Section 06 - UKOTCF

Section 06 - UKOTCF

Section 06 - UKOTCF

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

limits on production (h) and simplifies the environment<br />

by favouring a narrow range of productive<br />

types (i). This increases production (h), but causes<br />

widespread pollution, soil erosion and loss of<br />

biodiversity. It also displaces inherited diversity (j)<br />

in the form of locally adapted types and involves<br />

the convergent selection (k) of a narrow range of<br />

productive types dependent on the external inputs<br />

provided. This further simplifies the environment<br />

and compromises the provision of natural capital<br />

and ecosystem services (l).<br />

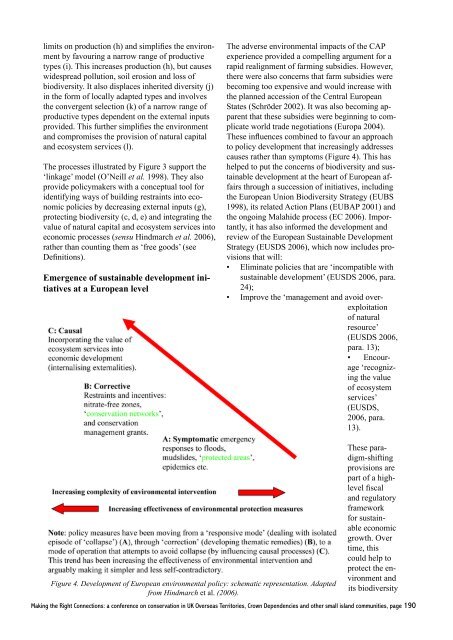

The processes illustrated by Figure 3 support the<br />

‘linkage’ model (O’Neill et al. 1998). They also<br />

provide policymakers with a conceptual tool for<br />

identifying ways of building restraints into economic<br />

policies by decreasing external inputs (g),<br />

protecting biodiversity (c, d, e) and integrating the<br />

value of natural capital and ecosystem services into<br />

economic processes (sensu Hindmarch et al. 20<strong>06</strong>),<br />

rather than counting them as ‘free goods’ (see<br />

Definitions).<br />

Emergence of sustainable development initiatives<br />

at a European level<br />

The adverse environmental impacts of the CAP<br />

experience provided a compelling argument for a<br />

rapid realignment of farming subsidies. However,<br />

there were also concerns that farm subsidies were<br />

becoming too expensive and would increase with<br />

the planned accession of the Central European<br />

States (Schröder 2002). It was also becoming apparent<br />

that these subsidies were beginning to complicate<br />

world trade negotiations (Europa 2004).<br />

These influences combined to favour an approach<br />

to policy development that increasingly addresses<br />

causes rather than symptoms (Figure 4). This has<br />

helped to put the concerns of biodiversity and sustainable<br />

development at the heart of European affairs<br />

through a succession of initiatives, including<br />

the European Union Biodiversity Strategy (EUBS<br />

1998), its related Action Plans (EUBAP 2001) and<br />

the ongoing Malahide process (EC 20<strong>06</strong>). Importantly,<br />

it has also informed the development and<br />

review of the European Sustainable Development<br />

Strategy (EUSDS 20<strong>06</strong>), which now includes provisions<br />

that will:<br />

• Eliminate policies that are ‘incompatible with<br />

sustainable development’ (EUSDS 20<strong>06</strong>, para.<br />

24);<br />

• Improve the ‘management and avoid overexploitation<br />

of natural<br />

resource’<br />

(EUSDS 20<strong>06</strong>,<br />

para. 13);<br />

• Encourage<br />

‘recognizing<br />

the value<br />

of ecosystem<br />

services’<br />

(EUSDS,<br />

20<strong>06</strong>, para.<br />

13).<br />

Figure 4. Development of European environmental policy: schematic representation. Adapted<br />

from Hindmarch et al. (20<strong>06</strong>).<br />

These paradigm-shifting<br />

provisions are<br />

part of a highlevel<br />

fiscal<br />

and regulatory<br />

framework<br />

for sustainable<br />

economic<br />

growth. Over<br />

time, this<br />

could help to<br />

protect the environment<br />

and<br />

its biodiversity<br />

Making the Right Connections: a conference on conservation in UK Overseas Territories, Crown Dependencies and other small island communities, page 190