A Faculty Guide to Academic Advising - NACADA

A Faculty Guide to Academic Advising - NACADA

A Faculty Guide to Academic Advising - NACADA

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

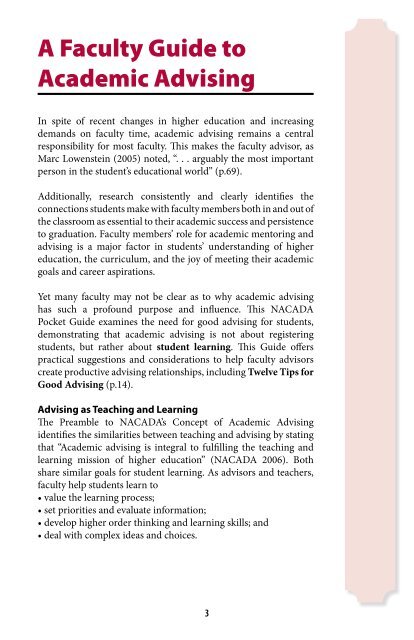

A <strong>Faculty</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> <strong>to</strong><br />

<strong>Academic</strong> <strong>Advising</strong><br />

In spite of recent changes in higher education and increasing<br />

demands on faculty time, academic advising remains a central<br />

responsibility for most faculty. This makes the faculty advisor, as<br />

Marc Lowenstein (2005) noted, “. . . arguably the most important<br />

person in the student’s educational world” (p.69).<br />

Additionally, research consistently and clearly identifies the<br />

connections students make with faculty members both in and out of<br />

the classroom as essential <strong>to</strong> their academic success and persistence<br />

<strong>to</strong> graduation. <strong>Faculty</strong> members’ role for academic men<strong>to</strong>ring and<br />

advising is a major fac<strong>to</strong>r in students’ understanding of higher<br />

education, the curriculum, and the joy of meeting their academic<br />

goals and career aspirations.<br />

Yet many faculty may not be clear as <strong>to</strong> why academic advising<br />

has such a profound purpose and influence. This <strong>NACADA</strong><br />

Pocket <strong>Guide</strong> examines the need for good advising for students,<br />

demonstrating that academic advising is not about registering<br />

students, but rather about student learning. This <strong>Guide</strong> offers<br />

practical suggestions and considerations <strong>to</strong> help faculty advisors<br />

create productive advising relationships, including Twelve Tips for<br />

Good <strong>Advising</strong> (p.14).<br />

<strong>Advising</strong> as Teaching and Learning<br />

The Preamble <strong>to</strong> <strong>NACADA</strong>’s Concept of <strong>Academic</strong> <strong>Advising</strong><br />

identifies the similarities between teaching and advising by stating<br />

that “<strong>Academic</strong> advising is integral <strong>to</strong> fulfilling the teaching and<br />

learning mission of higher education” (<strong>NACADA</strong> 2006). Both<br />

share similar goals for student learning. As advisors and teachers,<br />

faculty help students learn <strong>to</strong><br />

• value the learning process;<br />

• set priorities and evaluate information;<br />

• develop higher order thinking and learning skills; and<br />

• deal with complex ideas and choices.<br />

3

As faculty advisors, we must have a clear sense of purpose about<br />

advising in the same way that we have a clear purpose when<br />

teaching a course. What do we want students <strong>to</strong> learn during<br />

advising discussions Or, in more familiar terms, what should be<br />

the “advising curriculum”<br />

Consider how an advising appointment offers the primary place<br />

in which students can reflect on the meaning of their educational<br />

programs. When unders<strong>to</strong>od in this way, the academic advising<br />

curriculum has the following goals. It<br />

• allows students time <strong>to</strong> think about the meaning of their course<br />

choices;<br />

• helps students make connections between what they are learning<br />

in and beyond the classroom; and<br />

• guides students in learning about the purpose and meaning of<br />

the academic curriculum as well as the academic mission of the<br />

institution.<br />

These curricular goals can be easily linked <strong>to</strong> specific student<br />

learning outcomes critical for student success. We should discuss<br />

with our advisees how advising might teach them <strong>to</strong><br />

• clarify personal values and educational goals;<br />

• guide their decision-making;<br />

• learn how <strong>to</strong> gather needed information systematically; and<br />

• reflect on their strengths and weaknesses and how these affect<br />

their academic plans.<br />

Identifying student learning outcomes for academic advising helps<br />

us focus our discussions with students. For example, advisees<br />

must learn certain types of information, e.g., campus rules and<br />

procedures that will help them build a reasonable schedule that<br />

meets requirements and also satisfies their intellectual interests. A<br />

further learning outcome might be <strong>to</strong> articulate the purpose of their<br />

choices and how these choices meet institutional expectations for<br />

their learning. Making these connections will demonstrate learning<br />

of higher order and reflective thinking skills (Martin 2007).<br />

4

Helping Students Learn<br />

Placing learning at the center of academic advising suggests that<br />

the faculty advisor should organize and create situations that help<br />

students meet specific learning goals. Research in education and<br />

psychology provides insights that can help guide our teaching<br />

strategies in the academic advising experience:<br />

• Students are active learners who draw on their current<br />

understandings and their social context <strong>to</strong> process what they are<br />

learning. This is called the “construction of knowledge.”<br />

• Effective learning strategies are based on knowledge of the<br />

individual learners.<br />

In other words, we should know our students. This type of<br />

information can be gleaned from the institutional environment and<br />

from advisee files, advising notes, transcripts, and our interactions<br />

with students. This general knowledge can provide a basis for<br />

identifying questions that might encourage critical and reflective<br />

thinking. This approach <strong>to</strong> advising involves<br />

• beginning a dialogue in which the advisor guides students;<br />

• teaching students <strong>to</strong> recognize and benefit from both their success<br />

and challenges;<br />

• asking questions that require students <strong>to</strong> think reflectively in<br />

order <strong>to</strong> respond; and<br />

• teaching students <strong>to</strong> express, justify and discuss individual goals<br />

and ideas.<br />

Approaching academic advising as an<br />

opportunity for student learning might<br />

sound like a tall order for already overworked<br />

faculty members. Understanding how we can<br />

integrate learning outcomes in<strong>to</strong> advising<br />

will help us direct students <strong>to</strong> achieve their<br />

academic goals. This Pocket <strong>Guide</strong> offers<br />

practical advice that makes it possible for any<br />

faculty member <strong>to</strong> become a great advisor.<br />

5

References and Resources<br />

Hemwall, M. and Trachte, K. (2005). <strong>Advising</strong> as learning: 10<br />

organizing principles. <strong>NACADA</strong> Journal 25(2), 74-83.<br />

Lowenstein, M. (2005). If advising is teaching, What do advisors<br />

teach <strong>NACADA</strong> Journal 25(2), 65-73.<br />

Martin, H. (2007). Constructing learning objectives for academic<br />

advising. Retrieved June 15, 2009, from <strong>NACADA</strong> Clearinghouse<br />

of <strong>Academic</strong> <strong>Advising</strong> Resources Web site: www.nacada.ksu.edu/<br />

Clearinghouse/<strong>Advising</strong>Issues/Learning-outcomes.htm.<br />

Reynolds, M. (2004). <strong>Faculty</strong> advising in a learner-centered<br />

environment: A small college perspective. <strong>Academic</strong> <strong>Advising</strong><br />

Today 27(2) 1-2.<br />

Practical Tools and Tips<br />

<strong>Academic</strong> advising offers the opportunity <strong>to</strong> engage students in<br />

learning. Yet how can faculty encourage learning during advising<br />

discussions that are typically not lengthy and may occur only<br />

intermittently If we are <strong>to</strong> help advisees develop critical thinking<br />

skills, value their educational experiences, and make important<br />

connections between their academic lives and career goals, then<br />

we must have specific information and <strong>to</strong>ols. Simple steps offer<br />

solutions.<br />

Using an <strong>Advising</strong> Syllabus<br />

Like the course syllabus used<br />

for a class, an advising syllabus<br />

introduces the purpose of advising<br />

and helps students understand<br />

the role of the advisor. It offers<br />

key information about the nature,<br />

responsibilities, and goals of the<br />

advising relationship. If we believe<br />

that students have a right <strong>to</strong> learn<br />

from us and that academic advising<br />

is more than just reviewing degree<br />

requirements and scheduling<br />

6

classes, then an advising syllabus becomes an effective <strong>to</strong>ol in<br />

providing essential information that otherwise must be repeated in<br />

numerous advising conversations.<br />

So that advisor/advisee expectations can be established right away,<br />

the syllabus is generally handed out either during orientation or at<br />

that first advising meeting, and should include<br />

• the advisor’s contact information, office location and office hours;<br />

• a calendar of important dates (e.g., last day <strong>to</strong> drop or withdraw<br />

from a course);<br />

• important campus resources (e.g., the on-line undergraduate<br />

bulletin, registrar, bursar, and financial aid office information);<br />

• an area for advisors <strong>to</strong> personalize the syllabus with any<br />

suggestions or recommendations for their students; and<br />

• the rights and responsibilities of both students and faculty in the<br />

advising/men<strong>to</strong>ring relationship.<br />

The syllabus should also clearly state advisors’ expectations for<br />

students, including that they<br />

• actively participate in the advising process;<br />

• come prepared <strong>to</strong> discuss problems and challenges; and<br />

• are responsible for their own actions.<br />

The syllabus should explain <strong>to</strong> advisees that advisors have<br />

responsibilities as well. These responsibilities may include that<br />

advisors<br />

• be punctual;<br />

• provide accurate information;<br />

• treat students with respect;<br />

• address students’ needs with confidentiality;<br />

• keep accurate records of contacts and student progress;<br />

• refer students <strong>to</strong> appropriate support services;<br />

• assist students in decision making;<br />

• allow students <strong>to</strong> make final decisions; and<br />

• maintain time limits for appointments.<br />

With expectations and responsibilities clearly delineated in a<br />

syllabus, advisors can more easily turn their attention <strong>to</strong> the primary<br />

purpose of the advising meeting, e.g., discussion of academic goals,<br />

career men<strong>to</strong>ring, course scheduling, or discussion of academic or<br />

personal matters.<br />

7