Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

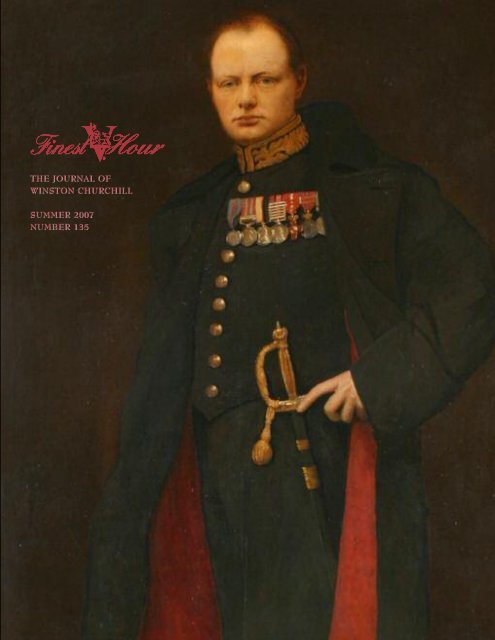

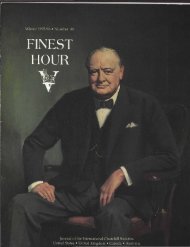

THE JOURNAL OFWINSTON CHURCHILLSUMMER 2007NUMBER 135

Number 135 • Summer 2007ISSN 0882-3715www.winstonchurchill.org____________________________Barbara F. Langworth, Publisher(blangworth@adelphia.net)Richard M. Langworth CBE, Editor(malakand@langworth.name)Post Office Box 740Moultonborough, NH 03254 USATel. (603) 253-8900December-March Tel. (242) 335-0615___________________________Deputy Editor:Robert A. CourtsSenior Editors:Paul H. CourtenayJames LancasterJames W. MullerRon Cynewulf RobbinsNews Editor:John FrostContributorsAlfred James, Australia;Terry Reardon, Canada;Inder Dan Ratnu, India;Paul Addison, <strong>Winston</strong> S. <strong>Churchill</strong>,Sir Martin Gilbert CBE,Allen Packwood, United Kingdom;David Freeman, Ted HutchinsonWarren F. Kimball,Michael McMenamin, Don Pieper,Christopher Sterling,Manfred Weidhorn, United States___________________________k Address changes: Help us keep your copiescoming! Please update your membership officewhen you move. All offices for The <strong>Churchill</strong>Centre, its Allies and Affiliates are listed on theinside front cover.__________________________________Finest Hour is made possible in part throughthe generous support of members of The<strong>Churchill</strong> Centre and Societies, the particularassistance of the Number Ten Club, and anendowment created by the <strong>Churchill</strong> CentreAssociates (listed on page 2).___________________________________Published quarterly by The <strong>Churchill</strong> Centre,which offers various levels of subscription invarious currencies. Membership applicationsmay be obtained from the appropriate officeson page 2, or may be downloaded from ourwebsite. Permission to mail at non-profit ratesin USA granted by the United States PostalService, Concord, NH, permit no. 1524.Copyright 2007. All rights reserved.Produced by Dragonwyck Publishing Inc.JUNO BEACH CENTRETo the Prime Minister, Ottawa:As one of the original members ofthe fund-raising team that solicited $8million to open the Juno Beach Centre, Isend my sincere thanks to you and yourgovernment for the recent commitmentof additional funding. As President of theInternational <strong>Churchill</strong> Society, Canada, Iattended a tour of the Normandy beacheswith Sir <strong>Winston</strong>’s daughter Lady Soames(née Mary <strong>Churchill</strong>), in October 2004. Iwas never so proud to be a Canadian aswhen this multinational group toured this“piece of Canada.” Like many, I had afather and grandfather who fought there.Everyone in our party was complimentaryon the content and focus of Canada’swartime contribution as depicted in theJuno Beach Centre. Please know thatthere are many Canadians who applaudyour initiative.RANDY BARBER, MARKHAM, ONT.EVEREST REMEMBEREDHow enjoyable was GeoffreyFletcher’s two-part article, “Spencer<strong>Churchill</strong> (p) at Harrow” (FH 133-34).Having visited the school on the wonderful<strong>Churchill</strong> tour organized by The<strong>Churchill</strong> Centre last year, I could muchmore easily envision the scenes he recreatedand appreciate the environment hedescribes. The part about Mrs. Everest isparticularly touching, and so like<strong>Churchill</strong>. The tour party visited Mrs.Everest’s grave last year, and laid a wreathon it—very appropriate.EARL M. BAKER, WAYNE, PENNA.• I’m glad you enjoyed my piece. Someyears ago ICS (UK) held our AGM at theschool and I met fellow <strong>Churchill</strong>ians fromthe United States who were in England andwere welcome guests. The conversationturned to the public (private) school systemin the UK which for many years producedmost senior politicians and civil servants.<strong>Churchill</strong> had four Old Harrovians in his1940 Cabinet: L.S. Amery, J.T.C. Moore-Brabazon, D. Margesson and G. Lloyd.This gave me the idea for the article.<strong>Churchill</strong>’s schooldays in my opinion forgedhis character, particularly between 1888and 1892, but have not been fullyresearched. I am not an Old Harrovian butI was at a similar school; times had notFINEST HOUR 135 / 4D E S PAT C H B O Xchanged very much in my time! —GJFNOT “DEAD DRUNK”An author’s note to “Like Goldfishin a Bowl” (FH 134: 33) quotes me assaying I helped a “dead drunk” <strong>Churchill</strong>and Eden home after a long dinner withthe Russians at Teheran. Let me pleasecorrect that: to me “dead drunk” meanshorizontal. Sir <strong>Winston</strong> was not so faralong as that. He was still walking,just...so much that I put my arm withinhis to hold him steady and had a corporaldo the same to Mr. Eden. Thus they wereable to walk straight and upright to theBritish Consulate. Indeed they need nothave walked, because a limousine hadbeen provided, but they decided to do sobecause it was a fine, clear night.“Inside the Journals” on the nextpage accurately describes Stalin’s customof multiple toasts, which he always performedwhile remaining firmly soberhimself. WSC and Eden were thus affectedon that occasion, but were yet able towalk home in true British fashion after aheavy night, talking loudly but notsinging, and living to fight another day!DANNY MANDER, LOS GATOS, CALIF.• Mr. Mander’s adventures, writtenthrough an interview by Susan Kidder, arecoming up in a future issue. —Ed.LORD CHARLES BERESFORDOn the back cover of FH 134, theseaman in the pool with his telescope on<strong>Churchill</strong> is more likely Admiral LordCharles Beresford, who at the time wasretired from the Navy and serving asConservative MP for Portsmouth. He wasa frequent critic in Parliament of Liberalnaval administration under <strong>Churchill</strong>. (Adrawing in Punch for 1 November 1911depicts Haldane, the outgoing First Lordof the Admiralty, saying to his successor:“And you can handle Beresford,”acknowledging his thorn-in-the-side status.)The drawing may have been influencedby the 1912 Olympic games inStockholm, which ran 5 May to 22 July.JOHN S. McCLEOD, JR., MILFORD, CONN.• See corrections on this issue’s backcover. Photos of Beresford and Bridgemansuggest that either would fit the cartoon, butwe believe you are correct, in that all theother figures are political, and Bridgemanwas not. I probably put two and two together

E D I T O R ’ S E S S AYHistory on the CheapGENERATIONAL CHAUVINISM? MAJOR CROUTONS IN THE CHURCHILL SOUPAn outbreak of pernicious pronouncements on <strong>Churchill</strong> and his times by a number of authors raises thequestion: will history join the lost arts? We are not at “the end of history,” as Francis Fukuyama famouslysuggested, before 9/11 proved him wrong. But could we be approaching the end of good history?Examples abound in this issue: a pronouncement that <strong>Churchill</strong> didn’t read serious books and borrowedhis ideas from H.G. Wells (page 10); an assertion that <strong>Churchill</strong> was a closet anti-Semite (page 40);and three new books making further fallacious pronouncements unleavened by rival facts and opinions (page 54).Tom Hickman’s <strong>Churchill</strong>’s Bodyguard (FH 133) was so packed with errors as to cast doubt on his basic<strong>Churchill</strong> knowledge. Charles Higham’s book, Dark Lady, suffers from similar errors, while adding “a soup bowl ofscandals” and a “forest of family trees.” From <strong>Churchill</strong>’s War Rooms is a book that has virtually nothing to do with<strong>Churchill</strong>; adding him to the title was done to boost sales. Gordon Corrigan’s Blood, Sweat and Arrogance, like somebooks before it, sets out with preconceived notions and considers only the facts that support them. With perfect hindsight,Corrigan assures us that sinking the French fleet at Oran in 1940 was unnecessary, and that <strong>Churchill</strong> himselflacked intellectual curiosity—so ridiculous a theory that one wonders if he read any serious biography.Such writers share a penchant for selective research and “Generational Chauvinism”: a phrase coined byWilliam Manchester to describe the judging of past events by modern standards or hindsight.Faith in the French Army of 1940 was “idiocy,” Corrigan writes, forgetting that everyoneat the time (except the Germans) thought the French unbeatable. Higham dwells on thesocial inequities of the Edwardian era as if he has just discovered them. Richard Toye dubs<strong>Churchill</strong> an anti-Semite on the basis of a draft someone else wrote, ignoring WSC’s massivepro-Semitic record. Higham doesn’t like Lord Randolph, so he assures us that QueenVictoria “detested” him, which may be true but does not define Lord Randolph. <strong>Churchill</strong>didn’t readily warm to strangers, so Corrigan concludes that he was an introvert. Withal theyare irritatingly smug, constantly asserting their superiority over predecessors who navigatedthe same waters with perhaps more judgment and balance.Cheap history is encouraged by the Internet, our electronic Hyde Park Corner: adouble-edged sword of opinion from sublime to preposterous; and by the expansion of newsoutlets to a 24/7 cacophony. In such a soup, it is much easier to become a Major Croutonby proclaiming <strong>Churchill</strong> an anti-Semite than by acknowledging his lifelong Zionism.A new book by Geoffrey Roberts claims that in 1948, Stalin told somebody in the U.S. State Department thathe hoped to “do business” with America—that if he had been born American he would have been a businessman.Could this be another isolated fact that some may seize upon to argue that Stalin was really a benign, misunderstooduncle? I have not read the book and do not presume to judge it. A scholar friend assures me that Roberts’ writing isnot the same breed of silliness as these others: “Were we wrong about Uncle Joe? Wrong (or not wrong) when? Thereis absolutely no doubt that FDR and WSC were frequently wrong about Uncle Joe. But is that a universal? That theywere wrong about the degree of his power over his advisers is, I think, not irrelevant. Or were they correct?”In those few lines a professional historian offers the alternative to cheap history. There are always practical possibilities,new avenues of thought or inquiry, which might change our view of What Really Happened. But these arenot explored with out-of-context quotations or pre-fab conclusions designed to fit a mind-set.“No one is obliged to alter the opinions which he has formed or expressed upon issues which have become apart of history,” <strong>Churchill</strong> said in 1940. “But at the Lychgate we may all pass our own conduct and our own judgmentsunder a searching review....In one phase men seem to have been right, in another they seem to have beenwrong. Then again, a few years later, when the perspective of time has lengthened, all stands in a differentsetting….History with its flickering lamp stumbles along the trail of the past, trying to reconstruct its scenes, to reviveits echoes, and kindle with pale gleams the passion of former days.”I hope history will continue to flicker on the trail of the past, and not become a discipline practiced byPolitically Correct closed minds who have already decided (or have been told) what they must believe. —RML ,FINEST HOUR 135 / 7William Manchester1922-2004

DATELINESHANDING BACK THE FIRE HOSELONDON, DECEMBER 29TH— Great Britaincompleted her last $80 million installment onWorld War II debt to the United States, paidback with interest. When your neighbor’s houseis on fire, Franklin Roosevelt said in 1940, it isappropriate to lend him your hose. Well, theUK never forgot those loans, and paid them offwith honor. —JLQuotation of the Seasonmany others, I often summon up in mymemory the impression of those July“Likedays....The old world in its sunset was fairto see. But there was a strange temper in the air.Unsatisfied by material prosperity, the nationsturned restlessly towards strife internal or external.National passions, unduly exalted in the decline ofreligion, burned beneath the surface of nearly everyland with fierce, if shrouded, fires. Almost one mightthink the world wished to suffer.”—WSC, the world crisis, VOL. 1, CH. 8, 1923SUPPORTING ACTORLOS ANGELES, FEBRUARY 25TH— WhenHelen Mirren won the AcademyAward for best actress in “TheQueen,” we remembered a telling linein the motion picture, as Her Majestyinforms Tony Blair that <strong>Winston</strong><strong>Churchill</strong> “sat right in that spot” whenshe was new to the throne. Returninghome from that excellent film, wetuned in to an older one, “AnAmerican in Paris.” There is a scenewhere Gene Kelly is walking amongthe French painters; overlooking thesea is a robust older gentleman with acigar, dabbing at a canvas. Kelly does adouble-take: it is obviously <strong>Churchill</strong>,perennial bit player in films old andnew! —EARL BAKERGLEESON TO PLAY WSCLONDON, NOVEMBER 26TH— DublinerBrendan Gleeson, best known for hisportrayal of Ireland’s most notoriouscriminal, is to play <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong>(proclaimed Britain’s chief criminal byNazi propagandists) in a sequel toRidley Scott’s “The Gathering Storm.”The star of “The General” will take onhis new role in “<strong>Churchill</strong> at War,”which will be made by HBO, theAmerican network behind “TheSopranos” and “Band of Brothers.”The story centres on <strong>Churchill</strong>’s leadershipduring the Second World War,but no British actor was deemed suitablefor the role. Gleeson, 51, willdeliver some of the Prime Minister’smost famous orations, which gaveinspiration to the nation.Gleeson has built a reputation forplaying a variety of Irish criminals and“wide-boys,” such as Bunny Kelly in “IWent Down” and Walter McGinn in“Gangs of New York.” Said TeriHayden, the actor’s agent: “The idea ofan Irishman playing <strong>Churchill</strong> is fascinating.”(Why, exactly? —Ed.)Gleeson abandoned teaching foracting at the age of 34. After a coupleof bit parts, his breakthrough role wasin “Braveheart,” playing Mel Gibson’sright-hand man, Hamish. He has sinceworked with Steven Spielberg, MartinScorsese and Anthony Minghella;starred opposite Nicole Kidman andRenée Zellweger in “Cold Mountain”;and had parts in “Mission ImpossibleII,” “Troy,” and “ArtificialIntelligence.”Gleeson is following a line ofvenerable, and more obvious,<strong>Churchill</strong>ian portraitists: Albert Finneywon an Emmy and a Golden Globefor his depiction in 2002’s “TheGathering Storm,” a look at <strong>Churchill</strong>and Clementine in the years leadingup to the Second World War. RobertHardy made the role famous in1981’s mini-series, “<strong>Winston</strong><strong>Churchill</strong>: The Wilderness Years,” asdid Richard Burton before him in1974’s “The Gathering Storm.” Themost recent portrayal of <strong>Churchill</strong> wasby Scottish actor Mel Smith in“Allegiance,” a play by Mary Kennythat imagines what passed between<strong>Churchill</strong> and Michael Collins, theIrish rebel leader, when they met inLondon. Ironically, Gleeson also portrayedCollins on screen, in a 1991television movie, “The Treaty.”“It will probably annoy a fewpeople,” said the film critic DaveFanning of Gleeson’s casting in therole. “Brendan knows how to beWINSTONIAN: Brendan Gleeson (shown here as Professor “Mad-Eye”Moody in theHarry Potter films) will make a passable WSC in “<strong>Churchill</strong> at War.”sloppy and gruff and <strong>Churchill</strong> was abit of an awkward bloke. He’d be theright build and he could certainlyslouch properly with the right coats onhim. Ridley Scott wouldn’t care thatmuch about being 100% true to howthe guy looks, as long as the feel of themovie is right. I think he’ll be great.”“<strong>Churchill</strong> at War” is being madeby the same production team asFinney’s —Scott Free Productions, andis a follow-on. Rainmark Films, aLondon-based company, is a co-produceron the film, which will be shotin England and France this summer.—JAN BATTLES, THE SUNDAY TIMESFINEST HOUR 135 / 8

HOLOCAUST OFF LIMITSLONDON, APRIL 2ND— Schools are droppingthe Holocaust from historylessons to avoid offending Muslimpupils, a Government-backed study hasrevealed. It found some teachers arereluctant to cover the atrocity for fearof upsetting students whose beliefsinclude Holocaust denial.There is also resistance to tacklingthe 11th century Crusades, whereChristians fought Muslim armies forcontrol of Jerusalem, because lessonsoften contradict what is taught in localmosques. The findings have promptedclaims that some schools are using history“as a vehicle for promotingPolitical Correctness.”—LAURA CLARK, DAILY MAIL• <strong>Churchill</strong>ian comment: “All thisis but a part of a tremendous educatingprocess. But it is an education whichpasses in at one ear and out at theother. It is an education at once universaland superficial. It produces enormousnumbers of standardized citizens,all equipped with regulation opinons,prejudices and sentiments, according totheir class or party.”—WSC, “MASS EFFECTS IN MODERNLIFE,”THOUGHTS AND ADVENTURES, 1932BIBLIOGRAPHY NIGHTLONDON, FEBRUARY 27TH— Canada House,the elegant building on the west side ofTrafalgar Square, was the scene lastnight for an enjoyable reception hostedby the High Commissioner forCanada, in celebration of RonaldCohen’s tremendous and exhaustiveBibliography of the Writings of Sir<strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong>. (See FH 133: 41.Speech will appear in FH 136.)Sir Martin Gilbert (who introducedthe author) and Randolph<strong>Churchill</strong>, Sir <strong>Winston</strong>’s great-grandson,were among the large number ofattendees, a broad group reflecting theauthor’s wide circle of contacts:archivists, historians, diplomats, bookdealers and lawyers, with the occasionalfield marshal, peer and formerCanadian prime minister thrown in.Cohen provided an entertainingand inspiring account of his long andchallenging bibliographic journey,sprinkled with amusing anecdotes ofbizarre episodes in far-flung librariesand archives. The evening was atremendous success and it was good tosee that even those who are not quiteso devoted to the Great Man were ableto appreciate the importance of Mr.Cohen’s achievement.It is clear that we can now divide<strong>Churchill</strong> bibliography into two eras:B.C. and C.E.: “Before Cohen” and“Cohen Era.” We hope that readerswho are unable to purchase their owncopy will request that their library, particularlycollege and university libraries,acquire one.—RAFAL HEYDEL-MANKOOJENNIE REMEMBEREDBATH, SOMERSET, APRIL1ST— A new exhibitionon Sir <strong>Winston</strong>’smother, LadyRandolph <strong>Churchill</strong>,opened at theAmerican Museum.A newspaper article refers to its title,“The Dollar Princess,” repeating all theold canards about how many men sheslept with, and how Lord Randolphdied of syphilis (refuted long ago in FH94). “She was the first woman of significancein British parliamentary politics,”wrote Cassandra Jardine in theDaily Telegraph. This is too broad; at atime when women were not permittedto vote, let alone to be MPs, it is difficultto describe her as a force in parliamentarypolitics.Jennie was well read and politicallysophisticated, and as <strong>Winston</strong>’s lifeopened to him she proved adept athelping him get assignments hedesired. While she did not influencepolicy, she certainly did influence atleast one election. In 1885, when LordRandolph was appointed to his firstoffice, Secretary of State for India, conventioncompelled new ministerialappointees to resign as a Member ofParliament and stand for reelection.Jennie and her sister-in-law did all hiscampaigning personally, an unusualoccurrence. It is doubtful that anywomen had done this before, let alonedone it better.Jardine claims that Jennie wroteFINEST HOUR 135 / 9Lord Randolph’s speeches and helpedevolve his theme of Tory Democracy,assertions not verified by his biographers,including their son <strong>Winston</strong>.She did write her own speeches duringthe 1885 campaign, and received lettersof congratulations from many, includingthe Prince of Wales.Jennie wrote perceptively in her1908 memoirs: “In England, theAmerican woman was looked upon as astrange and abnormal creature withhabits and manner something betweena red Indian and a Gaiety Girl....If shetalked, dressed and conducted herselfas any well-bred woman would...shewas usually saluted with the tactfulremark, ‘I should never have thoughtyou were an American,’ which wasintended as a compliment.”Lady Randolph was a greatwoman whose example of drive andenterprise, from the Boer War hospitalship to the Anglo-Saxon Review, madeher a commanding figure in her time.She was, on balance, an admirablemother. <strong>Winston</strong> and Jack alwayslooked at her with pride and affection.The American Museum at Bath is agrand institution; we hope that theirexhibit portrays Jennie for what shewas, and not as the virago of popularmyth and sensationalist biographers.continued overleaf >>ERRATA, Fh 133• Page 11, column 1, line 8: The sellingprice of the <strong>Churchill</strong> painting “Viewof Tinerhir” (prematurely stated as£350,000 against the previous auctionrecord of £344,000) was underestimated;it was sold by Sotheby’s for £612,800.• Page 32, column 1, line 29:<strong>Churchill</strong>’s Attorney-General was DonaldSomervell, the son of Robert Somervell(not the son of H.O.D. Davidson).• Page 33, column 2, line 27:Milbanke, a cavalryman, commandedthe Sherwood Rangers, a yeomanry regiment(not a battalion of the SherwoodForesters, who were infantry). Also, thepicture of the school on this page is incorrect.It is of the Lower School of JohnLyon, which was established in the 19thcentury, and the building was first occupiedin 1876.

DATELINESTORONTO STATUE UPDATETORONTO, MARCH 25TH—Finest Hour 117included a report on afund-raising drive toimprove the areaaround the statue inCity Hall Square, onthe 25th anniversaryof its unveiling, by thepresent <strong>Winston</strong><strong>Churchill</strong>, on 31October 1977. Thegoal was $25,000 and,as noted in FH 123, $28,000 wasraised from donors in six provinces.After the installation of four plaquesrecounting <strong>Churchill</strong>’s life and achievements,eight park benches and trees,the site was rededicated by MayorDavid Miller on 6 June 2004, the 60thanniversary of D-Day.Last year Toronto announced a$40 million design competition to revitalizethe Square. Competition guidelinesstated that the Henry Mooresculpture “The Archer” could not betouched, but the <strong>Churchill</strong> statue was“relocatable,” either in the square or insome other part of Toronto.The International <strong>Churchill</strong>Society of Canada promoted retainingthe <strong>Churchill</strong> statue in the Square, andthis included radio and newspapercomments. In December a Toronto Suncolumnist questioned why a statue ofnon-Torontonian should be there.Another columnist, Joe Warmington,replied that without <strong>Churchill</strong>“Toronto as we know it today mightnot even exist.” He added: “It was aman named <strong>Churchill</strong> who was thebeacon, and it was <strong>Churchill</strong> who sentthe message that we would ‘never surrender.’That should be enough; but goover to the memorial and read some ofthe passages, and tell me you don’t getgoose-bumps.”On 8 March the winning designwas picked from forty-eight entries andwe are delighted to advise that the statueis to remain in City Hall Square, inan improved location. Our next task isto ensure that the four plaques aremoved with the statue—and, we trust,the park benches.—TERRY REARDONALEX HENSHAWLONDON, FEBRUARY 24TH— Alex Henshaw,who died on 24 February at the age of94, was the principal test pilot forSpitfires and Lancasters, and a famousdaredevil. Once he was asked to put ona show for the Lord Mayor ofBirmingham’s Spitfire Fund by flyingat high speed above the city’s mainstreet. Civic dignitaries were not happywhen he flew the plane upside downbelow the level of the Council House!Often, Henshaw would be called uponto demonstrate a Spitfire to groups ofvisiting VIPs. After one virtuoso performance,<strong>Churchill</strong> was so enthralledthat he kept a special train waitingwhile he and Alex talked alone.Henshaw for his part considered<strong>Churchill</strong> “the greatest Englishmanof all time, the man who saved theworld.” —THE DAILY TELEGRAPHBORROWED FROM WELLS?LONDON, NOVEMBER 28TH— <strong>Churchill</strong> wasa closet science fiction fan who borrowedthe lines for one of his “mostfamous speeches” from H.G. Wells,said Dr. Richard Toye, who claimedthat the phrase, “The GatheringStorm” (the title of WSC’s first volumeof war memoirs) was written by Wellsyears earlier in The War of the Worlds.“It’s a bit like Tony Blair borrowingphrases from Star Trek or DoctorWho,” Dr. Toye said. “People look atpoliticians in the 20th century and presumetheir influences were big theoristsand philosophers. What we forget isthat <strong>Churchill</strong> and others were probablynot interested in reading that stuffwhen they got home after a hard day inthe House of Commons. <strong>Churchill</strong> wasdefinitely a closet science-fiction fan. Infact, one of his criticisms of Wells’ AModern Utopia (1905) was that therewas too much thought-provoking stuffand not enough action.”In 1901, Wells wrote a book ofpredictions, Anticipations, calling for ascientifically organised “new republic,”with state support for citizens. <strong>Winston</strong><strong>Churchill</strong> wrote to Wells: “I read everythingyou write,” adding that he agreedwith many of his ideas. Two days later<strong>Churchill</strong> gave an address to theFINEST HOUR 135 / 10Scottish Liberal Council in Glasgow, inwhich he said the state should supportits “left out millions.”In 1931, <strong>Churchill</strong> admitted thathe knew Wells’s work so well he couldpass an exam in it. “We need toremember that there was a time when<strong>Churchill</strong> was a radical Liberal whobelieved these things,” Toye explained.“Wells is often seen as a socialist, buthe also saw himself as a Liberal, and hesaw <strong>Churchill</strong> as someone whose viewswere moving in the right direction.”Wells advocated the idea of selectivebreeding, arguing that peopleshould only be able to have children ifthey met certain conditions such asphysical fitness and financial independence.<strong>Churchill</strong> told Wells he admired“the skill and courage with which thequestions of marriage and populationwere discussed.”Wells predicted the political unificationof “the English-speaking states”into “a great federation of whiteEnglish-speaking peoples.” <strong>Churchill</strong>often argued for the “fraternal association”of those nations, and even wrotea four-volume History of the English-Speaking Peoples.—SARAH CASSIDY, THE TIMES<strong>Churchill</strong>ian comment:In January Dr. Toye representedsomebody else’s words as <strong>Churchill</strong>’sown. Here he states that <strong>Churchill</strong>’swords were not his. WSC thus managedto commit opposite sins withequanimity. What a man!The notion that <strong>Churchill</strong> wastoo busy to do serious reading and preferredto indulge in science fictionwhen he “got home after a hard day inthe House of Commons” (hilarious toanyone steeped in WSC’s routine), issimply dumb. Anyone consulting thebooks <strong>Churchill</strong> read in his youth, forexample, know that his tastes ran fromAristotle to Shakespeare, Darwin toWynwood Reade. Certainly he read sciencefiction—even Henty novels. Andhis photographic memory stored hisfavorite phrases. That doesn’t mean hepicked up his essential philosophy fromsome novelist.At the time he wrote to Wellsabout the welfare state, <strong>Churchill</strong> >>

ICONOGRAPHY: Perhaps, heeding Dr. Richard Toye, Britain should put H.G. Wells (left)on the Twenty and Sir <strong>Winston</strong> in the Plagiarism Pen for “Gathering Storm.” But here isa prototype we like a great deal. (Photoshop® work by Barbara Langworth)was reading Progress and Poverty, by theAmerican economist Henry George,who proposed taxing private ownershipof basic elements like land instead ofwealth or income. In 1911, WSCreached his radical crescendo, fightingfor prison reform, old age pensions andabandoning the House of Lords. Thenwar clouds captured his attention. Butclearly, <strong>Churchill</strong> derived his radicalpolitics from economists and philosophers,not science fiction writers.“The Gathering Storm” dates asfar back asThe Federalist, but Toye’sclaim is specifically refuted by the officialbiography. In volume VIII, publishednearly twenty years ago, SirMartin Gilbert noted that it was literaryagent Emery Reves who suggestedthe title. <strong>Churchill</strong> merely approved ofit (pages 394-95):A final telegram from Emery Reves[January 1948] was decisive in anarea of utmost importance, the titleof the first volume. <strong>Churchill</strong> hadchosen ‘Downward Path’ as thetheme of the years 1931 to 1939.This title, Reves telegraphed,‘sounds somewhat discouraging.’The American and other publisherswould prefer a ‘more challengingtitle indicating crescendo events.’Reves suggested ‘GatheringClouds,’ ‘The Gathering Storm’ or‘The Brooding Storm.’ The title<strong>Churchill</strong> chose was ‘The GatheringStorm.’Of course one could say, “Right,it was Emery Reves who read ‘TheGathering Storm’ in The War of theWorlds and handed it to <strong>Churchill</strong>.”But that’s really being silly, isn’t it?WINSTON ON THE £20?LONDON, NOVEMBER 3RD— War veteransstormed back into battle to support acampaign by The Daily Mirror to getSir <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> put on the new£20 note. They are furious that 18thcentury economist Adam Smith hadbeen picked to replace the face of SirEdward Elgar, saying that Smith wasobscure by comparison.Ricky Clitheroe, 72, an ex-Parafrom Catford, South-East London,said: “We agree with the Mirror. Wewant Sir <strong>Winston</strong> on our £20. Hesaved this country. We don’t want aScot, we don’t even know who he is.”Wealth of Nations author Smith isdue to appear on Britain’s 1.2 billion£20 notes from this spring. War vetsset up a stall under the <strong>Churchill</strong> statuein Parliament Square to collect petitionsignatures backing WSC. They tookthe petition to the Cenotaph onRemembrance Sunday and eventuallyhanded it in to Downing Street.Yet another campaign group hadpushed for composer Elgar to remainon the notes until after his 150th birthdaynext year. MPs from Herefordshireand Worcestershire, joined by the ElgarFoundation, have called for the delay.The Bank of England replied that “agreat majority of £20 notes in circulationwill still have Sir Edward Elgar onthem and will continue to circulatealongside the Adam Smith £20 notesfor several years after that.”Meanwhile, The Fabian Societyhas called for a black face to be put on£20s to reflect Britain’s changing socialmake-up.—VANESSA ALLEN, DAILY MIRRORGILBERT AT FULTONFULTON, MO, MARCH 24TH— Sir MartinGilbert, <strong>Churchill</strong>’s official biographerand author of seventy-seven books, washosted at a dinner by the Board of the<strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> Memorial andLibrary at Westminster College. Gilbertalso held a book signing, and a collectionof <strong>Churchill</strong> photos by Richard J.Mahoney was on display. The nextafternoon Gilbert delivered the annualKemper Lecture on <strong>Churchill</strong>.Last year, in the midst of the 60thanniversary of the Fulton “Iron Curtain”speech, Chris Campbell, editor of thestudent newspaper, was quoted in theSt. Louis Post-Dispatch as questioningwhether his school name-dropped<strong>Churchill</strong> too much and whether itshould move on to a new claim tofame. The day the story ran, Campbellwas told by the school’s college relationsdirector that he could not get a presspass to the weekend’s anniversary eventsif he planned to speak to other mediaoutlets. Campbell did not want to paywhat it would have cost to go to theevents, so he acquiesced to the school’swishes. But, he complained: “I thoughtit was unfair what they did. I feel likethey were trying to stop me from speaking.”The school said it was not tryingto suppress Campbell’s views.We think Westminster Collegeshould continue name-dropping<strong>Churchill</strong>, particularly his goodEnglish, discouraging sentences like “Ithought it was unfair what they did.”MALAKAND:Y’ALL COME, HEAR?BATKHELA, PAKISTAN, DECEMBER 1ST— Thebattlefield of a far-off imperial war thatonce gripped the imagination of theBritish public is to be opened up forthe first time to tourism. It is“<strong>Churchill</strong>’s Picket,” where the young<strong>Winston</strong> fought with the 1897Malakand Field Force, the subject ofhis first book, published 1898.The Malakand battlefield area hasbeen under tight military control since<strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong>’s eyewitness accountsof the campaign were published in TheDaily Telegraph in 1897. The governmenthas now decided to grant access >>FINEST HOUR 135 / 11

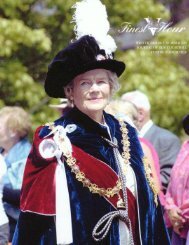

DATELINESMALAKAND...to historic sites such as Malakand Fort,where 1,000 Sikh infantry under Britishcommand fended off 10,000 Pathantribesmen led by the “Mad Mullah.” Hehad roused the tribes against Britishdominion and said the Prophet hadordained that they eject the foreignersfrom India. (Plus ça change... —Ed.)“We are seeking funding for theproject from foreign governments,”said an official from Pakistan’s tourismministry. “It is hoped that we can usesome of the finance to restore some ofthe historic buildings.” The hill-crestedbowl of Malakand is home to BritishIndia’s northernmost church, which iscurrently situated inside a Pakistanimilitary base, and a hilltop fortificationcalled <strong>Churchill</strong>’s Picket, near wherethe young <strong>Winston</strong> was almost killedin a skirmish.Malakand borders the tribalagency of Bajaur, where al-Qaeda operativesare believed to be based. As in<strong>Churchill</strong>’s day, the local Pashtuns areoften in the thrall of charismatic mullahs.Maulana Muhammad Alam, aleader of the banned Tehreek-e-Nifaz-e-Shariat Mohammadi, from Batkhela, isan ideological descendant of the “MadMullah.” His group sent 10,000 mento fight alongside the Taliban inAfghanistan in 2001. “PresidentMusharraf has gone in one direction[with America], but we have gone inanother,” he said.<strong>Churchill</strong> volunteered to fight onthe frontier amid comparable unrest.He was 23 and a lieutenant of theFourth Hussars in India when mullahsbegan to foment trouble. He joined theMalakand Field Force. “Like mostyoung fools,” he wrote in My EarlyLife, “I was looking for trouble.”Foreign visitors today are notentirely unwelcome. Tribal elders fondlyremembered British officers who left atPartition in 1947. “The Mad Mullahwas a man of exceptional qualities. Thesenew mullahs are just out for personalgain,” said Rehamatullah Khan, 90.—ISAMBARD WILKINSON, DAILY TELEGRAPH<strong>Churchill</strong>ian comment: If thissounds weird in a world where avoidingoffence to Muslims is an article ofpolitical faith, it must sound strangeryet in Pakistan. It is no surprise that achurch in these parts survives becauseit is inside a military base. Officials saythe plans to open up the area will goahead despite increasing security concernsafter a suicide attack near the sitethis month that killed forty-two armyrecruits. But a trip to the battlefield siteplanned by a British group was cancelledin November because of fears ofpossible attacks by Islamic militants.<strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong>, who visited<strong>Churchill</strong> Picket a few years before9/11, told us that it could only be seenwith a military escort. It is ironic thatPakistan seeks to create this Disneylandwith foreign support.Old DatelinesFrom the collection of John FrostTHE PM’S TWO HATSLONDON, JUNE 3RD, 1953— Many of thosewho saw the Coronation processiontwice noticed that Sir <strong>Winston</strong><strong>Churchill</strong> did not leave the Abbey inthe hat in which he drove to it. Theexplanation is that he went to theAbbey in the uniform and cocked hatof Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports.On arrival he put on over the uniformthe mantle of the Order of the Garterlent to him by the Earl Marshal. As hewas wearing this mantle when he leftthe Abbey he naturally assumed theostrich-plumed hat of the Garter also.This was lent to him by LordClarendon. —The TimesPOOR, DEAR RANDOLPHLONDON, JUNE 29TH, 1940— “In reply to arequest from the Prime Minister, theHome Secretary sent a list of 150‘prominent people’ whom he hadarrested. Of the first three on the list,two, Lady Mosley and Geoffrey Pitt-Rivers, were cousins of the <strong>Churchill</strong>s—a fact which piqued <strong>Winston</strong> andcaused much merriment among hischildren. <strong>Winston</strong> went to bed shortlyafter 1am and I resisted Randolph’sattempt to make me sit up with himand discuss the Fifth Column (whichincidentally <strong>Winston</strong> thinks a muchless serious menace than had been supposed).Randolph was in a horribleFINEST HOUR 135 / 12GRANDPAPA DRESSES UP, 3JUN53: WSCdeparted Downing Street as Lord Wardenof the Cinque Ports, emerged fromWestminster Abbey as Knight of theGarter. His grandchildren, Nicholas andEmma Soames (above) had been invitedto watch the ceremony in Whitehall. Withhim in court dress (below) are his sonRandolph and grandson <strong>Winston</strong>. The latterwas a page to his grandfather.state...and yet W said, when he askedto be allowed some more active part inthe war, that if R were killed he wouldnot be able to carry on his work.”—JOHN COLVILLE DIARY

VC “TOO POSITIVE”LONDON, APRIL 7TH— Amid the deathsand the grim struggle bravely borne byBritain’s forces in southern Iraq, onetale of heroism stands out: PrivateJohnson Beharry, whose courage in rescuingan ambushed foot patrol, andthen saving his vehicle’s crew despitehis own terrible injuries, earned him aVictoria Cross: the decoration young<strong>Churchill</strong> had most desired.For the BBC, however, his storywas “too positive.” The corporationcancelled the 90-minute drama aboutBritain’s youngest surviving VC herobecause it feared it would alienate listenersopposed to the war in Iraq. TheBBC’s retreat from the project, whichhad the working title “Victoria Cross,”will reignite the debate about the broadcaster’spatriotism. “The BBC hasbehaved in a cowardly fashion bypulling the plug on the project altogether,”said a source close to the project.“It began to have second thoughtslast year as the war in Iraq deteriorated.It felt it couldn’t show anything with adegree of positivity about the conflict.“It needed to tell stories aboutIraq which reflected the fact that somemembers of the audience didn’t approveof what was going on. Obviouslya story about Johnson Beharry couldnever do that. You couldn’t have ascene where he suddenly turned aroundand denounced the war because he justwouldn’t do that. The film is now onhold and it will only make it to thescreen if another broadcaster picks itup.” The company developing the projectis believed to have taken the scriptto ITV.The Ministry of Defence recentlyexpressed concern about Channel 4’s“The Mark of Cain,” which showedBritish troops brutalising Iraqidetainees. That programme was temporarilypulled from the schedules afterIran detained fifteen British troops. Aspokesman for the BBC admitted thatit had abandoned the VC project butrefused to elaborate.BBC’s decision to pull out willonly confirm the fears of critics thattelevision drama is only interested intelling bad news stories.—CHRIS HASTINGS, SUNDAY TELEGRAPH ,AROUND & ABOUTAntoine Capet, Professor of British Civilization,University of Rouen, told us of “Torn Asunder,” byRuaridh Nicollthe, an article on the Union ofBritain in The Observer (London) on January 7th:“<strong>Churchill</strong> famously left Scots as a rearguard at Dunkirkbecause nobody would be too upset.” This is an example of mischiefmaking.The Prime Minister would have had no knowledge of whichunits were left on the beaches during the heroic evacuation at Dunkirk.That was decided by those on the spot. As it happens, the units whichsuffered most were those ordered to defend Calais to the last: the King’sRoyal Rifle Corps and the Rifle Brigade. The word “famously” suggeststhat the reference was confused with St. Valéry—a long way southwestof Dunkirk. Here the 51st Highland Division, which had been behind theSomme and not involved in the evacuation, was obliged to surrenderafter a tough fight, having been cut off and surrounded on 12 June—eight days after the end of the Dunkirk operation. To say that the P.M.chose to sacrifice this Division is absurd. —PHCRRRRichard Littlejohn writes in the Daily Mail that Chancellor of theExchequer and presumptive new Prime Minister Gordon Brown “hasbeen comparing himself to <strong>Churchill</strong> (as well as Gandhi). I look forwardto his first prime ministerial broadcast. ‘We shall tax on the beaches, weshall tax on the landing grounds, we shall tax in the fields and in thestreets....Never in the field of human taxation, has so much been owedby so many.....I have nothing to offer but tax, tax and more tax.’”RRRAddendum to Warren Kimball’s “The Alcohol Quotient” (FH 134), fromSir Martin Gilbert, In Search of <strong>Churchill</strong> (1994, 226-27): In January1942, as Japanese forces advanced into Burma, Anthony Eden reported<strong>Churchill</strong>’s desire to fly to India to meet with Indian leaders to workout a constitution for India after the war. Sir Alexander Cadogan calledWSC’s plan “brilliantly imaginative and bold.” Eden told his private secretary,Oliver Harvey, that <strong>Churchill</strong> had “confessed that he did feel hisheart a bit...he had tried to dance a little the other night but quickly losthis breath.” Harvey commented: “What a decision to take, and how gallantof the old boy himself. But his age and especially his way of lifemust begin to tell on him. He had a beer, three ports and three brandiesfor lunch today, and has done it for years.” In the event <strong>Churchill</strong> did notgo to India, feeling he must be in London at a critical time.RRRScott Johnson in “The Limits of <strong>Churchill</strong>’s Magnanimity,” http://powerlineblog.com/May 19th, refers favorably to Finest Hour 101 regarding<strong>Churchill</strong>’s uncharacteristic remark about Stanley Baldwin in 1946 (“itwould have been much better had he never lived”). Johnson provided alink to our website, which has produced at least one new member. Healso included another <strong>Churchill</strong> quotation but it was not quite as stated,and did not apply to Baldwin: “As the man whose mother-in-law had diedin Brazil replied, when asked how the remains should be disposed of,‘Embalm, cremate and bury. Take no risks!’” This was actually from<strong>Churchill</strong>’s article, “Britain’s Deficiencies in Aircraft Manufacture,” DailyTelegraph, London, 28 April 1938, reprinted in Step by Step (London:Butterworth, 1939), 226. ,FINEST HOUR 135 / 13

DATELINES: 21 MAY 1948The Commando Memorial“NOTHING OF WHICH we have any knowledge or record has ever been done bymortal men which surpasses the splendour and daring of their feats of arms.”Nearly six decades ago in thecloisters of Westminster, theLeader of the Opposition, <strong>Winston</strong>S. <strong>Churchill</strong>, unveiled amemorial to those who haddied in the then-recent World War on servicein submarines and with commandoand airborne forces: three groups who hadknowingly faced even more dangers thanthose which confronted fighting men as amatter of course. His speech was fully reportedin the following day’s Times, butthe early biographers seem to have missedit. It bears reprinting for the light it throwsboth on the men <strong>Churchill</strong> commemoratedand on his own beliefs.Over forty years ago, when preparingthe official history of the Special OperationsExecutive in France (reissued in 2004), Iconjectured that, as he spoke, <strong>Churchill</strong>had in mind—as well as the feats hepraised—the then still inadmissible deedsof special agents for sabotage, subversionand escape who had set out on their missionsby parachute or by submarine.A distinguished audience was assembledto hear the wartime Prime Ministerthat day. Among those present were A.V.Alexander, Minister of Defence andwartime First Lord of the Admiralty; Admiralof the Fleet the Viscount Cunninghamof Hyndhope, wartime First SeaLord; Field Marshal the Earl Wavell, formerCommander-in-Chief Middle Eastand later Viceroy of India; Major GeneralSir Robert Laycock, who had been Chief ofCombined Operations; Lieutenant GeneralSir Frederick Browning, who hadbeen commander of Airborne Forces; LieutenantColonel A.C. Newman, who hadwon his Victoria Cross at St. Nazaire; andseveral other VC holders. The Dean ofWestminster, the Very Reverend A.C. Don,held a brief service. <strong>Churchill</strong> concludedwith the last two verses of an old Masonicpoem, familiar in those days to many ofthe dignitaries present.—PROFESSOR M.R.D. FOOTToday we unveil a memorialto the brave who gave theirlives for what we believe futuregenerations of theworld will pronounce arighteous and noble cause. In this ancientAbbey, so deeply wrought into therecord, the life and the message of theBritish race and nation—here whereevery inch of space is devoted to themonuments of the past and to the inspirationof the future—there will remainthis cloister now consecrated to thosewho gave their lives in what they hopedwould be a final war against the grosserforms of tyranny. These symbolic imagesof heroes, set up by their fellowcountrymenin honour and remembrance,will proclaim, as long as faithfultestimony endures, the sacrifices ofyouth resolutely made at the call of dutyand for the love of our Island home andall it stands for among men.Published by kind permission of the copyrightholder, Curtis Brown Ltd., on behalf ofthe Estate of Sir <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong>, copyright© <strong>Winston</strong> S. <strong>Churchill</strong>.BY WINSTON S. CHURCHILLPHOTOGRAPH BY TERRY MOORE BY KIND PERMISSION OF WESTMINSTER ABBEYThis memorial, with all its graceand distinction, does not claim any monopolyof prowess or devotion for thoseto whom it is dedicated. We all knowthe innumerable varieties of dauntlessservice which were performed by HisMajesty’s soldiers and servants at homeand abroad, in the prolonged ordeals ofthe Second World War for right andfreedom. Those whose memory is heresaluted would have been the first to repulseany exclusive priority in the Rollof Honour.It is in all humility which matchestheir grandeur that we here today testifyto the valour and devotion of the SubmarineService of the Royal Navy inboth wars, to the Commandos, the AirborneForces and the Special Air Service.All were volunteers. Most were highlyskilledand intensely-trained. Losseswere heavy and constant. But greatnumbers pressed forward to fill the gaps.Selection could be most strict wherethe task was forlorn. No units were soeasy to recruit as those over whichDeath ruled with daily attention. Wethink of the forty British submarines—FINEST HOUR 135 / 14

more than half our total submarinelosses—sunk amid the Mediterraneanminefields alone, of the heroic deathsof the submarine commanders andcrews who vanished for ever in theNorth Sea or in the Atlantic Approachesto our nearly-strangled island. We thinkof the Commandos, as they came to becalled—a Boer word become ever-gloriousin the annals of Britian and her Empire—andof their gleaming deedsunder every sky and clime. We think ofthe Airborne Forces and Special AirService men who hurled themselves unflinchinginto the void—when we recallall this, we may feel sure that nothing ofwhich we have any knowledge or recordhas ever been done by mortal menwhich surpasses the splendour and daringof their feats of arms.Truly we may say of them, as of theLight Brigade at Balaclava, “When shalltheir glory fade?” But there were characteristicsin the exploits of the submarines,the Commandos and the AirborneForces which, in different degrees,distinguished their work from any singleepisode, however famous and romantic.First there was the quality of precisionand the exact discharge of delicateand complex functions which requiredthe utmost coolness of mind and steadinessof hand and eye. The excitementand hot gallop of a cavalry charge didnot demand the ice-cold efficiency inmortal peril of the submarine crews and,on many occasions, of the AirborneForces and the Commandos.There was also that constant repetition,time after time, of desperate adventureswhich marked the work of theCommandos, as of the submarines, requiringnot only hearts of fire but nervesof tempered steel.To say this is not to dim the lustreof the past but to enhance, by modernlights, the deeds of their successors,whom we honour here today. Thesolemn and beautiful service in whichwe are taking part uplifts our hearts andgives balm and comfort to those livingpeople, and there are many here, whohave suffered immeasurable loss. Sorrowmay be assuaged even at the momentwhen the dearest memories are revivedand brightened. Above all, we have ourfaith that the universe is ruled by aSupreme Being and in fulfilment of asublime and moral purpose, accordingto which all our actions are judged.This faith enshrines, not only inbronze but for ever, the impulse of theseyoung men, when they gave all theyhad, in order that Britain’s honourmight still shine forth and that justiceand decency might dwell among men inthis troubled world. Of them and inpresence of their memorial we may repeatas their requiem as it was theirtheme, and as the spur for those whofollow in their footsteps the well-knownlines:...heard are the voices—Heard are the Sages,The Worlds and the Ages.“Choose well; your choice isBrief and yet endless;Here eyes do regard youIn eternity’s stillness;Here is all fullness,Ye brave, to reward you.Work, and despair not.”Poems<strong>Churchill</strong> LovedWith his usual impressive memory,<strong>Churchill</strong> was quoting the “MasonicPoem” of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe(1749-1832), which he must have readyears before or recalled from Bartlett’sFamiliar Quotations, which he essentiallymemorized. The poem is found onhttp://xrl.us/wevb, which notes: “ToEnglish-speaking Masons, Goethe’s bestknown Masonic work is the short poem‘Masonic Lodge.’ It can be found in anycollection of Goethe’s works, and inVolume Twenty of the Little MasonicLibrary. It is given in full here, not onlyfor purposes of short discussion, but because,by some unaccountable and distressingerror, the first ten lines, whichare the keynote of the whole poem[which <strong>Churchill</strong> did not quote] areomitted in the (1929) Clegg edition ofMackey’s Encyclopedia.”The Masons’s ways areA Type of ExistenceAnd his persistenceIs as the days areOf men in this world.The future hides itGladness and Sorrow,We press still thorow,Naught that abides in itDaunting us—onward.And Solemn before usVeiled, the dark portal,Goal of all mortal;Stars are silent o’er usGraves under us silent.While earnest thou gazestComes boding of terror,Comes phantasm and errorPerplexes the bravestWith doubt and misgiving.But heard are the voices—Heard are the Sages,The Worlds and the Ages;“Choose well; your choice isBrief and yet endless;Here eyes do regard youIn eternity’s stillness;Here is all fullness,Ye have to reward you,Work, and despair not.”,Fiinest Hour thanks Professor Foot for his suggestion that we republish the Commando Memorial speech. Reading it,shortly after the United States’ Memorial Day, we were struck by how much has changed in contemporary tributes to themilitary. <strong>Churchill</strong> unabashedly told us what these brave people did, hurling themselves against the enemy, “unflinchinglyinto the void.” Today when we honor those who serve, we do so almost in the abstract. Apparently, describing what they actuallydo is considered somehow too delicate, and might be found objectionable by this or that segment of society. <strong>Churchill</strong>was often quite specific about what brave individuals did for their country—but <strong>Churchill</strong> was also convinced not only ofthe justice of his cause, but of the unity of his nation. That too, sadly, has changed. —Ed. ,FINEST HOUR 135 / 15

GLIMPSESTroubled Triumvirate:The Big Three at the SummitNO ONE HAD A BETTER VIEW OF CHURCHILL, STALIN, ROOSEVELT AND TRUMAN AT THECONFERENCES THAT REMADE THE WORLD THAN THE INTERPRETERS.BY HUGH LUNGHIHugh Lunghi was born August 1920 and read Greats (Classics) at Oxford. In June 1943, then a Captain in the Royal Artillery,he was appointed aide-de-camp (ADC) and Russian language interpreter to the Head of the British Military Mission inMoscow, Lt. Gen. Sir Gifford Le Q. Martel. After the war he served as a diplomat and interpreter. He had the unusual experienceof interpreting at meetings with the first two Soviet dictators following Lenin: Stalin and Khrushchev. He is one of the few, if any,survivors of those present at most of the plenary sessions of the wartime conferences in Teheran, Yalta and Potsdam. There he wasRussian language interpreter for the British Chiefs of Staff, General Sir Alan Brooke (later Field Marshal Lord Alanbrooke),Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham and Air Chief Marshal Sir Charles Portal. He interpreted for PrimeMinisters <strong>Churchill</strong> and Attlee and Foreign Secretaries Eden and Bevin. Joining the BBC in 1954,Mr. Lunghi was editor of broadcasts to central Europe and chief commentator covering the Sovietinvasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968—the first contemporary international subject commented uponby Finest Hour. On retiring from the BBC in 1980 he was appointed Director of the Writers’ andScholars’ Educational Trust and editor of its magazine Index on Censorship. Subsequently he was electedVice Chairman of Common Cause UK. He has lectured widely on Soviet and East Europeanaffairs. His text is from his remarks at the Annual General Meeting, International <strong>Churchill</strong> Society(UK), 29 April 2006.FINEST HOUR 135 / 16

Let me preface my remarks with some thoughtsabout the Americans. They are friends. TheUnited States in its public and private giving,is the most generous nation in the whole of history,and perhaps the most idealistic in the causes ofhuman rights and freedom. Yet this generosity seems tobring about the perverse result that the U.S. isdenounced widely. I have often to remind my younglisteners that it was the U.S. which put Europe back onits feet when it was struggling to recover from thedevastation of World War II. Having served alongsideAmericans in wartime and after, I’ve found themamong the most helpful and brightest of colleaguesand friends. I feel constrained to put this on recordbecause my account of those distant wartime eventsmight seem to lean in a contrary direction. But toput a dark gloss on those historic events is far frommy intention.My first sight of any of the Big Three was, of course,of <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong>, from the Public Gallery in theHouse of Commons a couple of years or so before theoutbreak of war. Out of office, <strong>Churchill</strong> was yet againcastigating his government’s and party’s appalling recordof failure to meet the Nazi rearmament threat. In myschoolboy ignorance I thought his gadfly antics weresimply letting his own side down. After that <strong>Churchill</strong>faded from my mind until he became Prime Minister in1940. We had been at war for nine months. By theneven Oxford students began to take notice of his stirringspeeches on the wireless.Not many months after being posted from myartillery regiment to our military mission in Moscow in1943, its chief, General Martel, said I was to accompanyhim to Teheran at the end of November. There, with noprevious warning, I was ordered to interpret for theChiefs of Staff, General Sir Alan Brooke, AdmiralAndrew Cunningham and Air Marshal Sir Charles Portalat what turned out to be the first of the so-called “BigThree” conferences.Among the three heads of government, <strong>Churchill</strong>was the eldest, celebrating his 69th birthday; he hadalready met Stalin and Roosevelt, the latter seven times.Stalin was five years younger, Roosevelt the youngest at61. <strong>Churchill</strong> was the only one of the three who hadexperience of commanding troops on the battlefield—did that make him a worse strategist than the other twoor a better one? By 1943, an outsider might think thatall the allies were working more or less closely towardsthe defeat of the enemy.As we now know from innumerable accounts, thiswas far from the reality. Aside from almost non-existentmilitary cooperation, we met with antagonism andobstruction from Soviet officialdom: spiteful, evenincomprehensible behaviour. Their closely censoredmedia were generally hostile at the failure of the Anglo-Americans to open a so-called “Second Front” inWestern Europe. They scoffed at our military operationsin the Middle East, Italy, the Atlantic, and our bombingoffensive, which did constitute, however limited, a second,third, fourth and fifth front. We were grateful forthe real Russian hospitality and friendliness of Sovietcitizens brave enough to talk to foreigners. In Moscow,our food and accommodation were on the level of theprivileged class, Communist Party officials: quite comfortable,thank you.Teheran<strong>Churchill</strong> and Roosevelt flew to Teheran fromCairo, where they had disagreed bitterly over strategicpriorities. Roosevelt had declined even to talk about acommon approach to Stalin. To add to his discomfort,the Prime Minister had a throat infection, losing hisgreatest weapon: his voice. He looked worried and irritableas he arrived at the British Legation. It was the secondtime I had seen him in my life. Yet just seeing him,we suddenly felt the code-word for the conference,“Eureka,” was well-chosen.As I gathered from bits of Chiefs of Staff conversations,the President was again refusing his lunch invitationor even to talk before they both met that awkwardcustomer, Stalin. Even if he was determined to beardStalin himself, why would Roosevelt not want the observationsof <strong>Churchill</strong>, who had already met and negotiatedwith the Soviet chief? The latter, meanwhile, made hisForeign Minister, Molotov, concoct a cock-and-bull storyof an assassination plot by enemy agents in Teheran. Itsuccessfully caused a not reluctant Roosevelt to movetwo-odd miles from the U.S. Legation into a buggedhouse in the grounds of the Soviet Embassy, just a stepacross a narrow road from the British Legation. [ThatFDR and <strong>Churchill</strong> knew they were being bugged is nowaccepted: see Warren Kimball, “Listening in on Rooseveltand <strong>Churchill</strong>,” FH 131: 20. –Ed.]Today, as we know from contemporary accounts,Roosevelt sought to ingratiate himself with Stalin bymocking his British ally. He did tell <strong>Churchill</strong> he wasgoing to make a few jokes at his expense, “just to putStalin at his ease.” During the conference sessions andsocial occasions, I observed FDR assuming a jocular airabout <strong>Churchill</strong>’s cigars and “imperialist” outlook.The plenary sessions at Teheran were held in theSoviet Embassy. The first seemed somewhat disorganized.The President had not wanted an agenda; he had“not come all these miles to discuss details.” Rooseveltlooked confident and pleased to be asked, as the onlyHead of State, to chair the sessions. <strong>Churchill</strong>, lightingup his cigar, looked fit, and at first seemed not undulyembarrassed by the fairly heated arguments between theAmericans and British over strategic priorities now >>FINEST HOUR 135 / 17

TROUBLED TRIUMVIRATE...being played out in front of Stalin.As the debate developed, the PrimeMinister increasingly appeared onthe defensive, still arguing stronglyfor his vision of the militaryoptions. To me, Stalin seemed puzzledat first over the disunitybetween the Americans and British.He allowed his normallyinscrutable face a rare smile.Down the years I’ve beenasked what it was like to watch<strong>Churchill</strong>, at this momentous juncturein his life, making friends withthe ally we simply couldn’t dowithout: Josef Stalin, the biggestmass-murderer of all time, with thepossible exception of Mao Tsetung.I have vivid memories.Stalin always spoke softly,briefly, and to the point, completelyin command of facts andstatistics, hardly ever looking at anote, asking pertinent, awkwardquestions. At times we couldhardly make out his words, withtheir marked Georgian accent.Away from the table he was not thegreat heroic leader of the RedSquare icons. Short, even in hisbuilt-up, square-toed shoes, peeping under door-keeperliketrousers with a broad stripe down each side, at firstglance he looked unimpressive. His Marshal’s tunic witha plain Russian upright collar was decorated only withthe Hero of the Soviet Union gold star. At close range,he looked like a humble, kindly uncle. But I was struckby the yellow whites to his greenish brown, cat-like eyes,which hardly ever met yours if you were a stranger, aforeigner. His own staff was often brought to order witha fearsome glare. You could see them freeze, almost literallytremble in their boots.Apart from questions of military strategy and timing,Poland’s postwar frontiers, and how to secure ademocratic government, were the major battlegroundsfor <strong>Churchill</strong>. An early and firm date for the launch ofthe Second Front in Northern France was Stalin’s mainaim. Roosevelt’s was to get Russia into the war againstJapan. He was also determined to get Stalin to supporthis dream of an international peace-keeping bodypoliced by the Soviet Union, the USA, Britain andChina (at that time Chiang Kai-shek’s China, of course).At first Stalin was evidently not at all keen on a singlebody, doubtless thinking of the League of Nations, fromwhich the Soviet Union had been kicked out when itTHE WORLD OF TEHERAN: The Red Army had not yet penetrated any eastern Europeancountries, but the portents for 1944 were obvious. (Map from Newsweek, 6 DecemberFINEST HOUR 135 / 18attacked Finland in 1939. When Stalin saw the importanceRoosevelt attached to the project, the Sovietmedia, following Stalin’s line of course, ostentatiouslybegan to support it.Teheran was, I believe, the most important of theBig Three Conferences, more significant than Yalta. Apersistent historical misconception has it that EasternEurope was “betrayed” at Yalta. Not so. That happened,and I believe it did happen, in Moscow in October1943, before Teheran, at a meeting of foreign ministers:Molotov, Eden and Cordell Hull, Roosevelt’s then-Secretary of State, who seemed to know little and careless about the countries of Eastern Europe. From thelittle I saw of him I found him rather frosty. Eden’sattempt to involve the others in discussing the future ofeast and central Europe was smothered by Molotov,with the help of Hull’s cushion of indifference.Roosevelt at Teheran reinforced that impression, sayinghe intended to withdraw his troops from Europe withina year after the end of hostilities there. Stalin, I feel inretrospect, couldn’t have believed his luck. At the time,of course, we interpreters, even when briefed for a particularsession, could only guess at the strategic dreamsof the principals.

SWORD OF STALINGRAD: Stalin kissed it, Voroshilov dropped it, then apologized to WSCand invited himself to dinner. (illustrated london News and www.ushistoricalarchive.com.)Here I should explain that <strong>Churchill</strong>’s principalinterpreter was Major Arthur Birse, a peacetime banker,also from our Moscow Military Mission, born and educatedin 19th century St. Petersburg, more than twice myage, a good friend and mentor, by far the most outstanding,the most brilliant of all the Allied interpreters. ThePrime Minister didn’t like to be interrupted by his interpreteruntil he had finished his train of thought, whichsometimes went on a bit, with many a stirring phrase,making it the more difficult for us. He was demanding,but at the same time generous and encouraging.My own test came before the second plenary sessionon 29th November. The Prime Minister was topresent a Sword of Honour on behalf of King George VIto mark the heroic defence of Stalingrad. Representingthe Red Army—the only senior soldier Stalin hadbrought along, “hoping he would do,” as Stalin put it—was Marshal Voroshilov, once Stalin’s companion inarms, baby-faced, murderous and cruel. Voroshilov wasin command of several “Army Fronts” when Hitlerinvaded Russia. He proved so hopeless he had to besacked. Survivors of Stalin’s inner circle tell us that oftenhe shouted at him, “Shut up, you imbecile.”The Prime Minister proudly presented the sword.FINEST HOUR 135 / 19Stalin was visibly moved. After quietlyuttering a few words Stalinpassed the sword to Voroshilov,who promptly let it slip from thescabbard onto his toes. Stalin’s facedarkened, his fists clenched.As we dispersed after the ceremony,<strong>Churchill</strong> led our way out. Iheard, or felt, a tug at my sleeve. Itwas Voroshilov. I had been interpretingfor him that morning at theChiefs of Staff meeting. Sheepishlyhe asked my help. As we caught upwith the PM, Voroshilov, pinkfaced,stammered an apology forhis gaffe, and at the same timewished <strong>Churchill</strong> a happy birthday,which was in fact the followingday. As we walked away the PMgrowled: “A bit premature—mustbe angling for aninvitation…couldn’t even play astraight bat.”At <strong>Churchill</strong>’s 69th birthdaydinner, in the British Legation thenext evening, we witnessed anotherlittle drama unfold. Bear with me ifyou’ve already heard or read aboutit—this is how I saw it.A Persian waiter in white cottongloves and red and blue livery,making (I suspected) his first entrance, brings in themagnificent dessert, a splendid ice cream pyramid with akind of night-light under it. Stalin is making a bit of aspeech. The waiter, wanting to serve Stalin first, standsbehind him, then moves towards Molotov’s chair. Mouthagape at sight of the assembled magnificoes, the waiternervously lets the dish tip slightly. It’s hot in the roomand the inevitable happens. As I look on, fascinated, thebeautiful creation accelerates off the salver. It missesStalin, the waiter staggers further sideways, and itdescends onto the shoulder of Vladimir Pavlov, Stalin’sinterpreter, and all down his pristine Russian diplomaticdress uniform.A voice is heard just in front of me, Air ChiefMarshal Sir Charles Portal (Peter Portal to his colleagues),sotto voce: “Missed the target.”I watch the Prime Minister, but either he has notnoticed or has chosen not to. A true professional, Pavlovcontinues calmly interpreting. Pavlov, by the way, wasvirtually always Stalin’s interpreter—in English andGerman. At the Yalta Conference, some fourteenmonths after Teheran, Pavlov was rewarded by <strong>Churchill</strong>with the CBE—not, of course, for his heroism under icecream fire. >>

TROUBLED TRIUMVIRATE...MoscowAfter Teheran my next close encounter with Mr.<strong>Churchill</strong> was almost a year later in October 1944, hissecond and final visit to Moscow (codenamed “Tolstoy”),where he was accompanied by Eden. Talks with Stalinand Molotov mainly concerned Eastern Europe, the “percentage”agreement over Soviet and British influence invarious countries, and Poland. Representatives of theLondon Polish Government in exile in London were alsoinvited. The mischievous “percentages” more or less evaporatedand did not figure formally again in any tripartiteor even bilateral talks, though you’d not know it from theattention devoted to them by modern historians and<strong>Churchill</strong> himself. Our Military Mission officers, includingmyself, were on duty looking after the PrimeMinister and Foreign Secretary in the Soviet hospitalitytown house in Ostrovskiy Street (formerly and today theAustrian Embassy).YaltaThe following February, I watched <strong>Churchill</strong>’s aircraftland, after its seven-hour flight from Malta, at theCrimean airport of Saki, where I had been working formuch of the past fortnight. It touched down shortlyafter Roosevelt’s aircraft. The President, waxen cheeked,looked ghastly, his familiar black naval cloak over hisshoulders, hat-brim turned up in front, being helpedinto a jeep which <strong>Churchill</strong> solicitously followed on footas they inspected the Guard of Honour together.We had a five-hour drive to our respective destinations.Ours was the slightly odd Moorish-Scottish baronialstyle Vorontsov Palace/Villa overlooking the BlackSea at Alupka. Twelve miles away just outside Yalta wasthe last Czar’s Palace, Livadia, the American quarters andvenue of the plenary sessions. Stalin, the generous host,was in between, in the Yusupov Villa in Koreis, six milesfrom Livadia. It was there in Stalin’s headquarters thatwe held the Chiefs of Staff military meetings.The opening session of the Yalta Conference wasone of the most dramatic and fateful. It was there thatDresden’s destiny was sealed. Among many omissionsand misrepresentations put about by revisionist historiansand others in recent years is that either <strong>Churchill</strong> orAir Marshal Harris or the RAF in general were directlyand personally responsible for the deliberate annihilationof Dresden’s population and its art treasures. This is howI witnessed the matter at that first session.Among other requests and questions of militaryliaison, Stalin, with his Deputy Chief of Staff, GeneralAntonov—I watched and heard them both—asked usand the Americans to bomb lines of communication—roads and railways. They wanted to stop Hitler transferringdivisions from the west to reinforce his troops inSilesia who were blocking the Russian advance onBerlin. We ourselves had passed intelligence about thetroop movements to the Russians. They claimed theyhad it from their own sources.The road and rail network, against which contingencyplans had already been discussed by the RAFmonths previously, was the target—not the city, and notcivilians as such. One of the intended consequenceswould be the jamming of road and rail communicationsby refugees. Together with other towns, Antonov stressedthe importance of Dresden as a rail junction.The following day at the Chiefs of Staff meeting inStalin’s Yusupov Villa, which our Chief of Staff, by thenField Marshal Sir Alan Brooke, was asked to chair, thequestion of liaison for “bomb lines” was discussed.Antonov again pressed the subject of lines of communicationand entrainment, specifically via Berlin, Leipzigand Dresden. The latter he again referred to as animportant rail junction. The Soviet Air MarshalKhudyakov added his expertise to the same requests. Iinterpreted our assent. The USAAF Major-GeneralKuter also agreed. The bombing mission by the RAFand the U.S. Army Air Corps was a military success, buttragically inflicted great loss of civilian refugee life which<strong>Churchill</strong> later deeply deplored.*Here in the Crimea, Stalin looked exultant, wethought—after all, he held the trump cards. His armieswere already in occupation of most of Eastern Europe.The myth that it was carved up at Yalta is patently inaccurate.There was no need: the Red Army already heldit. After the war one of Stalin’s favourite jokes suggestedhe deserved the whole bear, and he got it!As I saw him, Roosevelt displayed indifference toEastern Europe. I thought the President—and he wasnot the only one—hopelessly misperceived the realitiesof the Soviet Union, completely misjudging Stalin, as toan extent did <strong>Churchill</strong> and Eden. It was “a pleasure towork with Stalin...there is nothing devious about him,”<strong>Churchill</strong> said. Because of his paranoia, I believe Stalin*At the Fifth <strong>Churchill</strong> Lecture, in Washington in 2005, SirMartin Gilbert stated that the first Soviet request on Dresdenarrived before Yalta, and that at Yalta, Stalin and Antonovasked <strong>Churchill</strong> why it hadn’t already been bombed. <strong>Churchill</strong>,perplexed, cabled Attlee in London, who responded that theattack had been ordered. This was actually confirmed by Gen.Antonov’s deputy, who was among the audience when Gilbertlectured on the subject in Moscow. It was undoubtedly thisconversation which Mr. Lunghi observed. Sir Martin writes:“It is curious that when the request came…<strong>Churchill</strong> and AirMarshal Portal were in flight on their way to the Yalta conference.So the request was dealt with by <strong>Churchill</strong>’s excellentdeputy Clement Attlee, later the Labour Prime Minister, andby the deputy chiefs of staff and approved. It was the 16th or17th item of the things that they had to approve that day.”FINEST HOUR 135 / 20

PARTNERS?: At Teheran, both Roosevelt (right) and <strong>Churchill</strong>thought they could trust Stalin (left). The map below, whichappeared in time as the Red Army drove across Polandtoward the Reich, forecast the post-Yalta endgame, althoughtime proved wrong about Yugoslavia and, later, Austria.did not trust those he thought were trying to curryfavour with him. Stalin at one point told <strong>Churchill</strong> hefelt more at home with frank and even tough negotiatorsand open enemies. The P.M., though wilier in thisrespect than Roosevelt, also thought he could win Stalinover by compromise and concession. By the way, unbelievably,he also said he liked the Deputy Commissar forForeign Affairs Andrey Vyshinsky—a more despicableand treacherous character I could not imagine.It was not until years after the Yalta Conferencethat one of its most tragic outcomes—one of theblackest pages in British history—was revealed. The lastformal act was Eden’s signature to the secret agreementon repatriation, in other words the return to Stalin’smerciless hands of Soviet prisoners of war. Many, forcedinto auxiliary service in the German army, had falleninto our hands. The Foreign Office agreed to Sovietdemands that even non-Soviet Russian civilians who hadlived in Eastern Europe before the war should be handedover: an unnecessary and dishonourable act which<strong>Churchill</strong> at one point tried to stop.Harry Hopkins, Roosevelt’s close adviser, whom<strong>Churchill</strong> admired, hailed Yalta as “the dawn of a newage.” Hopkins, for whom I interpreted briefly, wasunhappily a chronically ill man, and he seems to haveprovided some dodgy advice to the President aboutStalin, the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. In hisrecently published book, Sergo Beria, son of Stalin’ssecret police chief, claims Hopkins was “blindly pro-Soviet even before he met Stalin.”What stays in my memory is the doggedness, thetoughness—not without old-world courtesy and magnanimity—withwhich <strong>Churchill</strong> fought not just forBritain, but for Poland and France and for smallernations too. His private secretary Jock Colville onceremarked that the difference between WSC and deGaulle was that “de Gaulle’s loyalty was to France alone;<strong>Churchill</strong>’s was merely to Britain first.”By contrast the xenophobe Stalin and the stolidMolotov, taking the cue from Roosevelt, poured vitriolon the French: “rotten to the core and should be punished,”was one expression I heard. <strong>Churchill</strong> stuck upfor France not just out of love—Britain would need heras the main ally on the continent. But <strong>Churchill</strong> alsostood up for fair play for the German people, as distinctfrom the Nazis. Stalin taunted him: “You are pro-German,” adding to his censure the Argentinians,Brazilians and Swiss, calling them “swine,” the Swedeseven worse, the Finns “stone-obstinate.”PotsdamBy the time the leaders met again in July 1945 at“Terminal,” the last of the Big Three gatherings atPotsdam, Truman had replaced Roosevelt, who had >>FINEST HOUR 135 / 21