Download PDF - SEARCA Biotechnology Information Center

Download PDF - SEARCA Biotechnology Information Center

Download PDF - SEARCA Biotechnology Information Center

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

34 BIO LIFE January – March 2005<br />

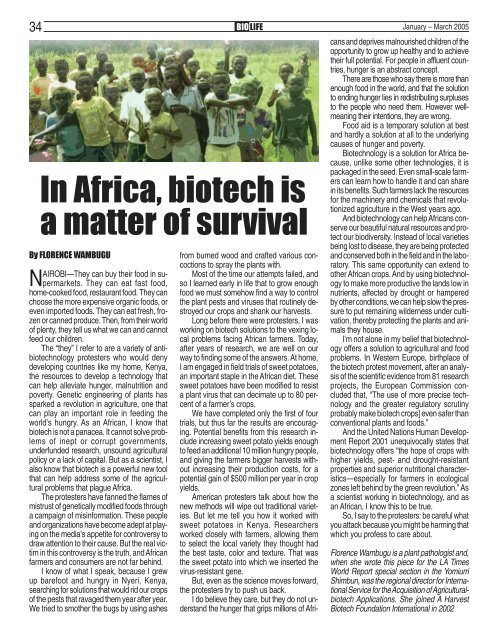

In Africa, biotech is<br />

a matter of survival<br />

By FLORENCE WAMBUGU<br />

NAIROBI—They can buy their food in supermarkets.<br />

They can eat fast food,<br />

home-cooked food, restaurant food. They can<br />

choose the more expensive organic foods, or<br />

even imported foods. They can eat fresh, frozen<br />

or canned produce. Then, from their world<br />

of plenty, they tell us what we can and cannot<br />

feed our children.<br />

The “they” I refer to are a variety of antibiotechnology<br />

protesters who would deny<br />

developing countries like my home, Kenya,<br />

the resources to develop a technology that<br />

can help alleviate hunger, malnutrition and<br />

poverty. Genetic engineering of plants has<br />

sparked a revolution in agriculture, one that<br />

can play an important role in feeding the<br />

world’s hungry. As an African, I know that<br />

biotech is not a panacea. It cannot solve problems<br />

of inept or corrupt governments,<br />

underfunded research, unsound agricultural<br />

policy or a lack of capital. But as a scientist, I<br />

also know that biotech is a powerful new tool<br />

that can help address some of the agricultural<br />

problems that plague Africa.<br />

The protesters have fanned the flames of<br />

mistrust of genetically modified foods through<br />

a campaign of misinformation. These people<br />

and organizations have become adept at playing<br />

on the media’s appetite for controversy to<br />

draw attention to their cause. But the real victim<br />

in this controversy is the truth, and African<br />

farmers and consumers are not far behind.<br />

I know of what I speak, because I grew<br />

up barefoot and hungry in Nyeri, Kenya,<br />

searching for solutions that would rid our crops<br />

of the pests that ravaged them year after year.<br />

We tried to smother the bugs by using ashes<br />

from burned wood and crafted various concoctions<br />

to spray the plants with.<br />

Most of the time our attempts failed, and<br />

so I learned early in life that to grow enough<br />

food we must somehow find a way to control<br />

the plant pests and viruses that routinely destroyed<br />

our crops and shank our harvests.<br />

Long before there were protesters, I was<br />

working on biotech solutions to the vexing local<br />

problems facing African farmers. Today,<br />

after years of research, we are well on our<br />

way to finding some of the answers. At home,<br />

I am engaged in field trials of sweet potatoes,<br />

an important staple in the African diet. These<br />

sweet potatoes have been modified to resist<br />

a plant virus that can decimate up to 80 percent<br />

of a farmer’s crops.<br />

We have completed only the first of four<br />

trials, but thus far the results are encouraging.<br />

Potential benefits from this research include<br />

increasing sweet potato yields enough<br />

to feed an additional 10 million hungry people,<br />

and giving the farmers bigger harvests without<br />

increasing their production costs, for a<br />

potential gain of $500 million per year in crop<br />

yields.<br />

American protesters talk about how the<br />

new methods will wipe out traditional varieties.<br />

But let me tell you how it worked with<br />

sweet potatoes in Kenya. Researchers<br />

worked closely with farmers, allowing them<br />

to select the local variety they thought had<br />

the best taste, color and texture. That was<br />

the sweet potato into which we inserted the<br />

virus-resistant gene.<br />

But, even as the science moves forward,<br />

the protesters try to push us back.<br />

I do believe they care, but they do not understand<br />

the hunger that grips millions of Africans<br />

and deprives malnourished children of the<br />

opportunity to grow up healthy and to achieve<br />

their full potential. For people in affluent countries,<br />

hunger is an abstract concept.<br />

There are those who say there is more than<br />

enough food in the world, and that the solution<br />

to ending hunger lies in redistributing surpluses<br />

to the people who need them. However wellmeaning<br />

their intentions, they are wrong.<br />

Food aid is a temporary solution at best<br />

and hardly a solution at all to the underlying<br />

causes of hunger and poverty.<br />

<strong>Biotechnology</strong> is a solution for Africa because,<br />

unlike some other technologies, it is<br />

packaged in the seed. Even small-scale farmers<br />

can learn how to handle it and can share<br />

in its benefits. Such farmers lack the resources<br />

for the machinery and chemicals that revolutionized<br />

agriculture in the West years ago.<br />

And biotechnology can help Africans conserve<br />

our beautiful natural resources and protect<br />

our biodiversity. Instead of local varieties<br />

being lost to disease, they are being protected<br />

and conserved both in the field and in the laboratory.<br />

This same opportunity can extend to<br />

other African crops. And by using biotechnology<br />

to make more productive the lands low in<br />

nutrients, affected by drought or hampered<br />

by other conditions, we can help slow the pressure<br />

to put remaining wilderness under cultivation,<br />

thereby protecting the plants and animals<br />

they house.<br />

I’m not alone in my belief that biotechnology<br />

offers a solution to agricultural and food<br />

problems. In Western Europe, birthplace of<br />

the biotech protest movement, after an analysis<br />

of the scientific evidence from 81 research<br />

projects, the European Commission concluded<br />

that, “The use of more precise technology<br />

and the greater regulatory scrutiny<br />

probably make biotech crops] even safer than<br />

conventional plants and foods.”<br />

And the United Nations Human Development<br />

Report 2001 unequivocally states that<br />

biotechnology offers “the hope of crops with<br />

higher yields, pest- and drought-resistant<br />

properties and superior nutritional characteristics—especially<br />

for farmers in ecological<br />

zones left behind by the green revolution.” As<br />

a scientist working in biotechnology, and as<br />

an African, I know this to be true.<br />

So, I say to the protesters: be careful what<br />

you attack because you might be harming that<br />

which you profess to care about.<br />

Florence Wambugu is a plant pathologist and,<br />

when she wrote this piece for the LA Times<br />

World Report special section in the Yomiurri<br />

Shimbun, was the regional director for International<br />

Service for the Acquisition of Agriculturalbiotech<br />

Applications. She joined A Harvest<br />

Biotech Foundation International in 2002