IT'S ALL MAKE BELIEVE: - OKLAHOMA chautauqua

IT'S ALL MAKE BELIEVE: - OKLAHOMA chautauqua

IT'S ALL MAKE BELIEVE: - OKLAHOMA chautauqua

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

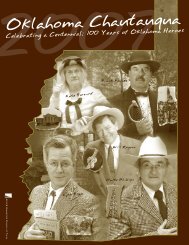

The Arts & Humanities Council of Tulsa in association with the Oklahoma Humanities Council presents<br />

It’s all make belIeve:

Good evening, and welcome to the 2011 Oklahoma Chautauqua, It’s All Make Believe: Hollywood’s Golden Age. The Arts &<br />

Humanities Council of Tulsa in association with the Oklahoma Humanities Council is pleased to bring you the finest in living<br />

history re-enactors, providing life-long learning to the residents of three communities in Oklahoma – Enid, Lawton, and Tulsa!<br />

This year, we celebrate two milestone anniversaries: The 20th Anniversary of Chautauqua, and the 50th Anniversary of the Arts<br />

& Humanities Council of Tulsa! Some of you Chautauqua veterans have been with us for all twenty years – and we thank you!<br />

We are especially pleased to be able to provide this program free of charge, thanks to major support from the Oklahoma<br />

Humanities Council and our presenting sponsor, The Mervin Bovaird Foundation. We also wish to thank the additional sponsors<br />

listed on the back of this program.<br />

Special thanks to OSU-Tulsa and its president, Howard Barnett, for providing this wonderful event space. And to Williams for<br />

printing this year’s Brochure.<br />

I would also like to acknowledge our Chautauqua Committee co-chaired by Kim Smith and Ron Nick, as well as our Chautauqua<br />

Coordinator, Angela Fox, who, together, work diligently to make this the best living history program in the State of Oklahoma!<br />

We are dedicating this year’s Oklahoma Chautauqua in memory of Dr. Gary Gray, publisher,<br />

historian, actor, and author, renowned for his historically accurate portrayals of nine of America’s<br />

greatest citizens. Gary last appeared on our stage in 2008, with a brilliant portrayal of Senator<br />

Barry Goldwater. Often referred to as “Mr. President” because of his portrayals of George<br />

Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Gary was an excellent scholar<br />

and a good friend to the Oklahoma Chautauqua.We will miss him greatly!<br />

We know that you will enjoy your time with us this year as we celebrate the ups and downs<br />

and the ins and outs of Hollywood in the 1920s and 1930s. Thank you for your continued<br />

patronage. We look forward to seeing you again next year!<br />

Warm regards,<br />

Ken Busby<br />

Executive Director & CEO<br />

Arts & Humanities Council of Tulsa<br />

Dr. Gary Gray as<br />

Senator Barry Goldwater

sponsors<br />

In its 20th continuous year, the Oklahoma Chautauqua is a program<br />

of the Arts & Humanities Council of Tulsa. Major funding is provided<br />

in part by a grant from the Oklahoma Humanities Council. Additional<br />

support for this program is provided by the following: Oklahoma State<br />

University – Tulsa, The Mervin Bovaird Foundation, The Judith & Jean<br />

Pape Adams Charitable Foundation, Williams, and the Downtown<br />

Double Tree Hotel.<br />

MeMorials, honorariuMs,<br />

and other endowMent<br />

contributions May<br />

be Made payable to:<br />

The Arts & Humanities<br />

Council of Tulsa<br />

2210 South Main Street<br />

Tulsa, Oklahoma 74114<br />

The 2011 Oklahoma Chautauqua is funded in part by the Oklahoma Humanities Council<br />

(OHC) and the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). Any views, findings,<br />

conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication do not necessarily<br />

represent those of OHC, NEH or the Arts & Humanities Council of Tulsa.<br />

<strong>chautauqua</strong><br />

coMMittee<br />

MeMbers 2010-2011<br />

Ron Nick, co-chair<br />

Kim Smith, co-chair<br />

Vicki Adams<br />

Victoria Bartlett<br />

Harry Dandelles<br />

Julie Evans<br />

Nancy Feldman<br />

Gini Fox<br />

Mary Anne Lewis<br />

Patty McNeer<br />

Marilyn Mitchell<br />

Linda Morrissey<br />

Sandy Moore<br />

David Pettyjohn<br />

Paula Settoon<br />

Edith Wilson<br />

Martin Wing<br />

Ken Busby, Executive Director, AHCT<br />

Angela Fox, Oklahoma Chautauqua Coordinator<br />

_____________________________<br />

Layout/Design by Judy Webb<br />

Photographs by John Fancher

tuesday, June 7<br />

D.W. Griffith portrayed by Dr. Doug Mishler Page 4<br />

wednesday, June 8<br />

Louella Parsons portrayed by Karen Vuranch Page 8<br />

thursday, June 9<br />

Paul Robeson portrayed by Joseph Bundy Page 12<br />

Friday, June 10<br />

W.C. Fields portrayed by Hank Finken Page 16<br />

saturday, June 11<br />

Walt Disney portrayed by Dr. William Worley Page 20

d.w. griffith<br />

portrayed by<br />

dr. doug Mishler<br />

4

d. w. griFFith:<br />

the Man who invented cineMa<br />

by doug a. Mishler<br />

David Wark Griffith is truly one of the giants of American Film.<br />

Between 1908 and 1946 he wrote 208 films, acted in 43, produced<br />

63, and directed a monumental 535. His career stretched from<br />

the creation of eight minute narrative film thru the development<br />

of sound films and cinematic features that ran to three hours. The<br />

techniques he created and refined helped transform the shoddy<br />

little peep-show business into the world’s most significant art<br />

form. While his career is the history of American cinema, his<br />

life demonstrates the early 20th century’s powerful contending<br />

cultural forces of tradition and modernism.<br />

Griffith’s Hollywood future would have been<br />

incomprehensible to him when he was born in<br />

1875 in Oldham County, Kentucky. His father<br />

was a nere-do-well who in 1850 went to the<br />

California goldfields and made a fortune<br />

of $24,000 in one year only to gamble it<br />

away the next year. At age 42 his father<br />

joined the Confederacy, fought with<br />

“Fighting Joe Wheeler,” was wounded<br />

at Shiloh, and escorted Jefferson Davis<br />

in his flight after Appomattox. Even<br />

though he was as aloof and distant<br />

from his children as he was his wife (DW<br />

could never recall seeing his parents<br />

embrace or kiss), his father was almost<br />

a mythical figure to young David. He read<br />

Shakespeare aloud and told magical stories<br />

of romance, chivalry, heroism, and the glory of<br />

southern Victorian culture. These stories shaped<br />

David’s life and film career.<br />

Young David had little money and received little education but<br />

loved to read and he quickly fell in love with the imaginary world<br />

of theater. His first role at age 16 was as the dunce in the corner of<br />

a schoolroom. Twenty year old “Lawrence” Griffith left Kentucky<br />

with a travelling theatrical group and by age 24 was living<br />

in New York flophouses filled with rats and other out of work<br />

actors. In 1904 he toured across the nation playing a mediocre<br />

and overdone Abe Lincoln, yet met Linda Arvidison who became<br />

his wife. In 1907, at age 32 and desperate for money, the not so<br />

young Lawrence Griffith held his nose and took a part in his first<br />

film, the overheated melodrama Rescued from the Eagles Nest.<br />

While Lawrence felt films were trash and not art like theater,<br />

his experience being directed by the inventive Edwin Porter<br />

piqued his interest in not just a steady paycheck but<br />

in telling stories. In 1908 he became Biograph’s<br />

second director and released his first film The<br />

Adventures of Dollie. His career was launched<br />

and for $50 he churned out 2 films a week<br />

for the next few years. With each new<br />

film he became more insightful in telling<br />

stories of ever increasing complexity<br />

and emotion.<br />

Now calling himself “DW,” Griffith was<br />

a powerful presence from the start.<br />

He minutely directed his actors and<br />

demanded perfection, yet he quickly<br />

created a close cadre of actors who<br />

worshipped him. He was always enigmatic;<br />

a gracious southern gentleman mostly, but<br />

a man tough enough to punch out extras and<br />

even stars who challenged him directly. He famously<br />

worked himself and everyone else 16 hours a day, 6 days a<br />

week, and often was so wrapped up he forgot everyone’s lunch<br />

and dinner. Lillian Gish, Mae Marsh, Mary Pickford, John Ford,<br />

W.C. Fields, Raoul Walsh, Walter Huston, and Mac Sennett all got<br />

their start with DW.<br />

D.W. Griffith, 1875-1948: Griffith was born in rural Kentucky to Jacob “Roaring Jake” Griffith, a Confederate Army colonel and Civil<br />

War hero. He grew up with his father’s romantic war stories and melodramatic nineteenth century literature that were to eventually<br />

mold his black-and-white view of human existence and history. In 1897, Griffith set out to pursue a career both acting and writing<br />

for the theater but for the most part was unsuccessful. Reluctantly, he agreed to act in the new motion picture medium for Edwin<br />

S. Porter at the Edison Company. Griffith was eventually offered a job at the financially struggling American Mutoscope & Biograph<br />

where he directed over 450 short films, experimenting with the story-telling techniques he would later perfect in his epic The Birth of<br />

a Nation (1915). Griffith and his personal cinematographer G.W. Bitzer collaborated to create and perfect such cinematic devices as<br />

the flashback, the iris shot, the mask, and crosscutting. In the years following Birth, Griffith never again saw the same monumental<br />

success, and, in 1931, his increasing failures forced his retirement. Though hailed for his vision in narrative film-making, he was similarly<br />

criticized for his blatant racism. Griffith died in Los Angeles in 1948, one of the most dichotomous figures in film history.

With his love of realism and innovation, DW’s actors and<br />

cameramen were imperiled at almost every turn. He pushed<br />

the technical envelope being the first to bury a camera (and<br />

cameraman), first to film from a moving car, first to hang a<br />

camera (and cameraman) off a cliff and even drop buildings<br />

around the camera – (and cameraman). His actors had live bullets<br />

fired at them and some were nearly blown apart. He once had<br />

his favorite actor Lillian Gish run across a half-frozen river--she<br />

nearly both drowned and froze to death shooting one scene for<br />

10 hours in a blizzard. Yet his cast and crew respected his genius<br />

as he invented or perfected (not always sure which) close-ups,<br />

fades, cross cuts, parallel shots, insert shots, split screen, nonlinear<br />

story lines, mid-range shots, iris dissolves, as well as soft<br />

focus (originally done with a coffee can taped around the lens).<br />

His films grew increasingly complex and he radically demanded<br />

that they be shot on location and out of doors. In 1910<br />

he took the first film crew to Los Angeles for the<br />

summer and gave birth to Hollywood. He<br />

was credited with producing the first<br />

major western film in 1910 and the<br />

first gangster film in 1912. With<br />

Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks<br />

and Charlie Chaplin he created<br />

United Artists studios. Yet<br />

his greatest successes were<br />

two towering films still<br />

considered all time classics.<br />

In 1914 he helmed the first<br />

feature length film – the<br />

first blockbuster – a film still<br />

considered the benchmark of<br />

early cinema and arguably the<br />

most infamous film of all time,<br />

The Birth of a Nation. BON was so<br />

successful Lillian Gish noted, “We<br />

lost track of all the money it made.”<br />

Yet BON also fostered a firestorm of<br />

criticism about Griffith’s “racism.” Stung,<br />

DW responded to his critics with yet another<br />

monumental film, Intolerance [1917], the first<br />

film to have four stories run concurrently.<br />

By 1920, DW was widely hailed as “the” cinematic genius<br />

and praised as the man who made film into art. Yet almost<br />

simultaneously Griffith’s art and life started to come unraveled.<br />

His bitter separation from his wife was only one of the struggles<br />

he faced. He was a terrible businessman, and though he made<br />

a great deal of money (he made over $700,000 from BON in<br />

1915 alone) he also spent a great deal on his films and a failed<br />

production company. Though he never spent money on himself<br />

save for hats to protect him from the sun (he believed the sun<br />

would make him go bald), his brother and others squandered his<br />

money while he lived in hotels and ate at lunch-counters—when<br />

he remembered to eat that is.<br />

Yet the worst challenge facing DW was that despite some truly<br />

6

great films after 1917 such<br />

as the racially sensitive<br />

Broken Blossoms [1919] and<br />

Orphans of the Storm [1920]<br />

his stories were increasingly<br />

seen as old fashioned. His<br />

father’s Victorian ideals never<br />

went away, so while his genius<br />

was in modern realistic films, he<br />

loved to do more syrupy Victorian<br />

melodramas. By the 1920s, his genius<br />

was clearly trapped in the past and he could<br />

not adapt. He invented no new techniques<br />

and the hip modern world of flappers and liberal<br />

values was an anathema to him. He made one decent sound film<br />

Abraham Lincoln (1930) but The Struggle (1931) about alcoholism<br />

was widely panned and avoided. By 1932 few wished to hear his<br />

archaic moral lessons and his career was over.<br />

The rejection of his work drove DW to the bottle and he would<br />

end his life a lonely alcoholic living in a hotel in Los Angeles. He<br />

died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1948 at age 73, as ignored in his<br />

last years as he was celebrated in his golden years.<br />

Charlie Chaplin, John Ford, Alfred Hitchcock, and Orson Welles<br />

all spoke of Griffith as “The teacher of us all.” Due to his artistic<br />

achievements, from 1953 to 1998 the Director’s Guild of America<br />

named their highest award after Griffith. Yet as was typical of<br />

Griffith’s life and legacy, due to the continuing furor over BON,<br />

in 1999 DW’s name was dropped from the title of what became<br />

known as a “Lifetime Achievement award.”<br />

D.W. Griffith’s life followed a remarkable path from the son of<br />

an ex-confederate Colonel in small town Kentucky, to the artistic<br />

giant of the American cultural industry.<br />

works cited<br />

D.W. Griffith’s the Birth of a Nation: A History of the Most Controversial<br />

Motion Picture of All Time, Melvyn Stokes, Oxford University Press, 2008<br />

D.W. Griffith: An American Life, Richard Schikel, Limelight Editions 2004<br />

Stagestruck Filmmaker: D. W. Griffith and the American Theatre (Studies<br />

Theatre Hist & Culture), David Mayer, University Of Iowa Press; 2009<br />

D.W. Griffith: His Life and Work, Robert Henderson, Oxford University<br />

Press, 1972<br />

Adventures with D. W. Griffith, Karl Brown, Farrar, Strauss and Giroux,<br />

New York, 1973<br />

Lillian Gish: The Movies, Mr. Griffith, and Me, Lillian Gish Englewood<br />

Cliffs, N. J. : Prentice-Hall, 1969<br />

about dr. doug Mishler: In the last fifteen years Doug has brought “history to life” in well over one thousand presentations. In<br />

addition to his latest character D. W. Griffith and his first P. T. Barnum, Doug has presented Theodore Roosevelt, Ernie Pyle, General<br />

Stonewall Jackson and 11 other historical figures. The voices in his head keep him busy but when he is not on the road with the boys<br />

he finds time to direct and act in theatrical plays, as well as teaching American history at the University of Nevada. He has garnered<br />

a national reputation as one of the finest first-person performers. Like his idol Theodore, Doug believes there is still plenty of time to<br />

grow up and get a “real job”- but later!

louella parsons<br />

portrayed by<br />

karen vuranch<br />

8

louella parsons:<br />

First lady oF hollywood<br />

by karen vuranch<br />

Someone once said of Louella Parsons, “Maybe she’s just a nice<br />

lady that got caught up in a dirty business.” “Yes,” came the reply,<br />

“except she invented the dirty business.” This dirty business is<br />

the Hollywood gossip columnist and Louella was the first. At the<br />

height of her career, her gossip column was syndicated in 1,200<br />

newspapers worldwide, with 40 million readers daily. But, surely,<br />

gossip has been a part of social conscious as long as there has been<br />

society. Louella herself often said, “How would we know about<br />

Antony and Cleopatra if historians hadn’t gossiped<br />

about them?” History books are chock full of<br />

court intrigues and clandestine affairs, and<br />

you can be sure these incidents were<br />

the talk of the courts. So what exactly<br />

is Louella Parson’s contribution to<br />

the world of gossip?<br />

Louella’s future in journalism<br />

was evident even in childhood.<br />

In her autobiography, she<br />

tells of the first story she<br />

published at the age of ten.<br />

But, more interesting was<br />

the way it came to print.<br />

The local newspaper editor<br />

said it was “nice” and maybe<br />

he would publish someday,<br />

suggesting that after she was<br />

dead, the story would live on. A<br />

few days later she had an accident<br />

climbing a hayloft. When the editor<br />

came to visit her, she staged a “deathbed<br />

scene that would do credit to Bette Davis.”<br />

(The Gay Illiterate, p.8). Louella goes on to say,<br />

“Later I was to know the thrill of a scoop …. But, never<br />

have I experienced a deeper, more abiding glow of satisfaction<br />

than in my first by-line for The Flower Girl of New York.”<br />

As a young woman, Louella worked for the newspaper in her<br />

hometown of Dixon, Illinois, The Dixon Star. She even covered<br />

a murder trial, a story that the Chicago papers picked up and ran<br />

with her by-line. According to her biographer, Samantha Barbas,<br />

Louella wanted a career in journalism. But in the early 1900s, it<br />

was nearly impossible for women. Barbas states that in 1900,<br />

only seven percent of journalists were women and, with the<br />

exception of women like Nellie Bly, most did not make it past the<br />

women’s pages.<br />

But, Louella’s other interest allowed her to leapfrog into<br />

journalism. Movies were a fledgling industry in the early 20th<br />

century and Louella was mesmerized by early “flicker” pictures.<br />

She moved to Chicago in 1910, after a disastrous first marriage,<br />

and began writing scripts and submitting them. One of those<br />

scripts, based on that murder trial she covered as a<br />

young woman, caught the attention of Essanay,<br />

one of the early studios. Not only did they<br />

buy the script, they offered Louella a job<br />

as a script writer.<br />

Although film evolved into a major<br />

industry, the early Nickelodeons<br />

initially appealed to the<br />

working class. It was not a<br />

business that was particularly<br />

important by social standards<br />

-- immigrants and women had<br />

no trouble finding work in<br />

the film business. Of course,<br />

many of those immigrants<br />

go on to fabulous studio<br />

careers with names like Zuckor,<br />

Selznick and Mayer. But in the<br />

early years, according the National<br />

Women’s History Museum, there<br />

were many opportunities for women,<br />

both on screen and off. Many studios had<br />

female directors and writers. Louella worked<br />

for Essanay as both script writer and purchasing<br />

scripts that were submitted. For three years she lived and<br />

breathed the movies, associating with many of the great stars of<br />

the future including Charlie Chaplin and Gloria Swanson.<br />

But, infants soon learn to walk and the movie industry toddled<br />

towards its future success. According to Louella, Essanay was shortsighted,<br />

thinking that the industry would not change and persisted<br />

in making short, one-reel films, even though other studios moved<br />

to longer and more complicated scripts. Finally, Essanay was<br />

headed for bankruptcy and Louella needed another job.<br />

LoueLLa Parsons, 1881-1972: Smarmy-tongued Hollywood gossip columnist of the 40s and 50s who was often in imbroglios with<br />

not only her subjects but her professional rivals as well.

Her experience as a script writer landed her back in the field of<br />

journalism, working for The Chicago Herald, writing a column,<br />

How to Write Photo Plays. Eventually this column was so<br />

successful that she also published a book on how to write scripts<br />

for the movies. Louella is self-deprecating about her book in her<br />

autobiography, but she was proud that it was the first of its kind<br />

published and even prouder that it was used for many years as a<br />

textbook by the University of Chicago.<br />

It was while she was working at The Herald that she came up with<br />

an idea – why not write a column about movie stars? The public<br />

seemed fascinated with the burgeoning industry and they were<br />

especially interested in what the stars were like off-screen. Thus,<br />

the first ever movie gossip column was born. Furthermore, she<br />

pioneered a new journalistic style – chatty and informal – just<br />

a respectable, middle-class mother, talking as “one of us girls.”<br />

(Barbas,48.)<br />

The rest, as they say, is history. After working for the Chicago<br />

paper, she moved to New York to work for The Morning Telegraph<br />

and then a Hearst newspaper, The American. Her association<br />

with newspaper mogul William Randolph Hearst spanned several<br />

decades and her loyalty to The Chief was well-known. But her job<br />

was always the same – to hobnob with the stars, writing about<br />

the movies and stars of the day.<br />

Louella has been accused many times of not being<br />

a good writer and she, herself, made fun of<br />

the fact that she dangled her participles and<br />

split her infinitives. But for the 51 years she<br />

was in the business, she was a good reporter.<br />

She was a passionate supporter of both the<br />

10<br />

movie industry and the field of journalism. In 1922, she was one<br />

of the founding members of the prestigious New York Newspaper<br />

Women’s club and went on to serve as President (Barbas, 68). This<br />

organization, still in existence, was created with a feminist aim<br />

and pressured newspapers to hire more women in areas other<br />

than the society pages. In fact, Louella participated in several<br />

organizations that promoted equality for women and promoted<br />

women’s issues throughout her life.<br />

But, how does Louella’s journalistic career differ from the<br />

maddening paparazzi of today? Well, for one thing, the studios<br />

and the stars gladly provided Louella with the news that was<br />

the fodder of her column. A mention in her column or on her<br />

radio show was publicity gold. In fact, she was the original “spin<br />

doctor,” often reporting facts in such a way that the star retained<br />

credibility and empathy from their fans. It is not until the rise of<br />

tabloid journalism that gossip news changed from the doting and<br />

affectionate style of Louella to the aggressive reporting of Rupert<br />

Murdoch or Geraldo Rivera, according to Jeannette Walls in her<br />

recent book, Dish.<br />

The other aspect that makes Louella different from contemporary<br />

gossip reporters is that she was fiercely proud of Hollywood<br />

and its people and hotly defended the movies. She opposed<br />

censorship, speaking out against any limitations; she was filled<br />

with patriotic pride of the role of Hollywood in World War<br />

II and, as she would say, got “fighting mad” when<br />

anyone accused Hollywood of not advancing the<br />

war effort. In general, she was protective of the<br />

movie industry and as staunch an advocate of<br />

anything to do with the movies as a mother<br />

with a large brood of children.<br />

It is true that Louella Parsons wielded<br />

extraordinary power in Hollywood -- she had the<br />

clout to “make ‘em or break ‘em.” Those who did<br />

not acquiesce to her and “share” their news often<br />

found their career floundering. In fact, by the late<br />

1940s, she was so powerful that the studios established<br />

another gossip columnist, Hedda Hopper, to compete with<br />

Louella. The feud between these two is legendary. But, despite<br />

the competition, Louella retained her power in Hollywood.<br />

But, this power was significantly kinder and gentler than those<br />

who cover Tinsel Town today. The business that Louella Parsons<br />

pioneered has gone on to receive a great deal of criticism from<br />

both the stars they stalk and the readers who protest. Even though<br />

it was proven that the auto accident that killed Princess Di was<br />

not caused by paparazzi, but by a drunk driver, most persist in<br />

blaming the media (Walls, 328). The business created by Louella<br />

has changed today and the outcry against the excessive prying<br />

of contemporary journalists continues. Louella might not even<br />

approve of how the business had changed. After all, this was her<br />

town and her business. And, she never let you forget it.

gossip about the gossip writer<br />

Louella just might be the proverbial “pot that calls the kettle<br />

black.” Her own love life would have raised a few eyebrows but<br />

she kept much of it a secret. She married young to the debonair<br />

John Parsons. Two years later he left her for his secretary,<br />

leaving her with their infant daughter, and Louella<br />

moved to Chicago. In 1918, he enlisted but never<br />

saw any WWI action, dying of the flu before<br />

reaching Europe (Barbas, p. 33). Louella<br />

claimed that she “arrived in Chicago as<br />

a young war widow” even though she<br />

went there in 1910, eight years before<br />

John died, and their divorce was final<br />

in 1911. In her autobiography, Louella<br />

waxed poetic about the romantic<br />

letters of reconciliation he sent from<br />

a battlefield hospital. Since he never<br />

made it to the battlefield, one can only<br />

assume that these letters were a public<br />

“spin” on a personal tragedy.<br />

At least John Parsons gets mentioned. Her<br />

second husband, Jack McCaffrey, is glided over<br />

and forgotten. McCaffrey was a steamboat captain<br />

who piloted ships on the Mississippi (Barbas, 41). He was<br />

good-natured and had an excellent reputation as a captain. But<br />

the marriage was doomed. Although they genuinely loved each<br />

other, they were very different. He was quiet and unambitious<br />

and had little interest in the movies, thinking they were frivolous<br />

(Barbas, 43). The movies were not only Louella’s livelihood, but<br />

something she found endlessly fascinating. They drifted apart<br />

after several years of marriage. But it took almost a decade to<br />

pass before Louella finally filed for divorce.<br />

Louella’s next romance continued her unlucky streak in love. After<br />

moving to New York, Louella fell in love with a charming Irishman and<br />

powerful labor leader, Peter Brady. But, Brady was already married<br />

and, as a Catholic, unable to divorce. She acknowledges their nineyear<br />

affair in her autobiography, not giving his name. Brady would<br />

die tragically in a plane crash, a year after their affair was over.<br />

Love eventually smiled upon Louella when she met Dr. Harry Martin.<br />

In fact, she was on her way East by train to meet Peter Brady when<br />

she met Harry. Louella was immediately captivated by his warmth<br />

and humor and it appears he was equally taken with Louella. At<br />

the end of the trip, Martin showed her a telegram he was going to<br />

send to a friend. The telegram said that Martin intended to marry<br />

her. 18 months later, they were married.<br />

Harry was the love of Louella’s life, although<br />

their marriage could be tempestuous. And<br />

both would imbibe a little too much on<br />

occasion. Once, at a party where Harry<br />

had passed out from drinking too much,<br />

Louella said, “Don’t wake him. He has<br />

to operate in the morning.” On another<br />

occasion, according to her biographer,<br />

Harry had too much to drink and dove<br />

head first into a swimming pool. He<br />

actually broke his neck, but using his<br />

medical knowledge, he held his head in<br />

place until he made it to a hospital.<br />

Louella Parsons was known as the most<br />

powerful woman in Hollywood. Her column could<br />

make or break the career of a star. But her gossip<br />

expertise made her uncomfortably aware of how personal<br />

stories could spread and she made sure that what the public knew<br />

– was what she wanted them to know.<br />

works cited<br />

Barbas, Samantha. The First Lady of Hollywood: A Biography of Louella<br />

Parsons. University of California Press: Berkeley, 2006.<br />

Eel, George. Hedda and Louella, Warner: NY, 1973.<br />

National Women’s History Museum, Internet article: Women in Early Film.<br />

Parsons, Louella O. Tell It To Louella. G.P. Putnam’s Sons:NY, 1961.<br />

Parsons, Louella O. The Gay Illiterate. Garden City Publishing Co.: NY, 1944.<br />

Walls, Jeanette. Dish: How Gossip Became the News and the News<br />

Became Just Another Show. HarperCollins: NY, 2001.<br />

Willis, Gary. Rome’s Gossip Columnist: When the First Century Poet<br />

Martial Turned His Stylus on You, You Got the Point. The American<br />

Scholar, July 16, 2010<br />

about karen vuranch: Karen Vuranch is a storyteller, actress, historian and writer. Using solid historical research, she creates<br />

characters that bring history to life. She has toured internationally with Coal Camp Memories. Based on oral history, it chronicles a woman’s<br />

experience in the Appalachian coal fields. Homefront is a play based on oral history she collected about women in World War II. Karen also<br />

recreates historical figures: author Pearl Buck; labor organizer Mother Jones; humanitarian Clara Barton, and Indian captive Mary Draper<br />

Ingles. Grace O’Malley, a 16th century Irish pirate and Wild West outlaw Belle Starr, the First Lady of Food, Julia Child. Karen has served as<br />

an Adjunct Faculty at Concord University for the past 18 years, teaching Theatre, Speech and Appalachian Studies.

paul robeson<br />

portrayed by<br />

Joseph bundy<br />

12

paul robeson and the<br />

golden age oF hollywood:<br />

in vogue and taboo<br />

by Joseph bundy<br />

The year 1898 was a precarious time for a little African-American<br />

boy christened Paul Leroy Robeson to be born, was it a time of<br />

promise? As a mother and father looked down on the crib of their<br />

new born infant they may have felt that for their new baby the<br />

lyrics from a song by James Weldon Johnson summed up prospects<br />

of the baby’s future: “Stony the road we trod, bitter the chastening<br />

rod felt in the days when hopes unborn had died.” In<br />

1860 William Drew Robeson escaped slavery in<br />

North Carolina to freedom in Chester County,<br />

Pennsylvania. His successful flight liberated<br />

him from human bondage and gave him<br />

access to educational opportunities<br />

that had previously been denied. In<br />

North Carolina the laws forbade<br />

him from getting an education. But<br />

in Chester County, Pennsylvania<br />

he was able to attend Lincoln<br />

University, a school established<br />

for African American males<br />

by the Presbyterian Church.<br />

Following the Union victory in the<br />

Civil War and the constitutional<br />

amendments that granted African<br />

Americans equal protection under<br />

law and citizenship it seemed that<br />

the future for William Drew Robeson<br />

and his children would be brighter.<br />

However, by the time his youngest son,<br />

Paul, was born the winds of justice and equal<br />

opportunity had shifted away. Two years earlier the United<br />

States Supreme Court affirmed the legality of racial segregation<br />

and a caste system was in place that treated African Americans<br />

as second class citizens. But Paul possessed the intelligence,<br />

physique, talent, an ambition that enabled him to soar beyond<br />

the status quo and achieve his lofty goals.<br />

As a young child he possessed a personality that endeared him<br />

to people.<br />

His mother died in a tragic accident when Paul was five years old<br />

both the black and white community treated the motherless child<br />

with benevolent care. In 1907 the family moved to Westfield,<br />

New Jersey. Robeson said after the family moved he<br />

still grieved for his mother; “I must have felt the<br />

sorrows of a motherless child but what I<br />

remember most from my youngest days<br />

was an abiding sense of comfort and<br />

security.” Yet, even at that young age,<br />

Paul believed “he was aware of<br />

that subtle difference between my<br />

complete belonging to the Negro<br />

community and my qualified<br />

acceptance (however admiring)<br />

by the white community.” The<br />

child’s charm made him in vogue<br />

to the dominant community but<br />

his race made him taboo.<br />

When the family moved to<br />

Somerville, New Jersey, Paul<br />

attended the all black (Colored)<br />

Jamison school where he excelled.<br />

In 1912 he entered Somerville High<br />

School. The student body had two hundred<br />

students but only a dozen black children.<br />

He and Winston Douglass were the only black<br />

students in his class of forty. But being a minority did not<br />

hinder him. He was the best scholar in his class and one of the<br />

school’s most popular students. He was the star athlete on the<br />

football, basketball and baseball team. And he was a better that<br />

average tennis player. His beautiful bass/baritone voice anchored<br />

the school choir and he had the speaking voice of an outstanding<br />

PauL robeson, 1898-1976: Paul Robeson was a preacher’s child and son of a former slave. He was an African American born in<br />

Princeton, New Jersey in 1898. This was a time when racial prejudice permeated the entire nation. But he was able to overcome<br />

whatever obstacles he confronted and he became star athlete, a noted concert singer, and an internationally renowned stage and film<br />

actor. As a stage actor he was a favorite of America’s greatest playwright Eugene O’Neill and won international acclaim for his portrayal<br />

of Shakespeare‘s “Othello.” As a film actor his credits include “Sander’s of The River,” “The Emperor Jones” and The Hollywood classic,<br />

“Showboat.” Although he overcame many obstacles, they did leave some psychological scars that pushed him to the political left.<br />

Because he embraced communism and the politics of the Soviet Union he became a victim of McCarthyism. He was black listed as a<br />

performer and his passport was revoked.

14<br />

elocutionist. Paul played leading roles in a number of school<br />

plays. He had many friends. It was in vogue to be a pal of the<br />

multi-talented Paul Robeson. Yet, he never visited the homes<br />

of his white classmates and they never came to his house. He<br />

stayed away from school dances, picnics, and other activities<br />

since it was taboo to be with a “Negro” in a social setting.<br />

New Jersey held a competitive exam for high school students<br />

whereby they would compete to win a four year scholarship<br />

to Rutgers University. The first half of the exam was completed<br />

during junior year, and the second half in June of his senior<br />

year. Paul did not learn about the competition until he was a<br />

senior, and had to take both exams during the senior June exam.<br />

Despite taking the two part exam in one setting he won the<br />

scholarship. This accomplishment gave Paul great confidence,<br />

and he reflected on winning the scholarship under such adverse<br />

conditions by saying: “equality may be denied but I knew that I<br />

was not inferior.”<br />

Upon entering Rutgers University Paul tried out for the football<br />

team. He was the first black player to do so. In the first scrimmage<br />

some of the players tried to discourage him by playing dirty. To<br />

the football squad Paul was taboo. Rutgers had never had a<br />

black player and they were not willing to accept one now. He<br />

left the practice with a broken nose. But there was no “quit”<br />

in him. And to his coach, George Sanford, Paul was in vogue.<br />

Sanford new Robeson was an outstanding high school player<br />

and he was glad to have him on the Rutgers team. The<br />

coach made it clear that racist behavior toward<br />

the black player would not be tolerated. As<br />

a result Paul Robeson made the team and<br />

became an All-American defensive end.<br />

After graduation he moved to New York<br />

to attend Law School at Columbia.<br />

While studying law he maintained<br />

his interest in drama. He was cast in<br />

an amateur production of Simon the<br />

Cyrenne. Ideologically it was a great<br />

role for him. Paul felt that black actors<br />

and actresses were only allowed to be<br />

portrayed as taboo caricatures, but Simon<br />

was a dignified role, and bore the cross for<br />

Jesus Christ. Mary Hoyt Wiborg, a young New<br />

York socialite and aspiring playwright learned<br />

of Paul’s good reviews in the role. Therefore, she<br />

gave him the lead role in a new play, Taboo. It was his<br />

first professional acting job. In the play, superstitious plantation<br />

slaves blame a mute child for a drought that is ruining the crop.<br />

Robeson plays the role of the hero who makes it rain. He is in<br />

vogue as a leading man. But his role is taboo in that he must to<br />

rely on African superstition and voodoo to save the child and<br />

village by making it rain.<br />

Taboo launched Paul’s career as a leading man on the stage<br />

and screen. Most of his films were made in Europe because he

ejected the image that black actors portrayed in Hollywood.<br />

In a 1939 interview he said “I’m afraid of Hollywood …..<br />

Hollywood can only realize the plantation type of Negro - the<br />

Negro of ‘poor Old Joe; and Swanee Ribber.” However, due to<br />

the good reviews he got in the movie The Emperor Jones, and<br />

his concerts Hollywood producers sought him. Robeson’s most<br />

popular Hollywood role was a recreation of his stage character<br />

‘Jim’ in the film version of Showboat.<br />

When critic Emma Goldman reviewed the stage revival of<br />

Showboat she said Paul’s singing and acting was “magnificent,”<br />

(in vogue) but she did not particularly care for the overall theme,<br />

(taboo). The actor and dancer Bill (Bo Jangles) Robinson said he<br />

saw Showboat twice just to hear Robeson sing. Black Nationalist,<br />

Marcus Garvey, spoke of Robeson’s “in vogue” talent and his<br />

“taboo” roles. In The Black Man magazine, Garvey said he was<br />

using “his genius to appear in pictures and plays that<br />

tend to dishonor, mimic, discredit and abuse the<br />

cultural attainments of the Black race.”<br />

In 1942 Robeson appeared in the<br />

Hollywood film Tales of Manhattan. As<br />

an activist in the labor movement, he<br />

hoped his role would highlight the<br />

plight of the poor sharecropper. But<br />

after the editing of this film he was<br />

disappointed at how his character<br />

was portrayed. The New Amsterdam<br />

Star said “Paul Robeson and Ethel<br />

Waters Let Us Down …Luke (Robeson’s<br />

character) was a simple minded docile<br />

sharecropper.” When the film opened<br />

in Los Angles the Sentinel and Tribune<br />

called for picketing the film and Paul said<br />

if a picket line was organized for the New York<br />

opening he would join. Paul had become so upset<br />

he called a press conference and announced he would<br />

never make another Hollywood film. Oscar winning actor Sidney<br />

Poitier summed up the dilemma Paul Robeson and his fellow<br />

black actor’s faced when he wrote:<br />

“None of that generation of black actors - Robeson, Louise<br />

Beavers, Ethel Waters, Hattie McDaniel, Rochester, and Frank<br />

Wilson - was given anything to play that did not characterize<br />

‘minority roles.’ They were appendages to the other actors, the<br />

white actors. They were almost as scenery. To have them as full-<br />

blooded individuals with the ability to think through their own<br />

problems and chart their own course - American films were not<br />

works cited<br />

into that. Difficult as it is today, it is<br />

nowhere near as difficult as it was for<br />

Robeson.” The talent of Paul Robeson and his<br />

fellow black actors was in vogue but their roles for<br />

the most part were still taboo.<br />

Dubberman, Martin Bauml (1988) Paul Robeson. Alfred A Knopf 1988<br />

Robeson, Paul Jr., The Undiscovered Paul Robeson, An Artist Journey<br />

1898-1939. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-24265-9<br />

Robeson, Paul Jr., The Undiscovered Paul Robeson: An Artist Journey<br />

1940-1976. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-40973-1<br />

Brown, Lloyd (1998) On My Journey Now: The Young Paul Robeson.<br />

Basic Books ISBN 0-8133-31773-3<br />

Boyle, Sheila Tully, and Andrew Bunie (2001) Paul Robeson: The Years<br />

of Promise And Achievement. University of Massachusetts Press<br />

about Joseph bundy: Influential African Americans of the late 19th and 20th centuries come alive through Joseph Bundy’s dramatic<br />

Chautauqua impersonations. He has been active in West Virginia and the mid-Appalachian region for years as an actor, playwright, and<br />

poet. But he is best known for his Chautauqua impersonations of James Weldon Johnson Booker T. Washington, A. Philp Randolph, Jim<br />

Europe, and Major Martin R. Delany. He has presented performances and residences for many organizations in West Virginia, Virginia,<br />

Tennessee, Alabama, Kentucky, North Carolina, Maryland, Ohio, Missouri, Kansas, Colorado, Pennsylvania and New York. In 2009 he<br />

portrayed Booker T. Washington for the Enid, OK Winter Chautauqua and Major Delany.

w.c. fields<br />

portrayed by<br />

hank Finken<br />

16

w.c. Fields: not Just another<br />

hollywood pretty Face<br />

by hank Fincken<br />

If you hope to learn the truth about William Claude Fields (1880-<br />

1946) in this year’s Chautauqua, you better be prepared for a lot<br />

of fantasy. Look at his beginnings. A traveling road-show, source<br />

of many youthful dreams of adventure and romance, probably<br />

inspired “Whitey” to become a juggler. As a young professional,<br />

he toured American burlesque houses, Vaudeville stages, and<br />

European music halls — places famous for their tricks, illusions,<br />

and make-believe. Then from 1915-1921, he starred in the<br />

Ziegfeld Follies, with scores of scantily-clad women (male fantasy<br />

in a nutshell), developing the comic routines that would impress<br />

everyone but Ziegfeld.<br />

And most of that was before Hollywood became Hollywood!<br />

In 1900, while touring on the Orpheum Circuit,<br />

the “Eccentric Juggler” brought his new bride,<br />

Harriet Hughes, to Los Angeles, a decade<br />

before the first movie companies arrived. On<br />

a side trip to Pasadena, Fields told “Hattie”<br />

that he would like to own a theatre there or<br />

maybe a grocery store. The climate made<br />

the place perfect to raise a family.<br />

Thirty-one years later, he turned that<br />

fantasy into a reality. Except by that time<br />

he and Hattie had separated, son Claude had<br />

grown up and become a lawyer, and Bill was an<br />

unemployed Broadway star.<br />

The Depression had turned the lights out on his last Broadway<br />

show, Ballyhoo, and a new competitor was threatening the life of<br />

many others. Silent film was developing a voice.<br />

Instead of denouncing the change, Fields embraced it. He<br />

had come a long way from the days when the Silent Humorist<br />

created all his jokes out of cigar boxes, juggling balls, and stoogelike<br />

assistants. The raspy comeback, the one-liner with real or<br />

imagined innuendo, had been part of his routine since the Ziegfeld<br />

days. And sketches too! By 1930, he had sixteen registered at<br />

the library of Congress and another forty in various forms of<br />

development. Fields packed his bags, papers, gags, books, props,<br />

and costumes and headed west, entering the Hollywood Plaza<br />

Hotel like the Prodigal Son home from a naughty vacation. He<br />

arrived with no contracts, no offers, no leads, and no doubts. “If<br />

the west didn’t want me,” Fields later said, “I wanted it.”<br />

He was back in Los Angeles, for the third time.<br />

Fields made his first two films in New York in 1915: The Pool Shark<br />

and His Lordship’s Dilemma. The later is lost, but the former<br />

seems like a training exercise in which pratfalls pass as courtship<br />

and Fields pool skills are replaced by trick photography. Then in<br />

1925, he teamed with director D.W. Griffith to make Sally of the<br />

Sawdust, a film adaptation of Dorothy Donnelly’s Broadway hit,<br />

Poppy, a play which had turned Fields into a Broadway star.<br />

Fields was on his way up; Griffith on his way<br />

out. After three flops, the great director was<br />

desperate for a success. Sally gave it to him<br />

but more because of the story line than his<br />

direction. Fields admired Griffith, but his<br />

role was reduced as the camera focused<br />

on the less talented, always dancing Carol<br />

Dempster, Poppy.<br />

The film still managed to earn Fields<br />

a Paramount contract. After making<br />

four films in New York, he was ordered to<br />

Hollywood, where he starred in four more films<br />

of progressively inferior quality. Fields was one of<br />

those semi-stars, the kind Hollywood big shots never<br />

trust. His suggestions were ignored and the films bombed. When<br />

his contract was not renewed, he returned to Vaudeville in New<br />

York, where he starred Earl Carroll’s Vanities earning a whopping<br />

$5,200 per week. Then the Depression shut him down.<br />

Are you noticing a pattern here? In 1989, George Burns wrote,<br />

“The only thing permanent in show business is insecurity.” I<br />

would call Fields career a roller coaster ride except the thrill of<br />

the ride is in the fall while the thrill of show business is in the<br />

climb to the top. Fields was quite the climber.<br />

By 1930, every American living east of the Rockies and north of San<br />

Francisco saw Hollywood as a dream world – a place where make-<br />

W.C. fieLDs, 1880-1946: He began as a juggler in Burlesque, crafted his humor in Vaudeville, starred in the Ziegfeld Follies and<br />

Broadway from 1915 through 1928, and then found his true voice in the early talkies of the 1930s. Of all the great film stars of the<br />

“Golden Age of Comedy” (including Chaplin, Lloyd, and Keaton), Fields was the only one to blossom with the advent of sound. He had<br />

a huge cult following in the 1960s and has been recently rediscovered as the most modern of the classic humorists.

elieve kisses reality, and wealth is as ordinary as daily chores.<br />

How else do you explain a land that shimmers in sunlight 350 days<br />

a year and where the rules that monitor personal behavior do not<br />

apply? Studio publicists and newspaper columnists encouraged<br />

the idea that the actor and character were one and the same, and<br />

revelry rarely had consequences.<br />

The movies carried audiences to faraway lands where real people,<br />

pretending to be someone else, suffered pretend<br />

problems that needed real solutions. These stories<br />

touched audience’s hearts in ways that actual<br />

experiences rarely do. Actually, the relationship<br />

between Hollywood and the rest of the country<br />

was more complex, more of a love/hate affair;<br />

a Saturday night party with Sunday morning<br />

regrets. Politicians, clergymen, parents, and<br />

concerned citizens demanded restraint.<br />

After the “Fatty” Arbuckle and Wallace Reid<br />

scandals, Postmaster General Will Hays was<br />

asked to organize an institution within the<br />

industry that would set limits, making sure all<br />

movies had a moral tone. In 1930, Hays produced<br />

the Motion Picture Production Code; in 1934, he<br />

gave it some teeth. No movie was released without the<br />

Purity Seal from the Hays Office.<br />

It was an uneasy truce between those who saw humor in<br />

outrage and those who found outrage in humor. Today Fields’<br />

witticism and jabs against authority seem tame, but in the<br />

1930s, the Hays Office saw them as a danger to the moral fabric<br />

of America. The irony is that Fields’ career and the stories he<br />

told often epitomized the American Dream. Fields started poor,<br />

worked hard, and finally—just as he found his greatest success<br />

in the talkies—was told to shut up.<br />

Fields played a tarnished Horatio Alger, a fictional character<br />

as real to 19th century audiences as movie stars were to their<br />

grandchildren in the 1930s. The goals of Alger and the Fields<br />

characters were similar; the road to success as seemingly<br />

impossible. As “the Great McGonigle” in The Old Fashioned Way<br />

(1934), Fields succeeds even as he fails because his self sacrifice<br />

allows his step-daughter to marry into society. The inventor,<br />

Samuel Bisbee, in You’re Telling Me! (1934) will make his fortune<br />

by selling a puncture-proof tire. In It’s a Gift (1934), the henpecked<br />

Everyman, Harold Bissonette, is willing to sacrifice<br />

everything for the chance to grow oranges in California.<br />

What disturbed the Hays Office was not the dream, but the<br />

attitude. With his sarcastic tone that turned mumbles into<br />

philosophical treatises and pretension into belly laughs, Fields’<br />

characters burlesqued sexual mores in International House<br />

(1933), authority figures and sanctimonious relatives in Man<br />

on the Flying Trapeze (1935), the Production Code itself in The<br />

Bank Dick (1940), and the morally astute in My Little Chickadee<br />

(1940). McGonigle even kicked a baby!<br />

18

Other Fields characters would stoop to anything in order to<br />

succeed. They embody the famous Fields quip, “A thing worth<br />

having is a thing worth cheating for.” McGonigle, McGargle, and<br />

Larson E. Whipsnade of You Can’t Cheat an Honest Man (1939)<br />

would lie, scheme, and deceive to keep their circuses afloat,<br />

the humor being in their dastardly incompetence. The censors<br />

fumed, and the audiences howled. These movies were a spiritual<br />

meal ticket for the unemployed, a balm for those depressed by<br />

the Depression. Fields thought the con-artist Wilkins Micawber<br />

(his favorite role) from David Copperfield (1935) was more<br />

honest. His self-serving ramblings reveal more truth than any<br />

politician’s speech.<br />

Sadly, the roller coaster ride eventually came to a stop. In 1942,<br />

Fields starred in Tales of Manhattan, a forgettable collection of<br />

stories about a hand-me-down suit coat. Fields plays Professor<br />

Diogenes Pothlewhistle, who imbibes while giving a temperance<br />

lecture. It’s the old shtick without the old energy, the funny<br />

drunk more drunk than funny. Before the film was released,<br />

Fields’ tale was cut. Paul Roberson, star of a different tale, hated<br />

the film. He felt his role was reduced to a stereotype and would<br />

have preferred it lay on the cutting room floor beside Fields’.<br />

Radio made Fields a national star again but at a price.<br />

He played the role people expected of him, drinking<br />

too much and hating little children, especially the<br />

puppet Charlie McCarthy. If Fields could not<br />

always separate his real self from his fictional<br />

self, please don’t expect me to either. The<br />

true Fields is only an illusion, just as “reality”<br />

is always as temporary as spring. Perception<br />

is truth, and each generation redefines that<br />

truth according to its own self image. If not, the<br />

definitive biography of every great American would<br />

have been completed long ago.<br />

Welcome to my 2011 version of the real W.C. Fields. One of Fields<br />

most famous lines reads, “Life is a funny old thing. A man is lucky<br />

to get out of it alive.” Bravo, Mr. Fields. I’ll drink to that.<br />

w. c. Fields bibliography<br />

and recoMMended reading list<br />

Brownlow, Kevin; The Parade’s Gone By; London; c 1968.<br />

Burns, George; All My Best Friends; G.P Putnam’s Sons; New York; c. 1989.<br />

Curtis, James; W.C. Fields: A Biography; Back Stage Books; New York; c.2004.<br />

Everson, William K.; The Art of W. C. Fields; Bonanza Books; New York c. 1967.<br />

Fields, Ronald; W. C. Fields By Himself; Prentice-Halls, Inc, Englewood<br />

Cliffs, N.J.; c. 1973.<br />

Fields, W.C.; Fields for President; Dodd, Mean, & Company; New York;<br />

c.1939.<br />

Louvish, Simon; Man on the Flying Trapeze, Faber and Faber Limited,<br />

London; c1997.<br />

Mast, Gerald; The Comic Mind; The University of Chicago Press; c.1979.<br />

Monti, Carlotta; W.C. Fields and Me; Warner Books; USA; c.1971.<br />

Taylor, Robert Lewis; W. C. Fields: His Follies and Fortunes; Signet Books,<br />

New York; c. 1949 and 1967.<br />

W. C. fields: Comedy Collection; Universal Studios.<br />

W. C. fields: Comedy Collection Volume 2, Universal Studios.<br />

about hank Finken: For more than twenty years, Hank Fincken has toured the U.S. performing his original one-man plays in schools,<br />

parks, libraries, festivals, and universities. His characters include Thomas Edison, Johnny Appleseed, Francisco Pizarro, Christopher<br />

Columbus, Henry Ford, and an 1849er on The California Trail named J. G. Bruff. He added W.C. Fields in 2010. This will be Hank’s fifth<br />

Oklahoma CHAUTAUQUA. He has recently performed in Chautauquas in Ohio, South Carolina, Missouri, Illinois, and Colorado. A prolific<br />

writer, he has authored scores of plays, stories, and essays as well as one book: Three Midwest History Plays and Then Some. Hank has<br />

special permission to recreate the image and likeness of W.C. Fields, granted by W.C. Fields Productions.

walt disney<br />

portrayed by<br />

dr. williaM worley<br />

20

walt disney: innovator in the<br />

golden age oF hollywood<br />

by dr. williaM worley<br />

Walt Disney stands out as very possibly the most influential<br />

individual in shaping American society in the middle third of<br />

the 20th century. Innovating in such aspects of filmmaking<br />

as animation design, sound and color filmmaking, wildlife<br />

photography, and amusement park design, Disney excelled in the<br />

mediums of film, phonographic recording, and television.<br />

From a business perspective, Walt Disney Studio pioneered<br />

and predominated in the area of synergy of cross-promotion of<br />

products as early as the late 1920s when Mickey Mouse became<br />

a multi-media threat. Of course, Disney’s storytelling skills, both<br />

personally and corporately, remain unsurpassed. The term, “the<br />

Disney version” has come to have profound meaning both<br />

positively and negatively.<br />

Walt was born in Chicago, IL in 1901 to a<br />

Canadian-born father and Ohio-born mother<br />

who met in Kansas and married in Florida.<br />

He was the fourth of five children and the<br />

youngest of four sons. His older brother<br />

Roy early became his protector within<br />

the family and later served as his business<br />

partner and confidant. However, within his<br />

family Walt stood out as a creative force<br />

surrounded by parents and siblings who<br />

held more mundane goals.<br />

Walt’s golden period occurred between 1905 and 1910<br />

in Marceline, Missouri where he experienced a childhood<br />

filled with farm animals and elaborate escapades. On one occasion,<br />

he got to ride in a buggy with Buffalo Bill Cody when the latter<br />

brought his Wild West show to town. Another time, he witnessed a<br />

performance of “Peter Pan” by the international stage star, Maude<br />

Adams. This brought him later to perform the lead in “Peter Pan”<br />

himself with Brother Roy pulling the ropes to make him fly.<br />

Walt’s later experience in Kansas City was not so idyllic. Father<br />

Elias Disney was a contract deliveryman for the Kansas City<br />

Star. Thirteen times a week, Walt trudged to the Star office over<br />

two miles away to pick up almost 100 papers to deliver. He saw<br />

none of the money because his father invested his share in an<br />

ill-fated Chicago jelly manufacturing company. Walt never forgot<br />

the dreariness of his existence nor the occasional escapes from<br />

it through his classes and activities at Benton Elementary in<br />

Midtown Kansas City.<br />

After completing one year of high school in Chicago in 1917-<br />

18, Walt joined the Red Cross and drove supply trucks in France<br />

following the end of World War I. Returning to Kansas City<br />

after the War, he began an unsuccessful four-year<br />

effort in animation and live-action filming in his<br />

old hometown. By 1923, he left all his failures<br />

behind to join Brother Roy in Los Angeles.<br />

Walt thus entered, stage left, onto<br />

Hollywood’s Silver Screen just as it was<br />

entering its own Golden Era.<br />

Walt did take some positive things with him<br />

from Kansas City. These included creative<br />

ideas and one pilot film for a combination<br />

live-action/animation short film called “Alice’s<br />

Wonderland.”<br />

It took five years that included occasional success with<br />

the “Alices” and another cartoon character called Oswald the<br />

Rabbit, but by spring 1928, Walt was reduced to a staff of only<br />

a few animators and no cartoon characters because of treachery<br />

by distributors and business associates. Out of that despair,<br />

Walt dredged up thoughts of various mice that had “graced” his<br />

drawing board in Kansas City and performed in his mind over the<br />

WaLt Disney, 1901-1966: Walter Elias Disney was born in Chicago, IL on December 5, 1901. The family moved to Marceline, Missouri,<br />

when Walt was four. After completing a year of high school in Chicago in 1917, Walt volunteered for abulance service with the Red<br />

Cross. Although arriving in France too late for the War, Walt gained about a year of overseas experience. Upon returning to the U.S.,<br />

Walt chose to live in Kansas City with his veteran brother Roy. During this period he attempted to develop an animation studio and<br />

conceived his first animated-live action short, Alice’s Wonderland. Over the next few years Walt developed several series of animated/<br />

live action and strictly animated series. In 1928, this list came to include Mickey Mouse who became the first sound/animated charcter<br />

in history. Walt produced the first feature-length animated film in the form of Snow White. After World War II, Walt launched a series<br />

of animated/live-action features. In order to realize his dream financially, he made a deal with the fledgling ABC television network.<br />

Without realizing it at the time, Walt helped conclude the Hollywood Golden Era by leading film production companies into the new<br />

technology of television and the new format of Disneyland. Walt passed away on December 15, 1966. Walt won 32 personal Academy<br />

Awards. Walt Disney Productions and its employees won an additional 16 Oscars during Walt’s lifetime.

years. The result in the summer of<br />

1928 was Mickey!<br />

Largely drawn by one of Walt’s few<br />

remaining animator collaborators,<br />

Ub Iwerks, originally of Kansas City,<br />

Mickey proved to be an almost instant<br />

success. Part of this came from the<br />

timing of sound movies coming on the<br />

scene. Walt and Ub Iwerks completed<br />

“Steamboat Willie” as the first sound<br />

cartoon in history by August 1928. A year later,<br />

new Mickey Mouse cartoons appeared every<br />

three weeks or so, and Mickey Mouse dolls cropped up<br />

in many households.<br />

Walt Disney Studios followed this with the first color and sound<br />

cartoon “Flowers and Trees” in 1932, the phenomenon of “Three<br />

Little Pigs” in 1933, and the first cartoon feature film ever, “Snow<br />

White,” in 1937. Grossing over $8.5 million world-wide, “Snow<br />

White” became the highest grossing movie of all time…until 1939<br />

when it was surpassed by “Gone With the Wind.”<br />

But, as we shall discover together, Walt’s impact with “Snow White”<br />

came only after years of hard work, motivating sessions, and<br />

creative ideas that transformed this aspect of moviemaking. It is<br />

an adventure into the human mind and expressive personality of<br />

Walter Elias Disney.<br />

It was not all roses after “Snow White.”<br />

While today we consider such films as<br />

“Pinocchio,” “Fantasia” and “Bambi”<br />

as classics [some even consider<br />

“Pinocchio” to be the best cartoon<br />

feature ever made!], none of those<br />

films made money for the studio.<br />

Besides “Snow White,” only “Dumbo”<br />

produced a profit before World War II.<br />

The summer of 1941 witnessed a disruptive<br />

strike as unions attempted to organize the<br />

Disney animators and other craftspeople. Part of<br />

what generated the strike was Walt’s rather dictatorial<br />

management style in working with other creative people who<br />

craved both monetary and inspirational rewards. Walt had<br />

difficulty providing the latter especially.<br />

While the studio produced several successful live action and<br />

animated feature films [“So Dear to My Heart,” “Cinderella”<br />

and “Peter Pan”] in the post-war period, some combination<br />

live action/animated features, especially “Song of the South,”<br />

proved less well-accepted. “Song of the South” also generated a<br />

controversy over its portrayal of post-Civil War African Americans<br />

that lasts to this day.<br />

The idea that fully brought the studio out of its doldrums was one<br />

that Walt dreamed up after failing to find good Sunday afternoon<br />

22

amusements for his daughters. He thought there ought to be<br />

amusement experiences that the whole family might enjoy in a<br />

safe, clean atmosphere. Out of this quest emerged “Disneyland”—<br />

first the television show and then the amusement park. He used<br />

the TV show on the struggling ABC network to finance the final<br />

construction and opening of the Anaheim site.<br />

In turn, the television show became the hit of the 1954-55 season,<br />

garnering Emmys for, among other things, a show that was<br />

almost an infomercial for Disney’s new movie “Twenty Thousand<br />

Leagues Under the Sea.” The Emmy recognized the<br />

“Disneyland” episode as the single best television<br />

program of the season!<br />

Walt’s last vision—EPCOT—turned out<br />

somewhat differently than he had<br />

planned, but today the studio, the parks,<br />

the movies, the television channels<br />

and the merchandising bonanza have<br />

created one of the most consistently<br />

successful Hollywood stories ever.<br />

Walt Disney’s role throughout<br />

Hollywood’s Golden Age largely<br />

diverged from the norm. When almost<br />

everyone else concentrated on human<br />

stories told by human actors, Walt Disney<br />

Productions centered on animation, fairy<br />

tales, music and technological innovation in<br />

sound and image to take the art of motion pictures<br />

further than anyone else.<br />

Walt produced the first sound cartoon within a year of the first<br />

partly-sound motion picture. He was a pioneer in using the<br />

Technicolor process. His studio’s advanced camera techniques<br />

paved the way for later animated development in the digital era.<br />

And, he developed stereophonic sound to enhance the audience<br />

experience for his wildly imaginative Fantasia in 1940. All of these<br />

improvements have become standard in the industry.<br />

His willingness to use television to enhance his auxiliary<br />

enterprises such as Disneyland spelled the end of the studio<br />

system that had made live-action pictures for over a quarter<br />

century. Yet, he moved more and more into live action pictures<br />

himself just as other studios began to compete more aggressively<br />

in his premier field of animation.<br />

Walt Disney was in exactly the right spot to experience the Gold<br />

Age of Hollywood…and of America.<br />

walt disney bibliography<br />

For children and young people:<br />

Marie Hammontree, Walt Disney: Young Moviemaker,<br />

1969, 1997<br />

Bernice Selden, The Story of Walt Disney: Maker of Magical<br />

Worlds, 1989<br />

For More advanced readers:<br />

Dave Smith and Steven Clark, Disney: The First 100 Years,<br />

updated edition, 2003<br />

For adults:<br />

Walt Disney by Neal Gabler, 2006. The best biography<br />

currently available.<br />

The Magic Kingdom by Steven Watts, 1997<br />

A somewhat critical treatment: The Disney<br />

Version by Richard<br />

Schickel, 1968, 3rd ed., 1998<br />

about dr. williaM worley: Dr. William S. Worley is a full-time Instructor of History at Metropolitan Community Colleges of Kansas<br />

City-Blue River and an experienced Chautauquan. Currently, he regularly takes on the persona of Tom Pendergast, KC political boss;<br />

President Harry S. Truman; basketball inventor James Naismith; Jewish compatriot of John Brown in Bleeding Kansas August Bondi,<br />

and, of course, Walt Disney. Worley believes that history is not something to be put on shelf, but to be lived and discussed. Married with<br />

three grown sons and three grandchildren, Worley has been a scholar-performer in numerous Chautauquas.

lawton, ok enid, ok<br />

May 31-June 4<br />

evening perForMances at 7:30 p.M.<br />

lawton public library plaza<br />

110 sW 4th st, LaWton, oK 73501<br />

workshops<br />

10 a.M. – CaMeron uniVersity theater<br />

2 P.M. – MuseuM of the Great PLains<br />

Co-sPonsors<br />

City of Lawton<br />

City of Lawton Parks & Recreation<br />

Friends of the Library<br />

Lawton/Fort Sill Chamber of Commerce<br />

Lawton Arts & Humanities Council<br />

Lawton Noon Lions<br />

coMMunity partners<br />

David Snider, Director,<br />

Lawton Public Library<br />

Dory Thomas & Circulation Desk Staff,<br />

Lawton Public Library<br />

Billie Whipp, City of Lawton Arts<br />

& Humanities Division<br />

Charlie Clark, Lawton Constitution<br />

Cody Holt, Great Plains<br />

Technology Center<br />

David Hale, Lawton Constitution<br />

Deborah Baroff, Museum<br />

of the Great Plains<br />

Dr. Anita Hernandez,<br />

Lawton Public Schools<br />

Dr. Judy Neale, Cameron<br />

University/ Library<br />

Frantzie Couch, Friends of the Library<br />

Gordon Blaker, U.S. Army Artillery<br />

Museum at Fort Sill<br />

Jane Mitchell, Success By 6<br />

Marilyn Grijak, Southwest Opera Guild<br />

Joan Auwen & Jill Manley,<br />

Nye Library at Fort Sill<br />

Patty Neuwirth, Friends of the Library<br />

Ruben Sotelo, International Group<br />

Sue Smith, City of Lawton Public Works<br />

Susanna Fennema,<br />

Retired Librarian<br />

library board<br />

James Burpo<br />

Carol Sinnreich<br />

Pamela Bonnell-Mihalis<br />

Lynn McIntosh<br />

Sally Cote<br />

Friends oF the<br />

library board<br />

Patty Neuwirth<br />

Dr. Judy Neale<br />

Frantzie Couch<br />

Margaret McCracken<br />

24<br />

June 14-18<br />

entertainMent at 6:30 P.M.<br />

presentations at 7:30 p.M.<br />

cherokee strip regional heritage center<br />

507 s. 4th st., eniD, oK<br />

workshops daily at 10:30 a.M. and noon<br />

at the huMphrey village churcy<br />

<strong>chautauqua</strong> council oF enid, inc.<br />

P.o. box 10502, eniD, oK 73706<br />

for More inforMation CaLL 580-551-9792.<br />

oFFicers<br />

Kathi Box, President<br />

Diane Ford, President Elect<br />

Jane Denker, Secretary<br />

Sally Whiteneck, Treasurer<br />

proJect directors<br />

John Provine<br />

Laurel Provine<br />

advisory board<br />

Gary Brown<br />

Colleen Flikeid<br />

Bill Harris<br />

Andi Holland<br />

David Trojan<br />

Sharon Trojan<br />

Wally Turner<br />

star MaJor event sponsor<br />

Oklahoma Humanities Council<br />

Harris Foundation<br />

Cherokee Strip Regional Heritage Center<br />

Northwestern Oklahoma State University<br />

Enid Convention and Visitors Bureau<br />

Pegasys<br />

United Supermarkets<br />

gold supporter<br />

Central National Bank<br />

Integris Bass Baptist Health Center<br />

Panevino<br />

Questus Corporation<br />

Security National Bank<br />

Tinker Federal Credit Union<br />

Wally Turner<br />

silver supporter<br />

Brenda Faust<br />

Lippard Auctioneers<br />

Park Avenue Thrift<br />

bronze supporter<br />

David and Sharon Trojan<br />

Effie Outhier<br />

Jumbo Foods<br />

board MeMbers<br />

Carmen Ball<br />

George Davis<br />

Diane Ford<br />

Jon Ford<br />

DeLisa Ging<br />

Mike McIlwee<br />

Michelle Mears<br />

Ann Ritchie<br />

Daron Rudy<br />

Patty Trimmer<br />

Judy Winchester

sponsors<br />

In its 20th continuous year, the Oklahoma Chautauqua is a program of the Arts & Humanities Council of Tulsa.<br />

Major funding is provided in part by a grant from the Oklahoma Humanities Council. Additional<br />

support for this program is provided by the following: Oklahoma State University – Tulsa,<br />

The Mervin Bovaird Foundation, The Judith & Jean Pape Adams Charitable<br />

Foundation, Williams, and the Downtown Double Tree Hotel.<br />

the Mervin bovaird<br />

foundation<br />

the Judith & Jean Pape<br />

adams Charitable<br />

foundation