Vol. XXI - University of the Cumberlands

Vol. XXI - University of the Cumberlands

Vol. XXI - University of the Cumberlands

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

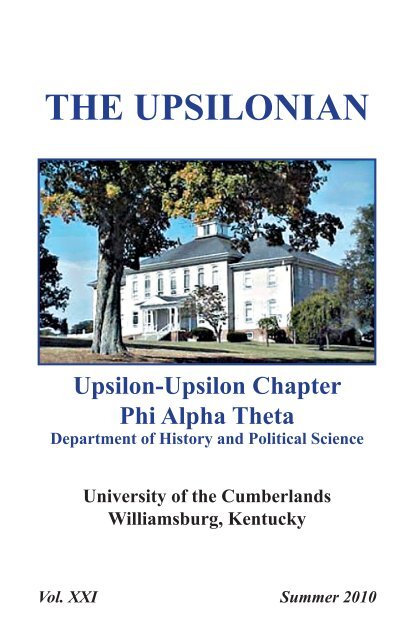

The Upsilonian<br />

Upsilon-Upsilon Chapter<br />

Phi Alpha Theta<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> History and Political Science<br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Cumberlands</strong><br />

Williamsburg, Kentucky<br />

<strong>Vol</strong>. <strong>XXI</strong> Summer 2010

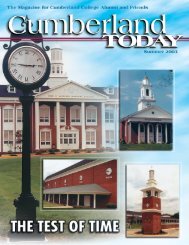

The front cover contains a picture <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Bennett<br />

Building, home <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Upsilon-Upsilon Chapter<br />

<strong>of</strong> Phi Alpha Theta and <strong>the</strong> History and Political<br />

Science Department <strong>of</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Cumberlands</strong>. Built in 1906 as part <strong>of</strong> Highland<br />

College, <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Cumberlands</strong> assumed<br />

ownership in 1907. The building underwent<br />

extensive renovation in 1986-1987.

Journal <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Upsilon-Upsilon Chapter<br />

<strong>of</strong> Phi Alpha Theta<br />

THE UPSILONIAN<br />

Student Editor<br />

Mat<strong>the</strong>w Bro<strong>the</strong>rton<br />

Board <strong>of</strong> Advisors<br />

M.C. Smith, Ph.D., Chairman <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Board <strong>of</strong> Advisors and<br />

Associate Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> History<br />

Oline Carmical, Ph.D., Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> History<br />

Kyla Fitz-Gerald, student member <strong>of</strong> Upsilon-Upsilon<br />

Christina Gillis, student member <strong>of</strong> Upsilon-Upsilon<br />

Bruce Hicks, Ph.D., Associate Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Political Science<br />

Christopher Leskiw, Ph.D, Associate Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Political Science<br />

Al Pilant, Ph.D., Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> History

COPYRIGHT © 2010 by <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Cumberlands</strong><br />

Department <strong>of</strong> History and Political Science<br />

All Rights Reserved<br />

Printed in <strong>the</strong> United States <strong>of</strong> America<br />

ii

Table <strong>of</strong> Contents<br />

iv<br />

v<br />

v<br />

vi<br />

Comments from <strong>the</strong> Student Editor... Mat<strong>the</strong>w C. Bro<strong>the</strong>rton<br />

Comments from <strong>the</strong> President.......................... Taylor Bowman<br />

Comments from <strong>the</strong> Advisor..................................Eric L. Wake<br />

The Authors<br />

Articles<br />

1 “Let Not My Sex Be an Objection:” Olympe De Gouges and<br />

<strong>the</strong> French Revolution....................................... Kiersten Friend<br />

11 Angel <strong>of</strong> Assassination: Charlotte Corday and <strong>the</strong> Death <strong>of</strong><br />

Jean-Paul Marat................................................ Taylor Bowman<br />

22 Reflections <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Revolution: A Study <strong>of</strong> Paintings by<br />

Jacques-Louis David .........................................Megan Hensley<br />

iii

Greetings and Salutations:<br />

Comments From The Editor<br />

Virginia Woolf once wrote that “Nothing has really happened until it has been<br />

recorded.” Indeed, it is those few that dedicate <strong>the</strong>ir lives to recording <strong>the</strong> events <strong>of</strong><br />

history that allow us to grasp and understand what has come before. It is because <strong>of</strong><br />

those historians <strong>of</strong> old that we can attempt to avoid <strong>the</strong> mistakes <strong>of</strong> our forefa<strong>the</strong>rs, but<br />

also to learn from <strong>the</strong>m.<br />

The pursuit <strong>of</strong> history and <strong>the</strong> secrets that it holds is one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> hardest goals to<br />

achieve, and as such special thanks and congratulations are due for those who have,<br />

those who are, and those that will try to master this discipline and unlock <strong>the</strong> secrets<br />

that history still holds.<br />

Most special congratulations go to Kiersten Friend, Megan Hensley, and Taylor<br />

Bowman. They are part <strong>of</strong> a new generation <strong>of</strong> historians that will go forth and<br />

continue in <strong>the</strong> best traditions <strong>of</strong> those guardians <strong>of</strong> history. We also thank those<br />

who submitted papers that were not included in this journal. It is my hope that you<br />

continue your pursuit <strong>of</strong> history in <strong>the</strong> future.<br />

Thanks also go out to <strong>the</strong> faculty <strong>of</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Cumberlands</strong>’ Department <strong>of</strong><br />

History and Political Science. Thank you for your time and effort put into reading and<br />

editing <strong>the</strong>se research papers for <strong>the</strong>ir inclusion in The Upsilonian. Special thanks go<br />

to Dr. Eric Wake, chair <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Department and advisor for our Phi Alpha Theta chapter<br />

for his hard work and time working with <strong>the</strong> students and <strong>the</strong>ir papers. Finally, our<br />

sincerest thanks go to Mrs. Fay Partin, secretary <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> History Department. Without<br />

her hard work, this publication would not be possible.<br />

We present this 21st edition <strong>of</strong> The Upsilonian in <strong>the</strong> hope that <strong>the</strong> lessons and<br />

facts contained herein may present to a future generation <strong>the</strong> key to unlocking a future<br />

historical mystery. Happy reading and God bless.<br />

Mat<strong>the</strong>w C. Bro<strong>the</strong>rton<br />

Student Editor, Upsilon-Upsilon<br />

2009-2010<br />

iv

Comments From The President<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r academic year has come and gone and it is time, once again, to publish<br />

The Upsilonian. As one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> authors included in this edition, let me say that it<br />

is an honor to have a paper printed in this volume, and allow me to extend hardy<br />

congratulations to <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r two students who have been granted <strong>the</strong> same privilege.<br />

Their papers are truly exceptional, and I am certain that those who read this journal will<br />

find its contents engaging and enjoyable.<br />

This year has been a good one for <strong>the</strong> Upsilon-Upsilon Chapter. In addition to (and<br />

as a result <strong>of</strong>) our group’s fundraising efforts, three <strong>of</strong> our members were able to attend<br />

<strong>the</strong> Phi Alpha Theta Biennial National Convention in San Diego, California, where we<br />

had a paper presented. Two <strong>of</strong> us were also able to present at <strong>the</strong> Kentucky Regional<br />

Conference, where Kiersten Friend won first place for <strong>the</strong> very paper published in this<br />

edition. We are very proud <strong>of</strong> her. Our group has been blessed with a dedicated faculty<br />

sponsor in Dr. Eric Wake as well as with <strong>the</strong> support <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> entire History and Political<br />

Science Department. I would like to <strong>of</strong>fer a word <strong>of</strong> thanks to Dr. Chuck Smith, who<br />

consistently supplies our chapter’s bake sales and who has been <strong>the</strong> faculty advisor for<br />

this edition, and to Fay Partin, <strong>the</strong> department secretary who has, even now, begun to<br />

piece our Best Chapter application toge<strong>the</strong>r. We are much indebted to you both.<br />

The end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> school year is always a bittersweet affair. On <strong>the</strong> one hand, many <strong>of</strong><br />

us are graduating, moving on to higher levels <strong>of</strong> education or venturing out into <strong>the</strong> real<br />

world to encounter <strong>the</strong> joys and pressures <strong>of</strong> life beyond academia. On <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r, we<br />

are leaving behind many friends and faculty that we have come to respect and cherish,<br />

and <strong>the</strong> Upsilon-Upsilon Chapter is losing several dedicated members. But such is life.<br />

Changes <strong>of</strong> this kind are inevitable, and <strong>the</strong>re is nothing left for me to do as President<br />

except to express, one final time, my gratitude for this year’s Phi Alpha Theta members<br />

and <strong>the</strong> faculty and staff that have seen us through. I appreciate you all and wish each<br />

<strong>of</strong> you <strong>the</strong> best in your future endeavors.<br />

Taylor Bowman, President<br />

Upsilon-Upsilon, 2009-2010<br />

Comments From The Advisor<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r year has come and gone. It is hard to believe that I have been <strong>the</strong> advisor<br />

<strong>of</strong> this chapter for twenty-five years. The time has been a joyful one for me because<br />

I have had <strong>the</strong> pleasure <strong>of</strong> working with some great individuals many <strong>of</strong> whom I still<br />

hear from every now and <strong>the</strong>n. All <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m have contributed to making Upsilon-<br />

Upsilon one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> more outstanding chapters in Phi Alpha Theta.<br />

This year we have had a core <strong>of</strong> dedicated students who could always be depended<br />

upon to do what needed to be done. We went to <strong>the</strong> national convention in San Diego<br />

and <strong>the</strong> group worked hard in helping to raise <strong>the</strong> money. The Chapter was able to pay<br />

for <strong>the</strong> airplane fare and <strong>the</strong> hotel and food expenses. This event demanded much work,<br />

and I am grateful to all who participated. We even presented a paper which received<br />

some good comments. At <strong>the</strong> regional convention, two <strong>of</strong> our people presented papers<br />

and one, Kiersten Friend, won <strong>the</strong> best undergraduate paper. So <strong>the</strong> conferences were<br />

good to us. As was our lecture series, where attendance was good at each lecture.<br />

The “Health Care Debate” drew around 150 people. Most had around 50 people.<br />

So it was a good year for our attendance.<br />

But <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> year is always a little sad because many who have worked so<br />

hard will graduate and move on into <strong>the</strong>ir adult life. Yet, this is how it should be and<br />

this is what we try to prepare <strong>the</strong>m to do. Remember, however, you are a part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Phi<br />

Alpha Theta tradition and you will always be a part <strong>of</strong> us!<br />

Eric L. Wake, Ph.D<br />

Advisor, Upsilon-Upsilon Chapter<br />

v

Authors<br />

Kiersten Friend was a May 2010<br />

graduate with a major in history and<br />

a minor in Communication Arts. The<br />

original draft <strong>of</strong> her paper was written for<br />

<strong>the</strong> Departmental capstone course.<br />

Taylor Bowman was a May 2010<br />

graduate with majors in History and<br />

English. The original draft <strong>of</strong> his paper<br />

was written for <strong>the</strong> Departmental capstone<br />

course.<br />

Megan Hensley was a May 2010<br />

graduate with a major in history and<br />

minors in Art and French. The original<br />

draft <strong>of</strong> her paper was written for <strong>the</strong><br />

Departmental capstone course.<br />

vi

“LET NOT MY SEX BE AN OBJECTION:”<br />

OLYMPE DE GOUGES AND THE FRENCH REVOLUTION<br />

By Kiersten Friend<br />

The onset <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> French Revolution in 1789 completely changed <strong>the</strong><br />

political culture <strong>of</strong> France. The nation, Paris especially, was steeped in thoughts<br />

<strong>of</strong> liberty. The future seemed to promise a much freer society, where anyone who<br />

wanted to participate in political activities could do so, including women. They<br />

hosted political club meetings and openly discussed <strong>the</strong> activities <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> National<br />

Assembly. 1 Olympe de Gouges was especially active. She firmly believed in<br />

equal rights, and saw <strong>the</strong> Revolution as <strong>the</strong> perfect time to give equal rights to<br />

everyone in France. However, it soon became evident to her that <strong>the</strong> only ones<br />

who would truly benefit from <strong>the</strong> Revolution were men. Olympe de Gouges was<br />

a groundbreaking women’s rights pioneer who refused to be bound by <strong>the</strong> mores<br />

<strong>of</strong> her time and unabashedly wrote what she believed, even though it eventually<br />

led to her death.<br />

De Gouges was very active in <strong>the</strong> Revolution from its beginning until<br />

her death in 1793. She served as a commentator on <strong>the</strong> events occurring in <strong>the</strong><br />

government and among <strong>the</strong> people. 2 From 1784 to 1793 she wrote more than<br />

sixty political pamphlets, a true feat for a woman <strong>of</strong> that time. 3 She was also a<br />

playwright and was able to get four plays staged during <strong>the</strong> Revolution. All <strong>of</strong><br />

her plays somehow related to political issues <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> day. 4 She was obviously<br />

very passionate about what was happening around her.<br />

De Gouges’s desire for women to have <strong>the</strong> same rights as men came<br />

from her own experiences. Born in sou<strong>the</strong>rn France, she was given <strong>the</strong> name<br />

Marie Gouze. She was not born into an aristocratic family, so she did not have<br />

<strong>the</strong> educational opportunities to read <strong>the</strong> works <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> enlightenment. Her fa<strong>the</strong>r<br />

was a butcher, but she and many o<strong>the</strong>rs in <strong>the</strong> community believed that her real<br />

fa<strong>the</strong>r was actually a local nobleman. 5 Whe<strong>the</strong>r this is true or not, de Gouges<br />

certainly believed it. She felt that she was denied a proper education since <strong>the</strong><br />

nobleman never claimed her as one <strong>of</strong> his children. 6<br />

In 1765, Olympe was married to Louis Aubry, a friend <strong>of</strong> her fa<strong>the</strong>r’s<br />

who was much older than she was. This was an arranged marriage that lasted<br />

until Aubry’s death a year later. The marriage did produce one child, a son<br />

named Pierre. 7 In 1767, de Gouges met a wealthy military supplier and left for<br />

Paris with him. However, she never remarried and raised her son alone. Once<br />

in Paris, she changed her name to Olympe de Gouges and began working to<br />

educate herself and her son. She discovered that she was a talented writer and<br />

eventually wrote thirty plays. 8 Her lack <strong>of</strong> education as a child and her forced<br />

marriage caused her to take an interest in <strong>the</strong> welfare <strong>of</strong> all oppressed peoples,<br />

but especially <strong>the</strong> inequality that was shown towards women.<br />

When <strong>the</strong> French Revolution began in 1789, Olympe de Gouges greeted<br />

it with enthusiasm. She saw it as <strong>the</strong> ultimate opportunity for women to achieve<br />

equal rights with men. She used <strong>the</strong> fame that she had achieved from her <strong>the</strong>ater<br />

career to help promote her ideals and interests. 9 When <strong>the</strong> National Assembly<br />

adopted <strong>the</strong> “Declaration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Rights <strong>of</strong> Man and Citizen” in August 1789, de<br />

Gouges believed that <strong>the</strong> term ‘man’ meant universal mankind, not just those<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> male gender. The hopes <strong>of</strong> de Gouges and o<strong>the</strong>r feminists were dashed<br />

1

when prominent assemblyman Abbé Sieyès declared that <strong>the</strong>re were two types<br />

<strong>of</strong> citizens: active and passive. He placed women in <strong>the</strong> passive category, along<br />

with children, beggars, and vagrants. 10<br />

De Gouges did not sit back and accept her status as a passive citizen. She<br />

wrote more pamphlets about <strong>the</strong> debates taking place in <strong>the</strong> National Assembly.<br />

One <strong>of</strong> her favorite topics to discuss was marriage. De Gouges believed that<br />

property should belong to both spouses, not solely <strong>the</strong> husband. 11 In her<br />

pamphlet entitled “Social Contract,” de Gouges outlined a property agreement<br />

that those who wished to be married would have to sign. The agreement stated:<br />

“we wish to make our wealth communal, meanwhile reserving to ourselves <strong>the</strong><br />

right to divide in favor <strong>of</strong> our children or towards those whom we might have a<br />

particular inclination.” 12 This idea was very controversial in a time when all <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> property belonged to <strong>the</strong> husband and was left primarily to <strong>the</strong> eldest son.<br />

De Gouges was also very passionate about helping children and called<br />

for illegitimate children to be recognized by <strong>the</strong>ir fa<strong>the</strong>rs. This was no doubt<br />

because she believed herself to be illegitimate. In “Social Contract,” she<br />

declared that couples need to recognize that “property belongs directly to our<br />

children, from whatever bed <strong>the</strong>y come.” 13 She also said that it should be a<br />

crime for a parent to renounce one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir children. 14 In addition to helping<br />

children, a law like this would also help single mo<strong>the</strong>rs who had been raped or<br />

taken as mistresses. De Gouges was also interested in helping poor children. She<br />

called on wealthy families to adopt poor children so that <strong>the</strong>y might have <strong>the</strong><br />

opportunity to get an education and better <strong>the</strong>mselves. 15<br />

De Gouges did not only comment on issues that held particular interest<br />

for women (marriage and children), but also lent her pen to answering <strong>the</strong><br />

question <strong>of</strong> what to do with <strong>the</strong> monarchy. In 1790, she wrote: “I would sacrifice<br />

nei<strong>the</strong>r my king to my country, nor my country to my king, but I would sacrifice<br />

myself to save <strong>the</strong>m as a single entity, fully convinced that one cannot exist<br />

without <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r.” 16 De Gouges believed that <strong>the</strong> monarchy should be kept<br />

in place, but that it should be a constitutional monarchy. 17 She defended <strong>the</strong><br />

institution <strong>of</strong> a constitutional monarchy until <strong>the</strong> infamous Varennes Flight in<br />

June 1791. 18 However, she did not support <strong>the</strong> killing <strong>of</strong> Louis XVI. Her views<br />

on <strong>the</strong> monarchy would be one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> causes that led to her downfall.<br />

She also argued that women should be allowed to actively participate in<br />

<strong>the</strong> legislative process, both by voting and by being eligible for elected <strong>of</strong>fice. 19<br />

Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, she claimed that “These two powers [executive and legislative],<br />

like man and woman, should be united but equal in force and virtue to make a<br />

good household.” 20 It was very courageous <strong>of</strong> de Gouges to publish her ideas<br />

about government, an area that was traditionally a man’s venue. This action<br />

alone shows that she truly was a groundbreaking pioneer for women’s rights.<br />

In September 1791, de Gouges wrote <strong>the</strong> work that would cement her<br />

status as one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> great early women’s rights advocates, “Declaration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Rights <strong>of</strong> Women and Citizen.” This pamphlet was relatively unknown in her<br />

time, but today it is her most famous work. As <strong>the</strong> title suggests, de Gouges<br />

patterned her pamphlet after <strong>the</strong> 1789 “Declaration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Rights <strong>of</strong> Man.” 21<br />

Basically, <strong>the</strong> only way that de Gouges changed her work from <strong>the</strong> original was<br />

in substituting or adding ‘woman’ to man. 22 This document was revolutionary<br />

2

ecause it was one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> first <strong>of</strong> its kind and it explained why women should be<br />

equal to men in <strong>the</strong> eyes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> law and society.<br />

Like <strong>the</strong> original “Declaration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Rights <strong>of</strong> Man,” de Gouges based<br />

many <strong>of</strong> her views on <strong>the</strong> concept <strong>of</strong> ‘nature.’ The idea <strong>of</strong> ‘nature’ was an<br />

Enlightenment ideal that meant absolute truth and goodness. 23 She refers to<br />

nature in <strong>the</strong> preamble saying that this document is “a solemn declaration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

natural, inalienable, and sacred rights <strong>of</strong> woman.” 24 De Gouges was claiming<br />

that since nature was perfect, and that nature had given women <strong>the</strong> same rights<br />

as men, <strong>the</strong>n women must surely be equal to men. It was a crime to deny anyone<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir natural rights. 25 De Gouges drew heavily from <strong>the</strong> ideology <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> time to<br />

support <strong>the</strong> claims that she put forth in her declaration.<br />

“The Declaration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Rights <strong>of</strong> Woman and Citizen” contains<br />

seventeen articles, or rights, that de Gouges rewrote based on <strong>the</strong> articles in “The<br />

Declaration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Rights <strong>of</strong> Man.” De Gouges adjusted <strong>the</strong>m to state what she<br />

felt women were entitled to have. The first article sums up de Gouges’s beliefs<br />

on equality; “Woman is born free and remains equal to man in rights.” 26 In<br />

September 1791, a statement such as this was ground-breaking. Men <strong>of</strong> various<br />

classes were becoming more equal, but women had been largely left behind by<br />

<strong>the</strong> 1791 Constitution. De Gouges believed that because women had contributed<br />

to <strong>the</strong> Revolution, <strong>the</strong>y had earned <strong>the</strong> same rights as men. 27<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r article dealt with what de Gouges believed about government.<br />

She claimed that its purpose was for “<strong>the</strong> preservation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> natural and<br />

imprescriptable rights <strong>of</strong> woman and man. These rights are liberty, property,<br />

security, and especially <strong>the</strong> resistance to oppression.” 28 Even though this article<br />

is essentially a revision <strong>of</strong> “The Declaration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Rights <strong>of</strong> Man,” de Gouges<br />

clearly did not want a big, powerful government that would oppress its people. 29<br />

She believed that an oppressive government would give rise to inequality, which<br />

was exactly what she was fighting against. According to de Gouges, <strong>the</strong> new<br />

government should be based on <strong>the</strong> principles <strong>of</strong> liberty and equality, and that it<br />

should strive to protect its citizens and <strong>the</strong>ir rights. Her eagerness to comment on<br />

government shows how unconcerned she was with <strong>the</strong> expectations <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> time.<br />

Many women discussed government, but few were willing to publically state<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir views. Her willingness to publish her views shows how pioneering she<br />

really was.<br />

De Gouges very strongly believed in <strong>the</strong> absolute equality <strong>of</strong> men and<br />

women. In article six, she discussed employment; “citizenesses and citizens,<br />

being equal in its [<strong>the</strong> law’s] eyes, should be equally admissible to all public<br />

dignities, <strong>of</strong>fices and employments, according to <strong>the</strong>ir ability, and with no<br />

distinction o<strong>the</strong>r than that <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir virtues and talents.” 30 In this article, de<br />

Gouges states that she believes people should be given jobs based on <strong>the</strong>ir skills<br />

and merits, not because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir gender. The sixth article in de Gouges’s work<br />

was <strong>the</strong> same as <strong>the</strong> sixth article in <strong>the</strong> “Declaration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Rights <strong>of</strong> Man.” 31<br />

Not surprisingly, “The Declaration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Rights <strong>of</strong> Woman and Citizen”<br />

did not go over well when it was published. The press was especially negative<br />

towards it. Most papers viewed de Gouges, and o<strong>the</strong>rs like her, as foolish. 32<br />

Newspapers from both sides <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> spectrum blasted her for it. The Royalist<br />

paper Tableau de Paris called de Gouges and o<strong>the</strong>r feminists a “choir <strong>of</strong> national<br />

virgins just as extravagant as <strong>the</strong>y are ridiculous.” 33 A pro-Revolution paper<br />

3

called Révolutions de Paris said that de Gouges was “just showing <strong>of</strong>f.” 34 De<br />

Gouges’s willingness to state her views did nothing to bolster her popularity<br />

with <strong>the</strong> extremists who were wrangling for control <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Revolution.<br />

Interestingly, <strong>the</strong> part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> “Declaration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Rights <strong>of</strong> Woman and<br />

Citizen” that got de Gouges into <strong>the</strong> most trouble with <strong>the</strong> extreme leftist<br />

groups <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Revolution did not come from her views on women’s rights.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> introduction to <strong>the</strong> document, de Gouges dedicated <strong>the</strong> work to Marie<br />

Antoinette. 35 This decision caused <strong>the</strong> far left clubs to view her as a Royalist. 36<br />

De Gouges, however, hoped that if <strong>the</strong> Queen championed <strong>the</strong> cause <strong>of</strong> women,<br />

it would lend more credibility to <strong>the</strong> movement and possibly make women’s<br />

equal rights a reality.<br />

Marie Antoinette likely never saw de Gouges’s pamphlet. Even though de<br />

Gouges went to great lengths to get her pamphlets into <strong>the</strong> hands <strong>of</strong> government<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficials, very rarely did <strong>the</strong>y actually see <strong>the</strong>m. They were considered to be<br />

‘junk mail’ and were simply discarded. When some did find <strong>the</strong>ir way into <strong>the</strong><br />

legislative chambers, <strong>the</strong>y were typically disregarded. 37 The same was true <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> general populace <strong>of</strong> Paris. De Gouges plastered up posters and distributed<br />

pamphlets all over <strong>the</strong> city, but most people ignored <strong>the</strong>m. Despite her work<br />

being disregarded, de Gouges’s fame continued to grow. 38 Most people in Paris<br />

knew who she was, even if <strong>the</strong>y did not agree with her actions.<br />

After <strong>the</strong> publication <strong>of</strong> “Declaration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Rights <strong>of</strong> Woman and<br />

Citizen,” de Gouges continued to write and speak in favor <strong>of</strong> women’s rights.<br />

Some <strong>of</strong> her ideas actually became law on September 20, 1792, when <strong>the</strong><br />

National Assembly proclaimed equal rights for men and women. The National<br />

Assembly also made it easier for women to obtain divorces and serve as<br />

witnesses in trials. 39 Women did not receive all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> gains that de Gouges had<br />

hoped for, but she viewed it as a step in <strong>the</strong> right direction. Sadly however, <strong>the</strong><br />

strides made by women were completely erased with <strong>the</strong> establishment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Napoleonic Codes in 1804. 40<br />

Aside from women’s rights issues, de Gouges continued to speak her<br />

mind on issues pertaining to <strong>the</strong> government and its leaders. She was especially<br />

leery <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Jacobins. While <strong>the</strong> Legislative Assembly was meeting during 1791-<br />

1792, she frequently referred to <strong>the</strong> Jacobins as a “hideaway for reprobates”<br />

and “a den <strong>of</strong> thieves.” 41 She criticized <strong>the</strong> overthrow <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> monarchy on June<br />

20, 1792 and in <strong>the</strong> autumn <strong>of</strong> 1792 she again criticized <strong>the</strong> Jacobins. 42 Her<br />

criticism <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Jacobins was what really brought her to <strong>the</strong> attention <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

government.<br />

De Gouges’s favorite Jacobins to criticize were Maximilien Robespierre<br />

and Jean-Paul Marat. De Gouges considered Marat to be “a destroyer <strong>of</strong> laws,<br />

mortal enemy <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> order, <strong>of</strong> humanity, and <strong>of</strong> his country.” 43 She also accused<br />

him <strong>of</strong> “living large in a society in which he was both a tyrant and a plague.” 44<br />

De Gouges was even more critical <strong>of</strong> Robespierre and wrote two pamphlets<br />

accusing him <strong>of</strong> seeking to be a dictator. She addressed him directly in those<br />

pamphlets saying, “You tell yourself that you’re <strong>the</strong> unique author <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Revolution, you haven’t been, you are not, you will never be anything o<strong>the</strong>r than<br />

disgrace and execration.” 45 She even suggested that Robespierre meet her at <strong>the</strong><br />

Seine River, because <strong>the</strong>re <strong>the</strong>y could both do a service to <strong>the</strong>ir country: he by<br />

dying and she by giving her life drowning him. 46<br />

4

De Gouges stirred up more trouble for herself in December 1792 when<br />

she <strong>of</strong>fered to defend Louis XVI in his trial. Even though she was no longer an<br />

adamant supporter <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> monarchy, she did not believe that Louis should be<br />

killed. She wrote an impassioned letter to <strong>the</strong> National Convention in December<br />

1792 <strong>of</strong>fering herself to defend Louis in his trial. She even brought feminism<br />

into <strong>the</strong> issue saying, “let not my sex be an objection: that heroism and liberty<br />

may be possessed by women <strong>the</strong> Revolution has shown by more than one<br />

example.” 47 De Gouges had no training as a lawyer, but she so strongly believed<br />

that Louis should be spared she <strong>of</strong>fered to defend him. Most historians agree that<br />

this action sealed her fate more than any o<strong>the</strong>r because it enabled <strong>the</strong> Jacobins to<br />

depict her as a traitor to <strong>the</strong> Revolution, and <strong>the</strong>refore to France.<br />

De Gouges’s arguments in favor <strong>of</strong> sparing Louis’s life were sound<br />

and also very perceptive. She claimed that Louis could not be incriminated<br />

because “his ancestors filled to overflowing <strong>the</strong> cup <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sufferings <strong>of</strong> France;<br />

unhappily <strong>the</strong> cup broke in his hands and all its fragments rebounded upon his<br />

head. I may add that, had it not been for his court’s perversity, he might perhaps<br />

have been a virtuous king.” 48 She also said that since <strong>the</strong>y had stripped him <strong>of</strong><br />

his power, he was no longer a threat. 49 De Gouges even used an example from<br />

history to prove her point: “In <strong>the</strong> eyes <strong>of</strong> posterity <strong>the</strong> English are dishonored<br />

by <strong>the</strong> execution <strong>of</strong> Charles I.” 50 In this statement, she told <strong>the</strong> National<br />

Convention that <strong>the</strong>y would shame <strong>the</strong>ir nation by killing Louis.<br />

Her most insightful comment was “Beheading a king does not kill him.<br />

He lives long after death; he is really only dead when he survives his fall.” 51<br />

This meant that if <strong>the</strong> Convention killed Louis, <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong>y would turn him into a<br />

martyr and he would be a rallying point for all those opposed to <strong>the</strong> Revolution.<br />

De Gouges’s arguments, and <strong>the</strong> fact that it was a woman presenting <strong>the</strong>m,<br />

immensely angered <strong>the</strong> Jacobins and practically ensured that she would be<br />

arrested and executed. The only question remaining was when it would happen.<br />

Despite her impending demise, Olympe de Gouges refused to stop<br />

writing about women’s rights and criticizing <strong>the</strong> government. The Committee<br />

<strong>of</strong> Public Safety finally had her arrested on July 22, 1793. The immediate cause<br />

<strong>of</strong> her arrest was a pamphlet that she had written entitled “The Three Urns, The<br />

Salvation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Fa<strong>the</strong>rland.” In this pamphlet, de Gouges said that argument<br />

over which type <strong>of</strong> government France should have could be decided by letting<br />

<strong>the</strong> people vote on it. She suggested that three urns be set up, one for each type<br />

<strong>of</strong> government (monarchy, republic, federation), and <strong>the</strong> people put <strong>the</strong>ir vote in<br />

<strong>the</strong> urn representing what <strong>the</strong>y chose. 52 Ano<strong>the</strong>r work that was used against her<br />

was a play she was working on which centered around Marie Antoinette and <strong>the</strong><br />

royal family <strong>the</strong> night before <strong>the</strong>y were overthrown. Jacobins used this play as<br />

fur<strong>the</strong>r evidence <strong>of</strong> her supposedly being a royalist. 53<br />

De Gouges’s trial was held on November 1, 1793. She was charged with<br />

publishing “a work contrary to <strong>the</strong> expressed desire <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> entire nation [“The<br />

Three Urns”].” 54 The prosecutors also said that she had “openly provoked civil<br />

war and sought to arm citizens against one ano<strong>the</strong>r” by publishing “The Three<br />

Urns.” They claimed that “There can be no mistaking <strong>the</strong> perfidious intentions<br />

<strong>of</strong> this criminal woman, and her hidden motives, when one observes her in all<br />

<strong>the</strong> works to which, at <strong>the</strong> very least, she lends her name.” 55 Because <strong>of</strong> how<br />

ridiculous <strong>the</strong> charges against de Gouges were, it is obvious that <strong>the</strong> real reasons<br />

5

that de Gouges was even on trial were because <strong>of</strong> her attacks on <strong>the</strong> Jacobin<br />

leaders and her support <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> monarchy.<br />

Most <strong>of</strong> de Gouges’s trial record is filled with accounts <strong>of</strong> her slandering<br />

Robespierre and <strong>the</strong> Jacobin party. On her treatment <strong>of</strong> Robespierre, <strong>the</strong><br />

prosecutors accused de Gouges <strong>of</strong> “spewing forth bile in large doses against <strong>the</strong><br />

warmest friends <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> people, <strong>the</strong>ir most intrepid defender.” 56 It is clear from<br />

this statement that Robespierre had been <strong>of</strong>fended by de Gouges, and that de<br />

Gouges had been writing pamphlets condemning <strong>the</strong> Jacobins and <strong>the</strong>ir goals.<br />

De Gouges’s early support <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> monarchy and her defense <strong>of</strong> Louis’s<br />

life were also used against her. The prosecutors said that “The Three Urns,”<br />

“sees only <strong>the</strong> provocation to <strong>the</strong> reestablishment <strong>of</strong> royalty on <strong>the</strong> part <strong>of</strong> a<br />

woman who, in one <strong>of</strong> her writings, admits that monarchy seems to her to be<br />

<strong>the</strong> government most suited to <strong>the</strong> French spirit.” 57 Her warning about sparing<br />

Louis’s life and <strong>of</strong>fer to serve as his lawyer was also used as evidence against<br />

her. 58<br />

De Gouges was not given a lawyer because <strong>the</strong> court told her she had<br />

“wit enough to defend [herself].” 59 She was found guilty and sentenced to death.<br />

When her sentence was given, de Gouges, in an attempt to buy some extra time<br />

for herself, claimed that she was pregnant and could not be executed. It is not<br />

clear why she said this. She may have hoped that she might see her son, Pierre,<br />

one more time, or at <strong>the</strong> very least hear some news as to his whereabouts. 60<br />

When de Gouges was examined by a doctor from <strong>the</strong> Tribunal, she was found<br />

not to be pregnant and was scheduled to be executed. She was able to write one<br />

last letter, and she addressed it to her son. She told Pierre that “I am a victim <strong>of</strong><br />

my idolatry for <strong>the</strong> fa<strong>the</strong>rland and for <strong>the</strong> people.” 61<br />

De Gouges was guillotined on November 2, 1793. 62 An obituary that<br />

appeared in <strong>the</strong> Moniteur on November 3 said, “Olympe de Gouges, born<br />

with an exalted imagination, believed her delusions were inspired by nature.<br />

She wanted to be a Statesman; it would seem that <strong>the</strong> law has punished this<br />

plotter for having forgotten <strong>the</strong> virtues suitable to her own sex.” 63 De Gouges<br />

had overstepped <strong>the</strong> boundaries for women at that time by publishing so many<br />

works against <strong>the</strong> government and for repeatedly calling for women’s rights. It is<br />

also <strong>of</strong> interest to note that within days <strong>of</strong> de Gouges’s death, ano<strong>the</strong>r feminist,<br />

Madame Roland, was also executed. 64<br />

While de Gouges was imprisoned, <strong>the</strong> National Convention voted to<br />

make women’s clubs illegal. This vote took place on October 29-30. The main<br />

reason given for this decision was that “women are hardly capable <strong>of</strong> l<strong>of</strong>ty<br />

conceptions and serious cogitations.” 65 On November 17, Pierre-Gaspard<br />

Chaumette, a Jacobin leader, denounced a crowd <strong>of</strong> women protestors and all<br />

political activism on <strong>the</strong> part <strong>of</strong> women. He told <strong>the</strong>m that “It is shocking, it is<br />

contrary to all <strong>the</strong> laws <strong>of</strong> nature” for women to want <strong>the</strong> same rights as men.<br />

He said it was <strong>the</strong> same as trying to change one’s sex. He used de Gouges as<br />

an example <strong>of</strong> what would happen to <strong>the</strong>m if <strong>the</strong>y continued; “Remember <strong>the</strong><br />

shameless Olympe de Gouges, who was <strong>the</strong> first to set up women’s clubs, who<br />

abandoned <strong>the</strong> cares <strong>of</strong> her household to involve herself in <strong>the</strong> republic, and<br />

whose head fell under <strong>the</strong> avenging blade <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> laws.” 66 Olympe de Gouges<br />

was executed, not only for her writings, but also because she did not conform to<br />

<strong>the</strong> behavior acceptable for her gender.<br />

6

Olympe de Gouges believed that women should have <strong>the</strong> same rights<br />

as men. She had a flair for writing, and she put that gift to use arguing for her<br />

beliefs. Most <strong>of</strong> her works went unnoticed in her day, but <strong>the</strong>y did garner enough<br />

attention to get her into trouble. She had no reservations about criticizing <strong>the</strong><br />

leadership <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> day, and fearlessly stood up for what she thought was right.<br />

Because <strong>of</strong> her defiant and courageous stance on <strong>the</strong> issues <strong>of</strong> her time, Olympe<br />

de Gouges really was a ground-breaking women’s rights advocate.<br />

7<br />

ENDNOTES<br />

1<br />

Jeremy D. Popkin, A Short History <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> French Revolution, 5th ed. (Upper Saddle River,<br />

NJ: Pearson, 2010), 52.<br />

2<br />

Shirley Elson Roessler, Out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Shadows: Women and Politics in <strong>the</strong> French Revolution,<br />

1789-95. <strong>Vol</strong>. 14 <strong>of</strong> Studies in Modern European History, ed. Frank J. Coppa (1996; repr., New<br />

York: Peter Lang Publishing, 1998), 63.<br />

3<br />

Janie Vanpée, “Performing Justice: The Trials <strong>of</strong> Olympe de Gouges,” Theatre Journal 51,<br />

no. 1 (1999): 50, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25068623 (accessed September 14, 2009).<br />

4<br />

Ibid., 51.<br />

5<br />

Joan Wallach Scott, “French Feminists and <strong>the</strong> Rights <strong>of</strong> Man: Olympe de Gouges’s<br />

Declarations,” History Workshop, no. 28 (Autumn, 1989): 8, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4288921<br />

(accessed September 11, 2009).<br />

6<br />

Sophie Mousset, Women’s Rights and <strong>the</strong> French Revolution: A Biography <strong>of</strong> Olympe de<br />

Gouges, trans. Joy Poirel (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2007), 10-11.<br />

7<br />

Ibid., 16.<br />

8<br />

Ibid., 17-19.<br />

9<br />

Vanpée, “Performing Justice: The Trials <strong>of</strong> Olympe de Gouges,” 50-51.<br />

10<br />

Lisa Beckstrand, Deviant Women <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> French Revolution and <strong>the</strong> Rise <strong>of</strong> Feminism<br />

(Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson <strong>University</strong> Press, 2009), 89.<br />

11<br />

Joan B. Landes, Women and <strong>the</strong> Public Sphere in <strong>the</strong> Age <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> French Revolution<br />

(Ithaca, NY: Cornell <strong>University</strong> Press, 1988), 126.<br />

12<br />

Olympe de Gouges, “Declaration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Rights <strong>of</strong> Women and Citizen & Social Contract,”<br />

September 1791, in <strong>the</strong> Modern History Sourcebook, Fordham, http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/<br />

mod/modsbook.html (accessed September 17, 2009).<br />

13<br />

Ibid.<br />

14<br />

Ibid.<br />

15<br />

Landes, Women and <strong>the</strong> Public Sphere in <strong>the</strong> Age <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> French Revolution, 126.

8<br />

16<br />

Olympe de Gouges, “A Female Writer’s Response to <strong>the</strong> American Champion or a Well–<br />

Known Colonist,” January 18, 1790, Center for Modern History, George Mason <strong>University</strong>,<br />

http://chnm.gmu.edu/revolution/d/344/ (accessed September 17, 2009).<br />

17<br />

Landes, Women and <strong>the</strong> Public Sphere in <strong>the</strong> Age <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> French Revolution, 124.<br />

18<br />

Roessler, Out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Shadows, 64.<br />

19<br />

Ibid., 125.<br />

20<br />

Olympe de Gouges (1791), quoted in Landes, Women in <strong>the</strong> Public Sphere in The French<br />

Revolution, 127.<br />

21<br />

Janie Vanpée, “La Déclaration des Droits de la Femme et de la citoyenne: Olympe de<br />

Gouges’s Re-Writing <strong>of</strong> La Déclaration des Droits de l’homme,” in Literate Women in <strong>the</strong> French<br />

Revolution <strong>of</strong> 1789, ed. Ca<strong>the</strong>rine Montfort-Howard (Birmingham, AL: Summa Publications, 1994), 68.<br />

22<br />

Ibid.<br />

23<br />

Beckstrand, Deviant Women <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> French Revolution and <strong>the</strong> Rise <strong>of</strong> Feminism, 76.<br />

24<br />

Olympe de Gouges, “The Declaration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Rights <strong>of</strong> Woman and Citizen,” September<br />

1791, Center for Modern History, George Mason <strong>University</strong>, http://chnm.gmu.edu/revolution/d/477/<br />

(accessed September 17, 2009).<br />

25<br />

Roessler, Out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Shadows, 66.<br />

26<br />

Olympe de Gouges, “The Declaration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Rights <strong>of</strong> Woman and Citizen,” September 1791.<br />

27<br />

Sarah E. Melzer and Leslie W. Rabine, Rebel Daughters: Women and <strong>the</strong> French<br />

Revolution (Ithaca, NY: Cornell <strong>University</strong> Press, 1992), 236.<br />

28<br />

Olympe de Gouges, “The Declaration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Rights <strong>of</strong> Woman and Citizen,” September 1791.<br />

29<br />

Mousset, Women’s Rights and <strong>the</strong> French Revolution, 67.<br />

30<br />

Olympe de Gouges, “The Declaration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Rights <strong>of</strong> Woman and Citizen,” September 1791.<br />

31<br />

“Declaration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Rights <strong>of</strong> Man and Citizen,” August 27, 1789, in P.M. Jones, The<br />

French Revolution 1789-1804, part <strong>of</strong> Seminar Studies in History (London: Pearson Education, Ltd,<br />

2003), 115.<br />

32<br />

Melzer and Rabine, Rebel Daughters, 235. O<strong>the</strong>r prominent proponents <strong>of</strong> women’s rights<br />

included Madame Roland, Etta Palm d’Aelders, and <strong>the</strong> Marquis de Condorcet. All but d’Aelders<br />

would perish during <strong>the</strong> Reign <strong>of</strong> Terror.<br />

33<br />

Tableau de Paris, July 1792, quoted in Roessler, Out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Shadows, 67.<br />

34<br />

Ibid.<br />

35<br />

Olympe de Gouges, “Declaration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Rights <strong>of</strong> Women,” quoted in Mousset, Women’s<br />

Rights and <strong>the</strong> French Revolution, 63-64.

9<br />

36<br />

Roessler, Out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Shadows, 65.<br />

37<br />

Vanpée, “Performing Justice: The Trials <strong>of</strong> Olympe de Gouges,” 51.<br />

38<br />

David W. Del Testa, Florence Lemoine, & John Strickland, “Olympe de Gouges,” in<br />

Government Leaders, Military Rulers, and Political Activists: Lives and Legacies (Westport, CT:<br />

Greenwood Publishing, 2001), 52. http://www.netlibrary.com/Reader/. Net Library (accessed<br />

September 19, 2009).<br />

39<br />

Mousset, Women’s Rights and <strong>the</strong> French Revolution, 85-86.<br />

40<br />

Jane Abray, “Feminism in <strong>the</strong> French Revolution,” American Historical Review 80, no. 1<br />

(February 1975), 59, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1859051 (accessed November 2, 2009).<br />

41<br />

Olympe de Gouges, 1792, quoted in Roessler, Out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Shadows, 66.<br />

42<br />

Roessler, Out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Shadows, 67.<br />

43<br />

Olympe de Gouges, 1792, quoted in Roessler, Out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Shadows, 67.<br />

44<br />

Ibid.<br />

45<br />

Olympe de Gouges, 1792, quoted in Beckstrand, Deviant Women in <strong>the</strong> French<br />

Revolution, 127.<br />

46<br />

Roessler, Out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Shadows, 67.<br />

47<br />

Olympe de Gouges to National Convention, December 1792, quoted in Winifred Stephens<br />

Whale, Women <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> French Revolution (London: Chapman & Hill, ltd, 1922), 168,<br />

http://www.archive.org/details/cu3194024300109, American Libraries (accessed September 14, 2009).<br />

48<br />

Ibid., 169.<br />

49<br />

Whale, Women <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> French Revolution, 169.<br />

50<br />

Olympe de Gouges to National Convention, December 1792, quoted in Whale, Women <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> French Revolution, 169.<br />

51<br />

Ibid.<br />

52<br />

Vanpée, “Performing Justice: The Trials <strong>of</strong> Olympe de Gouges,” 47.<br />

53<br />

Ibid., 48.<br />

54<br />

“The Trial <strong>of</strong> Olympe de Gouges,” November 1, 1793, in Women in Revolutionary Paris,<br />

1789-1795, ed. Darline Gay Levy, trans. Harriet Branson Applewhite, Mary Durham Johnson<br />

(Urbana, IL: <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Illinois Press, 1981), 255.<br />

55<br />

Ibid.<br />

56<br />

Ibid., 256.<br />

57<br />

Ibid.<br />

58<br />

Ibid.

59<br />

Olympe de Gouges to Citizen Degouges, November 1793, in Last Letters: Prisons and<br />

Prisoners in <strong>the</strong> French Revolution, 1st American edition, ed. Oliver Blanc, trans. Alan Sheridan<br />

(New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1987), 131.<br />

60<br />

Mousset, Women’s Rights and <strong>the</strong> French Revolution, 96.<br />

10<br />

61<br />

Olympe de Gouges to Citizen Degouges, Last Letters, 131.<br />

62<br />

Del Testa, Lemoine, and Strickland, Government Leaders, Military Rulers, and Political<br />

Activists, 52.<br />

63<br />

Moniteur, November 1793, quoted in Mousset, Women’s Rights and <strong>the</strong> French<br />

Revolution, 97.<br />

64<br />

Mary Seidman Trouille, Sexual Politics in <strong>the</strong> Enlightenment: Women Writers Read<br />

Rousseau, part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> SUNY Series, The Margins <strong>of</strong> Literature (Albany, NY: New York State<br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> New York, 1997), 278, http://www.netlibrary.com /Reader, Net Library (accessed<br />

September 18, 2009).<br />

65<br />

“Discussion <strong>of</strong> Women’s Political Clubs and Their Suppression, October 29-30, 1793,”<br />

Center for Modern History, George Mason <strong>University</strong>, http://chnm.gmu.edu/revolution/d/294/<br />

(accessed September 17, 2009).<br />

66<br />

Pierre-Gaspard Chaumette, “Speech at City Hall Denouncing Women’s Political<br />

Activism,” November 17, 1793, Center for Modern History, George Mason <strong>University</strong>,<br />

http://chnm.gmu.edu/revolution/d/489/ (accessed September 17, 2009).

ANGEL OF ASSASSINATION:<br />

CHAROLOTTE CORDAY AND THE DEATH OF JEAN-PAUL MARAT<br />

By Taylor Bowman<br />

On July 13, 1793, Marie-Charlotte de Corday, a young and reportedly<br />

attractive woman from <strong>the</strong> Norman town <strong>of</strong> Caen, drove a large knife through<br />

<strong>the</strong> heart <strong>of</strong> French Revolutionary leader Jean-Paul Marat, killing him almost<br />

instantly. 1 Corday viewed Marat as evil incarnate. To her, he was a devil who<br />

brought to <strong>the</strong> originally beneficent Revolution an atmosphere <strong>of</strong> chaos and<br />

<strong>of</strong> terror. Unless he were destroyed, she thought, all <strong>of</strong> France would erupt in<br />

civil war and be consumed in <strong>the</strong> fires <strong>of</strong> a revolution that had moved too far<br />

beyond its earliest intents. 2 Corday, however, misjudged her victim’s influence.<br />

She assumed that, were he eliminated, <strong>the</strong> Revolution would be undone―terror<br />

would cease immediately, and all threat <strong>of</strong> civil war would abate in a single<br />

moment. This was not <strong>the</strong> case. The Revolution did not expire with Marat, and<br />

<strong>the</strong> National Convention began supporting <strong>the</strong> Reign <strong>of</strong> Terror with renewed<br />

vigor. Corday failed to restore peace to France, but Marat’s death none<strong>the</strong>less<br />

had severe consequences for <strong>the</strong> Revolution. Following <strong>the</strong> assassination, <strong>the</strong><br />

Terror’s harshness made enemies <strong>of</strong> its former allies and streng<strong>the</strong>ned anti-<br />

Revolutionary sentiment until Robespierre and o<strong>the</strong>r leaders were ultimately<br />

removed. 3 While her assassination <strong>of</strong> Marat did not abruptly end <strong>the</strong> Revolution<br />

as she had hoped, Corday’s actions, never<strong>the</strong>less, ignited a chain <strong>of</strong> events that<br />

ultimately occasioned <strong>the</strong> collapse <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Terror.<br />

Charlotte Corday belonged to <strong>the</strong> petite noblesse. When she reached her<br />

adolescence, her fa<strong>the</strong>r sent her to a convent in Caen, where she received an<br />

education befitting a young woman <strong>of</strong> her status. 4 There, she was exposed to<br />

<strong>the</strong> writings <strong>of</strong> various <strong>the</strong>ologians, scholars, and philosophers, including those<br />

<strong>of</strong> Rousseau and <strong>Vol</strong>taire (<strong>the</strong> latter <strong>of</strong> whom was read without <strong>the</strong> knowledge<br />

and against that mandate <strong>of</strong> her instructors). 5 As she began to mature, Corday<br />

developed a fascination with <strong>the</strong> realm <strong>of</strong> politics. Highly idealistic, she was<br />

an early and enthusiastic supporter <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Revolution. While at <strong>the</strong> convent, <strong>the</strong><br />

young woman met and befriended Gustave Doulcet de Pontécoulant, a young<br />

lawyer and politician who would later become an important member <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

National Convention. Toge<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong>y followed <strong>the</strong> events <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Revolution with<br />

unparalleled interest, beginning with <strong>the</strong> fall <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Bastille on July 14, 1789.<br />

It was Doulcet that first informed Corday <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> events set in motion by <strong>the</strong><br />

National Assembly on August 4, and from that time forward, <strong>the</strong> young lady<br />

dreamed <strong>of</strong> a government and society in which The Rights <strong>of</strong> Man would be<br />

made law. 6<br />

Shortly after <strong>the</strong> completion <strong>of</strong> her education, Corday took up residence<br />

with her aunt Madame de Bretteville, a wealthy and well-respected citizen <strong>of</strong><br />

Caen. Though <strong>of</strong>ten praised for her beauty, Corday expressed little desire for <strong>the</strong><br />

attentions <strong>of</strong> men. Her most fervent wish was that she might someday discover<br />

a grandiose means by which to aid both France and humanity. 7 She was an avid<br />

reader <strong>of</strong> political literature, which, as <strong>of</strong> September, 1789, included Marat’s<br />

11

L’ami du Peuple. 8 With this journal, Marat earned <strong>the</strong> title <strong>of</strong> “Friend <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

People,” and in it, Corday first encountered Marat and his brand <strong>of</strong> radicalism.<br />

She disliked <strong>the</strong> <strong>of</strong>ten violent rhetoric <strong>of</strong> Marat and his fellow Jacobins, and her<br />

exposure to his writings marks <strong>the</strong> beginning <strong>of</strong> her disillusionment with <strong>the</strong><br />

Revolution and its leaders. 9<br />

In July, 1790, <strong>the</strong> Civil Constitution <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Clergy was enacted. Riots<br />

erupted throughout rural France, and <strong>the</strong> church was divided. The outrage<br />

with which provincial communities, particularly Caen, reacted to this newlyimplemented<br />

legislation seemed evidence to Corday <strong>of</strong> Parisian abuse and<br />

perversion <strong>of</strong> Revolutionary sentiments. The establishment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Civil<br />

Constitution, to her, revealed <strong>the</strong> extent to which <strong>the</strong> Revolution’s most<br />

prominent figures hindered <strong>the</strong> true spirit <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir pr<strong>of</strong>essed cause. 10 The<br />

deposition <strong>of</strong> King Louis XVI in 1791 resulted from and contributed to <strong>the</strong><br />

chaos that had been brewing in Paris since <strong>the</strong> early moments <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> revolution.<br />

Following <strong>the</strong> royal family’s failed escape attempt and subsequent arrest,<br />

Marat, by <strong>the</strong>n a prominent figure in <strong>the</strong> Legislative Assembly, began calling<br />

for <strong>the</strong> king’s execution. 11 Corday found <strong>the</strong> notion repugnant. In <strong>the</strong> past, she<br />

had refused to toast Louis XVI, and she did not nearly possess <strong>the</strong> same level<br />

<strong>of</strong> Royalist sympathies that is commonly attributed to her. She considered<br />

herself a Republican. Never<strong>the</strong>less, she felt that execution would be far too<br />

extreme and that such a measure would contradict <strong>the</strong> humanist values touted by<br />

Revolutionary leaders. 12 The frequent incendiary speeches made by <strong>the</strong> Jacobins<br />

against <strong>the</strong> king increased tensions in Paris and bolstered Corday’s increasingly<br />

negative opinion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Revolution.<br />

The events <strong>of</strong> 1792 stifled any <strong>of</strong> Corday’s hopes that <strong>the</strong> Revolution<br />

might be redeemed. Between September 2 and September 8, Paris prisons<br />

were overrun by ardent Jacobins and Sans-Culottes, who, convinced that those<br />

being held were potentially dangerous enemies <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Republic, tried and<br />

executed everyone found inside. 13 An article printed in Revolutions de Paris<br />

(a newspaper sympa<strong>the</strong>tic to <strong>the</strong> vigilantes) read, “The people are human, but<br />

without weakness; wherever <strong>the</strong>y detect crime, <strong>the</strong>y throw <strong>the</strong>mselves upon it<br />

without regard for <strong>the</strong> age, sex, or condition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> guilty.” 14 Many observers,<br />

<strong>the</strong>n and hence, have attributed <strong>the</strong> brutal actions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mobs here described<br />

to a panic caused by <strong>the</strong> fall <strong>of</strong> Verdun to <strong>the</strong> advancing forces <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Duke<br />

<strong>of</strong> Brunswick. The <strong>the</strong>ory <strong>of</strong>ten propagated states that, when Parisians heard<br />

<strong>of</strong> Verdun’s surrender, <strong>the</strong>y were alarmed, knowing that <strong>the</strong>re remained no<br />

additional strongholds between <strong>the</strong>ir city and <strong>the</strong> advancing Prussian forces. In<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir supposed fear and rage, <strong>the</strong>y invaded <strong>the</strong> prisons and killed all captives. 15<br />

While <strong>the</strong> fear <strong>of</strong> Brunswick may have motivated some segments <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

population, Corday as well as several members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Legislative Assembly<br />

held Marat responsible for inciting (through his journal and through speeches)<br />

what came to be known as <strong>the</strong> Prison Massacres. 16 The belief was so strong in<br />

<strong>the</strong> minds <strong>of</strong> some Assembly members that he was brought before that body to<br />

give an account <strong>of</strong> his actions. Largely due to <strong>the</strong> backing <strong>of</strong> several prominent<br />

Montagnards, Marat was acquitted, but Corday continued to lay <strong>the</strong> blame for<br />

<strong>the</strong> Prison Massacres squarely on his shoulders. 17 The Revolution had grown<br />

bloody, and she identified Marat as <strong>the</strong> progenitor <strong>of</strong> its pitiless violence. 18<br />

12

By <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> September, <strong>the</strong> National Convention had replaced <strong>the</strong><br />

Legislative Assembly as France’s central government. Shortly <strong>the</strong>reafter, Marat,<br />

a recently elected deputy and member <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Montagnard party, renewed his<br />

call for <strong>the</strong> execution <strong>of</strong> Louis XVI. This time, <strong>the</strong> call did not go unanswered,<br />

and in December <strong>of</strong> 1792, <strong>the</strong> former king’s trial began. Regardless <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

enthusiasm with which he was defended and regardless <strong>of</strong> all attempts made to<br />

have execution eliminated as a form <strong>of</strong> punishment, <strong>the</strong> Convention voted to<br />

behead Louis XVI on January 21, 1793. In spite <strong>of</strong> her previous disillusionment,<br />

Corday could not believe <strong>the</strong> king had been guillotined. Reports indicate that,<br />

despite her disdain for <strong>the</strong> Old Regime, <strong>the</strong> news <strong>of</strong> Louis XVI’s death moved<br />

<strong>the</strong> young woman to tears. She saw <strong>the</strong> execution not only as an affront to<br />

<strong>the</strong> philanthropic ideology <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> early Revolution but as breach <strong>of</strong> authority<br />

committed by <strong>the</strong> Convention. 19 This violation she also attributed principally<br />

to Marat. 20 Corday felt that such misuse <strong>of</strong> power could not go unpunished and<br />

was no longer willing to tolerate <strong>the</strong> abuses <strong>of</strong> Marat and <strong>the</strong> Convention. She<br />

began to contemplate her own ability to end <strong>the</strong> destructive sequence into which<br />

<strong>the</strong> Revolution had fallen, and what transpired in April and June <strong>of</strong> that year set<br />

her on <strong>the</strong> road to assassination. 21<br />

While Corday sat at home in Caen, reading about <strong>the</strong> latest atrocities<br />

committed by <strong>the</strong> Paris Jacobins, Marat was staging a coup. Since <strong>the</strong> Prison<br />

Massacres, he and his fellow Montagnards had been unable to pass <strong>the</strong>ir own<br />

agenda through a Convention dominated by Girondins, members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> largest<br />

party within <strong>the</strong> government. Between May 31, and June 2, 1793, Marat took<br />

<strong>the</strong> first steps toward remedying his predicament. In that three-day period, a<br />

mob <strong>of</strong> Sans-Culottes, organized and incited by Marat, marched on <strong>the</strong> Tuileries<br />

and forcibly evicted 22 Girondin deputies from <strong>the</strong>ir seats in <strong>the</strong> Convention.<br />

Nearly all <strong>of</strong> those removed were leading figures within <strong>the</strong> Gironde, and <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

expulsion meant <strong>the</strong> ascendance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Montagnards to power. Those ousted<br />

were escorted from <strong>the</strong> hall and promptly placed under house arrest. Some<br />

managed to escape, but for those who did not, proscription and prison soon<br />

followed. Imprisonment invariably led to execution. Those who escaped house<br />

arrest, <strong>the</strong>refore, effected a hasty departure from Paris. Many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m made for<br />

Caen. There, Corday, who heard <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> overthrow only two days after it occurred<br />

and who had been a long-time Girondin sympathizer, eagerly awaited <strong>the</strong> arrival<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> refugees. By June 9, several <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> escaped Girondins had reached <strong>the</strong><br />

Norman town, and almost all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m came prepared with stories <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> vile<br />

Marat and <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> abominations committed by <strong>the</strong> Montagnards in <strong>the</strong> name <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Revolution. 22<br />

Corday was an eager audience. Among <strong>the</strong> former deputies <strong>the</strong>n in Caen<br />

were Jerome Pétion, Francois Buzot, and Charles Barbaroux, all <strong>of</strong> whom<br />

were figures she recognized from her extensive reading. She had sympathized<br />

with <strong>the</strong>m from afar and now had <strong>the</strong> immense honor <strong>of</strong> meeting and speaking<br />

with <strong>the</strong>m face to face. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, she detested Marat and never passed on<br />

an opportunity to hear him vilified. In that regard, she was not disappointed.<br />

The Girondins spoke <strong>of</strong> endless evil. They told <strong>the</strong> citizens <strong>of</strong> Caen about<br />

<strong>the</strong> policy <strong>of</strong> Terror that had been enacted following <strong>the</strong> coup and delivered<br />

tales <strong>of</strong> horrendous carnage lately sprung up in Paris. They demonized Marat<br />

considerably and reported that <strong>the</strong> guillotine had already claimed nearly<br />

13

100,000 heads and that <strong>the</strong> “Friend <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> People” had found a cure for his<br />

recently contracted ailments in <strong>the</strong> spilling <strong>of</strong> human blood. 23 Such accounts<br />

were doubtless exaggerated, but <strong>the</strong>y fascinated Corday immeasurably. She<br />

had, by this time, already hated Marat and, in fact, had already given thought<br />

to killing him. For her, <strong>the</strong> expulsion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> elected Girondin leaders from <strong>the</strong><br />

National Convention represented a violation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> people’s sovereignty and<br />

an intolerable assault on <strong>the</strong> noble ideas <strong>of</strong> undiluted liberalism. She despised<br />

Marat, and <strong>the</strong> presence and eloquence <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Girondins fur<strong>the</strong>r cemented<br />

her hatred. 24 In <strong>the</strong> weeks following <strong>the</strong>ir arrival, Corday became convinced<br />

that direct action against <strong>the</strong> Convention was needed. Marat would have to be<br />

eliminated.<br />

While she liked and appreciated <strong>the</strong> Girondins’ powerfully delivered<br />

stories, Corday did not admire <strong>the</strong> impotence with which <strong>the</strong>y opposed <strong>the</strong><br />

sitting government. In fact, it disgusted her. On July 7, 1793, General Wimpffen<br />

ga<strong>the</strong>red a small group <strong>of</strong> Girondin sympathizers and attempted to arrange a<br />

militant gala, complete with speeches, songs, banners, and a parade. The event<br />

was intended to demonstrate solidarity among <strong>the</strong> Girondins and to rally support<br />

behind <strong>the</strong>m. The sparse attendance generated made <strong>the</strong> ga<strong>the</strong>ring a pitiful<br />

spectacle and a failure. It embarrassed and distressed Corday, who had already<br />

begun to realize that her new friends were incapable <strong>of</strong> any but a feeble response<br />

to <strong>the</strong> oppressive Convention. 25 Two days prior to Wimpffen’s attempted rally,<br />

Corday purchased a one-way ticket on a Coach set to leave Caen for Paris on<br />

July 9. She had convinced herself that Marat was <strong>the</strong> source <strong>of</strong> all that had gone<br />

awry with <strong>the</strong> Revolution and that he must be killed to restore order in France. 26<br />

His assassination would be her grandiose gesture for <strong>the</strong> good <strong>of</strong> her country and<br />

for <strong>the</strong> betterment <strong>of</strong> humanity.<br />

Prior to purchasing her ticket, Corday went to see Barbaroux at <strong>the</strong> Hotel<br />

de L’Intendance, introducing herself as Marie-Charlotte de Corday. She secured<br />

from <strong>the</strong> former deputy a letter <strong>of</strong> introduction to Lauze Duperret, a Girondin<br />

deputy who, not having been expelled, remained in <strong>the</strong> Convention and served<br />

as an intermediate between Barbaroux and <strong>the</strong> proscribed Girondins (such as<br />

Madame Rolland) who failed to escape imprisonment. 27 Upon acquiring a seat<br />

on <strong>the</strong> next coach to Paris, Corday returned home and burned all <strong>of</strong> her political<br />

literature, arranged for <strong>the</strong> payment <strong>of</strong> her debts, bequea<strong>the</strong>d her valuable<br />

items to friends and loved ones, and returned all <strong>the</strong> books she had borrowed.<br />

Once her affairs were in order, she made her goodbyes. She told Madame<br />

de Bretteville that she would be going to stay with her fa<strong>the</strong>r in Argentan.<br />

Meanwhile, she wrote a letter to her fa<strong>the</strong>r, explaining that she planned on taking<br />

a trip to England. 28 Thus she traveled to Paris on <strong>the</strong> morning <strong>of</strong> July 9 without<br />

<strong>the</strong> knowledge <strong>of</strong> friends or family.<br />

Corday arrived in Paris on July 12, 1793. She sought out Duperret and<br />

gave him <strong>the</strong> letter <strong>of</strong> introduction she had received from Barbaroux. She wanted<br />

to kill Marat publicly, preferably during a meeting <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Convention, and she<br />

asked Duperret how she would go about gaining entrance into a Convention<br />

session. Duperret seemed willing to arrange for her admittance, but Corday soon<br />

learned that Marat no longer attended Convention meetings. He had, prior to<br />

<strong>the</strong> coup, contracted a debilitating skin condition that had worsened in severity<br />

14

to such an extent that he was forced to remain at home. 29 This discovery<br />

momentarily disappointed Corday, but shortly <strong>the</strong>reafter, she discovered that,<br />

while he was not <strong>the</strong> leader he had been formerly, he remained active and<br />

continued to conduct Convention business despite his lack <strong>of</strong> mobility. 30 Corday<br />

remained convinced that <strong>the</strong> key to peace lay in <strong>the</strong> death <strong>of</strong> Marat, so she<br />

resolved to pay him a visit on <strong>the</strong> following morning and to accomplish her task<br />

at that time.<br />

Corday arose at 6:00 on <strong>the</strong> morning <strong>of</strong> July 13. Her first destination<br />

was <strong>the</strong> Palais Royal, where she intended to purchase <strong>the</strong> tools necessary for<br />

<strong>the</strong> task that lay ahead <strong>of</strong> her. In her zeal, she arrived before any <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> shops<br />

were yet open for business, so she was obliged to wait, which she did with little<br />

patience. When <strong>the</strong> vendors had arrived, Corday began her search. Ultimately,<br />

she purchased her knife from a Monsieur Badin for two francs. Its blade was<br />

six inches in length, and its handle was ebony. The young woman concealed<br />

her purchase in <strong>the</strong> bosom <strong>of</strong> her dress and went to secure a coach. 31 When<br />

she arrived at Marat’s home in <strong>the</strong> Rue des Cordeliers, she was greeted by his<br />

common law wife Simmone Evrard, who turned her away. Corday explained<br />

that she had come to give Marat information about an underground Girondist<br />

movement, but Evrard insisted that <strong>the</strong> Revolutionary leader was in no condition<br />

to receive guests. 32 Nonplussed, Corday retreated, but she returned around 7:30<br />