You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

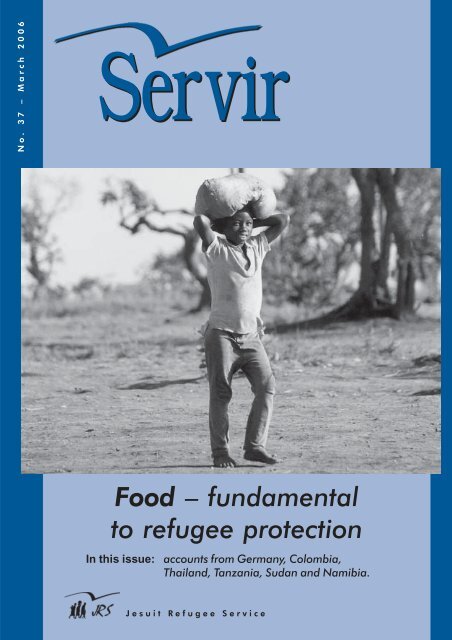

No. 37 – March 2006<br />

Servir<br />

Food – fundamental<br />

to refugee protection<br />

In this issue:<br />

accounts from Germany, Colombia,<br />

Thailand, Tanzania, Sudan and Namibia.<br />

Jesuit Refugee Service<br />

SERVIR No. 37 – March 2006 1

EDITORIAL<br />

Self-reliance, yes!<br />

But not through food cuts<br />

Lluís Magriñà SJ<br />

Breakdowns in food supply oblige<br />

forced migrants to make choices<br />

which have a negative impact<br />

their lives. This Servir examines the<br />

issue of food security for refugees and<br />

other forced migrants. In many cases,<br />

difficulties accessing food are institutional.<br />

States and the international community<br />

in general have abandoned them<br />

to fend for themselves, without giving<br />

them the right to farm land or to work.<br />

<strong>JRS</strong> runs projects and advocacy campaigns<br />

that mitigate the effects of these<br />

policies; but it’s not enough when the<br />

focus of beneficiaries is their survival.<br />

Refugee kitchen, Venezuelan-Colombian<br />

Mr Keßler describes the situation of Ali,<br />

caught in a dispute between two states.<br />

He is unable to obtain food and shelter<br />

without a residence permit. To receive<br />

one, he must have a travel document,<br />

which was denied to him without a residence<br />

permit. This is not simply a bureaucratic<br />

mistake. Germany, like other<br />

industrialised states, is adopting new policies<br />

to deter refugees from coming and<br />

is using lack of access to sufficient food<br />

as part of this deterrence policy.<br />

Mr Bustillo explains how if it were not<br />

for the assistance provided by friends,<br />

family and organisations like <strong>JRS</strong>, survival<br />

for many internally displaced persons<br />

(IDPs) in Colombia would be in<br />

question. The situation is complex. The<br />

Colombian government is charged with<br />

protecting IDPs but is also responsible<br />

for causing their displacement, for denying<br />

them sufficient support while displaced<br />

and for encouraging their return<br />

to unsafe areas.<br />

Ms den Otter examines recent changes<br />

in UNHCR, the UN refugee agency,<br />

policy towards refugees in Thailand.<br />

The agency promotes refugee self-re-<br />

liance, but the Thai government does<br />

not permit refugees to work. UNHCR<br />

is facing cuts to its budget, and has cut<br />

the assistance provided to refugees.<br />

The fortunate find work in the informal<br />

labour market where they risk government<br />

sanctions and exploitation at<br />

the hands of unscrupulous employers.<br />

Others, in particular children, survive<br />

as best they can.<br />

In Tanzania, Ms Le highlights the contradictions<br />

in national and international<br />

policy towards refugees. The Burundian<br />

refugees she describes depend<br />

almost entirely on the UN World Food<br />

Programme for survival. Insufficient<br />

rations force them to work illegally. After<br />

12 years, they have had enough and<br />

some are prepared to risk life at home.<br />

Of course rations should be increased<br />

but, more than that, they should be allowed<br />

to work and contribute to the<br />

development of the local economy.<br />

The consequences of inaction are<br />

clearly illustrated by Ms Kerrigan and<br />

Sr Whitaker. It is the most vulnerable<br />

who pay. Food insecurity prevents children<br />

from going to school. They are<br />

forced to work to support the family.<br />

Those at school are often unable to<br />

concentrate and learn more slowly.<br />

These are only a few examples of the<br />

terrible effects that policies, deliberate<br />

or not, have on forcibly displaced persons<br />

the world over. Food shortages<br />

can be the cause of family breakdown<br />

and malnutrition, particularly for children<br />

whose physical and psychological<br />

development can be seriously affected.<br />

This is why we pray in the Our<br />

Father: Give us this day our daily bread.<br />

Lluís Magriñà SJ, <strong>JRS</strong><br />

International Director<br />

2

Hunger and homelessness<br />

regulated by law<br />

GERMANY<br />

Stefan Keßler<br />

According to the latest UN Human Development Report,<br />

Germany is one of the richest countries in the<br />

world. Despite this, many people are hungry and<br />

homeless. For some, food and shelter are denied by law.<br />

One such person is Ali Mansour (not his real name). In the<br />

summer of 2003, the 23-year old Palestinian refugee came<br />

to Germany from Lebanon. In Berlin, he applied for residency,<br />

but his request was denied. Nevertheless, he could<br />

not be deported because he could not acquire proper documentation.<br />

The Lebanese authorities usually refuse to issue<br />

travel documents, essential for deportation, to Palestinians<br />

not in possession of a German residence permit.<br />

The official name given to Ali’s status is Duldung, or tolerated.<br />

As stated in the report by the Independent Commission<br />

on Immigration, established by the German Federal Minister<br />

of the Interior and headed by a former President of the German<br />

Federal Parliament, Prof. Dr. Rita Sueßmuth: the<br />

“Duldung is not a residence permit but a temporary suspension<br />

of deportation... Hence, it does not constitute a legal stay<br />

but exempts the illegal stay from being a criminal offence”.<br />

Fortunately, the Berlin regional government has promised<br />

to issue a new decree which would allow persons like Ali<br />

to receive at least food and shelter. However, it cannot be<br />

certain that the promised decree will offer tolerated persons<br />

sufficient food and shelter or that it will provide other<br />

necessities such as clothing and medical assistance.<br />

Ali’s fate is far from exceptional. <strong>JRS</strong> Germany deals with<br />

many cases where individuals fleeing human rights abuses,<br />

receive reduced support or, as in Ali Mansour’s case, nothing<br />

but homelessness and hunger regulated by the law.<br />

Stefan Keßler,<br />

Legal Officer, <strong>JRS</strong> Germany<br />

Low-cost supermarket, Germany<br />

When Ali applied for residency in 2003, he had no money<br />

and was refused a residence permit and consequently the<br />

right to undertake employment. The immigration office told<br />

Ali he needed a Lebanese passport in order to receive food<br />

and shelter until his deportation. The Lebanese embassy<br />

told him because he was Palestinian, he could not receive a<br />

passport unless he had a German residence permit.<br />

Without a residence permit, he was denied a passport, and<br />

without a passport the social security department refused<br />

to give him financial or any other form of support. Without<br />

his friends who provided shelter and shared what little they<br />

had with him, Ali Mansour would be living on the streets.<br />

<strong>JRS</strong> Germany assisted Ali to contest the decision to deny<br />

him basic assistance, but the court upheld the refusal. The<br />

relevant provisions are found in the German asylum seekers’<br />

social benefits act (Asylbewerberleistungsgesetz). The<br />

act also regulates social benefits to ‘tolerated’ non-nationals.<br />

According to the act, certain groups of non-nationals<br />

should receive 20 percent less than what is normally paid to<br />

Germans. In addition, article 1a of the act allows this assistance<br />

to be reduced to a minimum of what is absolutely<br />

necessary to survive.<br />

SERVIR No. 37 – March 2006<br />

3

COLOMBIA<br />

Colombian<br />

refugee,<br />

Venezuela<br />

Juan Manuel Bustillo<br />

Forced home<br />

but not protected<br />

When the local population is not<br />

being attacked by armed groups<br />

or by the army, it is being harmed<br />

by the government trying to spray the coca<br />

plants with poisonous acid. In response,<br />

many flee to what they consider safer areas.<br />

In the last three years alone, more than<br />

three million people, as much as 5 percent<br />

of Colombia’s population, have been forcibly<br />

displaced because of the country’s armed<br />

conflict. More than half of all displaced persons<br />

are children under the age of eighteen.<br />

While Colombia is among a handful of countries<br />

that has enacted legislation to protect<br />

internally displaced persons (IDPs); nonetheless,<br />

they are often not provided with<br />

food assistance. In 2003, nearly a quarter<br />

of displaced children were at risk of malnutrition,<br />

those between the ages of one and<br />

two years being the most affected.<br />

Governmental assistance, when granted, is<br />

limited and only granted to those officially<br />

registered as displaced. The process of registering<br />

and requesting humanitarian assistance<br />

takes many months. Assistance is<br />

normally provided for three months up to a<br />

maximum of six. After the three month<br />

period ends, most IDPs do not receive any<br />

further humanitarian assistance.<br />

Unable to get by, IDPs often feel forced to<br />

return home due to a lack of other options.<br />

The state assistance they receive when they<br />

return is better than what they receive as<br />

IDPs, but is still inadequate. Food support is<br />

only provided for a maximum of 60 days. Each<br />

family also receives approximately 157 USD<br />

per month, which is not sufficient to pay for<br />

food until the end of the harvesting season.<br />

Returning home also means returning to<br />

unsafe areas where daily life is threatened<br />

by fighting, and coca plant spraying. Because<br />

return is seen as the only valid option,<br />

integration into safer areas is effectively<br />

discouraged. Despite the danger, the<br />

Colombian government’s National Development<br />

Plan 2002-2006 seeks to persuade<br />

30,000 displaced families to return to their<br />

home areas. Government guidelines indicate<br />

the social and economic costs of displacement<br />

are reduced the quicker the decision<br />

to return home is made.<br />

Once home, many people find their freedom<br />

of movement restricted. In effect, prevents<br />

them from accessing food and healthcare.<br />

It also jeopardises their safety. In 2004, at<br />

least 70 villages throughout the country were<br />

threatened by the practices of the paramilitary<br />

and insurgent groups. However, state<br />

4

security forces have also been accused of<br />

restricting the movement of the inhabitants<br />

of towns and villages throughout Colombia,<br />

allegedly to prevent them from assisting<br />

paramilitary and insurgent groups.<br />

As a result of fighting between paramilitary,<br />

insurgent and military groups, on 1 May,<br />

42 families from Cerro Azul in northern<br />

Colombia were forcibly displaced. An 18-<br />

month old baby girl was killed and her father<br />

wounded during the clash. Residents<br />

fled. Shortly afterwards they were encouraged<br />

to return to Cerro Azul with the promise<br />

of state support for three months, however,<br />

only one food assistance package was<br />

provided to each returnee family.<br />

On 20 August, the Colombian government<br />

decided to spray the coca fields with glyphosate,<br />

a poisonous acid. It burns and dries<br />

everything it comes in contact with. One<br />

coca field located near a school was sprayed<br />

by light aircraft. The wind carried the glyphosate<br />

towards the school, burning the skin<br />

of several children. The school’s garden<br />

plants were also burned. Since they are<br />

afraid of being attacked by paramilitary<br />

groups, the pilots are not careful about<br />

where they spray. At times, they do not<br />

even spray the coca plants. Instead, they<br />

spray houses, people and animals.<br />

Consequently, the subsistence crops in the<br />

area were badly damaged. Food shortages<br />

and economic hardship followed. Failure by<br />

the authorities to provide food and support<br />

to the local population caused further displacement.<br />

With this knowledge in hand, the Colombian<br />

government has repeatedly failed to<br />

take action. In 2004, UNHCR, the UN<br />

refugee agency, urged the Colombian government<br />

not to make humanitarian assistance<br />

subject to budgetary availability and<br />

to allocate the necessary resources to prevent<br />

forced displacement. In the same year,<br />

Colombia’s Constitutional Court held that<br />

the government’s system for assisting displaced<br />

persons was unconstitutional. It declared<br />

the state had an obligation to provide<br />

humanitarian assistance to those IDPs not<br />

in a position to sustain themselves. In September<br />

2005, the Court found the steps<br />

taken by the government to comply with its<br />

ruling were insufficient in terms of both resources<br />

and institutional will.<br />

Nevertheless, the process of assisting IDPs<br />

continues to be overly bureaucratic, lack<br />

transparency and ignore persons awaiting<br />

official registration. It is evident that the decision<br />

to return is not voluntary. Displaced<br />

persons lack information regarding the security<br />

situation in their home areas. They presume<br />

the government will provide socio-economic<br />

support for their long-term security<br />

needs. Displaced persons are regularly faced<br />

with a choice between hunger and going<br />

home, even though return may mean living<br />

where there are minefields, a constant threat<br />

of armed attack, forced recruitment of children,<br />

and insufficient assistance from human<br />

rights organisations. Although they are not<br />

guaranteed any financial support at home,<br />

social and family ties, as well as organisations<br />

like <strong>JRS</strong> in Cerro Azul, make surviving<br />

from week to week somehow possible.<br />

Juan Manuel Bustillo,<br />

Advocacy Officer,<br />

<strong>JRS</strong> Colombia<br />

Maize,<br />

a staple<br />

part of the<br />

Colombian<br />

diet<br />

Returned IDP,<br />

Colombia<br />

SERVIR No. 37 – March 2006 5

THAILAND<br />

Struggling<br />

Vera den Otter<br />

Life for Xiong Pa (not his real name),<br />

a Laotian refugee, is not easy. His family,<br />

he says, does not have enough<br />

food to eat breakfast everyday. The rest of<br />

the time they usually just eat rice.<br />

He recalls, “we asked the Bangkok Refugee<br />

Centre (BRC, a local NGO partner of<br />

UNHCR, the UN refugee agency) to give<br />

us some money, as the subsistence allowance<br />

they give us is not enough to buy food.<br />

Of the 3,500 baht (approximately 70 euros)<br />

my brother and I are given, 2,500 goes on<br />

rent, the other 1,000 baht is spent on things<br />

like soap, transport and the like. We cannot<br />

afford to spend it on food. The last 10 days<br />

of the month are the worst, the money runs<br />

out quickly, and we have to skip more meals.<br />

Since we don’t have money for clothes, we<br />

go to <strong>JRS</strong> and they give us some”.<br />

Xiong’s kitchen<br />

Xiong’s living room<br />

Xiong Pa lives in a crowded room with eight<br />

other family members: three of his brothers<br />

and their wives and children. The children<br />

do not get the variety of food they so<br />

need while growing up. Like Xiong, the two<br />

eldest, 12 and 15 years old, only eat two<br />

meals of plain rice per day. They have<br />

learned to live with it and do not complain.<br />

His younger nephew though, cries day and<br />

night of hunger, but all the family can give<br />

him is some rice soup with a bit of sugar.<br />

Xiong says his family is lucky because they<br />

live above a restaurant owned by their landlord.<br />

Sometimes they are able to receive<br />

food other than rice in exchange for work.<br />

They also have relatives who occasionally<br />

give them a little extra money when it can<br />

be spared. He knows at least 10 other families<br />

who receive nothing extra and suffer<br />

much more than his does.<br />

Before the subsistence allowances were cut<br />

by 30 percent on 31 August 2005, UNHCR<br />

gave him and his brother 5,400 baht. Xiong<br />

says his life was okay then; he could buy<br />

food and sometimes clothes. When he first<br />

heard UNHCR was going to cut the subsistence<br />

allowance, he was hoping they<br />

6

THAILAND<br />

to get by in a big city<br />

would help him find work, and it would not<br />

be so bad. For nearly four months he heard<br />

nothing, until last December when someone<br />

from BRC came to interview him.<br />

Xiong told him he would like to work at<br />

home, but he has not heard from them since.<br />

<strong>Now</strong>, there are rumours that UNHCR will<br />

completely cut refugee assistance in 2006.<br />

Xiong cannot find work and does not know<br />

what to do. Naturally, it makes him worry<br />

about his family and others in the same predicament.<br />

“Some families I know have 13 children.<br />

They will really suffer if they can’t get financial<br />

assistance. Where are they going<br />

to live? What will they eat?”<br />

ures, and commits the organisation to providing<br />

food and shelter assistance in order<br />

to meet the basic needs of refugees.<br />

<strong>JRS</strong> Thailand is aware of studies undertaken<br />

on the impact of UNHCR self-reliance<br />

strategies on refugees in New Delhi,<br />

Cairo and Moscow, yet, no such study has<br />

been done in Thailand. Similar in-depth<br />

knowledge of refugees in Bangkok and<br />

other urban areas hosting refugees in Thailand<br />

are simply not available. However,<br />

anecdotal evidence of the effects on <strong>JRS</strong>’<br />

clients is extremely worrying.<br />

The Thai government is not a signatory to<br />

the 1951 UN Refugee Convention. As such,<br />

refugees recognised by UNHCR do not<br />

have legal status in Thailand or the right to<br />

work. Bangkok, an increasingly expensive<br />

middle-income developing city, offers few<br />

opportunities for refugees to earn a living.<br />

Most are not optimistic about the future.<br />

After the allowances were cut, many refugees<br />

frantically began looking for food.<br />

They turned to <strong>JRS</strong> for assistance, particularly<br />

Cambodians and Laotians with large<br />

families. African refugees, for whom it is<br />

even more difficult to find a job in the informal<br />

labour market, desperately sought<br />

to be resettled to a third country. The <strong>JRS</strong><br />

urban refugee programme, established to<br />

assist asylum seekers, responded as best<br />

as it could to the dire situation faced by<br />

many refugees.<br />

One of the official reasons that assistance<br />

to refugees was cut, was to promote selfsufficiency;<br />

an unlikely outcome given that<br />

refugees are prohibited from undertaking<br />

paid employment in the formal labour market.<br />

In response to the dire circumstances<br />

many refugees faced, UNHCR seems to<br />

have reversed its stance. A draft of its revised<br />

policy acknowledges the previous fail-<br />

At the moment, support provided under the<br />

UNHCR Thailand urban refugee programme<br />

is insufficient. If the large budget<br />

cuts announced for 2006 are implemented,<br />

it seems inevitable that further cuts in refugee<br />

subsistence allowances will have to be<br />

implemented. If denied sufficient income<br />

to pay for basic necessities, as in Xiong Pa’s<br />

case, refugees risk being forced to reduce<br />

the amount and quality of food they consume.<br />

Of course, vulnerable refugees, especially<br />

children, will be hit the hardest.<br />

Vera den Otter, Information/<br />

Advocacy Officer, <strong>JRS</strong> Thailand<br />

Laotian<br />

refugee<br />

children in<br />

Thailand<br />

SERVIR No. 37 – March 2006 7

TANZANIA<br />

Between<br />

hunger<br />

and home<br />

Refugee<br />

woman<br />

collecting<br />

firewood<br />

Minh-Chau Le<br />

Agroup of Burundian refugee women<br />

patiently wait for their group leader<br />

to present their ration cards and<br />

collect the sacks of food. In the camps in<br />

northwestern Tanzania, refugees do not<br />

collect their rations individually. On each<br />

street, they are grouped by family size.<br />

Typically, when the leader receives all the<br />

food, the group members assist him, carrying<br />

the sacks and containers out of the<br />

fenced-in area to divide the food.<br />

Busy hands pour oil into individual containers,<br />

measure cups of maize grain and tie sacks of<br />

beans. After collecting her rations, Gloriose<br />

(not her real name) steps away from the group<br />

to balance her family’s 34kg of maize grain<br />

on her head. With an oil can in one hand, and<br />

her 16-month old baby tied to her back, she<br />

leads her 9-year old daughter, Jackie (not her<br />

real name) back to their mud-brick home.<br />

Jackie walks slowly, burdened by 10kg of<br />

beans and porridge flour perched on her head.<br />

Every two weeks, on distribution day, she has<br />

to take the day off school in order to help her<br />

mother. “I don’t mind the weight,” Gloriose<br />

grins, “I wish it was heavier, much heavier!”<br />

When Gloriose’s family receives their full<br />

ration allowance, it still amounts to less than<br />

the recommended minimum of 2,100 calories<br />

per person per day. Even the UN<br />

agency, the World Food Programme (WFP)<br />

acknowledges that people cannot be expected<br />

to survive on such a limited diet.<br />

Tanzanian law and policy prohibits refugees<br />

in these camps from working, undertaking<br />

any form of business activities or being more<br />

than four km away from the camps. It is<br />

essentially impossible for a refugee to abide<br />

by these laws. Not provided with firewood<br />

to cook their rations, they must risk arrest,<br />

police abuse, assault and even rape as punishment<br />

for simply leaving the camps to collect<br />

it, or buying it from those who do. In<br />

addition, the maize grain provided, a main<br />

staple of their limited diet, is not in an edible<br />

form; it must be milled into maize flour.<br />

Gloriose can only feed her family by spending<br />

about 2,500 shillings, just over two euros,<br />

on firewood and 700 shillings to mill the<br />

grain every two weeks. To do this, a refugee<br />

without income would be forced to sell<br />

8

TANZANIA<br />

some rations. Oil is the first thing to be sold,<br />

and Gloriose could get 1,200 shillings for<br />

her ration of oil. For the remaining 2,000<br />

shillings she would have to sell approximately<br />

10kg of her maize flour.<br />

If Gloriose did this, it would be literally impossible<br />

to survive on that amount of food.<br />

Therefore, Gloriose’s family breaks Tanzanian<br />

law on a regular basis. Her husband<br />

works for local Tanzanian farmers and receives<br />

600 shillings per day. Though the<br />

income is less than 10 euros per month, it is<br />

enough to buy the firewood and pay for<br />

milling the maize.<br />

Occasionally, she will also venture up to 10km<br />

outside of the camp to collect wood, especially<br />

when the family needs to save money<br />

to buy clothes, furniture or pay school fees.<br />

The money also buys onions and tomatoes<br />

for the bean stew her family eats almost daily,<br />

as well as some cassava and bananas, which<br />

the family enjoys for variety.<br />

“They expect us to eat boiled beans and ugali<br />

(maize bread) every day, sometimes without<br />

even salt. Could you do that for 12<br />

years?” Breaking the law is the only way to<br />

survive. But recently, Gloriose and her husband<br />

have considered another way. “Things<br />

are becoming unbearable,” she shakes her<br />

head. “The camp is insecure. Children die<br />

from malaria. And the rations go up and<br />

down, but we are the last to know”. Her<br />

husband, Zenon (not his real name), interrupts,<br />

“maybe we must leave the camp, and<br />

go back to Burundi”.<br />

Though some families are able to save considerable<br />

amounts of money, food, rent and<br />

are even able to cultivate land outside the<br />

camp, Gloriose’s family survives from food<br />

distribution to food distribution. They have no<br />

insurance for periods when rations are cut.<br />

In 2005, when rations were cut to only 67<br />

percent of the norm, Gloriose says, “we borrowed<br />

money for food. I went to collect firewood<br />

everyday to sell it. It was a bad time”.<br />

Though rations have since stabilised, they<br />

remain unreliable. For refugees like Gloriose,<br />

food insecurity is a push factor. Though repatriation<br />

should be completely voluntary,<br />

insufficient rations force refugees to consider<br />

going home as a survival technique,<br />

not a choice. One of Gloriose’s neighbours<br />

commented: “It is better to return and die<br />

from a gunshot than being threatened to<br />

death by hunger...” Inadequate rations<br />

threaten refugees in ways much more complicated<br />

than just calories. Community service<br />

officials in the camps have informed <strong>JRS</strong><br />

staff that stress caused from inadequate<br />

rations increases the likelihood of domestic<br />

violence and abuse.<br />

Better ration levels from WFP would certainly<br />

help the situation, but it is still a solution<br />

that would leave Gloriose and her family<br />

at the mercy of others. Refugee leaders<br />

agree the best solution would be to allow<br />

refugees to work and start businesses and<br />

become self-sufficient. This would avoid<br />

over dependence on international food aid,<br />

which has never been very reliable.<br />

Minh-Chau Le, Public<br />

Relations Officer, Radio<br />

Kwizera, <strong>JRS</strong> Tanzania<br />

Refugee child<br />

collecting food<br />

SERVIR No. 37 – March 2006 9

SUDAN<br />

Food or<br />

Emer Kerrigan<br />

Gulu,<br />

northern<br />

Uganda,<br />

near Sudan<br />

Lobone, seven kilometres from the northern<br />

Uganda border, is now home to many<br />

displaced communities from the recently<br />

ended 21-year-long war between the<br />

Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army<br />

and the government of Sudan.<br />

The 1994 war displaced many Dinka people<br />

south to Lobone. As many as four-fifths of<br />

the 33,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs)<br />

in Lobone are Dinka. Families were forced to<br />

leave their cattle behind and turn to crop cultivation<br />

as the main source of food. Inadequate<br />

farming methods and an over-reliance on three<br />

crops has had a damaging effect on the nutrition<br />

of the community. Malnutrition rates have<br />

risen causing children to be regularly admitted<br />

to the local hospital and mothers to miss adult<br />

literacy classes to take care of sick relatives.<br />

In 2001, <strong>JRS</strong> began providing communities with<br />

education and pastoral services, including guidance,<br />

schools materials and financial support<br />

to teachers. Consequently, education has flourished<br />

in the area in recent years. Standards rise<br />

annually and currently Lobone accommodates<br />

seven primary schools, one secondary school,<br />

11 nursery schools and nine adult literacy centres,<br />

with a student population of nearly 8,000.<br />

Despite an abundance of fertile land in Lobone<br />

and the increasing availability of education,<br />

food insecurity remains a threat to the community.<br />

It affects all aspects of education, influencing<br />

the attendance of adults and children<br />

and the intellectual development of children.<br />

The vast majority of people in the area survive<br />

directly on what they grow; few individuals<br />

have the training or education to earn<br />

an income elsewhere. Cultivation and harvesting<br />

seasons are crucial to the survival of<br />

the family. During these periods, children and<br />

mothers, who form the vast majority of adult<br />

learners, stay off school to work. Moreover,<br />

between May and July, school attendance is<br />

also poor as food runs short in the community<br />

and the students are forced to go to<br />

Uganda in search of food.<br />

One means of addressing food insecurity is<br />

through the school meals programme facilitated<br />

jointly by Catholic Relief Services and<br />

<strong>JRS</strong>. The programme encourages the children<br />

to stay in school until the lunch hour and provides<br />

them with nutrition which may not be<br />

available at home. This food is crucial to their<br />

cognitive development and contributes to the<br />

improvement in the children’s attention span.<br />

Many of the students are orphans and reside<br />

with extended families. Providing their own<br />

lunches to take to school would place an excessive<br />

strain on their extended families.<br />

Nevertheless, the delivery of food is occasionally<br />

delayed. Food can only be transported<br />

on one road from Uganda which is<br />

frequently attacked by the Ugandan rebel<br />

group, the Lord’s Resistance Army. Due to<br />

the attacks, school attendance is immediately<br />

affected, often decreasing by as much as<br />

three quarters.<br />

The future of education of the internally displaced<br />

community in Lobone is entirely dependent<br />

on the food security in the area.<br />

Although education is valued for its long-term<br />

benefits, it is the basic and immediate need<br />

of food that is the most influential determinant<br />

to the success of the education programme<br />

in Lobone.<br />

Emer Kerrigan,<br />

Administrator,<br />

<strong>JRS</strong> Sudan<br />

10

NAMIBIA<br />

school<br />

Joanne Whitaker RSM<br />

Osire Refugee Camp, central Namibia,<br />

is home to about 23,000 refugees,<br />

mostly Angolans. One day during<br />

the school year, our <strong>JRS</strong> team made its usual<br />

visit. It was late morning when we arrived<br />

and went directly to the primary school. We<br />

discovered many of the children were absent.<br />

Most were standing in the queue to receive<br />

their monthly food rations or assisting<br />

their families and others to collect their rations.<br />

Those who were not in the queue were<br />

busy working, transporting heavy loads of<br />

maize or cooking oil from the distribution point<br />

back to the camp. Distribution usually occurrs<br />

once a month, but often more.<br />

to ask for assistance and set up a project for<br />

girls between the ages of 10 to 20 called the<br />

Osire Girls Club. The purpose of the club was<br />

to help girls stay in school by offering extracurricular<br />

activities, including some supplemental<br />

food supplies which could be taken to<br />

their families. These efforts, while not completely<br />

successful, did significantly reduce<br />

girls’ absence and withdrawal from school.<br />

We felt powerless. Families needed assistance.<br />

Many students used the opportunity to<br />

supplement their rations. We needed to face<br />

reality and to plan lessons and exams for days<br />

when the children would not be needed to<br />

collect the food.<br />

An even more disturbing reality was the complete<br />

withdrawal of children from school, especially<br />

girls, to assist the family in getting<br />

food. They would work in the family’s garden<br />

or stay at home to take care of younger<br />

children while the adults looked for work on<br />

nearby farms or wherever they could find<br />

some temporary work. Work outside the camp<br />

often created problems for the refugees. The<br />

government did not allow refugees to work.<br />

In some cases, farmers would not pay the<br />

refugees and tell them to get off their farm or<br />

they would report them to the police for trespassing<br />

and stealing their cattle. Girls, especially<br />

those alone in the camp without parents,<br />

would sometimes end up being sexually exploited<br />

for money. In fact, this even happened<br />

to girls with parents. The parents would be<br />

forced to accept their daughter’s prostitution<br />

out of desperation. Once this started, the girls<br />

almost never returned to school.<br />

Again, finding an effective response to this<br />

problem was difficult. <strong>JRS</strong> met with teachers,<br />

parents, and camp leaders to raise the<br />

issue as one of major concern. We had meetings<br />

with the police and camp administration<br />

Namibia is not unique. The choice – food or<br />

school – occurs throughout southern Africa,<br />

and, indeed, across the continent. In fact in<br />

neighbouring Zambia, the UN agency, the<br />

World Food Programme has reduced food<br />

rations for refugees and estimates that, unless<br />

donations increase, they will be forced<br />

to cease food distribution to refugees in March<br />

2006. It is an ongoing dilemma, not only<br />

among refugees and asylum seekers, but for<br />

many young people affected by poverty and<br />

made orphans by AIDS.<br />

Joanne Whitaker RSM,<br />

Regional Director,<br />

<strong>JRS</strong> Southern Africa<br />

Sudanese<br />

refugee,<br />

Kejokeji,<br />

southern<br />

Sudan<br />

SERVIR No. 37 – March 2006 11

How to help one person<br />

The mission of <strong>JRS</strong> is to<br />

accompany, serve and<br />

defend the rights of refugees<br />

and forcibly displaced people,<br />

especially those who are<br />

forgotten about and who do<br />

not attract international<br />

attention. We do this through<br />

our projects in over 50<br />

countries world-wide,<br />

providing assistance in the<br />

form of education, health care,<br />

pastoral work, skills training,<br />

income generating activities<br />

and many more services to the<br />

refugees.<br />

<strong>JRS</strong> relies for the most part on<br />

donations from private<br />

individuals and development<br />

and church agencies.<br />

Here are some examples<br />

of how <strong>JRS</strong> funds are used:<br />

• To provide education for a child<br />

for a year in a community primary<br />

school in Yei, Sudan<br />

$30 US<br />

• To provide legal counselling to an<br />

asylum seeker or a refugee for a<br />

year in Bangkok, Thailand<br />

$31 US<br />

• To give medical assistance to a refugee<br />

for a year in Harare, Zimbabwe<br />

$37 US<br />

• To construct a house for a person<br />

with a landmine-related disability<br />

and their family in Cambodia<br />

$400 US<br />

• To provide a workshop on human<br />

rights for internally displaced<br />

persons in Colombia<br />

$450 US<br />

• To produce and transmit for one<br />

week a radio programme on<br />

peace & reconciliation in northwestern<br />

Tanzania<br />

$1,120 US<br />

SUPPORT OUR WORK WITH REFUGEES<br />

Your continued support makes it possible for us to help refugees and asylum<br />

seekers in over 50 countries. If you wish to make a donation, please fill in this<br />

coupon and forward it to the <strong>JRS</strong> International office. Thank you.<br />

(Please make cheques payable to Jesuit Refugee Service)<br />

I want to support the work of <strong>JRS</strong><br />

Servir is published in March,<br />

September and December by<br />

the Jesuit Refugee Service,<br />

established by Pedro<br />

Arrupe SJ, in 1980.<br />

<strong>JRS</strong>, an international Catholic<br />

organisation, accompanies,<br />

serves, and advocates the<br />

cause of refugees and<br />

forcibly displaced people.<br />

Publisher: Lluís Magriñà SJ<br />

Editor: James Stapleton<br />

Production: Stefano Maero<br />

Assistant Production:<br />

Sara Pettinella<br />

Servir is available free in<br />

English, Spanish, French<br />

and Italian.<br />

e-mail: servir@jrs.net<br />

write: Jesuit Refugee Service<br />

C.P. 6139<br />

00195 Roma Prati<br />

ITALY<br />

tel: +39 06 6897 7386<br />

fax: +39 06 6880 6418<br />

Dispatches, a twice monthly<br />

news bulletin from the <strong>JRS</strong><br />

International Office detailing<br />

refugee news briefings and<br />

updates on <strong>JRS</strong> projects and<br />

activities, available free by<br />

e-mail in English, Spanish,<br />

French or Italian.<br />

To subscribe to Dispatches:<br />

http://www.jrs.net/lists/manage.php<br />

Cover photo:<br />

Tanzania.<br />

Photo by Mark Raper SJ/<strong>JRS</strong>.<br />

Please find enclosed a donation of<br />

My cheque is attached<br />

Surname:<br />

Address:<br />

City:<br />

Country:<br />

Name:<br />

Post Code:<br />

Photo credits:<br />

Francesco Spotorno (pgs 2 above, 4);<br />

Nina Rücker (pg. 3);<br />

<strong>JRS</strong> Colombia (pg. 5); Noparat<br />

Thiannimitdomrong/<strong>JRS</strong> (pg. 6);<br />

Jan Cooney/<strong>JRS</strong> (pg. 7);<br />

Libby Rogerson IBVM/<strong>JRS</strong> (pg. 8);<br />

Mark Raper SJ/<strong>JRS</strong> (pgs 9, 12);<br />

Don Doll SJ/<strong>JRS</strong> (pgs 10, 11).<br />

Telephone:<br />

Fax:<br />

Email:<br />

12<br />

Bank:<br />

Account name:<br />

Account numbers:<br />

For bank transfers to <strong>JRS</strong><br />

Banca Popolare di Sondrio, Roma (Italy), Ag. 12<br />

ABI: 05696 – CAB: 03212 – SWIFT: POSOIT22<br />

<strong>JRS</strong><br />

• for Euro: 3410/05<br />

IBAN: IT 86 Y 05696 03212 000003410X05<br />

• for US dollars: VAR 3410/05<br />

IBAN: IT 97 O 05696 03212 VARUS0003410<br />

www.jrs.net