Finishing the Bridge to Diversity - Member Profile - AAMC

Finishing the Bridge to Diversity - Member Profile - AAMC

Finishing the Bridge to Diversity - Member Profile - AAMC

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

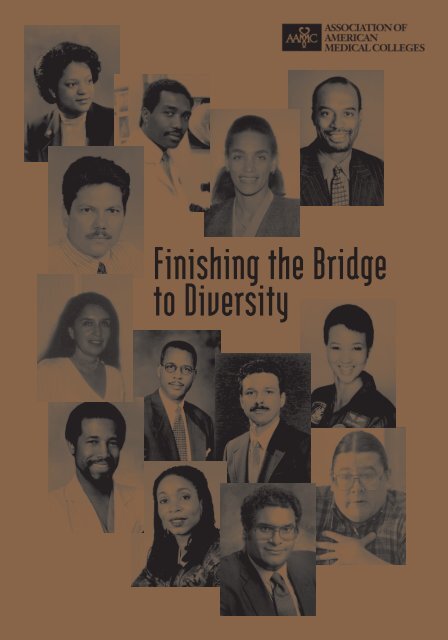

<strong>Finishing</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Bridge</strong><br />

<strong>to</strong> <strong>Diversity</strong>

1<br />

5<br />

6<br />

10<br />

2 4<br />

3<br />

9<br />

7<br />

8<br />

11<br />

13<br />

12<br />

1. Regina M. Benjamin, M.D., M.B.A., solo practitioner<br />

in Bayou La Batre, Alabama; member American<br />

Medical Association Board of Trustees<br />

2. Griffin P. Rodgers, M.D., Chief, Molecular Hema<strong>to</strong>logy,<br />

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and<br />

Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health<br />

3. Patrice Desvigne-Nickens, M.D., Direc<strong>to</strong>r, Heart<br />

Research Program, National Institutes of Health<br />

4. Mark D. Smith, M.D., M.B.A., President and Chief<br />

Executive Officer, California HealthCare Foundation<br />

5. Samuel M. Aguayo, M.D., F.A.C.P., F.C.C.P., Associate<br />

Chief of Staff/Education, Atlanta Veterans Affairs<br />

Medical Center, and Associate Professor of Medicine,<br />

Emory University School of Medicine<br />

6. Melvina McCabe, M.D., Associate Professor, Department<br />

of Family and Community Medicine, University of<br />

New Mexico School of Medicine<br />

7. Reed V. Tuckson, M.D., President, Charles R. Drew<br />

University of Medicine and Science<br />

8. Herbert W. Nickens, M.D., Vice President of<br />

Community and Minority Programs<br />

9. Mae C. Jemison, M.D., President, <strong>the</strong> Jemison Group;<br />

former NASA astronaut<br />

10. Benjamin S. Carson, M.D., Direc<strong>to</strong>r, Pediatric<br />

Neurosurgery, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions<br />

11. Helene D. Gayle, M.D., M.P.H., Direc<strong>to</strong>r, National<br />

Center for HIV, STD, and TB Prevention, Centers<br />

for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)<br />

12, Woodrow A. Myers, Jr., M.D., M.B.A., Direc<strong>to</strong>r, Health<br />

Care Management, Ford Mo<strong>to</strong>r Company<br />

13. Walter B. Hollow, M.D., Direc<strong>to</strong>r, Native American<br />

Center of Excellence, University of Washing<strong>to</strong>n<br />

School of Medicine<br />

This is a slightly edited version of <strong>the</strong> President’s Address presented November 8,<br />

1996 at <strong>the</strong> Plenary Session of <strong>the</strong> 107th Annual Meeting of <strong>the</strong> Association of<br />

American Medical Colleges (<strong>AAMC</strong>), held in San Francisco, November 6-12, 1996.<br />

Dr. Cohen is president of <strong>the</strong> <strong>AAMC</strong>, Washing<strong>to</strong>n, D.C.<br />

Correspondence and requests for reprints should be addressed <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> Office of<br />

<strong>the</strong> President at <strong>the</strong> <strong>AAMC</strong>, 2450 N Streeet, NW, Washing<strong>to</strong>n, DC 20037-1127.

1965 Residency Class, Harvard University School of Medicine

<strong>Finishing</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Bridge</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Diversity</strong><br />

<strong>Finishing</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Bridge</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Diversity</strong><br />

Jordan J. Cohen, M.D.<br />

I want <strong>to</strong> call you all <strong>to</strong> action.<br />

To take firm leadership on this<br />

issue. Leadership in educating<br />

<strong>the</strong> best doc<strong>to</strong>rs. Leadership in<br />

providing quality health care.<br />

And leadership in finding answers<br />

<strong>to</strong> major health problems.<br />

FFor my part <strong>to</strong>day, I have chosen <strong>to</strong> discuss a more longstanding challenge.<br />

One that has been with us much longer than ei<strong>the</strong>r managed care or Web<br />

pages. I want <strong>to</strong> talk about finishing <strong>the</strong> bridge <strong>to</strong> diversity. This bridge-building<br />

challenge differs a lot, I think, from o<strong>the</strong>rs that are commanding so much of<br />

our attention. For one thing, although <strong>the</strong> <strong>to</strong>ols we need for this work stem,<br />

as always, from carefully honed analyses of <strong>the</strong> data, those <strong>to</strong>ols must be<br />

sharpened for this particular task by something in addition <strong>to</strong> data — by<br />

deeply felt passion.<br />

My plan is <strong>to</strong> set forth <strong>the</strong> reasons why I think achieving diversity in<br />

medicine is so critical. I want <strong>to</strong> call your attention <strong>to</strong> some his<strong>to</strong>rical arguments,<br />

some practical arguments, and some moral arguments. In <strong>the</strong> end, I<br />

want <strong>to</strong> call you all <strong>to</strong> action. To take firm leadership on this issue. Leadership<br />

in educating <strong>the</strong> best doc<strong>to</strong>rs. Leadership in providing quality health care.<br />

And leadership in finding answers <strong>to</strong> major health problems. None of <strong>the</strong>se<br />

goals can be achieved, in my judgment, without taking leadership <strong>to</strong> bridge<br />

<strong>the</strong> appalling diversity gap that still separates medicine from <strong>the</strong> society it<br />

professes <strong>to</strong> serve.<br />

1

<strong>Finishing</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Bridge</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Diversity</strong><br />

The Challenge for Academic Medicine<br />

To establish <strong>the</strong> context for my remarks, let me review some familiar<br />

facts. The population of <strong>the</strong> United States continues <strong>to</strong> grow and will do so<br />

well in<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> next century (Figure 1). The truly dramatic change <strong>to</strong> come,<br />

however, is not <strong>the</strong> size<br />

Millions<br />

500<br />

400<br />

300<br />

200<br />

100<br />

Growth of US Population<br />

Today<br />

0<br />

1950 1970 1990 2010 2030 2050<br />

YEAR<br />

of our population but its<br />

composition. Our population<br />

is growing older,<br />

as every one knows, and<br />

it also is growing racially<br />

and ethnically more<br />

diverse (Figure 2).<br />

Minority populations are<br />

increasing much more<br />

rapidly in this country<br />

than is <strong>the</strong> majority white<br />

population. As shown in<br />

Figure 2, between 1980<br />

and 1995, while our<br />

country’s white population<br />

Figure 1. Growth and projected growth<br />

of <strong>the</strong> U.S. population, 1950-2050.<br />

grew by about<br />

12%, our black<br />

population<br />

increased twice<br />

as fast, by<br />

about 24%;<br />

our Native<br />

American population<br />

grew<br />

by 57%; our<br />

Hispanic population,<br />

by 83%;<br />

and our Asian<br />

population, by<br />

more than<br />

Percent<br />

200<br />

150<br />

100<br />

50<br />

0<br />

Recent Growth in Subgroups<br />

of US Population<br />

12%<br />

24%<br />

57%<br />

83%<br />

160%<br />

White Black Native Hispanic Asian<br />

American<br />

Figure 2. Increases, in percentages, of subgroups of <strong>the</strong> U.S. population, 1980-1995.<br />

2

<strong>Finishing</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Bridge</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Diversity</strong><br />

160%. The result, as<br />

shown in Figure 3, is<br />

that somewhere in <strong>the</strong><br />

middle of <strong>the</strong> next century,<br />

<strong>the</strong> majority of our<br />

citizens will be members<br />

of minority groups.<br />

So what What do<br />

<strong>the</strong>se striking demographic<br />

trends describing <strong>the</strong><br />

future complexion of<br />

America have <strong>to</strong> do with<br />

our responsibilities as<br />

stewards of medicine’s<br />

future I find <strong>the</strong> answer<br />

<strong>to</strong> that question pretty<br />

straightforward. Academic<br />

medicine is, after all, largely<br />

about <strong>the</strong> future. It’s about<br />

Percent<br />

100<br />

80<br />

60<br />

40<br />

20<br />

The Future Complexion<br />

of America<br />

0<br />

1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 2030 2040 2050<br />

YEAR<br />

improving <strong>the</strong> health of future generations by educating <strong>the</strong> physicians who<br />

will care for <strong>to</strong>morrow’s children, and by discovering better ways <strong>to</strong> keep<br />

<strong>to</strong>morrow’s children healthy. Given that our primary obligation <strong>to</strong> society is <strong>to</strong><br />

furnish it with a physician workforce appropriate <strong>to</strong> its needs, our mandate is<br />

<strong>to</strong> select and prepare students for <strong>the</strong> profession who, in <strong>the</strong> aggregate, bear a<br />

reasonable resemblance <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> racial, ethnic, and of course, gender profiles of<br />

<strong>the</strong> people <strong>the</strong>y<br />

will serve. In<br />

Academic medicine is, after all, largely about <strong>the</strong> future. It’s about<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r words, a<br />

improving <strong>the</strong> health of future generations by educating <strong>the</strong> physicians<br />

medical profession<br />

that looks<br />

who will care for <strong>to</strong>morrow’s children, and by discovering better ways<br />

like America. We <strong>to</strong> keep <strong>to</strong>morrow’s children healthy.<br />

have made substantial<br />

progress on this front with respect <strong>to</strong> gender; but, as <strong>the</strong>se data suggest,<br />

we’ve still got a long, long way <strong>to</strong> go with respect <strong>to</strong> race and ethnicity.<br />

But why should anyone care if <strong>the</strong> medical profession reflects society’s<br />

racial and ethnic makeup as long as we have plenty of well-trained practitioners<br />

of whatever background The reasons are many. Let me mention five that<br />

stand out in my mind:<br />

Asian<br />

Hispanic<br />

Native<br />

American<br />

Black<br />

White<br />

Figure 3. Changes and projected changes in <strong>the</strong> relative sizes of five racial-ethnic groups in <strong>the</strong><br />

U.S. population, 1980-2050.<br />

3

<strong>Finishing</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Bridge</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Diversity</strong><br />

Achieving Justice and Equity<br />

First is <strong>the</strong> simple matter of justice and equity. The medical profession,<br />

and <strong>the</strong> health professions in general, occupy a lofty status in American society,<br />

and offer those who pursue <strong>the</strong>m many of <strong>the</strong> most challenging and rewarding<br />

career opportunities available anywhere. As physicians, for us <strong>to</strong> seek justice<br />

within our own profession is, I believe, only <strong>to</strong> be faithful <strong>to</strong> our cardinal<br />

commitment <strong>to</strong> respect everyone’s individuality equally.<br />

Ensuring Access <strong>to</strong> Health Care<br />

The second reason is a matter of improved access <strong>to</strong> health care for <strong>the</strong><br />

underserved. Abundant data now exist <strong>to</strong> document unequivocally that black,<br />

Hispanic, and native American physicians are much more likely than whites and<br />

Asians <strong>to</strong> practice in underserved communities. Not that minority physicians<br />

are, or should be, under any obligation <strong>to</strong> do so; not that minority physicians<br />

are not, and should not be, free <strong>to</strong> settle and practice wherever and however<br />

<strong>the</strong>y choose; and not that o<strong>the</strong>r physicians do not contribute importantly <strong>to</strong><br />

improving access among <strong>the</strong> underserved. The simple fact is that minority<br />

physicians do so with greater predictability. And getting <strong>the</strong> job done means<br />

producing more minority physicians <strong>to</strong> lead <strong>the</strong> way.<br />

Providing Culturally Competent Care<br />

The third reason for increasing diversity among our students — and<br />

faculty, I might add — has <strong>to</strong> do with learning how <strong>to</strong> deliver culturally competent<br />

care. Given <strong>the</strong><br />

expanding<br />

Learning how <strong>to</strong> deliver culturally competent care means learning<br />

diversity<br />

medicine with students and from faculty who are <strong>the</strong>mselves emblematic<br />

throughout our<br />

of society’s diversity. Textbooks alone just won’t cut it.<br />

society, all<br />

physicians of<br />

<strong>the</strong> future will need this essential skill, and must be given a strong foundation<br />

in what it means <strong>to</strong> deliver culturally competent care.<br />

If <strong>the</strong>y are truly <strong>to</strong> care for <strong>the</strong>ir diverse patients, physicians of whatever<br />

background must have a firm grasp on how various belief systems, cultural<br />

biases, family structures, his<strong>to</strong>rical realities, and a host of o<strong>the</strong>r culturally<br />

determined fac<strong>to</strong>rs influence <strong>the</strong> way people experience illness and <strong>the</strong> way<br />

<strong>the</strong>y respond <strong>to</strong> advice and treatment. Such differences are real and translate<br />

in<strong>to</strong> real differences in <strong>the</strong> outcomes of care. But should you find this argument<br />

unconvincing, let me remind you of a pragmatic consideration — of <strong>the</strong><br />

4

<strong>Finishing</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Bridge</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Diversity</strong><br />

increasing importance of cus<strong>to</strong>mer satisfaction. As our patients become culturally<br />

more diverse, our ability <strong>to</strong> meet <strong>the</strong>ir culturally determined expectations will<br />

strongly influence <strong>the</strong>ir choice of caregivers. The connection between all of<br />

this and <strong>the</strong> need <strong>to</strong> expand diversity in <strong>the</strong> educational environment is clear.<br />

Learning how <strong>to</strong> deliver culturally competent care means learning medicine<br />

with students and from faculty who are <strong>the</strong>mselves emblematic of society’s<br />

diversity. Textbooks alone just won’t cut it.<br />

Setting an Appropriately Comprehensive Research Agenda<br />

A fourth reason for addressing diversity has <strong>to</strong> do with our research<br />

agenda. Our society as a whole is plagued by many unsolved health problems,<br />

many of which swirl disproportionately around our minority populations. Our<br />

country’s research agenda is set in large measure by those who have chosen<br />

careers in investigation. Individual investiga<strong>to</strong>rs, in turn, tend <strong>to</strong> do research<br />

on problems that <strong>the</strong>y “see” and have an interest in. And what people see, and<br />

what tickles <strong>the</strong>ir fancy, depends <strong>to</strong> a great extent on <strong>the</strong>ir particular cultural<br />

and ethnic filters. Recognizing all <strong>the</strong>se truths leads <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> reality that finding<br />

solutions <strong>to</strong> our country’s most recalcitrant health problems, even being able<br />

<strong>to</strong> conceptualize what <strong>the</strong> real problems actually are, will require a research<br />

workforce that is much more diverse racially, ethnically, and by gender than<br />

we now have. Creating that workforce begins with ensuring diversity among<br />

those admitted <strong>to</strong> our M.D. and Ph.D. educational programs.<br />

Securing <strong>the</strong> Talent Needed To Lead <strong>the</strong> Health Care Enterprise<br />

in<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> Twenty-first Century<br />

My fifth and final reason for <strong>the</strong> need <strong>to</strong> achieve diversity in <strong>the</strong> medical<br />

profession relates <strong>to</strong> management of <strong>the</strong> health care system. Physicians must<br />

continue <strong>to</strong> exert leadership — some would say re-exert leadership — in <strong>the</strong><br />

management of <strong>the</strong> health care enterprise, especially now that that enterprise<br />

is becoming<br />

increasingly We must draw <strong>the</strong> future physician leadership for our health care<br />

corporatized. systems... from a richly diverse pool of talent, adequately reflecting<br />

But assuming our country’s gender, racial, and ethnic mélange. It’s simply smart<br />

management<br />

business <strong>to</strong> do so.<br />

responsibility<br />

for a system destined <strong>to</strong> serve <strong>the</strong> health care needs of an increasingly diverse<br />

people is a job that can only be done well by equally diverse management<br />

teams. We must draw <strong>the</strong> future physician leadership for our health care sys-<br />

5

<strong>Finishing</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Bridge</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Diversity</strong><br />

Percent<br />

15<br />

12<br />

9<br />

6<br />

3<br />

0<br />

tems — as we must for all o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

professional and non-professional<br />

sec<strong>to</strong>rs of <strong>the</strong> American economy<br />

— from a richly diverse pool of talent,<br />

adequately reflecting our<br />

country’s gender, racial, and ethnic<br />

mélange. It’s simply smart business<br />

<strong>to</strong> do so.<br />

So, five reasons stand out for<br />

seeking diversity in <strong>the</strong> medical<br />

profession: achieving justice and<br />

equity; ensuring access <strong>to</strong> health<br />

care; providing culturally competent<br />

care; setting an appropriately comprehensive research agenda; and<br />

securing <strong>the</strong> talent needed <strong>to</strong> lead <strong>the</strong> health care enterprise in<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> twentyfirst<br />

century.<br />

Taking a His<strong>to</strong>rical Look<br />

How are we doing Let’s take a his<strong>to</strong>rical look. Until <strong>the</strong> mid 1960s or<br />

so, <strong>the</strong> racial — and, of course, gender — composition of medical school classes,<br />

and hence of <strong>the</strong> medical<br />

Underrepresented Minorities<br />

US Population vs Medical School Matriculants<br />

% URMs in US Population<br />

1966<br />

1964<br />

1962<br />

1960<br />

1958<br />

1956<br />

1954<br />

1952<br />

1950<br />

% URM Matriculants<br />

YEAR<br />

Figure 4. The era before affirmative action: percentages of underrepresented minorities<br />

(URMs) in <strong>the</strong> U.S. population and as matriculants in medical schools, 1950-1966.<br />

Seeking <strong>Diversity</strong> in <strong>the</strong> Medical<br />

Profession Will Help Achieve:<br />

• Just and equitable access <strong>to</strong> rewarding careers<br />

• Improved access <strong>to</strong> health care for <strong>the</strong><br />

underserved<br />

• Culturally competent care<br />

• A comprehensive research agenda<br />

• Use of <strong>the</strong> rich and diverse pool of <strong>the</strong> nation’s<br />

talent <strong>to</strong> better manage <strong>the</strong> health care system.<br />

profession, was composed,<br />

mono<strong>to</strong>nously, of white men.<br />

As shown in Figure 4, despite<br />

a progressively expanding,<br />

double-digit presence in our<br />

population, groups that we<br />

now designate as underrepresented<br />

minorities made up<br />

only about 2% of medical<br />

school matriculants, and<br />

three-quarters of those<br />

attended ei<strong>the</strong>r Howard or<br />

Meharry. The typical medical<br />

school of that era admitted<br />

one minority student every<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r year. I graduated from<br />

medical school in 1960, one<br />

of <strong>the</strong> off years. In my class of<br />

6

<strong>Finishing</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Bridge</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Diversity</strong><br />

140, <strong>the</strong>re were 134 white men and six white women. And that was a banner<br />

year for women.<br />

In my 1965 residency class, <strong>the</strong>re were no women (except nurses), no blacks,<br />

no Hispanics, no Native Americans, not even an Asian American. Racial segregation<br />

was as fully evident in medicine as it was in virtually every sec<strong>to</strong>r of<br />

American society,<br />

just as it had In my 1965 residency class, <strong>the</strong>re were no women, no blacks, no Hispanics,<br />

been for many<br />

no Native Americans, not even an Asian American. Racial segregation<br />

preceding<br />

was as fully evident in medicine as it was in virtually every sec<strong>to</strong>r of<br />

decades. But<br />

things began <strong>to</strong><br />

American society, just as it had been for many preceding decades.<br />

change in <strong>the</strong><br />

late 1960s. The civil rights movement, <strong>the</strong> assassination of Martin Lu<strong>the</strong>r King,<br />

and a rash of urban riots woke many people up. And academic medicine was<br />

among <strong>the</strong> first <strong>to</strong> get <strong>the</strong> wake-up call. The result was a dramatic rise in <strong>the</strong><br />

admission of minorities <strong>to</strong> medical schools (Figure 5). Although not shown in<br />

Figure 5, women also began <strong>to</strong> matriculate in record numbers. Was this because<br />

scores on <strong>the</strong> Scholastic Aptitude Test, grade-point averages, and Medical College<br />

Admission Test scores of women and minority students suddenly began <strong>to</strong><br />

skyrocket. Of course not. What changed — what led <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> dramatic rise in<br />

women and minority matriculants <strong>to</strong> medical school — was simply that academic<br />

medicine began <strong>to</strong> take affirmative<br />

actions <strong>to</strong> increase <strong>the</strong><br />

racial, ethnic, and gender<br />

diversity of medical school<br />

classes.<br />

As shown in Figure 5,<br />

enrollment of underrepresented<br />

minorities in U.S.<br />

medical schools rose rapidly<br />

<strong>to</strong> about 8% of all matriculants<br />

by <strong>the</strong> early 1970s. But,<br />

as you can see, progress on<br />

our bridge <strong>to</strong> diversity stalled<br />

in <strong>the</strong> mid 1970s, with admissions<br />

remaining virtually flat<br />

for <strong>the</strong> next 15 years or so.<br />

To make matters worse, <strong>the</strong><br />

fraction of individuals from<br />

<strong>the</strong> same groups in <strong>the</strong> U.S.<br />

population that were under-<br />

Percent<br />

20<br />

15<br />

10<br />

5<br />

0<br />

1950<br />

The ’60s Wake Up Call<br />

% URM Matriculants<br />

1955<br />

1960<br />

% URMs in US Population<br />

1965<br />

1970<br />

YEAR<br />

Figure 5. Early success of affirmative action: percentages of underrepresented minorities<br />

(URMs) in <strong>the</strong> U.S. population and as matriculants in medical schools, 1950-1990, showing<br />

a sharp increase in <strong>the</strong> late 1960s as a result of affirmative actions.<br />

1975<br />

1980<br />

1985<br />

1990<br />

7

<strong>Finishing</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Bridge</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Diversity</strong><br />

represented in medicine continued <strong>to</strong> grow during this period, as shown in<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>to</strong>p line in Figure 5, increasing from 16% in 1975 <strong>to</strong> 19% in 1990. Our<br />

bridge <strong>to</strong> diversity, in o<strong>the</strong>r words, was less than halfway across <strong>the</strong> chasm,<br />

and <strong>the</strong> gap was widening under our eyes. Clearly it was time <strong>to</strong> call in <strong>the</strong><br />

engineers <strong>to</strong> reevaluate our bridge-building strategy. We did so, and <strong>the</strong> result<br />

was Project 3000 by 2000.<br />

Creating Partnerships<br />

When Bob Petersdorf announced this important initiative at <strong>the</strong> 1991<br />

meeting of this association just five years ago, he noted that <strong>the</strong> root cause of<br />

minority underrepresentation in medical schools in <strong>the</strong> present era is <strong>the</strong><br />

accumulated academic disadvantages borne by <strong>to</strong>o many minority young<br />

people simply because <strong>the</strong>y lack access <strong>to</strong> high-quality, precollege and college<br />

educations. As a consequence, groups of applicants from <strong>the</strong> various and<br />

diverse sec<strong>to</strong>rs of our population do not arrive at our admission offices with<br />

equivalent academic credentials. Clearly, <strong>the</strong> only satisfac<strong>to</strong>ry fix for this dilemma<br />

in <strong>the</strong> long run is fundamental reform of our country’s education system.<br />

And that is <strong>the</strong> core mission of Project 3000 by 2000: <strong>to</strong> contribute what<br />

we can — in concert with a host of o<strong>the</strong>r public and private initiatives — <strong>to</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> long-term solution for a very complex, multifac<strong>to</strong>rial, recalcitrant social<br />

catastrophe. As you know, <strong>the</strong> Project’s core strategy is <strong>to</strong> effect small-scale<br />

educational reform through<br />

durable, minority-focused community<br />

partnerships, partnerships<br />

among academic medical centers<br />

and those K-12 school systems and<br />

colleges that are responsible for <strong>the</strong><br />

academic preparation of potential<br />

underrepresented minority applicants.<br />

This is <strong>the</strong> novel element of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Project’s strategy: To create<br />

honest-<strong>to</strong>-God partnerships with<br />

selected feeder schools that will<br />

complement and reinforce <strong>the</strong> many<br />

useful approaches undertaken for<br />

years by many in <strong>the</strong> academic<br />

medicine community.<br />

Special programs, including<br />

magnet health science high schools,<br />

articulation agreements, and science<br />

Project 3000 by 2000<br />

Mission Statement<br />

To eliminate <strong>the</strong> underrepresentation of blacks,<br />

Native Americans, Mexican Americans, and Mainland<br />

Puer<strong>to</strong> Ricans in U.S. medical schools.<br />

Core Strategy<br />

To effect small-scale educational reform through durable,<br />

minority-focused partnerships of academic medical<br />

centers and those K-12 school systems and colleges<br />

that are responsible for <strong>the</strong> academic preparation of<br />

potential applicants from underrepresented minorities.<br />

Examples of What Works<br />

• Magnet health science high schools<br />

• Articulation agreements with feeder colleges<br />

• Science education partnerships<br />

• Early identification and fostering of interest and<br />

talent<br />

• Relationships with men<strong>to</strong>rs<br />

8

<strong>Finishing</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Bridge</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Diversity</strong><br />

education partnerships have been created <strong>to</strong> identify promising students early<br />

in <strong>the</strong> educational pipeline, <strong>to</strong> enrich <strong>the</strong> science and related offerings available<br />

<strong>to</strong> students<br />

from poorly This is <strong>the</strong> novel element of <strong>the</strong> Project’s strategy: To create honest-<strong>to</strong>equipped<br />

schools,<br />

God partnerships with selected feeder schools that will complement and<br />

<strong>to</strong> establish men<strong>to</strong>ring<br />

relation-<br />

reinforce <strong>the</strong> many useful approaches undertaken for years by many<br />

ships <strong>to</strong> keep <strong>the</strong> in <strong>the</strong> academic medicine community.<br />

flames of inquiry<br />

and aspiration burning intensely, and <strong>to</strong> provide adequate counseling <strong>to</strong> ensure<br />

that all <strong>the</strong> miles<strong>to</strong>nes on <strong>the</strong> long road <strong>to</strong> medical school are unders<strong>to</strong>od and met.<br />

What happened after <strong>the</strong> launch of Project 3000 by 2000 What happened<br />

was a second dramatic upturn in <strong>the</strong> number of underrepresented minorities<br />

admitted <strong>to</strong> medical school (Figure 6). Indeed, <strong>the</strong> number began <strong>to</strong> rise almost<br />

immediately and tracked right along <strong>the</strong> trajec<strong>to</strong>ry <strong>to</strong>ward <strong>the</strong> Project’s numerical<br />

goal of 3,000 new entrants <strong>to</strong> medical school among underrepresented groups<br />

by <strong>the</strong> turn of <strong>the</strong> century. In 1994, for <strong>the</strong> first time in his<strong>to</strong>ry, more than<br />

2,000 underrepresented minority students entered medical school, up from<br />

fewer than 1,500 in 1990.<br />

But how is this possible I just got through saying that Project 3000 by<br />

2000 was aiming at <strong>the</strong> long haul. How did it achieve such early success I<br />

think one reason, for sure, was <strong>the</strong> new attention focused by <strong>the</strong> Project on <strong>the</strong><br />

Percent<br />

25<br />

Project 3000 by 2000<br />

20<br />

15<br />

10<br />

% URMs in US Population<br />

% URM Matriculant<br />

1,470<br />

Matriculants<br />

2,014<br />

Matriculants<br />

12%<br />

10%<br />

5<br />

0<br />

1988 1990 1992 1994<br />

YEAR<br />

1970<br />

1966<br />

1962<br />

1958<br />

1954<br />

1950<br />

1994<br />

1990<br />

1986<br />

1982<br />

1978<br />

1974<br />

Figure 6. Temporary rise in <strong>the</strong> percentage of underrepresented minorities (URMs) who were matriculated in medical<br />

schools from 1990-1994. This upswing was partly due <strong>to</strong> increased attention that <strong>the</strong> launching of Project 3000 by 2000<br />

(shown by circle) focused on <strong>the</strong> lack of adequate racial and ethnic diversity among medical students.<br />

9

<strong>Finishing</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Bridge</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Diversity</strong><br />

lack of adequate racial and ethnic diversity among medical students. As a result,<br />

we saw a significant increase in <strong>the</strong> fraction of underrepresented minority<br />

applicants who gained acceptance at virtually every school. As it happens, we<br />

also got a boost from <strong>the</strong> rising tide of applicants during this same period; <strong>the</strong><br />

pool of minority applicants rose along with <strong>the</strong> pool of all applicants. Call it<br />

<strong>the</strong> Hawthorne effect if you like, but, in fact, <strong>the</strong> measurable progress made<br />

during this phase validated, once again, <strong>the</strong> power of affirmative action.<br />

Standing <strong>the</strong> Test<br />

The next critically important question <strong>to</strong> address, and one that <strong>the</strong> critics<br />

of affirmative action raise repeatedly, is whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> use of affirmative action as<br />

a <strong>to</strong>ol, and <strong>the</strong> resulting increase in <strong>the</strong> number of minority medical students,<br />

leads <strong>to</strong> unqualified individuals becoming doc<strong>to</strong>rs. To raise such a question is<br />

<strong>to</strong> concede ignorance of <strong>the</strong> facts. First of all, no one in <strong>the</strong>ir right mind would<br />

argue for admitting anyone <strong>to</strong> medical school who did not evidence <strong>the</strong> academic<br />

skills and personal<br />

No one in <strong>the</strong>ir right mind would argue for admitting anyone <strong>to</strong><br />

qualities necessary<br />

for completing<br />

medical school who did not evidence <strong>the</strong> academic skills and personal<br />

<strong>the</strong> M.D. degree.<br />

qualities necessary for completing <strong>the</strong> M.D. degree.<br />

Such an admission<br />

policy would not<br />

only violate our oath <strong>to</strong> patients, it would be a disastrous disservice <strong>to</strong> individual<br />

students. And <strong>the</strong> data clearly show that medical schools are keen <strong>to</strong> avoid this<br />

pitfall.<br />

The vast majority of medical students from underrepresented minority<br />

groups, as is true of all students admitted <strong>to</strong> medical school, do successfully<br />

complete <strong>the</strong> rigorous requirements for graduation. Medical school admission<br />

committees cannot be commended enough for <strong>the</strong> care <strong>the</strong>y take in selecting<br />

our country’s future physicians. That only a handful of students from all backgrounds,<br />

majority and minority alike, prove unable <strong>to</strong> withstand <strong>the</strong> rigors —<br />

or <strong>to</strong> meet <strong>the</strong> financial costs — of a medical education and must abandon <strong>the</strong><br />

quest along <strong>the</strong> line, is ample testimony <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> skill and wisdom of our admission<br />

committees.<br />

But let’s return <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> data for some less happy news. What is now evident,<br />

unfortunately, is that <strong>the</strong> initial upturn in <strong>the</strong> admission of underrepresented<br />

minorities following <strong>the</strong> launch of Project 3000 by 2000 leveled off in 1995,<br />

and, even more alarmingly, actually fell — by more than 100 individuals —<br />

among this year’s matriculants (Figure 7). After <strong>the</strong> his<strong>to</strong>ric high of 1994,<br />

something changed. Has Project 3000 by 2000 run out of steam Quite <strong>the</strong><br />

10

<strong>Finishing</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Bridge</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Diversity</strong><br />

Percent<br />

25<br />

Our <strong>Bridge</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Diversity</strong> is Sagging<br />

20<br />

15<br />

10<br />

% URMs in US Population<br />

% URM Matriculants<br />

2,014 URM<br />

Matriculants<br />

1,906 URM<br />

Matriculants<br />

12%<br />

10%<br />

5<br />

1972<br />

1968<br />

1964<br />

1960<br />

1956<br />

1952<br />

1996<br />

1992<br />

1988<br />

1984<br />

1980<br />

1976<br />

0<br />

1990 1992 1994 1996<br />

YEAR<br />

Figure 7. The bridge <strong>to</strong> diversity is sagging. The initial upturn in <strong>the</strong> admission of underrpresented minorities (URMs) following<br />

<strong>the</strong> launch of Project 3000 by 2000 leveled off in 1995 and <strong>the</strong>n fell by more than 100 individuals in 1996. This downturn<br />

was partly due <strong>to</strong> weakened, and sometimes blocked, affirmative actions.<br />

contrary. We learn of more and more educational partnerships and effective<br />

programs every year. As I’ve tried <strong>to</strong> emphasize, Project 3000 by 2000 is aimed<br />

at <strong>the</strong> long haul. The returns it will have on <strong>the</strong> investments it makes in educational<br />

partnerships will accumulate slowly over <strong>the</strong> next several years, even<br />

decades. It will take at least that long <strong>to</strong> fix <strong>the</strong> pipeline, <strong>to</strong> release us from <strong>the</strong><br />

need for short-term remedies.<br />

And it’s precisely those short-term remedies that may well be in jeopardy.<br />

What may be running out of steam, in o<strong>the</strong>r words, is <strong>the</strong> oomph behind affirmative<br />

action programs, programs designed <strong>to</strong> reach out not only <strong>to</strong> those<br />

qualified young people from underrepresented minority groups who are<br />

already in <strong>the</strong> applicant pool, but also <strong>to</strong> those who should be in <strong>the</strong> pool, and<br />

<strong>to</strong> those who, through short-term academic enrichment efforts, could qualify<br />

<strong>to</strong> enter <strong>the</strong> pool. The reason for being suspicious that weakened affirmative<br />

action efforts may be <strong>the</strong> culprit here is all <strong>to</strong>o obvious, given <strong>the</strong> way its use is<br />

being attacked on so many fronts.<br />

Chilling Conclusions<br />

For us in higher education, <strong>the</strong> Hopwood case was one of <strong>the</strong> most chilling<br />

pieces of evidence that affirmative action is under attack. As you know, <strong>the</strong><br />

decision of <strong>the</strong> U.S. Court of Appeals for <strong>the</strong> Fifth Circuit in that case, which<br />

11

<strong>Finishing</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Bridge</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Diversity</strong><br />

was let stand by <strong>the</strong> Supreme Court, has taken away <strong>the</strong> right of faculties in<br />

Texas, Mississippi, and Louisiana <strong>to</strong> use race and ethnicity at all as fac<strong>to</strong>rs in<br />

admission <strong>to</strong> any university program. And as of three days ago, with <strong>the</strong> passage<br />

of Proposition 209,<br />

our colleagues<br />

For us in higher education, <strong>the</strong> Hopwood case was one of <strong>the</strong> most<br />

here in California<br />

chilling pieces of evidence that affirmative action is under attack.<br />

are no longer<br />

free <strong>to</strong> consider<br />

race, ethnicity, or gender in admission decisions, in recruiting programs, or<br />

even in planning and implementing minority-targeted outreach activities, such<br />

as tu<strong>to</strong>ring programs and educational enrichment courses. California, Texas,<br />

Mississippi, and Louisiana: <strong>the</strong>se four states alone contain fully 35% of <strong>the</strong><br />

minority populations that remain underrepresented among medical students,<br />

and fully 75% of those from <strong>the</strong> Mexican-American community.<br />

Keeping <strong>Diversity</strong> in Academic Medicine’s Future<br />

Those who oppose affirmative action, and I know many of you do, argue<br />

ei<strong>the</strong>r that it’s no longer needed, or that it’s ineffective, or that it’s unfair. Looking<br />

at this contentious issue from <strong>the</strong> vantage point of <strong>the</strong> medical profession, I<br />

maintain that all three of those arguments are false.<br />

Is affirmative action in medical school admission still needed<br />

Absolutely. Until <strong>the</strong> academic credentials of all groups in <strong>the</strong> applicant pool<br />

are indistinguishable, we simply cannot use <strong>the</strong> same criteria <strong>to</strong> evaluate all<br />

applicants. Let me be absolutely clear. Given <strong>the</strong> disparity in available measures<br />

of academic achievement among applicants grouped by race and ethnicity, <strong>the</strong>re<br />

is simply no way<br />

We must continue, for as long as necessary, <strong>to</strong> reach out <strong>to</strong> those we can select an<br />

whose race and ethnicity, not <strong>the</strong>ir economic status alone, have adequately<br />

subjected <strong>the</strong>m <strong>to</strong> inferior academic preparations, but who, by dint diverse class of<br />

of character, intelligence, and drive, are fully prepared <strong>to</strong> succeed medical students<br />

as physicians and medical scientists.<br />

<strong>to</strong>day without<br />

taking race and<br />

ethnicity explicitly or implicitly in<strong>to</strong> account. Using surrogates for race and<br />

ethnicity can certainly help, but that approach is not an adequate substitute, in<br />

my mind, for being forthright about what is needed. We must continue, for as<br />

long as necessary, <strong>to</strong> reach out <strong>to</strong> those whose race and ethnicity, not <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

economic status alone, have subjected <strong>the</strong>m <strong>to</strong> inferior academic preparations,<br />

but who, by dint of character, intelligence, and drive, are fully prepared <strong>to</strong><br />

succeed as physicians and medical scientists.<br />

12

<strong>Finishing</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Bridge</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Diversity</strong><br />

Is affirmative action ineffective Certainly not in medicine. Indeed,<br />

nowhere is <strong>the</strong> effectiveness of affirmative action more in evidence than in our<br />

profession. Effective not only in narrowing our diversity gap, but effective in<br />

greatly expanding access <strong>to</strong> care.<br />

Is affirmative action unfair How in <strong>the</strong> world can it be unfair <strong>to</strong> boost<br />

<strong>the</strong> chances of becoming a physician — <strong>to</strong> give special treatment <strong>to</strong> persons<br />

who have been subjected <strong>to</strong> obscenely unfair discrimination because of <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

heritage, and whose status in our democratic society remains tarnished<br />

through no fault of <strong>the</strong>ir own. Okay, but how about being fair <strong>to</strong> all <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

applicants who don’t get <strong>the</strong> benefits of affirmative action. Look, we have many<br />

more qualified applicants <strong>to</strong> medical school than we have places for <strong>the</strong>m.<br />

Most applicants come away empty-handed, and do so for a whole variety of<br />

reasons. To single<br />

out affirmative<br />

If one of my kids or grandkids was rejected from medical school, I’d be<br />

action for <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

damned disappointed; but if <strong>the</strong>y tried <strong>to</strong> blame it on reverse discrimination,<br />

I’d say: Get a life.<br />

disappointment<br />

and plead unfair<br />

treatment just<br />

doesn’t compute. If one of my kids or grandkids was rejected from medical<br />

school, I’d be damned disappointed; but if <strong>the</strong>y tried <strong>to</strong> blame it on reverse<br />

discrimination, I’d say: Get a life. Because I believe it’s time already <strong>to</strong> share<br />

<strong>the</strong> wealth, <strong>to</strong> recognize that our profession needs — and our country needs<br />

— <strong>the</strong> best talent it can find from every group in our society.<br />

The Call <strong>to</strong> Action<br />

As much as we’d like <strong>to</strong> think o<strong>the</strong>rwise, and as much as we long for <strong>the</strong><br />

day when it’s no longer true, race and ethnicity still matter in America. To ignore<br />

that reality in deciding who deserves <strong>to</strong> be admitted <strong>to</strong> medical school is <strong>to</strong><br />

ignore our duty as stewards of our profession’s future. I can tell you that <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>AAMC</strong> does not intend <strong>to</strong> ignore its duty in this arena. As you may know, late<br />

last spring we spearheaded <strong>the</strong> formation of a new coalition, Health<br />

Professionals for <strong>Diversity</strong>. Over 30 of <strong>the</strong> nation’s leading medical, health, and<br />

education organizations have signed-on <strong>to</strong> this coalition, and we all have pledged<br />

<strong>to</strong> do whatever we can (1) <strong>to</strong> make <strong>the</strong> case for diversity in <strong>the</strong> healing professions,<br />

(2) <strong>to</strong> prevent <strong>the</strong> spread of anti-affirmative action initiatives, and (3) <strong>to</strong><br />

release <strong>the</strong> constraints that have already been imposed on many of our faculties.<br />

We must continue <strong>to</strong> produce physicians and scientists from all segments<br />

of America. We must remember how many young minority physicians, with<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir many talents and abundant energy, would have been lost <strong>to</strong> us if <strong>the</strong><br />

13

<strong>Finishing</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Bridge</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Diversity</strong><br />

enrollment practices from my era in medical school had not been reversed by<br />

affirmative action. But simply repeating <strong>the</strong> rhe<strong>to</strong>ric of <strong>the</strong> 1960s will not be<br />

enough. We must face up <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> fact that our society is being hammered at<br />

present by a mean-spirited backlash. Race has once again become a political<br />

“wedge” issue. A growing fraction of our citizens seems prepared <strong>to</strong> accept <strong>the</strong><br />

views expressed by some politicians that we can abandon affirmative action<br />

efforts, that we have come far enough in undoing <strong>the</strong> ravages our society<br />

suffered during<br />

We must face up <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> fact that our society is being hammered at present centuries of ugly<br />

by a mean-spirited backlash. Race has once again become a political subjugation by<br />

“wedge” issue.<br />

race, that our<br />

awful legacy of<br />

racial and ethnic discrimination is behind us. We have a judge in <strong>the</strong> Hopwood<br />

case, for example, who offers <strong>the</strong> opinion that race contributes no more <strong>to</strong> a<br />

person’s identity than does his or her blood type. One wonders what planet<br />

that judge is living on!<br />

All of us must speak out <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> opinion leaders and lawmakers in our<br />

communities. This is a moral issue, and it is a health issue. Hence, it is our issue.<br />

And <strong>the</strong> data are compelling. The consequence of abandoning affirmative<br />

action programs prematurely will be a reduction in <strong>the</strong> availability, and a<br />

deterioration in <strong>the</strong> quality, of health care services for everyone.<br />

In jurisdictions like <strong>the</strong> Fifth Circuit and in California, where prohibitions<br />

have been imposed on <strong>the</strong> use of race-conscious, affirmative-action <strong>to</strong>ols, we<br />

must work within <strong>the</strong> law <strong>to</strong> minimize <strong>the</strong> impact on minority enrollments. The<br />

<strong>AAMC</strong> will seek <strong>to</strong> develop and disseminate <strong>to</strong> those states whatever lawful alternatives<br />

we can find <strong>to</strong> ensure that qualified applicants from underrepresented<br />

minority groups continue <strong>to</strong> be identified and recruited <strong>to</strong> medical schools.<br />

We must redouble our efforts on behalf of Project 3000 by 2000. We must<br />

work <strong>to</strong> accelerate <strong>the</strong> establishment of meaningful educational partnerships<br />

with pipeline schools and encourage o<strong>the</strong>rs <strong>to</strong> join in <strong>the</strong> effort. Each of us, as<br />

citizens, needs <strong>to</strong><br />

In short, medicine must stay <strong>the</strong> course, we must not be afraid <strong>to</strong> lead. see our beleaguered<br />

pubic<br />

schools as <strong>the</strong> crucibles from which our future physicians will come, and use our<br />

privileged place in American society <strong>to</strong> be advocates and champions of education.<br />

In short, medicine must stay <strong>the</strong> course. We must not be afraid <strong>to</strong> lead.<br />

We must finish <strong>the</strong> bridge <strong>to</strong> diversity we began <strong>to</strong> build in <strong>the</strong> 1960s. We<br />

cannot allow thoughtless attacks on affirmative action <strong>to</strong> dismantle <strong>the</strong> fledgling<br />

structure we have yet <strong>to</strong> complete, a structure without which at least some of<br />

our minority colleagues would never have attained <strong>the</strong>ir dreams, never have healed<br />

a patient, never have discovered new knowledge, never have led an institution,<br />

never have inspired a student, and never have graced our profession.<br />

14