Jane Eyre as gothic novel Jan 25 - Page

Jane Eyre as gothic novel Jan 25 - Page

Jane Eyre as gothic novel Jan 25 - Page

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

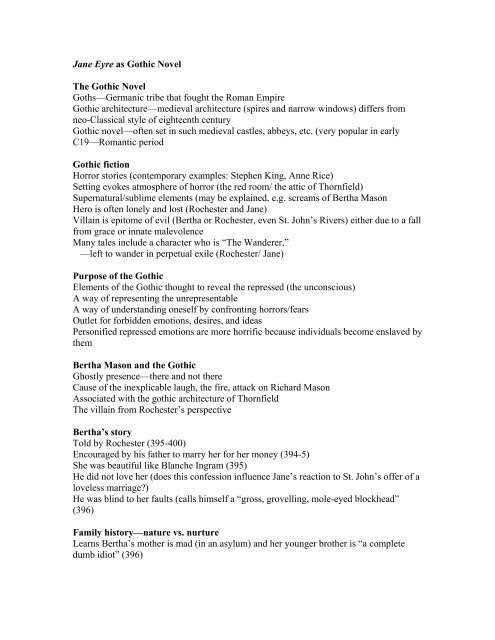

<strong><strong>Jan</strong>e</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>as</strong> Gothic Novel<br />

The Gothic Novel<br />

Goths—Germanic tribe that fought the Roman Empire<br />

Gothic architecture—medieval architecture (spires and narrow windows) differs from<br />

neo-Cl<strong>as</strong>sical style of eighteenth century<br />

Gothic <strong>novel</strong>—often set in such medieval c<strong>as</strong>tles, abbeys, etc. (very popular in early<br />

C19—Romantic period<br />

Gothic fiction<br />

Horror stories (contemporary examples: Stephen King, Anne Rice)<br />

Setting evokes atmosphere of horror (the red room/ the attic of Thornfield)<br />

Supernatural/sublime elements (may be explained, e.g. screams of Bertha M<strong>as</strong>on<br />

Hero is often lonely and lost (Rochester and <strong><strong>Jan</strong>e</strong>)<br />

Villain is epitome of evil (Bertha or Rochester, even St. John’s Rivers) either due to a fall<br />

from grace or innate malevolence<br />

Many tales include a character who is “The Wanderer,”<br />

—left to wander in perpetual exile (Rochester/ <strong><strong>Jan</strong>e</strong>)<br />

Purpose of the Gothic<br />

Elements of the Gothic thought to reveal the repressed (the unconscious)<br />

A way of representing the unrepresentable<br />

A way of understanding oneself by confronting horrors/fears<br />

Outlet for forbidden emotions, desires, and ide<strong>as</strong><br />

Personified repressed emotions are more horrific because individuals become enslaved by<br />

them<br />

Bertha M<strong>as</strong>on and the Gothic<br />

Ghostly presence—there and not there<br />

Cause of the inexplicable laugh, the fire, attack on Richard M<strong>as</strong>on<br />

Associated with the <strong>gothic</strong> architecture of Thornfield<br />

The villain from Rochester’s perspective<br />

Bertha’s story<br />

Told by Rochester (395-400)<br />

Encouraged by his father to marry her for her money (394-5)<br />

She w<strong>as</strong> beautiful like Blanche Ingram (395)<br />

He did not love her (does this confession influence <strong><strong>Jan</strong>e</strong>’s reaction to St. John’s offer of a<br />

loveless marriage?)<br />

He w<strong>as</strong> blind to her faults (calls himself a “gross, grovelling, mole-eyed blockhead”<br />

(396)<br />

Family history—nature vs. nurture<br />

Learns Bertha’s mother is mad (in an <strong>as</strong>ylum) and her younger brother is “a complete<br />

dumb idiot” (396)

Discovers that “her c<strong>as</strong>t of mind [is] common, low, narrow, and singularly incapable of<br />

being led to anything higher”<br />

Could not hold a conversation with her (396)<br />

Physiognomy: character can be read from facial characteristics—character a result of<br />

nature<br />

190: <strong><strong>Jan</strong>e</strong>’s description of Rochester<br />

198: Mrs Fairfax on nature: “it is his nature—and we can none of us help our nature”<br />

207: Rochester: “Nature meant me to be, on the whole, a good man”<br />

211: Rochester about <strong><strong>Jan</strong>e</strong>: “You are not naturally austere, any more than I am naturally<br />

vicious” (austere=harsh/stern or cold in manner or appearance)<br />

Bertha <strong>as</strong> Excess<br />

A “violent and unre<strong>as</strong>onable temper”<br />

“[I]ntemperate and unch<strong>as</strong>te” (397) –vices of drunkenness and promiscuity<br />

Implication that sex and alcohol lead to insanity (sexually transmitted dise<strong>as</strong>es such <strong>as</strong><br />

syphilis did lead to insanity)<br />

But suggestion is not that Bertha went insane because of a sexual dise<strong>as</strong>e, but that her<br />

excess sexual desires were a sign of her insanity and contributed to her degeneration<br />

Bertha and the moon<br />

Bertha <strong>as</strong>sociated with the blood-red moon (398)<br />

Moon <strong>as</strong>sociated with femaleness, menstruation<br />

Bertha’s madness is an excess of femaleness<br />

Full moon when Bertha attacks her brother (287)<br />

<strong><strong>Jan</strong>e</strong> describes her attacker <strong>as</strong> a “vampire” (371), also <strong>as</strong>sociated with a full moon<br />

Richard M<strong>as</strong>on bitten by a vampire: “She sucked the blood: she said she'd drain my<br />

heart” (294)<br />

In what ways is <strong><strong>Jan</strong>e</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> similar to Bertha M<strong>as</strong>on?<br />

Both women possess p<strong>as</strong>sion, anger, and sexuality<br />

These are more or less controlled in <strong><strong>Jan</strong>e</strong><br />

<strong><strong>Jan</strong>e</strong> must learn to restrain her p<strong>as</strong>sion<br />

In Bertha they are incre<strong>as</strong>ingly uncontrolled--excessive<br />

If <strong><strong>Jan</strong>e</strong> is prone to excess p<strong>as</strong>sion (<strong>as</strong> with John Reed, in the red room, tale to Helen) she<br />

may become like Bertha M<strong>as</strong>on<br />

Bertha representative of <strong><strong>Jan</strong>e</strong>’s repressed desires<br />

Bertha is <strong><strong>Jan</strong>e</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong>’s doppelganger (double)—ghostly counterpart<br />

Consider Rochester’s suggestion that <strong><strong>Jan</strong>e</strong> h<strong>as</strong> seen a ghost—“ghosts are usually pale”<br />

(371)<br />

<strong><strong>Jan</strong>e</strong> thinks it w<strong>as</strong> a vampire<br />

Bertha a “ghost” <strong>as</strong> <strong><strong>Jan</strong>e</strong> does not learn Bertha exists until her wedding day<br />

Expresses the anger <strong><strong>Jan</strong>e</strong> represses<br />

A monstrous version of <strong><strong>Jan</strong>e</strong>

Bertha’s madness unknown until her marriage<br />

<strong><strong>Jan</strong>e</strong> unaware of Bertha’s madness until her marriage<br />

Suggestion that marriage brings about the conditions that foster this “madness”<br />

Connection in the charades between marriage and madness—words “bride” and<br />

“Bridewell” (261-263)<br />

Female Gothic<br />

Female Gothic” (term originated by Ellen Moers) “to define a tradition of Gothic writing<br />

by women . . . that represents the female experience within domesticity <strong>as</strong> one of<br />

imprisonment, claustrophobia and terror”<br />

Repression/suppression (by marriage) gives rise to the monstrous<br />

Bertha confined by her family, marriage, and then in Thornfield<br />

Confinement in <strong><strong>Jan</strong>e</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong><br />

Gateshead<br />

<strong><strong>Jan</strong>e</strong> confined because of the weather<br />

Confined to the window seat because of John Reed<br />

Confined to the red room by Mrs Reed<br />

<strong><strong>Jan</strong>e</strong>’s confinement to the red room links to Bertha’s confinement<br />

<strong><strong>Jan</strong>e</strong> and Bertha—confined<br />

<strong><strong>Jan</strong>e</strong> sees herself <strong>as</strong> a ghost figure in the mirror (71)<br />

Sees Bertha <strong>as</strong> a ghost in the mirror on her wedding night (371)<br />

<strong><strong>Jan</strong>e</strong> “utter[s] a wild, involuntary cry” (74), echo <strong><strong>Jan</strong>e</strong>’s first hearing of Bertha (175)-corridor<br />

equated to that of Bluebeard’s c<strong>as</strong>tle<br />

Reference to Bluebeard's c<strong>as</strong>tle also plays with the entrapment in marriage theme<br />

Lowood<br />

Confined by the schedule<br />

Must be in a certain place at a certain time<br />

Confined to the grounds<br />

Can only walk in the courtyard or to the church<br />

Confined by the uniform—hair cannot even curl<br />

<strong><strong>Jan</strong>e</strong> and Bertha<br />

Madness and marriage<br />

Bertha—insane—loss of self<br />

Can no longer recognize oneself<br />

<strong><strong>Jan</strong>e</strong><br />

<strong><strong>Jan</strong>e</strong> fears marriage will be a loss of self<br />

During engagement she resists becoming an economic dependent<br />

When she tries on her wedding gown the image looks unfamiliar<br />

The name does not feel like her own.<br />

Also <strong><strong>Jan</strong>e</strong> is reluctance to let Rochester buy her an expensive wedding veil--the very veil<br />

that Bertha destroys

Visual imagery in <strong><strong>Jan</strong>e</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong><br />

Gothic h<strong>as</strong> a strong visual component<br />

<strong><strong>Jan</strong>e</strong>’s paintings, her many dreams, description of nature (and dreams) to Rochester<br />

Her initial interest in the pictures in the books in the Gateshead Library Bewick’s History<br />

of British Birds<br />

Engages with <strong>gothic</strong> imagery and with <strong><strong>Jan</strong>e</strong>’s desire not to be confined<br />

Appropriation of God<br />

Brocklehurst<br />

For social control and cl<strong>as</strong>s oppression<br />

How does St. John Rivers’ conception of God differ from Rochester’s?<br />

St. John: complex, not hypocritical--denying all sexuality, especially female sexuality<br />

(cf. St. Paul<br />

Consider how <strong><strong>Jan</strong>e</strong> feels after hearing one of his sermons (446-47)<br />

St. John’s God is not a loving God (any more than Brocklehurst’s is)<br />

St. John’s God is demanding—wants self-sacrifice, physical deprivation, denial of the<br />

body<br />

St. John h<strong>as</strong> “not yet found that peace of God which p<strong>as</strong>seth all understanding” (447)—in<br />

that he is like <strong><strong>Jan</strong>e</strong><br />

Rochester too comes to an understanding of God<br />

Once willing to defy God’s law and social law, to profane “Holy matrimony”<br />

At Ferndean he acknowledges the existence of God, “the hand of God in my doom” and<br />

he believes that <strong><strong>Jan</strong>e</strong> comes in answer to his prayer (she therefore can be seen to remain<br />

his good angel)<br />

Both note that God sees not <strong>as</strong> man sees (514, 549), though both are also claiming in<br />

these p<strong>as</strong>sages that they can see in the same way <strong>as</strong> God (they are little Gods)