You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Number 73<br />

Summer 2014<br />

£4.50<br />

Lew Welch<br />

John Wieners<br />

Billy Burroughs<br />

Jack Kerouac<br />

Allen Ginsberg<br />

Robinson Jeffers<br />

Douglas Woolf<br />

Robert Duncan<br />

Joyce Johnson on<br />

Jack Kerouac’s<br />

Half-American Life<br />

..........<br />

Allen Ginsberg on<br />

Kerouac

John Clellon Holmes (pictured here in 1949) died<br />

in 1988. Novelist and essayist, he was a great New<br />

Yor<br />

ork friend of Jack Ker<br />

erouac, a writer and companion<br />

that Kerouac stuck with perhaps the longest of all his<br />

friends.<br />

Clellon Holmes published novels such as Go, Get<br />

Home Free, The Horn and also a series of essays in<br />

various collections through the Univ<br />

niversity of<br />

Arkansas Press. His Ker<br />

erouac eulogy, Gone in October<br />

John Clellon Holmes (pictured here in 1949) died<br />

is widely regarded as one of the very best Kerouac<br />

inJohn Clellon Holmes (pictured here in 1949) died<br />

tributes. Ann and Sam Charters published a<br />

in 1988. Novelist and essayist, he was a great New<br />

biography of Holmes<br />

Brother Souls in 2010. Liz Von<br />

Yor<br />

ork friend of Jack Ker<br />

erouac, a writer and companion<br />

Vogt, John<br />

ohn’s s younger sister, , is also a novelist.<br />

that Kerouac stuck with perhaps the longest of all his<br />

friends.<br />

Clellon Holmes published novels such as Go, Get<br />

Home Free, The Horn and also a series of essays in<br />

various collections through the Univ<br />

niversity of<br />

Arkansas Press. His Ker<br />

erouac eulogy, Gone in October<br />

is widely regarded as one of the very best Kerouac<br />

tributes. Ann and Sam Charters published a<br />

biography of Holmes Brother Souls in 2010. Liz Von<br />

Vogt, John<br />

ohn’s s younger sister, , is also a novelist. 1988. Novelist and essayist, he was a great New<br />

Yor<br />

ork friend of Jack Ker<br />

erouac, a writer and companion<br />

that Kerouac stuck with perhaps the longest of all his<br />

friends.<br />

Clellon Holmes published novels such as Go, Get<br />

Home Free, The Horn and also a series of essays in<br />

various collections through the Univ<br />

niversity of<br />

Arkansas Press. ess. His is Ker<br />

erouac eulogy, Gone one in October<br />

is widely regarded as one of the very best Kerouac<br />

tributes. Ann and Sam Charters published a<br />

biography of Holmes Brother Souls in 2010. Liz Von<br />

Vogt, John<br />

ohn’s s younger sister, , is also a novelist.J<br />

elist.John Clellon Holmes (pictured ed here e in 1949)<br />

died<br />

in 1988. Novelist and essayist, he was a great New<br />

Yor<br />

ork k friend of Jack Ker<br />

erouac, a writer and companion<br />

that Kerouac stuck with perhaps the longest of all his<br />

friends.<br />

Clellon Holmes published novels such as Go, Get<br />

Home Free, The Horn and also a series of essays in<br />

various collections through the Univ<br />

niversity of<br />

Arkansas Press. ess. His is Ker<br />

erouac eulogy, Gone one in October<br />

is widely regarded as one of the very best Kerouac<br />

tributes. Ann and Sam Charters published a<br />

biography of Holmes Brother Souls in 2010. Liz Von<br />

on<br />

Vogt, John<br />

ohn’s s younger sister, , is also a novelist.

Number 73<br />

Summer 2014<br />

Editor<br />

ditor...Kevin Ring<br />

Deputy Editor<br />

ditor...Jim Burns<br />

Beat Scene in America...<br />

Richard Miller, 1801 D Spruce<br />

Street, Berkeley, California<br />

94709, USA.<br />

Resear<br />

esearch<br />

ch...Pauline Reeves & Erin<br />

Ring<br />

Layout...Scarlet Letters<br />

Contributors this issue<br />

Eric Baizer, Jim Burns, Colin<br />

Cooper, William Corbett, Brian<br />

Dalton, Reywas Divad, Lee<br />

Harwood, Joyce Johnson, Carl<br />

Landauer, Kevin L. Mills, Richard<br />

Peabody, Dawn Swoop, Stephen<br />

Vincent, Eddie Woods, Edwin<br />

Forrest Ward, Lewis Warsh, John<br />

Wieners<br />

FIRST WORDS<br />

Looking at a photograph of Lewis<br />

Warsh, Bill Corbett, Lee Harwood<br />

and John Wieners in the fairly<br />

recent issue of Mimeo/Mimeo -<br />

taken in 1972 on a winter day at<br />

Walden Pond, I got intrigued.<br />

Wanted to know more. Through<br />

Jim Burns I managed to contact<br />

Lee Harwood and Bill Corbett.<br />

And then Lewis Warsh. There are<br />

little stories, history at every turn.<br />

The kind of history I enjoy and<br />

hopefully you do too. Certainly, if<br />

I pressed them there would be<br />

untold history with them all.<br />

Naturally the aim is to bring you<br />

fresh aspects, but the back stories<br />

exist and wait to be uncovered. So<br />

many crossroads to go to at<br />

midnight, so many connections.<br />

Enjoy this issue. A special edition<br />

next time. More on that in due<br />

course. As ever, tell your friends.<br />

Kevin Ring<br />

Beat Scene, 27 Court Leet,<br />

Binley Woods, Near Coventry,<br />

England CV3 2JQ<br />

Telephone 02476-543604<br />

Email<br />

kev@beatscene.freeserve.co.uk<br />

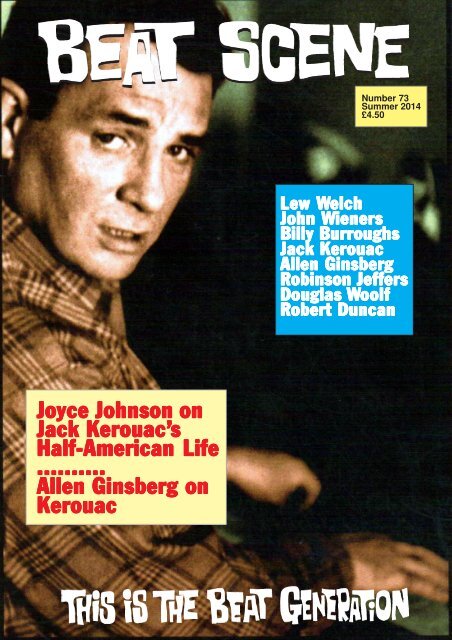

Front cover image of Jack Kerouac<br />

taken in 1963. Back cover image<br />

Joyce Johnson’s In the Night Cafe, a<br />

novel published in 1989 by<br />

Washington Square Press.<br />

- For Beat Souls, Dharma Bums, everywhere -<br />

4....Boston Eagles...John Wieners, Lee Harwood, Lewis Warsh, Bill<br />

Corbett...a photograph, Walden Pond, 1972<br />

6...Gesamthunstw<br />

esamthunstwer<br />

erk in a Vitrine<br />

itrine...Robert Duncan, Jess and Friends<br />

by Carl Landauer<br />

11...Bill Burr<br />

urroughs in Amsterdam<br />

by Eddie Woods<br />

14...A Half-American<br />

Writer<br />

...Joyce Johnson - a personal take on<br />

Kerouac’s sometimes alienation in America<br />

20...Really Lost Books ...Fade Out by Douglas<br />

Woolf<br />

oolf...by Kevin<br />

Ring<br />

22...The Blowtop...an Early Beat book? by Jim Burns<br />

24...Jeffers Is s My God<br />

....Kevin L. Mills looks at one of Bukowski’s<br />

big influences<br />

28...Ginsberg on Ker<br />

erouac<br />

ouac...an interview by Richard Peabody, Reywas<br />

Divad and Eric Baizer<br />

34...Le<br />

Lew Welch: A Journal of Remembrance<br />

by Stephen Vincent<br />

42...Write rite A Madder Letter if You ou Can...Jack Kerouac and Ed White<br />

the letters - by Kevin Ring<br />

47...Billy illy Burr<br />

urroughs<br />

oughs’ ’ Prediction<br />

....a curious remembrance by Edwin<br />

Forrest Ward<br />

50...The Beat eat Scene Revie<br />

eview w Section<br />

ection...Robert Creeley, Jack Kerouac,<br />

Amiri Baraka, Ed Dorn, Jim Burns, Neeli Cherkovski, Boxed Beats,<br />

the Garden of Eros<br />

William Burroughs....<br />

Eddie Woods provides a<br />

first hand account of him<br />

in Amsterdam. Burroughs<br />

obviously thought a lot of<br />

Europe, living in London<br />

for prolonged periods, the<br />

Beat Hotel in Paris, his<br />

regular and hugely<br />

popular readings in<br />

Germany, Netherlands -<br />

there is nothing better<br />

than a personal, close up<br />

account. A young<br />

Burroughs here - Woods<br />

encounters him in the last<br />

days. Is this the face of a<br />

sheep killing dog?

Boston Eagles<br />

John Wieners, Lee Harwood,<br />

Lewis Warsh, William Corbett<br />

interviews by Kevin Ring<br />

With the help of writer Iain Sinclair I was able<br />

to contact English poet Lee Harwood who lives on<br />

England’s South Coast. I wanted to ask Lee about a<br />

photograph I’d seen in The Lewis Warsh issue of the<br />

American small press magazine Mimeo/Mimeo,<br />

published by James Birmingham and Kyle Schlesinger.<br />

The photo dates from 1972 and features Lee<br />

Harwood, Lewis Warsh, Bill Corbett and the late John<br />

Wieners. As you can see, it captures Wieners in a<br />

seemingly positive frame of mind. The picture is<br />

taken at Walden Pond. It is a winter’s day, I’m led to<br />

believe. Intrigued, I asked Lee Harwood about his<br />

recollections of the day the picture was taken by<br />

Judith Walker. (Lee Harwood’s second wife). But, let<br />

Lee Harwood relate his recollections, “It was in the<br />

winter of 1972/73. From left to right it’s John<br />

Wieners, me, Lewis Warsh and William Corbett.<br />

We’re standing by a frozen Walden Pond, Massachusetts.<br />

I remember John W had a gold lame jacket. At<br />

that time Warsh, Corbett and I edited a “little mag”<br />

called THE BOSTON EAGLE and included quite a<br />

bit of John Wieners’ poetry in it. We were all living in<br />

Boston then.<br />

Lewis and I used to go round and visit John at<br />

his apartment at 44 Joy Street, Boston. He served us<br />

with champagne and chocolate peppermint cremes on<br />

one occasion! He was a very dear and gentle man, but<br />

also subject to bouts of distressing mental illness.<br />

When he came out of hospital he was fine, but then<br />

he used to slowly go downhill. He organised some<br />

really good things, such as a sort of free open university<br />

at the Stone Soup Gallery where various people,<br />

mainly poets, such as Warsh and me, gave talks and<br />

readings of poets like O’Hara, Ashbery, etc. I think<br />

John W talked about Olson. He also co-edited, with<br />

Jack Powers, in 1973 an anthology/magazine titled<br />

Stone Soup Poetry. The gallery was what you might now<br />

call “left wing,” though at that time there was a lot of<br />

radical thinking and demonstrations going on in the<br />

USA.<br />

That early (Wieners) book, The Hotel Wentley<br />

Poems, just bowled me over when I first read it and<br />

still does. The power and emotion and tenderness of<br />

those poems is, for me, quite exceptional when<br />

compared with a lot of the Beat poets.”<br />

Talking to Lee Harwood let me to both<br />

William Corbett and Lewis Warsh. Both remembered<br />

the time well and gave me a few of their memories.<br />

Bill Corbett: Here’s the photo I have on my<br />

wall. There is at least one other with John resting his<br />

arm against a tree and me in the background.<br />

Were the photo in color you would see that the light<br />

patches on John’s jacket are gold lame. There must be<br />

an accent there! I don’t remember why we settled on<br />

Walden Pond except that it’s such an obvious literary<br />

landmark. It was an unremarkable afternoon but for<br />

the photo.<br />

I asked Bill Corbett why were all four of you<br />

together that day by the pond?<br />

Bill Corbett: Lee, Lewis and I had started the mimeo<br />

magazine The Boston Eagle. One of our reasons was to<br />

feature John’s work. We wanted a photo of the editors<br />

and John for the back cover thus the trip to Walden<br />

Pond. The magazine was the first, and one of a very<br />

few, mimeo mags published in Boston. Lewis, who<br />

had come from NYC to live in Cambridge, came up<br />

with the idea. The magazine lasted three issues. I<br />

doubt that I have a single copy.<br />

From Bill Corbett, I spoke to Lewis Warsh,<br />

with whom I’ve had fleeting contact with in the past.<br />

He features on the front cover of Beat Scene 51 with<br />

Anne Waldman. I asked him - Lee Harwood talks of<br />

you and he going to Joy Street. Peppermint cremes<br />

and champagne. Stone Soup Gallery, The Boston<br />

Eagle, etc. What can you recall of the photo?<br />

Lewis Warsh: Lee Harwood and I first met in<br />

the mid-1960s in New York, and Angel Hair Books,<br />

which I was co-editing with Anne Waldman, published<br />

his book The Man With Blue Eyes in 1967. In<br />

4

fall 1972 I moved from California to Cambridge,<br />

Ma. with Mushka Kochan, my partner at the time.<br />

Soon after I arrived, I met John Wieners for a drink<br />

in a bar near Harvard Square. I had also known John<br />

in the late 60s, and had worked on publishing two of<br />

his books, Asylum Poems and Hotels. It was at the bar<br />

that I first met Bill Corbett, and he told me that Lee<br />

was in Boston. Lee and I connected soon after and we<br />

all had dinner at Bill and Beverly Corbett’s big house<br />

at 9 Columbus Square. It wasn’t long after that we<br />

decided to edit a magazine together, The Boston Eagle.<br />

The first issue was just the four of us: Bill, Lee, John<br />

and myself. I think we must have gone out to Walden<br />

Pond with the idea of taking a photo for the magazine—it<br />

appeared on the back cover of the first issue.<br />

Jude Walker was the photographer. We went on to<br />

publish three issues of the magazine, before we<br />

dispersed: I went to New York, and Lee, I believe,<br />

back to England.<br />

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<br />

Lewis Warsh, speaking a few years ago<br />

remembered Sun & Moon Press, Los Angeles<br />

publishing The Journal of John Wieners is to be called<br />

707 Scott Street for Billie Holiday 1959. ‘ln 1972,<br />

William Corbett and I visited John in his apartment<br />

at 44 Joy Street in Boston with the hope of getting<br />

poems from him for our new magazine (edited with<br />

Lee Harwood), The Boston Eagle. I remember John<br />

opening a trunk filled with ledger-sized journals with<br />

old-fashioned marble covers. “I’d love to read them<br />

someday,” I said, thinking out loud, but Wieners<br />

caught the genuine interest in my tone and presented<br />

one to me. [. . .]<br />

When I was finished [transcribing] I had 77<br />

manuscript pages, a book. On the inside cover of the<br />

ledger there was the title: 707 Scott Street, for Billie<br />

Holliday. I published a few pages of the journal in an<br />

issue of The World, the literary magazine of the Poetry<br />

Project (an issue devoted to autobiographical writing<br />

which I was guest-editing); then, for almost twenty<br />

years, the transcript of the journal disappeared. It was<br />

the interest of the poet Peter Gizzi who had heard<br />

that such a journal existed, that made me go<br />

searching for it. I never presented John with a<br />

finished copy of the transcript, though I do<br />

remember visiting him again and returning the<br />

original, not that it would have mattered (or so he led<br />

me to believe) whether I’d kept it or not.’<br />

A few extracts from Wieners’ diaries were<br />

published.......<br />

26 July 1958<br />

‘On the road again. America<br />

does not change. Nor do we,<br />

Olson says. We only reveal<br />

more of ourselves. Riding in<br />

the car with all the windows<br />

open. How can I rise to the<br />

events of our lives. I am a<br />

shrew and nagging bitch as<br />

my mother was. I am filled<br />

with doubt and too passive. I<br />

go where I am told.<br />

Anywhere. Take pleasure in<br />

doing what I am told. There is<br />

no comfort in Nature or God<br />

except for the weak. It is my<br />

fellow men that deliver me<br />

my life. Otherwise I wrap up<br />

in myself like an evening<br />

primrose in the sun. Nature<br />

is good for analogy. We think<br />

we learn lessons from her<br />

but she deserts us at the<br />

moment of action. That is<br />

why we remain savages.<br />

Underneath. And our civilization remains a jungle. Live it at<br />

night and see.<br />

But traveling on the road to Sausalito, San Francisco<br />

then Big Sur, I see how much the earth still surrounds us.<br />

Willow Road juts out in my memory. Mission San Rafael<br />

Archangel. Redwood Highway. Where man is going now, who<br />

knows. The earth no longer need be his home. Maybe this<br />

means the end of the old world. And man, on the minutest of<br />

planets may and can range thru all of space. To the very<br />

frontiers, limits, barriers of outer worlds. Lucky Drive. End<br />

construction project. With what frightening speed we move<br />

ahead. This must be necessary: Paradise Drive. The children<br />

are quieting down now. The witch drives her old Chevrolet, her<br />

long black hair blowing out the window.’<br />

5

Gesamtkunstwerk<br />

in a Vitrine<br />

Robert Duncan, Jess,<br />

and Friends<br />

by Carl Landauer<br />

T<br />

he exhibition, An Opening of the Field: Jess,<br />

Robert Duncan and Their Circle, curated by Michael<br />

Duncan and Christopher Wagstaff, includes a film<br />

that tours Jess and Duncan’s Victorian home at 3267<br />

Twentieth Street in San Francisco, starting with the<br />

entry hall and winding through all the rooms until you<br />

get to the third storey marked by the sloped roof of<br />

the house. The tour is essentially a microcosm of the<br />

exhibition because it encapsulates their artistic lives<br />

and so many of the people close to them. The front<br />

parlor with its stained glass includes a pen drawing by<br />

Jess, a profile drawing of Wallace Berman (the<br />

assemblage and collagist who published Semina, which<br />

would include visual and literary work by Philip<br />

Lamantia, Michael McClure, and Artaud in addition<br />

to Duncan and Jess), a piece of folded dollar bills by<br />

Dean Stockwell coiling more like one of Berman’s<br />

kabala letters than a snake, and a whole corner<br />

devoted to George Herms, one of the central figures<br />

of California assemblage. The music room, with the<br />

couple’s classical collection, is also full of the art of<br />

friends, including a wonderful baguette and coffee-pot<br />

painting by Lyn Brockway, one of the standouts of the<br />

show and an artist who should get more attention, as<br />

well as art that simply made an impact on them,<br />

including a print by the great art nouveau poster<br />

designer Alphonse Mucha and a William Blake<br />

reproduction. The hallway and the stairwell include a<br />

fantastic gray oil painting by Edward Corbett, Jess’s<br />

teacher at the California School of Fine Arts (now the<br />

San Francisco Art Institute) and one of the leading<br />

figures of the San Francisco Abstract Expressionism<br />

that exploded out of the school, along with a couple<br />

of Bruce Conner works, and a colorful painting by<br />

their friend, Jack Boyce.<br />

Jess’s studio resonates with the iconography<br />

of his “Paste-Ups,” his famous collages, with files of<br />

sorted images cut out of magazines and scientific<br />

books and carefully labeled, so that one box lists<br />

“Forms” and then subsections on “spheroid,”<br />

balloon,” “sphere,” “knob,” “egg,” an “lens.” Another<br />

includes “bigot,” “police – prison – execution,”<br />

“rebel-terrorist,” and “militarist.” And, significantly,<br />

there is the “working board” for his multi-decade<br />

collage, Narkissos. Their bedroom is full of works Jess<br />

and Duncan loved, including a dramatic, primitive<br />

sculpture of a head by their friend Miriam Hoffman,<br />

whose works dominate the first exhibition at the King<br />

Ubu Gallery that the couple opened for a year with<br />

their friend Harry Jacobus.<br />

The top floor includes the “Gertrude Stein<br />

Room,” the “French Room,” and Duncan’s office<br />

with its tacked-up iconic photos of Sigmund Freud,<br />

Ezra Pound, Virginia Woolf, as well as poets Charles<br />

Olson, Robert Creeley, and Jack Spicer (Spicer<br />

despite their decades-long quarrel). There are books<br />

throughout, including camera pans of the collection<br />

of original L. Frank Baum books, whose Oz series<br />

6

Robert Duncan, Jess, and Friends<br />

Duncan and Jess loved to read and re-read, and the<br />

large letters “H.D.” stick out in the pan of the<br />

bookcase in the Gertrude Stein Room simply because<br />

of the size of the lettering and reminds us of Duncan’s<br />

long, never-completed book on HD. For this we can<br />

turn to Lisa Jarnot’s biography of Duncan, which<br />

gives a tour of the couple’s library including the<br />

science books with its substantial collection of books<br />

by and about Darwin; a room full of books by a range<br />

of classical authors, like Ovid and Homer, as well as a<br />

Freud collection and books by a favorite philosopher,<br />

Alfred North Whitehead; a wide range<br />

of children’s books; the large collection<br />

of Joyce and Gertrude Stein in<br />

Gertrude Stein Room, and the<br />

foreign-language books of the central<br />

kabalistic text, the Zohar, in the<br />

“French Room.” It is well known that<br />

Duncan’s letters, interviews, and<br />

lectures – along with his conversation<br />

– are packed with a vast array of<br />

authors. There’s little surprise about<br />

his in-depth reading of the Western<br />

tradition, as well as his twentiethcentury<br />

forebears, such as Yeats,<br />

Pound, Williams, Louis Zukofsky,<br />

Rexroth, Patchen, D.H. Lawrence,<br />

H.D., Anaïs Nin, Dylan Thomas, and<br />

Henry Miller, only the way he read<br />

them and the obsessiveness with<br />

which he read and wrote about some<br />

like H.D. There is also his long<br />

reading of anarchist writers, so that early letters to<br />

Pauline Kael include lists of anarchist books he was<br />

trying to obtain. There are also endless references to<br />

philosophers and social scientists from Emile<br />

Durkheim to Arnold Toynbee, and from the<br />

philosopher Ernst Cassirer to Herbert Marcuse, who’s<br />

Eros and Civilization was part of the background<br />

reading on the Narcissus myth for Jess’s enormous<br />

collage project. And we are often told about Jess and<br />

Duncan’s shared love of fairy-tales and children’s<br />

literature, endlessly reading the fairy-tale writings of<br />

George MacDonald, the science fiction of J.L. Lloyd,<br />

C.S. Lewis, and J.R. Tolkien along with constant<br />

frame of the Oz books. But of particular interest was<br />

the oft-cited fact that Jess and Duncan – before they<br />

met each other – became intense readers not just of<br />

James Joyce but in particular of Joyce’s nearly<br />

unreadable Finnegan’s Wake with its non-stop allusions<br />

and puns, and puns making illusions. Finnegans Wake<br />

is just one, but perhaps a particularly illuminating<br />

touchstone for the work of both men.<br />

Similarly, Duncan was deeply invested in the<br />

visual artistic background of Jess’s work and not only<br />

by having given Jess an original copy of Max Ernst’s<br />

Surrealist collage book, Une semaine de bonté, as a<br />

birthday present in 1952, which became so important<br />

to the aesthetics of Jess’s “Paste-Ups.” He traces Jess’s<br />

work in a “tradition” leading back to Hieronymous<br />

Bosch, and including artists like Henry Fuseli,<br />

William Blake, Albert Pinkham Ryder, and Odilon<br />

Redon. Even Jess’s teachers from the California<br />

School of Fine Arts, Edward Corbett and Hassel<br />

Smith, make appearances in Duncan’s poetry. It was,<br />

indeed, the immense impact of Clyfford Still’s show<br />

at the artist-run Metart Gallery in 1950 that Duncan<br />

attributed to his not following through with plans to<br />

go to Europe but rather to stay in San Francisco,<br />

where obviously important things were happening.<br />

At the core of An Opening of the Field is an<br />

interdisciplinary collaboration. That collaboration<br />

only starts with the pairing of Jess’s illustrations for<br />

Duncan’s poetry, as in the Duncan’s book of poems,<br />

Caesar’s Gate in 1955. Jess illustrated a children’s<br />

book written by Duncan, The Cat and the Blackbird,<br />

in the 1950s published by White Rabbit Press in<br />

1967, as well as illustrations for Michael McClure’s<br />

children’s book for his daughter, The Boobus and the<br />

Bunnyduck, in 1958. And Jess created cover art for<br />

numerous friends’ books, like Michael Davidson’s The<br />

Mutabilities & Fould Papers and Lynn Lonidier’s A<br />

Lesbian Estate: Poems 1970-1973. Significantly, he<br />

contributed art reproduced in a wide range of little<br />

magazines by friends of the couple, such as a comic<br />

7<br />

Robert Duncan by Jess

Robert Duncan, Jess, and Friends<br />

for Jack Spicer’s mimeographed J, and a cover for the<br />

mimeographed Floating Bear created by Diane di<br />

Prima and LeRoi Jones. Even Duncan got into the<br />

part, writing text in his own hand in Jess’s work and<br />

even creating the cartoonish colophon bunny rabbit<br />

used for the White Rabbit Press – as well as writing<br />

numerous essays for exhibitions for Jess, Herms,<br />

Berman and others. And it was Berman’s photograph<br />

of McClure with a lion mane and fur glued to his face<br />

that graced the cover of Ghost Tantras. These<br />

collaborations in their original versions are exactly the<br />

sorts of ephemera that fill the vitrine space of the<br />

exhibition. But the exhibition, the accompanying<br />

catalog, and the two men’s lives – along with those of<br />

their friends – is filled with a much more important<br />

form of collaboration, an important interdisciplinary<br />

symbiosis, or rather multibiosis, of art forms and<br />

media.<br />

Film was also a critical part of this<br />

multibiosis. Pauline Kael – best known for her<br />

decades as the doyenne of film criticism at The New<br />

Yorker – was a close friend of Duncan’s starting as an<br />

undergraduate at Berkeley. In 1955 she introduced<br />

European films as well as pairing unlikely films at the<br />

Cinema Guild and Studio on Berkeley’s Telegraph<br />

Avenue, and it was natural that Jess produced posters<br />

and flyers, such as, for her showings of Jean Cocteau’s<br />

Orpheus and Jean Renoir’s The Golden Coach. One of<br />

the key elements in the development of the art film in<br />

the San Francisco Bay Area was the creation in 1946<br />

of the Art in Cinema series at the San Francisco<br />

Museum (which would last for nine years) by Frank<br />

Stauffacher under the museum’s pioneering director,<br />

Grace McCann Morley, who organized the first solo<br />

museum shows to numerous Abstract Expressionists<br />

from San Francisco (Jess’s teachers) and New York,<br />

including Jackson Pollock. So it is very much part of<br />

the Jess-Duncan story that James Broughton, the poet<br />

and filmmaker (also Pauline Kael’s lover who had a<br />

child with her) met with Duncan, Jess, Madeline<br />

Gleason, Even Triem, and Helen Adam in an ongoing<br />

poetry group as the selfproclaimed<br />

“Maidens,”<br />

had the premier of his<br />

short film made with<br />

painter/photographer<br />

Sidney Peterson The<br />

Potted Palm in the first<br />

year of the Art in<br />

Cinema series. If Jess<br />

and Duncan rented<br />

Broughton’s house while<br />

he was away from San<br />

Francisco, the<br />

experimental filmmaker<br />

Stan Brakhage lived<br />

briefly in the basement<br />

of Jess and Duncan’s<br />

house, just as<br />

Brakhage’s high-school<br />

friend from Denver, the<br />

filmmaker Lawrence<br />

Jordan, lived with<br />

Michael and Joanna McClure. With Bruce Conner,<br />

who worked in a multitude of media, including film,<br />

and became one of the stars of California assemblage,<br />

Jordan started Camera Obscura, a film society, as<br />

well as a theater devoted to 16 mm films, simply<br />

called the Movie. And Jordan collaborated with a<br />

number of the Jess and Duncan crowd, as well as<br />

collaborating directly with Jess on a film using Jess’s<br />

collages, Heavy Water, or The 40 & 1 Nights, or Jess’s<br />

Didactic Nickelodeon in the 1960s.<br />

Perhaps at the center of the story of the<br />

multibiosis around Jess and Duncan should be their<br />

creation, along with Jess’s classmate, Harry Jacobus,<br />

of the former garage turned into a gallery space and<br />

named by them the King Ubu Gallery after the 1896<br />

play by that forerunner of Dada and Surrealism,<br />

Alfred Jarry (copies of the New Directions translation<br />

with Jarry’s drawings can be found in the Dada-<br />

Surrealist bookcase across from the City Lights cash<br />

register for impulse buying like gum and candy at a<br />

supermarket checkout counter). King Ubu showed a<br />

Artworks by Jess and photo of Duncan<br />

& Jess © The Jess Collins Trust.<br />

8

Robert Duncan, Jess, and Friends<br />

range of artists, many from the California School of<br />

Fine Arts, and, as Christopher Wagstaff noted in an<br />

exhibition just on the gallery, artists were often paired<br />

who would contradict each other. And for the<br />

opening show, in addition to the uneven hanging of<br />

the artwork and murals painted on the walls creating<br />

a Dr. Cagliari imbalance, Miriam Hoffman’s<br />

sculptures created further dimensionality. And Jess<br />

later displayed a number of “Necrofacts,”<br />

assemblages of “real junk off the rubbish pile” in the<br />

gallery. But the gallery was also the venue for poetry<br />

readings for the likes of Jack Spicer, Philip Lamantia,<br />

Kenneth Rexroth, and Weldon Kees (who worked in a<br />

wide range of arts and music). Stan Brakhage’s first<br />

two films were played at the King Ubu. And Duncan<br />

put on Gertrude Stein’s The Five Georges complete<br />

with crayon-drawing backdrops by Duncan, of which<br />

King George III is in the current exhibition. One<br />

almost wishes that the exhibition could create the<br />

atmosphere of the King Ubu for the performance –<br />

because, after all, Duncan, Jess, and their friends<br />

were engaged in their own form of Wagnerian<br />

Gesamtkunstwerk – a combination of all the arts. It<br />

would be in the Six Gallery, which took over the<br />

space of King Ubu after its one-year run, that Allen<br />

Ginsberg first read his Howl (while Duncan and Jess<br />

were in Majorca) and Duncan put on his play Faust<br />

Foutu with Lawrence Jordan as the poet Faust, Jess<br />

playing his mother, and Michael McClure, Jack<br />

Spicer and other friends in various roles. It’s not that<br />

San Francisco with Jess and Duncan’s interlocking<br />

group of friends were alone in amalgamating the arts.<br />

Black Mountain College – where Duncan taught in<br />

the last year of its existence and put on plays (many of<br />

his final cast coming back to San Francisco with him)<br />

– offered a wide range of arts, with a faculty that<br />

included Josef Albers, modern dancer Merce<br />

Cunnningham, John Cage, Buckminster Fuller, and<br />

Charles Olson. It’s just that the amalgamation of the<br />

arts were particularly important in San Francisco.<br />

Duncan himself remarked that poetry – before<br />

Ginsberg’s reading – was particularly a performative<br />

art in San Francisco. Although he was talking about<br />

the performance of the reading, Duncan notably<br />

wrote Medieval Scenes in 1947 in ten nightly sessions<br />

in a séance-like atmosphere with his poet friends<br />

around him – he wrote as performance. The art<br />

exhibition could also be a “happening” avant la lettre,<br />

such as Wallace Berman’s Semina Gallery exhibitions<br />

that lasted typically for a single night on a houseboat,<br />

which followed his friend George Herms’s “Secret<br />

Exhibition” in Southern California.<br />

Arguably, Jess is best known for his collages<br />

– with the multi-decade Narkissos at the apex. Jess<br />

himself claimed in an interview published as an<br />

appendix to An Opening of the Field: “I first thought<br />

of collage when I visited Brockway’s mother in<br />

Naples, near [Alamitos Bay] in Southern California,<br />

not far from where I grew up . . . and she said, ‘Look<br />

at he collage I’ve just done.’ She had cut pictures of<br />

flowers from magazines, and it was at that moment I<br />

saw collage for the first time.” Never mind that<br />

Brockway’s mother knew the term “collage.” Never<br />

mind the long tradition of collage in modern art by<br />

the likes of artists like Picasso and Braque. In fact,<br />

collage and assemblage – and I think they should be<br />

seen as two-and three-dimensional siblings, or rather<br />

of a piece – seemed to generate in both northern and<br />

southern California. If one writer on Jess dismissed<br />

as a joke the 1949 “Museum of Unknown and Little<br />

Known Objects” by the California School of Fine<br />

Arts teacher Clay Spohn – the same man who urged<br />

Calder to use wire – that is simply to forget that<br />

humor is quite a serious tool in art. Similarly, Hassel<br />

Smith, an important teacher of Jess, had done his<br />

own assemblages and held a party in the late 1940s<br />

where he asked his each of his guests to bring a Dada<br />

object. As Richard Diebenkorn noted about the late<br />

1940s, “Assemblage was just in the air” – as were<br />

various forms of collage. So Jess’s collage did not<br />

spring full-bodied like Athena out of the head of<br />

Brockway’s mother.<br />

More important, however, is to recognize<br />

that both collage and assemblage are by themselves a<br />

form of the multibiosis around Jess and Duncan for<br />

the very reason that they take their elements from all<br />

parts of life, past, present, future, as well as the<br />

esoteric and the mythological, and pull them together<br />

in concert and disconcert. In Jess’s log for the<br />

creation of Narkissos, he delves – and Duncan would<br />

partner in this research – deeply into the Narcissus<br />

myth as well as its offshoots, various echoes, such as<br />

in Chaucer as well as the flower. And his large collage<br />

is full of images reflecting each other as well as<br />

integrating large numbers of popular culture elements,<br />

such as a Krazy Kat cartoon, Chicago’s Monadnock<br />

building, and a frame from Fritz Lang’s film<br />

Metropolis. So too would his The Chariot: Tarot VII<br />

(1962) cram an enormous number of images, only<br />

starting with ancient Eastern and Western sculpture<br />

(including Dionysus with grapes), umbrellas, old cars,<br />

train engines, owls, a fox, lobster claws, the hull of an<br />

ancient boat, and various eyes. In fact, the various<br />

eyes – and eyelike images – looking from various<br />

perspectives (even upside down) and in various<br />

9

Robert Duncan, Jess, and Friends<br />

directions – that add one of the elements that pull the<br />

viewer’s eye within the collage. With the Oakland<br />

Museum’s important Pop Art U.S.A. show in 1963,<br />

Jess was added as an important predecessor but felt<br />

the fit wasn’t right and offered: “I’m afraid I’m too<br />

romantic, and perhaps worse yet, sentimental.” But<br />

more than that, Jess’s work had much greater depth<br />

and cultural layering than Pop Art. He might have<br />

turned a feminine hygiene advertisement “Modess . .<br />

. because” into Goddess Because Is Is Falling Asleep<br />

(1954) but the collage is hardly a one-liner. His work<br />

brings in much more. Similarly, Duncan famously<br />

described his own poetry as a “grand collage” made<br />

up of so many found pieces and allusions. In an<br />

interview Duncan stated that he did not have “any<br />

style” and ventured more broadly that, in fact, “the<br />

American style is polyglot assemblage” because<br />

“Americans have no history.”<br />

Duncan wrote for an exhibition of Jess’s<br />

“Translation” series:<br />

The set of Translations and their Imagist<br />

Texts as they are presented in this show in<br />

this complex game of associations, in which<br />

the paintings are cards, the arcana of an<br />

individual Tarot, a game of initiations, of<br />

evocations, speculations, exorcisms, may be<br />

related to the field of dream and magic in art<br />

which we inherit in the tradition of the<br />

Surrealists. A play at once sinister and<br />

rightful, like Lewis’s Carroll’s play with<br />

words, but here, a play with the properties of<br />

paints and picturing.<br />

Just as Jess’s Abstract Expressionist<br />

teachers tended not to give titles to their paintings<br />

because they didn’t want to limit their meaning, Jess<br />

often gave his “Translations” titles starting with “Fig.”<br />

or “Ex.,” suggesting, as Ingrid Schaffner has<br />

observed, that they were figures or examples of<br />

something outside the painting - in essence, an<br />

invisible text led them. And just as Jess’s art was a<br />

constant playing with meanings, so Duncan called his<br />

own poetry “multiphasic.” In addition to Jess and<br />

Duncan’s shared love of Finnegan’s Wake, Duncan<br />

offered that “[i]n the archeologist’s sense, the OED<br />

had opened up the layers of language, and the OED is<br />

another one of the complicating factors at every step<br />

of writing, because that gives me the layers of very<br />

single English word through its layers of time. . . .”<br />

In fact, he asserted: “After all, Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake<br />

is drawing directly on the OED all the time.” One of<br />

his problems with Milton’s Paradise Lost is that<br />

Milton “has an outline” and poetry should not – for<br />

that reason, he points to Williams’s Paterson as<br />

coming to an end and Williams discovering that it<br />

had not ended yet. And Duncan was fond of<br />

McClure’s beast language because it was a way of<br />

“using sound to disturb language.” Duncan and Jess<br />

and many around them were deeply involved in<br />

various esoteric traditions but they were particularly<br />

fond of the Zohar (David Meltzer’s introduction to<br />

kabala came when Duncan burst out of a restroom in<br />

the store where Meltzer worked, indignant that a<br />

library copy of Gershom Scholem’s Major Trends in<br />

Jewish Mysticism had been left there). Duncan would<br />

talk about the world being made of letters in the<br />

kabalistic tradition – and, in a sense, that is symbolic<br />

for the range of artists around Duncan and Jess.<br />

Duncan, Jess and their friends were all, in a sense,<br />

engaged in a world made of symbols and letters and<br />

symbols and letters made up of the world.<br />

Notes<br />

“An Opening of the Field: Jess, Robert Duncan, and Their<br />

Circle,” exhibition organized by the Crocker Art Museum<br />

and curated by Michael Duncan and Christopher Wagstaff.<br />

Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, June 9 – September 1,<br />

2013<br />

Grey Art Gallery, New York University, January 14, March<br />

29, 2014<br />

Katzen Arts Center, American University, April 26 – August<br />

17, 2014<br />

Pasadena Museum of California Art, Sept. 14, 2014 – Jan.<br />

11, 2015<br />

Michael Duncan and Christopher Wagstaff, An Opening of<br />

the Field: Jess, Robert Duncan, and Their Circle (Pomegranate<br />

Communications, Inc., 2013)<br />

Lisa Jarnot, Robert Duncan: The Ambassador from Venus: A<br />

Biography (Univ. of California Press, 2012)<br />

Christopher Wagstaff, ed., A Poet’s Mind: Collected Interviews<br />

with Robert Duncan, 1960-1985 (North Atlantic Books,<br />

2012)<br />

Michael Duncan, ed., Jess: O! Tricky Cad & Other Jessoterica<br />

(Siglio, 2012)<br />

10

BILL BURROUGHS<br />

IN AMSTERDAM<br />

by Eddie<br />

Woods<br />

William S. Burroughs and I performed at<br />

the same major Amsterdam literary event back in<br />

1978, Soyo Benn Posset’s first One World Poetry<br />

festival, P78. Whose closing night, where WSB and I<br />

took to the big stage separately, I wrote about in a<br />

long rapid-fire prose poem entitled “Poetry & the<br />

Punks: An Apocalyptic Confrontation” which was<br />

published in P78 Anthology. But that’s not when I got<br />

to meet the author of Naked Lunch, Junkie, and Queer<br />

up close and personal. Same as with Bill’s friend and<br />

partner in experimental cut-ups crime Brion Gysin,<br />

that would come later. In the case of William it was<br />

the following year, when Benn again brought Bill to<br />

Holland, and not for the last time either. On this<br />

occasion Benn asked the Dutch poet Harry<br />

Hoogstraten to organize a special reading at the<br />

Melkweg multi-media center for Burroughs and other<br />

outlaws. Those others being Jules Deelder (aka ‘the<br />

night mayor of Rotterdam’), shamanic legend Simon<br />

Vinkenoog, the rock star Herman Brood, and of<br />

course Harry. While to emcee this extraordinary<br />

happening Harry chose me.<br />

The day of the evening reading began with<br />

an afternoon dinner on the Oudezijds Voorburgwal, a<br />

mere stone’s throw from the red-light district. With<br />

some of the attendees (albeit not William) gathering<br />

beforehand in the bar next door for nerves-settling<br />

drinks. Among whom was Brood, front man of the<br />

hugely popular band Wild Romance. Onstage,<br />

Herman (who in 2001 ended his life by flamboyantly<br />

leaping from the roof of the Amsterdam Hilton) was<br />

confidently outrageous. Yet in person he could often<br />

be incredibly shy. A trait I encountered whenever we<br />

bumped into one another and chatted at Padrino’s, a<br />

gangster restaurant near the Melkweg that didn’t start<br />

serving meals until midnight (and was also one of<br />

Soyo Benn’s favorite eateries). And who was Herman<br />

Brood’s junkie hero? You guessed it, Bill Burroughs.<br />

So much so that Herman, a talented artist as well as<br />

an accomplished singer/songwriter, had produced a<br />

series of comic strips for various underground music<br />

‘zines with the unnamed Burroughs as a main<br />

character. (Where are they today, these strips? God<br />

alone knows.) Now suddenly they were performing on<br />

the same program. And even sooner, Herman could<br />

connect one-on-one with his idol over dinner. Alas, it<br />

never happened. Nor did they get to exchange even a<br />

word. Shy Herman bottled, pure and simple.<br />

“Time to go eat,” I said to Herman in the<br />

bar.<br />

“Sorry, man, I gotta go get me some<br />

Angels. See you at the gig.”<br />

And off he sped to the nearby Hell’s Angels<br />

HQ, high on shots of speed and natural adrenalin.<br />

It was a narrow restaurant with a single<br />

long table accommodating a couple of dozen (mostly<br />

Dutch) writers and visiting firemen. William sat at<br />

the head, his back to the door. ‘Brave,’ I thought. ‘He<br />

must be packing a rod.’ (A love of guns was<br />

something Bill and I had in common.) I was at his<br />

left, Harry to his right. Benn had discreetly placed<br />

himself down at the end. William ate in silence, as<br />

did I. The rest blathered away, but not in our<br />

direction. Coffee and digestifs quickly segued into<br />

several writers coming forth to present Bill with<br />

books. Books in Dutch, a language Bill couldn’t read.<br />

Always the gentleman, Bill politely growled his thanks.<br />

That parade over and done with, I turned to Bill and<br />

11

Bill Burroughs in Amsterdam<br />

said: “I’m afraid I don’t have a book for you, but I do<br />

have this.” Whereupon I popped a gram ball of<br />

opium into the palm of his hand.<br />

“Oh, I know what this is,” he said,<br />

dividing the ball in two and immediately swallowing a<br />

half.<br />

“Say,” he then said, “allow me to return<br />

the favor.”<br />

And reaching into his jacket pocket, he<br />

withdrew a slim plastic container full of little pink<br />

pills and handed it to me saying: “Here, this is for<br />

you. I scored them in Paris, but have more at the<br />

hotel.”<br />

They were codeine, a drug I wasn’t much<br />

familiar with.<br />

“Much obliged,” said I. “But ah, how<br />

many should I take?”<br />

I’m a thin chap. In those days with<br />

particularly gaunt facial features. And so my question<br />

somewhat startled William.<br />

“How many? Dunno. Ten, maybe twelve.<br />

Hell, take as many as you like, you’re an old veteran!”<br />

Haha, Bill Burroughs reckoned I was a<br />

fellow junkie!<br />

There was still plenty of time to kill before<br />

the reading, and everyone headed to the Melkweg by<br />

William Burroughs, possibly Herbert Huncke’s<br />

pal Louis Cartwright took the picture<br />

12<br />

varied means, some individually, others in small<br />

groups. By then Bill and I had gotten into conversing,<br />

and so found ourselves walking together at a slow<br />

pace far behind the rest. We discussed heroin (“How<br />

much does it go for here?” Bill queried); guns (“In<br />

New York if you’re carrying and shoot someone in<br />

self-defense, no one will bother you,” he insisted,<br />

much to this New Yorker’s surprise); his son Billy,<br />

who was less than two years away from dying at age<br />

33; Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, the founder of<br />

Naropa University and Allen Ginsberg’s guru<br />

(“He definitely has powers,” William stated<br />

unreservedly, adding he saw that clearly<br />

when Trungpa visited Billy in hospital). That<br />

and all sorts of groovy stuff, with me doing<br />

most of the asking and listening.<br />

The event itself was a blast. With<br />

the packed-house Fonteinzaal audience<br />

paying rapt attention throughout. Deelder<br />

rapped rhythmic Chicago-style jazz poetry;<br />

Vinkenoog machinegun-delivered his usual<br />

high-powered mixture of psychedelic magic;<br />

Harry recited poems in English (the language<br />

he’d adopted for his writings during a<br />

lengthy stay in Ireland); William gravelyvoiced<br />

read a number of short tracts,<br />

including “Bugger the Queen” (that I<br />

eventually arranged for International Times in<br />

London to publish); with me reeling out my<br />

own verses in between making the<br />

introductions. Herman, who was nowhere in<br />

sight until I caught a glimpse of him up in<br />

the balcony sound room, I’d decided to save<br />

for last. And now it was time.<br />

“Ladies and gentlemen,” I called out, “let’s<br />

give an uproariously warm welcome to the one and<br />

only Herman Brood.”<br />

“I told you to wait, fucker!” screamed<br />

Herman from God knows where. (He hadn’t told me,<br />

but never mind.)<br />

“Seems Herman’s not quite ready, folks,” I<br />

laughed into the microphone. “So while he’s<br />

powdering his nose [more discreet than saying<br />

‘shooting up,’ eh], I’ll read a poem by Ira Cohen that<br />

I’m sure Herman will especially appreciate hearing.<br />

It’s entitled ‘A Brickbat for Herman Brood or P78<br />

Meets Wild Romance in Paradiso.’”<br />

I’ve no idea if Herman bothered to listen,<br />

but the crowd was stunned as I belted out lines like<br />

‘Let the bread stay in the breadbox, Herman’ and

Bill Burroughs in Amsterdam<br />

‘Patti Smith queens your pawn - Anarchy prevails - It<br />

is poetry which breaks the bars of jails!’<br />

No sooner had I finished than a<br />

thoroughly stoned Herman comes strolling towards<br />

the stage, his face beaming with a broad smile.<br />

“Alles okay, baba? I ask.<br />

“I’m fine, man, just fine,” he drawls.<br />

Followed by, “I brought some friends with me.”<br />

The friends were half a dozen wellseasoned<br />

Hell’s Angels, each of them holding a large<br />

bottle of beer. Herman would be knocking out<br />

poems, not singing songs. And minus his band, these<br />

dudes were his backup boys.<br />

They accompanied his<br />

recitations by stomping their<br />

feet in cadence to his words. It<br />

was a perfect performance that<br />

saw the audience cheering and<br />

howling for more. They got<br />

more, though not from Herman.<br />

He’d disappeared with all but<br />

one of the Angels, the tallest of<br />

the lot. Who then approached<br />

me and politely asked if he could<br />

recite a poem. I said sure,<br />

introduced him, he stepped up<br />

to the mike, pulled a tiny slip of<br />

paper from his jeans’ bicycle-key pocket, and<br />

“In New York if<br />

you’re carrying<br />

and shoot someone<br />

in self-<br />

defense, no one<br />

will bother<br />

you.”<br />

William<br />

Burroughs to<br />

Eddie Woods<br />

proceeded to recite an unbelievably sweet love poem.<br />

A pin-drop silence gave way to a round of applause.<br />

Bringing the reading to a close, I made a<br />

point of thanking William for the many hours of<br />

reading pleasure he’d afforded me over the years.<br />

“Pleasure?” Simon snarled loudly. “He’s<br />

trying to stick a knife in your heart!”<br />

“And if I get a kick out of that,” I snapped<br />

back, “what’s it to you?”<br />

The audience filed out...to the main hall,<br />

the café, the bar, the house dealer’s counter, wherever.<br />

We participants, sans Herman, adjourned to the<br />

Melkweg office, with the Angels tagging along.<br />

“Where’s Jack?” Angel Jack demanded to<br />

know from William.<br />

“He’s wherever you care to find him,” Bill<br />

responded, in his mind meaning Kerouac.<br />

“I’m Jack,” said Jack, stabbing at his own<br />

chest with a forefinger.<br />

“Oh, yes, I know what you mean,” Bill<br />

replied with a wise nod of the head. “It’s all in the<br />

Tibetan Book of the Dead.”<br />

“Eddie, get those guys out of here,” Soyo<br />

Benn pleaded with me, “before they drive William<br />

nuts.”<br />

I forget how exactly, but I got them to<br />

leave without a fuss.<br />

William made his exit shortly afterwards.<br />

We shook hands. Then referring to the remainder of<br />

the opium he’d already gulped down, he said: “Thank<br />

you, Eddie, I’m well away.”<br />

William and I next saw each other in 1985<br />

when he and his manager James Grauerholz, in<br />

company with Benn, visited Ins & Outs Press for a<br />

long afternoon into early evening.<br />

Plus we spoke on a live telephone<br />

hookup (that the audience could<br />

hear) during a 1993 Soyo Bennorganized<br />

Burroughs Tribute at the<br />

Melkweg that I co-emceed. And I<br />

had Bill affirm that I was not the<br />

Eddie Woods who witnessed him<br />

accidently shooting and killing his<br />

wife Joan Vollmer Burroughs in<br />

Mexico. (Literary Outlaw, Ted<br />

Morgan’s biography of William, had<br />

many people seriously believing it<br />

was me.)<br />

“No, Eddie,” Bill said<br />

dryly, “it wasn’t you.” And went on to describe my<br />

infamous namesake. Red hair, short, a good nine<br />

years younger than I, et cetera. I wrote about all of<br />

this in the essay “Thank God You’re Not Eddie<br />

Woods” that I delivered at the William Burroughs<br />

conference Naked Lunch@50 in Paris, 2009, and was<br />

subsequently published in Beat Scene.<br />

Btw, I was only half-joking when I said that<br />

Burroughs and Gysin were partners in cut-up crime.<br />

1) I don’t much care for the technique. (Neither did<br />

Gregory Corso, who collaborated on Minutes to Go<br />

only reluctantly); 2) To the extent it has any validity, I<br />

consider Harold Norse to be its real master. As<br />

exemplified in his ground-breaking novella Beat Hotel;<br />

3) I by far prefer Burroughs’ straighter writings to any<br />

of the cut-ups. None of which negates Norman<br />

Mailer’s 1962 appraisal of Burroughs as “the only<br />

American novelist living today who may conceivably<br />

be possessed by genius.” Hear, hear. That’s my Bill<br />

Burroughs, all right.<br />

© 2014 by Eddie Woods<br />

EDDIE WOODS is at http://eddiewoods.nl/<br />

13

A “Half-American”<br />

Writer<br />

Joyce ce Johnson<br />

I<br />

t is possible to know someone and not know them,<br />

especially when you are twenty-one and in love, and when<br />

there are painful things the other person never talks about.<br />

For about two years, starting one January night in<br />

1957, nine months before the publication of On the Road,<br />

Jack Kerouac came and went in my life. I knew, of course,<br />

that he was of French Canadian extraction, had a mother<br />

he called Memere, who spoke to him in French, that he was<br />

very fond of French cooking and that he still held on to his<br />

old dream of going to live someday in Paris, a dream he<br />

would never realize. In the spring of that first year I knew<br />

him, he finally did pass through there, completely broke as<br />

usual—but Paris, like nearly all his dreamed of destinations,<br />

was a disappointment. “It didn’t seem to want me,” was<br />

how he put it. (Perhaps part of the problem was that<br />

Parisians didn’t think much of the way Jack spoke French.)<br />

Before that he’d been in London, where he’d made a point<br />

of looking up his family’s Breton coat of arms in the British<br />

Museum Library. There he’d found the motto, Aimer,<br />

travailler, soufrir. Which he felt was the perfect summation<br />

of his life, as he told me when he was back in New York.<br />

I often heard him speaking in a low voice to my grey<br />

cat, to whom he’d given a French Canadian name, Tigris.<br />

He would feed Tigris in a way that never failed to charm<br />

me. Like a small boy, he’d lie flat on his belly with his chin<br />

against the rim of the cat’s bowl, murmuring encouraging<br />

words, half in French, half in English. Many years later<br />

when I read Vision of Gerard, the eerie significance of these<br />

little scenes dawned on me for the first time when I came to<br />

the lines: When the little kitty is given his milk, I imitate<br />

Gerard and get down on my stomach…”You happy, Ti Pou? –<br />

your nice lala.” I realized then that without knowing it I had<br />

witnessed a secret sacrament, heard Jack Kerouac calling up<br />

his dead nine-year-old Franco American brother, who was in<br />

some ways the submerged half of himself.<br />

Jack never explained to me that when he was a kid in<br />

Lowell, Massachusetts, he had only spoken the French<br />

Canadian language in his household and that he had not<br />

been a fluid English speaker until his late teens. I would<br />

have been astonished to learn that all his life, to one degree<br />

or another, he had been translating the French words in<br />

which he dreamed and thought into their English<br />

equivalents. Like most people who read On the Road when<br />

it came out six years after Jack had written it, I would<br />

certainly never have thought of Jack Kerouac as a bilingual<br />

writer, for I could think of no contemporary novelist who<br />

seemed so completely in the American grain and my ear did<br />

not pick up the French overtones in Sal Paradise’s voice,<br />

which was one of the things, I now realize, that gave Jack’s<br />

first-person prose such a distinctive quality. That first<br />

person voice seemed so natural and effortless, in fact, that I<br />

did not realize it had taken Jack ten years and piles of<br />

discarded manuscripts to finally arrive at it — or that it was<br />

a voice he’d kept suppressing in his writing, until, in the<br />

spring of 1951, he’d finally embraced and accepted its<br />

power, and written On the Road in the now legendary 21<br />

days of concentrated effort in one long typed paragraph on<br />

a 120-foot scroll of paper. Jack did not mention Franco<br />

Americans in the book I first read in its much edited version,<br />

although its narrator, Sal Paradise, apparently Italian<br />

American, expressed powerful feelings of identification with<br />

black and Hispanic people.<br />

14

A Half-American<br />

Writer<br />

During the period I was involved with Jack, his<br />

publisher, Viking Press, despite the huge recent success of<br />

On the Road, turned down his first Lowell novel, Dr. Sax,<br />

which dealt with his Franco American childhood and<br />

opened with the blatantly French-sounding sentence, “In<br />

Centralville I was born.” It did not occur to me that the<br />

book’s ethnic subject matter may have been one of the<br />

reasons for this rejection and for the Viking editors’ lack of<br />

interest in any novel about Jack’s boyhood, though he was<br />

encouraged to write Dharma Bums as a followup to On the<br />

Road. Now that I’ve written my Kerouac biography, I am<br />

sometimes amazed by how much I didn’t understand<br />

during the time I knew Jack.<br />

Until it was possible for me to<br />

read Jack’s journals in the Kerouac<br />

archive at the New York Public<br />

Library, I had never seen this<br />

revelatory passage he wrote at 23<br />

shortly after the war had ended, just<br />

after he taken a walk through his<br />

neighborhood in Queens:<br />

Today, Labor Day, a clear sunny<br />

day with the tender blue char in the sky<br />

hinting of October. I felt a resurgence of<br />

the old feeling, the old Faustian urge to<br />

understand the whole in one sweep and<br />

to express it in one magnificent work—<br />

mainly America and American life.<br />

Bunting, flying leaves, families<br />

drinking beer in their own backyard,<br />

cars filling the highways…Children<br />

tanned and ready for school, the smell of<br />

roasts coming from the cottages on the<br />

leafy street, the whole rich American life<br />

in one panorama. I had the feeling<br />

that I was alien to all this…that all this could never be mine,<br />

only to express…All of this America, not for my likes, never. It’s<br />

strange, since I’m aware that I understand all this far more than<br />

the people who do have the American richness in<br />

them.”Acknowledging the fact that because of the Breton<br />

bleakness in his soul, he would always feel like an outsider in<br />

this country, Jack called himself only half-American. Six<br />

years later, when it came time to write a novel that would<br />

sweep its readers westward across the American landscape,<br />

that novel would be written with the passion of an outsider.<br />

All this America, not for my likes, never. Doesn’t that line<br />

sound directly translated from the French? And isn’t that<br />

feeling of not entirely belonging here very American itself?<br />

In the fall of 1940, the incoming freshman John L.<br />

Kerouac arrived at Columbia on a football scholarship after<br />

spending two terms at the Horace Mann prep school<br />

where he had been sent to make up some courses. This was a<br />

milestone in Jack’s American journey. His entry into a<br />

university was the goal he had set himself by the time he<br />

started high school, already knowing he wanted to be a<br />

writer, already aware there was no way he could use the<br />

French Canadian language for the books he dreamed of<br />

writing and that he would have to find a way of leaving<br />

Lowell, Massachusetts where he had grown up in one of the<br />

insular French-speaking communities that could be found<br />

throughout New England. In his sophomore year, however,<br />

he would disappoint his family by walking away from his<br />

opportunity to get a college education. Football practice had<br />

left him little time for his studies<br />

and no time to write and he had<br />

fallen under the spell of Thomas<br />

Wolfe. He took a bus southward,<br />

then changed his mind and went<br />

north. He found a job in a garage<br />

in Hartford, rented a small room<br />

and an Underwood typewriter,<br />

wrote one story after another and<br />

experienced hunger for the first<br />

time.<br />

Not even the barrier of<br />

language could extinguish Jack’s<br />

inborn need to write. From the<br />

time he was eleven, he began<br />

working to make himself fluent<br />

in English—a process that<br />

continued into his adult life—<br />

and wrote a little novel, Jack<br />

Kerouac Explores the Merrimack,<br />

heavily influenced by<br />

Huckleberry Finn. His juvenilia<br />

includes some remarkable handprinted newspapers, inspired<br />

by the racing papers, his father constantly consulted for tips<br />

on horses. Calling himself Jack Lewis, Jack imagined himself<br />

its publisher, its chief reporter, a celebrated jockey and the<br />

owner of a prizewinning horse named Repulsion—he<br />

evidently loved the forceful sound of that word without<br />

knowing it meant the opposite of what he intended.<br />

Making a similar mistake, he made up a wizard named Dr.<br />

Malodorous—MaloDORus was probably how he<br />

pronounced it –he considered this the most beautiful word<br />

he knew. At seventeen, when Jack was trying to write like<br />

William Saroyan, he papered the walls of his room with lists<br />

of words he’d found in the dictionary. At twenty-two, in<br />

what he called his ne-Rimbaudean period, he was still<br />

working at increasing his vocabulary, writing the definitions<br />

of calescent, ectogenic, dysphasia and surah into his notebook,<br />

15<br />

above, Minor Characters: A Beat Memoir by Joyce Johnson,<br />

which originally appeared in 1983, published by Houghton<br />

Miflin. Note Joyce standing in the shadows of love behind<br />

Jack Kerouac.

A Half-American<br />

Writer<br />

in case he should ever need to use them. “Smooth as surah”<br />

he wrote years later in Visions of Gerard, describing the skin<br />

of a character named Mr. Groscorp.<br />

In Lowell, Jack had begun his education at the<br />

neighborhood parochial school, St. Louis de France.<br />

There the morning classes were taught in French and the<br />

afternoon classes were taught in English. The students<br />

pledged allegiance to la race Canadienne as well as the<br />

American flag. The huge redbrick mills along the<br />

Merrimack River pointed to the fate that awaited many<br />

of Jack’s classmates and that Jack would become determined<br />

to escape. Very few young Franco Americans in Jack’s day<br />

left the communities they had been raised in or succeeded in<br />

going to college; very few attempted the kind of lonely<br />

journey Jack would take into the American mainstream. (“I<br />

don’t even look like a<br />

writer,” Jack would later<br />

confess to his journal. “I<br />

look like a lumberjack.”)<br />

There was still tremendous<br />

prejudice against Jack’s<br />

people, with most<br />

Americans believing they<br />

were backward. Up where<br />

Jack came from they were<br />

called “white niggers” of<br />

“the Chinese of New<br />

England.” “Dumb<br />

Canuck” was a common epithet that I even heard used<br />

teasingly by one of Jack’s friends. But even in the 1950’s,<br />

Franco Americans still kept to themselves for other reasons:<br />

the almost mystical belief that they must uphold the old<br />

ideals and customs of what they called la survivance and<br />

continue to speak their distinctive language, which was so<br />

woven into their religion.<br />

Lowell, the birthplace of the American industrial<br />

revolution, was a melting pot, where people from various<br />

ethnic groups—Irish Catholic, Greek, Syrian, as well as a<br />

sprinkling of Jews—had come in the last decades of the 19 th<br />

century to make their living in the mills, and where the<br />

French Canadians, escaping from starvation on their<br />

hardscrabble potato farms in Quebec, had been willing to<br />

take the worst jobs. People from these different groups<br />

mingled in the mills and the bustling downtown streets and<br />

went home to their separate neighborhoods; their children<br />

met each other in Lowell’s public schools and on the<br />

baseball fields. There were handsome pubic buildings in<br />

Lowell, such as the Public Library and the Atheneum that<br />

had been built by wealthy New England mill owners; there<br />

were also neighborhoods of wooden tenements where there<br />

were frequent fires and epidemics of cholera and meningitis<br />

and where many of the workers in the textile mills, where<br />

the windows were nailed shut, suffered from emphysema<br />

and tuberculosis. The deaths of children were not at all<br />

uncommon in Lowell. Jack’s mother had grown up in the<br />

nearby town of Nashua and gone to work in a shoe factory<br />

at the age of fifteen; she could write English quite fluently<br />

but never learned to speak it well. Jack’s. Father, Leo<br />

Kerouac, was bright and enterprising, and his command of<br />

English was unusually good. He was a reader, who believed<br />

that nothing compared to French culture, and worshipped<br />

Balzac and Victor Hugo. Until he lost it during<br />

the Depression, when the Kerouac’s became poor, Leo had<br />

his own small printing business, which did not confine itself<br />

to the Franco American community. Compared to most<br />

French kids, Jack’s early years were relatively privileged,<br />

although they were<br />

darkened by the death of<br />

his nine-year-old brother<br />

Gerard—a traumatic event<br />

that haunted Jack his entire<br />

life...<br />

Jack picked up his<br />

first words in English from<br />

the only Irish Catholic boy<br />

in his French-speaking<br />

kindergarten. He learned<br />

more from the half days of<br />

instruction in his parish<br />

school, St. Louis de France, but he undoubtedly would<br />

have continued his French education through high school,<br />

if the rezoning of his French Catholic middle school had not<br />

forced him to transfer to Bartlett Junior High School in<br />

Seventh Grade. If this had not happened, his grasp of<br />

English might have remained uncertain and handicapped<br />

his writing. His parents registered him at Bartlett as a<br />

commercial student.<br />

Embarrassed by his accent, one of the contributing factors<br />

to his lifelong shyness, he rarely spoke in his classes.<br />

Fortunately a discerning English teacher noticed how<br />

surprisingly well Jackie Kerouac could write. She advised<br />

him to start going to the Public Library and recommended<br />

that he read Longfellow and Twain. Every Saturday he took<br />

home an armload of books. He was a book-hungry kid,<br />

who read indiscriminately and ravenously—everything from<br />

The Little Shepherd of Kingdom Come to the novels of<br />

Jack London, Charles Dickens and Arthur Conan Doyle. At<br />

sixteen, when he was cutting school to spend days at the<br />

library, he would discover Goethe, who had a lasting<br />

influence on his thinking. He was also addicted to pulp<br />

fiction, absorbing the American vernacular from The Shadow<br />

series, as well as from comics, sports novels and westerns.<br />

A happy Jack Kerouac<br />

16

A Half-American<br />

Writer<br />

Another important factor in Jack’s Americanization were the<br />

movies he saw every Saturday from the balcony of Lowell’s<br />

Royal Theater. There he watched cowboys gallop across the<br />

screen, heard the twang of W.C. Fields and the New Yorkese<br />

of Groucho Marx. His novels would be filled with cinematic<br />

references.<br />

Jack later admitted that the more he set himself to<br />

master English, the more he felt he lost some of his French.<br />

“I have no language of my own,” he would tell Yvonne<br />

LeMaitre, who had reviewed his first novel, The Town and<br />

the City for a Franco-American newspaper. It would take<br />

Jack a long time before he instinctively made the transition<br />

from one language to another. A note in his 1945 journals<br />

shows that it was still a process accompanied by a very<br />

conscious shifting of gears. First Jack had to remind himself<br />

that he was not writing in French; then he had to figure out<br />

how to capture his “simultaneous impressions” in English.<br />

Then, because he was aiming at what he called “sense<br />

thinking,” he had to take care not to fall into the English<br />

literary tradition of reporting on what the writer was feeling.<br />

Jack’s father believed that his son could rescue the<br />

family from poverty by becoming a football star. In his<br />

estimation, writers and artists were parasites. “There’s no one<br />

with a name like Kerouac in the writing game,” he told Jack,<br />

convinced that only a Frenchman like Victor Hugo with a<br />

mastery of classical French could become a writer. The<br />

French Canadian language, as it was spoken in Lowell, was<br />

not the French spoken in Paris, or the French spoken in<br />

Montreal, where it was called joual. It was a richly expressive<br />

oral language that varied from place to place and, even in<br />

the early 20 th century lacked fixed spellings. Joual had<br />

developed from the regional dialects the French settlers<br />

brought to Canada in the 17 th and 18 th centuries, plus an<br />

accumulation of words picked up the Iroquois and the<br />

English. The Parisians said pommes de terres for potatoes; the<br />

Quebecois said patates. Jack’s mother said mue for me; Victor<br />

Hugo said moi. Even as he was preparing himself to leave it<br />

behind, Jack was proud of the richness of his native<br />

language. “The language called Canadian French is the<br />

strongest in the world when it comes to words of power,” he<br />

wrote at nineteen. “It is too bad that one cannot study it in<br />

college, for it is one of the language languages in the<br />

world…it is the language of the tongue and not of the<br />

pen…it is a terrific, a huge language.” In his thirties, he<br />

would defiantly begin to write passages in that language in<br />

his novels.<br />

In 1941, just as Jack began his second year at<br />

Columbia, he read Look Homeward Angel by Thomas<br />

Wolfe—a writer with whom he felt an immediate<br />

psychological affinity and whose depictions of small town<br />

and urban America and richly lyrical, maximalist prose style<br />

would have a tremendous influence upon the fiction Jack<br />

would attempt to write himself, as he worked toward<br />

producing his own Great American Novel. All through his<br />

years of apprenticeship, Jack started many novels that he<br />

would decide to put aside, only completing three of them,<br />

the most important of which was The Town and the City,<br />

published in 1950. All of them were novels with an<br />

autobiographical base in which Jack heavily fictionalized his<br />

own experiences; all of the protagonists were given typical<br />

American names, and in none of these books did Jack deal<br />

with his Franco American identity. Envisioning The Town<br />

and the City as a “universal American story,” Jack deliberately<br />

avoided emphasizing the Martin family’s half Franco-<br />

American background and their devout Catholicism. “Isn’t it<br />

true,” he wrote to Yvonne LeMaitre, who had astutely raised<br />

questions about these issues, “that French Canadians<br />

everywhere tend to hide their real sources?” They were able<br />

to do that, Jack thought, because unlike other minorities,<br />

such as Jews or Italians, they could pass as “Anglo Saxon.” A<br />

fiction writer today, in our multi-culturally minded era,<br />

would make the most of his hyphenated background and in<br />

fact would probably consider it an asset. But sixty years<br />