I Henry IV

I Henry IV

I Henry IV

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

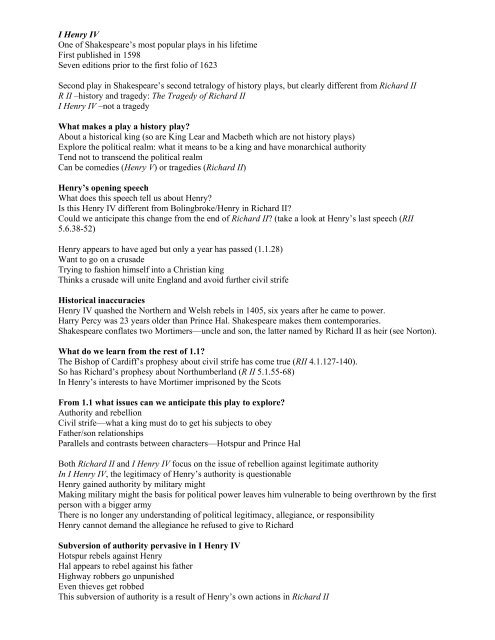

I <strong>Henry</strong> <strong>IV</strong>One of Shakespeare’s most popular plays in his lifetimeFirst published in 1598Seven editions prior to the first folio of 1623Second play in Shakespeare’s second tetralogy of history plays, but clearly different from Richard IIR II –history and tragedy: The Tragedy of Richard III <strong>Henry</strong> <strong>IV</strong> –not a tragedyWhat makes a play a history play?About a historical king (so are King Lear and Macbeth which are not history plays)Explore the political realm: what it means to be a king and have monarchical authorityTend not to transcend the political realmCan be comedies (<strong>Henry</strong> V) or tragedies (Richard II)<strong>Henry</strong>’s opening speechWhat does this speech tell us about <strong>Henry</strong>?Is this <strong>Henry</strong> <strong>IV</strong> different from Bolingbroke/<strong>Henry</strong> in Richard II?Could we anticipate this change from the end of Richard II? (take a look at <strong>Henry</strong>’s last speech (RII5.6.38-52)<strong>Henry</strong> appears to have aged but only a year has passed (1.1.28)Want to go on a crusadeTrying to fashion himself into a Christian kingThinks a crusade will unite England and avoid further civil strifeHistorical inaccuracies<strong>Henry</strong> <strong>IV</strong> quashed the Northern and Welsh rebels in 1405, six years after he came to power.Harry Percy was 23 years older than Prince Hal. Shakespeare makes them contemporaries.Shakespeare conflates two Mortimers—uncle and son, the latter named by Richard II as heir (see Norton).What do we learn from the rest of 1.1?The Bishop of Cardiff’s prophesy about civil strife has come true (RII 4.1.127-140).So has Richard’s prophesy about Northumberland (R II 5.1.55-68)In <strong>Henry</strong>’s interests to have Mortimer imprisoned by the ScotsFrom 1.1 what issues can we anticipate this play to explore?Authority and rebellionCivil strife—what a king must do to get his subjects to obeyFather/son relationshipsParallels and contrasts between characters—Hotspur and Prince HalBoth Richard II and I <strong>Henry</strong> <strong>IV</strong> focus on the issue of rebellion against legitimate authorityIn I <strong>Henry</strong> <strong>IV</strong>, the legitimacy of <strong>Henry</strong>’s authority is questionable<strong>Henry</strong> gained authority by military mightMaking military might the basis for political power leaves him vulnerable to being overthrown by the firstperson with a bigger armyThere is no longer any understanding of political legitimacy, allegiance, or responsibility<strong>Henry</strong> cannot demand the allegiance he refused to give to RichardSubversion of authority pervasive in I <strong>Henry</strong> <strong>IV</strong>Hotspur rebels against <strong>Henry</strong>Hal appears to rebel against his fatherHighway robbers go unpunishedEven thieves get robbedThis subversion of authority is a result of <strong>Henry</strong>’s own actions in Richard II

In I <strong>Henry</strong> <strong>IV</strong>, everyone acting out of self interestIn contrast to RII, the playworld in I <strong>Henry</strong> <strong>IV</strong> is expanded to includeThe courtMistress Quickly’s innThe rebel holdouts in Northumberland and WalesThese worlds come together through HalHe moves easily between the inn, court, and battlefieldShakespeare’s response to the criticsThe expanded playworld may be Shakespeare’s way of snubbing his nose at literary critics.Sir Philip Sidney criticized the mingling of kings and clowns on the English stage—he didn’t think itmade for good drama.Here Shakespeare has clowns (Falstaff) imitating a king and has king-to-be mixing with drunks andhighway robbers.The expanded playworld also allows Shakespeare to present other facets of early modern society.For example, the inn and the carriers indicate the trade activity in London at the time and the popularity ofimported wines and clothing.Glyndŵr’s castle and Hotspur’s castle reveal a particular view of Wales and the North as wild andbarbaric.How does 1.2 differ from 1.1?Shift in dramatic pacing—rapid first scene to slower paced second sceneTime irrelevant in this world compared to the importance of time at the courtShift in mood—from serious, sober tone to light-hearted humourShift in language—move to prose with the exception of Hal’s final speechHow does this “underworld” reflect the court world?Plots and subterfuge in both worlds (Robbery a parody of Percy’s plot)Messenger arrives that changes the plans of those presentCompare <strong>Henry</strong>’s view of his son to the way Falstaff treats HalConsider how Falstaff talks to Prince Hal:Hal, sweet wag, lad, mad wag, “the most comparative, rascalliest sweet young Prince”What is Prince Hal really like?Hal not interested in highway robbery, but not above goading the others onIs willing to trick FalstaffWhat does Hal’s final speech in 1.2 reveal about him?He is simply playing a roleWill be like the prodigal sonConsider sun image to that used by Richard in RII 3.2.33He is only friends with these people while it suits himSense of coldness in his personalityMachiavellian?MachiavellianThe term Machiavellian comes from Niccolo Machiavelli, a fifteenth-century Italian who wrote ThePrince.He challenged accepted ideas about how rulers should be virtuous, generous, and seek the loyalty andlove of their people, to argue that meanness and fear where useful methods by which to govern.Machiavelli is often noted as saying that the end justifies the means—this is actually a misinterpretationof what he says.

He does suggest that it is acceptable for a ruler to lie, cheat, or even murder to stay in office. He alsoemphasizes the need to appear virtuous even when one isn’t.In early modern English theatre the Machiavel is a character who puts his/her own interests above theusual moral restraints or needs of the society (for example, Aaron and Tamora, Don John, Bolingbroke).The Machiavel is often a source of social disorder.Typically, the Machiavel is:A good actorSkilled at manipulating peopleUses people’s own weaknesses, fears, and desires greed for his own endsSkilled with language: uses it to disguise rather than to communicateGood at listening to others and framing the right responseBoth <strong>Henry</strong> <strong>IV</strong> and Prince Hal show certain Machiavellian characteristicsKing <strong>Henry</strong>’s desire to go on a crusade can be considered a Machiavellian tactic—will make him lookgoodPrince Hal’s planned reformation is also such a tactic1.3: Enter HotspurWhat sense of <strong>Henry</strong> do we get in this scene?Appears capable of coping with the rebelsDemands their obedience<strong>Henry</strong> uses language to goad HotspurHas a good understanding of what is going on between Glyndŵr and MortimerWhat impression do we get of Hotspur?Tries to control himself in front of the kingBut hot-tempered, easily angered: “drunk with choler”Consider how Hotspur is treated (manipulated by) Worcester and Northumberland (Hotspur’s father)Northumberland later fails to support his son’s rebellionFamily loyalty lacking1.3.185-254Hotspur not showing his elders much respect—fails to listen to them (1.3.215-217)Notice how Hotspur talks about Richard II, “a sweet lovely rose” (1.3.173-4)—unrealistic image ofRichardCompare the way that Hotspur talks to his elders with the way that Prince Hal later talks to the king (3.2)Act 2: Robbery and counter robberyFocuses on robbery and counter-robbery with the exception of 2.42.4 presents Hotspur at home with his wifeInterruption emphasizes parallels between Hotspur’s plot and the robberySense of simultaneity—both things happening at the same timeNecessary interruption for stagingEnd of scene indicated by people leaving the stageUnusual for the same character to exit and enter immediately afterPermits a change of setting2.1: Humour of low charactersJokes about being bitten to death by fleas at the innNot being allowed a pot to piss inJokes about hanging—stock comic traitLow characters frequently joke about ways they may be punishedRoman comedy filled with slaves joking about being crucified

2.2 and 2.3: Tricking of FalstaffPure entertainment for Poins and HalTo hear Falstaff’s “incomprehensible lies” (1.3.165)Not about robbery, but about language/wit/deceitFalstaff made to sound grotesque—can’t even walk a few yards or get up from lying downGrotesque features also ascribed to Bardolph—his red nose in 2.5, 3.3Carnivalesque (Mikhail Bakhtin)2.4: Hotspur at homeWhat impression do we get of Hotspur from this scene?Opens with Hotspur reading a letter from someone who refuses to join his rebellionArgues with every phrase—even the unimportant ones (language instituting/becoming reality)No place in Hotspur’s military life for his wife, KateShe is “a banished woman” (2.4.33)“This is no world /To play with maumets and to tilt with lips” (2.4.83)Both play with language: ironic statements “I love thee not”Gender stereotypes: women inconstant, cannot keep secrets2.5: Back at the innLongest scene in the playEmphasizes the relationship between Hal and FalstaffFalstaff represents the world of saturnalia, perpetual holiday/anarchy (Twelfth Night)Hal only inhabits this world for a while (1.2.182-83)FalstaffDraws on a medieval Vice figure of irreverenceStock figure of the braggart warrior (Miles Gloriosus)Stage clown—poking fun at authority figures/ drunk/ bodily grotesqueHumour in Falstaff’s exaggeration about the robbery and his annoyance that Hal and Poins did not helphimHal encourages the exaggeration and then points out the logical fallacy of what Falstaff is sayingFalstaff unfazed by the others knowing the truth. Simply claims he knew them to be the thieves all alongHal and Falstaff enact the meeting of <strong>Henry</strong> and HalOffers a humorous contrast to the meeting of <strong>Henry</strong> and Hal that followsReveals the slippage (displacement) that occurs throughout the play—similar things happening in thedifferent playworlds—but their proximity to one another reveals different features in each episodeFalstaff as King <strong>Henry</strong>Parodies the rebels’ plans to act the part of the kingEmphasizes the incompatibility between the world of the inn and the court—Hal will not be able toinhabit both as kingFalstaff takes the opportunity to praise himself—humorous self-interest but also shows how such aposition of power can be used for self-interestPrince Hal as King <strong>Henry</strong>Much more kinglyScene becomes seriousCertain truth behind his attack on FalstaffFalstaff’s sounds plaintive: “Banish not him thy Harry’s company” (2.5.437)When Hal declares “I do; I will” (439) is he speaking as himself or his father?

Act 3: Three worlds3.1 The rebels (gaining strength)3.2 <strong>Henry</strong> <strong>IV</strong> and Prince Harry (Harry making promises)3.3 Falstaff (in decline)3.1: Rebels on the riseScene opens with anticipation: “promises,” “prosperous hope” (1-2)Plans (parallels with 1.1)More evidence of Hotspur’s hastiness—forgotten mapGlyndwr (story teller) irritates Hotspur because he talks about himself so muchPromise quickly deteriorates into squabbling: dividing the spoilsDivision of the land comes down to what one says (3.1.93-137)Hotspur focusing what is said/ how it is said/ not on reality (as in 2.4)Parallels between Worcester schooling Hotspur (3.1.173-185) and <strong>Henry</strong> <strong>IV</strong> schoolingPrince Harry in 3.2Hotspur not listeningHotspur akin to Falstaff –element of disorder—seeks to overturn orderBecause of his position, Hotspur is far more dangerous than Falstaff3.1: Rebels and wivesContrasting relationship between Mortimer and his wife and Hotspur and KateIssue of language as Mortimer and Glyndwr’s daughter do not speak the same language, yet heunderstands her (196-206)Hotspur not interested in listening to othersnot interested in hearing Kate—sees her as a sexual objectdoesn’t listen to Glyndwr’s daughter singRole of womenWomen associated with the rebels/underworldMistress QuicklyKate PercyGlyndwr’s daughterRebels linked with wives and daughters.Family connections show the vulnerability of the rebelsPassion in 3.1In 3.2—passion is diverted into passion to rule3.2: Father and son: Prince Harry’s apologyHarry apologizes, but notes how language can disguise reality: <strong>Henry</strong> <strong>IV</strong> may have heard tales aboutHarry that aren’t true<strong>Henry</strong> notes how he encouraged public loyalty—sign of his Machiavellian nature<strong>Henry</strong> suggests that Harry might fight for Hotspur (is he using reverse psychology here?)Read Prince Harry’s reply (3.2.129-159)He “promise[s]” and will “perform”Consider Bolingbroke’s “what I speak/ My body shall make good upon this earth” (RII 1.1.37-38)Suggests that Hotspur is his ticket to honourEchoes the legal language of 3.1Closing line of 3.2 “Advantage feeds him fat while men delay” leads into scene with Falstaff andBardolph

3.3: Falstaff in declineNegative aspects of Falstaff’s lies and disorderClaims that Mistress Quickly has robbed him—echo on “bond” of Harry’s speechPrince Harry notes that this is slander—has serious consequencesKnows what Falstaff had in his pocketFalstaff still unrepentant4.1: Rebels in declineScene opens with Hotspur and Douglas playing with wordsWho can flatter the other mostReceive the bad news (by letter) that Northumberland isn’t comingWordplay on idea of sicknessWorcester believes Northumberland’s absence will make the rebel cause look bad:“shows the ignorant a kind of fear/ Before not dreamt of” (4.1.74-5)Hotspur claims that his absence will make them look betterRebels hear of the king’s troops and that Glyndwr is not comingakin to Richard hearing of Bolingbroke’s troops and his own lack of supportVernon’s description of Prince Harry and Hotspur’s reaction (97-124)4.2: Falstaff’s soldiersFalstaff uses his position to make moneyAccepts bribes from those who do not want to go to battleHas gathered a company of poor men—not properly clothedConsiders them good enough for cannon fodderFalstaff’s callousness apparent—more distasteful than <strong>Henry</strong>’s Machiavellianism4.3: Rebel CampHotspur, Douglas, Worcester, and Vernon squabbling about whether to fight tonight or tomorrowDouglas and Hotspur keen to fight at the first opportunityNot good strategistsHotspur’s reply to Blunt’s offer of parley is a long list of complaints—huge exaggerations“Promise” and “pay” echoes Harry’s “promise” and “perform”Hotspur knows he cannot make this complaint to the king4.4: Foreshadowing of 2 <strong>Henry</strong> <strong>IV</strong>Another Machiavellian at work—the Archbishop of York—supported the rebels but now writing to “otherfriends” just in case the rebels are defeated5.1: The King’s CampScene opens with the idea that the weather reflects the battle to comeThe sun looks “blood[y]”The wind “Foretells a tempest and a blust’ring day”Worcester and Vernon arrive to parleyFalstaff’s humour not welcomeWorcester repeats Hotspur’s complaints—but in more careful termsReminding <strong>Henry</strong> that they were the first to pledge allegiance to himPrince Harry offers to fight Hotspur in single combatEcho of what Aumerle and Bolingbroke were supposed to do in RIIWorcester does not tell HotspurWould leave him and the others vulnerable to later attack by the king

5.2: Battle declaredWorcester only tells Hotspur of Prince Harry’s challenge after Douglas has gone to declare that the rebelswill do battle against the kingHotspur fails to realize how he has been manipulatedHotspur again shows his hastiness by not reading the lettersPrevious letters only brought bad news5.3: BattleContrast between Blunt and Falstaff explicitBoth gentlemen of the same rankBlunt fighting in disguise as the kingFalstaff plays dead rather than fightIrony of <strong>Henry</strong> having others dressed like himAny noble can play a kingmetatheatric statement about character and costume5.4: The meeting of Harry and HotspurBattle not all one-sidedHarry injured but refuses to stop fightingWhen Hotspur and Harry meet, Hotspur insults Prince Harry by calling him Harry Monmouth (5.4.58)Harry has enough respect to cover Hotspur’s face after he is deadWhat are the differences between Harry and Hotspur?Falstaff disgustsPrince Harry sees Falstaff, thinks he is dead—would only miss Falstaff if he were vain (as vain asFalstaff)Falstaff’s act of stabbing Hotspur—ridiculousFalstaff no longer funny, disgustingHis jokes have no place on the battlefield5.5: ResolutionWorcester and Vernon to be executed, Douglas captured, Hotspur deadFinal speech—chasing down the rebels—indication of II <strong>Henry</strong> <strong>IV</strong>—picks up where I <strong>Henry</strong> <strong>IV</strong> ends.HonourTheme also apparent in Richard II and Titus AndronicusIs a different concept of honour presented here?How do these ideas of honour fit with the idea of a Machiavellian king?Varying views of honour1. Hotspur 1.3.79, 192-2062. <strong>Henry</strong> <strong>IV</strong> on Hotspur’s “honour” 3.2.93-1173. Harry on Hotspur’s honour 3.2.129-152, 5.4.70-724. Douglas 4.1.10-124. Vernon 4.3.7-124. Blunt 5.3.2-35. Falstaff 5.1.129-39; 5.3.30-37; 5.5.134-36