View the 2007 Companion Reader - OKLAHOMA chautauqua

View the 2007 Companion Reader - OKLAHOMA chautauqua

View the 2007 Companion Reader - OKLAHOMA chautauqua

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

ARTS & HUMANITIES COUNCIL OF TULSA

Good evening, and welcome to <strong>the</strong> <strong>2007</strong> Oklahoma Chautauqua. The Arts<br />

& Humanities Council of Tulsa in association with <strong>the</strong> Oklahoma Humanities<br />

Council is pleased to bring you <strong>the</strong> finest in living history re-enactors,<br />

providing life-long learning to <strong>the</strong> residents of five communities in Oklahoma<br />

– Altus, Enid, Ponca City, Tishomingo, and Tulsa!<br />

We are especially pleased to be able to provide this program free of charge,<br />

thanks to support from <strong>the</strong> Oklahoma Humanities Council and our presenting<br />

sponsor, The Mervin Bovaird Foundation. We also thank <strong>the</strong> additional sponsors<br />

listed on <strong>the</strong> back of this program.<br />

Special thanks to OSU-Tulsa for providing this wonderful event space and<br />

tent, as well as very helpful staff and volunteers. And to Williams for printing<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Companion</strong> <strong>Reader</strong>.<br />

I would also like to acknowledge our Chautauqua Committee chaired by<br />

Kate Reeves, as well as our Chautauqua Coordinator, Angela Fox, who work<br />

diligently to make this <strong>the</strong> largest (and best) living history program in <strong>the</strong><br />

State of Oklahoma!<br />

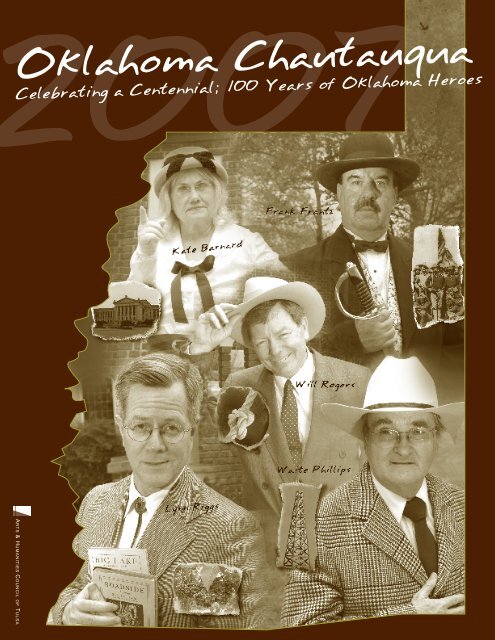

The <strong>the</strong>me for this year’s Chautauqua, Celebrating a Centennial: One Hundred<br />

Years of Oklahoma Heroes, took on very special meaning with <strong>the</strong> passing<br />

of a very dear friend of <strong>the</strong> Oklahoma Chautauqua, Oklahoma historian and<br />

biographer, Danney Goble. Danney performed <strong>the</strong> characters of Stephen<br />

Douglas, Clarence Darrow, James Longstreet, and Huey Long in <strong>the</strong> early years<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Oklahoma Chautauqua, and often attended <strong>the</strong> annual event. Bob<br />

Blackburn, executive director of <strong>the</strong> Oklahoma Historical Society, noted that<br />

Danney, “…had an endearing combination of wit and cynicism. Sometimes<br />

it got him into trouble, but he would look at you with that twinkle in his eye,<br />

and it was as if he were saying, ‘I got ‘em.’”<br />

We are dedicating this year’s Chautauqua to <strong>the</strong> memory of this very special<br />

man. Danney was very much an Oklahoma hero. And we will miss him!<br />

We hope you enjoy your time with us this year, celebrating <strong>the</strong> great people<br />

of <strong>the</strong> great state of Oklahoma! We look forward to seeing you again in 2008.<br />

Warm regards,<br />

Ken Busby<br />

Executive Director & CEO<br />

Arts & Humanities Council of Tulsa<br />

1

The first decade and a half of <strong>the</strong> Twentieth Century was a period of high<br />

hopes in <strong>the</strong> United States and in Oklahoma. These years, known as <strong>the</strong><br />

Progressive Era,witnessed an extraordinary outpouring of reform spirit as<br />

Americans joined to purge <strong>the</strong>ir nation of <strong>the</strong> evils which had risen from rapid<br />

industrialization, urbanization, and immigration. Heavily influenced by an<br />

unlikely amalgamation of <strong>the</strong> late Nineteenth Century philosophies of Social<br />

Darwinism, <strong>the</strong> Gospel of Wealth, and <strong>the</strong> Social Gospel and inspired by <strong>the</strong><br />

writings of a myriad of muckraking journalists, <strong>the</strong> progressives launched a<br />

veritable crusade to eradicate all that was wrong with society and man.<br />

Waite Phillips<br />

Page 4<br />

Kate Barnard<br />

Page 8<br />

Frank Frantz<br />

Page 12<br />

Lynn Riggs<br />

Page 16<br />

Will Rogers<br />

Page 20<br />

The infant state of Oklahoma, born of <strong>the</strong> belief that those who could best<br />

use <strong>the</strong> land should have it yet populated by many who lived on <strong>the</strong> edge of<br />

poverty, embraced progressivism, hoping to create a more humane political,<br />

social, and economic system which would serve as a shining example to<br />

its sibling states. Institutions and regulations created by <strong>the</strong> lengthy state<br />

Constitution reflected <strong>the</strong> desire to leave no stone unturned in <strong>the</strong> state’s<br />

efforts to curtail corruption, abuse of privilege, and social and economic<br />

inequities. For to its framers, this Constitution and <strong>the</strong> new state it created<br />

represented <strong>the</strong> last great hope for mankind- a final opportunity to ”get<br />

it right.” Thus on November 16, 1907, when people ga<strong>the</strong>red to witness<br />

<strong>the</strong> wedding of <strong>the</strong> cowboy and Indian maiden that symbolized <strong>the</strong> Twin<br />

Territories’ transformation into <strong>the</strong> single state of Oklahoma, hopes ran<br />

uncommonly high. Those that ga<strong>the</strong>red, be <strong>the</strong>y homesteaders, cowboys,<br />

Indians, laborers, oilmen, or politicians, firmly believed in <strong>the</strong> promise of<br />

perfectibility that ushered in <strong>the</strong> Twentieth Century. They included Frank<br />

Frantz who served as Oklahoma’s last Territorial Governor and hoped for a<br />

political career in <strong>the</strong> new state. There was also Kate Barnard, Oklahoma’s<br />

first Commissioner of Charities, who was concerned with <strong>the</strong> plight of<br />

<strong>the</strong> poor, laborers, children, and <strong>the</strong> incarcerated. Waite Phillips came to<br />

Oklahoma to join his bro<strong>the</strong>rs as an influential and prosperous figure in <strong>the</strong><br />

oil business. Will Rogers, born of an influential family in Indian Territory, left<br />

<strong>the</strong> state as a young man to find his place as asymbol of <strong>the</strong> common man on<br />

stage, in <strong>the</strong> movies, and in <strong>the</strong> press. Lynn Riggs, born outside Claremore,<br />

also found his destiny outside <strong>the</strong> state, but returned to his roots to write his<br />

most famous plays, including Green Grow <strong>the</strong> Lilacs.<br />

All of <strong>the</strong>se individuals possessed extraordinary talents and promise.<br />

However, dissatisfaction with <strong>the</strong>ir own achievements marked <strong>the</strong>ir careers.<br />

Driven individuals, <strong>the</strong>y each contributed a great deal to early Oklahoma,<br />

but <strong>the</strong>y died believing <strong>the</strong>y could have achieved more. In many ways, <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

careers mirror <strong>the</strong> fate of <strong>the</strong> high hopes that marked <strong>the</strong> inauguration of <strong>the</strong><br />

new century and <strong>the</strong> new state.<br />

Dr. Virginia Bellows,<br />

Associate Professor of History, Tulsa Community College<br />

Memorials, honorariums, and o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

endowment contributions may be<br />

made payable to:<br />

The Arts & Humanities Council of Tulsa<br />

2210 South Main Street<br />

Tulsa, Oklahoma 74114<br />

Sponsors<br />

In its 16th continuous year, <strong>the</strong> Oklahoma Chautauqua is a program of <strong>the</strong><br />

Arts & Humanities Council of Tulsa. Funding is provided in part by a grant<br />

from <strong>the</strong> Oklahoma Humanities Council and <strong>the</strong> National Endowment of <strong>the</strong><br />

Humanities. Major support for this program is provided by <strong>the</strong> following: The<br />

Mervin Bovaird Foundation, Oklahoma State University – Tulsa, Centennial<br />

Commission, We <strong>the</strong> People, Chesapeake Energy, Downtown Double Tree<br />

Hotel and Williams<br />

Chautauqua Committee Members<br />

2006-<strong>2007</strong><br />

Kate Reeves, Current Chair 2006-<strong>2007</strong><br />

Mark Barcus, Past Chair 2005-2006<br />

Angela Fox, Program Director<br />

Harry Dandelles<br />

Beverly Dieterlen<br />

Nancy Feldman<br />

Gini Fox<br />

Eleanore Graham<br />

Marilyn Inhofe-Tucker<br />

Jeffery Maxwell<br />

Patty McNeer<br />

Marilyn Mitchell<br />

Sandy Moore<br />

Ron Nick<br />

Victoria Peterson<br />

David Pettyjohn<br />

Paula Settoon<br />

Kim Smith<br />

Laurie Sundborg<br />

Janet Thomas<br />

Martin Wing<br />

______________________<br />

Layout/Design by Judy Sigl<br />

Photographs by John Fancher<br />

3

Waite Phillips: Oklahoma’s<br />

Centennial Oilman By Bill Worley<br />

Waite Phillips<br />

Born in Iowa as an identical twin and younger bro<strong>the</strong>r to <strong>the</strong> founders of Phillips Petroleum Company, Waite Phillips [1883-1964] experienced a classic 19th century rural<br />

American upbringing. He learned to farm and to wish to experience life beyond <strong>the</strong> farm. His identical twin Wiate died at age 19 after <strong>the</strong> two spent three years working <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

way across <strong>the</strong> American West.<br />

After a few years back in Iowa, Waite moved to Oklahoma to work for his older bro<strong>the</strong>r Frank in <strong>the</strong> oil fields near Bartlesville. In 1914, when Frank and bro<strong>the</strong>r L.E. Phillips<br />

contemplated leaving <strong>the</strong> oil business, Waite struck out on his own. Over <strong>the</strong> next decade he built one of <strong>the</strong> most effective independent oil companies in <strong>the</strong> country. Selling<br />

that in 1925, Waite turned to building in Tulsa and ranching in New Mexico. His office buildings and magnificent Tulsa residence [Philbrook] became late 1920s showplaces along<br />

with his New Mexico ranch [Philmont].<br />

In <strong>the</strong> late 1930s, Phillips contributed Philbrook to Tulsa for an art museum, Philmont to <strong>the</strong> Boy Scouts for a camping center, and his Philtower and Philcade buildings to each as<br />

endowments. After World War II, Waite and Genevieve Phillips moved to sou<strong>the</strong>rn California where he invested in real estate and continued giving away his fortune. Considered<br />

as one of <strong>the</strong> most philanthropic of all Oklahoma oilmen, Waite Phillips is a model of a successful businessman who gave back in untold measure.<br />

He was born in Iowa and died in California, living about 20 years in each state.<br />

But, it’s <strong>the</strong> 40 years he lived in Oklahoma that made Waite Phillips and helped<br />

make Oklahoma.<br />

At one level, Waite’s bro<strong>the</strong>rs were keys to his drive toward success in <strong>the</strong><br />

Oklahoma oil patch. Born an identical twin just after his bro<strong>the</strong>r Wiate, Waite<br />

seems to have lived his first 19 years somewhat in Wiate’s shadow. Wiate was<br />

minutes older but definitely <strong>the</strong> more assertive and risk-taking of <strong>the</strong> two. Sadly,<br />

Wiate died of appendicitis that developed into fatal peritonitis in Spokane,<br />

Washington in 1902.<br />

The tragic loss of his twin in 1902 ended a three-year sojourn for <strong>the</strong> bro<strong>the</strong>rs that<br />

took <strong>the</strong>m all over <strong>the</strong> American West and even into British Columbia. They worked<br />

and played in mining camps, booming cities and even spent a season trapping<br />

animals in <strong>the</strong> Rocky Mountains. Possibly it was this amazingly restless period that<br />

gave Waite his desire always to see what else could be done and what new places<br />

he could conquer. Clearly, <strong>the</strong> loss of Wiate forced him to take chances and discover<br />

new paths much more than he might ever have done on his own.<br />

Then, <strong>the</strong>re was Frank, Waite’s oldest bro<strong>the</strong>r [in a family with six boys and three<br />

girls living into adulthood]. Frank had <strong>the</strong> first-son urge from <strong>the</strong> beginning. He<br />

was <strong>the</strong> first of <strong>the</strong> Phillips bro<strong>the</strong>rs to come to Indian Territory, <strong>the</strong> first Phillips to<br />

drill successfully for oil, and <strong>the</strong> one who established what is today <strong>the</strong> larger half<br />

of Conoco-Phillips Petroleum. While Frank and Waite helped and admired each<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r, in business <strong>the</strong>y each wanted to be <strong>the</strong> boss.<br />

So, Waite Phillips got his oil field start with Frank and ano<strong>the</strong>r bro<strong>the</strong>r, L. E., in<br />

1906 in Indian Territory. Waite served as a field manager for <strong>the</strong> company that<br />

Frank and L. E. assembled out of Bartlesville as an oil and banking concern. For<br />

eight years Waite worked and learned <strong>the</strong> business. He literally started in <strong>the</strong> field<br />

by carrying supplies to <strong>the</strong> rigs, but ra<strong>the</strong>r quickly moved into <strong>the</strong> more responsible<br />

management positions.<br />

However, when Frank and L. E. seriously thought about leaving oil for banking in<br />

1914, <strong>the</strong> formerly cautious Waite struck out on his own. The death of his more<br />

risk-taking twin pushed Waite early in <strong>the</strong> century to take on some of Wiate’s<br />

personality. Marriage to Genevieve Elliott in 1909 [he had courted her for six years<br />

almost ever since Wiate died] only streng<strong>the</strong>ned his resolve and his restlessness.<br />

Initially, <strong>the</strong>y lived in Pawhuska, but moved to Bartlesville and built a home near<br />

<strong>the</strong> growing Frank Phillips compound.<br />

When he left Oklahoma briefly in 1914, Waite took <strong>the</strong> money gained from his<br />

sale of stock to Frank and L.E. and launched into buying leases and drilling wells.<br />

First in <strong>the</strong> Smackover/El Dorado district of Arkansas, <strong>the</strong>n returning to Oklahoma<br />

and <strong>the</strong> Okmulgee field, and ultimately all across eastern Oklahoma and sou<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

Kansas, <strong>the</strong> far-flung enterprises that he merged into <strong>the</strong> Waite Phillips Company<br />

in 1922 took shape.<br />

Oklahoma oil came in a series of discoveries of fields, pools and domes. Under <strong>the</strong><br />

“law of capture,” <strong>the</strong> first driller to tap into a pool could extract as much of <strong>the</strong><br />

crude oil as possible before o<strong>the</strong>rs sunk <strong>the</strong>ir wells to dilute <strong>the</strong> output. This led to<br />

a tremendous race in most fields to get <strong>the</strong>re “firstest with <strong>the</strong> mostest.” It meant<br />

that men like <strong>the</strong> Phillipses and o<strong>the</strong>rs had to lease widely and drill quickly. It<br />

was not always <strong>the</strong> most conservation-oriented approach, but it did create some<br />

fabulous fortunes for <strong>the</strong> men who got <strong>the</strong> leases and could borrow <strong>the</strong> money to<br />

finance <strong>the</strong> field operations.<br />

To direct this rapidly growing integrated empire of oil wells, pipelines, refineries<br />

and gasoline stations, Waite moved with Genevieve to Tulsa in 1918. That<br />

became home base until 1945. Interestingly, Waites developed his oil company<br />

into a complete line of <strong>the</strong> petroleum business from drilling to refining to retail<br />

distribution before Frank and L.E. even contemplated consolidating <strong>the</strong>ir efforts<br />

into Phillips Petroleum and opening <strong>the</strong> familiar “Phillips 66” service stations<br />

through <strong>the</strong> Midwest and Southwest.<br />

Waite and Genevieve’s daughter Helen Jane was born in 1911 in Bartlesville while<br />

Waite worked for Frank and L.E. Their son Elliott, nicknamed “Chope,” entered<br />

<strong>the</strong> world in 1918 in Okmulgee, just before <strong>the</strong> family moved to Tulsa. Helen<br />

Jane had difficulty coping with being an oilman’s daughter and lived a ra<strong>the</strong>r<br />

tragic life. “Chope” Phillips recognized that he loved <strong>the</strong> outdoors early on and<br />

always maintained a New Mexico ranch throughout his life. He expressed a bit of<br />

frustration when Waite donated Chope’s favorite, Philmont, to <strong>the</strong> Boy Scouts, but<br />

toge<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>y bought a neighboring ranch near Watrous, NM, which Chope worked<br />

<strong>the</strong> rest of his life.<br />

It was said that Waite could find oil almost by magic. Instead, what he really<br />

developed a keen eye for <strong>the</strong> lay of <strong>the</strong> land. While managing rigs for Frank and<br />

L.E. in <strong>the</strong> early days, he noticed that particular formations often yielded <strong>the</strong><br />

best results. Waite had only a sixth grade formal education, supplemented by a<br />

six-month business course taken in Iowa just after Wiate died. His skill in finding<br />

oil suggested that he might have made a great oil geologist had <strong>the</strong> opportunity<br />

been available.<br />

“The only things we keep are those<br />

we give away. All things should<br />

be put to <strong>the</strong>ir best possible use.”<br />

- Waite Phillips, Oil Man, p. 401.<br />

Waite Phillips built up a number of separate companies that he merged into <strong>the</strong><br />

Waite Phillips [or “Philco”] Company in 1922. He sold this in 1925 to a New York<br />

financial company that combined it with <strong>the</strong> Barnsdall Company. Waite received<br />

5

$25 million in cash. Largely, he became an investor and philanthropist from this<br />

point forward in his life.<br />

It is his philanthropic thrust which rested in part on his restless nature that<br />

resulted in <strong>the</strong> two greatest gifts of his lifetime—<strong>the</strong> donation of his family<br />

mansion named “Philbrook” in Tulsa and of his favorite ranch in New Mexico,<br />

“Philmont,” to <strong>the</strong> Boy Scouts of America. These two gifts created public entities<br />

that have educated and influenced generations of Oklahomans and Americans in<br />

<strong>the</strong> fine arts and in outdoor life.<br />

Philbrook stands as Tulsa’s jewel of <strong>the</strong> fine arts as it performs an extensive<br />

educational program for children and adults in addition to <strong>the</strong> daily opening<br />

With regard to <strong>the</strong> Native American<br />

of its marvelous galleries and rotating exhibits. Its marvelous grounds and<br />

art collection at Philbrook, Waite<br />

Phillips said: “Oil fortunes were<br />

made out of <strong>the</strong> Indian lands. I have<br />

a deep feeling of gratitude to <strong>the</strong><br />

American Indian and I want to see<br />

his culture preserved.” - Oil Man, p. 401.<br />

wonderfully varied rooms provide a delightful arts experience for Tulsa and <strong>the</strong><br />

whole of Oklahoma.<br />

Philmont is <strong>the</strong> signature camping experience for boys all over America. “Going<br />

to Philmont” becomes almost a rite of passage for Boy Scouts from Florida to<br />

Washington state and from California and Oklahoma to Maine and Massachusetts.<br />

Waite believed that gaining true outdoor experience should be a part of <strong>the</strong><br />

essential “growing up” experience of every American boy. Philmont provides that<br />

opportunity in a spectacular setting.<br />

Sources:<br />

Louis F. Burns, A History of <strong>the</strong> Osage People [Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama<br />

Press, 2004], especially Chapters 20 & 21, pp. 390-444. This entire study provides a<br />

wealth of information about this pivotal people in <strong>the</strong> history of Oklahoma.<br />

Michael Wallis, Beyond <strong>the</strong> Hills: The Journey of Waite Phillips [Oklahoma City:<br />

Oklahoma Heritage Association, 1995]. This biography is based heavily on<br />

<strong>the</strong> journals of Waite Phillips preserved by his son Elliott “Chope” Phillips.<br />

________, Oil Man: The Story of Frank Phillips and <strong>the</strong> Birth of Phillips Petroleum<br />

[New York: Doubleday, 1988]. Waite is a small character in <strong>the</strong> big drama<br />

of “Uncle Frank.” Both bro<strong>the</strong>rs contributed greatly to <strong>the</strong> making of<br />

Oklahoma along with <strong>the</strong> Osage people from under whose land Frank and<br />

Waite Phillips pumped “Black Gold.”<br />

Both Philbrook and <strong>the</strong> main house at Philmont were designed by famed Kansas<br />

City architect Edward Buehler Delk. Each remains an architectural masterpiece to<br />

<strong>the</strong> present day. Delk also designed Waite’s Philtower and his bro<strong>the</strong>r Frank’s town<br />

home in Bartlesville, as well as <strong>the</strong> mansion of H. V. Foster in that city.<br />

Just before his death in 1964, Waite Phillips wrote a late entry in his lifelong<br />

journal: “The only things we keep permanently are those we give away.” He and<br />

Genevieve had established ra<strong>the</strong>r deep roots in Los Angeles in <strong>the</strong> almost twenty<br />

years <strong>the</strong>y lived toge<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>re. Some of <strong>the</strong>ir generosity naturally flowed toward<br />

institutions and community efforts in that region as well.<br />

The Iowa farm boy who helped shape early Oklahoma and <strong>the</strong> American oil<br />

business died of heart failure in Bel Aire, California in January 1964, just after his<br />

81st birthday. Even in death he continued to give.<br />

His will provided $1 million to assist Boy Scouts to attend Philmont even though<br />

<strong>the</strong>y could not afford <strong>the</strong> experience financially. He left $1.5 million to various<br />

public and private institutions in sou<strong>the</strong>rn California and ano<strong>the</strong>r $2 million to<br />

Oklahoma institutions. $650,000 went to fur<strong>the</strong>r endow <strong>the</strong> Philbrook Art Center,<br />

$500,000 to <strong>the</strong> University of Tulsa, $650,000 to hospitals in Tulsa, Okmulgee and<br />

Bartlesville and $200,000 to <strong>the</strong> Tulsa YMCA.<br />

“The only things we keep are those<br />

we give away. All things should<br />

be put to <strong>the</strong>ir best possible use.”<br />

- Waite Phillips, Oil Man, p. 401.<br />

Oklahoma could not have benefited more from a native son or daughter. Waite and<br />

Genevieve Phillips received and gave back to Oklahoma in great measure. Waite<br />

became, along with some o<strong>the</strong>rs in <strong>the</strong> industry, oil’s way of creating a better<br />

Oklahoma for <strong>the</strong> 21st century.<br />

7

Kate Barnard: Intrepid<br />

Pioneer to Centennial Legend<br />

By Dixie Belcher<br />

Kate Barnard<br />

Kate Barnard (1875-1930) lived in Oklahoma Territory and worked as a secretary to <strong>the</strong> Territorial House of Representatives. While stumping for <strong>the</strong> Constitutional Convention she<br />

addressed <strong>the</strong> problems of child labor, sweatshops, tenements, and juvenile justice. She combined forces with Pete Hanraty on labor issues and Alfalfa Bill Murray on farm issues<br />

and was nominated as <strong>the</strong> only woman on <strong>the</strong> Democratic ticket for <strong>the</strong> office of Charities and Corrections. Known as <strong>the</strong> “good angel of Oklahoma” she won handily in Oklahoma’s<br />

first election as a new state and was <strong>the</strong> first woman to be elected in <strong>the</strong> United States to a major political office. In her reign as Commissioner from 1907-1915 she worked for<br />

child labor reform, compulsory education, better pay and working conditions, improved conditions in jails, hospitals and mental institutions. She uncovered scandals involving <strong>the</strong><br />

treatment of Oklahoma prisoners in Lansing, Kansas and <strong>the</strong> misuse of funding for Indian orphans by <strong>the</strong>ir guardians.<br />

Kate Barnard was one of <strong>the</strong> most revered women in Oklahoma in <strong>the</strong> early 1900s,<br />

known as “Our Kate, Oklahoma Kate, <strong>the</strong> Good Angel of Oklahoma, and Joan of Arc<br />

of Oklahoma” for her tireless work for Progressive reform. She was responsible for<br />

<strong>the</strong> legislation and implementation of social services and correctional programs that<br />

we take for granted today. A men’s correctional facility holds her name and a recent<br />

statue was commissioned for <strong>the</strong> state capitol rotunda. Sculptor Sandra VanZandt of<br />

Oologah a presents Kate in her inaugural dress sitting on a bench with a copy of her<br />

report in her lap. In 1994 Danney Goble mentions her in his Story of Oklahoma, in<br />

1997 Linda Willams Reese includes a chapter in Women of Oklahoma and in 2001 and<br />

2003 two biographies were published of her life by Bob Burke and Glenda Carlille,<br />

and Lynne Musslewhite and Suzanne Jones Crawford, respectively. Previous to that<br />

very little mention was made of <strong>the</strong> petite social reformer.<br />

The notable exceptions much earlier in <strong>the</strong> century, however, were Angie Debo’s<br />

And Still <strong>the</strong> Waters Run documentation of injustices toward Indians that Barnard<br />

uncovered during her last term of office and Ambassador Bryce of England’s<br />

compliment of Oklahoma’s constitution, giving Barnard credit, “It is <strong>the</strong> finest<br />

document of human liberty written since <strong>the</strong> Declaration of Independence, and <strong>the</strong><br />

credit for making it such is due, principally, to <strong>the</strong> activities of a single woman – Kate<br />

Barnard.” (Burke/Carlille)<br />

Why was <strong>the</strong>re such a long period of time between being adored and <strong>the</strong>n ignored<br />

Probably because her personality was rigid; she viewed <strong>the</strong> world in terms of rights<br />

and wrongs. This frame of mind was both her greatest asset and fault. Strangely she<br />

was unwilling to compromise while in office but former alliances brought her to <strong>the</strong><br />

attention of <strong>the</strong> men in power in <strong>the</strong> territory prior to statehood. In her late twenties<br />

she campaigned throughout <strong>the</strong> territory for an alliance between farmers and labor.<br />

Her speaking engagements filled halls and street corners with eager followers who<br />

cast <strong>the</strong> votes in Oklahoma’s first election as a new state. Kate championed her<br />

many causes in fiery editorials in <strong>the</strong> Daily Oklahoman and was considered an able<br />

spokesperson in print and at <strong>the</strong> podium. One press report described her as “sweet<br />

and dainty as a wild flower and as refreshing as an Oklahoma breeze.” (Musslewhite/<br />

Crawford) Oklahoma historian Angie Debo at age seventeen attended a speech given<br />

by Barnard and was moved by her eloquence and passion.<br />

Ms. Barnard posed challenges to <strong>the</strong> early pioneers, asking for <strong>the</strong>ir assistance in<br />

solving problems that children faced during this time. After one of her editorials,<br />

titled “What are we to do about our poor” citizens appeared at her door with<br />

clothing, bedding and furniture to be distributed to those in need. In 1906, <strong>the</strong> only<br />

real form of public communications was <strong>the</strong> newspaper, and Kate was <strong>the</strong> voice of <strong>the</strong><br />

people. The Territorial Legislature reacted to Kate’s popularity by declaring that <strong>the</strong><br />

Office of Charities and Corrections could be directed by a “he or a she.” Kate Biggers, a<br />

spokeswoman for suffrage ran on <strong>the</strong> opposing ticket. Barnard won <strong>the</strong> title of<br />

Commissioner of Charities and Corrections in Oklahoma’s first election as a new state<br />

and was <strong>the</strong> first woman to hold a major political office in <strong>the</strong> nation.<br />

Kate Barnard was born in Nebraska in 1875, although she only admitted to a<br />

birthdate of 1879. Her mo<strong>the</strong>r died when Kate was only 18 months old. She stated in<br />

an article for The Independent, “My mo<strong>the</strong>r died when I was young that I cannot even<br />

9<br />

remember her face. With her death <strong>the</strong> light on my pathway of life was blown out.” Her<br />

fa<strong>the</strong>r had a brief second marriage but Kate was estranged from her step-bro<strong>the</strong>r<br />

from this marriage and her two step-bro<strong>the</strong>rs from her mo<strong>the</strong>r’s first marriage. Kate<br />

had a difficult childhood living with maternal grandparents for a while and o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

relatives and in her teens traveling with her fa<strong>the</strong>r to several failed business ventures.<br />

She was thrilled to be called to help her fa<strong>the</strong>r in securing a claim in Oklahoma<br />

Territory in her teens. She lived alone on <strong>the</strong> claim while her fa<strong>the</strong>r practiced law in<br />

Oklahoma City. At age 16 she moved to a house he built on West Reno in Oklahoma<br />

City and was able to attend a catholic school.<br />

What she saw from her windows overlooking Reno Street were settlers like herself,<br />

only many with fewer resources. These people were ragged, hungry and homeless.<br />

After a brief stint as a teacher, Kate worked as a stenographer and <strong>the</strong>n served as<br />

director of <strong>the</strong> United Provident Society. She became more and more outraged by<br />

<strong>the</strong> lack of opportunities for <strong>the</strong> disadvantaged and wrote more editorials asking for<br />

assistance in caring for <strong>the</strong>m, not just with donated clothing and furniture but with<br />

jobs. A turning point was her appointment to promote <strong>the</strong> Oklahoma statehood<br />

exhibit at <strong>the</strong> St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904. During her time <strong>the</strong>re she toured <strong>the</strong><br />

slums and factories with a newspaper reporter who used Barnard’s descriptions of<br />

those circumstances, “No man can deal intelligently with life until he first understands<br />

how all classes of men live and under what conditions <strong>the</strong>y make <strong>the</strong>ir daily bread.<br />

Books are tools with which to work out human intelligence. How to apply this<br />

intelligence can only be learned by knowledge. To get this knowledge I spent months<br />

of life itself touring factories and workshops. I have brea<strong>the</strong>d coal dust with children<br />

in American coal breakers; I have turned sick with <strong>the</strong> pale young girls who are slowly<br />

poisoned as <strong>the</strong>y bottle arsenic in American drug houses; and I have brea<strong>the</strong>d <strong>the</strong> glass<br />

dust which was killing <strong>the</strong> child laborers at my side.” (Barnard)<br />

Historians David Baird and Danney<br />

Goble describe Barnard: Everything<br />

she asked for she got: an eighthour<br />

work day for state employees,<br />

prohibition of child labor in mines<br />

and factories, health and safety<br />

legislation for workers—and more.<br />

Even though women did not have <strong>the</strong> vote until 1920, <strong>the</strong> years in <strong>the</strong> early 1900s<br />

were charged with social change, primarily implemented by women. As volunteers<br />

<strong>the</strong>y gave of <strong>the</strong>ir time, energy and resources championing suffrage, prohibition,<br />

hygiene, improved working conditions and education. Barnard was at <strong>the</strong> forefront<br />

of all of <strong>the</strong>se movements, except suffrage. Although she believed in helping <strong>the</strong>

Kate Barnard addressing <strong>the</strong> Farmers if<br />

<strong>the</strong>y were to vote against Child Labor Law:<br />

I hope that in <strong>the</strong> fall of <strong>the</strong> year when <strong>the</strong><br />

sap goes out of your cornstalks and leaves<br />

<strong>the</strong> stalks dry and dead and rasping and<br />

bare, that God will turn your cornstalks into<br />

<strong>the</strong> skeletons of little children and shake<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir dry bones at you.<br />

poor she began to question <strong>the</strong> effectiveness of charity without legislation. “Charity<br />

is <strong>the</strong> weakest of weapons to combat poverty. It is like pouring water through a sieve.<br />

What <strong>the</strong> poor need is justice and a way to earn a living.” (Barnard)<br />

She returned to Oklahoma Territory to campaign for reforms that she wanted to see<br />

written into <strong>the</strong> constitution when <strong>the</strong> territory became a state. Joseph Thoburn<br />

wrote in 1916 that Barnard was “trusted by <strong>the</strong> two largest classes of voters, <strong>the</strong><br />

farmers and labor union men, and she was <strong>the</strong> favorite speaker on <strong>the</strong> democratic<br />

side. Slender, graceful, petite, with dark hair and skin and flashing eyes, and with a<br />

rapid-fire articulation which was <strong>the</strong> despair of <strong>the</strong> reporters, she painted pictures of<br />

<strong>the</strong> wrongs of childhood, of <strong>the</strong> suffering of minors without <strong>the</strong> protection of law, of<br />

needs of orphans, of <strong>the</strong> inequity of sending juvenile criminals to jails; of <strong>the</strong> cruelties<br />

practiced upon <strong>the</strong> insane and <strong>the</strong> necessity of scientific hospital care; of sweatshops<br />

and overwork and underpay, thrilling her vast audiences with her earnest eloquence.”<br />

During Kate’s two terms of office, she lobbied for <strong>the</strong> Child Labor Law, ensured <strong>the</strong><br />

building of <strong>the</strong> state’s first prison, initiated <strong>the</strong> reform for a Juvenile Court, cleaned up<br />

mental institutions and closed some substandard facilities. Her final crusade came<br />

with her investigation of guardianships of orphaned Indian children. She exposed<br />

influential persons in Oklahoma who were defrauding Indian wards of <strong>the</strong> state<br />

for <strong>the</strong>ir oil monies. Although she recovered over twelve million dollars, she was<br />

ostracized by <strong>the</strong> press who had previously adored her and found her departmental<br />

budget drastically cut. She found herself without <strong>the</strong> power she had grown<br />

accustomed to in her first term. She underestimated <strong>the</strong> power wielded by <strong>the</strong> men<br />

in charge, some of whom she had made her enemies. She was no longer an angel<br />

and became expendable. She decided not to run for a third term.<br />

In failing health, she spent <strong>the</strong> remaining fifteen years of her life in obscurity. She<br />

was found dead in <strong>the</strong> Egbert Hotel in Oklahoma City, penniless, powerless and<br />

unknown. Barnard was buried in an unmarked grave in Fairlawn Cemetery until<br />

<strong>the</strong> early 1980s when a group of anonymous women purchased a headstone with<br />

this inscription: “Intrepid pioneer leader of social ethics in Oklahoma 1879-1930.”<br />

Thoburn’s description of Barnard, “Few women could sway <strong>the</strong> mind of a whole state<br />

for ten years…her work is constructive statecraft and entitles her to a position among<br />

<strong>the</strong> foremost statesmen of <strong>the</strong> age.”<br />

In presenting this remarkable character in <strong>the</strong> centennial year I use Kate’s words as<br />

much as possible. She wrote many letters, reports, articles and memories of her<br />

ideas and history that I have utilized. Barnard was a captivating storyteller and I look<br />

forward to retelling her stories one hundred years later.<br />

Works Cited<br />

Primary sources:<br />

Articles, Reports and letters from Kate Barnard from <strong>the</strong> Julee Short collection at<br />

Oklahoma Dept. of Libraries; Barnard files at <strong>the</strong> Oklahoma History Center; Alice<br />

Robertson collection at University of Tulsa Library.<br />

GOOD HOUSEKEEPING MAGAZINE, 1912. “Through <strong>the</strong> Windows of Destiny. How I<br />

Visualized my Life Work”.<br />

Proceedings of <strong>the</strong> National Conference of Charities and Corrections at <strong>the</strong> Thirty-fifth<br />

Annual Session, Richmond, Va., May 6-13, 1908. “Shaping <strong>the</strong> Destinies of <strong>the</strong><br />

New State”.<br />

First State Conference of Charities, Guthrie, April 29-30, 1908.<br />

Third Annual Conference of State Charities and Corrections, Muskogee, Okla.,<br />

April 29, 1910.<br />

Fourth Annual Report of Commission of Charities and Corrections, Oct. 1,<br />

1911-Oct. 1, 1912.<br />

THE SURVEY MAGAZINE, vol. 23, Oct. 1909-March, 1910. “Human Ideals in<br />

State Government”.<br />

STRUM’S <strong>OKLAHOMA</strong> MAGAZINE, Feb. 1908. “Oklahoma’s Child Labor Laws”.<br />

ST. LOUIS POST-DISPATCH, Feb. 16, 1912. “Grafters After Me, Says Kate Barnard,<br />

Oklahoma’s Guardian Angel Hits Foes Appeals to Legislature for Hearing”.<br />

Letter to Mr. Byron E. White, Supt. Cantonment Indian Agency, Jan. 26, 1911.<br />

Letter to Hon. C. Haskell, Muskogee, Feb. 19, 1912.<br />

Secondary sources:<br />

Books:<br />

Blackburn, Bob, L. HEART OF THE PROMISED LAND: <strong>OKLAHOMA</strong> COUNTY. Woodland<br />

Hills, California: Windsor Publications, 1982.<br />

Burke, Bob and Glenda Carlile. KATE BARNARD. <strong>OKLAHOMA</strong>’S GOOD ANGEL.<br />

Oklahoma Statesmen Series, UCO Press, Edmond, OK, 2001.<br />

Carlile, Glenda. BUCKSKIN, CALICO, AND LACE. Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Hills Publishing, OKC, 1990.<br />

Debo, Angie, AND STILL THE WATERS RUN. New York: Gordian Press, Inc. 1966.<br />

Goble, Danney. PROGRESSIVE <strong>OKLAHOMA</strong>: THE MAKING OF A NEW KIND OF STATE.<br />

Norman, Univ. of Oklahoma Press, 1980.<br />

Musslewhite, Lynn and Suzanne Jones Crawford. ONE WOMAN’S POLITICAL<br />

JOURNEY. Kate Barnard and Social Reform 1875-1930. University of Oklahoma Press,<br />

Norman, 2003.<br />

Reese, Linda Williams. WOMEN OF <strong>OKLAHOMA</strong> 1890-1920. Univ. of Oklahoma Press,<br />

Norman, 1997.<br />

Thoburn, Joseph B. HISTORY OF <strong>OKLAHOMA</strong>. 1916.<br />

Thurman, Melvena, ed. WOMEN IN <strong>OKLAHOMA</strong>: A CENTURY OF CHANGE. Oklahoma<br />

Historical Society, OKC, 1982.<br />

Truman, Margaret. WOMEN OF COURAGE. William Morrow and Company, NY. 1976.<br />

Articles:<br />

DAILY <strong>OKLAHOMA</strong>N, Feb. 23, 1941. “Kate Barnard…Unsung Heroine”.<br />

ORBIT MAGAZINE SECTION, Dec. 10, 1972. Bracken, Nell, “90 Pounds of Human<br />

Dynamite”.<br />

TULSA TRIBUNE, Aug. 26, 1970. “Sooner Lib Leader of Long Ago”.<br />

TULSA TRIBUNE, Oct. 25, 1972. Wittkopp, Pearl, “Tulsan Traces Life of Early Oklahoma<br />

Humanitarian”.<br />

TULSA TRIBUNE, July 21, 1975. March, Ralph, “Our Kate…Heroine of Poor Fought<br />

for Reform”.<br />

JOURNAL OF THE WEST. Hougen, Harvey, “Kate Barnard and <strong>the</strong> Kansas Penitentiary<br />

Scandal 1908-1909”.<br />

I bequeath <strong>the</strong> example of<br />

my public life to <strong>the</strong> youth of<br />

<strong>the</strong> world praying <strong>the</strong>y may<br />

dedicate <strong>the</strong>ir own lives to<br />

securing justice to <strong>the</strong> poor of<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir generation as I did mine.<br />

“Stump Ashby Saves <strong>the</strong> Day”, edited with an Introduction and an Afterward by Julee<br />

Short, JOURNAL OF THE WEST, vol.12, April 1973.<br />

11

Frank Frantz:<br />

Oklahoma Territory’s Rough<br />

Rider Governor By Gary M. Gray<br />

Frank Frantz<br />

He shared <strong>the</strong> “Crowded Hour” with Colonel Theodore Roosevelt…it was Frank Frantz that planted <strong>the</strong> flag of <strong>the</strong> Rough Riders’ Troop A at <strong>the</strong> Spanish blockhouse atop one<br />

of <strong>the</strong> San Juan Hills. That moment of extreme bravery was to lead Frantz to become <strong>the</strong> Osage Indian Agent during <strong>the</strong> tribe’s crucial years of allotment, oil leases, and white<br />

graft, <strong>the</strong>n as <strong>the</strong> last Territorial Governor of Oklahoma.<br />

Frantz was President Roosevelt’s right-hand man as TR sought to bring Indian and Oklahoma Territories in toge<strong>the</strong>r as a state. As such, Frantz managed <strong>the</strong> Oklahoma Enabling<br />

Act, fought battles with <strong>the</strong> railroads and oil industries, called for a Constitutional Convention, helped draft geographical boundaries for convention delegates, and reported<br />

Democratic excesses to President Roosevelt.<br />

Eventually, Frantz fought a losing battle against Democratic nominee Charles Haskell as <strong>the</strong> first Republican nominee for governor of Oklahoma. Bitter, he departed for Colorado<br />

for several years, before returning to Oklahoma to be involved with <strong>the</strong> Cosden Oil Company in Tulsa.<br />

It was one of those magical moments in which time is suspended. Two men said two<br />

sentences and nei<strong>the</strong>r was to be <strong>the</strong> same again.<br />

Colonel Theodore Roosevelt was in <strong>the</strong> middle of his “crowded hour.” As <strong>the</strong> Assistant<br />

Secretary of <strong>the</strong> Navy, he had placed many of <strong>the</strong> events in motion that would lead to<br />

<strong>the</strong> Spanish-American War.<br />

When that war seemed inevitable he sought a way to serve and to demonstrate that<br />

he, <strong>the</strong> sickly boy aristocrat, could be proved courageous. He resigned his prestigious<br />

Washington desk job (Assistant Secretary of <strong>the</strong> Navy) and went about <strong>the</strong> American<br />

territories of Indian, Oklahoma, New Mexico and Arizona recruiting cowboys and farm<br />

boys to become part of a regiment nicknamed <strong>the</strong> “Rough Riders.”<br />

One of his top recruits was Bucky O’Neil of Prescott, Arizona Territory, a man that<br />

knew no fear. O’Neil brought a number of men with him. Frank Frantz was named<br />

his First Lieutenant.<br />

Born in May, 1872, Frantz had been raised in Roanoke, IL and attended Eureka College<br />

(Eureka, IL) for two years before moving with his family to Wellington, KS and <strong>the</strong>n<br />

to Medford with <strong>the</strong> opening of <strong>the</strong> Cherokee Strip run of 1893. By 1898 he was in<br />

<strong>the</strong> mining business in Prescott and was as excited as <strong>the</strong> next young man to feel <strong>the</strong><br />

allure of potential battle.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> midst of <strong>the</strong> first battle for <strong>the</strong> San Juan Hills, Colonel Roosevelt galloped over<br />

to where <strong>the</strong> Arizona Territories’ Troop A had ga<strong>the</strong>red. Not seeing O’Neil, Roosevelt<br />

addressed Lt. Frantz: “Where is your Captain” “He is dead,” he replied. According to<br />

legend Roosevelt <strong>the</strong>n asked, “Where are you going” Frantz excitedly replied, “I’m<br />

going to <strong>the</strong> top of <strong>the</strong> hill!”<br />

Whereupon, with <strong>the</strong> colors of Troop A in his left hand and a sword in his right,<br />

Frantz shouted, “charge” and through a hail of bullets up <strong>the</strong> hill Frantz and Troop<br />

A advanced. It was amidst many a dead and mangled Spanish soldier’s that Frantz<br />

planted <strong>the</strong> Troop A colors at <strong>the</strong> Spanish blockhouse at <strong>the</strong> top to <strong>the</strong> hill. (Anderson,<br />

128; numerous accounts.)<br />

Roosevelt, awed at Frantz’ bravery named him “Captain” and placed his name in for<br />

<strong>the</strong> Silver Star (which he did not receive until 1935).<br />

That “crowded hour” changed both men’s lives forever and made <strong>the</strong>m inextricably<br />

linked. That moment changed <strong>the</strong> history of a state yet to be born.<br />

Later in 1898 Roosevelt was to be elected Governor of New York, in 1900 to <strong>the</strong> Vice<br />

Presidency of <strong>the</strong> United States, and at <strong>the</strong> age of 43 became <strong>the</strong> youngest President<br />

of <strong>the</strong> United States in 1901 when President William McKinley was assassinated.<br />

Meanwhile Frank Frantz moved to Enid, Oklahoma to enter business with his<br />

bro<strong>the</strong>rs. It was <strong>the</strong>re he met and was married in April 1901 to Miss Matilda Evans<br />

at <strong>the</strong> First Presbyterian Church. The local paper, <strong>the</strong> Enid Wave, declared that Miss<br />

Evans “springs from one of <strong>the</strong> best families of Missouri, well bred and well connected in<br />

every particular as <strong>the</strong> life, habits and sociability of herself and bro<strong>the</strong>rs in this city fully<br />

13<br />

testifies. She is an accomplished, educated lady in every sense of <strong>the</strong> word.” Speaking<br />

of her new husband, <strong>the</strong> Wave editorialized “Mrs. Frantz was fortunate indeed in<br />

capturing a husband of <strong>the</strong> highest type of manhood and American chivalry.” They<br />

were to have five children: Frank Jr., Louise, James (who died infancy), Matilda, and<br />

Virginia.<br />

Frantz maintained close contact with Roosevelt. TR was interested in <strong>the</strong> athletic<br />

skills of all <strong>the</strong> Frantz bro<strong>the</strong>rs. TR recruited bro<strong>the</strong>rs Orville (later to be known as<br />

“Home Run Frantz”) and Montgomery (“Preacher Frantz” because he wouldn’t pitch<br />

on Sundays) to attend Harvard University, TR’s alma mater (T. Roosevelt letters in<br />

Frantz Collection.)<br />

In 1902, TR had a chance to help Frank directly by appointing him <strong>the</strong> Postmaster of<br />

Enid. Two years later TR called again, this time asking <strong>the</strong> former Rough Rider to be<br />

<strong>the</strong> Osage Nation Indian agent.<br />

The job was a delicate one. First oil had been discovered on Osage land as early as<br />

1896 and <strong>the</strong> lease would need to be renewed in 1906. TR wanted someone he<br />

trusted to help advance <strong>the</strong> best interests of both <strong>the</strong> full and mixed blood Osage<br />

(See Gregory).<br />

Secondly, TR desired to have a new state during his presidency. He felt <strong>the</strong> most<br />

obvious candidate was a combination of Indian and Oklahoma Territories. But that<br />

meant all of <strong>the</strong> property of <strong>the</strong> Indian tribes needed to be transferred from tribal to<br />

individual ownership through allotment. This needed to be accomplished by 1906<br />

among those of <strong>the</strong> Osage Nation.<br />

“I suppose you are acquainted with my young<br />

friend down <strong>the</strong>re (Enid, OK), Captain Frank<br />

Frantz I first met him at <strong>the</strong> Battle of San<br />

Juan Hill; he was leading his company in that<br />

fight; he seemed but a boy. I rode up to him<br />

and asked: ‘Where is your Captain’ ‘He is<br />

dead,’ he replied. ‘Where are you going’ I<br />

asked. ‘I’m going to <strong>the</strong> top of that hill.’”<br />

- Theodore Roosevelt<br />

Finally, TR was concerned about <strong>the</strong> white graft that was omnipresent among <strong>the</strong><br />

white towns that had sprung up around <strong>the</strong> borders of <strong>the</strong> Osage Nation. Whites<br />

were getting rich by cheating <strong>the</strong> oil rich Osage via illegal documents, gambling,<br />

alcohol, and prostitution. This problem needed resolution. (See Lloyd; Anderson,<br />

page 130.)

Oklahoma, born sixteen years ago<br />

in homeless hardship, cradled in<br />

swaddling clo<strong>the</strong>s of poverty, educated<br />

by experience of much adversity, and<br />

developed through abundant promise,<br />

stands today full grown and asking for<br />

her dower. - Inaugural Address as Territorial<br />

outnumbered Republicans. The constitution was somewhat discriminatory towards<br />

both blacks and Native Americans, which Frantz warned would not be tolerated by<br />

President Roosevelt if adopted. Oklahoma becoming a “Jim Crow” state (separate but<br />

equal) was much debated; but eventually <strong>the</strong>se words were stricken. (Jones 384,<br />

386; Anderson, 140.)<br />

In August 1907 Frantz was nominated by <strong>the</strong> Republican Party to be <strong>the</strong>ir first<br />

nominee for Governor (Jones, p. 388). However, <strong>the</strong> party made <strong>the</strong> mistake of<br />

opposing <strong>the</strong> new constitution. This proved to be an unpopular move, of course,<br />

because constitutional defeat would cause a delay in statehood.<br />

Governor, January 1906.<br />

Frantz no more had begun to grapple with all <strong>the</strong>se issues when in late 1905 he<br />

was summoned to Washington, DC to become <strong>the</strong> last governor of Oklahoma<br />

Territory. It would be a daunting task. Not only had TR decided to combine Indian<br />

and Oklahoma Territory into one state, he wanted that state to be controlled by <strong>the</strong><br />

Republican Party. Frantz was to be TR’s man in Guthrie to bring about statehood and<br />

to eventually lead <strong>the</strong> Republicans into <strong>the</strong> state’s new governor’s chair.<br />

Frantz was inaugurated as Oklahoma Territorial Governor at Guthrie in January 1906<br />

(Anderson, 133) and TR sent <strong>the</strong> Oklahoma Enabling Act through Congress. The<br />

process of statehood was in motion.<br />

Two items, however, in <strong>the</strong> Enabling Act were to work against each o<strong>the</strong>r in<br />

accomplishing TR’s goal of having a Republican State, and his friend Frantz from<br />

becoming <strong>the</strong> first state governor.<br />

The first factor was <strong>the</strong> requirement that <strong>the</strong> Oklahoma Territorial government’s<br />

legislative body would be disbanded, leaving <strong>the</strong> entire administration of Oklahoma<br />

Territory in <strong>the</strong> hands of Frantz (Jones, 379).<br />

Frantz, along with his attorney general W. O. Cromwell, took on <strong>the</strong> enormous<br />

responsibility with vigor probably unrivaled in Oklahoma’s young history. He<br />

challenged <strong>the</strong> railroads, claiming <strong>the</strong>y were charging too much money for <strong>the</strong><br />

merchants of Oklahoma, and won. (Anderson, 135.)<br />

He fought for not only <strong>the</strong> land rights to certain farms set aside for schools but <strong>the</strong><br />

mineral rights as well. “Armies” of deputies fanned throughout Oklahoma Territory<br />

(especially <strong>the</strong> Panhandle) to claim sections of lands in <strong>the</strong> name of <strong>the</strong> Territory.<br />

(Jones, 379-381, Anderson 135)<br />

Monies earned from <strong>the</strong> lease of this land and mineral rights were to be set aside for<br />

education in Oklahoma Territory. Frantz’ efforts formed <strong>the</strong> basis of many billions of<br />

dollars for education over <strong>the</strong> 100 year history of <strong>the</strong> eventual state of Oklahoma.<br />

The second factor emulating from <strong>the</strong> Oklahoma Enabling Act was <strong>the</strong> call for a<br />

constitutional convention, nicknamed <strong>the</strong> “Con Con.” A constitution was necessary for<br />

statehood and Frantz represented <strong>the</strong> Republicans in drawing <strong>the</strong> Oklahoma Territory<br />

boundary lines for convention delegates. The Democrats cried foul, but elected 99<br />

out of 112 delegates between <strong>the</strong> combined two territories and <strong>the</strong> Osage Nation.<br />

(See Murray; Anderson, 139.)<br />

Meanwhile, Charles Haskell was running as <strong>the</strong> Democratic nominee against Frantz.<br />

Frantz issued a proclamation setting <strong>the</strong> date of <strong>the</strong> first election on September 17,<br />

1907, thus complying with <strong>the</strong> requirements of <strong>the</strong> Enabling Act.<br />

Frantz campaigned as best he could under <strong>the</strong> banner of education, and spent most<br />

of his time in Indian Territory where he was not well known.<br />

He urged President Roosevelt to come to Oklahoma to help in <strong>the</strong> campaign, as<br />

he felt <strong>the</strong> Democratic momentum and believed only TR could save Oklahoma for<br />

<strong>the</strong> Republican column. Several times Roosevelt declined Frantz’ urgent requests,<br />

instead sending Secretary of State William Howard Taft to rally <strong>the</strong> wayward troops.<br />

On August 24, Taft criticized <strong>the</strong> constitution and urged <strong>the</strong> election of Frantz. The<br />

Democrats countered with William Jennings Bryan, who drew enormous crowds.<br />

(Jones 390)<br />

Frantz was exonerated (by President Roosevelt) of corruption and drunkenness<br />

during his tenure at <strong>the</strong> Osage Nation Indian Agency, but <strong>the</strong> verdict arrived too<br />

late in <strong>the</strong> gubernatorial campaign. The Republicans were fur<strong>the</strong>r handicapped by<br />

political infighting over <strong>the</strong> constitution.<br />

On election night, September 17th, Charles Haskell and <strong>the</strong> entire Democratic ticket<br />

were elected by pluralities ranging from 23,000 to 30,000. For Governor, Haskell<br />

garnered 134,162 votes to Frantz’ 106,507. Both branches of <strong>the</strong> legislature were<br />

overwhelmingly Democratic. (Jones, 392)<br />

Despite Republican opposition, <strong>the</strong> Constitution was adopted<br />

180,333 to 73,059, and prohibition carried 130,361 to 112,258. Frantz took <strong>the</strong><br />

official canvas to Washington, DC and TR issued his proclamation that Oklahoma<br />

would become a state on November 16.<br />

Totally embittered by <strong>the</strong> acrimony of <strong>the</strong> campaign, Frantz refused to be involved<br />

with Oklahoma’s first gubernatorial inauguration (Murray Vol. II, page 108). He<br />

entered <strong>the</strong> oil business in Denver and eventually returned to Tulsa, OK to conduct<br />

land acquisitions for <strong>the</strong> Cosden Oil Company (See Gregory). He died in 1941.<br />

Had it not been for that brief “crowded hour” in <strong>the</strong> steamy hot hills of Cuba, history<br />

would have been changed dramatically. Had a bullet struck <strong>the</strong> body of Theodore<br />

Roosevelt, <strong>the</strong> land that eventually made up <strong>the</strong> current state of Oklahoma would<br />

have been governmentally and possibly territorially altered. Frank Frantz would have<br />

probably become a successful businessman working alongside his bro<strong>the</strong>rs in Enid, OK.<br />

Had a bullet killed Frank Frantz, a monument may have been erected in his honor. He<br />

survived <strong>the</strong> charge up <strong>the</strong> hill, however, and what resulted was a lasting friendship<br />

with <strong>the</strong> President who wanted his own state…Oklahoma.<br />

Bibliography:<br />

Primary Sources:<br />

Frank Frantz Collection, Oklahoma Historical Society, Oklahoma City, OK.<br />

Frantz, Frank: Report of Agent for Osage Agency. U. S. Office of Indian Affairs, Part I,<br />

Report of <strong>the</strong> Commissioner, Annual Reports of <strong>the</strong> Department of <strong>the</strong> Interior for<br />

<strong>the</strong> Fiscal Year ended June 30, 1905. Government Printing Office, 1906. Pages<br />

United States Department of <strong>the</strong> Interior, “Reports of <strong>the</strong> Governor of Oklahoma<br />

for 1907. Administrative Reports for <strong>the</strong> Year Ending June 30, 1907, (2 vols.,<br />

Washington: Government Printing Office, 1907), Vol. II, pp. 685-687.<br />

Secondary Sources:<br />

By your actions today you have sounded<br />

a warning to <strong>the</strong> ‘little boss’ (Democratic<br />

nominee Charles Haskell) whom <strong>the</strong><br />

Republicans shall banish to a political<br />

island of St. Helena, where he will pace his<br />

measured beat, listening to <strong>the</strong> mourning<br />

waves singing a requiem to <strong>the</strong> dead hopes<br />

of Muskogee’s gifted son. - Acceptance<br />

Address for Republican Nomination for Oklahoma<br />

Governor, August 1907.<br />

Governor Frank Frantz of Oklahoma. Sturm’s Statehood Magazine, February 1906,<br />

Vol. 1, No. 6.<br />

Gregory, Robert. Oil in Oklahoma, Leak Industries, Muskogee, OK, 1976.<br />

Hurst, Irvin. The 46th Star. Western Heritage Books, Inc., Oklahoma City, 1980.<br />

Jones, Stephen. Captain Frank Frantz, The Rough Rider Governor of Oklahoma<br />

Territory, The Chronicles of Oklahoma, Vol. XLIII, No. 4 (Winter 1965-1966), p. 374.<br />

Jones, Stephen. Oklahoma Politics: In State and Nation Volume 1, 1907-1962.<br />

Haymaker Press, Enid, 1974.<br />

Lloyd, Roger Hall, Osage County: A Tribe and American Culture 1600-1934.<br />

iUniverse, New York, 2006, pp 417-454.<br />

Morris, John W., Charles R. Goins, and Edwin C. McReynolds. Historical Atlas of<br />

Oklahoma, Second Edition, University of Oklahoma Press, 1976.<br />

Murray, William H. Memoirs of Governor Murray and True History of Oklahoma.<br />

Meador Publishing Company, Boston, 1945.<br />

The Democrats had become organized through <strong>the</strong> 1905 Sequoyah Convention,<br />

named in honor of <strong>the</strong> great Cherokee leader and teacher. It had been a failed<br />

attempt to make Indian Territory into a separate state, but resulted in organizing <strong>the</strong><br />

Democrats into a formidable political force (see Murray; Hurst pp. 1-15.)<br />

The Constitutional Convention, controlled by chairman Alfalfa Bill Murray, created<br />

a lengthy, radical and populist constitution that was opposed by <strong>the</strong> vastly<br />

Anderson, Ken, “Frank Frantz: Governor of Oklahoma Territory, 1906-1907” in Fischer,<br />

Leroy H. (ed). Oklahoma’s Governors 1890-1907: Territorial Years. Oklahoma<br />

Historical Society, 1975, pp. 128-144.<br />

Baird, W. David, and Danny Goble. The Story of Oklahoma, University of Oklahoma<br />

Press, 1994, pp. 306-312.<br />

Gibson, Arrell Morgan. The History of Oklahoma, University of Oklahoma Press, 1984.<br />

Scales, James R. and Danny Goble. Oklahoma Politics: A History, University of<br />

Oklahoma Press, 1982.<br />

Wilson, Terry P. The Underground Reservation: Osage Oil. University of Nebraska<br />

Press, 1985.<br />

15

“Not Quite Known”:<br />

Lynn Riggs (1899-1954)<br />

By John D. Anderson<br />

Lynn Riggs<br />

Lynn Riggs (1899-1954) is best known as <strong>the</strong> author of <strong>the</strong> 1931 play Green Grow <strong>the</strong> Lilacs, <strong>the</strong> basis for <strong>the</strong><br />

Rodgers and Hammerstein musical Oklahoma! Born near Claremore in Indian Territory of part-Cherokee ancestry,<br />

he wrote 21 full-length plays as well as poetry, screenplays, and fiction.<br />

Playwright Lynn Riggs earned a permanent if obscure place in <strong>the</strong>atre—and<br />

Oklahoma—history by writing Green Grow <strong>the</strong> Lilacs, <strong>the</strong> play that became <strong>the</strong> basis<br />

for <strong>the</strong> classic musical Oklahoma! Yet, Riggs was once ranked with Eugene O’Neill as<br />

<strong>the</strong> equal of any European dramatist. Influential drama critic and editor Barrett Clark<br />

championed Riggs’s work in <strong>the</strong>se terms and published many of his 30 plays, several<br />

of which were produced on Broadway. Ultimately, though, Riggs’s name has become<br />

largely forgotten. His early fame faded in part because he rebelled against <strong>the</strong> narrow<br />

confines of commercial <strong>the</strong>atre to insist on <strong>the</strong> integrity of his tragic, poetic vision of<br />

drama. He succeeded, though, in creating a vivid and significant body of work—true<br />

not only to his personal vision, but faithful also to his regional roots and to <strong>the</strong><br />

turbulent historical period when Indian Territory was transitioning into <strong>the</strong> “brand<br />

new state” of Oklahoma.<br />

Rollie Lynn Riggs was born in 1899 near Claremore in what was <strong>the</strong>n Indian Territory.<br />

His mo<strong>the</strong>r, Rose Ella Duncan Gillis Riggs, was one-eighth Cherokee; she was thus<br />

entitled to an allotment of 160 acres under federal legislation intended to make<br />

Native Americans assimilate by shifting ownership of tribal lands to individuals.<br />

Rose Ella Riggs died in 1901, and her two-year-old son Lynn and his older sister and<br />

bro<strong>the</strong>r inherited shares of <strong>the</strong> allotted land. Six months later, <strong>the</strong>ir fa<strong>the</strong>r, William<br />

Grant Riggs, a rancher, married his second wife, Juliette Scrimsher Chambers, who<br />

was one quarter Cherokee. A harsh stepmo<strong>the</strong>r, Juliette Riggs served as <strong>the</strong> model<br />

for various cruel women in Riggs’s plays, but her malign influence was balanced in<br />

young Lynn’s life by his warm-hearted Aunt Mary Brice and her six daughters. Riggs<br />

was later to immortalize his fa<strong>the</strong>r’s sister as Aunt Eller and one of her daughters as<br />

Laurey in Green Grow <strong>the</strong> Lilacs.<br />

In 1928, shortly before embarking for Europe on a Guggenheim Fellowship—<strong>the</strong><br />

first Oklahoman to be so honored—Riggs reluctantly wrote an autobiographical<br />

sketch for Barrett Clark. He recalled summers riding on horseback and herding<br />

cattle with his fa<strong>the</strong>r and bro<strong>the</strong>r, as well as working in a glass factory in Sapulpa.<br />

For entertainment, <strong>the</strong>re had been “play-parties” and box suppers, like at Old Man<br />

Peck’s in Green Grow <strong>the</strong> Lilacs, and for creative expression, Friday night “speakings”<br />

and singing at <strong>the</strong> local movie house. In 1917, upon graduating from <strong>the</strong> Oklahoma<br />

Military Academy, he rode as a cowpuncher on a cattle train to spend a few months<br />

in Chicago before moving on to New York, where his various jobs included working as<br />

an extra in cowboy movies. Illness brought him back to Oklahoma in 1919; when he<br />

recovered, he became a reporter for <strong>the</strong> Oil and Gas Journal in Tulsa.<br />

During that summer of 1919, he noted tersely in his autobiographical statement for<br />

Clark, “Read all <strong>the</strong> modern poetry, and wrote my first poems. Reams and reams.<br />

Very bad. I went on to Los Angeles, played extra in many movies with <strong>the</strong> older stars,”<br />

such as Rudolph Valentino. “Read proof for <strong>the</strong> Los Angeles Times and nearly ruined<br />

my eyes” (Braunlich 63-64). He was to suffer from eyestrain his whole life and wore<br />

noticeably thick-lensed eyeglasses. Riggs happened to be working late one night in<br />

1920 at <strong>the</strong> Times when angry former employees exploded a bomb, killing several<br />

people. Riggs wrote up <strong>the</strong> story and sold it for $300, enabling him to return home<br />

and start college.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> fall of 1920, Riggs entered <strong>the</strong> University of Oklahoma and threw himself<br />

into musical, dramatic, and literary activities, including publishing poems in H. L.<br />

Mencken’s fashionable magazine Smart Set. When poet Witter Bynner lectured at<br />

<strong>the</strong> university in 1922, he became an important friend and mentor to Riggs. That<br />

summer, Riggs toured widely on <strong>the</strong> Chautauqua circuit as second tenor in <strong>the</strong> Sooner<br />

Quartet, meeting Willa Ca<strong>the</strong>r in Nebraska. In 1923, through Bynner’s influence,<br />

Harriet Monroe devoted an entire issue of Poetry magazine to Riggs’s poetry.<br />

Then, as he wrote in his autobiographical sketch for Clark: “1923—November.<br />

Complete nervous collapse. Various reasons. Went to Santa Fe and worked on a ranch.<br />

Recovered” (Braunlich 64). Santa Fe was where Witter Bynner had settled in 1922.<br />

Bynner biographer James Kraft writes that Riggs became Bynner’s lover for a time<br />

in New Mexico (50), and Riggs biographer Phyllis Cole Braunlich concludes: “Newly<br />

freed by <strong>the</strong> recognition of his own homosexual orientation, [Riggs] never<strong>the</strong>less was<br />

constantly wary of Oklahoma’s judgments, and never quite so full of self-esteem as<br />

[<strong>the</strong> openly homosexual] Bynner was” (13).<br />

Riggs became part of <strong>the</strong> avant-garde arts community in Santa Fe, which included<br />

Ida Rauh Eastman, a founder of <strong>the</strong> Provincetown Players, with which Eugene O’Neill<br />

was associated. In 1925, Eastman produced Riggs’s one-act play Knives from Syria in<br />

Santa Fe. The title refers to a Syrian peddler who sold exotic goods to Oklahoma farm<br />

women—-a figure that recurs in Green Grow <strong>the</strong> Lilacs.<br />

“It must be fairly obvious from reading or seeing<br />

[Green Grow <strong>the</strong> Lilacs] that it might have been<br />

subtitled An Old Song. The intent has been solely<br />

to recapture in a kind of nostalgic glow (but in<br />

dramatic dialogue more than in song) <strong>the</strong> great<br />

range of mood which characterized <strong>the</strong> old folk<br />

songs and ballads I used to hear in my Oklahoma<br />

childhood—<strong>the</strong>ir quaintness, <strong>the</strong>ir sadness, <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

robustness, <strong>the</strong>ir simplicity, <strong>the</strong>ir hearty or bawdy<br />

humors, <strong>the</strong>ir sentimentalities, <strong>the</strong>ir melodrama,<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir touching sweetness.” - Lynn Riggs, “The Author’s<br />

Preface,” Green Grown <strong>the</strong> Lilacs. In The Cherokee Night and<br />

O<strong>the</strong>r Plays. Norman: U of OK P, 2003, p. 4.<br />

Ambitious to succeed as a playwright, Riggs headed to Chicago to teach while writing<br />

<strong>the</strong> violent tragedy Big Lake, which, in 1927, became his first play produced in New<br />

York (with Stella Adler in <strong>the</strong> cast). When he successfully applied for <strong>the</strong> Guggenheim<br />

Fellowship in 1928, he had written five plays and had had three of <strong>the</strong>m published.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> south of France on his fellowship, his thoughts turned to “a more golden day<br />

in Oklahoma” than “<strong>the</strong> parsimonious and desert days that came to birth in my early<br />

childhood,” as he wrote to his former OU professor Walter Campbell (Braunlich 82).<br />

In a report to <strong>the</strong> Guggenheim Foundation, Riggs described <strong>the</strong> play he was writing<br />

17

as his most ambitious, “about a vanished era . . . when people were easier, warmer,<br />

happier in <strong>the</strong> environment <strong>the</strong>y had created. Song flourished. . . . Even <strong>the</strong> speech<br />

of <strong>the</strong> people, backwoods though it was, was rich, flavorous, lustrous, and wise”<br />

(Braunlich 77). This “folk play in Six Scenes, with Songs and Ballads of <strong>the</strong> period”<br />

was Green Grow <strong>the</strong> Lilacs, which was set in Indian Territory in 1900. The Theatre<br />

Guild produced it to mostly favorable reviews on Broadway in 1931 with Franchot<br />

Tone as Curly, Lee Strasberg as <strong>the</strong> peddler, and Tex Ritter singing some of <strong>the</strong><br />

cowboy songs. The production enjoyed a respectable run of 64 performances and<br />

<strong>the</strong>n toured seven cities.<br />

Native American studies scholar Jace Weaver speculates that <strong>the</strong> character Curly<br />

McClain in Green Grow <strong>the</strong> Lilacs is an Indian cowboy. Also, Weaver posits that <strong>the</strong><br />

tension in <strong>the</strong> play between <strong>the</strong> “farmer and <strong>the</strong> cowman” (in Hammerstein’s lyric for<br />

<strong>the</strong> musical version) is based in racial conflict between Amer-European farmers and<br />

Native American cattlemen (Weaver 99). Albert Borowitz, on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand, argues<br />

that Jeeter Fry, <strong>the</strong> villainous handyman in <strong>the</strong> play (renamed Jud Fry by Rodgers<br />

and Hammerstein) is Native American. More and more, in recent years, scholars have<br />

begun to explore <strong>the</strong> Native American presence in Riggs’s work.<br />

While in France, Riggs had also begun writing his most explicit treatment of Native<br />

American <strong>the</strong>mes in an episodic, expressionistic work called The Cherokee Night. The<br />

play is concerned with “that night, that darkness (with whatever flashes of light<br />

allowably splinter through) which has come to <strong>the</strong> Cherokees and <strong>the</strong>ir descendants,”<br />

“The fact is that far from idealizing <strong>the</strong> poetic<br />

quality of that speech [in Green Grow <strong>the</strong> Lilacs], I<br />

haven’t equaled it. I have an aunt . . . who naturally<br />

speaks a much more highly charged poetic<br />

language than I can contrive to write . . . And this<br />

was generally true of <strong>the</strong> Oklahoma folk of thirty<br />

years ago, whom I have written about. These<br />

people talked poetry without any conscious effort<br />

to make beautiful language . . . “<br />

- Lynn Riggs, The New York Evening Post, 24 January 1931<br />

Source: Erhard, Thomas. Lynn Riggs: Southwest Playwright.<br />

Austin, TX: Steck-Vaughn, 1970.<br />

as he explained to Barrett Clark in a letter. “It seems to me <strong>the</strong> best grade of absorbed<br />

Indian might be an intellectual Hamlet, buffeted, harassed, victimized, split,<br />

baffled—with somewhere in him great fire and some granite. And a residual lump of<br />

stranger things than <strong>the</strong> white race may fathom” (Braunlich 80). The Cherokee Night<br />

was Riggs’s favorite among his plays.<br />

Lynn Riggs went on to write a total of 21 full-length plays. Thirteen of <strong>the</strong>m were<br />

published, and almost all were produced. Riggs also wrote and published a number<br />

of one-act plays and two collections of poems, as well as an unfinished novel called<br />

The Affair at Easter (based on <strong>the</strong> murder of one of Riggs’s cousins by <strong>the</strong> man’s wife).<br />

Riggs’s most significant plays, in addition to Green Grow <strong>the</strong> Lilacs and The Cherokee<br />

Night, include Roadside (1930), Russet Mantle (1936), and Out of Dust (1948).<br />

Roadside (known in o<strong>the</strong>r forms as Reckless and Borned in Texas) is a raucous,<br />

high-spirited comedy set in Indian Territory in 1905, adapted as a musical by Harvey<br />

Schmidt and Tom Jones, creators of The Fantasticks. The hero, named Texas, is a<br />

braggart cowboy whose Paul Bunyan-like character contains elements of frontier<br />

humor and tall tales. Russet Mantle, a more satiric romantic comedy, is set in 1930s<br />

Santa Fe and presents a young couple rebelling against conventionality. Out of Dust<br />

is a family drama set on <strong>the</strong> Shawnee Cattle Trail in <strong>the</strong> early 1880s, enacting a tragic<br />

story of sibling rivalry and patricide.<br />

In 1930, while he was waiting for <strong>the</strong> Theatre Guild to produce Green Grow <strong>the</strong> Lilacs,<br />

Riggs went to California to write screenplays for six weeks. He continued throughout<br />

<strong>the</strong> 1930s to commute between Santa Fe and New York to Hollywood, earning screen<br />

credits on films such as Stingaree (1934) with Irene Dunne, The Garden of Allah (1936)<br />

with Marlene Dietrich and Charles Boyer, and The Plainsman (1936) with Gary Cooper<br />

and Jean Arthur. In Hollywood, Riggs became close friends with such stars as Bette<br />

Davis and Joan Crawford. In 1934, Crawford gave Riggs a Scottie puppy he named The<br />

Baron, and Riggs was present at Crawford’s wedding in 1935 to Franchot Tone, <strong>the</strong><br />

original Curly in Green Grow <strong>the</strong> Lilacs.<br />

Frustrated with <strong>the</strong> compromises that commercial <strong>the</strong>atre demanded, Riggs<br />

turned more and more to regional <strong>the</strong>atres to produce his plays. He aspired—<br />

unsuccessfully—to create a visionary art <strong>the</strong>atre called <strong>the</strong> Vine in collaboration<br />

with directors Mary Hunter and Andrius Jilinsky, playwright Paul Green, and Enrique<br />

Gasque-Molina (who adopted <strong>the</strong> pseudonym Ramon Naya), a Mexican artist and<br />