit, ideally<br />

several weeks before <strong>the</strong> scheduled surgery [14]. The<br />

preoperative visit also provides an opportunity to<br />

educate <strong>the</strong> <strong>patient</strong> <strong>and</strong> family about <strong>the</strong> surgical procedure<br />

itself <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> expected course <strong>of</strong> recovery.<br />

In addition to a general health appraisal, <strong>the</strong> preoperative<br />

medical assessment should include a history,<br />

including history <strong>of</strong> prior surgery as well as response<br />

to bypassing agents, <strong>and</strong> an evaluation for comorbid<br />

conditions, such as hepatitis C or HIV infection or<br />

cardiopulmonary, renal, or liver disease, for <strong>the</strong> purposes<br />

<strong>of</strong> appropriate anaes<strong>the</strong>tic management <strong>and</strong><br />

medication dosing. A comprehensive laboratory evaluation,<br />

including complete blood count; tests for liver<br />

<strong>and</strong> renal function; blood type; <strong>and</strong> haemostatic<br />

workup, including prothrombin time (PT), activated<br />

partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), fibrinogen,<br />

inhibitor assay, <strong>and</strong> for <strong>patient</strong>s who have a low-titre<br />

inhibitor or who are undergoing immune tolerance<br />

<strong>the</strong>rapy (ITT), a review <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir pharmacokinetics<br />

study, which may be used to guide <strong>the</strong> dosing frequency<br />

<strong>of</strong> factor concentrates. A thrombophilia<br />

workup (factor V Leiden, prothrombin mutation, proteins<br />

C <strong>and</strong> S, <strong>and</strong> antithrombin levels), although not<br />

© 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd Haemophilia (2013), 19, 2–10

4 R. KULKARNI<br />

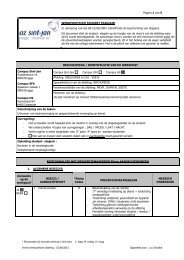

Table 1.<br />

Perioperative checklist for <strong>the</strong> <strong>patient</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>haemophilia</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong> undergoing surgery.<br />

Preoperative Intraoperative Postoperative<br />

Identify <strong>patient</strong> as a suitable surgical c<strong>and</strong>idate<br />

<strong>with</strong> regard to:<br />

Expectations for surgical outcome<br />

Readiness for anticipated recovery programme<br />

Perform relevant laboratory testing, including:<br />

Haemostatic workup (PT, aPTT, fibrinogen,<br />

inhibitor titre, CBC, thrombophilic markers,<br />

if indicated)<br />

Tests <strong>of</strong> hepatic <strong>and</strong> renal function, if indicated<br />

Evaluate current <strong>and</strong> prior analgesic usage <strong>and</strong><br />

any illicit drug use<br />

Request a dental evaluation (<strong>and</strong> treatment,<br />

if necessary)<br />

Refer to physical <strong>the</strong>rapist to devise a plan<br />

for ‘prehabilitation’ <strong>and</strong> assess postsurgical<br />

rehabilitative needs<br />

Refer <strong>patient</strong> for nutritional assessment<br />

Plan perioperative i.v. access<br />

Notify blood bank to hold potentially needed<br />

blood products; devise a plan for<br />

intra- <strong>and</strong> postoperative haemostasis<br />

Administer preplanned haemostatic regimen <strong>and</strong><br />

monitor response<br />

Apply surgical <strong>and</strong> anaes<strong>the</strong>tic<br />

practices <strong>and</strong> techniques that minimize <strong>the</strong> risk<br />

for bleeding both during <strong>and</strong> after surgery<br />

[including long term (e.g. avoid need for<br />

prolonged antithrombotic <strong>the</strong>rapy)]<br />

aPTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; CBC, complete blood count; i.v., intravenous; PT, prothrombin time.<br />

Analgesic regimen taking prior analgesic use<br />

into account<br />

Use mechanical techniques for<br />

thromboprophylaxis; consider pharmacological<br />

prophylaxis in <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> underlying<br />

thrombophilia only<br />

Observe <strong>patient</strong> for infection <strong>and</strong> maintain<br />

strict aseptic <strong>care</strong><br />

Monitor wound healing; continue haemostatic<br />

<strong>the</strong>rapy through beginning <strong>of</strong> healing<br />

Avoid premature mobilization <strong>and</strong> physical<br />

<strong>the</strong>rapy; pretreat <strong>with</strong> bypassing agent<br />

prior to <strong>the</strong>rapy sessions, once initiated<br />

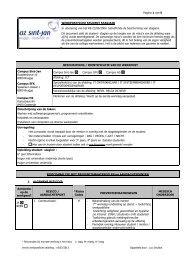

Table 2. Specific considerations for individual surgical procedures in <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>haemophilia</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong>.*<br />

Cardiac valve replacement<br />

Biopros<strong>the</strong>tic valve recommended in lieu <strong>of</strong> mechanical valve, which requires long-term anticoagulation [55]<br />

LMWH recommended for immediate postoperative thromboprophylaxis in <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>haemophilia</strong>, in conjunction <strong>with</strong> CFC [55] †<br />

Cardiac surgery requiring ECCS<br />

Consider FFP vs. saline prime <strong>of</strong> bypass circuit to avoid dilution <strong>of</strong> coagulation factors [12] ‡<br />

St<strong>and</strong>ard heparinization generally employed after CFC in <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>haemophilia</strong> <strong>with</strong>out <strong>inhibitors</strong> [56] §<br />

To maintain factor levels after surgery, consider reinfusing entire pump volume instead <strong>of</strong> just <strong>the</strong> RBC fraction (may require additional protamine to<br />

reverse heparin in perfusionate) [12]<br />

Hepatic procedures <strong>and</strong> surgeries<br />

Maintenance <strong>of</strong> a low CVP may be considered to minimize hepatic venous bleeding [57]<br />

Transjugular biopsy has been described in a <strong>patient</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>haemophilia</strong> A <strong>and</strong> high-titre inhibitor; may reduce <strong>the</strong> risk for bleeding compared <strong>with</strong><br />

percutaneous biopsy [58]<br />

In addition to haemostatic treatments targeting <strong>the</strong> inhibitor, FFP may be necessary in <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> pre-existing hepatic dysfunction to replace o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

deficient coagulation factors (FII, FVII, or FX) [59]<br />

Synovectomy<br />

Radiosynovectomy is first-line treatment, particularly in <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong> [60]<br />

Should proceed to arthroscopic synovectomy if radiosynovectomy is unsuccessful after three consecutive attempts [60]<br />

Osteotomy<br />

Internal fixation is preferred for stabilization <strong>of</strong> osteotomy site because external fixators may be associated <strong>with</strong> s<strong>of</strong>t tissue bleeding <strong>and</strong> infection along<br />

<strong>the</strong> pin tracks [8]<br />

Bony pseudotumour excision<br />

Surgical excision is treatment <strong>of</strong> choice for proximal pseudotumors, but may be associated <strong>with</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>use bleeding <strong>and</strong> infection [60]<br />

Consider embolization or radio<strong>the</strong>rapy in lieu <strong>of</strong> surgical removal in <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong> [60]<br />

CFC, clotting factor correction; CVP, central venous pressure; ECCS, extracorporeal circulatory support; FFP, fresh frozen plasma; FII, factor II; FVII,<br />

factor VII; FX, factor X; LMWH, low-molecular weight heparin; RBC, red blood cell.<br />

*In most cases, in <strong>the</strong> absence <strong>of</strong> evidence specifically in <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> CHwI, individual considerations are based on <strong>the</strong>oretical principles aimed at minimizing<br />

bleeding risk in any <strong>patient</strong> or in <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> an increased risk for bleeding. Recommendations or considerations that apply specifically to<br />

<strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong>out <strong>inhibitors</strong> (but may be extrapolated to <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong>) are denoted.<br />

† Recommendations are specifically for <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>haemophilia</strong> <strong>with</strong>out <strong>inhibitors</strong>; no corresponding recommendations exist for <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong><br />

at present.<br />

‡ Applies primarily to <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong> receiving factor replacement for haemostatic coverage.<br />

§ Cases in <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong> are limited <strong>and</strong> describe primarily <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> low-titre <strong>inhibitors</strong>. In all cases, high-dose factor replacement was used<br />

intraoperatively; heparinization protocols were not described.<br />

routinely performed, can be undertaken in those <strong>with</strong><br />

a prior history or family history <strong>of</strong> thrombosis.<br />

In conjunction <strong>with</strong> <strong>the</strong> pain management team, a<br />

preoperative assessment <strong>of</strong> pain <strong>and</strong> current <strong>and</strong> prior<br />

use <strong>of</strong> prescribed opioids, illicit drugs or recreational<br />

substances should be performed. Dental evaluation<br />

<strong>and</strong> treatment may be warranted, particularly if<br />

implantation <strong>of</strong> a pros<strong>the</strong>tic device or CVAD is<br />

expected. A physical <strong>the</strong>rapy evaluation may also be<br />

warranted for <strong>patient</strong>s undergoing elective orthopaedic<br />

surgery (EOS). During <strong>the</strong> initial preoperative visit,<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>rapist will typically evaluate <strong>the</strong> <strong>patient</strong>’s<br />

baseline musculoskeletal <strong>and</strong> functional status <strong>and</strong><br />

bleeding patterns in preparation for planning a post-<br />

Haemophilia (2013), 19, 2–10<br />

© 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

SURGERY IN PATIENTS WITH HAEMOPHILIA AND INHIBITORS 5<br />

operative rehabilitative regimen <strong>and</strong> initiate a plan for<br />

preoperative <strong>the</strong>rapy, or ‘prehabilitation,’ as needed<br />

[8]. In addition, <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>rapist can determine <strong>the</strong> necessity<br />

for mobility aids or adaptations to <strong>the</strong> home environment<br />

that may facilitate mobility <strong>and</strong> prevent<br />

injury after discharge.<br />

Additional preoperative considerations may include<br />

devising a plan for perioperative intravenous access.<br />

For long-term postoperative access, placement <strong>of</strong> a<br />

CVAD or a peripherally inserted central ca<strong>the</strong>ter<br />

(PICC) may be considered in lieu <strong>of</strong> peripheral access<br />

[14]. However, given that <strong>the</strong> presence <strong>of</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong> is<br />

an independent risk factor for infection after total<br />

knee replacement (TKR) [15], <strong>the</strong> potential benefits <strong>of</strong><br />

CVAD placement must be weighed against <strong>the</strong> risk for<br />

infection in <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong>. Patients should<br />

be advised to discontinue any non-steroidal antiinflammatory<br />

drugs or antiplatelet agents a week prior<br />

to surgery [13]. Referral should be made to a dietician<br />

to evaluate nutritional status, since obesity or<br />

malnourishment as determined by body mass index is<br />

an important predictor <strong>of</strong> postoperative complications<br />

[16,17]. Finally, as part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> holistic approach to<br />

preparing a <strong>patient</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong> for surgery, <strong>the</strong><br />

HTC social worker should conduct a full psychosocial<br />

assessment, including identification <strong>of</strong> potential<br />

barriers to <strong>and</strong> requirements for optimal recovery.<br />

The consulting surgeon should have experience<br />

operating on <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> CHwI in addition to performing<br />

<strong>the</strong> specific indicated surgery. Solimeno et al.<br />

[15] reported that <strong>the</strong> experience <strong>and</strong> expertise <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

operating surgeon was an independent predictor <strong>of</strong><br />

infection risk following TKR in <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>haemophilia</strong>,<br />

<strong>with</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>with</strong>out <strong>inhibitors</strong>. The preoperative<br />

surgical evaluation provides <strong>the</strong> surgeon <strong>with</strong> an<br />

opportunity to examine <strong>the</strong> <strong>patient</strong> <strong>and</strong> review or<br />

obtain relevant studies, <strong>and</strong> discuss <strong>the</strong> surgical procedure<br />

<strong>and</strong> expected outcome <strong>and</strong> recovery <strong>with</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>patient</strong> as part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> informed consent process. The<br />

surgeon should be made aware <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>patient</strong>’s HIV<br />

<strong>and</strong> hepatitis C status, as affected <strong>patient</strong>s are more<br />

susceptible to postoperative infections. In addition, to<br />

reduce <strong>the</strong> risk for transmission <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se blood-borne<br />

pathogens to <strong>the</strong> surgical team, personal protective<br />

equipment <strong>and</strong> appropriate disposal <strong>of</strong> contaminated<br />

materials is warranted [8]. If use <strong>of</strong> ethanol lock to<br />

prevent CVAD infections [18] is intended, <strong>the</strong> surgeon,<br />

in consultation <strong>with</strong> <strong>the</strong> HTC staff, should<br />

determine ca<strong>the</strong>ter compatibility <strong>with</strong> ethanol [19].<br />

To ensure access to relevant laboratory studies <strong>and</strong><br />

specialists, elective procedures should be scheduled for<br />

early in <strong>the</strong> week <strong>and</strong> as early in <strong>the</strong> day as possible<br />

[13,20]. For maximal effectiveness, <strong>the</strong> time between<br />

administration <strong>of</strong> haemostatic treatments <strong>and</strong> surgery<br />

should be minimized. This is possible if <strong>the</strong> haematology<br />

team is informed <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> precise time (<strong>with</strong>in 1–2 h)at<br />

which surgery will occur [20]. A haematologist should<br />

also be readily available for consultation during at least<br />

<strong>the</strong> first few days after surgery [13]. Often, in cases <strong>of</strong><br />

orthopaedic procedures, <strong>the</strong> surgeon may consider performing<br />

multiple surgeries during a single operative<br />

session; <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> CHwI frequently require multiple<br />

such surgeries [8,14]. However, <strong>patient</strong>s must be<br />

informed in advance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> compounded duration <strong>and</strong><br />

rigour <strong>of</strong> recovery following multiple procedures under<br />

a single anaes<strong>the</strong>tic administration [13].<br />

The coordination <strong>of</strong> urgent or emergent procedures<br />

in <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> CHwI poses a particular challenge,<br />

given <strong>the</strong> need for rapid mobilization <strong>of</strong> resources <strong>and</strong><br />

multidisciplinary collaboration in such cases. Sufficient<br />

supplies <strong>of</strong> haemostatic agents must be readily accessible,<br />

along <strong>with</strong> laboratory, blood bank <strong>and</strong> pharmacy<br />

support. When possible (e.g. for pending organ transplantation),<br />

advance planning should be undertaken<br />

to ensure prompt availability <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se resources at <strong>the</strong><br />

time <strong>of</strong> surgery [12].<br />

For elective procedures, <strong>the</strong> initial plan for perioperative<br />

haemostasis is devised by <strong>the</strong> haematologist<br />

before surgery, based on such factors as <strong>the</strong> <strong>patient</strong>’s<br />

inhibitor titre <strong>and</strong> prior responses to specific haemostatic<br />

agents, as well as <strong>the</strong> expected magnitude <strong>and</strong><br />

risk for bleeding based on whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> surgery is major<br />

or minor [10]. Preoperative planning should incorporate<br />

a determination <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> specific haemostatic <strong>the</strong>rapies<br />

to be used during <strong>and</strong> after surgery, including<br />

dosing regimens <strong>and</strong> whe<strong>the</strong>r continuous or bolus<br />

treatment will be used. It is <strong>of</strong>ten helpful for a member<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> HTC team to be present in <strong>the</strong> operating room<br />

(OR) to assist in communication between <strong>the</strong> OR staff<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>patient</strong>/family <strong>and</strong> to provide on-site guidance<br />

regarding haemostatic management, if needed.<br />

The use <strong>of</strong> high-dose FVIII or FIX concentrates to<br />

overcome <strong>inhibitors</strong> in CHwI undergoing surgery,<br />

although ideal <strong>and</strong> measurable [8,21], is <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

restricted to those <strong>with</strong> low-titre or low-responding<br />

<strong>inhibitors</strong> or those who have successfully achieved<br />

tolerance. Both bolus <strong>and</strong> continuous administration<br />

<strong>of</strong> replacement factor have been effectively used in this<br />

setting, although in <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>haemophilia</strong> B <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>inhibitors</strong>, <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> high doses <strong>of</strong> FIX may increase<br />

<strong>the</strong> risk for anaphylaxis [10]. In <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>haemophilia</strong><br />

A receiving FVIII replacement for surgery, an<br />

anamnestic increase in inhibitor titre may occur,<br />

necessitating a switch to bypassing <strong>the</strong>rapy [22].<br />

Although preoperative attempts to reduce <strong>the</strong> inhibitor<br />

titre using rituximab [9] <strong>and</strong> ITT [6] have been<br />

described, <strong>the</strong>se treatments have limitations, most<br />

notably <strong>the</strong> time required for such regimens to take<br />

effect <strong>and</strong>, <strong>with</strong> immunosuppressive eliminative<br />

agents, <strong>the</strong> potential for susceptibility to infections.<br />

Bypassing agents are <strong>the</strong> haemostatic products <strong>of</strong><br />

choice for <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> high-titre or high-responding<br />

<strong>inhibitors</strong> or those <strong>with</strong> <strong>haemophilia</strong> B <strong>and</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong>.<br />

Each <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> commercially available bypassing agents –<br />

© 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd Haemophilia (2013), 19, 2–10

6 R. KULKARNI<br />

recombinant activated FVII (rFVIIa; NovoSeven ® RT;<br />

Novo Nordisk A/S, Bagsvaerd, Denmark) <strong>and</strong> activated<br />

prothrombin complex concentrate (aPCC;<br />

FEIBA ® , Factor Eight Inhibitor Bypassing Agent);<br />

Baxter Health<strong>care</strong> Corporation (Westlake Village, CA,<br />

USA) – have been successfully used for haemostatic<br />

coverage for surgery in both children <strong>and</strong> adults <strong>with</strong><br />

CHwI, <strong>with</strong> comparable efficacy <strong>and</strong> safety. However,<br />

<strong>the</strong>re are no evidence-based guidelines for <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong><br />

ei<strong>the</strong>r agent in this setting. Recombinant FVIIa has a<br />

relatively short half-life <strong>of</strong> 2.7 h in adults <strong>and</strong> 1.3 h in<br />

children [23]. Optimal dosing remains uncertain.<br />

The choice <strong>of</strong> product for those <strong>with</strong> high-titre<br />

<strong>inhibitors</strong> is dependent on <strong>the</strong> age <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>patient</strong>, prior<br />

exposure to plasma products, type <strong>of</strong> bleeding episode,<br />

volume-<strong>of</strong>-reconstitution cost, efficacy <strong>and</strong> safety. At<br />

most institutions, for <strong>patient</strong>s who are plasma-naïve<br />

or for those <strong>with</strong> <strong>haemophilia</strong> B <strong>and</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong>, rFVIIa<br />

is used to achieve rapid haemostasis (recombinant porcine<br />

FVIII may likewise be used for <strong>the</strong> same purpose<br />

in <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>haemophilia</strong> A <strong>and</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong> who are<br />

plasma-naïve, when it becomes available). However,<br />

for <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>haemophilia</strong> A who have been previously<br />

exposed to plasma products, ei<strong>the</strong>r aPCC or<br />

rFVIIa may be used [24]. The accompanying algorithm<br />

provides some guidance regarding haemostatic<br />

<strong>the</strong>rapy (Fig. 1), although <strong>the</strong>rapy is <strong>of</strong>ten highly<br />

individualized. In particular, <strong>the</strong> limited availability <strong>of</strong><br />

bypassing agents or even factor concentrates in certain<br />

parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world may necessitate an individualized<br />

approach to management <strong>and</strong> adaptations in haemostatic<br />

regimens, such as <strong>the</strong> intra- <strong>and</strong> postoperative<br />

use <strong>of</strong> low-dose aPCC, cryoprecipitate, or adjunctive<br />

<strong>the</strong>rapies like antifibrinolytics <strong>and</strong> fibrin glue [25,26].<br />

The use <strong>of</strong> rFVIIa for haemostatic coverage in major<br />

<strong>and</strong> minor emergency <strong>and</strong> (mostly) elective surgeries<br />

in paediatric <strong>and</strong> adult <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> CHwI has been<br />

described in several retrospective series [6,27–31], a<br />

recent literature review [32], <strong>and</strong> a more recent analysis<br />

by Valentino et al. <strong>of</strong> data from two prospective<br />

studies, <strong>the</strong> Hemophilia <strong>and</strong> Thrombosis Research<br />

Society registry <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> literature [5]. Dosing varied<br />

substantially across <strong>the</strong>se sources. In most cases, initial<br />

rFVIIa doses <strong>of</strong> 90–120 µg kg 1 were used, <strong>with</strong> a<br />

tendency towards higher initial doses for major surgeries<br />

[27–29]. Subsequent intra- <strong>and</strong> postoperative<br />

rFVIIa dosing varied <strong>and</strong> incorporated both bolus <strong>and</strong><br />

continuous administration <strong>of</strong> rFVIIa. In some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

centres represented in retrospective case series, st<strong>and</strong>ardized<br />

regimens were described [6,27]. Overall,<br />

rFVIIa was reported as effective in <strong>the</strong> vast majority<br />

<strong>of</strong> cases encompassed by <strong>the</strong> aforementioned sources.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> analysis by Valentino et al. [5], which incorporated<br />

a small number <strong>of</strong> medical procedures (n = 45)<br />

in addition to surgical <strong>and</strong> dental procedures, rFVIIa<br />

was deemed effective in 333 (84%) <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 395 cases<br />

represented. Thromboembolic complications attributable<br />

to rFVIIa were reported in 0.025% <strong>of</strong> procedures<br />

included in that analysis.<br />

Consensus recommendations for rFVIIa dosing for<br />

minor <strong>and</strong> intermediate or major surgical procedures<br />

in both adult <strong>and</strong> paediatric <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> CHwI have<br />

been published (Table 3) [33]. Subsequently, a consensus<br />

protocol [13] for rFVIIa dosing was devised specifically<br />

for EOS based on published data <strong>and</strong> expert<br />

opinion, incorporating recommendations for concomitant<br />

tranexamic acid dosing (Table 4), provided <strong>the</strong>re<br />

are no contraindications. Satisfactory intraoperative<br />

haemostasis was achieved utilizing <strong>the</strong> higher initial<br />

rFVIIa dosing endorsed by this protocol in 13 procedures<br />

performed in five comprehensive <strong>haemophilia</strong><br />

<strong>care</strong> centres in <strong>the</strong> United Kingdom <strong>and</strong> Irel<strong>and</strong> [13].<br />

More recently, Caviglia et al. [34] recommended <strong>the</strong><br />

following for optimal perioperative dosing <strong>of</strong> rFVIIa<br />

<strong>and</strong> aPCC: for rFVIIa, 120–180 µg kg 1 preoperatively<br />

followed by 90 µg kg 1 every 2 h postoperatively,<br />

<strong>and</strong> for aPCC, 100 U kg 1 preoperatively<br />

followed by 75–100 U kg 1 postoperatively, to a<br />

maximum <strong>of</strong> 200 U kg 1 .<br />

First-line use <strong>of</strong> aPCC for major <strong>and</strong> minor emergency<br />

<strong>and</strong> (again mostly) elective surgeries in paediatric<br />

<strong>and</strong> adult <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> CHwI has been described<br />

in several retrospective series comprising 11 or more<br />

surgeries [6,22,27,35–39]. In general, initial doses <strong>of</strong><br />

50–100 U kg 1 were given prior to surgery, ei<strong>the</strong>r as<br />

a single dose or as multiple doses in <strong>the</strong> days or hours<br />

preceding surgery. Subsequent aPCC doses totalling<br />

up to 200 U kg 1 day 1 were administered beginning<br />

6–8 h after surgery at 6- to 12-h intervals for variable<br />

durations <strong>of</strong> time. Consensus recommendations for<br />

aPCC dosing for both major <strong>and</strong> minor surgeries have<br />

been developed (Table 3) [33]. Criteria for satisfactory<br />

haemostasis were met in 80% or more <strong>of</strong> cases in<br />

each <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> aforementioned series. There was a single<br />

thromboembolic event reported across more than 170<br />

surgeries in <strong>the</strong> combined series.<br />

The sequential or combined use <strong>of</strong> rFVIIa <strong>and</strong> aPCC<br />

for haemostatic coverage during surgery <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> early<br />

postoperative period has also been described in<br />

<strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> CHwI [35,40]; in some cases, this strategy<br />

was adopted due to prior clinical response to one<br />

or both bypassing agents or bleeding complications<br />

relative to <strong>the</strong> current surgery [35,40], while in o<strong>the</strong>rs,<br />

<strong>patient</strong>s were switched to aPCC after initial coverage<br />

<strong>with</strong> rFVIIa because <strong>of</strong> cost [35]. With combined <strong>the</strong>rapies,<br />

one should be cautious about <strong>the</strong> occurrence <strong>of</strong><br />

thromboembolic events [40], although none have been<br />

reported in <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> CHwI undergoing surgery.<br />

Although not available at all institutions, preoperative<br />

evaluation <strong>of</strong> haemostatic response to bypassing<br />

agents using thrombin generation testing (TGT) or<br />

thromboelastography (TEG) has been proposed as a<br />

means to optimize <strong>the</strong> haemostatic management <strong>of</strong><br />

individual <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong> for surgery [13,41].<br />

Haemophilia (2013), 19, 2–10<br />

© 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

SURGERY IN PATIENTS WITH HAEMOPHILIA AND INHIBITORS 7<br />

Haemophilia <strong>with</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong> undergoing surgery<br />

Fig. 1. Proposed algorithm for <strong>the</strong> selection <strong>of</strong> a<br />

haemostatic agent for <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> CHwI<br />

undergoing surgery, as utilized at <strong>the</strong> author’s<br />

institution <strong>and</strong> derived from <strong>the</strong> literature<br />

[4,35,54]. The selection <strong>of</strong> agent is dependent on<br />

<strong>the</strong> type <strong>of</strong> <strong>haemophilia</strong> (A vs. B), <strong>and</strong> in <strong>patient</strong>s<br />

<strong>with</strong> <strong>haemophilia</strong> A, whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> <strong>patient</strong> is<br />

plasma-naïve or -experienced. aPCC, activated<br />

prothrombin complex concentrate; CHwI,<br />

congenital <strong>haemophilia</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong>; CI,<br />

continuous infusion; FVIII, factor VIII; rFVIIa,<br />

recombinant-activated factor VII.<br />

Low titre/<br />

low responder<br />

Haemophilia A<br />

High titre<br />

Haemophilia B<br />

FVIII 100 U kg –1<br />

loading dose<br />

followed by 50–<br />

100 U kg –1 q8–12 h<br />

OR CI 10 U kg –1 h –1 Plasma-naïve<br />

rFVIIa bolus 90–120 µg kg –1 q2 h<br />

for 48 h (single 270 µg kg –1 dose<br />

Plasma-experienced<br />

has been used), <strong>the</strong>n increase<br />

interval; CI may also be used<br />

(see Table 3)<br />

If no response: may increase<br />

rFVIIa dose or switch to aPCC<br />

May alternate rFVIIa <strong>and</strong> aPCC<br />

Minor surgery: treat for 3 days<br />

rFVIIa (see<br />

dosages under<br />

<strong>haemophilia</strong> A)<br />

Major surgery: aPCC 200 U kg –1<br />

(max). Doses <strong>of</strong> 50–100 U kg –1<br />

q8–24 h for 2–4 days <strong>the</strong>n taper<br />

over complete treatment course<br />

If no response, switch to rFVIIa<br />

May alternate rFVIIa <strong>and</strong> aPCC<br />

Minor surgery: aPCC 100–150<br />

U kg –1 for 3 days<br />

Table 3. Consensus recommendations for rFVIIa <strong>and</strong> aPCC dosing for surgery in <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>haemophilia</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong> [33].<br />

Postoperative dosing<br />

Preoperative dosing<br />

Days 1–5 Days 6–14<br />

rFVIIa<br />

Minor surgery 90–120 µg kg 1 q2 h* 90–120 µg kg 1 q2 h up to four times <strong>the</strong>n q3–6 h for 24 h<br />

Intermediate/major surgery 120 µg kg 1 q2 h † 90–120 µg kg 1 q2 h Day 1, <strong>the</strong>n q3 h Day 2, <strong>the</strong>n q4 h Days 3–5 90–120 µg kg 1 q6 h<br />

Continuous infusion 15–50 µg kg 1 h 1 15–50 µg kg 1 h 1 15–50 µg kg 1 h 1<br />

aPCC<br />

Minor surgery 50–75 U kg 1 50–75 U kg 1 q12–24 h one to two times<br />

Intermediate/major surgery 75–100 U kg 1 75–100 U kg 1 q8–12 h 75–100 U kg 1 q12 h<br />

aPCC, activated prothrombin complex concentrate; rFVIIa, recombinant-activated factor VII.<br />

*Recommended initial preoperative paediatric dose is 120–150 µg kg 1 q2 h.<br />

† Recommended initial preoperative paediatric dose is 150 µg kg 1 q2 h.<br />

Table 4. Consensus protocol for rFVIIa dosing in EOS in <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>haemophilia</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong> [13].<br />

rFVIIa dosing<br />

Adjunctive haemostatic <strong>the</strong>rapies<br />

Preoperative 120–180 µg kg 1 TXA: 25 µg kg 1 PO q6–8 h evening before surgery<br />

Intraoperative<br />

Postoperative*<br />

90 µg kg 1 q2 h; final intraoperative bolus before final<br />

reduction in hip arthroplasty <strong>and</strong> before release <strong>of</strong><br />

tourniquet (if used) in knee arthroplasty<br />

90 µg kg 1 q2 h for first 48 h, <strong>the</strong>n<br />

q3 h 9 48 h, <strong>the</strong>n<br />

q4 h 9 72 h, <strong>the</strong>n<br />

q6 h through discharge †<br />

Consider topical application <strong>of</strong> a fibrin sealant or vasoconstrictor<br />

(e.g. epinephrine) to minimize capillary oozing<br />

Continue TXA 25 µg kg 1 PO q6–8 h until discharge<br />

90 µg kg 1 bolus 10 min prior to removal <strong>of</strong> drains or sutures<br />

EOS, elective orthopaedic surgery; PO, per os (by mouth); rFVIIa, recombinant activated factor VII; TXA, tranexamic acid.<br />

*Downward titration <strong>of</strong> rFVIIa dosing should only occur if <strong>the</strong>re is good haemostasis.<br />

† Discharge should occur in ∼ 10–12 days after surgery in uncomplicated cases.<br />

In a small prospective study <strong>of</strong> 10 surgeries in <strong>patient</strong>s<br />

<strong>with</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong>, in vitro <strong>and</strong> ex vivo TGT were used<br />

to assess <strong>the</strong> dose-dependent haemostatic response to<br />

each bypassing agent preoperatively; TGT was <strong>the</strong>n<br />

used intra- <strong>and</strong> postoperatively to monitor <strong>the</strong><br />

response to haemostatic <strong>the</strong>rapy, which was selected<br />

based on <strong>the</strong> preoperative TGT results [41]. Thrombin<br />

generation correlated <strong>with</strong> clinical haemostasis in this<br />

study, <strong>and</strong> preoperative TGT results were generally<br />

predictive <strong>of</strong> perioperative haemostatic response.<br />

Thromboelastography was similarly used to guide<br />

rFVIIa <strong>the</strong>rapy in a <strong>patient</strong> <strong>with</strong> CHwI undergoing<br />

urgent evacuation <strong>of</strong> a spinal cord haematoma [42].<br />

Although <strong>the</strong>se preliminary findings suggest <strong>the</strong> potential<br />

utility <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se techniques for optimizing haemostatic<br />

<strong>the</strong>rapy in individual <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> CHwI<br />

© 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd Haemophilia (2013), 19, 2–10

8 R. KULKARNI<br />

undergoing surgery, fur<strong>the</strong>r study <strong>and</strong> validation are<br />

needed before <strong>the</strong>y can be more widely adopted for<br />

this purpose [13,41].<br />

Intraoperative considerations<br />

Preoperative planning <strong>of</strong> haemostatic coverage for<br />

surgery should incorporate a strategy for monitoring<br />

haemostatic response during surgery. However, this<br />

poses a challenge in CHwI as <strong>the</strong> major drawbacks <strong>of</strong><br />

rFVIIa <strong>and</strong> aPCC are <strong>the</strong>ir unpredictable haemostatic<br />

effect, lack <strong>of</strong> laboratory assays to monitor efficacy<br />

<strong>and</strong> dosing frequency, as well as <strong>the</strong> potential risk <strong>of</strong><br />

thrombosis. The utility <strong>of</strong> plasma-based coagulation<br />

assays such as PT <strong>and</strong> aPTT is limited, as <strong>the</strong>se assays<br />

do not assess clot stability, <strong>the</strong> effect <strong>of</strong> platelets in<br />

haemostasis, or thrombin generation on <strong>the</strong> surface <strong>of</strong><br />

platelets, which is thought to be a key component <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> haemostatic mechanism <strong>of</strong> rFVIIa [43]. As<br />

previously mentioned, <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> TGT <strong>and</strong> TEG in this<br />

setting is still investigational.<br />

The team must be prepared to manage any excessive<br />

breakthrough bleeding that may occur during surgery.<br />

In addition to adjustments in <strong>the</strong> primary haemostatic<br />

<strong>the</strong>rapy in use, adjunctive haemostatic agents may be<br />

used. Despite concerns about potential thrombogenic<br />

risks <strong>and</strong> a lack <strong>of</strong> consensus related to <strong>the</strong> concomitant<br />

use <strong>of</strong> antifibrinolytic agents <strong>with</strong> bypassing<br />

agents to augment surgical haemostasis, this practice<br />

has been extensively employed in <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> CHwI<br />

[9,13,27,28,31,35,44]. To optimize haemostasis <strong>and</strong><br />

prevent postoperative bleeding, <strong>the</strong> surgeon should<br />

attempt to minimize s<strong>of</strong>t tissue dissection <strong>and</strong> should<br />

pay meticulous attention to primary haemostasis at<br />

<strong>the</strong> conclusion <strong>of</strong> surgery [30]. When feasible <strong>and</strong><br />

especially for abdominal surgeries [45], a less invasive<br />

(e.g. laparoscopic) overall approach is preferable to<br />

open surgery; however, <strong>the</strong> potential risks <strong>of</strong> a less<br />

invasive approach, including limited access to <strong>the</strong> surgical<br />

field in <strong>the</strong> event <strong>of</strong> accidental vascular injury,<br />

must be weighed against potential benefits such as<br />

reduced postoperative pain <strong>and</strong> hastened recovery<br />

<strong>with</strong> a smaller incision [45]. Topical haemostatic<br />

agents, such as fibrin glue or topical thrombin, may<br />

be used as needed to augment systemic haemostatic<br />

treatments [13,27,28,30,36]. The potential for<br />

impaired wound healing in <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>haemophilia</strong><br />

should also be considered in <strong>the</strong> technical approach to<br />

surgery [17]. Additional procedure-specific considerations<br />

<strong>of</strong> which <strong>the</strong> surgeon <strong>and</strong> OR team should have<br />

prior knowledge are outlined in Table 2.<br />

General postoperative <strong>care</strong><br />

Pain management is a primary concern in <strong>the</strong> immediate<br />

postoperative period. Knowledge <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>patient</strong>’s<br />

prior analgesic regimen may be critical for anticipating<br />

postoperative analgesic requirements, since <strong>patient</strong>s<br />

receiving opioids before surgery may require higherthan-usual<br />

initial doses. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory<br />

drugs should be avoided because <strong>the</strong>y may induce<br />

platelet dysfunction <strong>and</strong> cause gastrointestinal bleeding<br />

[46]. Although highly effective <strong>and</strong> shown to be<br />

safe in <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>haemophilia</strong> <strong>with</strong>out <strong>inhibitors</strong><br />

after sufficient factor replacement [47,48], regional<br />

<strong>and</strong> neuraxial anaes<strong>the</strong>tic <strong>and</strong> analgesic techniques are<br />

contraindicated because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> risk for bleeding <strong>and</strong> a<br />

lack <strong>of</strong> evidence supporting <strong>the</strong>ir safety in <strong>the</strong>se<br />

<strong>patient</strong>s [8]. Given <strong>the</strong> limited options for delivering<br />

analgesia in <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> CHwI, consultation <strong>with</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> anaes<strong>the</strong>siology or pain service may be especially<br />

helpful in this <strong>patient</strong> population.<br />

Although bleeding is <strong>the</strong> primary complication <strong>of</strong><br />

surgery in CHwI, thrombosis is also a concern, given<br />

postoperative immobility <strong>and</strong> exposure to potentially<br />

thrombogenic haemostatic treatments. This risk may<br />

be particularly increased in older <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>and</strong> in <strong>the</strong><br />

setting <strong>of</strong> overcorrected FVIII levels [49,50]. Whereas<br />

postoperative anticoagulation (e.g. low-molecularweight<br />

heparin) has been advocated in specific groups<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>haemophilia</strong> <strong>with</strong>out <strong>inhibitors</strong>,<br />

namely older <strong>patient</strong>s who have undergone major<br />

orthopaedic surgery [49] <strong>and</strong> <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> normal or<br />

near-normal trough factor levels following factor<br />

replacement [50], this practice is not generally recommended<br />

in <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong> [49,50]. Instead,<br />

non-pharmacological measures, such as intermittent<br />

pneumatic or graded compression methods, may be<br />

used [49]; however, pharmacological thromboprophylaxis<br />

may be considered in <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> underlying<br />

thrombophilia [46].<br />

Infection may be especially catastrophic after joint<br />

replacement, potentially prompting pros<strong>the</strong>tic<br />

removal. Patients <strong>with</strong> <strong>haemophilia</strong> are at increased<br />

risk for delayed infection in particular [14]. The most<br />

likely source <strong>of</strong> delayed infection in this population is<br />

bacteraemia from a CVAD or during a dental<br />

procedure. Therefore, <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> CVADs or joint<br />

hardware should receive antimicrobial prophylaxis<br />

before any dental procedure. In addition, <strong>patient</strong>s or<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir <strong>care</strong>rs should be educated regarding <strong>the</strong> importance<br />

<strong>of</strong> using strict aseptic technique when caring for<br />

<strong>and</strong> accessing CVADs or PICCs or when attempting<br />

self-infusion.<br />

Bleeding is perhaps <strong>the</strong> most serious concern after<br />

surgery in CHwI. Bleeding into <strong>the</strong> operative site after<br />

arthroplasty may lead to infection <strong>and</strong> loss <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

pros<strong>the</strong>sis [51]. Therefore, in contrast to <strong>the</strong> traditional<br />

postsurgical approach, early mobilization <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong> after arthroplasty is <strong>of</strong>ten discouraged<br />

because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> possibility <strong>of</strong> bleeding, even<br />

at <strong>the</strong> risk <strong>of</strong> compromising ultimate range <strong>of</strong> motion<br />

[51]. Once physical <strong>the</strong>rapy is instituted, pretreatment<br />

<strong>with</strong> a bypassing agent is recommended before each<br />

Haemophilia (2013), 19, 2–10<br />

© 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

SURGERY IN PATIENTS WITH HAEMOPHILIA AND INHIBITORS 9<br />

<strong>the</strong>rapy session for 2–4 weeks after surgery [52,53].<br />

For most major surgeries reported in <strong>the</strong> literature,<br />

haemostatic <strong>the</strong>rapy was continued for ca 10–14 days,<br />

<strong>with</strong> longer durations in cases complicated by<br />

postoperative bleeding. When unexpected postoperative<br />

bleeding occurs, several strategies may apply,<br />

including adjustment <strong>of</strong> dosing or replacement <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

current haemostatic agent, cessation <strong>of</strong> rehabilitative<br />

measures, or platelet transfusion if <strong>the</strong>re is thrombocytopenia<br />

or evidence <strong>of</strong> platelet dysfunction [13].<br />

Consultation <strong>with</strong> <strong>the</strong> haematology team in <strong>the</strong> event<br />

<strong>of</strong> excessive postoperative bleeding is critical.<br />

Discharge planning for home, rehabilitative, or<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r facilities should be an integral part <strong>of</strong> preoperative<br />

assessment <strong>and</strong> should include an evaluation <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> home environment <strong>and</strong> psychosocial support system<br />

by <strong>the</strong> HTC. To optimize outcomes, after<br />

discharge, ongoing communication <strong>with</strong> <strong>the</strong> HTC<br />

regarding home infusion <strong>the</strong>rapy, physical <strong>the</strong>rapy <strong>and</strong><br />

coordination <strong>of</strong> <strong>care</strong> is crucial.<br />

Conclusions<br />

<strong>Comprehensive</strong> <strong>care</strong> <strong>and</strong> advances in haemostatic<br />

treatments have made it possible to safely perform a<br />

wide array <strong>of</strong> surgical procedures, specifically in<br />

<strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong>, although restricted access to<br />

haemostatic treatments <strong>and</strong> comprehensive <strong>care</strong> in <strong>the</strong><br />

developing world poses additional challenges in <strong>the</strong><br />

surgical management <strong>of</strong> <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> CHwI. A coordinated<br />

series <strong>of</strong> peri- <strong>and</strong> intraoperative events carried<br />

out by <strong>the</strong> multidisciplinary HTC team will<br />

ensure optimal outcome in <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> CHwI undergoing<br />

surgery.<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Dr. Kulkarni contributed to <strong>the</strong> conceptualization, content <strong>and</strong> composition<br />

<strong>of</strong> this manuscript. Writing assistance was provided by Lara Primak,<br />

MD, <strong>of</strong> ETHOS Health Communications in Newtown, Pennsylvania,<br />

USA, <strong>with</strong> financial support from Novo Nordisk Inc, in compliance <strong>with</strong><br />

international Good Publication Practice guidelines. Dr. Kulkarni received<br />

no remuneration <strong>of</strong> any kind for <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> this manuscript.<br />

Disclosures<br />

Roshni Kulkarni is a consultant for Novo Nordisk, Baxter, Bayer, Octapharma<br />

<strong>and</strong> CSL Behring; is on <strong>the</strong> speakers’ bureau for Novo Nordisk<br />

<strong>and</strong> CSL Behring; <strong>and</strong> participates in clinical research protocols for Novo<br />

Nordisk, Baxter <strong>and</strong> Biogen Idec.<br />

References<br />

1 Coppola A, Di Capua M, Di Minno MN<br />

et al. Treatment <strong>of</strong> hemophilia: a review <strong>of</strong><br />

current advances <strong>and</strong> ongoing issues. J<br />

Blood Med 2010; 1: 183–95.<br />

2 Smith PS, Levine PH; Centers at DoEPH.<br />

The benefits <strong>of</strong> comprehensive <strong>care</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

hemophilia: a five-year study <strong>of</strong> outcomes.<br />

Am J Public Health 1984; 74: 616–7.<br />

3 Soucie JM, Nuss R, Evatt B et al. Mortality<br />

among males <strong>with</strong> hemophilia: relations<br />

<strong>with</strong> source <strong>of</strong> medical <strong>care</strong>. Blood 2000;<br />

96: 437–42.<br />

4 DiMichele D. Inhibitors in Hemophilia: A<br />

Primer. Treatment <strong>of</strong> Hemophilia, April<br />

2008, No. 7. Montreal, Quebec: World<br />

Federation <strong>of</strong> Hemophilia, 2008. Available<br />

at: http://www1.wfh.org/publication/files/<br />

pdf-1122.pdf. Accessed June 22, 2012.<br />

5 Valentino LA, Cooper DL, Goldstein B.<br />

Surgical experience <strong>with</strong> rFVIIa (NovoSeven)<br />

in congenital <strong>haemophilia</strong> A <strong>and</strong> B<br />

<strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong> to factor VIII or<br />

IX. Haemophilia 2011; 17: 579–89.<br />

6 Rodriguez-Merchan EC, Jimenez-Yuste V,<br />

Gomez-Cardero P, Alvarez-Roman M, Martin-Salces<br />

M, Rodriguez de la Rua A. Surgery<br />

in <strong>haemophilia</strong> <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong>,<br />

<strong>with</strong> special emphasis on orthopaedics:<br />

Madrid experience. Haemophilia 2010; 16:<br />

84–8.<br />

7 Mauser-Bunschoten E, Roosendaal G,<br />

Schutgens R, Fischer K. Comorbidity in <strong>the</strong><br />

aging <strong>haemophilia</strong> <strong>patient</strong>. Haemophilia<br />

2008; 14: 128. Abstract 22 PO 07.<br />

8 Teitel JM, Carcao M, Lillicrap D et al.<br />

Orthopaedic surgery in <strong>haemophilia</strong><br />

<strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong>: a practical guide to<br />

haemostatic, surgical <strong>and</strong> rehabilitative<br />

<strong>care</strong>. Haemophilia 2009; 15: 227–39.<br />

9 Aouba A, Dezamis E, Sermet A et al.<br />

Uncomplicated neurosurgical resection <strong>of</strong> a<br />

malignant glioneural tumour under haemostatic<br />

cover <strong>of</strong> rFVIIa in a severe <strong>haemophilia</strong><br />

<strong>patient</strong> <strong>with</strong> a high-titre inhibitor: a<br />

case report <strong>and</strong> literature review <strong>of</strong> rFVIIa<br />

use in major surgeries. Haemophilia 2010;<br />

16: 54–60.<br />

10 Quintana-Molina M, Martinez-Bahamonde<br />

F, Gonzalez-Garcia E et al. Surgery in<br />

haemophilic <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> inhibitor:<br />

20 years <strong>of</strong> experience. Haemophilia 2004;<br />

10: 30–40.<br />

11 Shapiro A, Cooper DL, U. S. survey <strong>of</strong> surgical<br />

capabilities experience <strong>with</strong> surgical<br />

procedures in <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> congenital <strong>haemophilia</strong><br />

<strong>with</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong>. Haemophilia<br />

2012; 18: 400–5.<br />

12 Sheth S, DiMichele D, Lee M et al. Heart<br />

transplant in a factor VIII-deficient <strong>patient</strong><br />

<strong>with</strong> a high-titre inhibitor: perioperative<br />

management using high-dose continuous<br />

infusion factor VIII <strong>and</strong> recombinant factor<br />

VIIa. Haemophilia 2001; 7: 227–32.<br />

13 Giangr<strong>and</strong>e PL, Wilde JT, Madan B et al.<br />

Consensus protocol for <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> recombinant<br />

activated factor VII [eptacog alfa<br />

(activated); NovoSeven] in elective orthopaedic<br />

surgery in haemophilic <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong><br />

<strong>inhibitors</strong>. Haemophilia 2009; 15: 501–8.<br />

14 Wiedel J, Stabler S, Geraghty S, Funk S.<br />

Joint Replacement Surgery in Hemophilia.<br />

Treatment <strong>of</strong> Hemophilia, June 2010, No.<br />

50. Montreal, Quebec: World Federation<br />

<strong>of</strong> Hemophilia, 2010. Available at: http://<br />

www1.wfh.org/publication/files/pdf-1210.<br />

pdf. Accessed June 22, 2012.<br />

15 Solimeno LP, Mancuso ME, Pasta G, Santagostino<br />

E, Perfetto S, Mannucci PM. Factors<br />

influencing <strong>the</strong> long-term outcome <strong>of</strong><br />

primary total knee replacement in <strong>haemophilia</strong>cs:<br />

a review <strong>of</strong> 116 procedures at a<br />

single institution. Br J Haematol 2009;<br />

145: 227–34.<br />

16 Durkin MT, Mercer KG, McNulty MF<br />

et al. Vascular surgical society <strong>of</strong> Great<br />

Britain <strong>and</strong> Irel<strong>and</strong>: contribution <strong>of</strong> malnutrition<br />

to postoperative morbidity in vascular<br />

surgical <strong>patient</strong>s. Br J Surg 1999; 86:<br />

702.<br />

17 Rodriguez-Merchan EC. Surgical wound<br />

healing in bleeding disorders. Haemophilia<br />

2012; 18: 487–90.<br />

18 Rajpurkar M, Boldt-Macdonald K, McLenon<br />

R et al. Ethanol lock <strong>the</strong>rapy for <strong>the</strong><br />

treatment <strong>of</strong> ca<strong>the</strong>ter-related infections in<br />

<strong>haemophilia</strong> <strong>patient</strong>s. Haemophilia 2009;<br />

15: 1267–71.<br />

19 Crnich CJ, Halfmann JA, Crone WC, Maki<br />

DG. The effects <strong>of</strong> prolonged ethanol exposure<br />

on <strong>the</strong> mechanical properties <strong>of</strong> polyurethane<br />

<strong>and</strong> silicone ca<strong>the</strong>ters used for<br />

intravascular access. Infect Control Hosp<br />

Epidemiol 2005; 26: 708–14.<br />

20 Aryal KR, Wiseman D, Siriwardena AK,<br />

Bolton-Maggs PHB, Hay CRM, Hill J.<br />

General surgery in <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> a bleeding<br />

dia<strong>the</strong>sis: how we do it. World J Surg<br />

2011; 35: 2603–10.<br />

21 Shibata M, Nakagawa T, Akioka S et al.<br />

Hemostatic treatment using factor VIII concentrates<br />

for neutralizing high-responding<br />

<strong>inhibitors</strong> prior to CVAD insertion for<br />

© 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd Haemophilia (2013), 19, 2–10

10 R. KULKARNI<br />

immune-tolerance induction <strong>the</strong>rapy. Clin<br />

Appl Thromb Hemost 2012; 18: 66–71.<br />

22 Negrier C, Goudem<strong>and</strong> J, Sultan Y, Bertr<strong>and</strong><br />

M, Rothschild C, Lauroua P. Multicenter<br />

retrospective study on <strong>the</strong> utilization <strong>of</strong> FEI-<br />

BA in France in <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> factor VIII <strong>and</strong><br />

factor IX <strong>inhibitors</strong> French FEIBA Study<br />

Group. Factor Eight Bypassing Activity.<br />

Thromb Haemost 1997; 77: 1113–9.<br />

23 Lopez-Vilchez I, Hedner U, Altisent C,<br />

Diaz-Ricart M, Escolar G, Galan AM.<br />

Redistribution <strong>and</strong> hemostatic action <strong>of</strong><br />

recombinant activated factor VII associated<br />

<strong>with</strong> platelets. Am J Pathol 2011; 178:<br />

2938–48.<br />

24 Kulkarni R, Aledort LM, Berntorp E et al.<br />

Therapeutic choices for <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong><br />

hemophilia <strong>and</strong> high-titer <strong>inhibitors</strong>. Am J<br />

Hematol 2001; 67: 240–6.<br />

25 Ma<strong>the</strong>ws V, Nair SC, David S, Viswab<strong>and</strong>ya<br />

A, Srivastava A. Management <strong>of</strong> hemophilia<br />

in <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong>: <strong>the</strong><br />

perspective from developing countries.<br />

Semin Thromb Hemost 2009; 35: 820–6.<br />

26 Prabhu R, Jijina F, Shetty S, Ghosh K. Successful<br />

surgery in severe <strong>haemophilia</strong> – a<br />

two-stage replacement <strong>the</strong>rapy in resourcepoor<br />

countries. Haemophilia 2008; 14:<br />

1125–6.<br />

27 Balkan C, Karapinar D, Aydogdu S et al.<br />

Surgery in <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>haemophilia</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

high responding <strong>inhibitors</strong>: Izmir experience.<br />

Haemophilia 2010; 16: 902–9.<br />

28 Boadas A, Fern<strong>and</strong>ez-Palazzi F, De Bosch<br />

NB, Cedeno M, Ruiz-Saez A. Elective surgery<br />

in <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> congenital coagulopathies<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong>: experience <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

National Haemophilia Centre <strong>of</strong> Venezuela.<br />

Haemophilia 2011; 17: 422–7.<br />

29 Caviglia H, C<strong>and</strong>ela M, Galatro G, Neme<br />

D, Moretti N, Bianco RP. Elective orthopaedic<br />

surgery for <strong>haemophilia</strong> <strong>patient</strong>s<br />

<strong>with</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong>: single centre experience <strong>of</strong><br />

40 procedures <strong>and</strong> review <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> literature.<br />

Haemophilia 2011; 17: 910–9.<br />

30 Ingerslev J. Efficacy <strong>and</strong> safety <strong>of</strong> recombinant<br />

factor VIIa in <strong>the</strong> prophylaxis <strong>of</strong><br />

bleeding in various surgical procedures in<br />

hemophilic <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> factor VIII <strong>and</strong><br />

factor IX <strong>inhibitors</strong>. Semin Thromb<br />

Hemost 2000; 26: 425–32.<br />

31 Takedani H, Kawahara H, Kajiwara M.<br />

Major orthopaedic surgeries for <strong>haemophilia</strong><br />

<strong>with</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong> using rFVIIa. Haemophilia<br />

2010; 16: 290–5.<br />

32 Obergfell A, Auvinen MK, Ma<strong>the</strong>w P.<br />

Recombinant activated factor VII for<br />

<strong>haemophilia</strong> <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong> undergoing<br />

orthopaedic surgery: a review <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

literature. Haemophilia 2008; 14: 233–<br />

41.<br />

33 Rodriguez-Merchan EC, Rocino A,<br />

Ewenstein B et al. Consensus perspectives<br />

on surgery in <strong>haemophilia</strong> <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong><br />

<strong>inhibitors</strong>: summary statement. Haemophilia<br />

2004; 10(Suppl. 2): 50–2.<br />

34 Caviglia H, Narayan P, Forsyth A et al.<br />

Musculoskeletal problems in persons <strong>with</strong><br />

<strong>inhibitors</strong>: how do we treat Haemophilia<br />

2012; 18(Suppl. 4): 54–60.<br />

35 Kraut EH, Aledort LM, Arkin S, Stine KC,<br />

Wong WY. Surgical interventions in a<br />

cohort <strong>of</strong> <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>haemophilia</strong> A <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>inhibitors</strong>: an experiential retrospective<br />

chart review. Haemophilia 2007; 13:<br />

508–17.<br />

36 Lauroua P, Ferrer AM, Guerin V. Successful<br />

major <strong>and</strong> minor surgery using factor<br />

VIII inhibitor bypassing activity in <strong>patient</strong>s<br />

<strong>with</strong> <strong>haemophilia</strong> A <strong>and</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong>. Haemophilia<br />

2009; 15: 1300–7.<br />

37 Rangarajan S, Yee TT, Wilde J. Experience<br />

<strong>of</strong> four UK comprehensive <strong>care</strong><br />

centres using FEIBA ® for surgeries in<br />

<strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong>. Haemophilia<br />

2011; 17: 28–34.<br />

38 Tjonnfjord GE. Activated prothrombin<br />

complex concentrate (FEIBA) treatment<br />

during surgery in <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong> to<br />

FVIII/IX: <strong>the</strong> updated Norwegian experience.<br />

Haemophilia 2004; 10: 41–5.<br />

39 Zülfikar B, Aydogan G, Salcioglu Z et al.<br />

Efficacy <strong>of</strong> FEIBA for acute bleeding <strong>and</strong><br />

surgical haemostasis in <strong>haemophilia</strong> A<br />

<strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong>: a multicentre registry<br />

in Turkey. Haemophilia 2012; 18:<br />

383–91.<br />

40 Ingerslev J, Sorensen B. Parallel use <strong>of</strong> bypassing<br />

agents in <strong>haemophilia</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong>:<br />

a critical review. Br J Haematol 2011;<br />

155: 256–62.<br />

41 Dargaud Y, Lienhart A, Negrier C.<br />

Prospective assessment <strong>of</strong> thrombin generation<br />

test for dose monitoring <strong>of</strong> bypassing<br />

<strong>the</strong>rapy in hemophilia <strong>patient</strong>s <strong>with</strong> <strong>inhibitors</strong><br />

undergoing elective surgery. Blood<br />

2010; 116: 5734–7.<br />

42 Pivalizza EG, Escobar MA. Thrombelastography-guided<br />

factor VIIa <strong>the</strong>rapy in a surgical<br />

<strong>patient</strong> <strong>with</strong> severe hemophilia <strong>and</strong><br />

factor VIII inhibitor. Anesth Analg 2008;<br />

107: 398–401.<br />

43 Escobar MA. Recombinant factor VIIa: <strong>the</strong><br />

possibilities for monitoring. Transfus Altern<br />

Transfus Med 2003; 5: 51–4.<br />

44 Holmström M, Tran HT, Holme PA. Combined<br />