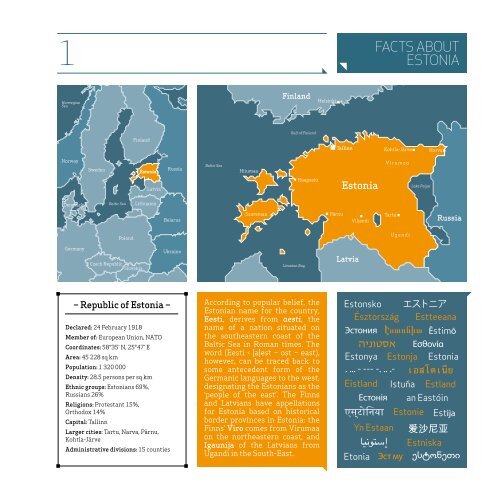

FACTS ABOUT ESTONIA

FACTS ABOUT ESTONIA

FACTS ABOUT ESTONIA

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

VISUAL<strong>ESTONIA</strong>

3VISUAL<strong>ESTONIA</strong>The changing silhouette of the capital,Tallinn, with its bustling harbour in theforeground symbolises the importancemarine trade has had for the Estonianeconomy through the ages.Throughout history the Estonians have called themselves maarahvas (lit. ‘people ofthe land’). The reason for this can be discerned in the landscape of Estonia – scatteredfarmsteads in a mosaic of fields, meadows and woodland. The taciturn nature of Estonianshas probably much to do with this reclusive way of life.Most Estonians have strong emotionalattachment to certain images, whichremind them of home, family values,the Estonian character and other suchqualities. This perception of belongingcan be evoked by the sea, the forest,a well-kept farm or simply one’s ownhome with its apple orchard, an oldtree in the front garden, a stone fenceand the surrounding rural landscape.The latter could be the fertile fields ofcentral Estonia or the meagre juniperfilledgrazing lands on the westernislands – both conjure romantic andsentimental reactions in Estonians.Other shared symbols include theTallinn skyline viewed from the seaand the facade of the classicist mainbuilding of the University of Tartu.At more than two hundred years old,the main building of the University ofTartu has witnessed the activities ofthe Baltic German Estophiles, and theemergence in the early 19th century ofthe first indigenous Estonians to seek ahigher education.

<strong>ESTONIA</strong>NFLAG

5<strong>ESTONIA</strong>NFLAGThe blue shade of the tricolourcaused some argument duringthe reinstatement of the statesymbols in the 1990s – should itrender the blue of the cornfloweror represent the cerulean of theskies? To resolve the matter anexact tone in the Pantone colourchart, No. 285C, was determinedby the National Flag Act of 1993.The Presidential flag features the greatstate coat of arms in the centre.The small coat of arms embellishes theswallow-tailed naval ensign.One of the most cherished nationalsymbols of Estonia is the blue-blackwhitecolour combination, along withits most significant expression in thenational flag.The birth of the tricolour is linkedwith the rise of national awareness inthe 1860s – the flag is therefore thesame age as the political history ofits people. The process culminatedin the blue-black-white flag beingdeclared the official state symbol bythe Estonian Provisional Governmenton 21 November 1918.The Estonian flag is hoisted everymorning at the top of Tall Hermann– the main tower of Toompea Castlein Tallinn. The banner is permanentlyflown on the premises of governmentinstitutions, municipal offices andborder checkpoints. In addition, thenational tricolour flies over schools,universities and colleges on schooldays.The flag is displayed on all residentialand public buildings on 13 Flag Daysannually, including Independence Day(24 February), Victory Day (23 June),and the Restoration of IndependenceDay (20 August). Quite naturally, allEstonians have the right and privilegeto raise the national flag on other daysas well.The flag is hoisted at sunrise, but notearlier than 7 am and taken down atsunset, but not later than 10 pm.On Midsummer Night (23/24 June) thenational flag is not lowered at all. Inother cases, any continuously hoistedflag must be illuminated during thehours of darkness.

<strong>ESTONIA</strong>NFLAG6The Estonian flag was born in thenational-romantic student circlesof the University of Tartu during thefinal quarter of the 19th century.The blue, black and white tricolourwas consecrated by the members ofthe Society of Estonian Students inOtepää on 4 June 1884.Due to the enmity of both the localBaltic German nobility and Russiancentral government, opportunities forflying the tricolour openly were quitelimited. However, the colours weresoon adopted not only by the Estonianstudents but by the whole nation.To celebrate the 120th anniversary of itsconsecration, the original Estonian flagwas again displayed in St Mary’s Churchin Otepää.The political significance of the flagwas further strengthened during thedemonstrations of the 1905 RussianRevolution and confirmed during theFebruary Revolution in 1917, whenthe Estonians managed to merge theirethnic territories in the neighbouringprovinces of Estland and Livland intoa single autonomous administrativeunit – the Estonian Governorate.The Declaration of Independence in1918 was, quite naturally, announcedunder blue, black and white banners.There are several interpretations ofthe national colours. According tothe most popular, blue represents thereflection of the sky in the lakes andthe sea, thus symbolising endurance:“until the skies last”; black stands forthe colour of the traditional greatcoatof an Estonian man or for the earththat feeds its people; white marks thedesire for light and purity.Throughout the occupations, from1940 till the end of the 1980s, theSoviet authorities sought to ban theuse of the blue, black and white colourset in any form.Yet, the colours lived on in the freeworld. In late September 1944 manyEstonians left their country in orderto escape Bolshevist persecution andlarge exile communities were foundedin Sweden, Canada, Australia andthe USA. The expatriates preservedthe flag and other national symbolsand promoted their use at everyopportunity.A symbol of resistance: an Estonian flaghidden in the wall of the headmaster’soffice at Kildu Primary School during theStalinist persecution in the 1940s, andfound in 2004.The return of the national colours inthe late 1980s was spontaneous andsteady. Starting in earnest in 1988,the civil movement that later becameknown as the Singing Revolution alsorestored the blue, black and white flagto the public domain.The flag was once again hoisted atthe top of the Tall Hermann tower ofToompea Castle on 24 February 1989.In 1991, the then almost centenarianoriginal of the Estonian national flagwas brought out from its hiding placeunderneath a stove in a farmstead nearJõgeva, where it had been concealedsince 1943. This banner is thus amongthe very few extant original nationalflags in the world.

7OTHERFLAGSThe Estonians’ use of national colourslacks neither zeal nor imagination.In Asia, one of the most noted instancesof the blue, black and white embellishedthe kesho-mawashi, the embroidered silkapron worn by Baruto – Kaido Höövelson,the first Estonian to reach the top divisionof Japanese sumo wrestling.The three colours on the flag for the majorEstonian sports association Kalev.Besides the national tricolour, therestoration of independence in 1991again introduced a large number ofcivic insignia that had been banned fornearly fifty years.Some of the snappiest examples of the useof the national colours can be found in thearmed forces. The blue, black and whitetriangular roundel was introduced as theEstonian aircraft marking in March 1919,during the War of Independence.Many towns and rural municipalitiesreinstated their old banners, manymore established entirely new ones.The Scandinavian-inspired ardour forlocal heraldic heritage, once ignited,resulted in the design of flags for allbut the tiniest of Estonian localities.Another set of blue, black and white on theflag for Paistu rural municipality.

<strong>ESTONIA</strong>NCOAT OF ARMS

ESTONANCOAT OF ARMS10The long and controversial history ofthe coat of arms, and the fact that itscharge was employed by other nations(Denmark and England) and historicallands (Normandy), were among thereasons it seemed unsuitable for theyoung Estonian Republic in the 1920s.Although the ‘three lions’ were alreadyused by the armed forces and on thecurrency, contests were organised inorder to find an alternative design.The terms prescribed to the artistssuggested showing the black eagle –põhjakotkas (lit. ‘eagle of the north’),a mythological figure in the nationalepic Kalevipoeg – or a beacon or thecharacters EV from the name for theRepublic, Eesti Vabariik. However, dueto the lack of a broad consensus, noneof the alternative designs was adoptedand the three lions remained.Young Eagles – boys’ corps of the EstonianDefence League, with the Northern Eaglecrest of the League in the background.An endeavour to combine the symbols ofthe two historical provinces of Estonia –Estland and Livland.Aware of the power of images, theSoviets tried to severe any continuityin the use of Estonian symbols anderase an entire interwar period fromthe memory of the people. Foremostamong the ‘bourgeois’ symbols proscribedwas the coat of arms with threelions, which was replaced by that of theEstonian Soviet Socialist Republic.The repudiation of history, however,brought about some embarrassmentto the Communists, as the eliminationof all precarious symbols from theiroriginal setting often left a strikinglyempty place which in turn symbolisedsomething else...The restoration of the Tallinn coat of armson the Estonian Drama Theatre. Tallinn’soldest symbol had been plastered over dueto its similarity to the coat of arms of theRepublic of Estonia.

STATEDECORATIONS12Estonia’s first state decoration, theCross of Liberty, was founded on thefirst anniversary of the declarationof independence – 24 February 1919.The Cross was bestowed for servicesrendered during the Estonian War ofIndependence (1918-20). The awardprovided several privileges includingfree university education – about 750Estonian recipients of the Cross wereeither schoolboys (and one schoolgirl)or students.The Order of the White Star is awarded toboth Estonian and foreign nationals foreminent public service for the benefit ofthe Republic of Estonia.The Cross of Liberty (2nd rank, II division)awarded to Captain Eduard Neps, CO ofarmoured train No 1, Kapten Irv. CaptainNeps was one of the nine Estonians thricedecorated with the most highly regardedstate award.Kristina Šmigun-Vähi, two-time Olympicgold medallist in cross-country skiing,presenting her Order of the Estonian RedCross, 3rd Class.The Order of the National Coat of Arms – adecoration of the highest class for servicesrendered to the republic that can only bebestowed on Estonian citizens.The Memorial Badge of the EstonianRed Cross, the first award to recogniseservices lent to the Estonian people inthe humanitarian field and for savinga life, was established in 1920 by theEstonian Red Cross Society. It was reestablishedas an order and adoptedas a state decoration in 1926.

13ANCESTRAL ANDMODERN SIGNSIn everyday life in Estonia, centuriesoldsymbolic images exist side by sidewith emblems that emerged duringthe era of the national awakening, aswell as those from the first period ofindependence. Several symbols bornduring the half-century of Communistoccupation are also still quite popular.Although absent from official usage, several cross motifs are among themost beloved and widely recognised decorative elements in Estonianfolk art. A particularly popular variant of the cross is the octagram,known in Estonian as Muhu mänd (lit. ‘Muhu whorl’) or kaheksakand(lit. ‘eight-heeled star’). Another cross motif also combining heathen andChristian connotations, the wheel or Sun cross, is equally loved.Promising new national symbols arebeing proposed by copy-writers andvisual designers, brand and marketingexperts, authors and visionaries.EST, the prefix of the numbersof Estonian sailing boats, is thesole trigram abbreviation forEstonia. The two-letter countrycodes for Estonia include ES forcivil aircraft, EE for Internettop level domain and ET for theEstonian language in the EU.The kaheksakand woven sash pattern on aformer water tower – now an art gallery inLasva, southern Estonia.Since the late 1980s, the wheel cross hasgraced the blazon of Eesti MuinsuskaitseSelts (Estonian Heritage Society).

<strong>ESTONIA</strong>NMONEY14Impressive silver necklaces worn by theorthodox Setu women commonly consistof coins minted over several centuries andweigh over two kilograms.It has been suggested that the wordraha (‘money’) in Estonian originatesfrom an ancient Gothic loan denotingfur. Another presumptive explanationconnects the original stem of rahawith the spoils of war.The oldest coin hoard found in Estoniaconsists of Late Roman sestertii andsolidi. The Viking Age introduced theArabian dirhams, Russian nogatas andWestern European denars and pence.The first local mints were probably setup in the 1220s.Early modern farthings from 16th centuryDorpat (Tartu) and Reval (Tallinn).The diversity of currencies has madeEstonian numismatics rather varied –marks, shillings, pence, öre, groschen,ducats, crowns, grivnas, kopecks andso on, have all been used on Estonianterritory.Likewise many a nascent country, thecurrency of the Republic of Estonia hasbeen used to signal the foreign policypreferences of the nation. From 1919to 1928, the name mark was used asin Germany and Finland; in the courseof the monetary reform of 1928, itwas replaced by kroon (‘crown’), thelegal tender of Sweden, Denmark andNorway.A hybrid of the Viking longship and theHanseatic cog on a one-kroon coin refersto the Estonian claim for a place amongthe ancient seafarers of the North.The newly restored Estonian statereintroduced the Estonian kroon andsent in 1992. Adopting the nationalcurrency to supersede the despisedSoviet rouble raised Estonian moraleno end. Consequently, giving up theirown money in favour of the Europeancommon currency 19 years later, in2011, was a tough sacrifice for manyEstonians.The design of pre-war Estonian banknotesrelied excessively on national imagery –hardworking country men and women andnatural landmarks.Several Estonian banknotes of the 1990sportrayed people of cultural merit, suchas author A. H. Tammsaare and romanticpoet Lydia Koidula.The Estonian outline on the national sideof Estonian Euro coins.

15NATIONALANTHEM

NATIONALANTHEM16The Manifesto to All the Peoples of Estoniaproclaiming the independence of Estoniain February 1918 ends with the last verseof Johann Voldemar Jannsen’s lyrics.Portraits of F. Pacius and J. V. Jannsen onan Estonian postal souvenir sheet issuedto celebrate the 130th anniversary of theNational Anthem.The anthem probably occupiesthe most endangered positionamongst the official nationalsymbols of Estonia. Every nowand then a discussion eruptsconcerning the need for a newnational song. The main causesof dissatisfaction are the foreignauthor, lack of national characterand the reluctance to share sucha key symbol with a neighbour.A noticeable rival to the anthememerged in the Soviet era – achoral song by Gustav Ernesaks,My Homeland is My Love, basedon a lyric poem by Lydia Koidula.Ernesaks composed the song in1944 while in forced evacuationin Russia, knowing that the oldanthem would be banned. Thissong indeed became a kind ofalternative anthem, which wassung during the years of Sovietoccupation at the end of eachsong festival, with the publicstanding and singing as one.Notwithstanding the ongoing debateabout whether or not Estonia oughtto be regarded as one of the Nordiccountries, the Estonians undeniablyhave a strong, emotional affiliationat least with one Nordic nation, thelinguistically related Finns.The affinity is further strengthenedby the fact that the two countries singtheir national anthems to the sametune composed by the German-borndenizen of Finland, Frederik Pacius.Set initially to the Swedish lyrics ofJohan Ludvig Runeberg, the nationalpoet of Finland, and published for thestudent spring festivities in 1848, thesong quickly gained popularity andwas first sung in Finnish in 1867.When Johann Voldemar Jannsen, apublicist and a founding father of theEstonian national movement, begancompiling the programme for the firstEstonian song festival, his Finnishfriends sent him this song.Jannsen provided Estonian words, andMy Native Land, My Joy, Delight wasperformed by male choirs to about15 000 spectators at the song festivalin Tartu in 1869. The piece becameincreasingly popular in Estonia andin 1920 was proclaimed the nationalanthem.In addition to the lyrics, the Estoniananthem differs from that of the Finnsby the fact that the last four phrasesare not repeated.