You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

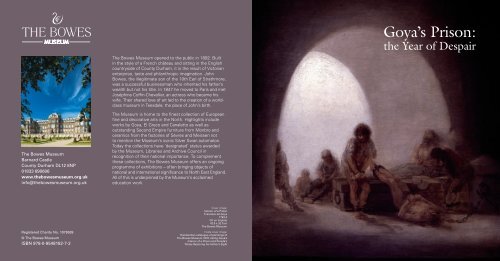

Goya’s <strong>Prison</strong>:<br />

the Year of Despair<br />

The Bowes Museum opened to the public in 1892. Built<br />

in the style of a French château and sitting in the English<br />

countryside of County Durham, it is the result of Victorian<br />

enterprise, taste and philanthropic imagination. John<br />

Bowes, the illegitimate son of the 10th Earl of Strathmore,<br />

was a successful businessman who inherited his father’s<br />

wealth but not his title. In 1847 he moved to Paris and met<br />

Joséphine Coffin-Chevallier, an actress who became his<br />

wife. Their shared love of art led to the creation of a worldclass<br />

museum in Teesdale, the place of John’s birth.<br />

The Bowes Museum<br />

Barnard Castle<br />

County Durham DL12 8NP<br />

01833 690606<br />

www.thebowesmuseum.org.uk<br />

info@thebowesmuseum.org.uk<br />

The Museum is home to the finest collection of European<br />

fine and decorative arts in the North. Highlights include<br />

works by Goya, El Greco and Canaletto as well as<br />

outstanding Second Empire furniture from Monbro and<br />

ceramics from the factories of Sèvres and Meissen not<br />

to mention the Museum’s iconic Silver Swan automaton.<br />

Today the collections have ‘designated’ status awarded<br />

by the Museum, Libraries and Archive Council in<br />

recognition of their national importance. To complement<br />

these collections, The Bowes Museum offers an ongoing<br />

programme of exhibitions – often bringing objects of<br />

national and international significance to North East England.<br />

All of this is underpinned by the Museum’s acclaimed<br />

education work.<br />

Registered Charity No. 1079639<br />

© The Bowes Museum<br />

ISBN 978-0-9548182-7-2<br />

Cover image:<br />

Interior of a <strong>Prison</strong><br />

Francisco de Goya<br />

1793-4<br />

Oil on tinplate<br />

42.9 x 32.7cm<br />

The Bowes Museum<br />

Inside cover image:<br />

Handwritten catalogue of paintings of<br />

The Bowes Museum 1878, listing Goya’s<br />

Interior of a <strong>Prison</strong> and Pereda’s<br />

Tobias Restoring his Father’s Sight

Goya’s <strong>Prison</strong> – the Year of Despair<br />

Adrian Jenkins

Chairman’s Foreword<br />

In 1892 when The Bowes Museum opened its doors to the public, amongst the paintings<br />

it housed, seventy six were by Spanish painters. At this time the National Gallery in London<br />

owned twenty Spanish paintings by ten artists (six by Murillo, five by Velásquez, two by Ribera<br />

and one each by El Greco, Juan de Flandes, León, Mazo, Morales, Valdés Leal and Zurbarán).<br />

Thus in 1892 The Bowes Museum provided the public with the largest collection of Spanish<br />

paintings in Britain. Today it is still, after the National Gallery, the best place to explore Spanish<br />

painting, its collections quite distinct from those in national collections.<br />

In this in-focus study, our Director, Adrian Jenkins has concentrated on one Spanish painting,<br />

Interior of a <strong>Prison</strong> by Francisco de Goya. It is a picture that in spite of its small size, attracts<br />

much comment from visitors to The Bowes Museum. We hope that this publication will<br />

increase our visitors’ enjoyment and appreciation of one of the gems in The Bowes Museum’s<br />

picture collection.<br />

Lord Foster of Bishop Auckland<br />

Chairman, Trustees of The Bowes Museum<br />

2<br />

1 Tears of St Peter<br />

Domenikos Theotokopoulos called El Greco<br />

(1541-1614)<br />

c.1580,<br />

Oil on canvas 108 x 89.6cm<br />

The Bowes Museum<br />

2 The Immaculate Conception<br />

José Antolínez (1635-1675)<br />

c.1660<br />

Oil on canvas 167.6 x 163.8cm<br />

The Bowes Museum<br />

3 Tobias Restoring his Father’s Sight<br />

Antonio de Pereda (1611-1678)<br />

1642<br />

Oil on canvas 192 x 157cm<br />

The Bowes Museum<br />

Figures 1, 2 and 3 were amongst those paintings purchased from the collection of the Conde de Quinto by John and Joséphine Bowes in 1862.<br />

Goya’s <strong>Prison</strong> – the Year of Despair

Goya’s <strong>Prison</strong> – the Year of Despair<br />

In 1862 John and Joséphine Bowes made numerous purchases at the<br />

sale of the collection of the Conde de Quinto who had died in 1860.<br />

The Conde de Quinto, politician, courtier, writer and art collector, had<br />

built up a magnificent collection facilitated by his position as Director of<br />

the Museo de la Trinidad in Madrid. The widowed Condesa was living<br />

in Paris, where all of the pictures were housed. The Condesa was in<br />

desperate need of income and sought to sell the collection of paintings<br />

her husband had acquired. Coincidentally, her agent and advisor was<br />

Benjamin Gogué, who was also working in the same capacity for John and<br />

Joséphine Bowes.<br />

The sale of the paintings was to be held at the Condesa’s house in the<br />

Avenue Matignon, and a catalogue was published in June 1862. (Fig. 24)<br />

John Bowes was given an advance copy, with the addition of the prices<br />

the Condesa was asking. Gogué encouraged the Bowes’ to buy liberally.<br />

Ultimately, of the two hundred and seventeen pictures listed in the Conde<br />

de Quinto sale catalogue, Bowes purchased seventy five, all now at The<br />

Bowes Museum, including El Greco’s Tears of St Peter. (Figs.1, 2, 3) 1<br />

Eight works in the sale catalogue were attributed to the hand of<br />

Francisco de Goya (1746-1828) including three purchased by John and<br />

Joséphine Bowes:-<br />

No 44 Portrait of his brother<br />

No 45 Don Juan Antonio Meléndez Valdés<br />

No 48 Interior of a <strong>Prison</strong> 2<br />

3<br />

6 Self portrait in the studio<br />

Francisco de Goya<br />

c.1794-5<br />

Oil on canvas 42 x 28cm<br />

Madrid, Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando<br />

4 Portrait of John Bowes<br />

Jacques Feyen (1815-1908)<br />

1863<br />

Oil on canvas 181 x 190cm<br />

The Bowes Museum<br />

5 Portrait of Joséphine Bowes<br />

Antoine Dury (1819-after 1878)<br />

1850<br />

Oil on canvas 196 x 128cm<br />

The Bowes Museum<br />

7 Entry from the handwritten catalogue of paintings of<br />

The Bowes Museum 1878 listing Interior of a <strong>Prison</strong>.<br />

Goya’s <strong>Prison</strong> – the Year of Despair

Whilst The Bowes purchased works from the<br />

Condesa by Goya and El Greco, it appears that<br />

they did so with some reluctance. Gogué, writing<br />

to John Bowes in July 1862 urged him:<br />

“...I have sold several pictures by these<br />

two masters. Although these two don’t<br />

appeal to you as masters, I think you might<br />

well take one of each of them for your<br />

collection...” 3<br />

John and Joséphine’s response to Gogué proved<br />

to be inspired, as in 1862 neither Goya or El Greco<br />

were to fashionable tastes.<br />

4<br />

Of the Goyas purchased from the collection of the<br />

Conde de Quinto the portrait sketch of an old man<br />

described as the artist’s brother has been largely<br />

discredited by scholars as being by a follower<br />

of Goya. (Fig. 29) Goya’s portrait of Meléndez<br />

Valdés, the poet, lawyer and good friend of the<br />

artist, is regarded as one of a number of portraits<br />

painted by Goya at the end of the 1790s that may<br />

owe debt to late 18th Century English painters,<br />

particularly Gainsborough and Reynolds. (Fig.16)<br />

8 Interior of a <strong>Prison</strong><br />

Francisco de Goya<br />

1793-4<br />

Oil on tinplate 42.9 x 32.7cm<br />

The Bowes Museum<br />

Of the three works Interior of a <strong>Prison</strong>, dated<br />

1793-4, is by far the smallest yet is the most<br />

affecting, the image having the greatest impact<br />

upon the viewer. 4 Under a gloomy archway are<br />

seven prisoners with hands and feet bound<br />

by heavy chains. They are seen in a variety of<br />

postures, some seated or leaning against a wall,<br />

another lying on the ground with his head towards<br />

the spectator. In this small, delicately painted<br />

picture Goya has presented us with a scene<br />

dominated by an atmosphere of utter desolation.<br />

The prison scene was not however, the only<br />

disturbing image in the Goya section of the Conde<br />

de Quinto sale. Also listed was Yard with Lunatics,<br />

a terrifying vision of a madhouse 5 . (Fig.9)<br />

Goya’s <strong>Prison</strong> – the Year of Despair

Goya’s <strong>Prison</strong> – the Year of Despair explores the story<br />

behind these dark images and what compelled Goya<br />

to paint them.<br />

By 1792, Goya, approaching forty-six, had become<br />

bored with painting cartoons for the Royal Tapestry<br />

Factory. (Fig.10) Since 1775 he had painted more than<br />

sixty, full size, colour compositions. Some were huge.<br />

The money was good, but they were only for Royal<br />

consumption, and no wider audience saw them. In<br />

any case, the very nature of translating Goya’s painted<br />

images into large scale tapestry production forced<br />

his technique to limit its expressiveness. Goya’s<br />

career was at a crossroads. Although he had achieved<br />

acclaim and patronage as a painter of portraits, genre<br />

and religious scenes, it appears that he was not where<br />

he wanted to be. His destiny was determined after he<br />

was stricken by an illness that remains a mystery to<br />

this day. Whatever the cause of the illness, the year<br />

that followed marked a turning point in defining the<br />

career of one of Western art’s greatest masters.<br />

In October 1792, just before his illness struck, Goya<br />

had been one of a number of Academicians who<br />

addressed the Royal Academy with ideas for reforms<br />

in the teaching of art. Goya spoke passionately against<br />

the imposition of rules in painting and of a common<br />

curriculum to be forced upon all students. He criticised<br />

those who lauded the perfection of Greek statues as<br />

subject matter above the study of nature. Goya asked<br />

his audience:<br />

“What statue or cast of it might there be that<br />

is not copied from divine nature? As excellent<br />

as the artist may be who copied it, can he not<br />

but proclaim that when placed at its side, one<br />

is the work of God and the other of our own<br />

miserable hands?” 6<br />

Standing at the centre of the cultural elite of Madrid,<br />

Goya’s statement demonstrated his desire for all<br />

artists to enjoy an uninhibited freedom of expression<br />

and unbridled exploration of the imagination.<br />

9 Yard with Lunatics<br />

Francisco de Goya<br />

1793-4<br />

Oil on tinplate 43.5 x 32.4cm<br />

Dallas, Meadows Museum,<br />

Southern Methodist University<br />

5<br />

Goya’s <strong>Prison</strong> – the Year of Despair

6<br />

10 The Picnic<br />

Francisco de Goya<br />

1788<br />

Oil on canvas 41 x 25.8cm<br />

London, The National Gallery<br />

A sketch for one of a series of cartoons for<br />

tapestries ordered by Charles III to decorate<br />

the Bedchamber of the Infantas at the Palace<br />

of El Pardo. The King died in 1788 and the<br />

project was abandoned.<br />

11 Venus presenting Arms to Aeneas<br />

Corrado Giaquinto (1703-1766)<br />

c.1753-62<br />

Oil on canvas 153 x 115cm<br />

The Bowes Museum<br />

The intellectual centre of artistic life in Madrid was the Royal Academy<br />

of San Fernando. The teaching programme was based on the example<br />

of the French Academy. During Goya’s early career it was heavily<br />

influenced by the Bohemian-born artist Anton Raphael Mengs<br />

(1728-1779), who established himself in Madrid from 1761 following<br />

a successful period in Italy, where he had become leader of the<br />

Neoclassical style of painting. Mengs arrived in Madrid at the invitation<br />

of the Spanish King Charles III and, during his terms of office as Court<br />

Painter, he reformed the academic system, encouraging greater<br />

emphasis on classical form and principles. Under Mengs’ influence the<br />

Academy’s library was filled with classical texts, casts after classical<br />

statues and prints of classical buildings.<br />

Although Goya reacted adversely to Mengs’ approach to the teaching<br />

of art, it was nevertheless Mengs he had to thank for his initial break<br />

into the higher echelons of Madrid’s artistic elite. It was on Mengs‘<br />

recommendation that Goya, following his arrival in Madrid in 1775, was<br />

offered work at the Royal Tapestry Factory of Santa Barbara, to which<br />

Mengs had been appointed Director.<br />

Whilst Mengs’ dry, academic Neoclassicism did not appeal to Goya’s<br />

artistic sensibilities, he was more appreciative of the work of two Italian<br />

masters of the Rococo, who, like Mengs, received royal commissions<br />

in Madrid: the Venetian Giovanni Battista Tiepolo and Corrado Giaquinto<br />

from Naples. (Fig.11) Giaquinto was in Madrid between 1753 and 61,<br />

while Tiepolo arrived in 1762 and remained until his death in 1770. (Fig.12)<br />

What Goya absorbed from them as he worked on tapestry commissions<br />

was the Rococo’s exuberant celebration of fantasy and caprice. This<br />

they expressed in the dramatic frescoes and ceiling decorations for<br />

the royal palaces that Goya would have been able to study at first<br />

hand. A century later their work was to appeal to the taste of John<br />

and Joséphine Bowes, who acquired Giaquinto’s Venus Presenting Arms<br />

to Aeneas at the Conde de Quinto’s sale of 1862, and Tiepolo’s The<br />

Harnessing of the Horses of the Sun, which entered the collection by 1877.<br />

Soon after his speech to the Academy, late in 1792, Goya left Madrid,<br />

heading south to Andalusia. He was ill, but none of his medical friends<br />

could identify the cause. All he knew was that he was suffering from<br />

terrible noises in his head, severe dizziness, loss of balance and, for a<br />

while, an inability to walk up or down stairs without feeling nauseous.<br />

His eyesight was failing him and he regularly fainted.<br />

Goya’s <strong>Prison</strong> – the Year of Despair

Whatever the cause, Goya’s unfathomable illness left him profoundly<br />

deaf. Whilst the origins of his ailment have been speculated on at<br />

length – syphilis or meningitis being amongst the two most popular<br />

theories – all that is certain is that, as he approached middle age, Goya<br />

found himself in an isolated, alien world, with his ability to communicate<br />

all but destroyed. What added to the mystery of Goya’s affliction was<br />

the fact that his brother-in-law and colleague at the tapestry factory, the<br />

painter and tapestry designer Ramón Bayeu, fell ill at the same time.<br />

Born in 1746, the same year as Goya, he died in March 1793, as the<br />

latter was beginning to recover.<br />

Goya spent his convalescence at the home of Sebastian Martinez,<br />

a wine exporter based in Cadiz. (Fig.13) Martinez was a self-made<br />

man and one of Spain’s major private art collectors. He owned a large<br />

collection of prints by European artists and was particularly interested<br />

in English painters, all of which Goya was able to absorb during his stay.<br />

This period of study was to influence Goya’s approach to portraiture,<br />

having spent time looking at prints after Romney, Reynolds and<br />

Gainsborough at close hand, as well as engravings after Hogarth.<br />

12 The Harnessing of the Horses of the Sun<br />

Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696-1770)<br />

c.1731<br />

Oil on canvas 98 x 74cm<br />

The Bowes Museum<br />

As a new year dawned, Goya’s school friend from Saragossa, the<br />

wealthy merchant, Martin Zapater, responded to a letter from Martinez<br />

in Cadiz:<br />

7<br />

“Your letter of the fifth of this month has left me as worried<br />

about our friend Goya as the first I received, and since the nature<br />

of his malady is of the most fearful, I am forced to think with<br />

melancholy about his recuperation.” 7<br />

By March 1793, whilst Goya’s overall condition had improved, he<br />

was clearly still unwell. Now able to write to Zapater himself, Goya<br />

exclaimed:<br />

“My dear soul, I can stand on my own feet, but so poorly<br />

that I don’t know if my head is on my shoulders; I have no<br />

appetite or desire to do anything at all.” 8<br />

A few weeks later Martinez updated Zapater on the extent of his<br />

guest’s recovery:<br />

“… our Goya is getting on slowly but there is some improvement<br />

… The noise in his head and his deafness are just the same,<br />

but his sight is much better and he is no longer affected by the<br />

dizziness that made him lose his balance. He is already going<br />

up and down stairs very well and in fact is doing things that he<br />

would not do before.” 9<br />

13 Don Sebastián Martínez y Pérez<br />

Francisco de Goya<br />

1792<br />

Oil on canvas 93 x 67.6cm<br />

New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art<br />

One of his finest portraits Goya depicts<br />

Sebastián Martínez, the patron who supported him<br />

during his months of illness. It is dated 1792 and so<br />

must have been painted just prior to the onset of<br />

Goya’s disease. Martínez sits holding a letter with the<br />

dedicatory inscription: ‘Don Sebastián Martínez,<br />

from his friend Goya.’<br />

Goya’s <strong>Prison</strong> – the Year of Despair

8<br />

14 Sorting the Bulls<br />

Francisco de Goya<br />

1793<br />

Oil on tinplate 42.6 x 32cm<br />

Private Collection<br />

15 The Strolling Players<br />

Francisco de Goya<br />

1793-4<br />

Oil on tinplate 42.5 x 31.7cm<br />

Madrid, Museo del Prado<br />

It was during these months of recuperation that Goya truly began to<br />

explore his individualism that, as an artist, he had advocated for all painters<br />

at the Academy a few months earlier. Whilst at Martinez’s house in Cadiz,<br />

and also following his return to Madrid in the summer, Goya dedicated<br />

himself to producing a set of small paintings which he described as a series<br />

of ‘cabinet’ pictures. 10<br />

The twelve works, all painted on small tin sheets, were to become the<br />

tinplate templates of inspiration and guidance for much of the rest of his<br />

artistic output.<br />

In his series of cabinet pictures Goya allowed himself to produce images<br />

that were of personal interest, rather than working under the obligations<br />

imposed by patrons. The subjects were diverse – six scenes of bulls and<br />

bullfighting, (Fig.14) for which Goya had a passion; a shipwreck, a raging<br />

inferno, a murderous stagecoach hold-up, a travelling theatre, (Fig.15) a<br />

lunatic asylum and the inside of a prison. Goya had painted some of the<br />

subjects previously, but as a group the cabinet pictures were to mark a<br />

transition from the limitations which the tapestry cartoons placed on his<br />

imagination, to a world of dark visions and caprices (‘caprichos’- meaning<br />

imagination, fantasy).<br />

Undoubtedly with that in mind, on the 4th January 1794 Goya wrote to<br />

Bernardo de Iriate, the Academy’s Deputy, to explain his activities during<br />

his illness:<br />

“In order to occupy my imagination …I set myself to painting a<br />

series of cabinet pictures in which I have been able to depict themes<br />

that cannot usually be addressed in commissioned works, where<br />

‘caprichos’ and invention have little part to play. I thought of sending<br />

them to the Academy …” 11 (Fig.19)<br />

Iriate must have responded to Goya’s letter immediately, since the<br />

following day Goya unveiled his new works before the Academy. Two days<br />

later Goya wrote to Iriate once more to thank him and express gratitude for<br />

the favourable reception given to his work by the Academicians and their<br />

sympathetic enquiries about his health. He added that the pictures could<br />

remain in Iriate’s home as long as he wished, and added:<br />

“as well as the final one which I have already begun, which shows<br />

a yard of lunatics, and two naked figures fighting while the keeper<br />

beats them, and others in sacks (it is in a scene I once saw in<br />

Saragossa). 12 I will send it to your Excellency in order to complete<br />

the series.” 13 (Fig. 21)<br />

Goya’s <strong>Prison</strong> – the Year of Despair

Goya’s reference to a “yard of lunatics” refers to the last painting in<br />

the series, now in Dallas, which warrants comparison with Interior of<br />

a <strong>Prison</strong>. These paintings of a madhouse and a prison in the cabinet<br />

series are important in two vital respects. They demonstrate the<br />

interest Goya had in penal reform, which he shared with friends like<br />

Meléndez Valdés, but also suggest Goya’s emotional and mental state<br />

as he sought to come to terms with the illness that had brought him<br />

down so violently and permanently. Looking at both pictures, one<br />

cannot help but speculate as to their symbolism to Goya himself. The<br />

naked, brawling inmates in Yard with Lunatics, themselves surrounded<br />

by chaotic scenes with prisoners in various states of undress, could<br />

easily refer to the months spent in Cadiz with Martinez, where Goya<br />

stricken by constant dizziness and noises in his head, must have<br />

feared for his sanity.<br />

Interior of a <strong>Prison</strong> seems to suggest another fear for a man<br />

who had experienced Goya’s trauma – the fear of utter, desolate<br />

isolation. If one were to search for a work in Western art to<br />

convey the word ‘hopelessness’ then it would be hard to find one<br />

better than Interior of a <strong>Prison</strong>.<br />

Take a moment to absorb the stillness of the scene, which is<br />

oppressive, each prisoner consumed by his own thoughts. The<br />

archway, which offers a glimmer of light, reveals the thickness of<br />

the walls; barriers that act as a metaphor for each of their resigned<br />

despair – they can scream as loudly as they want, but their cries will<br />

never be heard.<br />

Goya has heightened the sense of claustrophobic suffocation by<br />

emphasising the chains and leg and hand irons worn by the prisoners.<br />

The man lying in the foreground is both attached to the wall by a chain<br />

around his neck and to a wooden bench by rings around his legs. In<br />

this position he is physically unable to move, a method of punishment<br />

used in Madrid’s prisons at the time. As one studies the picture, the<br />

eye is constantly drawn to the many shackles and chains worn by<br />

the prisoners, all cleverly emphasised by Goya, who has used white<br />

highlights to enhance our awareness of their restriction.<br />

It is as if both Interior of a <strong>Prison</strong> and Yard with Lunatics represent the<br />

impact of Goya’s stone deafness upon his senses. The insane rantings<br />

of those in the madhouse are symbolic of the noises and voices Goya<br />

could hear for a time inside his head, while the unbearable silence<br />

suggested within the thick walls of the prison indicate Goya’s realisation<br />

of his new relationship with the outside world. Like the shackled men<br />

slumped within the prison walls, he now shares their confinement.<br />

16 Don Juan Antonio Meléndez Valdés<br />

Francisco de Goya<br />

1797<br />

Oil on canvas 73 x 57cm<br />

The Bowes Museum<br />

9<br />

Goya’s <strong>Prison</strong> – the Year of Despair

10<br />

17 Imaginary <strong>Prison</strong>s;<br />

The Man on the Rack<br />

Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778)<br />

c.1749-61<br />

Etching 56.4 x 42cm (plate size)<br />

The Bowes Museum<br />

18 The Rake in Bedlam<br />

The Rake’s Progress Scene 8<br />

William Hogarth (1697-1764)<br />

1735<br />

Etching and engraving 35.5 x 40.5cm<br />

The British Museum<br />

The oppressive archway in Interior of a <strong>Prison</strong> is reminiscent of Giovanni<br />

Battista Piranesi’s Imaginary <strong>Prison</strong>s of 1749-50 and reworked in 1761.<br />

(Fig.17) Goya would have had the opportunity to study Piranesi’s<br />

monumental architectural fantasies whilst he was in Rome in 1770, and<br />

there is even the suggestion that he shared lodgings with Piranesi in the<br />

Via Trinistà dei Monti during his time there. 14<br />

Goya’s images of the Spanish penal system have been compared<br />

with those of Hogarth of the 1730s in his hugely successful series,<br />

The Harlot’s Progress, (painted 1731, engraved 1733) and The Rake’s<br />

Progress (painted 1732, engraved 1735). 15 (Figs.18, 20)<br />

Hogarth’s work was known in Spain, through his volumes of engravings,<br />

and it is likely that Goya would have had opportunity to study both series<br />

as part of the collection of prints belonging to Sebastián Martinez whilst<br />

in Cadiz. 16 Where Goya differs so markedly from the English Master<br />

is that Hogarth offers the viewer a myriad of narrative detail, while<br />

Goya emphasises the desolate bleakness of his subject. In contrasting<br />

Hogarth’s images of Moll Hackabout, a fictional London prostitute in<br />

Bridewell <strong>Prison</strong>, or the wayward Tom Rakewell in Bethlehem Royal<br />

Hospital (Bedlam) with Goya’s Interior of a <strong>Prison</strong>, one can begin to<br />

appreciate how each artist visualised the plight of those who found<br />

themselves at the bottom of society.<br />

In scene four of The Harlot’s Progress, Moll is shown in Bridewell <strong>Prison</strong>,<br />

a house of correction for prostitutes and petty criminals, adorned in<br />

fine clothes within her grim confine. Hogarth uses a number of clever<br />

and witty narratives to emphasise how far Moll has fallen, such as the<br />

fellow female inmate behind her who teasingly strokes the silk and lace<br />

of Moll’s clothing while addressing the viewer with a wink and wry grin.<br />

Then look at Tom in Bedlam, stripped of his fine clothes and thereby<br />

his social pretensions, a sight observed by an aristocratic lady and<br />

her maid, paying customers to the live experience of one of London’s<br />

must-see sights – the lunatic asylum. Meanwhile, loyal Sarah Young,<br />

Tom’s lover whom he had shunned whilst with child in scene one of the<br />

saga, weeps by his side, knowing her former beau’s future is decidedly<br />

bleak. In both images however, whilst depicting the lowest levels of<br />

humanity, there remains some form of social structure. In scene four<br />

from the Harlot, men and women co-exist together; they are clothed<br />

and it is clearly an environment where banter and social interaction were<br />

commonplace. Whilst neither Bridewell nor Bedlam are places any of<br />

19 Letter from Goya to Iriate, dated 4 January 1794,<br />

British Library, London<br />

The letter in which Goya explained his activities during<br />

his recuperation from illness and the production of his<br />

cabinet pictures.<br />

Goya’s <strong>Prison</strong> – the Year of Despair

12<br />

Hogarth’s audience would choose to be themselves, some sense<br />

of humanity exists. In the Rake series, Sarah weeps at Tom’s side.<br />

Amidst the lunacy, she nevertheless displays her sustained love<br />

for him, or, at the very least, feelings of deepest compassion.<br />

Now look at Goya’s inmates in Interior of a <strong>Prison</strong>: all male, and<br />

like Tom, in rags or naked, stripped of any social status that might<br />

once have existed. But there is no interaction between any of<br />

them, only silence, no knowing glances towards the spectator, no<br />

gallows humour. In their resigned wretchedness they no longer<br />

hope to receive any visitors – not even those prison tourists that<br />

paid to gawp at those less fortunate than themselves. These men<br />

are going nowhere and seeing no one. This is it. Nothing. Their<br />

existence is utterly devoid of love or compassion, until, eventually,<br />

they will be released by death.<br />

Hogarth and Goya differ in their approach to the depiction of<br />

prison life principally because Hogarth sought to entertain<br />

whilst Goya did not. Hogarth’s paintings for both the Harlot and<br />

the Rake were translated into print form for a mass audience.<br />

Goya’s cabinet series, as he had informed Iriate in his letter of<br />

4th January 1794, were intended for no one other than himself.<br />

But as he shared this body of new work with the Academicians<br />

of San Fernando, it is likely that Goya was demonstrating to his<br />

colleagues, as he almost certainly was to himself in the months<br />

beforehand, that in spite of his debilitating illness, his mind, his<br />

imagination, his ability for ‘caprice’, remained intact. In fact, not<br />

only had Goya’s mental agility and artistic ability been preserved,<br />

in the months of illness and recuperation he had reached greater<br />

heights than he had previously achieved. Certainly he sought<br />

approval from his fellow Academicians, but his eagerness to show<br />

his cabinet paintings strongly suggests that Goya, previously<br />

searching for a clarity of artistic direction, now knew that he had<br />

found it.<br />

Following his presentation of the cabinet pictures to the Academy,<br />

Goya continued his slow rehabilitation. He summed up his<br />

condition to Zapater in April 1794:<br />

“I am much the same, in so far as my health, some times<br />

raving with a mood that I myself cannot stand, other times,<br />

more tempered, as now when I take up the pen to write<br />

to you, and I am already tired, I can only say that Monday,<br />

God willing, I will go to the bullfight and I would want you<br />

to accompany me.” 17<br />

20 Moll in Bridewell <strong>Prison</strong><br />

The Harlot’s Progress Scene 4<br />

William Hogarth (1697-1764)<br />

1733<br />

Etching and engraving 32 x 38cm<br />

The British Museum<br />

21 Letter from Goya to Iriate, dated 7 January 1794,<br />

British Library, London<br />

Goya’s <strong>Prison</strong> – the Year of Despair

Clearly Goya was striving to get his personal life back to normal, although his<br />

permanent deafness meant that he never would. But by April 1794 Goya, in terms<br />

of his public life as a painter, was entering artistic maturity. Had his mystery illness<br />

killed him Goya would have left a body of work consisting of Rococo-inspired<br />

tapestry designs and genre scenes, portraits and religious imagery, which are likely<br />

to have made his place in Western art an interesting footnote. Goya’s work up to this<br />

point was effective but not extraordinary.<br />

As the 1790s progressed, having asserted with his Royal patrons that he was no<br />

longer able to work on large tapestry designs, Goya was free to concentrate on<br />

more personal subjects in the vein of the cabinet series. Now his individual genius<br />

emerged in works which emphasised the darker side of human nature, such as the<br />

Caprichos prints published in 1799. A series of eighty images, each satirised the<br />

follies of Spanish society, ridiculing human extravagance and vice. (Figs. 22, 27, 28)<br />

Although he had suffered greatly during his months of illness, and was left<br />

permanently deaf, Goya went on to be considered by his countrymen the greatest<br />

artist of his age, epitomised in images such as The Third of May, 1808. (Fig. 23)<br />

Today he is revered worldwide.<br />

14<br />

22 Obsequio á el maestro<br />

(Homage to the Master)<br />

Francisco de Goya<br />

Plate 47 from Los Caprichos<br />

1797-8<br />

Etching and aquatint<br />

21.5 x 14.5cm (plate size)<br />

The Bowes Museum<br />

23 The Third of May, 1808<br />

Francisco de Goya<br />

1814<br />

Oil on canvas 266 x 345cm<br />

Madrid, Museo del Prado<br />

24 Catalogue d’une Riche<br />

Collection de Tableaux de<br />

l’Ecole Espagnole et des<br />

Ecoles d’Italie et de Flandres,<br />

Paris, 1862<br />

An original copy of the<br />

Conde de Quinto catalogue<br />

is in the archive of<br />

The Bowes Museum.<br />

Goya’s <strong>Prison</strong> – the Year of Despair

Goya’s <strong>Prison</strong> – the Year of Despair<br />

15

Reading a Masterpiece<br />

Whilst the subject matter of the cabinet pictures differs<br />

widely in terms of narrative, it is their common physical scale<br />

that unites the paintings as a group. Goya painted each image<br />

on a metal sheet, plated with almost pure tin. The height<br />

of each sheet ranges between 42.5 and 43.5cm whilst the<br />

width of each sheet varies between 31.6 and 32.4cm. He also<br />

prepared each sheet using the same method, which was to<br />

cover the tin with a heavily loaded brush of beige-pink over a<br />

thin red ground. These strong brushmarks are clearly visible<br />

under the thin layers of colour in the pictures. In the darker<br />

pictures in the series, particularly Interior of a <strong>Prison</strong> and Yard<br />

with Lunatics, Goya dragged the thin layers of colour over the<br />

ridged surface of the preparation.<br />

Interior of a <strong>Prison</strong><br />

Francisco de Goya<br />

1793-4<br />

Oil on tinplate<br />

42.9 x 32.7cm<br />

The Bowes Museum<br />

16<br />

Sorting the Bulls (Fig.14 detail)<br />

Six of the cabinet paintings are bull fighting scenes, of<br />

which three take place outside and three inside the bullring.<br />

In this scene, twenty four bulls and oxen are skilfully<br />

positioned at every conceivable angle. Behind them is a<br />

crowd, controlled by mounted guards, who have come on<br />

foot or carriage to see the bulls.<br />

The Strolling Players (Fig.15 detail)<br />

In composing this cabinet picture Goya freely<br />

sketched in pencil on the prepared surface, a<br />

technique he had employed introducing sketches for<br />

tapestry designs. The scene itself is closely related to<br />

the subject matter of some of Goya’s tapestry designs.<br />

Goya’s <strong>Prison</strong> – the Year of Despair

Goya’s <strong>Prison</strong> – the Year of Despair<br />

17

Exhibited<br />

Madrid, Liceo Artistico y Literario, 1846 (50, lent by the Conde de Quinto);<br />

London, Guildhall, Spanish Exhibition, 1901 (60);<br />

London, Grafton Galleries, 1913-4 (178);<br />

London, National Gallery, Long Loan, 1920-27;<br />

Leeds, Masterpieces from the Collections of Yorkshire and Durham, 1936 (36);<br />

London, National Gallery, Spanish Painting, 1947 (10);<br />

New York, Wildenstein, Goya, 1950 (38);<br />

London, Agnew, Pictures from The Bowes Museum, 1952 (11);<br />

London, Tate Gallery, Council of Europe exhibition, The Romantic Movement, 1959 (11);<br />

London, Arts Council, Some Paintings from The Bowes Museum, 1959 (44);<br />

London, Arts Council, Paintings from The Bowes Museum, 1962 (50);<br />

Paris, Musée Jacquemart-André, Goya, 1961-2 (57);<br />

London, Royal Academy, Goya and his Times, 1963-4 (102);<br />

18<br />

Barnard Castle, The Bowes Museum , Four Centuries of Spanish Painting, 1967 (85);<br />

Bordeaux, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Paris, Grand Palais, Madrid, Prado, L’Art Européen à la Cour d’Espagne au XVIII siècle,<br />

1979-80 p.73 (24);<br />

London, National Gallery, El Greco to Goya, 1981 (73);<br />

Madrid, Prado, Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, New York, Metropolitan Museum, Goya and the Spirit of Enlightenment,<br />

1989 (71);<br />

London, National Gallery, European Paintings from The Bowes Museum, 1993 (p.33)<br />

Madrid, Prado, London, Royal Academy, Chicago, Art Institute, Goya, Truth and Fantasy, The Small Paintings, 1993-4 (42);<br />

Cologne, Wallraf-Richartz Museum, Zurich, Kunsthaus, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Das Capriccio als Kunstprinzip,<br />

1996-7 (30);<br />

Philadelphia, Museum of Art, Lille, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Goya, Another Look, 1999 (25);<br />

Copenhagen, Statens Museum for Kunst, Goya’s Realisme, 2000 (32 );<br />

Berlin, National Galerie, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Madrid, Prado, Goya, Prophet der Moderne, 2005-6 (31);<br />

Madrid, Prado, Goya in Times of War, 2008 (3);<br />

Edinburgh, National Galleries of Scotland, The Discovery of Spain, 2009 (p.45, pl.29, p.152).<br />

Goya’s <strong>Prison</strong> – the Year of Despair

Literature<br />

A.L.Mayer in Zeitschrift für bildender Kunst, New Series,<br />

XXIII, 1911-12, p.104;<br />

A. de Beruete y Moret, Goya, Composiciones y Figuras,<br />

1917, p.94, pl.36;<br />

V. von Loga, Goya, 1921, p.209, no.433;<br />

A.L.Mayer, Goya, 1924, p.174, no.544;<br />

Sir P. Hendy, Spanish Painting, 1946, p.28;<br />

A.L.Mayer, Historia de la Pintura Española, 1947, pl.531;<br />

X. Desparmet Fitz-Gerald, L’oeuvre peinte de Goya, 1928-<br />

50, Vol.I, no.207, pl.162;<br />

T.Wake in A.Blunt & M.Whinney, The Nation’s Pictures,<br />

1950, p.156, pl.37a;<br />

E.Harris in Burlington Magazine, XCV (1953), pp.22, 23;<br />

J.A.Gaya Nuño, La pintura espagñola fuera de España,<br />

1958, p.169, no.999;<br />

J.Mayne in L’Oeil, no.55/56 (1959), p.17, repr.;<br />

M.S.Soria in Connoisseur, Aug.1961, pp.30-37;<br />

J.Gàllego, Goya, Revista de Arte, no.54 (1963), p.369;<br />

E.Young in Apollo, LXXXV (1967), p.457, fig.16;<br />

E. Harris, 1969, no.35;<br />

E.Young, The Bowes Museum, Catalogue of Spanish and<br />

Italian Paintings, 1970, pp.37-38, pl.8;<br />

J.Gudiol, Goya, 1971, p.299, no.470, fig.755 (1st ed.<br />

Barcelona 1970);<br />

P.Gassier & J. Wilson, Goya: his life and work, 1971, p.264,<br />

no. 929 (1st ed. Paris 1970);<br />

E. Young in Burlington Magazine, CXIV ( 1973), p.45;<br />

P.Gassier, The Drawings of Goya: the complete albums,<br />

1973, p.221;<br />

R. de Angelis, L’opera pittorica di Goya, 1974, p.125,<br />

no.532;<br />

S. Symmons, Goya, 1977, no.45;<br />

X. de Salas, Goya, 1979, p.183, no.271;<br />

P. Gassier, Goya, Das Gesamtwerk, 1980, Vol. II, p.50,<br />

no.517;<br />

P. Gassier in L’Oeil, no.136 (1981), p.80;<br />

J. Baticle & C.Marinas, La Galerie Espagnole de Louis-<br />

Philippe au Louvre, 1981, p.83, under no.102;<br />

G. von Gehrer in Weltkunst, 1981, p.1324;<br />

D.Sutton in Apollo, Oct.1981, p.126;<br />

Prado, Madrid,Goya en las colecciones madrilènes,1983,<br />

pp.162-3;<br />

E.Young, Catalogue of Spanish Paintings in The Bowes<br />

Museum, 2 ed.rev. 1988, pp.78-9;<br />

M. Águeda Villar in Cinco siglos de arte en Madrid (XV-XX),<br />

III, Jornalas de Arte, 10-12.12.1986, 1991, pp.171-4;<br />

M.B.Mena Marqués in Historias mortales. La vida<br />

cotidiana en el arte, 2004, p.257;<br />

N. Glendinning in Burlington Magazine, Feb. 1994, p.100;<br />

J. Tomlinson, Francisco Goya y Lucientes, 1746-1828,<br />

1994, p.202, fig.203;<br />

J.L. Morales y Marin, Goya, A Catalogue of his Paintings,<br />

1994 (English edition 1997), no.437;<br />

J.Wilson-Bareau, Truth and Fantasy, the small paintings,<br />

1994, pp.200-3;<br />

L.Domergue in Congreso Internacional “Goya 250 años<br />

despues, 1746-1996”, Marbella, 10-13.4.1996, 1996,<br />

pp.97-99;<br />

S. Dubosc, La peinture espagnole dans la collection Quinto,<br />

Ph.D. thesis, Paris, Sorbonne, 1997.<br />

Provenance<br />

Léonard Chopinot, Madrid, before 1800?; Angela Sulpice<br />

Chopinot (before 1805); Augustin Quinto?; Conde de<br />

Quinto, before 1846; Condesa de Quinto, her sale<br />

catalogue, June 1862 (48); purchased Dessenon,<br />

18-19 Feb. 1864 (200f) for John Bowes. [see above, under<br />

exhibitions: Philadelphia, Lille, 1999 (25)]<br />

(According to Desparmet Fitz-Gerald (op.cit.), from the<br />

collection of Francisco Azebal y Arriatia of Madrid. Later in<br />

the collection of the Conde de Quinto; Condesa de Quinto<br />

sale catalogue, June 1862, no.45.)<br />

19<br />

Goya’s <strong>Prison</strong> – the Year of Despair

Reading a Masterpiece<br />

This warm and intimate picture is one of a group of portraits<br />

produced by Goya in the late 1790s that demonstrate his<br />

greatness as a portraitist. It also suggests the friendship<br />

that existed between Goya and his sitter who moved in the<br />

same liberal, intellectual circles of enlightened men known as<br />

‘ilustrados’. Meléndez Valdés was eight years Goya’s junior.<br />

He may well have met the artist at Saragossa in 1790 when he<br />

was a judge there. The portrait was possibly painted in the late<br />

spring or summer of 1797, when Meléndez was disappointed<br />

to not secure the post of Public Prosecutor in April that year.<br />

It would certainly explain the melancholic expression on his<br />

face. However, 1797 was also an important year for Meléndez<br />

Valdés, since the publication of the first important collected<br />

editions of his poems came out in April, while he was<br />

appointed Prosecutor to the Municipal authorities in Madrid<br />

in October. Meléndez Valdés was a passionate advocate of<br />

reform of the condition of Spain’s prisons and hospitals.<br />

Don Juan Antonio Meléndez Valdés<br />

Francisco de Goya<br />

1797<br />

Oil on canvas<br />

73 x 57cm<br />

The Bowes Museum<br />

Signed: (on the bottom of the picture):<br />

A Meléndez Valdés su amigo Goya 1797<br />

20<br />

Meléndez Valdés’ friend, the poet Quintana, described<br />

him as ‘of little more than medium height, pale and blond,<br />

frank of feature, strong of limb, with a robust and healthy<br />

complexion’. 18 Goya portrays Meléndez Valdés with an<br />

expression that is both spontaneous and unguarded, if<br />

a little pensive, emphasised by the background which is<br />

devoid of any distracting feature. At the base of the painting,<br />

impressionistically brushed over a green background, Goya<br />

has inscribed, ‘A Meléndez Valdés su amigo Goya 1797.’ –<br />

‘To Meléndez Valdés (‘from’ or ‘by’) his friend Goya 1797.’<br />

His admiration for the French thinkers of the Age of Reason<br />

prompted Meléndez Valdés to cooperate with the regime<br />

of Joseph Bonaparte, who in 1808 was put on the Spanish<br />

throne by his brother Napoleon. Meléndez Valdés believed<br />

that French influence would bring about reforms essential for<br />

the good of Spain. Unfortunately for him, when the Spanish<br />

monarchy was restored in 1814 he was accused of having<br />

been a collaborator and was forced to leave Spain. He left,<br />

travelling in exile in Montpellier in France, where he died<br />

in poverty three years later. There are two replicas of this<br />

painting, one at the Banco Español de Crédito, Madrid, and the<br />

other in a private collection in Madrid.<br />

25 Gaspar de Jovellanos<br />

Francisco de Goya<br />

1797-98<br />

Oil on canvas 205 x 123cm<br />

Madrid, Museo del Prado<br />

Jovellanos, both statesman and writer, was another of<br />

Goya’s circle of ‘ilustrados’ that the artist vividly captured<br />

on canvas in the late 1790s.<br />

Goya’s <strong>Prison</strong> – the Year of Despair

Goya’s <strong>Prison</strong> – the Year of Despair<br />

21

Exhibited<br />

Madrid, Liceo Artistico y Literario, 1846 (8, lent by the Conde de Quinto);<br />

London, Art Gallery of the Corporation [Guildhall?], Spanish Old Masters,1913-14 (179);<br />

London, Burlington Fine Art Club, Spanish Art, 1928 (19a);<br />

Leeds, City Art Gallery, Masterpieces from the Collections of Yorkshire<br />

and Durham, 1936 (35); London, National Gallery, Spanish Paintings, 1947 (5);<br />

London, Agnew, Pictures from The Bowes Museum, 1952 (13);<br />

London, Royal Academy, European Masters of the Eighteenth Century, 1954-5 (356);<br />

London, Arts Council of Great Britain, Some Paintings from The Bowes Museum, 1959 (43);<br />

Paris, Musée Jacquemart-André, Goya, 1961-2 (50);<br />

London, Arts Council, Paintings from The Bowes Museum, 1962 (49);<br />

London, Royal Academy, Goya and his Times, 1963-4 (78);<br />

Barnard Castle, The Bowes Museum, Four Centuries of Spanish Painting, 1967 (84);<br />

Paris, Orangerie des Tuileries, Goya, 1970 (17);<br />

London, Arts Council at The Royal Academy, The Age of Neo-Classicism, 1972 (114);<br />

22<br />

London, National Gallery, El Greco to Goya, 1981 (68);<br />

Madrid, Prado, Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, New York, Metropolitan Museum, Goya and the Spirit of Enlightenment,<br />

1989 (24);<br />

Madrid, Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, London, Royal Academy, Goya, the decade of the Caprichos,<br />

Portraits 1792-1804, 1992 (40);<br />

London, National Gallery, European Paintings from The Bowes Museum, 1993, p.33-4;<br />

London, Royal Academy, Art Treasures of England, the regional collections, 1998 (329);<br />

Madrid, Palacio Real, Enlightenment and Liberalism 1788-1814, 2008-9, p.64, p.466, no.20, p.300.<br />

Goya’s <strong>Prison</strong> – the Year of Despair

Literature<br />

F. Zapater y Gómez, Apuntes Históricos, 1863, p.39;<br />

Conde de la Viñaza, Goya, 1887, no.54;<br />

Z.Araujo Sánchez, Goya, 1889, no.254;<br />

P.Lafond, Goya, 1903, no.163;<br />

V. von Loga, Goya, 1903, p.199, no.275;<br />

A.L.Mayer in Zeitshrift für Bildende Kunst, new series XXIII, 1911-12, p.104, fig.12;<br />

A.L.Mayer, Geschichte der Spanischen Malerei, 1913, Vol.II, p.267;<br />

A. de Beruete y Moret in Revue de l’Art, Vol.XXXV, 1914, p.75;<br />

A. de Beruete y Moret, Goya Pintor de Retratos, 1916, p.175, no.131, p.68, pl.23;<br />

V. von Loga, Goya, 1921, p.198, no.275;<br />

A. de Beruete y Moret, Goya as Portrait Painter, 1922, p.208, no.138, p.86, p.XXV;<br />

A.L.Mayer, Geschichte der Spanischen Malerei, 1922, p.493;<br />

A.L.Mayer, Francisco de Goya, 1923, p.196, no.345;<br />

X. Desparmet Fitz-Gerald, L’Oeuvre Peint de Goya, 1928-50, text vol.II, no.378, pl.vol.II, no.301;<br />

A.L.Mayer, Geschichte der Spanischen Malerei, 1947, p.527;<br />

T.Wake in A.Blunt & M.Whinney, The Nation’s Pictures, 1950, p.156;<br />

F.J.Sánchez Cantón, Vida y Obras de Goya, 1951, pp.62, 169;<br />

E.Harris in Burlington Magazine, Vol.XCV (1953), p.22, 23;<br />

E. du Gué Trapier, Goya, a Study of his Portraits, 1797-99, 1955, p.11, fig.13;<br />

J.A.Gaya Nuño, La Pintura Espanola fuera de Espana, 1958, p.78, 165, no.951;<br />

F.J.Sánchez Cantón, Life and Work of Goya, 1964, p.158;<br />

G. Demerson, Don Juan Meléndez Valdés et son Temps, 1962, p.205-6;<br />

E. du Gué Trapier, Goya and his Sitters, 1964, p.12;<br />

E. Young, The Bowes Museum, Catalogue of Spanish and Italian Paintings, 1970, p.35, no.26, pls.9, 46;<br />

P.Gassier & J.Wilson, Goya: His Life and Work, 1971, pp.135, 164, 188, no.670 (1st edition, Paris, 1970);<br />

J.Gudiol, Goya, 1971, Vol.I, p.281, under no.372 (1st edition, Barcelona, 1970);<br />

E.Young in Burlington Magazine, CXIV ( 1973), p.45;<br />

R. de Angelis, L’opera pittorica di Goya, 1974, p.109, no.313;<br />

S. Symmons, Goya, 1977, no.18<br />

J. Baticle in Actas del XXIII Congreso de Historia del Arte, Granada, 1978, p.25;<br />

E.Young, 1978, no.14;<br />

X. de Salas, Goya, 1979, p.184, no.279;<br />

P. Gassier, Goya, das Gesamtwerk, 2 vols, 1980, Vol.I, p.90, no.304;<br />

G. van Gehrer in Weltkunst, 1981, p.1324;<br />

Prado, Madrid, Goya en las colecciones madrilénes, 1983, pp.162-3;<br />

E.Young, Catalogue of Spanish Paintings in The Bowes Museum, 2 ed. rev., 1988, pp.74-77;<br />

S.Dubosc, La peinture espagnole dans la collection Quinto, Ph.D. thesis, Sorbonne, Paris,1997.<br />

Provenance<br />

Conde de Quinto 1846; Condesa de Quinto, her sale catalogue, June 1862 (46); purchased Gogué(?) for John Bowes.<br />

23<br />

Goya’s <strong>Prison</strong> – the Year of Despair

Reading a Masterpiece<br />

Obsequio á el Maestro<br />

(Homage to the Master)<br />

Francisco de Goya<br />

Plate 47 from Los Caprichos<br />

1797-8<br />

Etching and aquatint<br />

21.5 x 14.5cm (plate size)<br />

The Bowes Museum<br />

24<br />

Goya’s <strong>Prison</strong> – the Year of Despair

Obsequio á el Maestro is Plate 47 of Los Caprichos, a set<br />

of eighty prints executed by Goya in 1797 and 1798. The<br />

series, published in 1799 was the outcome of Goya’s intense<br />

exploration of his imagination, as opposed to seeking physical<br />

truth. This in itself was not new, although other artists who had<br />

inquired into the concept of ‘flight of fancy’ had usually applied<br />

it to creating architectural fantasies, such as the monumental<br />

Roman ruins (caprices) of French artist Hubert Robert. (Fig.26)<br />

Goya was certainly aware too of the light hearted capricci of<br />

Tiepolo, through the Italian’s presence at the Spanish court,<br />

and several prints from Piranesi’s series of imaginary prisons<br />

were in Goya’s own collection. What was new was that<br />

Goya chose to use the concept of capricho to expose the<br />

foolishness he saw in Spanish society at that time. Highlighting<br />

the universal follies of humanity, the series contains various<br />

grotesque caricatures of humanity.<br />

Obsequio á el Maestro pictures a group of witches surrounding<br />

a senior witch on the right; one witch offers to her master an<br />

undersized dead baby. The women present the baby to their<br />

teacher, from whom they have learnt everything. Like many<br />

plates of the Caprichos series, the image is dark and holds<br />

suggestions of evil; the hunched figures look goblin like and<br />

tormented.<br />

The image of kneeling figures draws parallel to the clergy;<br />

Goya appears to compare the witch with a grovelling postulant<br />

kissing a cardinal’s ring. He seems to suggest that witches<br />

and friars are one and the same and that there are definite<br />

likenesses between witchcraft and the activities of the clergy.<br />

It is worth noting that while Goya and his wife Josefa had<br />

seven children, only the seventh of these survived infancy.<br />

There is no doubt that Goya must have been deeply affected<br />

by this; perhaps the dead baby in this image reflects his loss.<br />

Provenance<br />

Harris 82, fifth edition, 1881-6. Purchased by The Bowes<br />

Museum from a private collection 2004.<br />

26 Architectural capriccio with obelisk<br />

Hubert Robert (1733-1808)<br />

1768<br />

Oil on canvas 106 x 139cm<br />

The Bowes Museum<br />

27 Trágala, perro<br />

(Swallow it, dog)<br />

Francisco de Goya<br />

Plate 58 from Los Caprichos<br />

1797-8<br />

Etching and aquatint<br />

21 x 15cm (plate size)<br />

Trágala, perro (Swallow it, dog) was another attack on the<br />

Spanish clergy. A man kneels on the ground in terror, begging<br />

for mercy from a monk clutching a huge enema syringe.<br />

Around him are cackling caricatures, who await in anticipation the<br />

thrust of the syringe into the desperate man’s belly, in an attempt<br />

to flush out his orthodox beliefs.<br />

25<br />

Goya’s <strong>Prison</strong> – the Year of Despair

26<br />

Goya’s <strong>Prison</strong> – the Year of Despair

Select Bibliography<br />

Bowes Museum (Eric Young), Catalogue of Spanish and Italian Paintings, 1970.<br />

Bowes Museum (Eric Young, Elizabeth Conran) Catalogue of Spanish Paintings, second edition, 1988.<br />

Hallet, Mark and Riding, Christine, Hogarth, Tate Publishing, 2006.<br />

Hardy, Charles E. John Bowes and The Bowes Museum, 1970, reprinted 2009.<br />

Hughes, Robert, Goya, London, 2003.<br />

Goya – Truth and Fantasy, The Small Paintings (exhibition catalogue), Madrid, London, Chicago, Yale University Press,<br />

1994 (Juliet Wilson-Bareau, Manuela B. Mena Marqués).<br />

Symmons, Sarah, Goya, London, 1988.<br />

Tomlinson, Janis, Francisco Goya y Lucientes, 1746-1828, London, 1994.<br />

27<br />

28 Miren que grabes! (detail)<br />

(Look how solemn they are!)<br />

Francisco de Goya<br />

Plate 63 from Los Caprichos<br />

1799<br />

Etching<br />

21 x 15cm (plate size)<br />

Goya’s <strong>Prison</strong> – the Year of Despair

Chronology<br />

28<br />

1746 30 March, Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes born at Fuendetodos, a small village 40km south west of<br />

Saragossa. Goya was one of five children of a master gilder. His mother was of aristocratic descent.<br />

1750s Educated in Saragossa at a Roman Catholic monastic order, Goya then became an apprentice of religious painter,<br />

José Luzán y Martínez.<br />

1761 Anton Raphael Mengs arrives in Madrid as Court Painter, followed by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo in 1762.<br />

1770 Tiepolo dies in Madrid. Goya travels to Italy where he studies the great masters.<br />

1771 25 July. Goya marries Maria Josefa, sister of painters Francisco and Ramón Bayeu.<br />

1775 Goya leaves Saragossa for Madrid with his family, to work under Mengs and Francisco Bayeu as a painter of<br />

cartoons for the Royal Tapestry Factory of Santa Barbara. Goya and Ramón Bayeu painted cartoons; full scale<br />

models for tapestries.<br />

1780 Goya elected to the Royal Academy of San Fernando, Madrid, after submitting his painting Christ on the Cross.<br />

1784 Birth of Goya’s seventh child, Francisco Javier Pedro, the artist’s only child to survive infancy.<br />

1785 Appointed Assistant Director of Painting at the Academy of San Fernando.<br />

1786 Appointed painter to the King, as was his brother-in-law Ramón Bayeu, although Goya continued to paint<br />

cartoons for the tapestry factory.<br />

1788 Working on sketches for tapestry cartoons. Carlos III dies in December. Carlos IV nominates Goya as Court<br />

Painter; he executes Royal portraits. From this point Goya establishes himself as the leading painter in Spain.<br />

1792 14 October. Goya’s report to the Academy on the teaching of art. At some point at the end of 1792 Goya leaves<br />

Madrid due to serious illness.<br />

1793 Goya residing with wine merchant and close friend Sebastian Martinez in Cadiz, where he encountered British<br />

portraiture by artists such as Reynolds, Hogarth and Ramsay.<br />

By June Goya leaves Cadiz heading for Madrid.<br />

11 July Goya attends a meeting of the Royal Academy of San Fernando.<br />

12 July – December. Nothing is known of Goya’s precise activities.<br />

1794 4 January. Goya writes to Bernardo de Iriate, the Academy’s Deputy, informing him of his series of cabinet<br />

paintings. His small paintings executed on tin show an interest in painting reality and its darker sides. Although<br />

not his established style, on 5 January Goya unveils the series before the Academicians to favourable response.<br />

Goya meets the Duchess of Alba for the first time.<br />

1796 Goya spends much of the year in Andalusia and visits the Duchess of Alba at her estate in Sanlúcar de<br />

Barrameda. During the summer he executed the Sanlúcar album, which depicted the Duchess and her servants<br />

during everyday life. Some scenes are almost erotic.<br />

1797 Working on the sueños prints and drawings that develop into Los Caprichos, published in 1799. These dream<br />

inspired drawings include themes of witchcraft. During this year Goya painted Meléndez Valdés as well as other<br />

portraits and a number of self portraits.<br />

Goya’s <strong>Prison</strong> – the Year of Despair

1799 Goya was appointed First Court Painter and during this year painted two equestrian portraits of the King and<br />

his wife.<br />

1802 The Duchess of Alba dies.<br />

1803 Goya presents the plates of Los Caprichos to the King. ‘Capricho’ means imagination, fantasy; the series is based<br />

on Goya’s own thoughts and observations.<br />

1806 Birth of Pio Mariano, Goya’s only grandson.<br />

1808 French troops in Spain. Spanish Royal family relinquishes the crown to Napoleon, who puts his brother Joseph<br />

Bonaparte on the throne.<br />

2 May. Madrid uprising against the French, followed by executions of 3 May. Start of the War of Independence.<br />

1810 Goya begins The Disasters of War, the narrative series of etchings. Falling into three distinct parts, the series<br />

depicts: war scenes with rebellion of the Spanish against the French; the great famine in Madrid; and the period<br />

after the war – the new regime. Goya did not publish the series due to censorship.<br />

1812 Goya’s wife Josefa dies.<br />

1813 Defeat of the French by British advance led by the Duke of Wellington. Goya painted an equestrian portrait of<br />

Wellington for public exhibiton at the Royal Academy.<br />

1814 Ferdinand VII restored to power. Goya petitions Regency for funding to paint the heroic scenes of The Second of<br />

May 1808 and The Third of May 1808 (Prado, Madrid).<br />

1815 Inquisition threatens to summon Goya on account of his ‘obscene’ painting The Naked Major c.1800. Goya is<br />

working increasingly for himself only. Depicting the dark side of society, his themes include irrational behaviour,<br />

prison scenes, rape, torture and murder.<br />

1820 Begins the Black Paintings on the walls of his house, Quinta del Sordo, on the outskirts of Madrid. Goya dealt<br />

with biblical and mythological scenes with witches as well as everyday scenes.<br />

1824 Goya travels to Bordeaux and Paris. Returns to Bordeaux where he sets up home with Doña Leocadia Zorilla and<br />

her daughter (possibly his child).<br />

Continues to paint, draw and produce lithographs. He painted a series of miniatures in a similar style to the<br />

Black Paintings.<br />

1826 Visits Madrid to ask to be retired from his post of First Court Painter. He is granted a full pension. During his final<br />

years Goya concentrates mainly on drawing and etching.<br />

1827 Final visit to Madrid during the summer.<br />

1828 16 April. Dies and is buried in Bordeaux. His remains were transferred to Madrid and interred in San Antonio de la<br />

Florida in 1929.<br />

29<br />

Goya’s <strong>Prison</strong> – the Year of Despair

Notes<br />

1<br />

For a fuller discussion of the Conde de Quinto and the Spanish paintings at The Bowes Museum see Eric Young, Catalogue of Spanish Paintings<br />

in the Bowes Museum, second edition, 1988, introduction by Elizabeth Conran, pp.1 - 6. This catalogue also transcribes in full, letters from<br />

Benjamin Gogué to John Bowes, pp. 7 -29. See also, Enriqueta Harris, Spanish Pictures from the Bowes Museum in Burlington Magazine, Vol 95,<br />

No 598 (Jan, 1953), pp22-25.<br />

2<br />

Catalogue d’une Riche Collection de Tableaux de l’Ecole Espagnole et des Ecoles d’Italie et de Flandres, Paris, 1862. An original copy of the<br />

catalogue is in the archive of The Bowes Museum.<br />

3<br />

Letter from Benjamin Gogué to John Bowes, July 1862, archive of The Bowes Museum, quoted in Young and Conran, 1988, p.4.<br />

4<br />

Interior of a <strong>Prison</strong> has been dated to later in Goya’s career by some art historians although examination of the structure of the painting has<br />

confirmed that it was part of the cabinet series of 1793-4. For a fuller discussion see Young, 1988, pp.80-81, and Goya – Truth and Fantasy, the<br />

Small Paintings (exhibition catalogue), Madrid, London, Chicago, Yale University Press, 1994 (Juliet Wilson-Bareau, Manuela B. Mena Marqués)<br />

pp. 200-201.<br />

5<br />

Yard with Lunatics is listed immediately below Interior of a <strong>Prison</strong> in the Conde de Quinto sale catalogue, No 49 Intérieur d’une maison de fous.<br />

6<br />

Goya’s address to the Royal Academy of San Fernando, Madrid, regarding the Method of Teaching the Visual Arts, 1792, quoted in Janis<br />

Tomlinson, Francisco Goya y Lucientes, 1746-1828, London, 1994, pp.306-307.<br />

7<br />

Valentin de Sambricio, Tapices de Goya, Madrid, 1946, doc. no. 159. Quoted in Tomlinson, 1994, p.93.<br />

8<br />

Francisco de Goya, MS letters to Martin Zapater 1774-99. Collection of the Prado, Madrid. Published as Cartes a Martin Zapater, Ed. Xavier de<br />

Salas and Mercedes Agueda, Madrid, 1982, p.211. Quoted in Robert Hughes, Goya, London, 2003, p.127.<br />

9<br />

Quoted from Truth and Fantasy, 1994, p.189.<br />

10<br />

The concept of ‘cabinet’ pictures originated from the Dutch and Flemish tradition of the study of small pictures in modest sized rooms or ‘cabinets’.<br />

30<br />

11<br />

Letter from Goya to Iriate, 4th January 1794, British Library, quoted from Truth and Fantasy, 1994, pp.189-90.<br />

12<br />

Goya’s statement “…it is a scene I once saw in Saragossa…”, probably relates to the large asylum in his native city. There is evidence that two of<br />

Goya’s relatives, an aunt and uncle, Francisca and Francisco Lucientes, were inmates of the Saragossa asylum in 1762 and 1764. It is possible that<br />

Goya visited them. See Peter K. Klein, ‘Insanity and Sublime: Aesthestics and Theories of Mental Illness in Goya’s Yard with Lunatics and Related<br />

Works’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. 61, 1998, pp.198-252.<br />

13<br />

Letter from Goya to Iriate, 7th January 1794, British Library, quoted from Truth and Fantasy, 1994, p.200.<br />

14<br />

See Hughes, 2003, p.36, who cites Jeannine Baticle, L’activisté de Goya entre 1796 et 1806 vue á travers le Diario de Moratin, in Revue d’Art, 13,<br />

1971, p.47.<br />

15<br />

For a full discussion, see J. E. Kromm, Goya and the Asylum at Saragossa, The Society for the Social History of Medicine, 1988, pp.79-89.<br />

Kromm compares Hogarth’s asylum and prison scenes with Goya’s Yard with Lunatics.<br />

16<br />

For a full discussion of the popularity of English satirical prints in Spain see, Reva Wolf, Goya and the Satirical Print in England and on the<br />

Continent, 1730 – 1850, Boston, 1991. For specific reference to Hogarth in the collection of Sebastian Martinez see p.5. Wolf, p.9, also makes<br />

reference to Goya’s friend, the playwright Leandro Fernández de Moratin, who spent a year in England during 1792 and 1793 and in his travel notes<br />

commented on the number of shops in London selling prints and caricatures. It is therefore probable that Moratin was another source from which<br />

Goya could have had access to the English print masters of his day around the time he produced the cabinet pictures.<br />

17<br />

Salas and Agueda, 1982, pp.211, 218. Quoted in Tomlinson, 1994, p.94.<br />

18<br />

Manuel José Quintana, Obras completas, Madrid, 1852, p.120, Biblioteca de autores espanoles, v.19. Cited in Elizabeth du Gué Trapier,<br />

Goya: A Study of his Portraits 1797-99, The Hispanic Society of America, New York, 1955, p.11.<br />

Goya’s <strong>Prison</strong> – the Year of Despair

Acknowledgements<br />

The idea to look closely at Goya’s Interior of a <strong>Prison</strong> has been encouraged by the most intense period<br />

of building redevelopment since the Museum opened in 1892. This period of work which began in<br />

August 2008 will be completed by the early summer of 2010. In this time we will have fully restored the<br />

complicated and previously leaking roof, and created a number of new facilities and galleries on each<br />

floor of the building. During this period we have kept the Museum open, juggling the needs of<br />

the collections, with those of the visitors, contractors and staff, which have all occupied the site at the<br />

same time.<br />

Before the work began we recognised that this was not going to be a time where we could implement<br />

large, multi-loan exhibitions, since scaffolding, cement and dust don’t mix well with objects from other<br />

institutions. Understandably, lenders are anxious about lending precious objects to a building site. As a<br />

consequence, we have taken the opportunity to study more closely important artists in the collection,<br />

on this occasion, Goya.<br />

In studying Interior of a <strong>Prison</strong> I have got to know Goya a little better than I did before, and have been<br />

assisted in this by some of my colleagues who have been extremely generous with their time. Howard<br />

Coutts, Sheila Dixon, Emma House and Viv Vallack all read and commented on the draft, while Laura<br />

Layfield carried out some additional research for the main text and the catalogue entries. I would also like<br />

to thank Elizabeth Conran, formerly curator of The Bowes Museum, who made some suggestions which<br />

have also improved the story that this publication seeks to tell.<br />

Finally, I would like to acknowledge each and every member of staff at The Bowes Museum. Throughout<br />

all the building redevelopment they have maintained their spirit and enthusiasm, in spite of the upheaval it<br />

has necessitated: the outcome of which is a magnificent 19th century building with facilities appropriate<br />

to the 21st century.<br />

31<br />

Adrian Jenkins<br />

Director,<br />

October 2009<br />

29 Portrait of a Man<br />

Formerly attributed to Francisco de Goya<br />

Oil on canvas<br />

43.5 x 38.1cm<br />

The Bowes Museum<br />

This picture sold at the sale of the Conde de<br />

Quinto in 1862 was believed at the time to<br />

be a portrait by Goya of his brother.<br />

Goya’s <strong>Prison</strong> – the Year of Despair

32<br />

Goya’s <strong>Prison</strong> – the Year of Despair