Criminal Justice Matters - 2011march - Canadian Harm ...

Criminal Justice Matters - 2011march - Canadian Harm ...

Criminal Justice Matters - 2011march - Canadian Harm ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

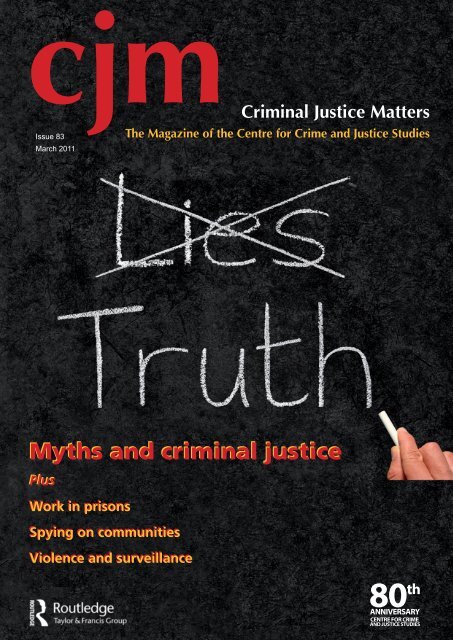

cjmThe<br />

Magazine of the Centre for Crime and <strong>Justice</strong> Studies<br />

Issue 83<br />

March 2011<br />

<strong>Criminal</strong> <strong>Justice</strong> <strong>Matters</strong><br />

Myths and criminal justice<br />

Plus<br />

Work in prisons<br />

Spying on communities<br />

Violence and surveillance<br />

rCJM No 83.indd 1 25/02/2011 07:43:01

EC DO INT TO ER NI AT SL<br />

EDITORIAL<br />

The labours of Sisyphus?<br />

Will McMahon and Tammy McGloughlin introduce this issue of<br />

cjm. 1<br />

TOPICAL ISSUES AND COMMENT<br />

Violence and surveillance in mental health wards 4<br />

Suki Desai considers the negative impact on vulnerable people.<br />

Protecting endangered species 6<br />

Jasper Humphreys and M L R Smith discuss how laws are being<br />

undermined in areas of conflict.<br />

Immigration detention in Northern Ireland 8<br />

Robin Wilson reports on the lack of due process for asylum<br />

seekers.<br />

A lesson in how not to spy on your community? 10<br />

Imran Awan discusses how the balance between security and<br />

intrusion has undermined community relations.<br />

THEMED SECTION: MYTHS AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE<br />

The hall of mirrors: criminal justice myths uncovered 12<br />

Rebecca Roberts considers the distortions and myths described<br />

in the themed section of cjm.<br />

New Labour’s crime statistics: a case of ‘flat earth news’ 14<br />

Tim Hope examines the distortions behind the crime statistics.<br />

Crime: myth or reality? 18<br />

Richard Garside considers definitions of crime in the myth<br />

making process.<br />

Truth and lies about ‘race’ and ‘crime’ 20<br />

Will McMahon and Rebecca Roberts consider ethnicity, harm<br />

and crime.<br />

<strong>Justice</strong> is a way of being, not a moment in court 22<br />

Charlotte Weinberg discusses the myth of justice in an unequal<br />

society.<br />

Are drugs to blame? 24<br />

Alex Stevens considers the evidence on drug-related crime.<br />

‘Saints and scroungers’: constructing the poverty and crime<br />

myth 26<br />

Lynn Hancock and Gerry Mooney question the supposed links<br />

between poverty, immorality and crime.<br />

Understanding the demonised generation 28<br />

Brian McIntosh and Annabelle Phillips challenge the view that<br />

young people are responsible for society’s ills.<br />

Contents<br />

cjm No 83 March 2011<br />

Policing myths 32<br />

Megan O’Neill explores the myth that bobbies on the beat cut<br />

crime.<br />

The ‘alternative to custody’ myth 34<br />

Helen Mills questions claims that community sentences cut<br />

prison numbers.<br />

DEBATING... SHOULD PRISONERS WORK?<br />

Should prisoners work from 9-5? 37<br />

Joe Black, Mark Day, Steve Gillan and Gemma Lousley offer<br />

their views on plans to implement a 40-hour working week<br />

with minimum wages for prisoners.<br />

REVIEW<br />

Reflections on international youth justice: 40<br />

a personal view<br />

Rod Morgan is shocked by the imagery at a recent youth justice<br />

conference.<br />

For advertising email:<br />

tammy.mcgloughlin@crimeandjustice.org.uk<br />

Copyright<br />

We know that cjm is popular, and widely used in educational and<br />

training contexts. We are pleased you like the magazine. However we<br />

are concerned about an apparent proliferation of photocopying. You<br />

may be breaking the law.<br />

The Copyright Licensing Agency permits the copying of ONE article<br />

per issue of a journal or magazine, under its current licensing<br />

arrangement. As a rule, no more than NINE copies, may be made.<br />

The CLA is being increasingly strict about infringements of its scheme.<br />

And you need to have a license.<br />

Printed in the United Kingdom by Hobbs the Printers Ltd,<br />

Totton, Hampshire, SO40 3WX<br />

Website: www.hobbs.uk.com<br />

rCJM No 83.indd 2 25/02/2011 07:43:01

This year the Centre for Crime and <strong>Justice</strong> Studies is<br />

celebrating its 80 th anniversary (see page 3). Throughout<br />

these 80 years there have been a number of recurring<br />

myths about ‘crime’ and criminal justice that the Centre<br />

has sought to challenge. So it is appropriate that the<br />

contributors to this issue’s themed section, edited by<br />

Rebecca Roberts, systematically tackle a number of<br />

the most enduring myths about criminal justice. The<br />

debunking of one myth may be achieved by appealing<br />

to another, so it is only when reading the articles as<br />

one piece that the true scale of the myth-busting that is<br />

required becomes clear.<br />

In the topical section, surveillance technology is<br />

considered. Is it the efficient harm prevention measure<br />

we have been led to believe? Articles by Suki Desai and<br />

Imran Awan focus on how cameras have been introduced<br />

with the rationale of having beneficial effects, but with<br />

the practical implementation revealing adverse<br />

consequences. Desai describes how the use of<br />

surveillance within mental health hospitals, introduced as<br />

a measure to reduce violent attacks on staff in practice,<br />

‘has the potential for undermining the intimacy and<br />

therapeutic relationship between ward staff and patients.’<br />

and explains that, to date, there has been no full<br />

evaluation of their efficacy.<br />

Meanwhile, Awan considers the use of surveillance in<br />

the predominantly Muslim areas of the West Midlands.<br />

He argues that the police targeted specific areas using<br />

tactics that ‘are both heavy handed and counterproductive’<br />

and suggests that the deployment of CCTV,<br />

ostensibly introduced to tackle ‘anti-social behaviour’,<br />

has, in fact, marginalised the neighbourhood by using the<br />

cameras as a means to ‘spy’ on residents. He concludes<br />

that in order to mitigate against the damage caused to the<br />

community, the police will now have to attempt to<br />

rebuild trust by admitting their mistakes.<br />

The targeting of particular groups is also addressed by<br />

Robin Wilson, who reports on the lack of due process for<br />

asylum seekers. He cites their experiences of being held<br />

in police custody over time and without automatic access<br />

to legal assistance. Wilson highlights the arbitrariness and<br />

humiliations of being treated as ‘criminal or even<br />

terrorist’ where customary norms of the law are not<br />

applied.<br />

A subject often on the periphery of the law, the<br />

protection of endangered species, is described by Jasper<br />

Humphreys and M L R Smith; they discuss how, in spite<br />

of international legal conventions and protocols, wildlife<br />

and biodiversity are severely threatened. Trading in, for<br />

example, ivory and rhino horn, provide low-risk<br />

cjm no. 83 March 2011 ©2011 Centre for Crime and <strong>Justice</strong> Studies 1<br />

10.1080/09627251.2010.536435<br />

The labours of Sisyphus?<br />

Will McMahon and Tammy McGloughlin<br />

introduce this issue of cjm.<br />

profiteering for poachers and the consequent falling<br />

numbers of already endangered species. While there<br />

appears to be no impetus to enforce legislation,<br />

conservationists have engaged public awareness and<br />

support in an effort to protect species from extinction.<br />

Our debating section considers the proposal, put<br />

forward by the <strong>Justice</strong> Minister Ken Clarke, for a 9 to 5<br />

minimum wage work routine for those in prison. This has<br />

sparked a widespread debate, with some regarding the<br />

proposal as a viable route for the incarcerated getting a<br />

dose of the ‘work ethic’, while others have a much more<br />

critical view. Part of this exchange takes place in this<br />

issue’s debating section, with contributions from Joe<br />

Black representing the Campaign Against Prison Slavery<br />

who sees the idea as ‘a vision of a neo-Victorian<br />

rehabilitation regime’, while Mark Day from the Prison<br />

Reform Trust argues that the plan is ‘in principle,<br />

absolutely right.’<br />

From a trade union perspective, Steve Gillan, General<br />

Secretary of the Prison Officers Association, suggests that<br />

if we are to get prison numbers down then getting to<br />

grips with the problems those in prison face should be<br />

our first concern. He also believes that the idea of private<br />

companies laying off workers outside the walls, to<br />

employ cheap labour inside, is a moral problem.<br />

Meanwhile Gemma Lousley, of the <strong>Criminal</strong> <strong>Justice</strong><br />

Alliance, asks a crucial question: ‘If prisons remain<br />

overcrowded, how will there be enough staff to supervise<br />

prisoners working a 40-hour week?’.<br />

Finally, in a short but potent article, Professor Rod<br />

Morgan offers his personal reflections on a recent<br />

conference on youth justice he attended in Italy, and<br />

describes the impact, on him and others, of images<br />

presented at the conference. The first, a montage of film<br />

clips drawn from a drug centre and youths in custody in<br />

Chile, left many in the conference stunned; the second, a<br />

series of photographs from a Texas boot camp that reveal<br />

‘embedd[ed] hate in Good Ole Texas’.<br />

This last article reminds us that attempting to radically<br />

change criminal justice can appear a Sisyphean task.<br />

After 80 years there is still much to do. Is it true, as<br />

Camus wrote in in his 1942 essay The Myth of Sisyphus<br />

‘The struggle itself towards the heights is enough to fill<br />

a man’s heart.’? However you answer the question<br />

yourself, we hope you can support us in our efforts by<br />

making a contribution to our anniversary appeal. n<br />

Will McMahon is Policy Director and Tammy McGloughlin is Project<br />

Support Officer at the Centre for Crime and <strong>Justice</strong> Studies.<br />

rCJM No 83.indd 1 25/02/2011 07:43:01<br />

E D I T O R I A L

E D I T ON RE IWA SL<br />

2<br />

News from the Centre for<br />

Crime and <strong>Justice</strong> Studies<br />

Annual Event<br />

On January 20, the Centre held its Annual Event:<br />

Utopia or Dystopia? Living in hope not fear.<br />

Professor Vincenzo Ruggiero, Baroness Vivien<br />

Stern, Professor Rod Morgan and Professor David<br />

Nutt each vividly expressed their hopes and fears<br />

for the future. The event was well attended and the<br />

audience responded with comments and questions<br />

for the panel. An enjoyable evening was had by all!<br />

HOME SWEET HOME<br />

Announcement: the Centre has<br />

teamed up with the Open University<br />

We are pleased to announce that the Centre has become a formal partner of<br />

the International Centre for Comparative Criminological Research (ICCCR) which is<br />

based in the Faculty of Social Sciences at the Open University. ICCCR is a unique<br />

multi disciplinary and cross faculty initiative drawing on expertise from Social<br />

Sciences and Health and Social Care; and from the affiliated International Centre<br />

for the History of crime, policing and justice, based in the Faculty of Arts. For more<br />

details about the ICCCR and the friends that we will be collaborating with please<br />

visit: www.open.ac.uk/icccr<br />

LIKE US? THEN SUPPORT US!<br />

You can support our work by signing up for our free monthly e-bulletin, attending<br />

our events, using our publications, and all importantly – telling us what you think!<br />

If you want to take it one step further, then please consider joining the Centre as<br />

a member. From £25 per year you can receive <strong>Criminal</strong> <strong>Justice</strong> <strong>Matters</strong> as well as<br />

receiving access to additional resources and benefits. While we enjoy your moral<br />

support, a bit financial help never goes amiss!<br />

The Centre for Crime and <strong>Justice</strong> Studies has relocated to new<br />

offices at 2 Langley Lane, London, SW8 1GB.<br />

www.crimeandjustice.org.uk<br />

©2011 Centre for Crime and <strong>Justice</strong> Studies<br />

Photographs courtesy of Melinda Kerrison and Ed Brenton<br />

rCJM No 83.indd 2 25/02/2011 07:43:03

Help us to inspire enduring change -<br />

80 th Anniversary Appeal<br />

The Centre for Crime and <strong>Justice</strong> Studies is celebrating its eightieth anniversary<br />

year in 2011. Throughout our history we have had a track record of policy<br />

independence and research integrity. Our commitment to the evidence base<br />

means that we do not endorse ‘flavour of the month’ policy solutions. Our<br />

commitment to independence means that we do not attempt to take the ‘inside<br />

track’ with the government of the day. Instead, we seek to focus on fact rather<br />

than myth, with the aim of inspiring enduring change.<br />

In 1931, the world was living through a major financial crisis. Eighty years<br />

on we face equally uncertain times that will be challenging and will need<br />

independent and critical thinking; the Centre stands ready to meet this<br />

challenge while maintaining its tradition of honesty and working in the public<br />

interest. To do this, independent sources of funding are crucial; so we are<br />

asking all those who support our mission and values to help us by making a<br />

donation to our 80th Anniversary Appeal.<br />

You can make a donation by visiting our website:<br />

www.crimeandjustice.org.uk/80thanniversaryappeal.html<br />

rCJM No 83.indd 3 25/02/2011 07:43:04

T O p I C A L I S S u E S A N D C O m m E N T<br />

4<br />

Violence and<br />

surveillance in mental<br />

health wards<br />

Suki Desai considers the negative impact<br />

on vulnerable people.<br />

It is estimated that there are now<br />

over four million closed circuit<br />

television (CCTV) cameras in Britain<br />

watching our every move. The<br />

increased use of CCTV monitoring<br />

and surveillance within public<br />

areas has received much research<br />

attention, and there is now a critical<br />

body of surveillance literature on<br />

the implications of such watching<br />

within urban and street settings.<br />

Despite the announcement of<br />

the new coalition government to<br />

limit the use of CCTV and better<br />

regulation of CCTV in public<br />

spaces, CCTV cameras have become<br />

an established tool as a crime<br />

prevention and security measure.<br />

They are now widely adopted by<br />

both public authorities, such as local<br />

authorities and police, as well as<br />

private citizens in the prevention of<br />

crime. This is despite the fact that<br />

the Home Office’s own research<br />

suggests that CCTV cameras are<br />

an ‘ineffective tool if the aim is to<br />

reduce overall crime rates and make<br />

people feel safer’ (Gill and Spriggs,<br />

2005).<br />

Public concern and research has<br />

tended to focus largely on the use of<br />

CCTV surveillance within urban<br />

spaces and little attention has been<br />

paid to the use of this new<br />

surveillance technology and its<br />

effects inside organisations. CCTV<br />

cameras are now to be found inside<br />

schools, children’s nurseries and<br />

playgroups, care homes, probation<br />

hostels and mental health hospitals.<br />

CCTV cameras have crept into these<br />

organisations with surprisingly little<br />

challenge. In these spaces the<br />

cameras are not deployed to watch<br />

‘strangers’, although this may be one<br />

of its imperatives; they are primarily<br />

©2011 Centre for Crime and <strong>Justice</strong> Studies<br />

10.1080/09627251.2011.550146<br />

deployed to watch people or<br />

children who are known and need to<br />

be watched for their own protection<br />

and safety. The altruistic perception<br />

of the cameras carrying out an<br />

important function renders them<br />

benign instruments; after all who<br />

would not want their child to<br />

be safe whilst at nursery or in<br />

school?<br />

CCTV intrusion?<br />

CCTV cameras have featured as a<br />

surveillance tool inside mental health<br />

hospital wards since 2002. Their<br />

initial use appears to be sanctioned<br />

by the Department of Health as part<br />

of their zero tolerance campaign in<br />

order to reduce<br />

the number of<br />

violent attacks<br />

on staff working<br />

within NHS<br />

learning disability<br />

and mental health<br />

hospitals. It is<br />

difficult to state<br />

exactly how<br />

many hospitals<br />

actually use CCTV<br />

surveillance<br />

in ward<br />

environments as<br />

there is no one body that maintains<br />

such information. A preliminary<br />

survey undertaken in July 2008<br />

(cited in Desai, 2009) suggests that<br />

there were about 34 NHS Mental<br />

Health Trusts using CCTV in patient<br />

accessed areas during this time.<br />

This amounts to 157 wards in 85<br />

hospitals. The cameras were located<br />

in patient bedrooms, seclusion<br />

rooms, patient accessed toilets,<br />

patient lounge areas, patient dining<br />

rooms, education rooms, activity<br />

rooms and viewing rooms. The<br />

Dissent and avoidance<br />

of cameras as a way of<br />

resisting surveillance<br />

can be interpreted as<br />

signs of illness within<br />

mental health settings.<br />

types of mental health hospitals<br />

using CCTV included hospitals that<br />

provide secure environments, acute<br />

inpatient units, specialist eating<br />

disorder units, units that care for<br />

children and young adolescents<br />

with mental health problems, and<br />

learning disability and psychiatric<br />

intensive care units. This information<br />

does not include all NHS trusts<br />

and also does not include private/<br />

independent hospitals; hence the<br />

actual use of CCTV within ward<br />

environments is likely to be higher.<br />

Suspicious behaviour<br />

The intended purpose of the cameras<br />

is to provide a safe environment<br />

for staff, patients and any visitors,<br />

and whilst this purpose may appear<br />

straightforward, in their actual<br />

use they present a number of<br />

complications. The use of CCTV<br />

cameras within hospital wards is not<br />

based on reciprocity and patients<br />

do not have a choice as to whether<br />

they are monitored or not. Dissent<br />

and avoidance of cameras as a way<br />

of resisting surveillance can be<br />

interpreted as signs of illness within<br />

mental health settings. Indeed it has<br />

the added disadvantage for making<br />

a patients’<br />

behaviour look<br />

more suspicious,<br />

especially if the<br />

watching is out<br />

of context and<br />

undertaken by<br />

staff who do not<br />

know a patient<br />

very well, such<br />

as security<br />

guards. The fact<br />

that patients<br />

within mental<br />

health hospital<br />

wards operate at varying levels<br />

of perception and cognition also<br />

influences how they react to cameras<br />

and for some patients the existence<br />

of cameras is likely to incite a<br />

violent response, especially if their<br />

mental health problems are linked<br />

to feelings of paranoia. It is these<br />

aspects that make gaining informed<br />

consent from patients for the use of<br />

cameras problematic.<br />

The issue of violent attacks on<br />

staff by patients is a serious one. The<br />

National Audit results (Healthcare<br />

rCJM No 83.indd 4 25/02/2011 07:43:04

Commission and the Royal College<br />

of Psychiatry, 2005) suggest that in<br />

the period 2004-2005 alone there<br />

were approximately 43,000 assaults<br />

reported by staff working in learning<br />

disability and mental health<br />

hospitals. Violence is not precipitated<br />

one-way and whilst violence to<br />

patients has not been given much<br />

prominence within mental health<br />

research, the fact that cameras can<br />

also capture violence from staff to<br />

patients cannot be underestimated.<br />

The deaths of Esmin Green and<br />

Wang Xiuying both posted on<br />

YouTube, whilst not saving these<br />

women’s lives, allows for some level<br />

of justice for the relatives affected by<br />

their death. Claims have been made<br />

by patients of serious crimes, such as<br />

rape, within mental health wards and<br />

it is clear that these hospital wards<br />

remain unsafe places for both staff<br />

and patients. Whether CCTV<br />

surveillance is the solution to the<br />

violence is questionable.<br />

Impact of cameras<br />

The effectiveness of CCTV<br />

monitoring in reducing violence<br />

in hospital wards has yet to be<br />

evaluated fully. Apart from some<br />

localised studies (see for example<br />

Warr et al., 2005) there is very little<br />

research that assesses the impact of<br />

the cameras on patients and<br />

nursing practices. CCTV’s potential<br />

to control and regulate human<br />

behaviour has been a central feature<br />

of surveillance studies. Orwellian<br />

accounts highlight such surveillance<br />

practices through the maintenance<br />

of hierarchical social control, whilst<br />

Foucauldian analysis draws on<br />

Bentham’s model of the panoptican<br />

to identify disciplinary aspect of<br />

surveillance in the production of<br />

what Foucault (1977) refers to as<br />

‘docile bodies’.<br />

However, these explanations do<br />

not easily sit within mental health<br />

ward settings. For example, the<br />

maintenance of social control within<br />

wards does not simply apply to<br />

patients; frontline staff are also being<br />

watched and this has the potential to<br />

change their interaction with<br />

patients, affecting nursing practices,<br />

not necessarily in a positive way.<br />

Similarly, for patients who are<br />

acutely unwell the panoptic<br />

practices of the cameras will not<br />

affect their behaviour. These patients<br />

are more likely to be violent, and<br />

positive nursing practices are<br />

affected. Staff can feel that they do<br />

not need specific knowledge and<br />

information; for example, what might<br />

trigger a patient’s violence behaviour,<br />

because the cameras provide this<br />

safety measure. Here it is not just the<br />

investment of relationship between<br />

staff and patients that has the<br />

potential to be affected, the diligence<br />

required for certain nursing practices,<br />

such as undertaking comprehensive<br />

and regular patient assessments, also<br />

has the potential to be influenced<br />

negatively. For some patients,<br />

whether they have the capacity to<br />

understand or not, the cameras may<br />

not be perceived as a safety measure<br />

but as punitive, and, together with<br />

other practices on mental health<br />

wards, such as the use of seclusion,<br />

this is also likely to have a negative<br />

influence on their behaviour.<br />

Recovery in mental health<br />

hospitals is based very much on<br />

positive interaction and contact<br />

between staff and patients. CCTV has<br />

the potential for undermining the<br />

intimacy and therapeutic relationship<br />

between ward staff and patients and<br />

in a reduction of face-to-face<br />

contact, resulting in what Lyon<br />

(2001) refers to as ‘disappearing<br />

bodies’. The disembodiment of<br />

patients, created by observing them<br />

through a two-dimensional reality,<br />

coupled with the lack of contact and<br />

social interaction between patients<br />

and staff, has the potential for failing<br />

to see patient behaviour within<br />

context, resulting in the failure to see<br />

the ward environment as a lived in<br />

space.<br />

Benefits and limitations<br />

It is difficult to assess the benefits<br />

and limitations of CCTV surveillance<br />

within ward settings without<br />

extensive research that includes<br />

the views of patients and staff.<br />

An impact study of the cameras<br />

cannot be measured in isolation<br />

and needs to be assessed together<br />

with other surveillance practices<br />

on the ward, such as one-to-one or<br />

close observations of patients. It is<br />

probable that the implementation<br />

of CCTV cameras has not received<br />

significant debate within mental<br />

health services as they are not<br />

perceived to be a ‘therapeutic’ tool<br />

and like patient observations are<br />

seen as way of managing patient<br />

behaviours within wards. However,<br />

the management of insanity is part<br />

of a ‘therapeutic’ process; this is<br />

very evident in the history and rise<br />

of psychiatry as the sole arbitrator in<br />

controlling madness.<br />

Finally, the issue around violence<br />

within mental health hospitals has<br />

been around ever since the<br />

introduction of asylums and hospital<br />

care. The debate around minimising<br />

violence within hospitals needs to<br />

include the voices of both staff and<br />

patients. Currently, expedient<br />

responses based on new public<br />

management have created the<br />

potential for further segregation<br />

between staff and the patients that<br />

they have a caring responsibility<br />

towards. n<br />

Suki Desai is Senior Lecturer at the University<br />

of Gloucestershire. She has previously worked<br />

as regional director with the Mental Health Act<br />

Commission.<br />

References<br />

Desai, S. (2009), ‘The new stars of CCTV:<br />

what is the purpose of monitoring<br />

patients in communal areas of psychiatric<br />

hospital wards, bedrooms and seclusion<br />

rooms?’, Diversity in Health and Care, 6,<br />

pp. 45-53.<br />

Foucault, M. (1977), Discipline and<br />

Punish, <strong>Harm</strong>ondsworth: Penguin.<br />

Gill, M. and Spriggs, A. (2005), Assessing<br />

the Impact of CCTV, Home Office<br />

Research Study 292: Home Office<br />

Research, Development and Statistics<br />

Directorate.<br />

Healthcare Commission and The Royal<br />

College of Psychiatry (2005), National<br />

Audit of Violence 2003-2005, Healthcare<br />

Commission.<br />

Lyon, D. (2001), Surveillance and<br />

Society: Monitoring Everyday Life,<br />

Buckingham: Open University Press.<br />

Warr, J., Page, M. and Crossen-White, H.<br />

(2005), The Appropriate Use of Closed<br />

Circuit Television (CCTV) in Secure Unit,<br />

Bournemouth: Bournemouth University.<br />

cjm no. 83 March 2011 5<br />

rCJM No 83.indd 5 25/02/2011 07:43:04<br />

T O p I C A L I S S u E S A N D C O m m E N T

T O p I C A L I S S u E S A N D C O m m E N T<br />

6<br />

Protecting endangered<br />

species<br />

Jasper Humphreys and M L R Smith discuss<br />

how laws are being undermined in areas of<br />

conflict.<br />

After drugs and guns it is the<br />

illegal trade in wildlife, whether<br />

dead or alive, that generates<br />

the biggest global share of illicit<br />

sales, amounting to $10 billion a<br />

year. However, it has the weakest<br />

enforcement apparatus by a long<br />

way of the ‘big three’ sectors. How<br />

is this so?<br />

While there is a huge raft of<br />

conventions, protocols and<br />

agreements to halt the destruction<br />

of biodiversity and its wildlife, the<br />

underpinning legal mechanism is<br />

essentially powered only by high<br />

hopes and expectations. This is ‘soft<br />

power’ and, from a conservationist<br />

perspective, this lack of enforcement<br />

means that wildlife is wide open to<br />

exploitation and the lack of viable<br />

protection is a death-trap for many<br />

endangered species.<br />

Putting aside environmental<br />

issues such as climate change and<br />

habitat destruction, the conservation<br />

of biodiversity and wildlife is bound<br />

up with some of the thorniest<br />

international legal issues that relate,<br />

on the one hand, to sovereignty,<br />

statehood and security arrangements<br />

while on the other hand are<br />

dominated by the economic forces of<br />

globalisation. What often joins the<br />

two sides is war; as the great Prussian<br />

philosopher of war, Carl von<br />

Clausewitz, famously wrote: ‘war is<br />

an extension of politics by other<br />

means’.<br />

Since the end of the Second<br />

World War there have been an<br />

estimated 160 wars. It is calculated<br />

that during the 1990s there were<br />

three times as many ongoing wars<br />

than any time in the 1950s and twice<br />

as many during the 1960s. The point<br />

here is that the Earth’s areas of richest<br />

biodiversity lie mostly in tropical and<br />

©2011 Centre for Crime and <strong>Justice</strong> Studies<br />

10.1080/09627251.2011.550147<br />

sub-tropical regions of developing<br />

states, many of which have been<br />

affected by conflict at some time or<br />

another. A report by a group of<br />

leading US scientists showed that 80<br />

per cent of the armed conflicts<br />

between 1950 and 2000 took place<br />

in ‘hotspots’, areas deemed to<br />

contain particularly diverse ranges of<br />

threatened species (Hanson et al.,<br />

2009). Even more explicitly, the<br />

incidence of resource-based wars<br />

has been growing steadily; one<br />

United Nations report (2010)<br />

suggests that of the 35 conflicts since<br />

2000, 18 have been about or fuelled<br />

by the exploitation and control of<br />

natural resources, as opposed to wars<br />

Rhinos at risk<br />

fought over issues of ideology and<br />

territorial security. Such wars are less<br />

about clashes of inter-state interests<br />

and more about civil wars within<br />

states, and are particularly prevalent<br />

in Africa.<br />

Even though the process defies<br />

the conventional notion of politics as<br />

some sort of ideological struggle it is<br />

still deeply political and invariably<br />

results in the emergence of a quasistate<br />

apparatus, the influence of<br />

which is often restricted to urban<br />

concentrations, is dominated by<br />

criminal plunder, with limited<br />

jurisdiction over its subjects, and<br />

where the supply of welfare and<br />

social services to the population are<br />

© Melinda Kerrison<br />

all but non-existent. These are<br />

different kinds of wars, and a<br />

different kind of politics drives them.<br />

The participants in resource wars<br />

pursue their political agenda through<br />

violence in order to increase their<br />

power by whatever means necessary<br />

at the expense of time-consuming<br />

state building, using force with<br />

enhanced terror if necessary but<br />

which form new rules and authority.<br />

In other words, ‘the state’ merely<br />

becomes a conduit for booty for<br />

these elite groups. For example, the<br />

Madagascan government of former<br />

disc jockey Andry Rajoelina has<br />

been accused of encouraging the<br />

‘timber mafia’ so that it can reap a<br />

percentage of export tax on<br />

hardwood sales, a policy that has<br />

had disastrous effects on the sensitive<br />

habitats that support the native lemur<br />

population (Smith, 2009).<br />

The predominant intrastate<br />

character of war, involving political<br />

factions and ethnic groups, has<br />

resulted in mass migrations of<br />

refugees. Refugees share a common<br />

need with the military forces that<br />

oppress them, which is to survive off<br />

the land, with devastating effects on<br />

wildlife and wider eco-systems.<br />

During Rwanda’s civil war nearly 50<br />

per cent of the country’s seven<br />

million people were displaced into<br />

camps along the eastern regions of<br />

the Congo. Of these, approximately<br />

860,000 refugees settled around the<br />

Virunga National Park, home of the<br />

Mountain Gorilla, with another<br />

330,000 camped in the Kahuzi Biega<br />

National Park, the only home of the<br />

Grauer’s Gorilla.<br />

Worldwide awareness about<br />

protecting wildlife has moved a long<br />

way since the first conservation<br />

treaty was signed in 1889 to regulate<br />

salmon fishing on the Rhine. One<br />

side of the attempt to arrest the<br />

assault on wildlife resides with ‘soft’<br />

power diplomacy and the threat of<br />

sanctions. The cornerstone of this<br />

approach is the Convention on<br />

International Trade and Endangered<br />

Species of Wild Fauna and Flora<br />

(CITES). Established in 1973 and now<br />

with 175 signatories, CITES aims ‘to<br />

ensure that international trade in<br />

specimens of wild animals and<br />

plants does not threaten their<br />

survival’. While CITES has attempted<br />

rCJM No 83.indd 6 25/02/2011 07:43:05

to construct an international<br />

consensus its weakness is that it<br />

relies solely on the goodwill and<br />

co-operation among signatories and<br />

lacks the means of enforcing<br />

compliance in the face of mounting<br />

and complex threats to animals,<br />

which either did not exist or were<br />

unknown when CITES was originally<br />

established.<br />

The ineffectiveness of<br />

international conventions is<br />

underlined by the fact that while<br />

international law has been applied to<br />

environmental disputes, such as the<br />

Trail Smelter Case between Canada<br />

and the United States in 1938, no<br />

action has been taken against any<br />

actor for wilful environmental<br />

destruction (United Nations, 2006).<br />

With ivory trading at over £1000<br />

per kilo and a rhino horn fetching<br />

£150,000, the illegal wildlife trade<br />

presents high-reward/low-risk<br />

opportunities for poachers, especially<br />

given exceptionally weak<br />

enforcement regimes. Since 1979,<br />

the African elephant population has<br />

fallen from an estimated 1.3 million<br />

to under 400,000 with the decline<br />

most dramatic in the past few years;<br />

for instance, the elephant population<br />

in the Zakouma National Park in<br />

Chad dropped from 4000 in 2006 to<br />

just 600 at the beginning of 2010<br />

(Leake, 2010). Elsewhere, the<br />

number of tigers in India reported<br />

across 23 game reserves registered a<br />

drop from 3,700 in 2002 to 1,400 in<br />

2010; furthermore, it is estimated<br />

that in the wild some 4,200 black<br />

rhinos are left in Africa, along with<br />

only 370 Nepalese rhinos and a<br />

mere 130 surviving Javan rhinos<br />

(Milliken et al., 2009).<br />

With the growing influence of<br />

China in the developing world<br />

comes a heightened scramble for<br />

resources along with different<br />

cultural attitudes to the natural<br />

world. The Chinese policy of offering<br />

soft loans has enabled it to discreetly<br />

‘invade’ the continent, extracting raw<br />

materials on a vast scale to fuel its<br />

burgeoning economy. China’s<br />

involvement in the process of<br />

resource exploitation brings with it<br />

an enticement for local people to<br />

poach and trade wildlife. The<br />

decision by CITES in 2008 to a<br />

limited trade in ivory in response to<br />

Chinese pressure has been blamed<br />

for an increase in poaching in East<br />

and Southern Africa (Eccleston,<br />

2008).<br />

The alternative to ‘soft’ power is<br />

‘hard’ power, being the use or threat<br />

of physical coercion but examples<br />

relating to biodiversity and wildlife<br />

protection are rare and usually spring<br />

from ancillary reasons such as the<br />

need to protect species for the sake<br />

of tourism.<br />

Thus, it is left to the more radical<br />

end of the conservation spectrum to<br />

take up the forceful struggle to<br />

protect animal life such as the<br />

marine conservation group, Sea<br />

Shepherd, whose high-end passive<br />

aggressive confrontations with<br />

Japanese whalers, gains large<br />

audiences via the Whale Wars series<br />

on Animal Planet TV.<br />

Sea Shepherd illustrates an<br />

evolving, and intriguing,<br />

development in international affairs,<br />

which is the capacity for selfgenerating<br />

resistance beyond the<br />

state in support of transnational<br />

laws and norms. Public support for<br />

direct action stems in part, as Sea<br />

Shepherd’s leader Paul Watson<br />

emphasises, because his<br />

organisation’s actions are directed<br />

against illegal whaling and are<br />

aimed at enforcing international<br />

maritime law under the United<br />

Nations World Charter for Nature,<br />

adopted in 1982.<br />

Wildlife forms part of the natural<br />

resource base of the state as codified<br />

in the UN Resolution on Permanent<br />

Sovereignty over Natural Resources<br />

in 1963. The principle of permanent<br />

sovereignty, as enshrined in the<br />

founding United Nations Charter, is<br />

regarded as a basic right of selfdetermination<br />

and provides for<br />

exclusive control of the resources<br />

within state boundaries. However,<br />

the issue of sovereignty becomes<br />

much more fraught in resource rich<br />

areas as wildlife parks and reserves<br />

are themselves often located in areas<br />

containing oil, coltan or diamonds,<br />

as well as timber products.<br />

Though environmental and<br />

conservation issues were not covered<br />

in the original Charter, the General<br />

Assembly and the United Nations<br />

Environmental Programme (UNEP)<br />

has developed a range of important<br />

environmental declarations and<br />

treaties over the last four decades.<br />

The 1992 Rio Declaration<br />

announced that ‘peace, development<br />

and environmental protection are<br />

interdependent and indivisible’. The<br />

then British Prime Minister, John<br />

Major, speaking as president of the<br />

Security Council, declared that<br />

‘non-military sources of instability in<br />

the economic, social, humanitarian<br />

and ecological fields have become<br />

threats to peace and security’.<br />

The quickening decline in<br />

biodiversity and wildlife is forcing<br />

conservationists to think in radical<br />

directions but their task is not being<br />

helped by international law: some<br />

argue that the law itself is as much<br />

the problem as the issues and thus<br />

the world has become upside down,<br />

rather like Alice in Wonderland. n<br />

Jasper Humphreys is Director of External<br />

Affairs of the Marjan Centre for the Study of<br />

Conflict and Conservation, Department of War<br />

Studies, King’s College, University of London.<br />

M L R Smith is Professor of Strategic Theory<br />

in the Department of War Studies, King’s<br />

College, University of London. He is Academic<br />

Director of the Marjan Centre for the Study of<br />

Conflict and Conservation.<br />

References<br />

Eccleston, P. (2008), ‘China allowed to<br />

buy ivory from Africa’, Daily Telegraph,<br />

15 July.<br />

Hanson, T., Brooks, T., Fonseca, G.,<br />

Hoffmann, M., Lamoreux, J., Machlis, G.,<br />

Mittermeir, C., Mittermeir, R. and Pilgrim,<br />

J. (2009), ‘Warfare in biodiversity<br />

hotspots’, Conservation Biology, 23(3),<br />

pp. 578-587.<br />

Leake, J. (2010), ‘SAS veterans to join<br />

new war on poachers’, The Sunday<br />

Times, 21 March.<br />

Milliken, T., Emslie, R.H., Talukdar, B.<br />

(2009), ‘African and Asian Rhinoceroses<br />

– Status, Conservation, and Trade’.<br />

CoP15. CITES Secretariat, Geneva,<br />

Switzerland.<br />

Smith, D. (2009), ‘Madagascar lemurs in<br />

danger from political turmoil and “timber<br />

mafia”’, The Guardian, 19 November.<br />

United Nations (2006), ‘Reports of<br />

International Arbitral Awards’, Trail<br />

smelter case, United States, Canada, 16<br />

April 1938 and 11 March 1941, Vol 11,<br />

pp. 1905-1982.<br />

United Nations (2010), Disasters and<br />

conflicts, United Nations Environment<br />

Programme, www.unep.org/<br />

conflictsanddisasters (accessed<br />

5 November 2010).<br />

cjm no. 83 March 2011 7<br />

rCJM No 83.indd 7 25/02/2011 07:43:05<br />

T O p I C A L I S S u E S A N D C O m m E N T

T O p I C A L I S S u E S A N D C O m m E N T<br />

8<br />

Immigration detention<br />

in Northern Ireland<br />

Robin Wilson reports on the lack of due<br />

process for asylum seekers.<br />

Equality before the law is a<br />

fundamental legal principle. In the<br />

context of globalisation, it becomes<br />

even more so: in a world of moving<br />

people, individuals who are not<br />

citizens of the state in which they<br />

find themselves – women trafficked<br />

in the sex trade, for example – may<br />

otherwise fall into a legal black<br />

hole. Yet, when it comes to those<br />

seeking asylum in the UK, a system<br />

of shadow law has developed in<br />

recent years, to which normal rules<br />

of natural justice do not apply.<br />

This legal erosion has followed from<br />

the ascendancy of a political and<br />

official discourse which has elided<br />

policy on immigration and asylum<br />

– even though one is discretionary<br />

(outside of the EU context) while the<br />

other is founded on mandatory state<br />

obligations – and is administratively<br />

embodied in the establishment of<br />

the UK Borders Agency (UKBA) to<br />

‘control’ both. Alongside this has<br />

been the routine prefacing in the<br />

popular media of the word ‘asylumseeker’<br />

with the adjective ‘bogus’.<br />

Together, these have had a<br />

dehumanising effect. Rather than the<br />

individual refugee evoking a reaction<br />

of empathy and hospitality from the<br />

public, a disposition of official<br />

suspicion and mistrust has been<br />

projected on to this stigmatised<br />

‘other’.<br />

Sepia image<br />

Its most extreme manifestation is the<br />

UKBA’s estate of 11 ‘immigration<br />

removal centres’, its size unparalleled<br />

in Europe. Here, asylum-seekers<br />

who have sought refuge in the UK<br />

– often based on a sepia image of<br />

the country as a beacon of human<br />

rights – may find themselves subject<br />

to indefinite administrative detention<br />

with no automatic judicial oversight,<br />

©2011 Centre for Crime and <strong>Justice</strong> Studies<br />

10.1080/09627251.2011.550148<br />

as the Commissioner for Human<br />

Rights of the Council of Europe,<br />

Thomas Hammerberg, complained in<br />

a memo (Commissioner for Human<br />

Rights, 2008) following a visit to the<br />

centres.<br />

Hammerberg<br />

Mr Hammerberg called on the UK<br />

authorities to consider ‘drastically<br />

limiting’ resort<br />

to detention and<br />

he ‘strongly’<br />

recommended<br />

a time limit, as<br />

in France and<br />

elsewhere. His<br />

memo urged onsite,<br />

expert legal<br />

advice, so that<br />

bail might easily<br />

be sought, and<br />

said detention<br />

of children<br />

should cease. In<br />

July 2010, the<br />

Deputy Prime Minister, Nick Clegg,<br />

announced that the family wing of<br />

Yarl’s Wood in Bedfordshire was to<br />

close.<br />

These concerns were echoed in a<br />

report from the Northern Ireland<br />

Human Rights Commission. This<br />

stressed that detention should be a<br />

last resort, subject to judicial<br />

oversight and a time limit. It called<br />

on the UK government to ‘challenge<br />

myths, stereotypes and xenophobic<br />

sentiments articulated in the media<br />

and by others around immigration<br />

and asylum, by consistently stating<br />

the benefits of migration and its<br />

duties in relation to people seeking<br />

asylum’ (Latif and Martynowicz,<br />

2009).<br />

Human stories<br />

In June 2010, a report was launched<br />

at Stormont in Belfast which told<br />

Feeling one is being<br />

labelled, and perceived,<br />

as a criminal or even<br />

terrorist – particularly<br />

if one has a non-white<br />

skin colour – is a deeply<br />

hurtful stigma.<br />

eight human stories of individuals<br />

who had arrived in that part of the<br />

UK – from various African countries<br />

and Iraq, Turkey and Bangladesh<br />

– but had found themselves in<br />

detention, mostly at the Dungavel<br />

centre in Scotland (Refugee Action<br />

Group, 2010). The report, which I<br />

had been commissioned to research,<br />

opened a window on a world not<br />

only obscured from the public gaze<br />

but also largely privatised: Dungavel,<br />

like seven of the other removal<br />

centres, is run by a private company,<br />

which also manages transport to and<br />

from it.<br />

Many aspects of these narratives<br />

are deeply disturbing. First, there is<br />

the sheer arbitrariness of the process.<br />

Individual asylum-seekers who have<br />

been complying with requirements<br />

to report weekly to the police have<br />

found themselves<br />

suddenly<br />

detained by<br />

immigration<br />

officers when<br />

they report or<br />

when large<br />

numbers of Police<br />

Service of<br />

Northern Ireland<br />

and UKBA<br />

personnel come<br />

to their home in a<br />

dawn raid. Others<br />

who have been<br />

travelling across<br />

the Irish Sea, in either direction, have<br />

found themselves victims of a kind of<br />

internal immigration control, linked<br />

to a little-known arrangement known<br />

as Operation Gull.<br />

Humiliation<br />

Second, there is the<br />

disproportionality involved. A<br />

particular humiliation visited upon<br />

a number of the individuals in<br />

this report was being handcuffed<br />

as they were led on to, and off,<br />

the ferry to Scotland, in front of<br />

other passengers. Feeling one is<br />

being labelled, and perceived,<br />

as a criminal or even terrorist –<br />

particularly if one has a non-white<br />

skin colour – is a deeply hurtful<br />

stigma.<br />

Third, there is the lack of<br />

accountability and due process.<br />

Again, these narratives tell of being<br />

rCJM No 83.indd 8 25/02/2011 07:43:05

Case study: Jamiu<br />

Jamiu was a Nigerian citizen studying in London, who visited<br />

Belfast for the christening of a friend’s baby girl. He said:<br />

‘Instead of spending eight lovely days in Belfast I spent ten<br />

days detained in an airport, a police cell, and a detention<br />

centre for illegal immigrants.’ At Belfast International Airport,<br />

Jamiu was stopped by an immigration officer. He noted that<br />

the only other person taken out of the queue was a black<br />

woman. ‘I was very uncomfortable about this fact as other<br />

people were looking at us.’<br />

Reflecting on the experience which saw him being held in a<br />

detention centre in Scotland prior to his release, Jamiu said:<br />

‘I have never been in any trouble of any kind in my life … No<br />

matter how long I live, this ordeal will be with me for the<br />

rest of my life.’<br />

held in police custody without the<br />

automatic access to a lawyer to<br />

which individuals who have been<br />

suspected of a criminal offence are<br />

rightly entitled.<br />

Finally, there is a general sense of<br />

bewilderment as to what is going on.<br />

Individuals are held for days, weeks<br />

or even months with no idea how<br />

long this process will last. They are<br />

moved from one centre to another at<br />

very short notice. Even release may<br />

come like a bolt from the blue.<br />

The report, which was<br />

commissioned by the Refugee Action<br />

Group, a<br />

network of<br />

relevant NGOs<br />

in Northern<br />

Ireland, surveyed<br />

evidence of good<br />

practice in<br />

Scotland,<br />

Sweden and<br />

Australia before<br />

recommending<br />

what a 2006<br />

paper on<br />

alternatives to<br />

detention for an<br />

all-party<br />

Westminster<br />

group (Bercow et<br />

al., 2006) called ‘a supportive<br />

casework approach’ of ‘communitybased<br />

support and welfare, rather<br />

than punishment’.<br />

Specifically, it recommended:<br />

. . . there is a general<br />

sense of bewilderment<br />

as to what is going on.<br />

Individuals are held for<br />

days, weeks or even<br />

months with no idea<br />

how long this process<br />

will last.<br />

• the Northern Ireland Executive<br />

should follow Scotland in<br />

adopting an ‘integration from day<br />

one’ approach to all newcomers<br />

to the region;<br />

• a small reception unit should<br />

be established to assess the<br />

complex needs of asylumseekers,<br />

particularly in terms of<br />

legal representation, health and<br />

support, accommodating them<br />

while this assessment is made;<br />

and<br />

• a contract should be secured<br />

with a specialist third-sector<br />

organisation<br />

(or consortium)<br />

which would<br />

offer wrap-around<br />

support to asylumseekers,<br />

including<br />

accommodation<br />

in dedicated<br />

housingassociation<br />

property, centred<br />

on an<br />

individual<br />

caseworker<br />

with whom<br />

each asylumseeker<br />

would be<br />

required regularly<br />

to engage until given leave to<br />

remain or removed.<br />

These recommendations, equally<br />

applicable elsewhere, would seek<br />

to rehumanise and individualise<br />

members of a group subjected<br />

to a pejorative collective label.<br />

Barbara Muldoon is a solicitor in<br />

Belfast who has handled many<br />

asylum and immigration cases<br />

and she encapsulated the issue<br />

in these terms: ‘This,’ she said, ‘is<br />

transformative of people’s lives.’ n<br />

Dr Robin Wilson is an experienced policy<br />

analyst who works with public bodies and<br />

non-governmental organisations, with<br />

intellectuals and practitioners.<br />

References<br />

Bercow, J., Lord Dubs and Harris, E.<br />

(2006), Alternatives to Immigration<br />

Detention of Families and Children,<br />

discussion paper for all-party<br />

parliamentary groups on children and<br />

refugees, www.biduk.org/pdf/res_reports/<br />

alternatives_to_detention_july_2006.pdf<br />

(accessed 27 January 2011).<br />

Commissioner for Human Rights (2008),<br />

Memorandum by Thomas Hammerberg,<br />

Commissioner for Human Rights of the<br />

Council of Europe, following his visits to<br />

the United Kingdom on 5-8 February, 31<br />

March and 2 April 2008. https://wcd.coe.<br />

int/ViewDoc.jsp?id=1339037&Site=<br />

CommDH&BackColorInternet=<br />

FEC65B&BackColorIntranet=FEC65B&<br />

BackColorLogged=FFC679 (accessed 27<br />

January 2011).<br />

Latif, N. and Martynowicz, A. (2009),<br />

Our Hidden Borders: The UK Border<br />

Agency’s Powers of Detention, Belfast:<br />

Northern Ireland Human Rights<br />

Commission, www.nihrc.org/dms/data/<br />

NIHRC/attachments/dd/files/109/Our_<br />

Hidden_Borders_immigration_report_<br />

(April_2009).pdf (accessed 27 January<br />

2011).<br />

Refugee Action Group (2010), Distant<br />

Voices, Shaken Lives: Human Stories of<br />

Immigration Detention from Northern<br />

Ireland, www.refugeeactiongroup.com/<br />

download?id=MTg= (accessed 27<br />

January 2011).<br />

cjm no. 83 March 2011 9<br />

rCJM No 83.indd 9 25/02/2011 07:43:06<br />

T O p I C A L I S S u E S A N D C O m m E N T

T O p I C A L I S S u E S A N D C O m m E N T<br />

A lesson in how not to<br />

spy on your community?<br />

In Birmingham the impact of<br />

counter-terrorism legislation<br />

and its operation on the Muslim<br />

community has led to a community<br />

that does not trust the police force.<br />

The West Midlands Police force<br />

was so concerned with the terrorist<br />

threat that it decided to install<br />

secret covert and overt cameras.<br />

The thinking surely was that the<br />

police could use these cameras to<br />

spy upon a community and help<br />

prevent another 7/7.<br />

The fact Washwood Heath and<br />

Sparkbrook are predominately<br />

Muslim areas means fundamentally<br />

that the police thought the fight<br />

against Al-Qaeda had now reached<br />

the streets of Birmingham. Yet it<br />

appears the cameras have had a<br />

counter-productive effect, further<br />

fuelling the risk that some members<br />

of the local community may now<br />

turn to extremism with the initiative,<br />

known as Project Champion,<br />

becoming a key part in terrorist<br />

propaganda. Many questions<br />

remain unanswered. For example,<br />

what will be the long-term impact of<br />

this event on the Muslim families?<br />

Will it lead to a community<br />

becoming isolated from wider British<br />

society? Has it had the result of<br />

radicalising those concerned, leading<br />

to extremism within this local<br />

community?<br />

Between September 2001 and<br />

March 2008, there were over 1,500<br />

people arrested under counterterrorism<br />

legislation, a third were<br />

charged but only one in eight people<br />

convicted (Home Office, 2009). This<br />

has led to claims within these<br />

communities that the police tactics<br />

10<br />

Imran Awan discusses how the balance<br />

between security and intrusion has<br />

undermined community relations.<br />

©2011 Centre for Crime and <strong>Justice</strong> Studies<br />

10.1080/09627251.2011.550149<br />

are both heavy handed and counterproductive.<br />

With a number of high profile<br />

police raids in Birmingham since the<br />

creation of counter-terrorist laws,<br />

there is a sentiment of distrust and<br />

resentment. The fear is that this could<br />

pave the way for further extremism<br />

within these communities. For<br />

example, since ‘Operation Gamble’<br />

which involved a series of police<br />

raids in 2007 in the Alum Rock area<br />

of Birmingham, aimed at foiling a<br />

terrorist plot to behead a British<br />

Muslim soldier (Guardian Press<br />

Association, 2008), the local<br />

community feels their reputation has<br />

been tarnished and believe they are<br />

perceived as supporting, condoning<br />

and nurturing terrorism.<br />

Spying on the community?<br />

The previous government had<br />

stated that the strategic key was<br />

‘winning hearts and minds’.<br />

Enlisting the support of these local<br />

communities is crucial in the fight<br />

against extremism. However these<br />

raids, and the subsequent CCTV<br />

surveillance, have caused further<br />

damage as the community has a<br />

deep mistrust of the police and<br />

counter-terrorism legislation.<br />

Photo courtesy of Melinda Kerrison<br />

Although these specific areas<br />

have had a high rate of people<br />

charged with terrorist offences, for<br />

example in Small Heath, Alum Rock,<br />

Sparkbrook and the wider area of the<br />

West Midlands, this can in itself not<br />

justify the disproportionate use of<br />

such surveillance. There was a real<br />

opportunity for West Midlands Police<br />

to engage and promote a mutual<br />

understanding after 7/7 and develop<br />

the West Midlands as a place of<br />

understanding and tolerance.<br />

However, that opportunity was lost<br />

when the police forgot their role as<br />

custodians for justice and instead<br />

became the villains of peace.<br />

There is no single pathway to<br />

extremism; instead there are factors<br />

from socio-ethnic to cultural reasons.<br />

One key factor is ideology enshrined<br />

in political grievances and a<br />

mistaken understanding of Islam.<br />

However, the CCTV cameras<br />

installed in Sparkbrook and<br />

Washwood Heath will mean there is<br />

now a grave fear that some Muslim<br />

youth may turn to extremism<br />

because of anger, alienation and<br />

dissatisfaction from British society.<br />

Under Project Champion<br />

(working with Safer Birmingham<br />

Partnership, Birmingham City<br />

Council and other agencies), the<br />

areas were to be monitored by a<br />

network of 218 cameras, including<br />

72 hidden ones. The cameras were<br />

put up, it was claimed, to tackle all<br />

forms of crime, predominately in<br />

Muslim suburbs in the Washwood<br />

Heath and Sparkbrook area. The<br />

Muslim people in this community<br />

come from a culture where they do<br />

not like to complain, and they do not<br />

have any expectations that things<br />

should be better with policing. This is<br />

precisely why critics argue that West<br />

Midlands Police targeted this<br />

community because of its<br />

vulnerabilities (how wrong they<br />

were!). All this has achieved is to<br />

further alienate a community already<br />

antagonised by the Government’s<br />

‘Prevent’ strategy.’<br />

The covert cameras formed what<br />

is known as a ‘ring of steel’, which<br />

means local residents’ every move<br />

was being tracked. There was no<br />

formal consultation over the scheme,<br />

and local councillors who were<br />

briefed about the cameras said they<br />

rCJM No 83.indd 10 25/02/2011 07:43:07

were deceived into believing they<br />

were to tackle anti-social behaviour.<br />

The cameras in actual fact were paid<br />

for by the Terrorism and Allied<br />

<strong>Matters</strong> fund, administered by the<br />

Association of Chief Police Officers.<br />

It has long been argued that<br />

CCTV surveillance is an infringement<br />

of privacy and civil liberty, but by the<br />

same token is a key tool in tackling<br />

the fear crime. At the same time<br />

serious questions have been raised<br />

about CCTV’s effectiveness in<br />

preventing serious crime (Gill and<br />

Spriggs, 2005). Moreover, it has been<br />

argued that CCTV could fall foul of<br />

simply targeting a specific<br />

community disproportionately<br />

resulting in a clear breach of privacy<br />

laws (Scarman Centre, 2005).<br />

Project Champion has been<br />

abandoned for now but the cameras<br />

remain – with bags over them – and<br />

have left a dark cloud hanging over<br />

local residents who feel they have<br />

been unfairly targeted. A recent<br />

damning report of the project,<br />

conducted by Sarah Thornton, Chief<br />

Constable of Thames Valley Police,<br />

revealed how members of the police<br />

force operated in what can only be<br />

described as mafia style policing. The<br />

report highlights how there was a<br />

‘storyline’ and a baseless ‘narrative’<br />

in order to conceal the real truth<br />

behind the cameras (Thornton,<br />

2010). The report makes a point in<br />

arguing that police officers had<br />

‘misled’ the local community and<br />

local community leaders on the true<br />

nature of the use of these cameras.<br />

What is even more worrying is that<br />

West Midlands Police failed to<br />

comply with CCTV Regulation of<br />

Investigatory Powers Act 2000 and<br />

the legal regulatory framework<br />

(Thornton, 2010).<br />

It was clear the cameras were<br />

there for much more than fighting<br />

crime or anti-social behaviour, as<br />

was initially suggested, and were<br />

used as a mechanism to spy on the<br />

Muslim community. West Midlands<br />

Police have had to publicly apologise<br />

for getting it ‘badly wrong’ (The<br />

Telegraph, 2010), but the lasting<br />

damage they have caused between<br />

community relations has made<br />

gathering intelligence for the police<br />

even more problematic than ever<br />

before.<br />

With the police force now facing<br />

a possible legal challenge under the<br />

European Convention on Human<br />

Rights, there is a real sense that there<br />

is still more litigation on the way.<br />

Although there is a public review<br />

currently under way, the Chief<br />

Constable of West Midlands Police<br />

has stated his desire to remove the<br />

cameras; however I would argue that<br />

police will continue to use the<br />

cameras in another form, namely for<br />

tackling normal crime.<br />

Amidst the storm of controversy<br />

surrounding the CCTV cameras, West<br />

Midlands Police have further<br />

exacerbated the potential for ethnic<br />

bias against the Muslim community<br />

through the use of gunshot location<br />

technology. The technology, known<br />

as Shot Spotter, is used to prevent<br />

gun-related crime and has been<br />

successful across the United States,<br />

but the pilot scheme (Project Safe<br />

and Sound) now being run in<br />

Birmingham could have wider<br />

reverberations across the city for<br />

community relations. The system has<br />

acoustic sensors that, over an area of<br />

25 miles, can locate gunfire and then<br />

use audio information and video to<br />

capture a suspect or the scene of the<br />

crime. The technology will collect<br />

information and actual recording<br />

clips, which are dispatched to<br />

communication centres and the local<br />

police force.<br />

There is once again a perception<br />

that the police are unfairly targeting<br />

the Muslim community as they did<br />

with the CCTV debacle, leaving<br />

many questions unanswered. For<br />

example, where will the sensors be<br />

deployed? What do they look like?<br />

And more crucially this time, will the<br />

police consult with the Muslim<br />

community about their views? Critics<br />

argue the technology (which costs<br />

over £150,000) is another attempt by<br />

the state to spy on ‘innocent’<br />

communities who may not be<br />

involved in gun-related crime but<br />

caught up by Birmingham’s war zone<br />

image. The problem for West<br />

Midlands Police is managing two<br />

polarising views; on the one hand<br />

the technology is being used to<br />

prevent a serious crime and, on the<br />

other hand, the scheme will<br />

stigmatise a community as the<br />

technology will be deployed in<br />

predominately Muslim areas<br />

(namely, Aston and Handsworth).<br />

Building trust is the only way to<br />

win hearts and minds but the<br />

cameras have only caused more<br />

damage to a fragile relationship.<br />

West Midlands Police now have the<br />

unenviable task of trying to restore<br />

the community’s trust. The police<br />

must now repair some of that<br />

damage caused by engaging with<br />

grass roots, and by visiting local<br />

community members and Mosque’s<br />

(considered places of tolerance and<br />

an agent for the community). The<br />

policing pledge in the West Midlands<br />

is in tatters, and in order for the<br />

police to change that perception it<br />

will mean reaching out to thousands<br />

of people, by admitting mistakes<br />

were made, but also building trust<br />

again as this could provide a key tool<br />

in preventing seeds of extremism and<br />

isolation developing as a result of the<br />

‘spycam’ saga. n<br />

Imran Awan is Senior Lecturer at the Centre<br />

for Police Sciences, University of Glamorgan.<br />

References<br />

Gill, M. and Spriggs, A. (2005), ‘Home<br />

Office Research Study 292’, Assessing<br />

the impact of CCTV, London: Home<br />

Office Research, Development and<br />

Statistics Directorate.<br />

Guardian Press Association (2008),<br />

‘Profile: Perviz Khan’, The Guardian,<br />

www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2008/feb/18/<br />

uksecurity3 (accessed 22 November<br />

2010).<br />

Home Office (2009), Statistics on<br />

Terrorism, Arrests and Outcomes, 11<br />

September 2001 to 31 March 2008,<br />

http://rds.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs09/<br />

hosb0409.pdf.<br />

Scarman Centre (2005), The National<br />

Evaluation of CCTV: Early findings on<br />

Scheme implementation, London: Home<br />

Office.<br />

The Telegraph Press Association (2010),<br />

‘Police apologise for putting 200<br />

CCTV cameras in Muslim area’,<br />

www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/<br />

law-and-order/8034999/Policeapologise-for-putting-200-CCTVcameras-in-Muslim-area.html<br />

(accessed<br />

18 October 2010).<br />

Thornton, S. (2010), Project Champion<br />

Review, www.west-midlands.police.uk/<br />

latest-news/docs/Champion_Review_<br />

FINAL_30_09_10.pdf.<br />

cjm no. 83 March 2011 11<br />

rCJM No 83.indd 11 25/02/2011 07:43:07<br />

T O p I C A L I S S u E S A N D C O m m E N T

m Y T H S A N D C R I m I N A L J u S T I C E<br />

Gazing into the carnival mirror<br />

The 2003 Oxford Dictionary of<br />

English describes a myth as ‘a widely<br />

held but false belief or idea’. The<br />

authors in this issue of cjm challenge<br />

a series of criminal justice myths<br />

including what ‘crime’ is, how much<br />

is out there, who the ‘criminals’ are,<br />

and the claimed neutrality of the<br />

criminal justice system.<br />

Jeffrey Reiman in his book, The<br />

Rich Get Richer and the Poor Get<br />

Prison (2007) eloquently describes<br />

criminal justice as offering a ‘carnival<br />

mirror’ image of reality.<br />

12<br />

The hall of mirrors:<br />

criminal justice myths<br />

uncovered<br />

Rebecca Roberts considers the<br />

distortions and myths described in the<br />

themed section of cjm.<br />

First we are led to believe that the<br />

criminal justice system is<br />

protecting us against the gravest<br />

threats to our well-being when, in<br />

fact, the system is protecting us<br />

against only some threats and not<br />

necessarily the gravest ones ...<br />

The second deception is ... if<br />

people believe the carnival mirror<br />

is a true mirror ... they come to<br />

believe that whatever is the target<br />

of the criminal justice system<br />

must be the greatest threat to<br />

their well-being.<br />

(Reiman, 2007)<br />

In the following articles we<br />

travel down the hall of mirrors<br />

to consider the distortions and<br />

misrepresentations that occur in<br />

popular debates about criminal<br />

justice. The repetition and<br />

propagation of these myths result<br />

in their emergence as ‘common<br />

sense’ thinking. While they may<br />

on occasion be accidental in their<br />

creation, these myths become<br />

significant in justifying biased,<br />

discriminatory and harmful practices<br />

within criminal justice.<br />

©2011 Centre for Crime and <strong>Justice</strong> Studies<br />

10.1080/09627251.2010.525907<br />

Common sense myths<br />

<strong>Criminal</strong> justice ‘common sense’<br />

offers a set of simplistic yet often<br />

misguided justifications for the<br />

existence and expansion of criminal<br />

justice. A good example is the<br />

recent policy offering by Louise<br />

Casey, Commissioner for Victims<br />

and Witnesses, the common sense<br />

being, according to Casey, that fewer<br />

people should have the right to a<br />

jury trial, which she describes as ‘a<br />

sacred cow’ citing an unreferenced<br />

case from her local paper of a trial<br />

over the theft of tea bags and biscuits<br />

worth £24. When challenged at a<br />

parliamentary hearing Casey argued<br />

‘The evidence base is common<br />

sense, Chairman’ to which the Chair<br />

of the <strong>Justice</strong> Committee Sir Alan<br />

Beith retorted ‘There is common<br />

sense and there is evidence. They<br />

are not the same thing.’ Casey’s<br />

use of tea bag and biscuit theft in a<br />

policy document was deliberate and<br />

designed for media release and is a<br />

classic myth creator – it will soon be<br />

common sense that too many tea bag<br />

and biscuit trials are reaching the<br />

crown court.<br />

This exchange at the heart of<br />

goverment underscores the<br />

continuing need for critical thinkers<br />

to challenge the myth-laden version<br />

of criminal justice – it is not simply a<br />

polite academic exchange of views<br />

that is taking place – matters of<br />

principle are at stake.<br />

Myth busting<br />

Myth busting in criminal justice is<br />

about unpacking the ways in which<br />

the public are misled in terms of<br />

what and who is harmful in society.<br />

By accepting the claim that the<br />

criminal justice system is based on<br />

impartiality, fairness and equality<br />

attention is thus focused on making it<br />

more fair and more equal at the cost<br />

of failing to draw attention to how as<br />

an institution, these assumptions and<br />

goals are inherently problematic.<br />

Pioneers in the field of myth<br />

busting are Pepinsky and Jesilow,<br />

who in 1984 published The Myths<br />

that Cause Crime highlighting a<br />

series of ten myths:<br />

Myth 1: Crime is increasing<br />

Myth 2: Most crime is<br />

committed by the poor<br />

Myth 3: Some groups are more<br />

law abiding than others<br />

Myth 4: White collar crime is<br />

nonviolent<br />

Myth 5: Regulatory agencies<br />

prevent white-collar<br />

crime<br />

Myth 6: Rich and poor are equal<br />

before the law<br />

Myth 7: Drug addiction causes<br />

crime<br />

Myth 8: Community corrections<br />

is a viable alternative<br />

Myth 9: The punishment can fit<br />