Commission-companion-full

Commission-companion-full

Commission-companion-full

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

COMPANION TO THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION<br />

Contents<br />

Introduction 4<br />

Profiles of vice-presidents 17-23<br />

<strong>Commission</strong> departments 6<br />

Jean-Claude Juncker 8-9<br />

Role of the vice-presidents 10<br />

Project teams 11<br />

Frans Timmermans 12<br />

Deregulation 13<br />

Federica Mogherini 14<br />

Foreign policy 15 & 16<br />

<strong>Commission</strong> work 24-26<br />

programme<br />

Profiles of commissioners 27-53<br />

Team Juncker: the <strong>full</strong> list 34-35<br />

Secretariat-general 42<br />

Gender balance 54<br />

Useful links and locations 55<br />

Pay grades and salaries 56-57<br />

Writers Paul Dallison | Andrew Gardner | Nicholas Hirst | Dave Keating | Tim King | Cynthia Kroet | James Panichi |<br />

Simon Taylor<br />

Design Paul Dallison | Jeanette Minns<br />

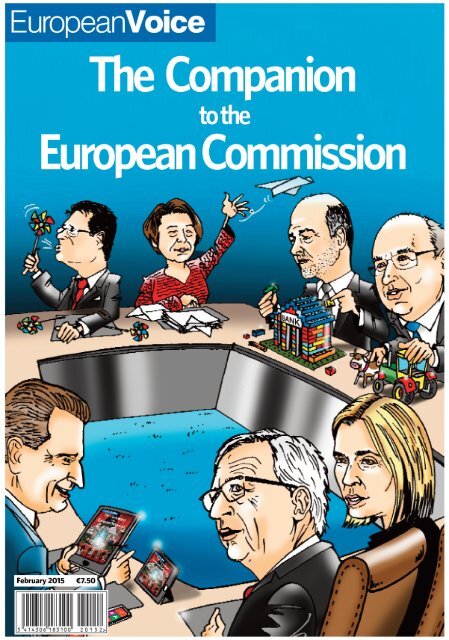

Cover Marco Villard<br />

Graphics Michael Agar | Darren Perera<br />

Artwork iStock | European Parliament | EPA<br />

European Voice provides<br />

essential, independent insight<br />

into the Brussels beltway for<br />

insiders and outsiders. As<br />

the leading source of news<br />

and analysis on key EU<br />

policies, laws and institutions,<br />

European Voice informs<br />

business leaders, policymakers<br />

and all those who<br />

have a stake in EU decisions.<br />

Our reporters cut through<br />

the complexity. They bridge<br />

the gap between technical<br />

minutiae and the big political<br />

picture. These values infuse<br />

our flagship weekly newspaper,<br />

our daily digital<br />

briefings and our live events.<br />

3

INTRODUCTION<br />

The European <strong>Commission</strong> that began<br />

work on 1 November 2014 is an<br />

administration on trial. Its president,<br />

JeanClaude Juncker, has promised an<br />

agenda of change – for the administration<br />

that he leads and for the European Union as<br />

a whole. The two are related: Juncker<br />

believes that reforms made to the<br />

<strong>Commission</strong> will have beneficial<br />

consequences for the work of the EU and<br />

therefore for how the EU is perceived in the<br />

wider world.<br />

From the outset, Juncker has made<br />

changes to the structure of the European<br />

<strong>Commission</strong> – to the way commissioners are<br />

organised and to the departmental<br />

configurations. In doing so, he has sent<br />

ripples of unease through the community of<br />

EUwatchers who had grown familiar with<br />

old ways of doing things. One of the<br />

questions examined during the course of this<br />

Companion to the European <strong>Commission</strong> is<br />

whether the changes that have been made<br />

are simply cosmetic or whether they will be<br />

of deep, lasting significance.<br />

This publication has a twin purpose. It sets<br />

out to explain the new structures and to put<br />

them in context. It also provides an<br />

introduction to the people who will adorn<br />

those structures: the 28 European<br />

commissioners and their staff. We explain<br />

where they have come from and suggest<br />

what their priorities might be. The aim is to<br />

put some human faces on what is often<br />

derided as a faceless bureaucracy. We do so<br />

not because we want the <strong>Commission</strong> to be<br />

loved, but because we think it should be<br />

understood.<br />

There has been much talk in recent years<br />

of how the European <strong>Commission</strong> has lost<br />

power relative to the other EU institutions –<br />

the European Parliament and the Council of<br />

Ministers. That is indeed the case, but the<br />

EU as a whole gained in power as a result of<br />

the Lisbon treaty of 2009. Moreover, the<br />

<strong>Commission</strong> is still the biggest and most<br />

complex of the three main EU institutions.<br />

The commissioners and their various<br />

departments will continue to make an<br />

impact on EU policy.<br />

The nature of such a volume is that it must<br />

be selective. If it were complete, it would be<br />

overweight and unread. This is a trimmer<br />

and more entertaining read, which still<br />

aspires to be useful. How long it remains so<br />

is in the lap of the gods, or perhaps Juncker.<br />

For the speed with which it becomes<br />

obsolete may be indicative of the success of<br />

Juncker’s reforms – or their failure.<br />

Tim King<br />

Editor, European Voice<br />

Brussels, February 2015<br />

CONTACT US<br />

International Press Centre, Résidence<br />

Palace, Rue de la Loi 155, Box 6, 1040<br />

Brussels, Belgium<br />

Switchboard<br />

+32 (0)2 540 9090<br />

Newsroom<br />

+32 (0)2 540 9068<br />

editorial@europeanvoice.com<br />

Sales<br />

+32 (0)2 540 9073<br />

sales@europeanvoice.com<br />

Subscriptions<br />

+32 (0)2 540 9098<br />

subscriptions@europeanvoice.com<br />

4<br />

SUBSCRIPTIONS<br />

One-year print and online subscription: €199<br />

One-year online-only subscription: €159<br />

(Rates are exclusive of VAT)<br />

Special corporate subscription rates<br />

(minimum six users).<br />

For more information visit<br />

www.europeanvoice.com/corporate<br />

www.europeanvoice.com<br />

Follow us on Twitter @EuropeanVoiceEV<br />

and on Facebook and Google+<br />

© European Voice All rights<br />

reserved. Neither this publication nor<br />

any part of it may be reproduced,<br />

stored in a retrieval system, or<br />

transmitted in any<br />

form by any means, electronic,<br />

mechanical, photocopying,<br />

recording or otherwise, without<br />

the prior permission of:<br />

European Voice<br />

Dénomination sociale:<br />

EUROPEAN VOICE SA.<br />

Forme sociale: société anonyme.<br />

Siège social: Rue de la Loi 155,<br />

1040 Bruxelles.<br />

Numéro d’entreprise: 0526.900.436<br />

RPM Bruxelles.<br />

For reprint information, contact:<br />

e.bauvir@europeanvoice.com

Competitiveness<br />

Begins with Confidence<br />

President Juncker is demonstrating decisive leadership<br />

in the design of the new <strong>Commission</strong> and by clearly<br />

differentiating many policy lines from the past.<br />

The key to success is in building confidence.<br />

That extends to business confidence too.<br />

Care must be taken not to simply talk competitiveness<br />

while undermining the industry we have. The EU must<br />

nurture a broad and balanced industrial base, especially<br />

its existing manufacturing industry, to sustain the<br />

European economy of the twenty first century.<br />

Policies once set must not be systematically revisited<br />

and changed. That destroys investor confidence.<br />

The EU must re-establish itself as a reliable location to<br />

invest, so that boardrooms in Europe and around the<br />

world extend existing manufacturing operations in the<br />

EU and inject new investment.<br />

The simple truth is that business needs stable policy<br />

and legal certainty to invest with confidence. Do the right<br />

thing, please, Mr. President!<br />

GOOD LUCK TO THE JUNCKER COMMISSION.<br />

International Paper Europe has reduced its greenhouse gas<br />

emissions by 73% since 1990. It is committing to reduce them<br />

a further 20% by 2020 (baseline 2010).<br />

The Company is currently planting in Poland what will be one<br />

of Europe’s largest woody biomass plantations providing<br />

carbon neutral energy for it’s manufacturing operations.<br />

5

DEPARTMENTS<br />

Juncker moves the pieces<br />

The European <strong>Commission</strong> began 2015<br />

with various changes to departmental<br />

structure taking effect.<br />

The changes were the result of a<br />

restructuring of <strong>Commission</strong> departments<br />

announced by JeanClaude Juncker, the<br />

president of the <strong>Commission</strong>, before he<br />

took office, reflecting in particular his<br />

thinking on how the <strong>Commission</strong> should<br />

support the economy and regulate business.<br />

The old directorategeneral for the internal<br />

market and services (DG MARKT), and the<br />

old directorategeneral for enterprise and<br />

industry (DG ENTR) were the two<br />

departments most affected by the changes.<br />

From the former, the responsibility for<br />

regulating financial services was stripped<br />

out to create a standalone department: the<br />

new directorategeneral for financial<br />

stability, financial services and capital<br />

markets union (DG FISMA). To it were<br />

added some units that were previously part<br />

of the directorategeneral for economic and<br />

financial affairs.<br />

The parts of the old DG MARKT that dealt<br />

with other economic sectors – focusing in<br />

particular on ensuring the free movement<br />

of goods and services as applied to those<br />

sectors – were transferred to the revamped<br />

DG Enterprise, which was renamed DG<br />

Growth (abbreviated to DG GROW). It also<br />

takes in the unit for health technology and<br />

cosmetics that was previously in the<br />

directorategeneral for health and<br />

consumers (DG SANCO).<br />

The unit dealing with copyright was<br />

moved from the internal market<br />

department to the department for<br />

communications networks, content and<br />

technology. The decision reflected the<br />

thinking that revising copyright rules for the<br />

digital age was a priority.<br />

The elements of DG SANCO that dealt<br />

with consumer policy were transferred to<br />

the directorategeneral for justice. DG<br />

SANCO has therefore been reduced to the<br />

directorategeneral for health and its<br />

abbreviation revised to DG SANTE.<br />

One of the effects of the changes is that<br />

the departmental responsibilities are more<br />

closely aligned with those of particular<br />

European commissioners. So DG GROW’s<br />

mandate is now more closely aligned with<br />

Elżbieta Bieńkowska, the European<br />

commissioner for internal market, industry,<br />

entrepreneurship and SMEs. DG FISMA’s<br />

mandate more closely matches the<br />

responsibilities of Jonathan Hill, the<br />

European commissioner for financial<br />

stability, financial services and capital<br />

markets union.<br />

<strong>Commission</strong> departments<br />

Agriculture and rural development (AGRI)<br />

Budget (BUDG)<br />

Climate action (CLIMA)<br />

Communication (COMM)<br />

Communications networks, content<br />

and technology (CNECT)<br />

Competition (COMP)<br />

Economic and financial affairs (ECFIN)<br />

Education and culture (EAC)<br />

Employment, social affairs and inclusion<br />

(EMPL)<br />

Energy (ENER)<br />

Environment (ENV)<br />

Eurostat (ESTAT)<br />

Financial stability, financial services and<br />

capital markets union (FISMA)<br />

Health and food safety (SANTE)<br />

Humanitarian aid and civil protection (ECHO)<br />

Human resources and security (HR)<br />

Informatics (DIGIT)<br />

Internal market, industry, entrepreneurship<br />

and SMEs (GROW)<br />

International co-operation and<br />

Development (DEVCO)<br />

Interpretation (SCIC)<br />

Joint research centre (JRC)<br />

Justice and consumers (JUST)<br />

Maritime affairs and fisheries (MARE)<br />

Migration and home affairs (HOME)<br />

Mobility and transport (MOVE)<br />

Neighbourhood and enlargement<br />

negotiations (NEAR)<br />

Regional and urban policy (REGIO)<br />

Research and innovation (RTD)<br />

Secretariat-general (SG)<br />

Service for foreign policy instruments (FPI)<br />

Taxation and customs union (TAXUD)<br />

Trade (TRADE)<br />

Translation (DGT)<br />

6

e-Contacts EP<br />

7

PRESIDENT<br />

Jean-Claude Juncker<br />

President of the European<br />

<strong>Commission</strong><br />

Country<br />

Born<br />

Luxembourg<br />

Redange, Luxembourg,<br />

9 December 1954<br />

Political affiliation EPP<br />

Twitter @JunckerEU<br />

JeanClaude Juncker has described the<br />

administration that he now heads as the<br />

“lastchance <strong>Commission</strong>” – one that has<br />

to restore trust in the European Union. If it<br />

fails, he implies, the credibility of the<br />

<strong>Commission</strong> will be lost forever.<br />

The oddity is that this lastchance<br />

<strong>Commission</strong> is headed by a secondchance<br />

politician. Juncker’s political career looked<br />

to have reached the end of the line when,<br />

after 18 years as prime minister of<br />

Luxembourg, he was forced to call a general<br />

election in 2013 and his political opponents<br />

formed a coalition that kept his centreright<br />

party out of government.<br />

That defeat proved to be the launchpad<br />

for another phase in his parallel career as a<br />

European Union politician. Despite the<br />

much talkedabout misgivings of Angela<br />

Merkel, Germany’s chancellor, he became<br />

the candidate of the centreright European<br />

People’s Party (EPP) for the presidency of<br />

the <strong>Commission</strong>, ie, the EPP went into the<br />

European Parliament elections saying that it<br />

wanted him to head the <strong>Commission</strong>. When<br />

the EPP emerged as the party with most<br />

seats in the European Parliament, his drive<br />

for the <strong>Commission</strong> presidency became<br />

unstoppable – whatever the objections of<br />

some members of the European Council (of<br />

whom David Cameron was the most vocal).<br />

So, improbably, Juncker, who had been<br />

talked about as a possible European<br />

<strong>Commission</strong> president in 2004, when José<br />

Manuel Barroso was first nominated, and<br />

again in 2009 as a possible president of the<br />

European Council, when Herman Van<br />

Rompuy was chosen, became president of<br />

the <strong>Commission</strong> in 2014.<br />

What made this secondcoming all the<br />

more surprising was that Juncker had<br />

become a figure of declining authority on<br />

the European stage. Although he had been<br />

a constant presence on the EU scene for 25<br />

years, his influence seemed to be waning in<br />

the second decade of the 21st century.<br />

At the creation of the euro in 1999,<br />

meetings of the eurozone finance ministers<br />

– the Eurogroup – did not have formal<br />

decisionmaking powers. Eurogroup<br />

meetings were by definition informal –<br />

8<br />

because the countries outside the eurozone<br />

(particularly the United Kingdom) were<br />

reluctant to grant them greater status.<br />

However, it was always clear that the<br />

Eurogroup would matter (its importance<br />

was belatedly recognised in the EU’s Lisbon<br />

treaty, which granted it formal status) and<br />

in 2004 the Eurogroup decided its<br />

chairmanship should be made semipermanent.<br />

Juncker became the first president of the<br />

Eurogroup in part because, as well as being<br />

finance minister of Luxembourg, a position<br />

he had held since 1989, he was also prime<br />

minister – a position he had succeeded to in<br />

1995 when Jacques Santer became<br />

president of the European <strong>Commission</strong>.<br />

As the head of a government, he had<br />

access to the offices of other government<br />

leaders (inside and outside the EU) that<br />

other finance ministers would not have.<br />

So as prime minister, Juncker was a member<br />

of the European Council from 19952013. As<br />

finance minister, he was attending the<br />

Council of Ministers from 19892009, after<br />

which he was still attending meetings of the<br />

Eurogroup as its president until the<br />

beginning of 2013.<br />

But as the eurozone went from creditcrunch<br />

to sovereign debt crisis to<br />

widespread recession, Juncker’s star was<br />

eclipsed, in part because responsibility for<br />

responding to events passed up to the<br />

European Council. The likes of Angela<br />

Merkel and Nicolas Sarkozy became the key<br />

figures – along with JeanClaude Trichet, the<br />

president of the European Central Bank, and<br />

his successor Mario Draghi. In comparison,<br />

Juncker seemed – perhaps understandably –<br />

exhausted.<br />

All this makes the resurrection of his<br />

European career, in the new incarnation of<br />

president of the European <strong>Commission</strong>,<br />

intriguing. Never before has an incoming<br />

<strong>Commission</strong> president had such a lengthy<br />

apprenticeship on the European stage.<br />

Never before has a <strong>Commission</strong> president<br />

had such a wealth of contacts across the<br />

European Union’s member states and<br />

beyond.<br />

But how does somebody so steeped in<br />

Europe’s past succeed in persuading voters<br />

that from now on things are different?<br />

Arguably Juncker ought to know Europe’s<br />

problems better than anyone, but does that<br />

mean that he has viable solutions?<br />

At the outset of his <strong>Commission</strong><br />

presidency, Juncker presented 10 strategic<br />

priorities that he planned to pursue – a far<br />

cry from the sprawling wishlist that have<br />

sometimes been espoused by incoming<br />

<strong>Commission</strong> presidents.<br />

He also announced a change to the<br />

structure of the college of commissioners<br />

and presented his plans for reorganising<br />

the structure of <strong>Commission</strong> departments.<br />

He has given the appearance of having a<br />

rediscovered sense of purpose. His<br />

admirers believe that his political<br />

awareness and his ability to forge<br />

compromises will give new purpose to the<br />

<strong>Commission</strong> that he heads. His doubters<br />

fear that he no longer has the energy or<br />

stamina to stay the course, and to stay<br />

engaged with the <strong>Commission</strong>’s work across<br />

such a broad front of policy portfolios.<br />

Whether those doubts are allayed may<br />

depend on his ability to manage his team<br />

effectively. His appointment of Frans<br />

Timmermans as first vicepresident was<br />

more than just politically astute (a balance<br />

of centreright and centreleft). It also sent<br />

a strong signal that he was not embarking<br />

on a ‘lookatme’ presidency. Modern<br />

politics – and the expansion of the EU to 28<br />

states – seem to dictate that European<br />

<strong>Commission</strong> administrations should be<br />

quite centralised, but Juncker’s lengthy<br />

political experience may have made him<br />

readier to share the limelight with others.<br />

Quite apart from Timmermans and Federica<br />

Mogherini, three of his vicepresidents are<br />

exprime ministers. Juncker is ready to<br />

share the workload. What he will provide is<br />

an intimate knowledge of the EU and<br />

wisdom accumulated over many years.

CV<br />

2004-13<br />

President of the Eurogroup<br />

1995-2013<br />

Prime minister of Luxembourg<br />

1995-2013<br />

Minister of state<br />

1989-2009<br />

Minister for finance<br />

1989-99<br />

Minister for labour<br />

1984-89<br />

Minister for labour, minister<br />

delegate for the budget<br />

1982-84<br />

State secretary for labour and social<br />

security<br />

1974<br />

Joined the CSV party<br />

Cabinet<br />

Head of cabinet<br />

Martin Selmayr<br />

Deputy head of cabinet<br />

Clara Martinez Alberola<br />

Cabinet members<br />

Sandra Kramer<br />

Luc Tholoniat<br />

Paulina Dejmek-Hack<br />

Carlo Zadra<br />

Antoine Kasel<br />

Telmo Baltazar<br />

Pauline Rouch<br />

Léon Delvaux<br />

Richard Szostak<br />

The cabinet<br />

Juncker’s private office is dominated by<br />

officials who worked for Viviane Reding<br />

when she was commissioner for three<br />

terms. Martin Selmayr was head of her<br />

private office when she was<br />

commissioner for justice, fundamental<br />

rights and citizenship. Other members<br />

of the office who worked for Reding<br />

include Richard Szostak, Paulina<br />

Dejmek-Hack, Telmo Baltazar, and<br />

Pauline Rouch. Clara Martinez-Alberola,<br />

a Spaniard who is deputy head of<br />

cabinet, used to work for José Manuel<br />

Barroso. Sandra Kramer, a Dutch official<br />

who is in charge of administrative<br />

issues, was in the <strong>Commission</strong>’s justice<br />

department before joining Juncker’s<br />

private office.<br />

Martin Selmayr<br />

Head of Juncker’s cabinet<br />

Country<br />

Born<br />

Twitter<br />

Germany<br />

Bonn, Germany,<br />

5 December 1970<br />

@MartinSelmayr<br />

Martin Selmayr, who heads the<br />

private office of JeanClaude<br />

Juncker, is already regarded as one<br />

of the most powerful people in the new<br />

administration. Indeed, people see his<br />

influence even when it is not there. Talked<br />

about in hushed tones, he is given almost<br />

mythical status, a latterday Count Olivares to<br />

Philip IV of Spain, or Cardinal Richelieu to<br />

Louis XIII of France, or (perhaps less<br />

fantastically) Pascal Lamy to Jacques Delors.<br />

Mythmaking is part of Selmayr’s art. He is a<br />

clever lawyer, who became a highly effective<br />

spindoctor, and then a policy adviser with his<br />

hands on patronage. He has used all these<br />

skills to such good effect that he now has<br />

many loyal supporters and not a few bitter<br />

enemies.<br />

He has worked for ten years in the<br />

<strong>Commission</strong>, but is still perceived by many as<br />

an outsider. He has not worked inside a<br />

<strong>Commission</strong> department. He has risen by<br />

making himself useful – even indispensable –<br />

to commissioners, and he has raised others<br />

after him.<br />

Now aged 44, Selmayr is by background an<br />

academic lawyer. He studied at the<br />

Universities of Geneva and Passau, at King’s<br />

College London, and at UCLA, Berkeley.<br />

He received a doctorate from Passau in 2001,<br />

with a thesis on the law of economic and<br />

monetary union. By then he had been<br />

working for the European Central Bank as<br />

legal counsel and then legal adviser.<br />

In 2001, he joined Bertelsmann, the German<br />

media company, and became head of its<br />

Brussels office in 2003. He has longestablished<br />

links with German Christian<br />

Democrats, notably Elmar Brok, a veteran<br />

MEP, who was retained by Bertelsmann.<br />

In 2004 Selmayr passed a European Union<br />

recruitment competition for lawyers and<br />

joined the <strong>Commission</strong> in November of that<br />

year. He became spokesperson for Viviane<br />

Reding, who was about to embark on her<br />

second term as a European commissioner,<br />

with the portfolio of information society and<br />

media.<br />

The portfolio included telecoms, and<br />

Selmayr’s greatest public relations triumph<br />

was winning credit for his commissioner for<br />

legislation to cap roaming charges. Although<br />

the telecoms companies complained that it<br />

HEAD OF CABINET<br />

was wealthy businesstravellers who stood to<br />

gain most from the cap, at the expense of<br />

other telecoms consumers, Selmayr<br />

positioned Reding and the <strong>Commission</strong> as the<br />

consumers’ champion. He clearly had a talent<br />

for massaging the message – he had a<br />

tendency to oversell his boss’s achievements<br />

and journalists soon learned to doublecheck<br />

what he said in briefings.<br />

But there was no doubting the strength of<br />

his bond with Reding. They were made for<br />

each other – neither was troubled by selfdoubt<br />

– and when she was nominated for a<br />

third term as Luxembourg’s European<br />

commissioner, he became head of her private<br />

office. It helped that Johannes Laitenberger,<br />

who had previously been head of Reding’s<br />

office, had by then advanced to head the<br />

office of José Manuel Barroso, the<br />

<strong>Commission</strong> president.<br />

Reding became commissioner for justice,<br />

fundamental rights and citizenship and was<br />

outspoken in her criticism of the Hungarian<br />

government’s treatment of Roma, and<br />

clashed on similar issues with the French and<br />

Italian governments.<br />

It was therefore a touch overconfident of<br />

Selmayr to develop plans for Reding to be the<br />

candidate of the European People’s Party for<br />

the presidency of the <strong>Commission</strong>. Selmayr<br />

sought to raise her profile as a champion of<br />

fundamental rights and gender equality with<br />

bold policy initiatives, such as the EU’s tough<br />

data protection rules and a bid to impose<br />

quotas on the number of women on company<br />

boards. It was beyond even his powers, but it<br />

did mean he was wellpositioned to take up<br />

the lance for JeanClaude Juncker, when a<br />

change of government in Luxembourg freed<br />

him to bid for the <strong>Commission</strong> presidency. He<br />

became campaign manager and was then<br />

appointed head of Juncker’s office.<br />

In turn, he has brought into the office of the<br />

<strong>Commission</strong> president and the<br />

spokesperson’s service officials who had<br />

worked for him with Reding.<br />

Few doubt Selmayr’s energy or his ambition,<br />

which will go a long way to compensate for<br />

his lack of experience in the <strong>Commission</strong>.<br />

How successful he is in enforcing the wishes<br />

of his master may depend on who is chosen<br />

as the next secretarygeneral of the<br />

<strong>Commission</strong>.<br />

9

VICE-PRESIDENTS<br />

The chosen ones<br />

From the moment that JeanClaude<br />

Juncker announced that he was<br />

creating a tier of seven vicepresidents<br />

with greater powers than the remaining 20<br />

commissioners, there were questions about<br />

what would make the vicepresidents<br />

different.<br />

The <strong>Commission</strong> has had vicepresidents<br />

before – there were initially seven in the<br />

201014 college, later increased to eight by<br />

the promotion of the commissioner for<br />

economic and monetary affairs – but apart<br />

from drawing a higher salary, it was hard to<br />

see what distinguished the vicepresidents<br />

from the others, not least because José<br />

Manuel Barroso assigned each<br />

commissioner a separate policy area.<br />

Juncker changed all that by making vicepresidents<br />

responsible for particular teams<br />

of commissioners (see opposite page).<br />

So in practice the ordinary commissioners<br />

become answerable to the vicepresidents.<br />

In turn, the vicepresidents have<br />

responsibility for policy areas that overlap<br />

or overlay those of the ordinary<br />

commissioners.<br />

So much for the theory. The question on<br />

many people’s lips was how will it work in<br />

practice? How much power would the vicepresidents<br />

have if they had no control of<br />

individual <strong>Commission</strong> departments? How<br />

would the ordinary commissioners<br />

respond to vicepresidential oversight?<br />

It did not take long (just one month) for<br />

the first clues and hints to emerge about<br />

the dynamics between commissioners and<br />

vicepresidents.<br />

On 2 December 2014, three members of the<br />

<strong>Commission</strong> went to the European<br />

Parliament to appear before a joint meeting<br />

of the committees for economic and<br />

monetary affairs and employment and<br />

social affairs. The three were led by Valdis<br />

Dombrovskis, the vicepresident for the<br />

euro and social dialogue, who was<br />

accompanied by Pierre Moscovici, the<br />

commissioner for economic and financial<br />

affairs, taxation and customs, and Marianne<br />

Thyssen, the commissioner for employment,<br />

social affairs, skills and labour mobility.<br />

Dombrovskis presented to MEPs the broad<br />

outlines of the <strong>Commission</strong>’s approach with<br />

an overview of the economic situation as<br />

well as an explanation of the annual growth<br />

strategy, stressing the importance of<br />

structural reform and financial<br />

responsibility. Moscovici talked about the<br />

situation of individual member states and<br />

the <strong>Commission</strong>’s assessment of their<br />

national budget plans, while Thyssen<br />

addressed employment issues and labour<br />

market reforms.<br />

10<br />

One of the important developments is that<br />

the Parliament is responding to the changed<br />

structure of the <strong>Commission</strong> with its own<br />

improvisations: in this case, a joint meeting<br />

of its committees.<br />

One committee on its own could not<br />

encompass the breadth of Dombrovskis’s<br />

responsibilities. Moscovici later addressed<br />

the economic and monetary affairs<br />

committee separately for a more specific<br />

discussion about national finances.<br />

The next day (3 December), the EU was<br />

represented at the EUUS energy council in<br />

Brussels by Federica Mogherini, the EU’s<br />

foreign policy chief, Maroš Šefčovič, the<br />

<strong>Commission</strong>’s vicepresident for energy<br />

union, and Miguel Arias Cañete, the<br />

European commissioner for climate action<br />

and energy.<br />

It is still not <strong>full</strong>y clear how the division of<br />

labour (and of status) will work out between<br />

Šefčovič and Cañete, though it was Cañete<br />

who went to Lima for international talks on<br />

climate change.<br />

The gap between Mogherini and the other<br />

commissioners working on foreign policy –<br />

Johannes Hahn (neighbourhood policy and<br />

enlargement negotiations); Cecilia<br />

Malmström (trade); Neven Mimica<br />

(international cooperation and<br />

development); and Christos Stylianides<br />

(humanitarian aid and crisis management) –<br />

is much clearer. Mogherini is not just a<br />

<strong>Commission</strong> vicepresident, but also the<br />

EU’s high representative for foreign affairs<br />

and security policy, and that, along with the<br />

resources of the European External Action<br />

Service, gives her extra status.<br />

In similar ways, Frans Timmermans – as<br />

first vicepresident – has been given extra<br />

status. He is in charge of better regulation,<br />

interinstitutional relations and rule of law.<br />

Both he and Kristalina Georgieva, the vicepresident<br />

with responsibility for budget and<br />

human resources, have remits that run<br />

across all <strong>Commission</strong> departments.<br />

On the other hand, it looks as if it will be<br />

harder for the more policyspecific vicepresidents<br />

to establish just how they are<br />

different from the commissioners beneath<br />

them (or alongside them?).<br />

The most intriguing potential source of<br />

tension is between Günther Oettinger, who<br />

has embarked on his second term as<br />

Germany’s European commissioner, but is<br />

not a vicepresident, and Andrus Ansip, a<br />

former prime minister of Estonia. The<br />

former is the commissioner for the digital<br />

economy and society; the latter is now<br />

<strong>Commission</strong> vicepresident for the digital<br />

single market.<br />

When Juncker and Timmermans were<br />

drawing up the <strong>Commission</strong>’s work<br />

programme for 2015, they convened a<br />

meeting of the vicepresidents, but the<br />

other 20 commissioners were not invited.<br />

It is here that, in theory at least, the vicepresidents<br />

have considerable power. They<br />

can promote – or, conversely, filter out –<br />

the projects of their commissioners.<br />

This gives a clue as to what makes the<br />

vicepresidents different: they enjoy their<br />

special power at the discretion of the<br />

president. It is effectively his delegated<br />

power that makes them more important<br />

than the other 20. If he convenes a meeting<br />

with the vicepresidents, they have his ear,<br />

the others do not.<br />

Logically, Juncker must refuse to allow the<br />

other commissioners to bypass their<br />

vicepresidents and to seek a direct line to<br />

him.

PROJECT TEAMS<br />

Team players?<br />

The President of the European<br />

<strong>Commission</strong> has named seven vicepresidents<br />

responsible for designated<br />

policy areas. The other 20 commissioners<br />

are arranged in project teams and are<br />

answerable to one or more vicepresidents.<br />

Despite this obvious hierarchy, Jean<br />

Claude Juncker has been at pains to stress<br />

that it is a college of equals. “In the new<br />

<strong>Commission</strong>, there are no first or secondclass<br />

commissioners – there are team<br />

leaders and team players,” he said when he<br />

unveiled his lineup in September 2014.<br />

Juncker warned the commissioners to<br />

prepare themselves for a “new collaborative<br />

way of working”.<br />

The vicepresidents “steer and coordinate”<br />

the work of other commissioners<br />

within “welldefined priority projects”.<br />

Juncker has said that he is delegating to<br />

his vicepresidents the power to stop<br />

members of their team from bringing a<br />

legislative proposal to the entire college.<br />

He will also delegate to the vicepresidents<br />

the resources of his secretariatgeneral.<br />

Project team<br />

Better regulation, interinstitutional<br />

relations, the rule of law, the Charter<br />

of Fundamental Rights and<br />

sustainable development<br />

Who is in charge?<br />

Frans Timmermans<br />

Which commissioners are involved?<br />

All of them<br />

Project team<br />

Budget and human resources<br />

Who is in charge?<br />

Kristalina Georgieva<br />

Which commissioners are involved?<br />

All of them<br />

Project team<br />

A deeper and fairer Economic and<br />

Monetary Union<br />

Who is in charge?<br />

Valdis Dombrovskis (the euro and social<br />

dialogue)<br />

Which commissioners are involved?<br />

Pierre Moscovici (economic and financial<br />

affairs, taxation and customs)<br />

Marianne Thyssen (employment, social<br />

affairs, skills and labour mobility)<br />

Jonathan Hill (financial stability, financial<br />

services and capital markets union)<br />

Elżbieta Bieńkowska (internal market,<br />

industry, entrepreneurship and SMEs)<br />

Tibor Navracsics (education, culture,<br />

youth and sport)<br />

Corina Creţu (regional policy)<br />

Vĕra Jourová (justice, consumers and<br />

gender equality)<br />

Project team<br />

A stronger global actor<br />

Who is in charge?<br />

Federica Mogherini (high representative<br />

of the EU for foreign affairs and security<br />

policy)<br />

Which commissioners are involved?<br />

Johannes Hahn (European neighbourhood<br />

policy and enlargement negotiations)<br />

Cecilia Malmström (trade)<br />

Neven Mimica (international<br />

cooperation and development)<br />

Christos Stylianides (humanitarian aid<br />

and crisis management)<br />

Project team<br />

A new boost for jobs, growth and<br />

investment<br />

Who is in charge?<br />

Jyrki Katainen (vicepresident for jobs,<br />

growth, investment and competitiveness)<br />

Which commissioners are involved?<br />

Günther Oettinger (digital economy and<br />

society)<br />

Pierre Moscovici (economic and financial<br />

affairs, taxation and customs)<br />

Jonathan Hill (financial stability, financial<br />

services and capital markets union)<br />

Elżbieta Bieńkowska (internal market,<br />

industry, entrepreneurship and SMEs)<br />

Marianne Thyssen (employment, social<br />

affairs, skills and labour mobility)<br />

Corina Crețu (regional policy)<br />

Miguel Arias Cañete (climate action and<br />

energy)<br />

Violeta Bulc (transport)<br />

Project team<br />

A resilient energy union with a forwardlooking<br />

climate change policy<br />

Who is in charge?<br />

Maroš Šefčovič (energy union)<br />

Which commissioners are involved?<br />

Miguel Arias Cañete (climate action and<br />

energy)<br />

Violeta Bulc (transport)<br />

Elżbieta Bieńkowska (internal market,<br />

industry, entrepreneurship and SMEs)<br />

Karmenu Vella (environment, maritime<br />

affairs and fisheries)<br />

Corina Creţu (regional policy)<br />

Phil Hogan (agriculture and rural<br />

development)<br />

Carlos Moedas (research, science and<br />

innovation)<br />

Project team<br />

A digital single market<br />

Who is in charge?<br />

Andrus Ansip (digital single market)<br />

Which commissioners are involved?<br />

Günther Oettinger (digital economy and<br />

society)<br />

Elżbieta Bieńkowska (internal market,<br />

industry, entrepreneurship and SMEs)<br />

Marianne Thyssen (employment, social<br />

affairs, skills and labour mobility)<br />

Vĕra Jourová (justice, consumers and<br />

gender equality)<br />

Pierre Moscovici (economic and financial<br />

affairs, taxation and customs)<br />

Corina Creţu (regional policy)<br />

Phil Hogan (agriculture and rural<br />

development)<br />

11

FIRST VICE-PRESIDENT<br />

F<br />

Better regulation, inter-institutional<br />

relations, rule of law and charter<br />

of fundamental rights<br />

Country<br />

Born<br />

rans Timmermans<br />

The Netherlands<br />

Maastricht,<br />

6 May 1961<br />

Political affiliation PES<br />

Twitter<br />

@TimmermansEU<br />

The choice of Frans Timmermans as<br />

righthand man to JeanClaude<br />

Juncker, the president of the European<br />

<strong>Commission</strong>, is a dream come true for the<br />

enthusiastically proEuropean Dutchman.<br />

Indeed, Timmermans, who as first vicepresident<br />

is officially as well as informally<br />

Juncker’s deputy, has a CV made to<br />

measure for a top post with an international<br />

organisation.<br />

When he was appointed as the<br />

Netherlands’ foreign affairs minister after<br />

the Dutch elections of 2012, diplomats said<br />

Timmermans was born for the job. He was<br />

wellinformed, understood foreign policy<br />

like no other and had language skills which<br />

are matched by few others in the college of<br />

commissioners. What is more he had the<br />

ambition and drive to go further.<br />

Then his popularity in the Netherlands<br />

received a boost – an unforeseen<br />

consequence of the MH17 plane crash in<br />

Ukraine in July 2014. Timmermans’s<br />

emotional speech mourning the death of so<br />

many Dutch men and women at the UN<br />

Security Council did not go unnoticed<br />

abroad either – if nothing else, his<br />

impeccable English made him stand out. His<br />

ability to speak Russian – a legacy of his<br />

military service as an intelligence officer –<br />

has also continued to serve him well as<br />

tension along the EU’s eastern border<br />

continues to mount.<br />

Besides Russian, English and Dutch<br />

Timmermans speaks German, French and<br />

Italian – a range he was more than happy to<br />

put on display at his hearing as a<br />

commissionerdesignate at the European<br />

Parliament. This drive to prove himself was<br />

applauded by the MEPs but seen as a<br />

weakness by some at home where it is<br />

considered unseemly to show off.<br />

Born in the Dutch bordercity of<br />

Maastricht, but growing up in nearby<br />

Heerlen, Timmermans attended primary<br />

school in nearby Belgium. He may have<br />

inherited some of his famously fiery<br />

temperament from his father, a policeman<br />

who later became a security officer at the<br />

Dutch foreign ministry, the job took him –<br />

and his son – all over Europe.<br />

At university in Nijmegen and Nancy,<br />

12<br />

Timmermans studied French literature for<br />

pleasure and European law to find a job.<br />

Following a diplomatic career that took him<br />

to Moscow, he became a member of staff<br />

for a European commissioner, Hans van den<br />

Broek, then private secretary to his mentor,<br />

Max van der Stoel, the high commissioner<br />

for minorities at the Organisation for<br />

Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE).<br />

He entered the Dutch parliament in 1998,<br />

becoming Labour’s foreignpolicy<br />

spokesman, but left when he joined the<br />

government as secretary of state for<br />

European affairs in 200710.<br />

Timmermans can appear aloof – some say<br />

he is a “classic social democrat” rather than<br />

a man of the people. However, his widely<br />

visited Facebook page on which he regularly<br />

posts pictures of football matches, his visits<br />

to the Pinkpop festival and other events in<br />

his private life suggests he understands the<br />

need to connect.<br />

The runup to the 2012 general election in<br />

the Netherlands did not suggest a<br />

ministerial career would be inevitable for<br />

Timmermans – in fact, with his Labour Party<br />

attracting low support it appeared<br />

Timmermans’s career had hit a wall. An<br />

attempt to be appointed governor of his<br />

native Limburg province failed, as did a bid<br />

to become the Council of Europe’s<br />

commissioner for humanrights. But his time<br />

CV<br />

2012-14 Foreign minister<br />

2010-12 Member of Dutch parliament<br />

2007-10 European affairs minister<br />

1998-2007 Member of Dutch parliament<br />

1995-98 Private secretary to OSCE high<br />

commissioner for national minorities<br />

1994-95 Assistant to European<br />

commissioner Hans van den Broek<br />

1993-94 Deputy head of department for<br />

developmental aid<br />

1990-93 Deputy secretary, Dutch<br />

embassy in Moscow<br />

1997-90 Policy office, ministry of foreign<br />

affairs<br />

1984-85 Postgraduate courses in<br />

European law and French literature,<br />

University of Nancy<br />

1980-85 Degree in French language and<br />

literature, Radboud University, Nijmegen<br />

was about to come.<br />

Once ensconced in the European<br />

<strong>Commission</strong>, Timmermans was awarded an<br />

enlarged portfolio which included<br />

‘sustainable development’, something S&D<br />

MEPs had demanded as a condition for<br />

their approval of Spain’s nominee to be<br />

commissioner for energy and climate<br />

Miguel Arias Cañete.<br />

Juncker, a longtime friend, assigned<br />

Timmermans the ‘better regulation’<br />

portfolio in response to longstanding<br />

Dutch criticism of redtape and excess EU<br />

legislation. Timmermans has a lot on his<br />

plate.<br />

Cabinet<br />

Head of cabinet<br />

Ben Smulders<br />

Deputy head of cabinet<br />

Michelle Sutton<br />

Cabinet members<br />

Antoine Colombani<br />

Liene Balta<br />

Riccardo Maggi<br />

Bernd Martenczuk<br />

Alice Richard<br />

Maarten Smit<br />

Saar Van Bueren<br />

Sarah Nelen<br />

Timmermans’ office is headed by Ben<br />

Smulders, a compatriot who was a<br />

principal legal adviser in the<br />

<strong>Commission</strong>’s legal service.<br />

Timmermans’ number two is Michelle<br />

Sutton, a British official who worked in<br />

the office of José Manuel Barroso. Other<br />

notable members of Timmermans’<br />

office include Antoine Colombani, a<br />

former competition department official<br />

who was spokesman for Joaquin<br />

Almunia when he was commissioner for<br />

competition, and Sarah Nelen, a Belgian<br />

who used to work for Herman Van<br />

Rompuy.

BETTER REGULATION<br />

To cut or not to cut?<br />

The unveiling of the European<br />

<strong>Commission</strong>’s 2015 work programme<br />

was marred by a nasty fight with<br />

MEPs over the planned withdrawal of two<br />

proposals – one on air quality and another<br />

on waste – that had already started making<br />

their way through the legislative process.<br />

They were just two of 80 pieces of draft<br />

legislation in line to be axed.<br />

The <strong>Commission</strong> was taken aback by the<br />

ferocity of the opposition to its plan. But for<br />

many MEPs the issue was symptomatic of a<br />

larger problem: the <strong>Commission</strong>’s response<br />

to the surge in Euroscepticism across<br />

Europe, which is that citizens are unhappy<br />

at the EU ‘meddling’ in people’s everyday<br />

lives.<br />

Frans Timmermans, the first vicepresident<br />

in charge of ‘better regulation’,<br />

has stressed that the EU should be big on<br />

the big things and small on the small things.<br />

But critics point out that there is a good<br />

reason for some small things being dealt<br />

with at a European level. They worry that a<br />

deregulatory response to the rise in the<br />

Eurosceptic vote does not address the real<br />

problem – a lack of acceptance by the<br />

public of the European project.<br />

Sophie in ’t Veld, a Dutch Liberal MEP,<br />

says the <strong>Commission</strong> is in danger of<br />

deregulation for deregulation’s sake. “I<br />

believe in smart trimming, not taking a<br />

blunt axe to the base of the tree,” she told<br />

Timmermans in December 2014. “The<br />

<strong>Commission</strong> should not throw the baby out<br />

with the bathwater by arbitrarily scrapping<br />

laws.”<br />

But Timmermans has sought to calm<br />

MEPs’ fears by insisting that his agenda is<br />

not to deregulate the EU. “Better<br />

regulation does not mean no regulation or<br />

deregulation,” he told MEPs. “We are not<br />

compromising on the goals we want to<br />

attain, we are looking critically at the<br />

methods we want to use.”<br />

Eventually, the <strong>Commission</strong> executed a<br />

Uturn on its plan to withdraw and redraft<br />

the airquality proposal, saying that it would<br />

instead work with MEPs and member states<br />

to adjust the plan as part of the normal<br />

codecision procedure. But it is sticking to<br />

its guns on the waste proposal (known as<br />

the ‘circular economy package’) and will put<br />

forward a new version in late 2015.<br />

Beyond the concerns about deregulation,<br />

many in the Parliament and the Council of<br />

Ministers have disputed the <strong>Commission</strong>’s<br />

prerogative to ‘political discontinuity’ –<br />

withdrawing proposals that have already<br />

been adopted and started the legislative<br />

process. Much of this battle is about<br />

institutional power. Withdrawing the<br />

proposals was seen as an affront to the<br />

other two institutions.<br />

Many of the 80 pieces of legislation listed<br />

for withdrawal were chosen for reasons of<br />

obsolescence or redundancy, and their<br />

withdrawal was previewed by the ‘refit’<br />

report issued in 2014 by José Manuel<br />

Barroso, the then president of the<br />

<strong>Commission</strong>. But 18 are being withdrawn<br />

because the <strong>Commission</strong> has deemed that<br />

no agreement is possible between member<br />

states, or between member states and<br />

MEPs. These include proposals for a<br />

directive on the taxing of motor vehicles<br />

that are moved from one country to<br />

another, a decision on the financing of<br />

nuclear power stations, a directive on rates<br />

of excise duty for alcohol, and a directive<br />

on medicinal prices.<br />

A proposed fund to compensate people<br />

who have suffered because of oil pollution<br />

damage in European waters is listed for<br />

withdrawal because “the impact<br />

assessment and relevant analysis are now<br />

out of date”.<br />

A proposed directive on taxation of<br />

energy products and electricity is listed for<br />

withdrawal because “Council negotiations<br />

have resulted in a draft compromise text<br />

that has <strong>full</strong>y denatured the substance of<br />

the <strong>Commission</strong> proposal”.<br />

Timmermans has indicated that Jean<br />

Claude Juncker’s <strong>Commission</strong> will be more<br />

aggressive about vetoing proposals if it<br />

thinks they have changed substantially<br />

during the legislative process.<br />

Proposed new rules on the labelling of<br />

organic products will be withdrawn unless<br />

there is an agreement between MEPs and<br />

member states within six months. A<br />

directive on maternity leave will also be<br />

withdrawn if there is no agreement within<br />

six months, although the <strong>Commission</strong> says<br />

that it would replace the latter with a new<br />

proposal.<br />

Over the course of 2015, MEPs will be<br />

watching closely for signs that the<br />

<strong>Commission</strong> intends to scale back<br />

legislation. If this is indeed the<br />

<strong>Commission</strong>’s strategy, it is unlikely to make<br />

much difference to the Euroscepticism felt<br />

in some parts of Europe.<br />

See pages 24-26 for more on<br />

the <strong>Commission</strong>’s work programme<br />

13

VICE-PRESIDENT<br />

Federica Mogherini<br />

High representative of the Union for<br />

foreign affairs and security policy<br />

Country Italy<br />

Born Rome, 16 June 1973<br />

Political affiliation PES<br />

Twitter<br />

@FedericaMog<br />

Even for a politician who has built a<br />

career around delivering grace under<br />

pressure, the intensity of the campaign<br />

levelled against Federica Mogherini ahead<br />

of her appointment to the EU’s top<br />

diplomatic post would have been unsettling.<br />

The youngest foreign minister in Italy’s<br />

republican history was attacked for her<br />

politics (too leftwing), her views on Ukraine<br />

(too proRussian), her CV (too thin) and<br />

even the writing style on her blog (too<br />

naïve).<br />

Yet the onslaught of criticism did not<br />

discourage the 41yearold, whose<br />

candidacy relied on Prime Minister Matteo<br />

Renzi’s rocksolid belief that it was Italy’s<br />

turn for a top European Union job. The<br />

Italians argued that opposition to<br />

Mogherini, coming largely from eastern and<br />

central European countries, was tactical<br />

rather than ideological. “It was about some<br />

member states using this as leverage to get<br />

a better deal for their own commissioners,”<br />

an Italian diplomatic source said at the time.<br />

Whatever the political machinations,<br />

Mogherini emerged with the plum position<br />

of High Representative of the Union for<br />

Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and as a<br />

vicepresident of the <strong>Commission</strong>. As things<br />

turned out, one of Mogherini’s harshest<br />

critics, Poland, also secured a top EU role,<br />

when its prime minister, Donald Tusk, was<br />

appointed as president of the European<br />

Council.<br />

The whispering campaign against<br />

Mogherini had centred on her apparent<br />

cosying up to Russian President Vladimir<br />

Putin during a state visit as Italian foreign<br />

minister, in which she ruled out a “military<br />

solution” to the Ukrainian crisis. The Poles<br />

and the Baltic states were dismayed by<br />

the prospect of EU policy towards an<br />

increasingly assertive Russia being set by an<br />

Italian with a track record of appeasing<br />

Moscow.<br />

Even though Mogherini and Renzi<br />

ultimately won the day, since taking office<br />

Mogherini has been at pains to scupper the<br />

perception she is anything but a hardliner<br />

on Russia. Her first announcement when in<br />

office was a strongly worded statement on<br />

Ukraine, in which she dismissed as<br />

“illegal and illegitimate” elections held in<br />

14<br />

separatistcontrolled areas of the country.<br />

Yet even before Mogherini had a chance to<br />

settle into her new digs on the 11th floor of<br />

the Berlaymont building, Russia had come<br />

back to haunt her. A media report revealed<br />

the high representative’s spokeswoman,<br />

Catherine Ray, was married to a partner in a<br />

Brussels public relations firm that lobbies<br />

for Russian stateowned gas company<br />

Gazprom. Mogherini’s office was quick to<br />

shrug off the controversy, yet it was a<br />

reminder of what Mogherini has already<br />

said publicly: Russia is set to dominate her<br />

portfolio over the coming years.<br />

While Mogherini supporters argue that<br />

her proWestern credibility is beyond doubt,<br />

it is also true that her first political step was<br />

to sign up to the Italian Young Communist<br />

Federation in 1988, when she was a<br />

straightA student from a middleclass<br />

background in Rome. The daughter of film<br />

director Flavio Mogherini, Federica went to<br />

a local high school with a focus on<br />

languages (she speaks French, English and<br />

some Spanish). She went on to complete a<br />

degree at Rome’s Sapienza University, her<br />

thesis on Islam earning her top marks.<br />

Mogherini then became a party apparatchik,<br />

working for the Democratic Party (or its<br />

earlier postcommunist incarnations) in a<br />

foreignpolicy unit. It was at this time that<br />

she met her husband Matteo Rebesani, who<br />

was head of the international office of<br />

Walter Veltroni, then the mayor of Rome<br />

and a Democratic Party powerbroker. The<br />

CV<br />

2014 Foreign minister and<br />

international co-operation minister<br />

2013-14 Head of the Italian delegation to<br />

the NATO parliamentary assembly<br />

2008-14 Member of parliament<br />

2008-13 Member of the Parliamentary<br />

Assembly of the Council of Europe<br />

2008-present Member of the Italian<br />

Institute for Foreign Affairs<br />

2007 Fellow of the German Marshall<br />

Fund for the United States<br />

1994 Degree in political science from the<br />

University of Rome<br />

couple have two young daughters, Caterina<br />

and Marta.<br />

Mogherini’s rise through party ranks was<br />

swift and in 2008 she was elected to the<br />

Italian parliament. She remained factionally<br />

aligned with the PD’s old guard and her<br />

relationship with Renzi was marred by<br />

some disparaging remarks about him made<br />

from Mogherini’s Twitter account. Yet, in<br />

spite of the bad blood, Renzi wasted little<br />

time in awarding Mogherini the foreign<br />

ministry, only to back her all the way to<br />

Brussels a few months later.<br />

Cabinet<br />

Head of cabinet<br />

Stefano Manservisi<br />

Deputy head of cabinet<br />

Oliver Rentschler<br />

Cabinet members<br />

Felix Fernandez-Shaw<br />

Fabrizia Panzetti<br />

Michael Curtis<br />

Peteris Ustubs<br />

Arianna Vannini<br />

Anna Vezyroglou<br />

Iwona Piorko<br />

Enrico Petrocelli<br />

Federica Mogherini has filled her<br />

cabinet with what she herself lacks:<br />

extensive experience of the EU’s<br />

institutions. That is true, above all, of<br />

her chief of staff, Stefano Manservisi, a<br />

fellow Italian. Southern Europeans<br />

predominate, but northern (and,<br />

importantly, central and eastern) Europe<br />

is also represented. Mogherini came to<br />

prominence in a government that<br />

praised itself as being part of the<br />

Erasmus generation; her own cabinet is<br />

youthful with some of the younger<br />

members also bringing links to the<br />

European Parliament and the Italian<br />

parliament.

FOREIGN AFFAIRS<br />

A focus on foreign policy<br />

One of the most important<br />

developments during the last<br />

European <strong>Commission</strong>, Barroso II,<br />

was the establishment of the European<br />

External Action Service (EEAS). One of the<br />

big questions for Juncker I is whether some<br />

of the structural damage done during the<br />

last five years can be repaired and relations<br />

between the foreign policy structures of the<br />

<strong>Commission</strong> and the EEAS made more<br />

harmonious.<br />

The creation of the EEAS outside the<br />

<strong>Commission</strong> involved the transfer of<br />

hundreds of staff out of the <strong>Commission</strong>’s<br />

service into that of the EEAS, which was<br />

populated with a mix of ex<strong>Commission</strong><br />

officials, diplomats from the services of the<br />

member states, and officials previously<br />

employed in the secretariat of the Council<br />

of Ministers. In the process, divisions were<br />

created or widened between those now<br />

working in the EEAS and those who<br />

remained behind in the <strong>Commission</strong>.<br />

JeanClaude Juncker indicated his desire<br />

to narrow the gap between the EEAS and<br />

the <strong>Commission</strong> when he asked Federica<br />

Mogherini, the new high representative for<br />

foreign and security policy (who is also a<br />

vicepresident of the <strong>Commission</strong>) to<br />

establish her main office in the Berlaymont,<br />

the <strong>Commission</strong>’s headquarters. Her<br />

predecessor, Catherine Ashton, had<br />

operated principally out of the EEAS’s<br />

headquarters.<br />

Arguably just as significant for the<br />

development of <strong>Commission</strong>EEAS relations<br />

as the location of Mogherini’s office is her<br />

choice of Stefano Manservisi to run that<br />

office. Manservisi, who is now her chef de<br />

cabinet, had been working in the EEAS – as<br />

the EU’s ambassador to Turkey – but he was<br />

a recent arrival from the <strong>Commission</strong>,<br />

where he had variously been directorgeneral<br />

for home affairs, directorgeneral<br />

for development and head of the office of<br />

Romano Prodi, when he was <strong>Commission</strong><br />

president. He has brought to Mogherini’s<br />

office a knowledge of how the <strong>Commission</strong><br />

works and a wealth of longstanding<br />

relationships that Ashton’s private office did<br />

not have.<br />

Manservisi will know that the EEAS will be<br />

stronger and work more efficiently if it can<br />

make greater use of the staff and resources<br />

of the <strong>Commission</strong> and coordinate its work<br />

with that of the foreign policy parts of the<br />

<strong>Commission</strong>. Mogherini, who was previously<br />

Italy’s foreign minister, and who, as high<br />

representative for foreign and security<br />

policy, now chairs meetings of the EU’s<br />

foreign ministers, will be well aware that<br />

the member states do not want the EEAS to<br />

be swallowed up again by the <strong>Commission</strong>.<br />

The point of creating the EEAS as a hybrid<br />

institution, outside the Council and the<br />

<strong>Commission</strong>, was to achieve a balance. The<br />

role of Mogherini, as both vicepresident of<br />

the <strong>Commission</strong> and high representative, is<br />

to embody that balance.<br />

The parts of the <strong>Commission</strong> that work on<br />

foreign policy are many and varied.<br />

Arguably the most institutionally curious is<br />

the Foreign Policy Instrument Service. It is a<br />

vestige of the old directorategeneral for<br />

external relations – a part that was not<br />

transferred into the EEAS because it deals<br />

with money and its budget remained with<br />

the <strong>Commission</strong>.<br />

The FPI dispenses money to implement<br />

the policies of the EEAS through various<br />

budgetary instruments: the instrument for<br />

operations of the common foreign and<br />

security policy; the instrument contributing<br />

to stability and peace; the partnership<br />

instrument (which provides some means to<br />

spend on cooperation with middleincome<br />

and highincome countries that do not<br />

qualify for development aid). Together<br />

these add up to less than €1 billion a year,<br />

but that is money that the EEAS covets.<br />

Continues on page 16<br />

15

FOREIGN AFFAIRS<br />

Continued from page 15<br />

(The budget of the EEAS is basically an<br />

administrative one – to pay for the people<br />

and buildings at the EEAS’s headquarters in<br />

Brussels and in the EU’s delegations<br />

abroad.) The staff of FPI are answerable<br />

directly to Mogherini, whereas the other<br />

<strong>Commission</strong> foreign policy departments<br />

answer to other European commissioners.<br />

Those other departments are:<br />

the directorategeneral for international<br />

cooperation and development (DG DEVCO),<br />

which is principally, but not exclusively,<br />

occupied with relations with lowincome<br />

developing countries, most of them being<br />

members of the African, Caribbean and<br />

Pacific organisation. The EU’s budget for the<br />

ACP remains separate from the rest of the<br />

EU’s budget and the <strong>Commission</strong> must<br />

account separately for the ACP budget.<br />

The directorategeneral for humanitarian<br />

aid and civil protection (DG ECHO), which<br />

coordinates the EU’s response to<br />

emergencies. As an instrument of foreign<br />

policy, it is necessarily much less strategic<br />

than DG DEVCO but does some of the EU’s<br />

most visible work abroad.<br />

The directorategeneral for neighbourhood<br />

and enlargement negotiations (DG NEAR). To<br />

what was previously the directorategeneral<br />

for enlargement has been added a<br />

directorate that was previously in DG DEVCO<br />

that handles relations with the countries of<br />

the neighbourhood, on the EU’s southern<br />

and eastern borders. That addition signals<br />

both the increasing importance of the<br />

neighbourhood and diminished expectations<br />

about any further admissions to EU<br />

membership in the short term.<br />

The directorategeneral for trade (DG<br />

TRADE) is one of the <strong>Commission</strong>’s most<br />

powerful departments, in part because it<br />

has acquired powers to act on behalf of the<br />

whole EU, in part because trade is so<br />

important to both domestic and foreign<br />

policy. Trade has long been an important<br />

instrument of foreign policy (witness the<br />

use of trade disputes in recent<br />

confrontations with Russia) and it is also<br />

now increasingly bound up with<br />

development policy.<br />

Additionally, there are various significant<br />

parts of other <strong>Commission</strong> departments<br />

that have an international dimension:<br />

agriculture; maritime affairs and fisheries;<br />

environment; climate action; migration and<br />

home affairs; mobility and transport;<br />

energy; economic and monetary affairs;<br />

research and innovation.<br />

Depending on the state of international<br />

negotiations (or international disputes), the<br />

foreign policy aspects of these policy<br />

departments will fluctuate, but overall it<br />

becomes obvious that coherent EU foreign<br />

policy depends on coordination of the<br />

<strong>Commission</strong>’s international work with that<br />

of the EEAS and the Council of Ministers.<br />

16<br />

One of the optimistic features of Juncker I<br />

is that the reorganisation of the European<br />

commissioners into teams offers a serious<br />

prospect of developing a team of<br />

commissioners working on aspects of<br />

foreign policy. If such teamwork becomes<br />

the norm across the whole <strong>Commission</strong> (see<br />

pages 1011) there is a greater prospect of it<br />

being established in the field of foreign<br />

policy. In theory, that possibility existed in<br />

the last <strong>Commission</strong>; in practice, Ashton did<br />

not make it happen. This time round, it<br />

seems more likely that Mogherini will make<br />

greater use of the likes of Johannes Hahn,<br />

Neven Mimica, Christos Stylianides and<br />

Cecilia Malmström. Just as importantly,<br />

Manservisi and Alain Le Roy, the incoming<br />

secretarygeneral of the EEAS, should be<br />

able to coordinate their work with<br />

<strong>Commission</strong> departments.

VICE-PRESIDENT<br />

Kristalina Georgieva<br />

Budget and human resources<br />

Country Bulgaria<br />

Born Sofia, 13 August 1953<br />

Political affiliation None<br />

Twitter<br />

@KGeorgievaEU<br />

Kristalina Georgieva’s career as a<br />

European commissioner began so<br />

suddenly that her then 89yearold<br />

mother Minka learned the news from the<br />

television. The economist received a 3am<br />

phonecall from Bulgaria’s prime minister,<br />

Boyko Borisov, and within hours she was on<br />

a plane from the United States to Europe.<br />

The sense of urgency was real. Bulgaria’s<br />

first choice for the <strong>Commission</strong> in 2009,<br />

Rumiana Jeleva, had performed disastrously<br />

in her European Parliament hearing and the<br />

appointment of the new <strong>Commission</strong> had<br />

been put on hold until the country put<br />

forward another candidate. Georgieva, who<br />

at the time was vicepresident of the World<br />

Bank, did not hesitate to accept the role. “I<br />

agreed to become a commissioner because<br />

the situation wasn’t good for Bulgaria and<br />

there was a possibility of our reputation<br />

being hurt,” she said.<br />

Georgieva’s 2014 promotion to one of the<br />

<strong>Commission</strong>’s most important vice<br />

presidencies, overseeing the budget and<br />

human resources portfolio, was a reward<br />

for her success in the last <strong>Commission</strong>,<br />

when she was in charge of international<br />

cooperation, humanitarian aid and crisis<br />

response. She is today the most senior<br />

technocrat in the <strong>Commission</strong>, one of only<br />

two of the seven vicepresidents never to<br />

have served as a national minister.<br />

Georgieva is the greatgranddaughter of<br />

Ivan Karshovski, a 19thcentury<br />

revolutionary considered to be one of the<br />

founding fathers of Bulgaria. While<br />

Georgieva grew up in a family with a proud<br />

history, her background was, in other<br />

respects, ordinary. Her mother ran a shop in<br />

Sofia, Bulgaria’s capital, while her father<br />

was a construction engineer.<br />

At university in Sofia, Georgieva made a<br />

name for herself as a budding economist.<br />

But she also used her time to write poetry,<br />

play the guitar (the Beatles were a<br />

favourite), cook and dance. She remained at<br />

the same university for 16 years, producing<br />

a work on economics that remains a<br />

standard textbook. She specialised,<br />

however, in environmental economics,<br />

writing her doctorate linking environmental<br />

protection policy and economic growth in<br />

the United States.<br />

After the collapse of communism,<br />

Georgieva’s academic career took her, as a<br />

visiting scholar and professor, to the US,<br />

Europe and the Pacific. But she also<br />

developed a line as a consultant, bringing<br />

her into contact with the World Bank. That<br />

relationship turned into a 16year career<br />

which took her around the world, running<br />

World Bank programmes. She also set up a<br />

Bulgarian folk dance group at the World<br />

Bank’s headquarters in Washington DC.<br />

Georgieva seems to have left behind a<br />

consistently positive impression. Many<br />

described her as a woman who manages<br />

with an iron fist inside a velvet glove,<br />

someone of inexhaustible energy who can<br />

chafe at slow progress.<br />

Despite her long absence from Bulgaria,<br />

Georgieva’s voice has been heard in her<br />

home country. Her high profile prompted<br />

Borisov to consider her for the post of<br />

finance minister in 2009, but she chose<br />

instead to act as an adviser.<br />

That association with Borisov might<br />

suggest her politics are centreright. Ivan<br />

CV<br />

2010-14 European commissioner for<br />

international co-operation, humanitarian<br />

aid and crisis response<br />

2008-10 Vice-president and corporate<br />

Secretary of the World Bank<br />

2007-08 World Bank director for<br />

strategy and sustainable development<br />

2004-07 World Bank director for Russia<br />

2000-04 World Bank director for<br />

environmental strategy<br />

1983-99 Environmental economist,<br />

senior environmental economist, sector<br />

manager, sector director at the World<br />

Bank<br />

1992 Consultant, Mercer Management<br />

Consulting<br />

1987-88 Research fellow, London School<br />

of Economics and Political Science<br />

1986 PhD in economics, University of<br />

National and World Economy<br />

1977-93 Assistant professor/associate<br />

professor, University of National and<br />

World Economy<br />

1976 Master’s degree in political<br />

economy and sociology, University of<br />

National and World Economy<br />

Kostov, a former prime minister and fellow<br />

student at university, says otherwise.<br />

“Although she has very leftist beliefs, she is<br />

undoubtedly competent,” says Kosov, who<br />

now leads the rightwing Democrats for a<br />

Strong Bulgaria. What interests Georgieva<br />

are solutions, rather than politics. “For me,<br />

a problem exists to be solved,” she says.<br />

A strong performance in her first term as<br />

a commissioner, and as someone with<br />

experience of managing €20 billion in<br />

World Bank programmes, should help<br />

Georgieva deal with the EU’s regular,<br />

interinstitutional battles over the makeup<br />

of the budget which have now become her<br />

area of responsibility.<br />

Cabinet<br />

Head of cabinet<br />

Mariana Hristcheva<br />

Deputy head of cabinet<br />

Andreas Schwarz<br />

Cabinet members<br />

Elisabeth Werner<br />

Sophie Alexandrova<br />