Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

12<br />

Hogarth’s audience would choose to be themselves, some sense<br />

of humanity exists. In the Rake series, Sarah weeps at Tom’s side.<br />

Amidst the lunacy, she nevertheless displays her sustained love<br />

for him, or, at the very least, feelings of deepest compassion.<br />

Now look at Goya’s inmates in Interior of a <strong>Prison</strong>: all male, and<br />

like Tom, in rags or naked, stripped of any social status that might<br />

once have existed. But there is no interaction between any of<br />

them, only silence, no knowing glances towards the spectator, no<br />

gallows humour. In their resigned wretchedness they no longer<br />

hope to receive any visitors – not even those prison tourists that<br />

paid to gawp at those less fortunate than themselves. These men<br />

are going nowhere and seeing no one. This is it. Nothing. Their<br />

existence is utterly devoid of love or compassion, until, eventually,<br />

they will be released by death.<br />

Hogarth and Goya differ in their approach to the depiction of<br />

prison life principally because Hogarth sought to entertain<br />

whilst Goya did not. Hogarth’s paintings for both the Harlot and<br />

the Rake were translated into print form for a mass audience.<br />

Goya’s cabinet series, as he had informed Iriate in his letter of<br />

4th January 1794, were intended for no one other than himself.<br />

But as he shared this body of new work with the Academicians<br />

of San Fernando, it is likely that Goya was demonstrating to his<br />

colleagues, as he almost certainly was to himself in the months<br />

beforehand, that in spite of his debilitating illness, his mind, his<br />

imagination, his ability for ‘caprice’, remained intact. In fact, not<br />

only had Goya’s mental agility and artistic ability been preserved,<br />

in the months of illness and recuperation he had reached greater<br />

heights than he had previously achieved. Certainly he sought<br />

approval from his fellow Academicians, but his eagerness to show<br />

his cabinet paintings strongly suggests that Goya, previously<br />

searching for a clarity of artistic direction, now knew that he had<br />

found it.<br />

Following his presentation of the cabinet pictures to the Academy,<br />

Goya continued his slow rehabilitation. He summed up his<br />

condition to Zapater in April 1794:<br />

“I am much the same, in so far as my health, some times<br />

raving with a mood that I myself cannot stand, other times,<br />

more tempered, as now when I take up the pen to write<br />

to you, and I am already tired, I can only say that Monday,<br />

God willing, I will go to the bullfight and I would want you<br />

to accompany me.” 17<br />

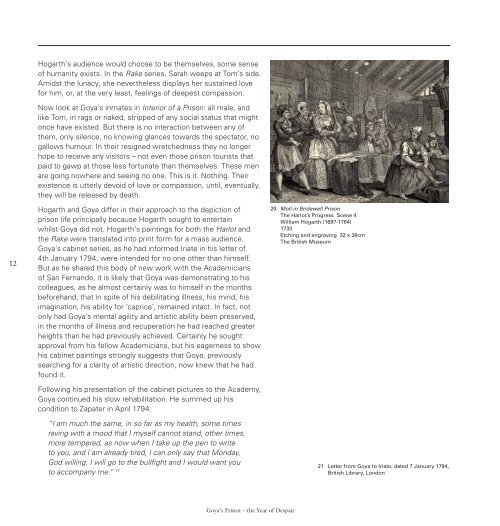

20 Moll in Bridewell <strong>Prison</strong><br />

The Harlot’s Progress Scene 4<br />

William Hogarth (1697-1764)<br />

1733<br />

Etching and engraving 32 x 38cm<br />

The British Museum<br />

21 Letter from Goya to Iriate, dated 7 January 1794,<br />

British Library, London<br />

Goya’s <strong>Prison</strong> – the Year of Despair