Living Architecture Monitor - Green Roofs for Healthy Cities

Living Architecture Monitor - Green Roofs for Healthy Cities

Living Architecture Monitor - Green Roofs for Healthy Cities

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

GREEN ROOFS FOR HEALTHY CITIES<br />

WINTER<br />

VOLUMENO<br />

LIVING<br />

ARCHITECTURE<br />

MONITOR<br />

PLANTSFORHOTCOLD<br />

ANDDROUGHTS<br />

ORGANICVS<br />

INORGANIC?<br />

CREATINGHABITAT

LIVING<br />

ARCHITECTURE<br />

MONITOR<br />

WINTERVOLUMENO<br />

<strong>Living</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong> is published four times per year by<br />

<strong>Green</strong> <strong>Roofs</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Healthy</strong> <strong>Cities</strong>* (www.greenroofs.org)<br />

Steven W. Peck<br />

Publisher & Founder<br />

speck@greenroofs.org<br />

416.971.4494 ext. 233<br />

Caroline Nolan<br />

Editor<br />

cnolan@greenroofs.org<br />

416.971.4494 ext. 231<br />

ARTDIRECTION<br />

IR&Co Inc.<br />

ADVERTISE<br />

416.971.4494 ext. 231 or advertise@greenroofs.org<br />

Rate card & insertion order <strong>for</strong>m are also available online at<br />

www.greenroofs.org/magazine<br />

SUBSCRIBE<br />

Subscriptions are included with membership to <strong>Green</strong> <strong>Roofs</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Healthy</strong> <strong>Cities</strong>.<br />

Three levels of membership are available (in US dollars):<br />

1. Supporter Membership - $50<br />

2. Professional Membership - $149<br />

3. Corporate Memberships - $750 to $4800<br />

To learn more about our various membership levels and their various other benefits<br />

please visit our website at: www.greenroofs.org<br />

Change address<br />

circulation@greenroofs.org or mail or fax to address below.<br />

CONTACTUS<br />

406 King Street East, Toronto, Ontario M5A 1L4 Canada<br />

Tel. 416.971.4494 Fax 416.971.9844<br />

www.greenroofs.org<br />

SUBMITNEWSSTORYIDEASORFEEDBACK<br />

We welcome letters to the editor, feedback and comments, as well as story<br />

ideas and industry news about people, products and projects <strong>for</strong> consideration<br />

in upcoming editions of the <strong>Living</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong>: editor@greenroofs.org.<br />

<strong>Green</strong> <strong>Roofs</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Healthy</strong> <strong>Cities</strong> — North America, Inc. was founded in 1999 as a<br />

small network of public and private organizations and is now a rapidly growing<br />

501(c)(6), not-<strong>for</strong>-profit industry association. Our mission is to increase the<br />

awareness of the economic, social and environmental benefits of green roofs<br />

and green walls, and other <strong>for</strong>ms of living architecture through education,<br />

advocacy, professional development and celebrations of excellence.<br />

Members of Board<br />

Peter Lowitt, chair, Devens Enterprise Commission<br />

Dan Sloan, secretary, McGuire Woods LLP<br />

Richard J. Buist, Landscource Organixs Ltd.<br />

Jeffrey Bruce, Jeffery L. Bruce & Co. LLC<br />

Peter D’Antonio, Sika Sarnafil Inc.<br />

Karen Moyer, City of Waterloo (Ontario)<br />

*<strong>for</strong>merly the <strong>Green</strong> Roof Infrastructure <strong>Monitor</strong><br />

Disclaimer: Contents are copyrighted and may not be reproduced without written consent. Every ef<strong>for</strong>t has<br />

been made to ensure the in<strong>for</strong>mation presented is accurate. The reader must evaluate the in<strong>for</strong>mation in<br />

light of the unique circumstances of any particular situation and independently determine its applicability.

COLD<br />

What can we learn from the climate characteristics of<br />

Nordic green roofs?<br />

By Kerry Ross<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

FROMTHEFOUNDER<br />

AVISIONFORTHEFUTURE<br />

By Steven W. Peck<br />

STRATA—PEOPLEPRODUCTS&PROJECTS<br />

ALIVINGLABORATORY<br />

Students and scientists team up on two green roofs at<br />

New York City’s Ethical Culture Fieldston School.<br />

GROUND-BREAKINGSUSTAINABLESITES<br />

INITIATIVELAUNCHED<br />

ASLA, Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center and<br />

others developing voluntary standards <strong>for</strong> sustainable<br />

land use and landscaping practices.<br />

REVIEW<br />

Books: ALSA’s Case Study; Ian McHarg — Conversations<br />

with Students; Busby: Learning Sustainable<br />

Design; and Alessandro Rocca’s Natural <strong>Architecture</strong><br />

ONTHEROOFWITH…<br />

AQ&AWITHTHELEGENDARYLANDSCAPE<br />

ARCHITECTCORNELIAHAHNOBERLANDER<br />

By Caroline Nolan<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

DROUGHT<br />

Evaluating the per<strong>for</strong>mance of green roof plants and<br />

growing medium.<br />

By Dr. Bill Retzlaff, Dr. Susan Morgan, Kelly Luckett<br />

and Vic Jost<br />

CREATINGHABITAT<br />

BYDESIGN<br />

A new process model can help you make the right<br />

decisions when trying to restore habitats <strong>for</strong> a specific<br />

species on green roofs and wall projects.<br />

By Dr. Reid Coffman and Alison Thurmond<br />

POLICY<br />

SEATTLE’S“GREENFACTOR”<br />

A new urban landscaping policy is creating an incentive<br />

<strong>for</strong> more green roofs and walls in this coastal city.<br />

By Lillian Mason and GRHC staff<br />

”BUSHTOPS”DOWNUNDER<br />

South Australian government’s green wall and green<br />

roof incentive policies are bringing the “bush” back<br />

into Adelaide.<br />

By Graeme Hopkins & Christine Goodwin<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

PROJECT<br />

ISLANDPARADISE<br />

An award-winning Ontario residential project — three<br />

years later.<br />

By Flavia Bertram<br />

BESTPRACTICE<br />

GROWINGMEDIA—THEORGANICQUESTION<br />

Rick Buist & Chuck Friedrich face off on how much<br />

organic — if any — is best <strong>for</strong> optimal per<strong>for</strong>mance.<br />

NATIVEPLANTRESEARCH<br />

IMPACTOFGROWINGMEDIAONPRAIRIEGRASSES<br />

Thinking like a prairie in Lincoln, Nebraska.<br />

By Richard K. Sutton<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

GRHCUPDATE<br />

GREENWALLTECHNOLOGYCLIMBING<br />

By Lillian Mason and GRHC staff<br />

OMAHAWELCOMESOPPORTUNITYTOBUILD<br />

MOREGREEN ROOFS<br />

Stormwater management among topics discussed at recent<br />

Nebraskan-based Local Market Development Symposium.<br />

By Kent E. Holm<br />

SYMPOSIUMIGNITESGREENROOF&WALL<br />

MOMENTUMINATLANTA<br />

From architects to policymakers — the finest<br />

professionals gathered to brainstorm an action plan<br />

<strong>for</strong> more green roofs in Georgia’s capital city.<br />

By Lillian Mason & GRHC staff<br />

<br />

NATIVESURVIVORS<br />

Insights from study conducted by the New England Wild<br />

Flower Society in partnership with the Massachusetts<br />

College of Art.<br />

By Ron M. Wik<br />

<br />

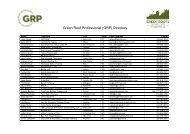

FROMTHEACCREDITATIONSUB-COMMITTEE<br />

First <strong>Green</strong> Roof Professional accreditation exam<br />

planned <strong>for</strong> 2009 conference in Atlanta, Georgia.<br />

By Hazel Farley<br />

<br />

EXTREMECONDITIONS<br />

HOT&HUMID<br />

What plants work best in tropical and subtropical climates?<br />

By Steve Skinner<br />

<br />

ONSPEC<br />

FROMWHEREIAGREENROOFERSIT<br />

The role of the landscaper on green roof projects.<br />

By Kurt Horvarth

FROMTHEFOUNDER<br />

AVISIONFOR<br />

THEFUTURE<br />

IMAGINEASWEDOOURCOLLECTIVE<br />

POWERTOCREATEHEALINGRESTORATIVE<br />

BUILDINGSDESIGNEDWITHLIVING<br />

ARCHITECTUREPRINCIPLES<br />

THEEDITTBUILDINGINSINGAPORE<br />

Image courtesy of TR Hamzah & Yeang Sdn Bhd

THEGROWINGMEDIA&PLANTISSUE<br />

Welcome to the <strong>Living</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong>. We are dedicated<br />

to bringing you the best research, policy and practices<br />

focused on the integration of living and non-living elements<br />

in and around buildings. <strong>Living</strong> architecture is the pathway to<br />

making a more fundamental shift towards the creation of<br />

healing, restorative high-per<strong>for</strong>mance buildings — and by<br />

extension, healthier, more liveable communities.<br />

In essence, healing, restorative, high-per<strong>for</strong>mance buildings give back<br />

more than they use over their lifecycles: producing a surplus of renewable<br />

energy, cleaner water, improved air quality and aesthetics,<br />

the very foundation <strong>for</strong> vibrant biological diversity and the greater<br />

physical and emotional well-being of humans.<br />

<strong>Green</strong> roofs and green walls are two key elements of living<br />

architecture that are gaining more widespread acceptance<br />

throughout North America. These living architectural <strong>for</strong>ms allow<br />

<strong>for</strong> unparalleled benefits at different scales — at the site level<br />

(aesthetics, stormwater quality and quantity): at the building level<br />

(energy savings, noise reduction, membrane durability, recreation<br />

space, urban food production, improved PV efficiency, biodiversity,<br />

advertising, marketability, improved investment value); at the community<br />

level (improved aesthetics, air quality benefits, cooling<br />

urban heat island, noise abatement, educational opportunities,<br />

community food production, psychological benefits); and the wider<br />

region (reducing greenhouse gases, supporting ecological diversity)<br />

— and this list is by no means complete.<br />

We need to re-imagine buildings as small ecosystems, nestled within<br />

the larger bioregions of our communities. McDonough and Braungart,<br />

in Cradle to Cradle, call <strong>for</strong> a shift toward “eco-effectiveness” and<br />

suggest we adopt a new design assignment set out to create “buildings,<br />

that like trees, produce more energy than they consume and purify<br />

their own wastes.” Restorative buildings won’t add more stress to<br />

existing infrastructure, such as coal-fired plants and the lengthy<br />

transmission wires that supply power; or our overtaxed water and<br />

wastewater treatment plants that regularly discharge vast quantities<br />

of raw sewage into our lakes, rivers and oceans.<br />

filtered through a series of ‘John Todd like’ facades and vegetated-terraces.<br />

The indigenous vegetation areas are designed to be continuous<br />

and to ramp upwards from the ground plane to the uppermost floor in<br />

a linked landscaped ramp. The design’s planted-areas constitute 3,841<br />

sq.m., a ratio 1:0.5 of gross useable area to gross vegetated area. Rainwater<br />

will be cleansed, stored in the basement and provide water <strong>for</strong><br />

toilets and irrigation <strong>for</strong> the living architectural features, an amenity to<br />

building occupants on every floor of the 26-story structure.<br />

If living architecture is to blossom as a practice this century, we also<br />

need to understand the full contribution that living systems offer —<br />

economic, social, psychological and environmental and ensure that<br />

these are reflected, rather than discounted in the marketplace.<br />

The vehicle <strong>for</strong> this change is through policies, regulations, and standards<br />

and investment. At a city-wide scale, we need to better understand<br />

the economic benefits of widespread living architecture in order<br />

to help facilitate the public resources required to fully support these<br />

developments. As our industry continues to rapidly grow, we can trans<strong>for</strong>m<br />

the building industry into a fundamental <strong>for</strong>ce <strong>for</strong> sustainability.<br />

<strong>Green</strong> <strong>Roofs</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Healthy</strong> <strong>Cities</strong> is dedicated to bringing about the<br />

rapid shift towards a living architecture and the creation of healing<br />

restorative buildings. Through this new publication, we will work<br />

tirelessly to bring you, our members, the latest in research, product<br />

developments, standards, tools, innovative designs and new policies<br />

that support your ability to make a lasting life-long contribution<br />

towards sustainable building.<br />

Sincerely yours,<br />

<strong>Living</strong> architecture is exemplified in Ken Yeang’s remarkable EDITT skyscraper<br />

in Singapore, designed from an ecological approach (pictured<br />

left). The building will be 55 per cent water self-sufficient, produce<br />

renewable energy and process wastewater. Captured rainwater is<br />

Steven W. Peck<br />

Founder and President<br />

LIVING ARCHITECTURE MONITOR WINTER

STRATA<br />

KUDOS<br />

PRIZE-WINNINGPROJECTS<br />

At <strong>Green</strong> <strong>Roofs</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Healthy</strong> <strong>Cities</strong>, we love to<br />

celebrate excellence in green roof and wall<br />

design — so our hats go off to the following individuals<br />

and organizations <strong>for</strong> their recent<br />

achievements:<br />

PRESERVINGSTORMWATERINPHILLY<br />

Pennoni Associates, a consulting engineering<br />

firm headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania<br />

won the award <strong>for</strong> Stormwater Best Management<br />

Practices <strong>for</strong> its green roof design on<br />

The Radian, located on Walnut Street in<br />

Philadelphia. The honors came from the<br />

Philadelphia Water Department, Offices of the<br />

Watersheds, a statewide program that recognizes<br />

innovative stormwater best management<br />

practices. The project, which integrates green<br />

roof areas into the public terrace level of a<br />

mixed-use facility that includes lower level<br />

retail space and a 13-story residential tower<br />

<strong>for</strong> student apartments, broke ground in Mary<br />

2007 and will open this August. The innovative<br />

strategy <strong>for</strong> stormwater management drains<br />

runoff from impervious areas of the roof into<br />

the green roof structure, maximizing water<br />

retention on the roof while controlling the<br />

release rate into two underground stormwater<br />

management basins. Additionally, the plant<br />

design of the green roof will serve as a valued<br />

amenity to residents and the community at<br />

large. Erdy McHenry <strong>Architecture</strong> was the<br />

project architect while <strong>Roofs</strong>capes, Inc. served<br />

as subconsultant to Pennoni and provided key<br />

technical expertise <strong>for</strong> the green roof design.<br />

GREENINGCALGARY<br />

On Nov. 1, 2007, the city of Calgary’s<br />

Mayor’s Urban Design Awards took place<br />

with eight winners and four honourable<br />

mentions in a variety of categories. A<br />

conceptual entry, Grey to <strong>Green</strong>: <strong>Green</strong>ing<br />

Calgary One Roof at a Time, was jointly<br />

submitted by Kerry Ross, an architectural<br />

consultant with IBI Group in Calgary and<br />

Kelly Learned of Cochrane, Alberta, earned<br />

an honourable mention and special acknowledgement<br />

by Juror Shannon Nichol<br />

of the international landscape architecture<br />

firm, Gustafson Guthrie Nichol. Their<br />

entry illustrated how a green roof on one<br />

of Calgary’s landmarks, the Municipal<br />

Building, could set the tone <strong>for</strong> the region<br />

in terms of becoming a green roof<br />

technology leader.<br />

BELOWThe award-winning Radian in Philadelphia was recognized <strong>for</strong> its innovative stormwater management strategy. “This project is an example of how ecology,<br />

economics and aesthetics can be balanced to satisfy not only the owner and the users of the building, but also broader environmental goals,” says Marc Morfei,<br />

Philadelphia senior landscape architect.<br />

Renderings: Erdy McHenry <strong>Architecture</strong><br />

COMINGUP<br />

The Toronto Botanical Garden will host a green roof conference on Feb. 21, 2008. The event’s<br />

conference workshops will cover design, plants, biodiversity and technical considerations. Paul<br />

Kephart of Rana Creek will be a speaker, as well as the instructor <strong>for</strong> GRHC’s Ecological Design<br />

Course to be held in the morning of Feb. 22, also at the Botanical Gardens. For in<strong>for</strong>mation<br />

about the event, please email greenroof@logistix.com or see their website at www.torontobotanicalgarden.ca/greenroof.<br />

Further in<strong>for</strong>mation and registration details about GRHC’s Ecological Design course on Feb. 22<br />

can be found at www.greenroofs.org<br />

NEWS<br />

WANTED!<br />

We want to hear about your<br />

announcements (deals and projects<br />

completed); people moves; awards;<br />

and books and events. Send us an email<br />

at editor@greenroofs.org and your<br />

news may end up in Strata <strong>for</strong> our next<br />

issue. Please include photographs or<br />

images if applicable.<br />

<br />

LIVING ARCHITECTURE MONITOR<br />

WINTER

THEGROWINGMEDIA&PLANTISSUE<br />

ALIVINGLABORATORY<br />

STUDENTSOFALLAGESAREGETTINGANEDUCATION—ANDLEARNINGWHATIT’SLIKE<br />

TOCONDUCTRESEARCHALONGSIDECOLUMBIAUNIVERSITYSCIENTISTSATOPA NEW<br />

YORKCITYMIDDLESCHOOL’STWOGREEN ROOFS<br />

Students at New York City’s Ethical Culture<br />

Fieldston School will soon be applying their<br />

science studies towards green roof research.<br />

The recent $75 million renovation of the middle<br />

school has incorporated green building<br />

design and two green roofs. Dr. Stuart Gaffin,<br />

associate research scientist at The Center <strong>for</strong><br />

Climate Systems Research at Columbia<br />

University in New York and Dr. Mathew<br />

Palmer, a lecturer with the Department of<br />

Ecology, Evolution and Environmental Biology,<br />

also at Columbia University, spearheaded the<br />

research and study of the two roofs, both different<br />

in purpose and design.<br />

Fieldston made available its two green roofs<br />

<strong>for</strong> Columbia’s research, which in turn will<br />

present unusual opportunities <strong>for</strong> the<br />

school’s science teachers from grades<br />

one through 12.<br />

“There are many different technological<br />

aspects to green building design but none of<br />

them offers the educational richness of green<br />

roofs,” says Gaffin, who is in charge of the<br />

research at the school’s top-level roof. “<strong>Green</strong><br />

roofs can be used to teach physics, climatology,<br />

hydrology, biology, ecology, chemistry<br />

and so on. One could never develop such a<br />

far-reaching curriculum, around say, solar<br />

panels or energy-efficient windows.” His own<br />

“ There are many different technological aspects to green building design but none of<br />

them offers the educational richness of green roofs. <strong>Green</strong> roofs can be used to<br />

teach physics, climatology, hydrology, biology, ecology, chemistry and so on.”<br />

Dr. Stuart Gaffin, research scientist, Columbia University<br />

research centers on the energy benefits of<br />

Fieldston’s green roof with New York’s energy<br />

and water issue needs in mind.<br />

Columbia’s research on the top-level roof is<br />

conducted using a weather tower, multiple<br />

sets of soil moisture and temperature probes,<br />

an albedometer and plant foliage temperature<br />

sensors. The albedometer consists of<br />

two back-to-back pyranometers, a device<br />

designed to measure natural sunlight radiant<br />

energy, manufactured by Kipp and Zonen.<br />

“With the data we are collecting and subsequent<br />

analysis, much of which will be done by<br />

the students, I hope we can produce findings<br />

<strong>for</strong> an ‘optimal’ green roof design that maximizes<br />

environmental benefits at the lowest<br />

cost,” explains Gaffin. “This will help spur<br />

their adoption by New York City and elsewhere.”<br />

The lower level roof of the school, planted in<br />

part by Fieldston’s students last October, was<br />

designed to be a more interactive site with<br />

three different types of plant communities. In<br />

addition to a traditional mix of Sedum<br />

species, two native, diverse grassland communities<br />

were planted. One of these communities<br />

was modeled on the Hempstead Plains,<br />

a prairie-like grassland from Long Island<br />

which has been almost completely lost due to<br />

urban and suburban development. The other<br />

native community is modeled on grasslands<br />

native to the Hudson Valley’s rocky hilltops<br />

with shallow soil, droughts and harsh wind, a<br />

climate very similar to that on the roof. Students<br />

will follow the success of the different<br />

plantings through time and will compare<br />

ecological processes like pollination and the<br />

development of the soil between the three<br />

plant communities.<br />

“If we can learn how to make native plant<br />

communities succeed on green roofs, it will<br />

add immensely to the value of those roofs as<br />

ecological restoration projects, habitat <strong>for</strong><br />

other species and living laboratories <strong>for</strong><br />

schools,” says Palmer.<br />

The students at Fieldston created a video<br />

detailing the building process of the second<br />

roof which can be viewed at www.ecfs.org <br />

By Lillian Mason & GRHC staff<br />

LIVING ARCHITECTURE MONITOR WINTER

STRATA<br />

GROUND-BREAKING<br />

SUSTAINABLESITES<br />

INITIATIVELAUNCHED<br />

ASLALADYBIRDJOHNSONWILDFLOWERCENTERAND<br />

OTHERSAREDEVELOPINGVOLUNTARYSTANDARDSFOR<br />

SUSTAINABLELANDUSEANDLANDSCAPINGPRACTICES<br />

The American Society of Landscape Architects<br />

(ASLA), the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower<br />

Center, the United States Botanic<br />

Garden, and other stakeholders are working<br />

under the umbrella of the Sustainable Sites<br />

Initiative to develop voluntary standards and<br />

guidelines related to sustainable land use and<br />

landscaping practices.<br />

The initiative was established to “identify the<br />

gold standards in sustainable landscape design<br />

and marry them to a practical, real-world<br />

approach so that designers, planners,<br />

builders, and developers can utilize them,”<br />

says Nancy Somerville, executive vice president<br />

and CEO of the ASLA.<br />

In a preliminary report published in November<br />

2007, a committee composed of 32 professionals<br />

practicing across a variety of landscape<br />

related disciplines identified a series of design<br />

goals and methods of achieving and monitoring<br />

a site’s ability to satisfy these objectives. The<br />

group further recommended integrated design<br />

strategies as a means to “harness natural<br />

processes to provide environmental benefits.”<br />

The guidelines are scheduled <strong>for</strong> release in<br />

May 2009 and will be incorporated into the<br />

USGBC’s LEED® system.<br />

For more in<strong>for</strong>mation or to participate in the<br />

review process visit www.sustainablesites.org.<br />

GREENGRID<br />

INSTALLS<br />

LARGEST<br />

MODULAR<br />

ROOFIN<br />

NORTH<br />

AMERICA<br />

A 2.3 acre modular green roof, the largest of<br />

its kind in North America, covers the new<br />

court at Upper Providence shopping center<br />

in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. The<br />

<strong>Green</strong>Grid® modules were installed in early<br />

2007 thanks to a joint venture between Gambone<br />

Development, Inc. and The Highland<br />

Development Group, Ltd.<br />

WASHINGTONDCSUPPORTSGREEN<br />

ROOFDEMONSTRATIONPROJECTS<br />

Through a grant from the District Department<br />

of the Environment, Watershed Protection<br />

Division, DC <strong>Green</strong>works, a<br />

preeminent green roof organization in the<br />

area, is subsidizing $3 per square foot of<br />

green roof demonstration projects.<br />

“This broadly available subsidy is generating<br />

a interest from a wider variety of developers<br />

than other incentives in the DC area.<br />

It is effectively helping mainstream building<br />

and land owners test out this progressive<br />

technology that wouldn’t otherwise have<br />

access to green roof funding,” says Sheila<br />

“This broadly available<br />

subsidy is…effectively<br />

helping mainstream<br />

building and land owners<br />

test out this progressive<br />

technology that wouldn’t<br />

otherwise have access to<br />

green roof funding.”<br />

Sheila Hogan, DC <strong>Green</strong>works, Washington, DC<br />

Hogan, executive director of DC<br />

<strong>Green</strong>works.<br />

In order to qualify an extensive or intensive<br />

project must be in D.C., can be new construction<br />

or retrofit, and on buildings with a<br />

footprint under 5,000 square feet or larger,<br />

in cases where the supporting structure<br />

was built prior to 1988. The program’s next<br />

deadline is February 15, 2008; others will<br />

be announced when determined.<br />

For further in<strong>for</strong>mation and the application <strong>for</strong>m<br />

visit: www,dcgreenworks.org.<br />

<br />

LIVING ARCHITECTURE MONITOR<br />

WINTER

GREENROOFSGO<br />

EXTREME—ANDPRIMETIME<br />

THEGROWINGMEDIA&PLANTISSUE<br />

It was Tuesday in April 2007 when<br />

Kelly Luckett got the call. A construction<br />

manager from the top show, Extreme<br />

Makeover Home Edition, asked if Luckett’s<br />

company, St. Louis-based <strong>Green</strong> Roof<br />

Blocks, could provide green roof modules<br />

<strong>for</strong> a green roof they were planning on a<br />

fully sustainable house they were building<br />

<strong>for</strong> a needy family in Pinon, Arizona on a<br />

Navaho Reservation. Luckett said he would<br />

be pleased to help, then came the kicker:<br />

the construction manager needed fully<br />

grown-out modules by that Sunday —<br />

just four days away.<br />

Under normal circumstances, it would take<br />

three to four weeks to deliver fully grown out<br />

modules, but Luckett was undeterred — even<br />

in the early spring. Saying yes, he quickly<br />

turned to his team on to the company’s research<br />

plots. “We could barely scrape together<br />

the number of square footage they<br />

needed — 200-modules, about 400 square<br />

feet in total,” he remembers. With plants<br />

ready, then came the real challenge — getting<br />

the modular plants, based in St. Louis, Missouri,<br />

to Pinon, Arizona — in just days. “No<br />

commercial freight carriers would commit to<br />

timelines, so we wound up putting it all into a<br />

rental truck and a staff member drove it<br />

across the country,” says Luckett.<br />

Luckett and his business partner both took<br />

time off to help out on the rapid installation<br />

of the green roof, bringing along their children<br />

<strong>for</strong> the once-in-a-lifetime experience.<br />

He was joined by another seasoned green<br />

roof professional, Dr. Bill Retzlaff, associate<br />

professor and chair of the Department of<br />

Biological Sciences Environmental Sciences<br />

Program at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville<br />

in Illinois.<br />

A hectic schedule, but well worth it, says<br />

Luckett, especially at the moment of the big<br />

“reveal” when the new house was unveiled<br />

<strong>for</strong> the worthy family. “It was a very emotional<br />

moment,” says Luckett, who, like every<br />

other contributor to the house, donated all<br />

his materials and time to make this dream<br />

house a reality <strong>for</strong> a very special family.

REVIEW<br />

TWISTINGNATURE<br />

Drawing on the works of artists dedicated to<br />

the use of natural materials — trees, wood,<br />

bamboo and pebbles — Alessandro Rocca’s<br />

Natural <strong>Architecture</strong> locates its readers at the<br />

intersection of art, architecture and ecology.<br />

The artists are all linked together by their desire<br />

to create incredibly complex installations<br />

while minimizing their effect on the environment<br />

in which they are created. Most employ<br />

basic artistic techniques and rely on manual<br />

labor to create awe-inspiring structures that<br />

will inevitably disintegrate but which raise lingering<br />

questions about our ways of inhabiting<br />

space. (Princeton Architectural Press, 2007)<br />

STRIKINGTHERIGHTBALANCE<br />

In an industry as new and multidisciplinary as<br />

the living architecture field, it is rare to get a<br />

project’s whole story. Not so anymore, Christian<br />

Werthmann’s <strong>Green</strong> Roof — A Case Study<br />

provides a comprehensive account of the<br />

American Society of Landscape <strong>Architecture</strong>’s<br />

green roof, in which Landscape Architects<br />

Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates<br />

and the Conservation Design Forum were<br />

charged with the task of maximizing both aesthetics<br />

and environmental per<strong>for</strong>mance. For<br />

the novice, the book demystifies every aspect<br />

of green roofing; <strong>for</strong> the seasoned professional,<br />

it allows <strong>for</strong> detailed examination of<br />

the design methodologies, construction techniques<br />

and maintenance practices employed<br />

to achieve these lofty goals. In an interview<br />

between the author and Van Valkenburgh,<br />

the designer placed emphasized the importance<br />

of striking the right balance. Hopefully,<br />

this book will help others do the same.<br />

(Princeton Architectural Press, 2007)<br />

ADAPTATION<br />

Ian McHarg, the author of the ecological design<br />

classic Design with Nature, has greatly<br />

trans<strong>for</strong>med the approach to and understanding<br />

of land-use planning and landscape architecture.<br />

Ian McHarg — Conversations with<br />

Students: Dwelling in Nature rearticulates the<br />

guiding principles of the “McHarg Method,”<br />

an interdisciplinary approach to land use design<br />

rooted in the notion that “creativity has<br />

permeated the evolution of matter and life,<br />

and actually is indispensable <strong>for</strong> the survival<br />

of the system.” He goes on to lay out the tools<br />

needed <strong>for</strong> the analysis and execution of<br />

“creative fitting,” a process driven by the<br />

theory that “any system is required to find<br />

of all environments the most fit, to adapt<br />

that environment, and to adapt itself.”<br />

(Princeton Architectural Press, 2007)<br />

BUSBY’SVISION<br />

Busby and Associates Architects are known<br />

<strong>for</strong> buildings that combine a Modernist aesthetic<br />

with environmentally responsive and<br />

integrated design strategies. Busby: Learning<br />

Sustainable Design profiles twelve of the<br />

firm’s projects (which coincidentally draw<br />

upon the theoretical framework of Ian<br />

McHarg’s Design with Nature), highlighting<br />

their contribution to the development of new<br />

green building per<strong>for</strong>mance standards. The<br />

book, produced in collaboration with heavyweights<br />

David Suzuki (<strong>for</strong>eward) and editors<br />

Jim Taggart and Kathy Wardle, will serve the<br />

interests of those interested in the theory,<br />

practice and direction of the sustainable<br />

design industry, especially the need <strong>for</strong> multidisciplinary<br />

collaboration. As Taggart notes:<br />

“Optimizing per<strong>for</strong>mance depends on a critical<br />

appreciation of the interdependence of structure,<br />

<strong>for</strong>m, envelope design and environmental<br />

systems.” (Janam Publications Inc., 2007)<br />

By Flavia Bertram

Photos courtesy Elisabeth Whitelaw<br />

ONTHEROOFWITH…<br />

CORNELIAHAHNOBERLANDERCMFCSLAFASLA<br />

By Caroline Nolan<br />

Cornelia Hahn Oberlander, born in Germany in 1924, obtained a BA<br />

from Smith College in 1944 and was one of the first women to<br />

graduate from Harvard University’s School of Design with a degree in<br />

landscape architecture in 1947. She worked with Louis I. Kahn and<br />

Oscar Stonorov in Philadelphia, and landscape architect Dan Kiley in<br />

Vermont, be<strong>for</strong>e moving to Vancouver to establish her own practice in<br />

1953, Cornelia Hahn Oberlander Landscape Architects.<br />

Her career is legendary.<br />

The 84-year-old is well-known <strong>for</strong> such extraordinary, pioneering works<br />

including “Robson Square” — the provincial government courthouse<br />

complex in Vancouver, a three-block green roof designed in collaboration<br />

with the architect Arthur Erickson (1974–81); the National Gallery<br />

of Canada, with architect, Moshe Safdie; University of British Columbia’s<br />

(UBC) Museum of Anthropology, also with Arthur Erickson<br />

(1975–76); the Canadian Chancery in Washington DC, also with Arthur<br />

Erickson (1989); the spectacular 28,000 square-foot semi-intensive<br />

roof on Moshe Safdie’s Vancouver Public Library (1995); and the Northwest<br />

Territories Legislative Assembly Building in Yellowknife, Canada<br />

with Matsuzaki Wright Architects and Gino Pin Architects (1995).<br />

She has received numerous awards including the prestigious Order of<br />

Canada in 1990; several honorary degrees from University of British<br />

Columbia (UBC), Simon Fraser University, Ryerson University and<br />

Smith College; a commemorative Medal <strong>for</strong> the 125th Anniversary of<br />

the Confederation of Canada in 1992; the Royal Architectural Institute<br />

of Canada Allied Medal in 1995; and an honorary membership to the<br />

Architectural Institute of BC as well as life membership in the British<br />

Columbia Society of Landscape Architects.<br />

Cornelia, a true pioneer of socially conscious and sustainable<br />

landscape design, has collaborated with internationally acclaimed<br />

architects, including Renzo Piano on public projects in the United<br />

States and Canada. We caught up with Oberlander in Vancouver<br />

late last year.<br />

LIVING ARCHITECTURE MONITOR WINTER

ONTHEROOFWITH…<br />

Q: The Germans have a wonderful sense of stewardship <strong>for</strong> nature<br />

and, indeed, created the green roof concept in the first place.<br />

Do you feel your heritage has influenced your work?<br />

A: Well, when I was 15, we landed in New York from Germany in<br />

1939, be<strong>for</strong>e the war, because my mother thought it was <strong>for</strong> us. A<br />

year and a half later, she came down from breakfast one day and<br />

said to me and my sister, ‘This place is too materialistic <strong>for</strong> you girls<br />

— all you are thinking about is sweaters and skirts. When you come<br />

new to a country you have to till the soil.’ She then whisked us in<br />

our wooden-bodied Ford Station wagon up to northern New Hampshire<br />

and that’s where I grew up. She was trained as a horticulturalist<br />

and created a Victory Garden to grow vegetables during the war<br />

and so, that’s how I grew up.<br />

Q: You have practiced “living architecture” be<strong>for</strong>e the term even<br />

existed — what does the term mean to you now?<br />

A: <strong>Living</strong> architecture means that the building is healthy and the land<br />

is healthy and that you are contributing to the biomass of the city,<br />

namely to make the air cleaner. I feel that if you have chosen the<br />

profession of landscape architecture, you have a duty to listen to what<br />

the times bring. It’s not what I was taught at Harvard way back when,<br />

necessarily, but all about what we must make of the land today. I’ve<br />

always looked to the future.<br />

Q: How has landscape architecture profession changed since you<br />

established your own practice in 1953?<br />

A: Well, the industry was non-existent then. You hoped <strong>for</strong> the best,<br />

that the building wouldn’t fall down! But I was already at Harvard realizing<br />

I could not work in a vacuum — that I would have to work in collaboration<br />

with architects.<br />

Q: Early in your career, did you ever imagine you would ever see the<br />

mainstreaming of green roofs as is happening now?<br />

A: Well, I had hoped it would happen. The municipal bylaws and the<br />

building bylaws of every city must include green roofs. We have not<br />

reached this goal yet.<br />

MOSHESAFDIE’SVANCOUVERPUBLICLIBRARY<br />

Q: You are retrofitting one of your most important and noted<br />

projects, Vancouver’s Robson Square — what is being done and why?<br />

A: Well, after 35 years it was time. In 1976, the waterproofing membrane,<br />

or EPDM, was guaranteed <strong>for</strong> 20 years, and it lasted <strong>for</strong> 35<br />

years. So that had to be renewed, but on top of that, the province of<br />

British Columbia demanded seismic upgrading <strong>for</strong> the whole building,<br />

and so this is being done at present and with it, came an in-depth<br />

analysis of the plant materials which were possible to keep. We lifted<br />

out several 8,000-pound Japanese Maple Trees among others, took<br />

them to a nursery and brought them back last spring and then planted<br />

them in exactly the same location as be<strong>for</strong>e.<br />

Q: What were some of the challenges you encountered with your<br />

design of the green roof on Vancouver’s Library Square Building?<br />

A: I don’t work with soils, so I knew already in 1976 I knew that I could<br />

only have a lightweight growing medium <strong>for</strong> the roofs <strong>for</strong> the Robson<br />

Square installation. So <strong>for</strong> the Library Square, I researched at great<br />

length how could I get a lightweight growing media and I came upon<br />

the idea to collect all the vegetable food waste from the restaurants in<br />

Vancouver and have them process it into compost. The final mix is<br />

one-third compost from vegetable food waste, one-third pumice and<br />

one-third sand: it’s called the Library mix — and we will use it at Robson<br />

Square again, so the challenge was to talk the owners into allowing<br />

us to use this lightweight material.<br />

“I feel that if you have chosen the profession<br />

of landscape architecture you have a duty to<br />

listen to what the times bring...I’ve always<br />

looked to the future.”

THEGROWINGMEDIA&PLANTISSUE<br />

Q: Looking ahead, what changes do you see?<br />

A: Well, first of all, we must curb this desire to sprawl. We must limit<br />

our footprints and employ the principles of ecodensity — that’s number<br />

one. Number two: we must use every bit of ground <strong>for</strong> public parks and<br />

not give it away to developers. Number three: if we want living buildings,<br />

we must work together as a team of architects, engineers, landscape<br />

architects.<br />

Q: As a landscape architect, how do you feel about the emergence of<br />

green walls?<br />

A: I think it is very good idea because they insulate the building against<br />

the cold and heat but they have to be built with drip irrigation. But I<br />

would like to speak to you about wildlife.<br />

Q: Please do...<br />

A: Well, we must build with a holistic approach, <strong>for</strong> example, it is important<br />

to include the Canada Geese, and all the other birds that flock<br />

around. Let them have fun on the roof!<br />

Q: Canada Geese on a roof?<br />

A: Yes. On the Library roof, I have two nice Canada Geese couples,<br />

(you know they mate <strong>for</strong> life), which come to certain balconies of the<br />

Court House, <strong>for</strong> instance, but the judges aren’t too happy with this<br />

and have asked <strong>for</strong> them to be removed — so I have not educated<br />

everyone yet! On the roof of the Vancouver Library, an inaccessible<br />

roof, I have two more sets of Canada Geese that sit on the roof and<br />

have their children and then they fly away and return every year. So<br />

education is necessary <strong>for</strong> a holistic approach that allows humans and<br />

geese to be part of the urban landscape.<br />

Q: If you could impart one kernel of wisdom to other professionals<br />

in this field, what would it be?<br />

A: Think about climate change which concerns all of us and what we<br />

have done to this planet. Learn what we can do and with every project<br />

to lessen the impact on the environment. <strong>Green</strong> roofs increase<br />

biomass, insulate buildings against heat and cold and slow down<br />

stormwater runoff, if they’re constructed properly. You can do this<br />

only if you have done your research and if you are working with<br />

professionals who know how to implement these ideas with working<br />

drawings and specifications.<br />

Q: A perfect ending — thank you <strong>for</strong> your wonderful visions and work. <br />

Caroline Nolan is the editor of the <strong>Living</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong>.

PROJECT<br />

ISLANDP<br />

<br />

LIVING ARCHITECTURE MONITOR<br />

WINTER

THEGROWINGMEDIA&PLANTISSUE<br />

PROJECTSPECIFICATIONS<br />

LOCATION Thousand Islands, Ontario<br />

PROJECTTYPE New Construction<br />

GREENROOFSIZE 1,700 square feet<br />

COMPLETIONDATE 2002-2003<br />

YEAROFAWARD 2004<br />

CLIENT/DEVELOPER Carol and Kevin Reilly<br />

ARCHITECT Shim-Sutcliffe Architects (Winner)<br />

DESIGNCONSULTANT Mill & Ross Architects<br />

DESIGNCONSULTANT Donald Chong Studio<br />

STRUCTURALENGINEERSBlackwell Engineering<br />

MECHANICALENGINEERSToews Systems Design (Mechanical)<br />

CONTRACTOR Michael Sheedy and Mark Peabody<br />

GREENROOFDESIGNER Marie-Ann Boivin, Soprema Canada<br />

GREENROOFLANDSCAPECONTRACTOR Top Nature, Montreal<br />

ARADISE<br />

By Flavia Bertram<br />

LIVING ARCHITECTURE MONITOR WINTER

PROJECT<br />

The majority of green roof projects are located in highly developed<br />

areas, characterized by limited green space, a searing urban heat<br />

island effect, stormwater management issues, and as such, often used<br />

to mitigate these negative effects of urbanization. Not so in the case<br />

of the 2004 Award of Excellence winning Howe Island home on the<br />

St. Lawrence River in the Thousand Islands, Ontario.<br />

The once rural, now semi-suburban island has a history of dairy farming<br />

and is not subject to the same environmental problems as city<br />

centers. As a result this green roof project was driven by aesthetics<br />

rather than the environmental benefits of the technology.<br />

Shim-Sutcliffe Architects conceived the house with the intent of<br />

The upper semi-intensive roof transposed the meadow plants from<br />

the ground to the roof, thereby integrating the building with the<br />

landscape. This visual effect is facilitated by the omission of parapet<br />

walls, resulting in roof perimeter details like those usually found<br />

on sloped rather than flat roofs. Six-inch deep growing medium sits<br />

on top of a modified bitumen membrane and root repellent layer<br />

and is contained by borders, which are then surrounded by stone<br />

vegetation-free zones to prevent the occurrence of plant erosion.<br />

Prior to construction, and to reinvigorate the large meadow, the<br />

five-acre site was hydroseeded (a process where a slurry of seeds<br />

and mulch is sprayed over a targeted area) with clover and a mixture<br />

of local indigenous flowers. The clover was harvested and<br />

respecting the region’s agrarian tradition and maintaining the openness<br />

of the landscape while providing their clients with privacy and a<br />

splendid view of the river. The green roofs, designed with Soprema<br />

Canada, were one of many elements that contributed the project<br />

goals of balancing the landscape, structure and water. On the side<br />

facing the St. Lawrence River the house opens up to a large water<br />

garden with indigenous water lilies and bulrushes.<br />

Initially, the two roofs did not utilize the same vegetation. The<br />

lower extensive roof was planted with a more traditional sedum<br />

palette, including Sedum album, Sedum floriferum ‘Weihenstephaner<br />

Gold’, Sedum kamtschaticum ellacombianum and Sedum<br />

Spectabile ‘Brilliant’.<br />

“The green roof is part of<br />

larger vision <strong>for</strong> landscape;<br />

it is one part of a greater<br />

approach to the agrarian<br />

context of the island.”<br />

Brigitte Shim, Shim-Sutcliffe Architects<br />

<br />

LIVING ARCHITECTURE MONITOR<br />

WINTER

THEGROWINGMEDIA&PLANTISSUE<br />

trans<strong>for</strong>med into bales of hay by a local farmer, continuing the<br />

site’s tradition of contributing to local agriculture.<br />

This same blend was subsequently used in the field of the upper<br />

roof of this island paradise, which was then bordered by sedums.<br />

This connection between the roof and the ground, however, proved<br />

to be problematic <strong>for</strong> the semi-intensive roof’s maintenance. The<br />

original plant-selection (comprised of French hybrids) were quickly<br />

overrun by native Canadian weeds and wildflowers. Though the area<br />

was reseeded after the establishment period was complete, the<br />

maintenance was certainly more than the client had bargained <strong>for</strong>.<br />

During the design phase, it became apparent to both the architects<br />

Both roofs have been annually supplemented with two or three flats<br />

of sedum to ensure continuous plant coverage.<br />

Despite this alteration, the striking Howe Island green roof continues<br />

to be an example of site-specific design that is sensitive to the visual<br />

and cultural aspects of the surrounding environment. The clover<br />

meadow and the two green roofs compliment each other, blurring the<br />

borders of the building roof and the ground plane. <br />

Flavia Bertram is a research assistant with <strong>Green</strong> <strong>Roofs</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Healthy</strong> <strong>Cities</strong> in<br />

Toronto. She is also a contributor to a new book published by <strong>Green</strong> <strong>Roofs</strong><br />

<strong>for</strong> <strong>Healthy</strong> <strong>Cities</strong> and Schiffer Publishing called Stretching the Boundaries<br />

of <strong>Green</strong> Roof Design and <strong>Living</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong>: Five Years of Award-Winning<br />

“Once we<br />

got the right<br />

plants on<br />

the roof it<br />

became easy<br />

to handle.”<br />

Carol Riley, owner & client<br />

and manufacturer that the several-hours-by-car distances from the<br />

nearest centers of green roof knowledge in Canada —Toronto and<br />

Montreal — were too far <strong>for</strong> maintenance personnel to travel. As a result,<br />

the owners and a local gardener were trained in basic maintenance<br />

procedures and bore the responsibility <strong>for</strong> them. This capacity<br />

development is in keeping with the projects goals of respecting the island<br />

and surrounding area’s existing tradition of agrarian self-reliance.<br />

However, this independence also necessitated that the labour required<br />

in its upkeep be limited and resulted in the replanting of the<br />

upper roof with low maintenance drought resistant sedum species.<br />

Similarly, plants on the lower roof were redistributed after the establishment<br />

period was over in order to create a stronger plant palette.<br />

Projects in the spring. In the book other <strong>Green</strong> Roof Awards of Excellence<br />

winning projects and individuals are recognized <strong>for</strong> demonstrating extraordinary<br />

leadership and are celebrated <strong>for</strong> their valuable contribution to the<br />

green roof industry. This case study is but one of many featured in this exciting<br />

book, which will be launched at the upcoming annual GRHC conference<br />

in Baltimore in April. Please see www.greenroofs.org <strong>for</strong> details.<br />

INTERESTEDINHAVINGYOURPROJECTPROFILEDHERE?<br />

We are currently seeking excellent and innovative green roof and green<br />

wall projects <strong>for</strong> in-depth case studies <strong>for</strong> future “Project” consideration.<br />

Tell us about yours by sending an email to editor@greenroofs.org.<br />

It would be helpful to include a few photographs.<br />

LIVING ARCHITECTURE MONITOR WINTER

BESTPRACTICE<br />

THEORGANIC<br />

QUESTION<br />

WHENITCOMESTOGROWINGMEDIATHEREISCONSID-<br />

ERABLEDEBATEASTOWHATEXACTLYCONSTITUTESTHE<br />

BESTMIXFORSUPERIORPERFORMANCE<br />

On any green roof project, there inevitably comes a time when<br />

professionals must answer a crucial question: Exactly what kind of<br />

growing media is best <strong>for</strong> the roof’s long-term per<strong>for</strong>mance?<br />

In North America, much research is still required to determine the<br />

optimal composition of growing media and a wide variety of opinions.<br />

Currently, many green roof professionals are grappling with<br />

the issue of organics versus non-organic materials in growing media.<br />

Here, we present just two of those opinions from two, respected<br />

industry professionals, both members of <strong>Green</strong> <strong>Roofs</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Healthy</strong><br />

<strong>Cities</strong>’ Growing Media Sub-Committee which is developing per<strong>for</strong>mance<br />

standards <strong>for</strong> growing media: Chuck Friedrich and Rick Buist.<br />

Rick Buist is a horticulturalist and president of BioRoof Systems<br />

Inc. and chair of the GRHC Growing Media Sub-Committee.<br />

Chuck Friedrich is also a horticulturist — and landscape architect —<br />

and is the director of horticulture research and product development<br />

<strong>for</strong> Carolina Stalite Company in Salisbury, North Carolina. He is<br />

also a member of the American Society of Landscape Architects, NC<br />

Landscape Contractors Association, and ASTM <strong>Green</strong> Roof Subcommittee.<br />

He also sits on the ASTM <strong>Green</strong> Roof Task Committee.<br />

<br />

LIVING ARCHITECTURE MONITOR<br />

WINTER

THEGROWINGMEDIA&PLANTISSUE<br />

“DON’TCALLITDIRT!”<br />

By Chuck Friedrich, RLA, ASLA<br />

My college soil science professor always reprimanded the class<br />

<strong>for</strong> referring to soil as “dirt.” He would always say: “dirt is<br />

something that is tracked in onto the carpet.” Actually the ideal<br />

green roof growing media should NOT contain any natural soil;<br />

there<strong>for</strong>e, we should not even call it soil. Most green roof professionals<br />

prefer the term growing media or medium, substrate, or<br />

planting media. My definition <strong>for</strong> green roof media is: “the particulate<br />

matter or substrate that anchors the plant roots to sustain plant<br />

growth.” Sounds simple, but it can get very complicated.<br />

For proper terminology, we should refer to the growing media as<br />

intensive or extensive green roof media. The media should be designed<br />

<strong>for</strong> the physiology of the plant material growing in the media.<br />

Sedums require an extensive media that has a coarser gradation than<br />

those used <strong>for</strong> grasses or other non-succulents. In addition to plant<br />

material, other factors affecting media selection are climate, weight,<br />

fertility, depth, location, microclimate, and irrigation. With all these<br />

factors to contend with we can then add a bunch of engineers to the<br />

equation. Over the past 15 years I have supplied green roof media on<br />

over 140 green roofs. It has been a learning experience offering much<br />

success. (Having a German last name didn’t hurt.)<br />

LOSINGORGANICMEDIA<br />

Trees, shrubs, lawns and flowers need water, air, space <strong>for</strong> the roots,<br />

and nutrients. Within the proper microclimate, many plants can<br />

grow better on the roof than on the ground. Why? With a green roof<br />

we can create a very big pot filled with the perfect growing media<br />

that is fertilized, irrigated, and most important, well drained. What<br />

we don’t want is a natural soil or a 100 per cent organic mixture<br />

GOINGFORORGANICS<br />

By Rick Buist<br />

When considering the writing of this best-practices article on<br />

using organics in growing medium, I reflected on the experiences<br />

I have had in the green roof marketplace to date. Since first becoming<br />

aware of the green roof industry, I had numerous people tell<br />

me how you shouldn’t use more than a certain percentage of organics<br />

in the growing medium. One says five per cent, another 20 per cent,<br />

and yet others argue it would be best if there were no organics at all!<br />

Now at the time, I found this all rather odd. Our company has many<br />

successful installations (over 80 to date) with few observed problems,<br />

and our sister company has been producing millions of cubic meters of<br />

organic-based growing mediums <strong>for</strong> decades to the nursery industry.<br />

Then I was told that our organic growing medium projects we installed<br />

did not have a long enough track record to be sufficiently evaluated.<br />

“Just you wait,” they ominously warned, ‘eventually the organic growing<br />

medium will disappear — it’ll be a disaster.” One person even<br />

claimed they had pictures of a green roof we installed showing exposed<br />

roots — impending doom was just around the corner!<br />

So I took all of this great advice to heart and also personally visited the<br />

site in question, only to discover the growing medium depth had not<br />

changed in four years. The roots were not exposed (although clumping<br />

fescues could give that appearance) and the owners were very happy.<br />

Naturally I had to ask myself: Why the strident accusations against organics<br />

in growing mediums?” Is it because some have invested in proprietary<br />

products associated with growing mediums? Is it because of the European<br />

experience? Or do they really have a sound scientific argument?<br />

LIVING ARCHITECTURE MONITOR WINTER

BESTPRACTICE<br />

contained up on a giant frying pan in the sky. Natural soils are<br />

cohesive and can change over a long period of time or simply get<br />

“damaged” if installed when wet. The same is true with organic<br />

matter; though it is a very important component, too much organic<br />

can be problematic depending on the circumstances.<br />

Organic matter breaks down and is washed out of the system due to<br />

rain or irrigation; to replace lost material could require many trips<br />

with heavy bags up steps or an elevator. The use of natural soil or too<br />

much of the wrong type of organic amendment may produce finer<br />

particles. Fine particles can move down and accumulate on the filter<br />

fabric, slowing down drainage. I have not been a big fan of sewage<br />

sludge compost <strong>for</strong> this reason. Runoff from green roofs containing<br />

levels of nutrients is a topic of current discussion with water quality<br />

researchers.<br />

The best practice is to use a media that will provide enough air<br />

throughout the profile to promote the roots to go down instead of<br />

up. If the bulk of roots are down deeper in the media where it is<br />

cool and moist, the better the plant can sustain itself during periods<br />

of extreme temperature.<br />

When proportionally blended, a mixture of lightweight aggregate,<br />

quality sand and organic compost makes a good media <strong>for</strong> intensive<br />

green roofs. 3/8" and finer lightweight aggregate has pore spaces in<br />

Throughout the horticultural and landscape industry, organics are the<br />

overwhelming trend. The industry has embraced organics’ role in sustaining<br />

biological functions in the soil. Research is abundant, covering<br />

actinomycetes, nematodes, micchorhizal fungi and various other microand<br />

macro-organisms (let’s not <strong>for</strong>get the lowly earthworm) — all of<br />

which bind contaminants, cycle nutrients, suppress disease and more.<br />

So once again, I asked myself: With this track record and research going<br />

on, why are many in the green roof world so opposed to using organics?<br />

If I were to ignore the obvious implications <strong>for</strong> those who have<br />

invested in distribution rights <strong>for</strong> European based systems, I would<br />

have to turn to the science behind the German Standards developed<br />

by the nonprofit known as Forschungsgesellschaft Landschaftsentwicklung<br />

Landschaftsbau (or FLL). I spent considerable time reviewing the<br />

FLL Standard and the research that led to its’ very conclusions.<br />

I also considered it imperative to understand the initial terms of reference<br />

and historical context by which the need <strong>for</strong> the standards<br />

came about. The terms of reference weighed very heavily on avoidance<br />

of problems, which given some of the failures in the German<br />

marketplace at the time, seemed to make sense. Un<strong>for</strong>tunately, I do<br />

not have enough article space to get into everything that I found;<br />

however, there are some serious holes.<br />

The first of which is the way the Standard does not adequately<br />

distinguish between organics (this may be because the science of soil<br />

biology was out of fashion at the time, research focused instead on<br />

the science of chemistry — much better funding opportunities).<br />

When referring to organics, there must be awareness that there is a<br />

huge array of source stock, composting processes, characteristics,<br />

etc…which makes it impossible to generalize. No one would suggest<br />

that we should refer to the entire automotive world as being all the<br />

same. Is a skateboard the same as an F1 racing car? That’s absurd. It is

THEGROWINGMEDIA&PLANTISSUE<br />

“Organic matter breaks<br />

down and goes away; to<br />

replace lost material could<br />

require many trips with<br />

heavy bags up steps or<br />

an elevator.”<br />

Chuck Friedrich<br />

the particles which lighten the load, retain nutrients and water, and<br />

best of all it is permanent. A good quality graded sand as filler is<br />

good <strong>for</strong> stability, and a measured amount of the proper organic<br />

compost provides microbial activity that is beneficial to the biology<br />

of the media. Currently, there are no standards related to the use of<br />

compost on green roofs.<br />

What about fertilizer? Save it <strong>for</strong> planting time. There is absolutely<br />

no reason to add fertilizer to a green roof media during the blending<br />

process. For good reason, in most cases the media is installed<br />

months be<strong>for</strong>e the first plant is installed. There<strong>for</strong>e, why spend<br />

money on fertilizer that will only end up leaching out and down the<br />

drain be<strong>for</strong>e the plants show up on the job? The best method is to<br />

blend a good slow release fertilizer into the top layer of the media<br />

during the planting operation.<br />

Once planted, provide lots of maintenance and irrigation; with that<br />

it can be beautiful and last <strong>for</strong> several decades. I <strong>for</strong>got to mention,<br />

also add lots of money, you get what you pay <strong>for</strong>. If you can keep the<br />

general contractor and schedule in check, the process can actually<br />

go smooth, right? Wrong. Don’t <strong>for</strong>get about the engineer.<br />

AWEIGHTYSUBJECT<br />

I am amazed how the specification on the weight of the media can<br />

be so tight, while in the same specification, the plan calls <strong>for</strong> 14<br />

Oak trees to be planted. It tickles me when I am asked at least<br />

twice per month by designers, “how much does a full grown tree<br />

weigh?” What? Dogwood or Sequoia? Does an additional pound or<br />

two per cubic foot of media, one way or another, make that much<br />

of a difference? I guess it will when 350-pound Aunt Bertha and<br />

the twins decide to have lunch up on the roof.<br />

All kidding aside, weight is an issue, especially on retrofitted extensive<br />

roofs. It is important to design using the saturated weight of the<br />

media. The ASTM Sub-committee <strong>for</strong> <strong>Green</strong> <strong>Roofs</strong> has developed<br />

standards <strong>for</strong> the practice and test methods <strong>for</strong> the determination<br />

almost as absurd to consider all organics to be the same. There are<br />

some organics that I would never use on a green roof (some of which<br />

were used in the research behind the FLL Standard). From cellular<br />

structure to composting process and beyond, organics are far too complex<br />

to generalize within a Standard.<br />

Secondly, the FLL Standard dictates organic content by mass. I can<br />

understand why, since the dominant testing method <strong>for</strong> organic content<br />

is the burn method, which can only measure by mass. However, by doing<br />

so, the Standard leaves a lot open to interpretation. For instance, one<br />

can use an extremely heavy inorganic material to achieve a high percentage<br />

of organic content since organics are generally much lighter. I was<br />

able to achieve organic content of over 60 per cent by volume in the<br />

growing medium but only eight per cent by mass. Was this ambiguity<br />

intended by the Standard?<br />

Interestingly, contrary to what I heard in the industry, the FLL Standard<br />

did allow <strong>for</strong> higher levels of organics. Section 9.2.2 states: “A greater<br />

proportion of organic matter may be required where special <strong>for</strong>ms of<br />

vegetation, such as humus rooting plants, are used.” This shows the<br />

importance of matching the growing medium to the physiological<br />

needs of the plants, another area largely uninitiated by many suppliers<br />

in our industry.<br />

Thirdly, the Standard focused on material specifications instead of<br />

per<strong>for</strong>mance specifications and by doing so, essentially closed the<br />

door on innovation. (It seems the lowly sedum is the order of the day,<br />

matched to equally low per<strong>for</strong>mance mediums). This caused companies<br />

to scramble to find similar products in North America with the<br />

prize going to those who could quickly identify and corner the market<br />

on certain products. As most of the construction industry in North<br />

America makes the change to per<strong>for</strong>mance-based specifications, the<br />

FLL Standard represents a step backward.<br />

Lastly, I concluded the Standard itself was not as much a problem<br />

as people’s interpretation of it. For example; there seems to be much<br />

misunderstanding of what organic content is. One hundred per cent<br />

FORMULATING, TESTING, PLANT<br />

GROWTH TRIALS, PROBLEM SOLVING<br />

“SEND US YOUR<br />

EXTENSIVE/INTENSIVE 5<br />

GALLON PAIL PLEASE!”<br />

SOIL CONTROL LAB<br />

42 HANGAR WAY<br />

WATSONVILLE, CA 95076<br />

(831) 724-5422 PHONE,<br />

(831) 724-3188 FAX,<br />

WWW.GREENROOFLAB.COM<br />

FRANK@COMPOSTLAB.COM<br />

CONTACT: FRANK SHIELDS

“Why the strident<br />

accusations against<br />

organics in growing<br />

mediums? Is it because<br />

some have invested in<br />

proprietary products<br />

associated with growing<br />

mediums? Is it because<br />

of the European experience?<br />

Or do they really<br />

have a sound scientific<br />

argument?”<br />

Rick Buist<br />

organic material may only have an end organic content of 20 per cent.<br />

The remaining 80 per cent may be inorganic or mineral based. This is<br />

largely lost in the language of the industry.<br />

The per<strong>for</strong>mance which organic matter brings to stormwater retention,<br />

pollutant degradation, plant variety, cooling benefits, sustainable materials,<br />

etc. is too great to ignore.<br />

Organic-based growing media can hold far more water than mineralbased<br />

growing mediums while maintaining porosity; this is because of<br />

the way in which they hold water through particle swelling instead of just<br />

void filling and capillary <strong>for</strong>ces. Biology can be customized to degrade

THEGROWINGMEDIA&PLANTISSUE<br />

of dead loads and live loads associated with green roof systems. If<br />

flooded, the media weight could increase up to 20 pounds over the<br />

drained weight. This could be catastrophic when a heavy snow load<br />

is added to roof during the same event.<br />

MEDIAFORSEDUMS<br />

Most extensive growing media is used in a thin profile of three to six<br />

inches. If weight restrictions allow; go deeper, just keep Aunt Bertha<br />

off the roof.<br />

Sedums do well in aerated media. Most extensive media is at least<br />

80 per cent lightweight aggregate (<strong>for</strong> porosity and nutrient retention).<br />

Care must be taken not to design a growing media that is too<br />

fine. If the media does not routinely dry out, excessive water may<br />

cause weed promotion and some sedum roots to rot.<br />

Sedums will die quicker if the media stays too wet rather than<br />

too dry. In my view, it is better to provide a well-drained material<br />

with supplemental irrigation then to have plant loss during the<br />

rainy season.<br />

SPEAKINGOFIRRIGATION<br />

Those who think extensive green roof systems do not need, at least<br />

temporary irrigation ought to camp out on a green roof in North<br />

Carolina during an August heat wave. I have run several studies in<br />

NC and have been able to just get by without automatic watering.<br />

That success ended with this year’s record drought. No matter how<br />

fine the media was or the amount of organic content in the mix, the<br />

sedums still died from lack of moisture. Without the morning mist<br />

experienced daily in Germany and the Pacific Northwest, sedums<br />

have a tough time in hotter and drier climates. Though sedums may<br />

go dormant and survive a green roof that looks like dead weeds is<br />

bad <strong>for</strong> business. Find a water source, reclaimed if you must, and<br />

find a way to get it up on the roof. Do not over water; monitoring irrigation<br />

after the establishment period is essential. The controversy<br />

over irrigation will continue; occasional drip irrigation as needed<br />

works. The holdouts need to quit bellyaching and just do it.<br />

In conclusion, controversy between schools of thought over green<br />

roof media will continue within the United States. Being in its infancy<br />

compared to Europe, whether intensive or extensive, communications<br />

between the parties involved do tend to drift. When everyone<br />

with professional integrity and the proper knowledge work together<br />

and stay current with the latest technology, the long-term results will<br />

benefit everyone. <br />

specific and non-specific pollutants. Plants that provide evaporative<br />

cooling can be used more frequently with success. Fertilization can<br />

occur naturally through nutrient cycling. Materials can be sourced<br />

locally. And the list of benefits goes on.<br />

Practically every argument I have heard against the use of organics<br />

comes with a relatively easy solution:<br />

• Lost depth because of organic cycling is easily addressed through<br />

inputs such as biomass created by the plant choice through roots<br />

or refuse, or annual (if required at all) top-dressing with a<br />

pelletized product such as compost or alfalfa (readily available<br />

in dry, bagged <strong>for</strong>m).<br />

• Fines clogging drains or water-logging can be averted by careful<br />

selection of organic materials. Organics with crystalline structures,<br />

such as certain bark-based products, will behave much like sand <strong>for</strong><br />

free drainage, while organics with strand characteristics will hold<br />

structure together. Careful selection and installation of components<br />

such as filter cloth are also helpful.<br />

• Wind erosion is averted by using biodegradable netting until plants<br />

are established, thereby providing continuous cover.<br />

• Fire prevention can be improved by avoiding certain substances<br />

(i.e. peat moss — a limited resource) and by using organics with<br />

high ignition-thresholds and large moisture-retention capacities.<br />

Although any biomass on a roof can burn, it is easy to mitigate the<br />

risk by paying attention to the details.<br />

My intention in promoting the use of organics is not to replace<br />

the good work already achieved by the FLL Standard (the bulk of<br />

which I strongly endorse), but to expand its terms of reference. We<br />

should not be afraid of opening the door to creativity. Let’s set<br />

per<strong>for</strong>mance objectives that will not only serve to reduce risk but<br />

also allow <strong>for</strong> innovation.<br />

We should also practice what we preach. If we as an industry are<br />

promoting stormwater retention or cooling benefits, we must prescribe<br />

a high level of per<strong>for</strong>mance to justify the cost of our product. If<br />

not, we risk being passed off as a fad, as eco-chic. Are we environmental<br />

stewards? Don’t we appear hypocritical by using mined products<br />

<strong>for</strong> the bulk of our material? If we’re pushing the idea of biodiversity,<br />

we must use plantings that give entomological teeth to our argument.<br />

An immature marketplace is always better served by collaboration<br />

than by competition. We risk alienating an extremely large demographic<br />

in the landscape, horticultural and composting industries who<br />

could help our industry immensely if we continue to promote against<br />

the use of organics. <br />

LIVING ARCHITECTURE MONITOR WINTER

NATIVEPLANTRESEARCH<br />

IMPACTOFGROWINGMEDIA<br />

ON PRAIRIEGRASSES<br />

RESEARCHFROMLINCOLNNEBRASKAPROVIDESINSIGHTONTHEPERFORMANCEOF<br />

GROWINGMEDIAINTHEESTABLISHMENTOFTALLNATIVEGRASSESONEXTENSIVEROOFS<br />

By Richard K. Sutton<br />

American conservationist, Aldo Leopold asked us to “Think like a<br />

mountain.” When it comes to extensive green roofs in drier climates,<br />

however, we need to think like a prairie.<br />

Selected research on tall grass prairie species questions their use,<br />

but sedum now used on too many extensive green roofs is a monoculture<br />

inherited from Northwest European countries including<br />

Germany — and nature rewards diversity.<br />

In the Great Plains’ climate, short- and mid-grass prairies have<br />

evolved diverse communities of grasses, <strong>for</strong>bs and sedges in shallow<br />

soil with hot summers, cold winters, high winds, low humidity<br />

and little rainfall. While sedum grows well in Germany’s effective 15<br />

to 18 inches of net precipitation (accounting <strong>for</strong> potential evapotranspiration),<br />

the Great Plains prairie can flourish on net precipitation<br />

that has a 0- to 15-inch deficit.<br />

Thinking like a prairie in 2006, Architectural Partnership, an architectural<br />

firm in Lincoln, Nebraska, designed the state’s first public<br />

building, the Pioneers Park Nature Center (PPNC) Prairie Building<br />

addition, to incorporate a 900-square-foot extensive green roof.<br />

The green roof uses Hydro-tek Gardendrain system covered by<br />

three and one-half inches of Rooflite’s 95 per cent heat expanded<br />

shale and five per cent compost by volume.<br />

Given where the building was situated, it was only logical to take<br />