Genesis 2-5 - In Depth Bible Commentaries

Genesis 2-5 - In Depth Bible Commentaries

Genesis 2-5 - In Depth Bible Commentaries

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Genesis</strong> 2:4-4:26, The Things Brought Forth in the Heavens and the Earth<br />

When They Were Created–<br />

Luxurious Garden and Expulsion<br />

Please read <strong>Genesis</strong> 2:4-4:26 carefully in NIVSB, TNISB and ESVSB, along with their<br />

notes, before beginning to use this translation with its footnotes. These chapters, like the story of<br />

creation, are of vital importance for Biblical Theology! As we seek to come to know the God of<br />

the <strong>Bible</strong>, YHWH of Israel / Jesus Christ, let us pray constantly for Divine guidance!<br />

<strong>Genesis</strong> 2:4-25, the Biblical View of Human Origins, Especially of Marriage<br />

<strong>In</strong>troduction 1<br />

1<br />

Fox comments on <strong>Genesis</strong> 2:4b-3:24, that “This most famous of all <strong>Genesis</strong> stories contains<br />

an assortment of mythic elements and images which are common to human views of prehistory:<br />

the lush garden [the Muslim Koran’s view of heaven is permeated with ‘garden’ images], four<br />

central rivers located (at least partially) in fabled lands, the mysterious trees anchoring the garden<br />

...a primeval man and woman living in unashamed nakedness, an animal that talks, and a God<br />

Who converses regularly and intimately with His creatures...<br />

“The narrative presents itself, at least on the surface, as a story of origins. We are to learn<br />

the roots of human sexual feelings, of pain in childbirth, and how the anomalous snake (a land<br />

creature with no legs) came to assume its present form. Most strikingly, of course, the story<br />

seeks to explain the origin of the event most central to human consciousness, death...<br />

“Part I of the story (chapter 2) sets the stage in the garden, focusing on Adam, ‘Everyman’...<br />

“Part II (chapter 3)...[with its introduction of the snake] as the third character is typically<br />

ancient Near Eastern (it is so used in other stories about death and immortality, such as the<br />

Gilgamesh Epic from Mesopotamia)...[and which] disappears as a personality once the fatal fruit<br />

has been eaten...<br />

“Although the specifics of this story are never again referred to in the Hebrew <strong>Bible</strong>, and<br />

are certainly not crucial for the rest of <strong>Genesis</strong>, one general theme is central to the <strong>Bible</strong>’s<br />

worldview. This is that rebellion against or disobedience toward God and His laws results in<br />

banishment / estrangement and, literally or figuratively, death. Thus from the beginning the<br />

element of choice, so much stressed by the prophets later on, is seen as the major element in<br />

human existence...<br />

“The resolution of the story, banishment from the garden, suggests the tragic realization<br />

that human beings must make their way through the world with the knowledge of death and with<br />

great physical difficulty. At the same time the archetypal [original type or pattern] man and woman<br />

do not make the journey alone. They are provided with protection (clothing) given to them by<br />

the same God Who punished them for their disobedience. We thus symbolically enter adulthood<br />

1<br />

(continued...)

A second story of the creation of the first man--the transcendent God is the immanent God,<br />

YHWH–(2:4-7)<br />

Humanity is finite--made from dust, humanity shares in animal-life<br />

The "garden of Luxurious Place," "in the east," with its two special trees--(2:8-9)<br />

A river, that becomes four major rivers, flows from that garden--(2:10-14)<br />

Humanity responsible for productivity through labor--(2:15)<br />

Humanity subject to a Divine prohibition from eating of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil<br />

--(2:16)<br />

Humanity made for companionship--the creation of woman--(2:16-25)<br />

A first marriage<br />

No shame in human sexuality 2<br />

1<br />

(...continued)<br />

with the realization that being turned out of paradise does not mean eternal rejection or hopelessness.”<br />

(Pp. 17-18)<br />

2<br />

What an important passage this is for understanding the biblical teaching concerning woman,<br />

and marriage!<br />

See Suras 2:30-39; 7:11-25; 15:26-44, 17:61-65, 20:115-124 and 38:71-85 for the<br />

Koran’s story of the garden of Eden.<br />

2

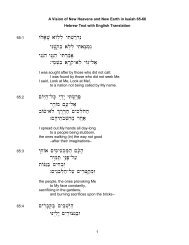

The Biblical View of Human Origins, Especially of Marriage<br />

<strong>Genesis</strong> 2:4-25, Hebrew Text with English Translation<br />

2.4 ~yhil{a/ hw"hy> tAf[] ~AyB. ~a'r>B'hiB. #r,a'h'w> ~yIm;V'h; tAdl.At hL,ae<br />

`~yIm'v'w> #r,a, These (are the) things brought forth (in) the heavens and the earth, when they<br />

were created, on (the) day (of) YHWH God’s making earth and heavens: 2.5 x;yfi lkow><br />

hw"hy> ryjim.hi al{ yKi xm'c.yI ~r,j, hd,F'h;bf,[e-lk'w> #r,a'b' hy #r,a'h'-l[; ~yhil{a/ And every plant of the field will not<br />

yet be in the earth, and all vegetation of the field will not yet sprout. For YHWH God did not<br />

cause rain upon the earth, and there is no human being to work the ground. 2.6 hl,[]y: daew.<br />

`hm'd'a]h'-ynEP.-lK'-ta, hq'v.hiw> #r,a'h'-!mi And a mist would go up from the earth, and it<br />

would water all the face of the ground. 2.7 -!mi rp'[' ~d'a'h'-ta, ~yhil{a/hw"hy> rc,yYIw:<br />

`hY"x; vp,n [J;YIw:<br />

`rc'y" rv,a] ~d'a'h' -ta, ~v' And YHWH God planted a garden in Luxurious Place, eastwards;<br />

and there He placed the human whom He shaped.<br />

2.9 bAjw> ha,r>m;l. dm'x.n< #[e-lK' hm'd'a]h'-!mi ~yhil{a/ hw"hy> xm;c.Y:w:<br />

`[r'w" bAj t[;D;h; #[ew> !G"h; %AtB. ~yYIx;h; #[ew> lk'a]m;l.And YHWH God caused to<br />

sprout from the ground every tree desirable for seeing, and good for eating; and a tree of the<br />

lives, in (the) middle of the garden; and a tree of the knowledge (of) good and evil. 2.10 rh'n"w><br />

`~yviar' h['B'r>a;l. hy"h'w> dreP'yI ~V'miW !G"h;-ta, tAqv.h;l. .!d,[eme aceyO And a river is<br />

3

going out from Luxurious Place, to give drink to the garden; and from there it divides, and it<br />

becomes four river-sources. 2.11 #r,a,-lK' tae bbeSoh; aWh .!AvyPi dx'a,h' ~ve<br />

`bh'Z"h; ~v'-rv,a] hl'ywIx]h; The one’s name, Piyshon–it is the one that encircles all the<br />

Chavilah (land), where there is the gold. 2.12 xl;doB.h; ~v' bAj awhih; #r,a'h' bh;z]W<br />

`~h;Voh; !b,a,w> And that land’s gold (is) good–there (also is) the bedholach, and the shoham<br />

stone. 2.13`vWK #r,a,-lK' tae bbeASh; aWh !AxyGI ynIVeh; rh'N"h;-~vew> And the<br />

second river’s name– Giychon. It is the one that encircles the entire Land of Ethiopia. 2.14<br />

aWh y[iybir>h' rh'N"h;w> rWVa; tm;d>qi %lehoh; aWh lq,D,xi yviyliV.h; rh'N"h; ~vew><br />

`tr'p. And the third river’s name, Chiddeqel. It is the one that flows east of Assyria. And the<br />

fourth river–it is Perath.<br />

2.15 `Hr'm.v'l.W Hd'b.['l. !d,[e-!g:b. WhxeNIY:w: ~d'a'h'-ta, ~yhil{a/ hw"hy> xQ;YIw:<br />

And YHWH God took the human being, and placed him in (the) garden of Luxurious Place, to<br />

work it and to preserve it.<br />

2.16 `lkeaTo lkoïa' !G"h;-#[e lKomi rmoale ~d'a'h'-l[; ~yhil{a/ hw"hy> wc;y>w: And<br />

YHWH God commanded the human being, saying, From every tree of the garden you may fully<br />

eat. 2.17 tAm WNM,mi ^l.k'a] ~AyB. yKi WNM,mi lk;ato al{ [r'w" bAj t[;D;h; #[emeW<br />

`tWmT' And from (the) tree of the knowledge (of) good and evil, you shall not eat from it;<br />

because in the day of your eating from it, you will surely die.<br />

2.18 rz

v,a] lkow> Al-ar'q.YI-hm; tAar>li ~d'a'h'-la, abeY"w: ~yIm;V'h; @A[-lK' taew> hd,F'h;<br />

`Amv. aWh hY"x; vp,n< ~d'a'h' Al-ar'q.yI And YHWH God shaped from the ground every<br />

live animal of the field, and every bird of the heavens, and He brought (them) to the human being<br />

to see what he would call out to it; and everything that the human being called out to it–[the] living<br />

animal(s)--that (was) its name. 2.20 @A[l.W hm'heB.h;-lk'l. tAmve ~d'a'h'ar'q.YIw:<br />

`ADg>nT; ~yhil{a/<br />

And YHWH God caused a deep sleep to fall upon the human being, and he slept. And He took<br />

one of his sides, and closed (with) flesh behind it. 2.22 [l'Ceh, ;-ta ~yhil{a/ hw"hy> !b,YIw:<br />

`~d'a'h'-la, h'a,biy>w: hV'ail. ~d'a'h'-!mi xq;l'-rv,a] And YHWH God built the side which<br />

He took from the human being, into a woman, and He brought her to the human being.<br />

2.23 ~d'a'h' rm,aYOw:<br />

ym;c'[]me ~c,[, ~[;P;h; tazO<br />

yrIf'B.mi rf'b'W<br />

hV'ai areQ'yI tazOl.<br />

`taZO-hx'q\lu vyaime yKi<br />

And the human being said,<br />

This now, bone from my bones,<br />

and flesh from my flesh;<br />

to this it will be called out, Woman,<br />

because from a man was taken this one.<br />

5

2.24 !Ke;-l[;<br />

AMai-ta,w> wybia'-ta, vyai-bz"[]y:<br />

ATv.aiB. qb;d'w><br />

`dx'a,rf'b'l. Wyh'w><br />

For this reason<br />

a man will leave his father and his mother,<br />

and he will hold closely to his woman;<br />

and they will become one flesh.<br />

2.25 `Wvv'Bot.yI al{w> ATv.aiw> ~d'a'h' ~yMiWr[] ~h,ynEv. Wyh.YIw: And the two of them were<br />

naked, the human being and his woman–and they were not ashamed.<br />

6

The Biblical View of Marriage<br />

<strong>Genesis</strong> 2:4-25, Hebrew Text with Translation and Footnotes<br />

3<br />

2.4 ~yhil{a/ hw"hy> tAf[] ~AyB. ~a'r>B'hiB. #r,a'h'w> ~yIm;V'h; tAdl.At hL,a<br />

3<br />

Sarna comments on 2:4-3:24 that “While God the Creator was the primary subject of the<br />

previous chapter, the focus of attention now shifts to humankind...One of the most serious questions<br />

to which the present narrative addresses itself–the origin of evil–would be unintelligible<br />

without the fundamental postulate of the preceding cosmology, repeated there seven times: the<br />

essential goodness of the Divine creation...<br />

“The startling contrast between this vision of God’s ideal world and the world of human<br />

experience requires explanation...How is the existence of evil to be accounted for?...The biblical<br />

answer to this fundamental question, diametrically opposed to prevalent pagan conceptions, is<br />

that there is no inherent, primordial evil at work in the world. The source of evil is not metaphysical<br />

but moral. Evil is not trans-historical but humanly wrought. Human beings possess free will,<br />

but free will is beneficial only insofar as its exercise is in accordance with Divine will...Abuse of the<br />

power of choice makes disaster inescapable.” (P. 16)<br />

Bowie comments that “<strong>In</strong> the story of the garden of Eden there is revealed the eternal truth<br />

that there is right and wrong, a true choice and a false choice; an obedience to the voice that represents<br />

the highest, and a willful disobedience; and that when man has sinned, no matter with<br />

what plausible excuse, there is that within him which shrinks away and hides, naked and ashamed<br />

before the light.” (P. 498)<br />

Westermann comments on <strong>Genesis</strong> 2-3 that “Exegetes are constantly turning to [this<br />

passage]; they never cease proposing fresh interpretations. <strong>In</strong> fact there are so many that only<br />

the most important can be outlined here [in his massive three-volume work].” (P. 186)<br />

This is certainly true, because this ancient story is so filled with important and challenging<br />

theological views that it has become a continuing source of biblical understanding, challenging its<br />

interpreters to probe its depth of meaning.<br />

Westermann also states that “The whole event described in <strong>Genesis</strong> 2-3 reveals a carefully<br />

constructed arch which begins with the command that God gives to his human creatures, and<br />

ascends to a climax with the transgression of the command. It then descends from the climax to<br />

the consequences of the transgression–the discovery, the trial and the punishment. The conclusion,<br />

the expulsion from the garden where God has put the man and woman, calls to mind again<br />

the beginning. There is a well-rounded, clear and polished chain of events.” (P. 190)<br />

“What distinguishes the story in <strong>Genesis</strong> 2-3 from Joshua 7 [the story of Achan’s crime<br />

and its punishment] or from Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment is that everything takes place<br />

in a direct confrontation between humans and God: God addresses the prohibition directly to the<br />

man. God Himself discovers the transgression, conducts the trial and pronounces judgment...The<br />

paradise story then is a primeval narrative of crime and punishment. All narratives in <strong>Genesis</strong> 1-<br />

11 (4:1-6; 6:1-4; 6-9; 11:1-10) belong directly or indirectly to this broad category.” (P. 193)<br />

7<br />

(continued...)

3<br />

(...continued)<br />

Westermann holds that “The history of Israel together with everything that happened in it,<br />

is part of the history of humankind and cannot be set apart from it or put in a different order...The<br />

‘fall’ introduces a story of curse which is followed by a story of blessing beginning in <strong>Genesis</strong> 12.<br />

The express function of the primeval story [is] to give meaning to God’s action toward humankind<br />

as a whole; this colors the whole work. God’s action toward His human creatures and the goal He<br />

has set for them, <strong>Genesis</strong> 12:3, remains always the background to what is said about His special<br />

action toward His people. This accords with the lively interest which [the author] shows in human<br />

beings, their potential and their limits, in his presentation of the patriarchal history... (Pp. 196-97)<br />

Wenham comments that “Within this editorially demarcated unit of 2:5-4:26, three quite<br />

distinct narratives are apparent: the garden of Eden, 2:5-3:24; the murder of Abel, 4:1-16; Cain’s<br />

family, 4:17-26...<br />

“The garden story itself falls into two halves:<br />

2:5-25 (the creation of man and his wife);<br />

3:1-24 (the temptation and fall from the garden)...<br />

“Chapter 2 further subdivides into:<br />

(a) the creation of man and the garden, verses 5-17;<br />

(b) the creation of woman, verses 18-25.” (1, p. 49)<br />

Wenham then goes on to describe the garden story as consisting of seven scenes:<br />

(1) 2:5-17 Narrative God the sole actor; man present but passive<br />

(2) 2:18-25 Narrative God the main actor, man minor role, woman and animals<br />

passive<br />

(3) 3:1-5 Dialogue Snake and woman<br />

(4) 3:6-8 Narrative Man and woman<br />

(5) 3:9-13 Dialogue God, man and woman<br />

(6) 3:14-21 Narrative God main actor, man minor role, woman and snake passive<br />

(7) 3:22-24 Narrative God sole actor: man passive<br />

“...The whole narrative is therefore a masterpiece of palistrophic writing, the mirror-image<br />

style, whereby the first scene matches the last, the second the [next to last] and so on...” (P. 51)<br />

Wenham discusses the relationship of the garden-story to other Near Eastern material. He<br />

states that “Sumerian tradition told of a paradise island on Dilmun at the head of the Persian Gulf<br />

...with an abundance of life-giving water springing out of the earth [see ‘Enki and Ninhursag: a<br />

Paradise Myth’ in ANET, pp. 37-41]...Similarly, Ugaritic mythology also affirmed that El lived ‘at<br />

8<br />

(continued...)

3<br />

(...continued)<br />

the sources of the two rivers in the midst of the two oceans’ [see ANET, ‘The Tale of Aqhat,’ pp.<br />

149-55, especially p. 152]...<br />

“This shows that the idea of a well-watered paradise where the Gods dwelt was a common<br />

motif in the ancient Orient...<br />

“It is often affirmed that the notion of plants that could confer immortality was well known in<br />

antiquity...Very interestingly, the Epic of Gilgamesh (11:280-90) links a serpent with such a lifegiving<br />

plant. Having acquired this plant, Gilgamesh left it beside a well while he went to bathe, but<br />

a snake appeared and ate it...<br />

“But the most striking comparison is with the Adapa Myth which, though of Mesopotamian<br />

origin, was also found at Tell el-Amarna in Egypt [see ANET, pp. 101-03]. Adapa is phonetically<br />

close to Adam and he is also known to be the first of the seven sages (apkallus) of Mesopotamia,<br />

who were contemporaries of the antediluvian [‘before the flood’] kings...Adapa was summoned to<br />

heaven where he was interrogated by the God Anu and invited to eat of the bread of life and<br />

water of life. But Adapa declined having been briefed in advance by his personal God Ea not to<br />

accept such an offer. Adapa was then allowed to return to earth...Though at first sight this looks<br />

like a close parallel to the <strong>Genesis</strong> story, the context of the Adapa myth is quite different, and the<br />

obedience of Adapa contrasts with the disobedience of Adam.<br />

“<strong>In</strong> all these cases there is no evidence of simple borrowing by the Hebrew writer. It would<br />

be better to suppose that he has borrowed various familiar mythological motifs, transformed them,<br />

and integrated them into a fresh and original story of his own...<br />

“Whereas Adapa heeded the word of the God Ea and did not eat the forbidden fruit, Adam<br />

and Eve rejected the Lord’s command and followed the serpent...<br />

“<strong>In</strong> the Gilgamesh Epic the snake devoured the plant of rejuvenation: in <strong>Genesis</strong> no one<br />

is said to have consumed it...<br />

“The Atrahasis Epic (1:208-50 [see ANET, pp. 512-14]) mentions that man was created<br />

out of clay mixed with the blood of a God, indicating that man is partly physical, partly Divine...<br />

“<strong>Genesis</strong> puts the same idea into different images: man was made from the dust of the<br />

ground, and then God breathed into him the breath of life...<br />

“<strong>In</strong> Mesopotamian thought, man worked so that the Gods could rest. <strong>Genesis</strong> 2 gives no<br />

hint of this approach: God worked until all man’s needs were satisfied...<br />

”The God of <strong>Genesis</strong> is totally concerned with man’s welfare. Man is to be more than a<br />

tiller of the ground; his need is for companionship, a lack which the Creator is anxious to fill...<br />

9<br />

(continued...)

4<br />

`~yIm'v'w> #r,a, These (are the) things brought forth (in) the heavens and the earth when they<br />

3<br />

(...continued)<br />

“Whereas in chapter 1 there was a distinctively polemical thrust challenging the accepted<br />

mythology of creation in the ancient Near East, this note is muted in chapters 2 and 3. Rather<br />

the writer appears to be using and adapting earlier motifs in a free and creative way to express his<br />

vision of reality...Thus Divine truths about man and his relationships with his Creator and his<br />

fellow creatures are presented in a vivid and memorable way.” (Pp. 52-3)<br />

Wenham quotes Otzen (Myths in the Old Testament, p. 25), as stating: “‘The narratives<br />

in the opening chapters of <strong>Genesis</strong> do not have the character of real myths.’ But the garden of<br />

Eden story does fulfill functions often associated with myths in other cultures. It explains man’s<br />

present situation and obligations in terms of a primeval event which is of abiding significance.<br />

Marriage, work, pain, sin, and death are the subject matter of this great narrative. And this narrative<br />

is replete with powerful symbols–rivers, gold, cherubim, serpents and so on–which hint at its<br />

universal significance...<br />

“...The author of these chapters identified the origin of the problems that beset all mankind<br />

–sin, death, suffering–with a primeval act of disobedience of the first human couple. Where a<br />

modern writer might have been happy to spell this out in abstract theological terminology–God<br />

created the world good, but man spoiled it by his disobedience--<strong>Genesis</strong> puts these truths in vivid<br />

and memorable form in an absorbing yet highly symbolic story.” (Pp. 54-55)<br />

What do you think? Do you hold the view that the stories in <strong>Genesis</strong> 1-11 are either<br />

historical, and factual, or meaningless and useless? Or do you hold the view that humanity’s<br />

myths contain some of the most precious and meaningful truths that ancient peoples perceived,<br />

and that they have passed down to their descendants?<br />

If you are persuaded to take the garden-story of <strong>Genesis</strong> 2-3 literally, do you also think<br />

that men have one less rib or side than women? Do you believe that serpents originally walked<br />

upright and talked with human beings? Do you believe that there was a literal tree whose fruit<br />

could impart eternal life to humans?<br />

NIVSB comments that while 1:1-2:3 is a “general account of creation...2:4-4:26 focuses on<br />

the beginning of human history.” (P. 8) TNISB states that in contrast to the earlier story, “here<br />

the scene is limited to a garden, and there is no indication of the time involved in the creation<br />

process...The order of creation is different...God is more immediate and personal, planting and<br />

shaping on the scene rather than commanding from a distance. <strong>In</strong> place of the formal, repetitious<br />

style of the first account, this is a dramatic story with interacting characters and a distinctive<br />

vocabulary.” (P. 9)<br />

4<br />

The Hebrew Book of <strong>Genesis</strong> is divided into eleven parts. The first part, 1:1-2:3 is the<br />

creation story, but is given no title as its heading in the Hebrew <strong>Bible</strong>. But the remaining ten<br />

parts are all given a title at their beginning, involving this unique Hebrew word tAdl.At, tholedhoth,<br />

which is feminine plural, and which means something like "offspring," or "productions,"<br />

or “those things (feminine) being given birth,” or perhaps, in a more general way, "stories of<br />

(continued...)<br />

10

4<br />

(...continued)<br />

descendants," or "generations,” or “birthings." Fox translates by “begettings.” We have chosen to<br />

translate by “things brought forth.”<br />

Sarna notes that "The tAdl.At hL,a, )elleh tholedhoth (‘these generations...or begettings...or<br />

record of events’) formula is one of the distinguishing characteristics of the Book of<br />

<strong>Genesis</strong>. <strong>In</strong> each of its other ten occurrences, it introduces what follows, invariably in close<br />

connection with the name of a person [or, we add, subject] already mentioned in the narrative."<br />

(P. 16)<br />

For the Hebrew phrase tAdôl.At hL,aeä, )elleh tholedhoth, “these (are) things brought<br />

forth,” the Greek translation has au[th h` bi,bloj gene,sewj, haute he biblos geneseos, “this (is)<br />

the scroll (or ‘book’) of birth (or ‘becoming’), changing from the plural “these” to the singular “this,”<br />

and understanding our “things brought forth” to mean “book of birth (or ‘becoming’).” <strong>In</strong> fact, this<br />

Greek translation is the exact translation of the Hebrew text at <strong>Genesis</strong> 5:1, but is not a translation<br />

of this present text, in which the word for “book” does not appear.<br />

This is the first occurrence in <strong>Genesis</strong> of the phrase tAdôl.At hL,ae, )elleh tholedhoth,<br />

and here it occurs in the title of a section of material–as similar phrases using this feminine plural<br />

noun do on nine other occasions throughout the book:<br />

<strong>Genesis</strong> 2:4 (here), tAdôl.At hL,aeä, (elleh tholedhoth, these (are) things brought forth by the<br />

heavens and the earth;<br />

<strong>Genesis</strong> 5:1, tdoßl.AT rp,se ê hz, we)elleh toledhoth, and these (are) things brought forth by the<br />

sons of Noah (compare 10:32);<br />

<strong>Genesis</strong> 11:10, tdoål.AT hL,ae…, elleh toledhoth, these (are) things brought forth by Shem;<br />

<strong>Genesis</strong> 11:27, tdoål.AT ‘hL,ae’w>, we)elleh toledhoth, and these (are) things brought forth by<br />

Terach;<br />

<strong>Genesis</strong> 25:12, tdoål.AT ‘hL,ae’w>, we)elleh toledhoth, and these (are) things brought forth by<br />

Yishael (compare 25:13);<br />

<strong>Genesis</strong> 25:19, tdoål.AT ‘hL,ae’w>, we)elleh toledhoth, and these (are) things brought forth by<br />

Isaac;<br />

<strong>Genesis</strong> 36:1, tdoål.AT ‘hL,ae’w>, we)elleh toledhoth, and these (are) things brought forth by<br />

Esau;<br />

(continued...)<br />

11

5 6 7 8 9<br />

were created, on (the) day (of) YHWH God’s making earth and heavens:<br />

4<br />

(...continued)<br />

<strong>Genesis</strong> 36:9, tdoål.AT ‘hL,ae’w>, we)elleh toledhoth, and these (are) things brought forth by<br />

Esau;<br />

<strong>Genesis</strong> 37:2, tAdål.To hL,aeä, elleh toledhoth, “these (are) things brought forth by Jacob.<br />

We believe that these are all headings of originally separate documents, lacking any statements<br />

concerning authorship or date of composition, which now in the final editing of <strong>Genesis</strong><br />

have been united together with this formulary title phrase in order to make one united document.<br />

Wenham comments that “...It is clear that in all cases [this phrase, which we translate<br />

‘and these (are) things brought forth by...’] describes what [a person] and his descendants did, not<br />

the origins of [the person]. Here [at <strong>Genesis</strong> 2:4] by analogy the [phrase] is applied to the heavens<br />

and the earth, and therefore ‘must describe that which is generated by the heavens and the<br />

earth, not the process by which they themselves are generated’ (Skinner, p. 41). <strong>In</strong> other words,<br />

2:4 makes an excellent title for what follows, but in no way can it be regarded as a postscript to<br />

what precedes it.” (P. 56)<br />

We agree with Wenham, and are taking verse 4 as the introductory statement to the<br />

following story in chapters 2-4.<br />

See Hamilton, pp. 150-51 for a discussion of this verse, as to whether it should be considered<br />

as belonging (as a sort of trailing summary statement) to the first chapter (1:1-2:3), or as the<br />

heading of chapters 2-4, and also for discussion of whether the verse should be divided, with the<br />

first part summarizing the story of 1:1-2:3, and the second half introducing the story of chapters<br />

3-4. <strong>In</strong> fact, the statement is rather disjointed, and can be taken in either way–as the history of<br />

exegesis shows. Fretheim seeks to combine both views, stating that “I construe it as a hinge<br />

verse that looks both backward and forward...” (P. 349)<br />

Westermann holds that 2:4a is the title of 1:1-2:3, here coming at the close of the story,<br />

rather than at the beginning, as it clearly does elsewhere in <strong>Genesis</strong>. He states that “What is<br />

described in 1:1-2:4a is the #r,a'h'w> ~yIm;V'h; tAdl.At, tholedhoth hashshamayim we<br />

ha)arets, the generations of [our ‘things brought forth by’] the heavens and the earth.” (P. 81)<br />

Many scholars have agreed with this conclusion, as is shown in the different Christian and<br />

Jewish translations of the verse (see the next footnote). However, we think that this feminine<br />

plural noun means “the things produced by,” “the productions of,” or “things brought forth by,” and<br />

then the content of those “birthings” or “things brought forth” is given in the words or story or<br />

stories that follow. <strong>Genesis</strong> 1:1-2:3 is the story of the origin of the heavens and the earth, not the<br />

story of the heavens’ and the earth’s “productions.” If Westermann’s view is correct, this is the<br />

only place in <strong>Genesis</strong> where the phrase is used to refer to a previous story.<br />

What do you think?<br />

12

5<br />

Westermann is not the only scholar who has divided verse 4 at this point, with 4b being seen<br />

as distinct from 4a, and forming the introductory sentence to the story of <strong>Genesis</strong> 2-3. King<br />

James, JPS 1917, New King James and New American Standard do not divide the sentence;<br />

but New <strong>In</strong>ternational, New Revised Standard, New Jerusalem and Tanakh all divide the<br />

sentence into two parts, implying the beginning of a new section with the second half of the verse.<br />

4b is translated by Westermann “When Yahweh God made earth and the heavens–there<br />

was not yet any plant of the field...” (P. 181), and describes this phrase as the important opening<br />

words of the “J” document. As Wenham notes, “Commentators who regard verse 4b as the start<br />

of the J source draw attention to the verbal parallel with the opening line of Enuma Elish. Enuma<br />

means ‘when, in the day.’” (P. 56)<br />

The two phrases introduced by B., be, ~a'_r>B")hiB., behibbar)am, “when they were created,”<br />

and ~yIm")v'w> #r,a,î ~yhiÞl{a/ hw"ïhy> tAf±[] ~Ay©B., beyom (asoth yhwh )elohiym )erets<br />

weshamayim, “on (the) day of YHWH God’s making earth and heavens,” may easily be taken as<br />

coordinates, using the two verbs ar'äB', bara) and hf'[', (asah as synonyms, just as they have<br />

appeared in the first story, side by side. As previously stated, we think the noun tAdl.At, tholedhoth<br />

means something like “things brought forth,” and points to the things contained in the<br />

material that follows.<br />

Here, then, we conclude, in <strong>Genesis</strong> 2:4 as a whole we have the introduction to this second<br />

story of <strong>Genesis</strong> which is given in the remainder of chapters 2-4, and which tells us some of<br />

the most important “things brought forth” by the heavens and the earth, from the viewpoint of the<br />

entire human race–including the giving birth to sin, suffering, murder, and universal death, as it<br />

tells the story of human crime and its Divine punishment. Why do these very bad things exist in<br />

God’s very good creation? It is because of human disobedience to God’s command!<br />

6<br />

Those who take the position that the seven days of 1:1-2:3 are to be understood lliterally of 7<br />

24-hour days, need to ask what is the meaning of this present statement, “on the day of YHWH<br />

God’s making earth and heavens”? Are we to understand this day as one 24-hour day? Or is the<br />

author summing up the seven days of the earlier story in terms of one day? What do you think?<br />

7<br />

<strong>In</strong> chapter 1, God is pictured as far above the universe, simply speaking his word of command,<br />

and the creation results (but the Spirit of God is also pictured as being immanent in the<br />

universe, hovering over the face of the waters).<br />

Now, beginning in 2:4, ~yhil{a/ hw"hy>, YHWH God (notice this new name for God,<br />

combining the masculine plural noun ~yhil{a, )elohiym used in chapter 1 with the singular<br />

Divine personal name, hw"hy>, YHWH–a “unity in plurality”--is pictured in a very human-like way,<br />

as a great "Potter" Who stoops to gather up clay, then shape it into the physical form of a human<br />

being, and then breathe His Own breath into it, imparting life.<br />

(continued...)<br />

13

7<br />

(...continued)<br />

Such a contrast is no problem for those who understand these stories in a symbolical way,<br />

without attempting to read exact, literal, "scientific-like," chronological, historical reports from<br />

them. But for those who demand such a literalistic, historical understanding, and demand that<br />

both stories be "harmonized" in all their details, these contrasts can be overwhelming.<br />

Biblical Theology holds these two pictures of God (as both "transcendent" and "immanent")<br />

in tension. God is not a human being; He is far above and beyond any such earthly limitations,<br />

dwarfing all humanity and the universe. But at the same time He is constantly present in human<br />

history, present with all His creatures, communicating with them, revealing Himself in human<br />

imagery, guiding them, blessing them, and judging them. The best way to picture the Divine reality<br />

(so that human beings can understand) is in terms familiar to all human beings. <strong>In</strong> this way,<br />

the student always knows that the biblical descriptions are almost always meant symbolically, not<br />

literally; but they are also meant very seriously--the transcendent God is also the immanent God--<br />

the God Who is far above and beyond human beings and all the created universe, is also the God<br />

Who is closely present with His human creatures, active in their history as both Maker, Judge and<br />

Savior.<br />

The Divine personal name hw"hy>, yhwh (which we transliterate by YHWH) is used over<br />

6,000 times in the Hebrew <strong>Bible</strong>. Until post-exilic times, it was commonly read and pronounced<br />

by the readers, and the name was commonly used by the Israelites in forming their personal<br />

names. They even shortened the Divine name with a sort of "nick-name," Yah, or even Yah-Yah.<br />

But later, post-exilic Israelites superstitiously refused to pronounce the Divine name, fearing that it<br />

would cause their death to even so much as speak it. So, the original vowels used in the pronunciation<br />

of hwhy>, yhwh were eliminated, and in their place the vowels from the Divine title<br />

yn:doa], )adhonay, “My Lord,” or ~yhil{a/, )elohiym, “God,” were used, making the name YHWH<br />

impossible to accurately pronounce, as spelled by the Massoretes. The grotesque non-Hebraic<br />

pronunciation Jehovah was the result. Though we do not know for sure how the Divine name<br />

YHWH was originally pronounced in Hebrew, we know for certain it was not pronounced "Jehovah.”<br />

Probably it was pronounced "Yahweh"; or, possibly, "Yihweh," or even "Yehawweh." But<br />

the evidence from its usage in Hebrew personal names, and from its shortened forms, point to the<br />

pronunciation, "Yahweh." See on the <strong>In</strong>ternet, Wikipedia’s article “Tetragrammaton.”<br />

Sarna holds that the name’s “simplest interpretation...is ‘He Who Causes To Be.” Sarna<br />

adds that this name “expresses God’s personality, His relationship to human beings, and His<br />

immanence in the world.” (P. 40) NIVSB states concerning the name YHWH that it emphasizes<br />

“His role as Israel’s Redeemer and covenant Lord.” (P. 8).<br />

We think that both Sarna and NIVSB are here over-stating the evidence, and that the<br />

Divine name means “He Will Cause to Be,” not only by bringing into existence in the beginning (as<br />

in <strong>Genesis</strong> 1:1-2:3) but in the history of the world, in which God is active, continually causing<br />

things to happen, as in the first family.<br />

(continued...)<br />

14

7<br />

(...continued)<br />

When the Hebrew <strong>Bible</strong> was translated into Greek (from the late fourth to the second<br />

centuries B.C., following the conquest of the Near East by Alexander the Great), the translators<br />

could not find a satisfactory way to translate this Divine name--and rather than confuse their<br />

Greek readers, decided to replace it with ku,rioj, "Lord." Thus, instead of being translated as a<br />

personal name, it was exchanged for a title, used commonly in Greek history for kings and slaveowners.<br />

<strong>In</strong> the New Testament, Jesus is given this Divine title, o` ku,rioj, ho kurios. The earliest<br />

Christian confession was exactly this: “Jesus Christ is Lord”–Philippians 2:11). We think that<br />

one of the central affirmations of this usage is that YHWH, the God of Israel, is present personally<br />

in Jesus. It is an amazingly high claim for Jesus; but this is the best explanation of the evidence.<br />

What do you think?<br />

<strong>In</strong> addition, [;vuAhy>, Yehoshua), “Joshua” in Hebrew, translated by the Greek as VIhsou/j,<br />

the name of “Jesus” in the New Testament, means literally, "YHWH Is Salvation," and is the<br />

name of Jesus because YHWH's saving right relationship is embodied in Him. Readers of the<br />

Hebrew <strong>Bible</strong>, with its constant use of YHWH as the name of God, who come to the New Testament,<br />

wonder where the name of YHWH has gone–since it never occurs in the Greek New<br />

Testament. We hold that the name is present every time the name of Jesus is mentioned–that<br />

Jesus is in fact “YHWH’s Salvation.” Do you agree?<br />

Throughout <strong>Genesis</strong> 1:1-2:3 we have witnessed the constant use of the Divine name<br />

~yhil{a/, )elohiym, “God,” the plural noun with singular verbs. Now we see the appearance of<br />

the Divine name ~yhil{a/ hw"hy>, yhwh )elohiym, “YHWH God.” It seems obvious that this<br />

change in terminology for describing the Deity is an indication of different authorship from that of<br />

chapter one, where only the name ~yhil{a/, )elohiym, “God” occurs. This makes it apparent, we<br />

think, that here a new source document has been brought into the final edition of <strong>Genesis</strong>.<br />

Hamilton accounts for this change in the Divine name as follows: “...It is no secret that in<br />

the religions of the ancient Near East compound names were used to designate one God...Amon-<br />

Re in Egypt and Kothar (-wa-) Chasis at Ugarit. This phenomenon also existed in Israel, as illustrated<br />

by Yahweh-Elohim. But why should it suddenly surface in 2:4a and disappear shortly<br />

thereafter?” This designation for Deity is used consistently throughout the remainder of chapter 2<br />

and chapter 3, but curiously enough the combination disappears in chapter 4, and occurs in the<br />

Pentateuch only once more, at Exodus 9:30.<br />

For all of the occurrences of this double-name in the Hebrew <strong>Bible</strong>, see: <strong>Genesis</strong> 2:4, 5,<br />

7, 15, 18, 21; 3:1, 8, 13, 21; Exodus 9:30; beyond the Pentateuch, see 2 Samuel 7:25; 2 Kings<br />

19:19; 1 Chronicles 17:16, 17; 28:20; 2 Chronicles 1:9; 6:41, 42; Psalms 59:6; 72:18; 80:5,<br />

20; 84:9, 12 and Jonah 4:6.<br />

(continued...)<br />

15

7<br />

(...continued)<br />

Westermann comments that “The combination Yahweh-Elohiym, which occurs here for the<br />

first time, serves, as does the whole sentence, to clamp together the two creation narratives in<br />

chapter 1 and chapter 2.” (P. 199) We would add that this unique name for the Deity also<br />

serves to clamp together chapters 2 and 3 as well.<br />

Wenham notes that “The strangeness of the phenomenon has taxed the imagination of<br />

literary critics and exegetes alike, for whether one accepts the usual documentary analysis or not,<br />

the commentator must still explain why here the editor of this finely constructed tale has forsaken<br />

his usual policy of using one name or the other and instead uses both together.” (P. 56) And, we<br />

add, then drops the double name in chapter 4.<br />

What do you think?<br />

8<br />

Here the qal infinitive construct verb tAf[], (asoth, “to make” is used as a synonym for the<br />

earlier verb used in this sentence, the niphal infinitive construct ~a'r>B'hiB., behibbar)am, “when<br />

they were created.” The Greek translation does not reflect these two verbs, but has only the one<br />

verb, evpoi,hsen, epoiesen, “He made.” It seems, from the number of occurrences of the two<br />

verbs in description of the same reality, that they are used by the author of <strong>Genesis</strong> as synonyms.<br />

9<br />

While the Hebrew text reads ~yIm'v'w> #r,a,, )erets weshamayim, “earth and heavens,” the<br />

Samaritan Pentateuch reads #raw ~ymv, shamayim we)erets, “heavens and earth,” and<br />

the Greek translation likewise reads ouvranou/ kai. gh/j, ouranou kai ges, “of heaven and of<br />

earth,” reverting to the order of <strong>Genesis</strong> 1:1.<br />

The story of creation in chapter one is told from “heaven’s viewpoint,” while the story in<br />

chapters two-three is told from an earthly, human viewpoint. Perhaps this is the reason for the<br />

reversed order of this phrase.<br />

This phrase, ~yIm'v'w> #r,a,, )erets weshamayim, “earth and heavens” (and the variant<br />

readings as well), is the equivalent of “the universe”–the totality of everything that is. Compare<br />

Psalm 148:13, the only other place where the two words occur in this order. But also see the<br />

following passages where the two words occur in the reverse order, #r,a,w.~yIm'v', shamayim<br />

we)erets, “heavens and earth”:<br />

<strong>Genesis</strong> 2:1, 4; 14:19, 22;<br />

Exodus 20:11; 31:17; 32:13;<br />

Deuteronomy 3:24; 4:26; 10:14; 11:21; 30:19; 31:28;<br />

2 Kings 19:15;<br />

Isaiah 37:16; 55:9;<br />

(continued...)<br />

16

10<br />

2.5 yKi xm'c.yI ~r,j, hd,F'h;bf,[e-lk'w> #r,a'b' hy #r,a'h'-l[; ~yhil{a/ hw"hy> ryjim.hi al{ And every<br />

11 12<br />

plant of the field will not yet be in the earth, and all vegetation of the field will not yet sprout.<br />

9<br />

(...continued)<br />

Jeremiah 23:24; 32:17; 33:25; 51:48;<br />

Joel 4:16;<br />

Haggai 2:6, 21;<br />

Psalms 69:35 (verse 34 in English); 102:20 (verse 19 in English); 113:6; 115:15; 121:2; 124:8;<br />

134:3; 135:6; 146:6;<br />

Lamentations 2:1;<br />

1 Chronicles 29:11;<br />

2 Chronicles 6:14.<br />

10<br />

Westermann observes that “Verses 4b-6 comprise the antecedent, verse 7 is the main<br />

statement, which is continued in verse 8...The sentence verse 5 contains two pieces of information<br />

about what was not yet there, and two reasons for it...The only function of the information in<br />

verse 5 is to introduce the main sentence in verse 7 in such a way as to qualify it chronologically.<br />

The four negative sentences taken together determine the time of the creation of humanity as<br />

primeval [i.e., original, pre-historic, ‘mythical’] time. It is not so important to say what it was that<br />

did not yet exist, but only to express clearly that reality as we know it was not yet.” (P. 199)<br />

Wenham notes that the text has “four conjoined circumstantial clauses describing the situation<br />

prior to God’s creation of man in verse 7. But the interpretation of verses 5-6 is difficult:<br />

Some...regard verse 5 as describing the whole earth as a desert...<br />

Others...argue that the creation of chapter 1 is presupposed and therefore 2:5-6 are stating what<br />

agricultural land was like before man started farming.<br />

A third view...argues that the main interest is to contrast the situation before man’s arrival (2:5-6)<br />

with that after his creation and disobedience (3:17-24)...” (P. 57)<br />

What do you think?<br />

11<br />

The noun x;yfi, siyach, “bush,” “shrub,” “plant,” is found here and three other places in the<br />

Hebrew <strong>Bible</strong>: <strong>Genesis</strong> 21:15; Job 30:4 and 7. It refers to some kind of desert shrub, beneath<br />

which the weary, thirsty traveler could find rest. This word is not found in the opening chapter of<br />

<strong>Genesis</strong>.<br />

We think it is a mis-guided attempt to seek to harmonize the opening story in <strong>Genesis</strong> 1-<br />

2:3 with this second story in chapters 2:4-3:24; similarly, we think that it is a misguided attempt to<br />

(continued...)<br />

17

For YHWH God did not cause rain upon the earth, and there is no human being to work the<br />

11<br />

(...continued)<br />

hold that the two stories are contradictory. They are very distinct stories, told for quite different<br />

purposes; and the attempt to make them into one harmonious story does not do justice to either<br />

of them.<br />

The opening story points to the transcendent [‘above and independent of the material<br />

universe’] God Who has created the entire universe “very good,” and Who has called upon His<br />

creation to share with Him in His works of creation.<br />

This second story points to the immanent God, Who is closely related to the humans He<br />

has made, and teaches that it is the humans, not God, who are responsible for bringing suffering<br />

and death into the paradise-like world which God has given them.<br />

Both stories have very important theological teaching to give; but that teaching becomes<br />

muted when the stories are amalgamated into one story, or when the two stories are set in<br />

opposition to each other.<br />

What do you think? Have you been taught, or do you attempt, to combine the two stories<br />

into one unified story? How successful do you think this is?<br />

12<br />

The author’s use of two imperfect (future) verbs, hy

13 14<br />

ground. 2.6 `hm'd'a]h'-ynEP.-lK'-ta, hq'v.hiw> #r,a'h'-!m hl,[]y: daew>i And a mist would<br />

13<br />

Fox translates by “and there was no human / adam to till the soil / adama–“ noting that “The<br />

sound connection, the first folk etymology in the <strong>Bible</strong>, establishes the intimacy of humankind with<br />

the ground...Human beings are created from the soil, just as animals (are (verse 10). Some have<br />

suggested ‘human...humus’ to reflect the wordplay.” (P. 19)<br />

Here, the story leaves off the imperfect, “future” verbs–there is no human being to work the<br />

ground–in this ideal picture that the author wants the reader to have in mind.<br />

Hamilton comments that “The scene described here is that of a barren desert. There is<br />

neither shrub nor plant in the fields. Two factors account for this emptiness. God is not doing<br />

what He is accustomed to doing–sending rain. Nor is there a man to till the soil, something that<br />

he will do when he arrives on the scene. If plant life is to grow in this garden, it will be due to a<br />

joint operation. God will do His part and man will expedite his responsibilities. Rain is not sufficient.<br />

Tillage is not sufficient. God is not a tiller of the soil and man is not a sender of rain. But<br />

the presence of one being without the other guarantees the perpetuation of desert like conditions.”<br />

(Pp. 153-54)<br />

This is a strange comment, considering that in many parts of the world, where for ages<br />

there were no human beings to till the soil, vast rain-forests and tropical gardens have still grown<br />

as a result of the Divine gift of life-imparting rain. What do you think?<br />

14<br />

The masculine singular noun dae, )edh, probably “mist,” is translated into Greek by phgh.,<br />

pege, “fountain,” “spring,” or “well” (so also in the Latin Vulgate, fons, “spring”). The Hebrew<br />

noun occurs elsewhere only at Job 36:27, where it is translated by u`etou/, huetou, “(of) rain.” But<br />

the fact that it is described as “going up from the earth” forces us to think in terms of a heavy mist<br />

arising from the ground, or of some subterranean source of water such as a spring, i.e., a “rain”<br />

that ascends rather than descends.<br />

See Hamilton, pp. 154-55 where he mentions the possible interpretations, “subterranean<br />

freshwater stream,” “flood,” “waves,” “swell,” or “heavy rain.” He states that “Historical support for<br />

the idea of an underground river that overflows its bank and seeps to the surface may be found in<br />

the tradition preserved by Strabo that the Euphrates, or some branch of it, flowed underground<br />

and subsequently surfaced to form lagoons beside either the Persian Gulf or the Mediterranean<br />

Sea.” (P. 155)<br />

Wenham translates verse 6 by “But the fresh water ocean used to rise from the earth and<br />

water the whole surface of the land.” He states that “Here again a Mesopotamian background<br />

seems likely. <strong>In</strong> this area agriculture was totally dependent on controlling the annual floods of the<br />

Tigris and Euphrates...<br />

“Whatever the origin of the word, the concept of an underground stream watering the earth<br />

is attested in Sumerian mythology: ‘From the mouth whence issues the waters of the earth...<br />

brought her sweet water from the earth...her furrowed fields and farms bore her grain (Enki and<br />

Ninhursag, 55-61, ANET, p. 38)...It is preferable to follow Castellino and Gispen, who put down<br />

(continued...)<br />

19

15<br />

go up from the earth, and it would water all the face of the ground. 2.7 ~yhil{a/ hw"hy> rc,yYIw:<br />

`hY"x; vp,n

16<br />

(...continued)<br />

potamian texts, in particular, repeatedly feature this notion, as does the Greek myth about Hephaestus,<br />

who molded the archetypal woman Pandora from earth." (P. 17)<br />

Sarna adds that "Here in <strong>Genesis</strong>, the image [of the Potter and the clay] simultaneously<br />

expresses both the glory and the insignificance of man. Man occupies a special place in the hierarchy<br />

of creation and enjoys a unique relationship with God by virtue of his being the work of<br />

God's Own hands and being directly animated by God's Own breath. At the same time, he is but<br />

dust taken from the earth, mere clay in the hands of the Divine Potter, Who exercises absolute<br />

mastery over His Creation." (Ibid.)<br />

Here, we think, the author uses perfect verbs, to describe what happened in that ideal<br />

place he has been describing.<br />

And once again the singular verb rc,yYIw:, wayyitser, “and he shaped (or molded),” is used<br />

with the plural noun (YHWH) )elohiym. This verb, as Westermann notes, occurs 63 times in the<br />

Hebrew <strong>Bible</strong>, and 43 of those occurrences have God as its subject. God “forms” or “molds”<br />

humans, animals, dry land, mountains, summer and winter, and light. The verb describes God’s<br />

creative work at the beginning as well as in history and in the present.” (P. 203)<br />

<strong>In</strong>stead of the transcendent ‘~yhil{a/, )elohiym of chapter one, Who speaks and it is done<br />

(but Who also “makes”), here YHWH God is pictured as a “Potter,” stooping to take up “dust,”<br />

then, we assume, moistening it (Hamilton’s insistence on a distinction between “dust” and “clay,”<br />

p. 156, is too subtle, we think), turning it into clay, then shaping it into the form of a human being–<br />

and then breathing His Own breath into the clay figurine, causing it to come to life.<br />

Hamilton notes that “...Neither the concept of the Deity as Craftsman nor the concept of<br />

man as coming from earthy material is unique to the <strong>Bible</strong>. For example, from ancient Egypt we<br />

have a picture of the ram-headed God Khnum sitting on His throne before a potter’s wheel, on<br />

which He fashions the prince Amenhotep III (about 1400 B.C.) and his ka (an alter ego which protected<br />

and sustained the individual)...<br />

“Mesopotamian literature provides numerous examples of man’s derivation from clay...<strong>In</strong><br />

the Gilgamesh Epic...the nobles of Uruk pester the Gods and ask them to create one equal in<br />

strength to the oppressive Gilgamesh. The Gods then ask Aruru the creator to make a counterpart<br />

to Gilgamesh: ‘Thou, Aruru, did create [the man]; create now his double...When Aruru heard<br />

this, a double of Anu she conceived within her. Aruru washed her hands, pinched off clay and<br />

cast it on the steppe. On the steppe she created valiant Enkidu.<br />

“A sister composition to the Gilgamesh Epic is the Atrahasis Epic, another literary tradition<br />

about the creation and early history of man. As in Enuma Elish, here too man is created to<br />

relieve the Gods of heavy work. His creation is described as follows: ‘We-ila (a God), Who had<br />

personality, they slaughtered in their assembly. From His flesh and blood Nintu mixed clay...After<br />

She had mixed that clay She summoned the Anunnaki, the great Gods. The Igigi, the great<br />

(continued...)<br />

21

16<br />

(...continued)<br />

Gods, spat upon the clay. Mami opened Her mouth and addressed the great Gods, ‘You have<br />

commanded Me a task, I have completed it; You have slaughtered a God together with His personality.<br />

I have removed Your heavy work, I have imposed Your toil on man.’” (Pp. 157-58)<br />

The <strong>Genesis</strong> 2 story is highly symbolic in nature–or should we understand the story literally,<br />

of YHWH God stooping in an earthly garden to take up moist clay in His hands to form the<br />

first human being? Surely if we call the Egyptian and Greek stories of such Divine action “mythical,”<br />

we must admit that here also we are dealing with the biblical “myth”–not falsehood, but the<br />

biblical teaching concerning our human origin, clothed in the common language of myth.<br />

What do you think? The author of these notes has been told that if he thinks the biblical<br />

story is in fact a “myth,” then he is saying the biblical story is false. But this is not the case–he<br />

believes that the biblical story is the “true myth,” over against many other stories concerning the<br />

origin of humanity, which he thinks are relatively false. Do you agree? Why? Why not?<br />

Westermann comments on all of this ancient tradition of God forming humanity out of clay<br />

that “The creation of human beings...is presented as an inexplicable, indescribable and wonderful<br />

process. It is primeval event, and as such not accessible to our understanding, just like creation.<br />

This description of the creation of human beings out of earth has come down to the [author]<br />

through the millennia, and his intention is simply to point out how inaccessible to us is the event.”<br />

(P. 205)<br />

What Westermann means is that we have no way of getting, and do not have, a literal,<br />

exact description of humanity’s formation–only this kind of mythical, symbolical story. Do you<br />

agree? Do you think modern science has a better, more factual story to tell concerning the origin<br />

of human life–apart from “mythical” elements?<br />

Wenham comments that “‘Shaping’ is an artistic, inventive activity that requires skill and<br />

planning (compare Isaiah 44:9-10 [and its continuation through verse 17, with its description of<br />

the work of both an iron-worker and a carpenter, working carefully with their tools]).” (P. 59)<br />

Anyone who carefully observes the marvelous nature of the human body / mind combination,<br />

with its intricate genetic origin guided by the DNA code, cannot help but tremble in awe<br />

before the obvious skill and planning and intelligence–far greater than our human capabilities--<br />

that have gone together in the formation of a human being. Do you agree? If you are a parent,<br />

what are the feelings and realizations that you had when your first child was born? Did you<br />

attribute it all to your own intelligence and physical prowess? Or were you filled with awe and<br />

wonder?<br />

17<br />

The phrasehm'd'a]h'-!mi rp'[', (aphar min-ha)adhamah, “dust from the ground,” is trans-<br />

lated cou/n avpo. th/j gh/j, choun apo tes ges, “mound (of dirt) from the earth” by the Greek.<br />

This teaching concerning human origin “from dust” (or “dirt”) is emphasized in biblical literature–see<br />

elsewhere:<br />

(continued...)<br />

22

18 19<br />

life’s breath; and the human being became a live animal. 2.8/ !G: ~yhil{a hw"hy> [J;YIw:<br />

17<br />

(...continued)<br />

<strong>Genesis</strong> 3:19, you are dust, and to dust you will return;<br />

Job 4:19, human beings are those who live in houses of clay, whose foundation is in the dust;<br />

Job 10:9, remember that You fashioned me like clay; and will You turn me to dust again?;<br />

Psalm 103:14, He knows how we were made; He remembers that we are dust;<br />

Psalm 104:29, when You take away their breath, they die and return to the dust;<br />

Ecclesiastes 3:20, all go to one place; all are from the dust, and all turn to dust again;<br />

Ecclesiastes 12:7, the dust returns to the earth as it was, and the breath / spirit / Spirit returns to<br />

God Who gave it.<br />

<strong>In</strong> the New Testament, see especially 1 Corinthians 15:47-49, and the new adjective<br />

(perhaps coined by Paul), o` prw/toj a;nqrwpoj evk gh/j coi?ko,j, ho protos anthropos ek ges<br />

choikos, “the first person–out of earth, of dust.” The Greek adjective coi?ko,j, choikos is related<br />

to the noun cou/n, choun used by the Greek translation of this verse, <strong>Genesis</strong> 2:7.<br />

Hamilton comments that “Nowhere does <strong>Genesis</strong> 2 imply that dust is to be understood as<br />

a metaphor for frailty.” (P.158) We disagree. What other metaphor could be used in the story<br />

that would better emphasize the weakness and frailty of human beings?<br />

Wenham notes that there is a play on the two terms ~d'ªa'h', ha)adham, “the man,” and<br />

hm'êd'a]h'ä, ha)adhamah, “the earth.” He thinks this emphasizes “Man’s relationship to the land.<br />

He was created from it; his job is to cultivate it (2:5, 15); and on death he returns to it (3:19). ‘It is<br />

his cradle, his home, his grave’ (Jacob)...This play on similar sounding words...is a favorite device<br />

of Hebrew writers...” (P. 59)<br />

18<br />

The phrase, ~yYIx; tm;v.nI, nishmath chayyim, literally, “breath of lives,” is translated into<br />

Greek by the phrase pnoh.n zwh/j, pnoen zoes, “a breath (or ‘blast’) of life.”<br />

Hamilton notes that “<strong>In</strong>stead of using x;Wrå, ruach for ‘breath’ [or ‘spirit,’ or ‘wind,’ or ‘Spirit’]<br />

(a word appearing nearly 400 times in the Hebrew <strong>Bible</strong>), <strong>Genesis</strong> 2:7 uses hm'v'n>, neshama<br />

(which occurs some 25 times in the Hebrew <strong>Bible</strong>). Unlike x;Wrå, ruach, which is applied to God,<br />

man, animals, and even false Gods, hm'v'n>, neshama is applied only to Yahweh and to man...<br />

Thus 2:7 may employ the less popular word for breath because it is man, and man alone, who is<br />

the recipient of the Divine breath. Now Divinely formed and inspired, he is a living person. Until<br />

God breathes into him, man is a lifeless corpse.” (P. 159)<br />

We think that hm'v'n>, neshama is a synonym of x;Wrå, ruach, and that this is a very weak<br />

basis for building a biblical distinction between human beings and animals.<br />

23<br />

(continued...)

18<br />

(...continued)<br />

We agree with Westermann in his comment that “The breath of life...means simply being<br />

alive, and the breathing in of this breath, the giving of life to humans, nothing more...And so there<br />

are no grounds for the opinion that God created humans immortal...The person created by God is<br />

a living person...A ‘living soul’ is not put into one’s body. The person as a living being is to be<br />

understood as a whole and any idea that one is made up of body and soul is ruled out. A person<br />

created as a living being means that one is a person only in one’s living state...” (P. 207)<br />

We think that Westermann is right at this point. The story depicts humanity as having been<br />

created mortal, but with the possibility of immortality, as Augustine taught, through eating of the<br />

tree of the lives, not because of the possession of breath / spirit / Spirit.<br />

Hamilton also comments that “<strong>In</strong> ancient Egypt, especially in the cult of Hathor (the Divine<br />

Mother of the king), young princesses appear before the king with several objects in their hands to<br />

present to him. As they present these objects they say: ‘May the Golden One (Hathor) give life to<br />

thy nostrils. May the Lady of the Stars unite herself with thee.’ <strong>In</strong> our comments on <strong>Genesis</strong><br />

1:26 we suggested that the application of the Divine image to ‘man,’ as opposed to the king,<br />

represented perhaps both a demythologizing of royal mythology and a democratization of society<br />

in Israel. Such would seem to be the case here too. It is man, as representative of subsequent<br />

humanity, who receives the Divine breath. It is not something only for the elite of society.” (Pp.<br />

158-59)<br />

We agree with this comment, but question whether the biblical statement raises humanity<br />

above the animals, as superior to them because of this Divine “breath.” NIVSB comments that<br />

“humans and animals alike have the breath of life in them.” P. 8)<br />

19<br />

Verses 6 and 7 supply the answer to the problem posed by verse 5. The problem is stated<br />

as consisting of there being no plants or vegetation, no rain and no human (verse 5); the answer<br />

is a mist to water the ground, and a living human being (verses 6-7).<br />

The phrase hY"x; vp,n

20<br />

`rc'y" rv,a] ~d'a'h'-ta, ~v' ~f,Y"w: ~d,Q,mi !d,[eB. And YHWH God planted a garden in<br />

21 22 23<br />

Luxurious Place, eastwards; and there He placed the human whom He shaped.<br />

19<br />

(...continued)<br />

“live animals” in verses 20, 21, 24, 30; 2:7 (here) and 19. The Greek is likewise the same as is<br />

found in those verses for a description of animals.<br />

Wenham comments that “Man is more than a God-shaped piece of earth. He has within<br />

him the gift of life that was given by God himself. The biblical writer was not alone in the ancient<br />

world in rejecting a reductionist view of man which sees him as simply an interesting collection of<br />

chemicals and electrical impulses.”<br />

He compares Ezekiel 37:9 where the spokesperson “is told to blow on the recreated<br />

bodies to resuscitate them, and then, filled with wind / spirit / Spirit (xwr), they stood alive. It is<br />

the Divine in-breathing both here and in Ezekiel 37 that gives life...Given the other uses of the<br />

phrase hY")x; vp,n

21<br />

(...continued)<br />

“paradise in Eden.” This makes it obvious that the early use of “paradise” simply means “garden,”<br />

or “park,” and it is only later that “paradise of God” begins to take on a decidedly religious sense.<br />

<strong>In</strong> <strong>Genesis</strong> 3:23-24, the Greek translation reads tou/ paradei,sou th/j trufh/j, tou paradeisou<br />

tes truphes, “(out) of the garden / paradise of the luxury”–which is, we think, an apt translation<br />

of the Hebrew !d,[e_-!G:, gan (edhen. Westermann paraphrases “the land of bliss” (p. 209;<br />

see his excursus on pp. 208-11).<br />

Wenham comments that “The use of the preposition ‘in’ shows that Eden is understood as<br />

the name of the area in which the garden was planted.” (1, p. 61)<br />

“Midrash HaGadol states, ‘A garden in Eden. A place on earth whose exact location is<br />

unknown to any human being.’ Some interpret !d,[e, (edhen as an adjective, and render -!G:<br />

!d,[e ÞB., gan-be(edhen ‘a garden in a place of delight’ (Radak; Rabbi Meyuchas) or: ‘a garden of<br />

delight,’ (HaRechasim leBikah).” (Bereishis 1, p. 94)<br />

Sarna comments that “Man’s first domicile is a garden planted by God. The narrative is<br />

very sparing of detail about its nature and function. Other biblical references indicate that a more<br />

expansive, popular story about man’s first home once circulated widely in Israel...Ezekiel 28:13,<br />

31 testify to the one-time existence of a tale about a wondrous ‘garden of God,’ rich in a large<br />

variety of precious stones, beautifully wrought gold, and an assortment of trees...Ancient Near<br />

Eastern literature provides no parallel to our Eden narrative as a whole, but there are some suggestions<br />

of certain aspects of the biblical Eden...<br />

“The Sumerian myth about Enki and Ninhursag tells of an idyllic island of Dilmun, now<br />

almost certainly identified with the modern island of Bahrein in the Persian Gulf. It is a ‘pure,’<br />

‘clean,’ and ‘bright’ land in which all nature is at peace, where beasts of prey and tame cattle live<br />

together in mutual amity. Sickness and old age are unknown. The Gilgamesh Epic likewise<br />

knows of a garden of jewels. It is significant that our <strong>Genesis</strong> account omits all mythological<br />

details, does not even employ the phrase ‘garden of God,’ and places gold and jewels in a natural<br />

setting” (i.e., outside the garden). (P. 18)<br />

We think Sarna’s comment is helpful, but over-stated. The <strong>Genesis</strong> story tells of a tree<br />

whose fruit imparts life, and a tree whose fruit imparts knowledge of good and evil, and a serpent<br />

that walks and talks. What do you think? Are those not “mythical” details?<br />

22<br />

YHWH God plants ~d,Q,mi !d,[eB.-!G;, gan-be(edhen miqqedhem, “a garden in Luxurious<br />

Place, eastwards.” These words are intriguing, and call for interpretation. Where is “a garden in<br />

Luxurious Place”? Does the author mean a specific country or geographical location by the name<br />

of !d,[e, (edhen, i.e., in a specific fertile (“luxurious”) plain in southeastern or northwestern Mesopotamia<br />

or on some beautiful shore of Arabia such as Bahrain? Or is this an example of biblical<br />

(continued...)<br />

26

22<br />

(...continued)<br />

“mythological language,” in which locations are named, but are impossible to pin-point on any<br />

map?<br />

And what is the meaning of ~d,Q,mi, miqqedhem, which we have translated “eastwards,”<br />

but which can also be understood as meaning “of old,” or “in ancient time” (Sarna holds that it can<br />

mean “in primeval times,” p. 18)?<br />

If the phrase means “eastwards,” we ask “eastwards from where?” And even if it be assumed<br />

that the phrase means “east of Israel,” we are still left with the question, “How far east?”<br />

Does it mean “Mesopotamia”? Persia? <strong>In</strong>dia? China? Is not such language closely akin to<br />

statements like “Long, long ago, in a kingdom by the sea”?<br />

We think that this is obviously “mythical” language, and that while the text speaks of a<br />

“geographical location,” it does not mean an actual, historical location on earth, but rather is<br />

setting the stage for an “ideal story,” the uniquely powerful biblical “story” or “myth” or “parable”<br />

concerning the origin of humanity, who once lived in the Luxurious Place of spiritual innocence<br />

and intimacy with YHWH God, but who lost that condition through disobedience to God’s command.<br />

Wenham comes to a similar conclusion, as he states that “It is simpler to associate Eden<br />

with its homonym ‘pleasure, delight.’ Whenever Eden is mentioned in Scripture it is pictured as a<br />

fertile area, a well-watered oasis with large trees growing...a very attractive prospect in the arid<br />

East...So it seems likely that this description of ‘the garden in Eden in the east’ is symbolic of a<br />

place where God dwells [no–where the first human being dwells!]. <strong>In</strong>deed, there are many other<br />

features of the garden that suggest it is seen as an archetypal sanctuary, prefiguring the later<br />

tabernacle and temples.” (P. 61)<br />

We ask, what are those ‘many features’? The mention of the winged-animals guarding its<br />

way, is the only feature that has connotations of Israel’s moveable sanctuary and Solomon’s<br />

temple. The story is not telling how YHWH God prepared a place for Himself to inhabit, or to be<br />

worship-ed, but rather, a place for His human creature to inhabit, with not one mention of an altar<br />

or of worship.<br />

ESVSB insists that <strong>Genesis</strong> 2 depicts the human’s beings as living in “the sanctuary of<br />

Eden,” assigned the task of “maintaining the sanctity of the garden as part of a temple complex.”<br />

(Pp. 52, 53) But we insist that this is being read into the text, not genuinely derived from it. What<br />

do you think?<br />

Wenham continues: “But the mention of the rivers and their location in verses 10-14<br />

suggests that the final editor of <strong>Genesis</strong> 2 thought of Eden also as a real place, even if it is<br />

beyond the wit of modern writers to locate.” (P. 62) To the contrary, we agree with Westermann<br />

that the very description of the rivers flowing out from Eden indicate the author’s use of Eden as a<br />

symbol, not a geographical location. It is somewhere, but nowhere known to the readers of the<br />

biblical story, either in ancient times or in the present.<br />

(continued...)<br />

27

22<br />

(...continued)<br />

For the occurrences of this noun !d,[e, (edhen in the Hebrew <strong>Bible</strong>, see:<br />

<strong>Genesis</strong> 2:8 (here), 10, 15; 3:23, 24 (all with reference to the first home of humanity);<br />

2 Samuel 1:24 (a plural, meaning luxurious clothes);<br />

Isaiah 51:3 (YHWH makes Israel’s wilderness like Luxurious Place);<br />

Jeremiah 51:34 (plural, with quite different meaning–“my luxuries”);<br />

Ezekiel 28:13 (an obviously mythological understanding as it describes the former dwelling-place<br />

of the Prince of Tyre on the Mountain of God);<br />

Ezekiel 31:9, 16, 18, 18 (obviously mythological language, comparing Pharaoh’s Egypt with the<br />

fallen nation of Assyria, as trees of Luxurious Place, the garden of God in Lebanon, being<br />

cast down by YHWH, into the world of the dead);<br />

Joel 2:3 (used in contrast with later desolation);<br />

Psalm 36:8 (YHWH’s people drink from the river of His “Luxurious Places,” obviously an ideal,<br />

symbolical usage);<br />

2 Chronicles 29:12; 31:15 (where it is a personal name).<br />

We think this evidence shows that the name “Eden” means “Luxurious Place,” not one<br />

specific geographical location, but rather an “ideal location,” where there is great plenty and<br />

peace, which becomes a symbol for the future hope of the people of God, as well as for their<br />

present experience of His goodness.<br />

The Sumerian myth of Enki and Ninhursag (see ANET, pp. 37-41, depicts such an “ideal<br />

place” called Dilmun, which was located “east of Sumer.” It is a land (or perhaps an island) that is<br />

pure, clean, and bright; there is no sickness nor death there, and all of the animals live together in<br />

harmony. Its water is sweet, and its fields are highly productive. This is one example among<br />

many others that can be found in world literature of such an “ideal place,” a “paradise,” which is<br />

not meant as a description of an actual geographical location, or if it is, cannot be located with<br />

certainty on any map. See Wikipedia on the <strong>In</strong>ternet, “Dilmun.”<br />

Hamilton asserts that “A number of factors in <strong>Genesis</strong> 2 suggest that the author presents<br />

his material in a way that is decidedly anti-mythical. Thus, we read of man’s creation (verse 7)<br />

before we read of the garden’s creation (verse 8). We do not read that the garden is a place of<br />

blissful enjoyment. If it is such a place, the text does not pause to make that observation. <strong>In</strong>stead,<br />

man is placed in the garden ‘to till it and keep it’ (verse 15).”<br />

But, why can’t a mythical story tell of humanity’s creation before the creation of a garden in<br />

which to place him? Has Hamilton established a rule that “all myths tell of humanity’s creation<br />

following the creation of luxurious gardens”? Does a mythical story have to describe God’s “garden”<br />

as a place of blissful enjoyment? And, in fact, in the overall story of <strong>Genesis</strong> 2-3, when<br />

humanity is driven out of the garden, does that not mean the loss of blissful enjoyment? And is<br />

there a rule that says “myths cannot tell of humanity’s being assigned work to do”?<br />

We think it more correct to assess the story of <strong>Genesis</strong> 2-3 as the biblical mythology or<br />

ideal story of human origins, and marriage, and the origin of suffering and death in God’s good<br />

(continued...)<br />

28

2.9 lk'a]m;l.bAjw> ha,r>m;l. dm'x.n< #[e-lK' hm'd'a]h'-!mi ~yhil{a/ hw"hy> xm;c.Y:w:<br />

22<br />

(...continued)<br />

earth. The story is only “anti-mythical” in that it seeks to correct mistaken ideas of the nature and<br />

value of work, the subordination of women to men, and the attribution of the origin of evil to “outside<br />

forces,” rather than to human desire and mistaken choices. Such indications of time and<br />

place as are found in the story speak of no one specific geographical location or calendar date.<br />

They place the reader beyond time and place, and the story that is told deals with that which is<br />

universal and constant (‘typical’) in God’s human creature. This is every reader’s story, our story–<br />

he story of “everyone.” Adam is “Everyman”; and Eve is “Everywoman.” <strong>In</strong> this way, the story told<br />

in <strong>Genesis</strong> 2:4-3:24 achieves “universal” meaning, and cannot legitimately be interpreted in<br />

terms of nationalism–such as has been seen in Hitler’s cult of the Germanic blood and soil.<br />

No, while the ancient story gives geographical details, it is impossible to tie them down to<br />

any certain location known today or in the past. Compare 2:10-14, with its description of two<br />

known rivers, and two completely unknown rivers.<br />

Westermann states that "The intention is not to fix the area geographically but to push the<br />

scene of the event into the far, unknown distance...This is a fixed stylistic trait of narratives of this<br />

kind and it occurs elsewhere," as in <strong>Genesis</strong> 11:2.<br />

Do you agree with Westermann? Why? Why not?<br />

<strong>In</strong> the Egyptian cosmologies or stories of creation, by contrast, the exact geographical<br />

"place of creation" is oftentimes given--for example, at Heliopolis, or Hermopolis, or at Thebes--<br />

thereby pointing to these temple-cities as especially sacred centers of worship, and as the “navel”<br />

of the earth. However, the story told in <strong>Genesis</strong> 2-3, which comes from Israel, makes no reference<br />

to the land of Israel, or to Jerusalem, or to Mount Zion, the location of the Solomon’s tem-ple<br />

built for the worship of YHWH God, and says nothing concerning the “navel of the earth.”<br />