Father Severino Giner-Guerri, Sch.P. - The Piarist Fathers

Father Severino Giner-Guerri, Sch.P. - The Piarist Fathers

Father Severino Giner-Guerri, Sch.P. - The Piarist Fathers

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

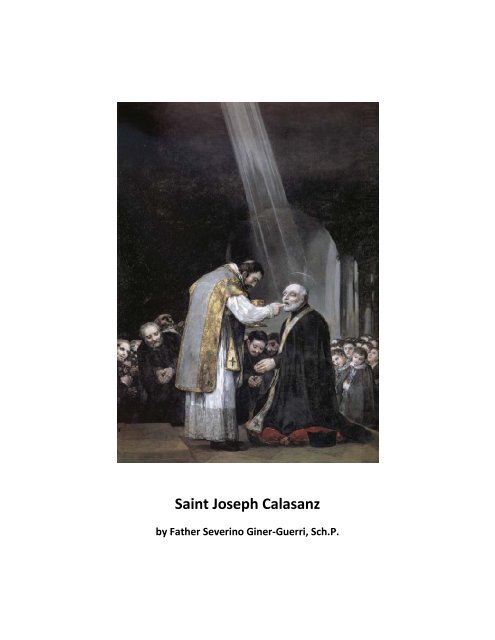

Saint Joseph Calasanz<br />

by <strong>Father</strong> <strong>Severino</strong> <strong>Giner</strong>-<strong>Guerri</strong>, <strong>Sch</strong>.P.

Translation of San Jose de Calasanz by <strong>Father</strong> <strong>Severino</strong> <strong>Giner</strong>-<br />

<strong>Guerri</strong>, <strong>Sch</strong>.P. (Province of Valencia).<br />

BAC Popular – Second Edition – Madrid 1993.<br />

<br />

Edited by SAC (Bibliotheca de Autores Cristianos).<br />

This book was translated into English from the original Spanish by<br />

<strong>Father</strong> Salvador Cudinach, <strong>Sch</strong>.P. (Vice-Province of California).<br />

<br />

<strong>The</strong> original English translation was published by the<br />

Argentinian Province of the <strong>Piarist</strong> <strong>Father</strong>s in India, 1993.<br />

<strong>The</strong> English translation was edited by Kevin J. Owens and <strong>Father</strong><br />

John G. Callan, <strong>Sch</strong>.P. <strong>The</strong> edited translation was further edited by<br />

<strong>Father</strong> Jose A. Basols, <strong>Sch</strong>.P., <strong>Father</strong> Jesus Maria Lecea, <strong>Sch</strong>.P.<br />

and <strong>Father</strong> Emilio Sotomayor, <strong>Sch</strong>.P. (Province of the United<br />

States and Puerto Rico).<br />

<br />

<strong>The</strong> edited English translation was published by the Province<br />

of the United States and Puerto Rico, 2012.

INDEX<br />

Index<br />

Introduction<br />

Abbreviations<br />

Chapter 1 A HAPPY CHILDHOOD 1<br />

Peralta de la Sal 1<br />

<strong>The</strong> Kingdom of Aragon 3<br />

<strong>The</strong> Calasanz-Gaston Family 5<br />

Birth of Joseph 8<br />

Home Education 10<br />

Estadilla 11<br />

Chapter 2 UNIVERSITY STUDIES AND ORDINATION 14<br />

Traditional Version and Documented Data 14<br />

University of Lerida – First Period 15<br />

Valencia and Alcala de Henares 19<br />

Final Decision to Become a Priest 21<br />

Return to Lerida – Holy Orders 22<br />

Chapter 3 FIRST YEARS OF PRIESTHOOD 25<br />

Misguided Biographers and Calasanz’ Disorientation 25<br />

<strong>The</strong> Episcopal Palace of Barbastro 27

Aide to the Bishop of Lerida in Monzon 29<br />

Apostolic Visit to Montserrat 30<br />

Death of His <strong>Father</strong> – Peralta de la Sal 33<br />

Chapter 4 IN THE LAND OF SEU D’URGELL 34<br />

Historical Environment of Seu d’Urgell 34<br />

Calasanz and the Cathedral Chapter 37<br />

Ecclesiastical Official in Tremp 39<br />

Diocesan Visitor and Reformer 41<br />

Seeds of a Future Vocation 45<br />

To Rome 47<br />

Chapter 5 ROME: YEARS OF RESTLESSNESS 50<br />

Return to Spain? 50<br />

Obsession for a Canonry 52<br />

Change of Course – Religious and Social Activities 57<br />

Mystical Ways? 61<br />

Chapter 6 GENESIS OF THE PIOUS SCHOOLS 64<br />

<strong>The</strong> Great New Idea 64<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Sch</strong>ool of Saint Dorothy in the Trans Tiber Section<br />

of Rome<br />

65<br />

<strong>The</strong> “Pious <strong>Sch</strong>ools” 69<br />

Benefactors and Disasters 71

First Collaborators 74<br />

Decisive Move – Saint Pantaleo 77<br />

Chapter 7<br />

FROM SECULAR CONGREGATION TO RELIGIOUS<br />

ORDER<br />

79<br />

Union with the Congregation from Lucca 79<br />

Between Illusions and Disappointments 82<br />

Courageous Attempt to Reform 87<br />

Acceptance of His Own Destiny – Founder 90<br />

<strong>The</strong> Pauline Congregation of the Pious <strong>Sch</strong>ools 93<br />

First Wanderings of the Founder 96<br />

<strong>The</strong> Order of the Pious <strong>Sch</strong>ools 99<br />

Chapter 8 EXPANSION 102<br />

Liguria 102<br />

Naples 105<br />

Central Italy 109<br />

Sicily and Sardinia 111<br />

Beyond the Alps 114<br />

Two Failures: Venice and Spain 118<br />

Chapter 9 PIETY AND LETTERS 121<br />

A New Order for a New Ministry 121<br />

Formation of Religious Teachers 124

Intellectual Formation of Children (Letters) 128<br />

Moral and Christian Formation of Children (Piety) 132<br />

Chapter 10 THE APOSTOLIC VISIT OF 1625 136<br />

Before and After 136<br />

Three Complementary Documents 139<br />

Minutes and Decrees of the Visit 142<br />

Calasanz’ Answer 144<br />

Chapter 11 GENERAL CHAPTERS 147<br />

General Chapter of 1627 147<br />

General Chapter of 1631 148<br />

Disappointments and Informers 151<br />

General Chapter of 1637 155<br />

General Chapter of 1641 157<br />

Chapter 12 BEGINNING OF THE GREAT TRIBULATION 159<br />

<strong>The</strong> Brother Clerics 159<br />

Turbulence by the Brother Clerics 160<br />

A New Player: <strong>Father</strong> Mario Sozzi 164<br />

<strong>Father</strong> Mario: Provincial of Tuscany 168<br />

Via Dolorosa 172<br />

Chapter 13 THE GREAT TRIBULATION 176<br />

Suspension of the Superior General 176

<strong>The</strong> Apostolic Visit 181<br />

Government Under <strong>Father</strong>s Sozzi and Cherubini 184<br />

<strong>The</strong> Commission of Cardinals: <strong>The</strong> First Two Sessions 188<br />

Third Session: Fleeting Joys and Triumphs 192<br />

<strong>The</strong> Last Two Sessions: Destruction 195<br />

Chapter 14 DEATH AND GLORIFICATION 200<br />

Heroic Hope 200<br />

Death of a Just Man 204<br />

First Glorification: Funerals 208<br />

Second Glorification: Restoration of the Order 211<br />

Third Glorification: Beatification and Canonization 214<br />

Notes 218<br />

<strong>The</strong> Author 229

INTRODUCTION<br />

Two works stand out because of their literary criticism and<br />

size among the many biographies of Saint Joseph Calasanz,<br />

which were published during the last three centuries. <strong>The</strong> first,<br />

Life of Blessed Joseph Calasanz of the Mother of God, the<br />

Founder of the Pious <strong>Sch</strong>ools, was published by <strong>Father</strong> Vincent<br />

Talenti after the saint's beatification in 1748. <strong>The</strong> second work<br />

was written by <strong>Father</strong> Calasanz Bau. This was published in<br />

Madrid in 1949 to celebrate the third and second centennials of<br />

the death and beatification of the Founder of the Pious <strong>Sch</strong>ools.<br />

<strong>The</strong> book was titled Critical Biography of Saint Joseph Calasanz.<br />

In its introduction, the author expressed the desire to present a<br />

totally "new" biography using documented sources. <strong>Father</strong> Bau,<br />

however, was not satisfied with his initial effort and wrote the<br />

biography again. He substantially cut down his previous large<br />

work and subjected it to formal corrections using a precise<br />

methodology. This new version was titled Revised Edition of the<br />

Life of Saint Joseph Calasanz. It was published in 1963. <strong>The</strong>se<br />

two complimentary works by <strong>Father</strong> Bau are the last serious<br />

investigative biographies of the Founder.<br />

<strong>Father</strong> Bau’s critical biography awakened among the<br />

<strong>Piarist</strong>s a desire to do research on their Founder, studying his<br />

history as well as his ideology and personality. Several doctoral<br />

theses on the theology, spirituality, history, canon law and<br />

pedagogy of Calasanz were written. See the works by A. Sapa,<br />

C. Bau, A. Garcia-Duran, C. Vila, S. <strong>Giner</strong> and R. Martin.<br />

<strong>The</strong> biography by <strong>Father</strong> Calasanz Bau was the beginning<br />

of some very important research on the following documents: 1)<br />

Letters of Saint Joseph Calasanz, 1950-1956; 2) Letters to Saint<br />

Joseph Calasanz from Central Europe, 1969; 3) Letters to Saint<br />

Joseph Calasanz from Spain and Italy, 1972; 4) Mutual<br />

correspondence among writers to Saint Joseph Calasanz, 1977-<br />

1982. All of these works make up nineteen volumes, totalling<br />

eleven thousand pages.<br />

In addition to these, we have many scientific articles on the<br />

life, ideology and Calasanzian spirituality published in the<br />

following magazines of the Order: Revista Calasancia, Analecta

Calasanctiana, Ephemerides Calasanctianae, Archivum<br />

<strong>Sch</strong>olarum Piarum, Rassegna di storia e bibliografia Scolopica,<br />

Ricerche (Bolletino degli Scolopi Italiani). <strong>The</strong> articles were<br />

written by <strong>Father</strong>s L. Picanyol, G. Santha, J. Poch, C. Vila, C.<br />

Bau, M. A. Asiain, D. Cueva, G. Ausenda, O. Tosti, J. M. Lecea<br />

and S. <strong>Giner</strong>. Two writers, however, stand out among these<br />

authors: <strong>Father</strong> J. Poch who wrote on the so-called "Spanish<br />

Period" of the Founder (1557-1592), and <strong>Father</strong> G. Santha who<br />

wrote on the "Italian Period" (1592-1648). <strong>The</strong>y contributed<br />

tremendously to the clarification of many points in the life and<br />

work of Calasanz.<br />

A later and very valuable contribution was written by <strong>Father</strong><br />

C. Vila in his work titled Positio of <strong>Father</strong> Casani. Although<br />

<strong>Father</strong> Casani is the central figure in the document, the heroism<br />

of Calasanz is evident. <strong>Father</strong> Casani was Calasanz's assistant,<br />

companion and collaborator for over thirty-three years.<br />

<strong>The</strong> present work, part of a collection called BAC Popular,<br />

does not pretend to be a work of direct scientific investigation<br />

with all of the prerequisites of a critical methodology. <strong>The</strong> author,<br />

however, has kept in mind the works and writings that have<br />

been published, correcting or detailing the biographical<br />

viewpoint of Saint Joseph Calasanz as presented by <strong>Father</strong> Bau.<br />

Given the large amount of textual documentation that we present,<br />

we thought it convenient to back up our quotations with a minimum<br />

number of bibliographical references. <strong>The</strong> majority of these<br />

references are translations from the original Latin or Italian, with a<br />

few from Catalan. We offer you then a work, which with its modest<br />

limitations, attempts to be a new biography including the results<br />

from the most recent research.<br />

Madrid, ICCE, May 1985.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Author

PRELIMINARY NOTE TO THE SECOND EDITION<br />

I published the Life of Saint Joseph Calasanz, Teacher and<br />

Founder in BAC Maior in 1992. It was a new critical biography. I<br />

totally revised the original book by using criteria from the most<br />

demanding historical methodologies. In this way, I arrived at<br />

conclusions, clarifications and different hypotheses held up until<br />

today by the various biographers of Calasanz. In preparing the<br />

second edition of this popular biography, I thought that it would be<br />

appropriate to revise and adapt it to any recent critical biographers,<br />

except for some debatable ideas that do not make a difference<br />

anyway.<br />

Rome, April 1993.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Author

ABBREVIATIONS<br />

Anal. Cal.<br />

Archivum<br />

Calasanzian Documents. Madrid 1959-1976. Salamanca<br />

1977-present.<br />

Archives of the Pious <strong>Sch</strong>ools. Rome 1936-present.<br />

BAD, BC Critical Biography of Saint Joseph Calasanz. Madrid<br />

1949.<br />

BAD,RV Revised Life of Saint Joseph Calasanz in Anal. Cal., 10,<br />

1963.<br />

C Letter in EGC<br />

Const. Constitutions of the Pious <strong>Sch</strong>ool by St. Joseph Calasanz.<br />

1622.<br />

EC Letters of the Contemporaries of St. Joseph Calasanz. G.<br />

Santha, C. Vila. Rome 1977-1982.<br />

EEC Letters to St. Joseph Calasanz from Central Europe. G.<br />

Santha. Rome 1969.<br />

EGC Letters of St. Joseph Calasanz. L. PicanyoI. Rome 1950-<br />

1956. Nine Volumes.<br />

EHI<br />

Eph. Cal.<br />

Letters to St. Joseph Calasanz from Spain and Italy.<br />

Rome 1932.<br />

Ephemerides Calasanctianae (Magazine). Rome 1932-present.<br />

"Positio" Position Paper on the Virtues of Peter Casani, Rome 1982.<br />

Rev. Cal. Revista Calasancia. Madrid 1888-1969.<br />

Santha<br />

(BAC)<br />

SANTHA<br />

Ensayos<br />

G. Santha, San Jose de Calasanz, Obra Pedagogica. (BAC)<br />

Madrid 1984.<br />

G. Santha, Critical Essays. Salamanca 1976.

Chapter 1<br />

A HAPPY CHILDHOOD<br />

Peralta de la Sal<br />

On August 25, 1646, exactly two years before his death,<br />

Calasanz wrote to the Vice-Queen of Sardinia, Lady Catherine<br />

of Moncada and Alagon, while consoling her in her tribulations:<br />

"In the meanwhile, I shall always pray to the Lord to keep you<br />

and your household for many years to come, especially your<br />

two sons. This is what, I, your vassal, wish while paying you his<br />

respects." (1)<br />

Calasanz called himself a vassal and so he was. He was a<br />

vassal from the house of Moncada, because he was born in the<br />

village of Peralta de la Sal. Peralta was one of the many fiefs of<br />

the Count of Moncada. <strong>The</strong> addition of Peralta was recent.<br />

Lady Margaret of Castro and Alagon was the heiress of the<br />

baronies of Castro and Peralta de la Sal. In 1610, she married<br />

Lord Francisco of Moncada, the third Marquis of Aytona and the<br />

Count of Osuna. Through their marriage, the barony of Peralta<br />

de la Sal became one of the many estates owned by the house<br />

of Moncada, who were also the Marquesses of Aytona. All of<br />

these titles and possessions were in the hands of the brother of<br />

the Vice-Queen of Sardinia, Lord Guillen Raymond of Moncada<br />

and Alagon. <strong>The</strong> Vice-Queen reminded Calasanz in one of her<br />

letters: "My brother, the Marquis of Aytona, is Lord of the house<br />

of Castro, because it belonged to my mother, the daughter of<br />

the Baroness of Laguna, whom your Reverence might have<br />

known." (2)<br />

<strong>The</strong> Lords of the barony of Peralta de la Sal go back to the<br />

thirteenth century and reappear in the extreme western side of the<br />

county of Urgell, which were among the last lands conquered from<br />

the Moors by the Counts of Urgell.<br />

<strong>The</strong> conquering counts settled the region with the people,<br />

whom they defeated. <strong>The</strong>y spoke Catalan and were familiar with<br />

Catalonian customs. <strong>The</strong>se people and their customs have<br />

1

emained there until today. Of course, there have been<br />

modifications and changes due to the fact of being in the frontier<br />

and later being incorporated into the Kingdom of Aragon. <strong>The</strong><br />

beginnings of the conquest of Urgell contributed to the incardination<br />

of Peralta and the villages of the barony into the county of Urgell.<br />

<strong>The</strong> barony of Castro, which was created by James I, the<br />

Conqueror, sprung up next to the barony of Peralta. James gave it<br />

to his illegitimate son, Fernan Sanchez. That is why the Baron of<br />

Castro would use later the title "royal." When Joseph Calasanz was<br />

born, Lord Berenguer Arnau de Cervello, the Baron of Laguna, and<br />

his wife Lady Eleanor de Boixadors, were the Barons of Castro and<br />

Peralta. Little Joseph heard a lot about them because these<br />

aristocrats were the lords of the village. Joseph felt and heard their<br />

presence in a special way because his father, Peter Calasanz, was<br />

the mayor of Peralta from 1559 until 1572. We do not know<br />

whether he was mayor for all of those years without interruption.<br />

<strong>The</strong> mayor was the direct representative of the baron and<br />

procurator of his patrimony and rights.<br />

<strong>The</strong> barony of Peralta included the villages of Gavasa,<br />

Pellegrino, Rocafort, Zurita, Cuatrocorz, Alcana, Momagastre and<br />

La Cuba. Peralta de la Sal was the capital of the barony, and its<br />

mayor was usually the mayor of all the villages in the barony. <strong>The</strong><br />

capital of the barony of Castro was Estadilla, where the lords lived.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se capitals were very small. Peralta, in the middle of the<br />

sixteenth century, had 315 inhabitants and Estadilla had 430.<br />

<strong>The</strong> village of Peralta de la Sal, located about 1,300 feet<br />

above sea level, is situated in a small river valley at the junction of<br />

the ravine de Gavasa with the river Sosa, which comes down from<br />

Calasanz and whose waters flow into the Cinca. <strong>The</strong> land<br />

surrounding Peralta is dry and produces the typical Mediterranean<br />

products: wheat, wine and olive oil. At the edge of the water, there<br />

is a considerable zone for irrigation. In the higher and hilly<br />

elevations there is holly. Holly was so abundant in days gone by<br />

that in 1798 an historian, Ignatius Asso, described the village as<br />

being surrounded by a "vast extension of holly." About three<br />

thousand feet east of the village in the ravines called Manantial,<br />

Collenera and Poza Grande, there are three water fountains. <strong>The</strong><br />

2

salty water from these fountains changed the whole area into an<br />

enormous region made up of salterns. <strong>The</strong>se gave Peralta not only<br />

its nickname "de la Sal" but also its livelihood for centuries. <strong>The</strong> salt<br />

was exported to Catalonia and France.<br />

Calasanz was a happy child in this village. He knew it inside<br />

out. He ran around the village and outside the village. One of the<br />

most famous and well-remembered anecdotes was the one that<br />

took place outside the village among the olive groves.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Kingdom of Aragon<br />

Saint Joseph Calasanz spoke and wrote Catalan very well.<br />

A dialect of Catalan is still spoken in Peralta today. This dialect is a<br />

result of the influence of an Aragonese-Spanish spoken in the<br />

outlying villages of the Catalan county of Urgell. During his studies<br />

at the University of Lerida and while performing his priestly ministry<br />

in his diocese of Urgell, Calasanz had a chance to perfect his<br />

maternal language, speaking and writing Catalan very well. As a<br />

native of Peralta de la Sal and as a priest, Calasanz belonged to<br />

the Catalan Diocese of Urgell. However, neither the diocese nor<br />

the language defines the nationality of the individual.<br />

<strong>The</strong> baronies of Castro and Peralta lie between two rivers:<br />

the Cinca and the Noguera Ribagorzana. Legal arguments about<br />

the boundaries between the Catalonian counties and the Kingdom<br />

of Aragon moved King James I to fix a dividing line in the Cinca in<br />

the middle of the thirteenth century. However, James II, his<br />

nephew, moved the boundary line from the Cinca to the Noguera<br />

Ribagorzana in 1300. His decision was not without the logical<br />

protests from the Catalonian courts. In spite of everything, the<br />

boundary remains unchanged even to this day. <strong>The</strong>refore, since<br />

1300 the baronies of Castro and Peralta were included in the<br />

Kingdom of Aragon along with the territory between the Cinca and<br />

the Noguera Ribagorzana. Nevertheless, in the first half of the<br />

seventeenth century, some maps, which were published in<br />

Flanders, showed the boundary of Catalonia in the Cinca. <strong>The</strong>se<br />

maps caused a lot of confusion.<br />

<strong>The</strong> baronies of Castro and Peralta like all the many<br />

3

aronies, counties, duchies and marquisettes strewn throughout<br />

Spain, were contained within the limits of the kingdoms or historic<br />

principalities. Accordingly, one cannot consider the baronies of<br />

Castro and Peralta autonomous and sovereign like some other<br />

regions of Aragon, Catalonia or Valencia. <strong>The</strong> baronies belonged<br />

to either the Kingdom of Aragon or the Principality of Catalonia.<br />

<strong>The</strong> inhabitants of Peralta believed that they belonged to the<br />

Kingdom of Aragon during the childhood of Calasanz. In the<br />

census for Peralta de la Sal dated August 18, 1566, one reads:<br />

"<strong>The</strong> said Peralta de la Sal and its limits are within the present<br />

Kingdom of Aragon and have a common boundary with Calasanz,<br />

Sant Esteban de Litera, del Campell, Tamarite de Litera, Corita and<br />

Gavasa." (3) In the marriage declaration of Peter Calasanz, brother<br />

of Joseph, it says: "This marriage declaration is performed<br />

according to the laws and observances of the present Kingdom of<br />

Aragon and the customs of Catalonia." (4) Michael Jimenez<br />

Barber, who was a canon from Lerida and a great friend of the<br />

Saint, said in the information process for the beatification in 1651:<br />

"I know where Peralta de la Sal is. My mother was born in a place<br />

three miles from Peralta, and I was born six miles away (Binaced).<br />

This place is in the Kingdom of Aragon." (5) <strong>The</strong> same witness<br />

remembers that, when he was studying at the University of Lerida,<br />

"all the young men from our country of Aragon elected Calasanz<br />

prior of the nation." (6)<br />

Saint Joseph Calasanz affirms that he was from Aragon in a<br />

memorandum describing the origins of the Pious <strong>Sch</strong>ools. He says:<br />

"Joseph of the Mother of God, from Peralta de la Sal, in the Diocese<br />

of Urgell, in the Kingdom of Aragon." (7) In a letter dated 1632, he<br />

says: "Although I am from Aragon, my customs and feelings are<br />

Roman, since it have lived in Rome for more than forty years. I<br />

have almost forgotten my native country." (8) <strong>The</strong> Vice-Queen of<br />

Sardinia, in a previously mentioned letter dated 1646, wrote: "I<br />

learned that you were from Aragon and, because of your name, I<br />

didn't doubt that you knew my parents," who were the barons of<br />

Castro and Peralta. (9)<br />

In spite of all this, as soon as the Saint died, someone said<br />

that he was not from Aragon but from Catalonia. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Piarist</strong>s from<br />

San Pantaleo reacted immediately against this idea. Calasanz had<br />

4

lived with them and died among them. <strong>The</strong> priests knew that the<br />

"holy old man," as he was lovingly called behind his back, had told<br />

them several times that he was from Aragon. In fact, <strong>Father</strong> John<br />

C. Caputi, one of the first historians of the Order, wrote in his<br />

memoirs that, during beatification process of Calasanz, postulatory<br />

letters were requested from the King of France. "When some<br />

Catalonian lords offered them to me, I refused them because I knew<br />

that our <strong>Father</strong> was from the Kingdom of Aragon and not from<br />

Catalonia. Those Catalonians claimed that our holy Founder was<br />

born in the Kingdom of Catalonia and was a vassal of the King of<br />

France. When he died in 1648, Catalonians and Aragonese had a<br />

disagreement because each contended to be his compatriot. <strong>The</strong>re<br />

was an Aragonese doctor who brought records from the Kingdom of<br />

Aragon. <strong>The</strong>se indicated that not only the Calasanz family but also<br />

Peralta de la Sal was under the dominion of Aragon. As our <strong>Father</strong><br />

said, he was Aragonese. In all of the confraternities in Rome,<br />

whenever he signed his name, it was always Dr. Joseph Calasanz,<br />

Aragonese." (10)<br />

However, he preferred to be considered "Roman by customs<br />

and feelings."<br />

<strong>The</strong> Calasanz-Gaston Family<br />

We must not forget that the Founder of the Pious <strong>Sch</strong>ools<br />

lived and died during the Baroque period. During this period the<br />

nobility of one's origin was held as the greatest value in society. It<br />

was not enough to be the founder of a religious order and to be<br />

greatly appreciated in many parts of Europe. Neither was it<br />

sufficient to be canonized a century after death. Worldly honors<br />

were to be added to the ecclesiastical honor. <strong>The</strong>refore, both his<br />

noble history and his virtues were exalted in the eulogies preached<br />

during the Saint’s funerals from the very beginning. Letters were<br />

written to Spain, asking about his childhood. Genealogical trees<br />

were drawn, sprinkled with mention of royal blood. For three<br />

centuries, biographies kept repeating and enlarging the nobility<br />

details and even the wealth of his parents and ancestors. It was<br />

taught that a saint from the Golden Age of Spain should stand out<br />

among the nobility of his days.<br />

5

All of this tinsel was shaken violently and fell like autumn<br />

leaves in 1921. A canon from Urgell, <strong>Father</strong> Peter Pujol i Tubau<br />

published the essay Saint Joseph Calasanz - Official of the Diocese<br />

of Urgell." He included in it a document about Calasanz receiving<br />

his tonsure. It mentions that his father, Peter Calasanz, was a<br />

blacksmith. <strong>The</strong> Saint had taken this document and others to<br />

Rome. One could see, with dismay, that the words fabri fe (fabri<br />

ferrari) were scratched out but that the two "f's" could still be made<br />

out. Whoever erased the embarrassing words wanted to hide the<br />

humble and servile state of the father of our Founder. In 1921 the<br />

debate began between the staunch defenders of the old, noble and<br />

traditional glories of the Calasanz clan and the new malingerers<br />

who denied it.<br />

Later more serene investigations have cleared up the issue.<br />

Not only his father, Peter Calasanz, but also his mother, Mary<br />

Gaston, came from families, which belonged to the nobility. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

were the lowest grade on that scale, called "infanzones" in Aragon,<br />

"hidalgos" in Castile and "donzells" in Catalonia.<br />

Some think that the word blacksmith means a "master of<br />

arms," but there are no irrefutable arguments to deny the<br />

hypothesis that he was nothing more than an ordinary blacksmith in<br />

the village.<br />

Another story regarding the noble distinction of the Saint<br />

comes from the interjection of the word "de" between his first and<br />

his last name. <strong>The</strong> Spanish custom dictates this. It has lasted up<br />

until today in many of the original documents. Some documents<br />

mention the Saint's father as "mayor" but the word "de" never<br />

appears. Here is another example, where almost all the members<br />

of the family are mentioned: "Item this contract and conditions<br />

among the said parties that Peter Calasanz, Jr. has and the said<br />

Peter Calasanz, Sr. and Mary Gaston, his parents, are giving him,<br />

reserving all the said above, give to the marrying Peter Calasanz,<br />

Jr., Jose Calasanz, Mary Calasanz, Joan Calasanz, Magdalene<br />

Calasanz and Elizabeth Calasanz, their children." (11) Neither his<br />

father nor his brothers ever used the word "de". When he first<br />

arrived in Rome, he signed all of his letters with “Joseph Calasanz,”<br />

and he mentioned his doctorate. In the marriage documents for<br />

6

Peter, his older brother, and for Hope, his sister, the names of the<br />

bride, groom, and other family members are mentioned. <strong>The</strong>re is<br />

not a single time when the word "de" appears before the surname.<br />

(11)<br />

In another large set of autographs, his first name and<br />

surname appears in the ledgers of Anthony Janer, a merchant.<br />

Calasanz lived in his house for a while. He signs in Spanish<br />

"Joseph Calasanz" thirty times and in Latin "Josephus<br />

Calasanctius" ten times. <strong>The</strong> merchant, Janer, addresses him by<br />

name about 150 times, but he places the word "de" between the<br />

first and last name only twice. We conclude, without any doubt, that<br />

the noble particle is a baroque addition of his admirers. Yet, it would<br />

be an excess of historical criticism, if we wanted to radically<br />

eliminate this particle, which has been consecrated by centuries of<br />

use. Further, we cannot ignore the fact that Calasanz could have<br />

used this particle by right, since he was a member of the nobility.<br />

<strong>The</strong> discovery, that his father was a blacksmith, forced some<br />

writers to think that the Calasanz family was rather poor and<br />

depended upon the menial work of his father.<br />

Documents suggest, however, that the family was well off.<br />

<strong>The</strong> parents endowed their five daughters, marrying them off to<br />

young men of the same social position. <strong>The</strong> parents paid for the<br />

studies of Calasanz, from the moment he left the village and moved<br />

to Estadilla and later on to the Universities of Lerida, Valencia and<br />

Alcala de Henares.<br />

In the marriage documents for Peter, his brother and the heir,<br />

it is noted that the family owns abundant goods, which came from<br />

the dowry of the mother, from the menial work of the father and<br />

from his many years as mayor of Peralta. This job paid very well.<br />

In an old register of Peralta, it says that Peter Calasanz and Mary<br />

Gaston owned several properties, houses, olive groves, a<br />

threshing-floor and hay and flax fields. Peter Calasanz was a<br />

farmer, mayor and blacksmith. All of these do not neglect the fact<br />

that he was a nobleman in Aragon.<br />

<strong>The</strong> genealogical investigations of the Saint do not agree on<br />

7

the precise lineage and on where his father and ancestors came<br />

from. <strong>The</strong>re are no documents about the birth of his parents. <strong>The</strong><br />

only certainty is that the surname Calasanz was rather popular in<br />

those lands. Calasanz was the surname of noblemen from the<br />

Middle Ages up until the Saint's time. <strong>The</strong> surname Gaston was<br />

also that of noblemen. Calasanzian genealogists have only been<br />

concerned with the paternal side of Calasanz. This supports the<br />

attitude of <strong>Father</strong> Joseph Calasanz- Gaston, who took to Rome his<br />

family seal with the coat of arms and who stamped his letters with it,<br />

showing his nobility.<br />

Peter Calasanz and Mary Gaston (Gasto), who were both<br />

from Peralta de la Sal, were the parents of Joseph Calasanz.<br />

Some claim that Peter Calasanz was born in one of the neighboring<br />

villages. <strong>The</strong> fact that he was a member of the village council and<br />

mayor of the barony of Peralta from 1559 until 1572 implies that<br />

such jobs would not be given to someone, who just arrived in town.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re were eight children from this marriage: John, Mary,<br />

Peter, Joan, Magdalene, Hope, Elizabeth and Joseph. <strong>The</strong> first<br />

born, John, died as an adult while still single. <strong>The</strong> rest all married<br />

except Joseph, of course. Peter, Mary, Hope and Elizabeth died<br />

before Joseph moved to Rome. Joseph talked about and showed<br />

his concern for the other sisters, nephews and brothers-in-law in his<br />

letters from Rome.<br />

Birth of Joseph<br />

Isn't it funny that we don't know the exact date of the birth of<br />

some saints even though some are relatively modern? For<br />

instance, we don't know the day, month and year of the birth of<br />

Ignatius Loyola, John of the Cross and Vincent de Paul.<br />

<strong>The</strong> most adequate way would be to follow the example of<br />

Saint Bonaventure who, following the example of Thomas de<br />

Celano, began the legend of Saint Francis of Assisi by saying:<br />

“<strong>The</strong>re was a man called Francis of happy memory." (12) <strong>The</strong><br />

styles of the traditional biographies of saints (hagiography) with<br />

their enchanting but sometimes incredulous and mystical stories are<br />

out of date. Today biographies and documents demand precision.<br />

8

At the time of Joseph’s death and burial, the <strong>Piarist</strong>s in Rome<br />

were not too sure about the age of their Founder. <strong>The</strong>y wrote that<br />

their Founder died at the age of 92 years, and they placed this<br />

number on a plaque made of lead on the casket. <strong>The</strong> certificate of<br />

death, which was signed by a notary public, shows that the priests<br />

had their doubts, when they included the phrase "about 92 (more or<br />

less)." This opinion was widely spread by the first historians of the<br />

Order. Some of them said that the Founder was born in either 1556<br />

or 1558, but the former (1556) prevailed in the written lives of the<br />

Saint. In the early days after his death, it was commonly believed<br />

that he was born on either December 9 or September 11. One of<br />

the most reliable historians was <strong>Father</strong> Vincent Berro. He believed<br />

that Calasanz was born on September 3 or 4 and that he was<br />

baptized on September 11. Nevertheless, tradition chose<br />

September 11, 1556 as the birth date.<br />

Before the publication of the letters of Calasanz, someone<br />

looked through them and found some in which the Saint talks about<br />

his age. Based on these letters, the person making the statements<br />

proposed 1557 as a more accurate date for the birth of the Saint.<br />

Calasanz talked about his age a dozen times saying: "I'm<br />

going to be seventy-four." "I'm a seventy-six year old man." "If I<br />

weren't eighty years old. “ On first look, these expressions point to<br />

the obvious. On the other hand, some people have used them<br />

saying, without any evidence, that the Saint did not count his age<br />

based upon completed years but instead on years to be completed.<br />

<strong>The</strong>y assert that he was following the Latin custom, annum agens.<br />

According to this interpretation, the date of his birth would be 1558.<br />

If he counted the years already completed, then it would be 1557.<br />

This latter hypothesis seems to be the more acceptable. We make<br />

this conclusion because this is the normal way of counting age,<br />

even to the present day. In addition, in letters written by him, he<br />

referred to the age of others, leaving no doubt that he counted<br />

already completed years. This is also evident, on innumerable<br />

occasions, when he requested a pontifical exception for the<br />

profession of brothers, who wished to profess before reaching the<br />

minimum canonical age of twenty-one years. In any case, based<br />

upon the statements of the Saint, it is clear that his birthday was not<br />

in 1556.<br />

9

<strong>The</strong>re is no hope of finding his baptismal certificate. <strong>The</strong><br />

procurator for the clergy in Peralta wrote in 1651: "Peralta de la<br />

Sal, where Dr. Calasanz was born and baptized, was invaded,<br />

sacked, and burned by the French twice. All of the written records<br />

from the area were lost. Among them were five books from the<br />

parish, where the date of baptism of Dr. Calasanz was written.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re is no way we can write a certificate of his baptism." (13)<br />

Home Education<br />

Typically it is said that saints showed signs of holiness early<br />

in their childhood due to the good education given to them by their<br />

parents. <strong>The</strong>re is no reason to deny it. It is also true that many<br />

things said about the Saint could be repeated about good children<br />

who have not been canonized. <strong>The</strong>re are many stories about this<br />

regarding Calasanz, both in the beatification process and among<br />

the early historians. Brother Lawrence Ferrari, who took care of the<br />

Saint during his last years, said: "He exhorted me and other young<br />

men to be pious. He told us that, when he was very young, he went<br />

to devotions and always prayed the Little Office of the Blessed<br />

Mother and other prayers, particularly the Holy Rosary." And: "I<br />

heard the same <strong>Father</strong> Joseph say that his mother and father<br />

taught him respect for God and good letters. His parents educated<br />

him, keeping him away from bad companions.<br />

<strong>Father</strong> Scassellati said: "A companion, whose name I don't<br />

remember and as old as our Superior General, told me that the<br />

childhood of <strong>Father</strong> Joseph was filled with respect for God and<br />

signs of holiness. Joseph frequently went to evening devotions and<br />

taught his companions respect for God and Christian piety." (14)<br />

We are almost sure who this companion was. It was <strong>Father</strong> Joseph<br />

Musquez (Marquet), who, while in the church of San Pantaleo in<br />

Rome for the Saint's funeral, told the <strong>Piarist</strong>s stories dating back to<br />

the childhood of his companion. <strong>Father</strong> Scassellati alluded to them<br />

when he added that the teacher in Peralta had Joseph stand on a<br />

chair and lead the class in the recitation of the Miracles of Our Lady<br />

by Berceo. This picture of Calasanz leading his class in the<br />

recitation of the Miracles of Our Lady or encouraging them to<br />

exercise piety compels one to think about the future teacher,<br />

educator and founder of an order, which was dedicated to<br />

10

education.<br />

Among the anecdotes told by <strong>Father</strong> Joseph Musquez, there<br />

is none as interesting and famous as the one told by <strong>Father</strong><br />

Benedict Quarantotto: "<strong>Father</strong> Joseph Musquez told me in the<br />

sacristy of San Pantaleo, when the Servant of God laid in state in<br />

the church on August 26, 1648, an episode that happened in<br />

Peralta de la Sal, when the Servant of God was five years old. He<br />

said to me: <strong>Father</strong>, don't be surprised that this Servant of God may<br />

already be a saint and even popularly believed to be one at the time<br />

of his death. At the age of 5 years, he once left his home and the<br />

village with a small knife drawn. When asked where he was going,<br />

he answered me: I want to kill the devil, because he is God's<br />

enemy." (15) <strong>The</strong> creative minds of the hagiographers added the<br />

final touches to the story by adding that little Joseph saw the<br />

shadow of the devil among the olive branches. <strong>Father</strong> Berro says,<br />

"After arriving at the place, he climbed a fig tree and the branch,<br />

which he climbed, broke." (16) <strong>The</strong> poor child went home hurt.<br />

This is a credible story, except for the details. It reminds us of the<br />

story of Saint Teresa of Avila and her brother, Rodrigo, who left<br />

home when they were children to go to the land of the Moors and to<br />

be decapitated out of love for Jesus.<br />

In Peralta, there was a kindergarten where little Joseph<br />

recited the miracles in front of his classmates. Joseph learned the<br />

three R's there. His father helped him with his reading and<br />

homework. We know that his father knew how to read and write,<br />

since his signature appeared in some documents. We know that<br />

his mother and his sisters were unable to read and write. Joseph<br />

couldn't study Latin in Peralta, because there was no Latin teacher<br />

until 1592. This is what Calasanz remembers: "It pleases me<br />

greatly that you hired a teacher for Latin in Peralta. This will help<br />

parents to teach letters to their children. Learning is the best<br />

inheritance that parents may leave to their children." (17)<br />

Estadilla<br />

After elementary school in Peralta, his parents had to choose<br />

a school where Joseph could study humanities and grammar<br />

(Latin), as it was called in those days. In 1541 the Trinitarian<br />

11

<strong>Father</strong>s founded a convent there, where they taught grammar.<br />

<strong>The</strong>y even had a residence for boarding students. This foundation<br />

was due to the interest of the Lords of Castro and Peralta. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

wanted a center for the humanities in their baronies to prepare<br />

children for university studies. Centers like this were also in<br />

Benabarre and Monzon.<br />

<strong>The</strong> boys from the baronies of Castro and Peralta usually<br />

went to Estadilla to receive a higher education. That is what<br />

Joseph Calasanz-Gaston did.<br />

Studies in grammar and humanities at the convent of the<br />

Trinitarians of Estadilla were divided into three levels: elementary,<br />

middle and secondary. <strong>The</strong> basic text was "that of Nebrija<br />

according to the statutes and other documents of the Kingdom of<br />

Aragon. <strong>The</strong> children studied the principles of grammar, syntax,<br />

prose and eventually rhetoric. <strong>The</strong>y studied Terence, Cicero,<br />

Caesar, Salustius, Titus, Tacitus, Virgil, Horace, Martial and even<br />

<strong>The</strong> Dialogues by L. Vives. <strong>Father</strong> Catalucci, one of the first<br />

biographers of the Founder, wrote that "after studying grammar and<br />

rhetoric in verse and prose with much success, Joseph went to the<br />

University of Lerida." (18) <strong>Father</strong> Aloysius Cavada, after visiting<br />

Peralta and its surroundings in 1690 seeking information about the<br />

Saint, left us the following statement: "I also remember that the<br />

vicar of Benabarre, who was a very good friend of Dr. Joseph<br />

(Calasanz), had a book, which was like a Roman ritual. It was a<br />

manuscript, which contained various very stylish Spanish poems,<br />

written by the said venerable <strong>Father</strong> Joseph, during his studies in<br />

Lerida, Valencia and Huesca. <strong>The</strong>y were a beautiful explanation of<br />

the mysteries of the Most Blessed Trinity and other sacred<br />

subjects." (19) Even though <strong>Father</strong> Cavada said that Calasanz was<br />

studying in the university when he wrote these poems, it seems<br />

more believable that he wrote them while in Estadilla. This is<br />

particularly true since the most common theme of the poems was<br />

the Trinity and he was studying in the convent of the Trinitarians.<br />

Furthermore, he studied rhetoric, poetry and other humanities at<br />

that time.<br />

<strong>The</strong> hagiographers did not leave us with many details about<br />

his studies in the humanities, because they were more interested in<br />

12

writing about Joseph's holiness. Joseph's friend, Dr. Michael<br />

Jimenez Barber, a canon from Lerida, wrote about Joseph's studies<br />

in Estadilla: "With respect to the education of <strong>Father</strong> Joseph during<br />

his childhood, I repeat what I heard from some older men of the<br />

area, such as Antonio Calasanz and Francis de Ager, a minister of<br />

the Holy Office and a fellow student of <strong>Father</strong> Joseph in Estadilla:<br />

“Everyone called him the santet, which means little saint. Joseph<br />

never went to school without first praying. He did so every day,<br />

even though his companions made fun of him." (20) <strong>The</strong>se stories<br />

from his fellow students in Estadilla agree with what his classmates<br />

from Peralta said. All of this resulted in a vocation to the<br />

priesthood. His father, Peter Calasanz, confirmed it. In his will<br />

dated March 8, 1571, Mr. Calasanz left everything to his son, Peter,<br />

because his heir, John, had died. In his recommendations to his<br />

son, the father told him to not only care for Joseph, by giving him<br />

everything he needed but, "believing that he will become a cleric,"<br />

to also give him a sufficient patrimony in order to receive Holy<br />

Orders, if there is no benefice." (21)<br />

According to some biographers, including <strong>Father</strong> Berro,<br />

young Joseph had a confrontation with his father, while he was still<br />

in high school and before he entered the University of Lerida. His<br />

father wanted him to enter the military service instead of pursuing<br />

an ecclesiastical vocation, which Joseph preferred. On the other<br />

hand, we are almost certain that this confrontation took place a few<br />

years later, just before the dramatic moment of Peter's death.<br />

Joseph, who was the heir and the hope for the continuation of the<br />

Calasanz family name, was in the middle of his theology studies at<br />

the time. In March 1571, Joseph was thirteen years old when his<br />

father expressly stated in his will, which was signed on that day,<br />

that he believed Joseph would become a cleric. <strong>The</strong> father could<br />

have given into the wishes of his son, but it is very improbable that,<br />

due to the times, he would give in to the will of a child over his own.<br />

<strong>The</strong> school year of 1570-1571 was probably the third and last<br />

year, which Joseph spent in Estadilla. He probably began his<br />

studies there in 1568-1569, when he was just eleven years old. He<br />

probably entered the University of Lerida at fourteen. Generally,<br />

boys studied grammar on the university level, when they were<br />

anywhere from ten to fourteen years old. <strong>The</strong>refore, before he<br />

13

egan his studies on the university level, it is only natural that he<br />

would have told his parents about his desire to become a priest. In<br />

his will of 1571, his father could have stated that Joseph wanted to<br />

be a cleric. Many years would have to pass before the blacksmith<br />

and mayor of Peralta would see his son sing his first Mass in the<br />

parish church of the village.<br />

Chapter 2<br />

UNIVERSITY STUDIES AND ORDINATION<br />

Traditional Version and Documented Data<br />

Like <strong>Father</strong> Scassellati, many early eulogists exalted the<br />

nobility of the Saint. At the same time, they said that he went to the<br />

most famous universities of Spain. <strong>The</strong> historians and<br />

contemporary biographers were more discreet. One of the<br />

historians was <strong>Father</strong> Catalucci. He prepared a document, which<br />

was used by Friar Jacinto de San Vicente, who was a Discalced<br />

Carmelite priest and who preached a eulogy a month after the<br />

death of Saint Joseph Calasanz. Fray Jacinto said: "After studying<br />

grammar and rhetoric with great success in prose and in verse, he<br />

was sent to the Universities of Lerida, Valencia and Alcala. He<br />

received Doctorates in <strong>The</strong>ology, Canon Law and civil law. (1) This<br />

was the essential story, which was repeated almost without<br />

exception by all the biographers up until the present time. In the<br />

seventeenth century, one or two biographers further exaggerated<br />

the story by giving him a Doctorate in Philosophy or by adding to<br />

the list of three universities with those of Salamanca, Perpignan or<br />

Huesca.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re have been recent researchers, who have tried to find<br />

the name of Joseph de Calasanz in the registration books of the<br />

Universities of Lerida, Valencia and Alcala. But it has been all In<br />

vain. His name does not appear in any registration records of the<br />

three universities. <strong>The</strong>re are references to studies by a student,<br />

Joseph Calasanz, in Lerida and Valencia. Given the close<br />

association of the three universities and supported by the stories of<br />

his first biographers and historians, there is no reason to deny the<br />

14

presence of the Saint in the University of Alcala de Henares. <strong>The</strong><br />

chronology and the facts facilitate this hypothesis.<br />

Data from already obtained documents, however, does not<br />

allow us to determine, with certainty, the chronology of the studies<br />

of Joseph Calasanz in either the elementary or secondary levels.<br />

Even the most recent authors disagree on a chronological<br />

outline of the studies of Joseph Calasanz. However, if the<br />

biographers tell us that he studied grammar, theology and law and<br />

that he did the latter two in a university, it is only logical that we<br />

resort to the academic statutes of the day, in order to know how<br />

many years he had to spend studying each subject. We have<br />

concluded that he spent three years studying grammar in Estadilla,<br />

because it was a prerequisite subject for any university career. In<br />

the same way, at least two or three years of Philosophy were<br />

required. He also studied law for about four years at the University<br />

of Lerida. It took four years to receive a Bachelor's Degree in<br />

<strong>The</strong>ology, followed by a period of practice ("catedriIlas") before<br />

earning a doctorate.<br />

We can prove with documents that Saint Joseph Calasanz<br />

earned a Doctorate in <strong>The</strong>ology. <strong>The</strong> acquisition of all the other<br />

academic degrees cannot be documented. He signs his name by<br />

only using the term, Doctor of <strong>The</strong>ology.<br />

It would be hard to imagine that, during the long process of<br />

securing a canonry in Rome, there was no mention of any degrees<br />

in law or in philosophy, if he had obtained them. His Bachelor’s<br />

Degree in Arts and Philosophy might be explained, but keeping<br />

quiet about his doctorate in law, if he had earned it, would be<br />

baffling.<br />

University of Lerida: First Period<br />

Joseph Calasanz, who was fourteen years old, when he<br />

finished his studies in grammar in Estadilla and left for Lerida in the<br />

autumn of 1571. It was the first time that he left the baronies of<br />

Peralta de la Sal and Castro and crossed the boundary of the<br />

Kingdom of Aragon. <strong>The</strong> ancient University of Lerida was founded<br />

15

y King James II. It was meant to serve the entire Kingdom of<br />

Aragon. Later on, other universities were founded in Huesca,<br />

Zaragoza, Valencia, Tarragona and Barcelona. It was the only<br />

university, which the Crown of Aragon maintained throughout the<br />

centuries. <strong>The</strong>re were student associations from each of the three<br />

"nations," which made up the Crown: Aragonese, Catalonians and<br />

Valencianos. By statute, the rector of the university was a student,<br />

with full juridical and academic powers, over both the professors<br />

and students. This is very hard for us to believe. In order to<br />

respect the equality of rights, the rector was elected every year,<br />

from among the law students of the three nations, who took turns.<br />

Joseph Calasanz-Gaston, who was born in Peralta de la Sal,<br />

belonged to the Aragonese "nation."<br />

Largely due to this structure, both power and authority were<br />

in the hands of the students. As one would imagine with typical<br />

university students, the University of Lerida was not exempt from<br />

protests, brawls, mayhem and riots, caused by the students. <strong>The</strong>se<br />

brawls and riots did not confine themselves to the campus, but they<br />

spilled over into the streets and squares of the city. Between 1557<br />

and 1559, Bishop Miguel Despuig tried a reform but died without<br />

accomplishing anything. He wanted to reform not only the students’<br />

life but also the curriculum. In July 1559, King Philip II approved<br />

new statutes, which had been proposed by a new reformer, Bishop<br />

Anthony Augustine Albanell of Lerida. During that time, Joseph<br />

Calasanz-Gaston had been in the classes of the university and had<br />

seen and experienced the noisy, tumultuous and turbulent<br />

atmosphere of the university.<br />

For example, on September 3, 1574, Bishop Albanell<br />

arrested John Baptist Boil, a student from Valencia and rector of the<br />

university. Since he was a cleric, he locked him up in the episcopal<br />

jail. <strong>The</strong> students rioted in the city with "standard and flag." <strong>The</strong>y<br />

were accompanied by many people, who had gathered bearing all<br />

kinds of arms. <strong>The</strong>y went to the episcopal palace, and their threats<br />

forced the bishop to let the prisoner go.<br />

We also have stories about the exceptional conduct of young<br />

Joseph Calasanz from Lerida. <strong>The</strong>y follow the same pattern of<br />

what we heard about his years in Peralta and Estadilla. Here we<br />

16

have what <strong>Father</strong> Michael Jimenez Barber, a canon from Lerida,<br />

testified: "<strong>Father</strong> Matthew Garcia, a priest and fellow student of the<br />

Servant of God, told me that, while studying at the University of<br />

Lerida when he was still young, he was very unruly and had many<br />

altercations, which placed him in many dangerous situations. He<br />

went to young Joseph, who advised and helped him to get out of<br />

those difficulties. He said that young Joseph was his Holy Spirit,<br />

since he didn't have any one else to get him out of his troubles." (2)<br />

Such stories about the piety of young Calasanz, during his<br />

childhood, adolescence and youth, might seem to us like eulogies<br />

or like events taken from a book of saints, but the guarantee of their<br />

credibility remains in the fact that we have the names of his fellow<br />

students, who remembered these anecdotes from their youth:<br />

Joseph Marquet in Peralta, Francis de Ager in Estadilla and <strong>Father</strong><br />

Mathew Garcia in Lerida. We are not dealing with generalities but<br />

with concrete deeds and cases.<br />

Looking back at his days in Lerida, it is rather interesting to<br />

see that Calasanz, at the age of eighty-two years, still remembered<br />

the dangerous times of his youth in the university. Just as he did in<br />

those days, he still continued to give advice to pugnacious and<br />

quarrelsome youth. <strong>The</strong> Saint wrote to <strong>Father</strong> Fedele in April 1639:<br />

"Your brother, Joachim, has such a hot temper that he fought again<br />

with some students coming back from school. He and his friends<br />

wounded someone in the back, and he is seriously ill. I advised him<br />

to go to Naples (where <strong>Father</strong> Fedele was stationed). If he does<br />

not leave Rome and they catch him, it will be hard to free him,<br />

because he is a natural delinquent.” In June he wrote to <strong>Father</strong><br />

Fedele again: "As for your brother, Joachim, you must encourage<br />

him to go to confession and communion every Sunday. If he does<br />

so devoutly, then the youthful rumors will quiet down. Otherwise,<br />

they will find someone who might hurt him, and he will not be able<br />

to go to confession. God allows such things to happen to those<br />

who show off, as I saw so many times in my younger days." (3)<br />

Joseph studied philosophy for three years and law for at<br />

least four years. If we suppose that, in the autumn of 1571<br />

("believing he will become a cleric," as his father said) he moved to<br />

Lerida, then he would have finished philosophy in the summer of<br />

1574. If he studied law for four years, then it was from the autumn<br />

17

of 1574 until the summer of 1578. By chance, we have two<br />

documents, one dated September 1573 and the other September<br />

1577, which Calasanz and a companion signed. Calasanz signed<br />

"Jusepe Calasanz," student, but he did not say what he was<br />

studying. This confirms the fact that he went home for vacation,<br />

since he signed the 1577 letter in Peralta and the 1573 letter in the<br />

neighboring village of Gavasa.<br />

His fellow student Matthew Garda says that <strong>Father</strong> Jimenez<br />

Barber, a canon, "told him that the students from Aragon, who were<br />

studying in Lerida, elected Calasanz as prior of his “nation,” when<br />

he was young and at the University of Lerida."(4) <strong>The</strong> Italian<br />

biographers interpreted prior as "Prince of the Students." It<br />

probably means rector of the university, since the rector of the<br />

University of Lerida was a student, who was elected by the<br />

students. Calasanz could have been elected when his nation’s turn<br />

came around. This hypothesis has not been contested. No<br />

documents have been found questioning it. Another hypothesis<br />

suggests that he was simply elected as a counselor of the rector.<br />

<strong>The</strong> rector of the university had counselors from each of the three<br />

nations. <strong>The</strong> counselors were elected by the students from each<br />

nation. It is strange that Jimenez Barber, who was a canon from<br />

Lerida and a student, knew the terminology very well. What did he<br />

mean when he said prior? Was it rector and counselor? Lately,<br />

another hypothesis has been proposed. In Lerida, there was the<br />

College of the Assumption (Dominic Pons) for students with a<br />

scholarship. In the statutes of this college, the positions of prior,<br />

rector and vice-rector are mentioned. Did Calasanz live in this<br />

college, and was he the prior or rector, since one of the students<br />

was elected to fill these positions?<br />

One of the most important events of his life at the University<br />

of Lerida occurred on April 17, 1575. Calasanz received the<br />

tonsure from the Bishop John Dimas Loris of Urgell in the Church of<br />

the Holy Christ of Almata in the city of Balaguer. In those days,<br />

some students received the tonsure in order to collect an<br />

ecclesiastic benefice, without the intention of ever becoming a<br />

priest. Joseph Calasanz received the tonsure because he wanted<br />

to become a priest, just as his father testified in 1571. Calasanz did<br />

not receive any ecclesiastic benefice until he was ordained a sub-<br />

18

deacon. He still had his expenses covered by the expressed<br />

provisions in his father’s will of 1571 and the marriage declarations<br />

of his brother, Peter, signed in 1576.<br />

Another important event for Calasanz took place in Lerida.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Jesuits preached their first mission in the city in 1575. It<br />

caused great spiritual exhilaration among the students. <strong>The</strong> Jesuits<br />

held these missions every year until 1580. Occasionally in his<br />

letters, when he was advanced in years, Calasanz said that he had<br />

respected the Jesuits since he was a young boy. In 1644 he<br />

referred to them, saying that he had known them for eighty years.<br />

(5) If our calculations are correct, then the Saint met the Jesuits for<br />

the first time in 1564, when he was seven years old, while he was<br />

still in Peralta. He also remembered them from when he was a<br />

student.<br />

Calasanz left Lerida after finishing law.<br />

Valencia and Alcala de Henares<br />

Why did Calasanz leave Lerida? <strong>The</strong>re must have been very<br />

powerful reasons to leave Lerida for Valencia, which was very far<br />

from Peralta. It isn't easy to find any satisfactory answers. <strong>The</strong>re is<br />

no question that Lerida needed reform. Its prestige in law was<br />

eminent, but such was not the case in theology. It is easy to find<br />

complaints about the sorry and deplorable state of studies in both<br />

Lerida and Valencia. Following the Council of Trent, there was a<br />

great need for reforms everywhere. Curriculum had to be brought<br />

up to date. In addition, given the internal structure of government,<br />

the students were more rebellious and unruly in Lerida than in<br />

Valencia. <strong>The</strong> Jesuits, however, were the one factor, which<br />

perhaps influenced Calasanz and caused him to change the<br />

location of his studies. <strong>The</strong> Jesuits encouraged Calasanz, who was<br />

ready to start theology, to transfer to the College of Saint Paul,<br />

which they had founded in Valencia in 1544. <strong>The</strong>y taught theology<br />

there and awarded pontifical academic degrees. Since 1567 they<br />

admitted no Jesuits as students. <strong>The</strong> patriarch, Saint John of<br />

Ribera, was convinced that teachers, who worked in schools run by<br />

religious, taught with competence. He also lamented the sad state<br />

of deterioration in the universities. That is why so many students<br />

19

left the universities to study theology in the schools run by religious.<br />

<strong>The</strong>refore, this is the reason why the name Calasanz-Gaston does<br />

not appear in the registration books of the university. Unfortunately,<br />

the expulsion of the Jesuits and other disturbances caused the<br />

archives of Saint Paul's College to disappear.<br />

Every biography includes the story of the temptation of the<br />

Saint in Valencia, when he was a robust twenty-one year old<br />

theologian.<br />

Calasanz was the only one who could describe this event, in<br />

such an intimate setting as if in a session of spiritual direction.<br />

Ascanio Simon was, for a while, a <strong>Piarist</strong> known as <strong>Father</strong> Jerome<br />

of Saint Agnes. In 1659, while preparing the beatification process<br />

of Saint Joseph Calasanz, he declared before a notary public: "I<br />

once went for a manifestation of conscience to the venerable<br />

Servant of God. After talking about many spiritual matters, he told<br />

me that, when he was a twenty-one year old theology student in<br />

Valencia, he was provoked to sin by a lady. By the grace of God<br />

and His Mother, he avoided the trap set up by the devil. He<br />

immediately left the lady, who was inciting him to sin." (6) Brother<br />

Lawrence Ferrari, in his 1652 statement for the beatification<br />

process, said the same thing. Without mentioning any names, he<br />

added: "that Calasanz had a very good and well-paying job and that<br />

he had to flee from the occasion of sin, without giving a second<br />

thought to the profit." (7) <strong>The</strong> always trustworthy <strong>Father</strong> Berro<br />

summed up what he had heard from <strong>Father</strong> Jerome by saying "that<br />

while studying in Valencia, Calasanz had an honest job as<br />

secretary to an honorable and noble lady." (8) If Calasanz was a<br />

twenty-one year old theologian, then this incident might have taken<br />

place during the 1578-1579 school year, which was the first and<br />

only year that he lived and studied theology in Valencia. We have<br />

already said that he studied his last year of law in Lerida from 1577<br />

until 1578.<br />

According to the unanimous opinion of all his biographers,<br />

Calasanz moved from Valencia to Alcala in order to avoid<br />

temptation. In his Brief News, <strong>Father</strong> Catalucci wrote that Calasanz<br />

"fled that house, looking for his confessor. <strong>The</strong>re and then, he<br />

decided to never enter the house of that lady again." (9)<br />

20

If he was studying in the College of Saint Paul and if the<br />

Jesuits had recommended it to Calasanz in Lerida as we have<br />

suggested, then one might think that his confessor was also a<br />

Jesuit, who told him to leave town and continue his studies in<br />

Alcala. <strong>The</strong> Jesuits also had a college there. Andres Capilla, the<br />

future Bishop of Urgell and a protector of Calasanz, studied in<br />

Alcala. <strong>The</strong>re were a significant number of students from Aragon in<br />

Alcala. Calasanz began his second year of theology in the autumn<br />

of 1579, according to our hypothetical chronology.<br />

Final Decision to Become a Priest<br />

To the north of the baronies of Castro and Peralta, there was<br />

the county of Ribagorza. This county was in turmoil from 1578 until<br />

1581, because the vassals took up arms against the tyranny of the<br />

Count.<br />

<strong>The</strong> rebellion expanded to the neighboring baronies, and<br />

Peralta and Castro were among them. <strong>The</strong> lords joined together,<br />

and so did the rebels. <strong>The</strong> son of the former mayor of Peralta,<br />

Peter Calasanz-Gaston, joined in the conflict to defend the rights of<br />

his lord. Unfortunately, he died at the hands of the rebels in 1579.<br />

<strong>The</strong> death of his heir jolted the old blacksmith, and he reversed his<br />

plans. Preoccupied with the future of his estate and the succession<br />

of his family name, he tried to bend the will of his son, who was<br />

already studying his second year of theology in order to become a<br />

priest. This is how a distant relative of the Saint testified in 1651:<br />

"When his brother, Peter Calasanz, who was heir of the family and<br />

the estate, died without any child, his parents wanted Joseph to<br />

become the heir of all the goods and the estate, but he did not want<br />

it. That is the truth." (10) <strong>The</strong> bad news about his brother's death<br />

reached Joseph, with the insinuation that his father wanted to make<br />

him heir. Logically, this meant that it would take a family to<br />

perpetuate the Calasanz lineage. <strong>The</strong>re were no sons left in the<br />

Calasanz-Gaston family. He was the last one. For the time being,<br />

he put it off and continued to study without returning to the village.<br />

A short time later, his mother also passed away. Joseph waited<br />

until the summer to return home, after finishing his second year of<br />

theology.<br />

21

He spent the entire 1580-1581 school year at home in<br />

Peralta de la Sal. He must have endured harassment from his<br />

father. <strong>The</strong> father asked him, by all means, to give up his priestly<br />

vocation in order to provide heirs and perpetuity to his family and<br />

estate. This battle was more demanding and painful for Joseph and<br />

more distressing than the one he had fought in Valencia with regard<br />

to the suggestions of the lady. He did not experience a new<br />

temptation. He was not tempted with the prospect of having<br />

abundant goods and a serene and happy life of fatherhood. He<br />

must have agonized about the desires of his father, who cherished<br />

the perpetuity of his family much more than the priestly vocation of<br />

his son. <strong>The</strong>se were months, when the son had to live with a<br />

father, who had lost both his wife and his heir within one year.<br />

<strong>Father</strong> Catalucci, who was the first biographer of the Saint, in<br />

his Brief News, said that Joseph had studied in the Universities of<br />

Lerida, Valencia and Alcala, and continued to tell the story of the<br />

temptation of the lady. <strong>The</strong>n he writes: "He returned home” and<br />

“Before returning home." He erased both sentences, unsure as to<br />

whether it was before or after returning to Peralta. Finally, he<br />

writes: "He fell ill and, after vowing to become a priest, he suddenly<br />

recovered his health." (11) Doubts also influenced later<br />

biographers, who did not know where exactly to place this critical<br />

illness. <strong>The</strong>re is nothing to prevent us from placing it in 1580 or<br />

1581, when he returned home after these tragic events. <strong>The</strong> illness<br />

was, without any doubt, providential. That is the way everybody<br />

interprets it. Joseph pleaded with his father that if he got well, then<br />

his father would allow him to become a priest and that he would<br />

make a vow to the Blessed Virgin in this regard. His miraculous<br />

and speedy recovery convinced his father to accept the vocational<br />

desires of his son. Joseph, once healed from his illness, awaited<br />

the new school year in order to resume his interrupted ecclesiastic<br />

studies. It was a very difficult year, but it was a decisive one for the<br />

future and even the imperishable glory of his father's name.<br />

Back to Lerida: Holy Orders<br />

Joseph Calasanz left Peralta for Lerida in the middle of<br />

October 1581. He did not think of going back to either Valencia or<br />

Alcala to finish theology. Perhaps his father's age told him to stay<br />

22

closer to home. Lerida was one day's journey from Peralta. Many<br />

of his former classmates would be there, because only three years<br />

had passed since he had left those classrooms. Only two years of<br />

theological studies remained for him to finish his theology studies.<br />

During the next two years, he received the minor and major<br />

orders. Seven years before, he had received the tonsure from his<br />

Bishop in Urgell. Now, while studying theology in Lerida, it was not<br />

required that his bishop give him the dimissorial letters to ordain<br />

him. Everything could be taken care of in the episcopal curia of<br />

Lerida. As fate would have it, there was no bishop in Lerida<br />

between 1581 and 1583. <strong>The</strong> Vicar General, <strong>Father</strong> James Mahull,<br />

had to intervene for the exams and dimissorial letters. (12) He had<br />

to be ordained outside of the city, because there was no bishop in<br />

Lerida. Calasanz and his companions had to go to Huesca to<br />

receive minor orders and the sub- deaconate. Bishop Peter de<br />

Frago did the honors in 1582 on December 17 and 18. <strong>The</strong><br />

dimissorial letters of <strong>Father</strong> Mahull and the certificate of ordination<br />

all stated that Calasanz belonged to the Diocese of Urgell.<br />

For the ordination of sub-deacon, as it is today for a deacon,<br />

one had to say the source of income for the ordinandi. If he is a<br />

religious, then it is said that he is ordained under "the title of<br />

poverty," that by the vow of poverty his sustenance is guaranteed<br />

by the order to which he belongs. If he has his own goods, then it is<br />

said he is ordained "under the title of patrimony." If he enjoys an<br />

ecclesiastical benefice, then the kind of benefice must be specified.<br />

Joseph Calasanz, at this time, did not possess any kind of<br />

patrimony, because his father had not yet made him universal heir,<br />

as he would eventually do in 1585 and 1586. For this reason, it<br />

was said that he had a benefice in the Church of Saint Stephen in<br />

Monzon in the Diocese of Lerida. Who procured it for him? What is<br />

much more interesting to remember is that precisely on November<br />

23, 1582, almost a month before Joseph Calasanz was ordained<br />

sub-deacon, <strong>Father</strong> Bartholomew Calasanz, prior of the Church of<br />

Santa Maria del Romeral, was appointed "ecclesiastic official of the<br />

villa of Monzon." (13) We cannot say they were relatives. On the<br />

other hand, the coincidence of the appointment of <strong>Father</strong><br />

Bartholomew and the awarding of an ecclesiastical benefice to the<br />

23

sub-deacon, Joseph Calasanz, in a church of Monzon makes us<br />

believe that they were relatives and that the recently appointed<br />

"official" of Monzon obtained a benefice for his young relative, a<br />

sub-deacon.<br />

A few months had passed, and the Diocese of Lerida was<br />

still vacant. Ordinations had to be carried out at the most opportune<br />

time.<br />

In January 1583, <strong>Father</strong> Caspar John de la Figuera of Jaca<br />

was recommended to become the new Bishop of Albarracin. By the<br />

end of March, Rome accepted the proposal. As soon as the new<br />

bishop learned of his appointment, he probably left for Jaca to<br />

spend a few months in Fraga, his birthplace. He waited there for<br />

his confirmation and the official communication of his appointment.<br />

Fraga belonged to the Diocese of Lerida. <strong>The</strong> Cathedral Chapter<br />

authorized Bishop-elect de la Figuera to perform all kinds of<br />

pontifical acts in Lerida, including ordinations. Joseph Calasanz<br />

travelled to Fraga in order to be ordained a deacon on April 9, 1583.<br />

(14)<br />

Finally, on December 17, 1583, Calasanz was ordained a<br />

priest by Bishop Hugo Ambrose de Moncada of Urgell. <strong>The</strong><br />

ordination took place in the chapel of his episcopal palace in<br />

Sanahuja, in the province of Lerida, in the Diocese of Urgell.<br />

Calasanz was twenty-six years old. He was not an older vocation<br />