Legends Of Jazz Guitar - Stefan Grossman's Guitar Workshop

Legends Of Jazz Guitar - Stefan Grossman's Guitar Workshop

Legends Of Jazz Guitar - Stefan Grossman's Guitar Workshop

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

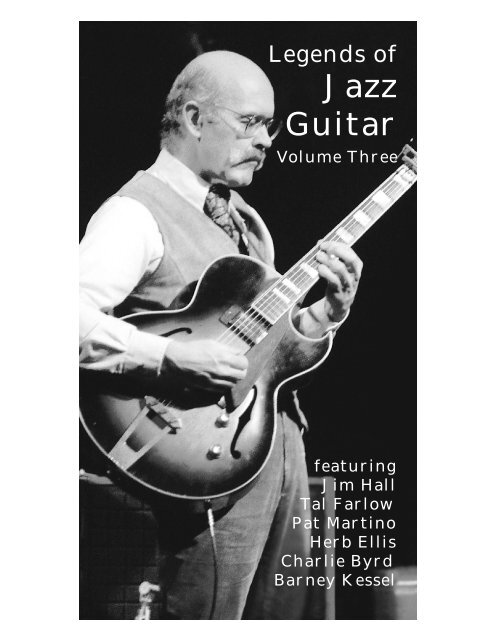

<strong>Legends</strong> of<br />

<strong>Jazz</strong><br />

<strong>Guitar</strong><br />

Volume Three<br />

featuring<br />

Jim Hall<br />

Tal Farlow<br />

Pat Martino<br />

Herb Ellis<br />

Charlie Byrd<br />

Barney Kessel

LEGENDS OF JAZZ GUITAR<br />

VOLUME THREE<br />

by Mark Humphrey<br />

Funny how unlikely couples get together. Take, for<br />

instance, the guitar and jazz. The guitar, rooted somewhere<br />

in Moorish Spain and Americanized as a ladies’<br />

parlor instrument or a cowboy’s companion, is not by<br />

its acoustic nature a convincing surrogate horn. <strong>Jazz</strong>,<br />

rooted in African polyrhythms and nurtured in Southern<br />

brass bands, is seemingly too raucously aggressive<br />

to keep company with a delicately-strung wooden box.<br />

But leave it to imaginative musicians and instrument<br />

makers to find ways around such contradictions. If the<br />

guitar was ever an anomaly in jazz it ceased to be long<br />

ago. Can you even imagine the idiom without the guitar’s<br />

voluble presence? A key player in the band would be<br />

missing.<br />

The six men seen and heard in this video are among<br />

the most exemplary band members to choose the guitar<br />

as their means of expression. The initial inspiration<br />

for most of them was Charlie Christian, who blazed trails<br />

jazz guitarists still tred a half century later. Christian<br />

swung in the direction of bop, and his disciples (foremost<br />

among whom are seen here) boldly carried the<br />

guitar into that next phase of jazz. Aside from their fervor<br />

for the potential of the guitar in the evolution of jazz,<br />

many of these artists have similar backgrounds: Southern<br />

or Southwestern, and of roughly the same generation.<br />

But their individuality is abundantly clear in performances<br />

ranging from meditative ballads to speedof-sound<br />

boppers. Underlying it all is an exhilarating<br />

sense of triumph over that apparent oxymoron, jazz<br />

guitar. Having proven that the guitar is indeed a first<br />

rate medium for jazz expression, these artists confidently<br />

address other contradictions, ones involving evolution<br />

within a well-grounded tradition. They’re serious about<br />

their business, but you can see them having fun with it,<br />

too.<br />

2

3<br />

Photo by Tom Copi

JIM HALL<br />

This collection of performances opens with a George<br />

Bassman – Ned Washington ballad which was the theme<br />

of the Tommy Dorsey Orchestra. Jim Hall, who played<br />

“I’m Getting Sentimental Over You” for the BBC in 1964,<br />

told <strong>Guitar</strong> Player five years later: “I enjoy ballads, standards.<br />

By standards, I mean I enjoy things with chord<br />

progressions more than ‘open free’ music. I also like<br />

medium swing tempos.”<br />

A year older than 1932’s “I’m Getting Sentimental<br />

Over You,” Hall says he was “brought up in the Baptist<br />

Midwestern environment of Cleveland, Ohio.” He started<br />

playing guitar at age ten; like most jazz guitarists of his<br />

generation, Hall had a ‘Damascus road’ experience with<br />

Charlie Christian. “The first time I heard him I was 13<br />

years old,” he told down beat’s Mitchell Seidel, “and it<br />

changed my life.” The performance that bowled Hall over<br />

was “Grand Slam.” Half a century later, Hall says<br />

Christian’s style “sounds old and brand-new at the same<br />

time.”<br />

Though determined to play jazz guitar, Hall says<br />

“Baptist guilt” drove him to earn a Bachelor of Music<br />

degree from the Cleveland Institute of Music. “I was actually<br />

being primed to become a music teacher or composer,”<br />

Hall told down beat’s Bill Milkowski, but the prospect<br />

of an exclusively academic life prompted him to<br />

drop out before attaining his master’s degree and head<br />

for Los Angeles. Still, Hall deems his formal training a<br />

plus: “I could read music fairly well for a guitar player,”<br />

he says (he wrote a string quartet as his thesis). “When<br />

I was in music school,” Hall told <strong>Guitar</strong> Player’s Jim<br />

Ferguson, “I heard everything from Gregorian chant to<br />

12-tone and electronic music, which was pretty new<br />

back then. It opened my view of what music could be.”<br />

Hall arrived in Los Angeles in 1955 and simultaneously<br />

studied classical guitar with Vicente Lopez while<br />

hanging out on the jazz scene. If Hall was initially unsure<br />

of his direction, a work call from drummer Chico<br />

Hamilton changed that. Still, he insists his classical training<br />

left its mark. “I keep my strings lighter than most,”<br />

4

Photo by Tom Copi<br />

Hall told Seidel.<br />

“Part of that was trying<br />

to get a classical<br />

guitar sound out of<br />

this instrument... My<br />

sound is a combination<br />

of Charlie Christian<br />

and classical<br />

guitar.”<br />

Hall’s jazz baptism<br />

with Hamilton<br />

was followed by a<br />

challenging stint<br />

with saxophonist/<br />

clarinetist Jimmy<br />

Guiffre (“It cost me<br />

a few hairs, but it<br />

was worth it,” he<br />

says) and work accompanying<br />

the supreme<br />

chanteuse of jazz, Ella Fitzgerald. “Playing with<br />

singers,” Hall told Norman Mongan, “gave me a sense<br />

of space, a way of placing notes in relation to the lyrics,<br />

which is quite different from accompanying another<br />

instrument.”The way Hall ‘breathes’ is heard to good<br />

effect in both “I’m Getting Sentimental Over You” and<br />

“My Funny Valentine.”<br />

By the late 1950s, Hall’s services were in demand<br />

by such legends as tenor saxophonist Ben Webster and<br />

pianist Bill Evans. Hall considers his 1961 stint with tenor<br />

saxophonist Sonny Rollins an exhilarating career highlight:<br />

“He inspired me more than any other musician I<br />

had played with up to then,” says Hall. Rollins is the<br />

composer of “Valse Hot,” which Hall performed for the<br />

BBC in 1964 as a member of the Art Farmer Quartet.<br />

With Farmer’s distinctive fluegelhorn to the fore, Hall,<br />

bassist Steve Swallow and drummer Pete La Roca made<br />

a striking ensemble. (Swallow and La Roca accompanied<br />

Hall on “I’m Getting Sentimental Over You.”) His<br />

instrument in this group was a single pickup Gibson ES-<br />

175 which had previously belonged to Howard Roberts.<br />

5

“What I do best,” Hall has said, “is react to other<br />

musicians.” In 1965; he realized that drink was slowing<br />

his reactions, so he retired, got sober, and spent the<br />

next three and-a-half years in the house band of the<br />

Merv Griffin Show. “That always sounds like a confession<br />

when I mention it now,” Hall quips of his television<br />

job. When the Griffin show moved from New York to<br />

California, Hall didn’t. He began performing with bassist<br />

Ron Carter and gradually worked his way back into<br />

doing what he loves most, playing jazz. Twenty two years<br />

after the BBC performances, we find Hall in Denmark<br />

for a rendition of the Rodgers and Hart classic, “My<br />

Funny Valentine” from the 1937 musical Babes in Arms.<br />

Joining him is the extraordinary French pianist Michel<br />

Petrucciani, whose height (less than three feet) is no<br />

measure of his talent. Hall toured Europe with<br />

Petrucciani in 1986, and told down beat’s Bill Milkowski:<br />

“Michel’s such a wonderful player and makes it easy<br />

because he listens so hard and reacts so fast. To me,<br />

that’s really the gist of playing together. It all boils down<br />

to whether or not the guys listen to one another, and<br />

Michel does that very well.”<br />

Hall has been called “the most romantic and subtle<br />

of the modern guitarists,” but he has also challenged<br />

himself in recent years by collaborating with such<br />

progressives as Bill Frisell and John Abercrombie.<br />

“These younger guys always inspire me, says Hall,<br />

whose first solo guitar album (Dedications & Inspirations,<br />

Telarc) appeared in 1994. “I’m sure that it’s never over,”<br />

Hall told Mitchell Seidel, “at least it certainly isn’t for<br />

me. I practiced today already, and if I don’t, it’s like<br />

somebody stepped on my hand. That’s another one of<br />

the beauties of it-that it goes on forever.”<br />

6

BARNEY KESSEL, HERB ELLIS,<br />

AND CHARLIE BYRD<br />

“THE GREAT GUITARS”<br />

Photo by Tom Copi<br />

In 1973, Australian jazz promoter Kim Bonythan<br />

brought Barney Kessel, Herb Ellis, and Charlie Byrd to<br />

Australia and New Zealand for a nine-concert tour. “The<br />

promoter wanted Herb and me to play the first part of<br />

the concert, Charlie and his group the second, and all<br />

of us together for the finale,” Kessel told <strong>Guitar</strong> Player’s<br />

Robert Yelin. “It was a lot of fun playing with them,”<br />

Byrd told Frets editor Jim Hatlo, “and the audiences<br />

really responded to the way we were enjoying ourselves.<br />

So we decided to keep it going.” The tour launched The<br />

Great <strong>Guitar</strong>s, a group which gave new meaning to the<br />

term ‘power trio.’ Drawing on a combined 90 years of<br />

professional experience, The Great <strong>Guitar</strong>s featured inspired<br />

dialogues among three of jazz guitar’s most fluent<br />

voices.<br />

The most outspoken of these voices is Barney<br />

Kessel. The son of an immigrant Russian Jewish<br />

bootmaker, Kessel was born in Muskogee, Oklahoma<br />

in 1923. He grew up hearing cowboy songs like “Rye<br />

Whiskey” and old hymns strummed on guitar. When he<br />

was 12, he bought a guitar complete with strings, a pick,<br />

and an instruction book for one dollar. Tutored by Charlie<br />

7

Keoube in a Federal Music Project of the WPA, Kessel<br />

received a three-month ‘crash course’ in guitar and<br />

music theory in 1935. Two years later, Kessel was playing<br />

well enough to join an otherwise black jazz band. It<br />

was there he first heard the name Charlie Christian.<br />

By the time he actually met Christian in 1940, Kessel<br />

had listened intently to that pioneer’s work with Benny<br />

Goodman and thoroughly absorbed Christian’s style. But<br />

the experience of jamming with his idol jarred him:<br />

“When I began improvising with Charlie Christian,”<br />

Kessel recalled, he had to ask himself, “What am I going<br />

to play?” Kessel realized he would have to find his<br />

own musical voice rather than merely mirror Christian’s.<br />

Experiences in a varied settings on the road (with<br />

the bands of Chico Marx, Artie Shaw and Charlie Barnet)<br />

and in the studio (with the legendary likes of Lester<br />

Young and Charlie Parker) went a long way toward earning<br />

Kessel his own unique identity, one which bridged<br />

the sounds of swing and bebop. In 1952, he joined bassist<br />

Ray Brown and pianist Oscar Peterson in an influential<br />

trio which spotlighted Kessel’s talents. But family<br />

concerns prompted Kessel to leave Peterson’s trio in<br />

1953. Before departing, he recommended Herb Ellis for<br />

the job.<br />

“We met 30 years ago at the Taft Hotel in New York<br />

City,” Ellis told Robert Yelin in 1974. “Barney had some<br />

trouble with his guitar, so he came to borrow mine. He<br />

was working with Artie Shaw then, and I was off from<br />

the Jimmy Dorsey band that night. From that first meeting<br />

we jammed, and we’ve been jamming ever since.”<br />

Beyond common musical passions, Ellis and Kessel<br />

shared similar beginnings in Southwestern small towns.<br />

For Ellis, it was Farmville, Texas, where he was born in<br />

1921. “My mother tells me I always played the blues,”<br />

Ellis recalls. His interest in jazz blossomed at North Texas<br />

State College, where Ellis majored in music and eagerly<br />

explored Charlie Christian’s recordings with Benny<br />

Goodman’s Sextet. Both Ellis and Kessel cite the same<br />

formative influences: Christian, tenor saxophonist Lester<br />

Young and alto saxophonist Charlie Parker.<br />

8

Kansas City was still a jazz Mecca when Ellis joined<br />

the Glen Gray’s Casa Loma Orchestra in the early 1940s.<br />

Praised in down beat and Metronome, Ellis then moved<br />

up to Jimmy Dorsey’s Orchestra. After World War II,<br />

piano, guitar and bass trios were all the rage and for<br />

awhile Ellis became a third of the Soft Winds. It was a<br />

calm before the storm of Oscar Peterson’s frenetic tempos<br />

in the trio which Ellis joined at Kessel's departure<br />

in 1953. “Herb Ellis,” Peterson wrote in Lp sleeve notes,<br />

“demonstrates...that he is not only a talented soloist,<br />

but that he has complete control of his instrument, along<br />

with a capacity for invention at all tempos...” Considering<br />

its source, that’s high praise indeed.<br />

Following five exhilarating years with Peterson and<br />

bassist Ray Brown, Ellis left to work as accompanist to<br />

Ella Fitzgerald for a year. There were occasional ventures<br />

as leader, such as the highly-regarded Verve album<br />

Nothing But the Blues, but Ellis spent much of the<br />

1960s and part of the 1970s in studio orchestras for a<br />

succession of television variety-talk shows, including<br />

the Merv Griffin Show. Ellis has characterized the studio<br />

musician’s life as “99% boredom, 1% absolute terror,”<br />

but admits he occasionally found inspiring material<br />

in that role.<br />

The outstanding feature of Ellis’ solos, writes jazz<br />

guitar historian Norman Mongan, is “an extraordinarily<br />

earthy quality...Ellis is unbeatable where swing and drive<br />

are concerned; his is a style of classic modern simplicity.”<br />

Ellis seemed to emphasize much the same point in<br />

discussing the empathy among Kessel, Byrd and himself<br />

with Robert Yelin: “We all have a mutual respect<br />

and great feeling for swing,” he said. “Without even talking<br />

about it among ourselves, swing is the basis for our<br />

wanting to play the guitar.”<br />

Charlie Byrd points to a slightly different impetus<br />

for taking up the instrument: “It was such a happy social<br />

occasion to play music at my house,” he recalled<br />

in a 1967 <strong>Guitar</strong> Player, “I guess I just wanted to be in<br />

on it.” The house was in Chuckatuck, Virginia, where<br />

Byrd was born in 1925. His father and uncle played fingerstyle<br />

guitar and his father ran a country store where<br />

9

“the black blues pickers came in on Saturday nights to<br />

play and drink a few beers,” Byrd recalled to Frets editor<br />

Jim Hatlo. He “learned by listening and absorbing.”<br />

But the radio brought him another musical world: “Fred<br />

Waring had a radio program that Les Paul was on during<br />

the late 1930s,” Byrd told Hatlo, and, of course, there<br />

were Benny Goodman’s groups. Theirs was the music<br />

Byrd aspired to play, even though he was happy in his<br />

teens to pick country and folk tunes on radio stations in<br />

Newport News and Suffolk. (At 14, Byrd acquired a<br />

Sears Silvertone electric guitar and amplifier, the first<br />

such contraption heard in Chuckatuck!)<br />

Like Kessel, Byrd got an early taste of the jazz life<br />

when, in his 14th summer, he played with a dance orchestra<br />

from William and Mary College at the resort town<br />

of Virginia Beach. The precocious Byrd enrolled in the<br />

Virginia Polytechnic Institute at age 16 and played in<br />

the school dance band. During World War II, Byrd played<br />

in the Special Forces band in Europe. He also got a<br />

chance to sit in with Django Reinhardt before shipping<br />

home. That meeting, Byrd asserts, “decided me on a<br />

career in jazz.”<br />

But he was sidetracked for a time by the lure of the<br />

classical guitar. Thanks in part to the G.I. Bill, Byrd studied<br />

with Sophocles Papas and, in 1954, made a pilgrimage<br />

to Siena, Italy to study with Segovia. The experience<br />

offered Byrd the humbling insight that “I wasn’t<br />

really going to be a significant classical guitar player,”<br />

he told Hatlo. “I realized that it might be a better idea<br />

for me to use all my life’s experience, in jazz and popular<br />

music as well, combining them with classical. So I<br />

started working out some jazz arrangements on classical<br />

guitar, and I thought, ‘Someone might be interested<br />

in recording these.”’ Savoy Records was interested, and<br />

in 1956 Byrd’s <strong>Jazz</strong> Recital album appeared.<br />

A 1961 State Department-sponsored ‘goodwill’ tour<br />

of Latin America brought Byrd into contact with the<br />

sounds of bossa nova. The following year his collaboration<br />

with tenor saxophonist Stan Getz, <strong>Jazz</strong> Samba, carried<br />

Brazil’s ‘new beat’ to the U.S. and became a surprise<br />

hit. (“Desifinado” made it to # 15 on the pop<br />

10

11<br />

Photo by Tom Copi

charts!) “I guess that got me typecast a little more than<br />

I would have liked,” Byrd admitted 20 years later, but it<br />

was a strong validation of his move to explore jazz on<br />

the classical guitar.<br />

Ironically, the ‘Great <strong>Guitar</strong>’ heard playing bossa<br />

nova on this collection isn’t Byrd but Kessel who shows<br />

his confidence in an idiom generally associated with fingerstyle<br />

guitarists and nylon-strung guitars. His medley<br />

of Luiz Bonfa’s “Manha de Carnaval” and “Samba de<br />

Orfeu” is taken from the evocative score for the 1960<br />

film, Black Orpheus. Accompanying Kessel on this 1969<br />

date in Denmark are Larry Ridley, bass, and Don<br />

Lamond, drums .<br />

A decade later, Kessel and Ellis teamed up on Iowa<br />

public television’s <strong>Jazz</strong> At The Maintenance Shop for a<br />

sassy sprint through George Gershwin’s “Oh! Lady Be<br />

Good,” a standard from the 1924 musical of the same<br />

name. The performance clearly reveals this duo’s roots<br />

in the Southwest, which gave the guitar world not only<br />

Charlie Christian but electric blues pioneer T–Bone<br />

Walker and Western Swing guitarist-arranger Eldon<br />

Shamblin of Bob Wills Texas Playboys. Kessel and Ellis<br />

seemingly return home here. Such performances inspired<br />

Norman Mongan to observe that Ellis’ “Southwestern<br />

twang...powerful attack and ‘stringy’ tonality<br />

make constant reference to his Texas origins.”<br />

Proving that great tunes often come from unlikely<br />

sources is the Bryson & Goldberg “Flintstones Theme”<br />

from the 1960s television cartoon series. Kessel and<br />

Ellis take a fiercely swinging romp through Bedrock accompanied<br />

by Joe Byrd, bass, and Wayne Phillips,<br />

drums. This performance is from a ‘duo’ spotlight of<br />

The Great <strong>Guitar</strong>s captured in Cork, Ireland in 1980.<br />

“What’s great about these concerts,” Ellis, the longtime<br />

television studio ace once said, “is that we’re playing<br />

duets for the public and getting paid for it.”<br />

Trios, too. Our collection’s finale features the full<br />

fleet of Great <strong>Guitar</strong>s in a medley tribute to three earlier<br />

extraordinary guitarists. It opens with “Nuages,” the<br />

most popular composition of Django Reinhardt (1910-<br />

1953), who recorded it at least 8 times. (“Nuages” made<br />

12

oth the French and British ‘hit parades.’) In a 1976<br />

<strong>Guitar</strong> Player tribute to Reinhardt, Kessel wrote: “He<br />

symbolizes the Gypsy spirit, the thing in everyone that<br />

wants to be free—to be an adult but not lose the childlike<br />

quality.”<br />

“Goin’ Out of My Head” was a 1964 hit for Little<br />

Anthony & the Imperials which became a 1966 Grammywinning<br />

vehicle for Wes Montgomery (1925-1968). It<br />

represents a phase of Montgomery’s career which<br />

brought him popular acclaim along with the disdain of<br />

some jazz fans who felt he had sold out. In a 1972 <strong>Guitar</strong><br />

Player discussion (‘Where Are the <strong>Jazz</strong> <strong>Guitar</strong> Lps?’),<br />

Kessel remarked: “I remember talking with Wes Montgomery<br />

when he was playing in a packed club. He wasn’t<br />

bitter, just realistic. He said, ‘See those people out there?<br />

They didn’t come to hear me, they came to see me play<br />

one, two or three of my hit records, because when I decide<br />

to do a tune of mine or Coltrane’s ‘Giant Steps’<br />

instead of ‘Goin’ Out My Head’ they get bored and start<br />

talking.’” Success for a jazz musician can be a mixed<br />

blessing.<br />

The medley closes with the Benny Goodman-Lionel<br />

Hampton composition “Flying Home,” long the theme<br />

of the Lionel Hampton Orchestra and, in its early days,<br />

a showcase for Charlie Christian (1916-1942), without<br />

whom most of the music on this video is unthinkable.<br />

The trio of Byrd (on an Ovation acoustic–electric),<br />

Kessel and Ellis (both playing Gibsons) gave this exhilarating<br />

1980 performance in Cork, Ireland in the company<br />

of bassist Joe Byrd and drummer Wayne Phillips.<br />

In a 1974 <strong>Guitar</strong> Player interview, Ellis gave away<br />

part of The Great <strong>Guitar</strong>s’ game. “What’s particularly<br />

good about a trio,” Ellis explained to Robert Yelin, “is<br />

that the soloist can concentrate completely on his<br />

chorus...the other two guys will come in to take over<br />

the ensemble part while the soloist is thinking only about<br />

his solo.” Byrd summed up The Great <strong>Guitar</strong>s experience<br />

this way: “We have a great time,” he said, “and we<br />

enjoy each other’s company...We just love to go out there<br />

and swing for them. We couldn’t swing the way we do if<br />

these concerts didn’t make us happy.”<br />

13

Photo by Tom Copi<br />

TAL FARLOW<br />

The stunning<br />

velocity and facility<br />

with which Tal Farlow,<br />

pianist Tommy Flanagan<br />

and bassist Red<br />

Mitchell blaze through<br />

“Fascinating Rhythm”<br />

(a Gershwin tune from<br />

the 1924 musical, Oh!<br />

Lady Be Good) in<br />

Lorenzo De<strong>Stefan</strong>o’s<br />

1981 documentary,<br />

Talmadge Farlow, is a<br />

jaw-dropping study in<br />

abandon earned by<br />

years of woodshedding.<br />

Farlow has only<br />

reluctantly left his<br />

woodshed in recent<br />

decades, and the rarity<br />

of his public appearances<br />

has only enhanced his deserved reputation<br />

as a jazz genius.<br />

Jim Hall has called Farlow “the most complete musician<br />

I know on guitar,” and he’s not alone in that opinion.<br />

Farlow turned up the heat several notches on bopera<br />

guitarists by his innovative work in the Red Norvo<br />

Trio in the 1950s. “Farlow took the message of hard<br />

bop and translated it for the guitar,” writes Norman<br />

Mongan in The History of the <strong>Guitar</strong> in <strong>Jazz</strong>. “Always<br />

inspired, he let ideas flow from under his fingers and<br />

creates a sound more akin to that of a wind instrument<br />

than a guitar.” Blowing at tempos few guitarists dare<br />

match, it wasn’t only for his large hands that Farlow<br />

earned the nickname the Octopus: he was seemingly<br />

everywhere on the fingerboard at once.<br />

Talmadge Holt Farlow was born in Greensboro,<br />

North Carolina in 1921. It’s often been said that he didn’t<br />

start playing till his early twenties, but that isn’t exactly<br />

14

true. “I could already play the guitar a little bit,” Farlow<br />

told down beat reporter Lee Jeske, “but the guitar was,<br />

in most cases, part of a hillbilly band—you know, with<br />

three chords.” The guitarist who made him think, “Now<br />

I’ve got an instrument here that can conceivably move<br />

out front” was, naturally, Charlie Christian. “Christian<br />

was the one who got me moving,” Farlow told Burt Korall<br />

(down beat February 22, 1979). “I bought all the<br />

Goodman–Christian recordings and memorized Charlie’s<br />

choruses, note-for-note, playing them on a secondhand<br />

fourteen dollar guitar and twenty dollar amplifier.” Working<br />

as a sign painter in Greensboro, Farlow had few opportunities<br />

to play with other jazz musicians. However,<br />

radio brought him the sounds not only of Charlie Christian<br />

but of such innovators as Lester Young and pianist<br />

Art Tatum. Self-taught, Farlow had an innate sense of<br />

the guitar’s potential by the time he found himself working<br />

piano-bass guitar trios in Philadelphia during World<br />

War II.<br />

Pianist/singer Dardanelle Breckenridge gave Farlow<br />

his first noteworthy job in 1947. It took him to New York<br />

City, where he heard Charlie Parker “giving off sparks,<br />

influencing every young player in sight,” Farlow told<br />

Korall. “At the beginning, I had some difficulty getting<br />

into what Bird and Diz and Miles and those fellows were<br />

doing...I found the bop phrases didn’t fall easily on the<br />

guitar. But I kept listening and working out my problems<br />

until I felt comfortable with the modern idiom.” He<br />

worked so effectively in that idiom that vibes wizard Red<br />

Norvo hired Farlow in 1949. His work in Norvo’s Trio<br />

with bassist Charles Mingus is the stuff of legend. “I was<br />

no faster than the next guy until I went with Red,” Farlow<br />

told Korall. “I had to work like crazy just to keep up<br />

with Red and Mingus—they forced me into the woodshed.”<br />

After nearly five years with Norvo’s Trio, Farlow departed<br />

in 1953 for a stint with Artie Shaw’s last Gramercy<br />

Five. Farlow rejoined Norvo for awhile in a quintet, then<br />

fronted his own trio with pianist Eddie Costa. In 1958<br />

Farlow left New York City and its jazz scene for a life of<br />

anonymity in Sea Bright on the Jersey Shore. “I got fed<br />

15

up with the back stage parts of the jazz life,” Farlow explained<br />

to Korall. “It seemed that I became increasingly<br />

involved with stuff that had nothing to do with music.”<br />

A country boy at heart, sign painting and occasional<br />

local gigs in Sea Bright suited Farlow. “I don’t have to<br />

be out there,” Farlow said, “dealing with situations I find<br />

difficult to handle. I don’t need expensive things or a<br />

hectic life. So I stay in Sea Bright.”<br />

Starting in 1967, Farlow began making occasional<br />

forays “out there” – a reunion with Norvo on a 1969<br />

Newport All-Stars tour and a Prestige album the same<br />

year, The Return of Tal Farlow, reminded the jazz world<br />

he was still a player of ferocious energy. Recordings for<br />

the Concord label in the 1970s brought Farlow further<br />

acclaim, and in 1981 he ventured out with Norvo and in<br />

the company of Herb Ellis and Barney Kessel. The performance<br />

from that same year in this video affirms that<br />

Farlow at 60 was still in peak form.<br />

For all his harmonic invention, Farlow never learned<br />

to read music, and felt self-conscious about that. His<br />

unease may have contributed to his retirement, particularly<br />

from recording. Asked in a 1969 <strong>Guitar</strong> Player for<br />

advice to aspiring jazz guitarists, Farlow said: “You have<br />

to really play all the time so that you are able to execute<br />

any ideas that come into your head. To be a jazz<br />

player, that’s important. After you learn the scales, to<br />

be a better jazz player, you should play more jazz and<br />

lots of it.”<br />

PAT MARTINO<br />

His father, once a pupil of Eddie Lang, told him at<br />

birth: “With these hands you are really going to learn to<br />

play guitar.” Instead of bullying his son into practice, he<br />

lured him to the guitar by forbidding him to touch the<br />

one hidden under his bed. “I was... a prodigy,” Martino<br />

told <strong>Guitar</strong> Player’s Vic Trigger. “When I was 11 years<br />

old I had about the same chops I have today...” By the<br />

time he was 16, he was accompanying such R&B stars<br />

as Lloyd Price and Chubby Checker. Six years later<br />

Martino’s debut album as a leader, El Hombre, made<br />

him a presence to reckon with in the jazz guitar world.<br />

16

His punchy 1987 performance here of his composition<br />

“Do You Have A Name?” in the company of bassist<br />

Harvie Swartz and drummer Joey Baron plainly shows<br />

why. “Mr. Martino,” wrote New York Times reviewer Peter<br />

Watrous, “was among the few important jazz guitarists<br />

to arrive in the 1960s, somebody who understood<br />

the place of a blues sensibility in jazz and who could<br />

improvise with the fluency and drive of a horn player...”<br />

Born in Philadelphia in 1944, Pat Azzara took the name<br />

his father used as a singer, Martino, and paid his dues<br />

not only accompanying pop singers such as Frankie<br />

Avalon but jazzmen such as tenor saxophonist Willis<br />

Jackson. For a child prodigy, it was a humbling dose of<br />

reality: “I was, for the first time in my life, reduced to<br />

being a subordinate,” Martino told Trigger. “I thought<br />

that once you had reached these incredible chops you<br />

were revered, literally revered...It required so much redefinition<br />

from me to survive that it brought me<br />

strength.”<br />

Martino’s 1967 stint with the John Handy Quintet<br />

thrust him into the spotlight; by the end of the 1960s he<br />

was fronting his own groups. Initially indebted to the<br />

influence of Johnny Smith and Wes Montgomery, in the<br />

1970s Martino’s music explored not only such familiar<br />

jazz touchstones as the blues and bossa nova but also<br />

Indian music and modern compositional ideas inspired<br />

by Karlheinz Stockhausen and Elliott Carter. “I like to<br />

walk up to the guitar and throw myself into the middle<br />

of a creative experience,” said Martino, who did exactly<br />

that in the performance we see from Baltimore’s ‘Ethel’s<br />

Place.’<br />

In 1976, Martino began suffering memory loss and<br />

headaches. A nightmarish four years of locked wards<br />

and shock treatments followed. Finally, it was discovered<br />

that Martino had a brain aneurysm; an operation<br />

to restore blood flow to his brain left him without his<br />

memory. Martino regained his brilliant skills by studying<br />

his old recordings.<br />

In a January 25, 1995 New York Times review of a<br />

Bottom Line appearance, Martino’s first New York City<br />

outing in at least a decade, Peter Watrous wrote: “Mr.<br />

17

Martino proved himself to be as charismatic an improviser<br />

as ever.” In the Times only a couple of weeks later,<br />

Matt Resnicoff praised Martino’s “torrential, groovedriven<br />

melodies that seemed to stab at the listener from<br />

several directions at once.” Happily, Pat Martino’s back<br />

doing what he does best. “<strong>Jazz</strong>,” Martino once reflected,<br />

“is a way of life, not an idiom of music. <strong>Jazz</strong> is spontaneous<br />

improvisation. If you ever walk out of your house<br />

with nowhere to go, just walking for the pleasure of it,<br />

you’ll find that you improvise. Everyone in life improvises;<br />

jazz is just a relative degree of improvisation.”<br />

Photo by Tom Copi<br />

18

PERFORMANCES & PERSONNEL<br />

1. JIM HALL(G),<br />

STEVE SWALLOW(B) and PETE La ROCA(D)<br />

“<strong>Jazz</strong> 625” September 26, 1964 London, England<br />

Song: I’m Getting Sentimental Over You<br />

2. BARNEY KESSEL(G),<br />

LARRY RIDLEY(B) and DON LAMOND (D)<br />

Newport All-Stars, Denmark 1969<br />

Song: Medley Manha, De Carnaval<br />

and Samba De Orfeu<br />

3. TAL FARLOW (G),<br />

TOMMY FLANAGAN (P) and RED MITCHELL (B)<br />

New York City 1981<br />

Song: Fascinating t Rhythm<br />

4. BARNEY KESSEL (G) and HERB ELLIS (G)<br />

“<strong>Jazz</strong> At The Maintenance Shop”, Ames, Iowa 1979<br />

Song: Oh Lady Be Good<br />

5. JIM HALL (G) and MICHEL PETRUCCIANI (P)<br />

Denmark 1986<br />

Song: My Funny Valentine<br />

6. PAT MARTINO (G),<br />

HARVIE SWARTZ (B) and JOEY BARON (D)<br />

“Ethel's Place” Baltimore, Maryland 1987<br />

Song: Do You Have A Name<br />

7. BARNEY KESSEL (G), HERB ELLIS (G),<br />

JOE BYRD (B) and WAYNE PHILLIPS (D)<br />

The Great <strong>Guitar</strong>s In Cork, Ireland 1980<br />

Song: Flintstone Theme<br />

8. JIM HALL WITH THE ART FARMER QUARTET ON<br />

“<strong>Jazz</strong> 625” September 26, 1964 London, England<br />

JIM HALL (G), ART FARMER (Fluegelhorn),<br />

STEVE SWALLOW(B) and PETE La ROCA(D)<br />

Song: Valse Hot<br />

9. BARNEY KESSEL (G), HERB ELLIS (G), CHARLIE<br />

BYRD (G), JOE BYRD (B) and WAYNE PHILLIPS (D).<br />

The Great <strong>Guitar</strong>s In Cork, Ireland 1980.<br />

Songs: Nuages, Goin' Out <strong>Of</strong> My Head and Flying Home<br />

19

Vestapol 13043<br />

Barney Kessel & Herb Ellis<br />

The guitar's odyssey in jazz is presented afresh in Vestapol's third<br />

compilation of prime performances from six of the idiom's movers<br />

and shakers. These men are among the most exemplary band members<br />

to choose the guitar as their means of expression. The initial<br />

inspiration for most of them was Charlie Christian, who blazed trails<br />

jazz guitarists still tred a half century later. Christian swung in the<br />

direction of bop, and his disciples (foremost among whom are seen<br />

here) boldly carried the guitar into that next phase of jazz. Aside from<br />

their fervor for the potential of the guitar in the evolution of jazz,<br />

many of these artists have similar backgrounds: Southern or Southwestern,<br />

and of roughly the same generation. But their individuality<br />

is abundantly clear in performances ranging from meditative ballads<br />

to speed-of-sound boppers. Underlying it all is an exhilarating sense<br />

of triumph over that apparent oxymoron, jazz guitar. Having proven<br />

that the guitar is indeed a first rate medium for jazz expression, these<br />

artists confidently address other contradictions, ones involving evolution<br />

within a well-grounded tradition. They’re serious about their<br />

business, but you can see them having fun with it, too.<br />

1. JIM HALL I’m Getting Sentimental Over You 2. BARNEY<br />

KESSEL Medley: Manha De Carnaval & Samba De Orfeu<br />

3. TAL FARLOW Fascinating Rhythm 4. BARNEY KESSEL & HERB<br />

ELLIS Oh! Lady Be Good 5. JIM HALL My Funny Valentine<br />

6. PAT MARTINO Do You Have A Name 7. BARNEY KESSEL &<br />

HERB ELLIS Flintstones Theme 8. JIM HALL Valse Hot<br />

9. BARNEY KESSEL, HERB ELLIS & CHARLIE BYRD Medley:<br />

Nuages, Goin’ Out <strong>Of</strong> My Head & Flying Home<br />

Running Time: 63 minutes • B/W and Color<br />

Front & Back Photos by Tom Copi<br />

Nationally distributed by Rounder Records,<br />

One Camp Street, Cambridge, MA 02140<br />

Representation to Music Stores by<br />

Mel Bay Publications<br />

® 2001 Vestapol Productions<br />

A division of<br />

<strong>Stefan</strong> <strong>Grossman's</strong> <strong>Guitar</strong> <strong>Workshop</strong> Inc.<br />

ISBN: 1-57940-916-4<br />

0 11671 30439 7