Bauhaus Construct - Institut für Kunst

Bauhaus Construct - Institut für Kunst

Bauhaus Construct - Institut für Kunst

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Bauhaus</strong> <strong>Construct</strong><br />

Fashioning Identity, Discourse<br />

and Modernism<br />

Edited by Jeffrey Saletnik and<br />

Robin Schuldenfrei

2.1<br />

Otto Rittweger<br />

and Wolfgang<br />

Tümpel, Stands<br />

with Tea Infusers,<br />

1924, German silver<br />

(Photograph by<br />

Lucia Moholy, 1925,<br />

printed c. 1950),<br />

gelatin silver print,<br />

12.8 × 17.9 cm<br />

(5 1⁄16 × 7 1⁄16 in)<br />

Chapter 2<br />

The Irreproducibility of<br />

the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> Object<br />

Robin Schuldenfrei<br />

Objects produced at the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> occupy an uneasy juncture between the<br />

canonical history of modern art and architecture, period culture, and issues<br />

such as the production and consumption of modernism. 1 In 1923, Walter<br />

Gropius articulated the aims of the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> with the proclamation, “art and<br />

technology—a new unity,” which advanced the use of new materials, more<br />

stripped-down forms, and a spare, functional aesthetic. His successor Hannes<br />

Meyer pronounced instead: “people’s needs instead of luxury needs”<br />

37

Robin Schuldenfrei<br />

(Volksbedarf statt Luxusbedarf)—but would he have been moved to make<br />

such a declaration if Gropius had successfully carried out his stated aims?<br />

The failure of Gropius’s <strong>Bauhaus</strong> to merge art and technology—to move from<br />

the production of individual, luxury objects to mass reproduction—is the subject<br />

of this essay. To be discussed are the objects produced under Gropius<br />

from 1923 to 1928, the period of his overtures to industry. This repertoire of<br />

specialized objects—including silver and ebony tea services, modern chess<br />

sets, and children’s toys, to name just a few canonical works—represents a<br />

paradigmatic example by which to examine the relationship between modernism’s<br />

discourse and its material results. Expensive in their day, original<br />

<strong>Bauhaus</strong> products are now art objects displayed in museum vitrines as individual<br />

works of art. Often hailed for the mythic merging of forward-thinking<br />

ideas and modern production techniques, they are asked to illustrate modernism’s<br />

unflinching belief in the powers of industry. And they are presented<br />

as objects of discourse, the material evidence of a series of debates on<br />

handcraftsmanship, machine production, and taste. This essay considers and<br />

contextualizes the ways in which the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> produced its modern objects<br />

and the extent to which, despite its egalitarian ideals, the school ultimately<br />

spoke to—and designed for—an elite. The products of the <strong>Bauhaus</strong>, ostensibly<br />

intended for mass production, were expensive, difficult to fabricate, and<br />

never sold on a widespread basis, reflecting the economic realities of producing<br />

and purchasing modern objects. Essential to this discussion is the problem<br />

of reproduction itself. Engaging Walter Benjamin’s essay “The Work of<br />

Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility,” this chapter will recognize<br />

that, ideologically, the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> protagonists were willing to call the status of<br />

the objects the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> produced into question—to sacrifice their “aura”<br />

and status as “art” in order to achieve their mass reproduction; yet, in practice<br />

the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> was unable to do so. 2 This failure was due to the limits to<br />

the reproducibility of <strong>Bauhaus</strong> objects—themselves a product of their place<br />

in the Weimar social order that they also sought to transform.<br />

Luxury Objects<br />

Upon first glance the small teapot designed and executed in 1924 by Marianne<br />

Brandt at the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> evinces all of the concepts that modernism<br />

proclaimed—Sachlichkeit, functionality, hygiene, and the use of modern<br />

materials and construction methods (Figure 2.2). 3 To all appearances it is<br />

a thoroughly modern object. Surface decoration has been eschewed in<br />

favor of pared-down, machine-like geometrical shapes that form the round<br />

lid, the semicircular handle, and the crossed base. But although it suggests<br />

machine production, it was laboriously hand-wrought in the <strong>Bauhaus</strong><br />

38

2.2<br />

Marianne Brandt,<br />

Tea Infuser and<br />

Strainer, 1924,<br />

silver, Katalog der<br />

Muster, <strong>Bauhaus</strong><br />

GmbH, 1925,<br />

photomechanical<br />

print in black and<br />

orange inks on<br />

white paper (Graphic<br />

design by Herbert<br />

Bayer)<br />

The Irreproducibility of the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> Object<br />

workshop at great cost. This diminutive pot’s handle and knob are ebony,<br />

and it was only available in silver when ordered through the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> GmbH<br />

catalogue. 4 Out of the numerous objects designed at the school, its presence<br />

among the other twelve products selected in 1925–1926 for inclusion<br />

in the product catalogue suggests that it was deemed representative of<br />

the <strong>Bauhaus</strong>. Yet, it could not be inexpensively mass-produced in these<br />

materials, nor was it intended to be; as the catalogue notes, it featured<br />

“exacting handcraftsmanship.” In any case, its smooth form and the meticulous<br />

joins of its body to its spout and base lacked the surface ornamentation<br />

that hid imperfections that occurred in cheaply produced factory goods<br />

of this period, resulting in an object that would have been very difficult to<br />

industrially fabricate with precision. Thus, it could be serially produced by<br />

hand in the metal workshop in limited quantities, but it was not—in form,<br />

material, or price—suitable for mass reproduction. It was, in short, a luxury<br />

object in need of an elite consumer—and not only one who could afford it,<br />

but one who understood both its modern form and its underlying ideas. 5<br />

<strong>Bauhaus</strong> goods were also highly legible expressions of affluence.<br />

39

Robin Schuldenfrei<br />

Though the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> proposed to utilize industry to make goods that even<br />

the masses could afford, it played to a privileged audience—especially<br />

members of the industrial and educated upper middle class (respectively<br />

the Wirtschaftsbürgertum and Bildungsbürgertum). Despite the rise of<br />

German industrialism, accompanied by the ascent of technical firms such<br />

as AEG, Siemens, and numerous smaller rivals, the objects produced by<br />

the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> were not items associated with the machine age, such as<br />

advanced electrical goods. Equally revealing, the school’s products did not<br />

advocate an entirely new way of living, unlike designs of its contemporaries,<br />

such as Grete Lihotzky’s mass-produced Frankfurt Kitchen of 1926 (a<br />

minuscule modern kitchen designed for maximum efficiency which limited<br />

the number of steps needed to perform tasks, following the scientific<br />

principles of Frederick Winslow Taylor) or Hannes Meyer’s Coop-Zimmer (a<br />

radically pared-down single room supplied with standard elements to meet<br />

the absolute minimum needs for dwelling; see Figure 12.4, page 256). Gropius’s<br />

stated aims for the workshops, from about 1923 onwards, reiterated<br />

the <strong>Bauhaus</strong>’s desire to develop “standard types for all practical commodities<br />

of everyday use.” 6 And yet, given this charge, why were there no <strong>Bauhaus</strong><br />

forks, an ordinary product that could be easily molded or stamped out<br />

in large quantities at low cost? Instead the school remained committed to<br />

producing the types of traditional, conventional objects—chess sets, teapots,<br />

tea services, tea containers, ashtrays, and armchairs—that already<br />

had a place in upper-class homes (Figure 2.3).<br />

40<br />

2.3<br />

<strong>Bauhaus</strong> vitrine,<br />

Ausstellung<br />

Europäisches<br />

<strong>Kunst</strong>gewerbe,<br />

1927, Grassi-<br />

Museum, Leipzig

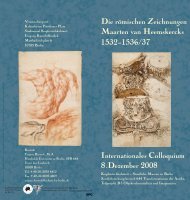

2.4<br />

Above:<br />

Wilhelm Wagenfeld<br />

(designer;<br />

executed by<br />

Josef Knau),<br />

Kugelförmige<br />

Kannen (Sphereshaped<br />

jugs),<br />

1924, silver-plated<br />

brass, German<br />

silver lids and<br />

hinges (Photograph<br />

by Lucia Moholy,<br />

1924, printed<br />

c. 1950)<br />

Below: German<br />

Werkbund<br />

(designer<br />

unknown),<br />

Warenbuch silver<br />

jugs, c. 1915<br />

The Irreproducibility of the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> Object<br />

<strong>Bauhaus</strong> objects employed a stripped-down vocabulary of forms<br />

while reducing applied ornament; the result was an object that was mod-<br />

ern and yet familiar. 7 One can see this process at work in Wilhelm Wagen-<br />

feld’s 1924 <strong>Bauhaus</strong> design for a set of small, sphere-shaped jugs, which<br />

rework some Werkbund Warenbuch-endorsed silver versions available at<br />

least as early as 1915 (Figure 2.4). 8 The earlier jugs featured delicate, reedcovered<br />

handles and a hand-hammered arts and crafts finish; the <strong>Bauhaus</strong><br />

counterparts were simplified and more geometric but had the same general<br />

form and function. Material costs were reduced in the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> versions<br />

by employing silver-plated brass and German silver—which, tellingly,<br />

maintained the appearance of real silver. 9 But older, luxurious materials<br />

such as silver and ebony also remained part of the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> repertoire<br />

throughout the 1920s. A <strong>Bauhaus</strong> egg cooker from 1926 had an ebony<br />

handle, for example. A number of objects, such as Brandt’s teapot (ME 8)<br />

and tea service with water pot (ME 24), were advertised in silver, obviously<br />

a luxury material (Figures 2.2, 2.5). Already expensive because they were<br />

41

Robin Schuldenfrei<br />

handmade, objects in finer materials raised costs significantly, allowing<br />

quality to take precedence over the goods’ accessibility to a broader public.<br />

In other words, the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> did not reinvent products, but simply<br />

introduced known objects in new “modern” forms and occasionally<br />

new materials. It did not wish to alienate its potential consumers with<br />

modernism, but rather to accommodate their perceived needs and already<br />

articulated desires for a certain repertoire of goods, which were then given<br />

a modernist treatment. Under Gropius, even through the late 1920s, the<br />

school introduced very little that was unfamiliar, and relied on established,<br />

traditional luxury objects prevalent in the upper echelons of culture. Rather<br />

than overwhelm its audience with wholly new ideas and goods, the <strong>Bauhaus</strong><br />

created its new market through consensualist means, remaining<br />

committed to designing the types of weighty, representative objects that<br />

the bourgeoisie might be enticed to buy.<br />

In doing so, the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> appealed to what Benjamin described<br />

as the authority of traditional art objects, that is, the authority that they<br />

retained through their relationship to a tradition and in the context of established<br />

social rituals. Traditional <strong>Kunst</strong>gewerbe (decorative arts) objects such<br />

as the tea service with its array of accoutrements (tea infuser, water pot,<br />

creamer, sugar bowl) maintained this autonomous authority through their<br />

role in the customs that guided patterns of life in bourgeois homes. These<br />

social rituals continued to maintain a distance between the object and its<br />

user—the aura, the “unique apparition of a distance, however near it may<br />

42<br />

2.5<br />

Marianne Brandt,<br />

Tea service with<br />

Water pot, 1924,<br />

silver with ebony<br />

handles,<br />

Katalog der Muster,<br />

<strong>Bauhaus</strong> GmbH,<br />

1925,<br />

photomechanical<br />

print in black<br />

and orange inks<br />

on white paper<br />

(Graphic design by<br />

Herbert Bayer)

The Irreproducibility of the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> Object<br />

be”—that sustained traditional authority. 10 Technological reproducibility, on<br />

the other hand, “emancipates the work of art from its parasitic subservi-<br />

ence to ritual.” 11 For the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> to have engaged in successful mass repro-<br />

duction of standard objects of everyday use, it would have been necessary<br />

that objects—rather than shoring up their withering aura through an appeal<br />

to tradition—instead be produced in such a manner that they successfully<br />

reached the masses.<br />

<strong>Bauhaus</strong> goods were also prohibitively expensive. To put their<br />

prices in perspective, it is important to note that the average income for<br />

a working-class (Arbeiter) family in 1927 was about 64 Marks per week<br />

and for a white-collar (Angestellten) family, around 91 Marks per week. 12<br />

Marcel Breuer’s “Wassily” chair, not in leather but merely in fabric, cost<br />

60 Marks, around a week’s worth of wages for a worker. 13 The silver <strong>Bauhaus</strong><br />

cookie tin (Keksdose) cost 160 Marks, the teapot cost 90 Marks, and<br />

the five-piece tea service in German silver cost 180 Marks, three times a<br />

worker’s weekly wage (Figures 2.3, 2.5). As <strong>Bauhaus</strong> artist Otto Rittweger<br />

noted in 1926: “Today it is more difficult than ever for the vast majority<br />

of people who would like to possess such a [<strong>Bauhaus</strong>] service to actually<br />

afford one.” 14 Comparatively, a non-<strong>Bauhaus</strong>, generic nickeled coffee set<br />

cost only 10 Marks. <strong>Bauhaus</strong> objects were not consumed by the masses;<br />

in 1925, even if they could have afforded a <strong>Bauhaus</strong> lamp, 81 percent of the<br />

inhabitants in Berlin’s working-class areas lived without electricity. 15<br />

Indeed, the start-up costs of mass production or the high projected<br />

sale prices often kept goods from ever being produced. On several<br />

occasions, Gropius commented that the costs for producing the objects<br />

were higher than what the market could bear and that the selling price of<br />

<strong>Bauhaus</strong> goods was artificially high in order to meet costs associated with<br />

balancing the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> budget and the purchase of raw materials in small<br />

quantities rather than in bulk. 16 Objects from the metal workshop were<br />

especially unaffordable as both labor and material costs were high, but<br />

goods from the other workshops were also costly, and it was often the<br />

more expensive objects that were promoted. For example, there were two<br />

categories of <strong>Bauhaus</strong> chess sets: the standard version “intended for use”<br />

(Gebrauchsspiel), and the “luxury” version (Luxusspiel), which was made<br />

by hand or in small batches, using rare and costly types of wood. 17 While<br />

the standard wood chess set was priced at 51 Marks, the walnut version<br />

cost 155 Marks. 18 The Luxusspiel was marketed early on through a series<br />

of postcards, two of which featured the word Luxus prominently in the<br />

advertising copy (Figure 2.6).<br />

Gropius had to contend with the accusation that the products<br />

of the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> were simply another form of expensive, artistic luxury<br />

43

Robin Schuldenfrei<br />

similar to the output of other schools of arts and crafts (<strong>Kunst</strong>gewerbe). 19 He<br />

was careful to articulate that the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> was involved in creating artistic<br />

objects within the present economic paradigm, but asserted early on that<br />

its work was not involved in “artistic luxury affairs” (künstlerische Luxusangelegenheit).<br />

20 László Moholy-Nagy, around 1928, conceived of a dia logue<br />

between a “well-meaning critic” of the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> and a “representative of<br />

the <strong>Bauhaus</strong>.” In it, the critic charges that <strong>Bauhaus</strong> objects have become<br />

luxury objects, accessible only to a few. 21 To this, the representative of the<br />

<strong>Bauhaus</strong> replies that during the initial phases the objects were so expensive<br />

that only a few wealthy people were able to buy them, but that the luxury<br />

product itself was merely an intermediate link in the development towards<br />

becoming an object of everyday use. 22 This intriguing line of reasoning—<br />

that the objects were part of an evolution from luxury to accessibility—does<br />

not appear to have gained wider currency. During Gropius’s tenure, a tension<br />

existed between concurrent realities: the production of serial objects<br />

by hand, the ideal of the prototype, and the desire for mass production. By<br />

never fully reaching the mass production stage, because of their cost and<br />

nature, the <strong>Bauhaus</strong>’s products ultimately remained luxury objects.<br />

Following Benjamin’s formulation, the very act of the mass<br />

reproduction and dissemination of <strong>Bauhaus</strong> goods—rather than small, serialized<br />

production of multiple copies made by hand—would have allowed<br />

them to be brought out of the rarified realm of luxury and tradition:<br />

44<br />

2.6<br />

Postcard<br />

advertising Josef<br />

Hartwig’s <strong>Bauhaus</strong><br />

chess set, 1924,<br />

lithograph (Graphic<br />

design by Joost<br />

Schmidt)<br />

It might be stated as a general formula that the technology of<br />

reproduction detaches the reproduced object from the sphere<br />

of tradition. By replicating the work many times over, it substitutes<br />

a mass existence for a unique existence. And in permitting

The Irreproducibility of the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> Object<br />

the reproduction to reach the recipient in his or her own situa-<br />

tion, it actualizes that which is reproduced. 23<br />

The cost and exclusivity of <strong>Bauhaus</strong> objects were related to the fact that<br />

they were turned out in small batches, mainly to fill specific commissions,<br />

in a workshop system. As Benjamin observes,<br />

In principle, the work of art has always been reproducible.<br />

Objects made by humans could always be copied by humans.<br />

Replicas were made by pupils in practicing for their craft, by<br />

masters in disseminating their works, and, finally, by third parties<br />

in pursuit of profit. But the technological reproduction of<br />

artworks is something new. 24<br />

At the <strong>Bauhaus</strong>, the move to technological reproduction would have had<br />

to entail the object’s overcoming of its tradition-grounded formal qualities<br />

so as to be determined instead by its inherent reproducibility; in Benjamin’s<br />

words, “the work reproduced becomes the reproduction of a work<br />

designed for reproducibility.” 25 Thus in terms of the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> project, the<br />

fact that <strong>Bauhaus</strong> objects were visually modern was less important than<br />

the fact that they were never reproduced in any significant numbers.<br />

<strong>Bauhaus</strong> Modern on Display<br />

In addition to the school building in Dessau, which not only housed the school<br />

but showcased its ideas, the nearby houses of the school’s masters were<br />

on view and played a very public role in setting the context for <strong>Bauhaus</strong><br />

objects, eliciting interest in the media and the public alike (Figure 2.7). Like<br />

the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> objects, Gropius’s director’s house and the three double masters’<br />

houses advertise an aesthetic of mass reproducibility but in fact are also<br />

an example of limited serial production. It is not insignificant that their inhabitants<br />

often referred to them as “villas”; they represented a rarified form of<br />

dwelling and were meant to function as lived-in showpieces for the school’s<br />

theories and ideals, allowing the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> to exhibit the products of its workshops<br />

in an instructive and architecturally appropriate domestic setting.<br />

Ise Gropius’s diary charts an unending stream of important visitors<br />

representing an elevated, educated segment of the population—from<br />

trade organizations and cultural groups to politicians, modern architects,<br />

artists, cultural critics, period intellectuals, and professors. 26 Even a year<br />

after they had been completed, there seemed to be no indication that<br />

interest in the houses was waning, as Lyonel Feininger wrote exasperatedly<br />

to his wife in the fall of 1927: “What is going on here is beyond<br />

45

Robin Schuldenfrei<br />

belief and almost beyond endurance. Crowds of idlers slowly amble along<br />

Burgkühnauer Allee, from morning to night, goggling at our houses, not<br />

to speak of trespassing in our gardens to stare in the windows.” 27 According<br />

to Dessau Mayor Fritz Hesse, between 1927 and 1930 the <strong>Bauhaus</strong><br />

buildings received over 20,000 visitors. 28 This indicates that their modern<br />

design and contents were not quickly assimilated into the general culture<br />

but remained objects of fascination.<br />

The director’s house, in particular, functioned as an “exhibition<br />

house,” playing a very public role. As Feininger wrote to his wife, “Gropius’s<br />

house, of course, is miraculous. The furniture and the entire setup<br />

are intended as representative.” 29 The house boasted an appliance-filled<br />

kitchen with labor-saving conveniences, such as an automatic soap-infused<br />

sprayer for the dishes, an early clothes washer, and a centrifuge dryer. But<br />

these devices were for the hired help, an expected domestic arrangement<br />

46<br />

2.7<br />

Above:<br />

Walter Gropius<br />

(Architect),<br />

<strong>Bauhaus</strong> Masters’<br />

Housing, Interior<br />

of Moholy-Nagy<br />

House, Dessau,<br />

1925–1926,<br />

gelatin silver print<br />

(Photograph by<br />

Lucia Moholy,<br />

c. 1925)<br />

Below:<br />

Tea corner in the<br />

Gropius House,<br />

Dessau, 1925–1926,<br />

gelatin silver print<br />

(Photograph by<br />

Lucia Moholy, 1926)

The Irreproducibility of the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> Object<br />

for a couple of their social standing. Period films celebrating the house<br />

depict a uniformed maid at work while Ise Gropius drinks tea with friends in<br />

the living room “tea corner” (Figure 2.7). Serviced by hot and cold running<br />

water and an electric tea kettle, it aptly illustrates the merging of bourgeois<br />

habits and precious objects with modern technology and convenience,<br />

with little pretense towards universal application. The dining room featured<br />

<strong>Bauhaus</strong> furniture made out of costly nickel-plated tubular steel, an adjustable<br />

plate warmer, and other electrical appliances that could be plugged in<br />

directly to the floor outlets conveniently placed in the center of the room,<br />

adjacent to the table. A fan installed in the living room was connected to<br />

the central heating system behind the wall, so that warmed, but fresh, air<br />

could be brought in during the winter. Gropius’s 1930 book <strong>Bauhaus</strong>bauten<br />

Dessau acknowledged that this feature, like many others in the house, was<br />

an extravagance, and predicted that “today a lot still functions as luxury,<br />

that will be the norm the day after tomorrow!” 30 At a time when modern<br />

architects looked to mass production for interior fittings, and when massproduced,<br />

plain porcelain sinks were readily available, Gropius’s bathroom<br />

featured a luxurious richly marble-veined double sink, flanked by glass-lined<br />

walls. The <strong>Bauhaus</strong>bauten book erased the marble veining from the sink to<br />

make it appear more industrial and less luxurious. Perhaps tellingly, Gropius<br />

employed a chauffeur and his house was the only one with a garage.<br />

Generally, the house was not portrayed for what it really was—a prohibitively<br />

expensive design for the powerful director of the <strong>Bauhaus</strong>.<br />

Productive Operations<br />

As early as April 1922 and continuing into 1923, the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> masters and<br />

Gropius had discussed the necessity of organizing the workshops into a<br />

productive operation (Produktiv-Betrieb), and indicated that they viewed<br />

the school itself as a locus of productive operations (Produktiv-Apparat). 31<br />

Gropius envisioned products from <strong>Bauhaus</strong> prototypes, reproduced via<br />

methods of standardization and large-scale sales as the only way that<br />

goods could be offered at a reasonable price. 32 The <strong>Bauhaus</strong>’s embrace of<br />

an industrial means of production was the result of external political and<br />

economic as well as internal pressures. This proposed shift in the activities<br />

and overall orientation of the workshops, clearly articulated by Gropius,<br />

was founded on an astonishingly immodest premise: to sway the industrial<br />

powers of 1920s Germany. 33<br />

Although factory production was the stated desire after 1923,<br />

throughout the entire history of the school, small orders were filled for<br />

specific patrons in response to requests via correspondence and personal<br />

47

Robin Schuldenfrei<br />

visits to the <strong>Bauhaus</strong>. 34 From small objects to furnishings for entire apart-<br />

ments, original pieces were produced, not just in the Weimar period as<br />

might be expected, when original crafts were the mainstay, but throughout<br />

the Dessau period too. 35 Students were expected to spend a specific<br />

number of hours in their chosen workshop with a portion of that time<br />

devoted to formal instruction and the acquisition of technical skills, but<br />

orders for <strong>Bauhaus</strong> goods also had to be filled. A general lack of production<br />

capacity in the workshops due to labor, financial, and materials shortages,<br />

meant that orders were constantly delayed or only partially supplied.<br />

In 1924 the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> manager Emil Lange wrote Gropius a long<br />

letter containing recommendations for making the workshops economically<br />

sound. 36 Lange does not suggest reviewing the overall design process,<br />

the internal production costs, or whether the products were appealing to<br />

potential buyers; to the contrary, he expresses frustration with the caprice<br />

of buyers and the unpredictability in their ordering patterns, apparently<br />

showing little acumen about the market and tools of selling. This lack of<br />

attunement to consumer desire was a continual problem. But more importantly,<br />

the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> continued to be oriented toward workshop production<br />

rather than to what successful mass reproduction would have had to entail.<br />

During 1924 and 1925 the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> took important measures to<br />

shore up its finances and implemented some basic operations to organize<br />

its fairly autonomous workshops into a more comprehensive entity for the<br />

purposes of selling designs. The first mention of a “<strong>Bauhaus</strong>-AG” appears<br />

in conjunction with the possible uses of profits from the school’s 1923<br />

exhibition. 37 In January 1924, Gropius began lengthy proceedings with the<br />

government over the founding of a separate <strong>Bauhaus</strong> company, the <strong>Bauhaus</strong><br />

GmbH. 38 In a long meeting on 18 February 1924 Gropius laid out plans<br />

for an economically feasible <strong>Bauhaus</strong> corporation, discussing its relationship<br />

to the workshops, provisions for student employment, and payment—<br />

either by piecework or wages. 39 At this stage, the general plan was not to<br />

outsource production to other companies, but rather to internally organize<br />

the labor and productivity of the workshops according to what Gropius<br />

called the “free market” (freie Wirtschaft). An agreement template was<br />

drawn up that gave the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> GmbH the rights to all objects made at<br />

the school and stipulated that the designer was not to make similar objects<br />

on his own. 40 In return, the company would pay for every approved design<br />

and give the designer up to 30 percent of the resulting profits. 41 The company<br />

hired a business manager, Walter Haas, to act as a conduit between<br />

the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> and industry, to market the prototypes designed in the workshops,<br />

and to oversee the reproduction of objects. The <strong>Bauhaus</strong> printed up<br />

stationery and invoices for the GmbH, which was legally a separate entity.<br />

48

The Irreproducibility of the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> Object<br />

Under the aegis of the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> GmbH, the school began to<br />

organize its products into one comprehensive sales catalogue, known as<br />

the Katalog der Muster. 42 There are two versions. A single sheet, probably<br />

designed by Moholy-Nagy, appeared with just four selected products,<br />

perhaps those viewed as most marketable. A multi-page, orange<br />

and black version, designed by Herbert Bayer with photographs by Lucia<br />

Moholy, appeared in November of 1925 (Figures 2.2, 2.5). This catalogue<br />

was a loose-leaf booklet, organized by workshop, in which each product<br />

or product group could be removed and function as a stand-alone information<br />

sheet. A separate price list, which could be periodically updated,<br />

possibly accompanied it. The objects could be ordered individually from<br />

the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> GmbH, although the hope was for mass production through<br />

the company itself.<br />

Presented as single objects on individual leaflets, the products<br />

in the Katalog der Muster are not offered as part of a comprehensive <strong>Bauhaus</strong><br />

collection, in that the objects are organized by workshop rather than<br />

by use or intended room. The images project the clean, clutter-free ideal of<br />

modernism, but the design also reflects the straightforwardness of standard<br />

product catalogues of the period. There is a careful estrangement of<br />

the objects from their surroundings. The images, through their coldness<br />

and detachment, highlight the alluring, surface qualities of the individual<br />

objects rather than their potential for use.<br />

Whereas in an earlier period the workshops had been guided<br />

by an ideal of working in tandem to create an integrated interior—as took<br />

place in the 1920 Sommerfeld House or the Haus am Horn exhibition<br />

house in 1923—the Katalog der Muster represents a shift to the pursuit of<br />

the single object, or type-object, for wider production. As Gropius stated<br />

unequivocally, the workshops’ mandate was to create standard types for<br />

practical commodities. Yet the objects selected for the catalogue represent<br />

some of the school’s most elite objects and arguably many of its least<br />

practical ones—a full silver tea service, the tea container and tea balls, the<br />

chess set, and several ashtrays which, among other objects, would not<br />

have been easily stamped out or otherwise mass-produced by machine.<br />

Furthermore, several designs note “most exacting” (genaueste) or “finest<br />

handcraftsmanship” (feinste Handarbeit), calling into question whether<br />

some of the objects in the catalogue were ever intended for mass production.<br />

The “Inventory of Work and Ownership Rights of the Workshops,”<br />

made prior to the move to Dessau, serves as a good indication of what<br />

the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> had produced by April of 1925, and lists the objects that it<br />

theoretically could have selected from when assembling the Katalog der<br />

Muster. 43 Simpler, arguably more easily mass-producible objects on the<br />

49

Robin Schuldenfrei<br />

list, such as tablecloths, pillows, scarves, or drapes being produced in the<br />

weaving workshop, are notably absent from the catalogue.<br />

Another method by which the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> sought to draw German<br />

industrialists to its goods was through participation in trade shows,<br />

especially the twice-yearly Leipzig Trade Fair, at which the school exhibited<br />

objects regularly from 1924 to 1931, selling goods and taking orders to be<br />

filled by the workshops. 44 As with the Katalog der Muster, the Leipzig activities<br />

underscore the ambiguity of the <strong>Bauhaus</strong>’s program: the products<br />

represented elite, one-off goods to be sold for profit as well as prototypes<br />

intended for mass production. In 1927, four years after Gropius’s turn to<br />

industry, the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> was selected to represent Germany at the Ausstellung<br />

Europäisches <strong>Kunst</strong>gewerbe (European Applied Arts Exhibition), held<br />

in conjunction with the regular Leipzig fair (Figure 2.3). Chosen not as a producer<br />

of modern, rational goods intended for industry but rather for their<br />

fine craftsmanship, the handmade, luxurious nature of the goods comes to<br />

the fore. <strong>Bauhaus</strong> objects, including a hammered, silver-lined fish poaching<br />

dish, were put on display in the same room as Meissen porcelain and<br />

other expensive goods made in Germany. This conjunction illustrates the<br />

<strong>Bauhaus</strong>’s difficult position of trying to be modern while existing within the<br />

context of <strong>Kunst</strong>gewerbe, the applied arts, with the skilled training in the<br />

traditional crafts that it required. The workshops continued to occupy an<br />

unclear position between their role as producers of the unique art object<br />

and as designers of prototypes for mass reproduction.<br />

Although industrial production and the formation of an alliance<br />

between the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> and industry was a carefully articulated goal, even<br />

an underlying principle, which Gropius reiterated in speeches and writings<br />

and which is implied in the “industrial” aesthetics of the objects, there is<br />

little evidence beyond the Katalog der Muster and trade fair exhibitions<br />

that clear steps toward the formalization of relations with industry were<br />

taken. 45 As years passed, the situation began to appear dire, as Moholy-<br />

Nagy admitted in 1928: “Designs for vessels and appliances, with which<br />

we have been occupied for years, have so far not been sold to industry.” 46<br />

Outside visitors, such as art theorist Rudolf Arnheim, similarly noted: “Certainly<br />

the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> has not yet come so far as to be able to supply industry<br />

with conclusively standard patterns.” 47 A contract finally materialized<br />

in 1927 with the metalworks factory Paul Stotz AG of Stuttgart to manufacture<br />

and distribute the glass lamp, although it was not fulfilled. 48 Later,<br />

relations with the manufacturers Körting & Mathiesen and Schwintzer &<br />

Gräff brought lighting to the market in significant numbers for the first<br />

time in the <strong>Bauhaus</strong>’s history. 49 In the end, only four workshops were ever<br />

able to deliver models to industry—carpentry, weaving, metal, and wall<br />

50

The Irreproducibility of the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> Object<br />

painting—and Gropius’s ideal of working closely with manufacturers never<br />

materialized. 50 Only three firms began negotiations during his tenure; the<br />

rest came during that of his successors, mainly Hannes Meyer.<br />

Practically speaking, <strong>Bauhaus</strong> objects were not mass-produced<br />

in any number, nor picked up by industry in general. It is important to differentiate<br />

between objects that were genuinely mass-reproducible and the<br />

visual propagation of an idea of modern, reproducible products. This idea of<br />

paring objects down to their essences appealed to students and masters<br />

at the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> as a visual and conceptual task—though outside the school<br />

the objects met with limited success. <strong>Bauhaus</strong> objects did not transform<br />

function but rather attempted to distill the object’s essential function, as in<br />

the visually pared-down tea extraction pot which was refined until it poured<br />

well (Figure 2.2). Yet, designed to make a very strong cup of tea, its contents<br />

needed to be diluted with hot water from yet another vessel—resulting<br />

in the proliferation, rather than reduction, of household objects. What<br />

remained important to the <strong>Bauhaus</strong>, if not the consuming public, was the<br />

aesthetic of simple, machine-like forms, the elevation of function, and the<br />

idea of mass reproduction.<br />

Buyers, in any case, were skeptical. Even though Gropius<br />

stressed that the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> workshops were addressing the “necessities of<br />

life of the majority of people” and viewed the home and its furnishings as<br />

“mass consumer goods,” and though the school wanted to limit designs<br />

to “characteristic, primary forms and colors, readily accessible to everyone,”<br />

the masses themselves did not embrace the modern goods. 51 Convincing<br />

them to value a teapot’s severe reduction in form and decoration<br />

for its attendant <strong>Bauhaus</strong> ideology was arguably as much of a hindrance<br />

as its price tag. These objects were not received with wide enthusiasm<br />

outside an elite of left-wing artistic and intellectual circles, the members<br />

of which understood the principles of the school and its objects, or what<br />

was sometimes termed the “Intellektuell-Sachliches”—even among those<br />

who could afford them. 52 A list of workshop commissions completed in<br />

1926 notes mainly avant-garde art galleries as patrons. 53 Photographs<br />

of industrialists’ interiors, for example, reveal homes amply laden with<br />

modern paintings and sculpture yet virtually no modern design objects.<br />

Surprisingly, modern interiors, such as those by Marcel Breuer, do not<br />

feature <strong>Bauhaus</strong> objects on their tables or shelves with any frequency<br />

either. 54 It is very difficult, outside of its own buildings and photographs, to<br />

find the products of the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> in domestic settings. As Grete Lihotzky,<br />

in her important 1927 essay “Rationalization in the Household,” ends her<br />

devastating critique: “Years of effort on the part of the German Werkbund<br />

and individual architects, countless articles and lectures demanding clarity,<br />

51

Robin Schuldenfrei<br />

simplicity, and efficiency in furnishings, as well as a turn away from the<br />

traditional kitsch of the last fifty years, have had almost no effect whatsoever.”<br />

55 Other sources, too, indicate that <strong>Bauhaus</strong> objects were estranged<br />

from public taste; according to a critic for the Frankfurter Zeitung the <strong>Bauhaus</strong><br />

was “even further from the general taste of the public than the Werkbund.”<br />

56 The legacy of the <strong>Bauhaus</strong>’s products lies more with an idea and<br />

a few canonical objects than with any widespread material reality or mass<br />

adoption of modern objects.<br />

Production/Reproduction<br />

How then should these issues of production figure in the assessment of<br />

the <strong>Bauhaus</strong>’s significance? Should the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> be viewed as an entity<br />

that failed to produce objects that buyers wanted to consume or that manufacturers<br />

wanted to produce? Should <strong>Bauhaus</strong> objects be understood as<br />

unique, authentic works of art—which may be their historical fate, judging<br />

by their scarcity and their status in art museums today? Walter Benjamin’s<br />

postulation that “what withers in the age of the technological reproducibility<br />

of the work of art is the latter’s aura” is useful for reflecting on the<br />

status of these objects within the conditions of production of their time. 57<br />

The status of art and art objects, including objects intended for use, in<br />

such an age was precisely the question that Gropius faced at the <strong>Bauhaus</strong>.<br />

As proclaimed by his slogan “art and technology—a new unity,” his<br />

emphasis was on both art and technology, and specifically their relation<br />

to each other.<br />

The nineteenth-century heritage of <strong>Kunst</strong>gewerbe and its post-<br />

World War I revival shaped the school’s earliest incarnation, which explicitly<br />

attempted to recover that heritage via the high-quality art object of the<br />

craftsman. This heritage continued to shape subsequent activities at the<br />

school, although Gropius carefully sought to elude what he termed “dilettantism<br />

of the handicrafts” (kunstgewerblichen Dilettantismus). 58 Simultaneously<br />

he worked to counter the “ersatz” and low-quality products of an<br />

industrializing Germany. The potential for degradation of <strong>Bauhaus</strong> designs<br />

through the reproduction process was of continual concern to Gropius,<br />

who offered the reassurance that a decline in the quality of the product’s<br />

material and construction, as a result of mechanical reproduction, would be<br />

countered by all available means. 59 Gropius thus sought to mass-produce<br />

well-designed objects by industrial methods without ever wholly freeing<br />

the school from the <strong>Kunst</strong>gewerbe legacy of the design of the singular<br />

work of art produced in small numbers. According to Benjamin’s theory,<br />

given the reality of small batches in the workshops, these objects would<br />

52

The Irreproducibility of the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> Object<br />

have safeguarded their own, autonomous authority, grounded in tradition,<br />

and resisted being taken up and appropriated by the masses. However, a<br />

loss of aura and authority would necessarily have resulted if the <strong>Bauhaus</strong><br />

had succeeded in factory mass reproduction.<br />

These issues of production and reproduction of art, architecture,<br />

and objects were a subject of period concern among theorists and critics,<br />

such as Benjamin and the architectural critic Adolf Behne, artists such as<br />

Moholy-Nagy, and architects such as Gropius. 60 Each had different, specific<br />

ideas, but the terms and the overarching concern—the relationship of<br />

the authentic art object to the modern means of production—formed an<br />

important commonality of period discourse. In his 1917 essay, “The Reproductive<br />

Age” (Das reproduktive Zeitalter), Behne argued that, unlike with<br />

earlier authentic artworks, technological reproduction caused the essential<br />

effect—Wirkung—of the original to be lost, and yet the aesthetic values<br />

of the work of art were transferred to the reproductive process itself. 61<br />

Moholy-Nagy’s 1922 essay “Production-Reproduction” went further, specifying<br />

the goal of making reproductive processes useful for creative activities.<br />

62 Benjamin identified the loss of authenticity and aura and the turn to<br />

mass reproduction as inevitable consequences of the modern transformation<br />

in conditions of production, which nonetheless bore great artistic and<br />

political potential, while Moholy-Nagy, and the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> generally, actively<br />

endorsed mass reproduction as an art practice.<br />

Perhaps the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> should be assessed in terms not of production,<br />

but of reproduction—the stage at which it failed most visibly to<br />

realize its aims. 63 As Gropius shifted the emphasis of the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> towards<br />

mass reproduction, along with other basic operations he instituted, he<br />

was reacting not to a change in the availability of industrial technology, but<br />

rather to a change in ideas about process. In an attempt to broaden consumption,<br />

the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> needed to move from concentrating on production<br />

(where it arguably did well, generating many functionally and aesthetically<br />

successful designs in a relatively short period of time) to reproduction. As<br />

this examination has shown, reproduction, as both a practical process and<br />

a theoretical construct, is precisely where a material and economic failure<br />

took place; at the same time, theoretical signification can be read from this<br />

historical episode.<br />

In evaluating the <strong>Bauhaus</strong>, it is the emphasis laid on the process<br />

of reproduction that is important and imbued with social significance in<br />

the context of the period. As K. Michael Hays has pointed out, Benjamin’s<br />

analysis reveals that as one approaches those mediums that are inherently<br />

multiple and reproducible, not only does the authenticity of the object,<br />

its here and now, lose its value as a repository of meaning, but also the<br />

53

Robin Schuldenfrei<br />

reproductive technique as procedure takes on the features of a system of<br />

signification. Meaning arises from the multiple forces of social practice<br />

rather than the formal qualities of the auratic art object. 64 Thus the potential<br />

significance of the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> project under Gropius lies less in the objects<br />

themselves that were produced than in the <strong>Bauhaus</strong>’s grappling with the<br />

problem of reproducibility. The members of the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> saw their larger<br />

project not just as art practice but as a part of social practice, as Moholy-<br />

Nagy wrote: “We hope that from the inspirations of the <strong>Bauhaus</strong>, such<br />

results will come forth as will be useful to a new social order.” 65 This social<br />

function, for Benjamin and for the <strong>Bauhaus</strong>, occurred when the art object<br />

was reproduced in such a way that what it would lose in aura it would make<br />

up for by reaching society at large, becoming available for its use. For Benjamin,<br />

the social function of art was revolutionized as soon as the criterion<br />

of authenticity ceased to be applicable to artistic production. 66<br />

The actual objects designed by the <strong>Bauhaus</strong>, however, were not<br />

consonant with what was needed to achieve its goals for reproduction,<br />

as their elite qualities stymied the social project. In their relationship to<br />

society, the object-types the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> produced—such as silver tea services—were<br />

insufficient; their luxury character limited their reproducibility,<br />

perhaps equally as much as their costly fabrication and materials. As a<br />

result of this disjunction, <strong>Bauhaus</strong> objects can be read as material indices<br />

of the social problematic of mass reproducibility.<br />

Benjamin pinpoints the transformation that occurs in the modern<br />

age from the autonomous authority of the art object itself to its social<br />

determination by its inherent technological reproducibility. That Gropius’s<br />

<strong>Bauhaus</strong> embraced mass reproduction as a system and a goal is meaningful<br />

even if it was unable to realize this goal to any significant, material<br />

degree. As Josef Albers noted, “The greatest success of the <strong>Bauhaus</strong><br />

was to win over and interest industry. We realized this aim only to a small<br />

degree.” 67 Indeed, the idea of a relationship with industry remained the<br />

<strong>Bauhaus</strong>’s greatest achievement, even if it was hardly realized. The <strong>Bauhaus</strong><br />

inserted itself into this system of signification through the ideal of<br />

reproduction, and it was willing to sacrifice the auratic or authentic qualities<br />

of its objects to do so. An essential legacy of <strong>Bauhaus</strong> objects is the<br />

mythical aspiration of good design for the masses, achieved through an<br />

alignment with industrial production. And meaning can be derived from<br />

this ideal even if it never occurred at the level of actual <strong>Bauhaus</strong> products.<br />

Through their very failure as objects of reproduction and mass consumption,<br />

the products of the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> paradoxically retained both their<br />

authenticity and their aura, for, in an age of mechanical reproduction—that<br />

is, of the definitive withering of aura—an individual <strong>Bauhaus</strong> object, such<br />

54

The Irreproducibility of the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> Object<br />

as a Brandt teapot, remains a work of art. To acknowledge this by con-<br />

ceding these objects’ elite, luxury status, however, calls into question the<br />

received, mythological account of the <strong>Bauhaus</strong>’s contribution to the trajectory<br />

of modernism. It also re-poses the question of what designing objects<br />

for mass reproduction—and socially transformative use by society, by the<br />

masses—might entail.<br />

Acknowledgments<br />

This essay has benefited from thoughtful suggestions by John Ackerman, Annie Bourneuf, Charles<br />

W. Haxthausen, Jennifer Hock, and Klaus Weber, whom I would like to thank. I also thank Peter<br />

Nisbet and Laura Muir at the Busch-Reisinger Museum, Harvard University, and Sabine Hartmann<br />

at the <strong>Bauhaus</strong>-Archiv, Berlin.<br />

Notes<br />

1 For related discussion of these concerns, see especially Frederic J. Schwartz, “Utopia for<br />

Sale: The <strong>Bauhaus</strong> and Weimar Germany’s Consumer Culture,” in <strong>Bauhaus</strong> Culture: From<br />

Weimar to the Cold War, ed. Kathleen James-Chakraborty (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota<br />

Press, 2006), 115–38; and Anna Rowland, “Business Management at the Weimar<br />

<strong>Bauhaus</strong>,” Journal of Design History 1, no. 3–4 (1988), 153–75.<br />

2 Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility,” in Walter<br />

Benjamin: Selected Writings, ed. Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings, vol. 3, 1935–1938<br />

(Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, Belknap Press, 2002), 101–36. Benjamin composed<br />

this essay in the autumn of 1935; the version used here is the 1936 second version<br />

which the editors note represents the form in which Benjamin originally wished to see the<br />

work published. A third, revised version remained unfinished at Benjamin’s death and was<br />

published posthumously. See also Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological<br />

Reproducibility, and Other Writings on Media, ed. Michael W. Jennings, Brigid Doherty, and<br />

Thomas Y. Levin (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, Belknap Press, 2008).<br />

When Benjamin makes his famous proclamation, “What withers in the age of the technological<br />

reproducibility of the work of art is the latter’s aura,” he immediately follows it<br />

with: “This process is symptomatic; its significance extends far beyond the realm of art”<br />

(emphasis added, 104). He begins his essay, in a similar vein, with Marx, noting that it<br />

“has taken more than half a century for the change in the conditions of production to be<br />

manifested in all areas of culture” (emphasis added, 101). In the essay, Benjamin largely discusses<br />

this process as it manifests itself in images and film. However it is clear throughout<br />

that the significance of the phenomena he explicates is not limited to these areas of culture<br />

alone; Benjamin also specifically addresses architecture, literature, medicine, music, and<br />

coins. Moreover, Benjamin uses a number of different terms to refer to his subject, not only<br />

“artwork” (<strong>Kunst</strong>werk), but also object of art (Gegenstand der <strong>Kunst</strong>), object (Objekt), thing<br />

(Sache), all of which have been predominantly translated as “artwork,” perhaps contributing<br />

to a common perception that Benjamin is only talking about the visual arts.<br />

The distinct importance of architecture at a late stage in Benjamin’s discussion—which<br />

brings it into particular proximity with film and makes “the laws of its reception … the most<br />

instructive” in relation to new forms of mass participation in art—lies in the fact that buildings<br />

are received in a twofold manner: by perception and by use (120). The significance of<br />

55

Robin Schuldenfrei<br />

Benjamin’s essay for understanding the problem of the reproducibility of <strong>Bauhaus</strong> objects<br />

will hang precisely on the potential for technologically reproducible objects to make themselves<br />

available for mass use.<br />

On production and reproduction in architecture and art, see Beatriz Colomina, ed., Architectureproduction<br />

(New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1988), especially K. Michael<br />

Hays, “Reproduction and Negation: The Cognitive Project of the Avant-Garde,” 153–79;<br />

Charles W. Haxthausen, “Reproduction/Repetition: Walter Benjamin/Carl Einstein,” October<br />

107, no. 47 (winter, 2004): 47–74; Esther Leslie, “Walter Benjamin: Traces of Craft,” Journal<br />

of Design History 11, no. 1 (1998): 5–13; and Andrew Benjamin, ed., Walter Benjamin and<br />

Art (London: Continuum, 2005). For contacts between Walter Benjamin and Moholy-Nagy<br />

during the latter’s years at the <strong>Bauhaus</strong>—and Moholy-Nagy’s influence upon Benjamin—see<br />

“Walter Benjamin and the Avant-Garde,” in Frederic J. Schwartz, Blind Spots: Critical Theory<br />

and the History of Art in Twentieth-Century Germany (New Haven: Yale University Press,<br />

2005), especially pp. 42–50.<br />

In other writings Benjamin devotes sustained attention to domestic objects as part of<br />

the same constellation of themes also found in the “Work of Art” essay. See, for example,<br />

“Louis-Philippe, or the Interior,” section 4, “Paris, Capital of the Nineteenth Century,” in Walter<br />

Benjamin: Selected Writings, ed. Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings, vol. 3, 38–9,<br />

and June 8 entry in “May–June 1931,” in Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings, ed. Michael<br />

W. Jennings, Howard Eiland, and Gary Smith, vol. 2, 1927–1934 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard<br />

University Press, Belknap Press, 1999), 479–80.<br />

3 Sachlichkeit presents difficulties in translation; it could be translated as “factualness” or<br />

“objectiveness.” As Rosemarie Bletter has pointed out, the term simultaneously suggests<br />

the “world of real objects” and that of “conceptual rationalism.” See Bletter, introduction to<br />

Adolf Behne, The Modern Functional Building (Santa Monica: The Getty Research <strong>Institut</strong>e<br />

for the History of Art and the Humanities, 1996), 48.<br />

4 A nearly identical version, MT 49, was available from the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> in brass or red brass<br />

with a silver-plated interior and a silver strainer, but it was not among the chosen objects<br />

featured in the Katalog der Muster. Klaus Weber, curator at the <strong>Bauhaus</strong>-Archiv/Museum <strong>für</strong><br />

Gestaltung, notes that there are presently only seven known period examples of this teapot.<br />

Correspondence with author, 9 March 2009.<br />

5 This was also the case for the other objects featured in the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> catalogue, as well as<br />

for the overwhelming majority of the products of the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> in this period.<br />

6 Walter Gropius, “<strong>Bauhaus</strong> Produktion,” Qualität 4, no. 7–8 (Juli/August 1925): 130. Translation<br />

from a nearly identical version of the essay in Hans Maria Wingler, The <strong>Bauhaus</strong>:<br />

Weimar, Dessau, Berlin, Chicago, ed. Joseph Stein, trans. Wolfgang Jabs and Basil Gilbert<br />

(Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1976), 110. Gropius continued to recall this purpose long after<br />

leaving: “The creation of standard types for the articles of daily use was their main concern.<br />

These workshops were essentially laboratories in which the models for such products were<br />

carefully evolved and constantly improved.” Walter Gropius, “Education Toward Creative<br />

Design,” American Architect and Architecture (May 1937): 28.<br />

7 For invaluable research on the entire span of production in the <strong>Bauhaus</strong>’s metal workshops<br />

and their main artisans, see Klaus Weber, ed., Die Metallwerkstatt am <strong>Bauhaus</strong> (Berlin:<br />

Kupfergraben Verlagsgesellschaft, 1992).<br />

8 The 1915 Werkbund Book of Wares (Warenbuch) was a selection of domestic German goods<br />

that met the Werkbund’s design standards. See Heide Rezepa-Zabel, Deutsches Warenbuch<br />

Reprint und Dokumentation: Gediegenes Gerät <strong>für</strong>s Haus (Berlin: Dietrich Reimer, 2005).<br />

9 German silver, or Neusilber, as it was called in German, had the appearance of silver but was<br />

a surrogate made of an alloy of copper, zinc, and nickel.<br />

10 Benjamin, “Work of Art,” 104–6.<br />

56

11 Benjamin, “Work of Art,” 106.<br />

The Irreproducibility of the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> Object<br />

12 Die Lebenshaltung von 2,000 Arbeiter-, Angestellten-, und Beamten-Haushaltungen: Erhe-<br />

bungen von Wirtschaftsrechnungen im Deutschen Reich von Jahre 1927–1928, Einzelschrif-<br />

ten zur Statistik des deutschen Reichs, no. 22 (Berlin: R. Hobbing, 1932). Specific industries<br />

paid significantly less; for example, a male spinner in the textile industry earned 44 Marks<br />

per week in 1927, while a female spinner earned 28 Marks per week and unskilled workers<br />

earned even less. Statistischen Reichsamt, Statistisches Jahrbuch <strong>für</strong> das Deutsche<br />

Reich (Berlin: Verlag von Reimar Hobbing, 1930). For the day-to-day struggle on this wage,<br />

see Deutscher Textilarbeiterverband, ed., Mein Arbeitstag, Mein Wochenende. 150 Berichte<br />

von Textilarbeiterinnen (Berlin: Textilpraxis Verlag, 1930), 187–9; and “Die Misere des ‘neuen<br />

Mittelstands’,” Die Weltbühne 24, no. 4 (22 January 1929): 130–4.<br />

13 Standard-möbel catalogue, 1927, n.p., <strong>Bauhaus</strong>-Archiv, Berlin.<br />

14 Otto Rittweger, Vivos Voco 5, no. 8–9 (1926): 293–4; translated in Posthumous Works<br />

Designed While Living: Metallwerkstatt <strong>Bauhaus</strong> 20’s/90’s, ed. Bruno Pedretti (Milan: Electa,<br />

1995), 34–5.<br />

15 Die Grundstücks- und Wohnungsaufnahme sowie die Volks-, Berufs- und Betriebszahlung in<br />

Berlin im Jahre 1925 (Berlin, 1928), table 8; quoted in Nicholas Bullock, “First the Kitchen:<br />

Then the Façade,” Journal of Design History 1, no. 3–4 (1988): 188.<br />

16 For example, see Dr Necker and Walter Gropius, “Bericht über die wirtschaftlichen Aussichten<br />

des <strong>Bauhaus</strong>es,” 19 October 1924, typed manuscript, pp. 1–2, <strong>Bauhaus</strong>-Archiv, Berlin.<br />

17 Anne Bobzin and Klaus Weber, Das <strong>Bauhaus</strong>-Schachspiel von Josef Hartwig (Berlin: <strong>Bauhaus</strong>-Archiv,<br />

2006), 17–21.<br />

18 Ausstellung “Die Form,” 1924, exhibition checklist with prices, <strong>Bauhaus</strong>-Archiv, Berlin.<br />

19 For example, the Czech architect and critic Karel Teige chastised the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> early on for<br />

its emphasis on the crafts: “Today, the crafts are nothing but a luxury, supported by the<br />

bourgeoisie with their individualism and snobbery and their purely decorative point of view.”<br />

Karel Teige, Stavba (1924); translated in <strong>Bauhaus</strong>, 1919–1928, ed. Herbert Bayer, Walter Gropius,<br />

and Ise Gropius (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1938; reprint, Boston: Charles T.<br />

Branford Co., 1952), 91.<br />

20 Walter Gropius, Weimar, to Staatsminister Greil, 11 November 1922, p. 2, <strong>Bauhaus</strong>-Archiv,<br />

Berlin. Unless otherwise noted, translations are the author’s own.<br />

21 László Moholy-Nagy (presumed), “Dialogue between a Well-meaning Critic and a Representative<br />

of the <strong>Bauhaus</strong>, Weimar-Dessau,” c. 1928; translated in Krisztina Passuth, Moholy-<br />

Nagy (London: Thames and Hudson, 1985), 400. The identity of the author of this document<br />

has not been conclusively established; the document is in the possession of Moholy-Nagy’s<br />

daughter, Hattula Moholy-Nagy and presumed to be written by Moholy-Nagy.<br />

22 Ibid., 401.<br />

23 Benjamin, “Work of Art,” 104.<br />

24 Ibid., 102.<br />

25 Ibid., 106.<br />

26 Ise Gropius, Diary, <strong>Bauhaus</strong>-Archiv, Berlin.<br />

27 Lyonel Feininger, Dessau, to Julia Feininger, 2 October 1927, Houghton Library, Harvard University,<br />

Cambridge; translated in Lyonel Feininger, Lyonel Feininger, ed. June L. Ness (New<br />

York: Praeger, 1974), 158.<br />

28 Fritz Hesse, Von der Residenz zur <strong>Bauhaus</strong>stadt (Hannover: Schmorl & von Seefeld, 1963), 238.<br />

29 Lyonel Feininger, Dessau, to Julia Feininger, 6 August 1926, Houghton Library; translated in<br />

Feininger, Feininger, 152.<br />

30 Walter Gropius, <strong>Bauhaus</strong>bauten Dessau (München: A. Langen, 1930), 112.<br />

31 Protokoll, Sitzung der Meister und Werkstättenleiter des Staatlichen <strong>Bauhaus</strong>es, 7 April<br />

1922, Weimar, <strong>Bauhaus</strong>-Archiv, Berlin; Protokoll des <strong>Bauhaus</strong>rates, 22 October 1923, in Die<br />

57

Robin Schuldenfrei<br />

Meisterratsprotokolle des Staatlichen <strong>Bauhaus</strong>es Weimar 1919 bis 1925, ed. Volker Wahl<br />

(Weimar: Verlag Hermann Böhlaus Nachfolger, 2001), 319. “Produktiv-Betrieb” can also be<br />

translated as “productive company,” but it is not clear from the original context if a company<br />

is specifically meant at this early date.<br />

32 Gropius, “<strong>Bauhaus</strong> Produktion,” 135; translated in Wingler, <strong>Bauhaus</strong>, 110.<br />

33 Walter Gropius, “Education Toward Creative Design,” American Architect and Architecture<br />

150 (May 1937): 28. Although this was written years later, it succinctly captures the direction<br />

of this period: “The aim of this training was to produce designers who were able, by their<br />

intimate knowledge of material and working processes to influence the industrial production<br />

of our time.”<br />

34 Word of mouth and personal recommendation between customers accounted for much of<br />

this small-scale work, such as a request for a silver tea caddy from Herr Architekt Bernard in<br />

December of 1924 and an order from Herr Regierungsrat Döpel in January 1925 for a silver<br />

pin “like the one the metal workshop had made for the kindergarten teachers.” Rowland,<br />

“Business Management,” 154.<br />

35 The archives of the Stiftung <strong>Bauhaus</strong> Dessau hold original records, including letters, bills<br />

of sale, and drawings of commissions. Notable Dessau commissions include Erich Dieckmann’s<br />

work for Hinnerk and Lou Scheper in 1925, which included chairs, stools, tables,<br />

desks, cupboards, and bookshelves; Dieckmann’s designs for the home of Pauline Schwickert;<br />

and Breuer’s furniture and kitchen cabinetry for the Wohnung Ludwig Grote at the<br />

Palais Reina in Dessau of 1927. For a full range of rare photographs of interiors, see Christian<br />

Wolsdorff, <strong>Bauhaus</strong>-Möbel: eine Legende wird besichtigt/<strong>Bauhaus</strong> Furniture: A Legend<br />

Reviewed (Berlin: <strong>Bauhaus</strong>-Archiv, 2002).<br />

36 Emil Lange to Gropius, Weimar, 16 February 1924, typescript, <strong>Bauhaus</strong>-Archiv, Berlin.<br />

37 Protokoll, Formenmeister-Besprechung, 18 October 1923, in Wahl, Meisterratsprotokolle,<br />

319. Originally the minutes were written with “GmbH,” which was then struck out and<br />

replaced with “AG,” possibly indicating some question of what designation the company<br />

should have. AG, for Aktiengesellschaft, is a public limited company, while GmbH, or Gesellschaft<br />

mit beschränkter Haftung, represents a limited liability company.<br />

38 Wahl, Meisterratsprotokolle, 520–1.<br />

39 Protokoll der Sitzung des <strong>Bauhaus</strong>rates, 18 February 1924, 20 February 1924, in Wahl, Meisterratsprotokolle,<br />

323–4. The meeting lasted 3½ hours.<br />

40 Vertrag zwischen dem <strong>Bauhaus</strong> und <strong>Bauhaus</strong>angehörigen, n.d., typescript, p. 1 verso, <strong>Bauhaus</strong>-Archiv,<br />

Berlin. Several designers, when they left the <strong>Bauhaus</strong>, continued to fill orders<br />

for their designs personally, notably Josef Hartwig, who continued to produce his famous<br />

chess set. This document was designed to prevent this in the future.<br />

41 Protokoll der Sitzung des <strong>Bauhaus</strong>rates, 18 February 1924, 20 February 1924, Thüringisches<br />

Hauptstaatsarchiv Weimar. The “Work Plan of the Metal Workshop” (c. 1925–1926) also<br />

codifies payment, noting that either a single-payment compensation or royalties will be paid<br />

for models used in series production. Translated in Wingler, <strong>Bauhaus</strong>, 111.<br />

42 This small catalogue lacks a formal name in the literature, and even the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> Archive has<br />

not reached a consensus on what to call it. In the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> exhibition and accompanying catalogue,<br />

Das A und O des <strong>Bauhaus</strong>es: <strong>Bauhaus</strong>werbung: Schriftbilder, Drucksachen, Ausstellungsdesign,<br />

Ute Brüning refers to it as the “Katalog der Muster,” while Klaus Weber in Die<br />

Metallwerkstatt am <strong>Bauhaus</strong> refers to it as the “Musterkatalog der <strong>Bauhaus</strong>produkte.” In the<br />

period, the journal <strong>Bauhaus</strong> referred to a page from it as a “prospectus page” (Prospektseite) of<br />

the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> GmbH. <strong>Bauhaus</strong>, no. 1 (1926): 6. Because the title page of the loose-leaf sheets<br />

that make up the catalogue states, “Katalog der Muster,” that title will be used here. In English<br />

it has been translated as “Catalog of Designs” (Schwartz, “Utopia for Sale,” 124) and “<strong>Bauhaus</strong><br />

Sample Catalog” (collection accession file, Harvard Art Museum/Busch-Reisinger Museum).<br />

58

43 Reproduced in Wingler, <strong>Bauhaus</strong>, 98–101.<br />

The Irreproducibility of the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> Object<br />

44 For more on the role of trade shows in the display and sale of <strong>Bauhaus</strong> objects in the Weimar<br />

period, as well as efforts by the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> to bring early goods to market, see Rowland, “Busi-<br />

ness Management,” especially pp. 163–7.<br />

45 The basic plan of the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> to produce machine prototypes rather than the standard fare<br />

of a regular school of applied art was also reported in countless newspaper articles. For a<br />

typical example, see Dr Grote, “Das Weimarer <strong>Bauhaus</strong> und seine Aufgaben in Dessau,”<br />

Anhaltische Rundschau, 11 March 1925: 1.<br />

46 László Moholy-Nagy, “Eine bedeutsame Aussprache: Konferenz der Vertreter des <strong>Bauhaus</strong>es<br />

Dessau und des Edelmetallgewerbes am 9. März 1928 in Leipzig,” Deutsche Goldschmiede-Zeitung,<br />

no. 13 (1928): 123.<br />

47 Rudolf Arnheim, “Das <strong>Bauhaus</strong> in Dessau,” Die Weltbühne 23, no. 22 (31 May 1927): 921;<br />

translated in The Weimar Republic Sourcebook, ed. Anton Kaes, Martin Jay, and Edward<br />

Dimendberg (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), 451.<br />

48 <strong>Bauhaus</strong>, no. 4 (1927): 5. It was also reported that a related catalogue was in production.<br />

However, this relationship appears to have been short-lived, as the lamp division folded,<br />

causing the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> to begin anew in the search for a manufacturer. See Ise Gropius, Diary,<br />

30 November 1927, 205–6.<br />

49 A new contract for lighting came through in February of 1928, as noted in Ise Gropius’s diary<br />

(10 February 1928, 224). In the July 1928 issue, <strong>Bauhaus</strong> announced that both lighting companies<br />

Körting & Mathiesen and Schwintzer & Gräff were producing <strong>Bauhaus</strong> designs. See<br />

“Industrie und <strong>Bauhaus</strong>,” <strong>Bauhaus</strong>, no. 2–3 (1928): 33. For a full account of the <strong>Bauhaus</strong>’s<br />

relationship with Körting & Mathiesen and the line of modern lighting produced by the company<br />

from <strong>Bauhaus</strong> prototypes, see Justus Binroth et al., <strong>Bauhaus</strong>leuchten? Kandemlicht!<br />

Die Zusammenarbeit des <strong>Bauhaus</strong>es mit der Leipziger Firma Kandem/<strong>Bauhaus</strong> Lighting?<br />

Kandem Light! The Collaboration of the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> with the Leipzig Company Kandem (Leipzig:<br />

Grassi Museum, Museum <strong>für</strong> <strong>Kunst</strong>handwerk Leipzig; Stuttgart: Arnoldsche Art Publishers,<br />

2002). This arrangement, while fulfilling Gropius’s aims for the school, did so in an<br />

anonymous manner, because except for one mention in 1931, Körting & Mathiesen did not<br />

acknowledge the association of its Kandem line with the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> until its 75th anniversary,<br />

in 1964; see Ulrich Krüger, “Leutzsch Lighting: On the Collaboration of Körting & Mathiesen<br />

AG in Leipzig-Leutzsch with the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> in Dessau,” in Binroth, <strong>Bauhaus</strong>leuchten?, 11.<br />

50 Christian Wolsdorff, “<strong>Bauhaus</strong>-Produkte: Zusammenarbeit mit der Industrie,” in <strong>Bauhaus</strong><br />

Berlin: Auflösung Dessau 1932, Schließung Berlin 1933, Bauhäusler und Drittes Reich, ed.<br />

Peter Hahn (Weingarten: <strong>Kunst</strong>verlag Weingarten, 1985), 183. The pottery workshop also<br />

began to make contacts with—and supply models to—industry (porcelain and stoneware)<br />

but did not accompany the <strong>Bauhaus</strong> to Dessau, and ceased to exist.<br />

51 Gropius, “<strong>Bauhaus</strong> Produktion,” 130; translated in Wingler, <strong>Bauhaus</strong>, 110.<br />

52 Like Sachlichkeit, “Intellektuell-Sachliches” presents difficulties in translation; it could be<br />

translated as “intellectual factualness” or “intellectual objectiveness.”<br />

53 <strong>Bauhaus</strong>, no. 1 (1926): 3.<br />

54 Among the hundreds of photographs of Berlin interiors, both known and anonymous dwellings,<br />

at the Bildarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz in Berlin, there are relatively few modern<br />

interiors, and in these interiors, <strong>Bauhaus</strong> domestic objects are in scant evidence, while<br />

Breuer’s tubular steel chairs and <strong>Bauhaus</strong> furniture are fairly common. For example, the<br />

Breuer-designed apartment interior for Edwin Piscator, 1927, featured <strong>Bauhaus</strong> furniture and<br />

lighting fixtures but not its other products.<br />

55 Grete Lihotzky, “Rationalisierung im Haushalt,” Das neue Frankfurt, no. 5 (1926–1927): 120;<br />

translated in Kaes, Jay, and Dimendberg, Weimar Republic Sourcebook, 463.<br />

56 Fritz Wichert, “Ein Haus, das Sehnsucht weckt,” Frankfurter Zeitung, 10 October 1923.<br />

59

Robin Schuldenfrei<br />

57 Benjamin, “Work of Art,” 104.<br />

58 Gropius, “<strong>Bauhaus</strong> Produktion,” 135–6; translated in Wingler, <strong>Bauhaus</strong>, 110.<br />

59 Ibid., 136.<br />

60 Benjamin was a member of artistic and architectural circles in Berlin and was certainly<br />

conversant with key concepts of the day. He was part of a group that met often at Hans<br />

Richter’s house, which included Raoul Hausmann, Tristan Tzara, Frederich Kiesler, and Hans<br />

(Jean) Arp, which would launch the magazine G in 1923, led by Richter, Lissitzky, Van Doesburg,<br />

and Mies.<br />

61 Arnd Bohm, “Artful Reproduction: Benjamin’s Appropriation of Adolf Behne’s ‘Das reproduktive<br />

Zeitalter’ in the <strong>Kunst</strong>werk-Essay,” The Germanic Review 68, no. 4 (1993): 149. Cf. Adolf<br />

Behne, “Das reproduktive Zeitalter,” Marsyas (1917): 219–25.<br />

62 Moholy-Nagy, “Production-Reproduction,” De Stijl, no. 7 (1922): 97–101; translated in Passuth,<br />

Moholy-Nagy, 289.<br />

63 The slippage in this essay between the terms “mass production” and (mass) “reproduction”<br />

reflects this problem: to speak of mass production is really to speak of mass reproduction—<br />

as Benjamin’s essay illuminates—but the standard usage of the former term highlights the<br />

tendency to conceive it in the terms of production alone.<br />

64 Hays, “Reproduction and Negation,” 163. Emphasis original.<br />

65 Moholy-Nagy, “Dialogue”; translated in Passuth, Moholy-Nagy, 400.<br />

66 Benjamin, “Work of Art,” 106.<br />

67 Josef Albers, “Thirteen years at the <strong>Bauhaus</strong>,” in <strong>Bauhaus</strong> and <strong>Bauhaus</strong> People, ed. Eckhard<br />

Neumann (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1970), 171.<br />

60