Onondaga Lake Watershed Progress Assessment and Action ...

Onondaga Lake Watershed Progress Assessment and Action ...

Onondaga Lake Watershed Progress Assessment and Action ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

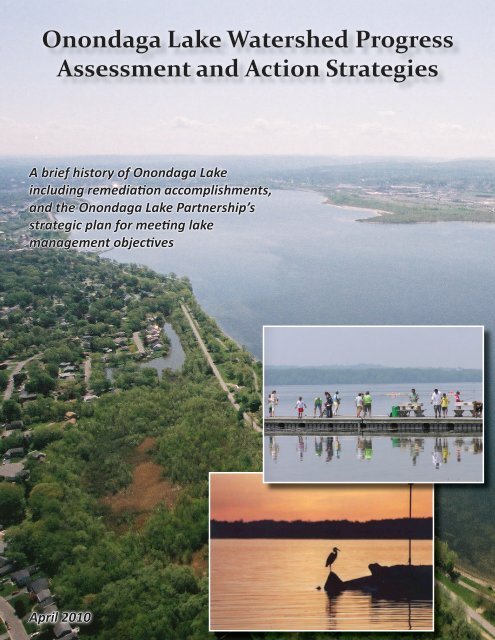

<strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong> <strong>Progress</strong><br />

<strong>Assessment</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Action</strong> Strategies<br />

A brief history of <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong><br />

including remediation accomplishments,<br />

<strong>and</strong> the <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> Partnership’s<br />

strategic plan for meeting lake<br />

management objectives<br />

April 2010

<strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong> <strong>Progress</strong><br />

<strong>Assessment</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Action</strong> Strategies<br />

Produced by:<br />

April 2010<br />

Central New York Regional Planning & Development Board<br />

126 North Salina Street, Suite 200<br />

Syracuse, NY 13202<br />

With support from the <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> Partnership<br />

Members:<br />

Ms. Jo-Ellen Darcy - Assistant Secretary of the Army (Civil Works)<br />

Ms. Judith Enck - Regional Administrator, EPA Region II<br />

Mr. David Patterson - Governor, State of New York<br />

Mr. Andrew Cuomo - Attorney General, State of New York<br />

Ms. Joanne Mahoney - County Executive, <strong>Onondaga</strong> County<br />

Ms. Stephanie Miner - Mayor, City of Syracuse<br />

Representatives:<br />

LTC Daniel B. Snead - District Comm<strong>and</strong>er, U.S. Army Engineer District, Buffalo<br />

Mr. Seth Ausubel - Chief, Freshwater Protection Branch, U.S. EPA Region II<br />

Mr. Kenneth Lynch - Regional Director, NYSDEC Region 7<br />

Mr. Charles Silver - Environmental Scientist, NYS Attorney General’s Office<br />

Mr. David Coburn - Director, <strong>Onondaga</strong> County Office of the Environment<br />

Mr. Andrew M. Maxwell - Director of Planning <strong>and</strong> Sustainability, City of Syracuse<br />

Ex Officio:<br />

Senator Charles Schumer<br />

Senator Kirsten Gillibr<strong>and</strong><br />

Representative Daniel Maffei<br />

Funding for this report was provided by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Buffalo District in<br />

cooperation with the OLP.<br />

Cover photo sources: background - U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, top inset - <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> Partnership, bottom inset - Patti<br />

Rusczyk, <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> Partnership 2004 photo contest (2nd place, adult flora <strong>and</strong> fauna category)

Statement of Purpose<br />

The <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> Partnership (OLP) was formed to promote cooperation among government agencies<br />

<strong>and</strong> other parties involved in managing the environmental issues related to the rehabilitation of <strong>Onondaga</strong><br />

<strong>Lake</strong>. The OLP is comprised of Federal, State, <strong>and</strong> local governments <strong>and</strong> not-for-profit representatives<br />

with a vested interest in the rehabilitation of <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong>. The six principal members of the OLP<br />

include:<br />

••<br />

••<br />

••<br />

••<br />

••<br />

••<br />

United States Army Corps of Engineers<br />

United States Environmental Protection Agency<br />

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation<br />

Office of the New York State Attorney General<br />

<strong>Onondaga</strong> County<br />

City of Syracuse<br />

The <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong> <strong>Progress</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Action</strong> Strategies (OLWPAAS) report summarizes<br />

the history, degradation, <strong>and</strong> recovery of <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong>. The report provides an assessment<br />

of the OLP’s progress toward achieving the objectives outlined in the 1993 “<strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong>: A Plan for<br />

<strong>Action</strong>”, also known as the <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> Management Plan (OLMP). The report recommends specific<br />

action strategies <strong>and</strong> identifies remaining actions to be taken by the OLP to complete the rehabilitation<br />

of <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> in accordance with the OLMP. These recommendations were developed based on the<br />

OLMP progress assessment, <strong>and</strong> with consideration of new information <strong>and</strong> technologies available since<br />

the writing of the OLMP. Where possible <strong>and</strong> appropriate, potentially responsible parties are identified for<br />

completing planned restoration activities in the lake <strong>and</strong> its watershed. The action strategies are organized<br />

in eight Strategic Areas that address different aspects of lake rehabilitation. More information on the identification<br />

<strong>and</strong> intended purpose of the action strategies can be found in the introduction to Chapter 3.<br />

In addition to the OLP, there are many agencies, organizations, schools, <strong>and</strong> individuals that are taking an<br />

active role in the recovery of <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong>. While this document does not attempt to provide an account<br />

of all of these efforts, the OLP acknowledges that such initiatives also play an important role in the rehabilitation<br />

of the lake.<br />

This report was reviewed by the individual members of the <strong>Onondaga</strong><br />

<strong>Lake</strong> Partnership (OLP) <strong>and</strong> approved for release to the public for<br />

purposes of providing general overview information. Approval for<br />

release does not signify adoption or approval for purposes of regulatory,<br />

enforcement or other legal actions, of the factual, scientific or other<br />

assertions, characterizations or conclusions contained herein.

Table of Contents<br />

List of Acronyms.............................................................................................................................................ii<br />

Chapter 1: Background.........................................................................................................1<br />

Historical Perspective.......................................................................................................................................2<br />

Water Management Problems...........................................................................................................................2<br />

<strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> Management Conference.......................................................................................................4<br />

<strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> Partnership.............................................................................................................................4<br />

Restoration Efforts............................................................................................................................................7<br />

A Historical Perspective: Timeline...................................................................................................................8<br />

Chapter 2: <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> Management Plan Status Report....................................... 11<br />

Introduction....................................................................................................................................................12<br />

Strategic Areas 1&2: Municipal Sewer Discharge <strong>and</strong> Combined Sewer Overflows....................................12<br />

Strategic Areas 3&4: Industrial Pollution (National Priorities List Site <strong>and</strong> Other Adjacent Areas of Concern)................................................................................................................................................................17<br />

Strategic Area 5: Hydrogeologic Investigations.............................................................................................26<br />

Strategic Area 6: Fish <strong>and</strong> Wildlife Habitat <strong>and</strong> Fisheries Management........................................................29<br />

Strategic Area 7: Inner Harbor <strong>and</strong> Shoreline Use.........................................................................................34<br />

Strategic Area 8: Non-Point Source Pollution................................................................................................37<br />

Chapter 3: <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong> <strong>Action</strong> Strategies...............................................43<br />

Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................44<br />

Strategic Area 1: Municipal Sewer Discharge................................................................................................44<br />

Strategic Area 2: Combined Sewer Overflows ..............................................................................................48<br />

Strategic Areas 3&4: Industrial Pollution (National Priorities List Site <strong>and</strong> Other Adjacent Areas of Concern)................................................................................................................................................................52<br />

Strategic Area 5: Hydrogeologic Investigations. ..........................................................................................59<br />

Strategic Area 6: Fish <strong>and</strong> Wildlife Habitat <strong>and</strong> Fisheries Management........................................................62<br />

Strategic Area 7: Inner Harbor <strong>and</strong> Shoreline................................................................................................72<br />

Strategic Area 8: Non-Point Source Pollution................................................................................................77<br />

Appendices...........................................................................................................................85<br />

Appendix A. Key project sites <strong>and</strong> locations in the <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> area.....................................................86<br />

Appendix B. Preliminary budget needs to accomplish action strategies <strong>and</strong> recommendations...................87<br />

Appendix C. Glossary.....................................................................................................................................93<br />

Appendix D. Literature cited..........................................................................................................................97<br />

Appendix E. Status of Amended Consent Judgment projects......................................................................100<br />

<strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong> <strong>Progress</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Action</strong> Strategies<br />

i

List of Acronyms<br />

ACJ<br />

AEM<br />

AMP<br />

ASLF<br />

BERA<br />

BMP<br />

BTEX<br />

CCE<br />

CSO<br />

EBP<br />

EPA<br />

FCF<br />

FDA<br />

FS<br />

GIS<br />

GM<br />

HHRA<br />

HSPF<br />

IFG<br />

IRM<br />

LCP<br />

LDC<br />

MDA<br />

METRO<br />

MGP<br />

Mg/L<br />

MS4<br />

NDZ<br />

NPL<br />

NPS<br />

NRCS<br />

NYS<br />

NYSCC<br />

Amended Consent Judgment<br />

Agricultural Environmental Management<br />

Ambient Monitoring Program<br />

Atlantic States Legal Foundation<br />

Baseline Environmental Risk <strong>Assessment</strong><br />

Best Management Practice<br />

Benzene, Toluene, Ethylbenzene <strong>and</strong> Xylene<br />

Cornell Cooperative Extension<br />

Combined Sewer Overflow<br />

Environmental Benefit Project<br />

Environmental Protection Agency (US)<br />

Floatables Control Facility<br />

Food <strong>and</strong> Drug Administration<br />

Feasibility Study<br />

Geographic Information Systems<br />

General Motors<br />

Human Health Risk <strong>Assessment</strong><br />

Hydrologic Simulation Program (Fortran)<br />

Inl<strong>and</strong> Fisher Guide<br />

Interim Remedial Measures<br />

Linden Chemicals <strong>and</strong> Plastics<br />

<strong>Lake</strong>front Development Corporation<br />

Mudboil Depression Area<br />

<strong>Onondaga</strong> County Metropolitan Syracuse<br />

Wastewater Treatment Plant<br />

Manufactured Gas Plant<br />

Milligrams per Liter<br />

Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System<br />

No Discharge Zone<br />

National Priority List<br />

Non-Point Source<br />

Natural Resources Conservation Service<br />

New York State<br />

New York State Canal Corporation<br />

NYSDEC New York State Department of Environmental<br />

Conservation<br />

NYSDOH New York State Department of Health<br />

NYSOAG New York State Office of the Attorney<br />

General<br />

OCDOT<br />

<strong>Onondaga</strong> County Department of<br />

Transportation<br />

OCDWEP <strong>Onondaga</strong> County Department of Water<br />

Environment Protection<br />

OCCRP<br />

<strong>Onondaga</strong> Creek Conceptual Revitalization<br />

Plan<br />

OCSWCD <strong>Onondaga</strong> County Soil <strong>and</strong> Water Conservation<br />

District<br />

OEI<br />

OLCC<br />

OLMC<br />

OLMP<br />

OLP<br />

OLWQM<br />

OM&M<br />

PAH<br />

PCB<br />

PDI<br />

PPM<br />

PRP<br />

RFP<br />

RI<br />

RI/FS<br />

ROD<br />

RTF<br />

SCA<br />

SPDES<br />

<strong>Onondaga</strong> Environmental Institute<br />

<strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> Cleanup Corporation<br />

<strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> Management Conference<br />

<strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> Management Plan<br />

<strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> Partnership<br />

<strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> Water Quality Model<br />

Operation, Maintenance <strong>and</strong> Monitoring<br />

Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon<br />

Polychlorinated Biphenyl<br />

Pre-Design Investigation<br />

Parts Per Million<br />

Potentially Responsible Party<br />

Request for Proposals<br />

Remedial Investigation<br />

Remedial Investigation/ Feasibility Study<br />

Record of Decision<br />

Regional Treatment Facility<br />

Sediment Consolidation Area<br />

State Pollutant Discharge Elimination System<br />

SUNY-ESF State University of New York College of<br />

Environmental Science <strong>and</strong> Forestry<br />

SWAMP<br />

SWWM<br />

TMDL<br />

TRWQM<br />

UFI<br />

USACE<br />

USDA<br />

USGS<br />

VOCs<br />

Surface Water Ambient Monitoring Program<br />

Surface Water <strong>Watershed</strong> Model<br />

Total Maximum Daily Load<br />

Three Rivers Water Quality Model<br />

Upstate Freshwater Institute<br />

United States Army Corps of Engineers<br />

United State Department of Agriculture<br />

United States Geological Survey<br />

Volatile Organic Compounds<br />

ii<br />

<strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong> <strong>Progress</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Action</strong> Strategies

Chapter 1: Background<br />

Figure 1-1. Aerial view of <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong>. (Source: OLP)<br />

Chapter 1: <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong> <strong>Progress</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Action</strong> Strategies Page 1

Historical Perspective<br />

Approximately 285 square miles in area, the<br />

<strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong> (Figure 1‐2) lies almost<br />

entirely within <strong>Onondaga</strong> County. <strong>Onondaga</strong><br />

<strong>Lake</strong>, located along the northern end of the city<br />

of Syracuse, is approximately one mile wide <strong>and</strong><br />

4.6 miles long <strong>and</strong> covers an area of 4.6 square<br />

miles. The lake has an average depth of 35 feet<br />

<strong>and</strong> a maximum depth of 63 feet (<strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong><br />

Cleanup Corporation (OLCC) 2001).<br />

Before the American Revolution, the area<br />

surrounding <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> was the center of<br />

the Iroquois Confederacy 1 . European immigrants<br />

settled the area throughout the 17 th <strong>and</strong> 18 th<br />

Centuries due in part to the presence of salty<br />

springs around <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong>. After the Erie<br />

Canal was built in the early 1800s, the booming<br />

salt industry in <strong>and</strong> around the city of Syracuse<br />

attracted many people (OLMC 1993).<br />

In the 19th Century, <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> served as a<br />

popular tourist attraction. The lake was populated<br />

with beaches, resorts <strong>and</strong> amusement parks.<br />

While there has been some debate over the variety<br />

of aquatic species found within the lake, there<br />

is documentation stating the lake supported a<br />

healthy fishery including Atlantic salmon <strong>and</strong> lake<br />

sturgeon. <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> whitefish, known as<br />

ciscoes, were served in restaurants from Syracuse<br />

to New York City (Engineering World 2007). The<br />

fishing <strong>and</strong> resort industry began to decline in<br />

the early 20 th century as the lake’s western shore<br />

became more industrialized. Over time, increased<br />

industrial development, a rising population <strong>and</strong><br />

associated increases in sewage <strong>and</strong> industrial<br />

discharges took their toll on the water quality of<br />

1. The Iroquois Confederacy, also known as the Haudenosaunee<br />

Confederacy, is a union of six Nations (the<br />

Cayuga, Mohawk, Oneida, <strong>Onondaga</strong>, Seneca, <strong>and</strong> Tuscarora)<br />

that have inhabited upstate New York since before<br />

the arrival of Europeans. The Confederacy is traditionally<br />

believed to have been formed on the shores of <strong>Onondaga</strong><br />

<strong>Lake</strong>.<br />

<strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong>. By 1940, swimming in the lake<br />

was banned, <strong>and</strong> in 1970, fishing was banned in<br />

the lake (OLCC 2001).<br />

Water Management Problems<br />

The water quality in <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> has been<br />

impacted by a host of pollutants from a variety of<br />

sources. Ammonia <strong>and</strong> phosphorus from <strong>Onondaga</strong><br />

County’s Metropolitan Syracuse Wastewater<br />

Treatment Plant (METRO) contributed to aquatic<br />

species decline, poor water clarity <strong>and</strong> oxygen<br />

depletion. Industrial activities along the lake’s<br />

shoreline resulted in the release of numerous contaminants<br />

to local surface water <strong>and</strong> ground water<br />

including mercury, chlorinated benzenes, ammonia<br />

<strong>and</strong> human-made mineral salts. Hydrogeologic<br />

features, such as the Tully Valley mudboils 2 , <strong>and</strong><br />

l<strong>and</strong>slides have contributed significant amounts<br />

of sediment to <strong>Onondaga</strong> Creek, impacting water<br />

clarity <strong>and</strong> aquatic habitat in the creek <strong>and</strong> in the<br />

lake.<br />

The establishment of the <strong>Onondaga</strong> County Metropolitan<br />

Sewer District in the 1950s marked the<br />

start of efforts to address declining water quality.<br />

METRO was built in 1960. The County made<br />

improvements to METRO in 1979, upgrading to<br />

secondary treatment <strong>and</strong> then to tertiary treatment<br />

in 1981 (OLMC 1993).<br />

In 1988, Atlantic States Legal Foundation (ASLF),<br />

a Syracuse-based organization providing legal <strong>and</strong><br />

technical assistance to citizens <strong>and</strong> organizations<br />

dealing with environmental problems, filed a lawsuit<br />

against <strong>Onondaga</strong> County. ASLF alleged that<br />

METRO <strong>and</strong> combined sewer overflow (CSO) discharges<br />

(see page 5) were violating federal water<br />

pollution st<strong>and</strong>ards established under the Clean<br />

Water Act of 1972. The State of New York joined<br />

as a plaintiff, alleging that <strong>Onondaga</strong> County<br />

2. A mudboil is an artesian-pressured geologic feature<br />

that discharges both ground water <strong>and</strong> fine-grained<br />

sediment at the l<strong>and</strong> surface <strong>and</strong> can cause l<strong>and</strong>-surface<br />

subsidence over time.<br />

Page 2<br />

Chapter 1: <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong> <strong>Progress</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Action</strong> Strategies

also violated the New York State Environmental<br />

Conservation Law. The parties settled the litigation<br />

in 1989 through the METRO consent judgment,<br />

requiring the County to complete planning, design<br />

<strong>and</strong> construction of facilities to bring wastewater<br />

discharges from the METRO plant into compliance<br />

with regulatory requirements (OLMC 1993).<br />

In 1997, the METRO consent judgement was<br />

replaced when the State of New York, ASLF <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Onondaga</strong> County reached<br />

an agreement on wastewater<br />

treatment plant <strong>and</strong> collection<br />

system improvements <strong>and</strong><br />

a schedule for attaining<br />

compliance with the Clean<br />

Water Act by 2012. This<br />

agreement is known as the<br />

Amended Consent Judgment<br />

(ACJ).<br />

consent decree obligating Honeywell to clean<br />

up hazardous waste in the sediments of the <strong>Lake</strong><br />

(<strong>Lake</strong> Bottom cleanup) consistent with the remedy<br />

selected by the New York State Department of<br />

Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) <strong>and</strong> the<br />

United States Environmental Protection Agency<br />

(EPA) in a Record of Decision (ROD). The claims<br />

for the cleanup of Geddes Brook/Ninemile Creek<br />

<strong>and</strong> natural resource damages remain outst<strong>and</strong>ing<br />

but are moving toward resolution.<br />

In 1989, the State of<br />

New York filed a lawsuit<br />

against Allied-Signal, Inc.<br />

(Honeywell International,<br />

Inc. is the corporate successor<br />

of Allied-Signal) seeking to<br />

compel the company to clean<br />

up the hazardous substances<br />

that it <strong>and</strong> its predecessor<br />

companies had discharged<br />

into <strong>and</strong> in the environs of<br />

<strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong>, <strong>and</strong> to pay<br />

damages for the destruction<br />

of natural resources. In 1992,<br />

the federal court approved a<br />

consent order requiring the<br />

company to conduct, subject<br />

to State supervision <strong>and</strong><br />

approval, a comprehensive<br />

environmental study of the<br />

area <strong>and</strong> to evaluate the<br />

feasibility of various remedial<br />

alternatives (RI/FS).<br />

On January 4, 2007, the<br />

federal court approved a<br />

Figure 1-2. The <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong>. (Source: Central New York Regional<br />

Planning & Development Board)<br />

Chapter 1: <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong> <strong>Progress</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Action</strong> Strategies Page 3

• The Attorney General of the State of New<br />

York (NYSOAG)<br />

• <strong>Onondaga</strong> County Executive<br />

• Mayor of the city of Syracuse, New York<br />

In December 1993, the OLMC released <strong>Onondaga</strong><br />

<strong>Lake</strong>, A Plan For <strong>Action</strong>, which became known as<br />

the <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> Management Plan (OLMP).<br />

This document details major pollution problems<br />

affecting the lake <strong>and</strong> makes recommendations for<br />

resolving those issues.<br />

The OLMC approved the ACJ in 1998 <strong>and</strong><br />

resolved that the ACJ superseded the OLMP with<br />

regard to sewage treatment <strong>and</strong> discharge <strong>and</strong><br />

CSOs. 3<br />

<strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> Partnership<br />

Figure 1-3. Cover of the <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> Plan for <strong>Action</strong>,<br />

published in December 1993. (Source: OLP)<br />

<strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> Management<br />

Conference<br />

In 1990 the <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> Management Conference<br />

(OLMC) was established by an Act of<br />

Congress under the Great <strong>Lake</strong>s Critical Programs<br />

Act. The OLMC was charged with developing <strong>and</strong><br />

coordinating the implementation of “a comprehensive<br />

restoration, conservation, <strong>and</strong> management<br />

plan for <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong>” (OLMC 1993). The<br />

OLMC consisted of six voting members:<br />

• Assistant Secretary of the Army for Civil<br />

Works (USACE)<br />

• Administrator of the U.S. Environmental<br />

Protection Agency (EPA)<br />

• Governor of the State of New York (represented<br />

by New York State Department of<br />

Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC))<br />

In 1999, the <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> Partnership (OLP)<br />

was established by an Act of Congress under<br />

the Water Resource Development Act. Although<br />

the OLP replaced the OLMC, its membership is<br />

comprised of the same six key members that made<br />

up the OLMC. Under leadership of the USACE,<br />

the OLP works with various other local, state,<br />

<strong>and</strong> regional member organizations including the<br />

following:<br />

• Natural Resources Conservation Service<br />

• US Geological Survey<br />

• New York State Department of Housing<br />

<strong>and</strong> Urban Development<br />

• New York State Canal Corporation<br />

• Central New York Regional Planning <strong>and</strong><br />

Development Board<br />

• <strong>Onondaga</strong> County Soil <strong>and</strong> Water<br />

Conservation District<br />

• Metropolitan Development Association<br />

• <strong>Lake</strong>front Development Corporation<br />

3. On April 29, 1998 the OLMC approved the ACJ with<br />

OLMC Resolution #98-2. In September 1999, the OLMC<br />

passed Resolution #99-1, endorsing the ACJ <strong>and</strong> ceremonially<br />

appending the 1993 OLMP.<br />

Page 4<br />

Chapter 1: <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong> <strong>Progress</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Action</strong> Strategies

• Cornell Cooperative Extension of<br />

<strong>Onondaga</strong> County<br />

• State University of New York College of<br />

Environmental Science <strong>and</strong> Forestry<br />

• Atlantic States Legal Foundation<br />

• <strong>Onondaga</strong> Historical Association<br />

• League of Women Voters<br />

• Izaak Walton League<br />

The mission of the OLP is to facilitate <strong>and</strong> coordinate<br />

the development <strong>and</strong> implementation of lake<br />

<strong>and</strong> watershed improvement projects to restore<br />

<strong>and</strong> conserve water quality, natural resources <strong>and</strong><br />

recreational uses to the benefit of the public. The<br />

actions <strong>and</strong> efforts of the OLP are to be consistent<br />

with the <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> Management Plan <strong>and</strong><br />

the Amended Consent Judgment.<br />

Using the 1993 <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong>, A Plan for <strong>Action</strong><br />

as its foundation, the OLP identified eight strategic<br />

planning areas to focus the restoration efforts. The<br />

following summarizes each of those strategic areas<br />

<strong>and</strong> major concerns:<br />

1.<br />

Municipal Sewer Discharge<br />

METRO is an advanced wastewater treatment<br />

facility serving the city of Syracuse <strong>and</strong> several<br />

surrounding municipalities. Treated domestic<br />

<strong>and</strong> industrial wastes discharge from a pipe at<br />

METRO directly into the lake, contributing up<br />

to 20% of the total annual inflow to <strong>Onondaga</strong><br />

Figure 1-4. Combined Sewer Overflow.<br />

(Source: <strong>Onondaga</strong> County)<br />

2.<br />

3.<br />

<strong>Lake</strong>. METRO has been one of the most<br />

significant contributors of nutrient pollution to<br />

<strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong>, historically contributing up to<br />

approximately 60% of the annual phosphorus<br />

load <strong>and</strong> over 90% of the ammonia load to the<br />

lake (OLMC 1993).<br />

Combined Sewer Overflows<br />

In Syracuse, like many older cities, the sewer<br />

systems were built to jointly convey sewage<br />

<strong>and</strong> stormwater. Wastewater entering METRO<br />

is disinfected, killing bacteria <strong>and</strong> viruses.<br />

During periods of heavy precipitation <strong>and</strong><br />

increased runoff, excess flow from combined<br />

sewers is diverted from METRO <strong>and</strong><br />

discharged without treatment into tributaries of<br />

<strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> through flow-relief structures<br />

called combined sewer overflows (CSOs).<br />

When the OLMP was released in 1993, there<br />

were over 60 CSOs discharging into <strong>Onondaga</strong><br />

<strong>Lake</strong> tributaries (OLMC 1993).<br />

Industrial: National Priorities List (NPL) Site<br />

<strong>and</strong> Sub-sites<br />

Since the late 1800s, areas near <strong>Onondaga</strong><br />

<strong>Lake</strong> have been the location for widespread<br />

industrial <strong>and</strong> chemical manufacturing<br />

activities. A number of entities, including<br />

Allied-Signal, Inc., General Motors <strong>and</strong><br />

the Salina Town L<strong>and</strong>fill, are responsible<br />

for significant pollution of the lake <strong>and</strong><br />

surrounding area. From 1882 until 1986,<br />

Allied-Signal <strong>and</strong> its predecessors discharged<br />

wastes containing mercury, salt wastes,<br />

ammonia, benzene <strong>and</strong> chlorinated benzenes<br />

into the lake.<br />

General Motors discharged industrial<br />

pollutants, including PCBs from a partsmanufacturing<br />

facility located along Ley<br />

Creek. Some industrial wastes were disposed<br />

in the Salina Town L<strong>and</strong>fill (Lizlovs 2005).<br />

There are currently eight sub-sites identified<br />

on the EPA National Priorities List associated<br />

with the industrial contamination of <strong>Onondaga</strong><br />

<strong>Lake</strong>. Investigation <strong>and</strong>/or cleanup of these<br />

Chapter 1: <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong> <strong>Progress</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Action</strong> Strategies Page 5

4.<br />

eight sub-sites is being performed under legal<br />

agreement with the NYSDEC.<br />

Industrial: Non-NPL Sites<br />

While the most significant industrial<br />

contamination is associated with NPL sites<br />

described above, several other industrial<br />

contamination sites not currently associated<br />

with the Superfund sites are being addressed<br />

by the NYSDEC. These sites vary from former<br />

coal gasification facilities to industrial waste<br />

disposal areas located within the watershed.<br />

5.<br />

Hydrogeologic Investigations<br />

The southern part of the <strong>Onondaga</strong> Creek<br />

Valley, known as the Tully Valley, is the home<br />

of unique hydrogeologic features known as<br />

mudboils. Mudboils are geologic features<br />

that discharge fresh to salty water <strong>and</strong> finegrained<br />

sediment. The mudboils are thought<br />

to be natural geologic features, but increased<br />

mudboil activity starting in the 1950s has been<br />

attributed to Allied Signal’s former solutionmining<br />

activities in the southern part of the<br />

Tully Valley (OLCC 2001).<br />

In the 1990s, much of the <strong>Onondaga</strong> Creek<br />

streambed downstream of the mudboils, was<br />

covered with mudboil-derived sediments as<br />

the mudboils contributed approximately 30<br />

tons of sediment per day to the creek (OLCC<br />

2001). Other sources of sediment to the creek<br />

include l<strong>and</strong>slides in the Tully Valley area<br />

<strong>and</strong> streambank <strong>and</strong> roadbank erosion during<br />

storms <strong>and</strong> other runoff events.<br />

6.<br />

Habitat <strong>and</strong> Fisheries<br />

Figure 1-5. Geology of <strong>Onondaga</strong> County, showing the<br />

location of Tully Valley. (Source: USGS)<br />

As a result of the extensive pollution to the<br />

lake, fish populations significantly declined<br />

in the 20 th century. High phosphorus levels<br />

promoted algae blooms, which resulted in<br />

reduced oxygen levels. These conditions<br />

caused species such as smallmouth bass <strong>and</strong><br />

walleye pike to migrate out of the lake <strong>and</strong><br />

into the Seneca River. Species that remained<br />

in the lake were labeled unsafe for human<br />

consumption. The State of New York closed<br />

<strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> to fishing because of mercury<br />

contamination in 1970. In 1986, the lake<br />

Page 6<br />

Chapter 1: <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong> <strong>Progress</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Action</strong> Strategies

7.<br />

was reopened on a “catch <strong>and</strong> release” basis.<br />

The New York State Department of Health<br />

(NYSDOH) updated its prior advisory in<br />

1999, allowing fish to be kept, but advised<br />

consumption of no more than one caught<br />

fish meal per month, with the exception of<br />

walleye, which were not to be eaten. In 2007,<br />

a new health advisory was issued banning the<br />

consumption of largemouth <strong>and</strong> smallmouth<br />

bass over 15 inches <strong>and</strong> all walleye (<strong>Onondaga</strong><br />

County Department of Water Environment<br />

Protection (OCDWEP) 2006). It is<br />

recommended that anglers limit consumption<br />

of carp, channel catfish, white perch <strong>and</strong> all<br />

other species to no more than one meal per<br />

month. Women of childbearing age, children<br />

<strong>and</strong> infants are advised not to eat any fish from<br />

the lake (NYSDOH 2007).<br />

Inner Harbor <strong>and</strong> Shoreline Use<br />

After more than one hundred years of<br />

concentrated industrial <strong>and</strong> manufacturing<br />

practices along the lakeshore, there is<br />

community-wide interest in the restoration of<br />

<strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> <strong>and</strong> its watershed. The OLMP,<br />

however, focuses not only on improving the<br />

water quality of the lake, but also emphasizes<br />

the need to provide area residents with<br />

improved, safe recreation <strong>and</strong> entertainment<br />

8.<br />

opportunities, fishing access, <strong>and</strong> wildlife<br />

viewing (OLMC 1993).<br />

Non-Point Source Pollution<br />

Pollutants carried by stormwater runoff are<br />

an ongoing issue impacting the lake <strong>and</strong> its<br />

tributaries. Pesticides, petroleum products,<br />

road salt, fertilizers <strong>and</strong> sediment from<br />

urban <strong>and</strong> rural sources in the watershed<br />

are transported into the lake by the various<br />

tributaries <strong>and</strong> direct municipal storm sewer<br />

outfall discharges.<br />

Restoration Efforts<br />

A combination of factors, including the closing<br />

of Allied-Signal in 1986, the 1988 ASLF lawsuit,<br />

the 1989 State lawsuit, <strong>and</strong> a growing public<br />

awareness of the need to remediate the effects of<br />

past practices, set forth a path of focused efforts<br />

to restore <strong>and</strong> protect <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> <strong>and</strong> its<br />

watershed.<br />

Remediation work is ongoing in all eight areas<br />

outlined above. To date, over forty restoration<br />

projects have been completed, <strong>and</strong> many more are<br />

currently underway or planned for completion.<br />

The timeline on the following pages illustrates<br />

some of the major projects accomplished <strong>and</strong> milestones<br />

achieved throughout the life of the OLMC<br />

<strong>and</strong> OLP restoration efforts.<br />

Figure 1-6. Syracuse Inner Harbor. (Source: City of<br />

Syracuse)<br />

Chapter 1: <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong> <strong>Progress</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Action</strong> Strategies Page 7

A Historical<br />

1988<br />

►► Atlantic States Legal Foundation<br />

initiates a lawsuit against <strong>Onondaga</strong><br />

County, alleging violations of Federal<br />

water pollution st<strong>and</strong>ards.<br />

1989<br />

►► State of New York initiates a lawsuit<br />

against Allied-Signal, Inc. to compel<br />

cleanup of hazardous substances <strong>and</strong><br />

obtain natural resource damages.<br />

1990<br />

►► Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan<br />

initiates legislation in the Great <strong>Lake</strong>s<br />

Critical Programs Act of 1990 creating<br />

the <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> Management<br />

Conference (OLMC) to develop a plan<br />

that recommends priority corrective<br />

actions for restoration, conservation,<br />

<strong>and</strong> management of <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong>.<br />

1992<br />

►► A federal court approves a consent<br />

order for study of industrial pollution<br />

<strong>and</strong> development of a cleanup plan.<br />

1993<br />

►► The <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> Management<br />

Conference (OLMC) drafts A Plan for<br />

<strong>Action</strong>, on which the <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong><br />

Management Plan (OLMP) is based.<br />

1994<br />

►► The OLMC begins aquatic habitat<br />

restoration projects in <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong>.<br />

►► <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> is added to the<br />

Federal Superfund National Priorities<br />

List (NPL).<br />

1995<br />

►► The OLMC implements mudboil<br />

remediation projects to reduce flow of<br />

sediment to <strong>Onondaga</strong> Creek.<br />

1997<br />

►► New York State, Atlantic States Legal<br />

Foundation <strong>and</strong> <strong>Onondaga</strong> County<br />

reach an agreement, the Amended<br />

Consent Judgment (ACJ), on municipal<br />

wastewater collection <strong>and</strong> treatment<br />

improvements <strong>and</strong> a schedule to attain<br />

compliance with the Clean Water Act.<br />

1998<br />

►► A federal judge approves the ACJ<br />

ordering municipal wastewater collection<br />

<strong>and</strong> treatment improvements.<br />

The ACJ is a multi-year program with<br />

projects extending until 2012.<br />

1999<br />

►► The ACJ is incorporated into the<br />

OLMP.<br />

►► The New York State Department of<br />

Health (NYSDOH) lifts the advisory<br />

on eating certain species of fish<br />

(bass, white perch <strong>and</strong> catfish) from<br />

<strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong>. The NYSDOH maintains<br />

a health advisory recommending<br />

anglers limit consumption to one meal<br />

per month. The advisory to eat no<br />

walleye remains in effect. Women of<br />

childbearing age, infants <strong>and</strong> children<br />

under the age of 15 are advised not to<br />

eat any fish from the lake.<br />

►► Congressman James T. Walsh initiates<br />

legislation in the Water Resource<br />

Development Act of 1999 that replaces<br />

the OLMC with the <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong><br />

Partnership (OLP). The OLP, led by the<br />

U.S. Army Corp of Engineers, is tasked<br />

with implementing projects consistent<br />

with the OLMP.<br />

►► Allied-Signal, Inc. merges with<br />

Honeywell, Inc. <strong>and</strong> changes its name<br />

to Honeywell International, Inc.<br />

2000<br />

►► The OLP holds an inaugural ceremony<br />

on the shore of <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> on<br />

August 9, 2000.<br />

2001<br />

►► The OLP holds its first Annual<br />

<strong>Progress</strong> Meeting on October 29, 2001.<br />

Senior Partners update the community<br />

on the progress of the lake remediation<br />

effort.<br />

►► The last oil tanks are removed from<br />

the “Oil City” area near the Inner<br />

Harbor <strong>and</strong> remediation efforts begin.<br />

2002<br />

►► The OLP announces a new minigrant<br />

program, awarding $25,000 in<br />

grant awards for community-based<br />

education <strong>and</strong> stewardship projects<br />

associated with the <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong><br />

watershed.<br />

►► The first Annual <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> Day<br />

is held on June 8, 2002.<br />

►► The <strong>Onondaga</strong> County Department<br />

of Water Environment Protection<br />

launches the Angler’s Diary program<br />

inviting anglers to help assess the<br />

improvements in the lake. The public<br />

assists in monitoring lake improvements<br />

by recording the numbers, species<br />

<strong>and</strong> locations of fish caught.<br />

►► The New York State Department of<br />

Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC)<br />

issues a remedial investigation report<br />

detailing the extent of contamination<br />

within the lake <strong>and</strong> assessing the risk<br />

to humans <strong>and</strong> the environment based<br />

on an extensive 10-year remedial<br />

investigation performed by Honeywell<br />

International.<br />

2003<br />

►► Construction is completed on the<br />

Brighton Sewer Separation Project.<br />

2004<br />

►► Six streambank restoration projects<br />

are completed under the Rural<br />

Non-Point Source Pollution Best

Pe r s p e c t i v e<br />

Management Practices program. These<br />

projects help protect eroding streambanks<br />

<strong>and</strong> slow water current in order<br />

to reduce sedimentation <strong>and</strong> improve<br />

water clarity within <strong>Onondaga</strong> Creek.<br />

2005<br />

►► The U.S. Environmental Protection<br />

Agency (EPA) issues a National Remedy<br />

Review Board decision encouraging an<br />

open dialogue <strong>and</strong> close coordination<br />

between NYSDEC <strong>and</strong> other parties,<br />

including the <strong>Onondaga</strong> Nation, concerning<br />

the proposed remediation plan<br />

for <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong>.<br />

►► NYSDEC <strong>and</strong> EPA issue a Record of<br />

Decision outlining remediation plans<br />

for <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong>’s industrial pollution<br />

concerns.<br />

►► <strong>Onondaga</strong> County’s Metropolitan<br />

Syracuse Wastewater Treatment Plant<br />

(METRO) reaches Stage 3 Ammonia<br />

limit goal as set forth in ACJ eight years<br />

ahead of the scheduled deadline.<br />

Ammonia levels remain at safe levels<br />

for even the most sensitive aquatic<br />

organisms.<br />

►► OLP holds 5th Annual <strong>Progress</strong><br />

Meeting.<br />

►► Honeywell International, Inc.<br />

removes over eight tons of mercury<br />

from the Linden Chemicals <strong>and</strong> Plastics<br />

property through soil washing, preventing<br />

mercury contamination from<br />

the site from entering the lake.<br />

2006<br />

►► Honeywell International, Inc.<br />

completes a groundwater treatment<br />

plant at the former Allied Chemical,<br />

Willis Avenue site. The groundwater<br />

collection system will be an underground<br />

barrier about one <strong>and</strong> one-half<br />

miles long that blocks contaminated<br />

groundwater from reaching the lake.<br />

►► Phosphorus release from METRO<br />

to <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> is reduced from<br />

200 pounds per day to 50 pounds<br />

per day (a 75 percent reduction) with<br />

completion of an upgraded phosphorus<br />

removal facility.<br />

►► City of Syracuse completes Phase I of<br />

Valley Drive Sewer Separation Project.<br />

2007<br />

►► Federal court approves consent<br />

decree obligating Honeywell to implement<br />

the NYSDEC/EPA cleanup plan for<br />

the lake bottom’s industrial pollution.<br />

►► The 2007 Bassmasters Majors<br />

Tournament, involving the world’s top<br />

52 anglers, is hosted at <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong>,<br />

attracting bass fishermen from around<br />

the country <strong>and</strong> world.<br />

►► NYSDOH updates health advisory<br />

banning the consumption of largemouth<br />

<strong>and</strong> smallmouth bass <strong>and</strong><br />

walleye. Other existing advisories are<br />

maintained.<br />

►► Wetl<strong>and</strong>s restoration at former<br />

Linden Chemical <strong>and</strong> Plastics (LCP)<br />

site is completed. Nearly 12,000 trees<br />

<strong>and</strong> plants are introduced to restore<br />

wetl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> habitat in the <strong>Onondaga</strong><br />

<strong>Lake</strong> watershed.<br />

►► State University of New York<br />

College of Environmental Science <strong>and</strong><br />

Forestry (SUNY ESF) <strong>and</strong> Honeywell<br />

International, Inc. harvest one acre of<br />

shrub willows on Solvay Settling Basin<br />

#13 in Camillus. The shrub willows help<br />

filter contamination from the groundwater<br />

in the waste beds.<br />

►► Honeywell International, Inc. signs<br />

a Consent Decree to perform the<br />

Remedial Design <strong>and</strong> Remedial <strong>Action</strong><br />

for the <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> Bottom Site.<br />

2008<br />

►► Honeywell International, Inc. begins<br />

second phase construction of the<br />

groundwater barrier wall along the<br />

Willis/Causeway section of the lake.<br />

►► North American Fishing Club<br />

names <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> one of the<br />

United States’ top ten bass fishing<br />

destinations.<br />

►► Working with ASLF, <strong>Onondaga</strong><br />

Nation, <strong>and</strong> NYSDEC, <strong>Onondaga</strong> County<br />

obtains a moratorium on construction<br />

of the proposed treatment facilities<br />

so that alternative methodologies,<br />

including green infrastructure, could<br />

be evaluated as part of the CSO abatement<br />

program.<br />

►► A Microbial Trackdown program<br />

is implemented to identify sources<br />

of bacteria to <strong>Onondaga</strong> Creek <strong>and</strong><br />

Harbor Brook.<br />

2009<br />

►► The draft <strong>Onondaga</strong> Creek<br />

Conceptual Revitalization Plan is<br />

released for public review.<br />

►► NYSDEC issues final Remedial Design<br />

Work Plan for the <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong><br />

Bottom NPL subsite. NYSDEC <strong>and</strong> EPA<br />

issue decision documents outlining<br />

remediation plans for the Geddes<br />

Brook/Ninemile Creek site.<br />

►► NYSDEC issues a Citizen Participation<br />

Plan designed to enhance public input<br />

<strong>and</strong> involvement in the <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong><br />

Bottom cleanup project.<br />

►► A Fourth Amendment to the ACJ is<br />

adopted <strong>and</strong> approved by the federal<br />

court, incorporating green infrastructure<br />

methodologies into the CSO<br />

abatement process.

Page 10<br />

Chapter 1: <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong> <strong>Progress</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Action</strong> Strategies

Chapter 2: <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> Management Plan Status Report<br />

Figure 2-1. Sunset on <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong>. (Source: 2002 OLP Photo Contest, photo by Paul Sanford)<br />

Chapter 2: <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong> <strong>Progress</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Action</strong> Strategies Page 11

Introduction<br />

In December 1993, the <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> Management<br />

Conference (OLMC) released the <strong>Onondaga</strong><br />

<strong>Lake</strong> Management Plan (OLMP). The plan<br />

outlines the major environmental problems facing<br />

the lake <strong>and</strong> makes recommendations for its<br />

restoration. The Water Resources Development<br />

Act tasked the <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> Partnership (OLP)<br />

with developing <strong>and</strong> implementing water quality<br />

improvement projects for the lake <strong>and</strong> surrounding<br />

watershed. As stated in Chapter 1, the OLMC<br />

identified eight major strategic areas: Municipal<br />

Sewer Discharge, Combined Sewer Overflows<br />

(CSOs), Industrial National Priorities List (NPL)<br />

site <strong>and</strong> sub-sites, Industrial non-NPL sites, Hydrogeologic<br />

Investigations, Habitat <strong>and</strong> Fisheries,<br />

Inner Harbor <strong>and</strong> Shoreline Use, <strong>and</strong> Non-Point<br />

Source Pollution. Using these strategic areas, the<br />

OLP set major cleanup goals in its effort to restore<br />

the lake, its tributaries <strong>and</strong> the watershed. Over the<br />

past eight years, more than 40 restoration projects<br />

have been completed, <strong>and</strong> there are over 20 active<br />

projects being implemented.<br />

This report presents the eight strategic areas by a<br />

general description of the pollution problems, the<br />

recommendations made by the OLMP, the strategies<br />

utilized for remediation, progress made, <strong>and</strong><br />

the need for future remediation efforts. Additional<br />

requirements for <strong>Onondaga</strong> County’s Metropolitan<br />

Syracuse Wastewater Treatment Plant (METRO)<br />

sewer discharge <strong>and</strong> combined sewer overflows are<br />

outlined in the 1997 Amended Consent Judgment<br />

(ACJ). Remediation requirements for properties<br />

owned or affected by Honeywell International,<br />

General Motors, Niagara Mohawk/National<br />

Grid, <strong>and</strong> the town of Salina are discussed in the<br />

Records of Decision <strong>and</strong> various Consent Orders<br />

pertaining to those sites. These items are discussed<br />

within their corresponding strategic area. Since<br />

the requirements for correction of water quality<br />

problems related to Municipal Sewer Discharge<br />

<strong>and</strong> Combined Sewer Overflows are both impacted<br />

by the ACJ, these two strategic areas are combined<br />

for clarity purposes. Similarly, NPL <strong>and</strong> non-NPL<br />

industrial sites are discussed together in one<br />

section concerning industrial pollution; all of the<br />

sites in both strategic areas are subject to consent<br />

orders that identify potentially responsible parties<br />

<strong>and</strong> outline the requirements to which those parties<br />

must adhere.<br />

Strategic Areas 1&2: Municipal Sewer<br />

Discharge <strong>and</strong> Combined Sewer<br />

Overflows<br />

History<br />

METRO services the wastewater treatment needs<br />

of the city of Syracuse <strong>and</strong> several surrounding<br />

communities. Built in the 1960s, the plant was<br />

upgraded in 1979 <strong>and</strong> again in 1981 to provide<br />

more complete removal of pollutants. Following<br />

these upgrades, <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> continued<br />

to show excessively high levels of ammonia<br />

<strong>and</strong> phosphorus, resulting in high toxicity, algae<br />

blooms, decreased oxygen, <strong>and</strong> poor water clarity.<br />

The 1997 ACJ addressed strategies for h<strong>and</strong>ling<br />

ammonia, which has been shown to interfere with<br />

the reproduction <strong>and</strong> migration of fish, <strong>and</strong> phosphorus,<br />

which leads to algae growth <strong>and</strong> oxygen<br />

depletion.<br />

In 1988, a lawsuit was filed by Atlantic States<br />

Legal Foundation against <strong>Onondaga</strong> County,<br />

alleging that METRO <strong>and</strong> CSO discharges violated<br />

Federal Water Pollution St<strong>and</strong>ards. The State of<br />

New York joined as a plaintiff, <strong>and</strong> the parties<br />

endeavored to settle the litigation in 1989 through<br />

the METRO consent judgment. In 1997, the prior<br />

METRO consent judgment was superseded when<br />

the parties reached an agreement on wastewater<br />

treatment plant <strong>and</strong> collection system improvements<br />

<strong>and</strong> a schedule for attaining compliance<br />

with the Clean Water Act by 2012. This agreement<br />

is known as the ACJ.<br />

Throughout the city of Syracuse, there are sewers<br />

that carry both sanitary sewage <strong>and</strong> stormwater<br />

from streets. During dry weather, these sewers<br />

Page 12<br />

Chapter 2: <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong> <strong>Progress</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Action</strong> Strategies

carry all sanitary sewage to METRO; however,<br />

during intense rainfalls, the amount of stormwater<br />

entering the combined sewer system exceeds the<br />

system’s capacity, resulting in overflow <strong>and</strong> discharges<br />

of untreated wastewater (stormwater <strong>and</strong><br />

sanitary sewage) into the tributaries of <strong>Onondaga</strong><br />

<strong>Lake</strong>. The frequency with which CSOs actually<br />

occur varies from one CSO discharge location<br />

to the next, but generally ranges from only a few<br />

times per year to as many as 60 times per year.<br />

CSOs are a major contributor of bacteria, floating<br />

trash, organic material, solids <strong>and</strong> grit to the lake<br />

<strong>and</strong> its tributaries. Elevated bacteria concentrations<br />

in <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> can occur for up to three days<br />

following a storm event.<br />

Floating trash <strong>and</strong> debris is a concern in <strong>Onondaga</strong><br />

<strong>Lake</strong> <strong>and</strong> its tributaries. Floating trash is not only<br />

an aesthetic problem, it can also have chemical<br />

<strong>and</strong> biological impacts including interference with<br />

the growth of aquatic plants, leaching of pollutants<br />

from trash, <strong>and</strong> hazards to wildlife through<br />

ingestion or entanglement. Debris often enters<br />

<strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> <strong>and</strong> its tributaries through CSOs<br />

<strong>and</strong> storm sewers, but also is blown by wind into<br />

the waterways.<br />

Recommendations from the OLMP<br />

The OLMC made the following recommendations<br />

concerning METRO <strong>and</strong> CSOs in 1993:<br />

•• An out-of-lake discharge of wastewater currently<br />

treated at METRO is endorsed. At the present time, the<br />

most promising discharge alternatives include a diversion<br />

of some influent flow to an exp<strong>and</strong>ed Baldwinsville-Seneca<br />

Knolls treatment facility, <strong>and</strong> a diversion<br />

of the remaining METRO effluent to the Seneca River<br />

below the <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> Outlet. Effluent limitations<br />

for both discharges should be defined through the use<br />

of the <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> <strong>and</strong> Seneca River water quality<br />

models. The diversion should be implemented as soon<br />

as possible.<br />

•• <strong>Onondaga</strong> County <strong>and</strong> the city of Syracuse should<br />

coordinate any construction activity relating to the<br />

renovation of METRO so as to minimize, to the extent<br />

possible, any negative impact on lakefront development<br />

<strong>and</strong> the surrounding community.<br />

•• <strong>Onondaga</strong> County should implement a pilot<br />

project to test CSO control technology. The project<br />

should consist of the design <strong>and</strong> construction of two<br />

CSO storage <strong>and</strong> treatment facilities. <strong>Onondaga</strong> County<br />

should seek sources of funding including the Water<br />

Resources <strong>and</strong> Development Act of 1992 to the extent<br />

available to support this effort.<br />

•• Using appropriate treatment methods, <strong>Onondaga</strong><br />

County should provide additional storage <strong>and</strong>/or<br />

treatment facilities to control remaining CSOs. The<br />

remediation of the CSOs should be implemented as<br />

soon as possible.<br />

•• The city of Syracuse <strong>and</strong> <strong>Onondaga</strong> County should<br />

work together to design <strong>and</strong> construct engineering<br />

solutions to eliminate floatables <strong>and</strong> silt in <strong>Onondaga</strong><br />

Creek over the next several years. The U.S. Army Corps<br />

of Engineers should assist consistent with its authority.<br />

•• <strong>Onondaga</strong> County <strong>and</strong> the city of Syracuse should<br />

coordinate to ensure, to the extent possible, that CSO<br />

treatment projects are compatible with plans by the<br />

city <strong>and</strong> the New York State Thruway Authority for<br />

development of the Inner Harbor.<br />

Requirements of the ACJ<br />

The purpose of the ACJ was to improve the water<br />

quality of <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> <strong>and</strong> to assure the<br />

County’s compliance with all state <strong>and</strong> federal<br />

water quality regulations. Over 30 projects were<br />

scheduled for completion within a 15-year period.<br />

The ACJ set time schedules for specific tasks, such<br />

as completion of environmental review, beginning<br />

of construction, <strong>and</strong> start of operations. The<br />

various projects under the ACJ are divided into<br />

three main categories: Improvements to METRO;<br />

CSO Construction; Ambient Monitoring Program.<br />

The OLMC passed a resolution in 1998 amending<br />

the OLMP to incorporate the ACJ <strong>and</strong> adopt its<br />

objectives as an integral part of the OLMP. There-<br />

Chapter 2: <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong> <strong>Progress</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Action</strong> Strategies Page 13

fore, it is important to note that as amendments to<br />

the ACJ occur, the OLMP is likewise amended.<br />

Improvements to METRO<br />

Since METRO has been identified as the main<br />

contributor of phosphorus <strong>and</strong> ammonia in the<br />

lake, the ACJ requires <strong>Onondaga</strong> County to<br />

upgrade the ammonia <strong>and</strong> phosphorus treatment<br />

of the wastewater discharges from the METRO<br />

plant. The ACJ calls for a three-phase reduction of<br />

ammonia <strong>and</strong> phosphorus in the effluent.<br />

METRO Phase I<br />

Phase I called for “no net increase” on existing<br />

effluent limits for ammonia discharged from<br />

METRO through May 1, 2004, <strong>and</strong> “no net<br />

increase” on existing effluent limits for phosphorus<br />

discharged from METRO through April 1, 2006.<br />

METRO Phase II<br />

Phase II required that METRO meet a 30-day<br />

average interim ammonia effluent limit of 2 milligrams<br />

per liter (mg/L) in the summer <strong>and</strong> 4 mg/L<br />

in the winter no later than May 1, 2004. To meet<br />

this limit, the County constructed an ammonia<br />

reduction facility.<br />

METRO was required to meet a 12-month rolling<br />

average interim phosphorus limit of 0.12 mg/L, no<br />

later than April 1, 2006.<br />

that on any given day, the average level over the<br />

preceding 12 months cannot have exceeded the<br />

limit.) In the event that this capacity cannot be<br />

demonstrated, a diversion of flow from METRO<br />

to the Seneca River or implementation of other<br />

engineering alternative that results in compliance<br />

with water quality st<strong>and</strong>ards must be completed by<br />

December 31, 2015.<br />

CSO Construction<br />

The ACJ required the County to address 66 CSOs<br />

(this number was later revised to 70 CSOs) <strong>and</strong><br />

to construct two Regional Treatment Facilities<br />

(RTFs) <strong>and</strong> multiple Floatables Control Facilities<br />

(FCFs). RTFs are designed to receive sewage<br />

flows from several CSOs during high flow events<br />

<strong>and</strong> remove floatables, nutrients, <strong>and</strong> other pollutants<br />

either by storage of the overflow volume<br />

itself or by passing the discharge through a water<br />

treatment unit within the facility. FCFs are structures<br />

<strong>and</strong>/or equipment that remove floating debris<br />

(including trash, waste matter, <strong>and</strong> other objects)<br />

from sewer discharges using net bags, screens, or<br />

other devices.<br />

Ambient Monitoring Program (AMP)<br />

The ACJ requires <strong>Onondaga</strong> County to monitor<br />

conditions of the lake, its tributaries <strong>and</strong> the<br />

Seneca River to evaluate how improvements to<br />

METRO Phase III<br />

Phase III requires METRO to meet a final 30-day<br />

average effluent limit for ammonia of 1.2 mg/L in<br />

the summer <strong>and</strong> 2.4 mg/L in the winter, no later<br />

than December 1, 2012.<br />

Under Phase III, <strong>Onondaga</strong> County is also<br />

required to demonstrate by December 31, 2011<br />

that METRO will be able to meet a final effluent<br />

limit for phosphorus of 0.02 mg/L, measured as a<br />

12-month rolling average, on or before December<br />

31, 2015. (A 12-month rolling average means<br />

Figure 2-2.<br />

Aerial view of new facility at METRO.<br />

(Source: OCDWEP)<br />

Page 14<br />

Chapter 2: <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong> <strong>Progress</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Action</strong> Strategies

Phosphorus is the key nutrient supporting algal growth. Too much phosphorus causes excessive algal growth,<br />

which turns the lake water green <strong>and</strong> cloudy <strong>and</strong> contributes to low oxygen levels.<br />

Phosphorus Discharged<br />

authorized Summer the use of Phosphorus green infrastructure Levels in in<br />

to <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> from Metro<br />

combination <strong>Onondaga</strong> with traditional <strong>Lake</strong> Upper engineering Waters practices<br />

600<br />

(grey 140 infrastructure) to reduce CSO volume during<br />

500<br />

120<br />

wet weather. Green infrastructure involves the use<br />

400<br />

100<br />

<strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> of existing 80 l<strong>and</strong>scape features, soils, <strong>and</strong> vegetation<br />

to 60capture or infiltrate stormwater runoff,<br />

Page 3<br />

<strong>Progress</strong> 300 Report: July, 2009<br />

200<br />

40<br />

How have 100 improvements in wastewater treatment affected thereby reducing the volume of flow contributing<br />

20 ammonia levels in <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong>?<br />

0<br />

to CSOs. 0 In recognition of the anticipated volume<br />

High concentrations of ammonia can be harmful to sensitive reduction aquatic that life, will such be achieved as young through fish. <strong>Onondaga</strong> the use County<br />

90 92 94 96 98 00 02 04 06 08<br />

90 92 94 96 98 00 02 04 06 08<br />

has completed major upgrades<br />

Year<br />

at the Metro plant that reduced of green the infrastructure, amount of ammonia-N the 2009 Year ACJ discharged amendment to the lake<br />

from the treatment plant. An advanced treatment system eliminated came the on-line requirement in 2004; for <strong>Onondaga</strong> as a result, County ammonia-N<br />

concentrations Improvements Figure 2-3. in Average at the the lake Metro daily have phosphorus plant declined have discharge reduced <strong>and</strong> meet from phosphorus<br />

discharges METRO, 1990-2008. to the lake (Source: from the OCDWEP) treatment plant Creek, plant have as well resulted as on in State substantially Fair Boulevard lower phosphorus adjacent<br />

state st<strong>and</strong>ards to Reductions construct developed in RTFs phosphorus in Armory for protection discharges Square of on from aquatic <strong>Onondaga</strong> the life. Metro<br />

by more than 80%. Since the advanced treatment<br />

concentrations in the lake water in recent years, down to<br />

Ammonia-N Discharged<br />

to Harbor Brook. System-wide, on an average<br />

system was completed in 2005, loading has been less 15 ppb in 2008,<br />

Annual<br />

comparable<br />

Ammonia-N<br />

to Oneida<br />

Levels<br />

<strong>Lake</strong>.<br />

in<br />

to <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> from Metro<br />

annual basis, <strong>Onondaga</strong> CSO volume <strong>Lake</strong> will Upper be gradually Waters<br />

than 100 10,000 lbs per day.<br />

3.0<br />

reduced by 95 percent by December 31, 2018.<br />

pounds per day<br />

pounds per day<br />

8,000<br />

2.0<br />

6,000<br />

1.5<br />

4,000<br />

Phosphorus Loading to ACJ <strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Progress</strong><br />

1.0<br />

<strong>Lake</strong>: <strong>and</strong> Effects on <strong>Lake</strong> Water<br />

2,000<br />

Metro <strong>and</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong> Quality Sources 0.5<br />

0<br />

0.0<br />

90 92 94 96 98 00 02 04 06 08 METRO has 90improved 92 94 its 96capacity 98 00to 02 safely, 04 efficiently<br />

<strong>and</strong> Metro effectively treat wastewater over the<br />

06 08<br />

Year<br />

Year<br />

39%<br />

26%<br />

6 1%<br />

past two decades. <strong>Watershed</strong> Treatment improvement projects<br />

Figure 2-4. Average daily ammonia discharge from<br />

74%<br />

How have improvements METRO, 1990-2008. in (Source: wastewater OCDWEP) collection <strong>and</strong> included treatment an odor affected control bacteria upgrade, levels aeration in the system lake?<br />

Areas of Syracuse are served by combined sewer systems upgrade, (CSOs) digital which system carry improvements, both sewage <strong>and</strong> increased storm runoff.<br />

These METRO pipes <strong>and</strong> can the overflow CSOs effect during the 1990-2004 periods quality of of heavy water rain 2008 <strong>and</strong> capacity snowmelt, for chemical allowing storage a mixture <strong>and</strong> of feed stormwater facilities, <strong>and</strong> raw<br />

sewage in the to lake flow <strong>and</strong> into river. creeks The ACJ <strong>and</strong> specifies ultimately the reach objectives<br />

of the program, types of monitoring to be<br />

<strong>Onondaga</strong> digester <strong>Lake</strong>. modifications, Monitoring data <strong>and</strong> advanced document ammonia elevated <strong>and</strong> bacteria<br />

levels phosphorus removal.<br />

With during the recent wet improvements weather. <strong>Onondaga</strong> at the Metro County plant, continues runoff from to the implement watershed contributes projects, including the majority treatment of phosphorus facilities, to to<br />

control conducted <strong>Onondaga</strong> storm <strong>Lake</strong>. <strong>and</strong> runoff defines Prior <strong>and</strong> to a 2005, combined schedule the Metro for sewer the plant program. overflows. contributed approximately County officials 60% of recently the yearly have phosphorus begun load. evaluating the<br />

As a result of the advanced ammonia removal<br />

potential use of “green” infrastructure to help manage urban storm runoff. Green infrastructure encourages<br />

project, <strong>Onondaga</strong> County met the final Phase III<br />

infiltration, Amendments capture, to ACJ <strong>and</strong> reuse of storm runoff before it enters the sewer system. Monitoring data have also<br />

effluent requirements for ammonia in 2004. The<br />

identified elevated<br />

An amendment Summer bacteria<br />

to the Algal ACJ Bloom levels<br />

in December Frequency in streams during dry weather in certain<br />

2006 County has Minimum areas.<br />

also met Oxygen A cooperative<br />

the requirement Concentration program, funded<br />

to reduce<br />

by the<br />

suspended<br />

<strong>Onondaga</strong><br />

a Measured previously<br />

<strong>Lake</strong> Partnership as required Chlorophyll-a oxygenation<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>Onondaga</strong><br />

demonstration<br />

sources project of bacteria,<br />

County, is underway of Upper to Waters identify in <strong>and</strong> October remediate these dry<br />

the phosphorus 10 level to 0.12 mg/L, as required<br />

weather 100%<br />

80%<br />

for the No lake. blooms which This in may 1995 decision include or 2008 was leaky pipes <strong>and</strong>/or illicit connections.<br />

in Phase 8 II. Figures 2-3 <strong>and</strong> 2-4 show the decline<br />

based 60% on data from the AMP, which demonstrated in phosphorus <strong>and</strong> ammonia discharged from<br />

40%<br />

Fecal Coliform Bacteria, April-October 2008<br />

Fecal Coliform Bacteria Summer<br />

6<br />

that 20% the Percent lake’s oxygen of months levels in compliance had significantly<br />

with METRO in Geometric recent years. Average Concentration<br />

4<br />

improved. 0% The 2002006 cells/100 amendment ml st<strong>and</strong>ard also included<br />

250<br />

changes 90allowing 92 94for 96the 98 consolidation 00 02 04of the 06 08 The original 2200<br />

South End<br />

Maple Bay,<br />

Willow Bay, 100%<br />

ACJ outlined a plan to address 66<br />

ammonia 100%<br />

<strong>and</strong> phosphorus Year removal facilities, use CSOs. That 0150<br />

North End<br />

number was later revised to 70 CSOs.<br />

<strong>Onondaga</strong> <strong>Lake</strong> Park, 100%<br />

of a skimmer boat in the Inner Harbor rather than As of February 100 90 92008, 94 12 96CSOs 98 00 were 02eliminated,<br />

04 06 08<br />

Minor bloom (>15 ppb) Major bloom (>30 ppb)<br />

Year<br />

a boom in <strong>Onondaga</strong> Creek, <strong>and</strong> the design <strong>and</strong> 11 were addressed 50 to accommodate peak discharge<br />

Bloody Brook, 100%<br />

construction of a CSO abatement plan for Harbor of a one-year 0 storm, <strong>and</strong> 4 CSOs were addressed<br />

Less phosphorus Ninemile,<br />