2001_000

2001_000

2001_000

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

University of Leicester Archaeological Services<br />

Archaeological Services ULAS<br />

Annual Report <strong>2001</strong>

Annual Report <strong>2001</strong><br />

How long ago was that Putting dates to periods<br />

Palaeolithic – Old Stone Age – 500,<strong>000</strong> BC-9500 BC<br />

First hunter gatherer groups. Climatic changes<br />

Mesolithic – Middle Stone Age – 9500 BC-4500 BC<br />

Hunter gatherer groups. Climate getting warmer<br />

Neolithic – New Stone Age – 4500 BC-2<strong>000</strong> BC<br />

The first farming communities<br />

Bronze Age – 2<strong>000</strong> BC-700BC<br />

First use of metals<br />

Iron Age – 700 BC-AD43<br />

Introduction of iron-working<br />

Roman – AD 43-AD 410<br />

Roman occupation of Britain<br />

Anglo-Saxon – AD 410-1066<br />

Saxon and Scandinavian migration<br />

Medieval – 1066-1500<br />

Norman Conquest to the first Tudor kings<br />

Post-medieval – 1500-1800<br />

Tudor - Stuart - Georgian periods<br />

Modern – 1800-present day<br />

Industrial to nuclear age

University of Leicester Archaeological Services<br />

University of Leicester<br />

Archaeological Services<br />

ULAS<br />

Annual Report<br />

<strong>2001</strong><br />

University of Leicester<br />

University Road<br />

Leicester LE1 7RH<br />

Tel: 0116 252 2848<br />

Fax: 0116 252 2614<br />

On the Internet<br />

www.le.ac.uk/ulas

Annual Report <strong>2001</strong><br />

Institute of Field<br />

Archaeologists<br />

University of Leicester<br />

Archaeological Services<br />

ULAS<br />

Contents<br />

1 Introduction 1<br />

2 Living on the Edge – The Environs of a Neolithic Causwayed Enclosure 2<br />

3 Roman Leicester Revealed – The Stibbe Buildings Evaluation 5<br />

4 Sawgate Bridge Rediscovered 8<br />

5 The Hospital of St John the Baptist 10<br />

6 Leicester Abbey Revisited 12<br />

7 One Man and Two Boats 15<br />

8 Civil War Siege – Excavations at Mill Lane 16<br />

9 A Palace of Dreams – Recoding a 1930s Cinema in Northampton 18<br />

10 A South Wales Blast Furnace – Twentieth-Century Heavy Industry 20<br />

12 ULAS Staff <strong>2001</strong> 22<br />

13 Publications and Conferences <strong>2001</strong> 24<br />

14 Outreach <strong>2001</strong> 25<br />

15 Archaeological Projects <strong>2001</strong> 26<br />

14 ULAS Clients <strong>2001</strong> 29

University of Leicester Archaeological Services<br />

Introduction<br />

The past year has been one of major achievement for<br />

both the University of Leicester Archaeological Services<br />

and the School of Archaeology and Ancient History, to<br />

which it is attached. As is immediately apparent from<br />

this report, ULAS continues to provide a high standard<br />

of service, as a professional archaeological contracting<br />

unit, to a large number of satisfied customers. At the<br />

same time ULAS staff contribute to (and are supported<br />

by) the academic wing of the School. The School was<br />

assessed for both its Research output and its Teaching<br />

and Learning quality in <strong>2001</strong> and came through both<br />

exercises with flying colours, with top ratings of 5A for<br />

research (only 5* is higher) and 24/24 for its teaching<br />

quality. Several ULAS staff were cited in the Research<br />

submission and no less than ten ULAS staff have<br />

contributed their expertise to the School’s teaching<br />

programme in the last year. Similarly, academic advisors<br />

from the School’s core staff are routinely attached to<br />

major ULAS field projects to make the most of a twoway<br />

exchange of expertise within the School. This<br />

symbiosis between academic school and professional<br />

archaeological unit has been a major factor in the success<br />

of ULAS and gives the latter an edge over many of its<br />

professional competitors.<br />

ULAS had a quality audit of its own in the autumn, with<br />

a validation visit by the IFA (Institute of Field<br />

Archaeologists) – the body that serves the professional<br />

archaeology community. The visit passed off very<br />

successfully, with the IFA re-confirming its validation<br />

of the services ULAS offers. Those commissioning work<br />

can do so confident in the knowledge that ULAS meets<br />

exacting professional standards. In addition, as part of<br />

their overall strategy for<br />

offering their staff opportunities<br />

for career development, and<br />

customers a better and better<br />

service, ULAS are also seeking<br />

validation this year under the<br />

Investors in People scheme.<br />

This involves enhancing the<br />

existing staff development and<br />

training structures and once<br />

again, this will help the unit maintain and build on its<br />

reputation for high quality and efficient project work.<br />

It is clear, from the list of projects undertaken, that ULAS<br />

is frequently active in several counties, but the focus of<br />

the work, understandably, remains Leicestershire and<br />

Rutland. After a ten-year period of limited activity, the<br />

past year has seen the start of a major new wave of<br />

construction and redevelopment in Leicester city centre.<br />

ULAS has already been involved in several of these sites<br />

and hopes to continue to contribute its local knowledge<br />

and long experience to excavations in Leicester over<br />

the coming few years. These are exciting times ahead<br />

and ULAS and the School intend to be at the forefront<br />

of archaeology for many years to come.<br />

David Mattingly<br />

Professor of Roman Archaeology<br />

Acting Head of School of Archaeology and Ancient History<br />

March 2002<br />

1

Annual Report <strong>2001</strong><br />

Living on the Edge – The Environs of a Neolithic Causewayed Enclosure<br />

In 1998, geophysical survey by ULAS located a major<br />

Neolithic monument at Husbands Bosworth, Leicestershire<br />

– a causewayed enclosure dating from around 3<strong>000</strong> BC–<br />

the first of its kind known from the county. The monument<br />

consisted of a circular open area,<br />

150m in diameter, originally<br />

enclosed by interrupted banks and<br />

ditches, and would have served for<br />

meetings and ceremonies for the<br />

early farming communities living in<br />

the surrounding Soar, Welland, Swift<br />

and Avon valleys. When the<br />

significance of the discovery had<br />

been established, the site was<br />

withdrawn from proposals for gravel<br />

extraction, and has now been<br />

designated a Scheduled Ancient<br />

Monument (SAM), providing<br />

protection from future development.<br />

Following survey and evaluation, a<br />

modified area was granted planning<br />

permission for gravel extraction, and<br />

three phases of archaeological work<br />

have been undertaken since the<br />

commencement of the quarry<br />

extension.<br />

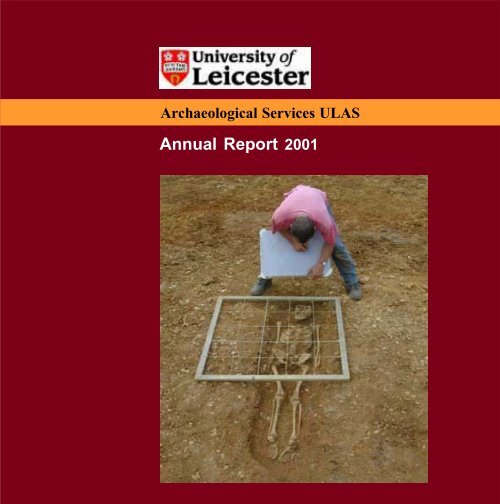

Right: a Neolithic crouched<br />

burial with flint tool-kit at feet.<br />

Initially, archaeological monitoring was carried out during<br />

topsoil stripping for a tunnel, beneath the road, linking the<br />

new quarry with the existing one, a haul road and new areas<br />

allocated for extraction and landscaping. This was followed<br />

by trial trenching and excavation of features found by<br />

geophysical survey to the southwest of the monument.<br />

Further topsoil stripping was then monitored to the north<br />

and south-west of the monument. This has located<br />

archaeological remains of<br />

Neolithic, Bronze Age and<br />

Iron Age date in the areas<br />

surrounding the causewayed<br />

enclosure.<br />

The earliest features on the site<br />

are large numbers of ‘tree<br />

throws’ – round pits with<br />

distinctive dark crescents of<br />

silt on one side where fallen<br />

tree boles have rotted away.<br />

The trees would have been<br />

part of the natural landscape<br />

before the woodland was<br />

cleared and the causewayed<br />

enclosure was constructed.<br />

Contemporary evidence to the<br />

north and south-west of the<br />

Neolithic causewayed<br />

enclosure has been found. To<br />

the north were clusters of pits<br />

in groups containing flint and<br />

Neolithic pottery of the type known as Peterborough ware.<br />

Two of these were of particular interest containing, in<br />

addition to pottery and flint, large saddle querns (grinding<br />

stones) and charred deposits with identifiable cereal remains.<br />

These may have been ‘special deposits’ placed as offerings,<br />

or the querns may have been buried for re-use during<br />

2

University of Leicester Archaeological Services<br />

seasonal visits to the site. A pit to the west of the enclosure<br />

contained slightly later Beaker style pottery of late Neolithicearly<br />

Bronze Age date.<br />

The area south of the enclosure had rather different<br />

Neolithic remains, including a circular monument and human<br />

burials – an inhumation (skeleton) in a crouched position<br />

and two cremations.<br />

The crouched inhumation burial lay at the base of a deep<br />

rectangular pit which was capped by a layer of<br />

burnt cobbles and stones. The burial was positioned<br />

with the head to the south-east. Bone survival<br />

was unusual in that it was either present in generally<br />

reasonable condition or there was very little trace<br />

of it. The pelvis, ribcage and spine and most of the<br />

left leg and arm (i.e. the lower side of the body)<br />

were missing. Although some of the skull had<br />

decayed badly, one side of the upper jaw was in<br />

good condition. Initial indications suggest that the<br />

burial was of a 30-35 year old male.<br />

Near the crouched burial were several Iron Age pits, dug<br />

perhaps 1500 years after the burial, some of which contained<br />

quantities of large burnt cobbles. Could these stones have<br />

come from a stone mound or cairn which had once covered<br />

the burial pit<br />

Trial trenching and excavation were carried out in two<br />

further areas of the quarry extension, targeting features<br />

located by geophysical survey, including a ring ditch and a<br />

small rectangular enclosure. The excavation confirmed the<br />

Enclosure<br />

Neolithic Pits<br />

A tool kit of five late Neolithic/early Bronze Age<br />

flints, which may have originally been in a bag, lay<br />

by the feet, a flint flake near the skull, and two<br />

pieces of animal bone with a flint flake were by<br />

the wrist. Charred remains of an oak plank had<br />

been laid on its edge along the length of the side<br />

of the pit to the north-west of the burial. The plank’s<br />

position in the pit corresponded with a natural layer<br />

of loose silt and gravel along one side, and it may<br />

have acted as shuttering. This could imply that<br />

the pit was dug some time before the body was<br />

placed in it, or that the body remained uncovered<br />

for some time before the pit was filled in.<br />

Right: map of the site showing the<br />

causwayed enclosure and other features.<br />

Late Neolithic Pits<br />

Causwayed Enclosure<br />

Enclosure<br />

Enclosure<br />

Circular Building<br />

Pit Alignments<br />

Ring-ditch<br />

Enclosure<br />

Cremation Burials<br />

Iron Age Pits<br />

Iron Age Pits<br />

Inhumation<br />

Area of Scheduled<br />

Ancient Monument<br />

Geophysical Anomaly<br />

Archaeological Feature<br />

Extent of Watching Brief/Excavation<br />

3

Annual Report <strong>2001</strong><br />

presence of the ring ditch with two narrow causeways to<br />

the north-west. On the basis of the geophysical surveys<br />

this had been interpreted as a ploughed-out circular Bronze<br />

Age barrow. However, although the ditches were extremely<br />

deeply cut, no burial was present nor any feature likely to<br />

have contained one. There was no surviving evidence of a<br />

mound or external banks, although the initial geophysical<br />

survey had indicated that banks might have been<br />

present. The ditch varied in depth, perhaps suggesting<br />

that it had originally been dug out by different groups<br />

of people. Few finds were present the only dating<br />

evidence being sherds of Neolithic Peterborough<br />

ware pottery suggesting that the site was in use<br />

around 3<strong>000</strong>-2500 BC.<br />

Two pit alignments, one crossing the ring ditch, were<br />

also located. Although not closely datable, these may<br />

be evidence of land division in the late Bronze-Early<br />

Iron Age. More<br />

tangible evidence of<br />

occupation occurred in<br />

the Middle to Late Iron<br />

Age, with a circular<br />

building, pits and<br />

enclosures to the south,<br />

and pits and an<br />

enclosure to the north<br />

of the monument. The<br />

circular building cut the<br />

upper layers of the ring<br />

ditch, suggesting that the monument was no longer visible<br />

at this time, with the banks or mound having eroded and the<br />

ditch now backfilled. By this time when the land was being<br />

divided up, it is unclear whether the causewayed enclosure<br />

was still visible as an earthwork.<br />

The work to date at Husbands Bosworth has shown that<br />

the causewayed enclosure was a focus of activity during<br />

the prehistoric period, with evidence of seasonal occupation,<br />

the construction of a circular monument – perhaps a local<br />

variation of a ‘henge’ – and burials, during the Neolithic.<br />

There appears to have been a decline in activity during the<br />

Bronze Age until a period of land division using pit alignments<br />

began, perhaps early in the first millennium BC. By the late<br />

Iron Age, the land was being settled more intensively with<br />

several enclosures and at least one circular building. It is<br />

Above: monumental ring-ditch overlain by<br />

remnants of Iron Age house (foreground).<br />

Left: a large saddle quern (grinding<br />

stone) recovered from one of the pits.<br />

uncertain when the causewayed enclosure ceased to be<br />

visible as a feature in the landscape. Further work may<br />

help to elucidate what influence this important monument<br />

had on evolution of the surrounding landscape.<br />

We would like to thank Lafarge Redland Aggregates and<br />

their consultants, Oxford Archaeological Associates, for their<br />

help and co-operation during this project.<br />

4

University of Leicester Archaeological Services<br />

Roman Leicester Revealed – The Stibbe Buildings Evaluation<br />

In January and February <strong>2001</strong>, ULAS<br />

excavated a series of trial trenches on the site<br />

of the former Stibbe Buildings on Great Central<br />

Street, Leicester. The site lies within the historic<br />

core of the Roman and medieval town and is<br />

earmarked for redevelopment, although no<br />

definite plans have been drawn up as yet.<br />

An initial desk-based archaeological<br />

assessment confirmed that there are known<br />

archaeological remains, of great significance,<br />

within the study area, including the possible<br />

north wall of the Roman macellum (market hall)<br />

and at least one other Roman building. Roman<br />

tessellated pavements, mosaics, painted wall<br />

plaster and masonry walls had all been<br />

previously recorded on the site. The Cyparissus<br />

Pavement, a mosaic on display at Jewry Wall<br />

Museum, may also have been found on this site<br />

in the 17th century. The site lies partially on the frontage of<br />

the medieval High Street, now Highcross Street. The deskbased<br />

assessment confirmed the locations of deep cellars<br />

associated with the former Victorian Stibbe Buildings, which<br />

are known to have caused a great deal of destruction to<br />

archaeological deposits. The report also demonstrated that<br />

in areas away from the cellars there was potential for their<br />

survival.<br />

Ten trenches were excavated across the site, mainly using<br />

a 360º mechanical excavator, with three located over the<br />

areas of the known cellars, in order to confirm the depths<br />

of the cellar floors. The remaining trenches were placed in<br />

areas where cellars were unconfirmed.<br />

Above: a plain tessellated Roman floor.<br />

The trench in the north-western corner of the site, on the<br />

Great Central Street frontage, uncovered Roman<br />

archaeological deposits, surviving 1m below the present<br />

ground surface, sealed by medieval garden soils and modern<br />

demolition debris. The Roman remains had been partially<br />

disturbed by medieval pits, modern wall trenches and a<br />

shallow cellar. The trench revealed a possible Roman road,<br />

aligned north-north-west, in the far western edge of the<br />

trench. This was bounded to the east by a series of gravel<br />

and sand layers, possibly yard surfaces. The remainder of<br />

the trench overlay at least two rooms and a corridor of a<br />

Roman building. Three wall lines, parallel with the possible<br />

5

Annual Report <strong>2001</strong><br />

road, were visible as medieval robber trenches (dated to<br />

the 11th -12th centuries), with two walls on a perpendicular<br />

alignment also hinted at, although unconfirmed. The main<br />

part of the trench overlay a single room with a sequence of<br />

floor layers that suggested a prolonged period of use and<br />

regular refurbishment during the Roman period. One of<br />

the floors was constructed of rough grey tesserae (mosaic<br />

N<br />

Great Central Street<br />

Possible layout of<br />

mosaic<br />

Building 1:<br />

corridor & three<br />

rooms<br />

Above: plan of the Stibbe site with Roman<br />

roads superimposed (grey).<br />

Building 2:<br />

mosaic &<br />

hypocaust<br />

Building 3: the<br />

macellum<br />

tiles). A second room to the south was indicated by a small<br />

patch of floor, made of red ceramic tesserae, with a very<br />

different sequence of floor layers beneath, when compared<br />

with those seen in the room to the north. Bounded by two<br />

of the robber trenches on the eastern side of these rooms<br />

was a particularly well-made grey tessellated floor, appearing<br />

to represent a corridor from which these other rooms would<br />

have been accessed.<br />

The trench could not be<br />

extended to the east due<br />

to the presence of a<br />

substantial modern<br />

concrete floor, so it was<br />

not possible to see what<br />

lay on the eastern side of<br />

the corridor.<br />

Highcross Street<br />

The trench in the<br />

northern part of the site<br />

had been disturbed by<br />

modern services.<br />

However, evidence for<br />

medieval rear-yard<br />

activity, in the form of<br />

numerous pits, was<br />

recorded. Areas of the<br />

base of the trench also<br />

revealed the remains of<br />

a Roman building with a<br />

stone-lined flue for a<br />

hypocaust (under-floor<br />

heating system), with<br />

mortar floors above. In<br />

the north side of the<br />

trench, above the flue,<br />

lay part of a mosaic of<br />

fine white, grey and<br />

black tesserae, and<br />

above this, the collapsed superstructure of the building.<br />

Vaughan Way<br />

6

University of Leicester Archaeological Services<br />

Evidence for other mortar floors and a wall, since robbed<br />

of its stone, were also found within the trench.<br />

The two trenches in the middle of the site revealed wellpreserved<br />

medieval and Roman levels at a depth of around<br />

1m from the present ground surface. The excavation of<br />

medieval pits and part of a well exposed further evidence<br />

of the robbed walls<br />

and clay floor of a<br />

Roman building.<br />

Two small handexcavated<br />

trenches to<br />

the south-east<br />

provided evidence for<br />

post-medieval and<br />

medieval buildings.<br />

These would have<br />

fronted on to<br />

Highcross Street, and<br />

pre-dated those that<br />

were demolished in<br />

the mid-twentieth<br />

century, prior to the<br />

construction of<br />

Vaughan Way.<br />

The trench in the southern part of the site produced part of<br />

a substantial stone wall, with 0.5m deep footings, in its<br />

northern end. The wall was aligned close to east-west. A<br />

parallel wall, 2.8m to the south, was also seen surviving<br />

beneath the brick floor of the modern cellar. The top of this<br />

wall was level and suggests that it was a base for a<br />

‘stylobate’ – a horizontal course of stone blocks onto which<br />

columns would have been stood to form a colonnade. These<br />

walls may be part of the substantial stone structure seen<br />

during the Blue Boar Lane excavations to the south of the<br />

site in 1958.<br />

The evaluation has shown that particularly well-preserved<br />

archaeological remains exist within the area, close to the<br />

present ground surface. They may also survive beneath<br />

some of the modern cellar floors. At least two substantial<br />

Roman buildings were revealed. To the north, a room with<br />

a hypocaust (central heating system) and fine quality<br />

patterned mosaic floor, next to a corridor with rooms leading<br />

off it, was found,<br />

suggesting the<br />

presence of a high<br />

status town house.<br />

To the south, on the<br />

other side of a<br />

Roman street, lay a<br />

substantial stone built<br />

building, which may<br />

have been the town’s<br />

market hall – a large<br />

public building known<br />

as the macellum.<br />

Above: a glimpse of a fine patterned mosaic<br />

floor below a collapsed Roman building.<br />

During the medieval<br />

period it is likely<br />

that this area was<br />

mainly gardens or<br />

agricultural land, with<br />

buildings only on the frontage of Highcross Street and Friars<br />

Causeway, thus little structural evidence from the medieval<br />

period was revealed in the majority of the site area.<br />

We would like to thank Westmoreland Properties both for<br />

their help and co-operation, and for funding this project.<br />

7

Annual Report <strong>2001</strong><br />

Sawgate Bridge Rediscovered<br />

ULAS was commissioned by the Environment Agency to<br />

supervise the groundworks during the excavation of silt traps<br />

on Burton Brook and the river Eye, south of Melton<br />

Mowbray, and east of Burton Lazars.<br />

The site lies on Burton Brook, half a mile east of Burton<br />

Lazars where Europe’s largest leper colony and hospital<br />

stood for over 400<br />

years. The leper<br />

hospital was founded by<br />

Roger de Mowbray<br />

after he inherited the<br />

land from his father<br />

Nigel d’Aubigny in<br />

1138. This was<br />

documented in a charter<br />

dated to 1154-1162<br />

which records that<br />

Roger donated a<br />

hospital and a mill<br />

(presumably Man Mill<br />

at the nearby village of<br />

Brentingby).<br />

The brethren of the<br />

hospital soon became large landowners, as a result of<br />

numerous donations. Their management interest in the estate<br />

resulted in the creation of a large open-field system by the<br />

12th century, incorporating 2,800 acres of farming land.<br />

Excavations were carried out within this planned medieval<br />

landscape, at the site of a new silt trap, being constructed<br />

as part of a flood alleviation scheme. These unearthed the<br />

remains of a medieval stone bridge which was not only<br />

contemporary with the Leper hospital, but is even mentioned<br />

by name as ‘Salgate Brygge’ in 14th-century land surveys.<br />

The Saltgate bridge got its name from the Roman ‘Sawgate’<br />

road on which it sat. This was one of the main routes from<br />

the east coast via which salt was traded into the interior of<br />

Britain. The road is<br />

thought to diverge from<br />

the Fosse Way at<br />

Syston to follow the<br />

ridge north-east to near<br />

Frisby-on-the-Wreake.<br />

Here it appears to turn<br />

east past Eye Kettleby,<br />

through Burton Lazars,<br />

crossing Burton Brook<br />

and on to Cord Hill and<br />

Thistleton.<br />

Above:excavation in progress; a multi-phase stonebuilt<br />

medieval bridge takes shape in the mud.<br />

The Bridge<br />

The excavation of the bridge showed that it had been built<br />

in several distinct phases. The first involved the laying of<br />

large cobbles in the base of the brook, which for several<br />

8

University of Leicester Archaeological Services<br />

years may have sufficed as a ford crossing. At a later date<br />

a more substantial bridge was built of limestone. Evidence<br />

of this first stone construction was found only on the west<br />

bank of the brook, and consisted of a large D-shaped<br />

Although there is no direct evidence that Saltgate Bridge<br />

was built by or for the farming brethren of Burton Lazars<br />

hospital, it is clear that it was standing during the hospital’s<br />

heyday and would certainly have been an important crossing<br />

point, and instrumental in the day to day management of<br />

the planned farming landscape that the brethren had<br />

established.<br />

Thanks are due to the Environment Agency for their help<br />

and co-operation with this project.<br />

Left:Burton Brook in flood, the medieval<br />

bridge still spans the current course of<br />

the brook.<br />

abutment terraced into the bank of the brook. It is presumed<br />

that a wooden superstructure (which has since been lost)<br />

may have sat atop this structure and spanned the brook to a<br />

similar structure on the east bank. No evidence of a<br />

coresponding abutment was found during excavation, but it<br />

remains possible that this may lie just outside of the area of<br />

investigation or its stone may<br />

simply have been reused in<br />

the construction of later<br />

phases of the bridge.<br />

Following several years of<br />

flooding a third phase of<br />

construction was added, in<br />

the form of a well-hewn<br />

sandstone parapet, the<br />

squared blocks of which still bore clear tooling marks. Later<br />

the banks of the brook, just down-stream of the bridge, were<br />

consolidated with a broad layer of pebbles.<br />

Above: well-shaped blocks were used in the<br />

parapet of the bridge during the third phase of<br />

construction.<br />

9

Annual Report <strong>2001</strong><br />

The Hospital of St. John the Baptist, Lutterworth<br />

The hospital of St. John the Baptist, Lutterworth,<br />

Leicestershire, was founded on land known locally as ‘the<br />

warren’ during the reign of King John in 1218, and was<br />

dissolved in 1577. The hospital complex was a wealthy<br />

institution in its day, its revenue being greater than that of<br />

the contemporary parish church of St. Mary’s. Much of<br />

this wealth was doubtless generated by two mills,<br />

documented as belonging<br />

to the estate upon its<br />

dissolution in 1577, and<br />

from farming land at<br />

Gilmorton, Cotesbach,<br />

Shawell and Bitteswell. It<br />

is, however, unclear<br />

whether the hospital mills<br />

occupied the ‘warren’ site<br />

itself.<br />

In the 1890s, rubble and<br />

human bones were discovered during<br />

the construction of what is now the<br />

A426 main road. Not only had<br />

remnants of the hospital buildings been<br />

unearthed but, for the first time, there<br />

was evidence that the hospital had its<br />

own cemetery.<br />

Avove: one grave, two burials; these two burials<br />

were found one on top of the other in a ‘doubledecker’<br />

style. The top grave contained 14thcentury<br />

floor tiles, the bottom one a coffin.<br />

A small team of excavators from ULAS had undertaken<br />

evaluative trenching of the land, now occupied by Mill Farm,<br />

in 1996 on behalf of the new landowners, Hallam Land<br />

Management, who were proposing to redevelop the site.<br />

The discovery of five graves confirmed the existence of<br />

the hospital cemetery, while spreads of cobbles also hinted<br />

at the presence of structures, although their character was<br />

unclear.<br />

In <strong>2001</strong> ULAS was commissioned to carry out more<br />

extensive work to ensure satisfactory recording of the areas<br />

of archaeological importance which<br />

would be affected by the proposed<br />

development. In particular a large<br />

area was stripped to better define<br />

the cemetery and the possible<br />

cobble structures.<br />

Twenty-two complete graves were<br />

identified in a very<br />

overgrown plot of land<br />

to the south of the<br />

farmhouse. There had<br />

been much disturbance<br />

to this cemetery in the<br />

years since its<br />

abandonment, including<br />

modern ditches and<br />

sand quarrying pits,<br />

which had clearly<br />

destroyed many more<br />

graves, judging by the<br />

large quantities of disturbed human bones in their backfills.<br />

The excavated graves all contained well-preserved<br />

skeletons, all but one of which were interred according to<br />

Christian tradition, with their heads at the west end of the<br />

graves. One individual, the only juvenile, was buried the<br />

other way round, with the head at the east.<br />

Despite the Christian rules banning the inclusion of gravegoods<br />

in burials of this date, some interesting artefacts were<br />

10

University of Leicester Archaeological Services<br />

Above: some of the<br />

items found in the<br />

graves.<br />

and the remnants of some external mortared walls were<br />

also visible. Unfortunately, much of this structure had been<br />

destroyed by a modern farm building. Few datable finds<br />

were recovered although some fragments of floor tiles<br />

(similar to those found in the grave) were identified. It is,<br />

however, uncertain whether the 14th-century tile fragments<br />

were contemporary with the structure or whether they had<br />

been incorporated into its fabric at a later date. Additional<br />

cobble structures, including a long enclosure wall, were also<br />

identified within the excavation area.<br />

recovered from the grave fills. One individual was found to<br />

be wearing a very plain ‘penannular’ style brooch,<br />

commonly used as a fastening for clothing, while another<br />

was found with six 14th-century floor tiles, four of which<br />

were decorated with the Arms of Beauchamp. Although<br />

most of the burials appeared to be simple interments, without<br />

coffins (the bodies may simply have been wrapped in<br />

shrouds that have since rotted), one burial was found to<br />

incorporate a wooden coffin held together with iron nails.<br />

Interestingly this coffin burial was also the only double<br />

interment, found in ‘double-decker’ style below the burial<br />

containing the tiles.<br />

Detailed laboratory analysis of the skeletons indicated that<br />

the population consisted primarily of mature adult males,<br />

bearing the obvious signs of old age; arthritis was very<br />

common. Only one female and one juvenile, of 15 years,<br />

broke the trend.<br />

To the south-west of the cemetery area, a simple track<br />

was identified running in a north-west to south-east direction.<br />

This made use of small rounded pebbles embedded in clay,<br />

presumably to stabilise the ground and to prevent rutting by<br />

cartwheels. This track may have led from the hospital<br />

buildings to the cemetery.<br />

Adjacent to the pebble track lay a large cluster of cobbles<br />

which appeared to form the internal flooring of a cobble<br />

building, built in a similar style to the local parish church. A<br />

slate-lined drainage channel could be seen below the floor<br />

Above: the cobble-built structure and floor.<br />

A great deal of analytical work on the finds from the site at<br />

Mill Farm remains to be completed, and it is hoped that in<br />

the near future a more detailed picture may be formed of<br />

the nature of these remains. What is already apparent is<br />

that the latest excavations have succeeded in locating at<br />

least part of the lost hospital of St. John’s.<br />

We would like to thank Hallam Land Management for their<br />

help and co-operation with this project.<br />

11

Annual Report <strong>2001</strong><br />

Leicester Abbey Revisited<br />

In July and August <strong>2001</strong>, ULAS supervised a second training<br />

excavation in Abbey Grounds, Abbey Park, Leicester for<br />

second-year students of the School of Archaeology and<br />

Ancient History, Leicester University. The Abbey Grounds<br />

lie to the west of the<br />

River Soar, and<br />

contain the<br />

excavated plan of<br />

Leicester Abbey,<br />

one of the<br />

wealthiest Augustinian<br />

houses in the<br />

country, together<br />

with the ruins of<br />

Cavendish House, a<br />

16th-17th century<br />

mansion. The fieldwork<br />

concentrated<br />

on Cavendish<br />

House, although<br />

trenches were also<br />

examined within the<br />

Chapter house of the Abbey.<br />

Cavendish House<br />

Although most of the abbey buildings, including the church,<br />

were razed to the ground within a few years of the<br />

Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1538, the main gatehouse,<br />

boundary walls and farm buildings survived. Under the<br />

ownership of the Hastings and Cavendish families in the<br />

16th and 17th centuries, the gatehouse became a domestic<br />

residence and underwent many structural modifications. It<br />

was burnt down in 1645 during the English Civil War and in<br />

the 18th and 19th centuries the ruined shell was once again<br />

re-used and rebuilt<br />

several times, as a<br />

farm.<br />

Our current<br />

understanding of the<br />

structural sequence<br />

of the surviving<br />

fabric of Cavendish<br />

House is based on an<br />

examination of 18th<br />

and 19th century<br />

prints, supplemented<br />

by a visual<br />

inspection of the<br />

interior and exterior<br />

of the building. The<br />

Above: reconstruction drawing of Leicester Abbey,<br />

reproduced by kind permission of John Finney.<br />

upstanding portion of the building is now known as Abbey<br />

House and was uninhabited at the time of the evaluation.<br />

Access to the building allowed time for analysis of its internal<br />

fabric and of its constructional phases.<br />

12

University of Leicester Archaeological Services<br />

Above: an engraving of Cavendish house in 1841.<br />

Excavations were undertaken in the region of the<br />

standing people.<br />

The 1538 survey of the abbey describes the<br />

gatehouse as ‘a square lodging on either side<br />

of the gatehouse in which are five chambers<br />

with chimneys and large glazed windows, the<br />

walls being of stone and covered with lead,<br />

and with four stone turrets at the corners of<br />

the same’. Evidence relating to the southern<br />

façade of the building, including the southwestern<br />

corner tower, was uncovered during<br />

the evaluation. The remains of this tower,<br />

suggest that it contained a spiral staircase<br />

to gain access to both the upper rooms, as<br />

well as to a cellar. Possible evidence for the<br />

north-eastern corner tower is visible on the<br />

existing northern façade of Cavendish House,<br />

whilst evidence for the north-west tower may<br />

be indicated by irregular stone foundations visible within<br />

the existing cellars of Abbey House. Engravings also show<br />

Although the evaluative excavations within the area<br />

of Cavendish House were of a very limited nature,<br />

they have enabled the identification of a series of<br />

discrete phases of structural activity for which a<br />

relative chronology may be tentatively proposed.<br />

The earliest structure encountered almost certainly<br />

relates to the medieval abbey gatehouse. This was<br />

probably originally of a simple form, comprising a<br />

central north-south carriageway some 2.5m (8.3ft)<br />

wide at its narrowest, flanked on either side by a<br />

range of rooms. Evidence for the walls of this<br />

structure came in the form of surviving masonry<br />

footings and robber trenches. The existence of a<br />

structure on the northern side of the building,<br />

possibly a porch, projected from the results of the<br />

2<strong>000</strong> season evaluation, was confirmed.<br />

Above: training excavations in progress at Cavendish house.<br />

13

Annual Report <strong>2001</strong><br />

the northern edge of the earlier foundations. The<br />

eastern wing also appears to have been rebuilt<br />

at this time as a stair tower. The extant large<br />

double chimney breast to the west on the the<br />

southern façade which appears on engravings,<br />

may also be of a similar date to this phase of<br />

rebuilding, perhaps serving a kitchen complex.<br />

Engravings show that the former gatehouse<br />

towers on the southern façade were retained in<br />

this later rebuild phase.<br />

Claustral buildings<br />

Above: floor tiles uncovered in the cloister walk of<br />

Leicester Abbey.<br />

towers projecting from the southern façade of Cavendish<br />

House, flanking the carriageway entrance through the<br />

building, and the footings for both of these structures were<br />

also revealed. The excavated evidence would suggest that<br />

although the northern wall of the medieval gatehouse was<br />

probably incorporated into this phase of construction, the<br />

southern wall was entirely replaced.<br />

By the late 16th century, an east and west wing were added<br />

to the northern façade of the medieval gatehouse and<br />

evidence suggesting that both wings were cellared was also<br />

found.<br />

In the early 17th-century, the northern façade of the building<br />

with its projecting medieval porch and later flanking wings,<br />

seems to have been flattened with the construction of a<br />

linking wall. The only evidence for this is from the surviving<br />

north wall itself, which respects the line of the foundations<br />

of the postulated medieval porch, being built directly against<br />

Two trenches were positioned within the eastern<br />

part of the Chapter House of the Abbey. The<br />

trenches were located in order to clarify the<br />

position of the Chapter House walls which had been<br />

reconstructed in the 1930s after excavation. This evidence<br />

had been uncovered again during the 2<strong>000</strong> season of<br />

evaluation. One of the trenches revealed a large stone<br />

wall footing, not corresponding to any of the reconstructed<br />

walls. Two possible robber trenches were also recorded,<br />

one corresponding with that seen during the 2<strong>000</strong> season.<br />

The second trench was excavated in an attempt to uncover<br />

the expected continuation of the stone footings, but they<br />

were not found. In both trenches it was evident that in<br />

places a 1m depth of re-deposited natural gravels existed<br />

over what is thought to have been undisturbed ground. A<br />

single trench was excavated on the eastern side of the<br />

reconstructed wall of the Chapter House, which suggested<br />

that the undisturbed natural ground lay directly below the<br />

topsoil on this side of the wall. The work within the Chapter<br />

House would suggest that the reconstructed walls appear<br />

to surround a structure with a reduced floor level. However,<br />

the layout of the reconstructed walls remains open to<br />

question with nothing of the original medieval evidence used<br />

to set them out having survived.<br />

14

University of Leicester Archaeological Services<br />

One Man and Two Boats<br />

Above: the Tug ‘Birmingham’. The<br />

hull has been over-plated at the bow and<br />

stern and the cabin is not the original.<br />

In early <strong>2001</strong>, ULAS were commissioned to carry out an<br />

external survey of two historic craft, for British Waterways,<br />

using a Reflectorless EDM Theodolite. This equipment<br />

permits the swift recording of thousands of points on any<br />

surface, be it on iron, brick or wood, and can be operated<br />

by one person.<br />

The form and visible repairs of the two boats were to be<br />

recorded, while out of the water, before restoration work.<br />

The vessels will form part of British Waterways’ fleet of<br />

boats used for education programmes.<br />

The reflectorless survey provided accurate base drawings<br />

that were to be augmented with more detailed study.<br />

The two vessels represented different<br />

aspects of the history of the waterways<br />

– one is a Tug and the other is an<br />

unpowered carrying boat called a Day<br />

Boat or ‘Joey’.<br />

The Tug, ‘Birmingham’, built of iron, is<br />

45 feet (13.61m) long with a beam of<br />

just under 7 feet (2.09m) and a draught of 4 feet (1.35m)<br />

and was built in 1912. It was one of a series of similar tugs<br />

built for the Worcester and Birmingham Canal for pulling<br />

unpowered boats through tunnels. The shape of the stern<br />

was designed for a large propeller to give optimum pulling<br />

power.<br />

Joeys were 70 feet (21.63m) long, and 7 feet (2.08m) wide,<br />

with either open or small closed cabins at the stern. They<br />

were built in their thousands making them the most common<br />

boats on the canals of the West Midlands. The boat shown<br />

here was also of riveted iron construction. Patches have<br />

been welded to the outside of the hull, where corrosion behind<br />

the internal frames or knees had occurred during its long<br />

periods of use.<br />

Right: ‘Joey’, BW Asset<br />

80393. This particular<br />

boat could only be<br />

steered from one end.<br />

Others may have had a<br />

rudder at either end.<br />

15

Annual Report <strong>2001</strong><br />

Civil War Siege - Excavations at Mill Lane, Leicseter<br />

16<br />

Evaluation by trial trenching at a site on the south side of<br />

Mill Lane, Leicester for De Montfort University, located,<br />

amongst other things, a massive north-east to south-west<br />

aligned ditch. Further work confirmed that this formed part<br />

of Leicester’s town defences at the time of the English<br />

Civil War in the mid 17th century. By this date the earlier<br />

medieval town defences had all but disappeared, the walls<br />

robbed for building stone and the ditches infilled to allow<br />

new building as the<br />

town expanded<br />

beyond its early core.<br />

A new defensive<br />

circuit of earthen<br />

banks and ditches was<br />

therefore constructed,<br />

enclosing most of the<br />

prosperous north and<br />

east suburbs but not<br />

the poorer suburb to<br />

the south, which was<br />

apparently considered<br />

expendable. Houses<br />

on the line of, or lying<br />

outside the new<br />

defences, were<br />

demolished, and the<br />

Records of the Borough of Leicester record payments made<br />

for taking down houses ‘beyond the south gate’ in 1643-44.<br />

Incorporated into the defensive line was the precinct wall<br />

of the Newarke (a corruption of ‘New Work’). This<br />

substantial stone-built wall had originally enclosed an<br />

ecclesiastical college founded in the early fourteenth century,<br />

but following the Dissolution of the Monasteries, the area<br />

had become an exclusive residential suburb which was home<br />

to many of Leicester’s wealthiest citizens. Contemporary<br />

documentary accounts indicate that the Newarke was not<br />

adequately fortified prior to the Royalist assault on Friday<br />

30th May 1645, and is probably no coincidence, therefore,<br />

that when this attack came, it was from the south. The<br />

southern wall of the Newarke precinct, on the north side of<br />

Mill Lane – opposite the excavation site, bore the brunt of<br />

this attack, from a<br />

battery of cannon<br />

stationed somewhere<br />

in the vicinity of the<br />

present day<br />

Above: the massive 17th-century<br />

defensive ditch identified at Mill Lane.<br />

Leicester Royal<br />

Infirmary, and was<br />

soon breached. After<br />

the town’s capture by<br />

the Royalists, the<br />

breach was repaired<br />

and work on<br />

strengthening the<br />

defences around the<br />

Newarke was begun.<br />

It is unclear, however,<br />

how much was done<br />

prior to the Parliamentarian recapture of the town on June<br />

16th, just over a fortnight later, following their decisive victory<br />

at Naseby. The documentary evidence for the inadequacy<br />

of the defences around the Newarke, makes it possible to

University of Leicester Archaeological Services<br />

suggest, with some degree of confidence, that the Mill Lane<br />

ditch dates to the period after the first siege. Less clear,<br />

however, is whether this was a Royalist work completed<br />

before June 16th, or a later Parliamentarian defence. The<br />

least truncated section of the ditch permits some appreciation<br />

of the original scale of this earthwork. With an equivalent<br />

bank on the north-west side, the difference in height between<br />

base of ditch and top of bank would have been somewhere<br />

in the region of 6.5m. Given the time it would have taken to<br />

construct an earthwork of this scale, it<br />

may be tentatively suggested that it was<br />

probably not completed until after the<br />

town’s recapture by Parliamentarian<br />

forces.<br />

Few finds were recovered from the ditch,<br />

which would have been regularly cleaned<br />

out when in use, and was quickly<br />

backfilled following the end of the conflict.<br />

A single lead musket ball was found<br />

embedded in the north-west side of the<br />

ditch, however. Weighing 0.8 ounces (20<br />

shot to the pound), this is smaller than the<br />

standard sized musket shot (12 to the<br />

pound) in use at the time. Problems with<br />

the standardisation of military ordnance<br />

were not uncommon, however, and 20 to<br />

the pound shot has been found in quantity<br />

at other Civil War period sites. A fragment of a possible<br />

lead cannon ball was also found. This was similar in size to<br />

iron cannonballs of the period previously found in the area,<br />

lead cannonballs were certainly used at the siege of<br />

Leicester and one was found embedded in the wall of Trinity<br />

Hospital, in the Newarke, in 1901. The incomplete and<br />

distorted shape of the Mill Lane find may represent impact<br />

damage.<br />

Examination of the information from this and other sites in<br />

the vicinity where Civil War period remains have been found,<br />

together with the evidence from contemporary sources,<br />

should permit a reconstruction of the form and development<br />

of the Civil War defences around the south of the town.<br />

We would like to thank De Montfort University for their<br />

help and co-operation with this project.<br />

Above: repaired breach in the Newarke wall, adjacent<br />

to the excavation site as it appeared in the 19th century,<br />

after Hollings (1840).<br />

This site has provided the rare opportunity for archaeological<br />

evidence to be linked to well documented and dated events.<br />

17

Annual Report <strong>2001</strong><br />

A Palace of Dreams - Recording a 1930s Cinema in Northampton<br />

Historic building survey formed an increasing<br />

part of the work of ULAS in <strong>2001</strong>, including<br />

a rare departure from our normal repertoire<br />

of domestic and industrial structures; the<br />

recording of a twentieth-century modernist<br />

building in Northampton, the grade II listed<br />

Savoy Cinema (latterly the ‘Cannon’). The<br />

building was designed by the house architect<br />

for Associated British Cinemas (ABC), W.R.<br />

Glen, and opened its doors in 1936 with a<br />

showing of ‘Broadway Melody’ starring Jack<br />

Benny and Eleanor Powell. Coverage of the<br />

opening of the cinema in the local paper, the<br />

Chronicle and Echo extols the virtues of the<br />

new building, regarded as ‘the last word in comfort,<br />

splendour and<br />

modern equipment’.<br />

The building, which<br />

could accommodate<br />

1,954 persons,<br />

including circle<br />

seating of 696, was<br />

furnished with a<br />

state-of-the-art air<br />

conditioning plant,<br />

projection and sound<br />

systems and could be<br />

evacuated in minutes<br />

in the event of fire.<br />

The cinema had full<br />

stage facilities and<br />

was the venue for many famous live acts including, in<br />

November 1963, the Beatles who performed ten numbers<br />

on stage, culminating with ‘Twist and Shout’ during ‘twentysix<br />

minutes of mass frenzy’. Two additional screens were<br />

installed in the 1970s and the cinema finally closed in 1995<br />

after a showing of ‘Pulp Fiction’. The building is now owned<br />

by the Jesus Army Charitable trust – sponsors of the survey<br />

– who propose to turn it into a worship and care centre.<br />

English Heritage has recognised the value of cinema history<br />

and has undertaken a study of surviving buildings throughout<br />

the country, with a view to adding to those already on the<br />

statutory lists, noting that ‘many cinemas and<br />

former cinema buildings are not<br />

only a unique, but a<br />

much loved, part of our<br />

culture’. Survey of the<br />

Savoy has shown that it<br />

survives remarkably intact<br />

as one of the few remaining<br />

examples of purpose-built<br />

18

University of Leicester Archaeological Services<br />

1930s ‘super cinemas’ of the ABC chain in the region. The<br />

safety and comfort of the audience along with a desire to<br />

create an atmosphere of opulence and escapism as part of<br />

decoration in all public parts of the cinema has long since<br />

disappeared under later rather garish paintwork (see back<br />

cover), but the survey and documentary research has<br />

provided valuable information which will inform<br />

future restoration proposals.<br />

The project has proved to be most rewarding and<br />

has highlighted the importance of an integrated<br />

approach to the recording of historic structures, using<br />

evidence not only from original survey, but from<br />

documentary sources, such as newspaper reports,<br />

eyewitness accounts and original building plans.<br />

Above: the original cinema interior showing<br />

the organ in position (courtesy Allen Eyles).<br />

the picture-going experience was clearly at the forefront of<br />

the architect’s brief. Hence, the building is not only<br />

innovative in terms of architecture and interior decoration,<br />

but also in terms of provision for fire prevention, means of<br />

escape and environmental controls.<br />

Although some damage has occurred to the original façade<br />

and entrance hall, the main auditorium is largely intact, with<br />

its magnificent proscenium arch, balcony and concealed<br />

lighting, was regarded as one of the most remarkable<br />

features of the building at the time of closure. The illuminated<br />

console of the Compton organ would originally have risen<br />

from the centre of the stage. The organ not only produced<br />

a wide range of musical effects, but its lighting could also<br />

be made to change in harmony with the sounds. The original<br />

The mighty Compton Organ installed in this<br />

theatre embodies many new features.<br />

Possessing a natural quality of resonance,<br />

the Organ gives a wonderful impression of<br />

tone, since the notes of a melody literally<br />

melt in to eachother. By means of an<br />

amazingly clever system of lighting, the<br />

console yields a remarkable range and<br />

combination of colours.<br />

In this way the instrument gives a pleasing<br />

effect both to the ear and eye.<br />

19

Annual Report <strong>2001</strong><br />

A South Wales Blast Furnace - Twentieth-Century Heavy Industry<br />

Despite the importance of iron and steel manufacture to<br />

the British economy in the 20th century, no complete steelcased<br />

furnace has been preserved and only a handful of<br />

these remain, such as Redcar and<br />

Scunthorpe in England and Port<br />

Talbot in Wales. ULAS was<br />

approached when one of the Port<br />

Talbot furnaces was made the<br />

subject of an environmental impact<br />

assessment for a proposed<br />

regeneration project including a<br />

new road. The School of<br />

Archaeology and Ancient History<br />

has recognised expertise in<br />

Industrial Archaeology and ULAS<br />

was fortunate in having access to<br />

the knowledge and experience of<br />

Professor Marilyn Palmer and<br />

Peter Neaverson whilst carrying<br />

carry out this work. Blast furnace<br />

No. 3 at the Margam Steel works,<br />

Port Talbot, the subject of this<br />

assessment, is certainly one of the<br />

largest industrial structures<br />

examined by these experts.<br />

Swansea and its immediate surroundings had become a<br />

centre for copper smelting during the 18th century. Ores<br />

from south-west England were shipped into the area and<br />

smelted using the abundant supply of cheap coal; copper<br />

works were established at Taibach (now part of Port Talbot)<br />

and Cwmavon. Iron production in the hinterland, using local<br />

ore, coal and limestone, grew rapidly in the early 19th<br />

century. However, suitable local ore supplies became<br />

exhausted and the ironworks became reliant on ore from<br />

other parts of England. The economic disadvantages of this<br />

resulted in the import of foreign<br />

ores which eventually led to the<br />

movement of iron and steel making<br />

towards the coast, which enabled<br />

them to take advantage of the<br />

local market for steel for tinplate<br />

manufacture. The Margam iron<br />

and steel works at Port Talbot were<br />

the result of investment by a large<br />

tinplate manufacturer at a new site<br />

with good shipping and railway<br />

facilities. Baldwins’ integrated iron<br />

and steel works opened in 1920<br />

with two of the three blast<br />

furnaces originally planned in<br />

operation and probably<br />

represented the best of then<br />

current practice.<br />

Left: blast furnace no.3 protrudes<br />

through the cast house roof.<br />

Further development at Margam works slowed down during<br />

the depression in the 1920s and 1930s. However, increased<br />

wartime demand probably led to the completion of the No.<br />

3 blast furnace by 1941. In the post-war reconstruction,<br />

Baldwins became part of the Steel Company of Wales which<br />

made a massive further capital investment at Port Talbot.<br />

This involved rebuilding and enlarging the three blast furnaces<br />

20

University of Leicester Archaeological Services<br />

at Margam Works and building a new open-hearth steel<br />

plant and hot-strip continuous rolling mill at Abbey Works<br />

on adjacent reclaimed land to the south. The original three<br />

furnaces were rebuilt with substantial increases in their<br />

production capacity but their further enlargement was limited<br />

by the constraints of their dockside site. In the 1950s two<br />

Above: Margam works from the air in 1957. The original<br />

blast furnaces can be seen next to the quay, far left.<br />

new furnaces were built, and later a new deep-water<br />

harbour to allow much larger ships to off-load to a new ore<br />

storage area. Once the new No. 4 and 5 furnaces began<br />

production, the older furnaces, Nos. 1 and 2 were<br />

demolished. However, No. 3 furnace was retained as a<br />

stand-by, refurbished and brought back into service in 1991/<br />

2 for a limited period. Since that date the furnace and the<br />

ancillary plant have been abandoned and allowed to<br />

deteriorate.<br />

The present buildings and structures within the development<br />

site fall into two main categories, the ore handling facilities<br />

and the blast furnace plant, both of which were originally<br />

planned in 1917 as a ‘state of the art’ integrated iron and<br />

steel works to produce pig iron using imported ores. The<br />

ore handling facilities are, in part, some 80 years old with<br />

the remainder representing modifications to handle everincreasing<br />

amounts of ore imports required by the enlarged<br />

furnaces, until the new harbour and ore storage areas to<br />

the south-west were brought into use around 1969/70. The<br />

blast furnace plant is mostly of comparatively recent date,<br />

much stemming from the rebuilding of the furnace in 1950/<br />

2, although some of the remaining plant may be the original,<br />

now over 80 years old.<br />

No. 3 blast furnace is steel-cased and about 70m (225ft)<br />

high, representing the rebuild of 1950 to 1952, when the<br />

hearth diameter was increased from 16ft to 25ft 9in (c.<br />

4.9 - 7.9m). The rebuilding was carried out on the base<br />

of the original furnace which seems to have been<br />

constructed during World War II. The cast house encloses<br />

the base of the furnace with floor channels for slag and<br />

molten iron, which was directed into rail-mounted ladle<br />

cars on the north-east side, and the slag to cars on the<br />

south east side. An overhead travelling crane and some<br />

ladle cars remain in situ. The furnace remains as abandoned<br />

after its last use in 1991/2, although much of the furnace,<br />

equipment, walkways, guard rails, pipe work and support<br />

structures are severely corroded.<br />

The No. 3 blast furnace at Port Talbot represents an<br />

important example of Britain’s 20th century industrial history.<br />

Although no examples are preserved in Britain, steel-cased<br />

blast furnace structures have been retained elsewhere in<br />

Europe and the USA. At the time of writing the future of<br />

the blast furnace at Port Talbot is uncertain. However there<br />

is a case for either No 3 or the more modern No. 4 (1956)<br />

or No. 5 (1959) blast furnaces, should they become<br />

redundant in the future, to be retained as examples of this<br />

significant part of Britain’s industrial heritage.<br />

We would like to thank Corus and Parsons Brinkerhoff Ltd.<br />

for help and co-operation during this assessment.<br />

21

Annual Report <strong>2001</strong><br />

ULAS Staff <strong>2001</strong><br />

Directors<br />

Richard Buckley BA, MIFA<br />

Dr Patrick Clay BA, PhD, FSA, AMA, MIFA<br />

Finds Officers<br />

Nick Cooper BSc, Dip. Post-Ex.<br />

Patrick Marsden BA, MA<br />

22<br />

Finance Clerk<br />

Ethne Shannon<br />

Project Manager<br />

James Meek BA (from 1.12.<strong>2001</strong>)<br />

Project Officers<br />

Matthew Beamish MA, AIFA<br />

Lynden Cooper BA<br />

Neil Finn<br />

James Meek BA (until 1.12.<strong>2001</strong>)<br />

Susan Ripper BA<br />

Field Officers<br />

Vicki Priest BA<br />

John Thomas BA<br />

Environmental Officer<br />

Angela Monckton BSc, MIFA<br />

Senior Supervisors<br />

Jennifer Browning BA, MA (Animal Bone Analyst)<br />

Adrian Butler BSc, MA, AIFA (Geophysics)<br />

Simon Chapman BA, MA (Human Bone Analyst)<br />

Jon Coward<br />

Tim Higgins<br />

Supervisors<br />

Michael Derrick BSc, MA<br />

Tony Gnanaratnam BA, MA, PIFA<br />

Wayne Jarvis BA, MA<br />

Stephen Jones HND<br />

Dr. Roger Kipling, BA, MA, PhD<br />

Martin Shore<br />

Sally Anne Smith MA<br />

Archaeological Assistants<br />

Heidi Addison BA (Finds processing)<br />

Siobhan Brocklehurst BA<br />

Sandie Bush BA<br />

Andrew Hyam BA<br />

Keith Johnson<br />

Ian Reed BSc

University of Leicester Archaeological Services<br />

Michael Hawkes BA, MA<br />

Matthew Parker BA<br />

Clare Strachan BA<br />

John Tate BA<br />

ULAS Consultants and sub-contractors<br />

In addition to School of Archaeology and Ancient History<br />

staff, the following individuals and organisations<br />

have acted as consultants or sub-contractors to ULAS<br />

during <strong>2001</strong>.<br />

Dr. Simon Colcutt, Oxford Archaeological Associates<br />

Dr. Paul Courtney - Documentary Historian<br />

Debbie Sawday - Medieval Pottery<br />

David Smith - Architectural Historian<br />

Dr. Anne Woodward - Prehistoric Pottery<br />

ULAS Board of Management <strong>2001</strong><br />

Professor Marilyn Palmer BA, PhD, FSA (chair)<br />

Dr. Alan McWhirr BA, MA, PhD, FSA, MIFA<br />

(Secretary)<br />

Richard Buckley BA, MIFA<br />

Dr. Patrick Clay BA, PhD, FSA, AMA, MIFA<br />

Dr. Graham Morgan MPhil, PhD, FIIC, FSA<br />

Deirdre O’Sullivan BA, MPhil<br />

Dr. Jeremy Taylor BA, PhD<br />

Dr. Rob Young BA, PhD<br />

23

Annual Report <strong>2001</strong><br />

Publications and Conferences <strong>2001</strong><br />

M.Beamish, ‘Excavations at Willington, South Derbyshire.<br />

Interim Report’, Derbyshire Archaeological<br />

Journal 121, 1-18.<br />

M.Beamish and S.Ripper, ‘Burnt Mounds in the East<br />

Midlands’, Antiquity 75, 37-38.<br />

S. Chapman, ‘The human remains’ in R. Pollard ‘ An Iron<br />

Age inhumation from Rushey Mead, Leicester’<br />

Transactions of the Leicestershire Archaeological<br />

and Historical Society 76, 28-29 (20-35).<br />

P. Clay, ‘Leicestershire and Rutland in the First Millennium<br />

BC’. Transactions of the Leicestershire<br />

Archaeological and Historical Society 76, 1-18.<br />

L. Cooper. ‘The Glaston glutton and other strange beasts’.<br />

Rescue News 83, 1-3. Rescue: the British<br />

Archaeological Trust.<br />

L. Cooper (with A.G. Brown, C. R. Salisbury & D. N. Smith)<br />

‘Late Holocene channel changes of the Middle Trent:<br />

channel responses to a thousand-year flood record’,<br />

Geomorphology 39, 69-82.<br />

L. Cooper, (with R.M. Jacobi ), ‘Two Late Glacial finds<br />

from north-west Leicestershire’. Transactions of<br />

the Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical<br />

Society 75, 118-121.<br />

N. Finn ‘A ‘new’ cruck-framed building at Littlethorpe’.<br />

Transactions of the Leicestershire Archaeological<br />

and Historical Society 76, 121-4.<br />

‘An Iron Age inhumation from Rushey Mead,<br />

Leicester’. Transactions of the Leicestershire<br />

Archaeological and Historical Society 76, 29-31<br />

(20-35).<br />

R. Buckley continued as Hon. Editor Transactions of the<br />

Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical<br />

Society<br />

Conferences<br />

ULAS staff contributed to the following conferences:<br />

– 4th International Conference on Archaeological<br />

Prospection, Vienna, September <strong>2001</strong> (Poster session<br />

by A.Butler).<br />

– Community Archaeology Conference, University of<br />

Leicester (papers by M.Beamish, P. Clay, L.Cooper,<br />

N. Cooper and A.Monckton).<br />

– Neolithic Studies Group, Society of Antiquaries, London<br />

(paper by P.Clay).<br />

– Palaeolithic-Mesolithic day, The British Museum–<br />

(paper by L.Cooper).<br />

24<br />

A. Monckton, ‘The charred plant remains’ in R. Pollard

University of Leicester Archaeological Services<br />

Outreach <strong>2001</strong><br />

ULAS staff provided demonstrations, interviews, tours or lectures for the following groups and organisations:<br />

Abbey Park, Leicester. National Archaeology Day Site tours<br />

Appleby Heritage and Environment Movement<br />

BBC Radio Leicester<br />

Boston Local History Group<br />

Burton on Trent Natural History and Archaeological Society<br />

Charnwood Borough Council; Leicestershire Planning Officers meeting<br />

Council for British Archaeology Group 14: Reports meeting, Lincoln<br />

Council for British Archaeology Group 14: Reports meeting, Wing, Rutland<br />

Council for British Archaeology Group 14: Leicester Abbey and Castle tours<br />

De Montfort University School of Architecture, Leicester Castle<br />

Evington Centre Official Opening, Leicestershire and Rutland Healthcare<br />

East Midlands SMR Working Party – Research Framework Seminars<br />

Enderby Heritage Group<br />

Friends of Charnwood Museum<br />

Glaston Local History Group<br />

Great Easton Fieldworkers Group<br />

Leicester City Museums Public Lectures, Jewry Wall Museum<br />

Leicester City Museums Service, Leicester Castle tours<br />

Leicestershire Museums Arts and Records Service, Donington le Heath<br />

Museum ‘Romans Day’<br />

Leicester University, Life Long Learning: Archaeology Certificate Course Above: ULAS director Dr. Patrick Clay<br />

(left) and Peter Crane of Leicestershire<br />

Kirby Bellars Local History Group<br />

NHS Trust, present archaeological finds<br />

Melton Rotary Club<br />

to HRH The Duchess of Gloucester, who<br />

Ockbrook & Borrowash Archaeological & Historical Society<br />

opened the new Mental Health Hospital<br />

Peterborough Regional College (A-level Archaeology Course)<br />

at Leicester General. An excavation by<br />

Retford Archaeological Society<br />

ULAS had unearthed evidence of Iron<br />

Rutland County Museum: National Archaeology Day<br />

Age settlement and Roman farming on<br />

Sawley Historical Society<br />

the site.<br />

Sheffield Archaeological Society<br />

Sherwood Archaeological Society, Mansfield<br />

W.E.A. Barrow on Soar ‘Archaeology Now’ evening class<br />

W.E.A. Birstall ‘Hands On Archaeology’ and ‘Our Roman and Saxon Past’<br />

W.E.A. Leicester ‘Our Roman and Saxon Past’ evening class<br />

W.E.A. Rothley ‘Hands On Archaeology’ and ‘Our Roman and Saxon Past’ evening classes<br />

25

Annual Report <strong>2001</strong><br />

Archaeological Projects <strong>2001</strong><br />

Consultancies<br />

Alconbury Airfield, Cambridgeshire<br />

East Midlands SMR Working Party<br />

Kegworth, Fulcrum, Leicestershire<br />

Leicester Castle<br />

Loughborough (Coates Viyella Factory), Leicestershire<br />

Watermead Business Park, Syston, Leicestershire<br />

Desk-based assessments<br />

Anstey, Leicestershire<br />

Bardon, Leicestershire<br />

Cossington Brook, Leicestershire<br />

Cossington, Main Street, Leicestershire<br />

Earl Shilton, Leicestershire<br />

East Goscote, Leicestershire<br />

Hinckley, Leicestershire<br />

Leicester, Cank Street<br />

Leicester, Castle Street<br />

Leicester, Evington, High Street,<br />

Leicester, Mill Lane<br />

Leicester, Raw Dykes Road<br />

Leicester, Royal Infirmary<br />

Leicester, Rutland Street<br />

Leicester, St. Nicholas Circle<br />

Leicester, The Newark area<br />

Lockington-Hemington, Leicestershire<br />

Loughborough, Beacon Road, Leicestershire<br />

Loughborough, Park Grange, Leicestershire<br />

Melton Mowbray (Dalby Road), Leicestershire<br />

Melton Mowbray (King Street), Leicestershire<br />

Mountsorrel, Leicestershire<br />

Northampton, (Cannon Cinema)<br />

Nottingham, Bilborough College<br />

Nottingham, Blenheim Road, Bulwell<br />

Quorn, Leicestershire<br />

Quorn/Woodhouse, Leicestershire<br />

Port Talbot, Glamorgan<br />

Ratby, Leicestershire<br />

Rearsby Brook, Leicestershire<br />

Seaton, Rutland<br />

Shepshed (Fire Station), Leicestershire<br />

Sutton Bonington, Nottinghamshire<br />

Building Surveys<br />

Bradley, (Working Boats survey), West Midlands<br />

Hinckley, Regent Street, Leicestershire<br />

Leicester, Rutland Street<br />

Northampton, (Cannon Cinema)<br />

Northampton, (General Hospital)<br />

Ratby, Leicestershire<br />

Seagrave, Leicestershire<br />

Fieldwalking Surveys<br />

Wanlip (Hallam Fields), Leicestershire<br />

Geophysical Surveys<br />

Desford, Leicestershire<br />

Hatton, Derbyshire<br />

Husbands Bosworth, Leicestershire<br />

Leicester, Humberstone (Hamilton North)<br />

Hallaton, Leicestershire<br />

26

University of Leicester Archaeological Services<br />

Quorn/Woodhouse, Leicestershire<br />

Rearsby, Leicestershire<br />

Syston (Fosse Way North), Leicestershire<br />

Uppingham (The Beeches), Rutland<br />

Wanlip (Hallam Fields), Leicestershire<br />

Wanlip, Leicestershire<br />

Evaluations<br />

Anstey, Leicestershire<br />

Belvoir, (Belvoir Castle), Leicestershire<br />

Burton Lazars, Leicestershire<br />

Claybrooke Parva, Leicestershire<br />

Earl Shilton, Leicestershire<br />

Greatford, Lincolnshire<br />

Hallaton, Leicestershire<br />

Hatton, Derbyshire<br />

Husbands Bosworth, Leicestershire<br />

Ketton, Rutland<br />

Leicester, Leicester Abbey<br />

Leicester, Cank Street<br />

Leicester, Castle Street<br />

Leicester, Evington, High Street<br />

Leicester, Falconer Crescent<br />

Leicester, Great Central Street/Vaughan Way<br />

Leicester, Humberstone (Manor Farm)<br />

Leicester, Humberstone (Quakesick Spinney)<br />

Leicester, Mill Lane<br />

Leicester, Mowmacre<br />

Leicester, The Guildhall<br />

Lockington-Hemington (Warren Farm), Leicestershire<br />

Loughborough, The Rushes, Leicestershire<br />

Lutterworth (Mill Farm), Leicestershire<br />

Melton Mowbray (Burton Brook), Leicestershire<br />

Melton Mowbray (Dalby Road), Leicestershire<br />

Melton Mowbray (King Street), Leicestershire<br />

Ratby, Leicestershire<br />

Rothwell, Northamptonshire<br />

Shepshed, Leicestershire<br />

Stockerston, Leicestershire<br />

Sutton Bonington, Nottinghamshire<br />

Thorney, Peterborough<br />

Thurlaston, Leicestershire<br />

Uppingham (The Beeches), Rutland<br />

Walton on the Wolds, Leicestershire<br />

Willington, Derbyshire<br />

Excavations<br />

Claybrooke Parva, Leicestershire<br />

Cossington, Leicestershire<br />

Husbands Bosworth, Leicestershire<br />

Leicester, Humberstone (Manor Farm)<br />

Lutterworth (Mill Farm), Leicestershire<br />

Seagrave, Leicestershire<br />

Watching briefs<br />

Alcester, Warwickshire<br />

Allexton, Leicestershire<br />

Atherstone, Warwickshire<br />

Aston-Burbage, Leicestershire<br />

Ashby Magna, Leicestershire<br />

Ashwell, Rutland<br />

Birstall, Leicestershire<br />

Branston, Leicestershire<br />

Burbage (Sketchley Lane), Leicestershire<br />

Burton Overy, Leicestershire<br />

Burrough on the Hill, Leicestershire<br />

Claybrooke Parva, Leicestershire<br />

Clipsham, Rutland<br />

Desford (Peckleton Lane North), Leicestershire<br />

Drayton, Leicestershire<br />

Eaton, Leicestershire<br />