"Heroic Grace" catalog - UCLA Film & Television Archive

"Heroic Grace" catalog - UCLA Film & Television Archive

"Heroic Grace" catalog - UCLA Film & Television Archive

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

films with King Hu) and Lau Kar-leung (working with Zhang Che before<br />

launching his own career as a director) developed long shots which cut<br />

smoothly together through exact control of what was pictorially salient<br />

at each moment: one or two bodies thrusting or flipping across the<br />

widescreen frame. The much-maligned zoom lens played a crucial role<br />

in this long-shot strategy, not only picking out the most salient action,<br />

but also lending its own rhythm to redouble that of the figures. The shot<br />

can start with a rapid zoom back, echoing the first whoosh of action, or<br />

the zoom can punch in and out, reinforcing the action’s rhythm.<br />

The opening test of strength between Hong (David Jiang Dawei/<br />

David Chiang) and Ma (Di Long/Ti Lung) in BLOOD BROTHERS can stand<br />

as a stripped-down model of the full-shot approach, which Zhang Che<br />

refined across a dozen years. The same principles rule LAST HURRAH FOR<br />

CHIVALRY (HAO XIA, 1979), the work of Zhang’s assistant and pupil John<br />

Woo. Look, for example, at the six-minute combat between Zhang (Wai<br />

Pak) and Pray (Fung Hak-on), in which 75 shots render each thrust and<br />

blow utterly intelligible, the whole sequence but a warm-up for the two<br />

grueling battles in the finale—which reveals the fearsome Pak as only a<br />

subsidiary villain after all. The Hong Kong martial arts style was far from<br />

uniform, however: against Zhang’s no-frills pan-and-zoom fights stands<br />

the pictorially dense, almost decorative imagery to be found in KILLER<br />

CLANS (LIUXING HUDIE JIAN, 1976) and other Chu Yuan (Chor Yuen) works.<br />

A younger generation of choreographers began to explore a more<br />

“precisionist” approach to staging and cutting combat. Here the action<br />

is built out of many more detail shots—a face, a body part, a weapon<br />

lashing out—and the rhythm comes not only from the figures’ action but<br />

also from a barrage of hyper-composed details, which we assemble into<br />

an integrated action. This became the dominant style of Woo’s 1980s<br />

Triad films, Tsui’s PEKING OPERA BLUES (DI MA DAN/DAO MA DAN, 1986),<br />

and Ching Siu-tung’s A CHINESE GHOST STORY (SIN LUI YAO WAN/QIANNÜ<br />

YOUHUN, 1987). The fights in the gangster’s lair at the close of Corey<br />

Yuen Kwai’s YES, MADAM! (WONG GA BAI CHE/HUANGJIA SHIJIE, 1985) perfectly<br />

illustrate this approach, with Michelle Yeoh’s dodges and feints captured<br />

in a flurry of tight, exactly-judged setups. And skillful choreographer-directors<br />

like Jackie Chan fused the two approaches; the climactic<br />

mall fight of POLICE STORY (GING CHAT GOO SI/JINGCHA GUSHI, 1985)<br />

superbly balances full-shot choreography with passages built out<br />

of precise details.<br />

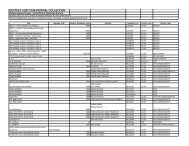

Fig.1<br />

Fig.2<br />

One of the pioneers of rapid editing and rhythmic staging was King<br />

Hu, who perhaps best exemplifies the range of experimentation available<br />

in this kinetic genre. He was famous as a fast cutter (once boasting of<br />

making China’s first eight-frame cut), but just as important was his<br />

powerful awareness of screen space. Allowing his choreographer Han<br />

Yingjie to model his fights on Chinese opera rather than real kung fu, he<br />

experimented with unnerving, almost subliminal spatial effects. In the<br />

stupendously inventive DRAGON INN, as the woman Zhu (Polly Shangguan<br />

Lingfeng) fights with an adversary outside the inn, the camera tracks<br />

back to catch the crumbling edge of a wall; she may seem to be trapped<br />

(Fig. 1). A quarter of a second (that is, six frames) before the cut, a dim<br />

12<br />

shape pops up at the wall, and Chu starts to stab it (Fig. 2). Cut to a<br />

disorienting extreme long shot in which her attacker is already recoiling<br />

in agony (Fig. 3). The attack and the response are over before we have<br />

fully registered them. No less bold is the moment when the fleeing Mao<br />

(played by choreographer Han Yingjie) ducks behind a wall in long shot<br />

(Fig. 4) and appears at another end of it instantly, leaping up to the inn<br />

balcony (Fig. 5). Not only does the wall hide the mini-trampoline, but<br />

(allowing for the use of a double) it suggests that Mao commands an<br />

otherworldly speed. Hu’s films are full of such ingenious spatial twists,<br />

driving home the agility and resourcefulness of his fighters.<br />

For many young viewers today, the swordplay and kung fu films of<br />

Hong Kong’s Golden Age are less immediately accessible than the gunplay<br />

dramas and supernatural fantasies of the 1980s and ’90s. The suavity<br />

of Chow Yun-fat may seem more appealing than the self-torment of<br />

ONE-ARMED SWORDSMAN. And the 1960s and ’70s movies may seem<br />

embarrassingly rooted in crude conventions and local limits of budget,<br />

time, taste, and imagination. In fact, though, the crime and costume<br />

sagas owe everything to these strange and wondrous creations. Here we<br />

find stories which are refreshingly baggy, full of unexpected turns and<br />

returns. Here protagonists are defined through their obsessive pursuit<br />

of moral and professional achievement. And here we encounter a cinematic<br />

technique aiming to carry the characters’ percussive energy down<br />

into the fibers of our bodies. These films, cranked out by directors<br />

almost completely unaware of experimental cinema, made a revolution<br />

in the way movies work, and work upon us.<br />

copyright @ 2003, David Bordwell<br />

David Bordwell teaches at the University of Wisconsin—Madison,<br />

where he is Hilldale Professor of Humanities and Jacques Ledoux<br />

Professor of <strong>Film</strong> Studies. He has written several books on film theory<br />

and history, including two on Asian cinema: Ozu and the Poetics of<br />

Cinema (Princeton, 1988) and Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the<br />

Art of Entertainment (Harvard, 2000). He is completing a book on cinematic<br />

staging as practiced by Kenji Mizoguchi, Hou Hsiao-hsien, and<br />

other filmmakers.<br />

Fig.3<br />

Fig.4<br />

Fig.5