Hdt GLOW09 vf - Mohamed Lahrouchi

Hdt GLOW09 vf - Mohamed Lahrouchi

Hdt GLOW09 vf - Mohamed Lahrouchi

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Consonantal root extraction in two secret languages<br />

in Tashlhiyt Berber<br />

<strong>Mohamed</strong> <strong>Lahrouchi</strong> & Philippe Ségéral<br />

(CNRS-Université Paris 8)<br />

(Université Paris 7-CNRS)<br />

(1) Root in Afroasiatic, a controversial object<br />

a. From linguists of the Middle Ages (Sibawayh) to McCarthy (1979, 1981), Frost et<br />

al. 2000, Prunet et al. 2000, Prunet 2006, Idrissi et al. 2008, etc.:<br />

The root is a grammatical morpheme entirely made of consonants<br />

Words are built on consonantal roots<br />

b. Ratcliffe 1987, Hammond 1988, Dell & Elmedlaoui 1992, Bat-El 1994, Ussishkin<br />

1999, etc.:<br />

No need of such an abstract morpheme, words are derived from other words<br />

(2) Data to be studied: two secret languages used by women in Tashlhiyt Berber (TShl):<br />

a. Taqjmit (TQJM) (original data, <strong>Lahrouchi</strong> & Ségéral in press), Isouktane south-west<br />

Morocco<br />

b. Tagnawt (TGNW) (data from Douchaïna 1996, 1998), Tiznit south-west Morocco<br />

(3) Our claim: the root is a grammatical morpheme to which speakers have access. TQJM and<br />

TGNW formations show that speakers are able to<br />

a. extract the root-morpheme from any Tashlhiyt form<br />

b. build root-morphemes of a definite shape (triconsonantal)<br />

I. Extracting the root-morpheme = (3a)<br />

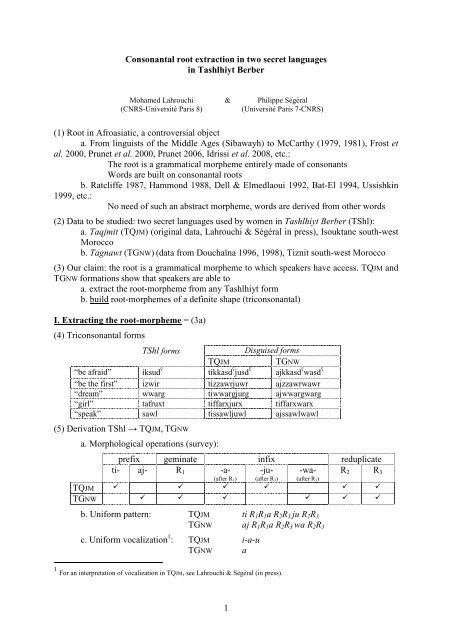

(4) Triconsonantal forms<br />

TShl forms<br />

Disguised forms<br />

TQJM<br />

TGNW<br />

“be afraid” iksud ÷ tikkasd ÷ jusd ÷ ajkkasd ÷ wasd ÷<br />

“be the first” izwir tizzawrjuwr ajzzawrwawr<br />

“dream” wwarg tiwwargjurg ajwwargwarg<br />

“girl” tafruxt tiffarxjurx tiffarxwarx<br />

“speak” sawl tissawljuwl ajssawlwawl<br />

(5) Derivation TShl → TQJM, TGNW<br />

a. Morphological operations (survey):<br />

prefix geminate infix reduplicate<br />

ti- aj- R 1 -a- -ju- -wa- R 2 R 3<br />

(after R 1) (after R 3) (after R 3)<br />

TQJM <br />

TGNW <br />

b. Uniform pattern: TQJM ti R 1 R 1 a R 2 R 3 ju R 2 R 3<br />

TGNW aj R 1 R 1 a R 2 R 3 wa R 2 R 3<br />

c. Uniform vocalization 1 : TQJM i-a-u<br />

TGNW a<br />

1 For an interpretation of vocalization in TQJM, see <strong>Lahrouchi</strong> & Ségéral (in press).<br />

1

d. Repetition: each root-consonant is repeated twice<br />

two operations: gemination and reduplication<br />

TQJM / TGNW R 1 R 2 R 3<br />

i. gemination always never never<br />

ii. reduplication never always always<br />

(6) Template<br />

a. TQJM<br />

t<br />

R 1 R 2 R 3 R 2 R 3<br />

I<br />

C v C v C v C v C v C v C v C v C v C v C v<br />

b. TGNW<br />

I A U<br />

I<br />

R 1 R 2 R 3 R 2 R 3<br />

U<br />

C v C v C v C v C v C v C v C v C v C v C v C v<br />

A<br />

The template is the same, encoding the various operations observed in the disguised<br />

forms as well as the principle of repetition (the additional Cv in TGNW hosts the vocalic<br />

material of the prefix).<br />

Note: in (6a-b), peripheral vowels are assumed to be underlyingly long, associated to two<br />

vocalic slots (cf. Lowentamm 1991 and Bendjaballah 2001, 2004). Evidence for this<br />

assumption will come at the close of the analysis of TGNW.<br />

(7) Only root consonants are kept<br />

a. Any vocalic material of the input (TShl) is deleted in the disguised form. Whatever<br />

the original vocalism is, the disguised form vocalizes uniformly as in (5c).<br />

TShl<br />

TQJM<br />

tafruxt a u tiffarxjurx “girl”<br />

agudi a u i tiggadjudi “a lot”<br />

i a u<br />

isliw i tissalwjulw “be soft”<br />

argaz a tirragzjugz<br />

“man”<br />

TShl<br />

TGNW<br />

t-afrux-t a u ajffarxwarx “girl”<br />

md≥uru u ajmmad≥rwad≥r “feel better”<br />

a<br />

iz≥duj i u ajzz≥adwaddi “be heavy”<br />

imz≥ij i ajmmaz≥wazz≥i<br />

“be small”<br />

2

. Any affixal material of the input is deleted in the disguised form (e.g. i- 3ms<br />

marker, t-…-t feminine marker, n- reciprocal marker, l- definite article and m- participial<br />

marker in Arabic).<br />

TShl<br />

TQJM<br />

t-afrux-t tiffarxjurx “girl”<br />

t-amƒar-t timmaƒrjuƒr “woman”<br />

l-axbar tixxabrjubr “news”<br />

m-bark tibbarkjurk Proper noun<br />

TShl<br />

TGNW<br />

t-aknari-t ajkkanrwanr “prickly pear”<br />

t-afrux-t ajffarxwarx “girl”<br />

n-s≥br ajss≥abrwabr “we wait, endure”<br />

l-ħml ajħħamlwaml “load”<br />

(8) The same holds for bi- and monoconsonantals as well. See examples below, part II.<br />

II. Building the root-morpheme = (3b)<br />

(9) Triliterality condition and its consequences:<br />

a. all items in TQJM and TGNW contain three radical consonants. The "lexicon" of<br />

TQJM and TGNW is entirely composed of triconsonantal roots.<br />

b. the root material inherited from Tshl is variable : Tshl roots are mono-, bi-, tri- and<br />

quadriconsonantal. Hence, repair strategies:<br />

• First case: TShl input has three radicals<br />

→ all three are kept in TQJM and TGNW, see examples in (4) and (7)<br />

• Second case: TShl input has more than three radicals (4 R’s)<br />

→ the number of consonants is reduced to three 2<br />

• Third case: TShl input has less than three radicals<br />

→ TGNW: epenthesis provides the missing radicals<br />

→ TQJM: vocalic and affixal I / U are redeployed as radical material<br />

(10) Quadriconsonantals: one consonant is dropped in the disguised form, always R 2 or R 4 :<br />

TShl<br />

TQJM<br />

brahim b r h m tibbarhjurh b r h m proper noun<br />

kltum k l t m tikkatmjutm k l t m id.<br />

TShl<br />

TGNW<br />

gʒdr g ʒ d r ajggaʒdwaʒd g ʒ d r “moan”<br />

aglzim g l z m ajggazmwazm g l z m “pickaxe”<br />

asrdun s r d n ajssadnwadn s r d n “mule”<br />

asngar s n g r ajssagrwagr s n g r “corn”<br />

2 In TGNW, not all TShl quadriconsonantal words loose one root consonant. Some keep all their radical consonants, but one<br />

of these consonants, namely R 2 , is not repeated, and the melody obtained in this case, and only in this case, contains ə after<br />

the geminated R 1 : e.g. ggrml / ajggərmlwaml “be crusty”, agnfur / ajggənfrwafr “face”, iħnbl / ajħħənblwabl “blanket”. The<br />

systematic appearance of ə instead of a in these forms is explained in <strong>Lahrouchi</strong> & Ségéral (submitted) as the result of the<br />

association of four radicals to a template that offers only three radical positions, and the necessary association of peripheral<br />

vowels to two V positions. Once the whole material is associated to the template, the vowel A preceding R 2 does no longer<br />

surface as [a] since it has access to only one V position. Depending on phonotactic conditions, the remaining V position<br />

surfaces as [ə].<br />

3

(11) Bi- and monoconsonantals<br />

TShl TQJM<br />

bi- gn tigganjuni “sleep”<br />

ƒr tiƒƒarjuri “read”<br />

igr tiggarjuri “field”<br />

ils tillasjusi “tongue”<br />

mono- af tiffawiwi “find”<br />

asi tissawiwi “take”<br />

ini tinnawiwi “say”<br />

immi timmawiwi “my mother”<br />

TShl TGNW<br />

bi- ad≥n ajttad≥nwad≥n “be sick”<br />

i-fl ajffalwalli “he let”<br />

sala ajssalwalli “be involved”<br />

kl ajkkalwalli “spend the day”<br />

mono- i-zz≥a ajzz≥atwatti “he chases after”<br />

kk ajkkatwatti “pass by”<br />

t-ʒʒi-t ajʒʒatwatti “you recovered”<br />

is ajssatwatti interrogative “do...?”<br />

a. TQJM: the affixal material I and U (which surface as ju in tri- and quadriconsonantals)<br />

compensate for the missing radicals: I compensates for the missing R 3 in<br />

biconsonantal inputs. U and I compensate for the missing R 2 and R 3 in monoconsonantal<br />

inputs.<br />

b. TGNW: t or I compensate for the missing radical in biconsonantal inputs (t- replaces<br />

R 1 ; I replaces R 3 ) t and I compensate for the missing R 2 and R 3 in monoconsonantal inputs.<br />

(12) TQJM<br />

a. biconsonantal gn → tigganjuni<br />

g n n<br />

t I I<br />

C v C v C v C v C v C v C v C v C v C v C v<br />

I A U<br />

4

. monoconsonantal g → tiggawiwi<br />

g<br />

t U I U I<br />

C v C v C v C v C v C v C v C v C v C v C v<br />

I<br />

A<br />

(13) TGNW<br />

a. biconsonantal adɭn → ajttadɭnwadɭn<br />

I<br />

t dɭ n dɭ n<br />

U<br />

C v C v C v C v C v C v C v C v C v C v C v C v<br />

b. monoconsonantal is → ajssatwatti<br />

A<br />

s t t<br />

I I U I<br />

C v C v C v C v C v C v C v C v C v C v C v C v<br />

A<br />

Note: in (13b), the epenthetic I does surface in the position normally identified by the first<br />

instance of R 3. The same happens in triconsonantal forms such as ajzz≥adwaddi ← iz≥duj<br />

“be heavy” and ajmmaz≥wazz≥i ← imz≥ij “be small”, where the final I surfacing as [j] is<br />

lexical. is does not lead to *ajssatjwati just as iz≥duj does not lead to *ajzz≥adjwadi.<br />

However, in both cases the copy of R 2 is geminated. This is analysed as a compensation of<br />

the non-appearance of I in the first instance of R 3 .<br />

(14) How do word-based models can account for these phenomena?<br />

5

References<br />

Bat-El, O. 1994. Stem modification and cluster transfer in Modern Hebrew. Natural<br />

Language and Linguistic Theory 12: 571-596.<br />

Dell, F. & Elmedlaoui, M. 1992. Quantitative transfer in the nonconcatenative morphology of<br />

Imdlawn Tashlhiyt Berber. Journal of African Languages and Linguistics 3: 89-125.<br />

Douchaïna, R. 1996. Tagnawt, un parler secret des femmes berbères de Tiznit (sud-ouest marocain).<br />

PhD, Paris: INALCO.<br />

Douchaïna, R. 1998. La morphologie du verbe en tagnawt. Etudes et Documents Berbères<br />

15/16: 197-209.<br />

Frost, R., Deutsch, A., & Forster, K. 2000. Decomposing morphologically complex words in<br />

nonlinear morphology. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and<br />

Cognition 26: 751-765.<br />

Idrissi, A., Prunet, J-F. & Béland, R. 2008. On the mental representation of Arabic roots.<br />

Linguistic Inquiry 39/2: 221-259.<br />

Hammond, M. 1988. Templatic transfer in Arabic broken plurals. Natural Language and<br />

Linguistic Theory 6: 247-270.<br />

<strong>Lahrouchi</strong>, M & P. Ségéral. In press. Morphologie gabaritique et apophonie dans un langage<br />

secret féminin (Taqjmit) en berbère tachelhit. Revue canadienne de Linguistique /<br />

Canadian Journal of Linguistics 54.2 (37 pp.).<br />

<strong>Lahrouchi</strong>, M & P. Ségéral. Submitted. Peripheral vowels in Tashlhiyt Berber are<br />

phonologically long: evidence from Tagnawt, a secret language used by women. Brill’s<br />

Annual of Afroasiatic Languages and Linguistics.<br />

McCarthy, J. 1979. Formal Problems in Semitic Phonology and Morphology. PhD, MIT.<br />

McCarthy, J. 1981. A prosodic Theory of Nonconcatenative Morphology. Linguistic Inquiry<br />

12: 373-418.<br />

Prunet, J-F. 2006. External evidence and the Semitic root. Morphology 16: 41-67.<br />

Prunet, J-F., Béland, R. & Idrissi, A. 2000. The mental representation of Semitic words.<br />

Linguistic Inquiry 31/4: 609-648.<br />

Ratcliffe, R. 1987. Prosodic templates in a word-based morphological analysis of Arabic. In.<br />

M. Eid & R. Ratcliffe (eds) Perspectives on Arabic Linguistics X, Current Issues in<br />

Linguistic Theory 153: 147-171, Amsterdam / Philadephia: John Benjamins.<br />

Ussishkin, A. 1999. The inadequacy of the consonantal root: Modern Hebrew denominal<br />

verbs and output-output correspondence. Phonology 16: 401-442.<br />

6