Living Architecture Monitor - Green Roofs for Healthy Cities

Living Architecture Monitor - Green Roofs for Healthy Cities

Living Architecture Monitor - Green Roofs for Healthy Cities

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

GREEN ROOFS FOR HEALTHY CITIES<br />

WINTER<br />

VOLUMENO<br />

LIVING<br />

ARCHITECTURE<br />

MONITOR<br />

PLANTSFORHOTCOLD<br />

ANDDROUGHTS<br />

ORGANICVS<br />

INORGANIC?<br />

CREATINGHABITAT

LIVING<br />

ARCHITECTURE<br />

MONITOR<br />

WINTERVOLUMENO<br />

<strong>Living</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong> is published four times per year by<br />

<strong>Green</strong> <strong>Roofs</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Healthy</strong> <strong>Cities</strong>* (www.greenroofs.org)<br />

Steven W. Peck<br />

Publisher & Founder<br />

speck@greenroofs.org<br />

416.971.4494 ext. 233<br />

Caroline Nolan<br />

Editor<br />

cnolan@greenroofs.org<br />

416.971.4494 ext. 231<br />

ARTDIRECTION<br />

IR&Co Inc.<br />

ADVERTISE<br />

416.971.4494 ext. 231 or advertise@greenroofs.org<br />

Rate card & insertion order <strong>for</strong>m are also available online at<br />

www.greenroofs.org/magazine<br />

SUBSCRIBE<br />

Subscriptions are included with membership to <strong>Green</strong> <strong>Roofs</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Healthy</strong> <strong>Cities</strong>.<br />

Three levels of membership are available (in US dollars):<br />

1. Supporter Membership - $50<br />

2. Professional Membership - $149<br />

3. Corporate Memberships - $750 to $4800<br />

To learn more about our various membership levels and their various other benefits<br />

please visit our website at: www.greenroofs.org<br />

Change address<br />

circulation@greenroofs.org or mail or fax to address below.<br />

CONTACTUS<br />

406 King Street East, Toronto, Ontario M5A 1L4 Canada<br />

Tel. 416.971.4494 Fax 416.971.9844<br />

www.greenroofs.org<br />

SUBMITNEWSSTORYIDEASORFEEDBACK<br />

We welcome letters to the editor, feedback and comments, as well as story<br />

ideas and industry news about people, products and projects <strong>for</strong> consideration<br />

in upcoming editions of the <strong>Living</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong>: editor@greenroofs.org.<br />

<strong>Green</strong> <strong>Roofs</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Healthy</strong> <strong>Cities</strong> — North America, Inc. was founded in 1999 as a<br />

small network of public and private organizations and is now a rapidly growing<br />

501(c)(6), not-<strong>for</strong>-profit industry association. Our mission is to increase the<br />

awareness of the economic, social and environmental benefits of green roofs<br />

and green walls, and other <strong>for</strong>ms of living architecture through education,<br />

advocacy, professional development and celebrations of excellence.<br />

Members of Board<br />

Peter Lowitt, chair, Devens Enterprise Commission<br />

Dan Sloan, secretary, McGuire Woods LLP<br />

Richard J. Buist, Landscource Organixs Ltd.<br />

Jeffrey Bruce, Jeffery L. Bruce & Co. LLC<br />

Peter D’Antonio, Sika Sarnafil Inc.<br />

Karen Moyer, City of Waterloo (Ontario)<br />

*<strong>for</strong>merly the <strong>Green</strong> Roof Infrastructure <strong>Monitor</strong><br />

Disclaimer: Contents are copyrighted and may not be reproduced without written consent. Every ef<strong>for</strong>t has<br />

been made to ensure the in<strong>for</strong>mation presented is accurate. The reader must evaluate the in<strong>for</strong>mation in<br />

light of the unique circumstances of any particular situation and independently determine its applicability.

COLD<br />

What can we learn from the climate characteristics of<br />

Nordic green roofs?<br />

By Kerry Ross<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

FROMTHEFOUNDER<br />

AVISIONFORTHEFUTURE<br />

By Steven W. Peck<br />

STRATA—PEOPLEPRODUCTS&PROJECTS<br />

ALIVINGLABORATORY<br />

Students and scientists team up on two green roofs at<br />

New York City’s Ethical Culture Fieldston School.<br />

GROUND-BREAKINGSUSTAINABLESITES<br />

INITIATIVELAUNCHED<br />

ASLA, Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center and<br />

others developing voluntary standards <strong>for</strong> sustainable<br />

land use and landscaping practices.<br />

REVIEW<br />

Books: ALSA’s Case Study; Ian McHarg — Conversations<br />

with Students; Busby: Learning Sustainable<br />

Design; and Alessandro Rocca’s Natural <strong>Architecture</strong><br />

ONTHEROOFWITH…<br />

AQ&AWITHTHELEGENDARYLANDSCAPE<br />

ARCHITECTCORNELIAHAHNOBERLANDER<br />

By Caroline Nolan<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

DROUGHT<br />

Evaluating the per<strong>for</strong>mance of green roof plants and<br />

growing medium.<br />

By Dr. Bill Retzlaff, Dr. Susan Morgan, Kelly Luckett<br />

and Vic Jost<br />

CREATINGHABITAT<br />

BYDESIGN<br />

A new process model can help you make the right<br />

decisions when trying to restore habitats <strong>for</strong> a specific<br />

species on green roofs and wall projects.<br />

By Dr. Reid Coffman and Alison Thurmond<br />

POLICY<br />

SEATTLE’S“GREENFACTOR”<br />

A new urban landscaping policy is creating an incentive<br />

<strong>for</strong> more green roofs and walls in this coastal city.<br />

By Lillian Mason and GRHC staff<br />

”BUSHTOPS”DOWNUNDER<br />

South Australian government’s green wall and green<br />

roof incentive policies are bringing the “bush” back<br />

into Adelaide.<br />

By Graeme Hopkins & Christine Goodwin<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

PROJECT<br />

ISLANDPARADISE<br />

An award-winning Ontario residential project — three<br />

years later.<br />

By Flavia Bertram<br />

BESTPRACTICE<br />

GROWINGMEDIA—THEORGANICQUESTION<br />

Rick Buist & Chuck Friedrich face off on how much<br />

organic — if any — is best <strong>for</strong> optimal per<strong>for</strong>mance.<br />

NATIVEPLANTRESEARCH<br />

IMPACTOFGROWINGMEDIAONPRAIRIEGRASSES<br />

Thinking like a prairie in Lincoln, Nebraska.<br />

By Richard K. Sutton<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

GRHCUPDATE<br />

GREENWALLTECHNOLOGYCLIMBING<br />

By Lillian Mason and GRHC staff<br />

OMAHAWELCOMESOPPORTUNITYTOBUILD<br />

MOREGREEN ROOFS<br />

Stormwater management among topics discussed at recent<br />

Nebraskan-based Local Market Development Symposium.<br />

By Kent E. Holm<br />

SYMPOSIUMIGNITESGREENROOF&WALL<br />

MOMENTUMINATLANTA<br />

From architects to policymakers — the finest<br />

professionals gathered to brainstorm an action plan<br />

<strong>for</strong> more green roofs in Georgia’s capital city.<br />

By Lillian Mason & GRHC staff<br />

<br />

NATIVESURVIVORS<br />

Insights from study conducted by the New England Wild<br />

Flower Society in partnership with the Massachusetts<br />

College of Art.<br />

By Ron M. Wik<br />

<br />

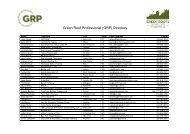

FROMTHEACCREDITATIONSUB-COMMITTEE<br />

First <strong>Green</strong> Roof Professional accreditation exam<br />

planned <strong>for</strong> 2009 conference in Atlanta, Georgia.<br />

By Hazel Farley<br />

<br />

EXTREMECONDITIONS<br />

HOT&HUMID<br />

What plants work best in tropical and subtropical climates?<br />

By Steve Skinner<br />

<br />

ONSPEC<br />

FROMWHEREIAGREENROOFERSIT<br />

The role of the landscaper on green roof projects.<br />

By Kurt Horvarth

FROMTHEFOUNDER<br />

AVISIONFOR<br />

THEFUTURE<br />

IMAGINEASWEDOOURCOLLECTIVE<br />

POWERTOCREATEHEALINGRESTORATIVE<br />

BUILDINGSDESIGNEDWITHLIVING<br />

ARCHITECTUREPRINCIPLES<br />

THEEDITTBUILDINGINSINGAPORE<br />

Image courtesy of TR Hamzah & Yeang Sdn Bhd

THEGROWINGMEDIA&PLANTISSUE<br />

Welcome to the <strong>Living</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong>. We are dedicated<br />

to bringing you the best research, policy and practices<br />

focused on the integration of living and non-living elements<br />

in and around buildings. <strong>Living</strong> architecture is the pathway to<br />

making a more fundamental shift towards the creation of<br />

healing, restorative high-per<strong>for</strong>mance buildings — and by<br />

extension, healthier, more liveable communities.<br />

In essence, healing, restorative, high-per<strong>for</strong>mance buildings give back<br />

more than they use over their lifecycles: producing a surplus of renewable<br />

energy, cleaner water, improved air quality and aesthetics,<br />

the very foundation <strong>for</strong> vibrant biological diversity and the greater<br />

physical and emotional well-being of humans.<br />

<strong>Green</strong> roofs and green walls are two key elements of living<br />

architecture that are gaining more widespread acceptance<br />

throughout North America. These living architectural <strong>for</strong>ms allow<br />

<strong>for</strong> unparalleled benefits at different scales — at the site level<br />

(aesthetics, stormwater quality and quantity): at the building level<br />

(energy savings, noise reduction, membrane durability, recreation<br />

space, urban food production, improved PV efficiency, biodiversity,<br />

advertising, marketability, improved investment value); at the community<br />

level (improved aesthetics, air quality benefits, cooling<br />

urban heat island, noise abatement, educational opportunities,<br />

community food production, psychological benefits); and the wider<br />

region (reducing greenhouse gases, supporting ecological diversity)<br />

— and this list is by no means complete.<br />

We need to re-imagine buildings as small ecosystems, nestled within<br />

the larger bioregions of our communities. McDonough and Braungart,<br />

in Cradle to Cradle, call <strong>for</strong> a shift toward “eco-effectiveness” and<br />

suggest we adopt a new design assignment set out to create “buildings,<br />

that like trees, produce more energy than they consume and purify<br />

their own wastes.” Restorative buildings won’t add more stress to<br />

existing infrastructure, such as coal-fired plants and the lengthy<br />

transmission wires that supply power; or our overtaxed water and<br />

wastewater treatment plants that regularly discharge vast quantities<br />

of raw sewage into our lakes, rivers and oceans.<br />

filtered through a series of ‘John Todd like’ facades and vegetated-terraces.<br />

The indigenous vegetation areas are designed to be continuous<br />

and to ramp upwards from the ground plane to the uppermost floor in<br />

a linked landscaped ramp. The design’s planted-areas constitute 3,841<br />

sq.m., a ratio 1:0.5 of gross useable area to gross vegetated area. Rainwater<br />

will be cleansed, stored in the basement and provide water <strong>for</strong><br />

toilets and irrigation <strong>for</strong> the living architectural features, an amenity to<br />

building occupants on every floor of the 26-story structure.<br />

If living architecture is to blossom as a practice this century, we also<br />

need to understand the full contribution that living systems offer —<br />

economic, social, psychological and environmental and ensure that<br />

these are reflected, rather than discounted in the marketplace.<br />

The vehicle <strong>for</strong> this change is through policies, regulations, and standards<br />

and investment. At a city-wide scale, we need to better understand<br />

the economic benefits of widespread living architecture in order<br />

to help facilitate the public resources required to fully support these<br />

developments. As our industry continues to rapidly grow, we can trans<strong>for</strong>m<br />

the building industry into a fundamental <strong>for</strong>ce <strong>for</strong> sustainability.<br />

<strong>Green</strong> <strong>Roofs</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Healthy</strong> <strong>Cities</strong> is dedicated to bringing about the<br />

rapid shift towards a living architecture and the creation of healing<br />

restorative buildings. Through this new publication, we will work<br />

tirelessly to bring you, our members, the latest in research, product<br />

developments, standards, tools, innovative designs and new policies<br />

that support your ability to make a lasting life-long contribution<br />

towards sustainable building.<br />

Sincerely yours,<br />

<strong>Living</strong> architecture is exemplified in Ken Yeang’s remarkable EDITT skyscraper<br />

in Singapore, designed from an ecological approach (pictured<br />

left). The building will be 55 per cent water self-sufficient, produce<br />

renewable energy and process wastewater. Captured rainwater is<br />

Steven W. Peck<br />

Founder and President<br />

LIVING ARCHITECTURE MONITOR WINTER

STRATA<br />

KUDOS<br />

PRIZE-WINNINGPROJECTS<br />

At <strong>Green</strong> <strong>Roofs</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Healthy</strong> <strong>Cities</strong>, we love to<br />

celebrate excellence in green roof and wall<br />

design — so our hats go off to the following individuals<br />

and organizations <strong>for</strong> their recent<br />

achievements:<br />

PRESERVINGSTORMWATERINPHILLY<br />

Pennoni Associates, a consulting engineering<br />

firm headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania<br />

won the award <strong>for</strong> Stormwater Best Management<br />

Practices <strong>for</strong> its green roof design on<br />

The Radian, located on Walnut Street in<br />

Philadelphia. The honors came from the<br />

Philadelphia Water Department, Offices of the<br />

Watersheds, a statewide program that recognizes<br />

innovative stormwater best management<br />

practices. The project, which integrates green<br />

roof areas into the public terrace level of a<br />

mixed-use facility that includes lower level<br />

retail space and a 13-story residential tower<br />

<strong>for</strong> student apartments, broke ground in Mary<br />

2007 and will open this August. The innovative<br />

strategy <strong>for</strong> stormwater management drains<br />

runoff from impervious areas of the roof into<br />

the green roof structure, maximizing water<br />

retention on the roof while controlling the<br />

release rate into two underground stormwater<br />

management basins. Additionally, the plant<br />

design of the green roof will serve as a valued<br />

amenity to residents and the community at<br />

large. Erdy McHenry <strong>Architecture</strong> was the<br />

project architect while <strong>Roofs</strong>capes, Inc. served<br />

as subconsultant to Pennoni and provided key<br />

technical expertise <strong>for</strong> the green roof design.<br />

GREENINGCALGARY<br />

On Nov. 1, 2007, the city of Calgary’s<br />

Mayor’s Urban Design Awards took place<br />

with eight winners and four honourable<br />

mentions in a variety of categories. A<br />

conceptual entry, Grey to <strong>Green</strong>: <strong>Green</strong>ing<br />

Calgary One Roof at a Time, was jointly<br />

submitted by Kerry Ross, an architectural<br />

consultant with IBI Group in Calgary and<br />

Kelly Learned of Cochrane, Alberta, earned<br />

an honourable mention and special acknowledgement<br />

by Juror Shannon Nichol<br />

of the international landscape architecture<br />

firm, Gustafson Guthrie Nichol. Their<br />

entry illustrated how a green roof on one<br />

of Calgary’s landmarks, the Municipal<br />

Building, could set the tone <strong>for</strong> the region<br />

in terms of becoming a green roof<br />

technology leader.<br />

BELOWThe award-winning Radian in Philadelphia was recognized <strong>for</strong> its innovative stormwater management strategy. “This project is an example of how ecology,<br />

economics and aesthetics can be balanced to satisfy not only the owner and the users of the building, but also broader environmental goals,” says Marc Morfei,<br />

Philadelphia senior landscape architect.<br />

Renderings: Erdy McHenry <strong>Architecture</strong><br />

COMINGUP<br />

The Toronto Botanical Garden will host a green roof conference on Feb. 21, 2008. The event’s<br />

conference workshops will cover design, plants, biodiversity and technical considerations. Paul<br />

Kephart of Rana Creek will be a speaker, as well as the instructor <strong>for</strong> GRHC’s Ecological Design<br />

Course to be held in the morning of Feb. 22, also at the Botanical Gardens. For in<strong>for</strong>mation<br />

about the event, please email greenroof@logistix.com or see their website at www.torontobotanicalgarden.ca/greenroof.<br />

Further in<strong>for</strong>mation and registration details about GRHC’s Ecological Design course on Feb. 22<br />

can be found at www.greenroofs.org<br />

NEWS<br />

WANTED!<br />

We want to hear about your<br />

announcements (deals and projects<br />

completed); people moves; awards;<br />

and books and events. Send us an email<br />

at editor@greenroofs.org and your<br />

news may end up in Strata <strong>for</strong> our next<br />

issue. Please include photographs or<br />

images if applicable.<br />

<br />

LIVING ARCHITECTURE MONITOR<br />

WINTER

THEGROWINGMEDIA&PLANTISSUE<br />

ALIVINGLABORATORY<br />

STUDENTSOFALLAGESAREGETTINGANEDUCATION—ANDLEARNINGWHATIT’SLIKE<br />

TOCONDUCTRESEARCHALONGSIDECOLUMBIAUNIVERSITYSCIENTISTSATOPA NEW<br />

YORKCITYMIDDLESCHOOL’STWOGREEN ROOFS<br />

Students at New York City’s Ethical Culture<br />

Fieldston School will soon be applying their<br />

science studies towards green roof research.<br />

The recent $75 million renovation of the middle<br />

school has incorporated green building<br />

design and two green roofs. Dr. Stuart Gaffin,<br />

associate research scientist at The Center <strong>for</strong><br />

Climate Systems Research at Columbia<br />

University in New York and Dr. Mathew<br />

Palmer, a lecturer with the Department of<br />

Ecology, Evolution and Environmental Biology,<br />

also at Columbia University, spearheaded the<br />

research and study of the two roofs, both different<br />

in purpose and design.<br />

Fieldston made available its two green roofs<br />

<strong>for</strong> Columbia’s research, which in turn will<br />

present unusual opportunities <strong>for</strong> the<br />

school’s science teachers from grades<br />

one through 12.<br />

“There are many different technological<br />

aspects to green building design but none of<br />

them offers the educational richness of green<br />

roofs,” says Gaffin, who is in charge of the<br />

research at the school’s top-level roof. “<strong>Green</strong><br />

roofs can be used to teach physics, climatology,<br />

hydrology, biology, ecology, chemistry<br />

and so on. One could never develop such a<br />

far-reaching curriculum, around say, solar<br />

panels or energy-efficient windows.” His own<br />

“ There are many different technological aspects to green building design but none of<br />

them offers the educational richness of green roofs. <strong>Green</strong> roofs can be used to<br />

teach physics, climatology, hydrology, biology, ecology, chemistry and so on.”<br />

Dr. Stuart Gaffin, research scientist, Columbia University<br />

research centers on the energy benefits of<br />

Fieldston’s green roof with New York’s energy<br />

and water issue needs in mind.<br />

Columbia’s research on the top-level roof is<br />

conducted using a weather tower, multiple<br />

sets of soil moisture and temperature probes,<br />

an albedometer and plant foliage temperature<br />

sensors. The albedometer consists of<br />

two back-to-back pyranometers, a device<br />

designed to measure natural sunlight radiant<br />

energy, manufactured by Kipp and Zonen.<br />

“With the data we are collecting and subsequent<br />

analysis, much of which will be done by<br />

the students, I hope we can produce findings<br />

<strong>for</strong> an ‘optimal’ green roof design that maximizes<br />

environmental benefits at the lowest<br />

cost,” explains Gaffin. “This will help spur<br />

their adoption by New York City and elsewhere.”<br />

The lower level roof of the school, planted in<br />

part by Fieldston’s students last October, was<br />

designed to be a more interactive site with<br />

three different types of plant communities. In<br />

addition to a traditional mix of Sedum<br />

species, two native, diverse grassland communities<br />

were planted. One of these communities<br />

was modeled on the Hempstead Plains,<br />

a prairie-like grassland from Long Island<br />

which has been almost completely lost due to<br />

urban and suburban development. The other<br />

native community is modeled on grasslands<br />

native to the Hudson Valley’s rocky hilltops<br />

with shallow soil, droughts and harsh wind, a<br />

climate very similar to that on the roof. Students<br />

will follow the success of the different<br />

plantings through time and will compare<br />

ecological processes like pollination and the<br />

development of the soil between the three<br />

plant communities.<br />

“If we can learn how to make native plant<br />

communities succeed on green roofs, it will<br />

add immensely to the value of those roofs as<br />

ecological restoration projects, habitat <strong>for</strong><br />

other species and living laboratories <strong>for</strong><br />

schools,” says Palmer.<br />

The students at Fieldston created a video<br />

detailing the building process of the second<br />

roof which can be viewed at www.ecfs.org <br />

By Lillian Mason & GRHC staff<br />

LIVING ARCHITECTURE MONITOR WINTER

STRATA<br />

GROUND-BREAKING<br />

SUSTAINABLESITES<br />

INITIATIVELAUNCHED<br />

ASLALADYBIRDJOHNSONWILDFLOWERCENTERAND<br />

OTHERSAREDEVELOPINGVOLUNTARYSTANDARDSFOR<br />

SUSTAINABLELANDUSEANDLANDSCAPINGPRACTICES<br />

The American Society of Landscape Architects<br />

(ASLA), the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower<br />

Center, the United States Botanic<br />

Garden, and other stakeholders are working<br />

under the umbrella of the Sustainable Sites<br />

Initiative to develop voluntary standards and<br />

guidelines related to sustainable land use and<br />

landscaping practices.<br />

The initiative was established to “identify the<br />

gold standards in sustainable landscape design<br />

and marry them to a practical, real-world<br />

approach so that designers, planners,<br />

builders, and developers can utilize them,”<br />

says Nancy Somerville, executive vice president<br />

and CEO of the ASLA.<br />

In a preliminary report published in November<br />

2007, a committee composed of 32 professionals<br />

practicing across a variety of landscape<br />

related disciplines identified a series of design<br />

goals and methods of achieving and monitoring<br />

a site’s ability to satisfy these objectives. The<br />

group further recommended integrated design<br />

strategies as a means to “harness natural<br />

processes to provide environmental benefits.”<br />

The guidelines are scheduled <strong>for</strong> release in<br />

May 2009 and will be incorporated into the<br />

USGBC’s LEED® system.<br />

For more in<strong>for</strong>mation or to participate in the<br />

review process visit www.sustainablesites.org.<br />

GREENGRID<br />

INSTALLS<br />

LARGEST<br />

MODULAR<br />

ROOFIN<br />

NORTH<br />

AMERICA<br />

A 2.3 acre modular green roof, the largest of<br />

its kind in North America, covers the new<br />

court at Upper Providence shopping center<br />

in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. The<br />

<strong>Green</strong>Grid® modules were installed in early<br />

2007 thanks to a joint venture between Gambone<br />

Development, Inc. and The Highland<br />

Development Group, Ltd.<br />

WASHINGTONDCSUPPORTSGREEN<br />

ROOFDEMONSTRATIONPROJECTS<br />

Through a grant from the District Department<br />

of the Environment, Watershed Protection<br />

Division, DC <strong>Green</strong>works, a<br />

preeminent green roof organization in the<br />

area, is subsidizing $3 per square foot of<br />

green roof demonstration projects.<br />

“This broadly available subsidy is generating<br />

a interest from a wider variety of developers<br />

than other incentives in the DC area.<br />

It is effectively helping mainstream building<br />

and land owners test out this progressive<br />

technology that wouldn’t otherwise have<br />

access to green roof funding,” says Sheila<br />

“This broadly available<br />

subsidy is…effectively<br />

helping mainstream<br />

building and land owners<br />

test out this progressive<br />

technology that wouldn’t<br />

otherwise have access to<br />

green roof funding.”<br />

Sheila Hogan, DC <strong>Green</strong>works, Washington, DC<br />

Hogan, executive director of DC<br />

<strong>Green</strong>works.<br />

In order to qualify an extensive or intensive<br />

project must be in D.C., can be new construction<br />

or retrofit, and on buildings with a<br />

footprint under 5,000 square feet or larger,<br />

in cases where the supporting structure<br />

was built prior to 1988. The program’s next<br />

deadline is February 15, 2008; others will<br />

be announced when determined.<br />

For further in<strong>for</strong>mation and the application <strong>for</strong>m<br />

visit: www,dcgreenworks.org.<br />

<br />

LIVING ARCHITECTURE MONITOR<br />

WINTER

GREENROOFSGO<br />

EXTREME—ANDPRIMETIME<br />

THEGROWINGMEDIA&PLANTISSUE<br />

It was Tuesday in April 2007 when<br />

Kelly Luckett got the call. A construction<br />

manager from the top show, Extreme<br />

Makeover Home Edition, asked if Luckett’s<br />

company, St. Louis-based <strong>Green</strong> Roof<br />

Blocks, could provide green roof modules<br />

<strong>for</strong> a green roof they were planning on a<br />

fully sustainable house they were building<br />

<strong>for</strong> a needy family in Pinon, Arizona on a<br />

Navaho Reservation. Luckett said he would<br />

be pleased to help, then came the kicker:<br />

the construction manager needed fully<br />

grown-out modules by that Sunday —<br />

just four days away.<br />

Under normal circumstances, it would take<br />

three to four weeks to deliver fully grown out<br />

modules, but Luckett was undeterred — even<br />

in the early spring. Saying yes, he quickly<br />

turned to his team on to the company’s research<br />

plots. “We could barely scrape together<br />

the number of square footage they<br />

needed — 200-modules, about 400 square<br />

feet in total,” he remembers. With plants<br />

ready, then came the real challenge — getting<br />

the modular plants, based in St. Louis, Missouri,<br />

to Pinon, Arizona — in just days. “No<br />

commercial freight carriers would commit to<br />

timelines, so we wound up putting it all into a<br />

rental truck and a staff member drove it<br />

across the country,” says Luckett.<br />

Luckett and his business partner both took<br />

time off to help out on the rapid installation<br />

of the green roof, bringing along their children<br />

<strong>for</strong> the once-in-a-lifetime experience.<br />

He was joined by another seasoned green<br />

roof professional, Dr. Bill Retzlaff, associate<br />

professor and chair of the Department of<br />

Biological Sciences Environmental Sciences<br />

Program at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville<br />

in Illinois.<br />

A hectic schedule, but well worth it, says<br />

Luckett, especially at the moment of the big<br />

“reveal” when the new house was unveiled<br />

<strong>for</strong> the worthy family. “It was a very emotional<br />

moment,” says Luckett, who, like every<br />

other contributor to the house, donated all<br />

his materials and time to make this dream<br />

house a reality <strong>for</strong> a very special family.

REVIEW<br />

TWISTINGNATURE<br />

Drawing on the works of artists dedicated to<br />

the use of natural materials — trees, wood,<br />

bamboo and pebbles — Alessandro Rocca’s<br />

Natural <strong>Architecture</strong> locates its readers at the<br />

intersection of art, architecture and ecology.<br />

The artists are all linked together by their desire<br />

to create incredibly complex installations<br />

while minimizing their effect on the environment<br />

in which they are created. Most employ<br />

basic artistic techniques and rely on manual<br />

labor to create awe-inspiring structures that<br />

will inevitably disintegrate but which raise lingering<br />

questions about our ways of inhabiting<br />

space. (Princeton Architectural Press, 2007)<br />

STRIKINGTHERIGHTBALANCE<br />

In an industry as new and multidisciplinary as<br />

the living architecture field, it is rare to get a<br />

project’s whole story. Not so anymore, Christian<br />

Werthmann’s <strong>Green</strong> Roof — A Case Study<br />

provides a comprehensive account of the<br />

American Society of Landscape <strong>Architecture</strong>’s<br />

green roof, in which Landscape Architects<br />

Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates<br />

and the Conservation Design Forum were<br />

charged with the task of maximizing both aesthetics<br />

and environmental per<strong>for</strong>mance. For<br />

the novice, the book demystifies every aspect<br />

of green roofing; <strong>for</strong> the seasoned professional,<br />

it allows <strong>for</strong> detailed examination of<br />

the design methodologies, construction techniques<br />

and maintenance practices employed<br />

to achieve these lofty goals. In an interview<br />

between the author and Van Valkenburgh,<br />

the designer placed emphasized the importance<br />

of striking the right balance. Hopefully,<br />

this book will help others do the same.<br />

(Princeton Architectural Press, 2007)<br />

ADAPTATION<br />

Ian McHarg, the author of the ecological design<br />

classic Design with Nature, has greatly<br />

trans<strong>for</strong>med the approach to and understanding<br />

of land-use planning and landscape architecture.<br />

Ian McHarg — Conversations with<br />

Students: Dwelling in Nature rearticulates the<br />

guiding principles of the “McHarg Method,”<br />

an interdisciplinary approach to land use design<br />

rooted in the notion that “creativity has<br />

permeated the evolution of matter and life,<br />

and actually is indispensable <strong>for</strong> the survival<br />

of the system.” He goes on to lay out the tools<br />

needed <strong>for</strong> the analysis and execution of<br />

“creative fitting,” a process driven by the<br />

theory that “any system is required to find<br />

of all environments the most fit, to adapt<br />

that environment, and to adapt itself.”<br />

(Princeton Architectural Press, 2007)<br />

BUSBY’SVISION<br />

Busby and Associates Architects are known<br />

<strong>for</strong> buildings that combine a Modernist aesthetic<br />

with environmentally responsive and<br />

integrated design strategies. Busby: Learning<br />

Sustainable Design profiles twelve of the<br />

firm’s projects (which coincidentally draw<br />

upon the theoretical framework of Ian<br />

McHarg’s Design with Nature), highlighting<br />

their contribution to the development of new<br />

green building per<strong>for</strong>mance standards. The<br />

book, produced in collaboration with heavyweights<br />

David Suzuki (<strong>for</strong>eward) and editors<br />

Jim Taggart and Kathy Wardle, will serve the<br />

interests of those interested in the theory,<br />

practice and direction of the sustainable<br />

design industry, especially the need <strong>for</strong> multidisciplinary<br />

collaboration. As Taggart notes:<br />

“Optimizing per<strong>for</strong>mance depends on a critical<br />

appreciation of the interdependence of structure,<br />

<strong>for</strong>m, envelope design and environmental<br />

systems.” (Janam Publications Inc., 2007)<br />

By Flavia Bertram

Photos courtesy Elisabeth Whitelaw<br />

ONTHEROOFWITH…<br />

CORNELIAHAHNOBERLANDERCMFCSLAFASLA<br />

By Caroline Nolan<br />

Cornelia Hahn Oberlander, born in Germany in 1924, obtained a BA<br />

from Smith College in 1944 and was one of the first women to<br />

graduate from Harvard University’s School of Design with a degree in<br />

landscape architecture in 1947. She worked with Louis I. Kahn and<br />

Oscar Stonorov in Philadelphia, and landscape architect Dan Kiley in<br />

Vermont, be<strong>for</strong>e moving to Vancouver to establish her own practice in<br />

1953, Cornelia Hahn Oberlander Landscape Architects.<br />

Her career is legendary.<br />

The 84-year-old is well-known <strong>for</strong> such extraordinary, pioneering works<br />

including “Robson Square” — the provincial government courthouse<br />

complex in Vancouver, a three-block green roof designed in collaboration<br />

with the architect Arthur Erickson (1974–81); the National Gallery<br />

of Canada, with architect, Moshe Safdie; University of British Columbia’s<br />

(UBC) Museum of Anthropology, also with Arthur Erickson<br />

(1975–76); the Canadian Chancery in Washington DC, also with Arthur<br />

Erickson (1989); the spectacular 28,000 square-foot semi-intensive<br />

roof on Moshe Safdie’s Vancouver Public Library (1995); and the Northwest<br />

Territories Legislative Assembly Building in Yellowknife, Canada<br />

with Matsuzaki Wright Architects and Gino Pin Architects (1995).<br />

She has received numerous awards including the prestigious Order of<br />

Canada in 1990; several honorary degrees from University of British<br />

Columbia (UBC), Simon Fraser University, Ryerson University and<br />

Smith College; a commemorative Medal <strong>for</strong> the 125th Anniversary of<br />

the Confederation of Canada in 1992; the Royal Architectural Institute<br />

of Canada Allied Medal in 1995; and an honorary membership to the<br />

Architectural Institute of BC as well as life membership in the British<br />

Columbia Society of Landscape Architects.<br />

Cornelia, a true pioneer of socially conscious and sustainable<br />

landscape design, has collaborated with internationally acclaimed<br />

architects, including Renzo Piano on public projects in the United<br />

States and Canada. We caught up with Oberlander in Vancouver<br />

late last year.<br />

LIVING ARCHITECTURE MONITOR WINTER

ONTHEROOFWITH…<br />

Q: The Germans have a wonderful sense of stewardship <strong>for</strong> nature<br />

and, indeed, created the green roof concept in the first place.<br />

Do you feel your heritage has influenced your work?<br />

A: Well, when I was 15, we landed in New York from Germany in<br />

1939, be<strong>for</strong>e the war, because my mother thought it was <strong>for</strong> us. A<br />

year and a half later, she came down from breakfast one day and<br />

said to me and my sister, ‘This place is too materialistic <strong>for</strong> you girls<br />

— all you are thinking about is sweaters and skirts. When you come<br />

new to a country you have to till the soil.’ She then whisked us in<br />

our wooden-bodied Ford Station wagon up to northern New Hampshire<br />

and that’s where I grew up. She was trained as a horticulturalist<br />

and created a Victory Garden to grow vegetables during the war<br />

and so, that’s how I grew up.<br />

Q: You have practiced “living architecture” be<strong>for</strong>e the term even<br />

existed — what does the term mean to you now?<br />

A: <strong>Living</strong> architecture means that the building is healthy and the land<br />

is healthy and that you are contributing to the biomass of the city,<br />

namely to make the air cleaner. I feel that if you have chosen the<br />

profession of landscape architecture, you have a duty to listen to what<br />

the times bring. It’s not what I was taught at Harvard way back when,<br />

necessarily, but all about what we must make of the land today. I’ve<br />

always looked to the future.<br />

Q: How has landscape architecture profession changed since you<br />

established your own practice in 1953?<br />

A: Well, the industry was non-existent then. You hoped <strong>for</strong> the best,<br />

that the building wouldn’t fall down! But I was already at Harvard realizing<br />

I could not work in a vacuum — that I would have to work in collaboration<br />

with architects.<br />

Q: Early in your career, did you ever imagine you would ever see the<br />

mainstreaming of green roofs as is happening now?<br />

A: Well, I had hoped it would happen. The municipal bylaws and the<br />

building bylaws of every city must include green roofs. We have not<br />

reached this goal yet.<br />

MOSHESAFDIE’SVANCOUVERPUBLICLIBRARY<br />

Q: You are retrofitting one of your most important and noted<br />

projects, Vancouver’s Robson Square — what is being done and why?<br />

A: Well, after 35 years it was time. In 1976, the waterproofing membrane,<br />

or EPDM, was guaranteed <strong>for</strong> 20 years, and it lasted <strong>for</strong> 35<br />

years. So that had to be renewed, but on top of that, the province of<br />

British Columbia demanded seismic upgrading <strong>for</strong> the whole building,<br />

and so this is being done at present and with it, came an in-depth<br />

analysis of the plant materials which were possible to keep. We lifted<br />

out several 8,000-pound Japanese Maple Trees among others, took<br />

them to a nursery and brought them back last spring and then planted<br />

them in exactly the same location as be<strong>for</strong>e.<br />

Q: What were some of the challenges you encountered with your<br />

design of the green roof on Vancouver’s Library Square Building?<br />

A: I don’t work with soils, so I knew already in 1976 I knew that I could<br />

only have a lightweight growing medium <strong>for</strong> the roofs <strong>for</strong> the Robson<br />

Square installation. So <strong>for</strong> the Library Square, I researched at great<br />

length how could I get a lightweight growing media and I came upon<br />

the idea to collect all the vegetable food waste from the restaurants in<br />

Vancouver and have them process it into compost. The final mix is<br />

one-third compost from vegetable food waste, one-third pumice and<br />

one-third sand: it’s called the Library mix — and we will use it at Robson<br />

Square again, so the challenge was to talk the owners into allowing<br />

us to use this lightweight material.<br />

“I feel that if you have chosen the profession<br />

of landscape architecture you have a duty to<br />

listen to what the times bring...I’ve always<br />

looked to the future.”

THEGROWINGMEDIA&PLANTISSUE<br />

Q: Looking ahead, what changes do you see?<br />

A: Well, first of all, we must curb this desire to sprawl. We must limit<br />

our footprints and employ the principles of ecodensity — that’s number<br />

one. Number two: we must use every bit of ground <strong>for</strong> public parks and<br />

not give it away to developers. Number three: if we want living buildings,<br />

we must work together as a team of architects, engineers, landscape<br />

architects.<br />

Q: As a landscape architect, how do you feel about the emergence of<br />

green walls?<br />

A: I think it is very good idea because they insulate the building against<br />

the cold and heat but they have to be built with drip irrigation. But I<br />

would like to speak to you about wildlife.<br />

Q: Please do...<br />

A: Well, we must build with a holistic approach, <strong>for</strong> example, it is important<br />

to include the Canada Geese, and all the other birds that flock<br />

around. Let them have fun on the roof!<br />

Q: Canada Geese on a roof?<br />

A: Yes. On the Library roof, I have two nice Canada Geese couples,<br />

(you know they mate <strong>for</strong> life), which come to certain balconies of the<br />

Court House, <strong>for</strong> instance, but the judges aren’t too happy with this<br />

and have asked <strong>for</strong> them to be removed — so I have not educated<br />

everyone yet! On the roof of the Vancouver Library, an inaccessible<br />

roof, I have two more sets of Canada Geese that sit on the roof and<br />

have their children and then they fly away and return every year. So<br />

education is necessary <strong>for</strong> a holistic approach that allows humans and<br />

geese to be part of the urban landscape.<br />

Q: If you could impart one kernel of wisdom to other professionals<br />

in this field, what would it be?<br />

A: Think about climate change which concerns all of us and what we<br />

have done to this planet. Learn what we can do and with every project<br />

to lessen the impact on the environment. <strong>Green</strong> roofs increase<br />

biomass, insulate buildings against heat and cold and slow down<br />

stormwater runoff, if they’re constructed properly. You can do this<br />

only if you have done your research and if you are working with<br />

professionals who know how to implement these ideas with working<br />

drawings and specifications.<br />

Q: A perfect ending — thank you <strong>for</strong> your wonderful visions and work. <br />

Caroline Nolan is the editor of the <strong>Living</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong>.

PROJECT<br />

ISLANDP<br />

<br />

LIVING ARCHITECTURE MONITOR<br />

WINTER

THEGROWINGMEDIA&PLANTISSUE<br />

PROJECTSPECIFICATIONS<br />

LOCATION Thousand Islands, Ontario<br />

PROJECTTYPE New Construction<br />

GREENROOFSIZE 1,700 square feet<br />

COMPLETIONDATE 2002-2003<br />

YEAROFAWARD 2004<br />

CLIENT/DEVELOPER Carol and Kevin Reilly<br />

ARCHITECT Shim-Sutcliffe Architects (Winner)<br />

DESIGNCONSULTANT Mill & Ross Architects<br />

DESIGNCONSULTANT Donald Chong Studio<br />

STRUCTURALENGINEERSBlackwell Engineering<br />

MECHANICALENGINEERSToews Systems Design (Mechanical)<br />

CONTRACTOR Michael Sheedy and Mark Peabody<br />

GREENROOFDESIGNER Marie-Ann Boivin, Soprema Canada<br />

GREENROOFLANDSCAPECONTRACTOR Top Nature, Montreal<br />

ARADISE<br />

By Flavia Bertram<br />

LIVING ARCHITECTURE MONITOR WINTER

PROJECT<br />

The majority of green roof projects are located in highly developed<br />

areas, characterized by limited green space, a searing urban heat<br />

island effect, stormwater management issues, and as such, often used<br />

to mitigate these negative effects of urbanization. Not so in the case<br />

of the 2004 Award of Excellence winning Howe Island home on the<br />

St. Lawrence River in the Thousand Islands, Ontario.<br />

The once rural, now semi-suburban island has a history of dairy farming<br />

and is not subject to the same environmental problems as city<br />

centers. As a result this green roof project was driven by aesthetics<br />

rather than the environmental benefits of the technology.<br />

Shim-Sutcliffe Architects conceived the house with the intent of<br />

The upper semi-intensive roof transposed the meadow plants from<br />

the ground to the roof, thereby integrating the building with the<br />

landscape. This visual effect is facilitated by the omission of parapet<br />

walls, resulting in roof perimeter details like those usually found<br />

on sloped rather than flat roofs. Six-inch deep growing medium sits<br />

on top of a modified bitumen membrane and root repellent layer<br />

and is contained by borders, which are then surrounded by stone<br />

vegetation-free zones to prevent the occurrence of plant erosion.<br />

Prior to construction, and to reinvigorate the large meadow, the<br />

five-acre site was hydroseeded (a process where a slurry of seeds<br />

and mulch is sprayed over a targeted area) with clover and a mixture<br />

of local indigenous flowers. The clover was harvested and<br />

respecting the region’s agrarian tradition and maintaining the openness<br />

of the landscape while providing their clients with privacy and a<br />

splendid view of the river. The green roofs, designed with Soprema<br />

Canada, were one of many elements that contributed the project<br />

goals of balancing the landscape, structure and water. On the side<br />

facing the St. Lawrence River the house opens up to a large water<br />

garden with indigenous water lilies and bulrushes.<br />

Initially, the two roofs did not utilize the same vegetation. The<br />

lower extensive roof was planted with a more traditional sedum<br />

palette, including Sedum album, Sedum floriferum ‘Weihenstephaner<br />

Gold’, Sedum kamtschaticum ellacombianum and Sedum<br />

Spectabile ‘Brilliant’.<br />

“The green roof is part of<br />

larger vision <strong>for</strong> landscape;<br />

it is one part of a greater<br />

approach to the agrarian<br />

context of the island.”<br />

Brigitte Shim, Shim-Sutcliffe Architects<br />

<br />

LIVING ARCHITECTURE MONITOR<br />

WINTER

THEGROWINGMEDIA&PLANTISSUE<br />

trans<strong>for</strong>med into bales of hay by a local farmer, continuing the<br />

site’s tradition of contributing to local agriculture.<br />

This same blend was subsequently used in the field of the upper<br />

roof of this island paradise, which was then bordered by sedums.<br />

This connection between the roof and the ground, however, proved<br />

to be problematic <strong>for</strong> the semi-intensive roof’s maintenance. The<br />

original plant-selection (comprised of French hybrids) were quickly<br />

overrun by native Canadian weeds and wildflowers. Though the area<br />

was reseeded after the establishment period was complete, the<br />

maintenance was certainly more than the client had bargained <strong>for</strong>.<br />

During the design phase, it became apparent to both the architects<br />

Both roofs have been annually supplemented with two or three flats<br />

of sedum to ensure continuous plant coverage.<br />

Despite this alteration, the striking Howe Island green roof continues<br />

to be an example of site-specific design that is sensitive to the visual<br />

and cultural aspects of the surrounding environment. The clover<br />

meadow and the two green roofs compliment each other, blurring the<br />

borders of the building roof and the ground plane. <br />

Flavia Bertram is a research assistant with <strong>Green</strong> <strong>Roofs</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Healthy</strong> <strong>Cities</strong> in<br />

Toronto. She is also a contributor to a new book published by <strong>Green</strong> <strong>Roofs</strong><br />

<strong>for</strong> <strong>Healthy</strong> <strong>Cities</strong> and Schiffer Publishing called Stretching the Boundaries<br />

of <strong>Green</strong> Roof Design and <strong>Living</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong>: Five Years of Award-Winning<br />

“Once we<br />

got the right<br />

plants on<br />

the roof it<br />

became easy<br />

to handle.”<br />

Carol Riley, owner & client<br />

and manufacturer that the several-hours-by-car distances from the<br />

nearest centers of green roof knowledge in Canada —Toronto and<br />

Montreal — were too far <strong>for</strong> maintenance personnel to travel. As a result,<br />

the owners and a local gardener were trained in basic maintenance<br />

procedures and bore the responsibility <strong>for</strong> them. This capacity<br />

development is in keeping with the projects goals of respecting the island<br />

and surrounding area’s existing tradition of agrarian self-reliance.<br />

However, this independence also necessitated that the labour required<br />

in its upkeep be limited and resulted in the replanting of the<br />

upper roof with low maintenance drought resistant sedum species.<br />

Similarly, plants on the lower roof were redistributed after the establishment<br />

period was over in order to create a stronger plant palette.<br />

Projects in the spring. In the book other <strong>Green</strong> Roof Awards of Excellence<br />

winning projects and individuals are recognized <strong>for</strong> demonstrating extraordinary<br />

leadership and are celebrated <strong>for</strong> their valuable contribution to the<br />

green roof industry. This case study is but one of many featured in this exciting<br />

book, which will be launched at the upcoming annual GRHC conference<br />

in Baltimore in April. Please see www.greenroofs.org <strong>for</strong> details.<br />

INTERESTEDINHAVINGYOURPROJECTPROFILEDHERE?<br />

We are currently seeking excellent and innovative green roof and green<br />

wall projects <strong>for</strong> in-depth case studies <strong>for</strong> future “Project” consideration.<br />

Tell us about yours by sending an email to editor@greenroofs.org.<br />

It would be helpful to include a few photographs.<br />

LIVING ARCHITECTURE MONITOR WINTER

BESTPRACTICE<br />

THEORGANIC<br />

QUESTION<br />

WHENITCOMESTOGROWINGMEDIATHEREISCONSID-<br />

ERABLEDEBATEASTOWHATEXACTLYCONSTITUTESTHE<br />

BESTMIXFORSUPERIORPERFORMANCE<br />

On any green roof project, there inevitably comes a time when<br />

professionals must answer a crucial question: Exactly what kind of<br />

growing media is best <strong>for</strong> the roof’s long-term per<strong>for</strong>mance?<br />

In North America, much research is still required to determine the<br />

optimal composition of growing media and a wide variety of opinions.<br />

Currently, many green roof professionals are grappling with<br />

the issue of organics versus non-organic materials in growing media.<br />

Here, we present just two of those opinions from two, respected<br />

industry professionals, both members of <strong>Green</strong> <strong>Roofs</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Healthy</strong><br />

<strong>Cities</strong>’ Growing Media Sub-Committee which is developing per<strong>for</strong>mance<br />

standards <strong>for</strong> growing media: Chuck Friedrich and Rick Buist.<br />

Rick Buist is a horticulturalist and president of BioRoof Systems<br />

Inc. and chair of the GRHC Growing Media Sub-Committee.<br />

Chuck Friedrich is also a horticulturist — and landscape architect —<br />

and is the director of horticulture research and product development<br />

<strong>for</strong> Carolina Stalite Company in Salisbury, North Carolina. He is<br />

also a member of the American Society of Landscape Architects, NC<br />

Landscape Contractors Association, and ASTM <strong>Green</strong> Roof Subcommittee.<br />

He also sits on the ASTM <strong>Green</strong> Roof Task Committee.<br />

<br />

LIVING ARCHITECTURE MONITOR<br />

WINTER

THEGROWINGMEDIA&PLANTISSUE<br />

“DON’TCALLITDIRT!”<br />

By Chuck Friedrich, RLA, ASLA<br />

My college soil science professor always reprimanded the class<br />

<strong>for</strong> referring to soil as “dirt.” He would always say: “dirt is<br />

something that is tracked in onto the carpet.” Actually the ideal<br />

green roof growing media should NOT contain any natural soil;<br />

there<strong>for</strong>e, we should not even call it soil. Most green roof professionals<br />

prefer the term growing media or medium, substrate, or<br />

planting media. My definition <strong>for</strong> green roof media is: “the particulate<br />

matter or substrate that anchors the plant roots to sustain plant<br />

growth.” Sounds simple, but it can get very complicated.<br />

For proper terminology, we should refer to the growing media as<br />

intensive or extensive green roof media. The media should be designed<br />

<strong>for</strong> the physiology of the plant material growing in the media.<br />

Sedums require an extensive media that has a coarser gradation than<br />

those used <strong>for</strong> grasses or other non-succulents. In addition to plant<br />

material, other factors affecting media selection are climate, weight,<br />

fertility, depth, location, microclimate, and irrigation. With all these<br />

factors to contend with we can then add a bunch of engineers to the<br />

equation. Over the past 15 years I have supplied green roof media on<br />

over 140 green roofs. It has been a learning experience offering much<br />

success. (Having a German last name didn’t hurt.)<br />

LOSINGORGANICMEDIA<br />

Trees, shrubs, lawns and flowers need water, air, space <strong>for</strong> the roots,<br />

and nutrients. Within the proper microclimate, many plants can<br />

grow better on the roof than on the ground. Why? With a green roof<br />

we can create a very big pot filled with the perfect growing media<br />

that is fertilized, irrigated, and most important, well drained. What<br />

we don’t want is a natural soil or a 100 per cent organic mixture<br />

GOINGFORORGANICS<br />

By Rick Buist<br />

When considering the writing of this best-practices article on<br />

using organics in growing medium, I reflected on the experiences<br />

I have had in the green roof marketplace to date. Since first becoming<br />

aware of the green roof industry, I had numerous people tell<br />

me how you shouldn’t use more than a certain percentage of organics<br />

in the growing medium. One says five per cent, another 20 per cent,<br />

and yet others argue it would be best if there were no organics at all!<br />

Now at the time, I found this all rather odd. Our company has many<br />

successful installations (over 80 to date) with few observed problems,<br />

and our sister company has been producing millions of cubic meters of<br />

organic-based growing mediums <strong>for</strong> decades to the nursery industry.<br />

Then I was told that our organic growing medium projects we installed<br />

did not have a long enough track record to be sufficiently evaluated.<br />

“Just you wait,” they ominously warned, ‘eventually the organic growing<br />

medium will disappear — it’ll be a disaster.” One person even<br />

claimed they had pictures of a green roof we installed showing exposed<br />

roots — impending doom was just around the corner!<br />

So I took all of this great advice to heart and also personally visited the<br />

site in question, only to discover the growing medium depth had not<br />

changed in four years. The roots were not exposed (although clumping<br />

fescues could give that appearance) and the owners were very happy.<br />

Naturally I had to ask myself: Why the strident accusations against organics<br />

in growing mediums?” Is it because some have invested in proprietary<br />

products associated with growing mediums? Is it because of the European<br />

experience? Or do they really have a sound scientific argument?<br />

LIVING ARCHITECTURE MONITOR WINTER

BESTPRACTICE<br />

contained up on a giant frying pan in the sky. Natural soils are<br />

cohesive and can change over a long period of time or simply get<br />

“damaged” if installed when wet. The same is true with organic<br />

matter; though it is a very important component, too much organic<br />

can be problematic depending on the circumstances.<br />

Organic matter breaks down and is washed out of the system due to<br />

rain or irrigation; to replace lost material could require many trips<br />

with heavy bags up steps or an elevator. The use of natural soil or too<br />

much of the wrong type of organic amendment may produce finer<br />

particles. Fine particles can move down and accumulate on the filter<br />

fabric, slowing down drainage. I have not been a big fan of sewage<br />

sludge compost <strong>for</strong> this reason. Runoff from green roofs containing<br />

levels of nutrients is a topic of current discussion with water quality<br />

researchers.<br />

The best practice is to use a media that will provide enough air<br />

throughout the profile to promote the roots to go down instead of<br />

up. If the bulk of roots are down deeper in the media where it is<br />

cool and moist, the better the plant can sustain itself during periods<br />

of extreme temperature.<br />

When proportionally blended, a mixture of lightweight aggregate,<br />

quality sand and organic compost makes a good media <strong>for</strong> intensive<br />

green roofs. 3/8" and finer lightweight aggregate has pore spaces in<br />

Throughout the horticultural and landscape industry, organics are the<br />

overwhelming trend. The industry has embraced organics’ role in sustaining<br />

biological functions in the soil. Research is abundant, covering<br />

actinomycetes, nematodes, micchorhizal fungi and various other microand<br />

macro-organisms (let’s not <strong>for</strong>get the lowly earthworm) — all of<br />

which bind contaminants, cycle nutrients, suppress disease and more.<br />

So once again, I asked myself: With this track record and research going<br />

on, why are many in the green roof world so opposed to using organics?<br />

If I were to ignore the obvious implications <strong>for</strong> those who have<br />

invested in distribution rights <strong>for</strong> European based systems, I would<br />

have to turn to the science behind the German Standards developed<br />

by the nonprofit known as Forschungsgesellschaft Landschaftsentwicklung<br />

Landschaftsbau (or FLL). I spent considerable time reviewing the<br />

FLL Standard and the research that led to its’ very conclusions.<br />

I also considered it imperative to understand the initial terms of reference<br />

and historical context by which the need <strong>for</strong> the standards<br />

came about. The terms of reference weighed very heavily on avoidance<br />

of problems, which given some of the failures in the German<br />

marketplace at the time, seemed to make sense. Un<strong>for</strong>tunately, I do<br />

not have enough article space to get into everything that I found;<br />

however, there are some serious holes.<br />

The first of which is the way the Standard does not adequately<br />

distinguish between organics (this may be because the science of soil<br />

biology was out of fashion at the time, research focused instead on<br />

the science of chemistry — much better funding opportunities).<br />

When referring to organics, there must be awareness that there is a<br />

huge array of source stock, composting processes, characteristics,<br />

etc…which makes it impossible to generalize. No one would suggest<br />

that we should refer to the entire automotive world as being all the<br />

same. Is a skateboard the same as an F1 racing car? That’s absurd. It is

THEGROWINGMEDIA&PLANTISSUE<br />

“Organic matter breaks<br />

down and goes away; to<br />

replace lost material could<br />

require many trips with<br />

heavy bags up steps or<br />

an elevator.”<br />

Chuck Friedrich<br />

the particles which lighten the load, retain nutrients and water, and<br />

best of all it is permanent. A good quality graded sand as filler is<br />

good <strong>for</strong> stability, and a measured amount of the proper organic<br />

compost provides microbial activity that is beneficial to the biology<br />

of the media. Currently, there are no standards related to the use of<br />

compost on green roofs.<br />

What about fertilizer? Save it <strong>for</strong> planting time. There is absolutely<br />

no reason to add fertilizer to a green roof media during the blending<br />

process. For good reason, in most cases the media is installed<br />

months be<strong>for</strong>e the first plant is installed. There<strong>for</strong>e, why spend<br />

money on fertilizer that will only end up leaching out and down the<br />

drain be<strong>for</strong>e the plants show up on the job? The best method is to<br />

blend a good slow release fertilizer into the top layer of the media<br />

during the planting operation.<br />

Once planted, provide lots of maintenance and irrigation; with that<br />

it can be beautiful and last <strong>for</strong> several decades. I <strong>for</strong>got to mention,<br />

also add lots of money, you get what you pay <strong>for</strong>. If you can keep the<br />

general contractor and schedule in check, the process can actually<br />

go smooth, right? Wrong. Don’t <strong>for</strong>get about the engineer.<br />

AWEIGHTYSUBJECT<br />

I am amazed how the specification on the weight of the media can<br />

be so tight, while in the same specification, the plan calls <strong>for</strong> 14<br />

Oak trees to be planted. It tickles me when I am asked at least<br />

twice per month by designers, “how much does a full grown tree<br />

weigh?” What? Dogwood or Sequoia? Does an additional pound or<br />

two per cubic foot of media, one way or another, make that much<br />

of a difference? I guess it will when 350-pound Aunt Bertha and<br />

the twins decide to have lunch up on the roof.<br />

All kidding aside, weight is an issue, especially on retrofitted extensive<br />

roofs. It is important to design using the saturated weight of the<br />

media. The ASTM Sub-committee <strong>for</strong> <strong>Green</strong> <strong>Roofs</strong> has developed<br />

standards <strong>for</strong> the practice and test methods <strong>for</strong> the determination<br />

almost as absurd to consider all organics to be the same. There are<br />

some organics that I would never use on a green roof (some of which<br />

were used in the research behind the FLL Standard). From cellular<br />

structure to composting process and beyond, organics are far too complex<br />

to generalize within a Standard.<br />

Secondly, the FLL Standard dictates organic content by mass. I can<br />

understand why, since the dominant testing method <strong>for</strong> organic content<br />

is the burn method, which can only measure by mass. However, by doing<br />

so, the Standard leaves a lot open to interpretation. For instance, one<br />

can use an extremely heavy inorganic material to achieve a high percentage<br />

of organic content since organics are generally much lighter. I was<br />

able to achieve organic content of over 60 per cent by volume in the<br />

growing medium but only eight per cent by mass. Was this ambiguity<br />

intended by the Standard?<br />

Interestingly, contrary to what I heard in the industry, the FLL Standard<br />

did allow <strong>for</strong> higher levels of organics. Section 9.2.2 states: “A greater<br />

proportion of organic matter may be required where special <strong>for</strong>ms of<br />

vegetation, such as humus rooting plants, are used.” This shows the<br />

importance of matching the growing medium to the physiological<br />

needs of the plants, another area largely uninitiated by many suppliers<br />

in our industry.<br />

Thirdly, the Standard focused on material specifications instead of<br />

per<strong>for</strong>mance specifications and by doing so, essentially closed the<br />

door on innovation. (It seems the lowly sedum is the order of the day,<br />

matched to equally low per<strong>for</strong>mance mediums). This caused companies<br />

to scramble to find similar products in North America with the<br />

prize going to those who could quickly identify and corner the market<br />

on certain products. As most of the construction industry in North<br />

America makes the change to per<strong>for</strong>mance-based specifications, the<br />

FLL Standard represents a step backward.<br />

Lastly, I concluded the Standard itself was not as much a problem<br />

as people’s interpretation of it. For example; there seems to be much<br />

misunderstanding of what organic content is. One hundred per cent<br />

FORMULATING, TESTING, PLANT<br />

GROWTH TRIALS, PROBLEM SOLVING<br />

“SEND US YOUR<br />

EXTENSIVE/INTENSIVE 5<br />

GALLON PAIL PLEASE!”<br />

SOIL CONTROL LAB<br />

42 HANGAR WAY<br />

WATSONVILLE, CA 95076<br />

(831) 724-5422 PHONE,<br />

(831) 724-3188 FAX,<br />

WWW.GREENROOFLAB.COM<br />

FRANK@COMPOSTLAB.COM<br />

CONTACT: FRANK SHIELDS

“Why the strident<br />

accusations against<br />

organics in growing<br />

mediums? Is it because<br />

some have invested in<br />

proprietary products<br />

associated with growing<br />

mediums? Is it because<br />

of the European experience?<br />

Or do they really<br />

have a sound scientific<br />

argument?”<br />

Rick Buist<br />

organic material may only have an end organic content of 20 per cent.<br />

The remaining 80 per cent may be inorganic or mineral based. This is<br />

largely lost in the language of the industry.<br />

The per<strong>for</strong>mance which organic matter brings to stormwater retention,<br />

pollutant degradation, plant variety, cooling benefits, sustainable materials,<br />

etc. is too great to ignore.<br />

Organic-based growing media can hold far more water than mineralbased<br />

growing mediums while maintaining porosity; this is because of<br />

the way in which they hold water through particle swelling instead of just<br />

void filling and capillary <strong>for</strong>ces. Biology can be customized to degrade

THEGROWINGMEDIA&PLANTISSUE<br />

of dead loads and live loads associated with green roof systems. If<br />

flooded, the media weight could increase up to 20 pounds over the<br />

drained weight. This could be catastrophic when a heavy snow load<br />

is added to roof during the same event.<br />

MEDIAFORSEDUMS<br />

Most extensive growing media is used in a thin profile of three to six<br />

inches. If weight restrictions allow; go deeper, just keep Aunt Bertha<br />

off the roof.<br />

Sedums do well in aerated media. Most extensive media is at least<br />

80 per cent lightweight aggregate (<strong>for</strong> porosity and nutrient retention).<br />

Care must be taken not to design a growing media that is too<br />

fine. If the media does not routinely dry out, excessive water may<br />

cause weed promotion and some sedum roots to rot.<br />

Sedums will die quicker if the media stays too wet rather than<br />

too dry. In my view, it is better to provide a well-drained material<br />

with supplemental irrigation then to have plant loss during the<br />

rainy season.<br />

SPEAKINGOFIRRIGATION<br />

Those who think extensive green roof systems do not need, at least<br />

temporary irrigation ought to camp out on a green roof in North<br />

Carolina during an August heat wave. I have run several studies in<br />

NC and have been able to just get by without automatic watering.<br />

That success ended with this year’s record drought. No matter how<br />

fine the media was or the amount of organic content in the mix, the<br />

sedums still died from lack of moisture. Without the morning mist<br />

experienced daily in Germany and the Pacific Northwest, sedums<br />

have a tough time in hotter and drier climates. Though sedums may<br />

go dormant and survive a green roof that looks like dead weeds is<br />

bad <strong>for</strong> business. Find a water source, reclaimed if you must, and<br />

find a way to get it up on the roof. Do not over water; monitoring irrigation<br />

after the establishment period is essential. The controversy<br />

over irrigation will continue; occasional drip irrigation as needed<br />

works. The holdouts need to quit bellyaching and just do it.<br />

In conclusion, controversy between schools of thought over green<br />

roof media will continue within the United States. Being in its infancy<br />

compared to Europe, whether intensive or extensive, communications<br />

between the parties involved do tend to drift. When everyone<br />

with professional integrity and the proper knowledge work together<br />

and stay current with the latest technology, the long-term results will<br />

benefit everyone. <br />

specific and non-specific pollutants. Plants that provide evaporative<br />

cooling can be used more frequently with success. Fertilization can<br />

occur naturally through nutrient cycling. Materials can be sourced<br />

locally. And the list of benefits goes on.<br />

Practically every argument I have heard against the use of organics<br />

comes with a relatively easy solution:<br />

• Lost depth because of organic cycling is easily addressed through<br />

inputs such as biomass created by the plant choice through roots<br />

or refuse, or annual (if required at all) top-dressing with a<br />

pelletized product such as compost or alfalfa (readily available<br />

in dry, bagged <strong>for</strong>m).<br />

• Fines clogging drains or water-logging can be averted by careful<br />

selection of organic materials. Organics with crystalline structures,<br />

such as certain bark-based products, will behave much like sand <strong>for</strong><br />

free drainage, while organics with strand characteristics will hold<br />

structure together. Careful selection and installation of components<br />

such as filter cloth are also helpful.<br />

• Wind erosion is averted by using biodegradable netting until plants<br />

are established, thereby providing continuous cover.<br />

• Fire prevention can be improved by avoiding certain substances<br />

(i.e. peat moss — a limited resource) and by using organics with<br />

high ignition-thresholds and large moisture-retention capacities.<br />

Although any biomass on a roof can burn, it is easy to mitigate the<br />

risk by paying attention to the details.<br />

My intention in promoting the use of organics is not to replace<br />

the good work already achieved by the FLL Standard (the bulk of<br />

which I strongly endorse), but to expand its terms of reference. We<br />

should not be afraid of opening the door to creativity. Let’s set<br />

per<strong>for</strong>mance objectives that will not only serve to reduce risk but<br />

also allow <strong>for</strong> innovation.<br />

We should also practice what we preach. If we as an industry are<br />

promoting stormwater retention or cooling benefits, we must prescribe<br />

a high level of per<strong>for</strong>mance to justify the cost of our product. If<br />

not, we risk being passed off as a fad, as eco-chic. Are we environmental<br />

stewards? Don’t we appear hypocritical by using mined products<br />

<strong>for</strong> the bulk of our material? If we’re pushing the idea of biodiversity,<br />

we must use plantings that give entomological teeth to our argument.<br />

An immature marketplace is always better served by collaboration<br />

than by competition. We risk alienating an extremely large demographic<br />

in the landscape, horticultural and composting industries who<br />

could help our industry immensely if we continue to promote against<br />

the use of organics. <br />

LIVING ARCHITECTURE MONITOR WINTER

NATIVEPLANTRESEARCH<br />

IMPACTOFGROWINGMEDIA<br />

ON PRAIRIEGRASSES<br />

RESEARCHFROMLINCOLNNEBRASKAPROVIDESINSIGHTONTHEPERFORMANCEOF<br />

GROWINGMEDIAINTHEESTABLISHMENTOFTALLNATIVEGRASSESONEXTENSIVEROOFS<br />

By Richard K. Sutton<br />

American conservationist, Aldo Leopold asked us to “Think like a<br />

mountain.” When it comes to extensive green roofs in drier climates,<br />

however, we need to think like a prairie.<br />

Selected research on tall grass prairie species questions their use,<br />

but sedum now used on too many extensive green roofs is a monoculture<br />

inherited from Northwest European countries including<br />

Germany — and nature rewards diversity.<br />

In the Great Plains’ climate, short- and mid-grass prairies have<br />

evolved diverse communities of grasses, <strong>for</strong>bs and sedges in shallow<br />

soil with hot summers, cold winters, high winds, low humidity<br />

and little rainfall. While sedum grows well in Germany’s effective 15<br />

to 18 inches of net precipitation (accounting <strong>for</strong> potential evapotranspiration),<br />

the Great Plains prairie can flourish on net precipitation<br />

that has a 0- to 15-inch deficit.<br />

Thinking like a prairie in 2006, Architectural Partnership, an architectural<br />

firm in Lincoln, Nebraska, designed the state’s first public<br />

building, the Pioneers Park Nature Center (PPNC) Prairie Building<br />

addition, to incorporate a 900-square-foot extensive green roof.<br />

The green roof uses Hydro-tek Gardendrain system covered by<br />

three and one-half inches of Rooflite’s 95 per cent heat expanded<br />

shale and five per cent compost by volume.<br />

Given where the building was situated, it was only logical to take<br />